Category ArchiveBooks

Animation &Animation Artifacts &Books &Disney 01 Jun 2010 09:25 am

More Pink Elephants

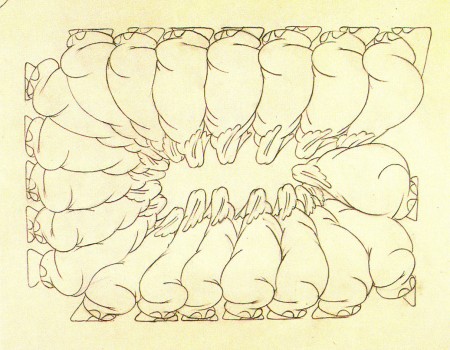

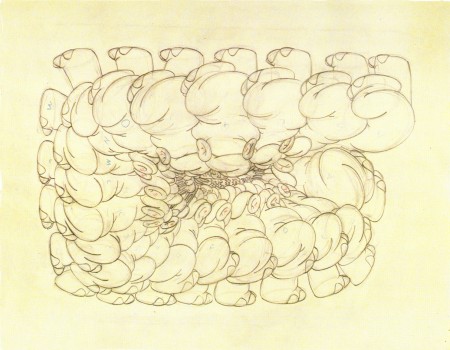

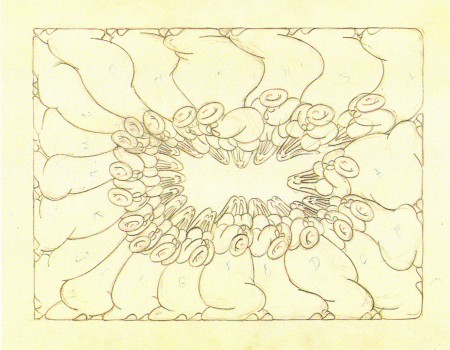

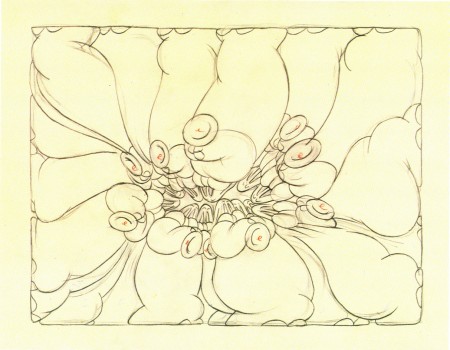

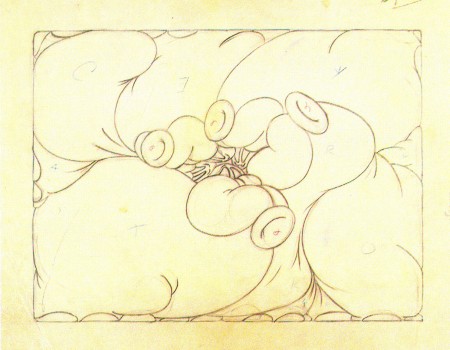

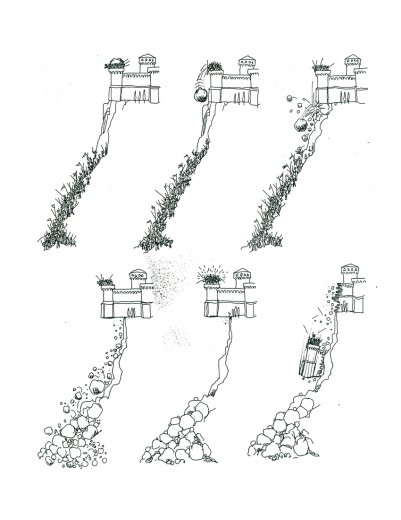

- John Canemaker‘s beautiful book, Treasures of Disney Animation Art, includes six animation cleanups of a scene by Hicks Lokey from the Pink Elephants sequence of Dumbo. Having recapped that sequence in yesterday’s post, I thought I’d show off these animation drawings.

Looking at the drawings alone you realize how much detail went into this sequence and how the animation pulses with the dominating tempo.

Take a look:

1

1

Books &Independent Animation 28 May 2010 08:10 am

More Zagreb

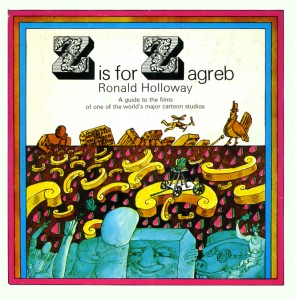

- Last week I posted a short bit from the excellent book by Ronald Holloway, Z is for Zagreb. We saw the bio of one of the principal leaders of this studio/school. I wanted to jump a couple of years and give the bios of two others in Zagreb whose work I particularly like. One, Zlatko Grgic, did one of my favorite Zagreb shorts, Tup Tup.

I precede those bios with another short piece from Holloway’s book.

Was it really a “school”? Or a group of people who liked working together? Perhaps there’s no distinction, but the Zagreb cartoonists are proud of their individuality and even today work as free agents. Most of their films bear an individual mark, and despite tempting offers from abroad they prefer the climate of a free atmosphere to exchange ideas and seek help when they need it. The Zagreb studio is not a “school” but a “family.” No other loose climate of friendship and trust exists in animation—and the Zagreb artists had to fight to keep it that way.

Was it really a “school”? Or a group of people who liked working together? Perhaps there’s no distinction, but the Zagreb cartoonists are proud of their individuality and even today work as free agents. Most of their films bear an individual mark, and despite tempting offers from abroad they prefer the climate of a free atmosphere to exchange ideas and seek help when they need it. The Zagreb studio is not a “school” but a “family.” No other loose climate of friendship and trust exists in animation—and the Zagreb artists had to fight to keep it that way.

Soon after the balmy days of the Cannes Festival and an awakening among their own critics to the importance of their work, the management of Zagreb Film changed and instead of increased support they were greeted with open envy and distrust. Suppose the animation department became strong enough to take over the entire company? As preposterous as that sounds, it makes sense in light of the fact that animation was the first international breakthrough for the Yugoslav fiirn industry. The cartoonists were celebrated in every national newspaper. And so to forestall any possible insurrection, the management brought in “artistic directors” to keep a tight rein on the real artists in the studio.

A further argument could be made for the “artistic director” by pointing out the directorial posts of non-designers Mimica and Kostelac. Mimica was to distinguish himself in the future through Marks, and Kostelac was to do the same through Kostanjsek. Who were actually responsible for these films: the director or the designer, or possibly the team together? And in the Vukotic-Kolar team it was even more difficult to decide, because they both were designers. In any case, the management overlooked the fact that each of these individuals gave as much as they took, and decided that all an “artistic director” had to do was find an idea and pull the work out of a designer. Animation was as simple as that.

It was an unfortunate phase, and one that even today appears confused and knotty. Vukotic and Mimica remained essentially unaffected and both worked in complete harmony with the units under them. Two other directors, Dragutin Vunak and Ivo Vrbanic, were not exactly new to the ranks and for the most part were successful in forming new units. The Neugebauer Brothers had left for Germany, and some new blood was needed to replace them. The designers were not confident to start out on their own, and didn’t always mind if someone else took all the risks. The trouble arose when two young graduates of the theatrical academy. Mladen Feman and Bohslav Mrksic, were brought in by the management to run their own show without any previous experience at ail. It is worthwhile to compare the careers of Vunak, Vrbanic, Feman and Mrksic.

Vunak came from Interpublic and fitted in well with Zagreb Film’s advertising department. He had previously worked with Dovnikovic and they collaborated on the picture-book A Small Train. Later he brought in an artist friend, Aleksandar Srnec. to help create the experiment film The Man and His Shadow. He gave young Ante Zaninovic his first start with Cow on ihe Frontier, appearing at a crucial time in Zagreb’s history and saving the studio from total eclipse. He fitted a superb idea to the offbeat talents of painter-sculptor Zvonimir Loncaric and made the credible Between Lips and Glass. In between he made a few bad films. The interesting factor is that each of Vunak’s successful films is in a completely different style, which leads to the conclusion that Vunak is only as good as his designer. But he nearly always picked the right designer lor the right idea, and they got along well together. Th^films could not have been completed without him.

Ivo Vrbanic is not quite in the same category. He made too many films too quickly, and most of them turned out badly. His name first appears as a co-writer of Vukotic’s satire on the horror film, The Great Fear, and he surprisingly enough has the same credit on Mimica’s Alone. He formed a brief partnership with Dovnikovic on Romeo and Juliet, and then seemed to hit the right combination with painter-designer ivo Kaiina on children’s films; A Ballad. All the Drawings of the Town, and Dance on the Hoof. He was the perfect answer for the departing Neugebauers, but he was never able to reach the heights of A Ballad and All the Drawings of the Town again. The team of Vrbanic-Grgic—Adam and Eve, Love and Film, The White Mouse, and The Rivals—shows a general discomfort with satire, although there are many nice touches throughout. The biggest mistake of Vrbanic’s career was coming into contact with the volcanic Vlado Kristl. They are billed as co-directors of La Peau de Crfagrin. but Vrbanic has very little to do with the cartoon as a whole and they were in constant disagreement from beginning to end. Vrbamfi as an artist always seems to be out of his depth in the adult cartoon but he probably would have been successful in the old Duga days.

Mladen Feman was also assigned to satire—and was the first to run headlong into the temper of Kristl. Kristl, one of the country’s leading abstract artists, had just returned from a trip through Europe and South America, and was not about to be suppressed by young graduates from the theatrical academy. They battled throughout The Great Jewel Robbery, a follow-up parody on Vukotic’s successful Concerto for Sub-Machine Gun that turned out to be better artistically and commercially than the first one. He next tried to supervise the formidable Marks in a follow-up to Vukotic’s Cowboy Jimmie, and again it was clear who was really in control of the film. He made one last attempt to prove his own worth on the doomed Inspector Mask series by directing, designing and animating independently, then left the feature cartoon for good. It can be argued in his favour that Feman never really had a chance to prove his worth under the prevailing system.

The worst case of artistic suicide was the strange career of Borislav Mrksic. He was matched with veteran designer Ismet Voljevica on the ill-fated The Kite, which is in the running for the ugliest film ever made and should be shown at the Annual Congress of Artistic Directors. After this disaster Mrksic disappeared from the studio, and Feman and Vrbanic were eventually to follow him.

Toward the end of the Fifties articles began to appear in the newspaper condemning the policy of suppressing the studio’s leading talent. Fadil Hadzic led the crusade, and he even went so far as to include Vukotic and Mimica among the guilty parties. All the credit for animation should go to the designer, he contended—an equally fallacious argument- But after a while the management went through another change and the integrity of the artists was restored. An axiom was adopted at the studio: an animated film is an author’s film. The ideal situation was for an author to be responsible for everything, from first conception through design and animation. Direction and animation need not necessarily be separated. It is an axiom that has lasted until today.

Only it’s too bad it had to cost the talents of the studio’s best artist.

Zlatko Grgic

(Born 1931 in Zagreb).

Studied journalism and law before turning to cartoons in 1951. He contributed some cartoons to Kerempuh and assisted as animator on Kostelac’s Opening Night (1957) and Encounter in a Dream (1957). He was the chief animator on Norbert Neugebauer’s The False Canary (1958), and Vukotic’s The Great Fear (1958) and Revenger (1958). He was Vukotic’s designer and animator for Cow on the Moon (1959), and later directed under Vukotic’s supervision A Visit from Space (1964) and The Devil’s Work (1965). He formed a team with Vrbanic in 1 960 and designed and animated for him Adam and Eve (1960). Love and Film (1961), and The White Mouse (1961), and animated his Rivals (1962). He was the animator on Vrbanic-Kristl’s La Peau de Chagrin (1960). He began as an independent director on an advertising film in 1960. designed and animated Branko Ranitovic’s children’s film Nisu Znaii jer su Mali (1960) for Zora Film, and directed in the Case (1961) and Inspector Mask (1962) series. Forming a team with Stalter they co-directed The Fifth (1964) and Scabies (1969). Staiter was Grgic’s background painter on The Musical Pig (1965) and Grgic was Stalter’s animator on Boxes (1967). Grgic also helped Dovnikovic on his script for Krek (1967), after Dovnikovic assisted him on the script for The Musical Pig.

Studied journalism and law before turning to cartoons in 1951. He contributed some cartoons to Kerempuh and assisted as animator on Kostelac’s Opening Night (1957) and Encounter in a Dream (1957). He was the chief animator on Norbert Neugebauer’s The False Canary (1958), and Vukotic’s The Great Fear (1958) and Revenger (1958). He was Vukotic’s designer and animator for Cow on the Moon (1959), and later directed under Vukotic’s supervision A Visit from Space (1964) and The Devil’s Work (1965). He formed a team with Vrbanic in 1 960 and designed and animated for him Adam and Eve (1960). Love and Film (1961), and The White Mouse (1961), and animated his Rivals (1962). He was the animator on Vrbanic-Kristl’s La Peau de Chagrin (1960). He began as an independent director on an advertising film in 1960. designed and animated Branko Ranitovic’s children’s film Nisu Znaii jer su Mali (1960) for Zora Film, and directed in the Case (1961) and Inspector Mask (1962) series. Forming a team with Stalter they co-directed The Fifth (1964) and Scabies (1969). Staiter was Grgic’s background painter on The Musical Pig (1965) and Grgic was Stalter’s animator on Boxes (1967). Grgic also helped Dovnikovic on his script for Krek (1967), after Dovnikovic assisted him on the script for The Musical Pig.

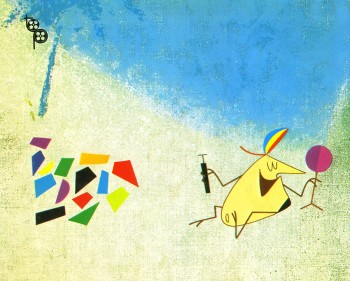

After The Musical Pig Grgic has directed independently Little and Big (1966), Inventor of Shoes (1967). and Twiddle-Twaddle (1968), and co-directed with Branko Ranitovic Tolerance (1967) and The Suitcase (1969) (for Viba Film). Inventor of Shoes prompted the Professor Balthasar series (1969), the studio’s first successful adventure into a series and the combined work of Grgic. Kolar and Zaninovic. His mini mini creation is Maxi Cat. A master of free, dynamic animation with numerous twists, witty gags and unexpected turns. Grgic is one of the subtlest poets in the animation business.

After The Musical Pig Grgic has directed independently Little and Big (1966), Inventor of Shoes (1967). and Twiddle-Twaddle (1968), and co-directed with Branko Ranitovic Tolerance (1967) and The Suitcase (1969) (for Viba Film). Inventor of Shoes prompted the Professor Balthasar series (1969), the studio’s first successful adventure into a series and the combined work of Grgic. Kolar and Zaninovic. His mini mini creation is Maxi Cat. A master of free, dynamic animation with numerous twists, witty gags and unexpected turns. Grgic is one of the subtlest poets in the animation business.

Nedeljko Dragic

(Born 1936 in Paklenica).

Studied law in Zagreb and worked from 1953 for a number of newspapers and journals as cartoonist. He published in 1964 a book of his cartoons, Alphabet for Illiterates, and has won awards for his “anti-” comic strips. His first contribution to the Zagreb studio was as designer for Ranitovic’s The Dreamer (1961), Kostelac’s Cupid (1961), and Vrbanic’s Rivals (1962). He designed and animated in the Inspector Mask series (1962), and returned to the studio again in 1 964 to design Pejakovic’s Once upon a Time There Was a Dot. His first independent cartoon was Elegy (1965), taken out of a page of his cartoon book, and from a Mimica script he created

Studied law in Zagreb and worked from 1953 for a number of newspapers and journals as cartoonist. He published in 1964 a book of his cartoons, Alphabet for Illiterates, and has won awards for his “anti-” comic strips. His first contribution to the Zagreb studio was as designer for Ranitovic’s The Dreamer (1961), Kostelac’s Cupid (1961), and Vrbanic’s Rivals (1962). He designed and animated in the Inspector Mask series (1962), and returned to the studio again in 1 964 to design Pejakovic’s Once upon a Time There Was a Dot. His first independent cartoon was Elegy (1965), taken out of a page of his cartoon book, and from a Mimica script he created

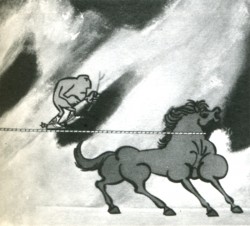

the impressive Tamer of Wild Horses (1966). But the pure Dragic is to be found in Diogenes Perhaps (1967) and Passing Days (1969), winners of numerous international awards. He scripted Blazekovic’s The Man Who Had to Sing (1970) and did the backgrounds for Dovnikovic’s The Flower Lovers (1970). He did the first mini mini films. Per Aspera ad Astra and Striptease (both in 1969), to introduce the studio’s annual production and started the creative one-minute fad. Dragi6′s satirical slams are unmatched in animation, stemming from his rich newspaper experience. He balances his sharp criticism of the world’s inhumanity with poetic touches of melancholy and nostalgia for a saner life.

the impressive Tamer of Wild Horses (1966). But the pure Dragic is to be found in Diogenes Perhaps (1967) and Passing Days (1969), winners of numerous international awards. He scripted Blazekovic’s The Man Who Had to Sing (1970) and did the backgrounds for Dovnikovic’s The Flower Lovers (1970). He did the first mini mini films. Per Aspera ad Astra and Striptease (both in 1969), to introduce the studio’s annual production and started the creative one-minute fad. Dragi6′s satirical slams are unmatched in animation, stemming from his rich newspaper experience. He balances his sharp criticism of the world’s inhumanity with poetic touches of melancholy and nostalgia for a saner life.

The unfortunate part of the book is that it was written in 1972 and doesn’t detail, as a result, the most important part of both of these artists’ careers.

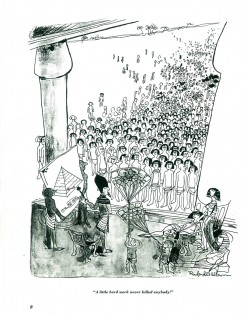

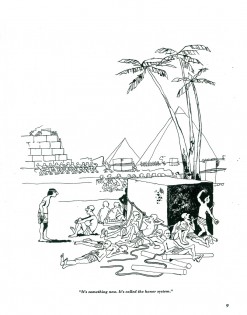

Images:

1. Book cover – Z is for Zagreb

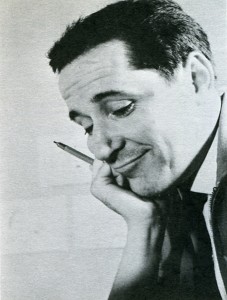

2. Zlatko Grgic

3. The Inventor of Shoes

4. Nedeljko Dragic

5. Tamer of Wild Horses

Bill Peckmann &Books &Illustration 26 May 2010 08:43 am

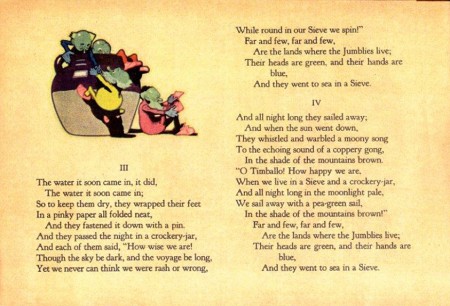

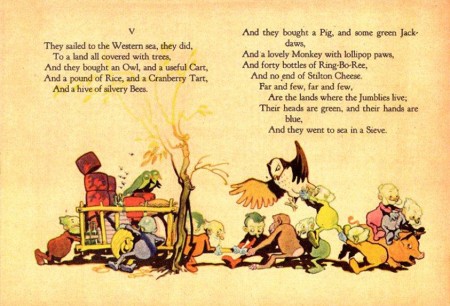

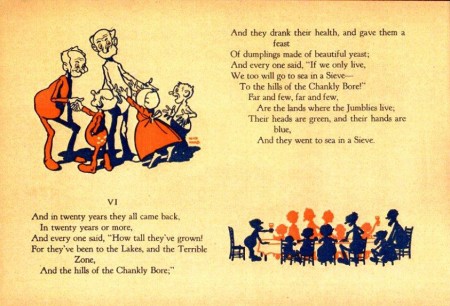

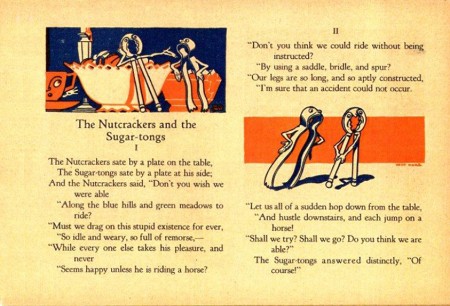

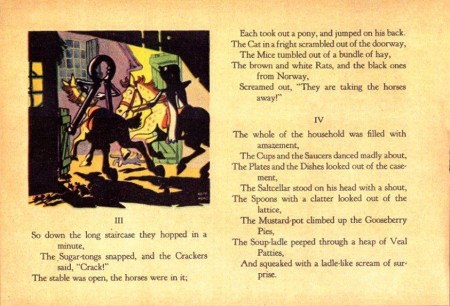

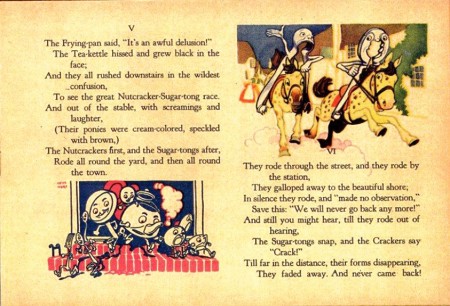

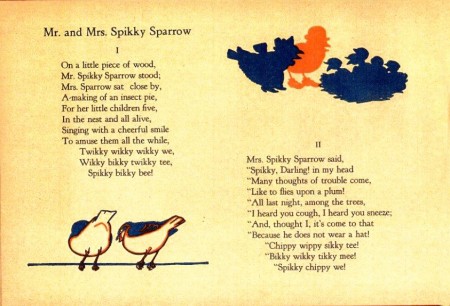

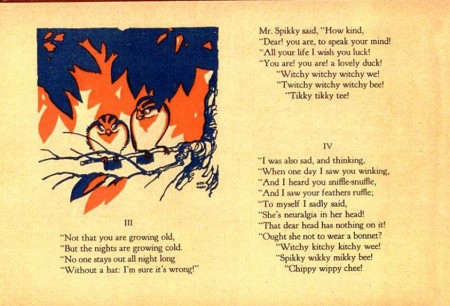

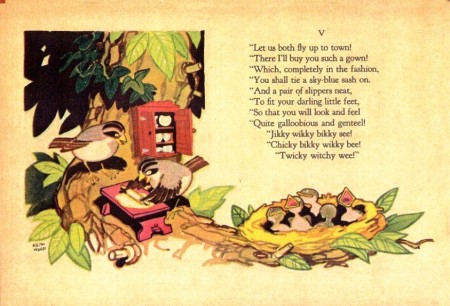

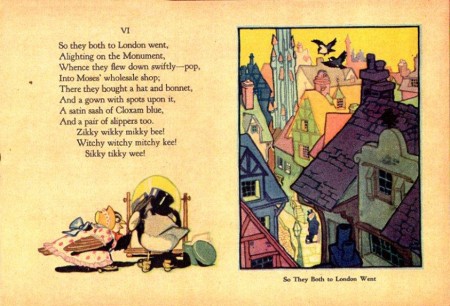

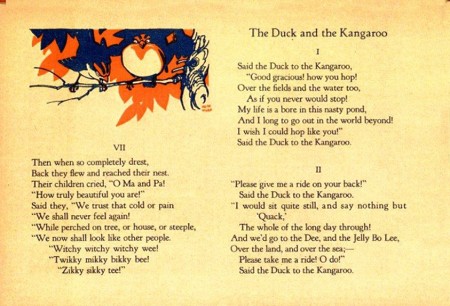

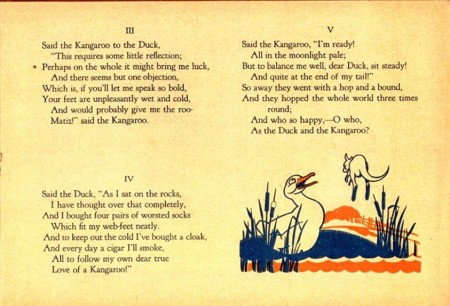

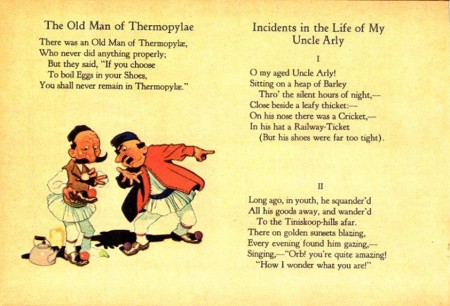

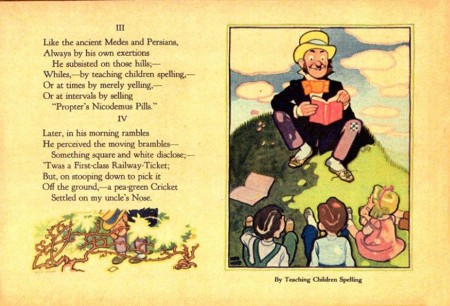

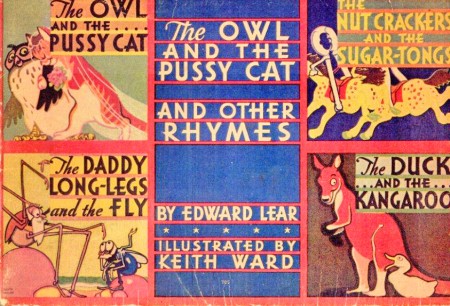

Edward Lear Nonsense – 1

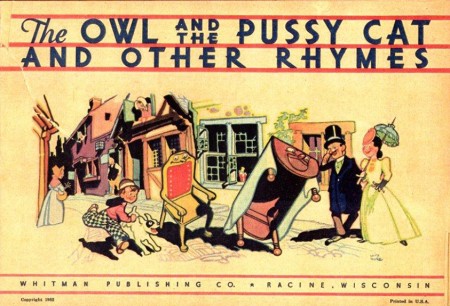

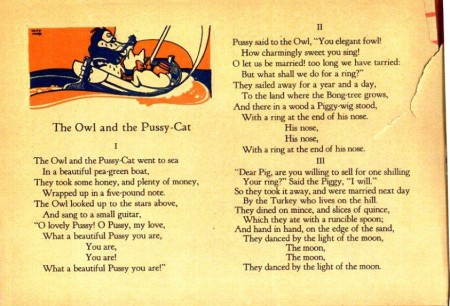

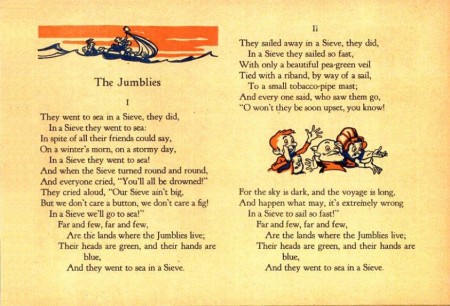

- I’ve been a fan of Edward Lear forever. When Bill Peckmann sent me this incredible book with these great illustrations by Keith Ward, I had to open it up to you. I hope you enjoy it. (By the way, I’ve tried to find out about Ward, but I keep coming up with a philospher in England who doesn’t fit the bill. If you know anything about him share. Bill Peckmann led me to this link.)

The book was published in 1922.

The book’s front cover.

By the way, the book is long, so it’ll come in a couple of parts.

Animation &Articles on Animation &Books &Independent Animation 20 May 2010 09:35 am

Zagreb’s Start

- Recently, I’ve tried to put a bit of focus on some International world leaders in animated film and give some attention to the heroes of the past. Naturally, Zagreb Film would be a source of many important names. This was a Yugoslavian studio that had limited resources and budget and they did the most with what they had. When their film, Ersatz, won the Oscar in 1961, it put this small studio on the map. Dusan Vukotic, the director of that film, led the studio.

Here’s a couple of small excerpts from a book, Z is for Zagreb by Ronald Holloway, that gives a good overall view of the start of the studio and a bit about Vukotic’ biography.

In the early Fifties, the Yugoslav economy was getting off the ground and business advertisements began to appear in the newspapers. The possibility arose again of producing publicity films, as the Maar Brothers had done successfully before the war. Besides, a staff of trained Duga personnel was becoming bored with comic strips and illustrations for books and magazines, and itched to get back into animation. When an English book store opened in Zagreb and news poured across Kostelac’s desk of UPA and Bob Cannon’s Gerald McBoing Boing, the itch became a torture. How were these beautifully designed cartoons made? There were no clues, but everyone was sure it was something for them.

Another break came in the least expected fashion. American films were being bought for Yugoslav consumption, and among those screened for selection was Irving Reis’s The Four Poster (1952). The film itself was not so important, but the animation bridges between sequences were. A sparking, tongue-in-cheek design by John and Faith Hubley graced the antics of Rex Harrison and Lili Palmer in the two-role film: it was the first UPA “cartoon” to enter the country. The film was screened by an excited small audience over and over, and then sent back to the source from which it came—unbought! Harrison and Palmer were never to know how important they were to the growth of Zagreb animation.

Another break came in the least expected fashion. American films were being bought for Yugoslav consumption, and among those screened for selection was Irving Reis’s The Four Poster (1952). The film itself was not so important, but the animation bridges between sequences were. A sparking, tongue-in-cheek design by John and Faith Hubley graced the antics of Rex Harrison and Lili Palmer in the two-role film: it was the first UPA “cartoon” to enter the country. The film was screened by an excited small audience over and over, and then sent back to the source from which it came—unbought! Harrison and Palmer were never to know how important they were to the growth of Zagreb animation.

With these innovations in mind a veteran group of cartoonists gathered around Kostelac and Vukotic to make advertising films on their own. Production manager was Kostelac, script and direction flowed from Vukotic, Marks (already an acknowledged graphic artist) did the designs, Jutrisa and Kostanjsek animated, and Bourek and Kolar painted the backgrounds. The money came out of their own pockets, but they were able to secure from Zagreb Film production and distribution help. Vukotic and Kostelac toured the country, and with the help of a fellow Montenegran Vukotic secured the necessary commissions from factories and business concerns. Then he and Kostelac retired to a hotel room with typewriter and drawing board to come up with a suitable idea. Thirteen advertising films, ranging in length from thirty seconds to one minute, were produced in the period 1954—55, eleven of them in colour.

Since material resources and particularly the availability of cels (transparent celluloids containing the drawings to be photographed) were limited, the process of “reduced animation” was discovered. Some films took an unbelievable eight cels to make, without losing any of the expressive movement a large number of eels usually required. Drawings were reduced to the barest minimum, and in many cases the visual effect was stronger than with twice the number of drawings. Marks and Bourek went out of their way to round up a number of artist friends to help solve complicated problems. Writers, architects, sculptors lent a creative hand whenever needed. The cartoons took on a daring, avant-garde surface, a strange character for a business enterprise. But not one of their commercial customers complained or rejected a film.

The freed drawings brought about by “reduced animation” cannot be underestimated. These were the forerunners of modern experimental television commercials, and although they appear commonplace today they were highly revolutionary in the Fifties. For the young Zagreb cartoonists the process provided a school of freedom, originality and invention. Every phase of the cartoon was broken down to its basic parts and tested and retested: script, design, background, musical accompaniment, editing, factors of rhythm and timing. By limiting the drawings the characters were freed from realistic movement and given a characteristic life of their own, thereby increasing the film’s tempo and enriching scenes with new forms of expression. Shades of meaning entered into the cartoon’s movements, details began to determine the action, and the preciseness of an expression drew its force from duration of time minutely calculated. A cartoon done at Duga Film normally required 12,000 to 15,000 drawings; reduced, it came down to 4,000 to 5,000 drawings. Further experiments uncovered new ways to compose a scene, paint a background, add a sound effect, construct a bold graphic, build a proper atmosphere, and finally edit tensions into the action to reach a satisfying whole. The only phase left untouched from the Duga days was the general direction of movement; everything else had somehow changed. And, most important of all, the character was no longer an anthropomorphic imitation.

The freed drawings brought about by “reduced animation” cannot be underestimated. These were the forerunners of modern experimental television commercials, and although they appear commonplace today they were highly revolutionary in the Fifties. For the young Zagreb cartoonists the process provided a school of freedom, originality and invention. Every phase of the cartoon was broken down to its basic parts and tested and retested: script, design, background, musical accompaniment, editing, factors of rhythm and timing. By limiting the drawings the characters were freed from realistic movement and given a characteristic life of their own, thereby increasing the film’s tempo and enriching scenes with new forms of expression. Shades of meaning entered into the cartoon’s movements, details began to determine the action, and the preciseness of an expression drew its force from duration of time minutely calculated. A cartoon done at Duga Film normally required 12,000 to 15,000 drawings; reduced, it came down to 4,000 to 5,000 drawings. Further experiments uncovered new ways to compose a scene, paint a background, add a sound effect, construct a bold graphic, build a proper atmosphere, and finally edit tensions into the action to reach a satisfying whole. The only phase left untouched from the Duga days was the general direction of movement; everything else had somehow changed. And, most important of all, the character was no longer an anthropomorphic imitation.

When they appeared in the cinemas, the fantastic, dynamic feeling inside these cartoons charmed the public. Former staff members couldn’t match the finished product with the number of cels used. More commissions began to roll in, and Zagreb Film took another look at the young innovators within the company. As the way opened for new production standards in 1956 (due to a new law separating Zagreb Film from its film distribution branch), it was decided to give story animation another try. The resourceful Kostelac pulled out of a sleeve a card file of former Duga employees, and rounded them up with a taxi and a knock on the door. Enough responded to begin work immediately on a story cartoon for the Pula Festival (another scheme of Fadil Hadzic to promote the growth of Yugoslav cinema), and they worked day and night on The Playful Robot. Script was by Andre Lusicic, direction by Vukotic, design by Marks and Kolar, animation by Jutrisa and Kostanjsek, backgrounds by Bourek—and mistakes by all. There was something basically Disneyish about this effort, and it was admittedly inferior to the high-powered antics of the characters in the ad films.

Nevertheless, Vukotic won a prize at Pula for pioneering Yugoslav animation, and Zagreb Film found itself with an animation studio.

Dusan Vukotic

(Born 1927 in Bileca).

The most important name in Yugoslav animation. It was through his drive and determination that the cartoon won respectability at home and recognition abroad. He has won over fifty prizes and citations for his sixteen major cartoons. He studied architecture and worked as cartoonist on Fadil Hadzic’s Kerempuh, moving up to head of his own unit under Hadzic at Duga Film in 1951—52. As director, designer and animator he created the national figure of Kico, a little government official on inspection tours about the country. How Kico was Born (1951) and The Haunted Castle at Dudinci (1952) represent the best work done at Duga Film, and drew their inspiration from Trnka’s Czech cartoons instead of Disney. After the collapse of Duga Film, Vukotic and Kostelac produced on their own homemade advertising films, and with Marks, Kolar and Bourek he discovered the principles of “reduced animation” (sharply limiting the number of drawings for a short cartoon). He made eleven advertising films as scriptwriter and director, distributed through Zagreb Film, and one publicity film. The Magic Catalogue (1956), for Dragutin Vunak at Interpublic. When Zagreb Film turned to the feature cartoon, Vukotic created The Playful Robot (1956) with the combined talents of Marks, Kolar, Kostanjsek, Jutrisa and Bourek, and was given the Golden Arena at the Pula Festival for pioneering animation in Yugoslavia. He fostered the satire in animation, aiming Cowboy Jimmie (1957), Concerto for Sub-Machine Gun (1958) and The Great Fear (1958) at the American Western, the gangster film, and the horror film. In the beginning he preferred to work with another designer, employing Marks on The Playful Robot, Cowboy Jimmie, and Magic Sounds (1957), and Kolar on Abra Kadabra (1957). The Great Fear, Revenger (1958), Concerto for Sub-Machine Gun, and My Tail is My Ticket (1959), and Grgic on Cow on the Moon (1959). He was the first in the studio to direct, design and animate independently, winning a number of awards for Piccolo (1959) and establishing his characteristic theme of feuding neighbours. His next two

The most important name in Yugoslav animation. It was through his drive and determination that the cartoon won respectability at home and recognition abroad. He has won over fifty prizes and citations for his sixteen major cartoons. He studied architecture and worked as cartoonist on Fadil Hadzic’s Kerempuh, moving up to head of his own unit under Hadzic at Duga Film in 1951—52. As director, designer and animator he created the national figure of Kico, a little government official on inspection tours about the country. How Kico was Born (1951) and The Haunted Castle at Dudinci (1952) represent the best work done at Duga Film, and drew their inspiration from Trnka’s Czech cartoons instead of Disney. After the collapse of Duga Film, Vukotic and Kostelac produced on their own homemade advertising films, and with Marks, Kolar and Bourek he discovered the principles of “reduced animation” (sharply limiting the number of drawings for a short cartoon). He made eleven advertising films as scriptwriter and director, distributed through Zagreb Film, and one publicity film. The Magic Catalogue (1956), for Dragutin Vunak at Interpublic. When Zagreb Film turned to the feature cartoon, Vukotic created The Playful Robot (1956) with the combined talents of Marks, Kolar, Kostanjsek, Jutrisa and Bourek, and was given the Golden Arena at the Pula Festival for pioneering animation in Yugoslavia. He fostered the satire in animation, aiming Cowboy Jimmie (1957), Concerto for Sub-Machine Gun (1958) and The Great Fear (1958) at the American Western, the gangster film, and the horror film. In the beginning he preferred to work with another designer, employing Marks on The Playful Robot, Cowboy Jimmie, and Magic Sounds (1957), and Kolar on Abra Kadabra (1957). The Great Fear, Revenger (1958), Concerto for Sub-Machine Gun, and My Tail is My Ticket (1959), and Grgic on Cow on the Moon (1959). He was the first in the studio to direct, design and animate independently, winning a number of awards for Piccolo (1959) and establishing his characteristic theme of feuding neighbours. His next two  independent cartoons were also highly awarded: Ersatz (1961), winning the first Academy Award for animation outside the United States, and Play (1962), voted the best short film of the year at Mannheim. Turning to the feature film, his The Seventh Continent for children in 1966 was not successful but it encouraged him in the cartoon to continue the mixture of live action and animation begun in Play. Stain on the Conscience (1968) employed animation drawing on documentary footage and proved him capable of directing actors ; in a psychological atmosphere. Opera Cordis (1968) restored his eminent position in animation with a salty commentary on Dr. Barnard’s heart transplants, and Ars Gratia Art/s (1 969) more than effectively spoofed the amateur who will do anything for the sake of art and applause. He also wrote the scripts for Vrbanic’s All the Drawings of the Town (1959) (with Vrbanic), Gospodnetic’s The Lion Tamer (1961), Dovnikovic’s The Doll (1961), Grgic’s A Visit from Space (1961), and Blazekovic’s Gorilla’s Dance (1968), and had a hand in supervising most of these films as well as Grgic’s The Devil’s Work (1965). His gifts as a leader are evident every step of the way, but particularly in the first phase of Zagreb Film (1956— 62) when his unit competed for honours with Mimica’s and Kristl’s. He is best in the cool domains of satire and caricature.

independent cartoons were also highly awarded: Ersatz (1961), winning the first Academy Award for animation outside the United States, and Play (1962), voted the best short film of the year at Mannheim. Turning to the feature film, his The Seventh Continent for children in 1966 was not successful but it encouraged him in the cartoon to continue the mixture of live action and animation begun in Play. Stain on the Conscience (1968) employed animation drawing on documentary footage and proved him capable of directing actors ; in a psychological atmosphere. Opera Cordis (1968) restored his eminent position in animation with a salty commentary on Dr. Barnard’s heart transplants, and Ars Gratia Art/s (1 969) more than effectively spoofed the amateur who will do anything for the sake of art and applause. He also wrote the scripts for Vrbanic’s All the Drawings of the Town (1959) (with Vrbanic), Gospodnetic’s The Lion Tamer (1961), Dovnikovic’s The Doll (1961), Grgic’s A Visit from Space (1961), and Blazekovic’s Gorilla’s Dance (1968), and had a hand in supervising most of these films as well as Grgic’s The Devil’s Work (1965). His gifts as a leader are evident every step of the way, but particularly in the first phase of Zagreb Film (1956— 62) when his unit competed for honours with Mimica’s and Kristl’s. He is best in the cool domains of satire and caricature.

Images:

1. The Four Poster – from Amid Amidi‘s Cartoon Modern

2. Cowboy Jimmie

3. Dusan Vukotic

4. Ersatz

Bill Peckmann &Books &Illustration 19 May 2010 08:39 am

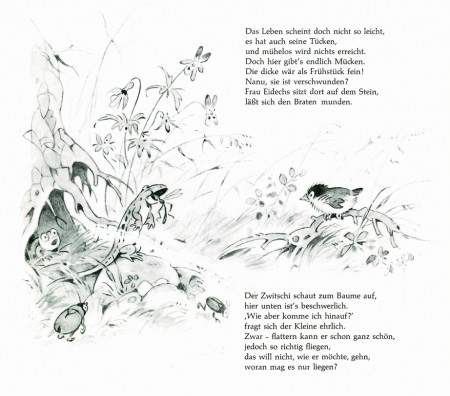

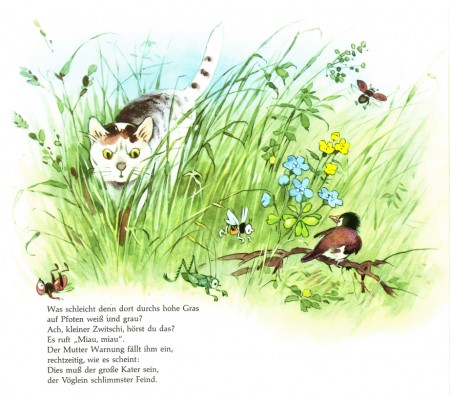

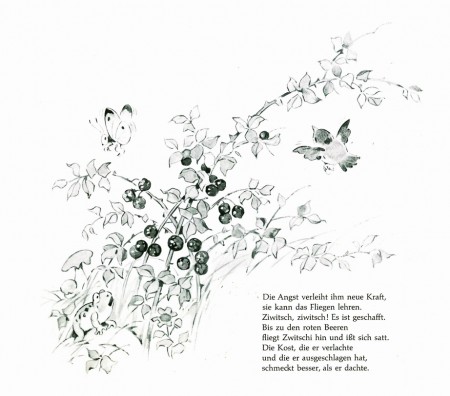

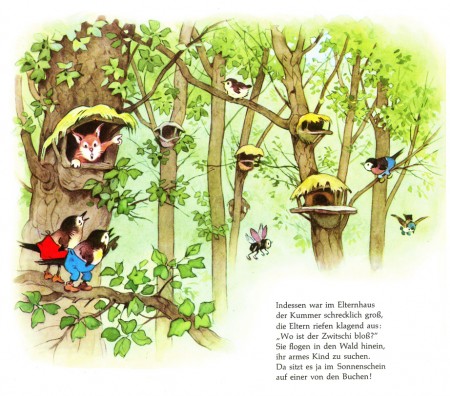

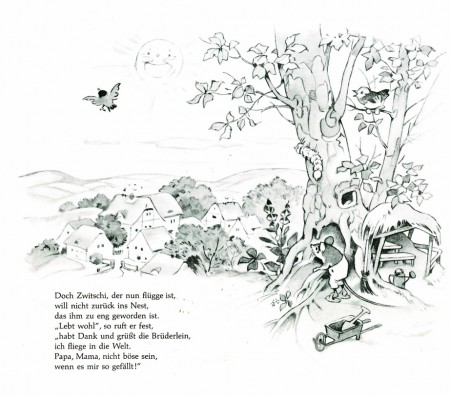

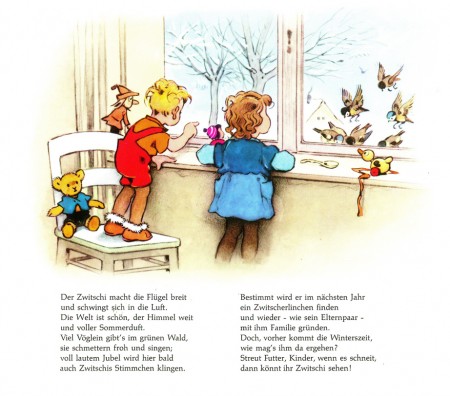

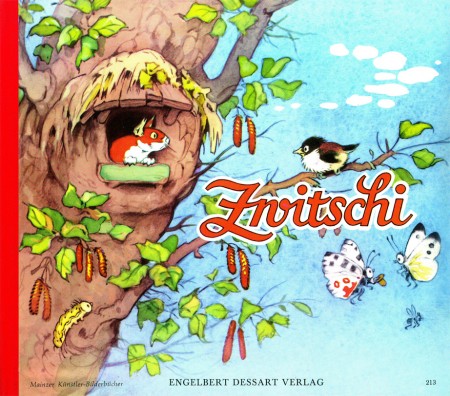

Zwitschi

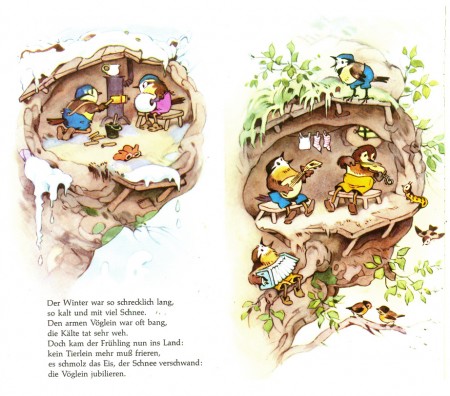

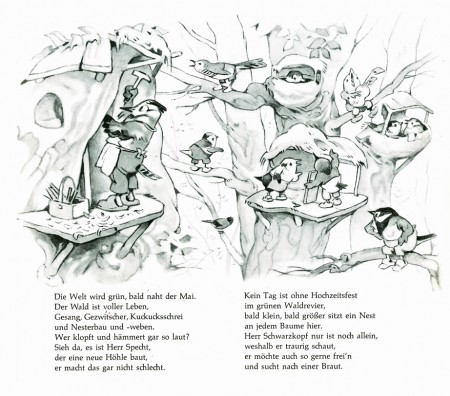

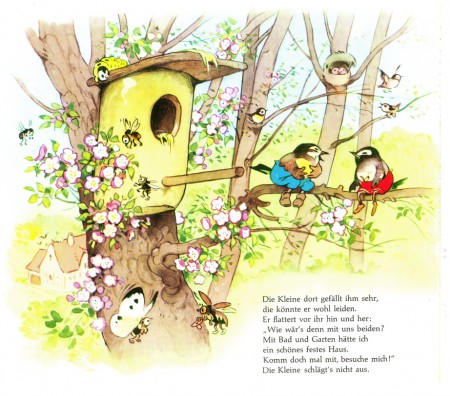

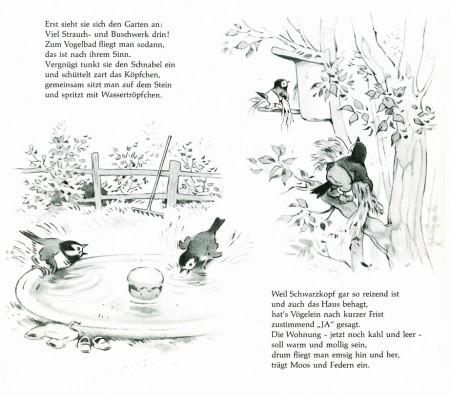

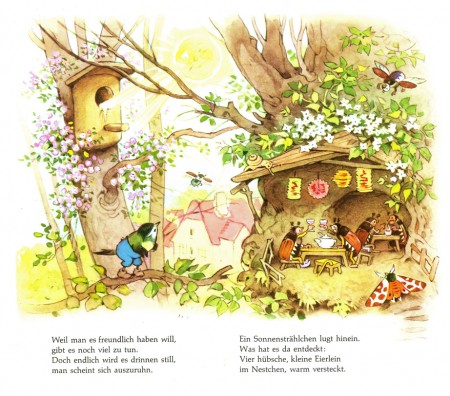

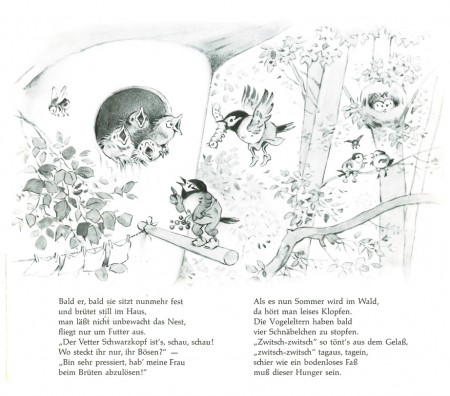

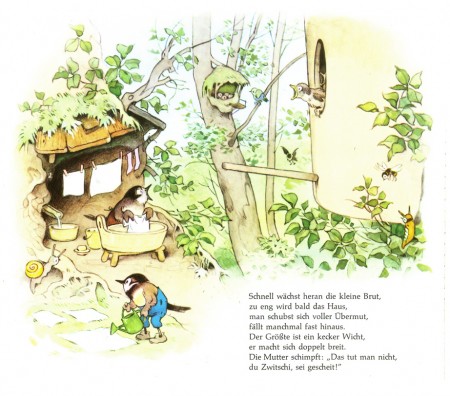

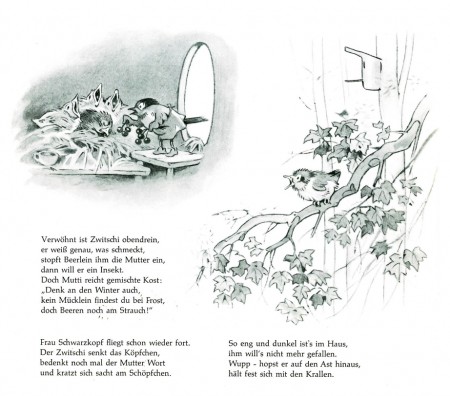

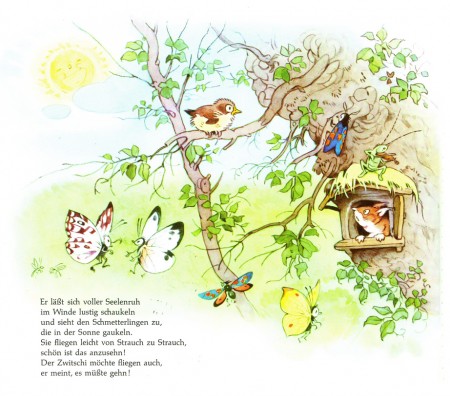

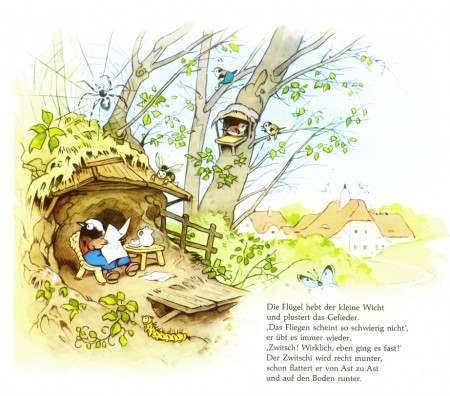

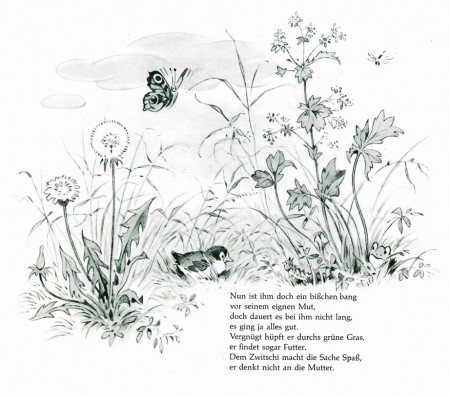

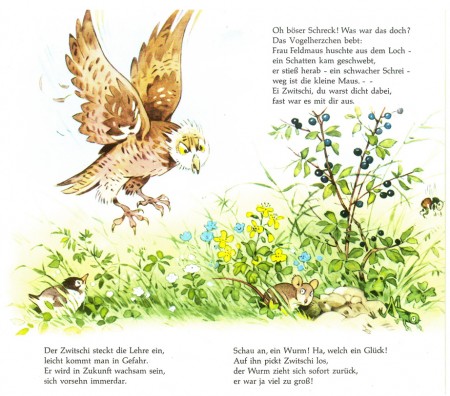

- Bill Peckmann recently introduced me to a fabulous German illustrator, Fritz Baumgarten, who’s created many beautiful children’s books. They feel as though they come from an earlier generation. Baumgarten died in 1966, so in a sense they are, but they feel more like the 30s and 40s – Snow White.

I’d like to post one of them, written by Liselotte Burger von Dessart. Zwitschi.

cover

cover(Click any image to enlarge.)

I’ll have another book by Baumgarten soon. Thanks to Bill Peckmann.

Bill Peckmann &Books &Illustration &Rowland B. Wilson 16 Apr 2010 10:23 am

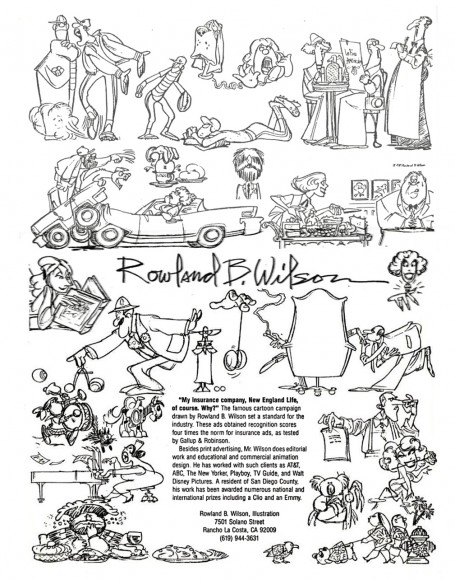

Rowland Wilson’s Whites – 2

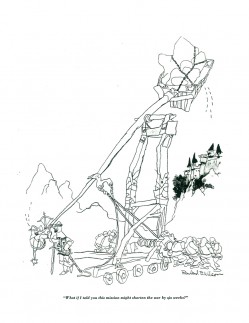

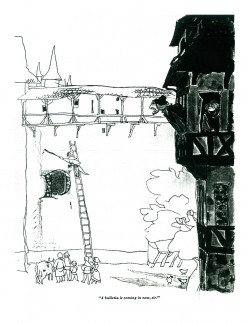

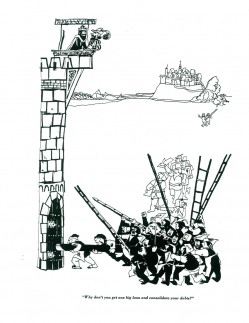

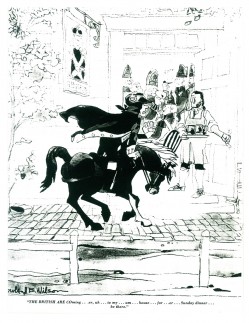

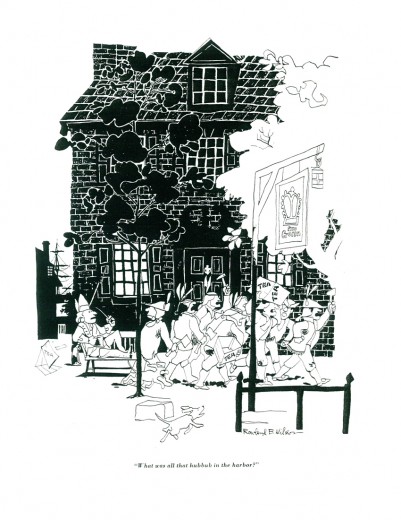

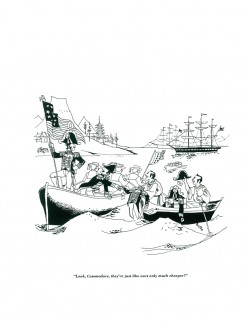

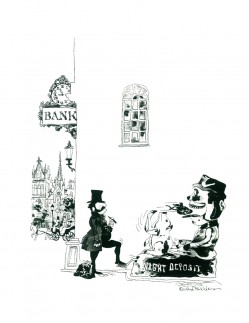

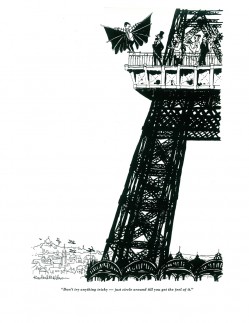

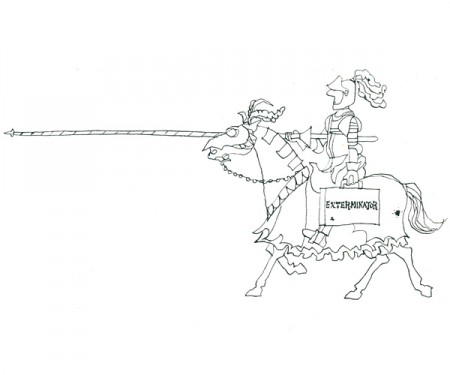

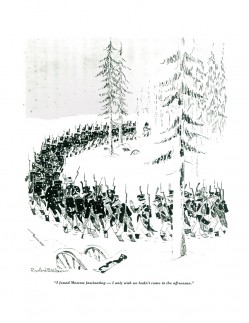

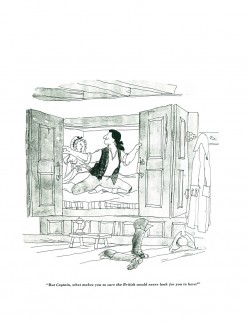

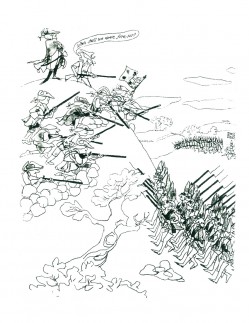

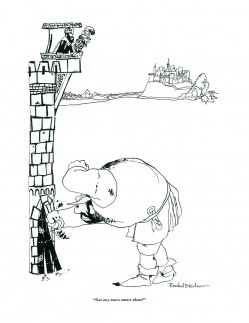

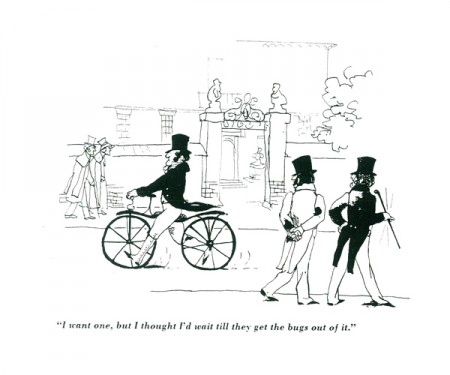

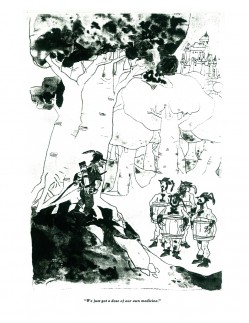

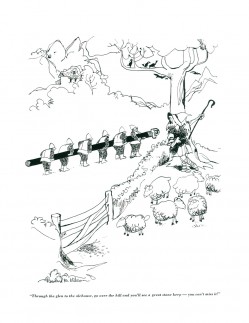

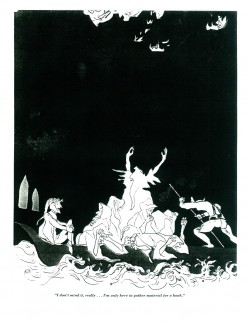

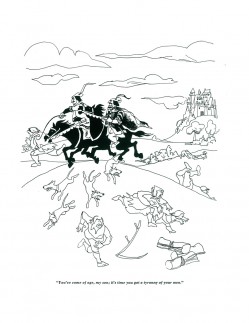

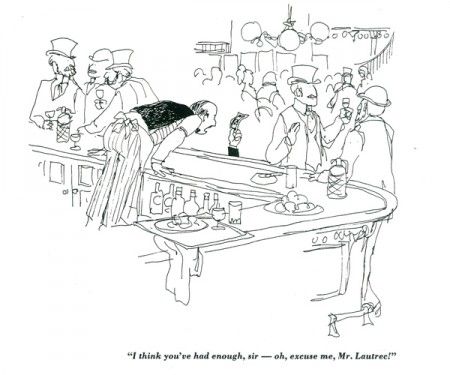

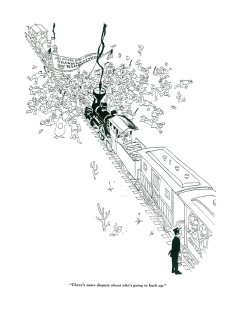

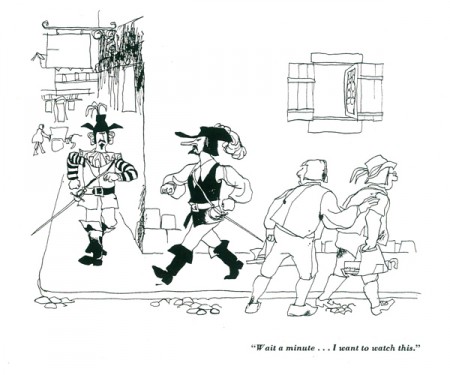

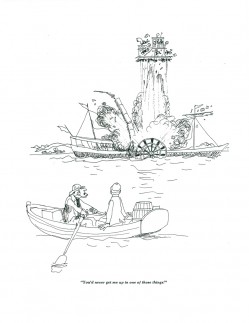

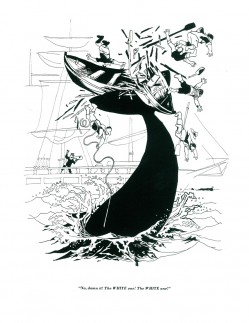

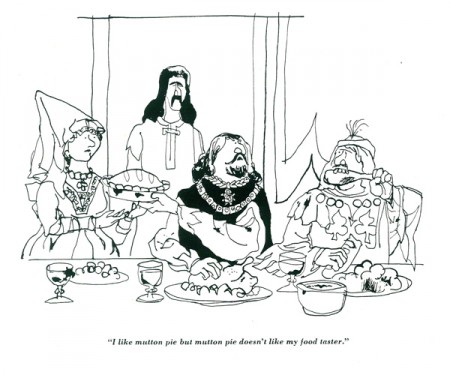

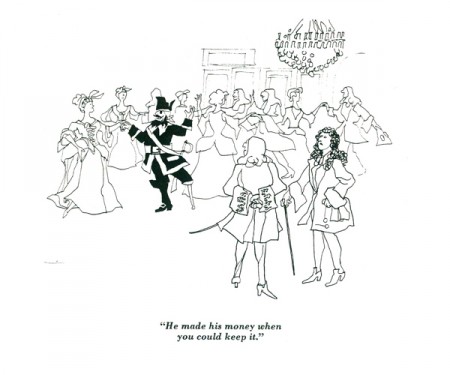

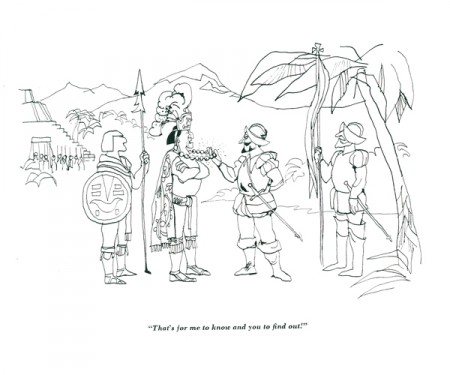

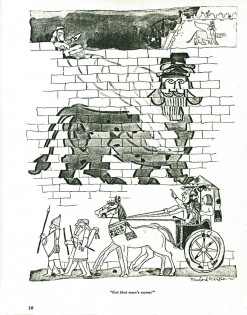

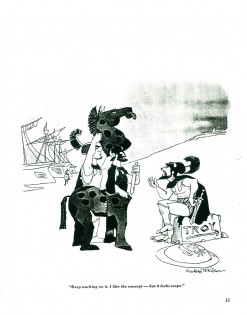

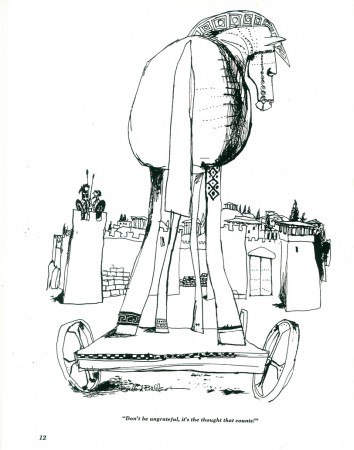

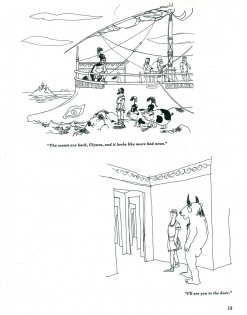

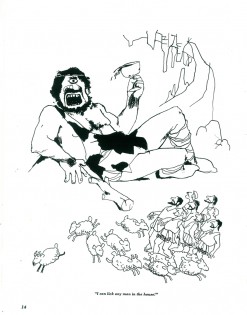

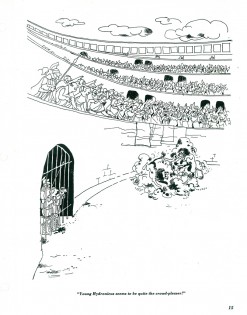

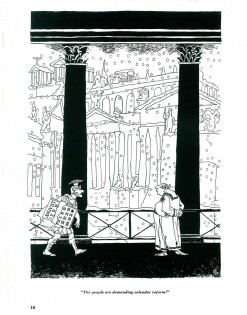

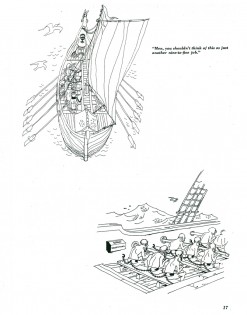

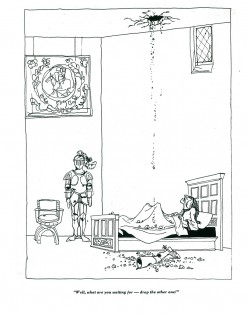

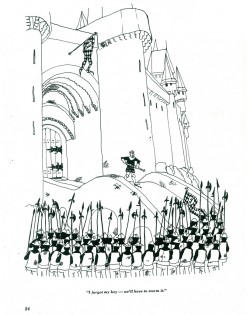

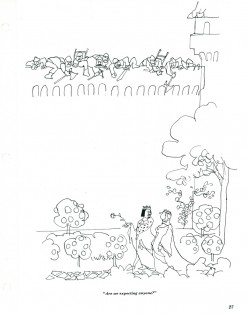

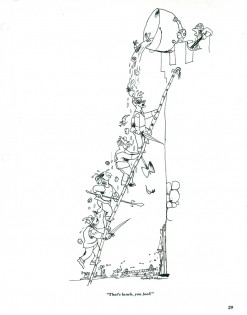

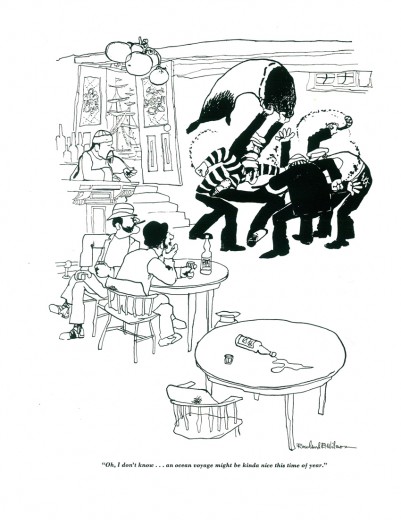

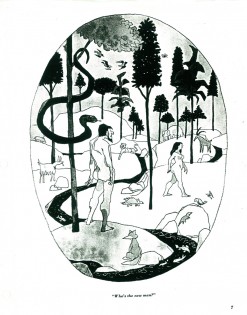

I posted part of Rowland B. Wilson‘s book, The Whites of Their Eyes, two weeks ago. (Go here to see that post.) This book was published in 1962 by Dutton and displays in B&W many of the Wilson cartoons up to that time. The display is not always glorious, but it is the only printed copy of any of his panel cartoons. Consequently, we have to be grateful for what we have.

These cartoons are xeroxed copies from Bill Peckmann‘s large collection of Rowland’s work. I’m grateful for his loan of these illustrations to post here.

(Click any image to enlarge.)

Bill Peckmann &Books &Illustration &Rowland B. Wilson 09 Apr 2010 07:20 am

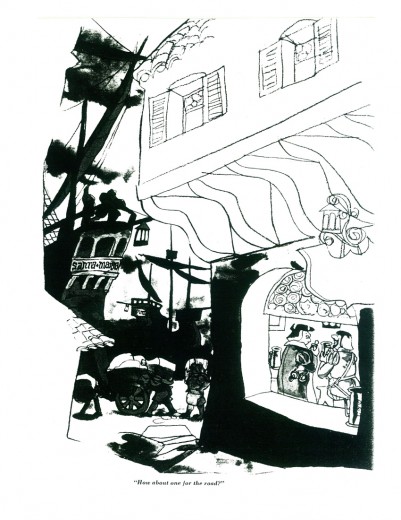

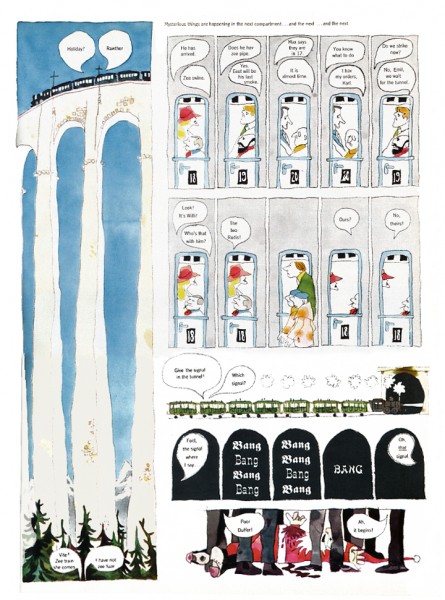

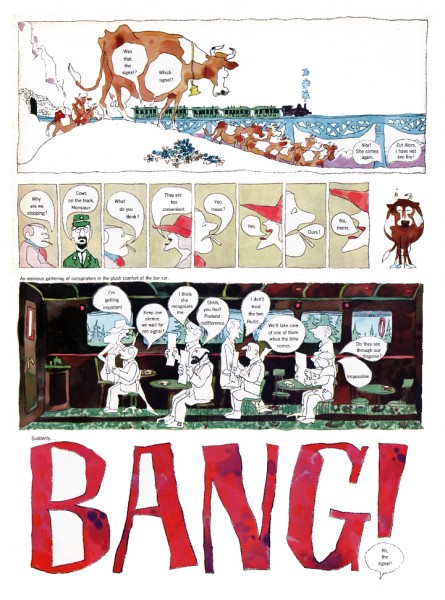

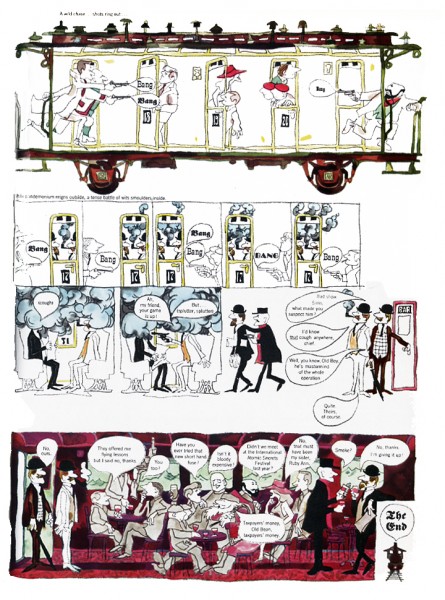

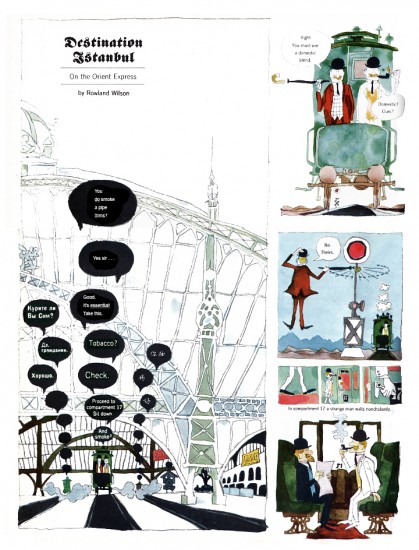

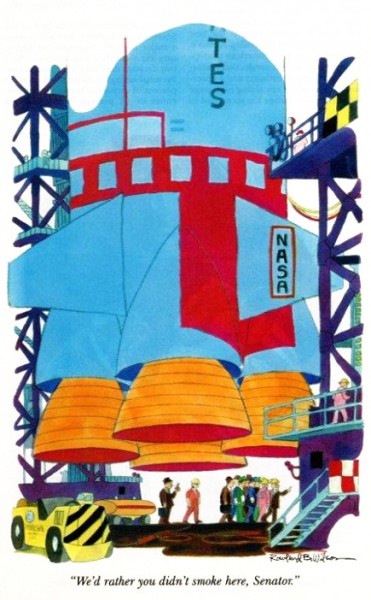

RBW – color Istanbul & more

Rowland B. Wilson‘s Istanbul Express appears in his book The Whites of Their Eyes which was published by Dutton in 1962. However it’s in B&W and appears relatively small size. Hard to read. Denis Wheary, a first rate collector and authority on Rowland B. Wilson’s work, has kindly photographed the original Esquire publication in color and has sent these photos to me. Using some heavy photoshop work, I was able to clean up the photos to a very presentable shape. Here are the four pages.

1

1(Click any image to enlarge.)

Here’s a color cartoon right out of Playboy courtesy of Bill Peckmann.

Also from Bill Peckmann’s outstanding collection of Rowland Wilson art is this flyer Rowland designed to promote himself.

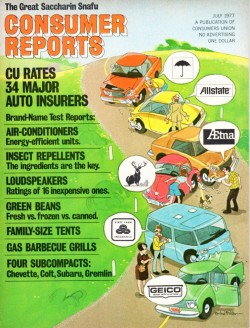

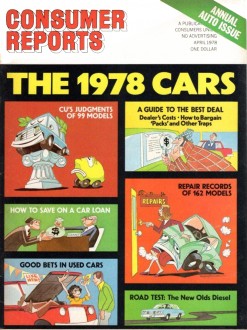

Here are a pair of Consumer Reports covers done by RBW.

I suggest you click to enlarge to check out all the detail.

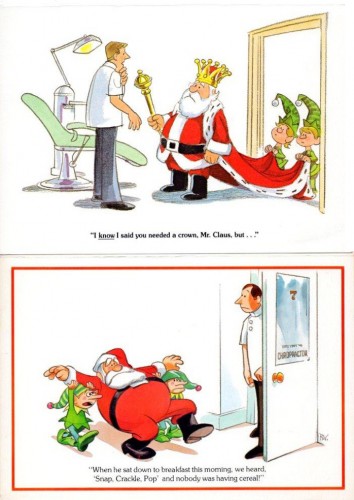

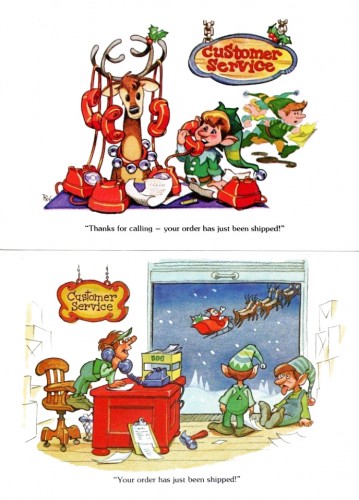

Here are a pair of Christmas cards RBW did

for some Customer Service center.

Bill Peckmann &Books &Illustration &Rowland B. Wilson 02 Apr 2010 08:21 am

Rowland Wilson’s Whites

- Last week, I’d posted some dragon models that Rowland B. Wilson did for animation company Phil Kimmelman & Ass. for ‘Utica Club Beer’. Well, it turns out Rowland liked the model enough that he kept this painting on the wall in his studio at home. The color image was sent to Bill Peckmann, who shares it with us, by Suzanne Wilson, Rowland’s wife.

This is the model posted last week.

All that I can follow that up with are more Rowland B. Wilson cartoons. Bill Peckmann had sent me a xerox copy of the book The Whites of Their Eyes, a collection of RBW cartoons printed in 1962 by Dutton. The copies are all B&W though it’s obvious some of them were printed in color. Many thanks to Bill for another great post featuring one of my favorite artists.

1

1  2

2(Click any image to enlarge and read.)

Animation &Books 31 Mar 2010 09:37 am

Whitaker cycles

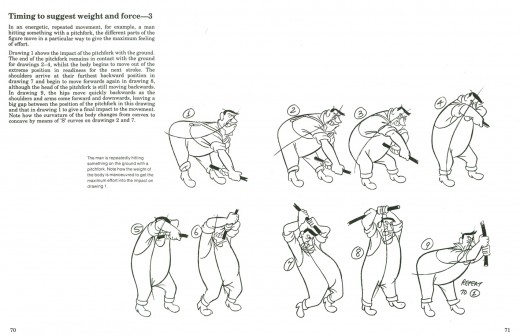

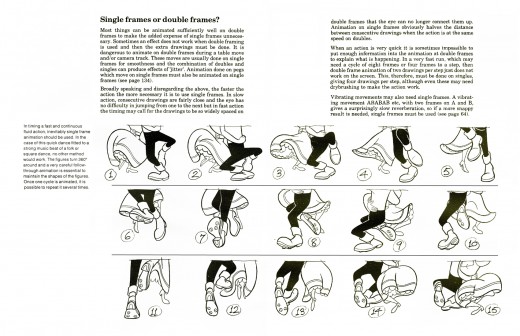

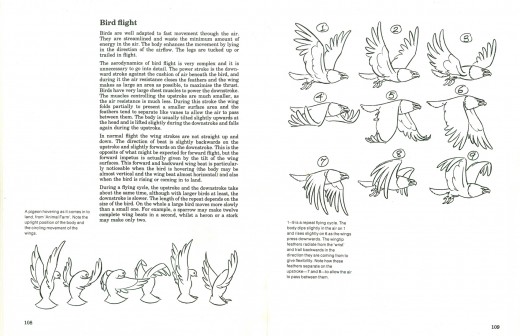

- On Saturday last, I spoke briefly about Harald Whitaker“s book Timing for Animation. (Recently updated with some additional information from Tom Sito. Unfortunately, I don’t have the updated version, so these pages came from the original printing.)

After writing that, I decided to try making QT movies of a couple of the cycles in the book. It’s one thing to see how a master animates actions in place via the drawings; it’s another to see how it actually moves.

Hence, I’ve taken three of the pages from the book, broken down the drawings and dragged them through AfterEffects putting all of the motions on twos.

This beautiful action perfectly and simply breaks down a

difficult motion. It’s quite alive and masterful, if you ask me.

The following motion was exposed on twos.

Click left side of the black bar to play.Right side to watch single frame.

The second motion is a dance. Whitaker uses it as an example of why things are exposed on ones or twos. I went against his lesson

and did the QT on twos. I wanted you to see the movement more

clearly (there’s a small jump from the last drawing back to the first.

The following motion was exposed on twos.

Click left side of the black bar to play.Right side to watch single frame.

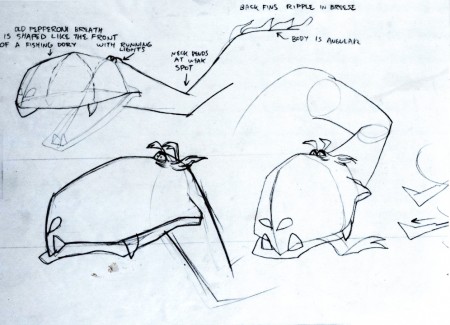

This third lesson is about a basic bird flight pattern.

He’s animated a larger bird. If it were smaller the body

of the bird would also be moving up and down.

The following motion was exposed on twos.

Click left side of the black bar to play.Right side to watch single frame.

This is an excellent book. If you don’t own it, it’s worth every cent of it’s price. Buy it.

Books &Commentary &Richard Williams 11 Mar 2010 08:58 am

Dick Williams’ Survival Kit

- Richard Williams, as we all know, was the genius who single-handedly fostered the renaissance of animation in the 60s & 70s. His London studio became the center of animation when the Disney studio faltered for that period.

- Richard Williams, as we all know, was the genius who single-handedly fostered the renaissance of animation in the 60s & 70s. His London studio became the center of animation when the Disney studio faltered for that period.

Or maybe we only know him as the author of that book, The Animator’s Survival Kit. That’s the book in which he has put his immense knowledge about the technique of animation, and there’s also his series of DVD lectures. Or maybe it’s the series of lectures and the companion book.

Recently released is the revised edition of the book which is at least 40 pages longer and includes a sample DVD to give an idea of his lecture series.

Both books are identical until page 339, the new book expands on the original. It talks about what Williams calls, “. . . the more difficult areas of animation,” such as animal action and gaits and offers suggestions on how to correctly use live action, to help push the medium further. (No mention is made of Motion Capture.) In fact, there’s a long piece comparing use of semi-realistic to cartoon animation.

The book says it’s for all types of animation from 2D to cg from puppet to highly rendered. However, to me, it feels more inclined to speak to the 2D drawing animator. I’m sure there are a lot of lessons the cg animator can and should take from the book, but I’m not sure how much use will be made of it.

Some of the lessons are excellent, but I wonder if others aren’t too sophisticated for those who will use the book to actually learn the craft. In fact, at first glance it looks like the Preston Blair book on acid, but Dick goes into a discussion about the Blair book and then builds on it, taking the material into a very complicated world. The delight is that Dick never sees his lessons as compicated, but moves straight on assuming we’ll all follow. The pages are hand lettered for the final 2/3 of the book, and this is particularly inviting for the artists out there. Howver, the drawings are dense with information and material and should not be confused with anything less than what they are. Richly informative.

a

a  b

b

At first glance, the book looks like an update of the Preston Blair book, but

Dick takes on that point and builds from there leaving no doubt for the reader.

c

c  d

d

The additions are literally added to the end. 40 odd pages that are devoted

to more compicated motion patterns or things Dick left out the his original book.

It’s quite a tool if you use it well. A course, in itself, within the 380 pages. Every dedicated animator should own one, and then they own it they should read it.