Search ResultsFor "Grim Natwick"

Daily post 13 Nov 2013 01:00 am

Good Will and Great Cartoons

Yesterday’s blog post was something I needed to write for myself.

Animation, as far as I can see hasn’t been going as well as I’d like. The good films have been few and far between.

During my career, I’ve been asked to be involved in a number of fine films. However, it’s the luck of the draw to be involved in good movies, also the power of your own abilities. I can’t tell you how many films, bad films, that have requested my help and participation. Also good films. They’ve been few and farther between, but they’ve been there.

The moment Weston Woods asked me to work on The Man Who Walked Between the Towers I knew this was a good one. It took me about five seconds to read the script and know it was great, and I knew I was working on a winner. There are other films that had the opposite reaction for me, and I was correct there as well.

Yesterday I wrote about a film I was asked to participate in. I knew the very second I saw the project that it would make a great film. None of the story stuff I wrote about – 60,000 flyer pilots (just a metaphor) coming to the rescue – was actually in the film. But the result is the same. The film is a feel good moment, and I know it will make a very good film. Even, god help me, if I’m not allowed to be part of it. It’s a good movie with a good story line. I just hope I am part of it, because I like it enormously.

-

My point, here, is this. Please allow me the use of Miyazaki for my example. The man is a good = no, take that back, a great filmmaker. He not only knows a good film, but he knows how to make them better. The films ha makes become automatically better. He has something to say; he finds curious and complicated ways of telling those stories, and when he is part of a project he gets the most of the story.

He knew he had to make it a children’s film with the simplest of story directions. He had to reach the largest possible audience and be direct. He was, and the film he made was an unmitigated success.

With The Wind Rises he has made an adult film it’s the only way he could tell this tale. He also complicates the structure of the story, and despite the fact that he will not get the largest possible audience, he wants to be sure every aspect of the complicated story is told. This he does. He ignores a large section of the audience for the sake of making a richer story.

His work on the two films, in my mind, can only be seen as the work of a genius. His story is as full as it can ever become, yet he disappoints a small part of the audience searching for the obvious. I can only credit the man, the artist. I also take away very deep lessons about his artistry and what he wanted to do with it. I’ve seen Ponyo half a dozen times with full joy. With The Wind Rises, occurring post Tsunami and post nuclear meltdown, I am sure he has plenty to tell me, and I will see it again and again until I’ve gotten all of its pleasure.

Most prominently I believe he wants to be heard about man’s inhumanity to man. Despite all the natural disaster and chaos in our lives, he uses a man intent on carrying out the best war to get the full tale told. His method is enough to make me tear up, his story goes even deeper.

-

So back to that film that I praised last night. The one that asked me participate in telling a sad and deep story. I am beside myself with joy at having been asked. I hope I remain connected with it. I am honored at having been asked. If I am allowed to continue with it, I will do my very best. If I am not allowed to continue through to the end,I’ll watch and have my opinion, and that’s one opinion I’ll keep to myself.

It’s been a few days since I posted some artwork. Here are some piece I repost which were taken from the collection of Vincent Cafarelli. I’m curently sitting in his desk at Buzzco, so I’d like to see more of the great art that passd his way during the heyday of the commercial in NYC.

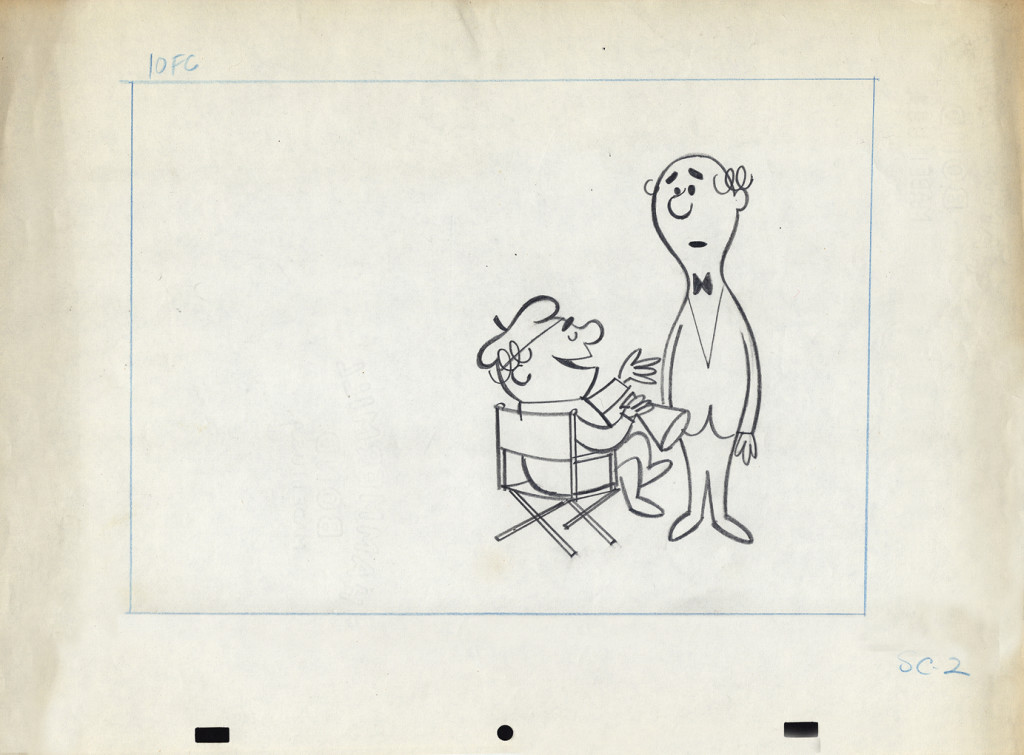

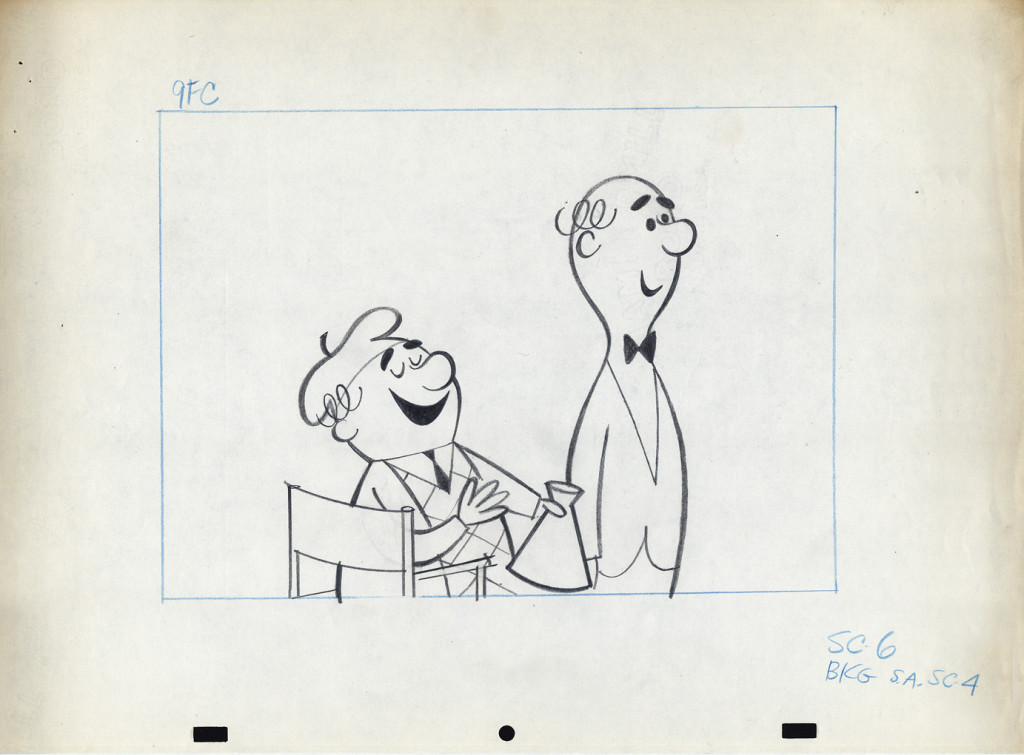

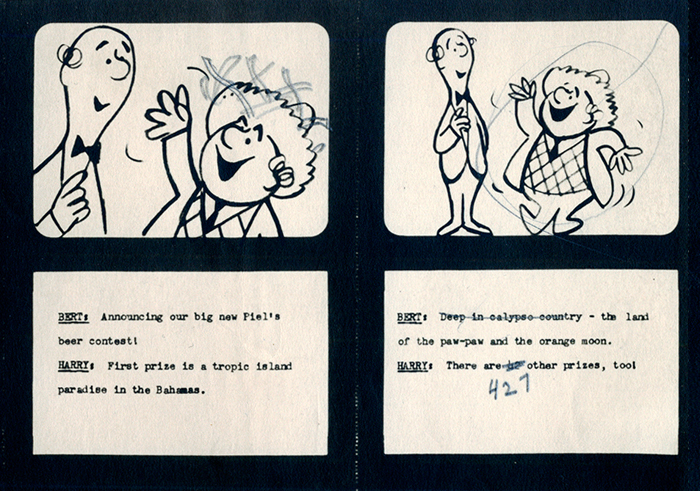

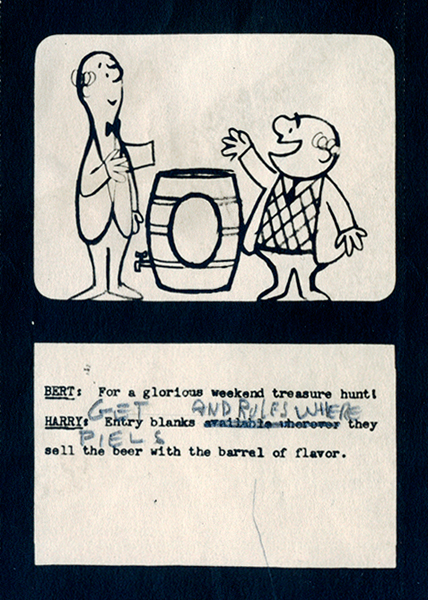

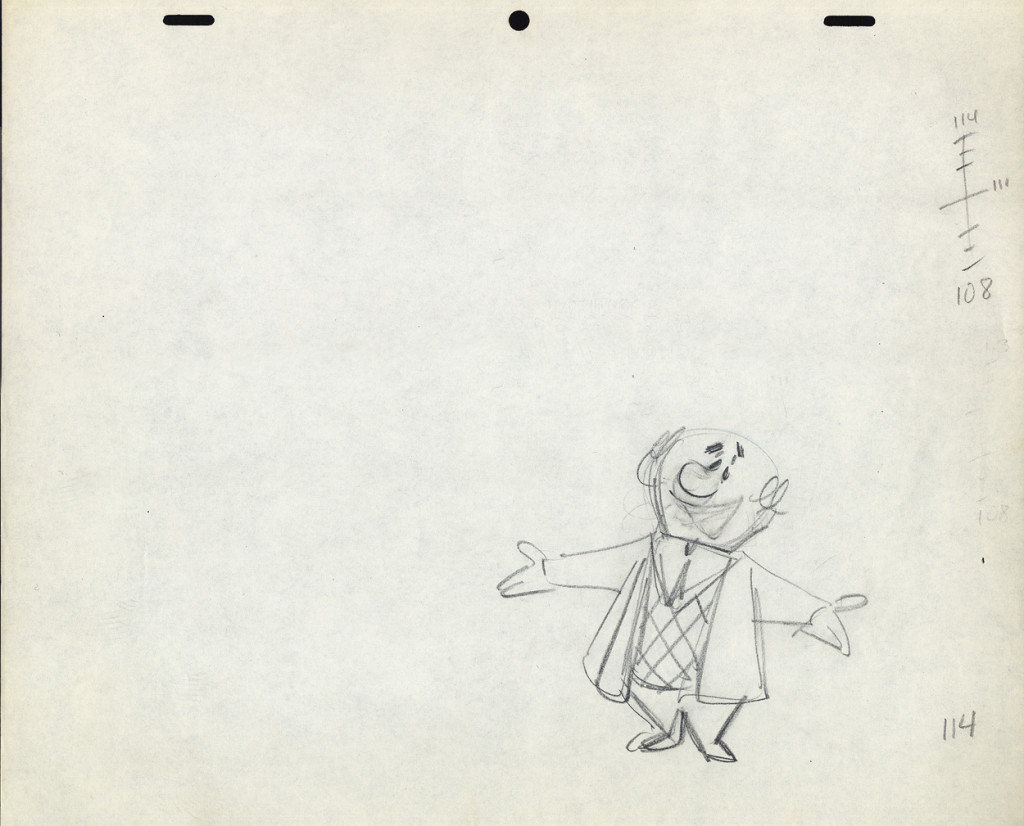

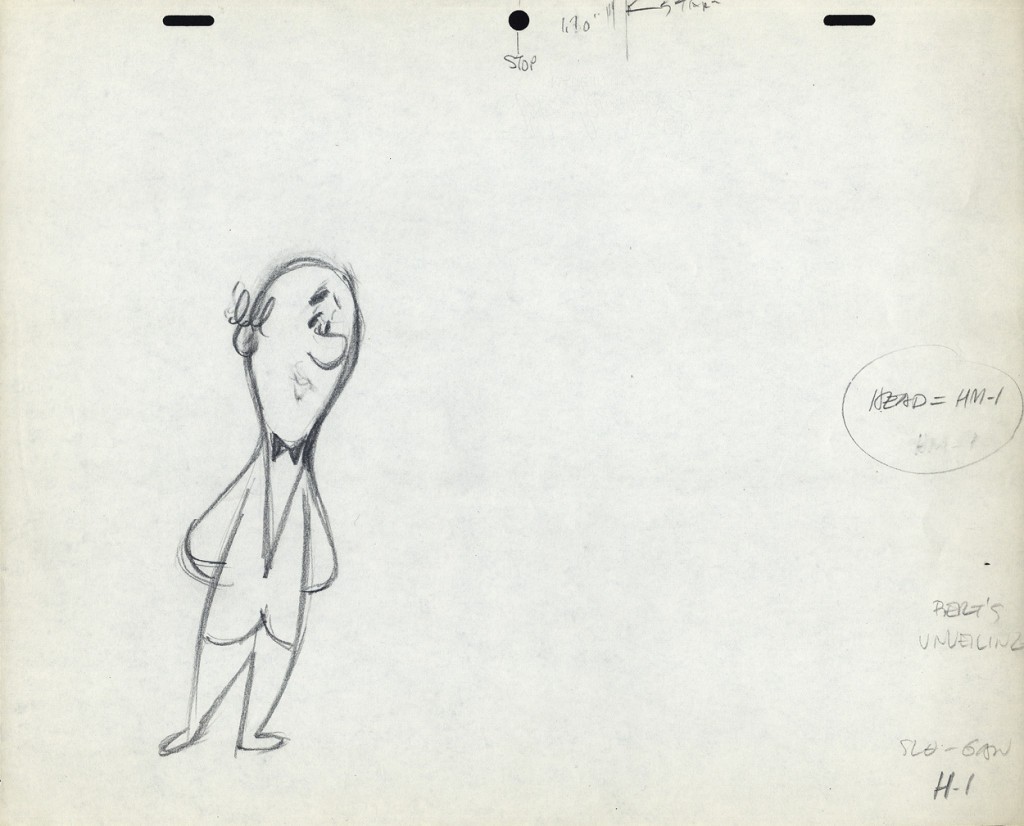

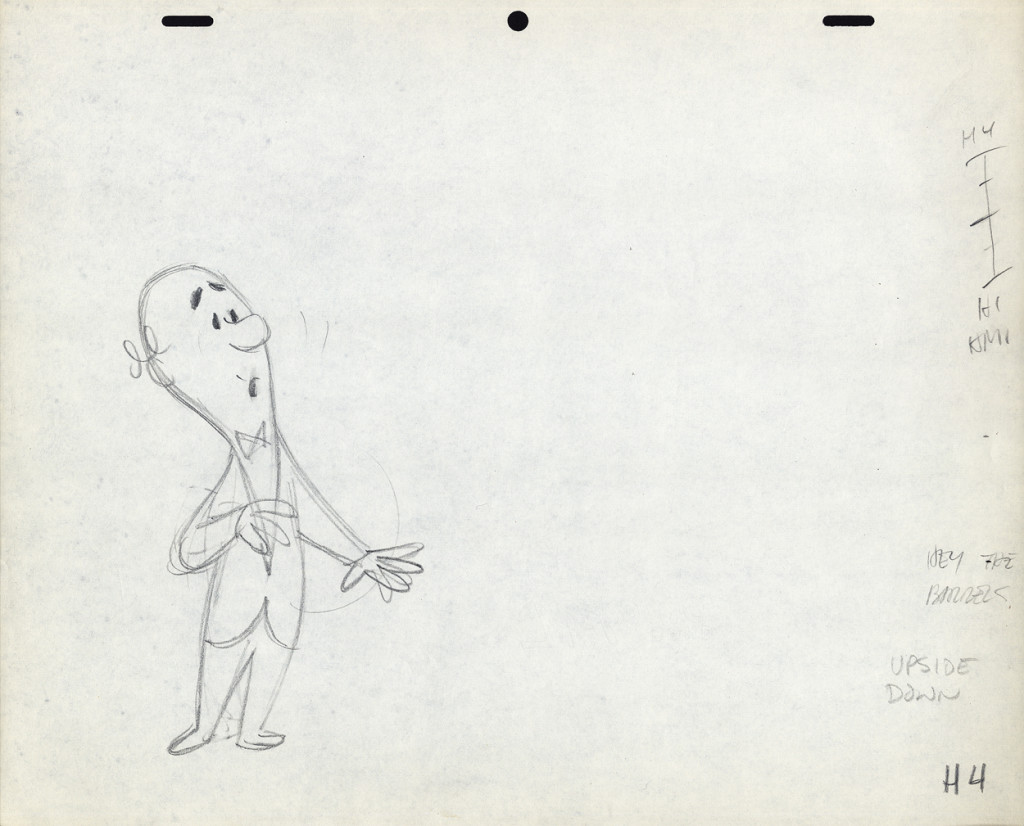

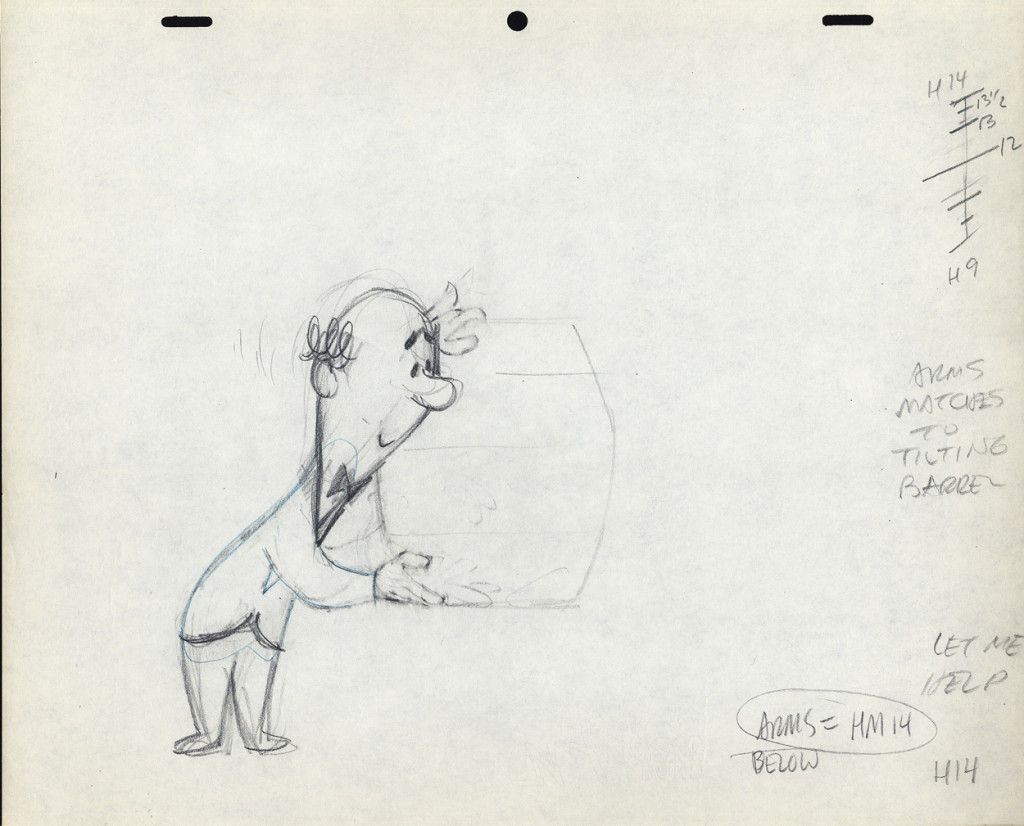

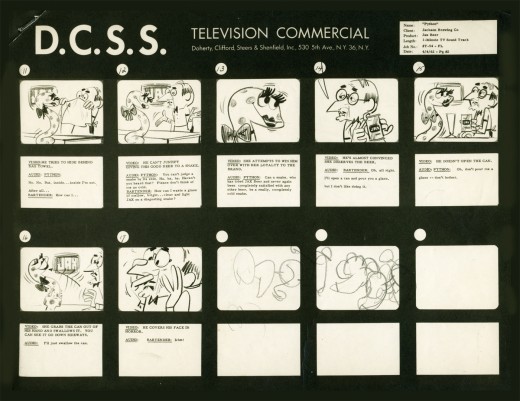

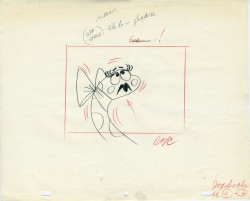

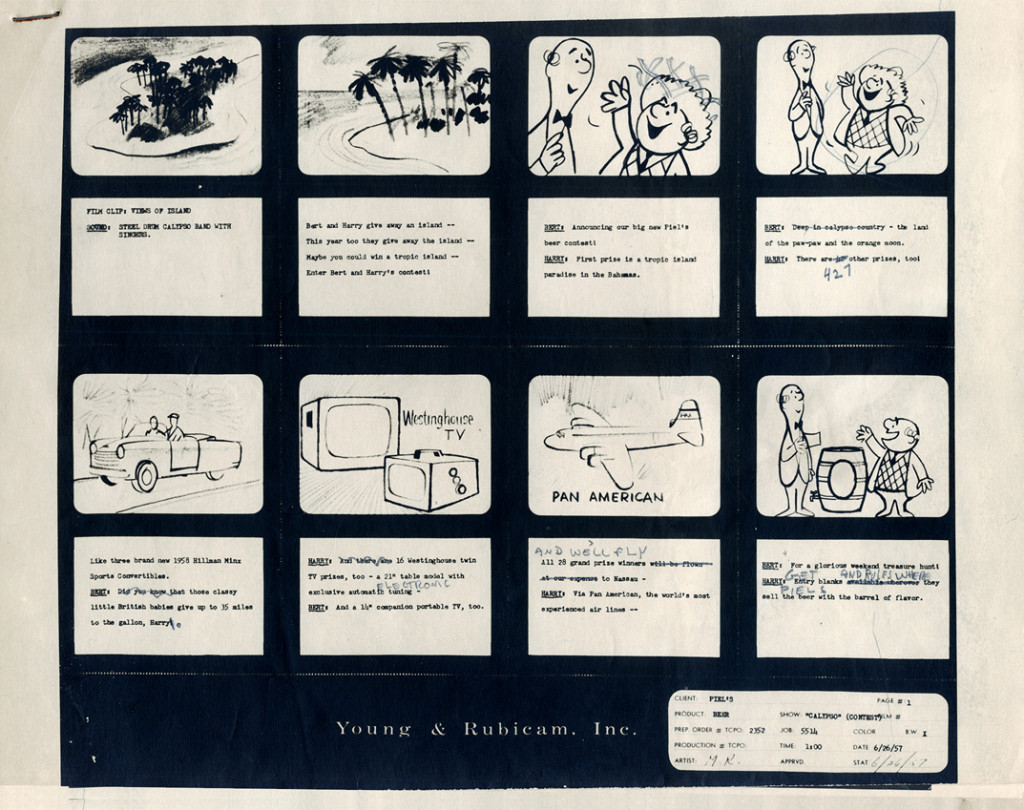

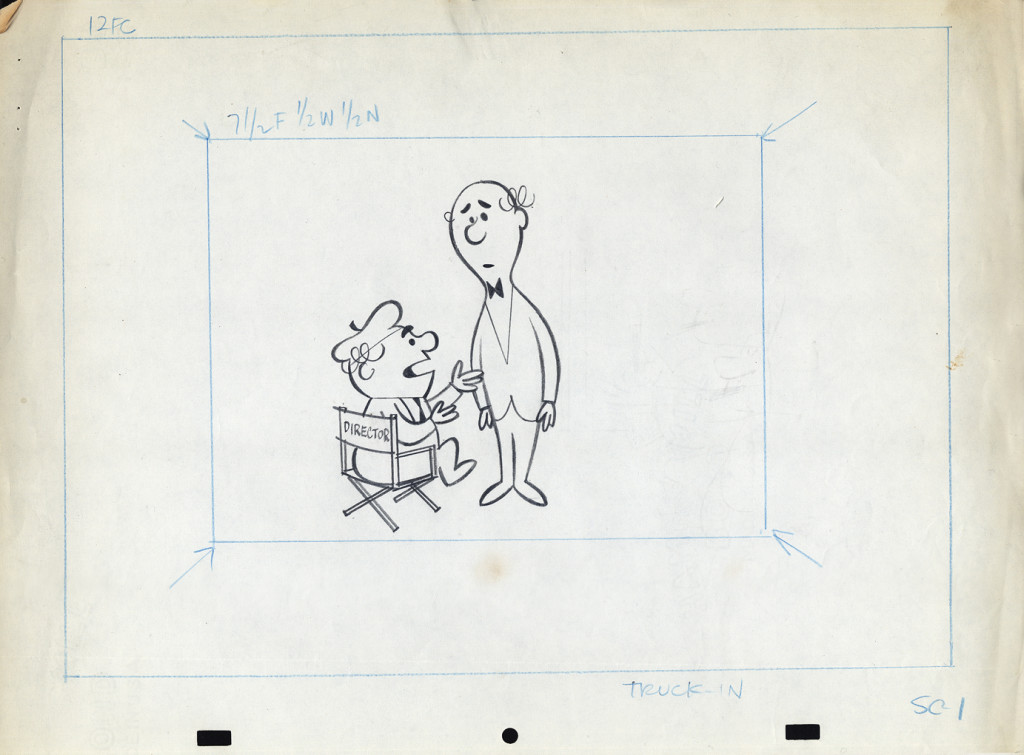

Among Vince Cafarelli‘s remaining artifacts there are lots of bits and pieces from several Piels Bros. commercial spots. I decided to put some of it together – even though they’re not really connected – into this one post.

There are animation drawings I’ll try to post in other pieces.

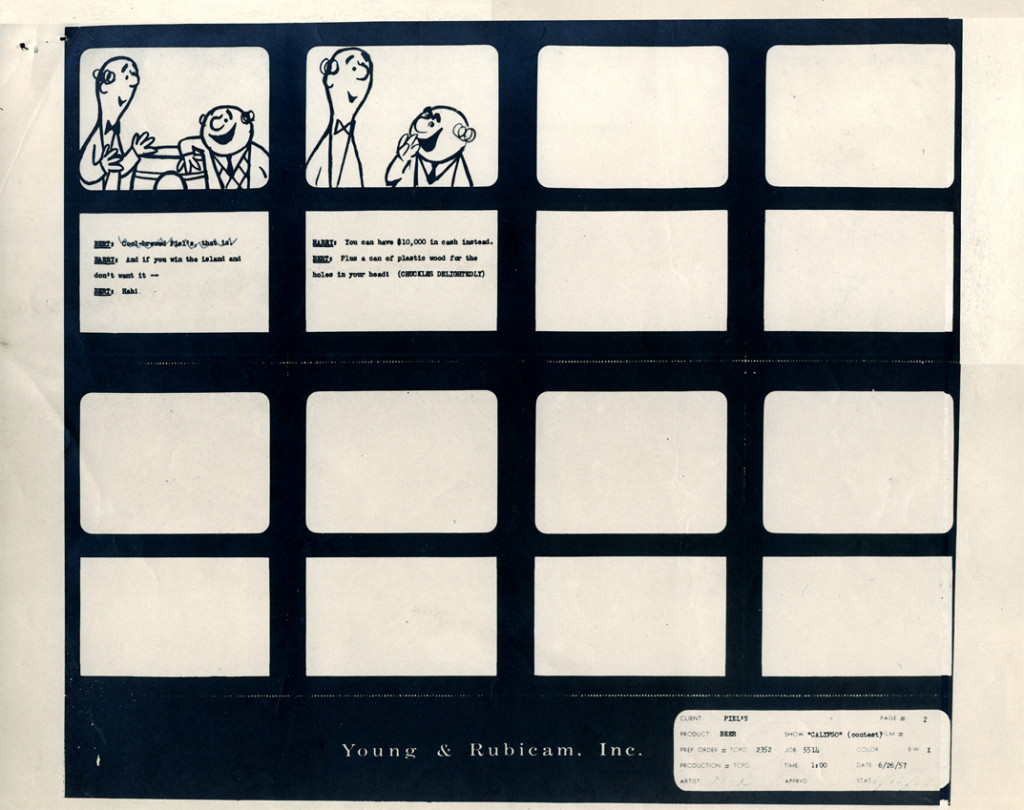

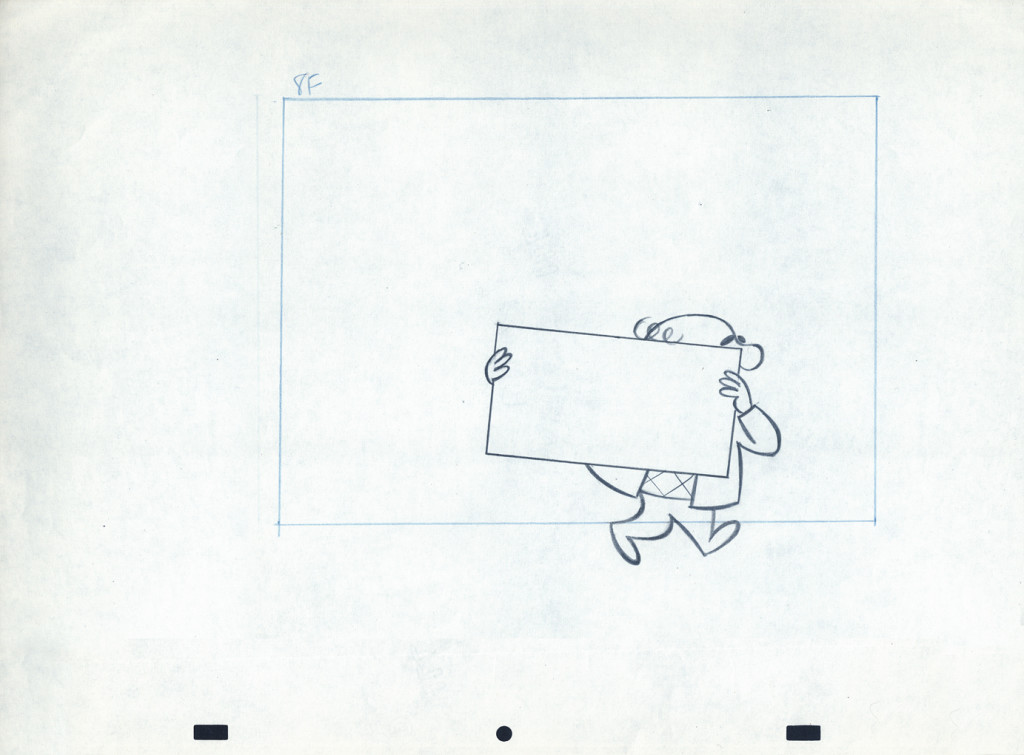

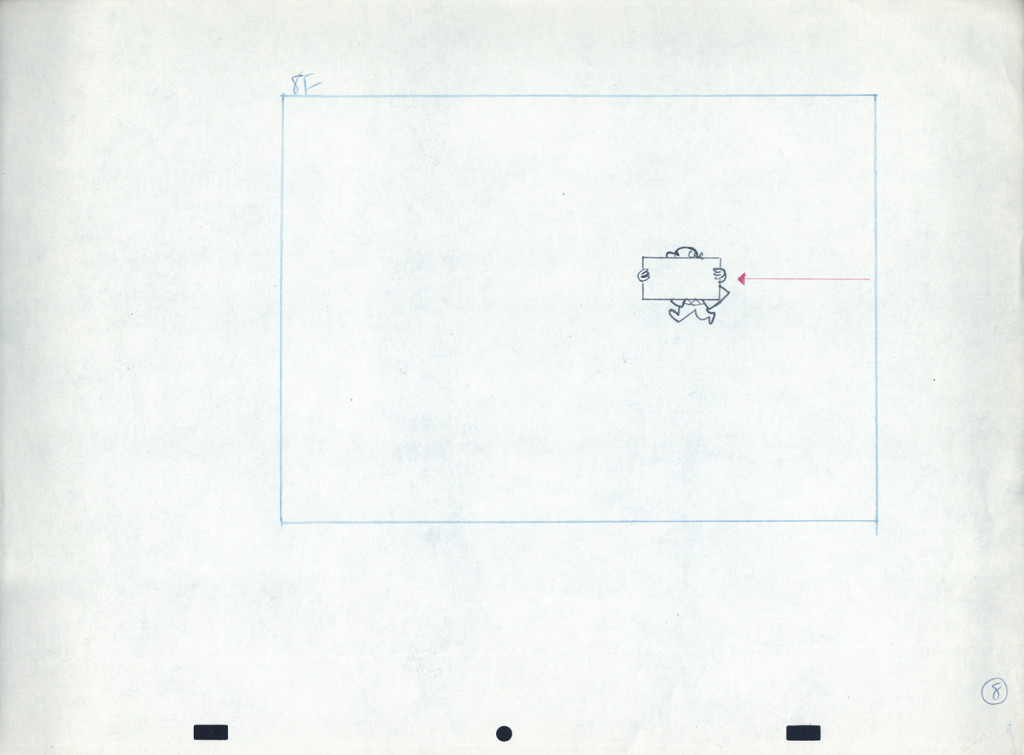

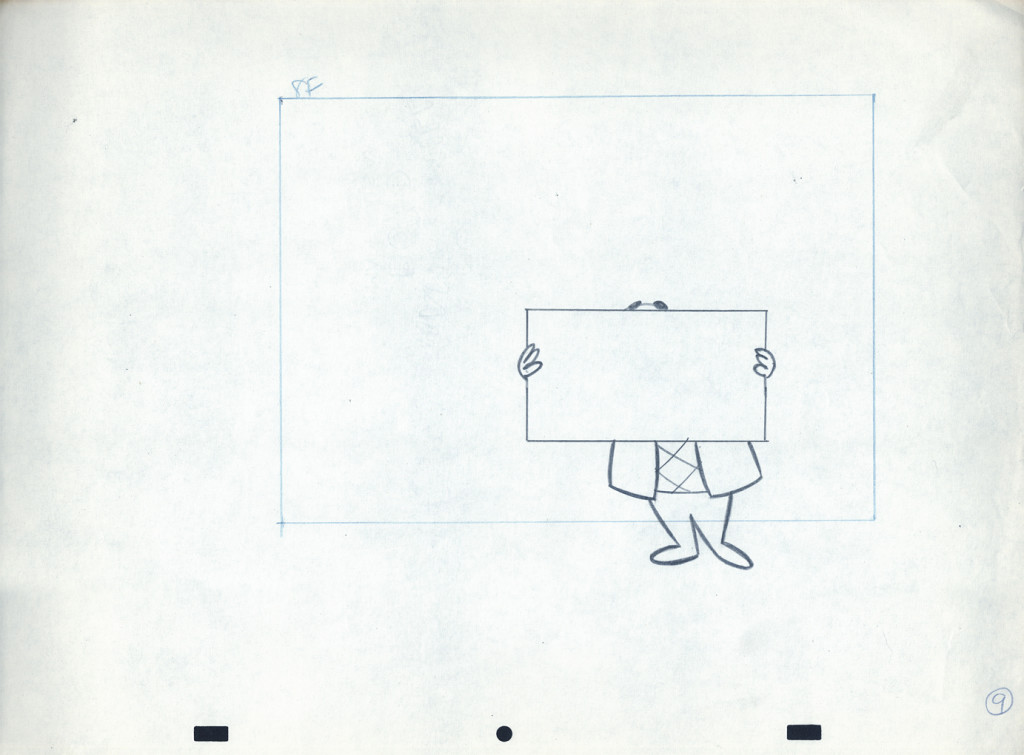

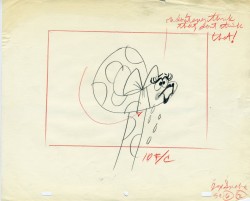

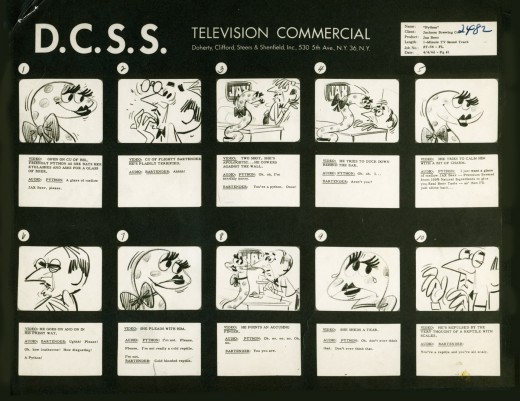

Here, we have a storyboard for a spot; I believe this is an abbreviated spot promoting some contest Piels beer was running. I think this is from a shortened version of a one minute spot since there are animation drawings which are obviously from the same setup, but they’re not part of this storyboard. (There’s an unveiling of the barrel, which is upside down.)

Since the boards are dated 1957, and given the use of signal corps pegs, I believe these were done for UPA.

Regardless, the drawings are excellent. I presume they’re hand outs to Lu Guarnier, animating, and Vince Cafarelli, assisting.

1

1

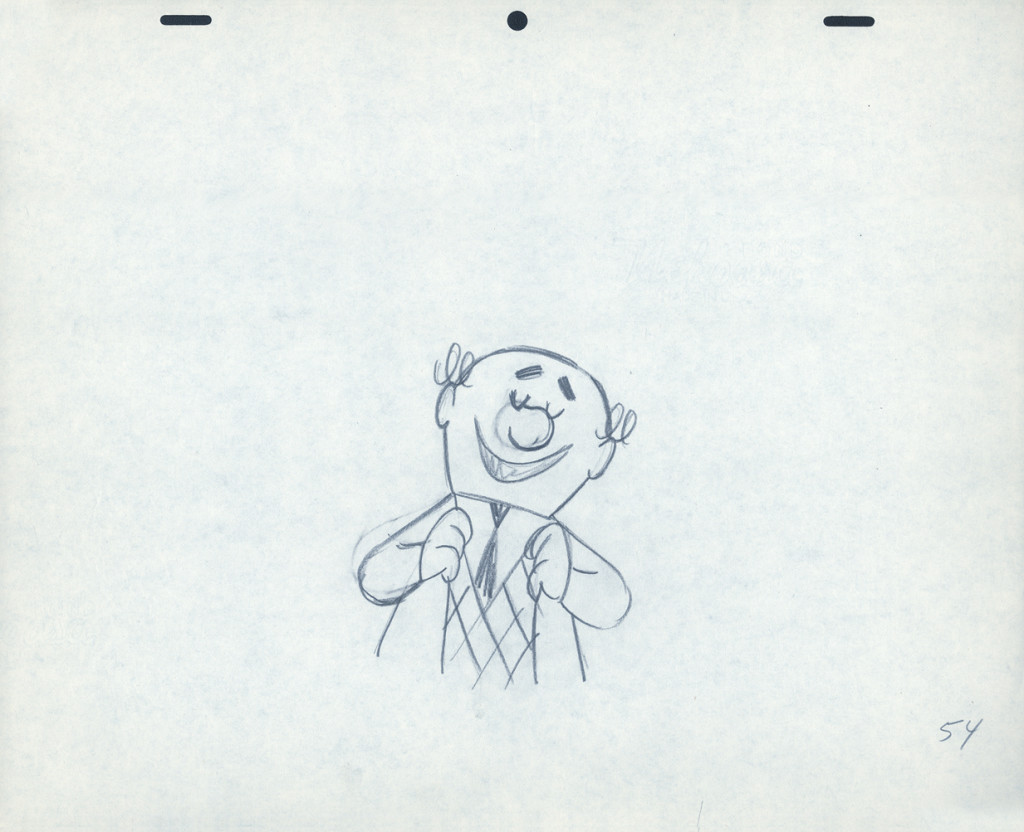

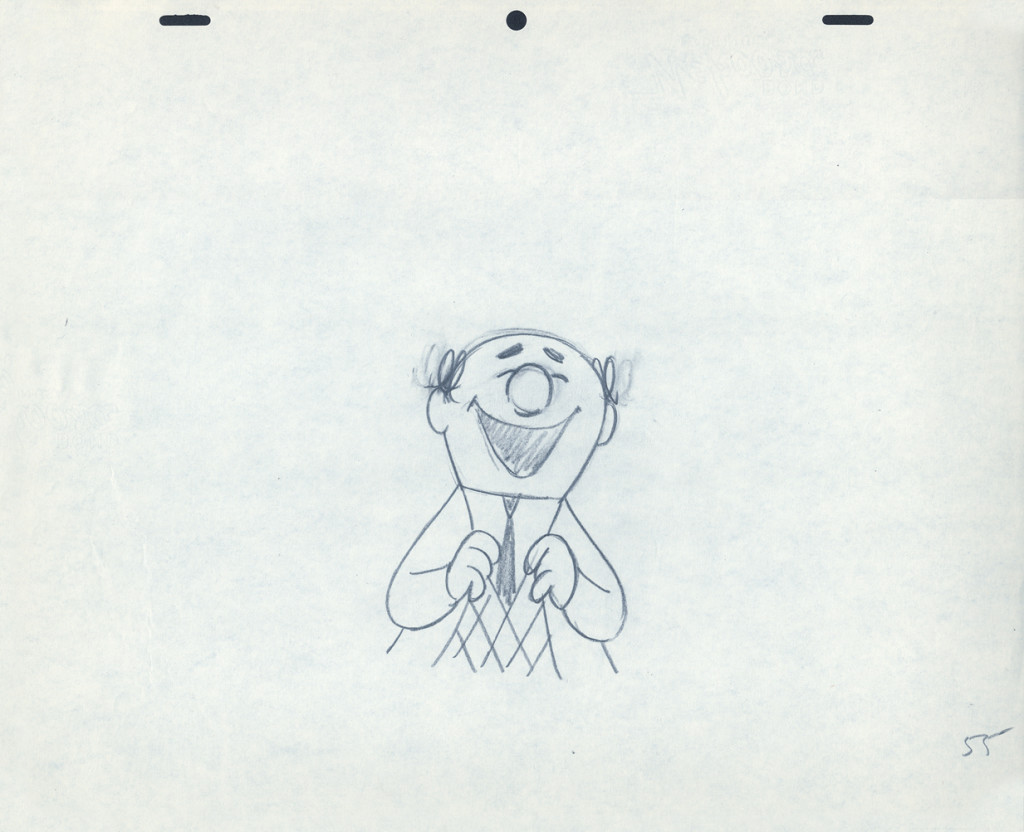

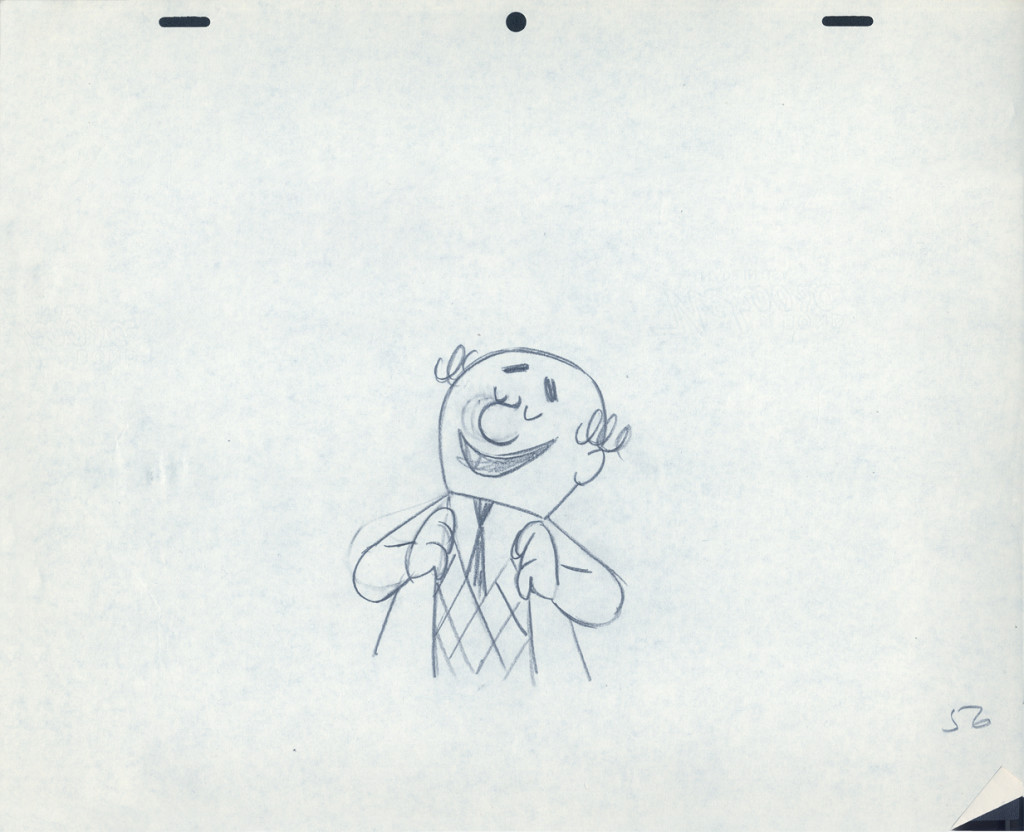

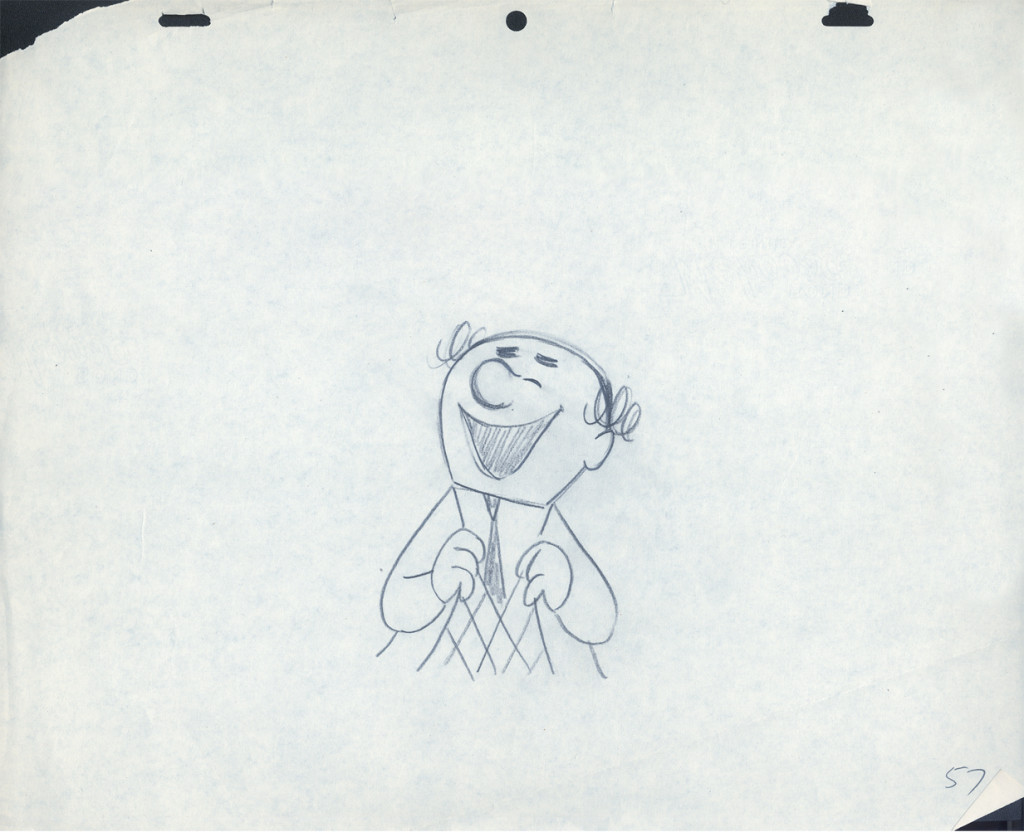

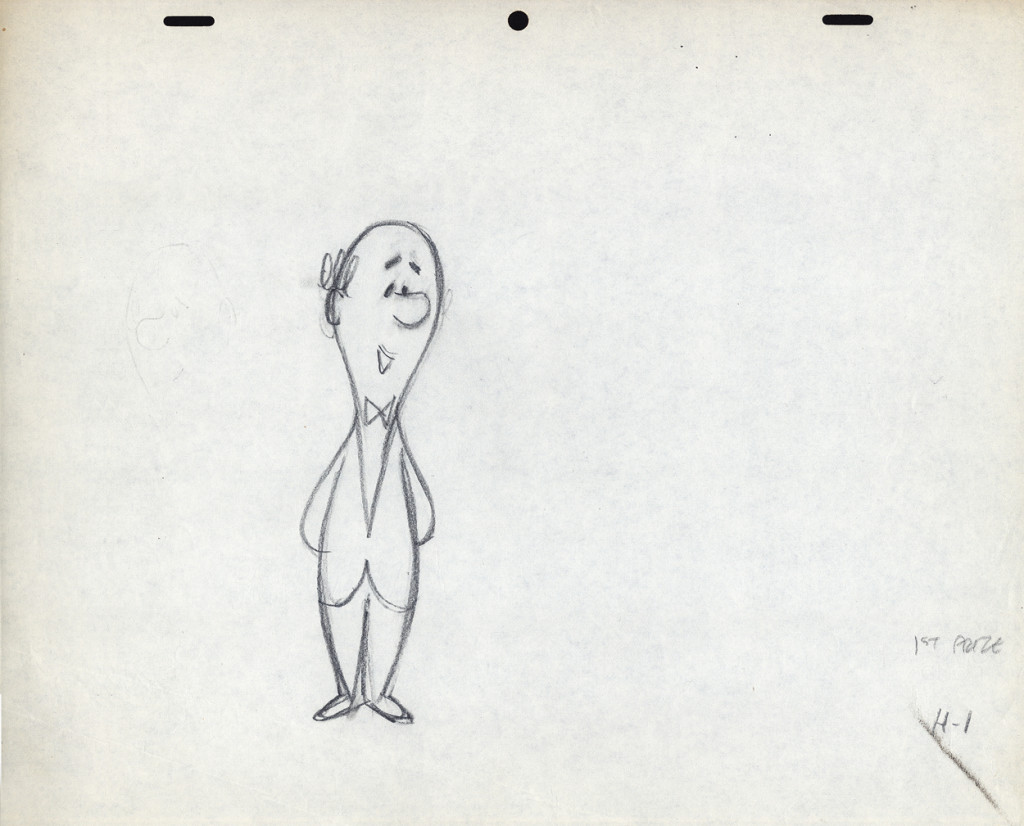

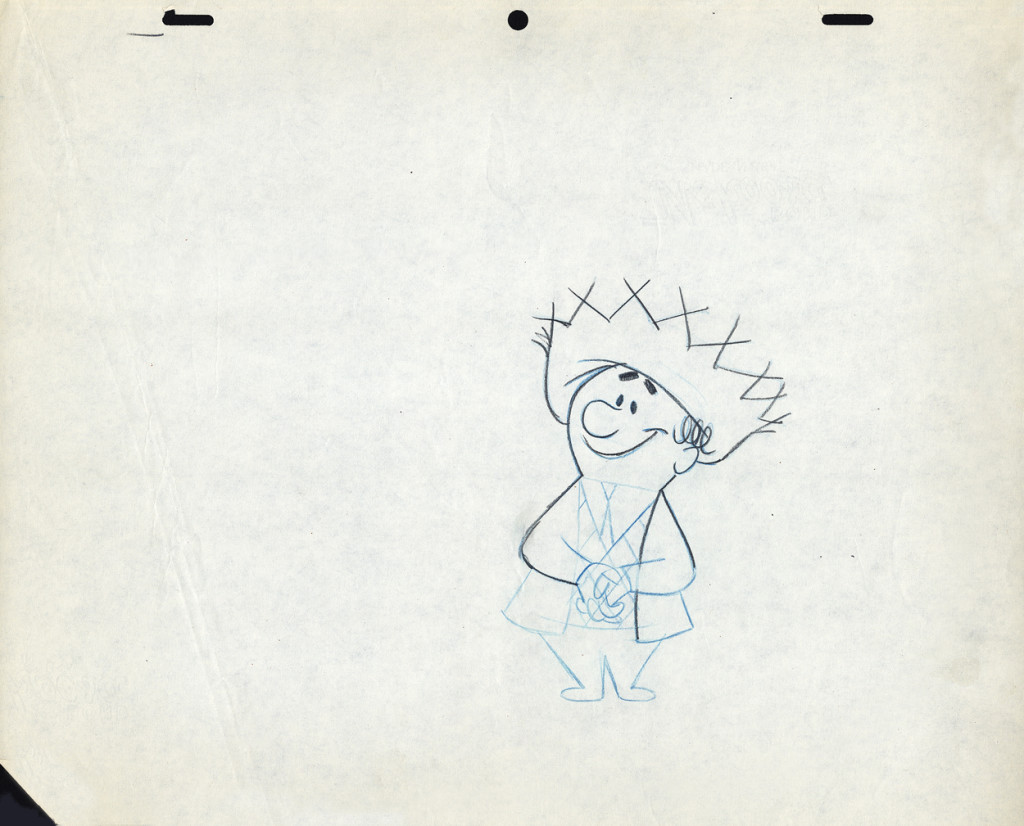

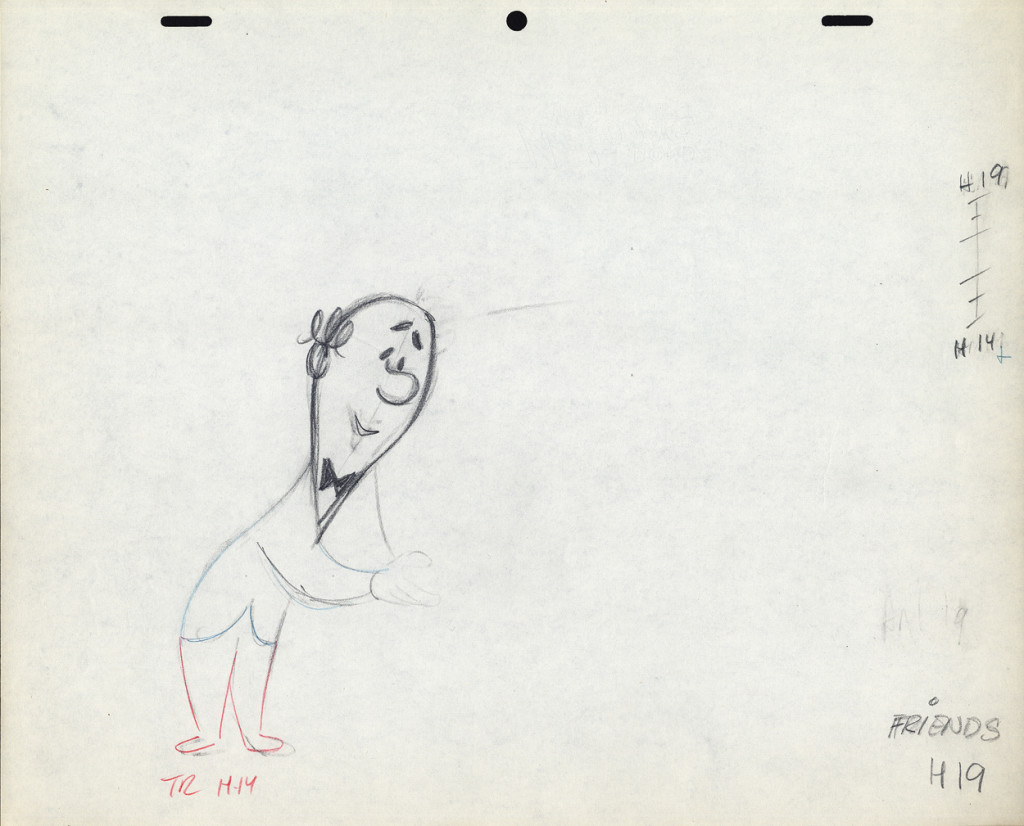

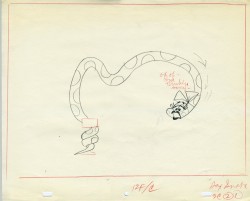

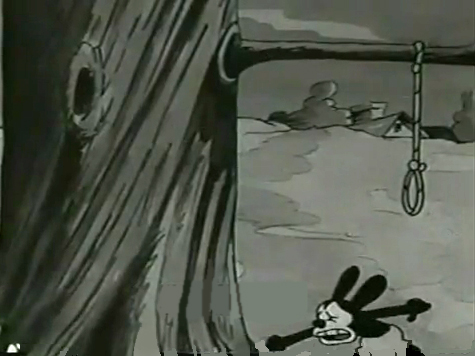

The following are three drawings from the opening scene of this storyboard. Others from this scene weren’t saved.

1

1Here’s Bert.

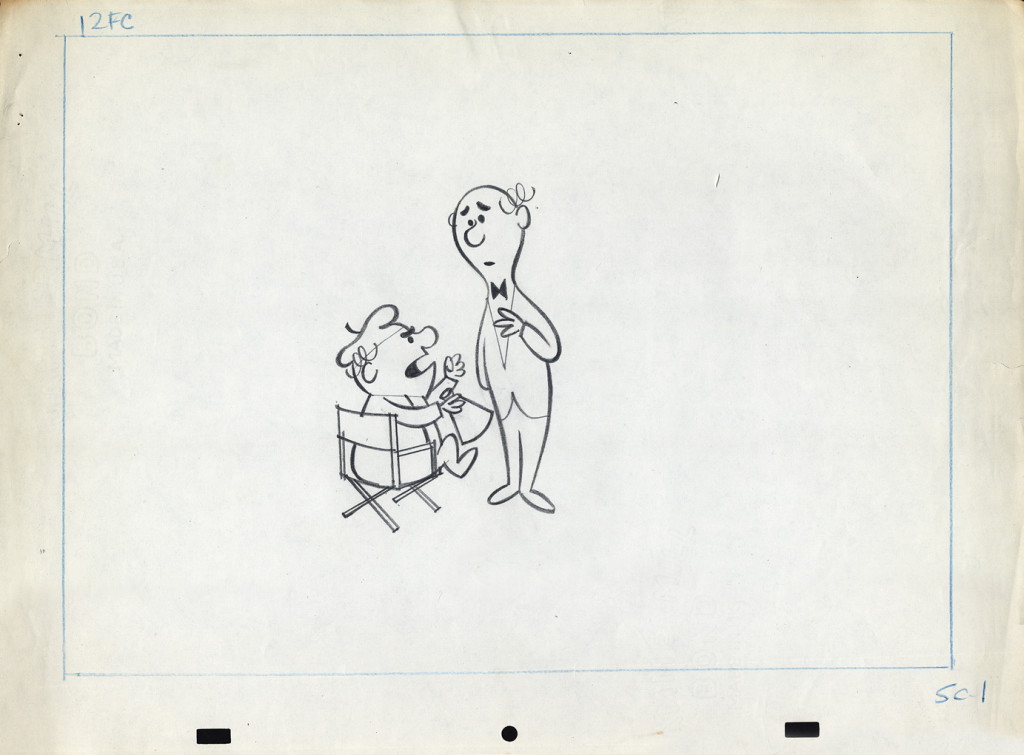

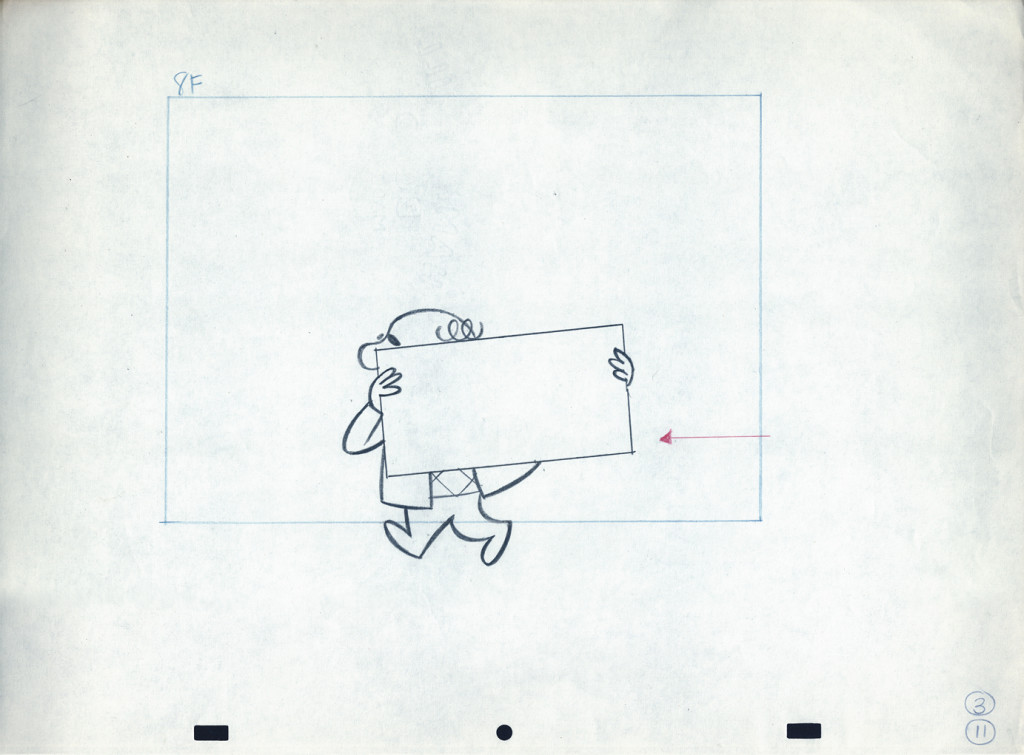

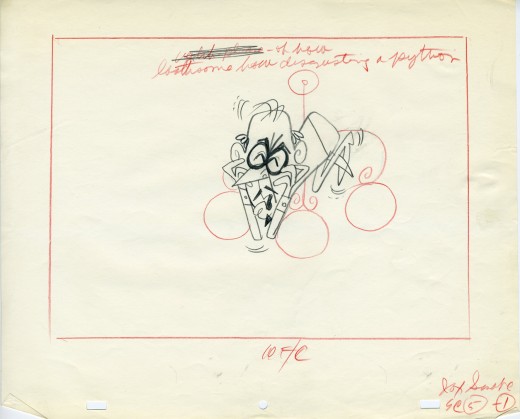

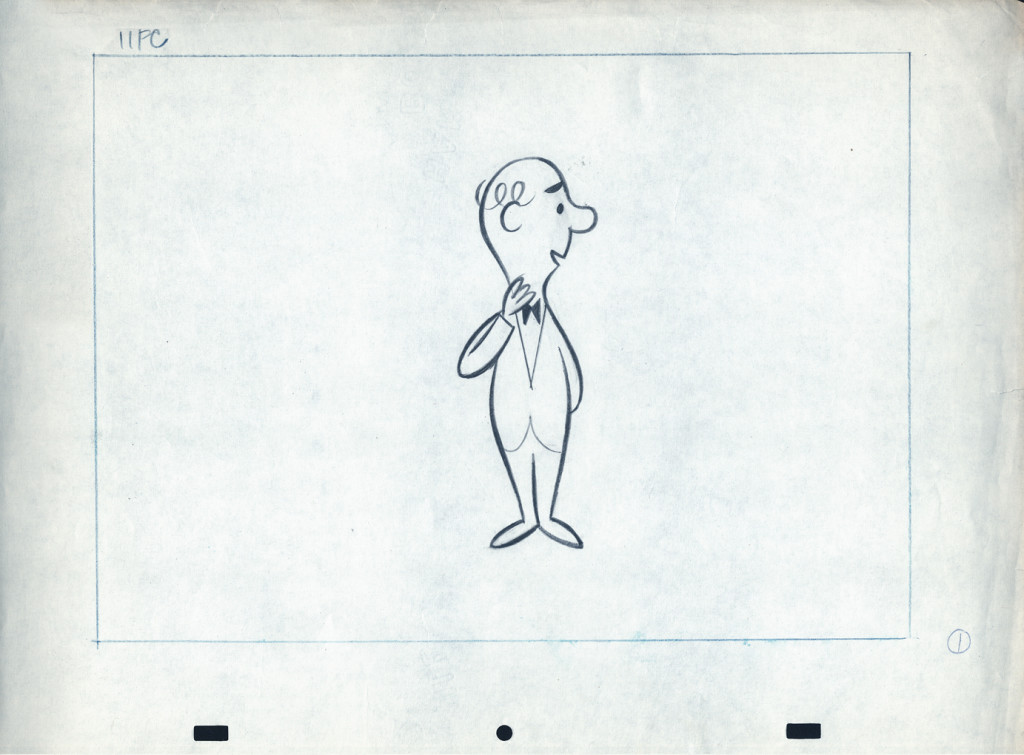

Let’s follow that with layout drawings from two different spots. The first doesn’t really offer much, but the quality of the clean-ups and the drawing is first rate. I’m pleased to post it:

1a

1a

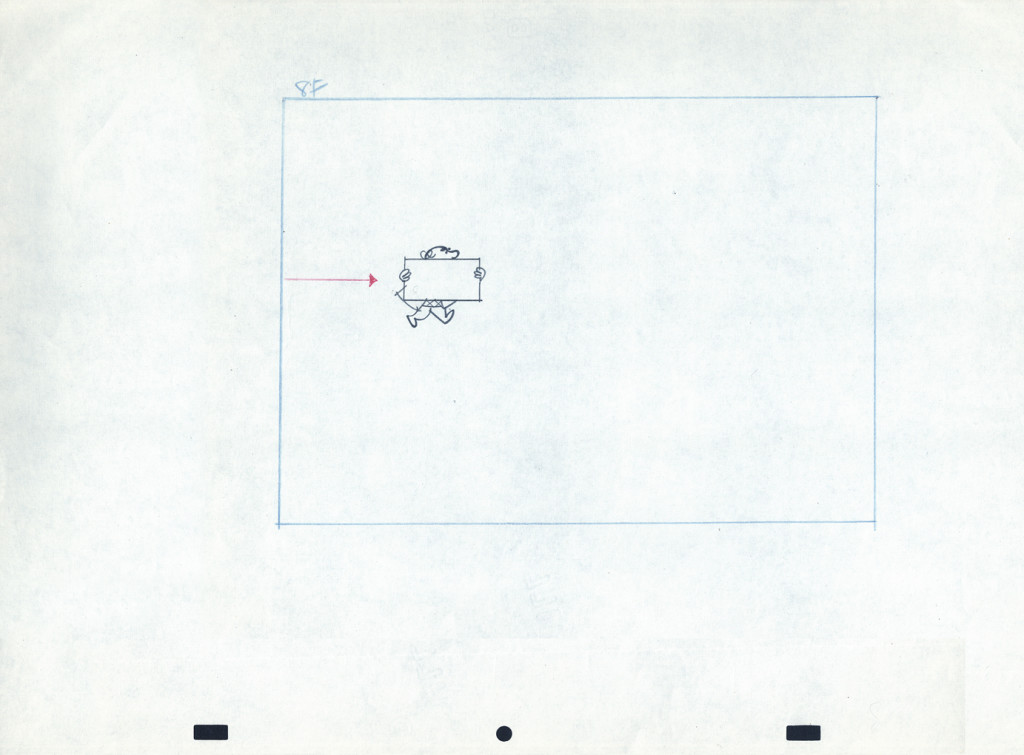

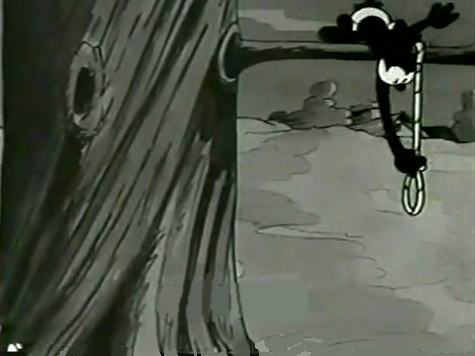

Here are layout drawings for the second of the two spots I have in hand. I presume this is also a spot promoting that contest.

1

1

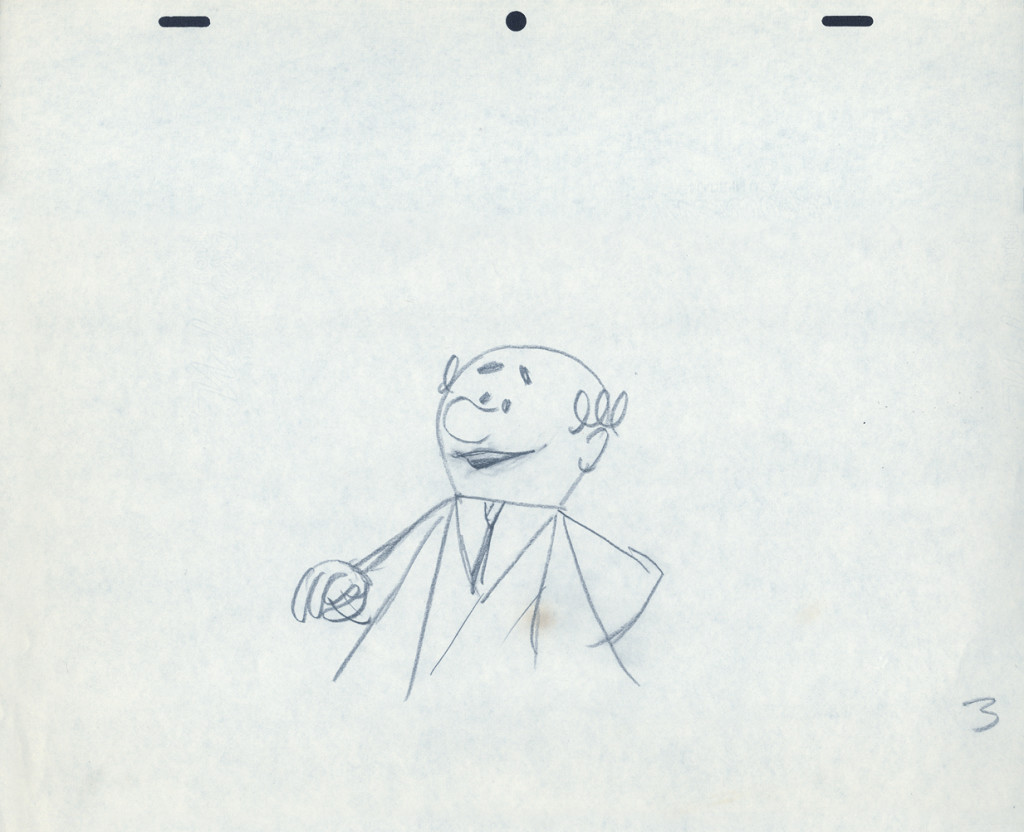

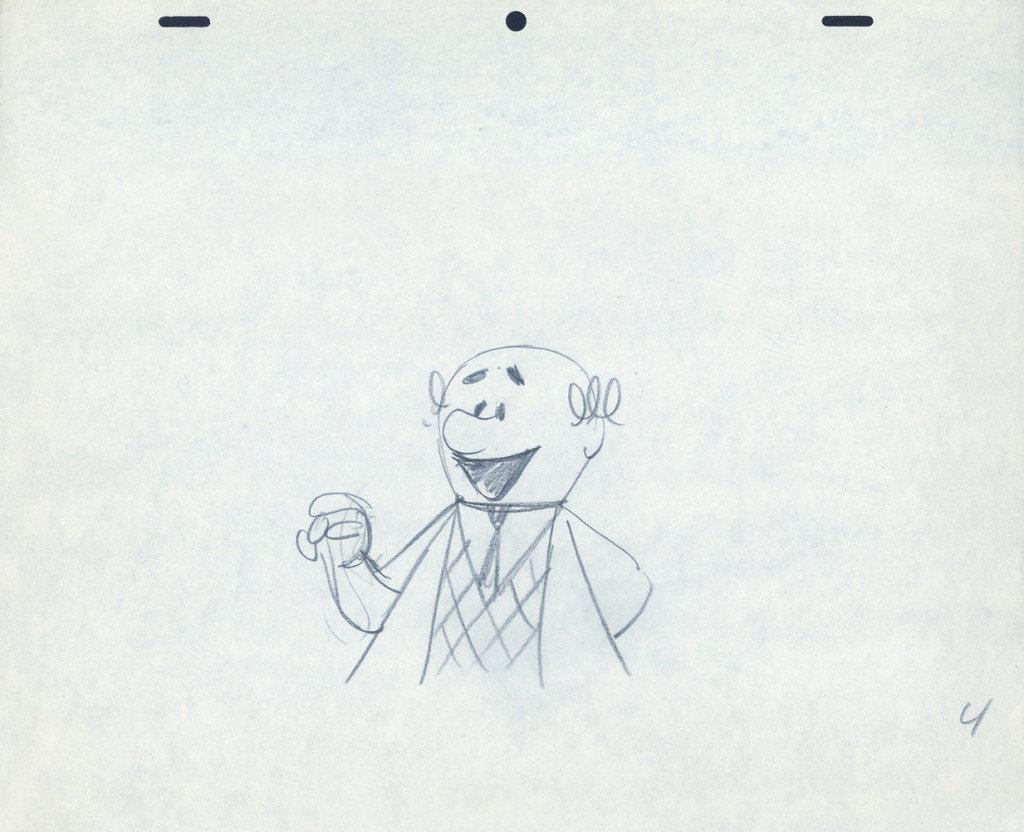

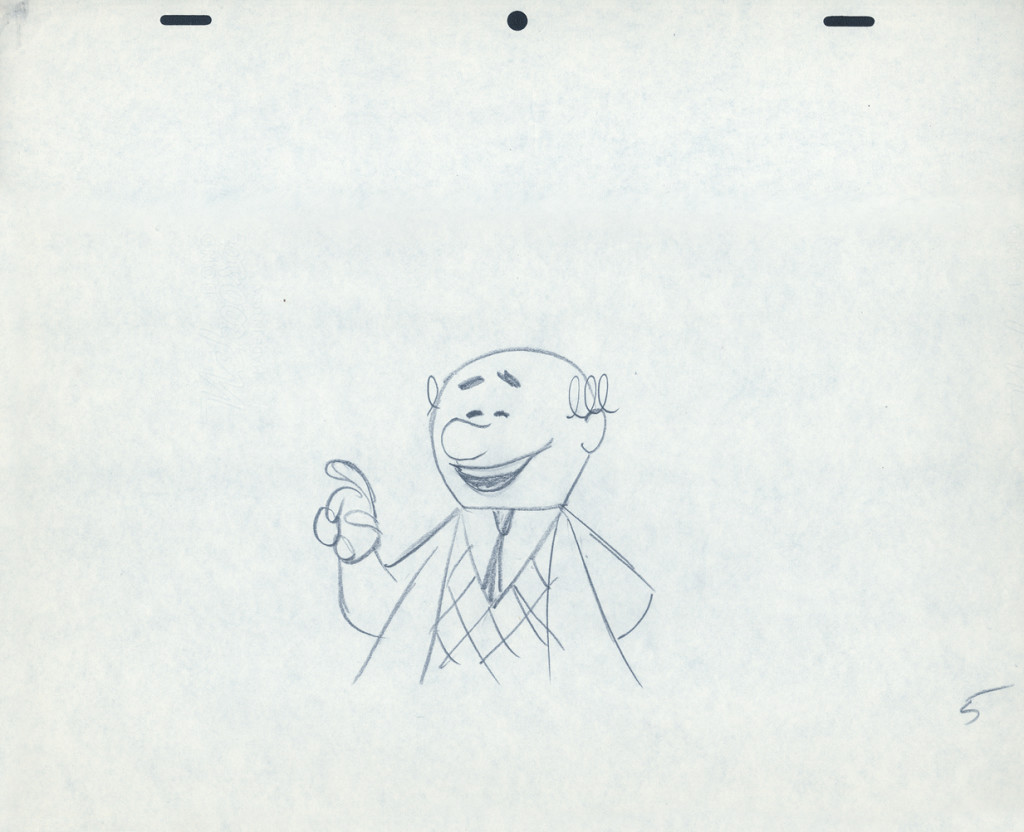

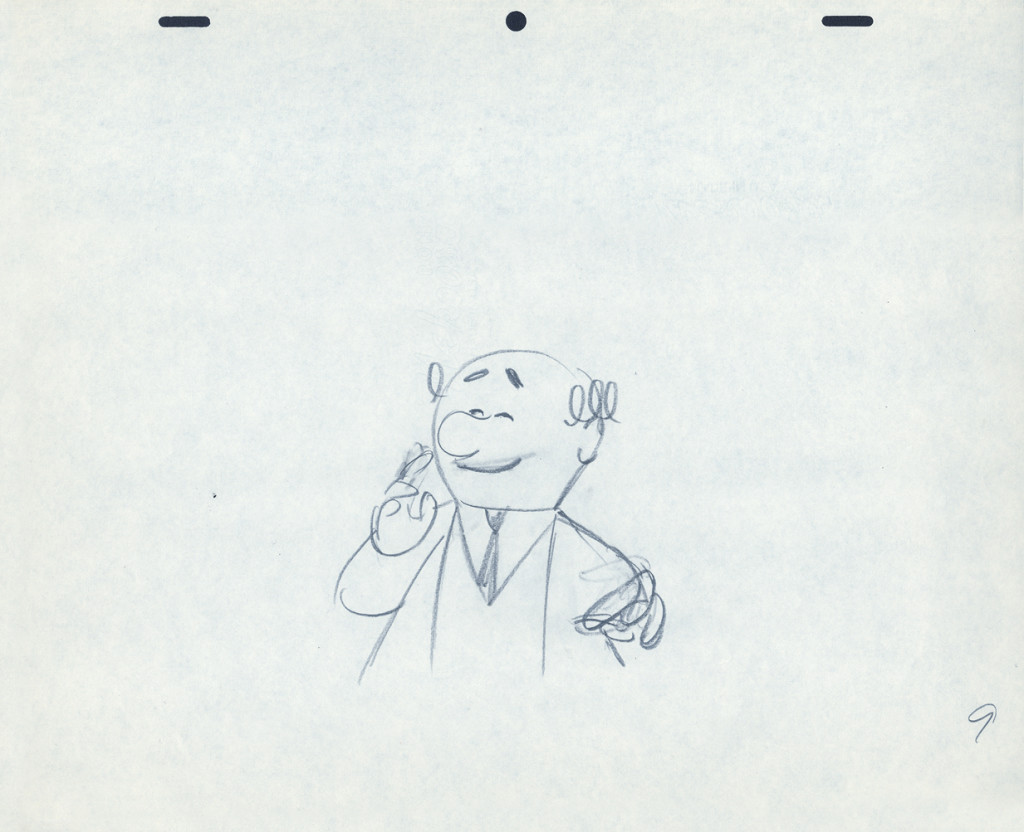

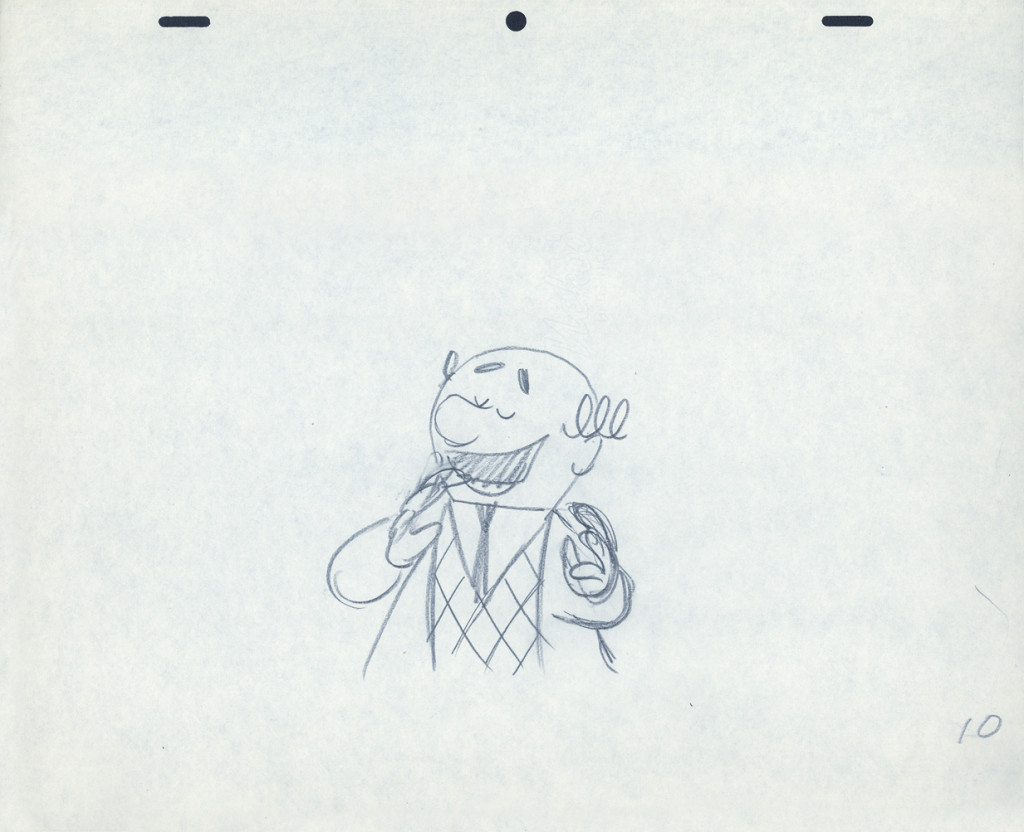

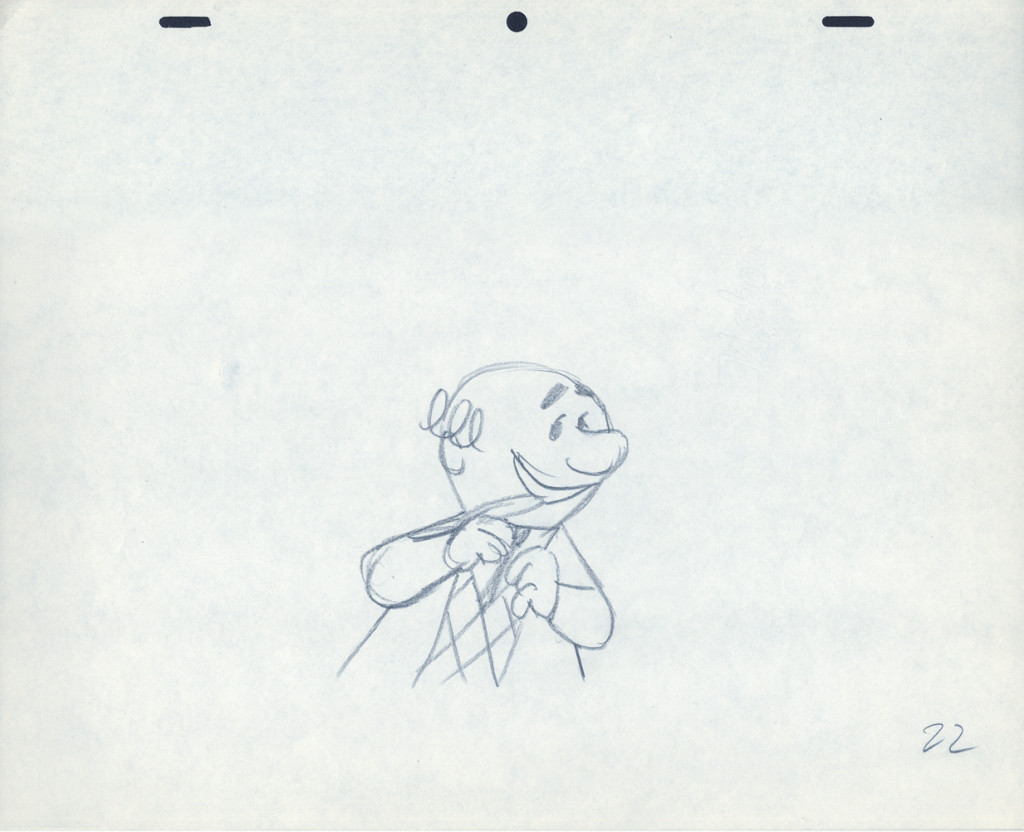

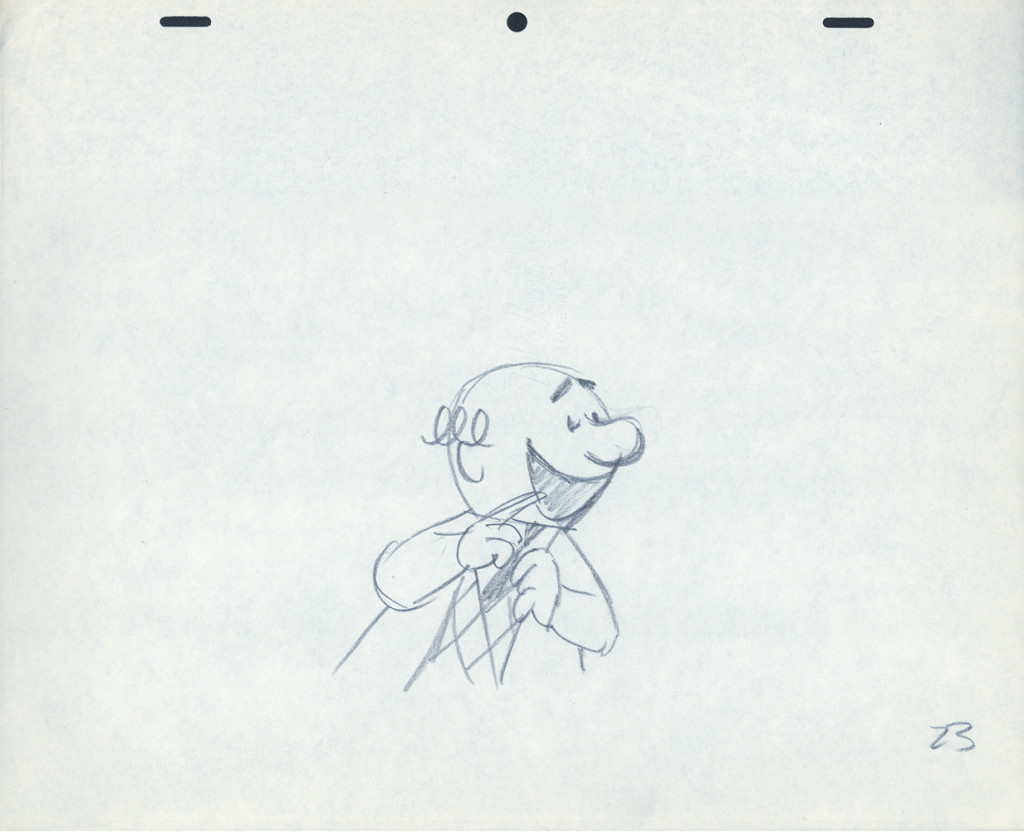

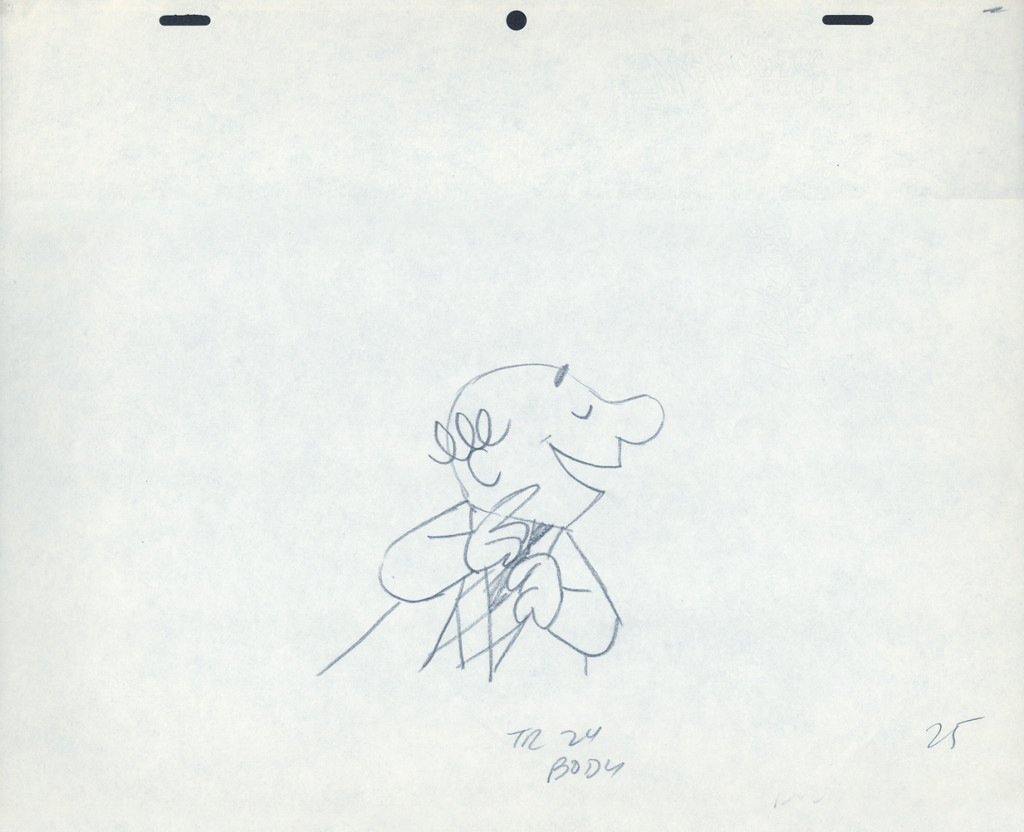

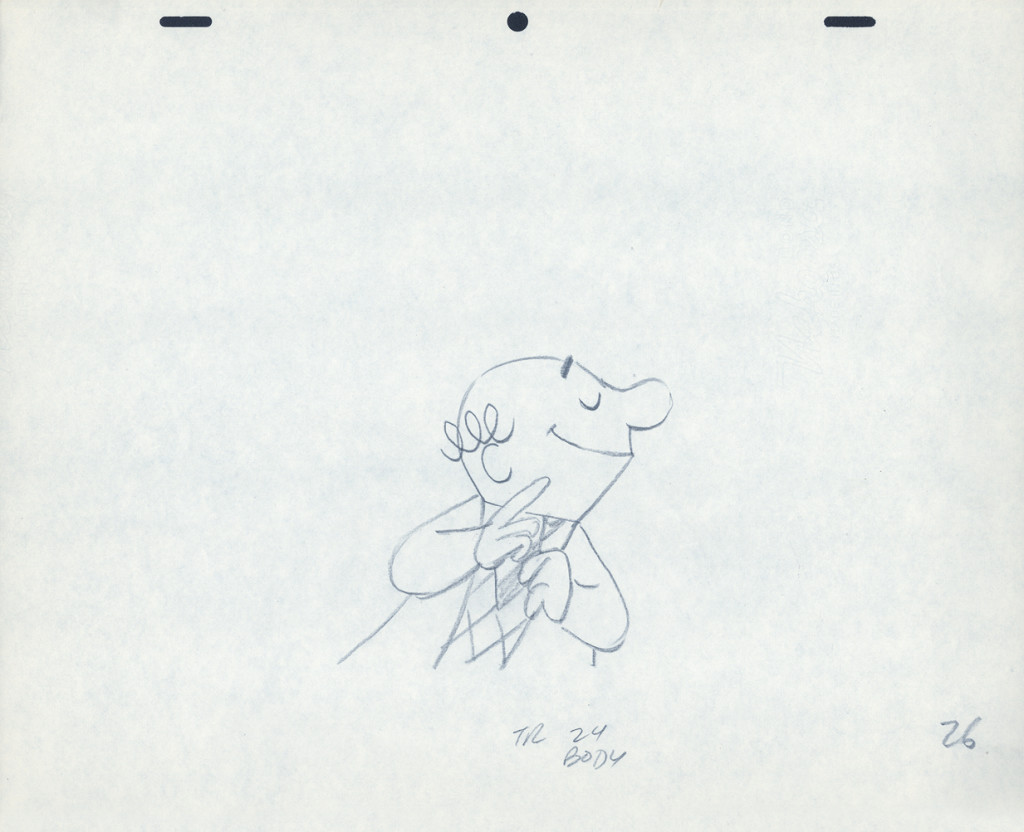

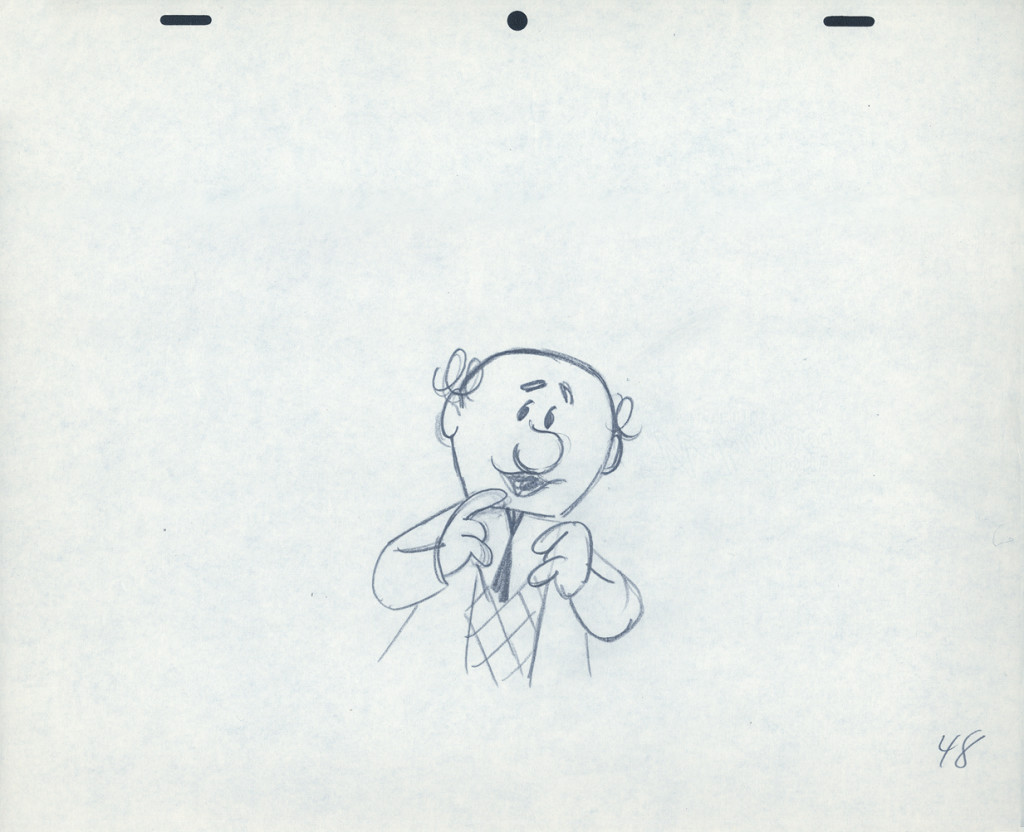

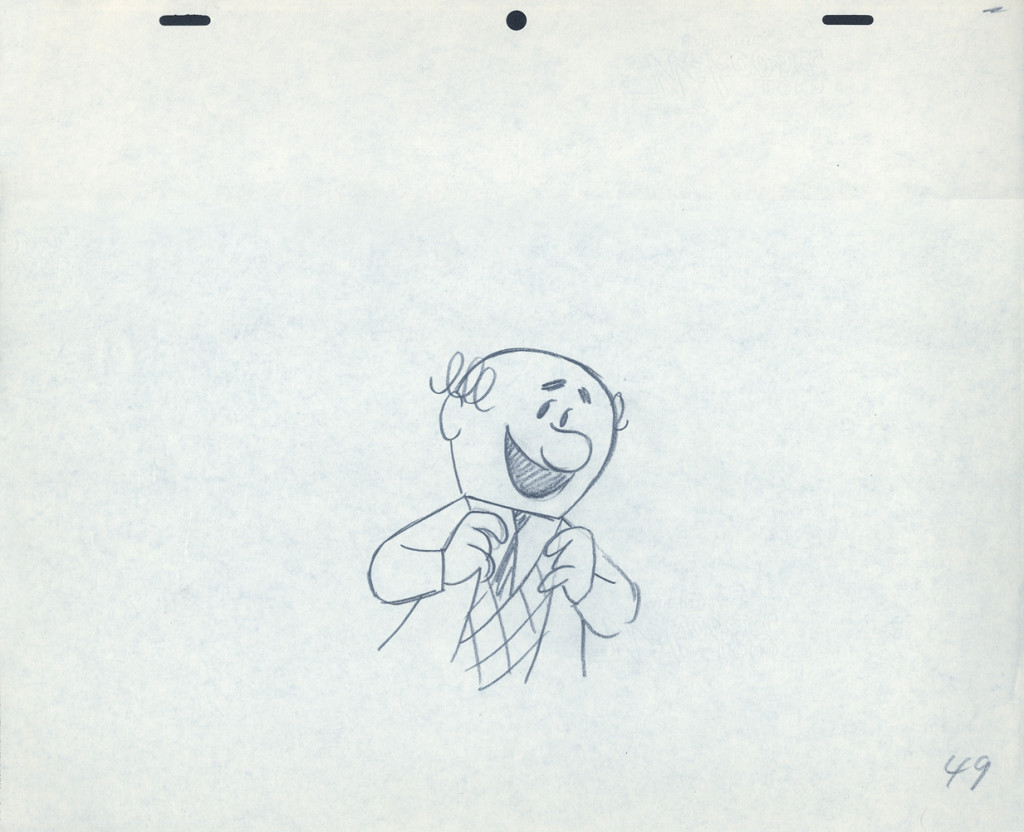

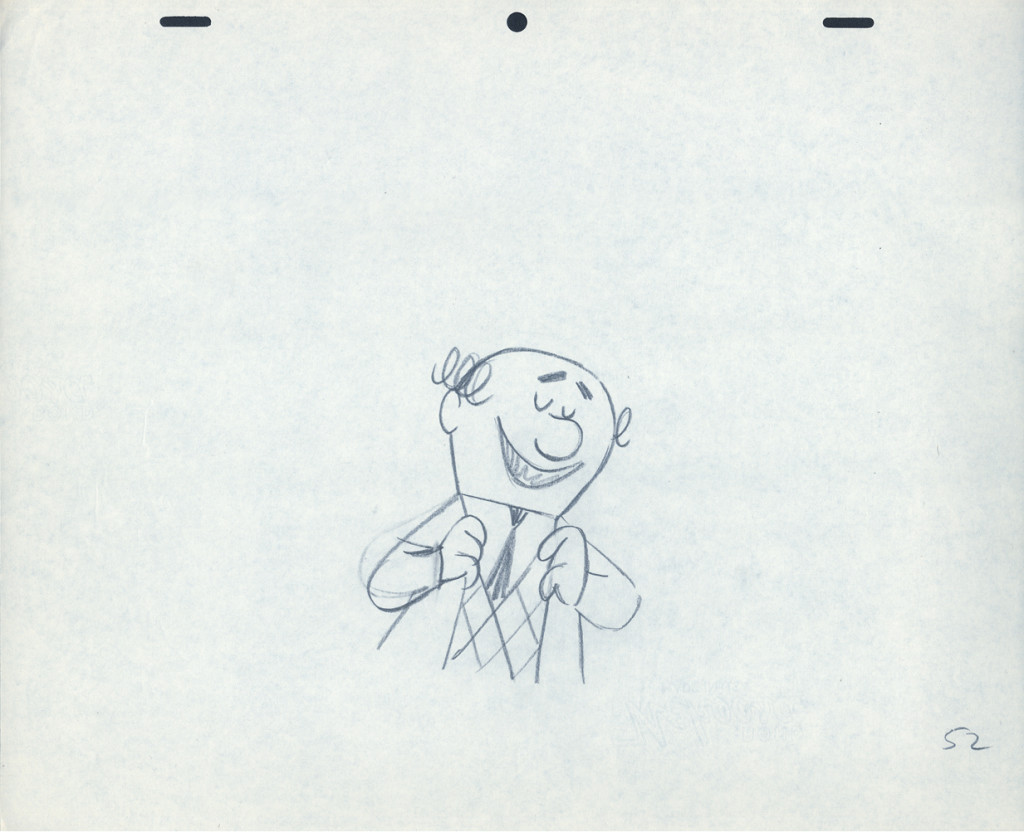

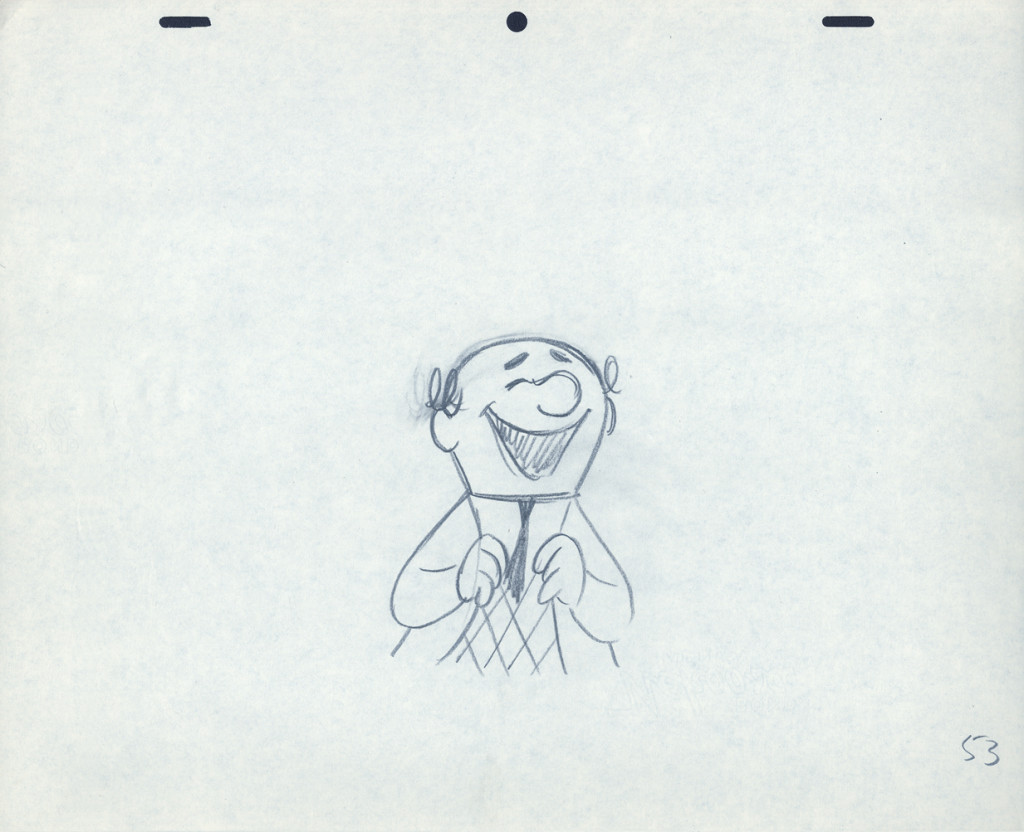

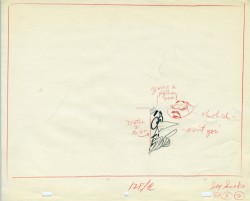

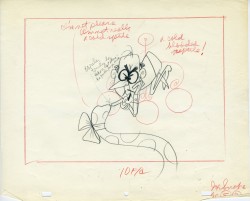

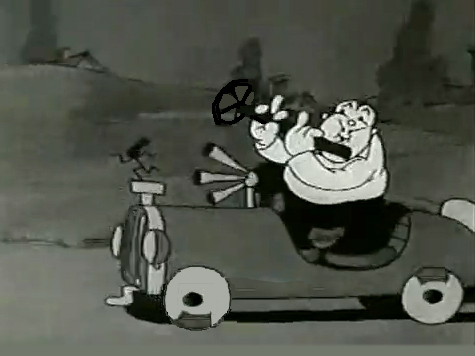

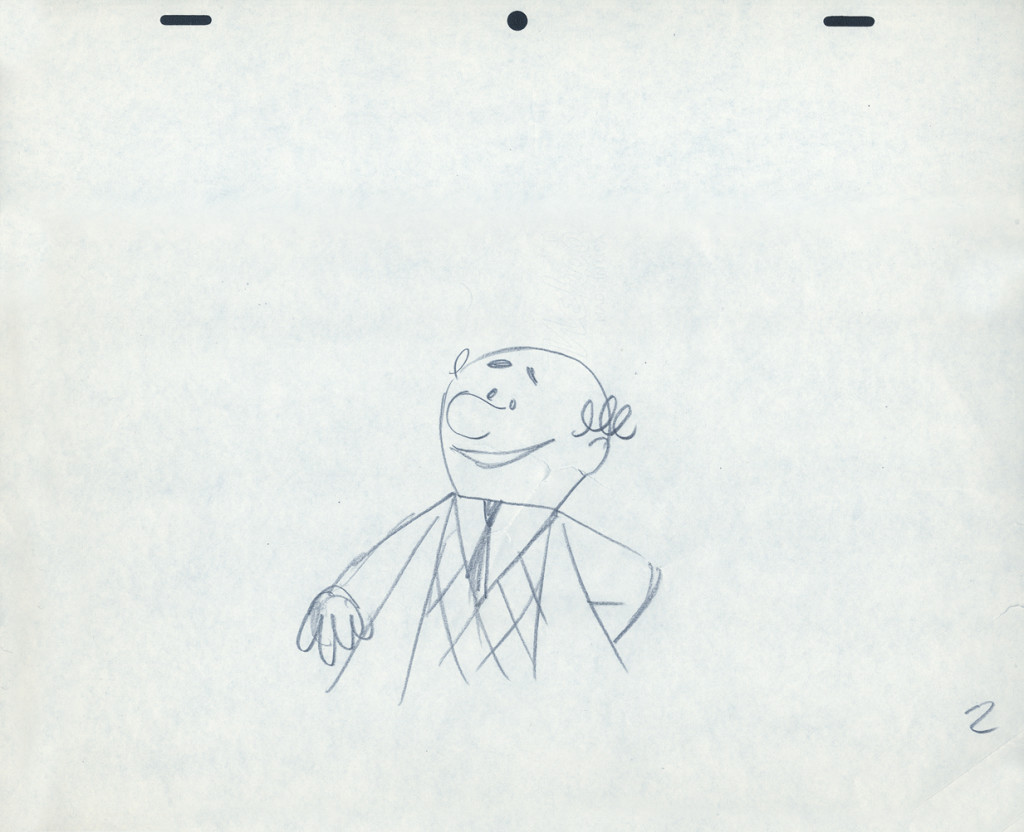

- Here’s one of the scenes saved by Vince Cafarelli from a commercial he did while at Goulding-Elliott-Graham. The commercial was animated by Lu Guarnier, and Vinny was the assistant on it. Hence, he saved the rough drawings (instead of Bert Piels. (Sorry I don’t know what he’s saying, though I’m looking for the storyboard.)

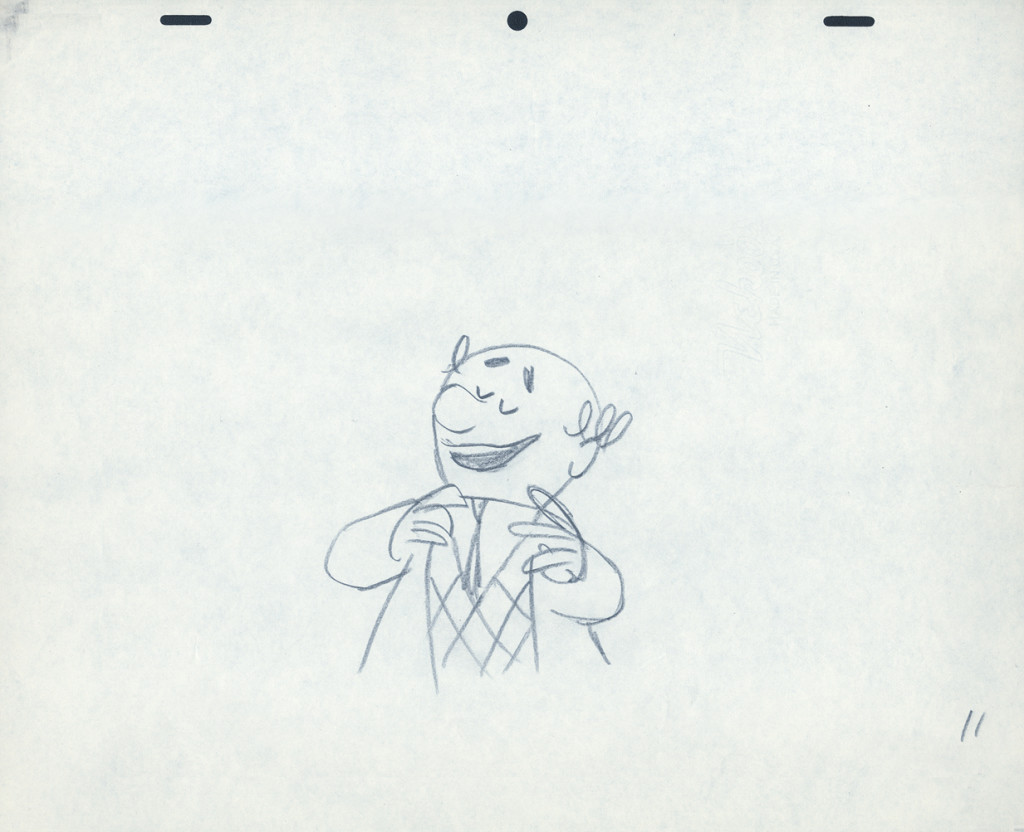

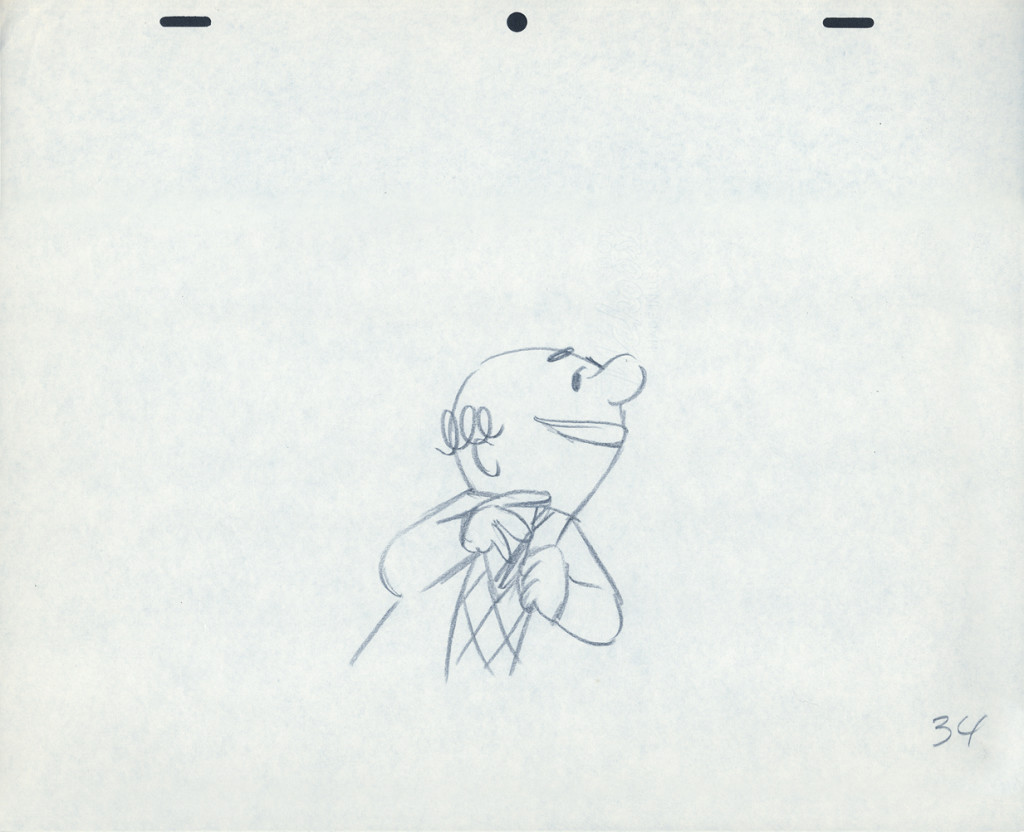

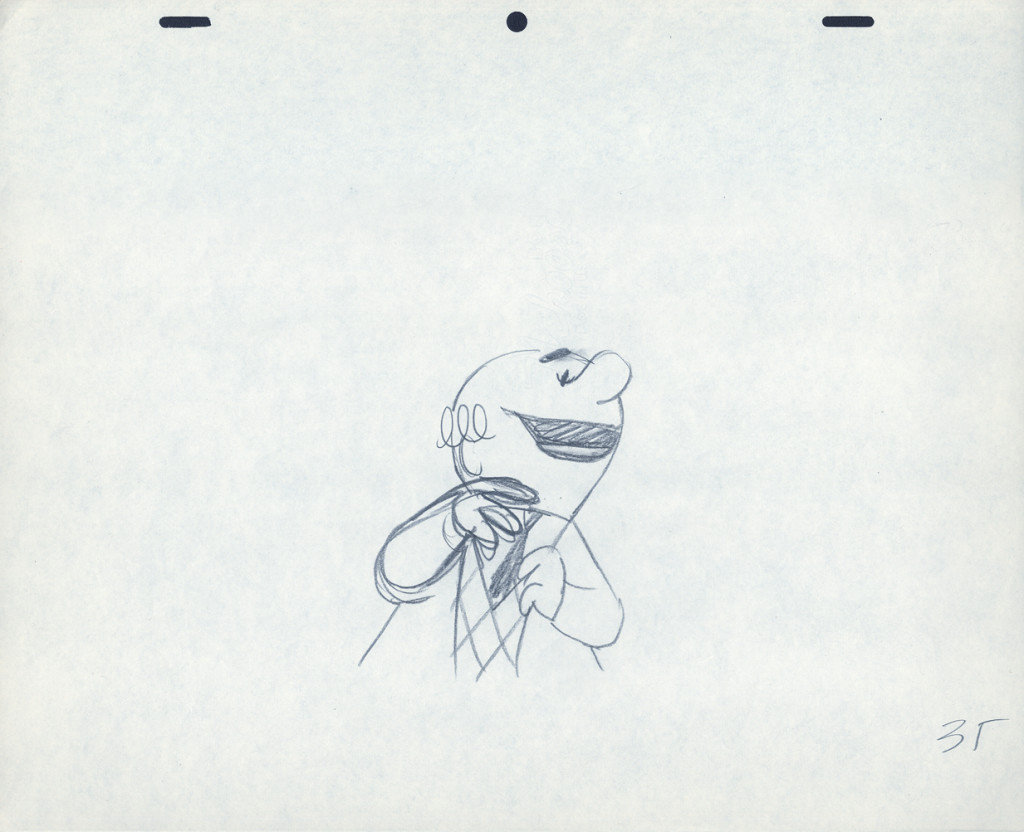

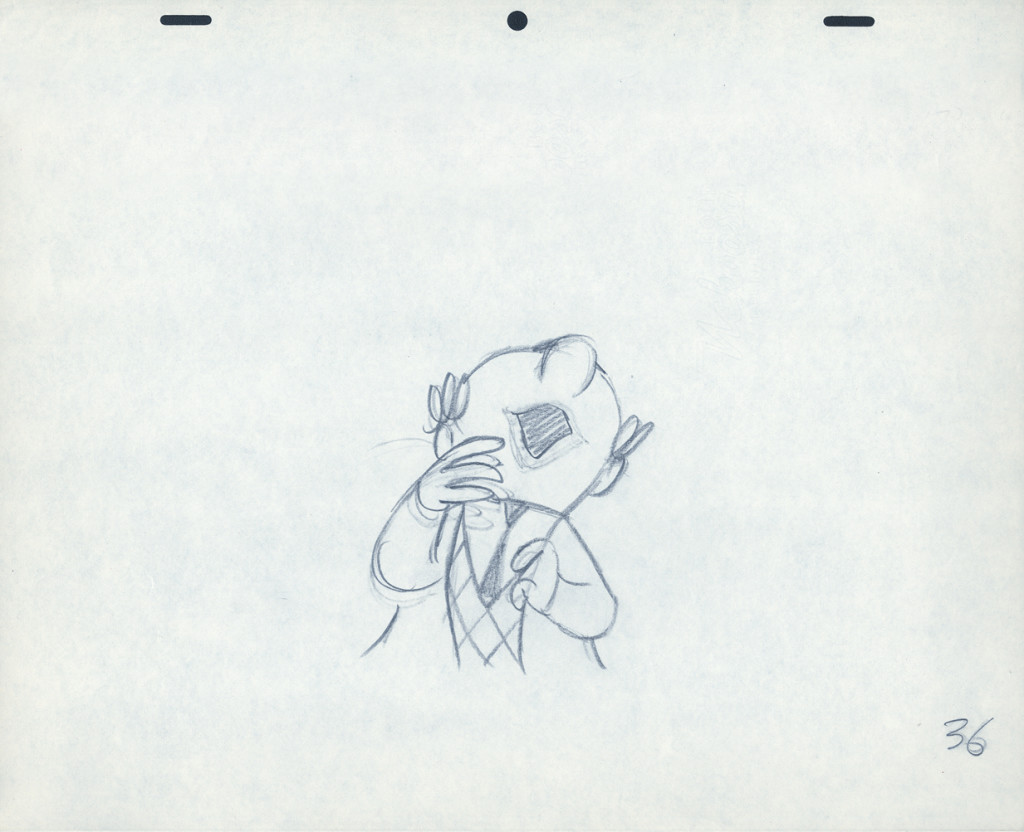

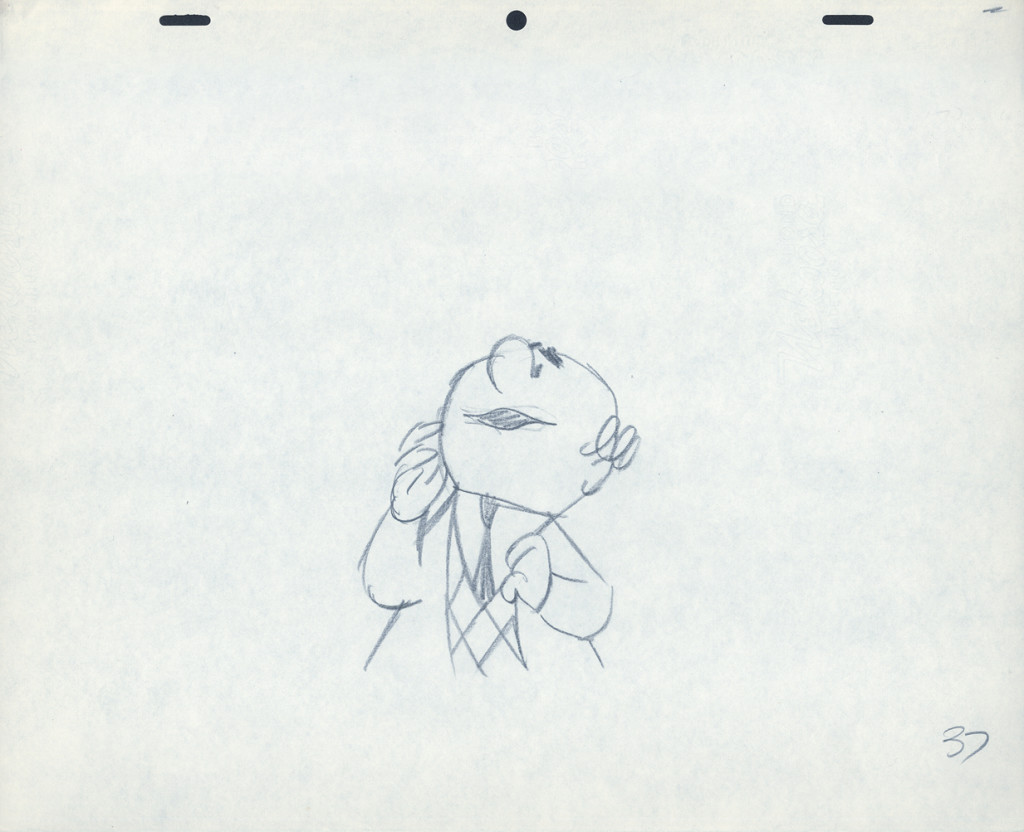

So, here are Lu’s rough drawings in this CU

2

2

The following QT movie was made by exposing all drawings on twos

except for the extreme positions that were missing inbetweens.

For those, I dissolved from one extreme to the next.

It drove me crazy that Lu Guarnier always animated on top pegs.

Next week with the last of these three posts on this Piels Bros commercial, I’ll talk about Lu’s animation and some of my pet peeves.

Here’s the last of the three posts I’ve been able to cull from the drawings left behind in Vince Cafarelli‘s things. The 60 second spot was animated by Lu Guarnier and clean-up and assisting was by Vinnie.

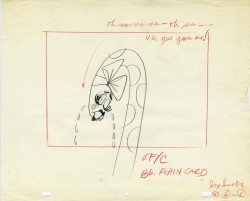

Within this post there are drawings from two separate scenes. If you look at the storyboard (I’d posted the entire board in another post, but I’ve pulled the particular frames from the board to show again here), you can see what it is the characters are saying. I don’t have all the drawings for these two scenes; just those I’ve posted.

I’m also going to use these drawings of Lu’s to write about his style of animation. I was taught from the start that this was completely done in an incorrect way. I don’t mean to say something negative about a good animator, but it is a lesson that should be learned for those who are going through the journeyman system of animation.

Right from the get-go I had some difficulty assisting Lu’s scenes. He started in the old days (early-mid Thirties) at Warner Bros, in Clampett’s unit, and moved from there to the Signal Corps (Army); then to New York working at a few studios before landing at UPA’s commercial studio. After that, he free lanced most of his career, as had so many of the other New York animators. They’d work for six months to a year at one studio then would move on to another.

Right from the get-go I had some difficulty assisting Lu’s scenes. He started in the old days (early-mid Thirties) at Warner Bros, in Clampett’s unit, and moved from there to the Signal Corps (Army); then to New York working at a few studios before landing at UPA’s commercial studio. After that, he free lanced most of his career, as had so many of the other New York animators. They’d work for six months to a year at one studio then would move on to another.

I suspect the problems in Lu’s animation all generated from the training he’d gotten at WB. Lu worked in a very rough style. No problem there. An animator should work rough. These drawings posted aren’t particularly rough, but in his later years (when I knew him) there was hardly a line you could aim for in doing the clean-up. His style was done in small sketchy dashes that molded the character. Rarely was it on model, and always it was done with a dark, soft leaded pencil. There were others who worked rougher, Jack Schnerk was one, but Lu’s drawing was usually harder to clean up.

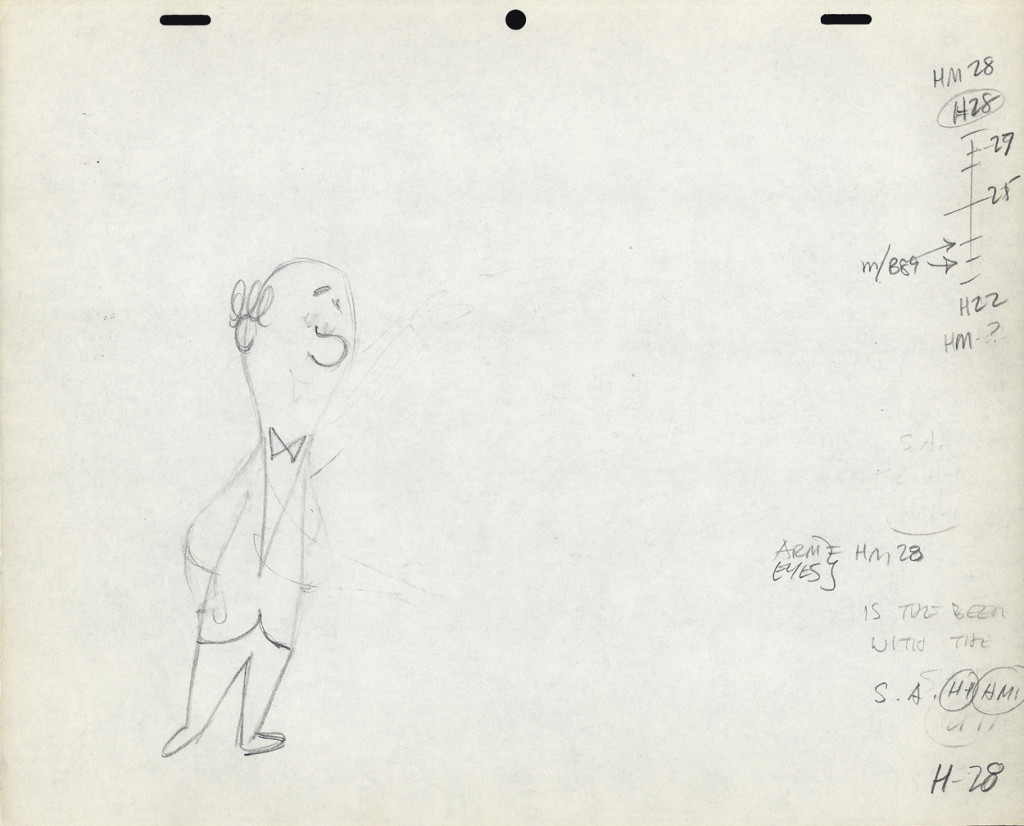

There was a rule that came out of the Disney studio, and, as both an animator and an assistant, I’ve followed it closely. When doing the breakdown charts (those ladders to the right of the drawing) all inbetween positions had to be exactly half way between drawing “A” and drawing “B”. If the animation called for it to be 1/4 of the way, you’d indicate that half-way mark then indicate your 1/4. If a drawing had to be closer or farther away – say 1/3 or 1/5th of the way – the animator should do it himself. This, as I learned it, was the law of the land. However, Lu would rarely adhere to it, and an assistant’s work became more complicated. The work was too easily hurt by a not-great inbetweener. I’ll point out an example of Lu’s breaking this rule as we come to it).

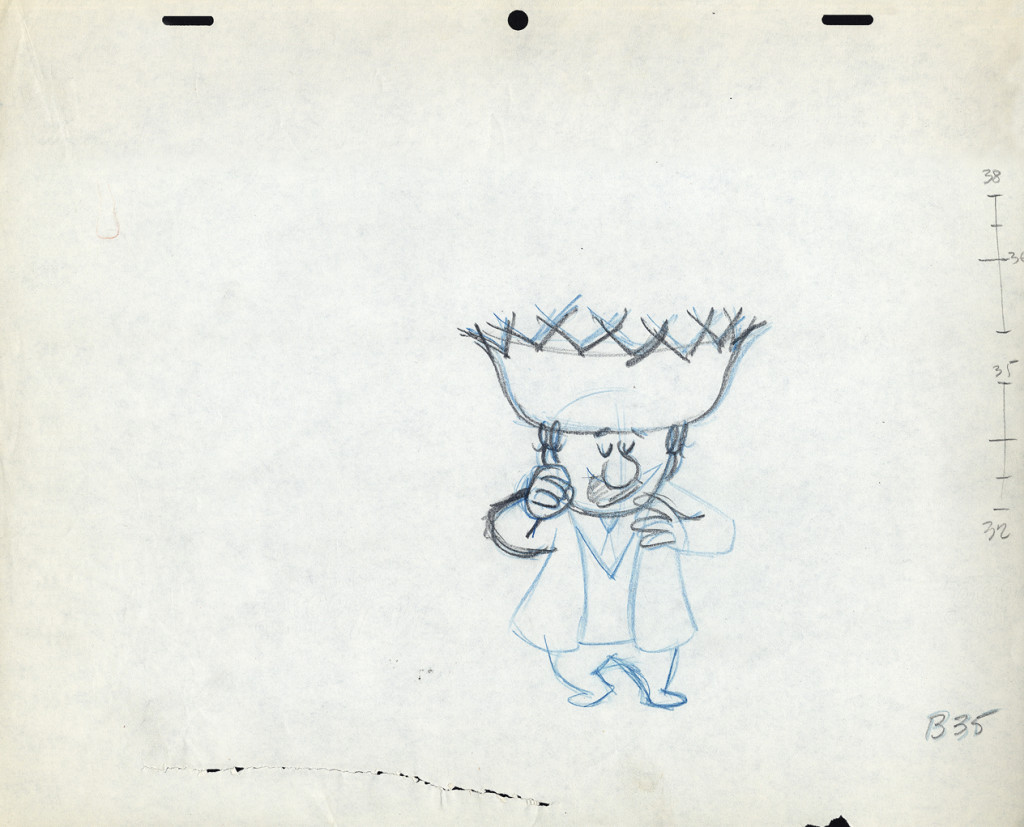

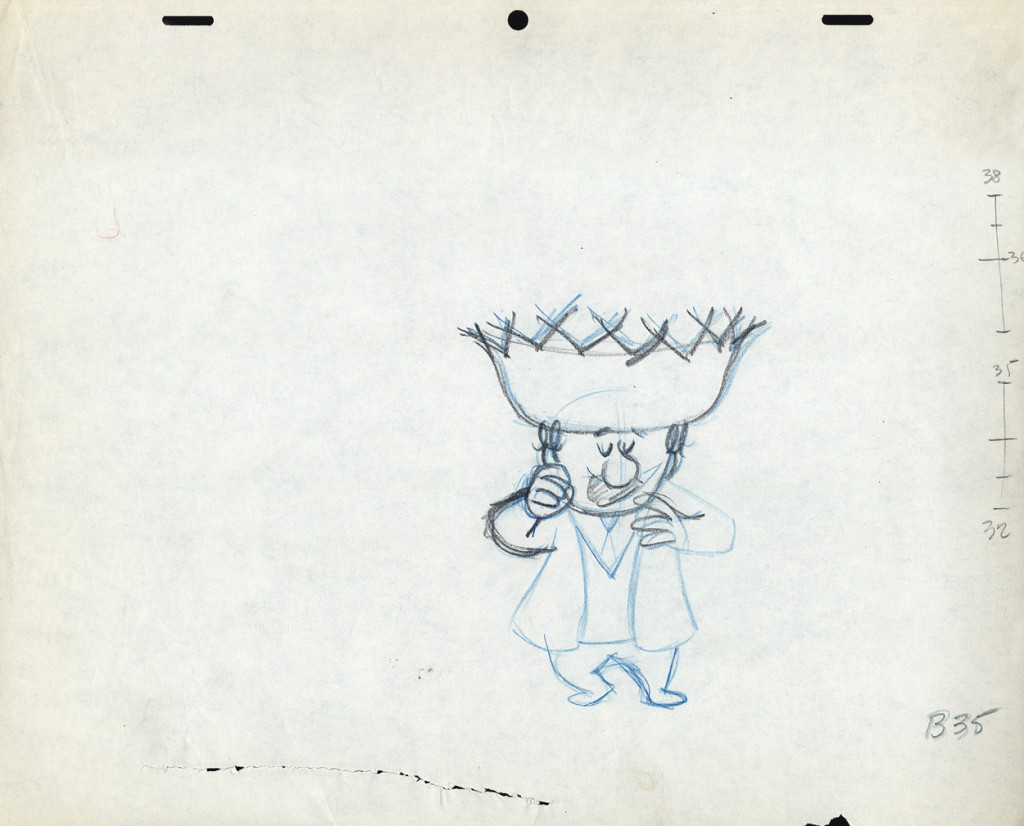

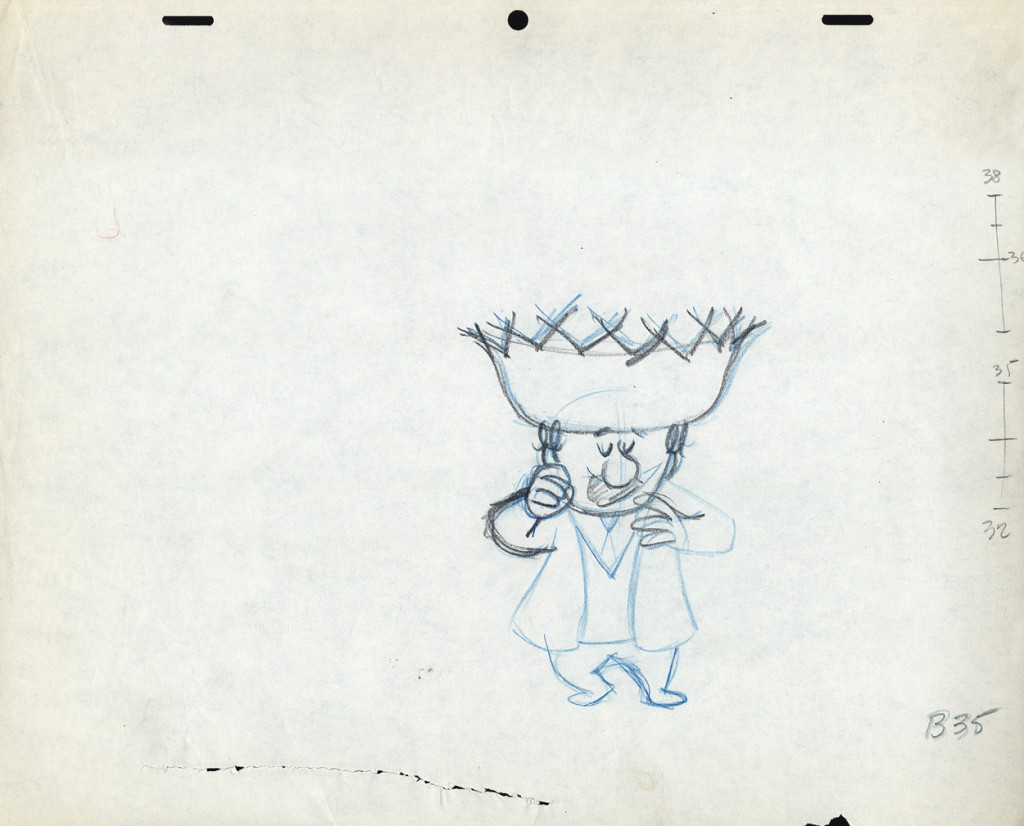

B35

B35

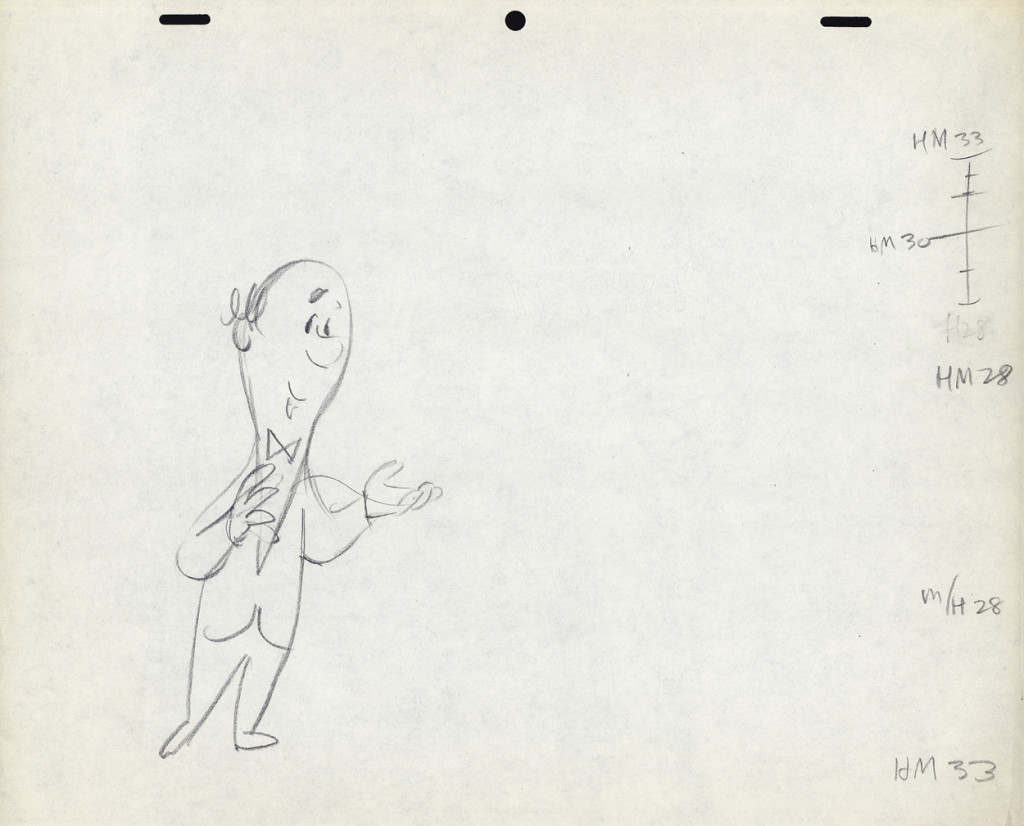

These ladders are done correctly, per the Disney system.

#34 is half way between #32 & #35;

#33 is half way between #32 & #34.

#36 is half way between #35 & #38;

#37 (the 1/4 mark) is half way between #36 & #38.

However, Grim Natwick told me

- demanded of me –

that all ladders should appear on the lower numbered drawing.

The ladder here should be on drawing #32 for all art

going into the upcoming extreme, #38.

Lu never followed this rule, which means the

assistant generally had to search for the chart.

The Second scene

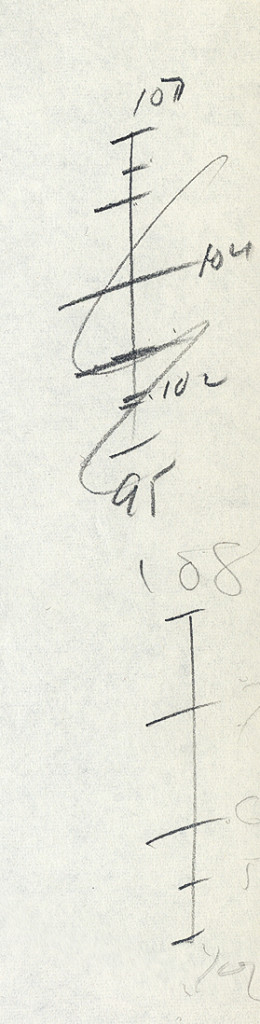

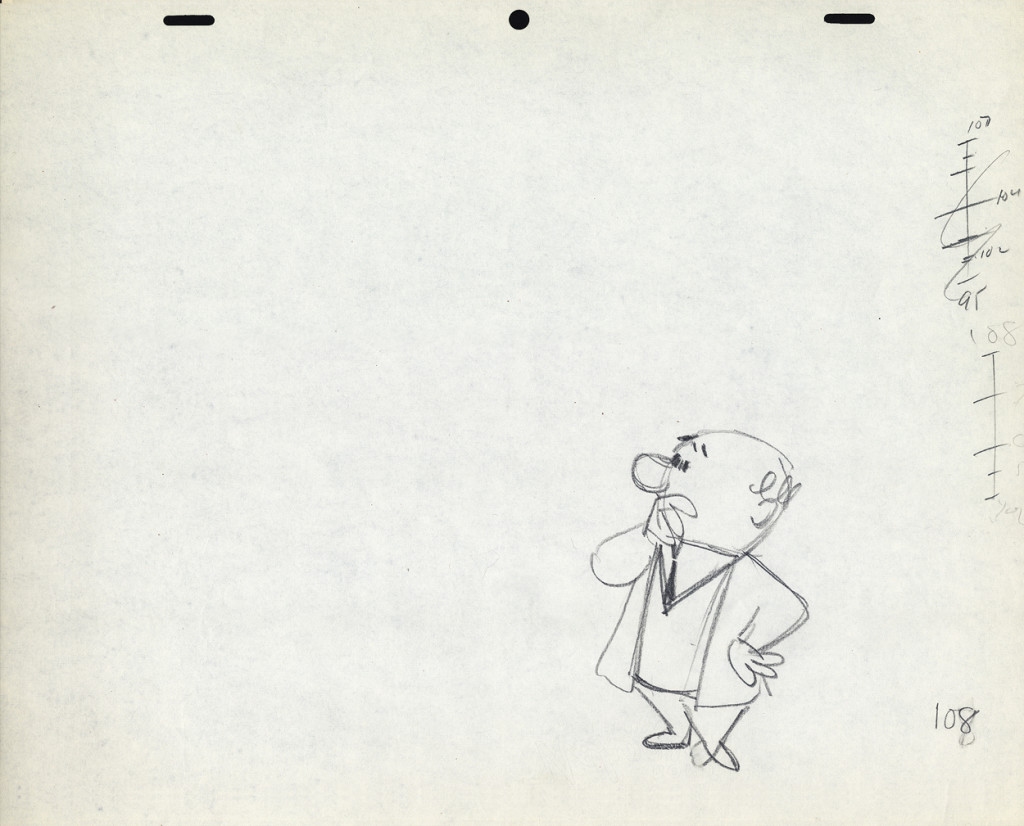

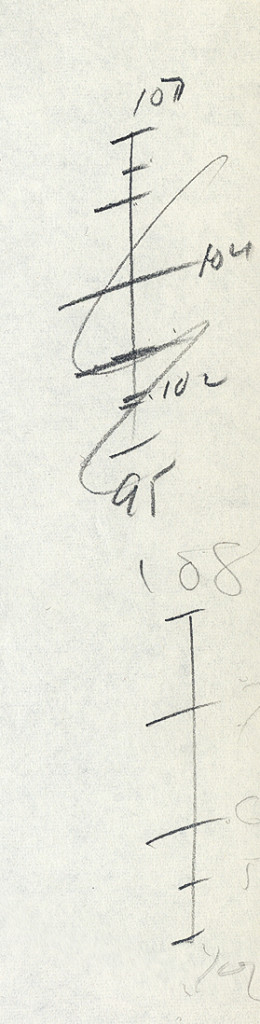

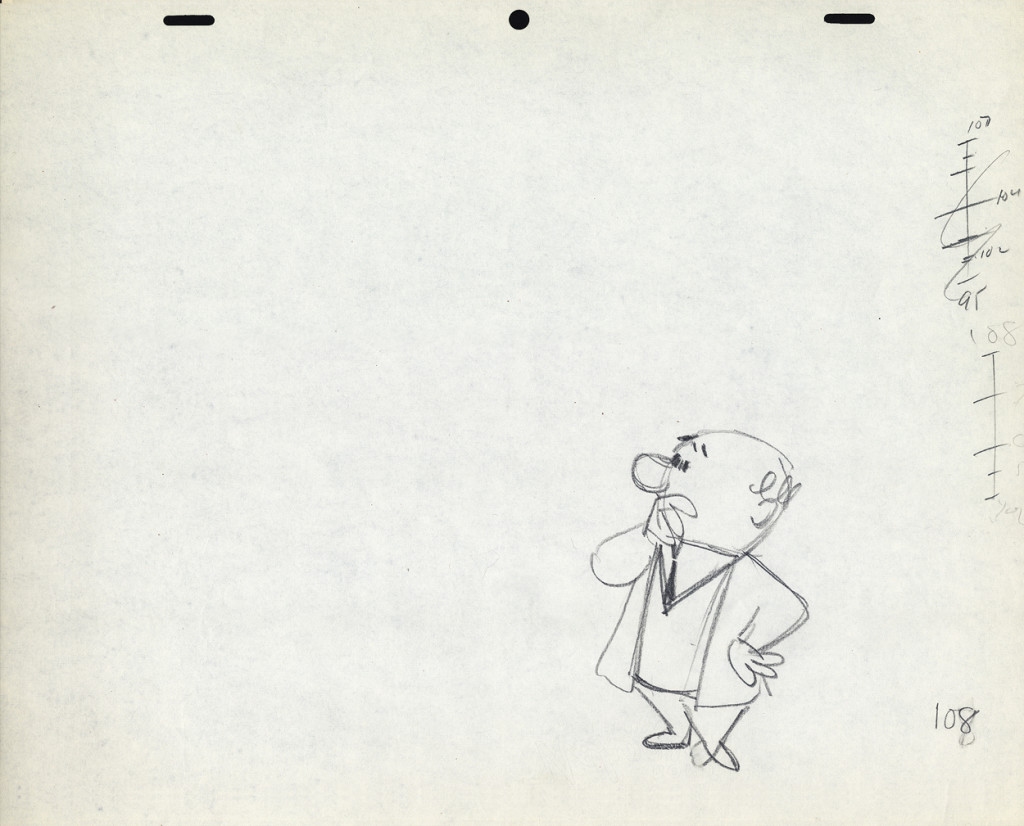

B108

B108

This ladder is typical of Lu’s animation.

It would seem that #106 is 1/3 of the way between #108

and #105 is half way between #106 and #109.

and it also looks like #107 is 2/3 of the way between #108 and #109.

Because the numbers come on the last of the extremes, here,

more confusion is allowed to settle in.

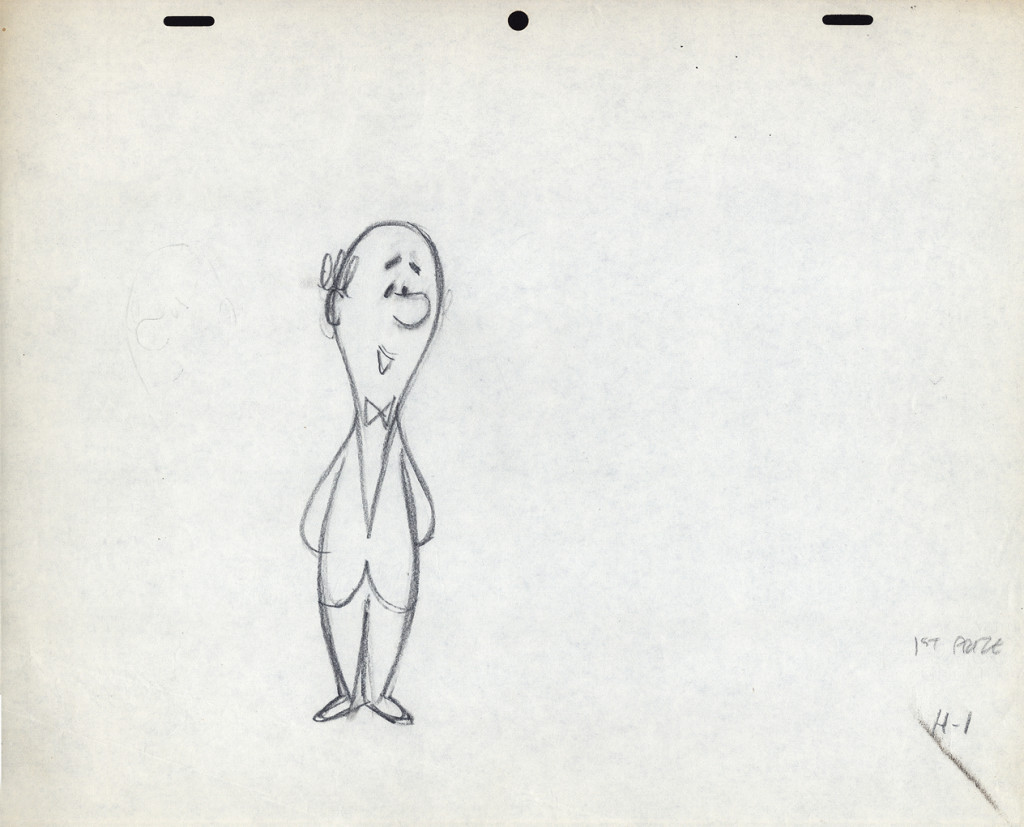

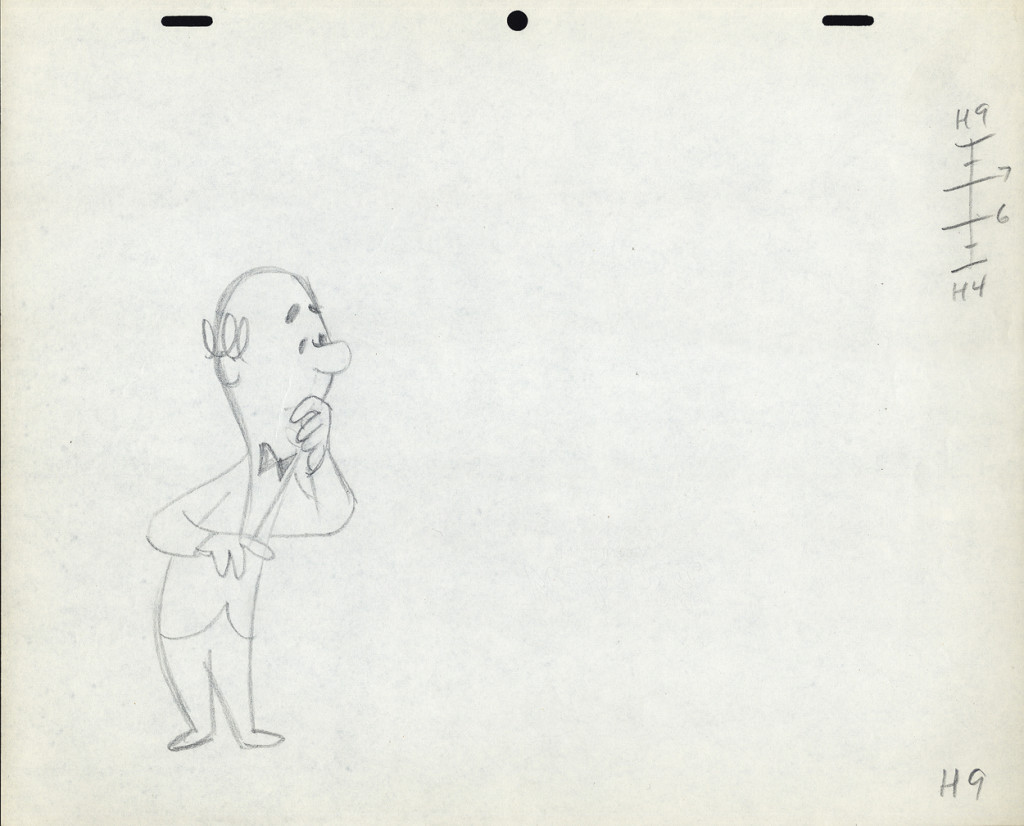

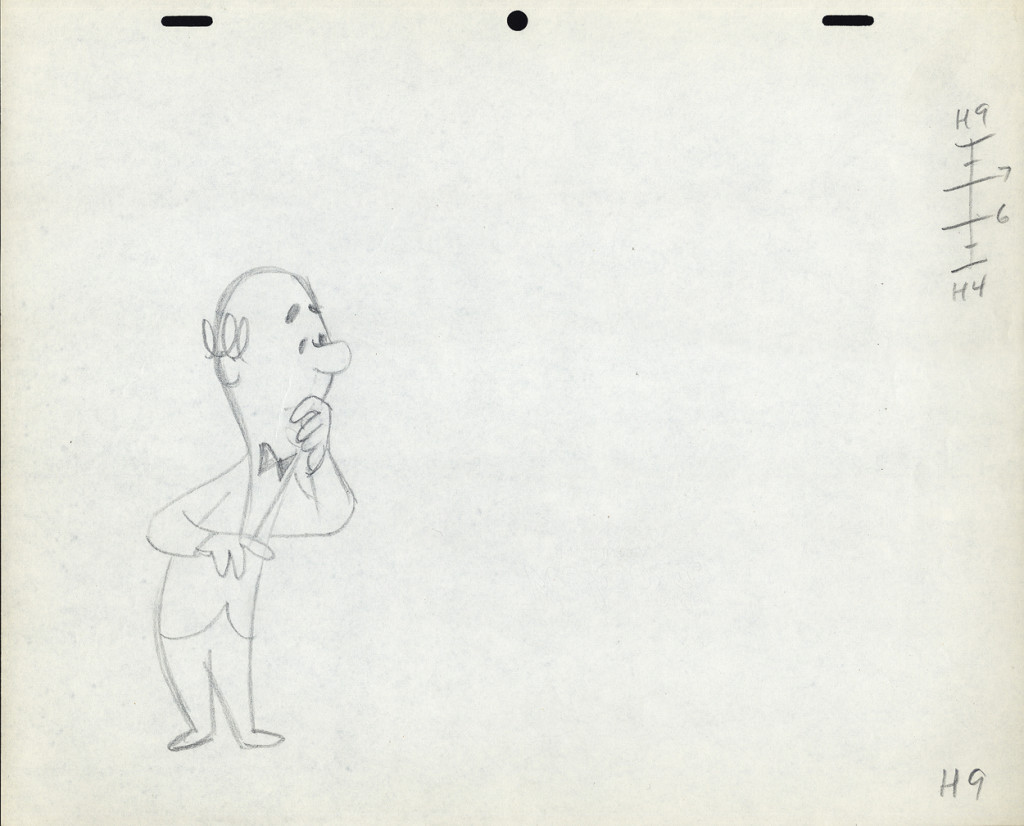

H9

H9

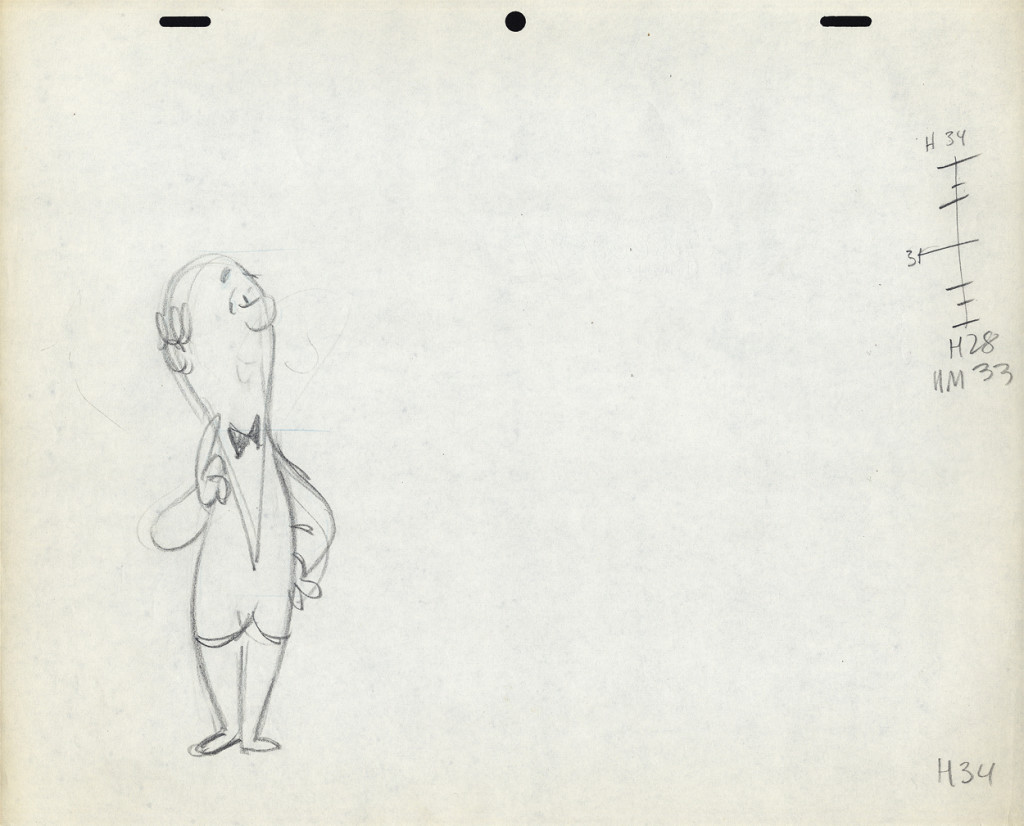

Again, the ladder appears on the later extreme. The assistant

shouldn’t have to go looking for it. The ladder should be on

the first drawing involved in the breakdown.

Again, the breakdown drawings are on 1/3′s, and

the inbetweens are 1/2′s of that. It makes it harder on the

people following up on the clean-up & inbetweens.

I don’t know if this style of Lu’s was a product of where he learned to animate or not. Jack Schnerk, a comparable animator – whose work I loved (even though he had a rougher, harder to clean up drawing style) – always broke his timing in halves and halves again. There were times when his animation went to one’s and he did most of all the drawings. I assumed he had an unusual timing, and he didn’t want to burden the Assistant with his schema. He also always carried the breakdown charts on the earlier numbered drawing – per Grim Natwick’s comment. In some way I felt that Lu was rushed to get on with the scene, and whatever method he used would be to get him there more quickly. (It was the assisting that was slowed down.) This may have been a product of his attempts to devise some type of improvisation in the animation. Lu’s work, on screen, was usually excellent, so he didn’t much hurt anything in his method.

It might also have been his method of trying to put SNAP into the animation. This was a WB trait from the mid-late Thirties. It was certainly in Lu’s animation. No doubt a hold-over from Clampett’s early days of directing.

The final thing to note is that Lu usually worked on Top Pegs. Animating on Top Pegs makes it impossible to “roll” the drawings and check on the movement of more than 3 drawings. You can only “flip” the three, checking the one inbetween, but it didn’t give you a good indication of the flow of the animation. This is obviously necessary in animating on paper. It also made it difficult for the cameraman as well as those following behind the animator. If there were a held overlay, this would have to be on bottom pegs since the animation is on top pegs. That requires extra movement of the expensive cameraman to change all the animation cels after lifting the bottom pegged overlay. It also risks the possible jiggling of the overlay as it’s continually moved for the animating cels.

Animation &Animation Artifacts &Commentary &commercial animation &Models &repeated posts 13 Jun 2013 09:07 am

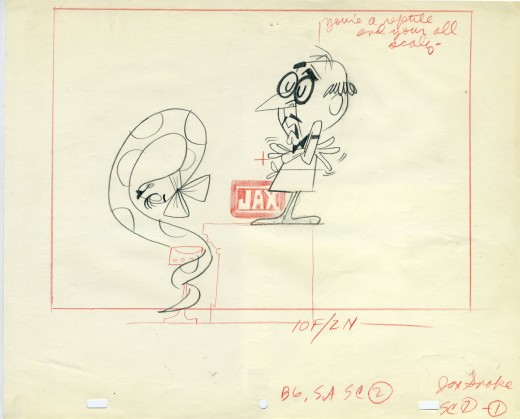

Jax Beer – recap

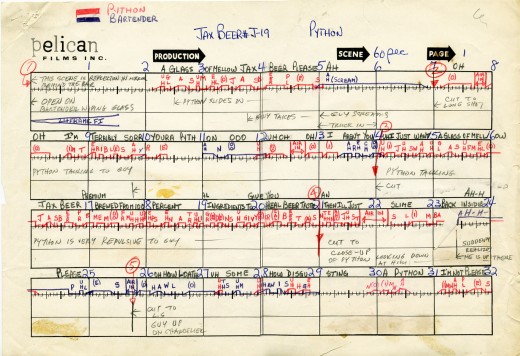

- In November 2006 I posted the storyboard, workbook and final layouts for a Jax Beer spot which was directed by Mordicai Gerstein. I thought it interesting enough to recap the two posts, so here they are.

- This is the material for a Jax Beer commercial. It was done by a NY studio named Pelican in 1962. There were about 75 people on staff at Pelican back then.

This spot was directed by Mordi (Mordicai) Gerstein. He left animation in th 70′s to write & illustrate children’s books. (He won the Caldecott Medal for his book, The Man Who Walked Between The Towers. This was the book I adapted to animation in 2005.)

What follows is the storyboard and the director’s workbook. (It appears to be an agency board, though it’s drawn in a style that looks to be Mordi Gerstein‘s. Perhaps boards from the agency were drawn by the studios back in 1964; I’m not sure. The layouts were drawn by the same artist.)

_____(Click any image to enlarge.)

The workbook has several flaps on it that indicate changes in timings. There are also glue stains where I assume other flaps fell off. (See page one, last row, first column.) Each column represents 16 frames/one foot of film. Odd numbers are marked off.

Each row contains 8 feet of film/128 frames. Each page represents 32 feet/512 frames. It would have been smarter to keep to even numbers.

More modern exposure sheets generally have 80 frames/five feet per page. This also divides into two feet of 16mm film. (Handy.) The numbers add and divide smartly and easily. But then most people don’t use exposure sheets anymore.

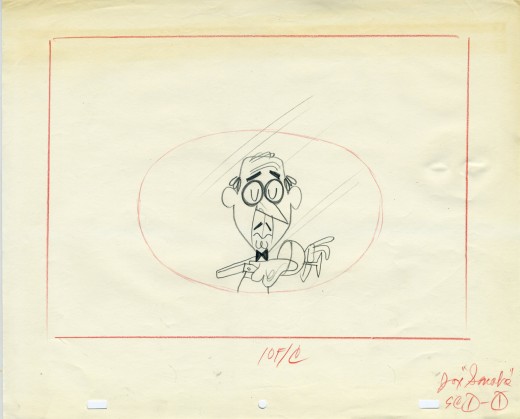

- Continuing with the above post, a Jax Beer commercial, I present some of the film’s layouts. This represents about 2/3 of them.

- Continuing with the above post, a Jax Beer commercial, I present some of the film’s layouts. This represents about 2/3 of them.

The art was done by Mordi (Mordicai) Gerstein, who also directed the spot. Grim Natwick animated the spot and Tissa David assisted him. Of course, this was in the days before auido tapes could be handed out, so the animator would get a phonograph of the soundtrack. They could mark it with a white pencil to indicate key spots.

I thought that this in conjunction with yesterday’s prep material gave a good indication of the preproduction that went into making a commercial back in 1962.

That said, here are the layouts:

(Click on any image to enlarge.)

Books &Commentary 13 May 2013 05:36 am

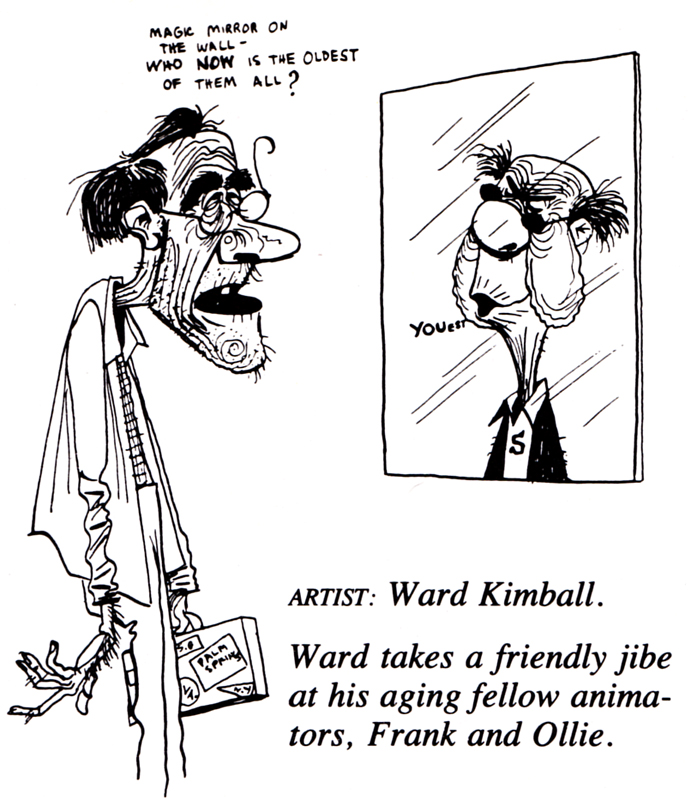

Illusions of Thomas, Johnston & Disney

- The Illusion of Life by Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston was first published in 1981. The book came out with a large splash and overwhelming acceptance by the animation community. It’s since remained the one bible that animation wannabees turn to as a source of inspiration and an attempt to learn about that business.

- The Illusion of Life by Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston was first published in 1981. The book came out with a large splash and overwhelming acceptance by the animation community. It’s since remained the one bible that animation wannabees turn to as a source of inspiration and an attempt to learn about that business.

I admitted a couple of weeks back that though I must have been one of the very first to have bought the book, I’d never actually read it. I spent hours poring over the many pictures and the extensive captions, but the actual book – I didn’t read it. I can’t say why, but this was my reality.

Then not too long ago, Mike Barrier wrote that he was not a supporter of the book and its theories, I wondered about that writing and decided to reconsider reading it. I knew I had to go back to find out what I’d stupidly ignored, so I started reading.

The book starts out with a lot of history of animation, something routine and expected from the two animators that lived through a good part of the story. As a matter of fact Thomas and Johnston were at the center of the history. It didn’t take long for the animation “how-to” to kick in. For the remainder of the book, using that history, the two master animators explained how and why Disney animation was done, in their opinions. They write about processes and systems set up at Disney during their tenure there. They write about theories and methods of fulfilling those theories. There’s a lot for them to tell and they’ve succinctly organized it into this book, as a sort of guide.

However, at two points they go wildly into a divergent path from the one that they started building. Their methods altered and, to me, seemed to be about the finances of doing the type of animation they did, rather than the reason. Impractical as those original theories were, I’d believed in the myth all those years to start changing now. So I want to review these two stances instead of outwardly reviewing the book. Besides it’s too long since the book has stood in its own royal space for me to pretend that I could properly review it.

The growth of animators at the Disney studio relied on a system wherein each of the better animators was assigned one character. Unless there was a minimal action by some external character, the one animator ruled over the character.

- Bill Tytla did Stromboli in Pinocchio. He did principal scenes of Dumbo in that film. He handled the Devil in Fantasia (as well as all his twisted mignons within those scenes.) Tytla worked on the seven dwarfs but was the principal animator of Grumpy.

- Bill Tytla did Stromboli in Pinocchio. He did principal scenes of Dumbo in that film. He handled the Devil in Fantasia (as well as all his twisted mignons within those scenes.) Tytla worked on the seven dwarfs but was the principal animator of Grumpy.

- Fred Moore also did the dwarfs in Snow White but seemed to focus on Dopey. He did Lampwick in Pinocchio and Mickey in The Sorcerer’s Apprentice.

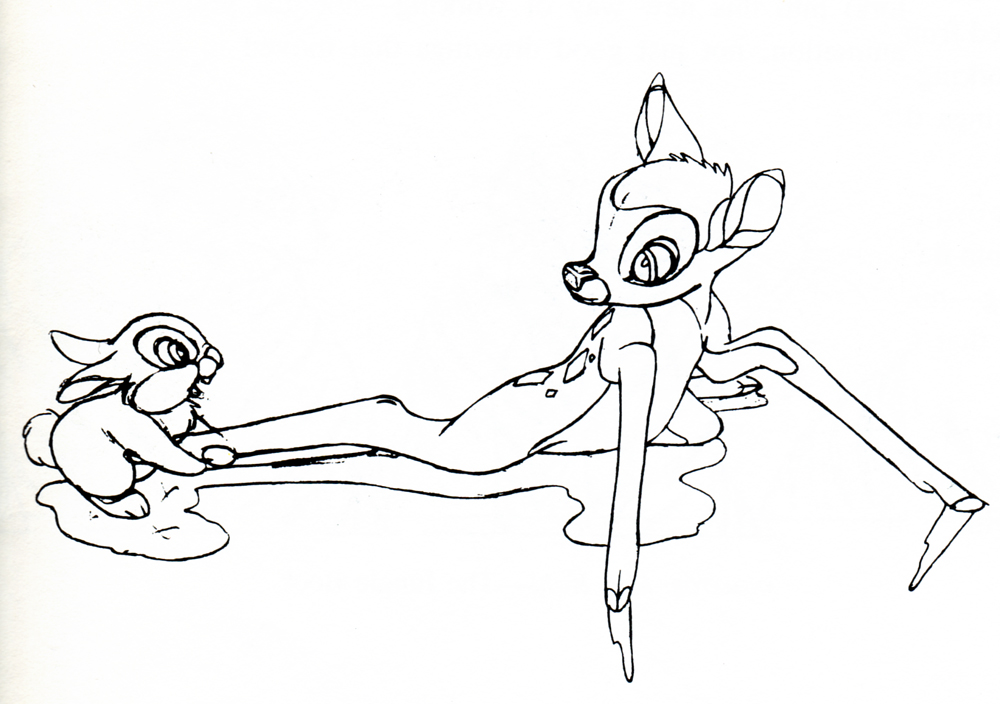

- Marc Davis started as an assistant under Grim Natwick on Snow White. He became the Principal artist behind Bambi, the young deer. He did Alice in Alice in Wonderland, Tinkerbell in Peter Pan, Maleficent in Sleeping Beauty and Cruella de Ville in 101 Dalmatians.

- Frank Thomas did Captain Hook in Peter Pan, the wicked Stepmother in Cinderella, Bambi and Thumper on the ice in Bambi.

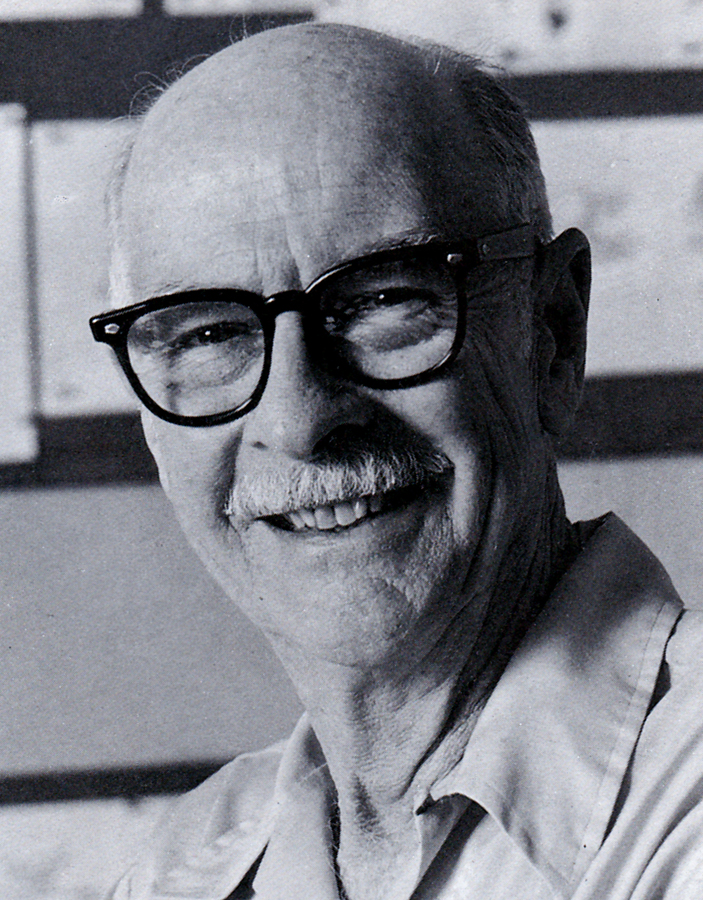

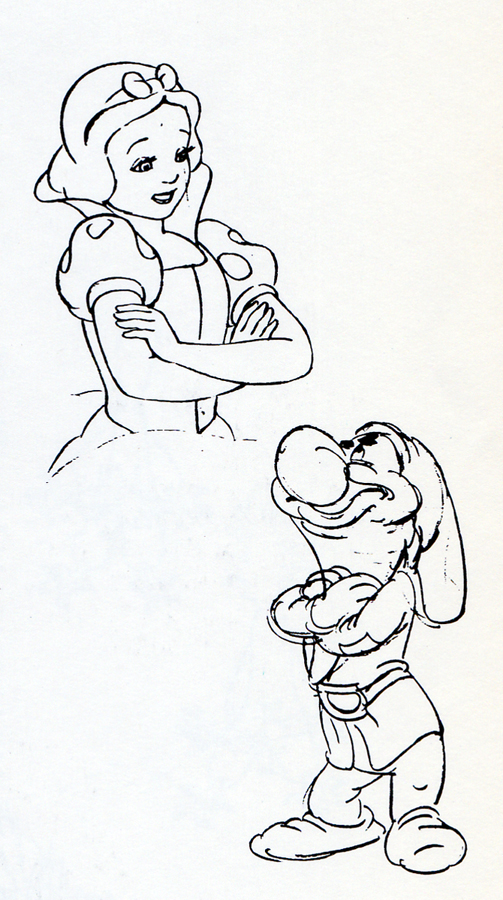

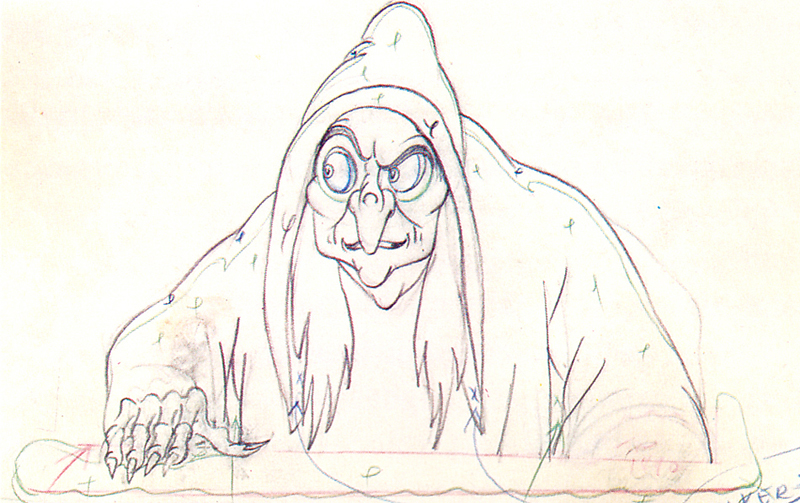

- Ham Luske and Grim Natwick did Snow White. The two sides of her personality came about because of conflicts between the two animators. This was a way for Walt to complicate Snow White’s character; he employed two animators with different strong opinions about her movement. By putting Ham Luske in charge, he was sure to keep the virginal side of Snow White at the top, but by having Natwick create the darker sides of the character, Disney created something complex.

Many animators fell under these leaders’ supervision and tutelage, also working on one principal character in each film. This system was something they swore by and broadcast as their way of working at the studio. It would allow the individual characters to maintain their personalities as one animator led the way.

But as Walt grew more involved with his theme park and his television show and the live action movies that were doing well for the studio, things changed at the animation wing of the studio. It became clear, with the over budgeted spending on Sleeping Beauty and the new demands for a different look once xerography entered the picture in 1959. The rhythm and personality of the productions changed, and their methods of animation changed. Walt also sorted out nine loyalists to be his “Nine Old Men” thus dividing the animators into groups, a hurtful way of setting up competition among the animators. ________________________Kahl, Davis, Thomas, Walt, Jackson, Johnston seated

But as Walt grew more involved with his theme park and his television show and the live action movies that were doing well for the studio, things changed at the animation wing of the studio. It became clear, with the over budgeted spending on Sleeping Beauty and the new demands for a different look once xerography entered the picture in 1959. The rhythm and personality of the productions changed, and their methods of animation changed. Walt also sorted out nine loyalists to be his “Nine Old Men” thus dividing the animators into groups, a hurtful way of setting up competition among the animators. ________________________Kahl, Davis, Thomas, Walt, Jackson, Johnston seated

Thomas and Johnston get to justify this

in their book.

Let me read a section from the book to you:

- “Under this leadership, a new and very significant method of casting the animators evolved: an animator was to animate all the characters in his scene. In the first features, a different animator had handled each character. Under that system even with everyone cooperating, the possibilities of getting maximum entertainment out of a scene were remote at best. The first man to animate on the scene usually had the lead character, and the second animator often had to animate to something he could not feel or quite understand. Of necessity, the director was the arbitrator, but certain of the decisions and compromises were sure to make the job more difficult for at least one of the animators.

“The new casting overcame many problems and, more important, produced a major advancement in cartoon entertainment: the character relationship. With one man now animating ever character in his scene, he could feel all the vibrations and subtle nuances between his characters. No longer restricted by what someone else did, he was free to try out his own ideas of how his characters felt about each other. Animators became more observant of human behavior and built on relationships they saw around them every day.”

The question is, now, what are we to make of this statement? Do Thomas & Johnston mean for us to believe that they do more than the single character per film? Does it mean that, like all underprivileged animators everywhere, they now receive scenes rather than characters? Are they trying to tell us that the old, publicized method of animation they did during the “Golden Days” no longer exists?

The question is, now, what are we to make of this statement? Do Thomas & Johnston mean for us to believe that they do more than the single character per film? Does it mean that, like all underprivileged animators everywhere, they now receive scenes rather than characters? Are they trying to tell us that the old, publicized method of animation they did during the “Golden Days” no longer exists?

To be honest I don’t know. Also when are they talking about? At the start of the Xerox era? In the days since Woolie Reitherman has been directing? Do they mean ever since they’ve retired and started writing this book?

Let’s go back a bit.

- In 101 Dalmatians, Marc Davis did Cruella de Vil. That’s it. That’s all he was known for in that film. Oh wait, there were a couple of scenes where he did the “Bad’uns,” Cruella’s two sidekicks. He did these ging into or out of a sequence. In Sleeping Beauty (if we’re going back that far) Davis did Maleficent. Oh, he also did her raven sidekick.

- Milt Kahl did Prince Philip in Sleeping Beauty – and every once in a while his father. He did key Roger and Perdita scenes in 101 Dalmatians. He did Shere Khan in The Jungle Book.

- Milt Kahl did Prince Philip in Sleeping Beauty – and every once in a while his father. He did key Roger and Perdita scenes in 101 Dalmatians. He did Shere Khan in The Jungle Book.

Kahl also seems to be the go-to-guy when they’re looking to have the character defined. The closest thing to Joe Grant’s model department in the late Thirties. If you weren’t sure how Penny might look in a particular scene, you might go to Kahl who’d draw a couple of pictures for you. But that was Ollie Johnston‘s character. You’d probably go to him first, but Johnston would go to Kahl if he needed help.

Kahl also did Robin and some of Maid Marian in Robin Hood. I could keep going on, but let’s take a different direction.

Look at one of Thomas’ greatest sequences, the squirrels in the tree. Starting with Seq.006 Sc.23 and almost completely through and ending with Seq.06 Sc.136 Frank Thomas did the animation. That’s a lot of footage. Yes, that represents four characters: Merlin and Wart as squirrels, as well as the older and younger female squirrels. He did the whole thing (and it’s one of the most beautifully animated sequences ever.)

Look at one of Thomas’ greatest sequences, the squirrels in the tree. Starting with Seq.006 Sc.23 and almost completely through and ending with Seq.06 Sc.136 Frank Thomas did the animation. That’s a lot of footage. Yes, that represents four characters: Merlin and Wart as squirrels, as well as the older and younger female squirrels. He did the whole thing (and it’s one of the most beautifully animated sequences ever.)

But when he was done with that and needed work, he didn’t stop on this film; he also did a bunch of scenes in the “Wizard’s Duel” between Merlin and Mad Madame Mim. Another big chunk.

Hans Perk has done a brilliant service for all animation enthusiasts out there. On his blog, A Film LA, he’s posted many of the animator drafts of feature films. You can find out who animated what scenes from any of the features.

However as Hans posts the batches of sequences, he gives little notes about what we’ll find when we open the drafts. In my view, Hans’ notes are also a treasure.

You can read remarks such as, “Masterful character animation by Milt Kahl and Frank Thomas, action by John Sibley and a scene by Cliff Nordberg.” That seems to tell us everything.

In Sleeping Beauty we can read, “This sequence shows, like no other, the division between Acting and Action specialized animators. Or at least it shows how animators are cast that way. We find six of the “Nine Old Men”, and such long-time Disney staples as Youngquist, Lusk and Nordberg, each of them deserving an article like the great one on Sibley by Pete Docter.”

Or in The Rescuers we read, “Probably the most screened sequence of this movie, the sequence where Penny is down in the cave was sequence-directed by frank and Ollie. They would plan their part of this sequence in rough layout thumbnails, then continue by posing all scenes roughly as can be seen in this previous posting.

“They relished telling the story that Woolie told them the animatic/Leica-reel/work-reel was JUST the right length, and when they posed out the sequence and showed it to Woolie, he said: “See? Just as I said: just the right length!” They kept to themselves that the sequence had grown to twice the length!”

The work, right to the retiring of all of the “Nine Old Men,” would seem to me to prove that these guys, regardless of whether they added one or two other characters to the scenes, did, in fact, take charge of the one starring character.

The work, right to the retiring of all of the “Nine Old Men,” would seem to me to prove that these guys, regardless of whether they added one or two other characters to the scenes, did, in fact, take charge of the one starring character.

This continues past the retirement of all the oldsters: Glen Keane animated the “beast” in Beauty and the Beast. He animated Tarzan in Tarzan, Aladdin in Aladdin, Ariel in The Little Mermaid, and Pocahontas in Pocahontas. Andreas Deja animated Jafar, the Grand Vizier in Aladdin, Scar in The Lion King, Lilo in Lilo and Stitch, and Gaston in Beauty and the Beast. Mark Henn animated Belle in Beauty and the Beast (from the Florida studio), Jasmine in Aladdin, young Smiba in The Lion King, and Mulan and her father in Mulan.

Need I go on? What are Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston talking about in their book? I’m confused.

I have a lot left to say about this book, much of it good, but next time I want to write about something else that confuses me with another somewhat contradictory statement in the book.

This has gotten a bit long, and I have to cut it here.

Bill Peckmann &Books &Chuck Jones &Illustration 07 May 2013 03:39 am

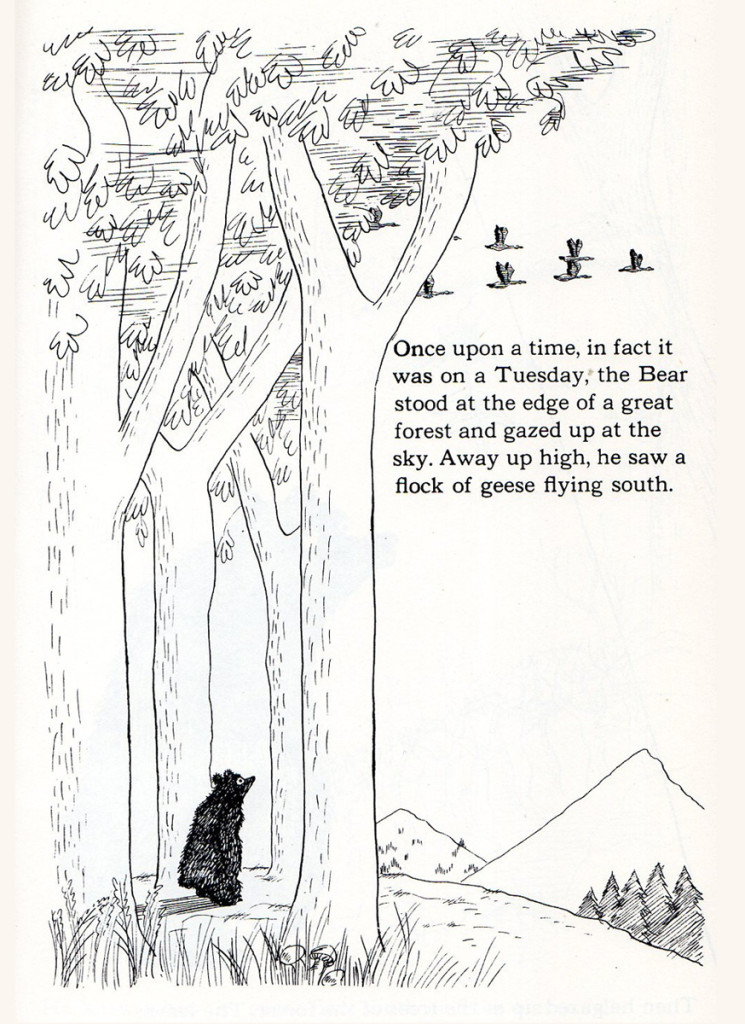

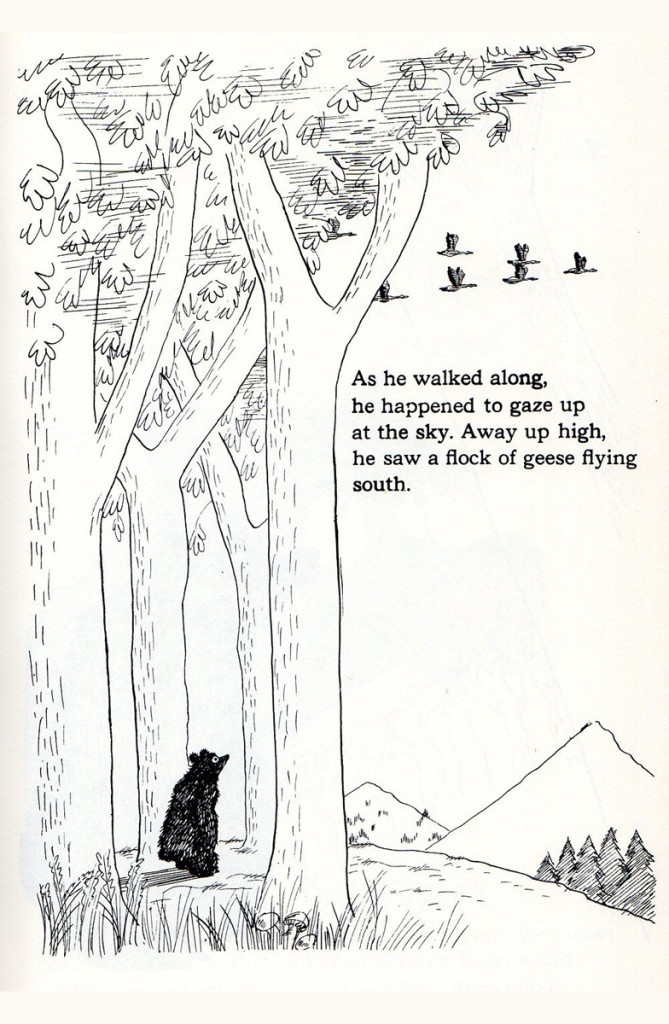

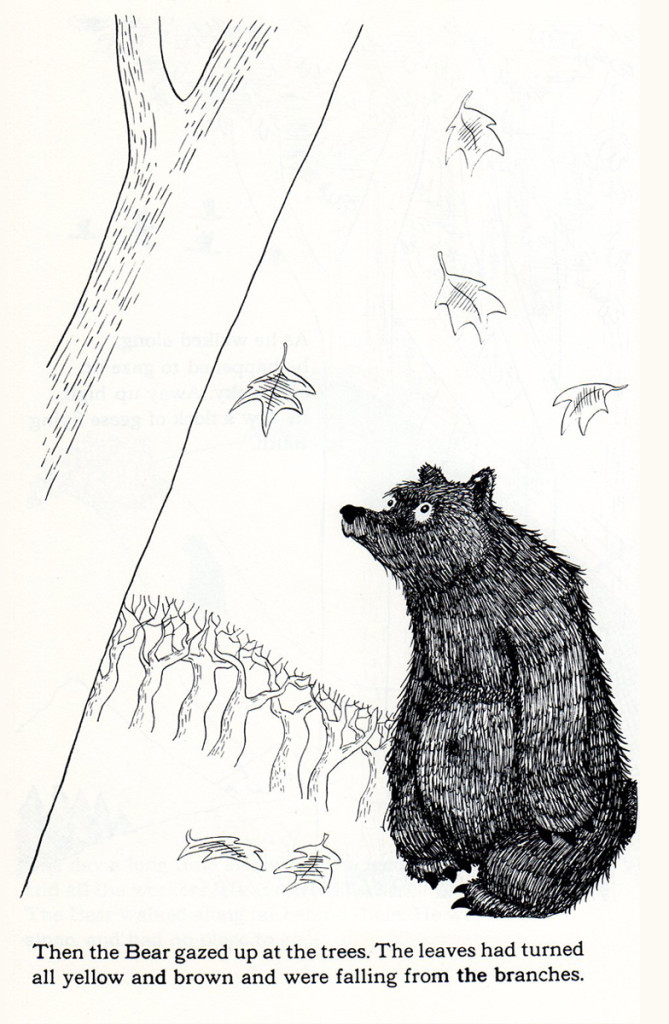

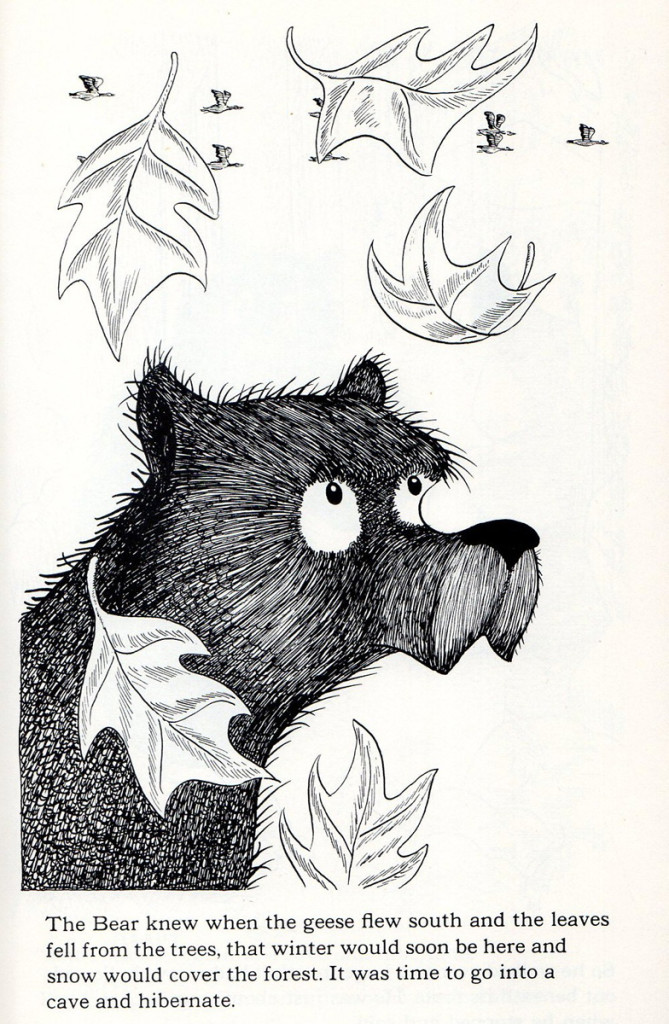

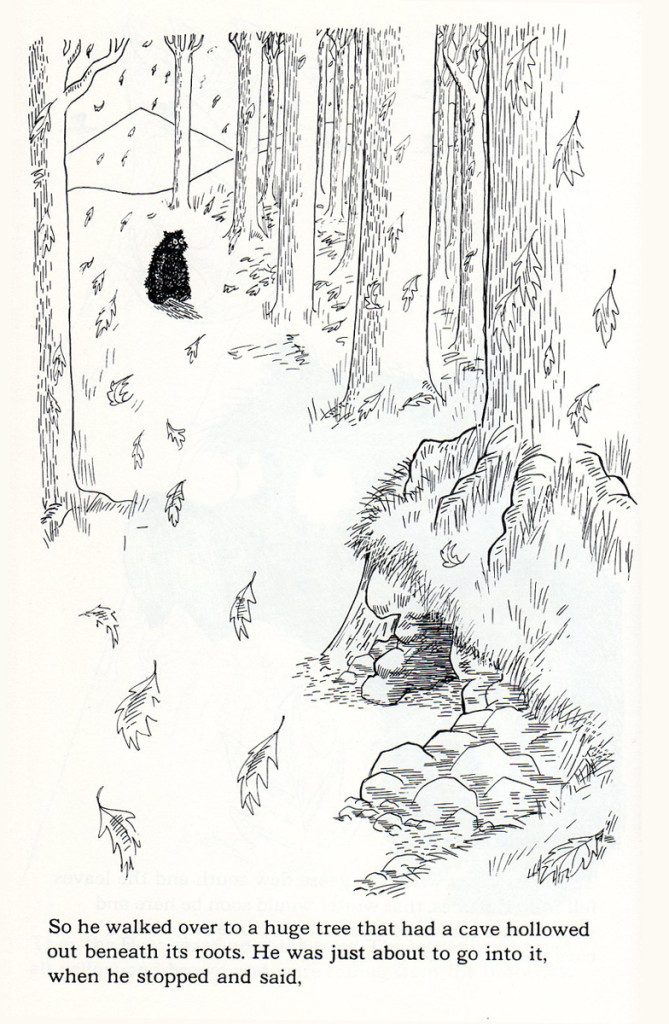

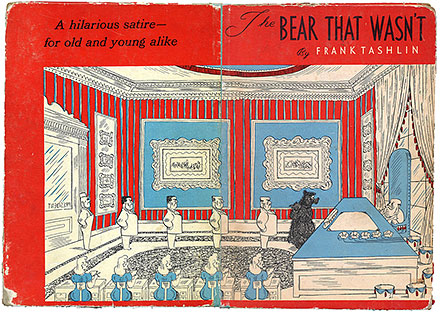

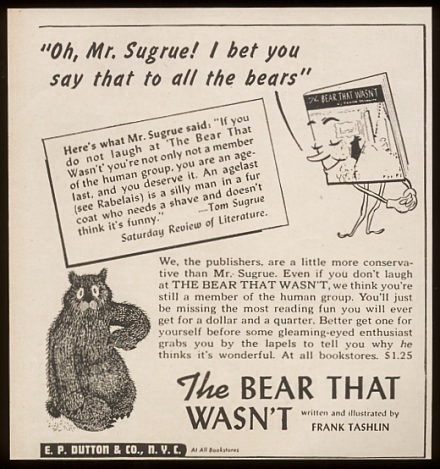

Bears

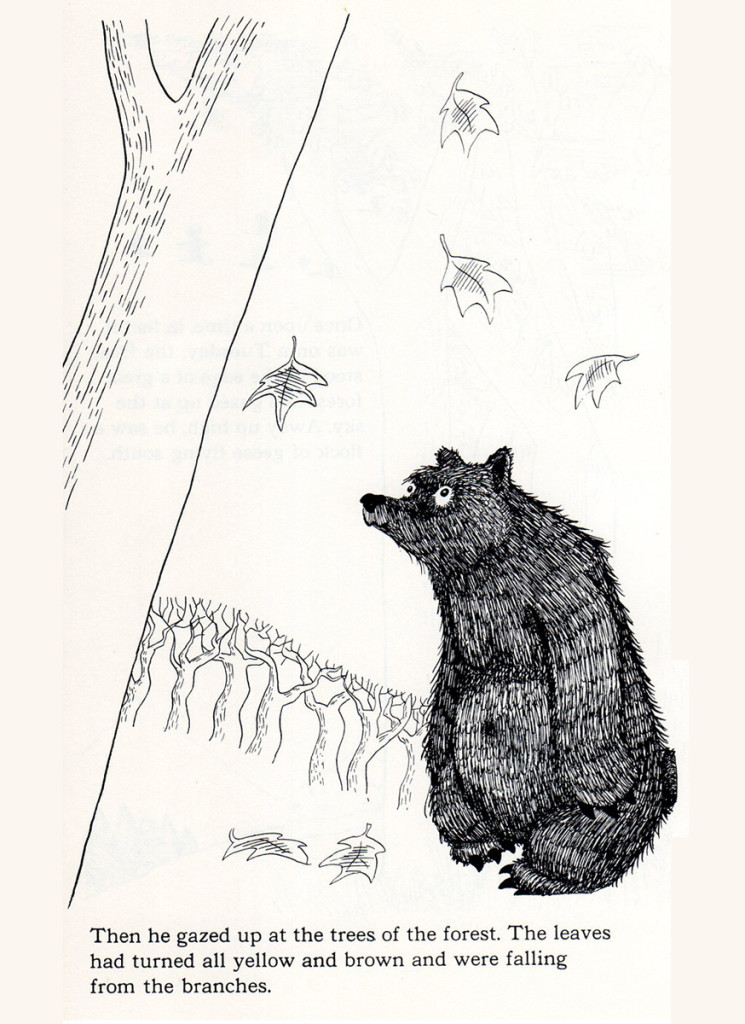

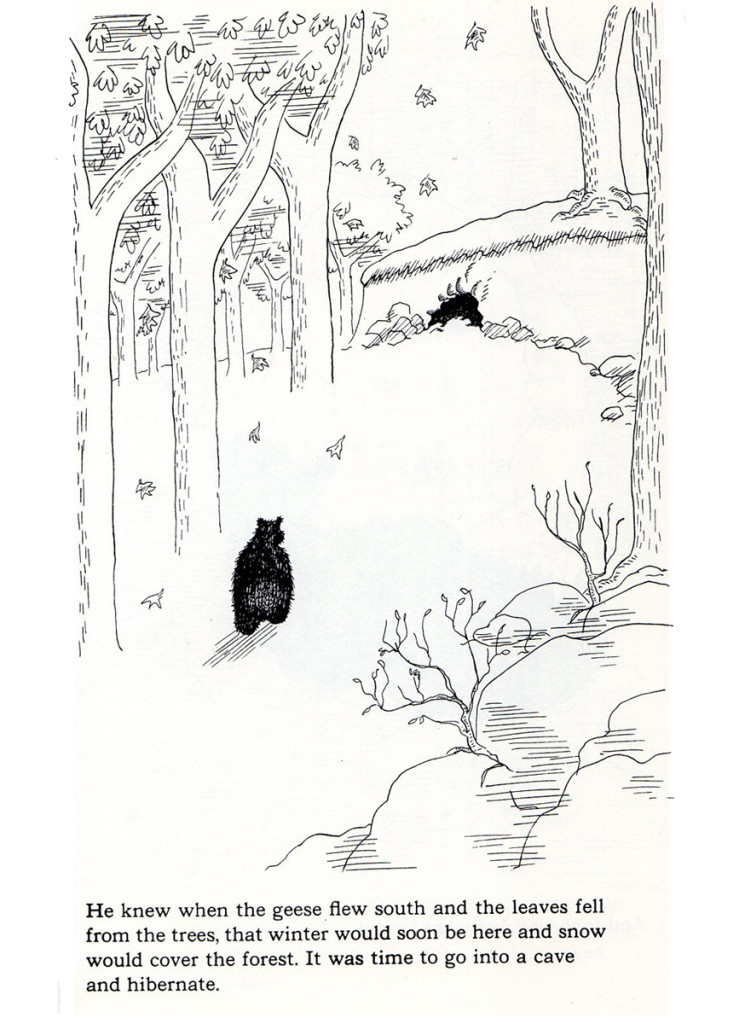

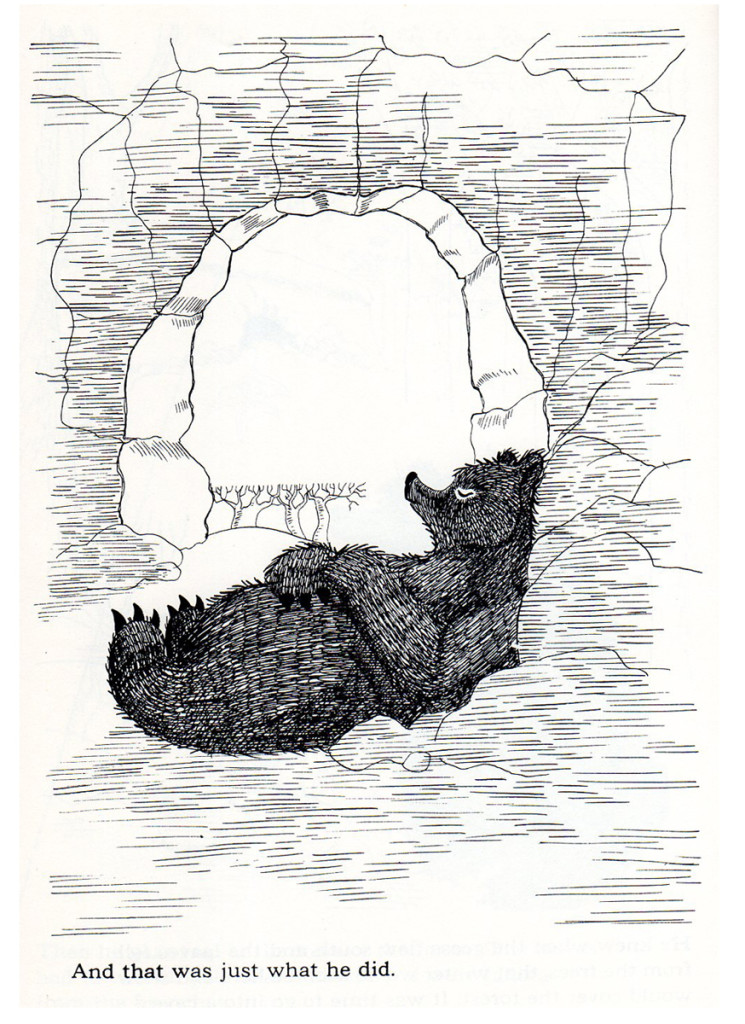

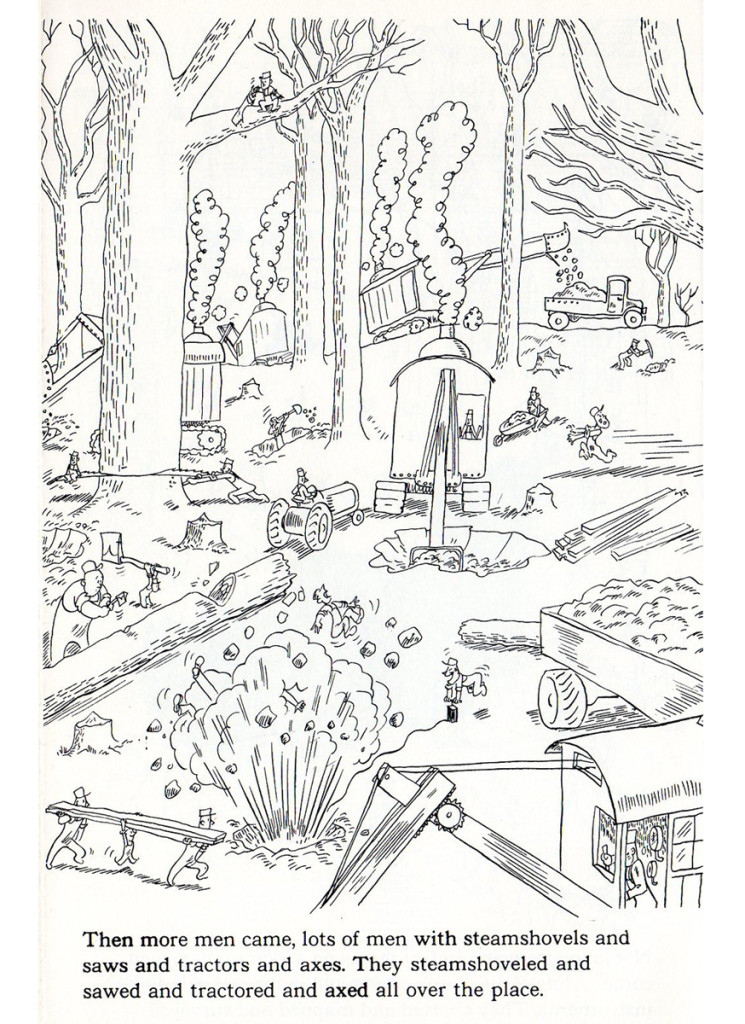

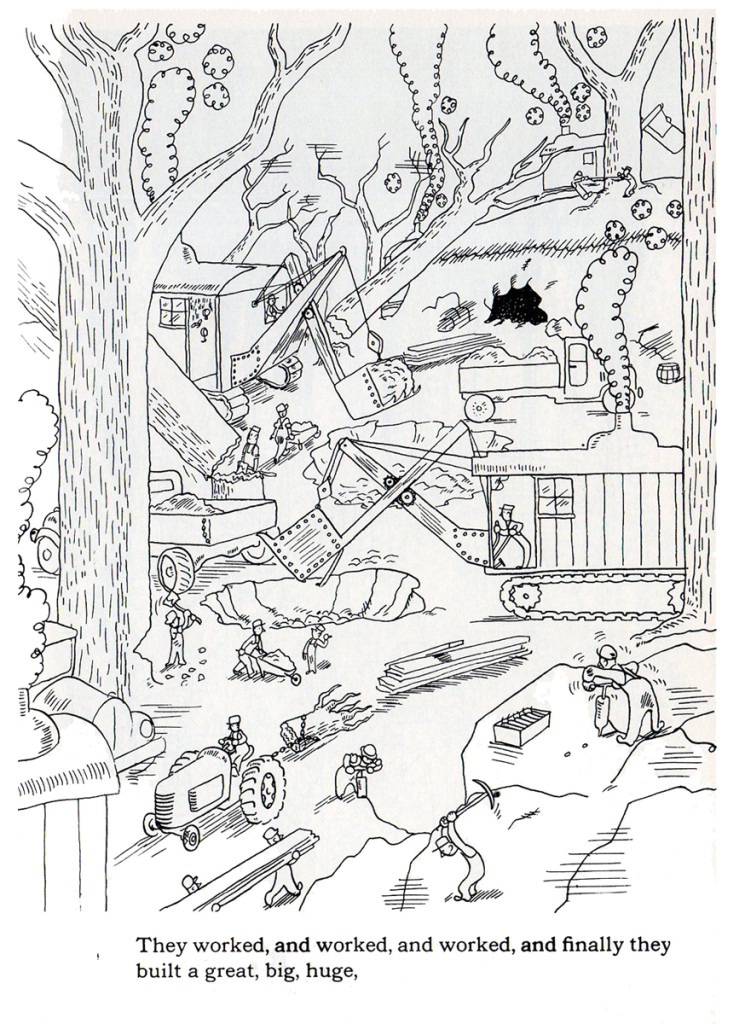

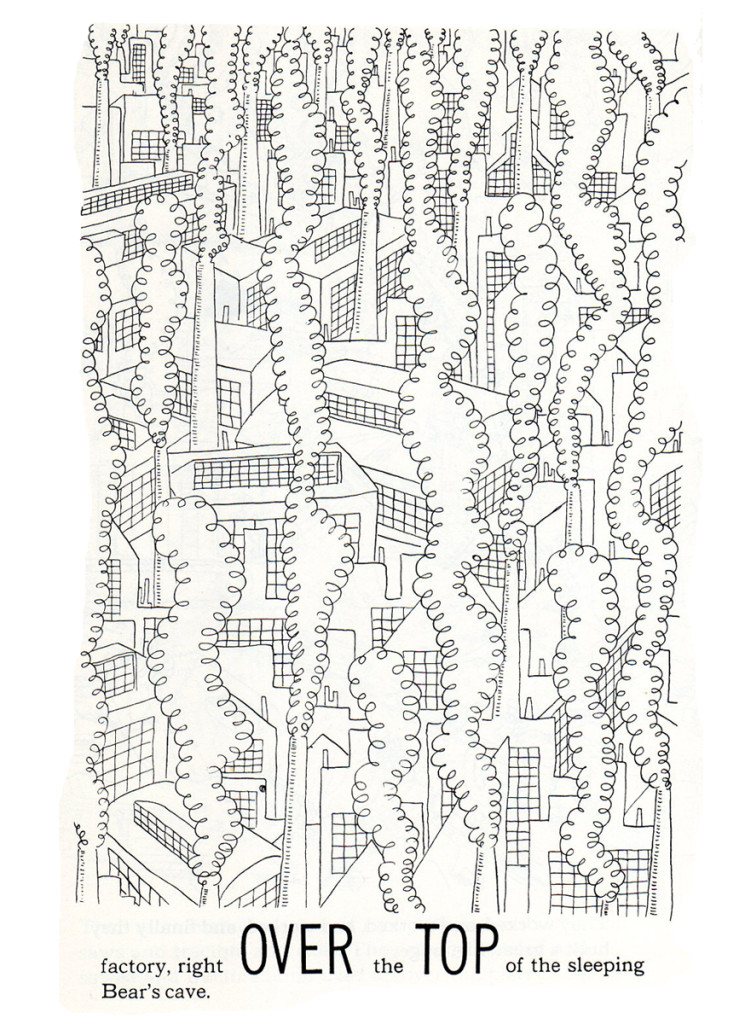

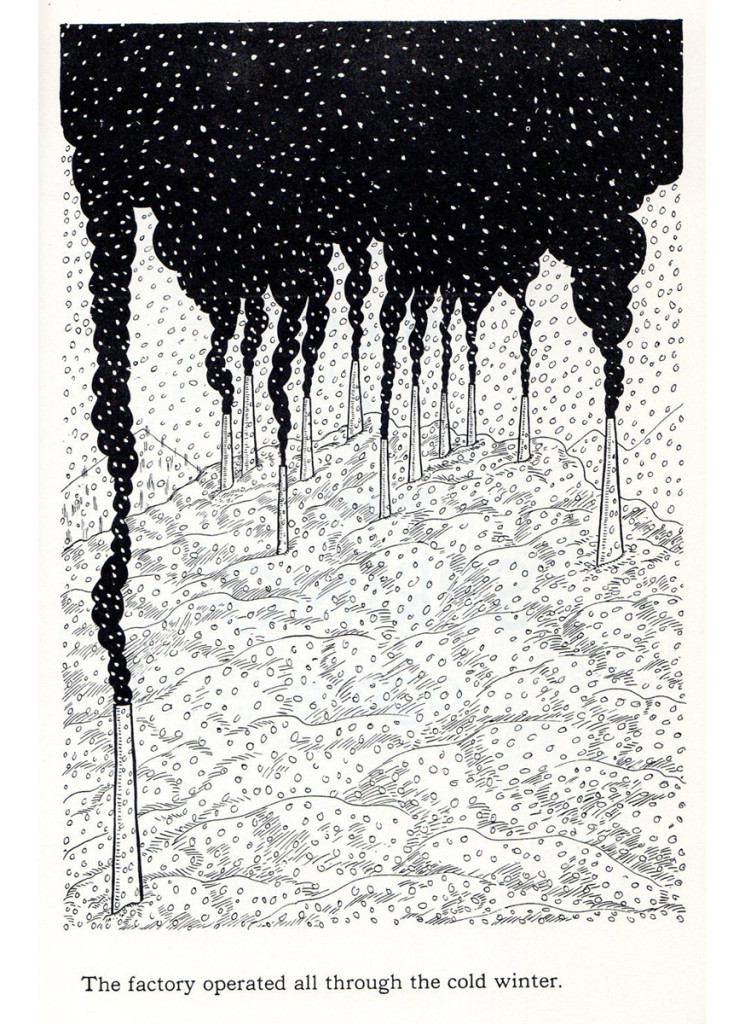

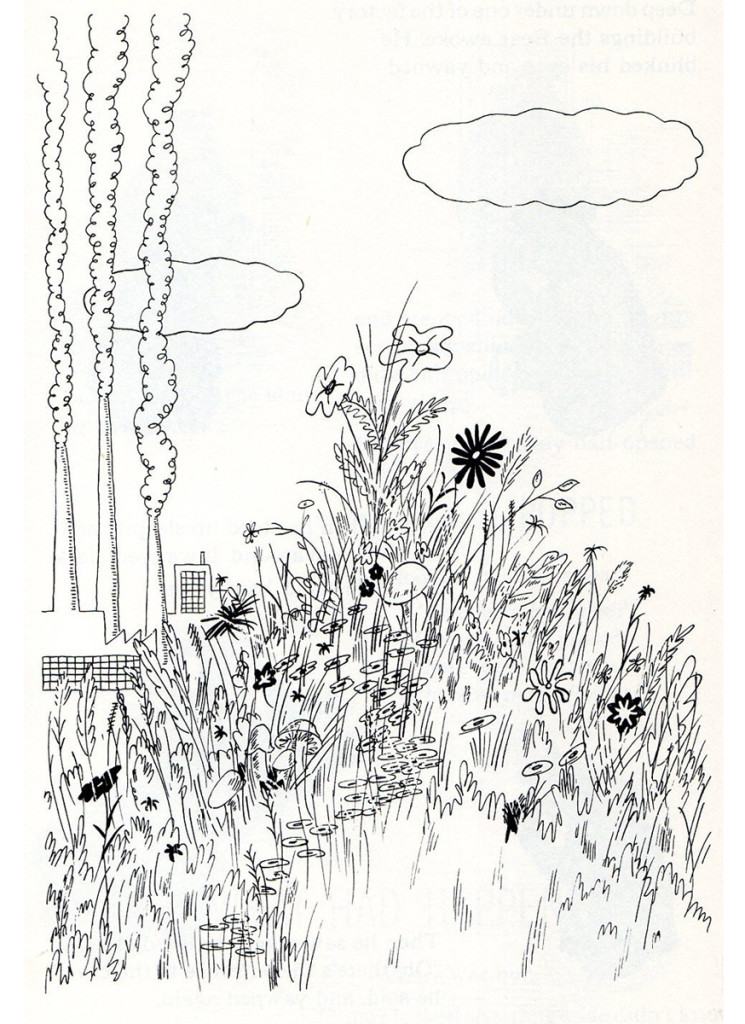

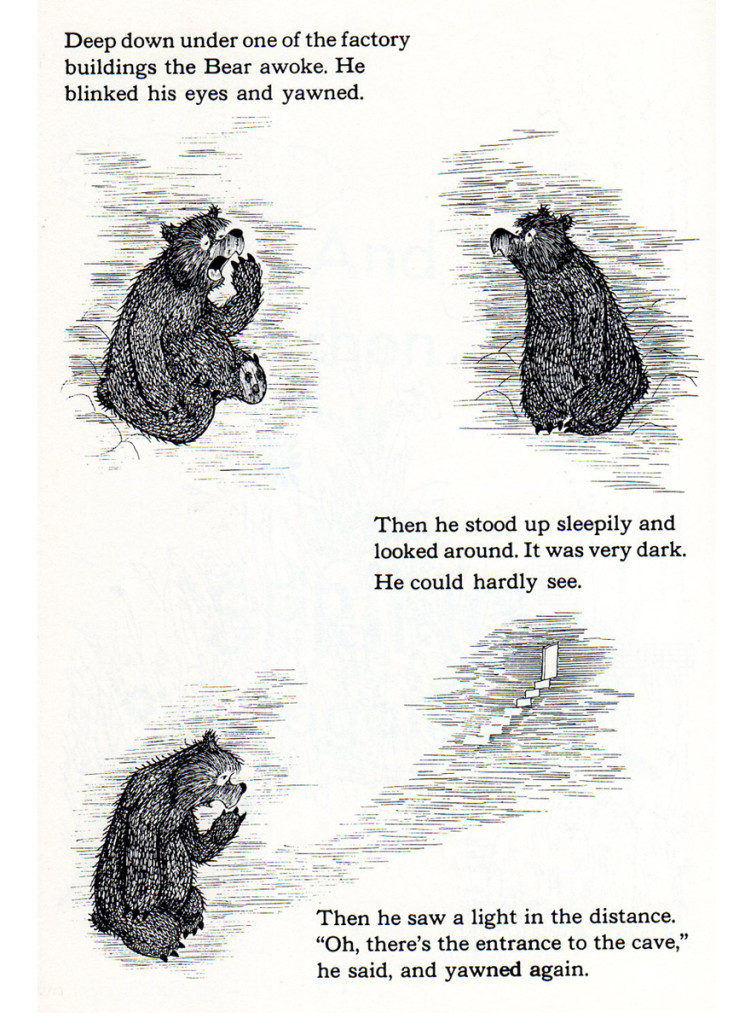

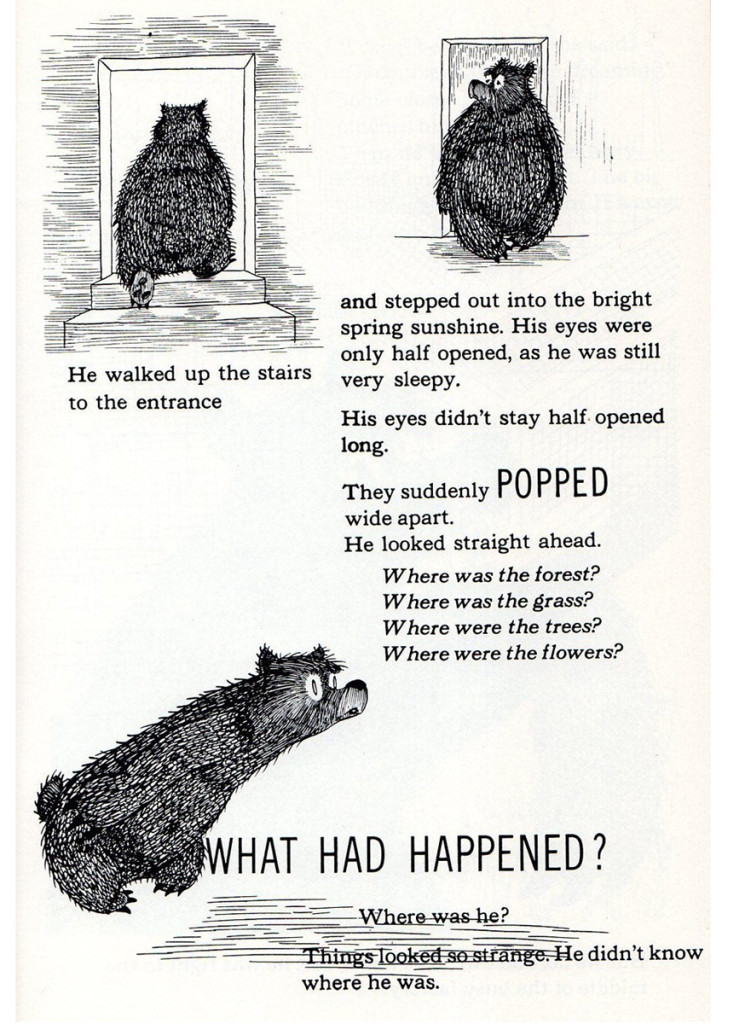

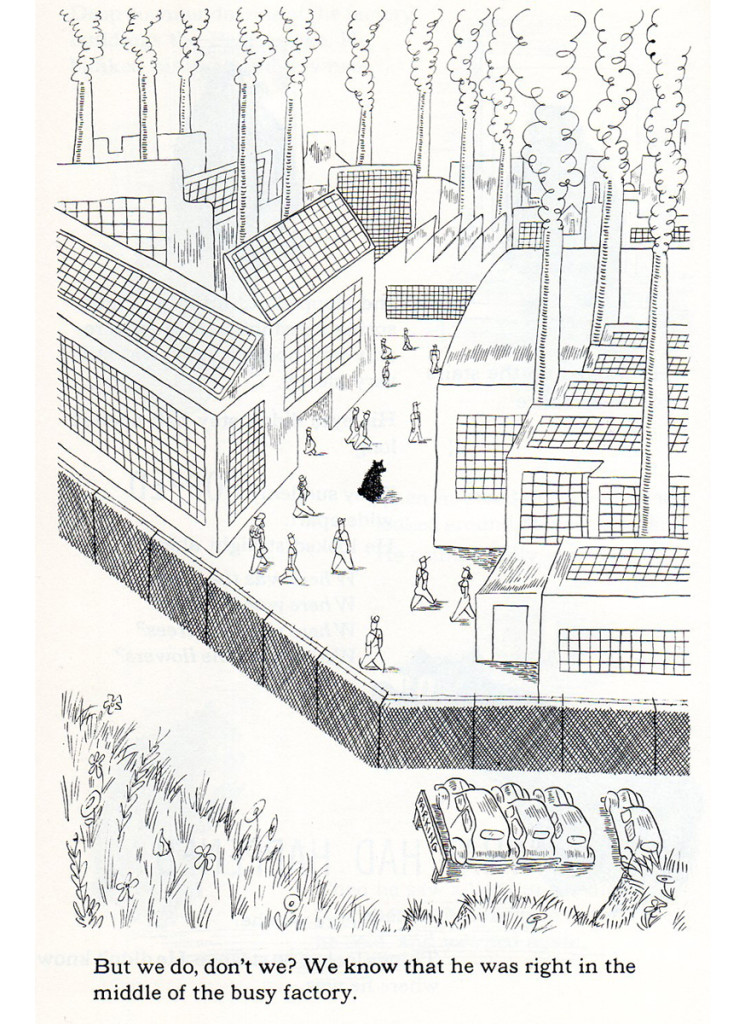

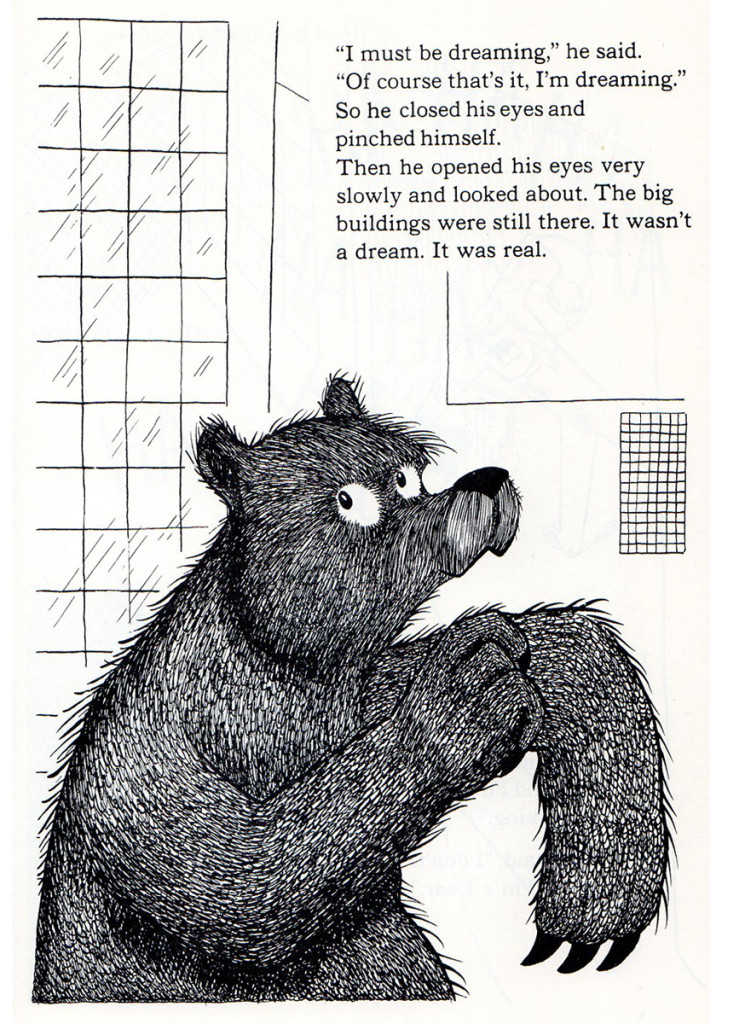

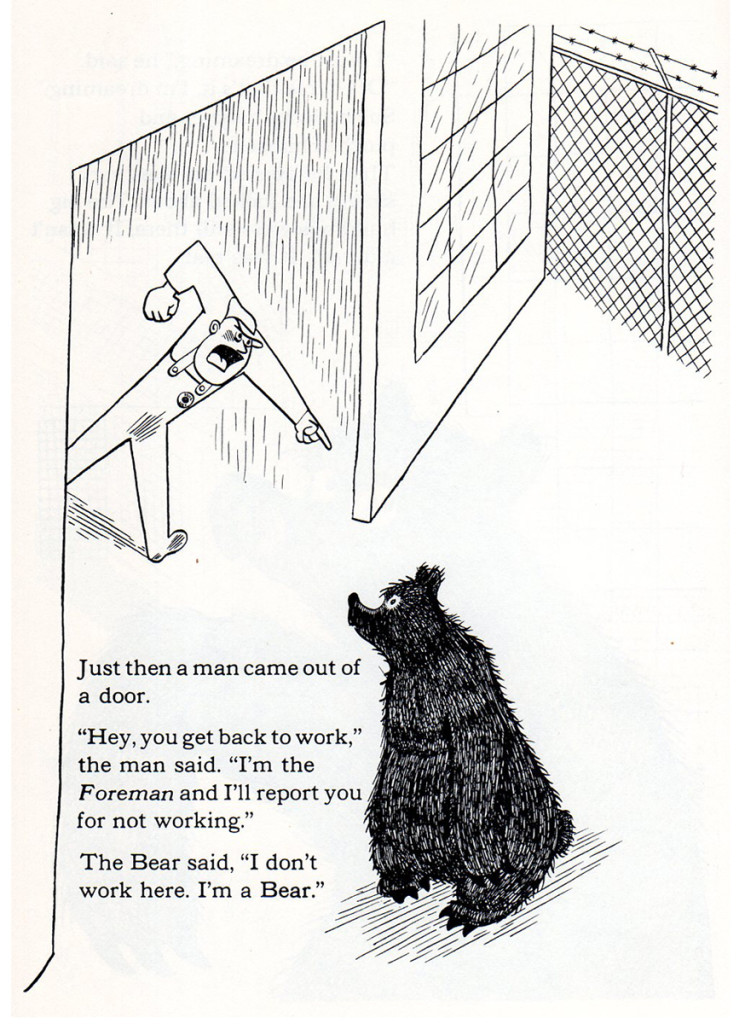

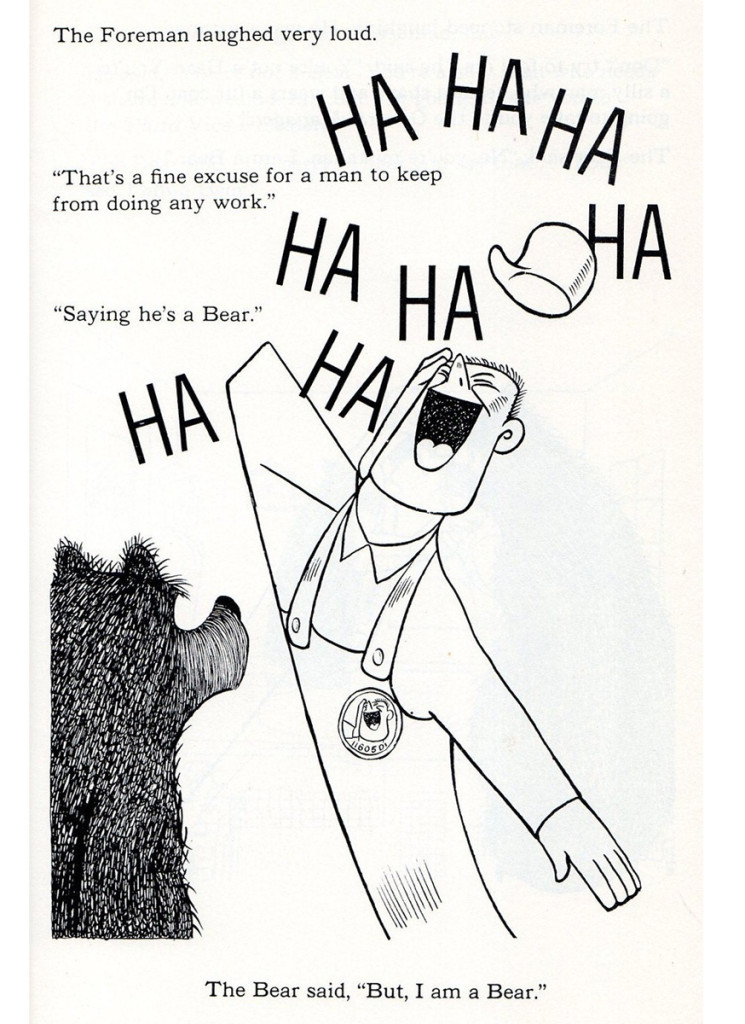

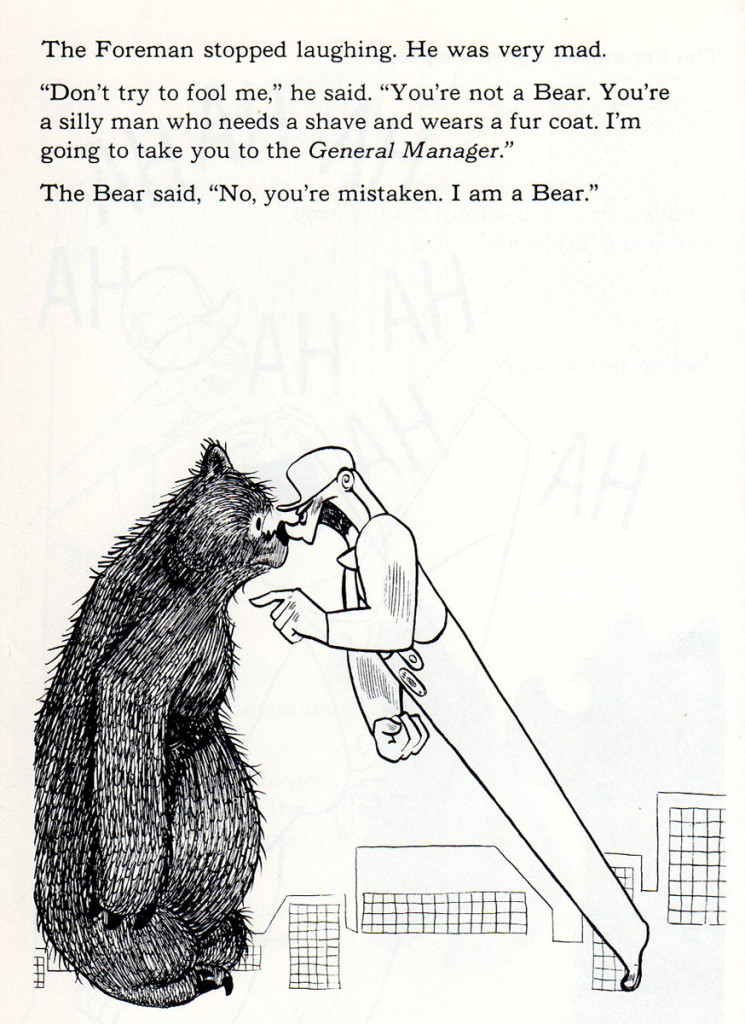

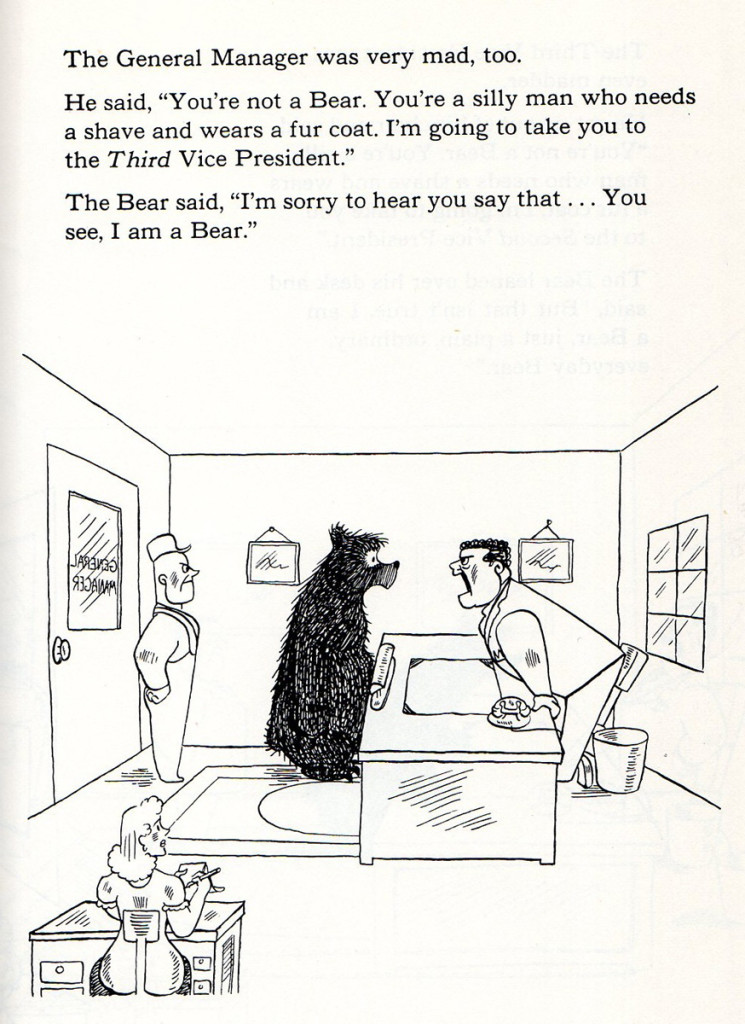

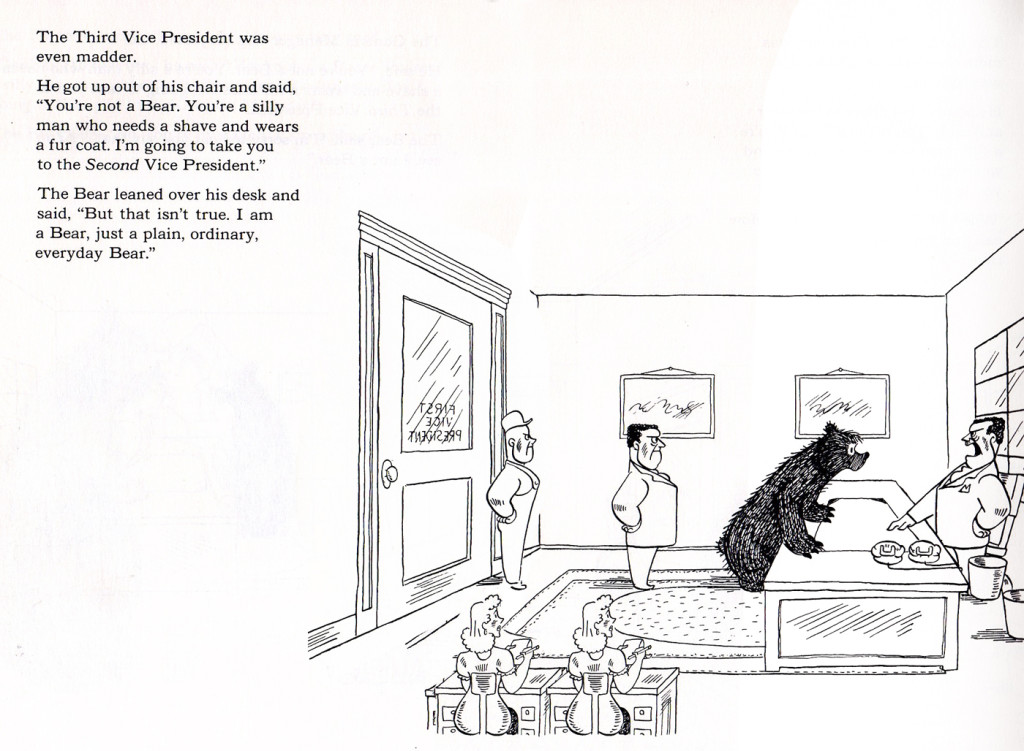

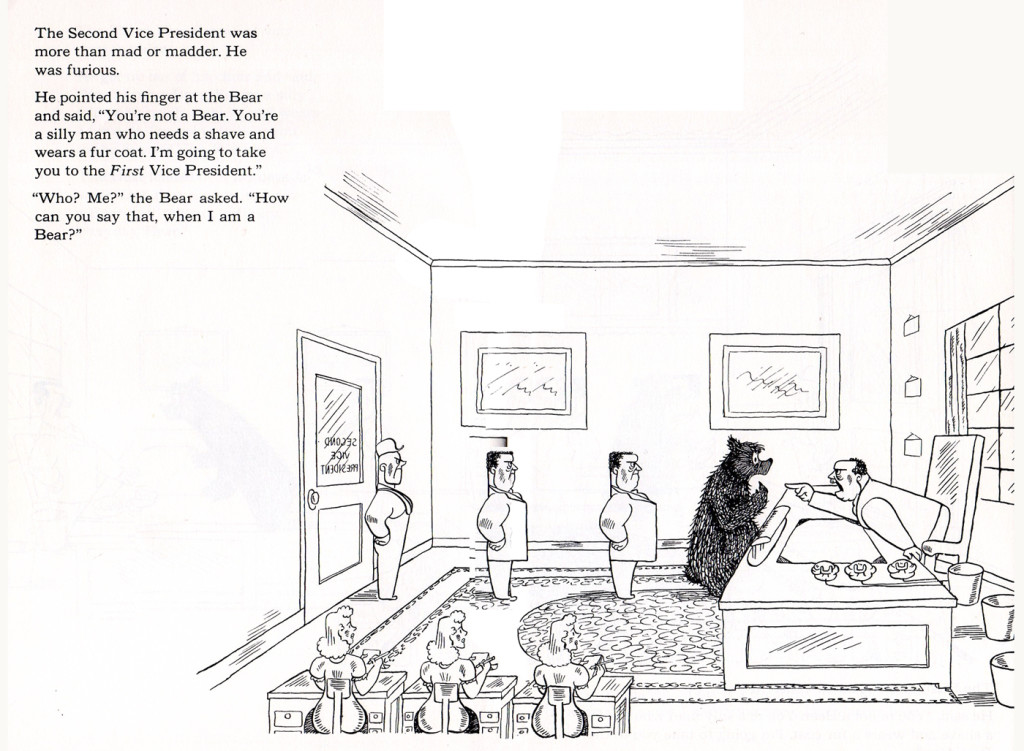

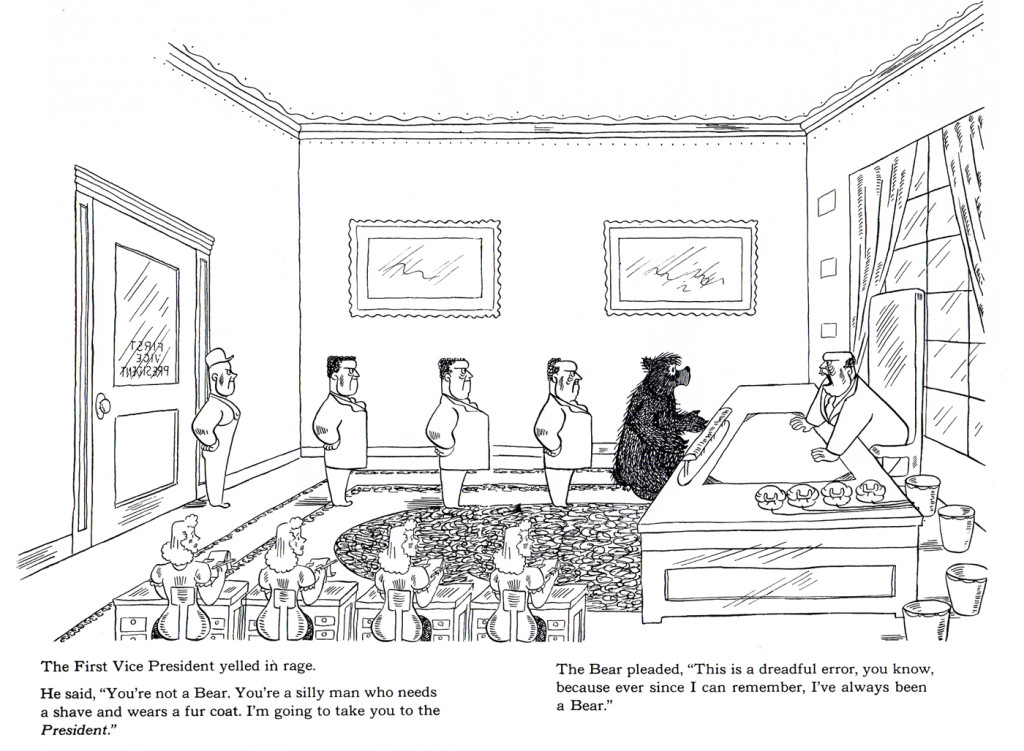

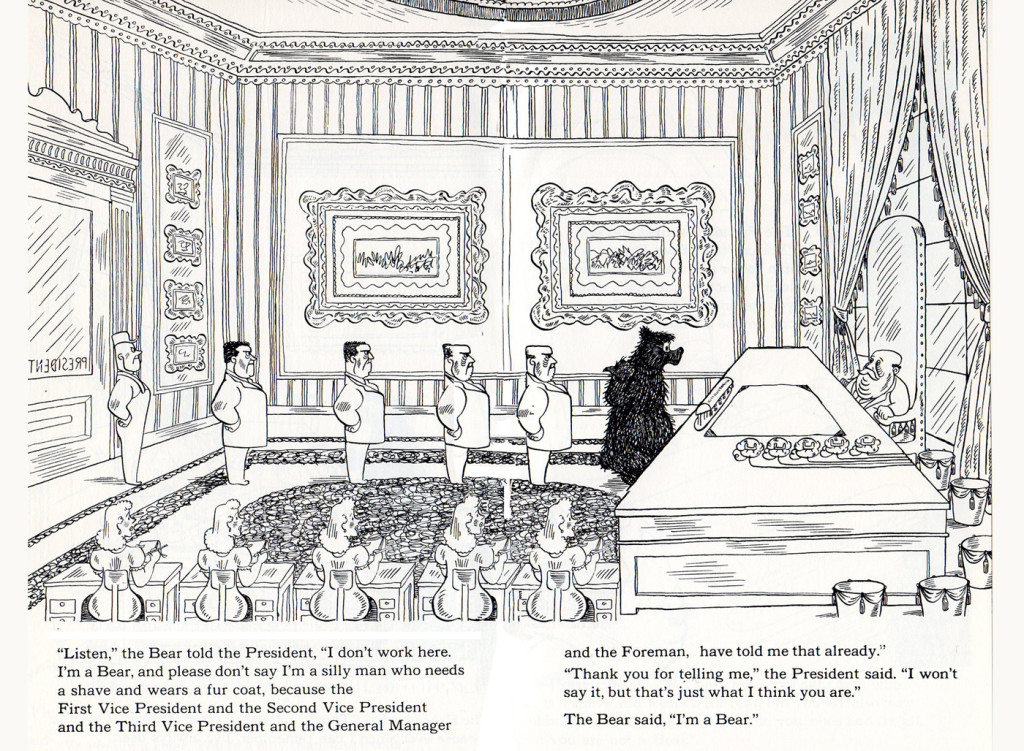

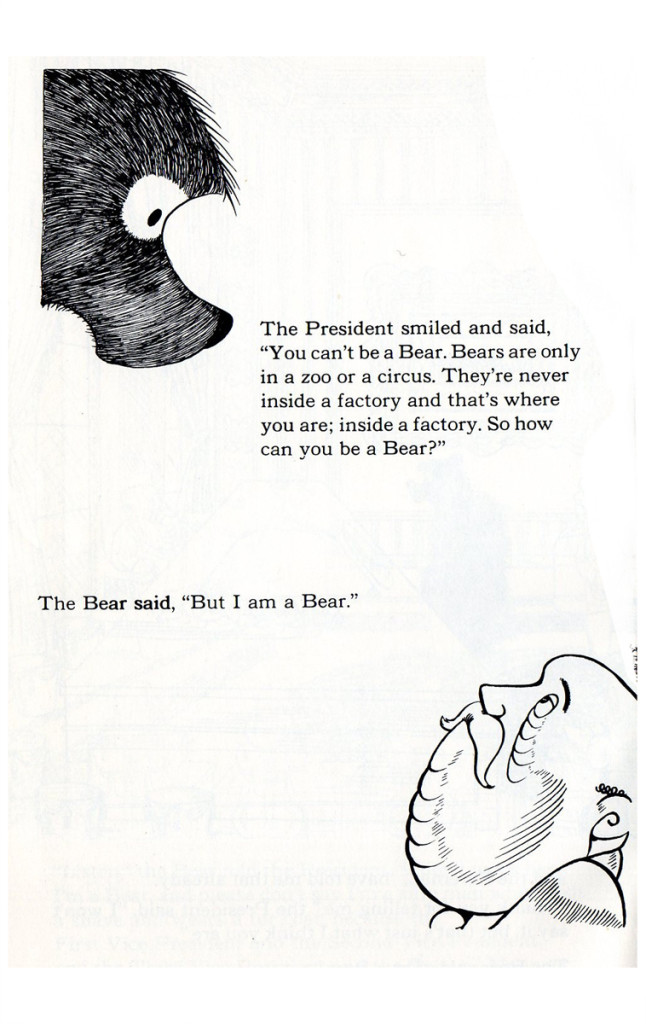

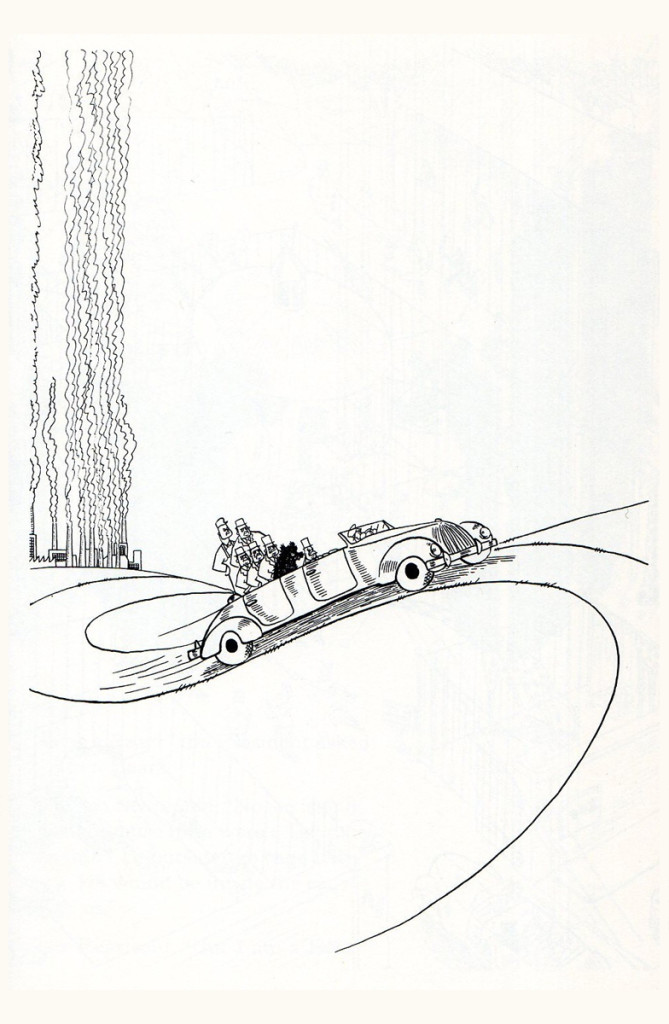

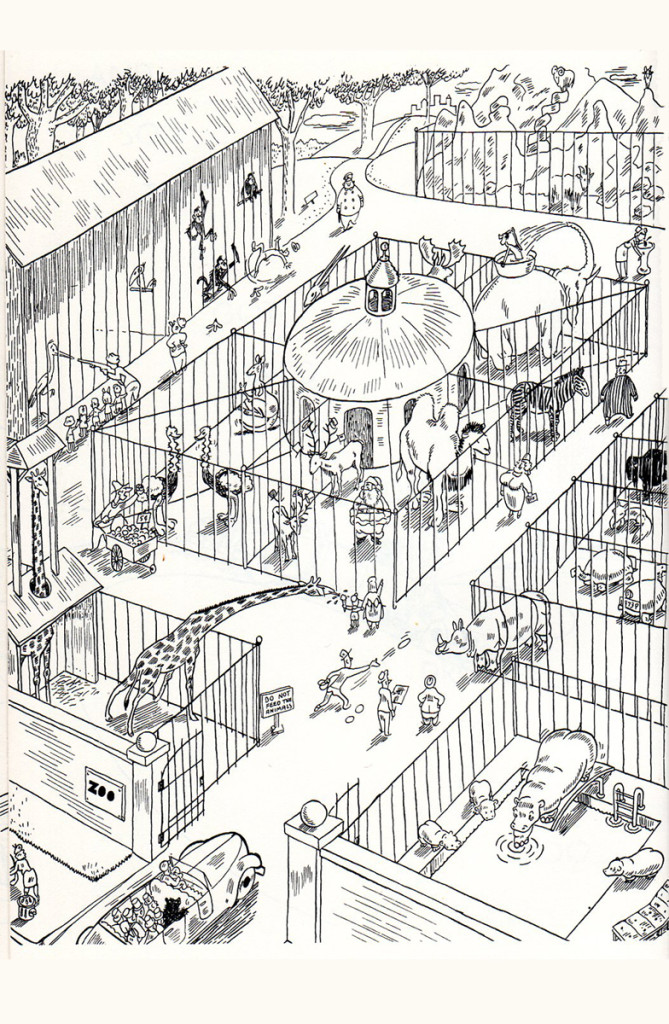

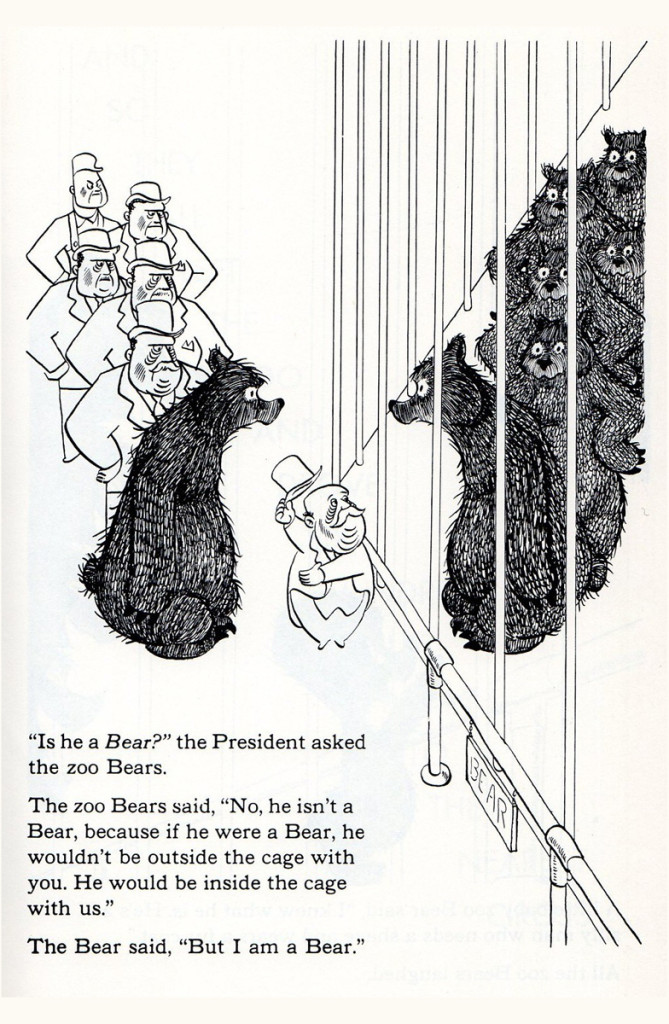

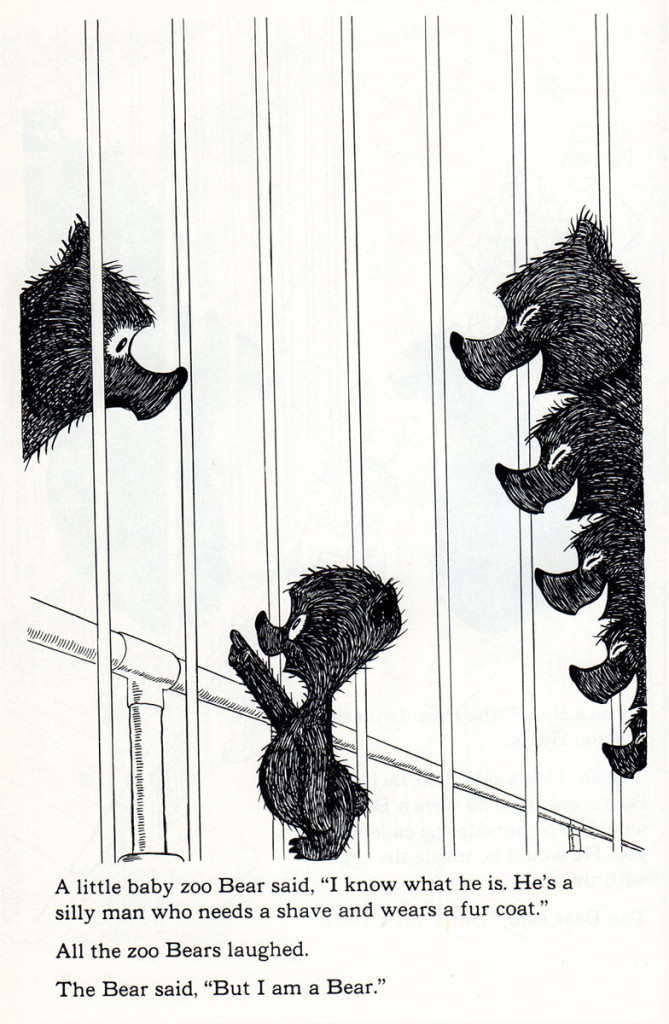

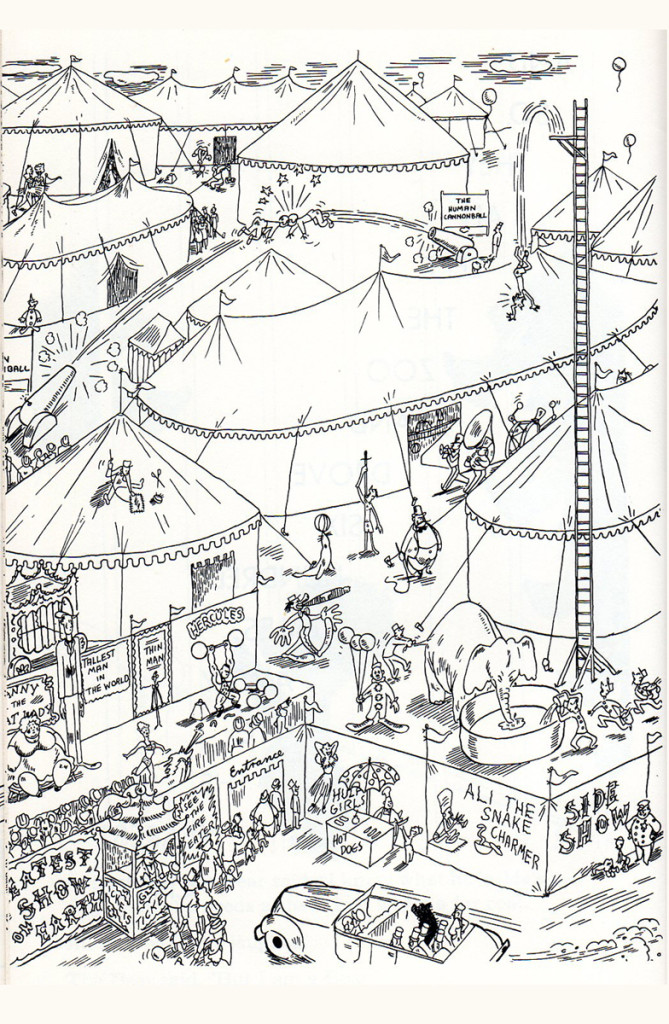

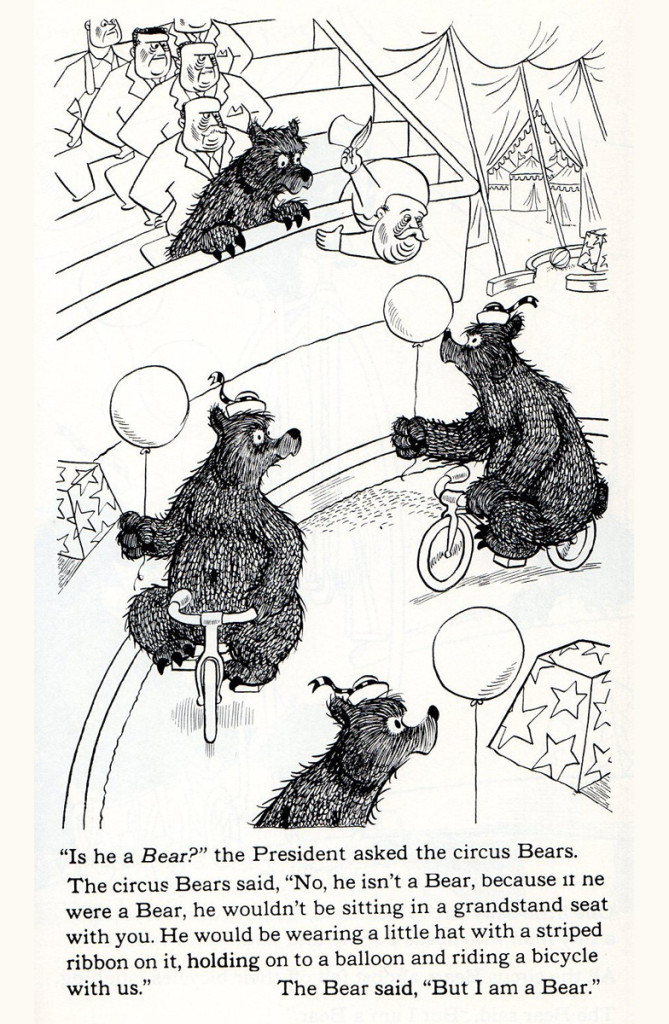

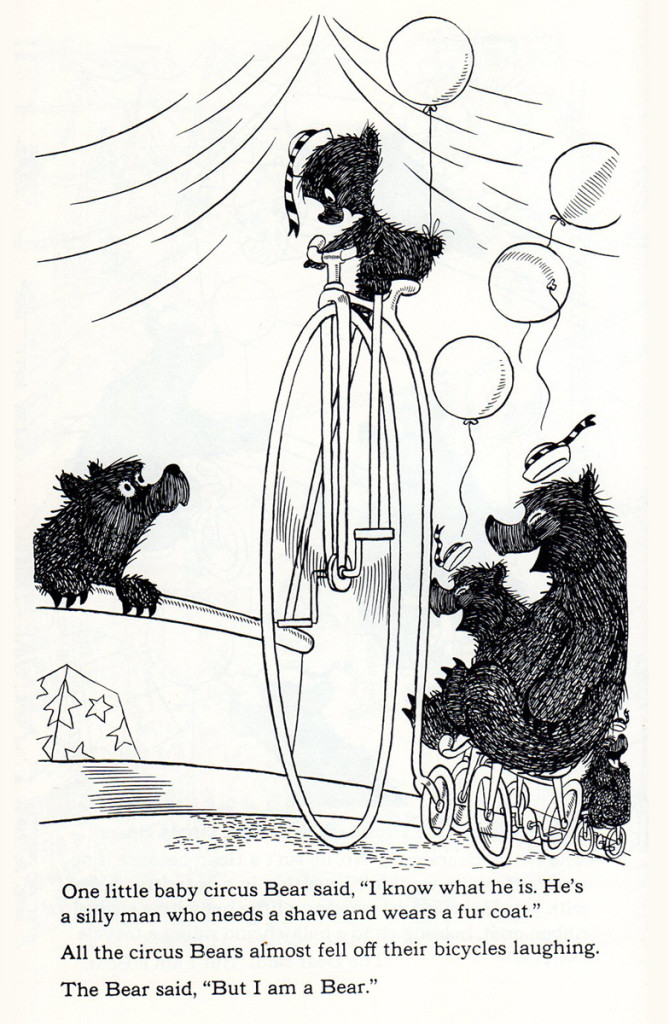

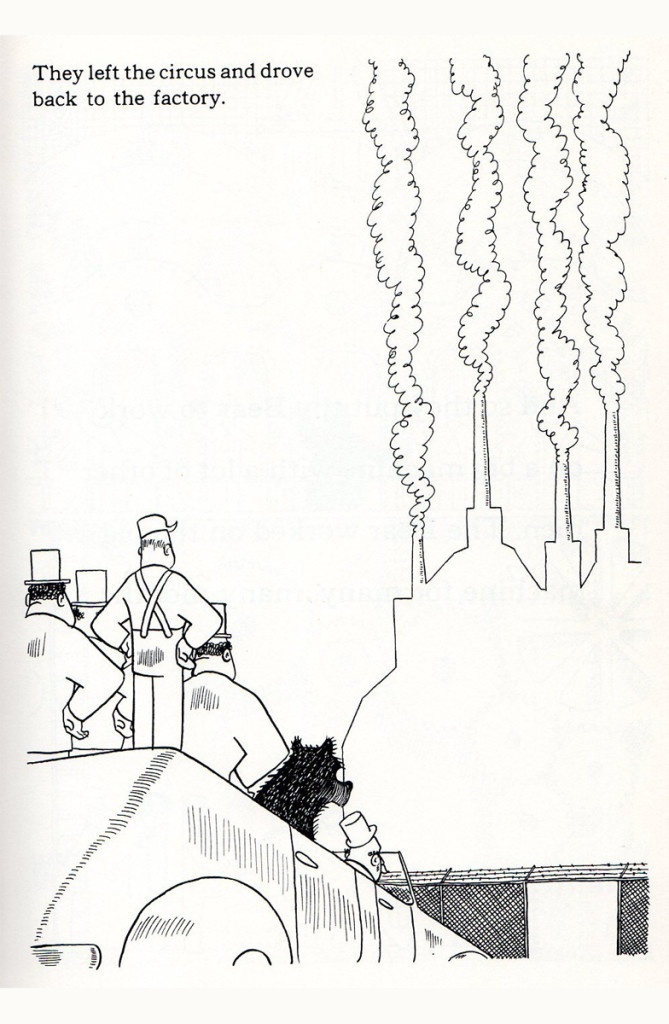

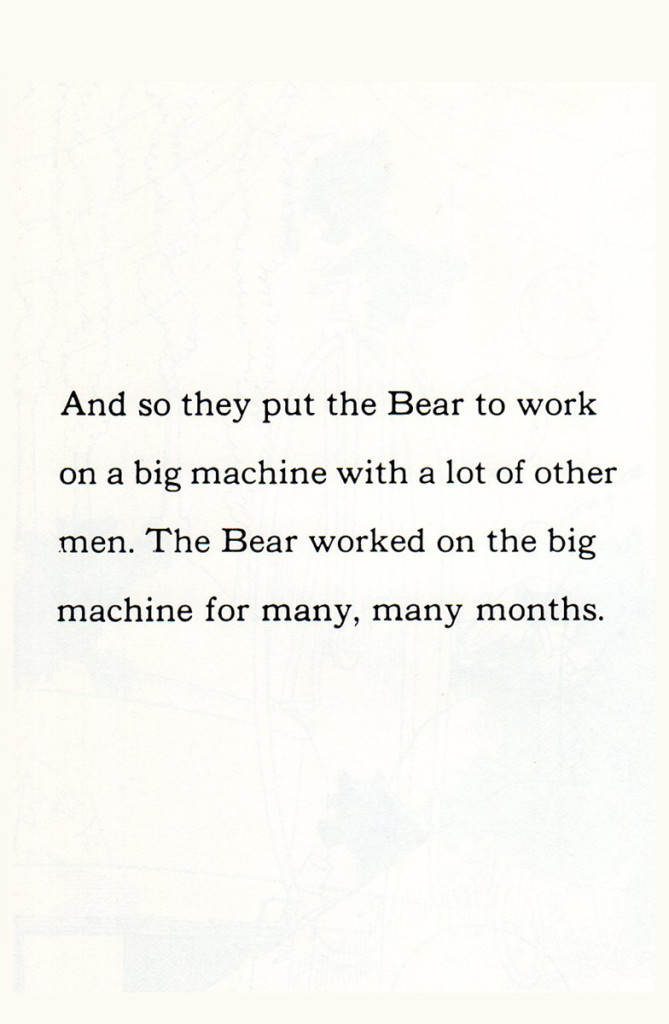

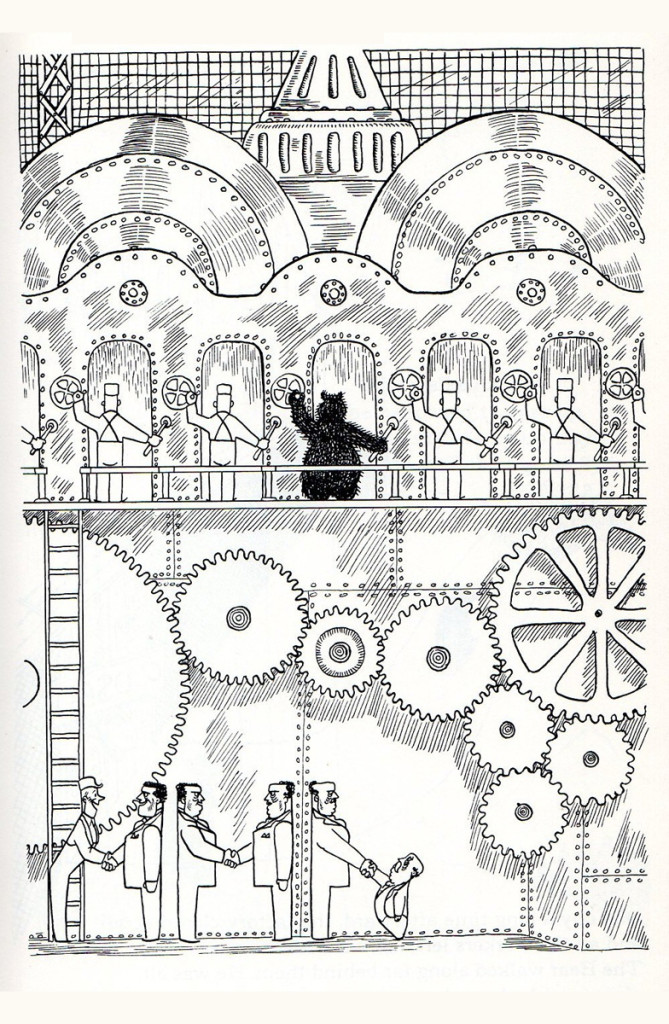

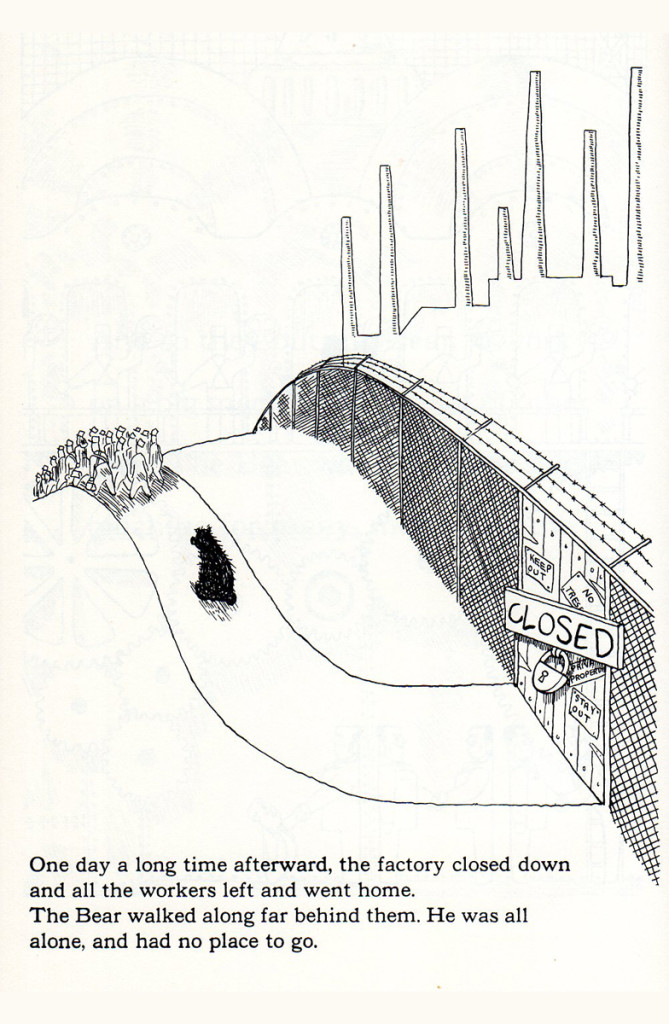

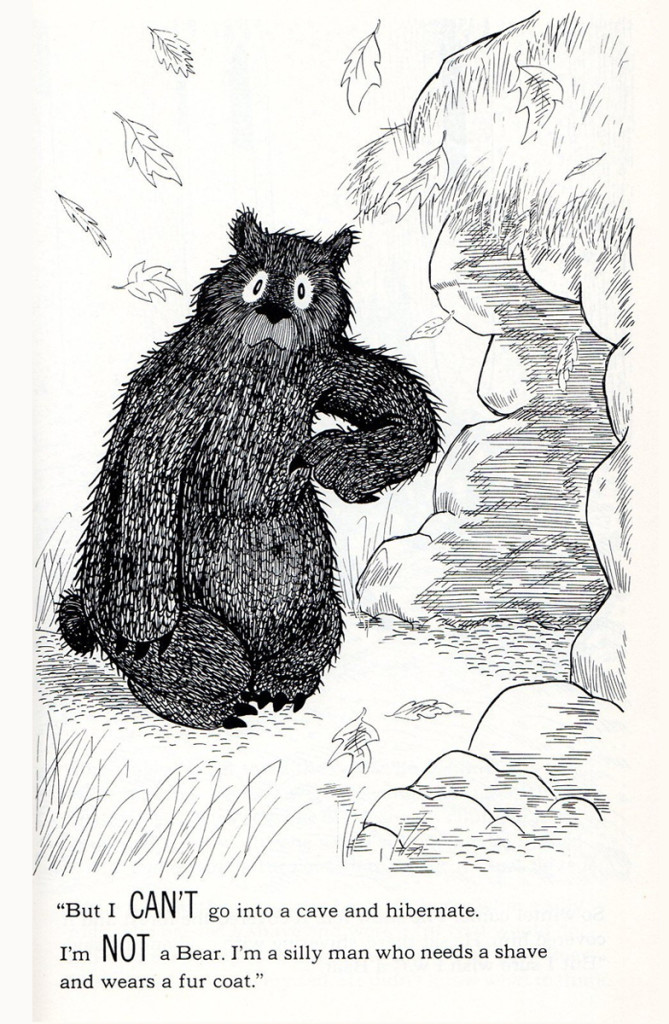

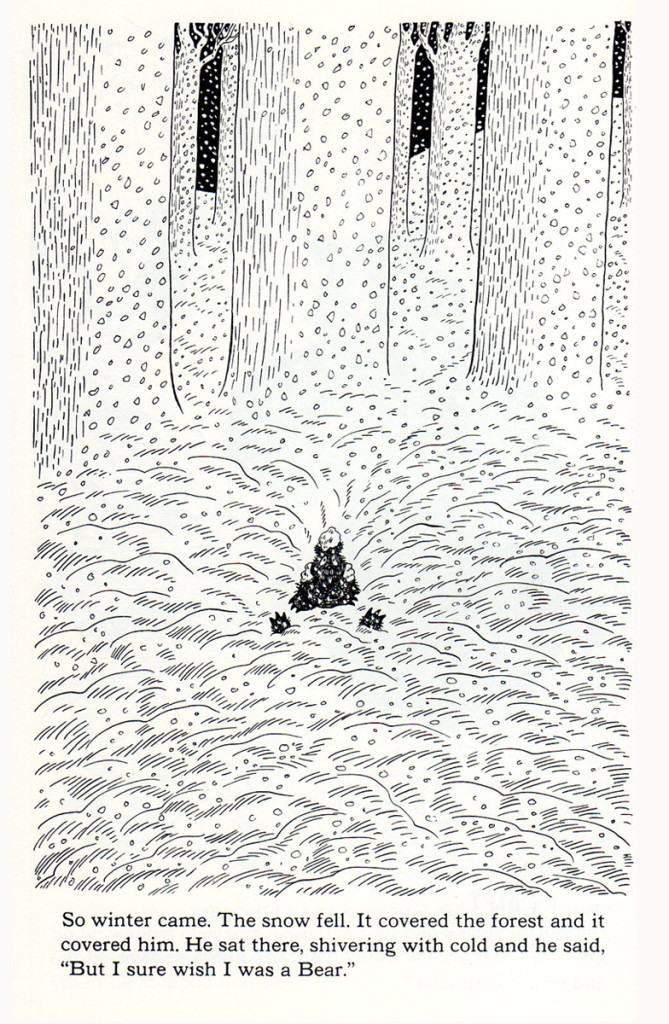

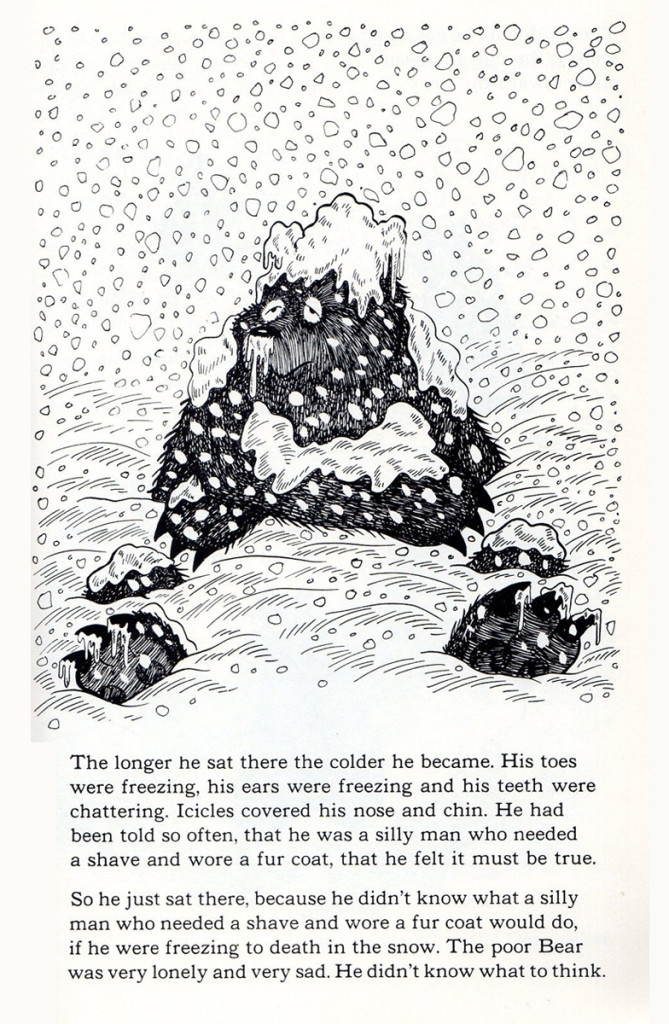

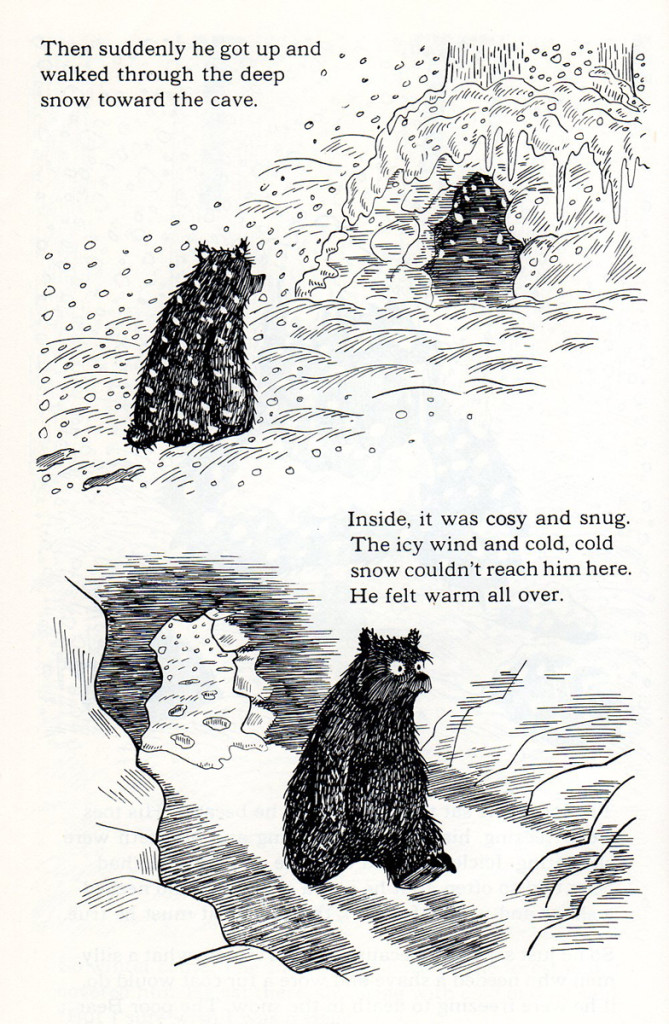

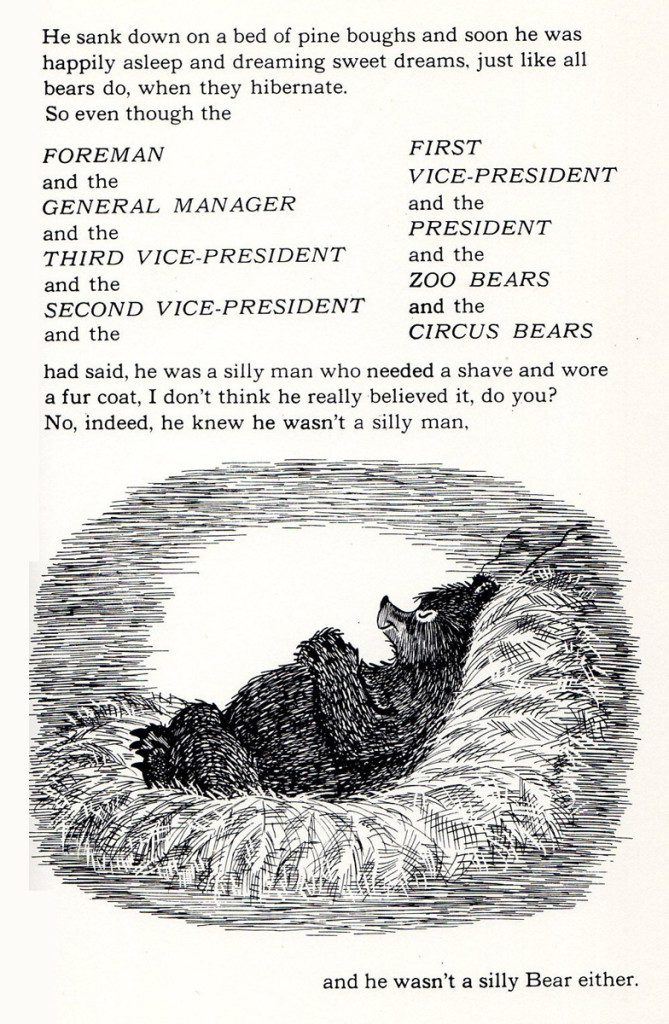

- I have always been aware of Frank Tashlin‘s book, “The Bear That Wasn’t,” and I have never liked it. Well, Bill Peckmann sent me a copy of scans of the book, and I realize that I’ve disliked it because of CHuck Jones’ insipid animated adaptation. When you look at the actual book and the beautiful illustrations, you realize how sensitive the material is and how beautifully handled it is. The illustrations are, in a word, great.

I’m so pleased Bill sent these scns to me, and I almost disgrace the post by ending with the Jones cartoon. It’s no wonder Tashlin disliked Chuck’s work. Take a look. First a lead-in by Bill:

-

Grim Natwick was an admirer of Frank Tashlin, and all I can say to that is… it takes a renaissance man to know a renaissance man.

Here is the 1962 Dover reprint of Frank Tashlin’s 1946 book, “The Bear That Wasn’t”

Enjoy!

1

1The original cover

This was a publisher’s ad to booksellers

that came out when the book did.

Here’s the Chuck Jones cartoon as released by MGM.

It’s got problems that weren’t in the book.

They mostly come from Chuck Jones.

Animation &Animation Artifacts &Commentary 01 May 2013 06:52 am

Piels Bros Commercial Animation Dwngs

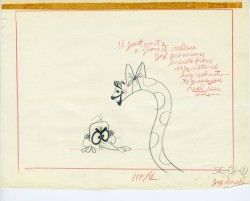

Here’s the last of the three posts I’ve been able to cull from the drawings left behind in Vince Cafarelli‘s things. The 60 second spot was animated by Lu Guarnier and clean-up and assisting was by Vinnie.

Within this post there are drawings from two separate scenes. If you look at the storyboard (I’d posted the entire board in another post, but I’ve pulled the particular frames from the board to show again here), you can see what it is the characters are saying. I don’t have all the drawings for these two scenes; just those I’ve posted.

I’m also going to use these drawings of Lu’s to write about his style of animation. I was taught from the start that this was completely done in an incorrect way. I don’t mean to say something negative about a good animator, but it is a lesson that should be learned for those who are going through the journeyman system of animation.

Right from the get-go I had some difficulty assisting Lu’s scenes. He started in the old days (early-mid Thirties) at Warner Bros, in Clampett’s unit, and moved from there to the Signal Corps (Army); then to New York working at a few studios before landing at UPA’s commercial studio. After that, he free lanced most of his career, as had so many of the other New York animators. They’d work for six months to a year at one studio then would move on to another.

Right from the get-go I had some difficulty assisting Lu’s scenes. He started in the old days (early-mid Thirties) at Warner Bros, in Clampett’s unit, and moved from there to the Signal Corps (Army); then to New York working at a few studios before landing at UPA’s commercial studio. After that, he free lanced most of his career, as had so many of the other New York animators. They’d work for six months to a year at one studio then would move on to another.

I suspect the problems in Lu’s animation all generated from the training he’d gotten at WB. Lu worked in a very rough style. No problem there. An animator should work rough. These drawings posted aren’t particularly rough, but in his later years (when I knew him) there was hardly a line you could aim for in doing the clean-up. His style was done in small sketchy dashes that molded the character. Rarely was it on model, and always it was done with a dark, soft leaded pencil. There were others who worked rougher, Jack Schnerk was one, but Lu’s drawing was usually harder to clean up.

There was a rule that came out of the Disney studio, and, as both an animator and an assistant, I’ve followed it closely. When doing the breakdown charts (those ladders to the right of the drawing) all inbetween positions had to be exactly half way between drawing “A” and drawing “B”. If the animation called for it to be 1/4 of the way, you’d indicate that half-way mark then indicate your 1/4. If a drawing had to be closer or farther away – say 1/3 or 1/5th of the way – the animator should do it himself. This, as I learned it, was the law of the land. However, Lu would rarely adhere to it, and an assistant’s work became more complicated. The work was too easily hurt by a not-great inbetweener. I’ll point out an example of Lu’s breaking this rule as we come to it).

B35

B35

These ladders are done correctly, per the Disney system.

#34 is half way between #32 & #35;

#33 is half way between #32 & #34.

#36 is half way between #35 & #38;

#37 (the 1/4 mark) is half way between #36 & #38.

However, Grim Natwick told me

- demanded of me –

that all ladders should appear on the lower numbered drawing.

The ladder here should be on drawing #32 for all art

going into the upcoming extreme, #38.

Lu never followed this rule, which means the

assistant generally had to search for the chart.

The Second scene

B108

B108

This ladder is typical of Lu’s animation.

It would seem that #106 is 1/3 of the way between #108

and #105 is half way between #106 and #109.

and it also looks like #107 is 2/3 of the way between #108 and #109.

Because the numbers come on the last of the extremes, here,

more confusion is allowed to settle in.

H9

H9

Again, the ladder appears on the later extreme. The assistant

shouldn’t have to go looking for it. The ladder should be on

the first drawing involved in the breakdown.

Again, the breakdown drawings are on 1/3′s, and

the inbetweens are 1/2′s of that. It makes it harder on the

people following up on the clean-up & inbetweens.

I don’t know if this style of Lu’s was a product of where he learned to animate or not. Jack Schnerk, a comparable animator – whose work I loved (even though he had a rougher, harder to clean up drawing style) – always broke his timing in halves and halves again. There were times when his animation went to one’s and he did most of all the drawings. I assumed he had an unusual timing, and he didn’t want to burden the Assistant with his schema. He also always carried the breakdown charts on the earlier numbered drawing – per Grim Natwick’s comment. In some way I felt that Lu was rushed to get on with the scene, and whatever method he used would be to get him there more quickly. (It was the assisting that was slowed down.) This may have been a product of his attempts to devise some type of improvisation in the animation. Lu’s work, on screen, was usually excellent, so he didn’t much hurt anything in his method.

It might also have been his method of trying to put SNAP into the animation. This was a WB trait from the mid-late Thirties. It was certainly in Lu’s animation. No doubt a hold-over from Clampett’s early days of directing.

The final thing to note is that Lu usually worked on Top Pegs. Animating on Top Pegs makes it impossible to “roll” the drawings and check on the movement of more than 3 drawings. You can only “flip” the three, checking the one inbetween, but it didn’t give you a good indication of the flow of the animation. This is obviously necessary in animating on paper. It also made it difficult for the cameraman as well as those following behind the animator. If there were a held overlay, this would have to be on bottom pegs since the animation is on top pegs. That requires extra movement of the expensive cameraman to change all the animation cels after lifting the bottom pegged overlay. It also risks the possible jiggling of the overlay as it’s continually moved for the animating cels.

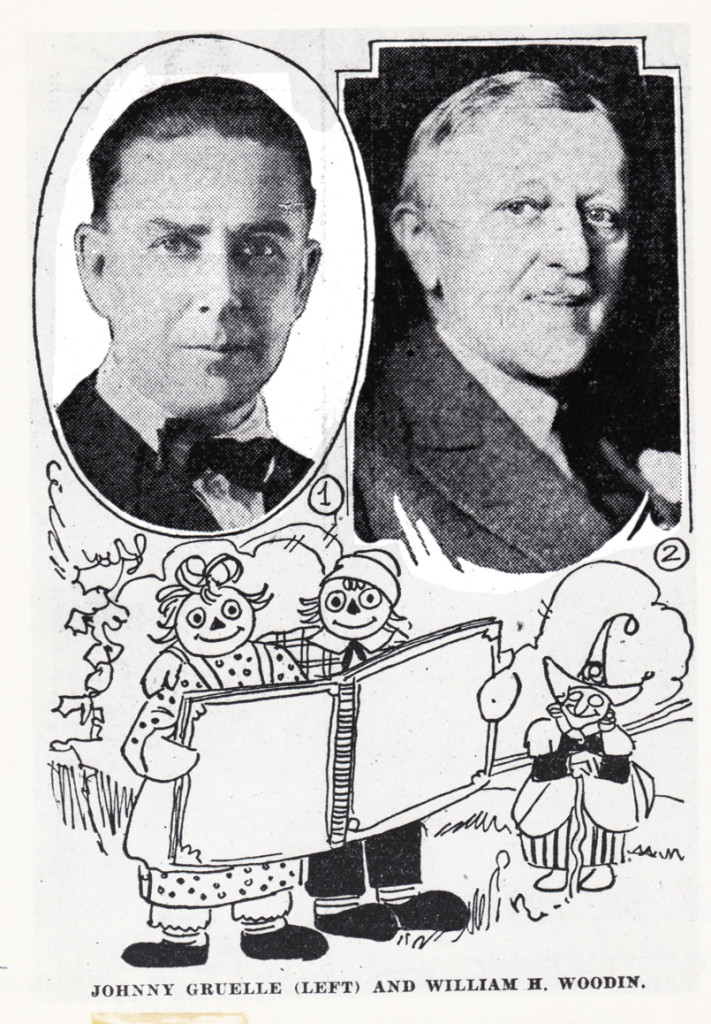

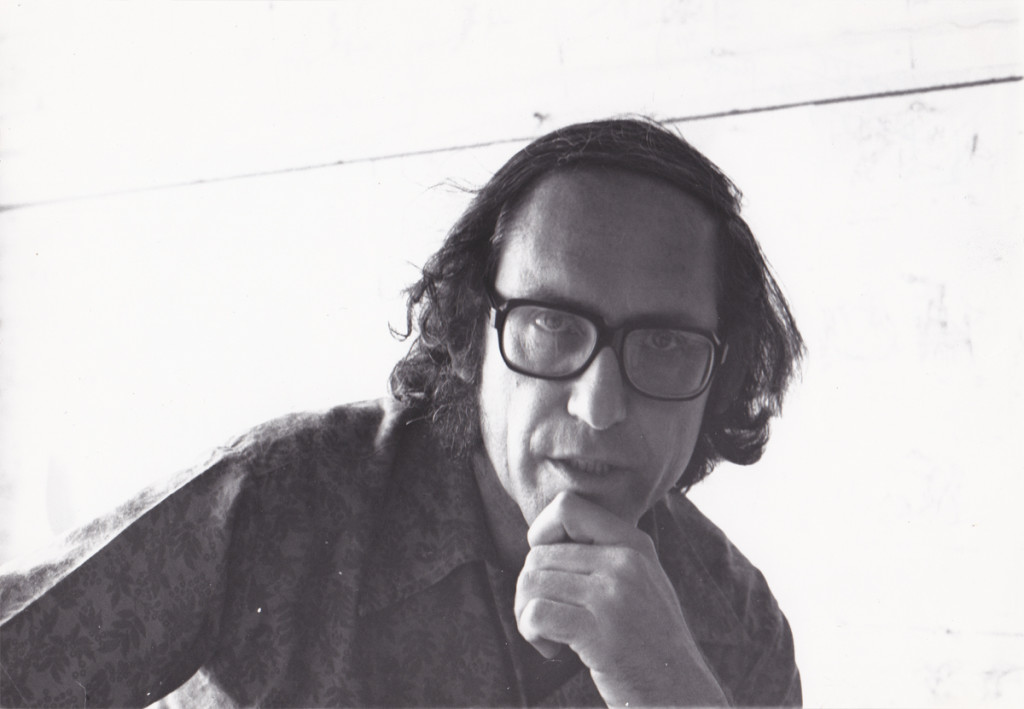

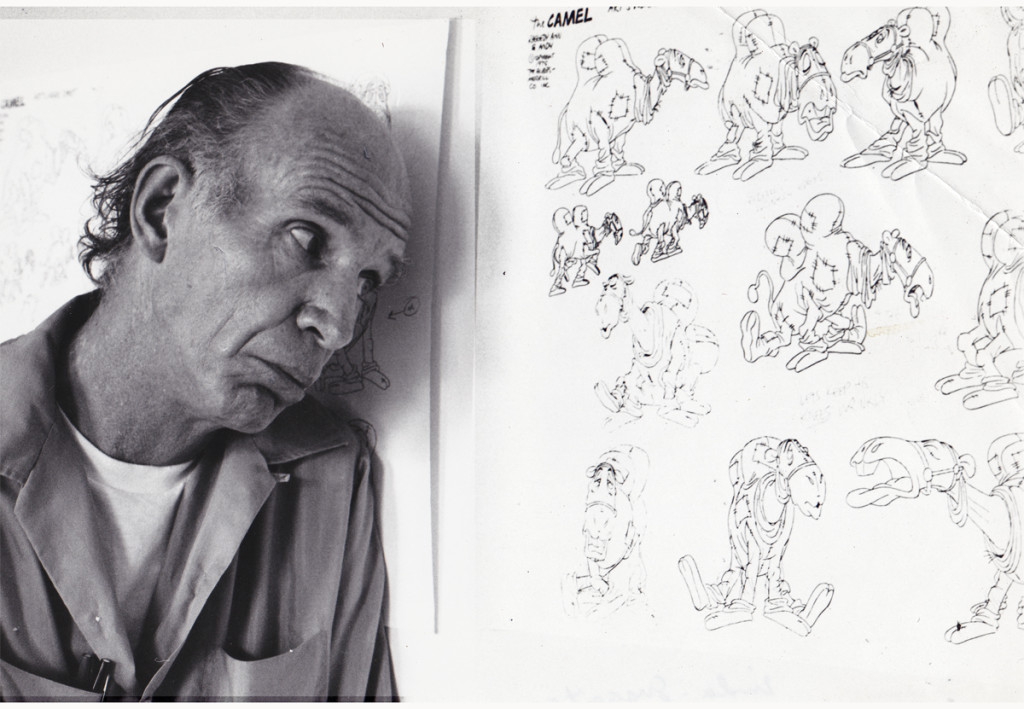

Books &Commentary &John Canemaker &Photos 28 Apr 2013 05:55 am

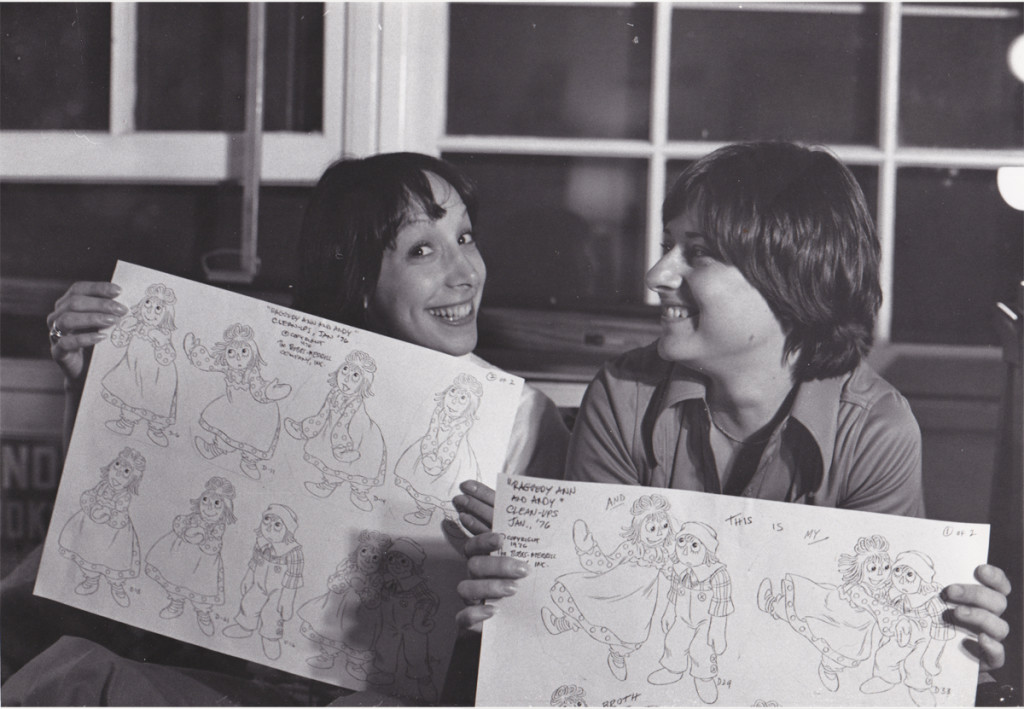

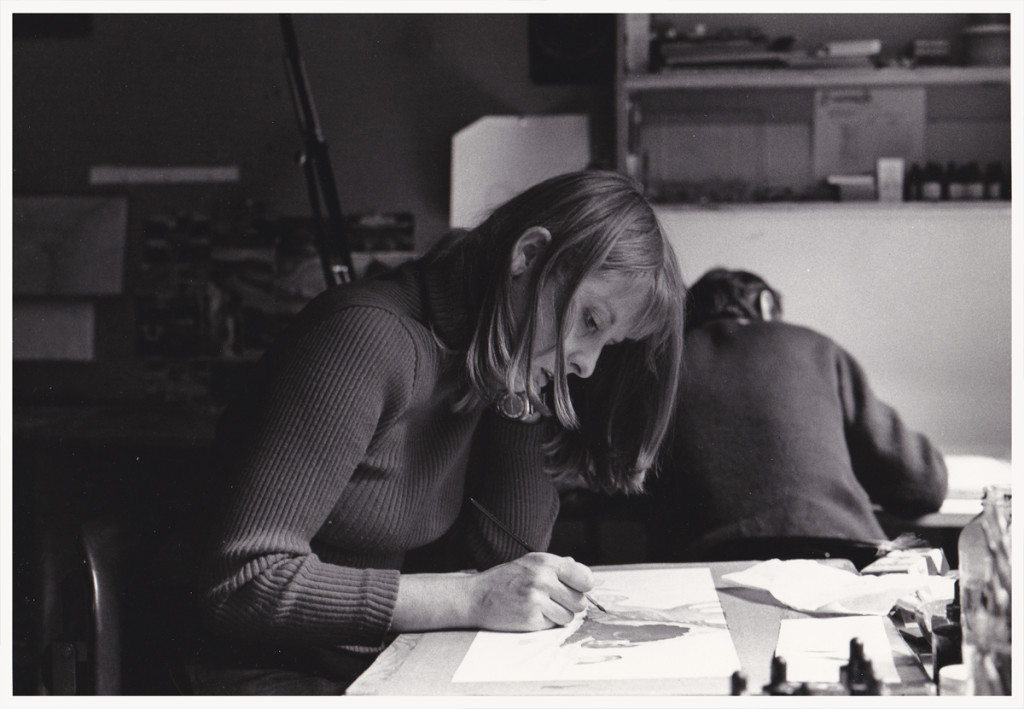

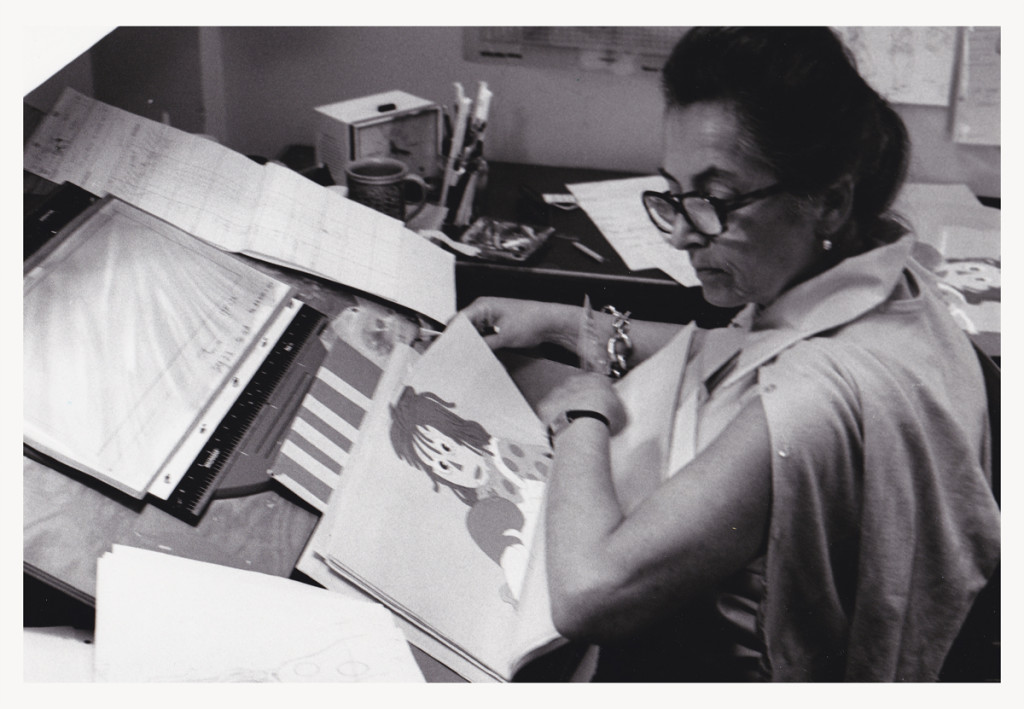

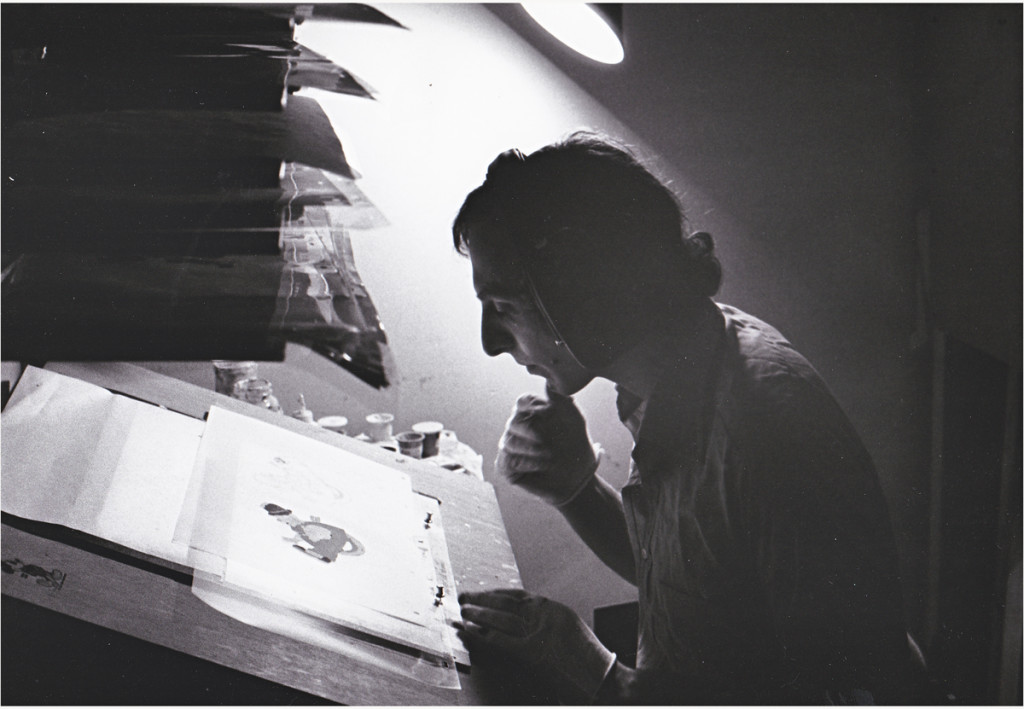

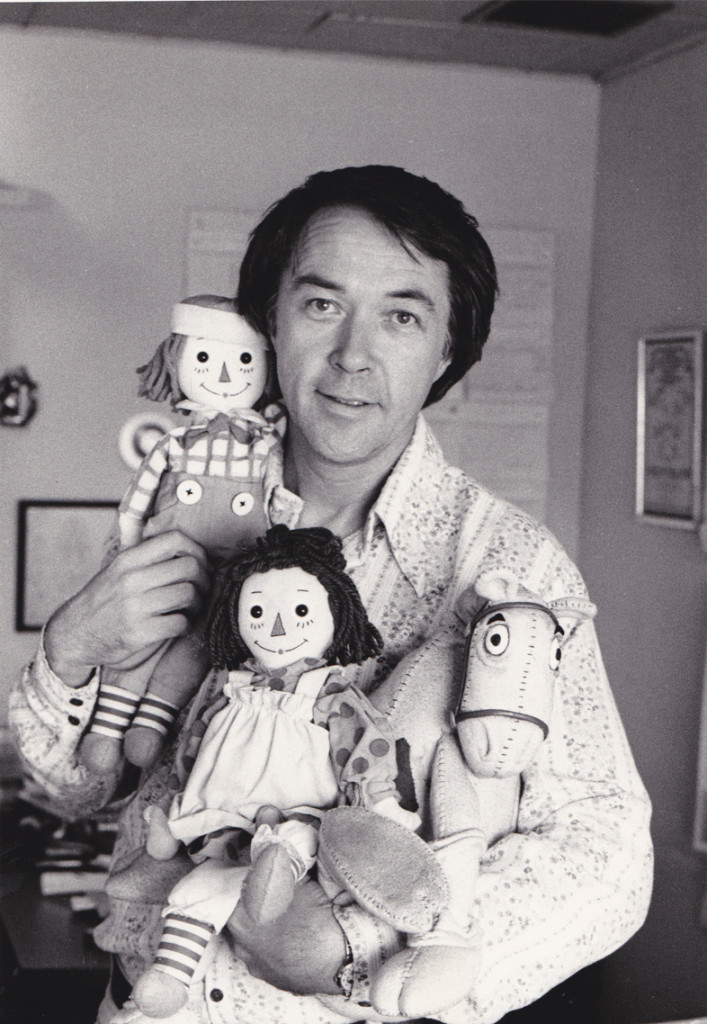

Raggedy Ann Photos

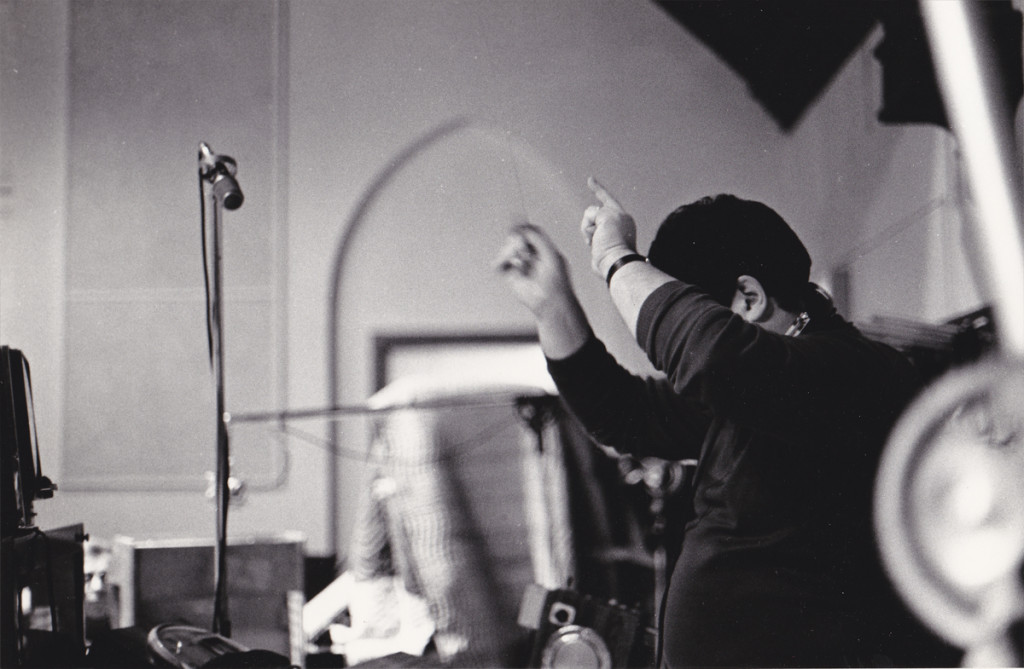

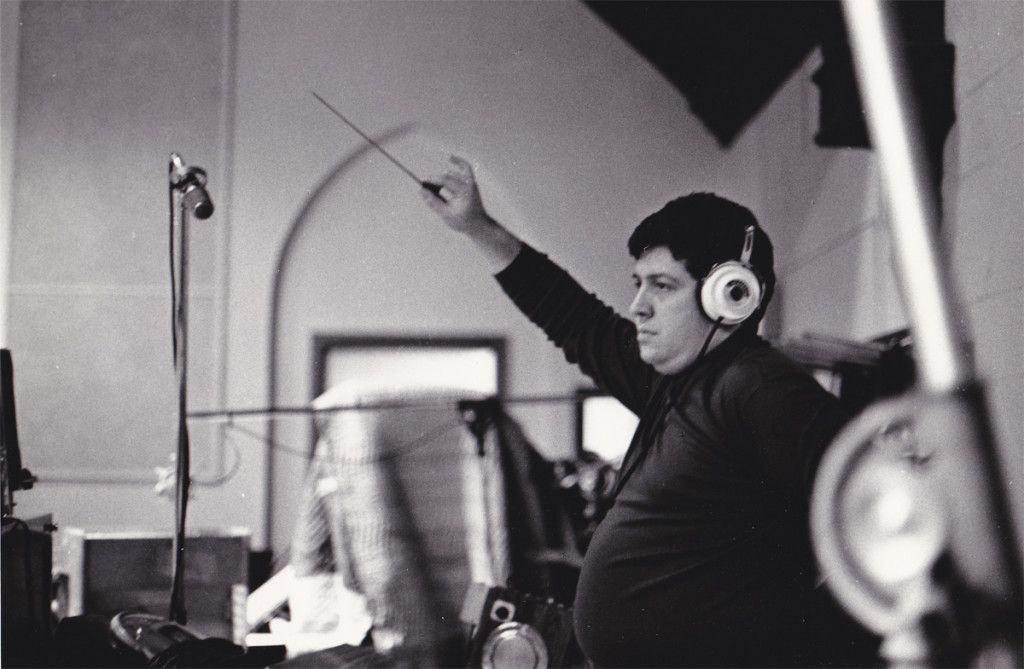

- John Canemaker recently loaned me a stash of photos of the Raggedy Ann crew. These were pictures that were used in his book on the “making of”. It was a better book than movie (as they often are). There are also some photos that didn’t make it to the book. John Canemaker shot all the photos, himself and all copyright belongs to him.

I thought I’d post the pictures and add some comments that pop off the top of my head. Hopefully, a couple of interesting stories will show up in my memories.

There are enough photos that it’ll probably take about three posts to get them all in. The next two Sundays are booked, I’d guess.

1

1Johnny Gruelle (artist, writer) and William H. Woodin (song writer)

Dec.28, 1930 Indianapolis Star – “Raggedy Ann’s Sunny Songs”

This was apparently a theatrical piece Johnny Gruelle

put together with his very successful characters.

2

2

It all started with Joe Raposo, the composer of “Bein’ Green”

and many other hit Sesame Street songs. He wrote a musical for “Raggedy Ann

and Andy” and was made to see that it would make a wonderful animated musical.

3

3

He wrote a lot of songs for the slim script and they prerecorded

the songs for the animation. We lived with a soundtrack of about

a dozen musicians playing this very nice score to the delicate voices

that sang the tuneful pieces.

4

4

We heard this at least once a week as the animatic/story reel

grew into a full animated feature shot completely in Cinemascope.

5

5

When the final film was released, that 12 person orchestra

became 101 strings and a big over-polished sound track.

No matter where you went the music was there and in the way.

It was too big, and the movie was too small. It was bad.

The track was incredibly amateurish. The composer had too much control.

6

6

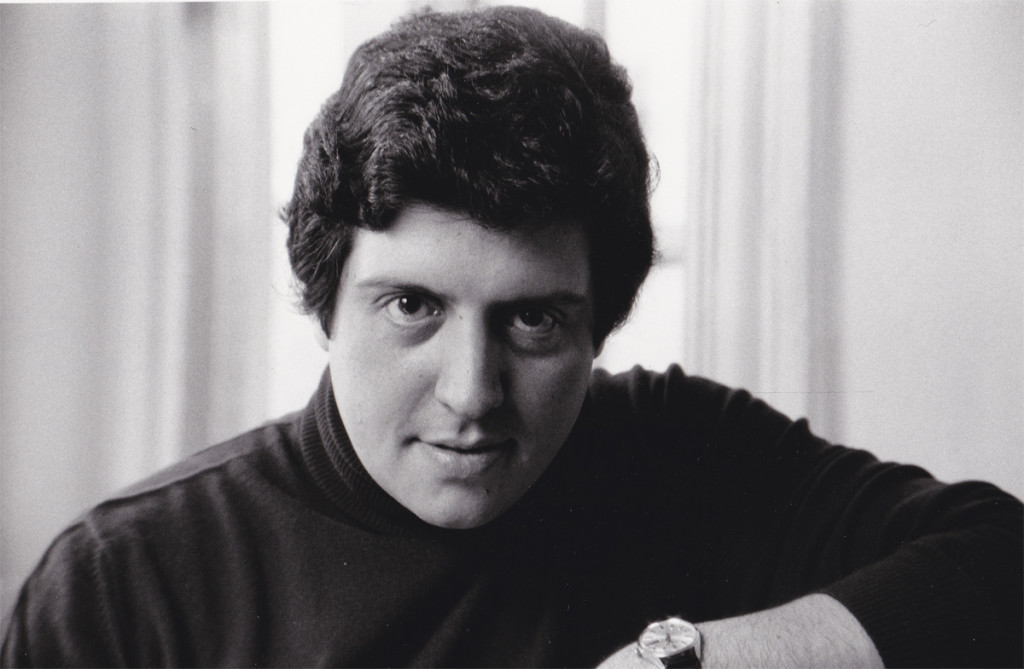

This was Richard Horner. He was one of the two producers of the film.

Stanley Sills (a Broadway producer and Beverly’s brother) was the

other producer who didn’t know what he was doing.

They represented Bobbs-Merrill who owned the property.

I really liked Mr. Horner. We met again a number of years later

when Raggedy Ann was distantly behind us. I’d offered to take Tissa to church,

one Easter Sunday; Richard Horner and wife were there. He asked to meet with me.

He sought advice on some videos of artists and their work that he was producing,

and hoped I could offer my help in leading him to some distributors.

7

7

This is one of the dolls in the play room,

Susie Pincushion. She was charming.

8

8

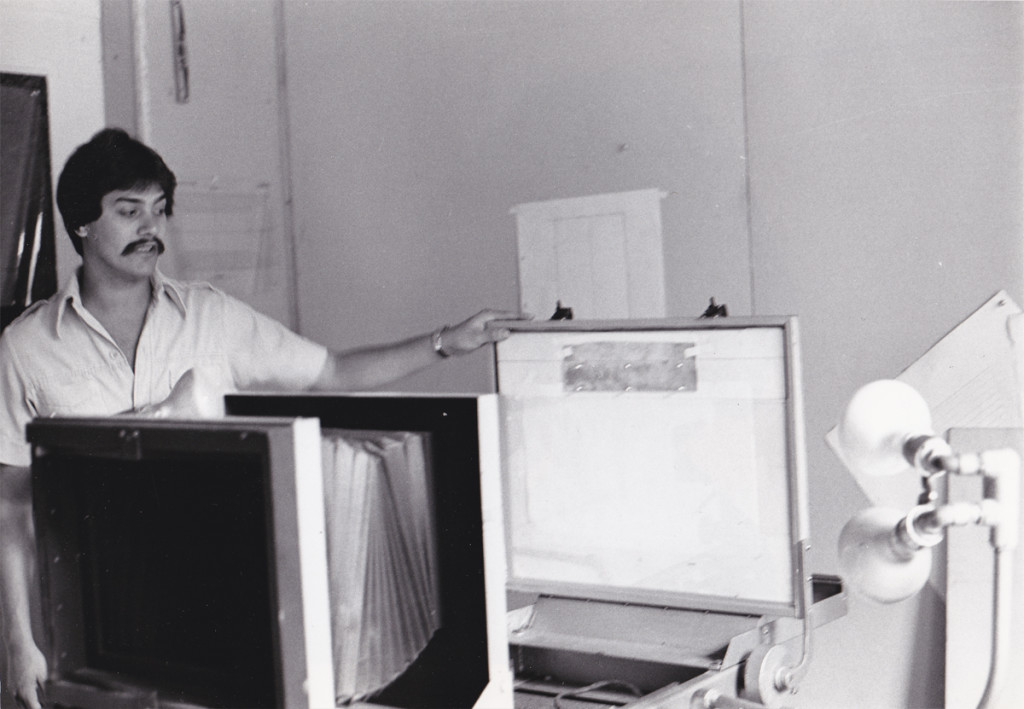

This is Cosmo Pepe; he was one of the leaders of the Xerox department.

It was Bill Kulhanek‘s department, but Cosmo really did great work.

They had this room-sized machine that they converted drawings into cels.

It was all new to NY, and the whole thing was so experimental.

Especially when Dick decided to do the film with grey toner rather than black.

The film always felt out of focus to me (even though it wasn’t.)

In the end when they rushed out the last half of the film, Hanna Barbera

sub-contracted the Xeroxing, and it was done in a sloppy and poor black line.

9

9

This is Corny Cole. He was the designer of the film, and all the great art

emanated out of his Mont Blanc pen nib. Or maybe it was a BIC pen.

Whatever, it was inspirational.

I wrote more about him here.

10

10

The gifted and brilliant animator, Hal Ambro. Can you tell that

I admired the man? I wanted badly to meet him during this production,

but that never was to happen. Now, I can only treasure his work.

11

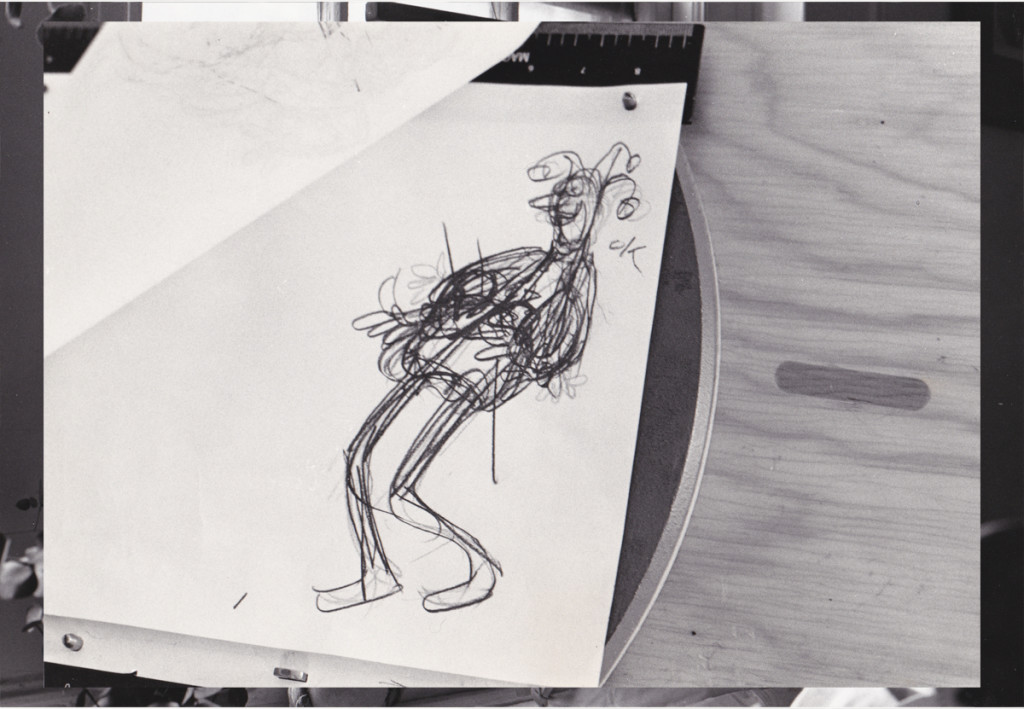

11

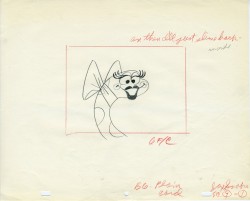

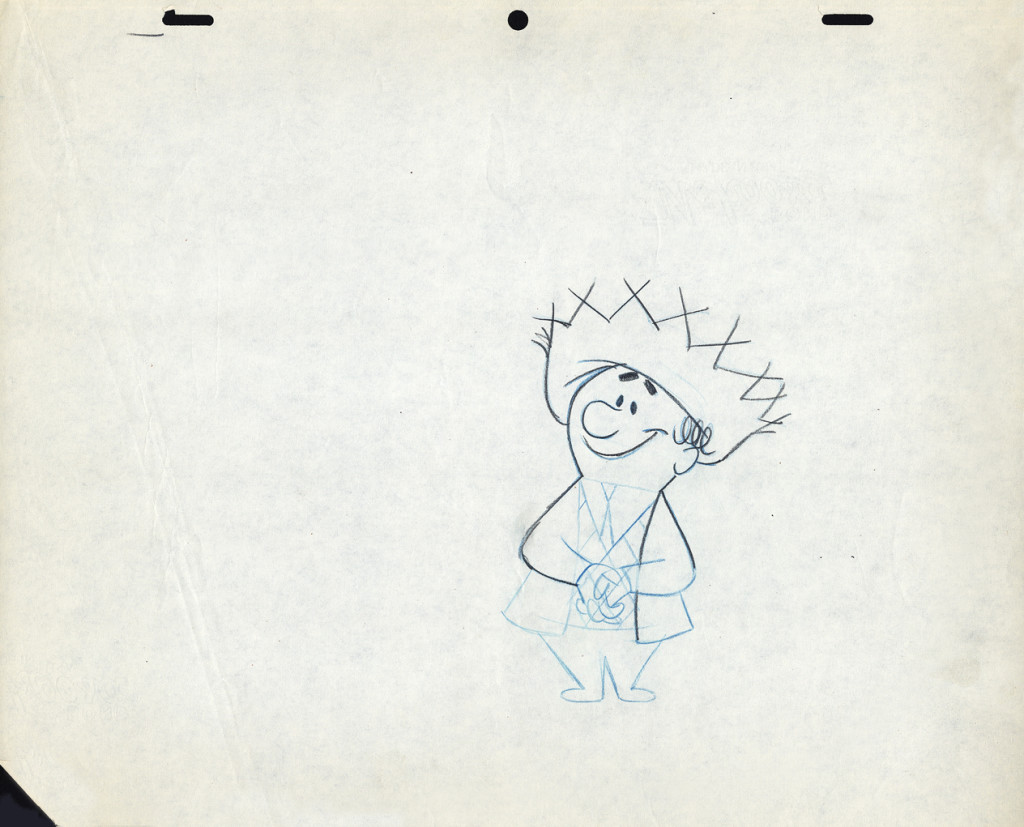

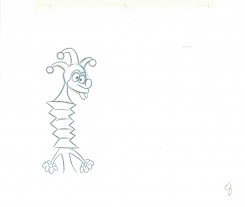

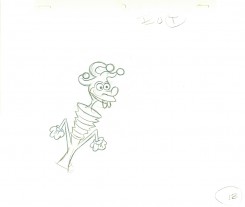

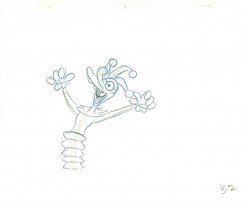

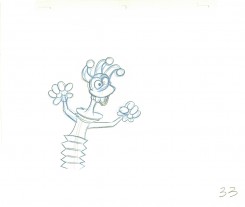

This is a very rough planning drawing that Grim Natwick did on

the Jack-in-the-Box he animated. See the scene here.

12

12

Here’s a close up of that very same drawing.

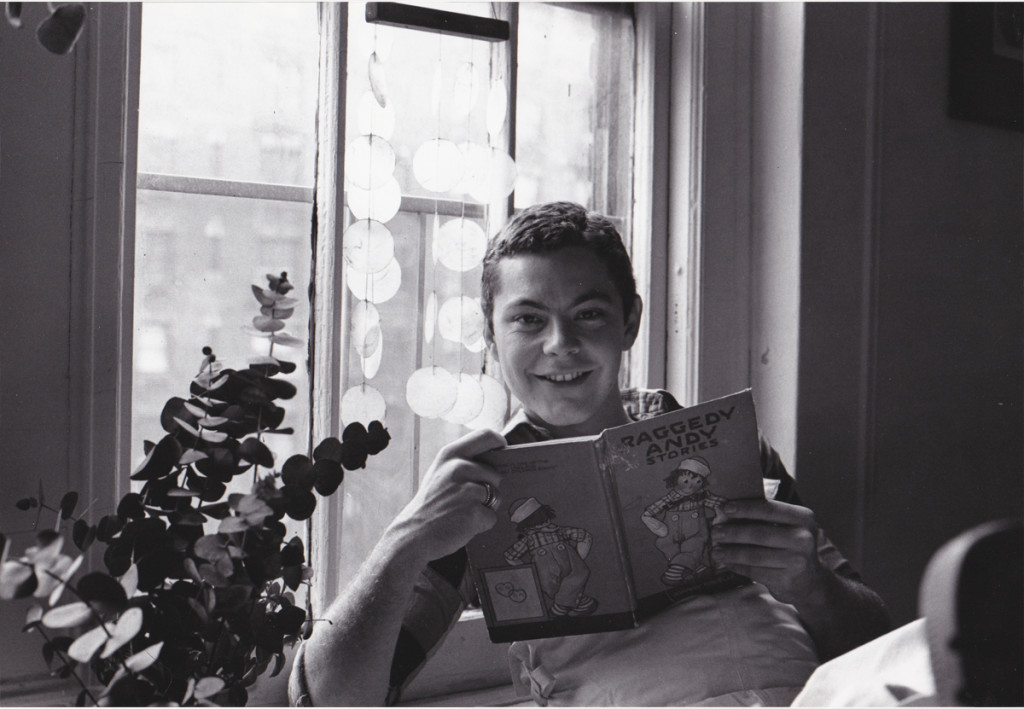

13

13

Mark Baker did the voice of Raggedy Andy.

He’d won the Tony Award as Best Featured Actor in the musical, Candide.

14

14

Didi Conn, the voice of Raggedy Ann, with Chrystal Russell, an animator

of Raggedy Ann. She backed up Tissa David who was the primary actor for

that character and did most of the film’s first half. Chrystal did many

scenes in the first half and most of the second.

She had a rich identifiable style all her own.

15

15

Sue Butterworth, head of the BG dept who designed the watercolor style

of the film. Michel Guerin, her assistant, can be seen in the rear.

Bill Frake was the third part of that BG department.

16

16

Painter, Nancy Massie. A strong and reg’lar person

in the NY animation industry. She’d been working forever for a reason.

On the average, I spent about an hour a day down in the Ink & Pt dept.

Often they had problems to resolve with some animator’s work. Either the

exposure sheets were confusing or they didn’t match the artwork, or there

was some question that they found confusing. My being available made it

helpful to them, and I did so without hesitation.

17

17

Checker, Klara Heder. Another solid person

within the NY industry.

Generally, before a scene left my department for the I&Pt dept., I’d

have studied the exposure sheets and felt I knew the scenes before

they were handed out to the Inbetweener or Assistant. It meant taking

a lot of time with the work in studio so that I was not only prepared

to answer questions of a checker but the Inbetweener as well.

18

18

Sorry I don’t know who this is. If you have info,

please leave it for me. For some reason, I’d thought

he was an inbetweener (which would’ve made it odd for

me not to recognize him by name.) Apparently he’s a painter.

19

19

Carl Bell was the West Coast Production Coordinator.

We spoke frequently during the making of the show.

When I left the film, I went to LA for a couple of weeks.

Chrystal Russell threw a small party for me, and Carl came.

(I think he might have brought Art Babbitt, who was there.)

The group was small enough that we could have a talk that we all

participated in. We talked for some time (though not about

Raggedy Ann.) It was great for me.

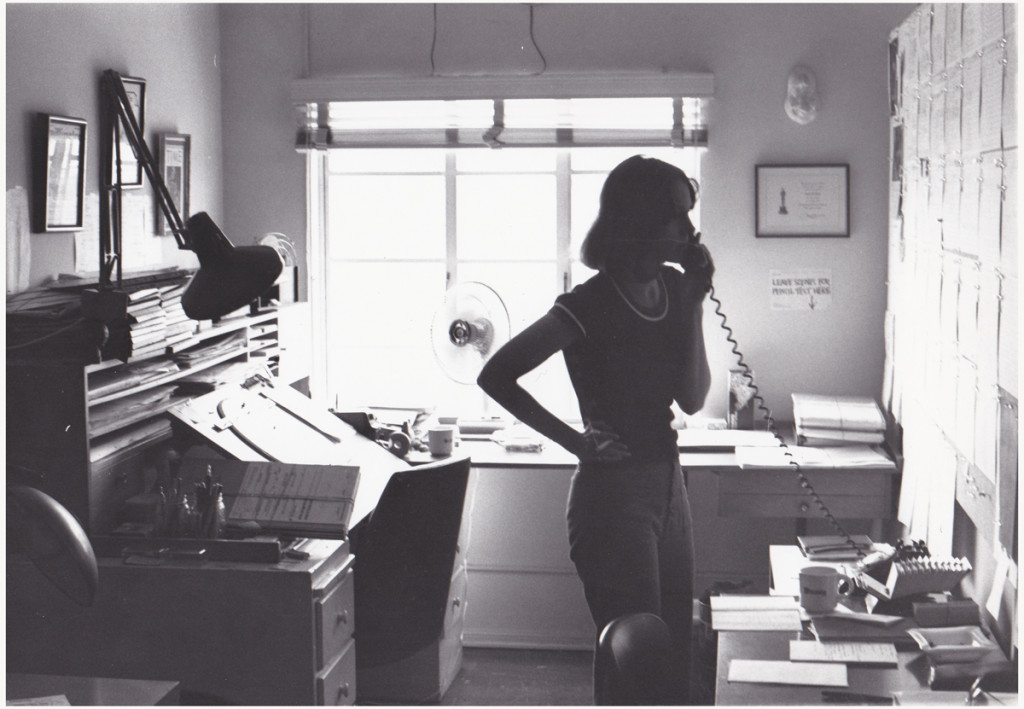

20

20

Jan Bell, Carl’s wife, was the West Coast Office Manager.

21

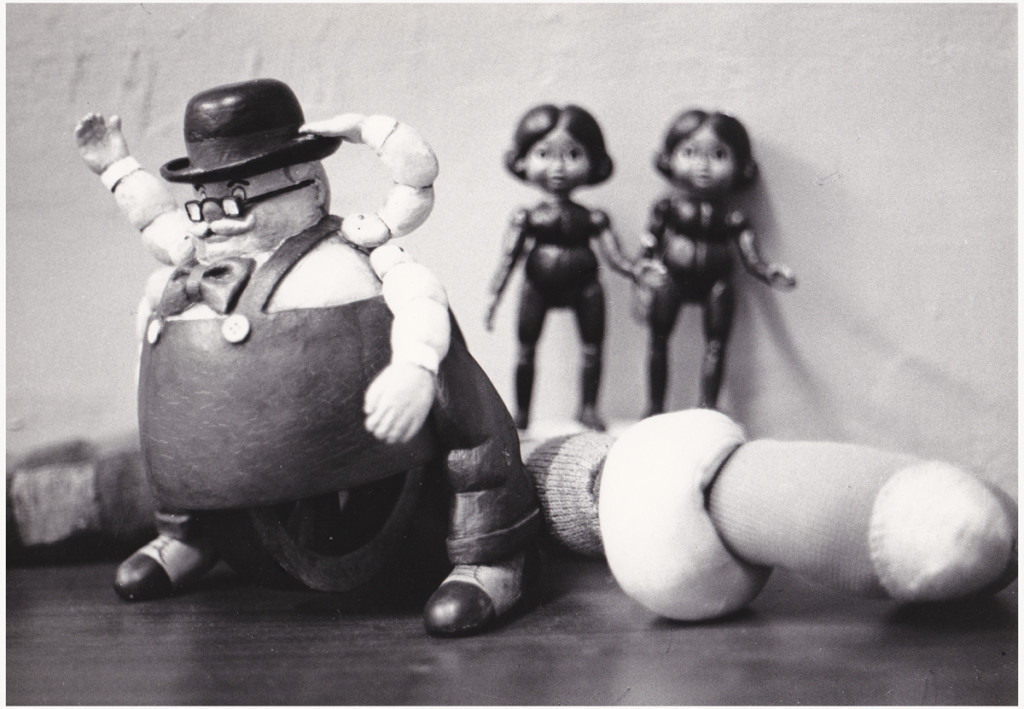

21

Maxie Fix-it. This was a great doll that wound up to get the legs going.

He rolled around the floor beautifully. The “Twins” in the back were animated

by Dan Haskett. though I’m not sure they gave him credit for it. I was a bit

embarrassed by these characters. They were just a naked bit of racism running

about our cartoon movie for very young children.

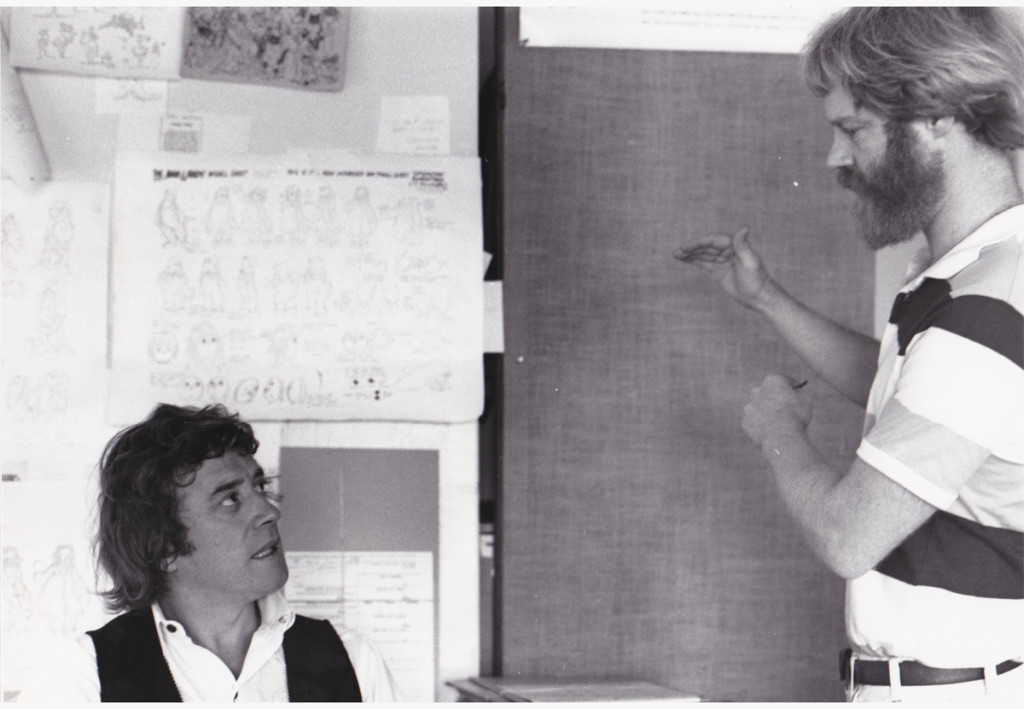

22

22

Gerry Potterton (left) and John Kimball (right).

Gerry was one wonderful person. I always enjoyed spending time with him.

He produced/directed a number of intelligent, adult animated films.

This includes an animated Harold Pinter‘s Pinter People.

After Raggedy, I tracked Gerry down to get to see Pinter’s People. It was

rather limited but full of character. Gerry knew how to handle the money

he was given, unlike some other directors.

John Kimball was, at the time, not in the caliber of Babbitt or Ambro or

David or Hawkins or Chiniquy. However, he did some imaginative play

on a few scenes which were lifted whole from strong>McCay’s Little Nemo

in Slumberland. One of these scenes I animated but was pulled

from it before I could finish it. I had too much else to do with the

tardy inbetweens of Raggedy Ann (an average of 12 drawings per day)

and the stasis of the taffy pit (an average of 1 inbetween per day).

Too many polka dots on Ann and too much of everything in the pit.

23

23

Fred Stuthman, the voice of the camel with the wrinkled knees.

He did add a great voice for the camel, though for some reason

I remember his being a dancer, predominantly.

All photos copyright ©1977 John Canemaker

.

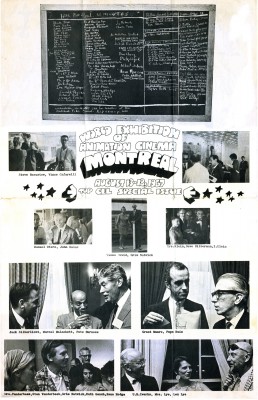

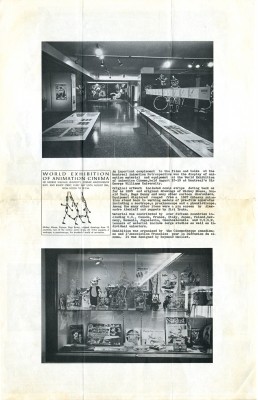

Events &Festivals &repeated posts 14 Apr 2013 05:21 am

Montreal Expo 1967 – recap

- Today I’m posting a special issue of Top Cel, the NY animation guild’s newspaper. Dated August 1967, it celebrates the Montreal Expo animation conference and exhibition held that summer. Obviously, this was the place to be that year if you were an animation lover.

Just take a look at that list of signatures of attendees. Some of them are:

Just take a look at that list of signatures of attendees. Some of them are:

Chuck Jones, Peter Foldes, Manuel Otero, Edith Vernick, Abe Levitow, Don Bajus, Bill & Fini Littlejohn, John Halas, Ward Kimball, Ken Peterson, Shamus Culhane, Carl Bell, Pete Burness, Ub Iwerks, Gerald Baldwin, I. Klein, Gene Plotnick, Ian Popesco-Gopo, Carmen d’Avino, Bill Mathews, Len Lye, June Foray, Bill Hurtz, Spence Peel, Paul Frees, Steve Bosustow, Dave Hilberman, Stan Van der Beek, Les Goldman, Jimmy Murakami, Mike Lah, Robert Breer, Tom Roth, Art Babbitt, Feodor Khitruk, Fred Wolf, Ivan Ivanov-Vano, Paul Terry, J.R. Bray, Walter Lantz, Otto Messmer, Dave Fleischer, Ruth Kneitel, Bruno Bozzetto, Bob Clampett, Karel Zeman, Dusn Vukotic, Bretislav Pojar, Jean Image, Grim Natwick, Tissa David, Barrie Nelson, Andre Martin, Ed Smith, Dick Rauh, and John Whitney.

I guess they don’t make Festivals like they used to. There doesn’t seem to be much written about this event, and I wish some of those in attendance would write about it.

From the Wikepedia entry for Bill Tytla, there’s the John Culhane quote: On August 13, 1967, the opening night of the Montreal Expo’s World Exhibition of Animation Cinema, featured a screening of Dumbo as part of an Hommage Aux Pionniers. Tytla was invited, but worried if anyone would remember him. When the film finished, they announced the presence of “The Great Animator.” When the spotlight finally found him, the audience erupted in “a huge outpouring of love. It may have been one of the great moments of his life,” recalled John Culhane. I’m sure there were many such moments.

Just to make it all personal, let me tell you a story, although this has nothing to do with Montreal’s Exhibit.

Just to make it all personal, let me tell you a story, although this has nothing to do with Montreal’s Exhibit.

Pepe Ruiz was the u-nion’s business manager. In 1966 – the year prior to this expo – I was a junior in college, determined to break into the animation industry. Of course, I knew the military was coming as soon as I graduated, but I called the u-nion to have a meeting with Pepe. I wanted to see what the likelihood of a “part time job” would be in animation. This took a lot of courage on my part to see what the u-nion was about. I pretty well knew part time jobs didn’t exist. There was no such thing as interns back then.

Pepe was an odd guy who kept calling me “sweetheart” and “darling” and he told me that it was unlikely that I could get something part time in an animation studio.

However he did send me to Terrytoons to check it out.

I met with the production manager, at the time, Nick Alberti. It was obvious I was holding up Mr. Alberti’s exit for a game of golf, but he was kind and said that part time work wasn’t something they did. (He moved on to Technicolor film lab as an expediter after Terry‘s closed. I had contact with him frequently for years later, though I never brought up our meeting and doubt he would have remembered it.) Ultimately, I was pleased to have been inside Terrytoons‘ studio before it shut down shortly thereafter. A little adventure that let me feel as though I was getting closer to the world of animation.

The photos of the Expo are worth a good look. I’ve singled out those above to place around my text. The picture of Tissa and Grim is a nice one of the two of them together.

Ed Smith was the Top Cel editor at the time, and he put together a creative publication.

1

1 2

2

(Click on any image to enlarge.)

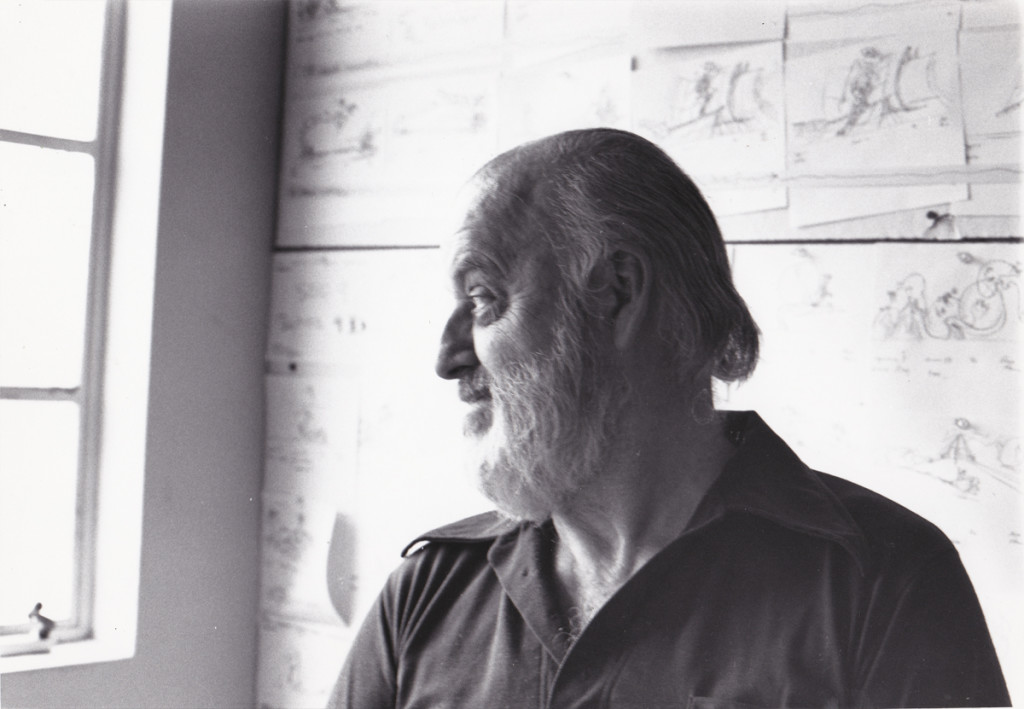

Action Analysis &Animation &Animation Artifacts &repeated posts &Richard Williams &Tissa David 27 Mar 2013 04:26 am

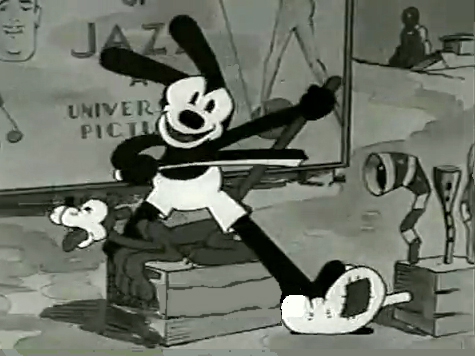

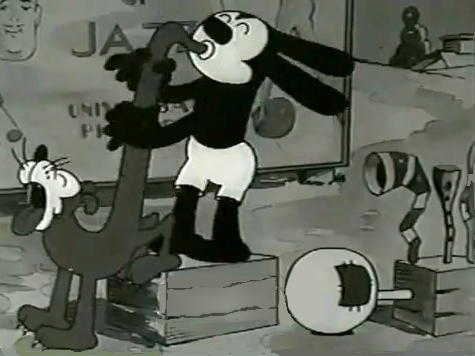

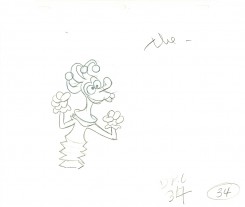

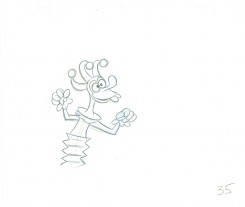

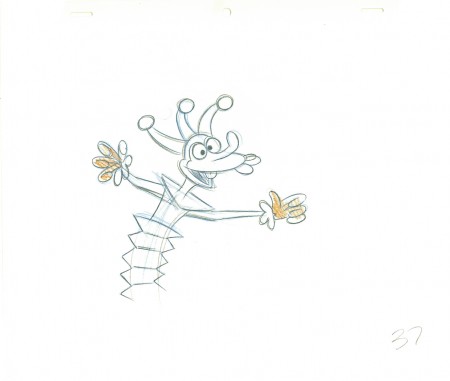

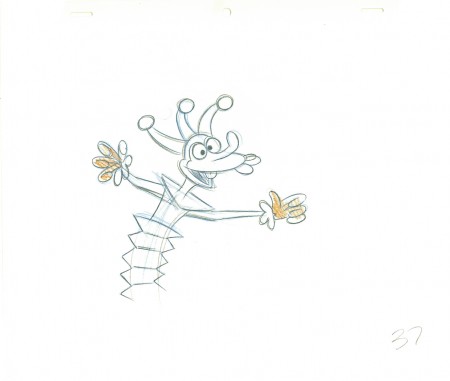

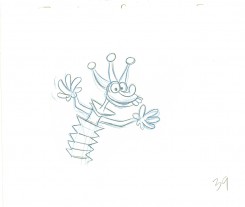

Grim’s Jester – recap

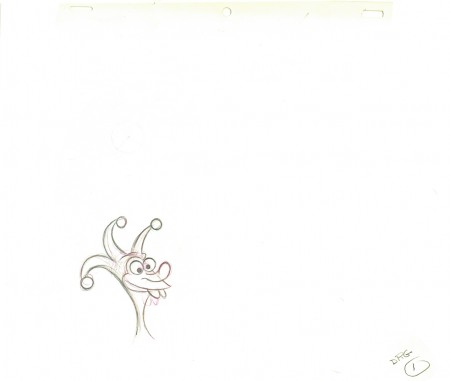

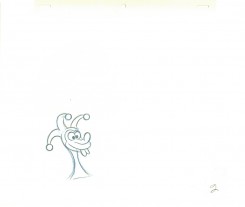

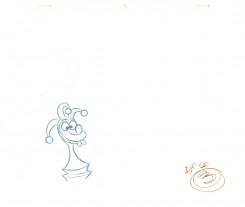

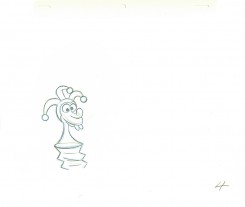

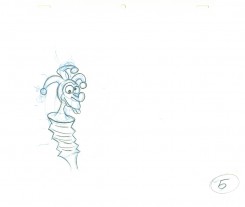

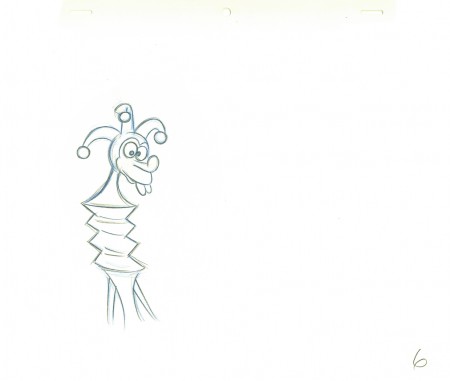

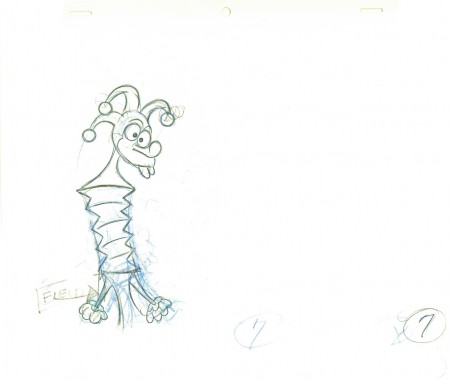

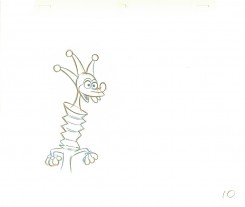

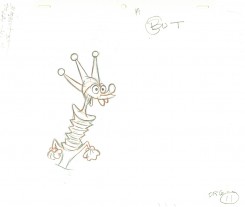

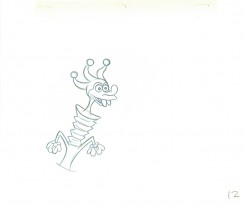

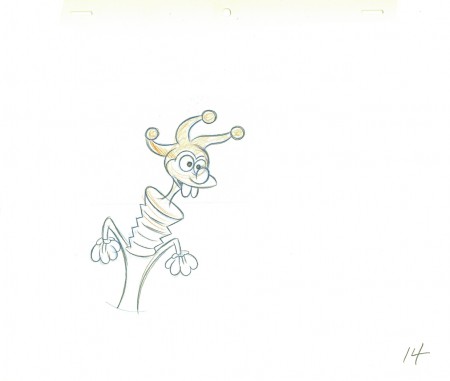

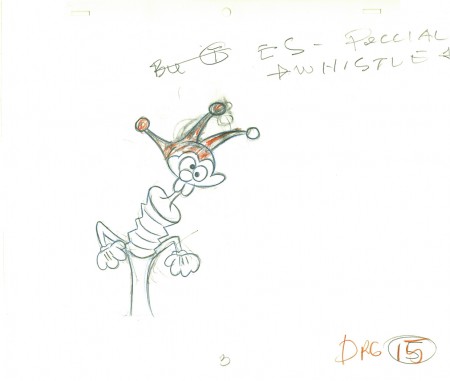

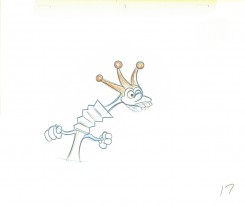

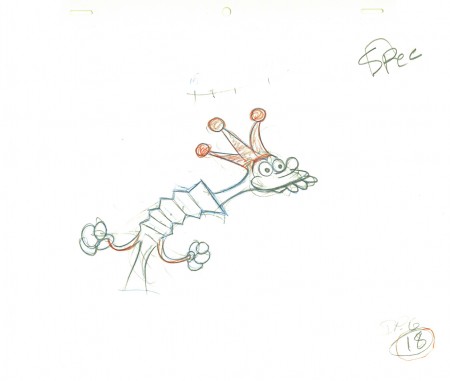

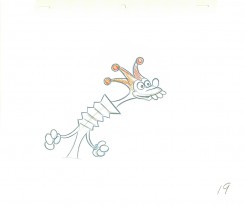

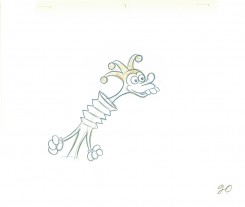

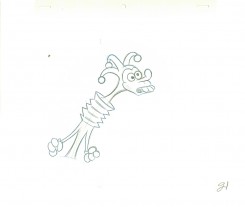

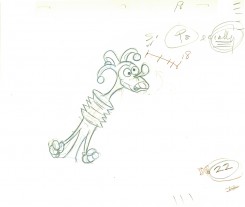

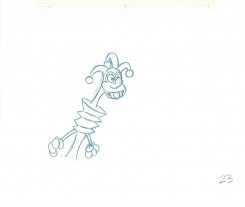

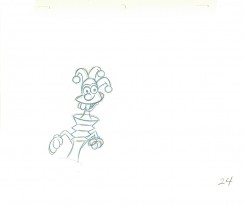

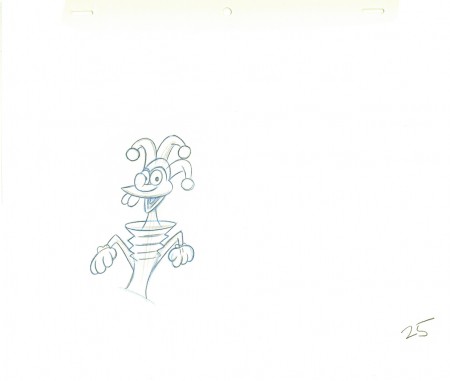

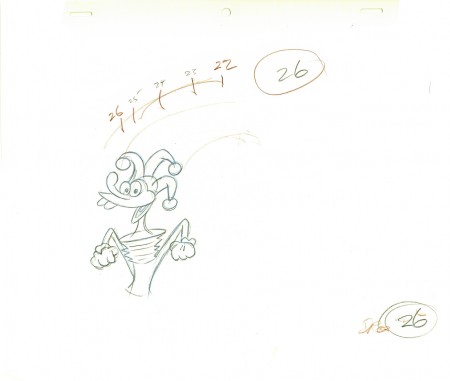

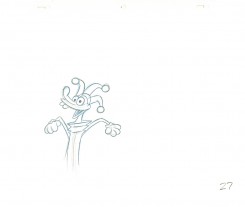

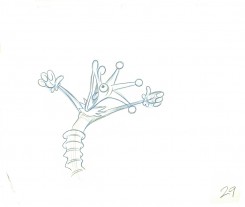

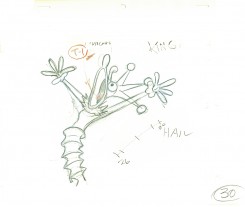

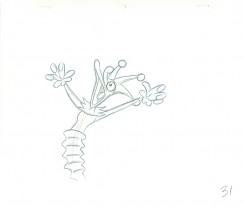

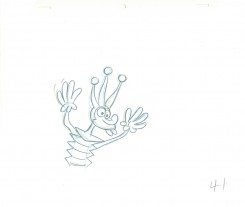

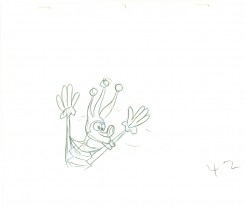

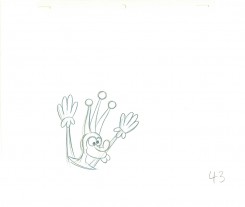

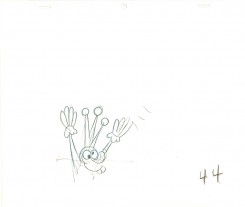

- Yesterday I focused on a couple of scenes Grim Natwick animated in his early days at the Fleischer studio. He was obviously experimenting with distortions, breaking of the joints, the visibility of inbetween drawings and how much he could get away with in “Rough drawings.”

This, of course, isn’t the animator that Grim became, but gives us some light to understand what did make up that animator. The scene here today is something I’d posted on my blog once before, in 2010. It features a lot of Grim’s ruffs as well as the clean ups by Richard Williams, himself.`

You can see Grim’s drawings erased and cleaned up. (The semi-erased semblance of Grim’s very large numbers remain on many of the drawings, as do Grim’s notes. The inbetweens were all done by Dick. (It’s Dick’s writing in the lower right corner, and I remember him doing this overnight.)

The scene is all on twos. There are two holds which Dick changed to a trace back cycle of drawings for a moving hold. It actually looks better on ones, but there was a lip-synch that Grim had to follow. It is interesting that both Tissa David, one of the five key animators on this film, and Grim Natwick, who Tissa had assisted for at least 20 years, both shared the one assistant on key scenes in this film – Richard Williams. Eric Goldberg assisted on many of Tissa’s other scenes.

1

1.

2

2  3

3.

4

4  5

5.

6

6An inbetween by Dick Williams.

.

7

7A cleaned-up extreme by Grim Natwick.

.

8

8  9

9.

10

10 11

11.

12

12 13

13.

14

14Dick Williams clean-up.

.

15

15Grim Natwick (sorta) cleaned-up rough.

.

16

16 17

17.

18

18Grim Natwick rough.

.

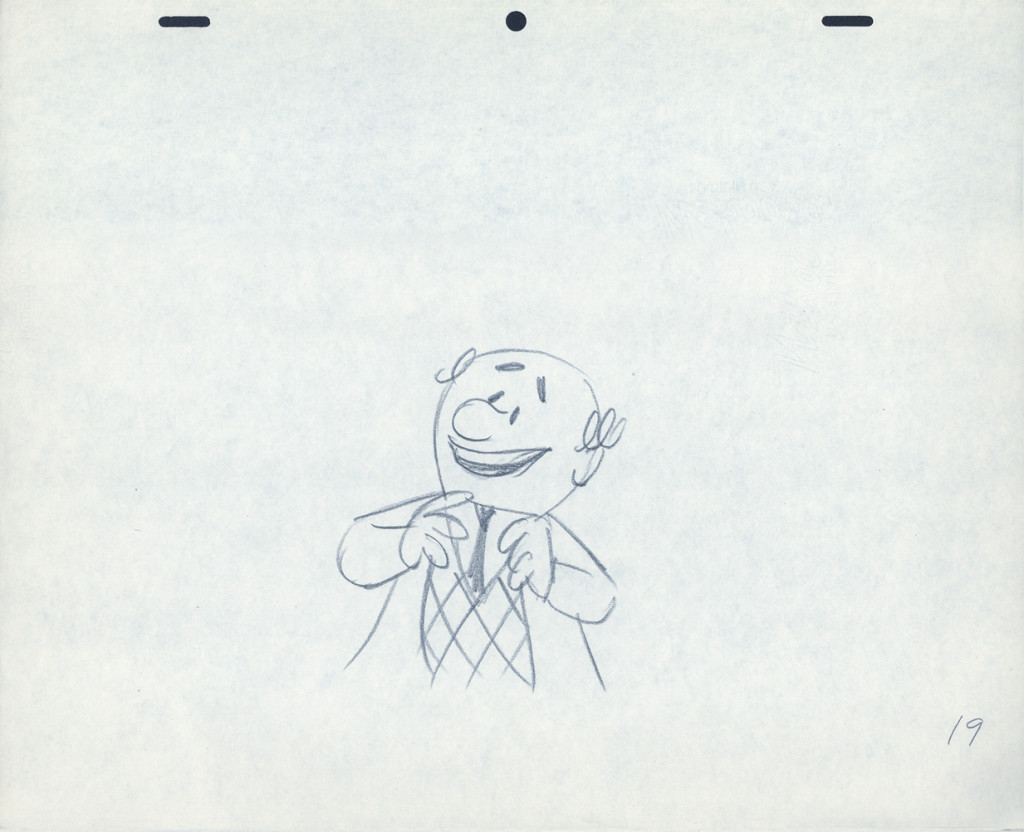

19

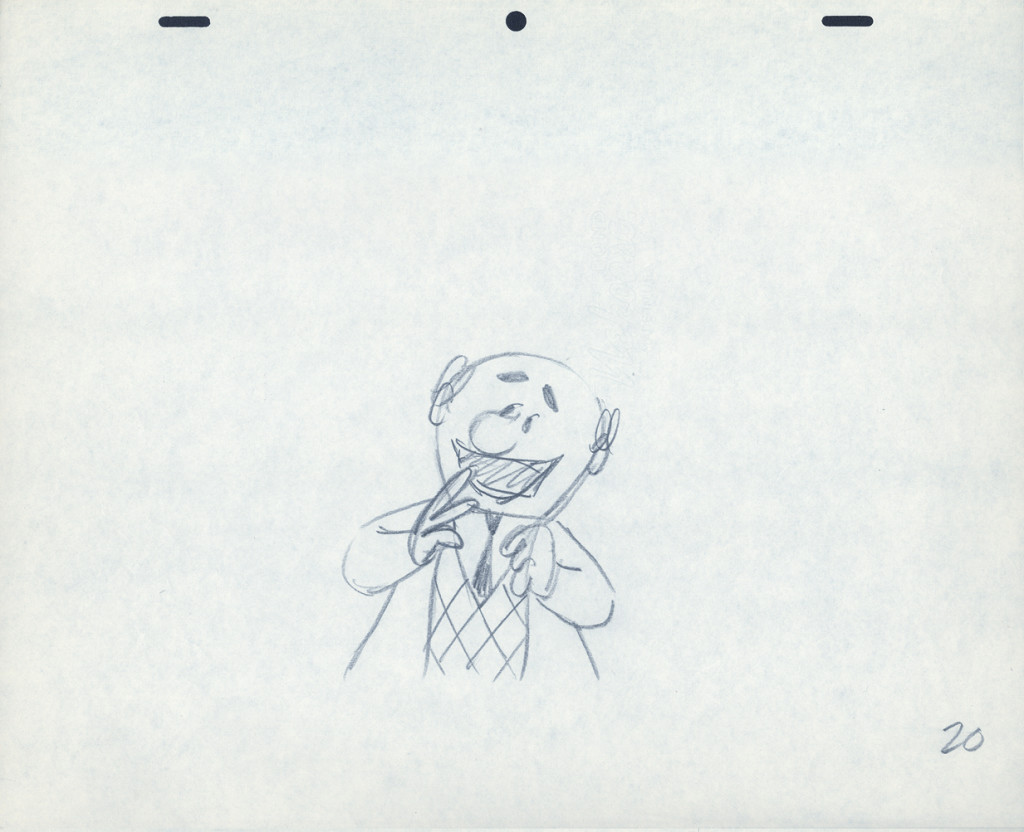

19 20

20.

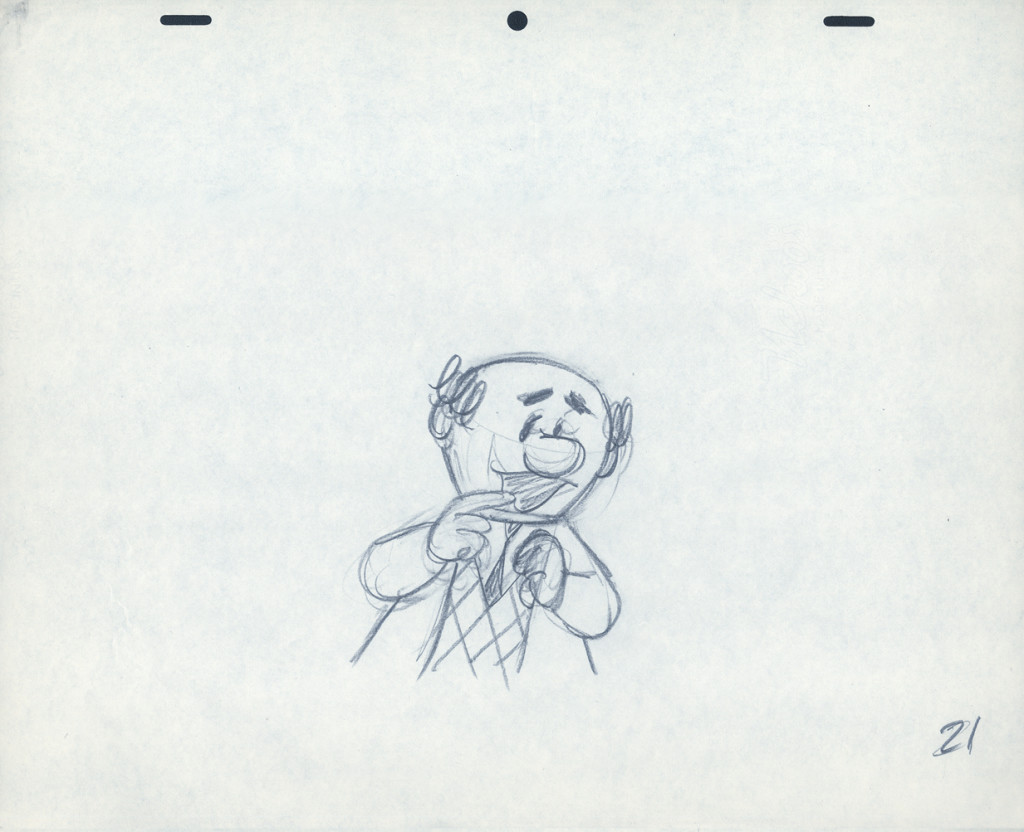

21

21 22

22.

23

23 24

24.

25

25Williams inbetween.

.

26

26Natwick ruff, cleaned up.

.

27

27 28

28.

29

29 30

30.

31

31 32

32.

33

33 34

34.

35

35 36

36.

37

37Dick’s clean-up inbetween.

.

39

39Definitely a Grim Natwick drawing – cleaned up by Dick (his handwriting).

.

39

39 40

40.

41

41 42

42.

43

43 44

44.

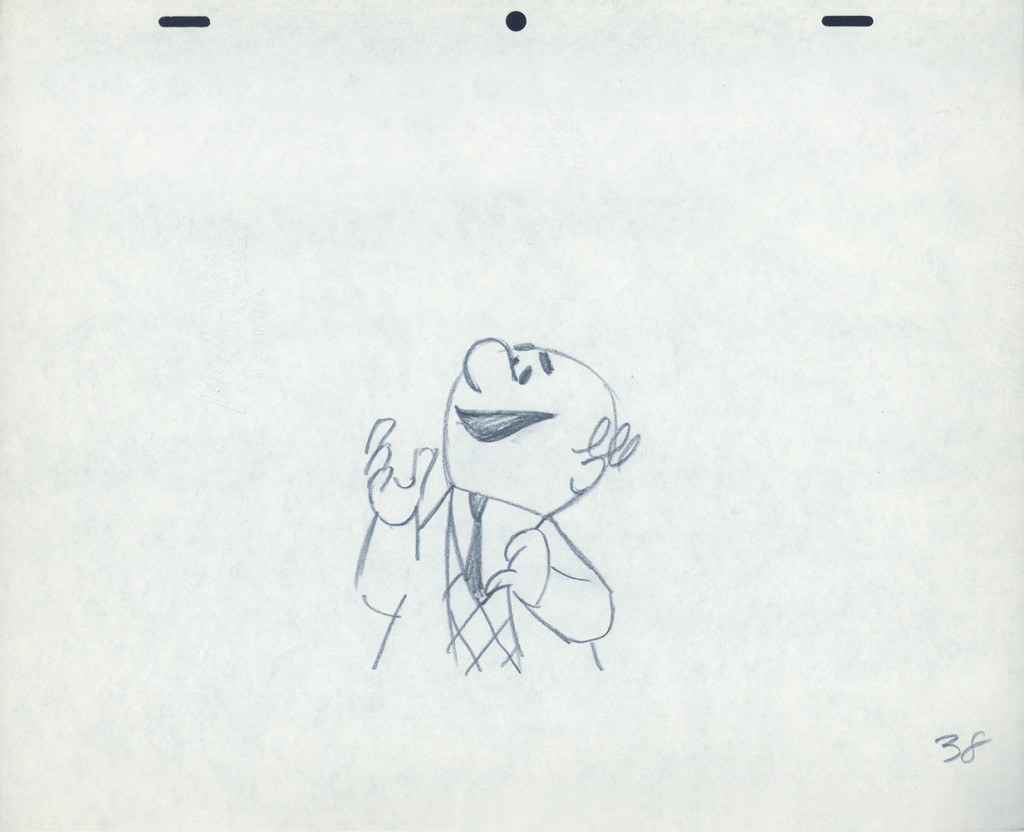

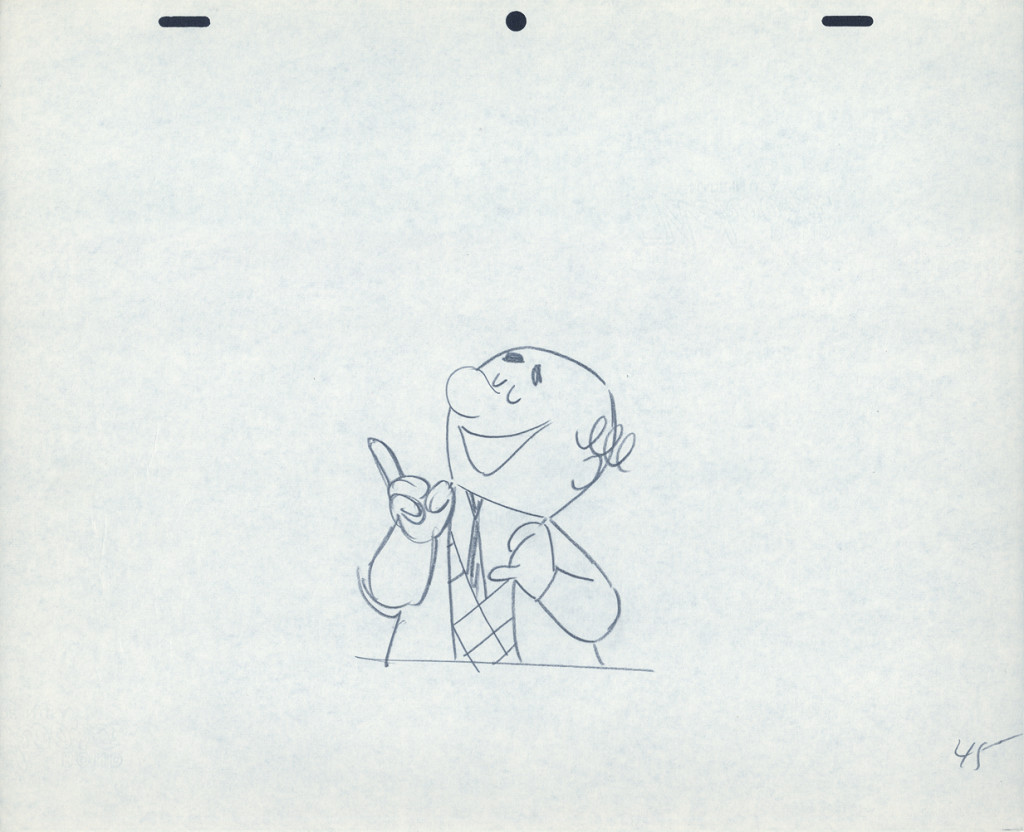

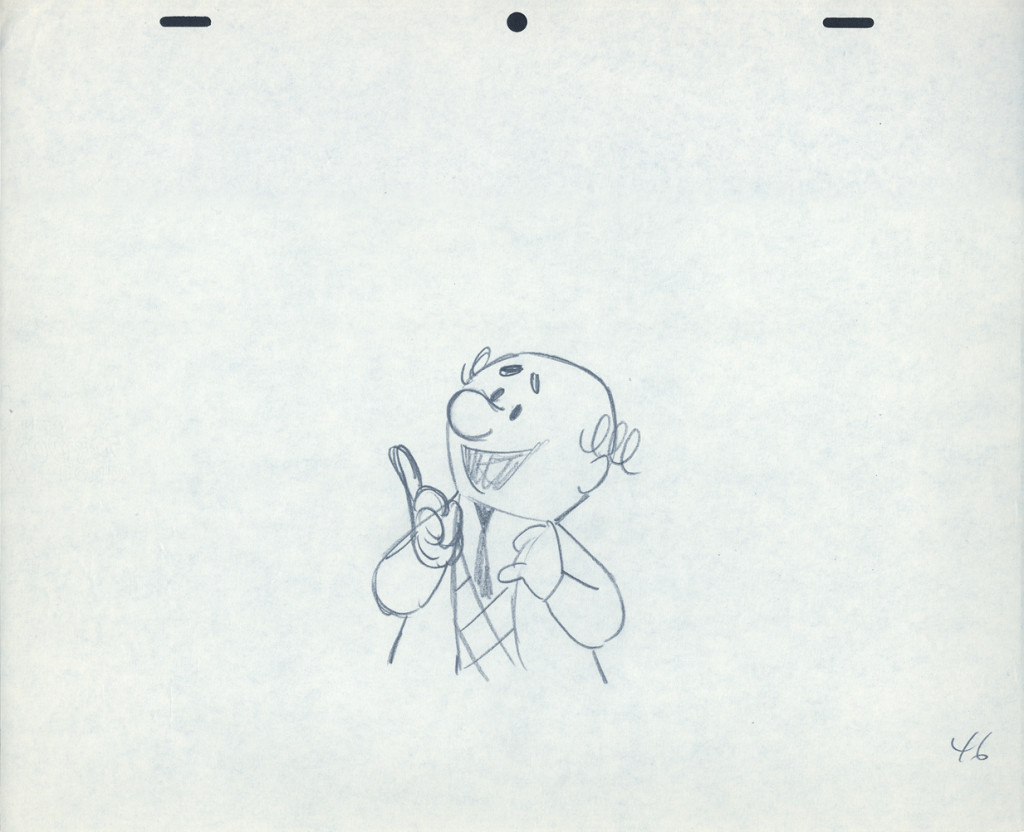

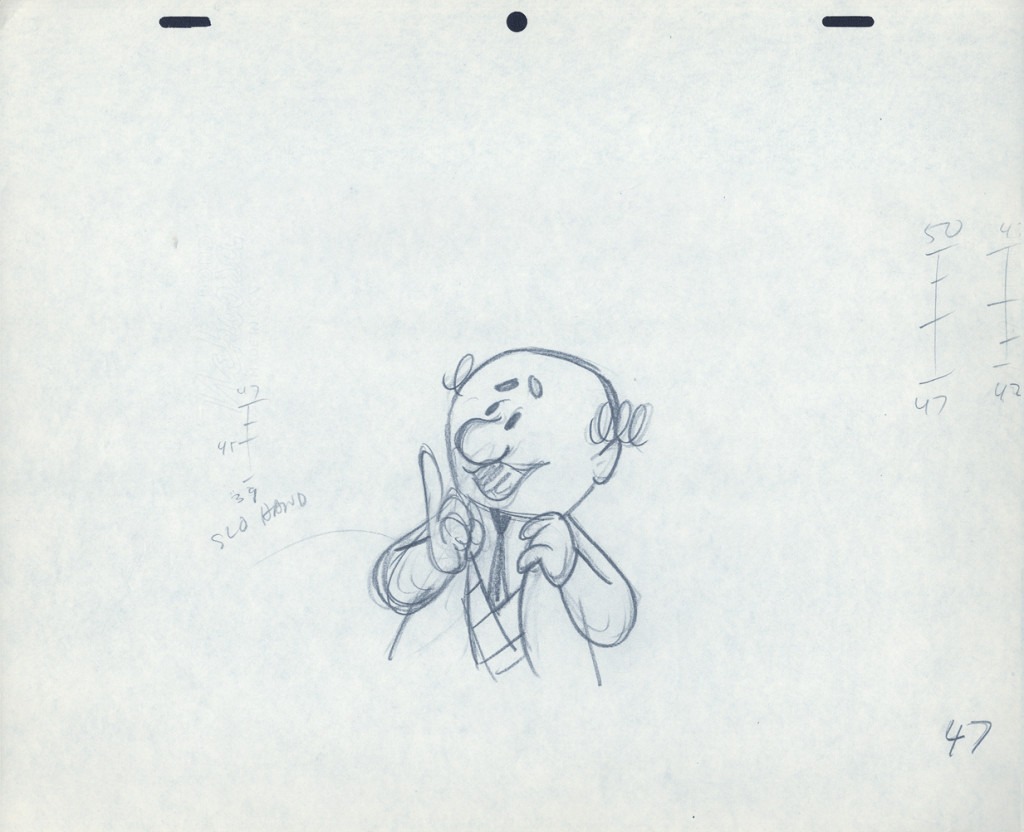

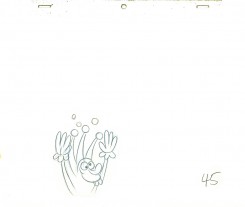

45

45 46

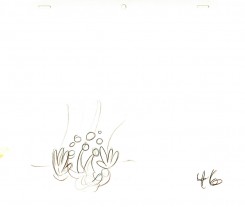

46.

47

47Drawings 44-47 are all Grim’s roughs with minor CU.

.

_____________________________

Here’s a QT movie of the complete action from the scene.

The scene is exposed on twos per exposure sheets.

_____________________________

Here are the folder in which the two exposure sheets

are stapled (so they don’t get separated.)

Action Analysis &Animation &Fleischer &Frame Grabs 26 Mar 2013 05:45 am

Grim – Distortions Smears, Abstractions & Emotions – 3

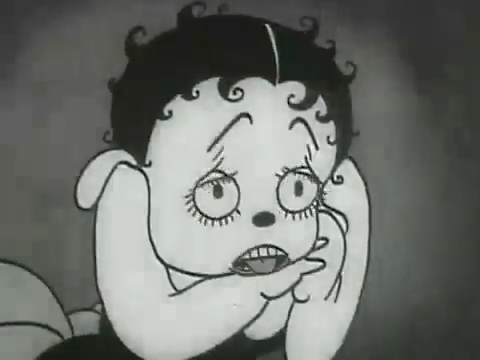

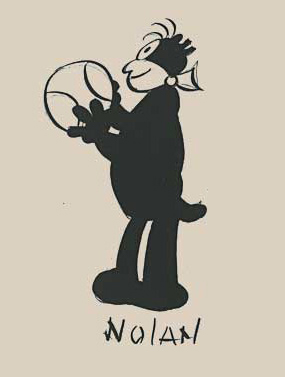

- In 1930, the animation in the Fleischer studio (as evidenced by Michael Barrier in his great book, Hollywood Cartoons) was pretty much controlled by the timing department. They supported a very even sense of timing and would expose everyone’s animation in the house meter. This virtually destroyed the timing within the studio. Their idea was that every drawing had to overlap the drawing before and after. It was done to such an extreme that it caused the even timing throughout their films.

There was at least one animator free of the timing department. Grim Natwick was the key guy in the studio, at the time. His animation was built, back then, on a distortion, a freedom of expression, that very much resembled what Bill Nolan was doing in Hollywood. The difference was that Natwick could draw, so his artwork was planned, designed to look that way. It wasn’t just a matter of straight ahead animation causing distortion. It allowed distortion with scenes going back to square one every so often to hold off the appearance of distortion. The inbetweens distorted and, in a way, smeared always to come back to a nice, tight pose of an extreme.

The film “Dizzy Dishes” is the perfect example of this style. This was actually the first Betty Boop cartoon, and Betty, a plump dog sings broadly. She really goes wild as she sings a song on top of a table à la Marlene Dietrich!. Here are some frame grabs from a couple of connected scenes to give you an idea of what was going on.

1

1

If you jump ahead to Fleischer’s “Barnacle Bill”, also from 1930, you’ll find this wild scene where Betty is seducing Bill, you’ll see all sorts of distortion in the inbetweens which Grim has maneuvered for Betty’s movements on the couch. Note how well posed his extreme positions are drawn despite the distorted inbetweens, when she is moving.

1

1

Look at the beautiful drawings (above) of this character in some of these extremes from this film. The character of Betty isn’t moving whereas Bimbo – I mean Barnacle Bill is all over the place. Yet your eyes are on Betty in that held position.

Now, let’s look at what the inbetweens are doing as Betty gets from one pose to the next. It’s really funny. Grim has found a way to create a sympathetic, adult and female character, yet he keeps her funny with the surface of the animation.

1

1

At times in the animation, Betty’s hand may turn into a claw, but that might be that Grim delivered a rough which was poorly cleaned up by an assistant. Or perhaps the inker just inked from a rougher drawing, perhaps a Grim “clean up” if there ever were such a thing. He worked ROUGH. In fact, that distorted claw of a hand doesn’t matter. It’s the extremes that counted for Grim, and he was experimenting with this animation to see if that really were true.

I’ve remembered over many years an interview with Dick Huemer,* who worked alongside Grim on some of these films. Huemer gets credit for inventing the inbetweener to use in the animation process. It allowed him to turn out more animation and not worry about the many drawings that would paste the scenes together. In that interview, Huemer said that it didn’t really matter what the inbetweens looked like. You could draw a “brick” and it would still work. They actually may have believed this, at that time. Grim is using the inbetweens to get somewhere else in putting the scenes together.

(Tomorrow, I’ll post, again, a scene Grim did for Raggedy Ann with Dick Williams’ clean ups alongside so you can see the variance.)

* In Recollections of Richard Huemer interviewed by Joe Adamson, [1968 and 1969] Huemer said:

- And i decided that I would save all that work of inbetweening by just having a bunch of lines or smudges, just scrabble, from, position to position, When something moved fast. To prove it, I had an alarm clock flying through the air, and right in the middle of the action I put a brick. And vhen they ran the finished

film you didn’t see the brickl It proved that you didn’t really see what was in the middle. But I overdid it.

Action Analysis &Animation &Commentary &Frame Grabs &Tytla 25 Mar 2013 06:05 am

Smears, Distortions, Abstractions & Emotions – 2

- I wrote about this stylistic animation device not too long ago. I was leading up to the master, of course, Bill Tytla. He distorted things, alright, and in the way he did it, he changed animation forever, as far as I’m concerned.

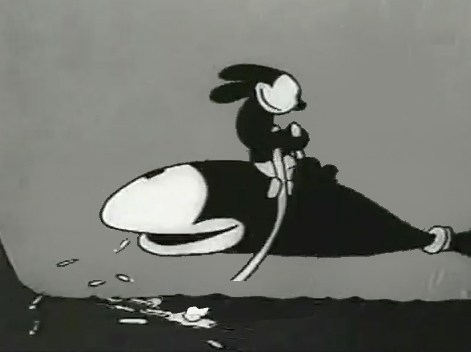

But I started that story by writing about traditional animation and where it came from and where it was going; leading to a sort of rebellion as animators started distorting things, generally, in working closely with their unconventional directors. I purposely skipped a step there, and I should go back a tiny bit and talk about a couple of animators from the silent/early sound days. Today I have Bill Nolan in my sights; tomorrow, Grim Natwick. It’s kind of important before going on to Bill Tytla.

In the animation community in 1927-1930, there were two key animators who were considered the leaders in the business:

In the animation community in 1927-1930, there were two key animators who were considered the leaders in the business:

Ub Iwerks at Disney (until he left to open his own studio) and

Bill Nolan (at first with Pat Sullivan & Felix the Cat, then with Mintz’ Krazy Kat, and then onto a series of topical gag films called “Newslaffs.”

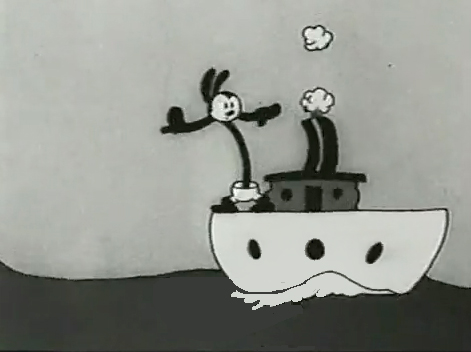

Both were considered the fastest animators in the country, and it was debatable as to which was quicker, though Iwerks was probably the guy. When Disney learned that Iwerks was leaving, he interviewed Nolan in New York to see if he were interested in replacing Iwerks. Disney offered a high salary of $150 per week for the job. It didn’t work out; Nolan was doing an unusual series, but ultimately went to ________________Nolan’s Krazy Kat looked original.

Oswald the Rabbit after Universal had taken

charge of it. Nolan just about ran the studio under Walter Lantz and allowed them to turn out an enormous amount of footage.

Nolan had developed a style known as the “rubber hose” style in that the limbs of a character were like flexible hoses and joints would be broken wherever the animator wanted. The style also featured very circular drawings. Stylistically, this fought the angularity of some other films that were being made and allowed Nolan to turn out many more drawings than usual. The roundness offered a faster line, and there was also quite a bit of distortion in Nolan’s drawings. Quite often the characters, Oswald, for example, didn’t even look like the character on the model sheet. In fact, you’d have to wonder if there was a model sheet, given the look of the animated character. Both Nolan and Iwerks were straight ahead animators, which meant they could easily go off model. Iwerks was better at holding things than Nolan, who seemed to enjoy being wild. Nolan would go back through his wild drawings and correct a couple of them, but would leave any other changes to lesser artists.

Nolan’s work was somewhat similar to the work of Jim Tyer, but I don’t think Tyer was drawing/animating that way to turn out faster work (though he was a very fast animator.) Nolan had to push the work out, and the rounded, distorted drawings enabled him to animate very quickly. As he went on, the artwork grew more and more wild, and it varied somewhat from the other animators’ work. Tyer tried to get his art to distort, as it does; Nolan just ended up there.

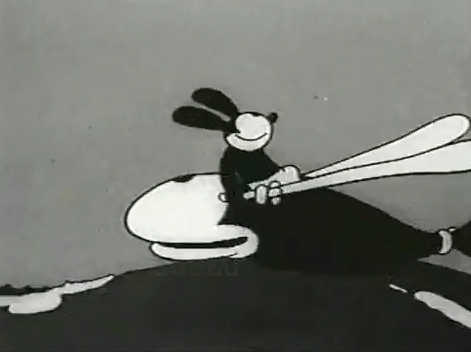

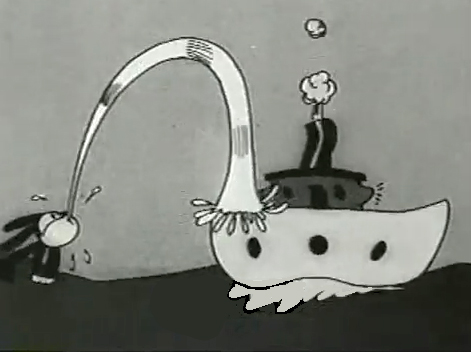

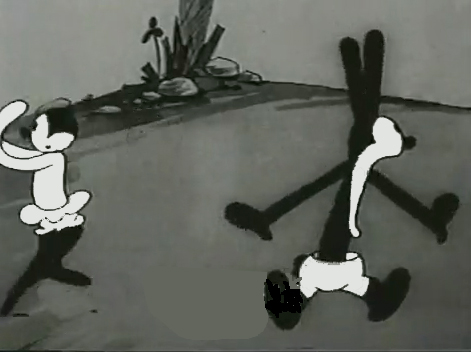

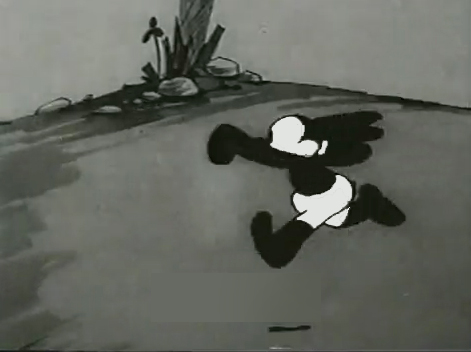

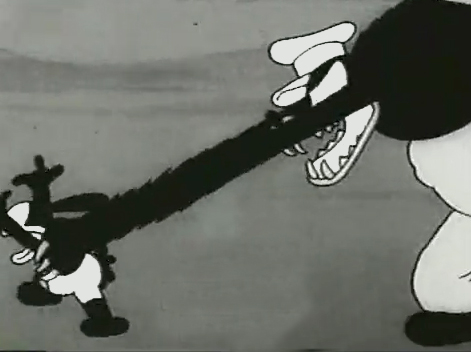

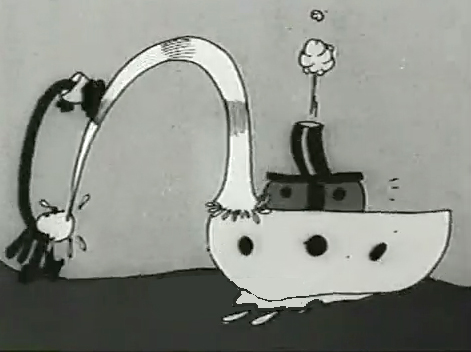

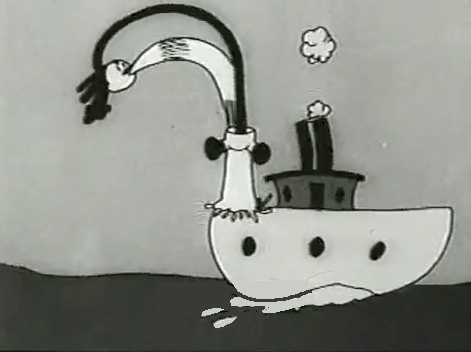

1

1  2

2I’d chosen a lot of stills from several of the

Universal/Lantz Oswald cartoons, animated by Nolan.

3

3  4

4

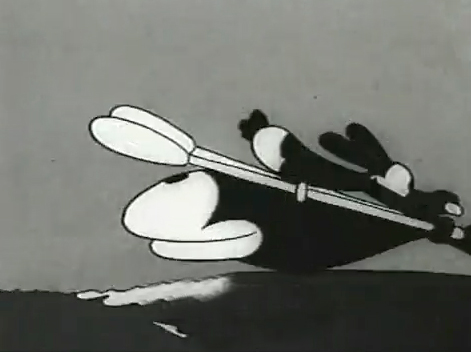

But so many of these from the short, “Permanent Wave,”

are good enough to illustrate my point.

13

13  14

14

His body moves out in front of his head

as it climbs up the water he’s spitting onto the boat.

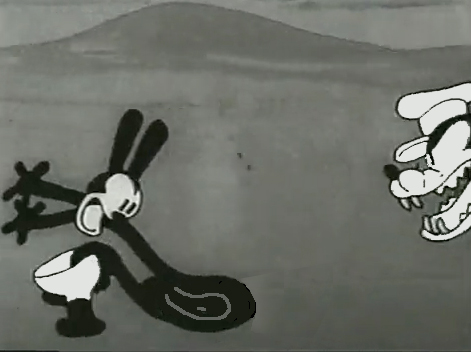

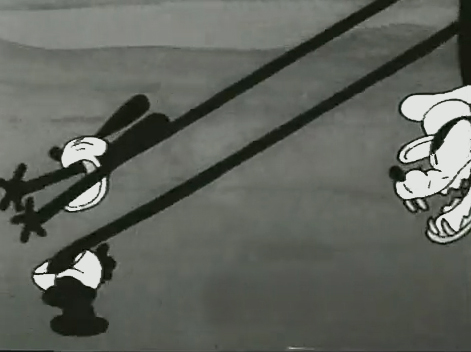

“The Hash Shop” was about as crazy as the animation and the gags went. Here’s one that ends the film.

By 1930, Bill Nolan seems to have settled down a bit. He still abstracts and distorts his animation, but he tries to fit in a bit more with other animators who aren’t drawing their animation quite so abstractly.

After Disney’s “The Three Little Pigs,” other studios tried to catch up with this new type of animation. Nolan and, to a lesser extent, Lantz, didn’t try very hard to change. They liked the way things were going. However, it didn’t take long for Lantz to move for a change in Oswald’s design. They went cuter and whiter on the rabbit.

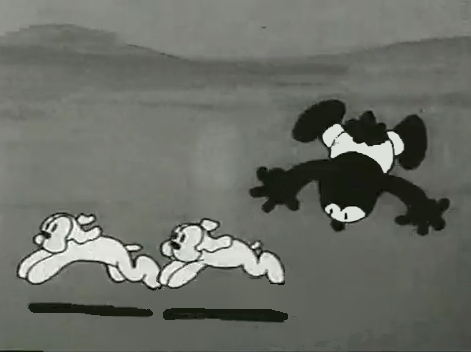

Here are some frame grabs from “My Pal, Paul.” In it Oswald wants to play music with jazz conductor/musician, Paul Whiteman. As it happens, Whiteman’s car breaks down while he’s driving through the woods, and the two get a bit of a duo as Whiteman plays the steering wheel like a clarinet. (Maybe that’s abstract enough.)