Search ResultsFor "fantasia"

Animation Artifacts &Bill Peckmann &Books &Disney &Illustration 03 Dec 2010 09:53 am

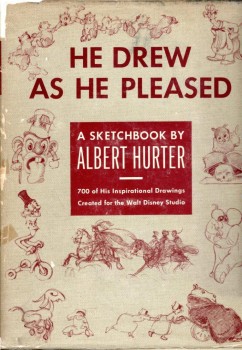

He Drew As He Pleased – 4

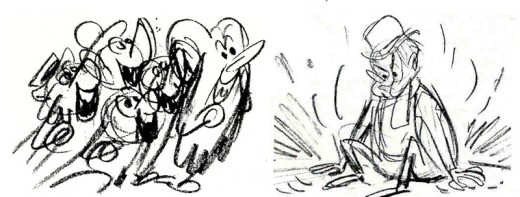

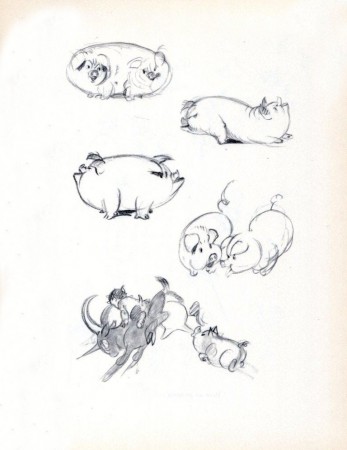

- Here are more pages from the book by Albert Hurter, He Drew As He Pleased (Simon and Schuster, 1948.) This gem is a rare book, indeed.

- Here are more pages from the book by Albert Hurter, He Drew As He Pleased (Simon and Schuster, 1948.) This gem is a rare book, indeed.

Albert Hurter was one of the European illustrators Disney brought into his studio for Snow White and Pinocchio. Hurter was the his own master, drawing designs which would be used generally to further the design of the features and Silly Symphonies.

A similar position seems to have gone to Joe Grant when he worked in the period during the making of Beauty and the Beast through The Hunchback of Notre Dame. Some of his drawings, as can be seen in John Canemaker‘s book, Two Guys Named Joe, are just as brilliant. Indeed, there were a lot of brilliant artists floating around the Disney studio in the late Thirties, early Forties.

Many thanks to Bill Peckmann for the loan of the book’s pages and the arduous task of scanning these illustrations.

50

50

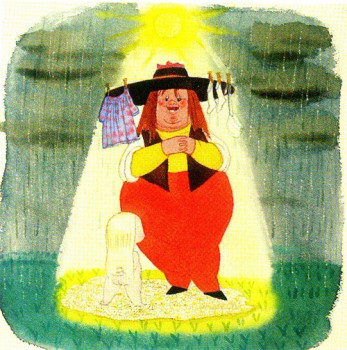

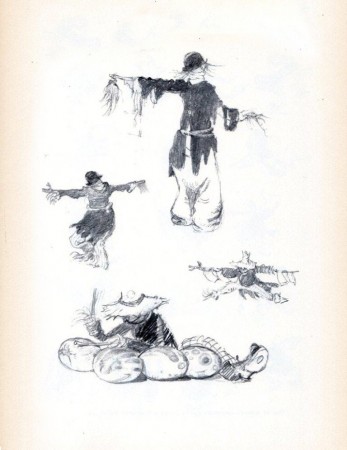

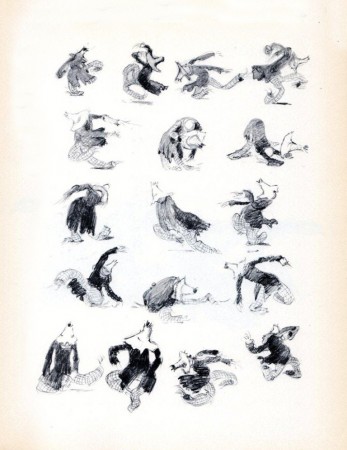

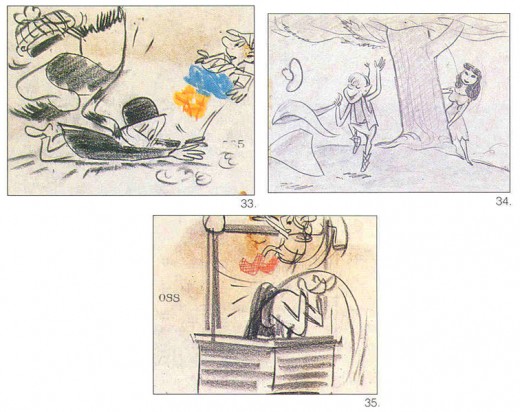

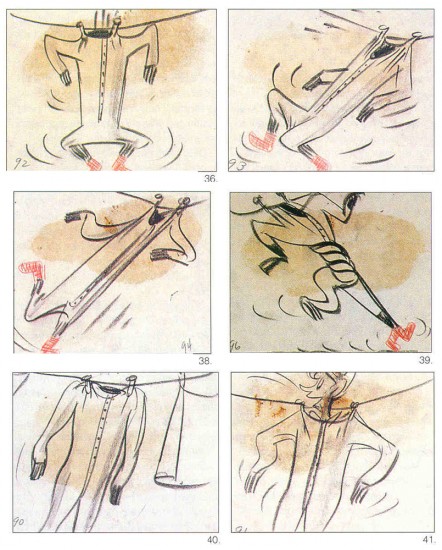

“He was fond of scarecrows . . . ”

51

51“They were so simple and natural . . .”

.

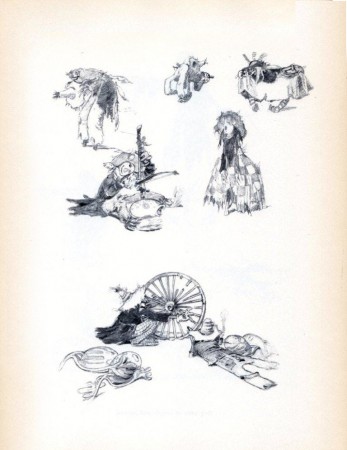

52

52“One of Albert’s ambitions was

to design a scarecrow ballet.”

.

53

53.

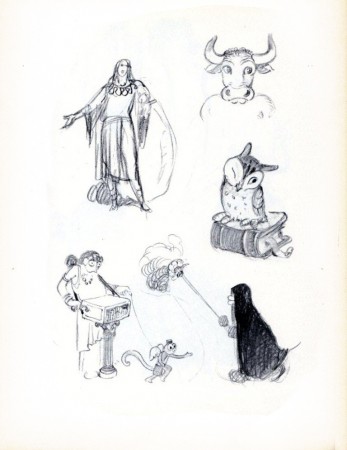

54

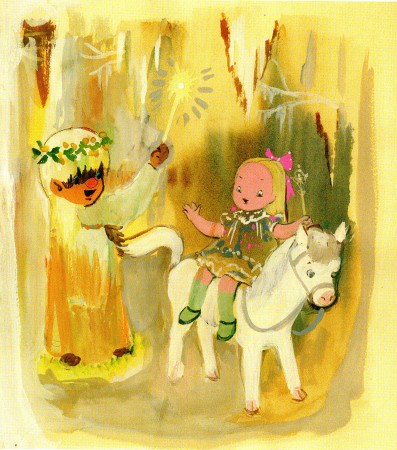

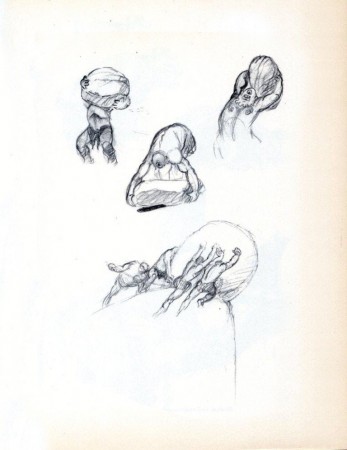

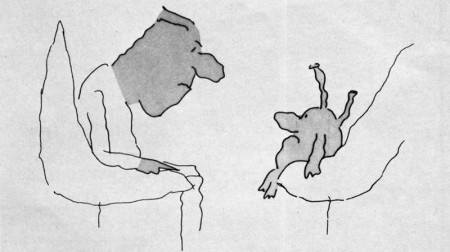

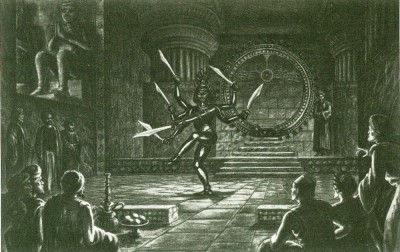

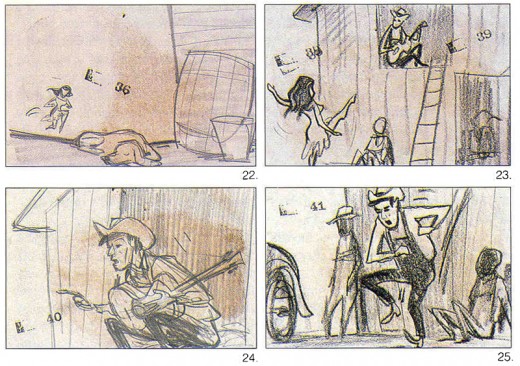

54“When Fantasia was planned,

he began playing with mythology.”

.

55

55.

56

56.

57

57Variations on a Centaur

.

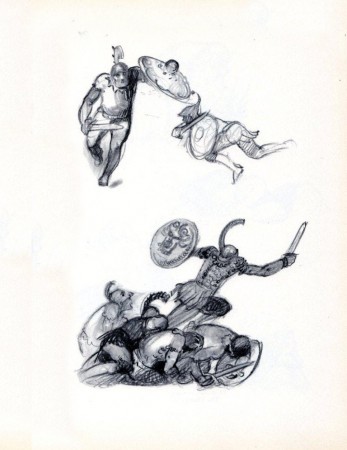

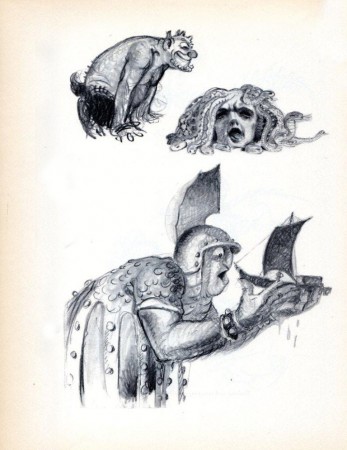

58

58Gladiators at Work

.

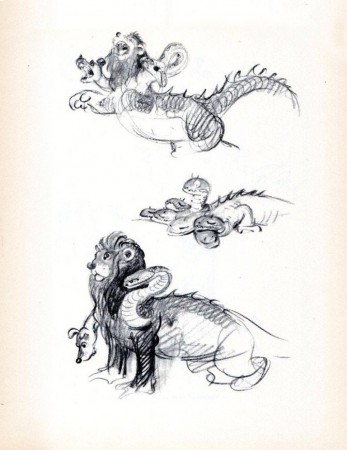

59

59The Titans

.

60

60.

61

61.

62

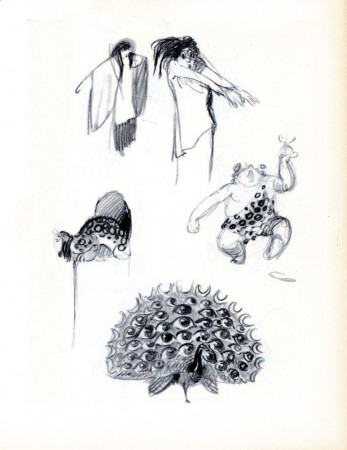

62Medusa and Contemporaries

.

63

63.

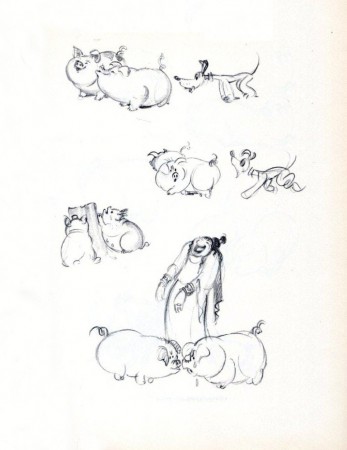

64

64Victims of Circe

.

65

65Siamese and Otherwise

.

Articles on Animation 04 Nov 2010 07:11 am

Animation Renaissance

- I enjoy rereading some of the articles in older magazines that talk about the “current state” of animation. We get to see, in hindight, what was thought of the industry during a time of change.

This article from Horizon Magazine, was written by John Canemaker in 1980, some 15 years before Toy Story and the serious explosion of cgi would take place in 1995. Many thanks to John for the article.

Animation. Renaissance ?

From Disney to independents,

animation continues to thrive.

By John Canemaker

Every few years the press alternately declares animation to be enjoying a “renaissance” or predicts the medium’s gloomy future. In the early 1970s, while Ralph Bakshi was riding a crest of popularity with the success of his cartoon features, Fritz the Cat (1972) and Heavy Traffic (1973), animation was rediscovered and pronounced “born again!” Last September, a dozen animators quit the Walt Disney studio and joined Aurora, a film production company started by three former Disney executives. Aurora is spending $7 million to produce a feature-length cartoon of a Newberry Award-winning children’s book by Robert C. O’Brien, Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIHM. Ironically, Mrs. Frisby is a mouse, and, back at the Mouse Factory (as the Disney studio was nicknamed in the 1930s), the premiere of a new cartoon feature, The Fox and the Hound, had to be postponed for six months because of the departure of one-sixth of the animation department. With the recent Disney defections, the pundits (including the New York Times) lamented the “serious gap” in Disney’s creative ranks and noted that the animation industry (and, by implication, the art of animation) had been “long depressed.”

When a dozen animators quit Walt Disney, The Fox

and the Hound, Disney’s twenty-fourth animated feature,

had to be postponed for six months.

Nothing could be further from the truth. Further, the tacit assumption that Disney and the cartoon-film industry represent the

total contemporary animation scene—or even the most important part of it—is a benighted one.

Disney, to be sure, is a great and beloved name, synonymous with animation to the general public; but Disney today is only part of an international art form comprised of a dazzling variety of styles, techniques, and content. Animation continues to thrive and flourish as it has for more than eighty years, not only in industry-run cartoon studios that produce TV series, commercials, specials, and feature-length theatrical films, but in the experimental, personal alternative forms of motion graphics created by the swelling ranks of independent animation-film and -video makers.

Regarding the current Disney situation, it is important to know that it is not an unprecedented event. At least twice before, Disney artists have left the studio en masse — and each time the result was positive for both Disney and the animation industry. In 1928, for example, Walt Disney lost rights to a cartoon character named Oswald the Rabbit; at the same time he suffered the departure of some of his key animators. Oswald was replaced by a new character—Mickey Mouse—and Disney soon enlarged his staff with a corps of artists who, within a decade, advanced character animation to a new plane. Two of the 1928 defectors went on to form the Warner Brothers cartoon studio and, later, the MGM cartoon studio.

In 1941, a large contingent of employees participated in a strike at the Disney studio that crippled production for several weeks.

In 1941, a large contingent of employees participated in a strike at the Disney studio that crippled production for several weeks.

One effect of that walkout was Disney’s eventual diversification into areas other than animation, such as live-action features, nature documentaries, television, Disneyland, and Walt Disney World. The financial security derived from such variegation allows Disney to continue making animated features. Some of the 1941 strikers formed a new studio, United Productions of America (UFA), which revolutionized the design of studio cartoons by moving away from the ultranaturalistic Disney style toward bolder graphics rooted in modern art.

An illustration from_______ Animation production manager Don A. Duckwall revealed that

Le Cuchemar du Fantoche__ despite the recent walkout at Disney, “things are going

a 1908 short by Emile Cohl.__ along beautifully. There is a resurgence of enthusiasm for the

_______________________ product and the future.” Duckwall feels the defection has “cleared the air,” and the studio has promoted peopie who are ‘ ‘taking the responsibility and doing leadership work” on TheFoxandiht Hound feature. So confident is Ron Miller, Disney executive vice-president for creative affairs, that he has scheduled the long-awaited fantasy epic The Black Cauldron as the studio’s next animated-feature project.

“Another benefit of all the publicity about the ones who left,” explains Duck-wall, “is the tremendous number of portfolios being submitted by people wanting to join our animation training program. We now have eight trainees, which is a goodly number for us.” Paula Sigman, assistant archivist at the Walt Disney Archives, confirms the positive effect of the changeover; “Instead of sounding the death knell in the animation department, this has been like a breath of fresh air—to hear the rest of the young guys tell it. There’s a new feeling of unity, of openness and willingness to communicate, of ambition. And although they’re pushed back on Fox and Hound, they’re quite excited.”

Don Bluth, the forty-two-year-old leader and spokesman for the animators who left Disney, said the resignations were “trig- ‘ gered by a dispute over training practices and artistic control.” He plans to make their feature, Mrs. Frisby, in the Disney mode (“It’s the style we love!”), but claims “the content will be different.” Mike Barrier, editor of Funnyworld, a periodical devoted to animation and comic art, has commented that “the real reason the group ! left is not that they want to go beyond what Disney has already done, but because the present studio is not ‘Disney’ enough!”

It is too early to tell if Bluth and company will succeed with their first solo venture and go on to take animated features into areas uncharted by Disney or if the Disney studio itself can succeed with this new creative challenge. The missing factor this time around is, of course, the powerful healing presence of Walt Disney himself; but certainly the competition of the two studios in the area of animated features is a healthy one for animation.

Otto Messmer (second from left) created Felix the Cat

at the Pat Sullivan studio in NY around 1919.

Computers such as Computer Creations “Videocel”

technique are being used today to cut production costs.

The last decade has seen an astonishing increase in the number of animated features produced by studios other than Disney. This trend can be traced back to The Yellow Submarine (1968) directed by George Dunning in London. A still-fresh, pop-art fairy tale of our times, starring the magical Beatles, it is a milestone film that redefined the stylistic and narrative borders of animated features. It also tapped a lucrative nontraditional cartoon-feature market composed of young singles and teenagers as well as attracting the usual family-kiddie audience.

Ralph Bakshi confirmed the existence of this “other” audience with his two aforementioned X-rated cartoons, which, though sloppy structurally, were compel-lingly earthy and poetic. They explored darker, more sensual themes and emotions than Disney dared to. Of a dozen animated features released in the last three years, several aimed toward a wider audience: Watership Down, Lord of the Rings, Allegro Non Troppo, and Dirty Duck. Internationally, there are about twenty animated features currently in production or in the planning stages.

While it can take two to three years to produce a ninety-minute animated feature, the half-hour Saturday morning children’s series on television devour huge amounts of screen footage each week. Abhorred by parent’s groups, but passively tolerated by children, Saturday morning “kidvid”—or “illustrated radio,” as veteran animator-director Chuck Jones terms it—clones on season after season with formula mediocrities such as Casper and the Space Angels, The New Schmoo, Godzilla, Fangface, Scooby’s All Stars, etc.

But in addition to the series, each year brings a number of animated specials to television. With higher per-show budgets and longer preparation time than for series, the specials’ quality level is higher. Look, for example, at the Peanuts specials, The Doonesbury Special, Everybody Rides the Carousel, The Pumpkin Who Couldn ‘t Smile, and The Hobbit, among others. As if this were not enough to keep animators busy, the PBS educational series (Sesame Street, Electric Company, 3-2-1 Contact) solicit brief, informational, animated spots from many studios and individual film makers. TV commercials often use animation when their selling approach delves into the fantastic, as in the surreal Levi’s spots by Robert Abel & Associates and the virtuoso, action-packed Jovan: The Power by Richard Williams Studio.

Today, animation is not just for kiddie cartoons.

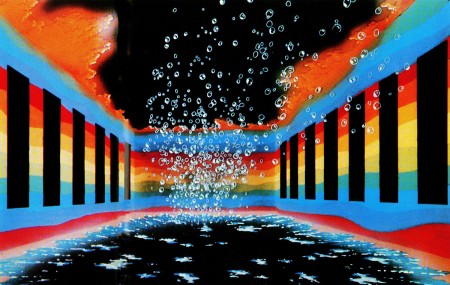

The Oriental Nightfish was a short developed to

be used in the concerts of the rock group, Wings.

The above outlets for animation, theatrical features, and television are dominated by “the industry”—films made by a group of artists and craftspeople in a studio using mostly cartoon designs. It is this work that is most accessible to the general public, both actually and aesthetically. But there is another force working in animation, much less well known but gaining each year in terms of recognition and in avenues of distribution and exhibition. This is a large, vital international network of independent animation-film and -video makers who, freed from profit-motive considerations, explore alternative ways of communicating, interpreting, and expressing themselves and the world through animation. Many work for years on a short film; some subsist on canvas, or a sculptor to clay.

“Because it depends so heavily on technical expertise, we believe the medium of animation enters into the realm of art only when it has a strong personal imprint,” said George Griffin, a leading experimentalist. Griffin, whose inventive films explore the “act of art-making” in a variety of techniques from flip-books to Xeroxed graphics, last year privately published an anthology of new American independent animators.

Titled Frames, the book represents the work of more than seventy animators in this country alone. Their techniques and graphic signatures are lavishly diverse: some artists work in collage (Frank Mouris), others use optical printing (Peter Rose, Anita Thacher), or drawing on film (Steve Segal), direct three-dimensional manipulation (Caroline Leaf, Eli Noyes), rotoscoping (Mary Beams), drawing on paper (Kathy Rose, Dennis Pies), and “cel” animation

(Suzan Pitt, Sally Cruickshank).

To the independents, Griffin notes, “experimental film is not about what a work looks like, but what it does. How it invents its own form, makes its own rules, while stretching the definition of the medium of animation.”

Slowly, the work of these individualistic artists is reaching a larger public. The 1978 New York Film Festival featured a showcase of new animation, as did the USA Dallas Film Festival and the Los Angeles Film Exposition. Independent animators from around the world consistently win top prizes in animation festivals in Zagreb, Yugoslavia, Annecy, France, and Ottawa, Canada. Cable and public television stations book these works, thus introducing them to a wide scope of interested viewers. For two years PBS sponsored the International Animation Film Festival series, which booked many nontraditional animated films. A feature-length compilation, The Fantastic Animation Festival, was distributed theatrically and found particular favor on this country’s college campuses. More and more nontheatrical distributors, who sell and rent films to schools, universities, and library collections, are responding to their patrons’ interest in the new animation and are signing many experimental animators to contracts.

A color model from the pop-art animated feature

The Yellow Submarine (1968) indicated to the

opaquers which colors to use in the final frames.

In the beginning, naturally, all animation was experimental. Although no one knows who first discovered the magic inherent in the camera’s ability to shoot single frames of film, three pioneers defined the animation medium by experimenting and inventing the basic tools still in use today. James Stuart Blackton, a cartoonist-reporter for the New York Evening World, made Humorous Phases of Funny Faces in 1906 and used animation to promote himself and his film company, Vitagraph. The Parisian Emile Cohl made or contributed over 250 animated sequences starting in 1908; his series, The Newly weds, made in America and based on a popular American comic strip, was very influential in identifying the animated-cartoon genre with the weekly comic strip in the public’s mind. Winsor McCay, the most gifted cartoonist-draftsman of his age, tirelessly explored the possibilities of line and motion in his ten films including Little Nemo (1911) and Gertie the Dinosaur (1914)) and promoted animation on his chalk-talk vaudeville tours.

It was in 1914 that American cartoonist John Randolph Bray turned animation into a business. Bray, who might be termed the Henry Ford of animation, organized a staff of specialists doing assembly-line tasks in cartoon studios. He cannily took out patents on certain work- and time-saving inventions (the most important being clear Celluloid acetate sheets called “cels”) which enabled large numbers of films to be produced in series. Thus began the industry of animation, the mass production of cartoon films starring a parade of internationally famous characters. Often the characters came from the newspaper strips, like Mutt and Jeff. But Felix the Cat, created by Otto Messmer at the Pat Sullivan studio in New York circa 1919, was made for the screen —the first creature to express an individuality in drawings that move. Felix’s unique design and, most important, his personality profoundly influenced Walt Disney’s famous animated rodent.

The experimentalists continued to work by themselves creating films that widely diverged from the commercial mainstream. Often the influence of the avant-garde was felt in the studio product, but it was adapted into the “accepted” version —reduced for the conditioned taste of the public who rarely experienced the strong individuality of the original source. (A prime example is the preliminary work the German abstractionist Oskar Fischinger contributed to a sequence in Disney’s Fantasia [1940].) Strong, beautiful, short films of singular vision were made by animators in Europe during the period 1920-1935 and in America in the 1940s and 1950s. Among these animators were Len Lye who painted directly onto film, Lotte Reiniger who used cut-out silhouettes, Alexander Alexeiff who worked in pinscreen, John Whitney with his computer works, and Jordon Belson whose specialty was video projects.

Interest in animated films has been enhanced by a wave of printed supporting material: in the last five years, scores of periodical articles and eighteen books on all aspects of animation have been published. Some of the books deal with cartoon nostalgia (The Fleischer Story), some focus on technology and technique (Visual Scripting), others on a particular genre (Puppet Animation in the Cinema), or historical perspective (Experimental Animation: An Illustrated Anthology). Six new books in the works aim toward publication within two years.

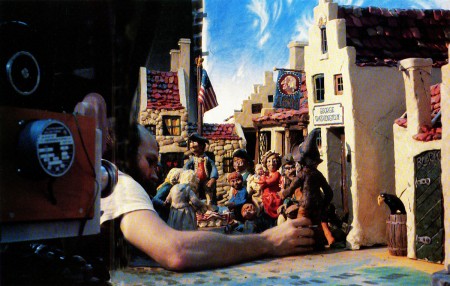

Oscar-winning Will Vinton, one of today’s innovative animators,

adjusts characters from Rip Van Winkle, a half-hour clay animation.

The current issue of the American Film Institute’s Guide to College Courses in Film and Television shows that more than sixty major American colleges feature animation workshops and/or film-tape appreciation courses in their curriculum. Most celebrated is the California Institute of the Arts, which divides its animation work-shops into an experimental group under veteran designer Jules Engel and a character-animation section headed by Disney shorts-director Jack Hanna. Many of En-gel’s students have become some of today’s most exciting independent animators and several of Hanna’s students have found their ways to jobs at Disney or other cartoon studios.

The cross-pollination of ideas gained by the proximity of the two Cal Arts animation courses is a good omen and symbol for the future of animation. The art today is undeniably vigorous and varied; computers are being developed to enhance productivity and cut production costs (such as Computer Creation’s “VideoCel” technique). The growing visual sophistication of audiences and the international exchange of ideas between the avant-garde and the industry, the new technology outlets for films and tapes, such as video-disks and home-tape consoles, make the future of animation exciting and unlimited.

- Who’s Watching Cartoons?

Most viewers are children, but there is a healthy contingent of adults, particularly for reruns of old theatrical shorts.

Tim Roberts, head of creative services at New York’s Channel 5, notes that his station receives a “steady number of phone calls from adult viewers” inquiring as to the titles of the shorts shown in the daily series. “Some people want to see a certain favorite, like Bugs Bunny or Woody Woodpecker, but most of the callers have videotape machines and want to tape certain films to add to their cartoon collections.”

Last November Channel 5 presented a half-hour Cartoon Film Festival for one week in prime time (8 P.M.), with interesting viewer results. Diane Sass, vice-president of marketing and research at Channel 5, consulted the Arbitron report, a book of TV viewer demographics and noted that the festival received a ten rating, which she said is “very good. The usual programming in that time slot is a game show, ‘Crosswits,’ which usually pulls a six to seven rating.” More interesting was the breakdown of viewers according to age. The Cartoon Festival, said Sass, “had a total viewing audience of 1,217,000. Of that 438,000 were kids, 225,000 were teenagers—age twelve to seventeen—and the majority of viewers, 554,000, were adults, eighteen-plus.”

A guest fellow at Yale University teaching animation history, John Canemaker is the author of The Animated Raggedy Ann & Andy—An Intimate Look at the Art of Animation: Its History, Techniques and Artists and makes animated films and documentaries about animation.

Articles on Animation &Richard Williams 26 Oct 2010 07:58 am

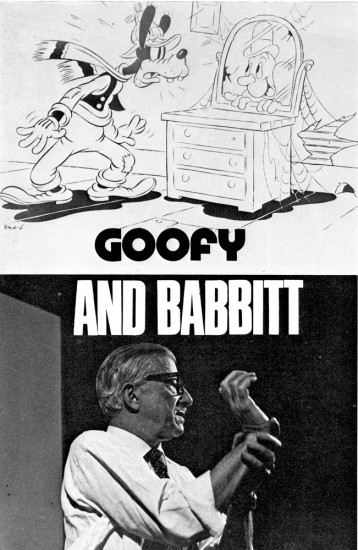

Goofy and Babbitt

- The following article was printed in Sight and Sound, Spring 1974 issue. It begins with Art Babbitt‘s 1934 character analysis of Goofy and is followed up with Dick Williams’ 1974 analysis of Art Babbitt. Dick’s comments aren’t always on the money: Babbitt animated a good share of Rooty Toot Toot, but he didn’t animate most of the film. (As a matter of fact, Grim Natwick’s animation of Nellie Bly on the witness stand is, to me, the standout animation of the film.) Babbitt animated the bartender and the trial lawyer.

- The following article was printed in Sight and Sound, Spring 1974 issue. It begins with Art Babbitt‘s 1934 character analysis of Goofy and is followed up with Dick Williams’ 1974 analysis of Art Babbitt. Dick’s comments aren’t always on the money: Babbitt animated a good share of Rooty Toot Toot, but he didn’t animate most of the film. (As a matter of fact, Grim Natwick’s animation of Nellie Bly on the witness stand is, to me, the standout animation of the film.) Babbitt animated the bartender and the trial lawyer.

You can see the film on YouTube, here.

I previously posted the first half of this article with all the Goofy model sheets that it accompanied. You can see that here.

(The original, unfortunately, contains the “N” word instead of “coloured boy” as this edited version offers.)

.

Goofy and Babbitt

by Art Babbitt and Richard Williams

.

Two of the great artist-animators of the golden years of the Disney Studios, Art Babbitt and Grim Natwick, were working and teaching at the Richard Williams Studios in London last summer. To parallel Babbitt’s 1934 character analysis of Goofy, which has not previously been published, Richard Williams gives an impression of the animator himself.

Two of the great artist-animators of the golden years of the Disney Studios, Art Babbitt and Grim Natwick, were working and teaching at the Richard Williams Studios in London last summer. To parallel Babbitt’s 1934 character analysis of Goofy, which has not previously been published, Richard Williams gives an impression of the animator himself.

CHARACTER ANALYSIS OF THE GOOF—JUNE 1934

In my opinion the Goof, hitherto, has been a weak cartoon character because both his physical and mental make-up were indefinite and intangible. His figure was a distortion, not a caricature, and if he was supposed to have a mind or personality, he certainly was never given sufficient opportunity to display it. Just as any actor must thoroughly analyse the character he is interpreting, to know the special way that character would walk, wiggle his fingers, frown or break into a laugh, just so must the animator know the character he is putting through the paces. In the case of the Goof, the only characteristic which formerly identified itself with him was his voice. No effort was made to endow him with appropriate business to do, a set of mannerisms or a mental attitude.

It is difficult to classify the characteristics of the Goof into columns of the physical and mental, because they interweave, reflect and enhance one another. Therefore, it will probably be best to mention everything all at once.

Think of the Goof as a composite of an everlasting optimist, a gullible Good Samaritan, a half-wit, a shiftless, good-natured coloured boy and a hick. He is loose-jointed and gangly, but not rubbery. He can move fast if he has to, but would rather avoid any over-exertion, so he takes what seems the easiest way. He is a philosopher of the barber shop variety. No matter what happens, he accepts it finally as being for the best or at least amusing. He is willing to help anyone and offers his assistance even where he is not needed and just creates confusion. He very seldom, if ever, reaches his objective or completes what he has started. His brain being rather vapoury, it is difficult for him to concentrate on any one subject. Any little distraction can throw him off his train of thought and it is extremely difficult for the Goof to keep to his purpose.

Yet the Goof is not the type of half-wit that is to be pitied. He doesn’t dribble, drool or shriek. He is a good-natured, dumb bell what thinks he is pretty smart. He laughs at his own jokes because he can’t understand any others. If he is a victim of a catastrophe, he makes the best of it immediately and his chagrin or anger melts very quickly into a broad grin. If he does something particularly stupid he is ready to laugh at himself after it all finally dawns on him. He is very courteous and apologetic and his faux pas embarrass him, but he tries to laugh off his errors. He has music in his heart even though it be the same tune forever, and I see him humming to himself while working or thinking. He talks to himself because it is easier for him to know what he is thinking if he hears it first.

His posture is nil. His back arches the wrong way and his little stomach protrudes. His head, stomach and knees lead his body. His neck is quite long and scrawny. His knees sag and his feet are large and flat. He walks on his heels and his toes turn up. His shoulders are narrow and slope rapidly, giving the upper part of his body a thinness and making his arms seem long and heavy, though actually not drawn that way. His hands are very sensitive and expressive and though his gestures are broad, they should still reflect the gentleman. His shoes and feet are not the traditional cartoon dough feet. His arches collapsed long ago and his shoes should have a very definite character.

Never think of the Goof as a sausage with rubber hose attachments. Though he is very flexible and floppy, his body still has a solidity and weight. The looseness in his arms and legs should be achieved through a succession of breaks in the joints rather than through what seems like the waving of so much rope. He is not muscular and yet he has the strength and stamina of a very wiry person. His clothes are misfits, his trousers are baggy at the knees and the pant legs strive vainly to touch his shoe tops, but never do. His pants droop at the seat and stretch tightly across some distance below the crotch. His sweater fits him snugly except for the neck, and his vest is much too small. His hat is of a soft material and animates a little bit.

It is true that there is a vague similarity in the construction of the Goof’s head and Pluto’s. The use of the eyes, mouth and ears are entirely different. One is dog, the other human. The Goof’s head can be thought of in terms of a caricature of a person with a pointed dome—large, dreamy eyes, buck teeth and weak chin, a large mouth, a thick lower lip, a fat tongue and a

bulbous nose that grows larger on its way out and turns up. His eyes should remain partly closed to help give him a stupid, sloppy appearance, as though he were constantly straining to remain awake, but of course they can open wide for expressions or accents. He blinks quite a bit. His ears for the most part are just trailing appendages and are not used in the same way as Pluto’s ears except for rare expressions. His brow is heavy and breaks the circle that outlines his skull.

He is very bashful, yet when something very stupid has befallen him, he mugs the camera like an amateur actor with relatives in the audience, trying to cover up his embarrassment by making faces and signalling to them.

He is in close contact with sprites, goblins, fairies and other such fantasia. Each object or piece of mechanism which to us is lifeless, has a soul and personality in the mind of the Goof. The improbable becomes real where the Goof is concerned.

He has marvelous muscular control of his bottom. He can do numerous little flourishes with it and his bottom should be used whenever there is an opportunity to emphasise a funny position.

This little analysis has covered the Goof from top to toes, and having come to his end, I end.

ART BABBITT

.

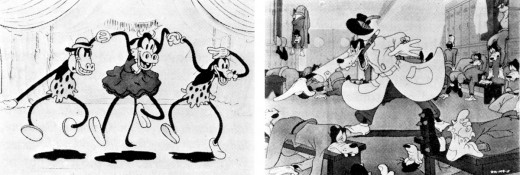

‘Orphans’ Benefit’ (1934). The Goof after Babbitt: ‘How to Play Football’ (1944)

.

CHARACTER ANALYSIS OF THE ANIMATOR—JANUARY 1974

.

He is a funny mixture. He has the bearing of a Marines sergeant (which he was during the war, after leaving Disney following the strike in which he was the principal figure); but he has the mind of a Viennese doctor—which is what he wanted to be. In his youth he always wanted to go to Vienna and study psychiatry; but he couldn’t because he was a poor boy from Iowa with relatives to support. So he went to New York and taught himself to be a commercial artist; and gradually got into animation—starting, I think, through Paul Terry.

Arriving at Disney, he was one of four animators on Three Little Pigs; and of course that was the great breakthrough in personality animation. Then he animated Goofy, and worked on shorts in preparation for Snow White. In the first Disney feature he animated the Queen where she was beautiful, up to the point where she is transformed into the hag. In Pinocchio he did most of the animation of Gepetto, and Gepetto almost looks like him. He had that sort of versatility, to characterise the horrid queen or the sentimental wood-carver. Then in Fantasia he did primarily the mushroom dance; but he was animation director on a lot of other material. On Dumbo he was a supervising animator.

The strike came in 1941. Babbitt had had a personal confrontation with Disney over the low payment of assistants; and Disney ill-advisedly fired him, giving as a reason his u-nion activities. This was directly in contravention of the Wagner Labor Relations Act, and the

U-nion took a strike vote. Babbitt fought Disney through all the courts; and they were obliged to reinstate him, for an uncomfortable period during which Disney would pass him in the corridor without speaking or even looking at him. He stood it for a year; then he quit.

After the war he and Natwick were with Hubley at UPA – Art did most of Rooty Toot Toot. Later he was with Hanna and Barbera. I had heard about him for years before I finally came to meet him. He had seen some of our work, and though he’d not exactly liked it (it was pretty slick) had decided that ‘here are some people trying to do an honest job, and that’s the first time I’ve seen that in ten years.’ He wasn’t all that impressed, but he went to the heart of it.

It turned out he was very interested in teaching people. He was thinking of writing a book to instruct people; and he’d done a course at U.S.C. of which we had copies of students’ notes. As it happened he had a fire at his house and all his own lecture notes were burned. So we were able to send him these student notes. He said they were all wrong; but it was something. Then finally I asked him straight out if he would come over and teach us, because we had gone as far as we could go on our own.

He is a great teacher. He has an astonishing lucidity. Most animators are completely incoherent; they are unable to tell you what they are doing. But Art doesn’t have any difficulty in showing you how a thing works. He just says: ‘Did you notice that that worked because such and such . . . and Hubley did this thing this way?’ And when Art says something is wrong, he’s invariably right—if you want it to work. He’ll say: ‘If you want the wheel to go round, this is the way to make it go round. This is the way to make a cypher for making it go round. And this is another way they used to give the impression of it going round. And your problem is that you are to do it with square wheels.’ He is completely eloquent. I’m sure that at Disney they created a language about what they were doing; and I’m equally certain that it was he who largely gave a verbal form to it, so that the others could understand it. He has a surgeon’s mind; which, I gather, Disney had also.

When he taught in our studio he insisted that people take the course. He started off by saying: ‘Please, in my lectures, do not be British. Be crude, be revolting; ask stupid questions. Please do not be polite; otherwise I’m wasting my time.’ He’s as tough as nails; yet it literally hurt him when someone couldn’t get a thing right, couldn’t understand it. Then when they got it right, he would dissolve in warmth. His patience was beautiful.

He knows so much about everything— about symphony construction, about the visual arts, about everything to do with the medium. He once decided he would teach himself to play the piano. He’s the one in the famous Disney story —when he was learning to play the piano, and Disney said, ‘What are you—some kind of fag or something ?’ He hated Disney for that, because he wanted to understand music to apply it to animation. He knew that Fantasia or something like it was inevitable.

On the course he told us: ‘An animator must possess a curiosity about everything that exists or moves . . . must be a student of everything that might or does exist. From the shiver of a blade of grass—affected by an invisible breeze—to the behaviour of a starving hobo eating the first steak he has had in years. From a baby, tentatively trying to walk for the first time—to an elephant doing the can-can.’

I just saw Fantasia again and the Dance of the Mushrooms; and he was doing things there—treating perspective as a subsidiary action—that no one else was doing at the time. And he does not do it by feel, as I might, but because he’s worked it all out and analysed it. On the course he would say: ‘This is the cliché. This is the formula. And this is how to break it.’ He would set up the rules and then make you bust them.

And as well as the analytical capacity and the intelligence is the ability to start from basics—to deal with the most minute detail. He knows how the labs process the material; the way celluloid is made, the way the pencil is made. People who know that kind of thing don’t usually have artistic ability into the bargain. The ability to discern basics extends to his gift for statements that seem entirely simple and yet reveal vital things one often has not recognized : ‘We must learn to create movements if necessary that are caricatures of reality— but done with such guile they are always convincing.’ ‘We must expand our sense of caricature—to realise that we are not simply exaggerating external appearances— but more important, the inner character, the mood, the situation. A caricature is a satirical essay, not just doubling the size of a bulbous nose.’

A Babbitt scene from Williams’ Cobbler and the Thief.

My portrait is idolatry, maybe; but how do you not idolize someone who after more than forty years work in his and your medium still can find it ‘wonderful, exciting, exacting … A medium that has barely been discovered, let alone explored. A medium that can be an art form that encompasses practically all other art forms. A medium that can gratify aesthetically, that is not earth-bound, that can be an invaluable aid in teaching everything from elementary chemistry to the Theory of Relativity.’

RICHARD WILLIAMS

Animation &Articles on Animation &Disney 22 Oct 2010 07:46 am

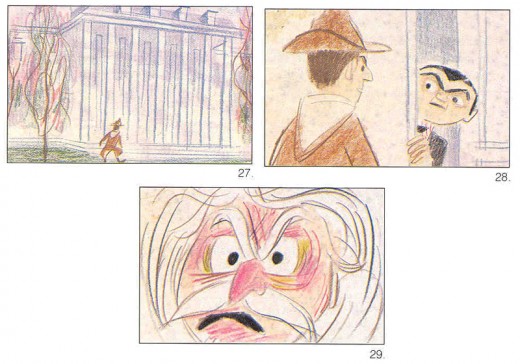

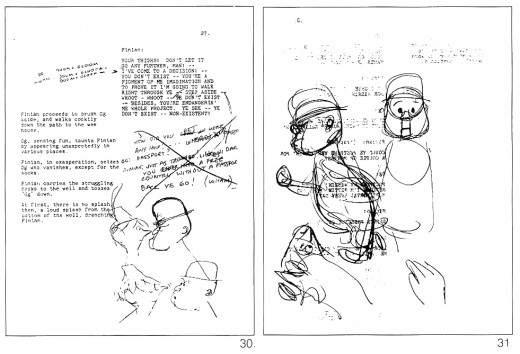

Oskar Fischinger at Disney

The following article appeared in the 1977 Anmation Issue of MILLIMETER MAGAZINE as edited by John Canemaker. (Some of those commercial magazines were just excellent back then, and we never seemed to notice or properly appreciate them.)

or, Oskar in the Mousetrap

by William Moritz

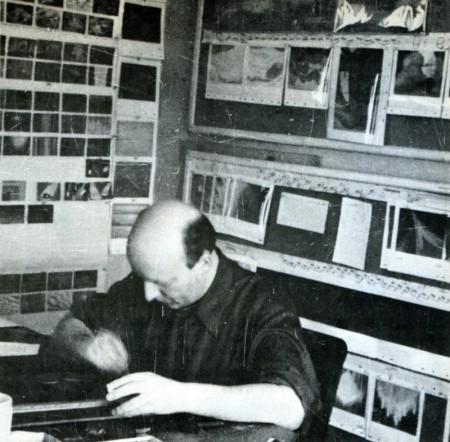

Oskar Fischinger at work at the Walt Disney Studio in 1939

Courtesy of Mrs. Elfriede Fischinger, all rights reserved

The official Disney account of the origin and making of FANTASIA has been told many times — from the early press releases, programs, and Feild’s wide-eyed, idolatrous book from 1942, THE ART OF WALT DISNEY (all united by the “official studio policy”/ mannerism of discussing primarily Walt Disney himself as if he had conceived and designed the films almost single-handedly), down to the more reasonable, carefully-researched materials published recently, such as the article by Disney archivist David R. Smith for MILLIMETER’S 1976 animation issue, and Bob Thomas’ new biography, WALT DISNEY, AN AMERICAN ORIGINAL.

I have already given an outline of another side to this story in my bio-filmo-graphy of Oskar Fischinger (FILM CULTURE 58-59-60-, 1974, pp. 61-65), but Fischinger’s tale bears re-telling since clearly a full understanding of the matter lies in discovering all that went on behind the scenes and in Fischinger’s heart-of-hearts.

Oskar Fischinger, who was a year older than Walt Disney, devoted his major energies throughout his life to abstract animation. In the early Twenties, while the Disney brothers assembled Ub Iwerks and a remarkable collection of talents to form an animation studio for production of Alice and Oswald cartoons, Fischinger, working on his own, struggled with radical experiments in non-objective imagery — from sliced wax to multiple-projector light shows. Even before sound film became available, Fischinger synchronized his abstract films to phonograph records and live musical accompaniments, because he found that the analogy with music (i.e., abstract noise well-developed and widely-accepted non-objective art form) helped audiences to grasp and accept the nature and meaning of his “universal”, absolute imagery. Oskar never meant to illustrate music, and often screened his “sound” films silently for already sympathetic audiences.

At the same time Iwerks/Disney’s Mickey Mouse and SILLY SYMPHONIES (and clever mass-marketing techniques) began to gain world-wide acclaim for the Disney Studios, Fischinger also enjoyed a moderate international renown as well, with his black-and-white STUDIES playing as novelty shorts with features from Uruguay to Japan. And while Disney began to win Academy Awards for his shorts, Fischinger also won grand prizes at film festivals in Brussels and Venice.

By 1935, Fischinger had made at least 35 abstract animated shorts, and stated as his New Year’s wish in the Berlin trade paper FILM KURIER that he wanted most to create an animated feature composed entirely of non-objective imagery and diverse music (he had used jazz, toyed with experimental electronic music and his own synthetic drawn soundtracks as well as classical music).

A scene from Walt Disney’s FANTASIA (1940)

Unfortunately for Fischinger, political events militated against him for much of his life, but he still produced a body of work that plays increasingly in theatres and museums as several full-evening programs.

The Nazi government had banned abstract art as degenerate, and was officially outraged that Fischinger’s COMPOSITION IN BLUE won festival prizes. Oskar in turn happily accepted a contract with Paramount and sailed for Hollywood in February, 1936, never to return to Germany. Unfortunately he spoke no English and encountered tremendous, frustrating difficulties in his early studio jobs. He assumed Paramount wanted him to pursue the style of his prize-winning COMPOSITION IN BLUE, but instead they wanted more representation and cuter work like his Muratti cigarette commercials. After he had completely painted and photographed a color abstract sequence (later called ALLEGRETTO), the director Mitchell Leisen insisted the piece be re-done in black-and-white with representational images of musical instruments and other pop trick effects overlayed. The resulting studio version disgusted Fischinger and he quit Paramount only half-a-year after he started there.

His second American film, AN OPTICAL POEM, made for MGM under William Dieterle’s aegis, proved one of Oskar’s finest works, and though not exactly a box-office sensation, played prestige bookings with first-run features, and was mentioned by one critic as a likely Oscar nominee (which caused Fischinger to quip, “Why bother giving me Oscar? I am Oskar!”).

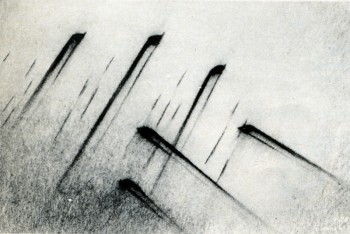

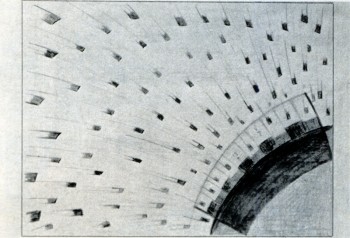

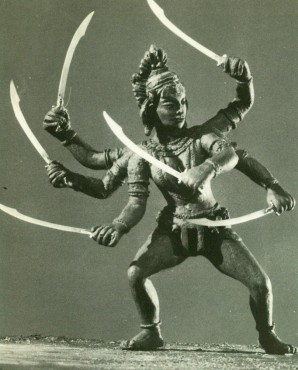

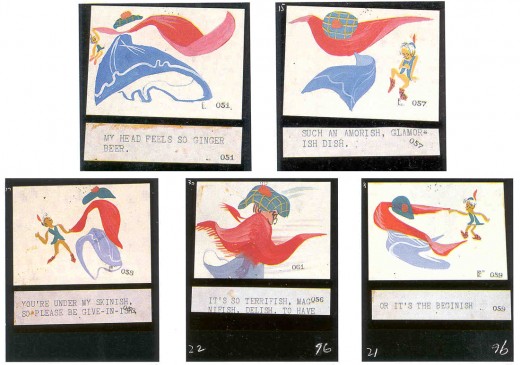

A Fischinger pencil sketch (with numerical

motion-phase breakdowns) for “Toccata and

Fugue” section of Disney’s FANTASIA.

After his MGM option was not picked up, Fischinger drove to Detroit and New York seeking backing for a feature-length animated film based on Dvorak’s “NEW WORLD” SYMPHONY, which he hoped to be able to present at the World’s Fair. Although this project never materialized, Oskar dallied in New York because he discovered a new ambiance there: unlike Hollywood, he was treated as a major artist in New York, invited to screen his films and exhibit paintings, dine with leading filmmakers, critics and painters, spend weekends at the country estate of Guggenheim Foundation curator Hilla Rebay. He returned to Hollywood only when his agent cabled that he had a job for him at Disney.

What a rude shock Fischinger received upon his return! Already in Berlin, Oskar had been attracted to Leopold Stokow-ski’s grand orchestral arrangements of Bach and had tried to get music rights to some of his pieces. When Fischinger found that Stokowski was his co-worker at Paramount, he once again proposed a series of shorts or an anthology feature. Stokowski was initially quite receptive and wrote Fischinger (October 9, 1936, on Paramount stationery), “I should be very happy if we could work together — you doing what is seen, I doing what is heard.” And he received from Fischinger such elaborate ideas as (November 15, 1936, in German):

“If you are here at Christmas, I’d like to make a full-length shot of you in such a way that the visual part of the film could begin with you conducting the first few bars of the music, and then the eyes of the viewer would glide with a movement of your hands off into endless space where the rest of the visuals would unfold. ”

Nevertheless, after several conferences, Stokowski decided that the project would be too expensive and complex for Oskar to animate alone, and suggested that they seek support from a major studio, perhaps Disney. Fischinger held little hope for satisfactory help from Hollywood, especially after his experiences, and furthermore he knew from gossip that Disney, despite his successes, was under severe strain, borrowed and mortgaged to the hilt. And Oskar’s worst fears were seemingly confirmed when he returned to Hollywood in November, 1938, to find that while Stokowski was being honored as Disney’s major collaborator on “The Concert Feature”, Fischinger was being hired for $60-per-week (Paramount had paid him $250) as a “Motion picture cartoon effects animator”.

Fischinger accepted the job since work was scarce and he had four children to support, but for him the Disney episode proved a nightmare which so angered him that he conspicuously avoided talking about it in later years. Only once did he write a note on his Disney adventure (in a letter to a friend), and it expressed well his chagrin:

“I worked on this film for nine months; then through some “behind the back” talks and intrigue (something very big at the Disney Studios) I was demoted to an entirely different department, and three months later I left Disney again, agreeing to call off the contract. The film “Toccata and Fugue by Bach” is really not my work, though my work may be present at some points; rather it is the most inartistic product of a factory. Many people worked on it, and whenever I put out an idea or suggestion for this film, it was immediately cut to pieces and killed, or often it took two, three or more months until a suggestion took hold in the minds of some people connected with it who had their say. One thing I definitely found out: that no true work of art can be made with that procedure used in the Disney Studio.”

At first, Fischinger threw himself whole-heartedly and good-naturedly into the project. He gave prints of his films to be screened weekly for the entire Disney staff, so his influence was pervasive (spilling over onto other films like DUMBO, the South American films, and PINOCCHIO, for which Oskar actually animated the magic wand of the Blue Fairy). In the mimeographed transcript of the story meeting for February 28, 1939, Walt Disney says (p. 1): “Everything that has been done in the past on this kind of stuff has been cubes, and different shapes moving around to the music. It has been fascinating. From the experience we have had here with our crowd — they went crazy about it. If we can go a little further here and get some clever designs, the thing will be a great hit. I would like to see it sort of near-abstract, as they call it — not pure. And new.”

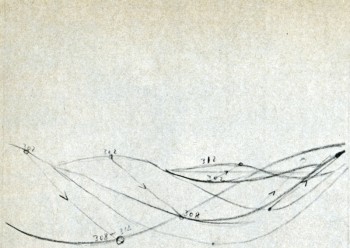

Fischinger’s numerical motion-phase breakdown

for “the Wave” scene in “Toccata and Fugue”

section of FANTASIA.

© Fischinger Trust, all rights reserved.

Perhaps because of the uneasy proximity of Fischinger, Walt exhibits a certain suspiciousness about abstraction, accompanied by a rather defensive attitude towards the prospective audience.

January 24, 1939, p. 2:

Walt Disney: You should give something that the audience will recognize. I don’t think the average audience will fully appreciate the abstract; but I may all be wrong —

Stokowski: Yes, they may be way ahead of us.

or, January 24, 1939, p. 7:

Walt Disney: What will Bach lovers think of this?

Stokowski: They will be against it, I think; but the public will love it.

Walt Disney: Well, the general idea here looks good to me. I only wonder if we’re going a little too gypsy in the color—

or, February 28, 1939, p. 5:

Walt Disney: If we can get a little connection behind this, the public will take to it. It would be better than some wild abstraction that you can’t get anything out of at all. Right there is where the music sounds most like an organ, so the public decides it represents an organ.

or, February 28, 1939, p. 8:

Walt Disney: Do you think we ought to have pictures in mind through this thing? Then we won’t get a conglomerate mess — an abstraction.

or, JuneS, 1939, p. 1:

Walt Disney: There’s a theory I go on that an audience is always thrilled with something new, but fire too many new things at them and they become restless.

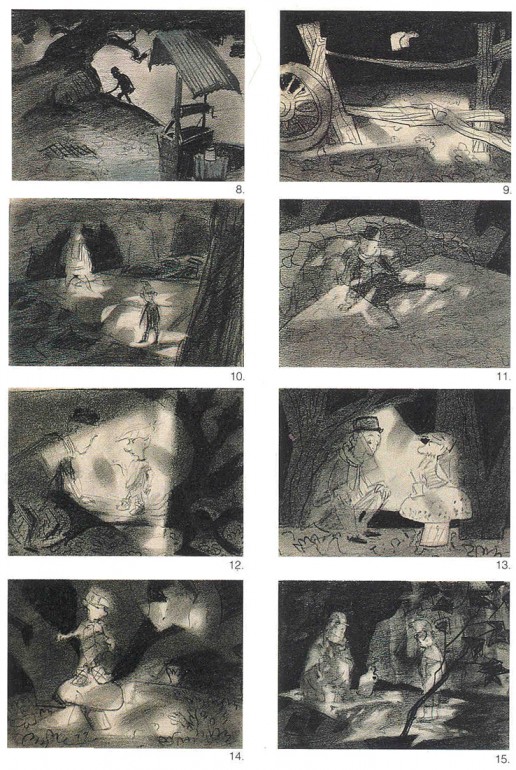

The “wave” scene as it appears in FANTASIA.

©Walt Disney Productions.

Fischinger’s assertions about the unhealthy competitive committee work at Disney would seem to be borne out by the conference notes in which we see during nine month’s of work on the “story” incredible floundering, dreary discussions and re-discussions of each scene, groping and pushing without any controlling factor besides making an entertaining film.

Because he knew little English, Fischinger never spoke up during these story conferences (neither did Kay Nielsen), and further became the butt of endless practical jokes on the part of his jealous co-workers. Some fun-loving boys of the Disney staff, unwilling to deal maturely with the plight of a refugee artist, pinned a swastika on Oskar’s office door September 1, 1939, the day the Nazi armies invaded Poland. Fischinger applied for a release from his contract and after two months of red tape, terminated his employment at Disney, October 31, 1939, Halloween.

Fischinger kept about 100 of his sketches and drawings for the Bach “Fugue”, including some lovely pastels showing melting meanders and supple lozenges much as they appear in the final FANTASIA, as well as half-a-dozen beautiful images that were probably never realized on film. The most extensive unit involves twelve poster-color and 60 pencil drawings (with numerical motion-phase breakdowns) that detail the sequence in which alternating left-and-right-hand “waves” surge toward the viewer. While this turned out to be one of the more impressive moments in the Disney film, a comparison with Oskar’s original sketches shows how much more powerful, subtle and imaginative the sequence might have been if Fischinger’s intentions had been honored — with his choice of monochromatic turquoise and celadon hues for the (somewhat flatter) wave motion overlayed with scintillating geometric figures in browns, Chinese red, and graduated yellow/oranges, all of the elements flowing cogently and vigorously out of each other, as opposed to the simplified Disney image of fat, melon-ribbed waves slightly off-balance in shades of flagrant purple distractingly at constrast in “realism” to the (needlessly) clouded sky behind. All in all, the Disney version of the “Fugue” seems painfully close to the Paramount adulteration of ALLEGRETTO.

Much of Fischinger’s work seems entirely lost. After looking at some of Oskar’s sketches (August 21, 1939, p. 3), Walt Disney comments, “I think the contrast of black and white, and then a little color coming in, would stand out. ” but I don’t think such an effect reached the final version of FANTASIA. Evidently some of Fischinger’s own animation was filmed at least in the pencil test stage, since after viewing some material on a moviola Disney comments (August 21, 1939, p. 7) “Oskarhas a pulsing effect in his test.”

To me, Disney was actually the loser in the matter. Each year Fischinger’s genius and the sincere consistencly of his films becomes more widely acknowledged, while every year the moments of unbearable kitsch, lapses of taste, questionable values, and hodge-podge of stylistics that mar most of the Disney Studio product are becoming more obvious to everyone. For all its considerable virtues of self-parody, rich color and design, etc., FANTASIA falls easily victim to its own shortsightedness so that the burlesque of Bozetto’s ALLEGRO NON TROPPO carries devastating bite.

At least Fischinger had a few of the last laughs in the matter. After leaving the Disney Studios, he devised a set of seven superb collages, among his most charming and highly prized works, showing Mickey and Minnie Mouse (cut from comic books) “reacting” to reproductions of abstract paintings by Kandinsky and Bauer (cut from a 1938 Guggenheim Museum catalogue). And years later, when Disney made the documentary TOMORROW THE MOON, they inadvertantly honored Oskar by using a clip of his pioneer special effects of the rocket launching from Fritz Lang’s FRAU IM MOND, made a quarter of a century earlier.

Daily post 01 Oct 2010 05:31 am

Book Signing & SVA Exhibition

Here’s a press release that came from the Museum of Modern Art re a show that John Canemaker will be hosting tonight in celebration of his recent book, Two Guys Named Joe: Master Animation Storytellers Joe Grant and Joe Ranft.

- The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters

Academy Award–winning animation filmmaker and author John Canemaker presents an illustrated lecture based on his new book Two Guys Named Joe (Disney Editions, 2010), an immensely entertaining and insightful portrait of the legendary animation storytellers Joe Grant (1908–2005) and Joe Ranft (1960–2005).

Academy Award–winning animation filmmaker and author John Canemaker presents an illustrated lecture based on his new book Two Guys Named Joe (Disney Editions, 2010), an immensely entertaining and insightful portrait of the legendary animation storytellers Joe Grant (1908–2005) and Joe Ranft (1960–2005).

In his long career at Disney, Grant helped create such masterworks as Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), Pinocchio (1940), Fantasia (1940), Dumbo (1941), Make Mine Music (1946), and Lady and the Tramp (1955), as well as more recent hits like Beauty and the Beast (1991) and The Lion King (1994).

Joe Ranft, a Pixar creative cofounder and storyboard artist, is widely celebrated for his imaginative and irreverent contributions to such recent classics as The Brave Little Toaster (1987), Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), The Little Mermaid (1989), Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993), Toy Story (1995), James and the Giant Peach (1996), Toy Story 2 (1999), Monsters, Inc. (2001), and Cars (2006).

Canemaker will sign copies of his book after the lecture on October 1. On October 2, MoMA pays tribute to these master animation storytellers with a selection of wonderful animated features and shorts—including Fun with Mr. Future (1982), which hasn’t been screened in nearly thirty years, and a special screening of Dumbo (1941).

Canemaker will sign copies of his book after the lecture on October 1. On October 2, MoMA pays tribute to these master animation storytellers with a selection of wonderful animated features and shorts—including Fun with Mr. Future (1982), which hasn’t been screened in nearly thirty years, and a special screening of Dumbo (1941).

The MOMA’s programs for Two Guys Named Joe is organized by Joshua Siegel, Associate Curator, Department of Film. Special thanks to Howard Green and Wendy Lefkon.

There will also be screenings attached to the book signing of some Disney and Pixar films:

- Screening Schedule

John Canemaker’s

Two Guys Named Joe: Master Animation Storytellers Joe Grant and Joe Ranft

October 1–2, 2010

Friday, October 1

7:00 John Canemaker’s Two Guys Named Joe. Canemaker discusses the work of Joe Grant and Joe Ranft in a lecture extensively illustrated with film clips and still images. Program 75 min. Introduced by and followed by a book signing with Canemaker.

Saturday, October 2

2:00 Fun with Mr. Future. 1982. USA. Directed by Darrell Van Citters. Joe Ranft contributed gags to this zany short, which was cobbled together from animated bits of a shelved Epcot TV special and is hosted by a talking Animatronics head (with wires exposed) wearing a bowtie. Courtesy The Walt Disney Studios. 8 min.

Luxo Jr. 1986. USA. Written and directed by John Lasseter. The first film to be produced by Pixar Animation Studios after its establishment as an independent studio, and the first CGI film to be nominated for an Academy Award. 2 min.

Tin Toy. 1988. USA. Written and directed by John Lasseter. This Academy Award–winning short anticipates Toy Story in its use of anthropomorphic toys as characters. 5 min.

Toy Story. 1995. USA. Directed by John Lasseter. Story by Lasseter, Pete Docter, Joe Ranft, Andrew Stanton. 80 min. Program 95 min.

5:00 Mickey’s Gala Premier. 1933. USA. Directed by Bert Gillette. Animation character designs by Joe Grant (uncredited). Grant’s first film at Disney, for which he designed all the celebrity caricatures. 7 min.

Who Killed Cock Robin? 1935. USA. Directed by David Hand (uncredited). Story and animation by Joe Grant, William Cottrell (uncredited), and others. Grant and Cottrell devised the satiric story, and Grant designed the characters, including Jenny Wren, a caricature of Mae West. 8 min.

Lorenzo. 2004. USA. Directed by Mike Gabriel. Screenplay by Gabriel, Joe Grant. An Academy Award–nominated short about a blue cat whose tail has a mind of its own. Grant created the concept, story, and character for this, his last film at Disney. Courtesy The Walt Disney Studios. 5 min.

Dumbo. 1941. USA. Directed by Ben Sharpsteen. Screenplay by Joe Grant, Dick Huemer. Courtesy The Walt Disney Studios. 64 min. Program 85 min.

- The school of Visual Arts is having an in-house exhibit of Art called:

- “Ink Plots: The Tradition of the Graphic Novel at SVA. It’s an exhibition of original drawings, books, prints and animation by over 100 artists.

Ink Plots traces the development of sequential art over four decades with selections from SVA faculty members and showcases

the work of SVA alumni who are pushing the boundaries of the graphic novel today.”

Ink Plots: The Tradition of the Graphic Novel at School of Visual Arts

is an exhibition of original drawings, books, prints and animations by over 100 artists. Ink Plots traces the development of sequential art over four decades with selections from SVA faculty members and showcases

the work of SVA alumni who are pushing the boundaries of the graphic novel today.

VISUAL ARTS GALLERY

601 West 26 Street, 15th floor, New York City

Gallery Hours: Monday – Saturday, 10 – 6pm

EXHIBITION:

October 8 – November 6, 2010

RECEPTION:

Thursday, October 14, 5:30 – 7pm

Free and open to the public.

Honoring past and present SVA illustration and cartooning faculty members including:

Sal Amendola_______Sue Coe

Harvey Kurtzman_______David Mazzucchelli

R.O. Blechman_______Will Eisner

Keith Mayerson_______Jerry Moriarty

Tom Gill ____Mark Newgarden

Edward Gorey_______Gary Panter

Burne Hogarth_______Jerry Robinson

Klaus Janson_______David Sandlin

Frances Jetter_______Walter Simonson

Ben Katchor_______Art Spiegelman

Peter Kuper_______

Benefit

Thursday, October 14, 2010, 7 – 10pm

MIDTOWN LOFT AND TERRACE

267 Fifth Avenue, 11th floor, New York City

Shuttle service from the reception to the cocktail party will be provided.

Individual tickets are priced at $250 with $100 tickets available to SVA alumni.

Proceeds from the benefit will be used to establish a scholarship fund for SVA illustration and cartooning students.

Tickets to the cocktail party may be purchased online at alumni.sva.edu/tickets or by calling 212.592.2302 or by

e-mailing serwin@sva.edu.

Other Ink Plots related Events

WILL EISNER,

MASTER TEACHER AT SVA Monday, October 18, 7pm

SVA Theatre, 333 West 23 Street

New York City

Free and open to the public.

INK PLOTS

PANEL DISCUSSION

Wednesday, October 20, 7pm

SVA Theatre, 333 West 23 Street

New York City

Free and open to the public.

DISTINGUISHED ALUMNUS

LECTURE WITH DASH SHAW

Thursday, November 4, 7pm

SVA Theatre, 333 West 23 Street

New York City

Free and open to the public.

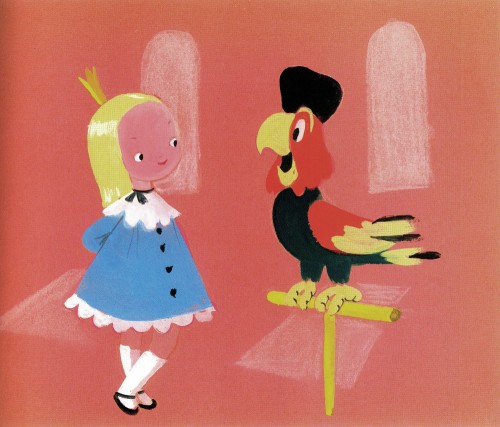

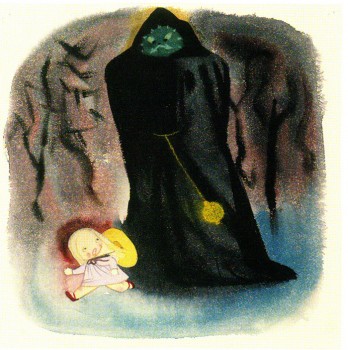

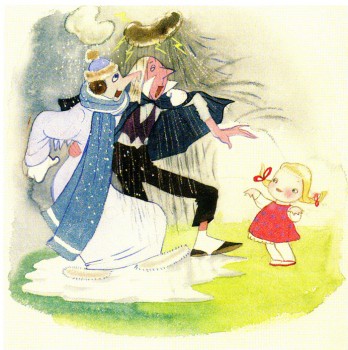

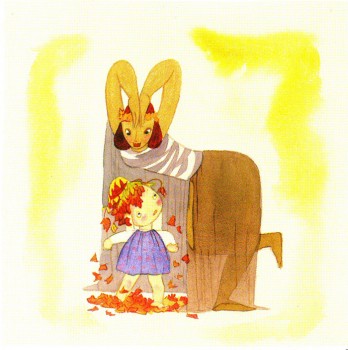

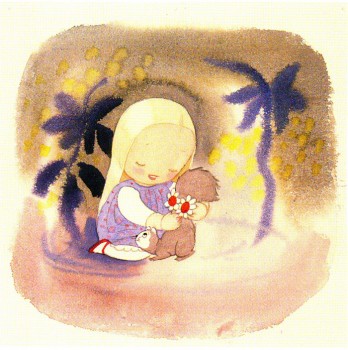

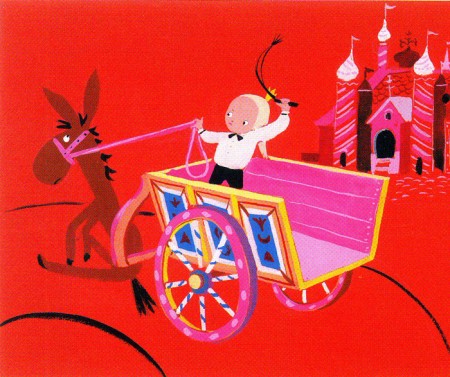

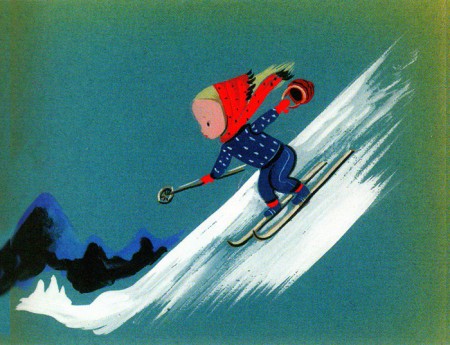

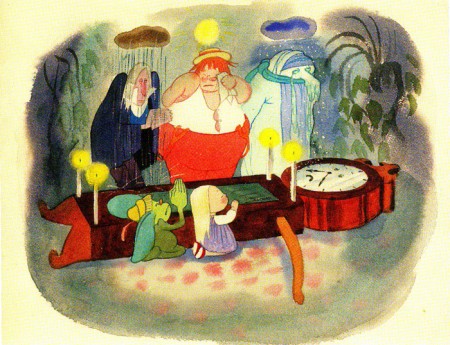

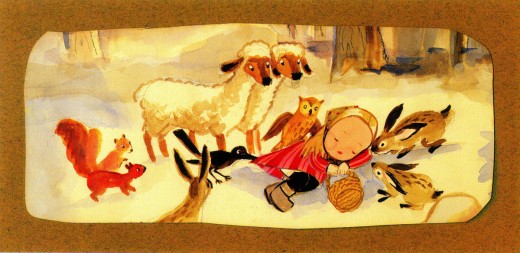

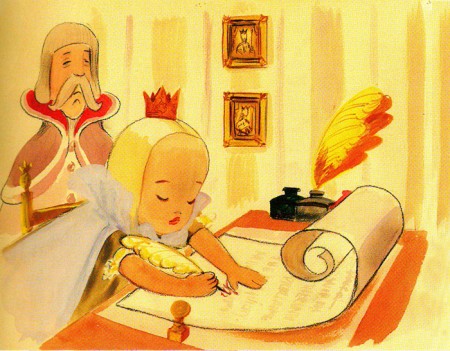

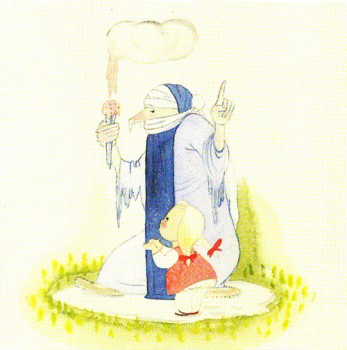

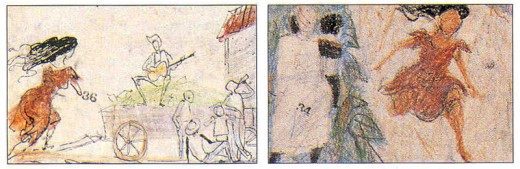

Books &Disney &Illustration &Layout & Design &Mary Blair 19 Jul 2010 07:58 am

Mary Blair – 2

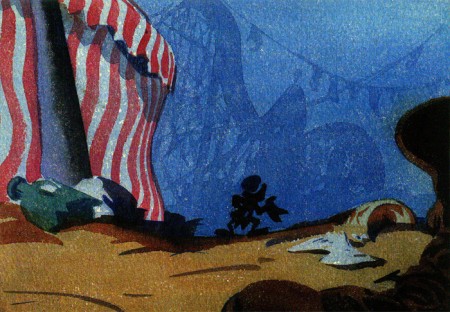

- I’d like to continue showing some of the Mary Blair work pictured in the Japanese book, The Colors of Mary Blair.

The work is sensational, of course, but they aren’t very well identified (in English). Hence I’ve chosen images almost at random without really knowing what projects they’re designed to illustrate. When I do have information, I’m passing it along. I suspect others of you may be able to identify it better that I. (I certainly don’t consider myself an authority on Mary Blair.) If so, please feel free to leave comments.

Mary Blair at Disney.

These first 5 images are from Penelope, a feature about a

time-travelling girl that was never produced.

The following group come from various sources.

Some are from Penelope, although others look like they were

done on the South American trip, with the bold colors.

The following group of six are labelled: “Upsidedownia.”

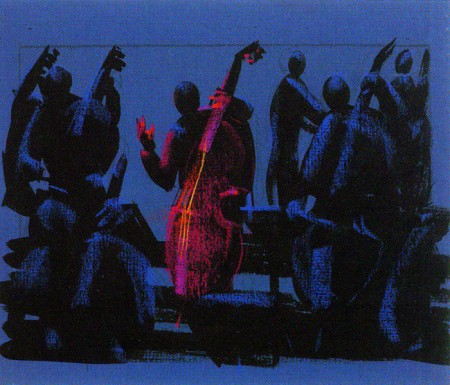

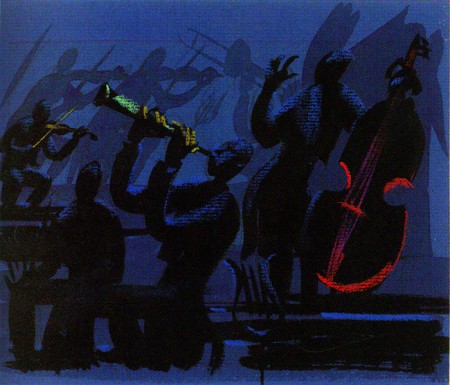

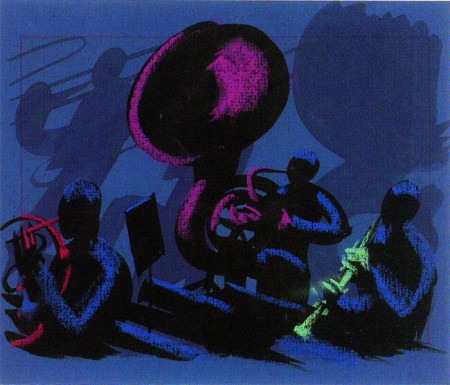

Here are some watercolors Lee Blair did for Fantasia:

And a couple for what looks like Pinocchio.

Articles on Animation 01 Jul 2010 08:02 am

Commercials History

- Earlier this week, I’d posted an excellent piece by Mike Barrier on the work of the Hubleys. This article was taken from a 1977 Millimeter Magazine animation issue. In that same issue, is an article about the history of the TV commercial. There’s a lot of good information in the piece and the shortened history of a lot of important studios that many of you are unfamiliar with. Unfortunately, it also mentions a lot of ads you may not be familiar with. But there’s plenty there in the packed piece. So I thought it a good idea to put this info out there.

Here’s the piece by Arthur Ross.

A Retrospective View

by Arthur Ross

ANIMATE, according to the time-honored Webster’s definition, means “to give natural life to; to give spirit to; to stimulate; to rouse; to prompt; to impart an appearance of life, as to animate a cartoon.”

And that is exactly what animated TV commercials have been doing for the past 30 years. They have given life, spirit, and verve to the selling of thousands of products both in America and abroad.

Psychologically speaking, they work by expanding the fixed limits of reality, by creating new and exciting worlds of fun and fantasy, and by captivating the viewer with fresh perspectives that reinforce our basic drives and motivations for love, success, beauty, comfort, and self-esteem.

During the course of a single 60 second spot, we see 1,440 individual pictures, or frames, come to life! Often with the kind of humor, or whimsy, or charm that speaks to our unguarded and childlike selves, and in some instances, even to the deepest recesses of our unconscious.

That is precisely why they are so potent a sales tool for industry, an educational device for schools, and an entertainment vehicle unto themselves. They work by playfulness, destroying all logical opposition to the messages they may contain.

They dazzle our senses and charm us into belief. Or, at least, they help suspend our disbelief in the ideas they put forth. They are 20th century dreams — dreams that money can buy!

1. Object Animation: Speidel’s “Faces In The Watches”

created by John Gati of Action Pictures.

2. West Coast animation: Bank Americard (FilmFair) 1961-1976

While they operate on our most primative emotional level, animated commercials are highly sophisticated forms of art — employing words, graphics, color, motion, sound, music and symbols to activate the sale of goods and services.

Some of America’s foremost art talent has worked in the field at one time or another, including Saul Steinberg, John Hubley, William Steig, Saul Bass, to name a few.

The earliest animation in the forties was generally quite conventional — literally cartoon commercials of the straight Disney school of animation. It was essentially an extension of theatrical animation such as characterized the products of Warner Brothers, Paramount, MGM, and Disney at the time. Its novelty was successful and proved animated characters could sell products as well as live spokespeople. Everything was executed in glorious black and white, since color on TV was still years away. Commercial studios began to emerge in the late ’40s and early ’50s to supply the demand for animated spots — among them Academy Pictures, Shamus Culhane, Bill Sturm Studios, Film Graphics turning out such early “hall of famers” as the Ajax “Down the Drain” Bubbles and Mott’s “Singing Apples”.

In the early “50s a new trend entered TV commercials when UPA, creators of Gerald McBoing-Boing for theaters, introduced its unique avant-garde style of animation breaking away from the more conventional school of Disney design and execution.

We had the pleasure in the early ’50s of working personally1 with ex-UPA star John Hubley on some of the most successful of these avant-garde spots, including those for Speedway 79 gasoline, Altes Golden Lager Beer and Faygo Beverages (for the W.B. Doner agency in Detroit) as well as Chevrolet (for Campbell-Ewald, again in Detroit.) Other notable avant-garde entries during this period included the famous Saul Steinberg Jello “Busy Day” spot, as well as the classic Bert and Harry Piels spots (for Young and Rubicam).

Continuing through the mid ’50s, two trend-setting studios emerged when John Hubley formed Storyboard Inc. and Abe Liss joined forces with Sam Magdoff to start Elektra Films. Hubley continued his classic style with such winners as Heinz Worcestershire Sauce’s “Tongue-tied Spokesman”, Ford “It’s a Ford” series, and Maypo’s “I Want My Maypo” commercial. Elektra came forth with highly experimental works, creating new breakthroughs in photo-animation, multiple image and optical effects, and totally fresh avenues of design. During this time Elektra spawned such outstanding animation and graphics talents as Jack Goodford, Pable Ferro, Cliff Roberts, the Canattas, Lee Savage, Phil Kimmelman, and Hal Silvermintz, as well as Arnie Levin, Howard Beckerman, and Mordi Gerstein. Among the outstanding Elektra efforts of this era were the NBC Peacock, the legendary “Talking Stomachs” Alka Seltzer spot designed by R.O. Blechman, as well as award-winners for Chevron, Esso, Chevrolet, and Alcoa. One notable achievement, I fondly recall, was a 60-second spot done for the United States Army “Great Moments” series (which I had the pleasure of writing and producing) in which Elektra’s people (including the late Len Appleson) recreated the entire Louis-Schmelling Championship fight with stills quick-cut to the rapid beat of music and crowd cheers. It was a montage breakthrough that Sergei Eisenstein would have been proud of.

Following the success of Storyboard, Inc. and Elektra, more top studies and talent emerged in commercial animation. Pelican films emerged under the able leadership of Jack Zander and did notable work for American Motors, Volvo (designed by Mordi Gerstein) and Alka Seltzer (“The Blahs” designed by cartoonist Willilam Steig.)

Use of famous cartoonists and illustrators in TV Commercials:

Still from a commercial made in the 60s by Elektra Productions,

utilizing cartoonist Bill Steig.

Other fine studios of the fifties were those begun by Lars Calonius, Transfilm, Kim-Gifford, Robert Lawrence and Ernest Pintoff — the latter going on to win an Academy Award for “The Critic” some years later. Arnold Stone was a heavy contributor in those years to the Pintoff output, which included excellent animated spots for Proctor-Silex appliances, Yoo-Hoo Chocolate Drink, and The Bell Telephone Company.

These proved to be the “golden years” for commercial animation with many studios maintaining large staffs to cover the growing need for their excellent product. At one point, there was even a shortage of talent available to handle the work load and one had to “wait on line” for delivery.

In the ’60s, the trend increased towards graphics and we saw a sharp decline in traditional animation. New techniques were perfected — like the super quick cuts of Elektra and Ferro, Mogubgub and Schwartz. The latter also held the industry in marvelous disbelief at its outrageously “insane comic inventions” such as the award-winning “Crazy Hat” commercial for County Fair Bread (which we had the pleasure of producing with them).

Continuing the trend to more limited animation, which UPA orginated as an economical move to cope with the high cost of full animation, studios in the ’60s experimented with photomatics, “squeeze”, semi-abstracts, paper sculpture, and technique of combining live photos with animated bodies (perfected by Paul Kim of Kim-Gifford in a prize winner for the National Safety Council on preventing highway accidents.) Tighter budgets, a declining economy, and a swing away from animation to greater use of realism created massive layoffs in the commercial animation field in the late ’60s and early ’70s — and many good, long-established shops passed from the scene. Smaller one and two-man companies emerged to take their place and this trend continues up to the present day.

It should be pointed out that throughout the ’50s and into the ’60s traditional animation continued as a popular communications tool for many agencies and companies. Outstanding among these was William Tytla Associates. The late Bill Tytla was one of the foremost Disney animators, contributing greatly to the success of such Disney immortals as FANTASIA, PINOCCHIO, SNOW WHITE and DUMBO. In the ’50s, Bill took his talents into the commercial arena and did some outstanding work in the more conventional animation forms. We had the pleasure of working with him in the animation development of the worldwide symbol for Esso, “Happy the Oil Drop,” a fantasy figure that Bill brought to wondrous “life” through his skills as an animation director.

Simplicity of design in 50s & 60s; Still frame from the famous Blechman

“Talking Stomach” Alka Seltzer commercial produced by Elektra in the 60s.

In spite of downtrends in the economy, the late ’60s and early ’70s saw a brilliant new bursting forth of creative energy in animation influenced by Peter Max and the worldwide success of “The Yellow Submarine.”

Among the many fine companies that emerged were Focus Productions, which turned out such award-winners as Vote Toothpaste “Dragon Mouth,” designed by Rowland Wilson; Gillette’s “Moveable Features,” designed by Tomi Ungerer, and the Utica Club Beer series designed by Jack Davis and Mort Drucker. In 1972, Phil Kimmelman left Focus to open his own shop, Phil Kimmelman & Associates. Here, along with Bill Peckman, he has turned out some outstanding efforts including the Cheetos Mouse campaign, the Exxon Tiger, and the delicately sensuous Clairol Herbal Essence commercial.

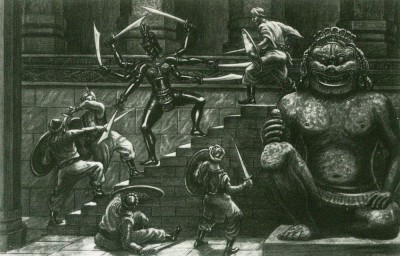

Horror Fantasy in TV commercial animation (1976): Avis Rent-A-Car;

Designer/Director: Mordi Gerstein; Producer Phil Kimmelman & Associates.

Other exciting breakthroughs in the ’70s include the highly graphic look of computer animation, perfected by such companies as Dolphin Productions for use as station and program attractions; rotoscope animation brought to brilliant maturity by Ovation Films in New York and Snazelle Films on the West Coast. The Levi campaign is an outstanding example of rotoscope animation, bringing a fresh new excitement to the field.

On the West Coast, throughout the ’50s and ’60s animation led by UP A, and Storyboard, Inc., continued to expand along with the fine efforts of such companies as TV Spots for Johnson’s Wax, Lucky Lager Beer and L&M Cigarettes; John Sutherland Productions (“A 1580 Atom”); Playhouse Pictures (Ford, Falstaff Beer, H.J. Heinz) Quartet Films (Western Airlines); Animation, Inc. for Oscar Mayer, Soho Boron Gasoline and Pabst Blue Ribbon Beer; and Five Star Productions whose animation department headed by Howard Swift (another ex-Disney man) created some of the earlier TV and cinema commercials for Ford, Pabst, F.T.D., Coca-Cola, as well as bringing Speedy Alka-Seltzer to “life” via the George Pal puppet-type stop motion use of a series of replaceable heads. Interestingly, after a decade of experimenting with other creative directions, Alka Seltzer has just reverted back to using “Speedy” again in its current advertising.

It is an outstanding example of how things come creatively full-circle and how each generation rediscovers the “great ideas” of the past.

Joop Geesink continued to perfect the puppet type animation throughout the fifties, working in Holland for American companies through Transfilm in the United States. His “Brewster, the Goebel Rooster” and Heinz Aristocrat Tomato were two fine creations in this genre.

The use of “stylized” animation-type settings in which live action unfolds was another outgrowth of animation in the late ’50s. S. Rollins Guild whom we had the pleasure of working with at McCann-Erickson in the ’60s contributed greatly to the perfection of this commercial art form for such companies as Nabisco and Coca-Cola. Both series were produced by Bill Sturm Productions in New York.

Black-Lite, while basically a live photographic technique, creates a unique “animation” look to commercials. We had the opportunity of creating and producing the first such black-lite commercial in 1955 for Flagg Brothers Shoes (“Dancing Shoes”) which won numerous Art Director Club Awards for originality and effectiveness. The producing company was Sundial Films, headed by the multi-talented Sam Datlowe. It marked the first commercial assignment for young and talented Jerry Hirshfeld, who later became the ace of the MPO Productions staff, before turning to feature films.

One of the continuing trends in animation today, largely aided by Elektra and Jack Zander in the ’50s, is the use of well-known cartoonists and illustrators from outside the industry. Among the best are Bill Steig, Frank Modell, Charles Saxon, Seymour Chwast, Milton Glaser, and Peter Max, all contributing greatly to the resurgence of animation in the “70s.

Other outstanding work in animated commercials was achieved on the West Coast by Ray Patin, whose chief animator (another Disney graduate) was Gus Jekel, now the head of Film Fair, Inc. They accomplished some fine efforts for Y&R on Jello in the early ’50s through Jack Sidebotham, one of the really great art directors in the advertising field. These include such classics as “Banana-ana,” and “Chinese Baby.” Ray Patin also turned out the NY AD gold medal Bardahl series, aping Dragnet, as well as noteworthy campaigns for National Bohemian Beer and Jax Beer.

In passing, one must not forget to include in the pantheon of animation producers such fine organizations as Cascade Productions, Playhouse Pictures, Quartet, Imagination, Inc. all of whom executed award-winning series in the ’50s and ’60s.

In the ’60s, Gus Jekel’s Film Fair did noteworthy series for BankAmericard and Bardahl which won the Cannes and Venice Awards. Today, Film Fair does exceptional work with continuing characters, such as Peter Pan (Peanut Butter). Charlie Tuna, Tony Tiger, and the Snap, Crackle and Pop trio for Kellogg’s Like Elektra in the East, Film Fair nurtured a great deal of the best West Coast talent including Art Babbitt, Bob Cannon, Dick Van Benthem, Ken Walker, Fred Wolf, Norm Gottfredson, Ken Champin, and Corny Cole. It is one of the reasons the West Coast continues to do such exciting creative work in the field along with its East Coast counterparts.

One of the long-standing successful animation partnerships in the East has been Paul Kim and Lew Gifford, doing fine work in the field since 1958. Among their top creative efforts are award-winners for Piels Brothers, and the Emily Tipp series. Their Modess a delicate subject with taste, simplicity, and artistry. And their famous Winston “Montage” introduced a 14 way split screen in constant movement to the Winston jingle — breaking exciting new ground in the use of matte work and animation design.

Another top West Coaster is veteran animator Herbert Klynn, President of Format Productions. Herb served 16 years as designer and then Executive Production Manager for UPA, before organizing his own animation company. His Format Productions is active in entertainment series such as the Alvin Shows, the Lone Ranger and Popeye programs, as well as creating titles for such TV shows as I Spy, Smothers Brothers, and The Mothers-In-Law. Among his fine animated TV commercials are those for Max Factor, Post Cereals, Wells Fargo Bank, and Dreyfus Investments. During his tenure with UPA, Herb worked on such classic film cartoon short subjects as “Madeline,” “Mister Magoo,” and “Gerald McBoing-Boing.” Our own particular favorite is his treatment of Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart” for UPA.

1. Graphic animation of a “strobe” like image of a golfer, made with 90 kodalith negatives

in registration. (World Series of Golf” Show opening by Goldsholl Associates.

2. The Unspoken Spoken Message: Modess “Because” (1962) Kim & Gifford Productions

Some fine animation has come out of the Midwest, too, in recent years. A key contributer from that area is Goldsholl Associates, an Illinois-based house that has brought fresh innovative graphics and experimental style to animated TV spots. In such commercials as 7-UP’s Sugar-Free “Carton Graphics” they infuse “life” into abstract dots to create a rich new imagery on screen. Colors, shapes, and textures all impart a “meaning” experi-entally to the message.

One of the more prolific of New York’s animators is Jack Zander. He began his career in 1946 at Willard Pictures doing an animated Chiclets commercial in which he animated Chiclets’ boxes like a choo-choo train to a music track taken off a 78 rpm radio transcription. In 1948, he started up the animation department at Transfilm, where he created the first animated Camel Cigarette commercials and helped develop the paper “cut-out” technique. In 1954 he and Joe Dunford opened Pelican Films and did successful commercials for over 16 years, along with Mordi Gerstein, Lars Colonius, Paul Harvey, Wayne Becher and Dino Kata-polis. During this period, Jack utilized the service of several wellknown cartoonists, including Charles Saxon for American Airlines, and later Bill Steig and George Price of “New Yorker” fame. It was also during this period that Jack did the famous Nichols and May “Jax Beer” animated series, as well as some of the early Bert and Harry Piels spots.

In 1970, Jack moved across the street and launched Zander’s Animation Parlor with his son Mark. He has created his share of “hits” in recent years, too, including the exceptionally fine Freakies campaign, beautifully animated by Preston Blair.

Another fine New York animation talent is Art Petricone who today heads up Ovation Films. In addition to his fine work for Eastern Airlines, his brilliant use of rotoscope can be seen in his work for Levi Strauss and Clairol Herbalessence.

In the area of object and figure animation and stop motion, John Gati, the Director of Special Effects, for Action Pictures in New York is unsurpassed. John has been working at his craft for 26 years and has won many awards for technique and innovation.

The art of Object and Figure Animation requires enormous craftsmanship. Basically, it resembles conventional (drawn) animation in that it follows the rule of “creating the movement” by the process of frame by frame photography. But as opposed to eel animation, which occurs on a two dimensional (acetate) surface, Object Animation is similar to live action photography taking place in a three-dimensional area.

John Gati’s creations succeed in making the product itself (the object) become the hero of the commercial, which is one of the basic tenets of good “sell” advertising. Complicated rigs and special dimensional lighting are required to make this form of animation truly work. It requires enormous intricacy to sustain the fantasy of “life” for these objects. John works with such materials as foams, wires, rubbers, vinyls, plastics, silks, clays and waxes to create the illusion of “reality.” Working in the tradition of the great artists and artisans of the past, John — like McLaren and Trnka and Geesink — has created a wondrous world of living and moving objects that reflect a “life all their own. Among his most recent successes are Fleischman’s “Egg Beaters” and Speidel’s “Faces In the Watch-bands. ”