Monthly ArchiveOctober 2012

Articles on Animation &Richard Williams &Tissa David 01 Oct 2012 06:37 am

Raggedy Ann and Andy

- On Tuesday, October 23rd a memorial service for Tissa David will be held at the Lighthouse Academy Theater at 111 East 59th Street. It will begin punctually at 7pm. Seats will be available on a first-come first-served basis. To continue celebration of Tissa’s work, here’s an article that appeared in Cartoonist Profiles Magazine, No.33, March 1977. No writer’s name is credited.

We thank Mike Hutner. of Twentieth Century-Fox, for the production notes about this new full-length animated film, RAGGEDY ANN & ANDY, which is having its world-premiere in New York on March 20th.

Raggedy Ann is a caricature of a rag doll, with stringy red hair, button eyes and a painted triangular nose.

Raggedy Ann is a caricature of a rag doll, with stringy red hair, button eyes and a painted triangular nose.

Harold Geneen is the Chairman of the Board of the ITT Corporation, an industrial empire which includes hotel chains, construction companies, the Bobbs-Mcrrill book publishing house and a car rental lirm which tries harder.

It was hardly destined that they would be linked in one of the year’s most ambitious entertainment ventures. But the proof is on 35mm Panavision film, in the form of “Raggedy Ann and Andy,” the feature-length animated musical from 20th Century Fox.

The genesis of the full-length am mated musical—one of the few such projects attempted during the past few decades without the Disney insignia—is a story which has its own touches of fantasy. In addition to ITT’s Board Chairman, the principals include:

• A team of Broadway theatre-owners and producers, who never before made a movie, lei alone an animated feature.

• An Emmy-winning composer, one of whose songs was a hit for both “Kermit the Frog” and Frank Sinatra.

• An Academy Award winning director who thought he was out of the picture until he look part in an all-night jam session at his Soho studio.

• Several legendary cartoonists, including the originator of “Betty Boop” and the man who gave Disney—and the rest of America—the beloved “Goofy.”

How they came to join forces really begins in Silvermine, Conn, in the early 1900′s. when newspaper cartoonist John Gruelle took a few minutes away from his drawing board to help his daughter fix a discarded rag doll. The toy was named “Raggedy Ann” by combining characters from two poems by James Whitcomb Riley — The Rag Man and Orphan Annie.

When Marcella Gruelle became desperately ill, her father sat by her bedside, making up stories about the doll’s adventures after everyone in the house was asleep. Marcella died on March 21st, 1916. after which her father determined to share with the world the stories he had not had time to tell her.

By the early 1970′s. Raggedy Ann was part of American folklore, a character whose exploits had sold some 80 million books and hundreds of millions of toys and games. That was when Lester Osterman. a former stockbroker who brought Sammy Davis Jr. to Broadway in “Mr. Wonderful.” and Richard Horner an ex-actor who had appeared in the Oberammergau “Passion Play” became involved. The producers of such Broadway successes as “Butley” and “Hadrian the Seventh,” they had just completed a live-action television special for the Hallmark Hall of Fame, based on the children’s classic. “The Littlest Angel.” Now they were searching for a similar property . . . for the same showcase.

A casual lunch with a merchandiser of children’s toys proved crucial. “Would you believe that after all these years. ‘Raggedy Ann’ is -.till one of the biggest sellers?” inquired the friend rhetorically. Within a few days. Osterman and Horner were on the doorstep of the Bobbs-Merrill Company, which publishes the “Raggedy Ann” stories, requesting development rights to the character.

An equally informal meeting with Joe Raposo. Emmy-winning composer-conductor of “Sesame Street,” brought music to the project. Horner and Osterman found themselves seated with Raposo at a Friars’ Roast for Johnny Carson. Somewhere between the broiled chicken and dessert, Raposo agreed lo score the “Raggedy Ann” tales.

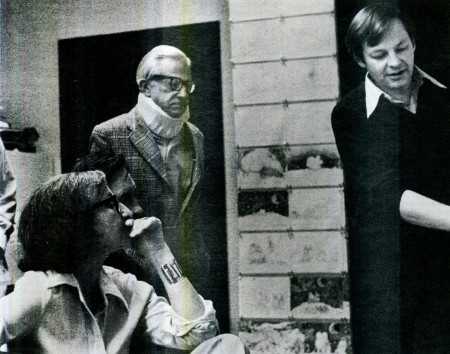

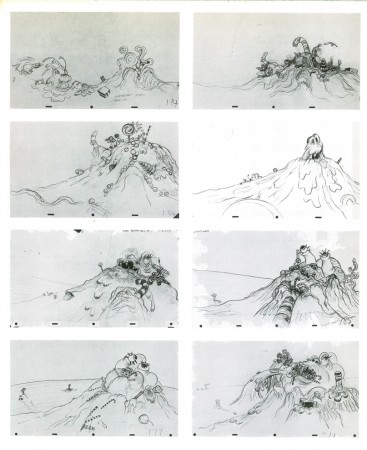

Animators Tissa David and Art Babbitt with director Dick Williams.

Next to join the troupe were writers Max Wilk and Pat Thackeray. True to Gruelle’s imagination, they created a fantasy world in which toys spring joyously to life. When Raggedy Ann discovers that the pixieish French doll, Babette, has been kidnapped by a pirate known as Captain Contagious, they set out to free her. That takes them into the “deep dark woods”, inhabited by such personalities as the “Looney King,” “the camel with the wrinkled knees” (one of Gruelle’s personal favorites) and the “Greedy,” a kind of confectionery version of the La Brea Tarpits. “We thought we were writing a live television special,” recalls Ms. Thackeray. “So much so that we began casting Raggedy Ann in our minds, alternating between personalities like Liza Minnelli and Goldie Hawn.”

But Raposo was having second thoughts. “It won’t work,” he finally admiitted. “Put a red fright wig and a painted mouth on an actress— any actress—and do you know what you’ll have? A circus clown.”

The obvious alternative was a full-length animated musical cartoon. Which is like saying the obvious alternative to your reliable family car is to go out and buy a Rolls Royce. There is a reason, as director Richard Williams would later point out, why animated features are almost exclusively the province of the Disney organization. “And even Disney turns out several live comedies and nature films for every animated movie.” Williams notes.

To create 90 minutes or more of full animation (as opposed to the jittery short-cuts of television cartooning) requires more than one million preliminary and final drawings. From inception to “answer print” lakes three years or more. “And the cost,” adds Williams, “is tremendous.”

“Since the Hallmark people had discussed a live musical, they were perfectly justified in walking away from a more costly animated feature,” says Horner. The producers now had a cartoon without a cartoonist, a television special without a sponsor, and a project without investors. But it was no time to think small. Why settle for a television special? Why not make “Raggedy Ann and Andy” as a movie?

It was back to Bobbs-Merrill with the suggestion that Osierman-Horner and the publishing house become partners in the proposed film. That, the publishing executives said, was up to their parent company, ITT. A meeting was arranged with Board Chairman Geneen. which developed into a corporate backers audition.

Pat Thackeray later described the “incredible afternoon” to author and critic John Canemaker, whose book, “The Animated ‘Raggedy Ann and Andy’-The Story Behind Ihe Movie,” will be published at the same time as the 20th Century Fox release.

“Geneen came into the room, asking questions, his mind like a laser,” she said. “He remembered a stage version of ‘Raggedy Ann’ he’d enjoyed as a youngster, in the I920′s. We made our presentation. Then, as we were going down in the elevator, a guard told me, ‘I don’t know who you are but you’ve got it made.’

“I asked why.

“The guard said, ‘Because the old man stuck his head out of the door and asked what I thought of the music coming from his office. I said it sounded pretty good to me. That wasn’t just good, Harry,’ he said, ‘that was terrific.’”

With financial backing assured, the next problem was simple. Who would draw the million-plus pictures which would make up the finished movie? And who would piece them all together with wit and style?

Firsl choice was Richard Williams, the Canadian-born, London based head of his own animation studio who had won an Academy Award for “A Christmas Carol” and a host of admirers for the “Return of the Pink Panther.” Despite a commitment to his own project, “The Thief and the Cobbler” Williams listened to Raposo’s score, and said yes.

“But my business manager said ‘no,’” Williams recalled. “Or to put it more accurately. he priced my services so high, there was no way the picture could have come in on budget.” What happened to the business manager? “He’s not with me anymore,” Williams replied with British sang-froid.

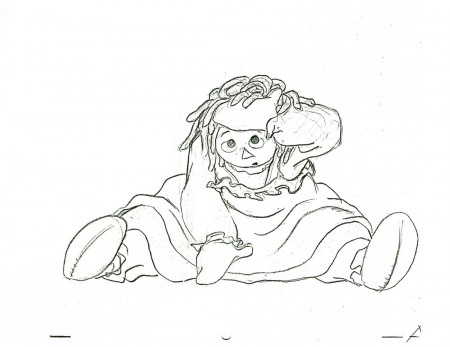

Tissa David’s rag doll

Osterman and Horner began negotiations with a New York cartoon “factory” which specialized in limited animation for television. Within a short period (according to Canemaker), the newcomers had virtually thrown away the Wilk-Thackeray script, replacing Gruelle’s characters with a “Love Fairy” and a “Cookie Giant.” Outraged. Raposo walked out of a story conference (“before 1 threw up from all that treacle,” he recalls) and caught a plane to London to make a last-ditch attempt at hiring Williams.

Discovering a shared taste in jazz, the two men opened a bottle of Scotch and during an impromptu jam session, past misunderstandings vanished in a vapor of 12-year-old malt and good will. The animated movie finally had an animator.

It was Williams who formulated the approach to the picture. “Disney’s contribution to animation is colossal,” he said. “The technique of bringing a cartoon character to life would slill be in the dark ages without Disnev. But to copy the ‘look’ of his films would have been disastrous.

“Instead, 1 said, ‘let’s be as rich and lush as Disney in a totally different style … in the style of Johnny Gruelle.’”

A remarkable team of animators was assembled in New York and Hollywood lo carry out that mission. Included were several men and women who can legitimately be termed ‘living legends’ in the field of motion picture cartooning.

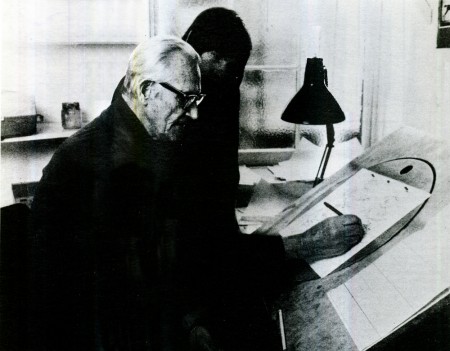

There was Grim Natwick, a spry octogenarian, who had designed the first of the “Betty Boop” pictures for producer Max Fleischer in the thirties and animated the majority of Snow White’s scenes for Disney. Another Disney veteran was Art Babbitt, the co-creator of “Goofy” and the dancing mushrooms in “Fantasia,” whose verbal donnybrooks with Disney during the I940′s had been peppery Hollywood gossip.

85 year old animator Grim Natwick

with young animator Crystal Russell

To draw the “Greedy,” a ‘monster’ made of whipped cream, cherry banana taffy, chocolate fudge and other sugary delights. Emory Hawkins—a veteran of Disney as well as the MOM and Warner Brothers cartoon studios -was summoned from his New Mexico ranch. “Raggedy Ann” herself was drawn by Tissa David, a Transylvanian-born artist who had worked with Natwick at UPA Productions during the heyday of “Mr. Magoo” and “Gerald McBoing Boing.”

From Canada came Gerald Potterton, head of his own animation studio. whose credits include the Peabody Award winning “Pinter People” and key sequences in the Beatles’ “Yellow Submarine.” The design of the vital storyboards and layouts which gave the picture its graphics stamp was up to Cornelius “Corny” Cole, both an animator and a renowned painter.

The musical routines for the “Twin Penny Dolls,” whose movements are perfectly synchronized with each other, were drawn by Gerry Chiniquy. who looks like Gene Kelly and specializes in “dance animation.” During a ten year period at the Warner Brothers Studios, whenever Bugs Bunny or Daffy Duck were called on to trip the light fantastic, Chiniquy got the nod.

Soon, the sketches began mounting—at the unit’s bustling New York headquarters (which are wag dubbed “Raggedy Ann East”), a California studio and director Williams’ home base in London. Williams’ job was clearly defined.

“I was in charge of catching airplanes,” he laughed. Spending ten days to two weeks in each city, Williams would check the work of dozens of illustrators, pencil in his own suggestions, hold story conferences, review preliminary sound-track recordings, analyze the “Leica Reel” (a rough compilation of the motion picture in progress, pieced together as new drawings and backgrounds were added “like a jigsaw puzzle”), then rush to the airport.

“I became one of the world’s great authorities on jet lag,” he added.

Choosing the voices of Captain Contagious, Suzy Pincushion, the zany “Gazooks” and other denizens of Raggedy Ann’s fantasy world became a crucial problem. Tradition says the voices for a feature-length cartoon should be box-office names whose unseen presence will enhance the picture’s publicity and promotion. Raposo and Williams chose to defy tradition, backed by co-producer Horner. “We were treating the picture as a big, lavish Broadway musical—in the form of an animated cartoon—so we looked to Broadwav for vocally gifted actors,” said Raposo. Casting sessions were held in a New York studio, where hundreds of performers went through their paces.

“I knew the long hours were getting to me when 1 walked through the hall, outside the studio, and saw a man reading our script, who really looked like a camel,” said Williams. Ironically, the actor was dour-faced Fred Stuthman, who eventually did provide the voice for the “Camel With the Wrinkled Knees.”

Another actor’s reaction set the whimsical tone of the casting sessions.

“You want me to play what?” said Joe Silver, veteran of such movies as “The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz”, in utter disbelief.

“An enormous pit of taffy, filled with gum-drops and maraschino cherries and covered with chocolate sauce,” answered casting director Howard Feuer.

“Is this a gag?” asked Silver. He was quickly persuaded it was not and even more quicklv rose to the chocolate covered challenge.

Emory Hawkins Taffy Pit

Virtually all of the “Raggedy Ann and Andy” voices are better known to their peers than to the general public. Included are Didi Conn of the television series, “The Practice.” whose voice has been likened to that of a “sexy frog” as Raggedy Ann: Mark Baker, co-star of Leonard Bernstein’s “Candide” as Andy: Allan Sues from “Laugh-In.” Arnold Stang, Mason Adams and George S. Irving. The “sockworm” is vocally portrayed by a man with more impressive credentials in another phase of show business—Sheldon Harnick, lyricist of “Fiddler on the Roof.”

Only one performer is seen on film, during an introductory sequence about Marcella Gruelle. Casting the role, director Williams, recalls, was a thorny problem. “I needed a little girl on whom 1 could impose a 12 hour work day, to stay within schedule.” Rather than face some other lot’s outraged parents, he elected his own six-year-old daughter, Claire. “My presence made it a kind of game for her.” he adds.

Meanwhile, the pressure at Raggedy Ann East. Raggedy Ann West and the London base was mounting. Williams and his associates had promised a finished movie to Bobbs-Merrill in time for the film to be launched nationally by Easter, 1977. The million-plus drawings had been completed, and now the inkers, opaquers, “in betweeners,” and other technical craftsmen, vital to an animated movie, were working double and triple shifts, to meet the deadline.

The only rule, Williams paradoxically demanded as he fired memos to the tripartite staff (“usually dictated somewhere over Kansas,”) was that there must be no compromise in quality. Typical of the fine detail necessary to achieve “full animation” was an incident which occurred in the office of veteran supervisor Marlene Robinson. An “inbetweener”-responsible for linking the animators’ drawings, frame by frame—was frustrated. Several strands of Raggedy Ann’s hair refused to move in rhythm with the rest of the character.

The next hour was devoted to re-drawing the wisps of hair, over and over, until there was perfect synchronization.

“It seems like such a little thing,” Ms. Robinson said afterward. “But blown up to Panavision size, anything which distracts the eye of the moviegoer—shapes that vary, colors that fade, even a recalcitrant strand of hair, is enough to destroy the ‘illusion.’”

Babbitt’s “Camel with the wrinkled knees”

In another room, Cosmo Pepe, working with complex equipment designed by cameraman Al Rezek, was transferring the drawings onto sheets of transparent celluloid—by shooting 13.000 volts of electricity through them-prior to putting them through a Xerox enlarger. “We developed a special toner, for the enlargements, to Dick Williams’ specifications,” Pepe revealed. “The toning is vitally important: it affects the way the characters stand out on the big screen. The formula for this toner is as closely guarded as a three star chefs award winning recipe.”

By the lime “Raggedy Ann and Andy” was completed, and ready for release by 20lh Century Fox more than five years had passed from the date on which Osterman and Horner first solicited the rights from Bobbs-Merrill. More than two years had been spent in production.

Richard Williams summed up the feelings of everyone involved by quoting Johnny Gruelle. “It does pay to do more work than you are paid for, after all,” Gruelle once told an interviewer. “Someone, somewhere, sometime will see it and appreciate it.”