Category ArchiveRichard Williams

Articles on Animation &Commentary &Richard Williams 01 Oct 2013 08:00 am

And do you believe it! They closed the government. Only Chris Matthews can handle it from here upon out!

Tweedledee and Tweedledum

Tweedlededum, can you please introduce yourselves to the court?

Tweedledee

That’s just the problem.

Court

Gasp!

Tweedledum

That’s just the problem; we can’t.

We don’t know who we are anymore!

Believe it or not. They shut down the government.

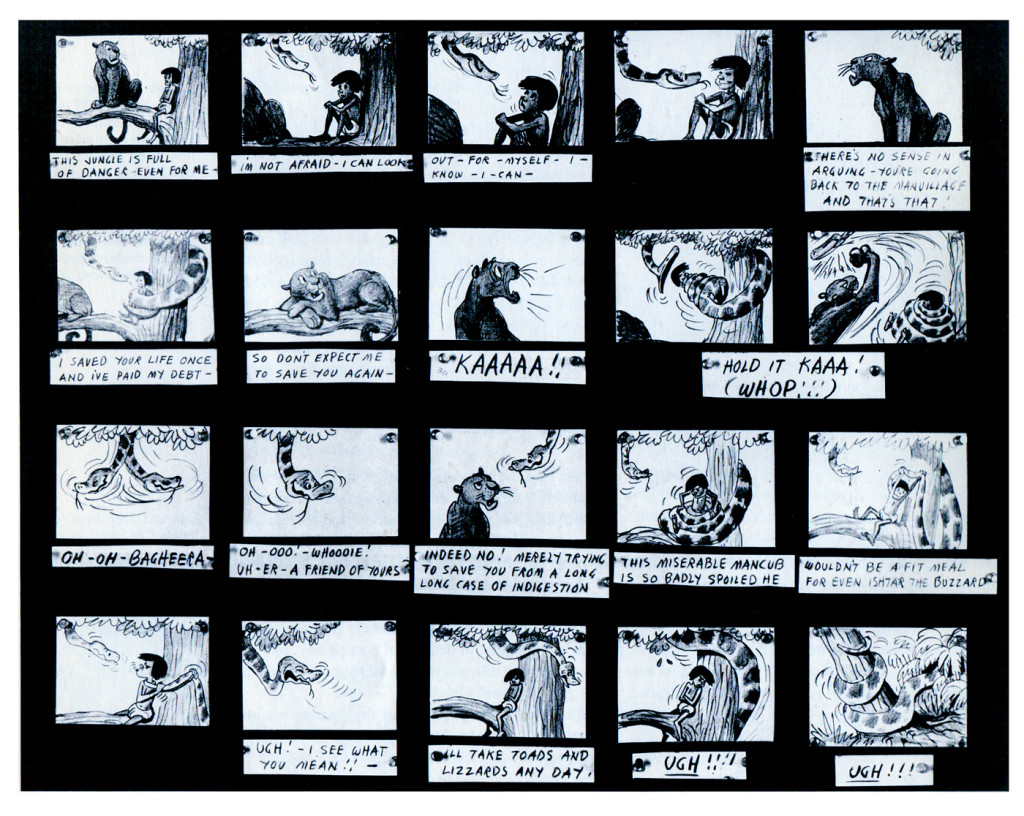

This coming Friday, Oct. 4th, the MP Academy will hold a special screening featuring Richard Williams. Williams will discuss the work that has inspired him and the people who have influenced him. Some of his favorite clips will be shown to illustrate the artistic and emotional range of the medium. From the charm of Snow White and the imagination of Fantasia to the stylization of Rooty Toot Toot and the “subtlety of expression of Toy Story W illiams will also enlighten audiences about his own work through clips from The Little Island, The Charge of the Light Brigade a Christmas Carol and The Thief and the Cobbler (inlcuding its first theatrical trailer, as well as a preview of his work-in-progress, Circus Drawings.

This coming Friday, Oct. 4th, the MP Academy will hold a special screening featuring Richard Williams. Williams will discuss the work that has inspired him and the people who have influenced him. Some of his favorite clips will be shown to illustrate the artistic and emotional range of the medium. From the charm of Snow White and the imagination of Fantasia to the stylization of Rooty Toot Toot and the “subtlety of expression of Toy Story W illiams will also enlighten audiences about his own work through clips from The Little Island, The Charge of the Light Brigade a Christmas Carol and The Thief and the Cobbler (inlcuding its first theatrical trailer, as well as a preview of his work-in-progress, Circus Drawings.

Tickets are $5 for Gen’l Admission and $3 for Academy members. (I’ve just learned that the event is, of course, sold out.

From Oct 4th thru Dec 22nd there will be a gallery showing at the Academy theater, and that can be seen when your schedule permits.

Go here to see three of these vids. Very entertaining.

Action Analysis &Animation &Articles on Animation &Books &Commentary &Disney &Illustration &Richard Williams &Rowland B. Wilson &SpornFilms &Story & Storyboards &Tissa David 10 Jun 2013 03:31 am

Illusions – 3

I’ve written two posts about Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston‘s book, The Illusion of Life the last couple of weeks. I came to the book only recently and realizing that I’d never really read the book, I thought it was time. So in doing so, I’ve found that I have a lot to write about. The book has come to be accepted almost as gospel, and I decided to give my thoughts.

There were two major complaints I’ve had with what I’ve read in their book so far, and I spent quite a bit of time reviewing those.

- First out of the box, I was stunned to read that these two of Disney’s “nine old men” said that they’d originally believed that each prime animator should control one, maybe two characters in the film. Then, later in life they decided that an animator should do an entire scene with all of the characters within it. This is not what I’d seen the two (or the nine) do in actual practice. post 1

Secondly, they argue for animating in a rough format, and they give solid reasons for this. As a matter of fact, it was Disney, himself, in the Thirties who demanded the animators work rough and solid assistants who could draw well back them up. Then much later in the book the two author/animators suggest that it’s better for an animator to work as clean as possible with assistants just doing touch-up. This helped out the Xerox process, but didn’t necessarily help for good animation. post 2

The book starts out sounding like it’s going to be a history of Disney animation, but then starts getting into the rules of animation (squash and stretch, overlapping action and anticipation and all those other goodies) exploiting Disney animation art in demonstration. Soon the book moved into storytelling and how to try to keep the material fresh and interesting. It all becomes a bit obvious, but you keep hoping that some great secret will be revealed by the two masterful oldsters.

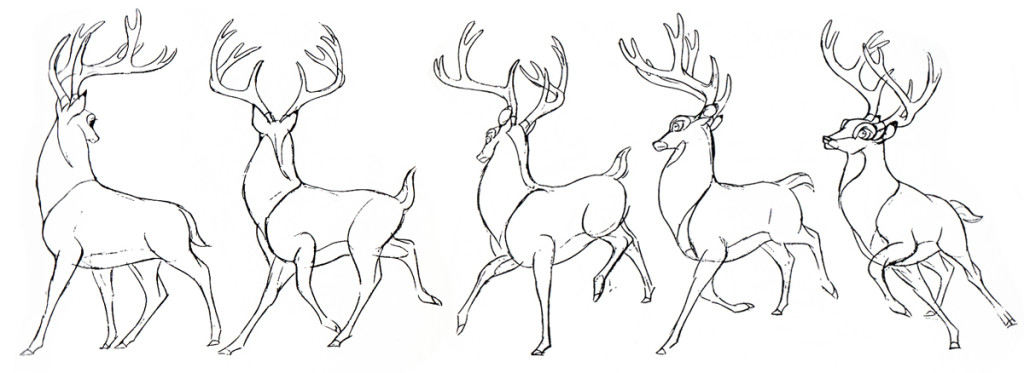

They do go into depth about how to develop characters when making animated films. They offer lots of examples from Orville, the albatross in The Rescuers to the three fairies in Sleeping Beauty, but their greatest attention goes to Baloo the Bear in The Jungle Book. They were having a hard time with this guy; they had been trying to do an Ed Wynn type character, until Walt Disney, himself, suggested Phil Harris. Once they auditioned Harris, they knew they were on the right track, and the character kept grabbing more screen time and grew ever larger. In the end, audiences just loved him.

They do go into depth about how to develop characters when making animated films. They offer lots of examples from Orville, the albatross in The Rescuers to the three fairies in Sleeping Beauty, but their greatest attention goes to Baloo the Bear in The Jungle Book. They were having a hard time with this guy; they had been trying to do an Ed Wynn type character, until Walt Disney, himself, suggested Phil Harris. Once they auditioned Harris, they knew they were on the right track, and the character kept grabbing more screen time and grew ever larger. In the end, audiences just loved him.

Personally, I’ve always hated Phil Harris’ performance in this film. What was it doing in Rudyard Kipling’s book? When I was a kid, Harris and Louis Prima were the perfect examples of my father’s entertainers. He loved these guys and spent a lot of time in front of the family TV watching the Dinah Shore Show______Tom Oreb designs for Sleeping Beauty.

and other such entertaining Variety Shows with

lots of little 50′s big-band jazz-type acts. I hated it; this was my parent’s kind of music and humor and had nothing to do with me. I was the kid who paid his quarter to see the Walt Disney movies (that was the children’s price of admission in 1959.)

In their book they say they knew he was perfect because generations of kids later (who have no idea who Phil Harris was) still take joy from Baloo. What they forgot is what I knew all along. This was The Jungle Book. If they had been truly creative, they would have developed a character in line with Kipling’s material that would have been an original, not an impersonation of Doobey Doobey Doo, Phil Harris. The same is true of Louis Prima as a monkey. (There was a time when Disney said that they should never animate monkeys because monkeys are funny on their own, in real life. Animation wouldn’t make them funnier.) Sebastian Cabot, as Bagheera, works as does George Sanders as Shere Khan.

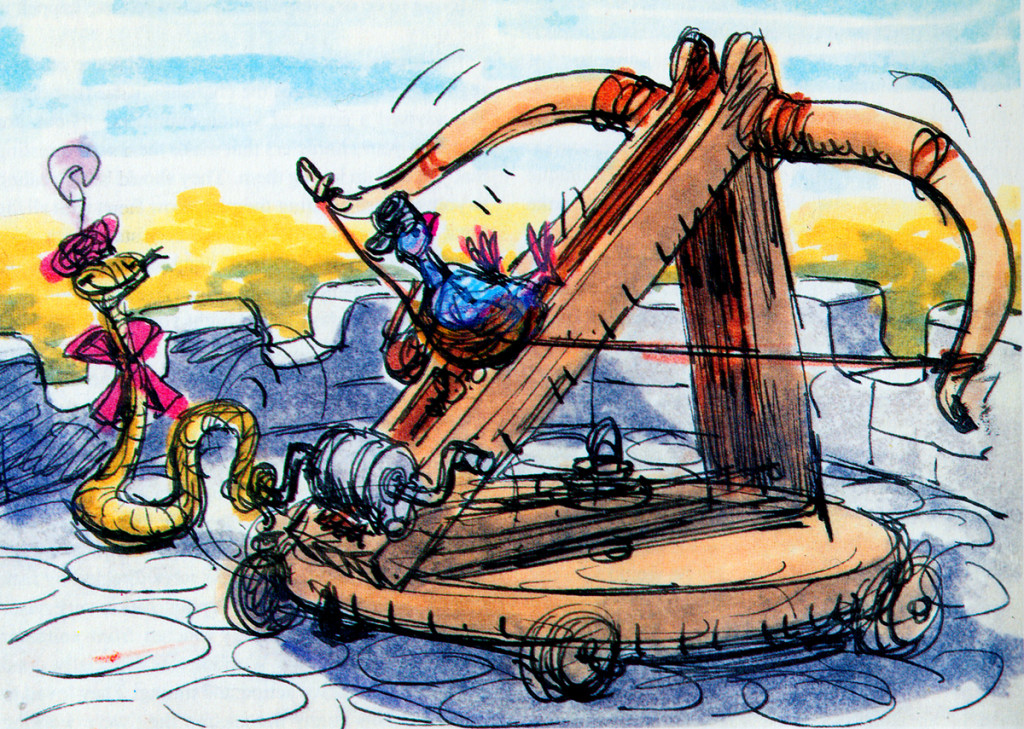

- Right: A discarded sequence from Robin Hood showed a messenger pigeon so fat and heavy he had to be shot into the air. This gave the animators the beginnings of The Albatross Air Lines in The Rescuers.

Phil Harris was so successful, they dragged him into Robin Hood as well. Robin Hood. The very same character from The Jungle Book is now Little John! All those cowboy voices in Robin Hood don’t work either, especially when you mix them up with Brits like Peter Ustinov and Brian Bedford. When these two thespians work against Pat Buttram, Andy Devine and George Lindsey, it’s one thing. Throw in a Phil Harris, and you have something else again. Where are we, the audience, supposed to be? Is it “Merry Ol’ England”? Or is it the lazy take on character development by a few senior animators who have taken license to jump away from the story writers for the sake of easy characters of the generation they’re familiar with. Robin Hood is a mess of a story – even though it’s a solid original they’re working from, and I find it hard to take written advice from these fine old animation pros who take an easy way out for the sake of their animation; shape shifting classic tales to fit their wrinkles.

At least, that’s how I see it – saw it. And perhaps that’s why it’s taken me so long to read this book. I felt (at the age of 14 when these films came out) that the Disney factory had turned into something other than the people who’d made Snow White and Bambi and Lady and the Tramp.

They had, in fact, become the nine old men.

The Jungle Book was the last film Bill Peet worked on. He left

before the film was done. He’d had a long, contentious relationship

with Disney. He never felt he’d gotten the respect he deserved.

They were incredibly talented animators, and they certainly knew how to do their jobs. The animation, itself, was first rate (sometimes even brilliant as Shere Khan demonstrates), but try comparing the stories to earlier features. Even Peter Pan and Cinderella are marvelously developed. Artists like Bill Peet and Vance Gerry knew how to do their jobs, and they did them well. When Peet quit the studio, because he felt disrespected, Disney’s solid story development walked out the door.

The animators were taking the easy route rather than properly developing their stories. The stories had lost all dynamic tension and had become back-room yarns. Good enough, but not good.

Today was Nik Ranieri‘s last day at Disney’s studio. He’s definitive proof, in the eyes of Disney, that 2D animation is dead as an art form. This is the end result of some of the changes Thomas and Johnston suggest in their book. The medium took a hit back then; it just took this long for the suits to catch up. Good luck to Nik and the other Disney artists who no longer work steadily in what is still a vitally strong medium.

commercial animation &Errol Le Cain &Illustration &Independent Animation &repeated posts &Richard Williams &Rowland B. Wilson &Tissa David 10 Apr 2013 05:55 am

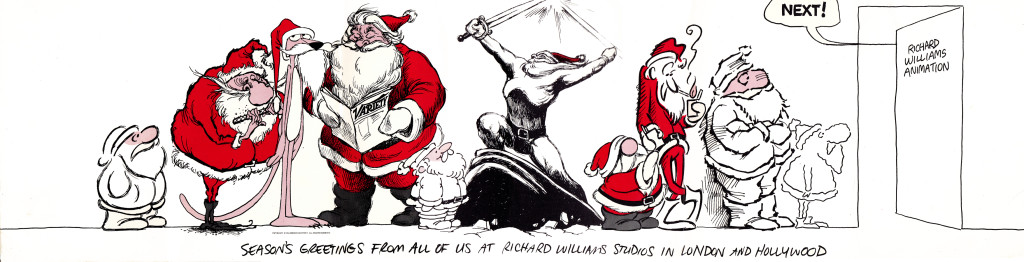

Dick’s Christmas

Richard Williams, when he had his own studio, was known for doing everything in a LARGE way. All of the commercials, title sequences, shorts were all done with a large, elaborate vision.

The Charge of the Light Brigade was a collection of 19th century graphics that are completely wrong, stylistically, for animating. All those cross-hatched lines. God bless the artists that pulled that off. The same was true for The Christmas Carol.

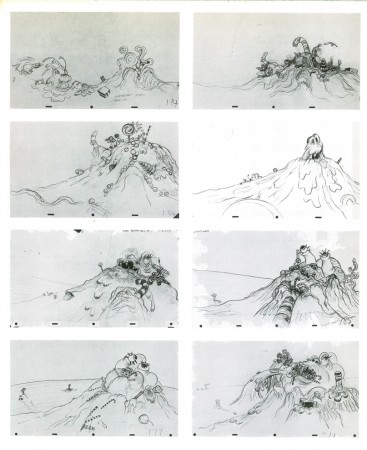

If the rendering style wasn’t impossibly difficult, then the animation was complex. Think of any of the scenes from Dick’s dream-feature, The Thief and the Cobbler. The many scenes where backgrounds were animated, with those backgrounds complete with complicated floor patterns or an entire city to be animated. Raggedy Ann was covered in polka dots and Andy was clothed in plaids. Both of the characters had twine for hair with every strand delineated. The commercial for Jovan featured a picture-perfect imitation of a Frank Frazetta illustration. Even the mountain on the background had to be animated and rendered.

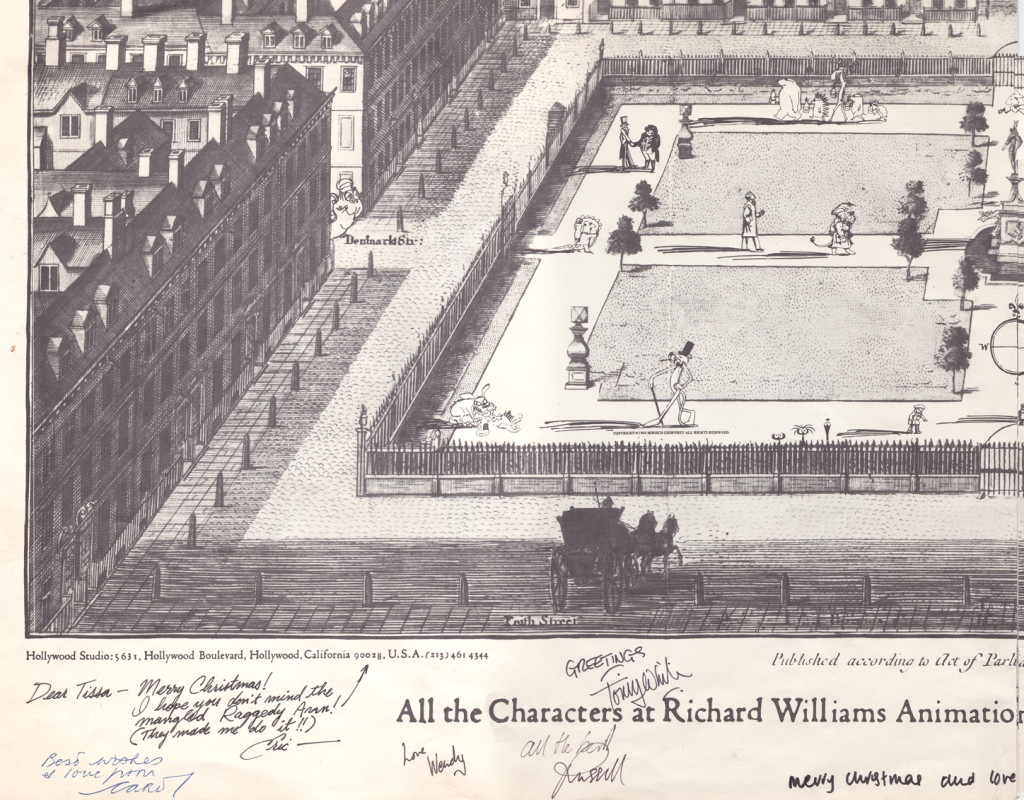

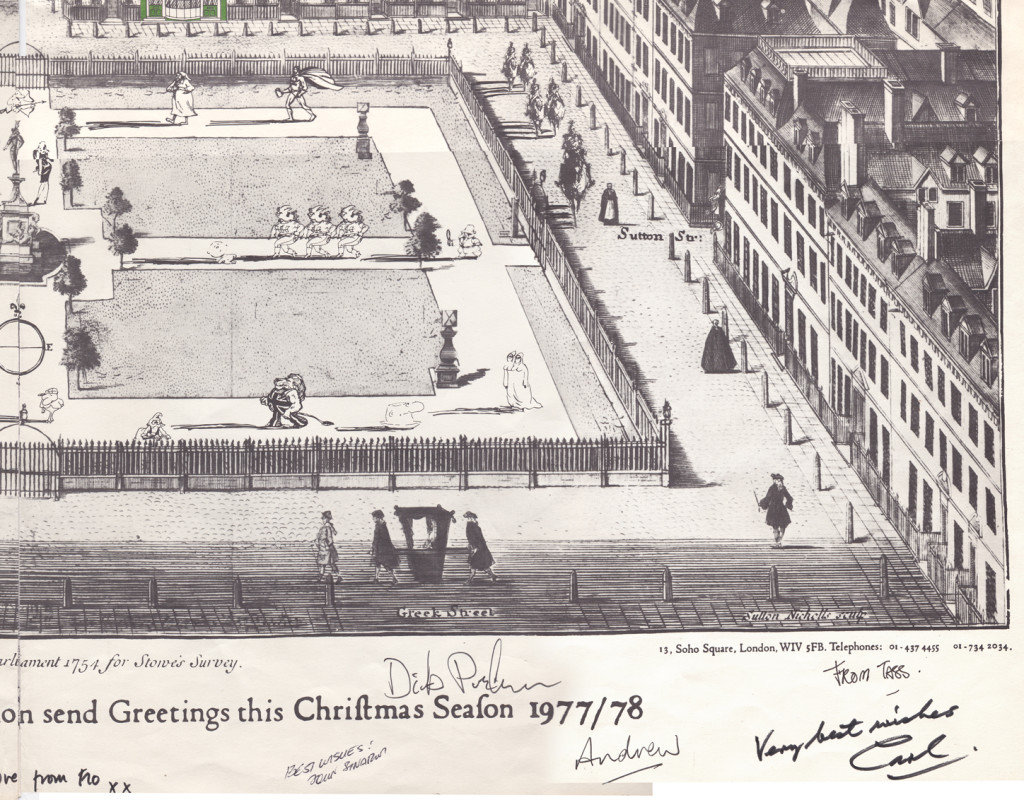

Well, when it came to Christmas cards, Richard Williams was the same. Enormous and beautiful cards were printed and signed by anyone who knew the recipient of the card. You were lucky being on the receiving line for these stunning cards. Tissa David once gave me a number of these cards. I held onto my copies of the cards until my space was flooded and the cards were damaged. I thought I’d post a few.

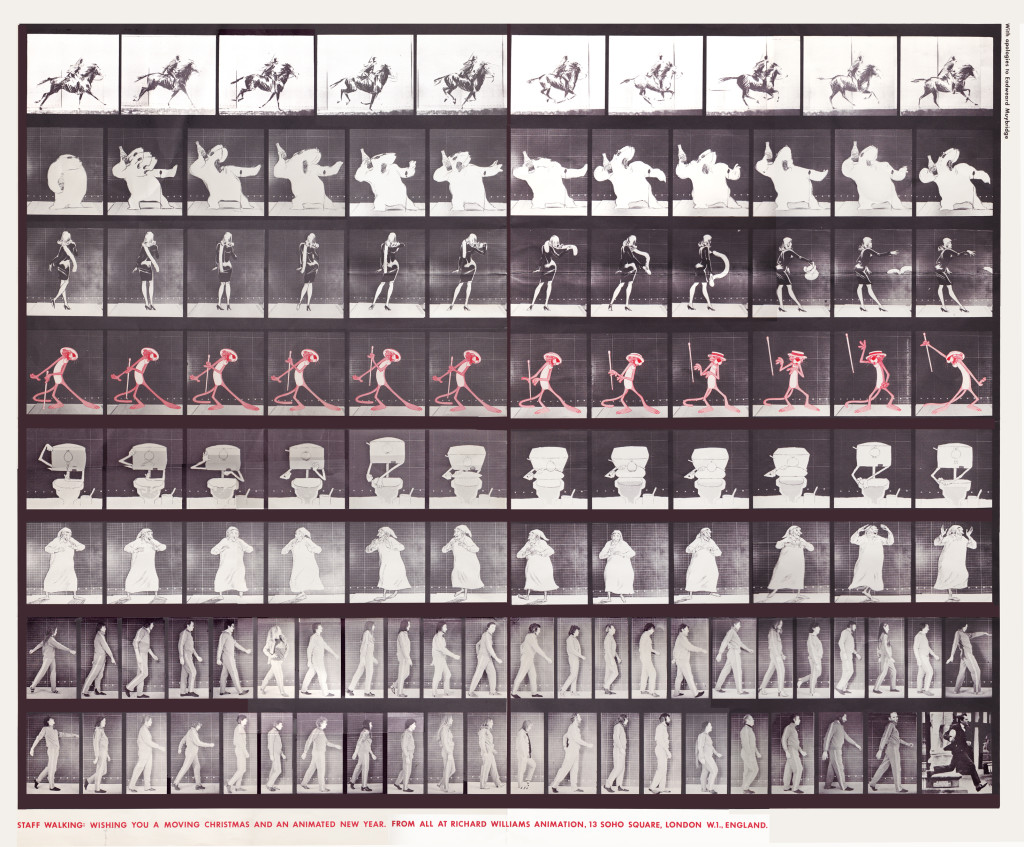

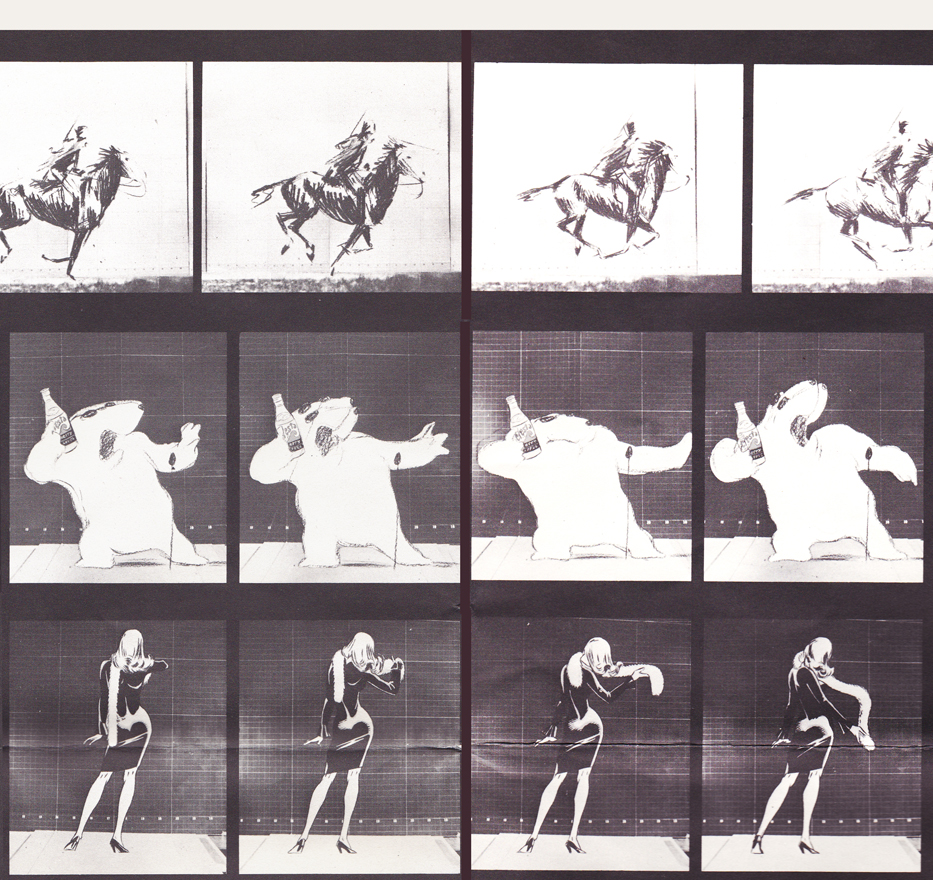

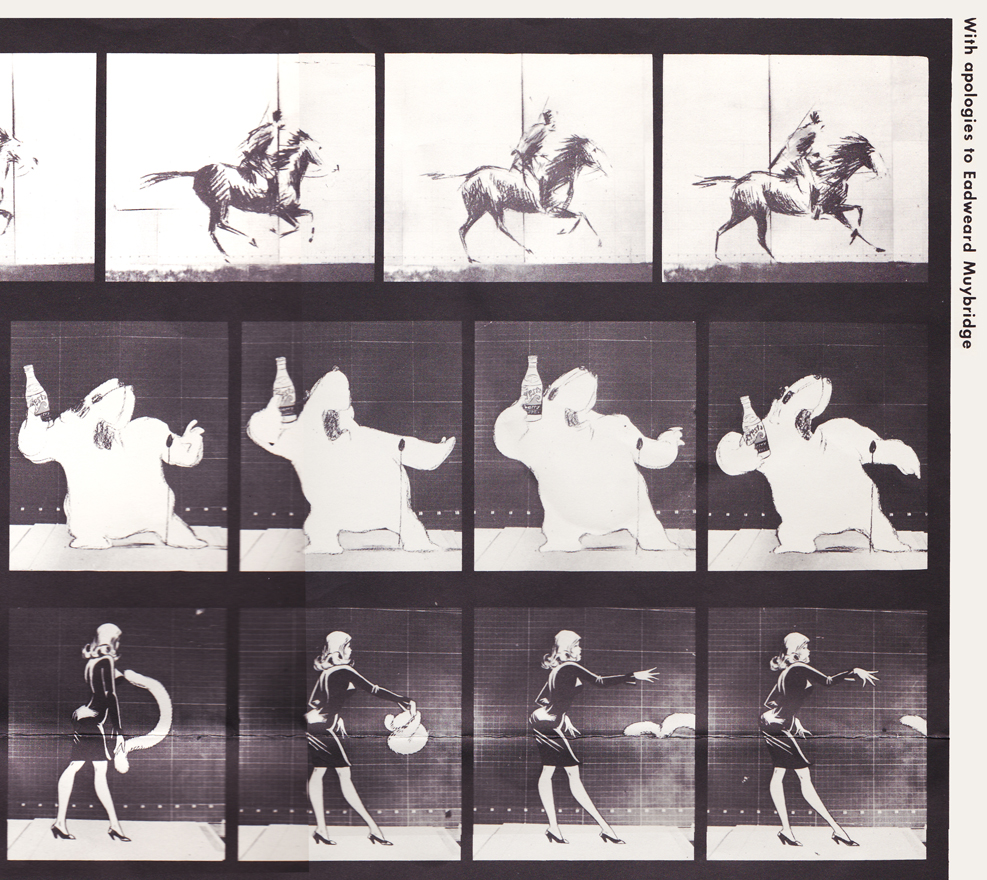

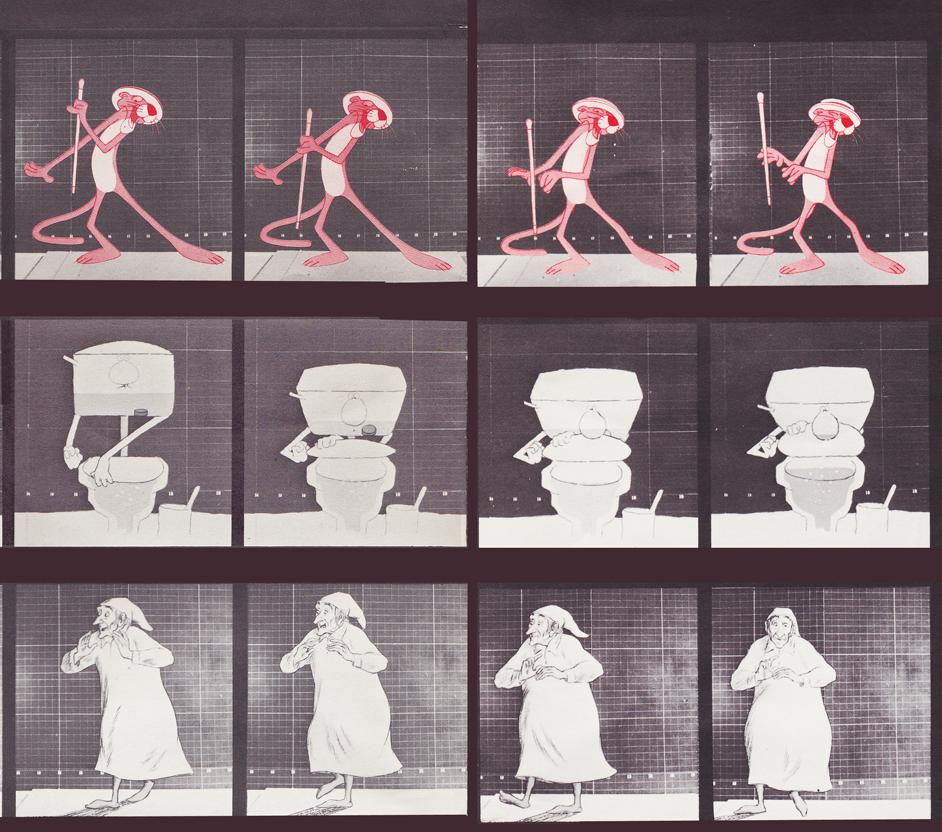

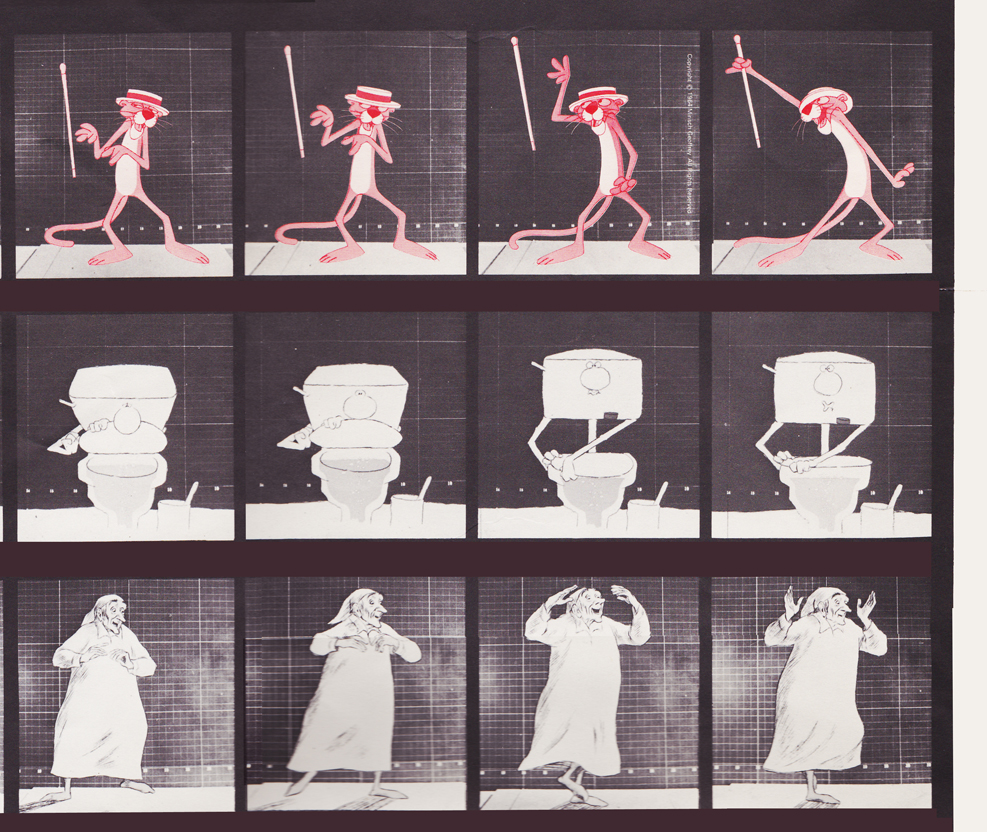

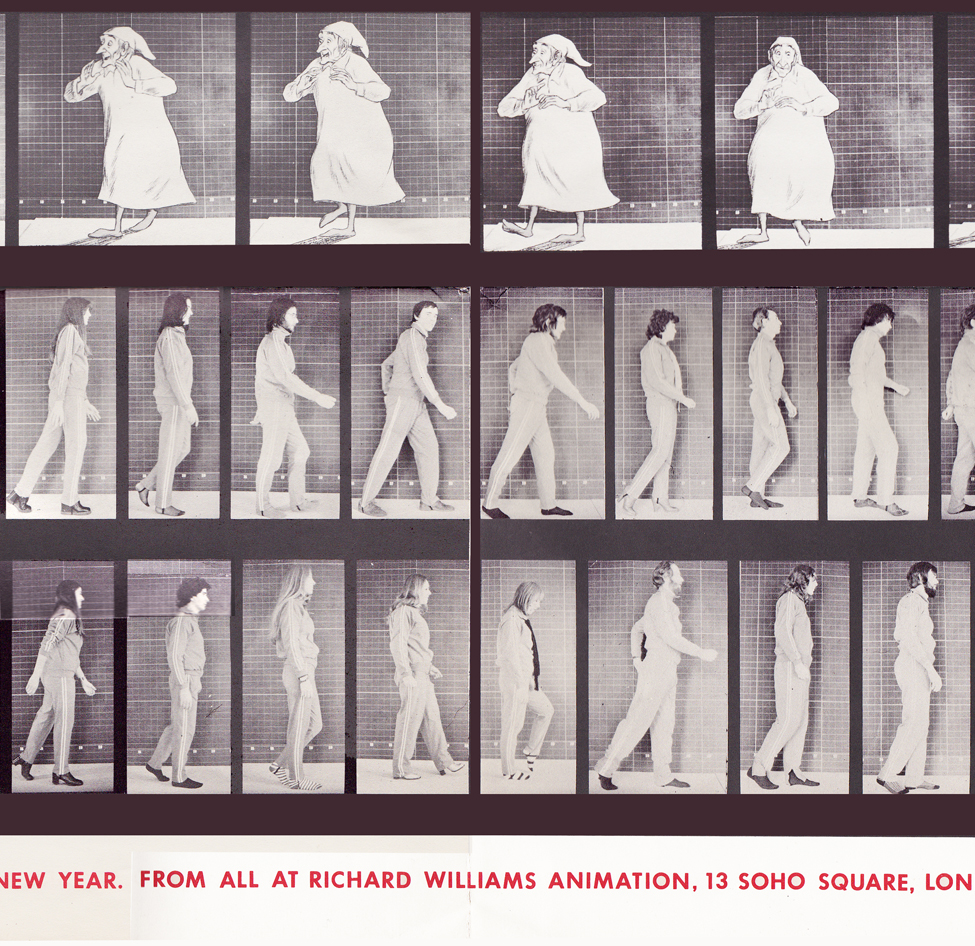

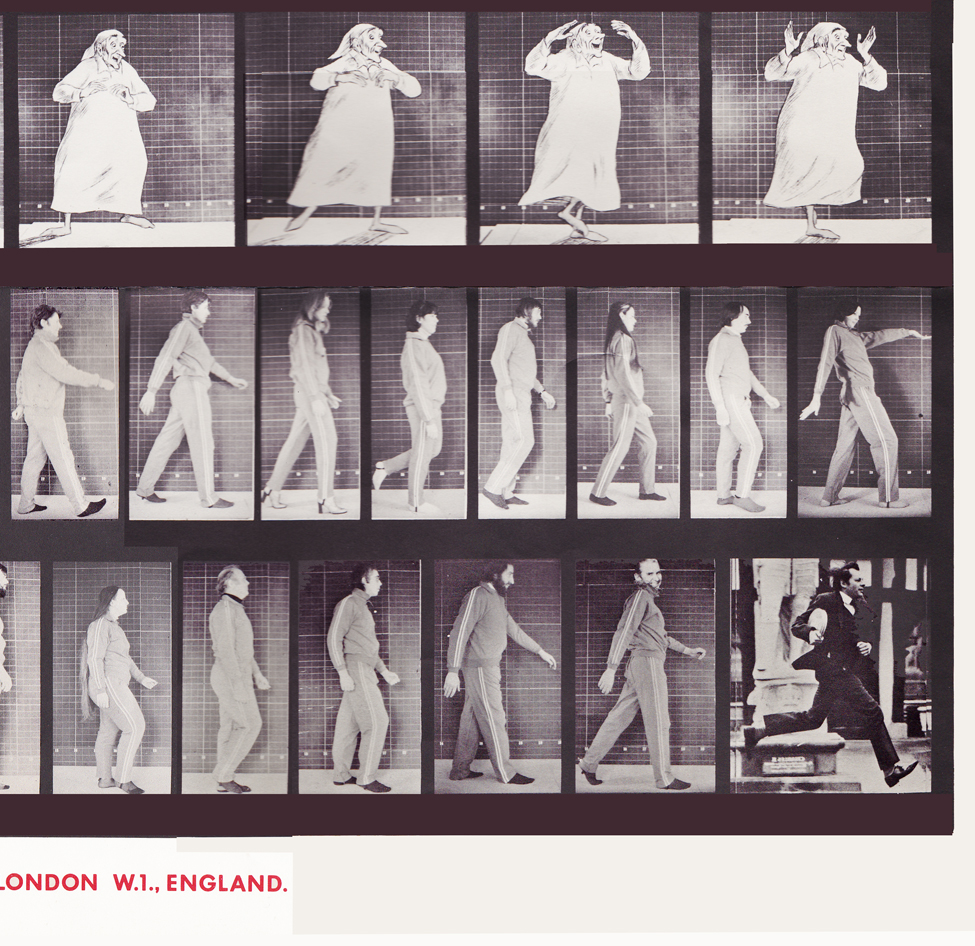

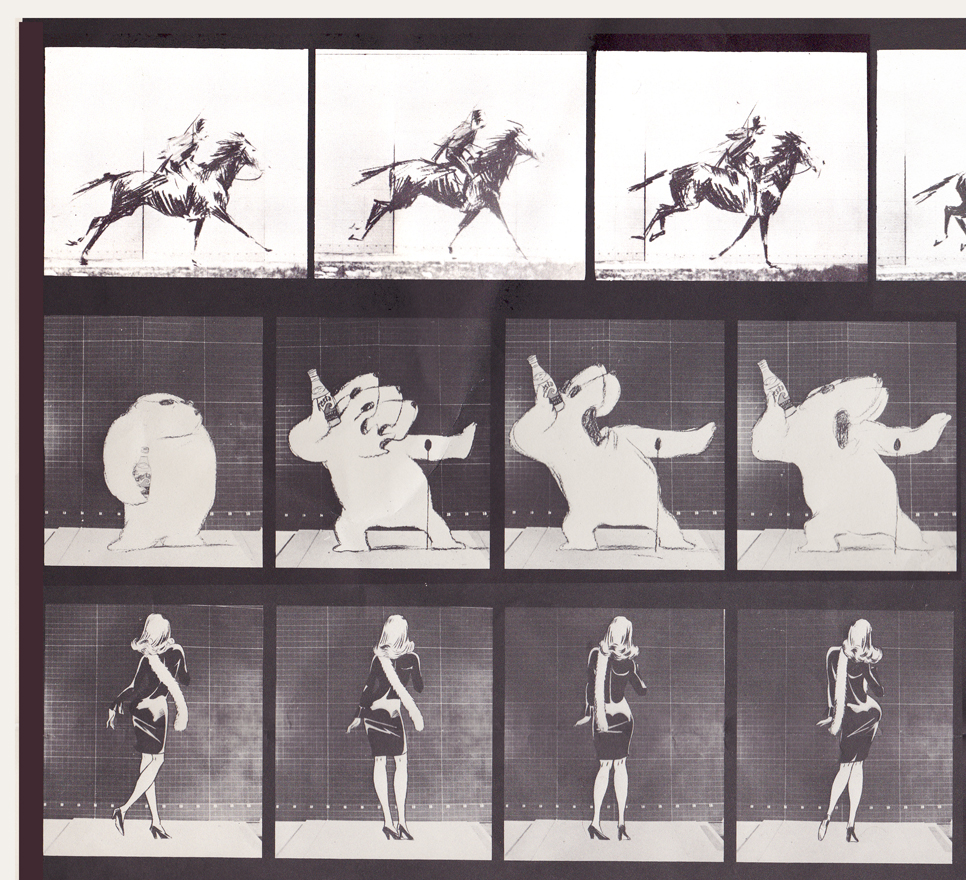

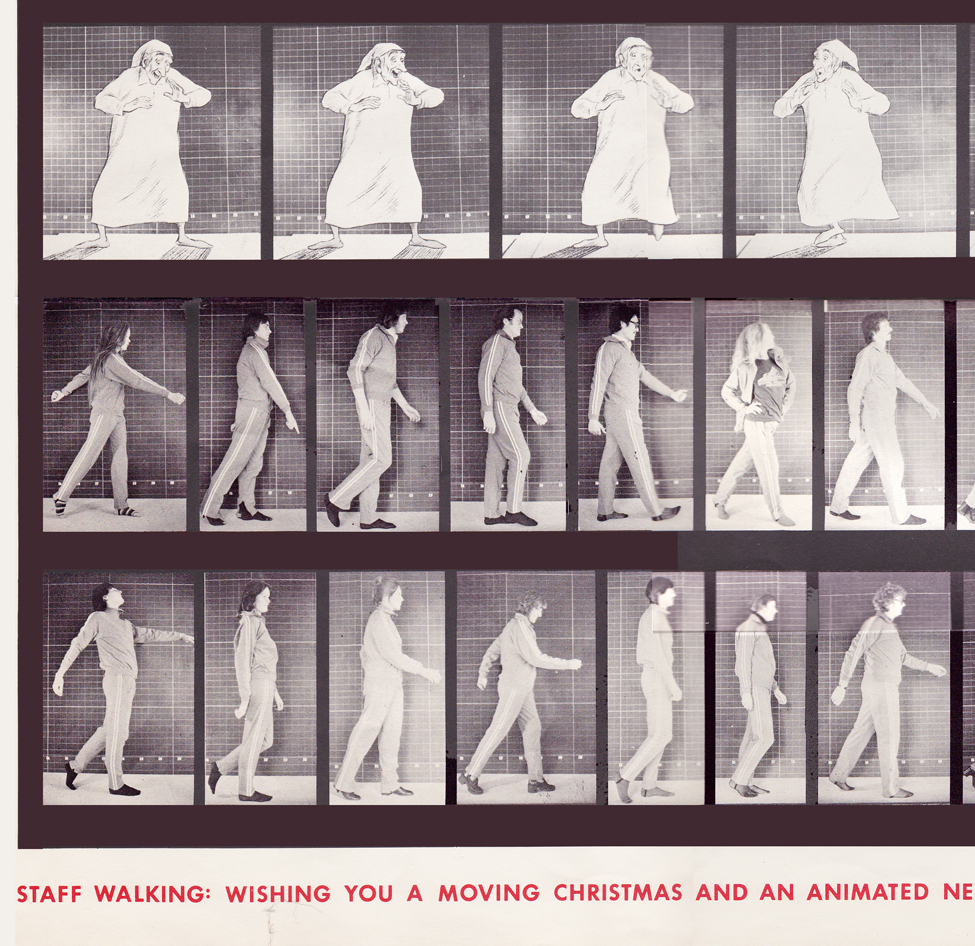

With card #1, a take-off of Muybridge with frame grabs from several of the better Williams commercial spots from that year, capped off by a number of key staff personnel positioned to continue the Muybridge motif.

(Here, I first post the entire card, followed by a break up of the card into sections

so you can more ably see the details.)

Top rows left side / Row 1: Pushkin Vodka ad

Row 2: Cresta Bear ad / Row 3. Tic Tac ad

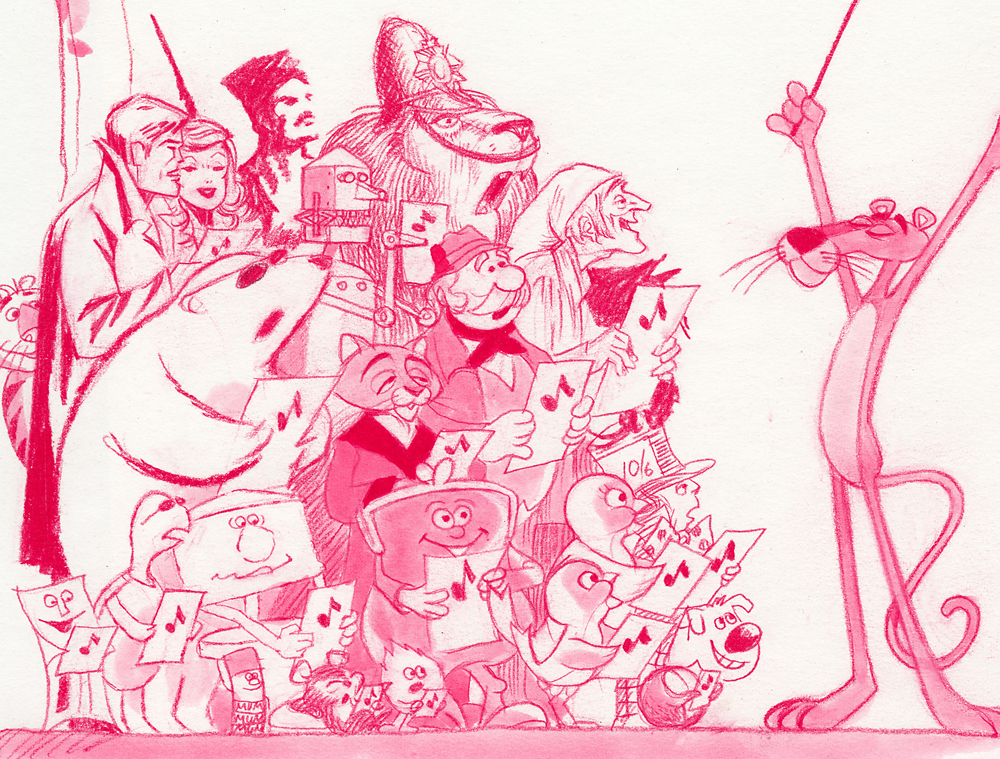

Middle rows left side / top row: Pink Panther titles

Middle row: Bloo toilet cleanser ad / Bot row: The Christmas Carol

Bottom rows left side / top row: The Christmas Carol (repeated)

Middle row: staff / bottom row: more staff

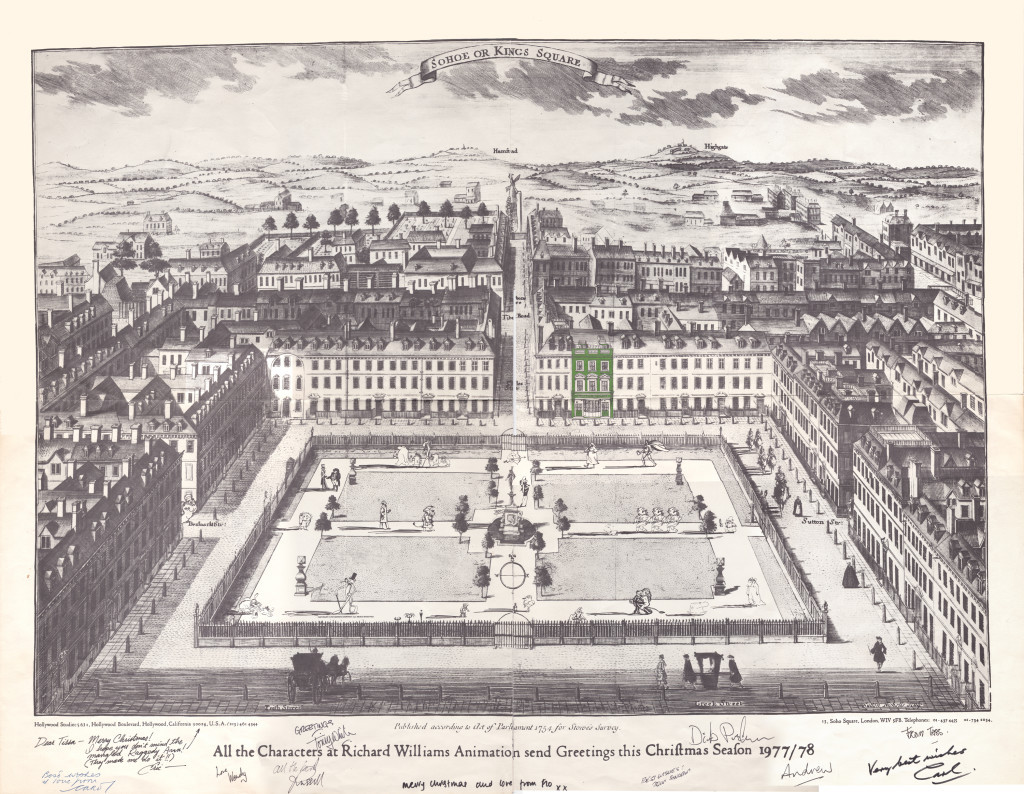

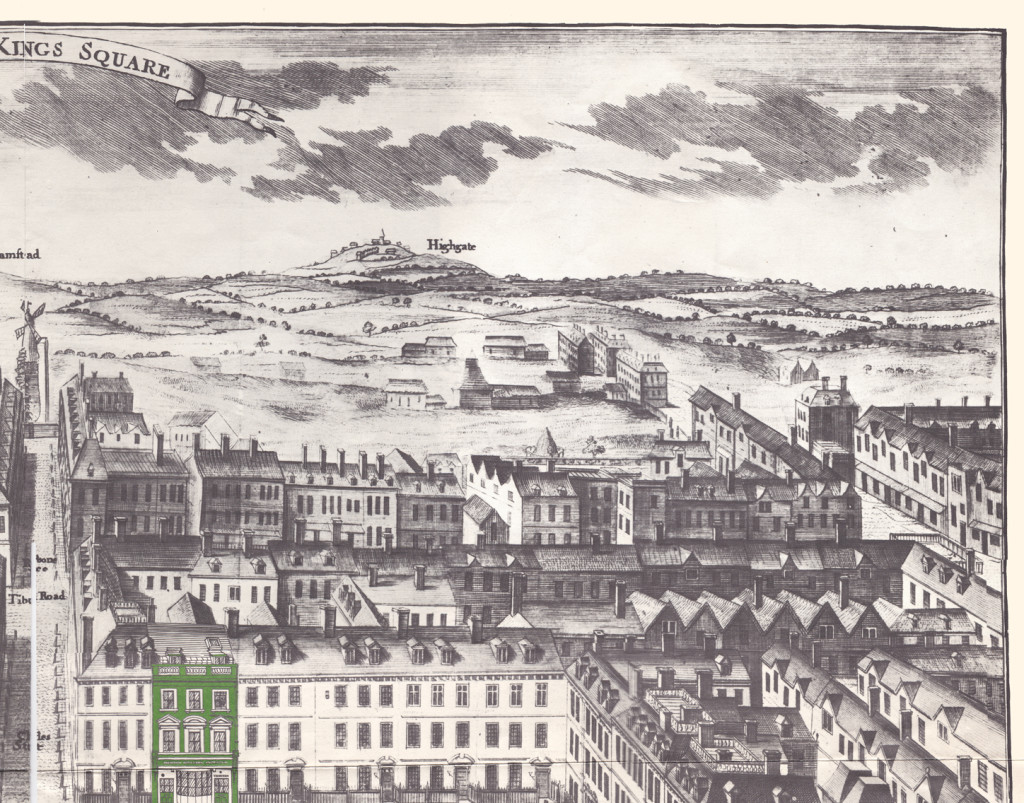

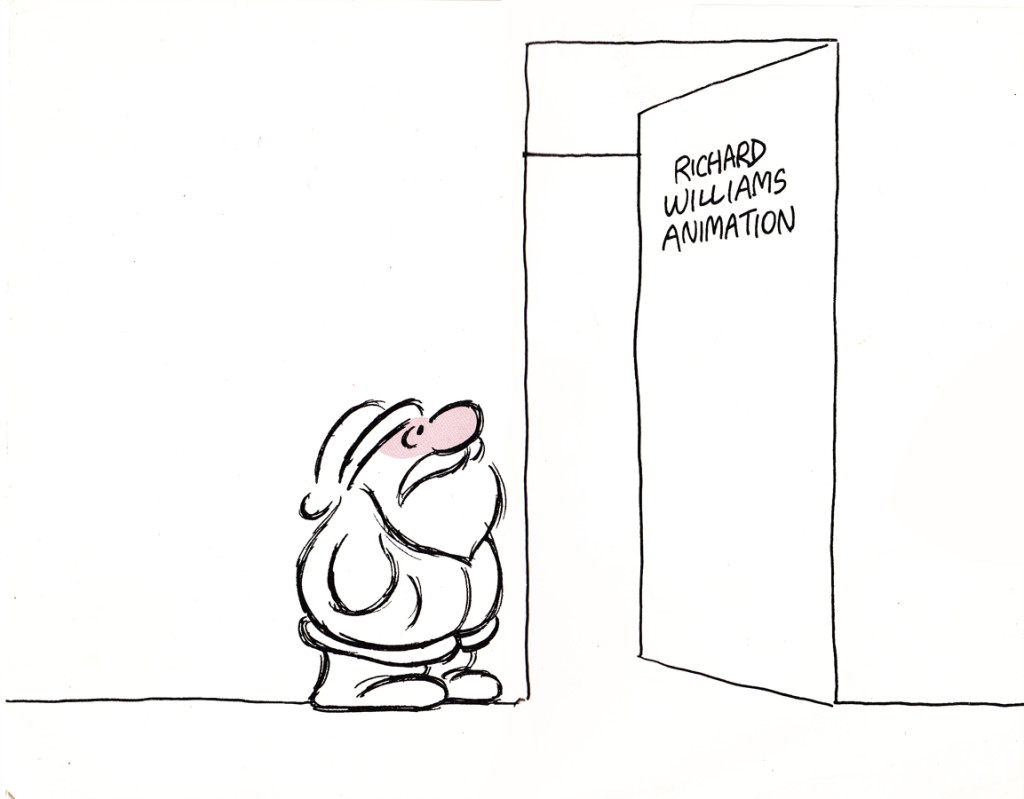

With card #2 we see Soho Square. The green front door

marks the location of Dick’s studio at 13 Soho Square.

(As with the first card, I posted the entire Christmas card,

followed by a sectional divide so you can enjoy the details.)

This is a folding card.

It comes folded so that you see the far left of the card

revealing part of the far right.

The card comes folded like this.

The left side (Santa up to doorway) is on the left side of the card.

The right side, on bottom, reveals the empty office.

It unfolds to reveal this long line of Santas.

Each Santa is in the style of the many illustrators’ styles

of those who designed ads for the studio in the prior year.

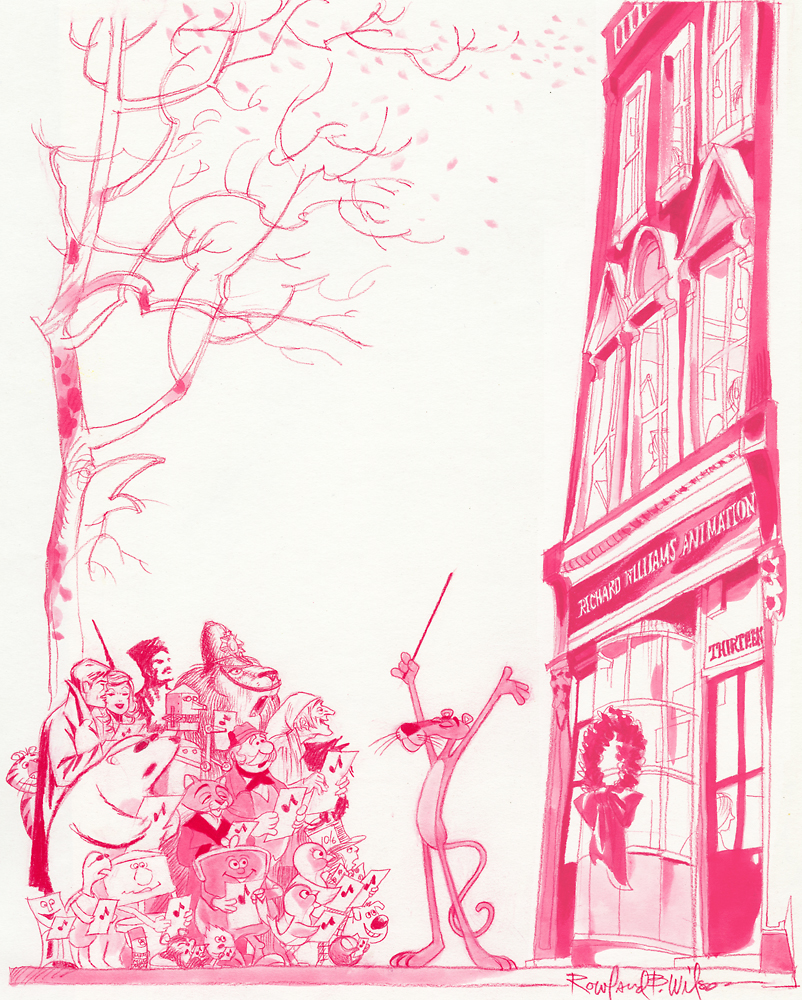

Suzanne Wilson sent in a Pink Panther Chistmas card; it was drawn by her late husband Rowland Wilson:

Below is a close up of that same card.

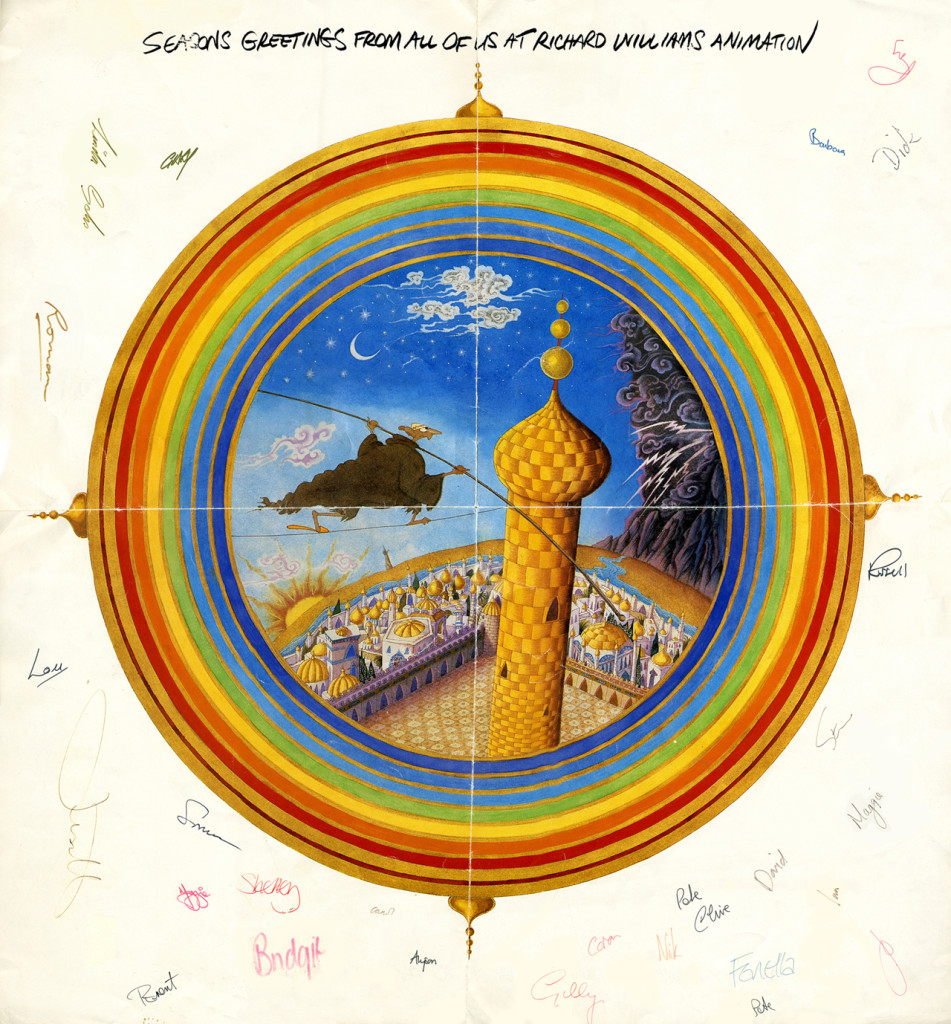

Here’s another full card.

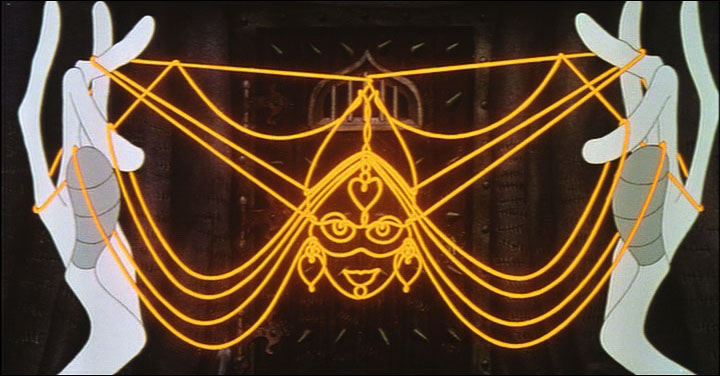

This one is designed after the McGuffin of Dick’s feature,

three golden balls over the city.

from The Thief and the Cobbler.

Action Analysis &Animation &Animation Artifacts &repeated posts &Richard Williams &Tissa David 27 Mar 2013 04:26 am

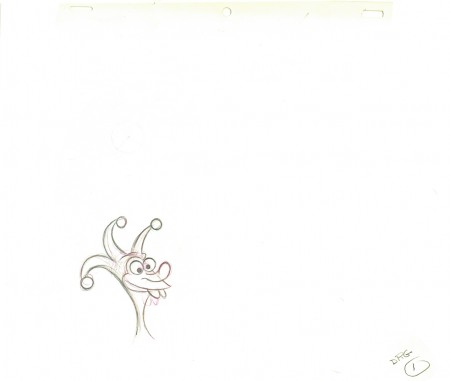

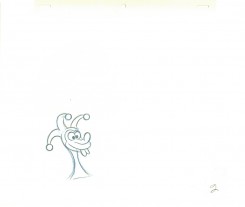

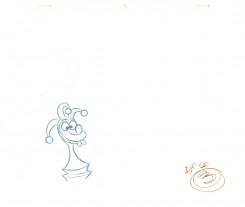

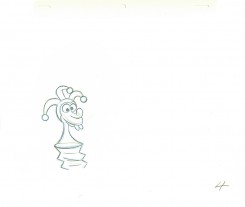

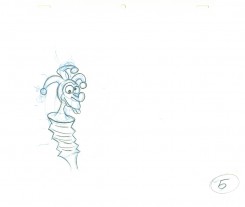

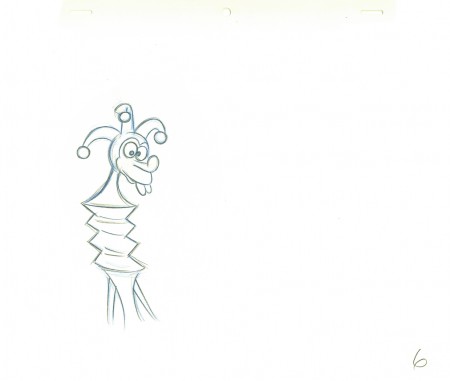

Grim’s Jester – recap

- Yesterday I focused on a couple of scenes Grim Natwick animated in his early days at the Fleischer studio. He was obviously experimenting with distortions, breaking of the joints, the visibility of inbetween drawings and how much he could get away with in “Rough drawings.”

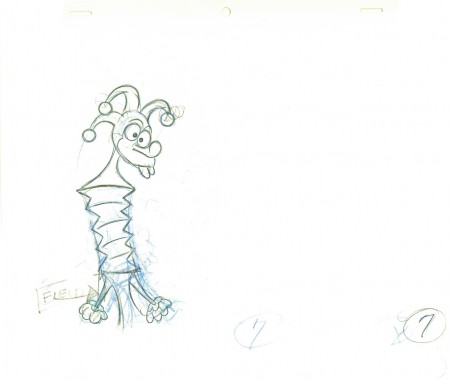

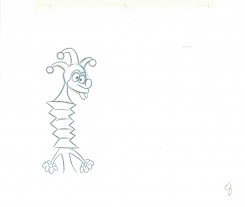

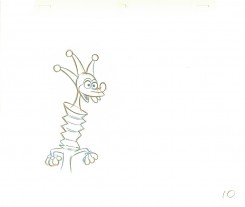

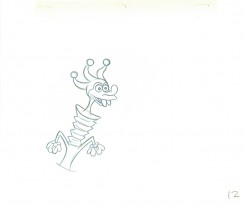

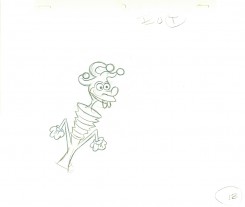

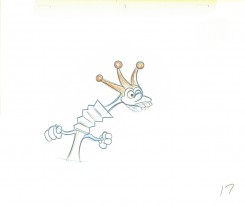

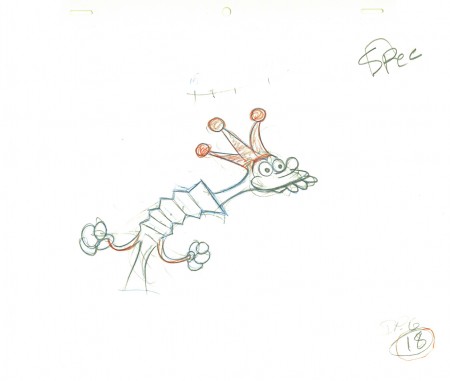

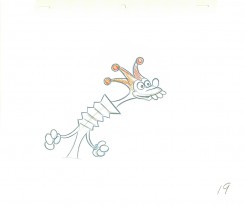

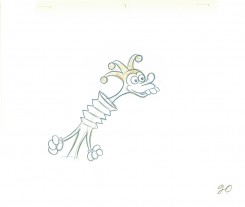

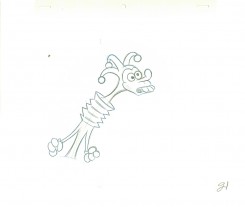

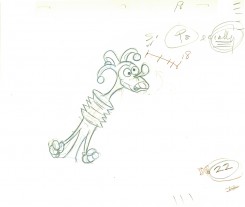

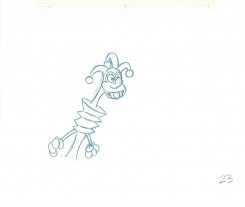

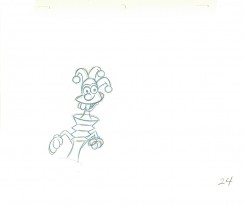

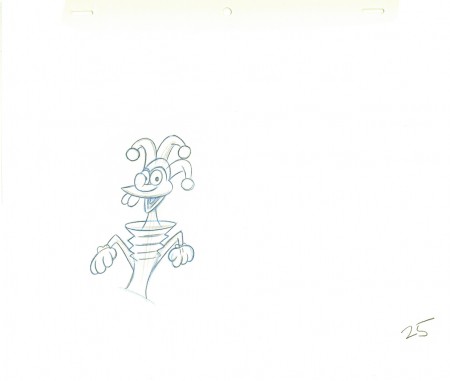

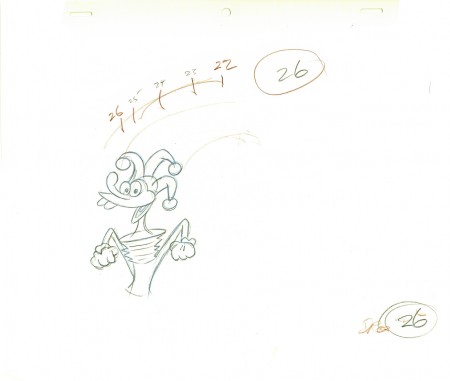

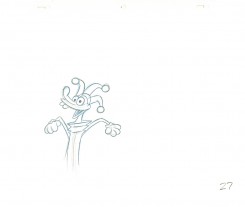

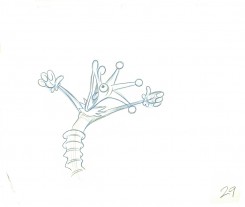

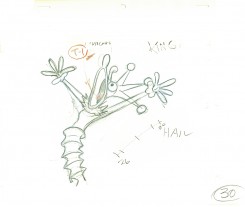

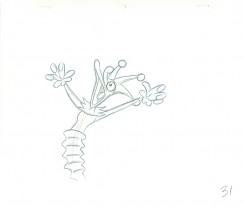

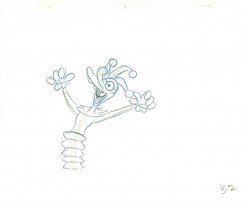

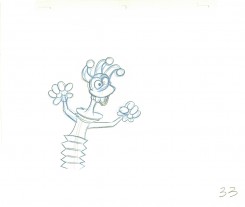

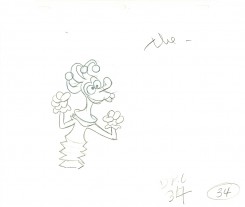

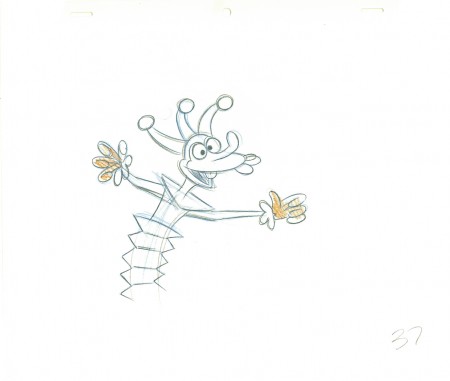

This, of course, isn’t the animator that Grim became, but gives us some light to understand what did make up that animator. The scene here today is something I’d posted on my blog once before, in 2010. It features a lot of Grim’s ruffs as well as the clean ups by Richard Williams, himself.`

You can see Grim’s drawings erased and cleaned up. (The semi-erased semblance of Grim’s very large numbers remain on many of the drawings, as do Grim’s notes. The inbetweens were all done by Dick. (It’s Dick’s writing in the lower right corner, and I remember him doing this overnight.)

The scene is all on twos. There are two holds which Dick changed to a trace back cycle of drawings for a moving hold. It actually looks better on ones, but there was a lip-synch that Grim had to follow. It is interesting that both Tissa David, one of the five key animators on this film, and Grim Natwick, who Tissa had assisted for at least 20 years, both shared the one assistant on key scenes in this film – Richard Williams. Eric Goldberg assisted on many of Tissa’s other scenes.

1

1.

2

2  3

3.

4

4  5

5.

6

6An inbetween by Dick Williams.

.

7

7A cleaned-up extreme by Grim Natwick.

.

8

8  9

9.

10

10 11

11.

12

12 13

13.

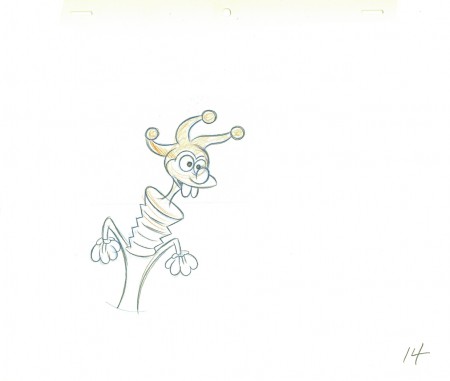

14

14Dick Williams clean-up.

.

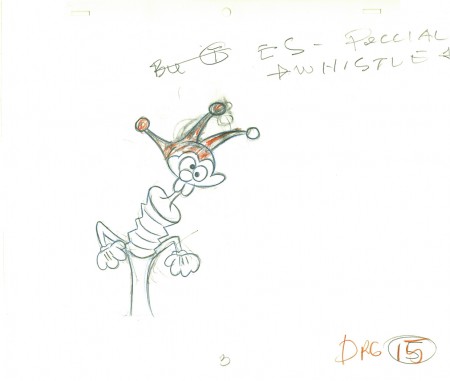

15

15Grim Natwick (sorta) cleaned-up rough.

.

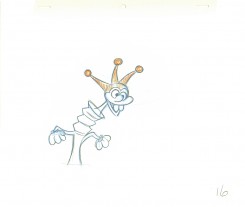

16

16 17

17.

18

18Grim Natwick rough.

.

19

19 20

20.

21

21 22

22.

23

23 24

24.

25

25Williams inbetween.

.

26

26Natwick ruff, cleaned up.

.

27

27 28

28.

29

29 30

30.

31

31 32

32.

33

33 34

34.

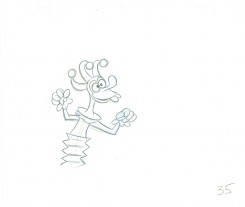

35

35 36

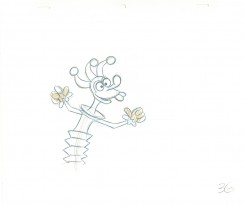

36.

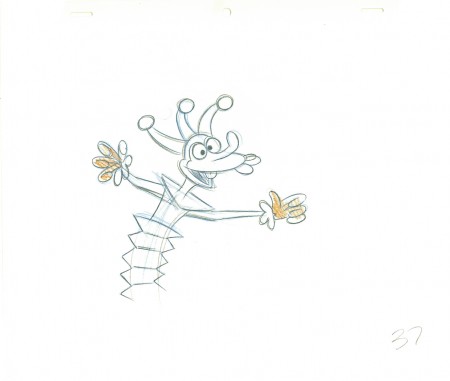

37

37Dick’s clean-up inbetween.

.

39

39Definitely a Grim Natwick drawing – cleaned up by Dick (his handwriting).

.

39

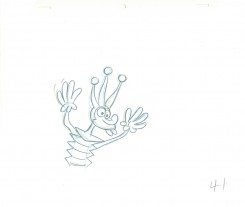

39 40

40.

41

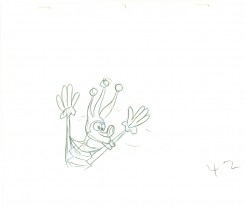

41 42

42.

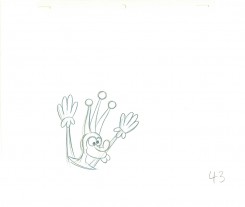

43

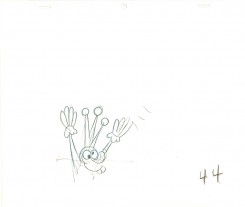

43 44

44.

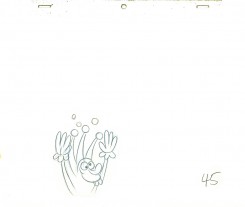

45

45 46

46.

47

47Drawings 44-47 are all Grim’s roughs with minor CU.

.

_____________________________

Here’s a QT movie of the complete action from the scene.

The scene is exposed on twos per exposure sheets.

_____________________________

Here are the folder in which the two exposure sheets

are stapled (so they don’t get separated.)

Commentary &Frame Grabs &Richard Williams &Title sequences 24 Mar 2013 03:38 am

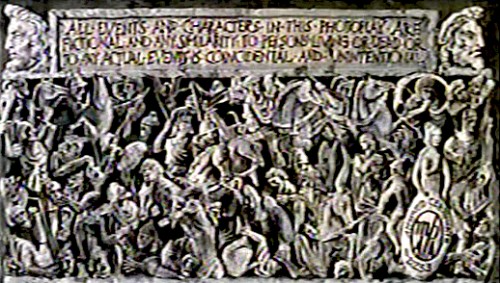

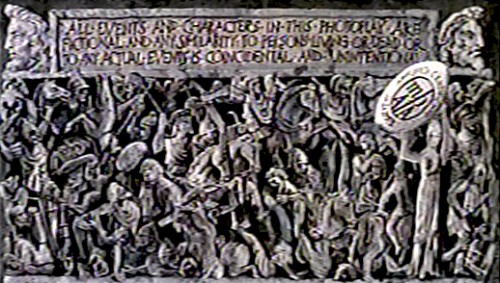

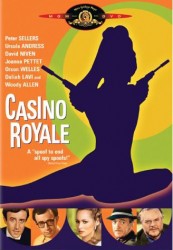

Dick Williams – Casino Royale Titles – recap

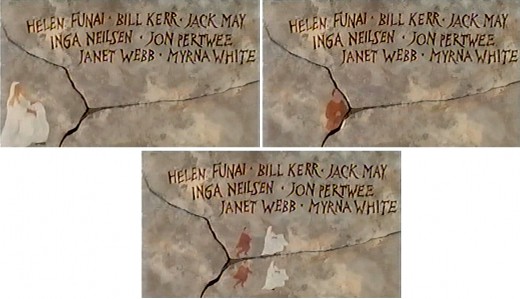

- Casino Royale (the 1967 original) was the fourth credit sequence animated by Richard Williams‘ Soho Square studio. Prior to this he’d directed What’s New Pussycat (1965), A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1966), and The Spy Who Came In From the Cold (1966).

- Casino Royale (the 1967 original) was the fourth credit sequence animated by Richard Williams‘ Soho Square studio. Prior to this he’d directed What’s New Pussycat (1965), A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1966), and The Spy Who Came In From the Cold (1966).

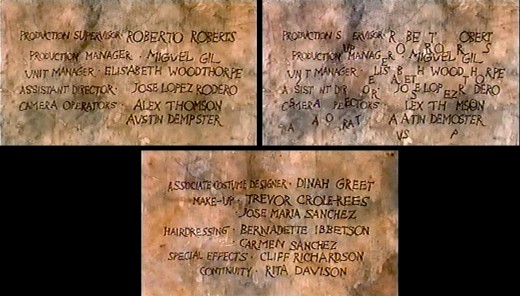

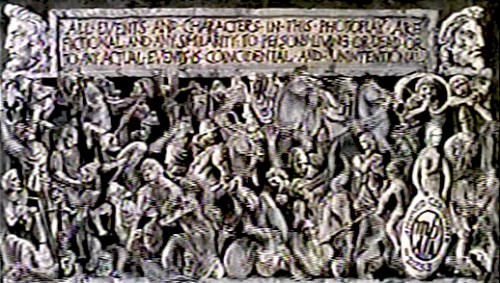

Continuing the presentation I’ve done of other title sequences by Williams, here’s Casino Royale. The other Williams credit sequences of the period are generally rambunctious items with almost too much happening on screen. It often gets hard to read the credits – in a theater, never mind trying to do it on TV. (God bless imdb.)

Theses are all frame grabs off a TV airing. My apologies for the horrendous quality. It aired on one of those cable channels that adds plenty of promos at the bottom of the screen (which I cleaned out of these images) overlapping many of the cards. They might have taken a bit more care to try to eliminate some distortion on the screen. The image skews, and the type gets distorted. I did my best with what I had. If I ever get my hands on a good dvd of the show, I’ll correct these images.

________________________ (Click any image to enlarge.)

____Joseph McGrath, Robert Parrish, and Richard Talmadge also directed but I

____eliminated their screen cards as repetitious.

Dick Williams’ version of the opening titles

And for the sake of amusement here are

The credits from the 2006 version of the film

Designed by Daniel Kleinman

Animation &Animation Artifacts &Articles on Animation &Richard Williams 20 Mar 2013 05:29 am

Dick Williams’ Notes

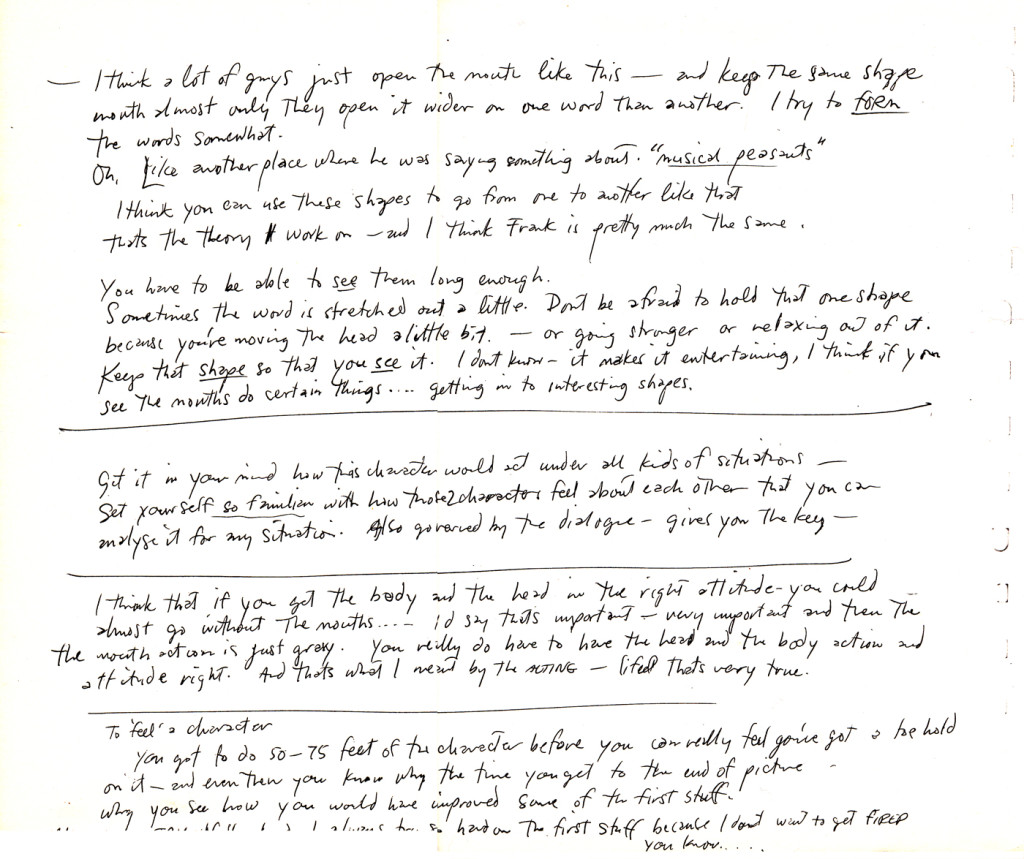

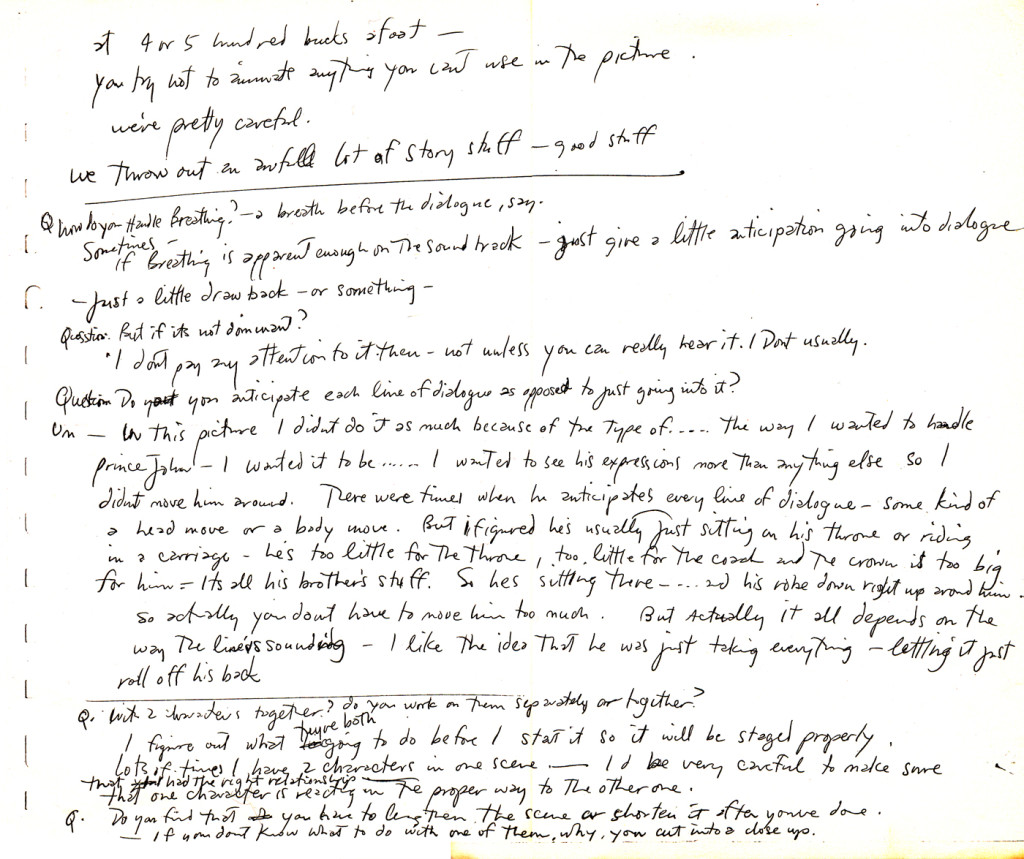

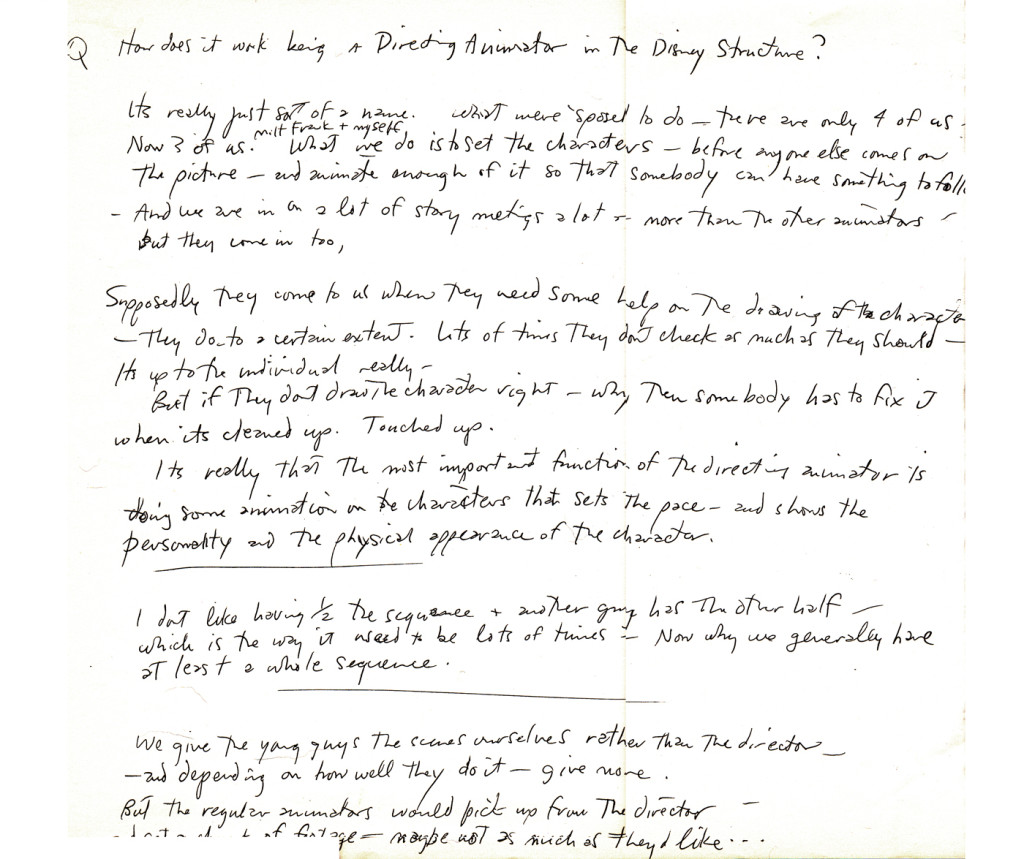

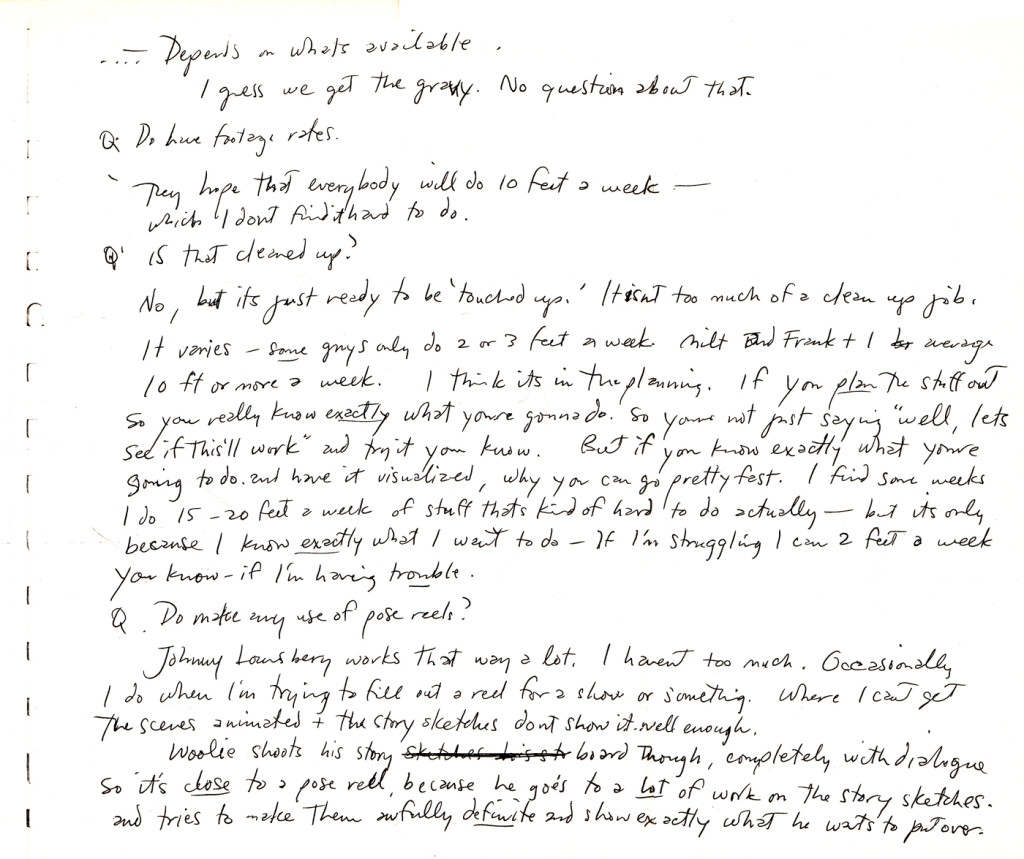

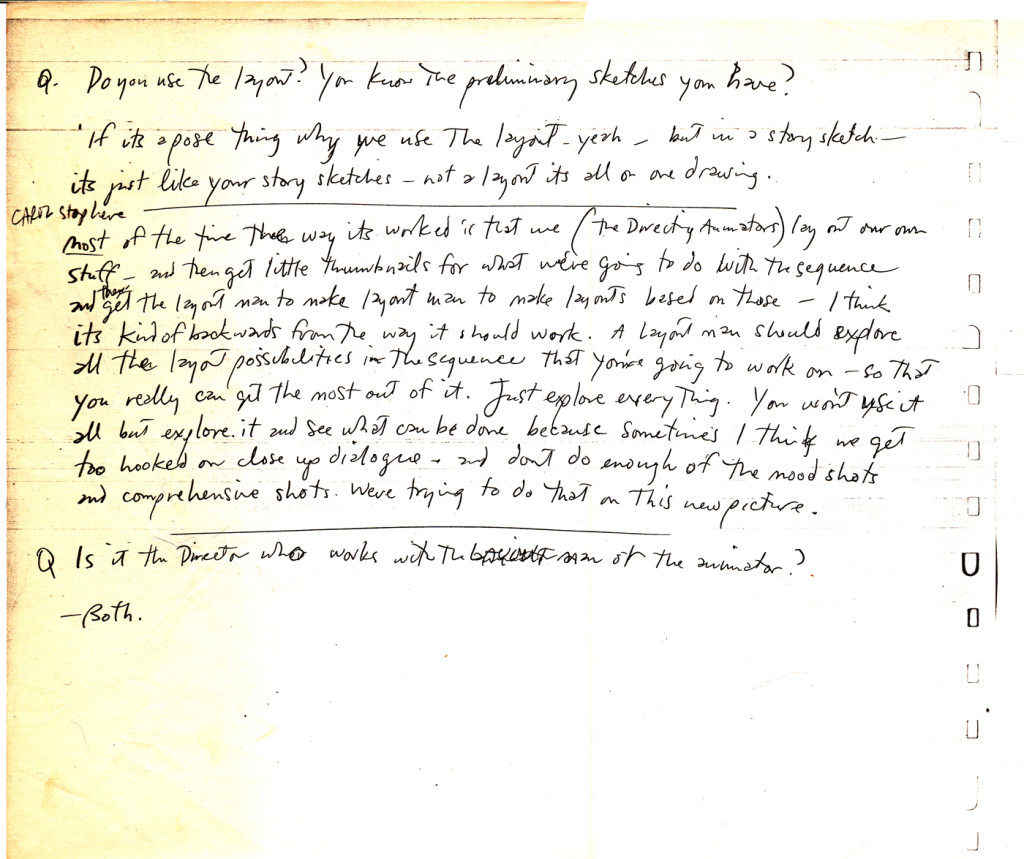

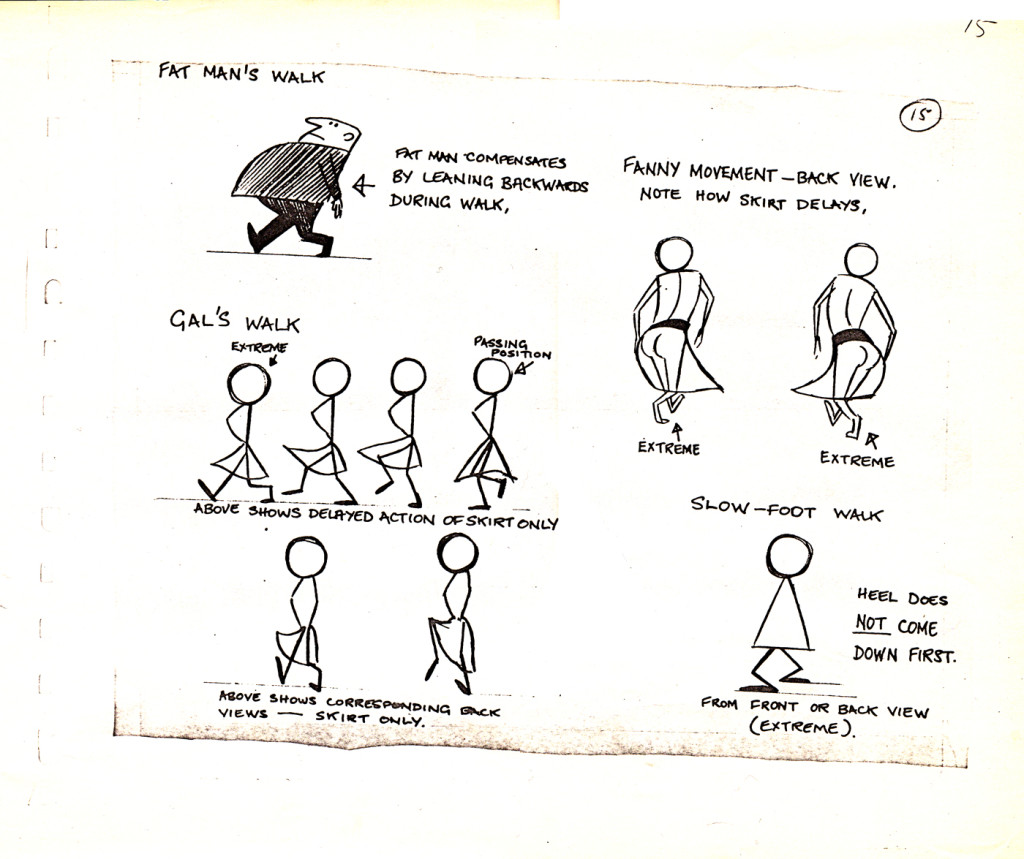

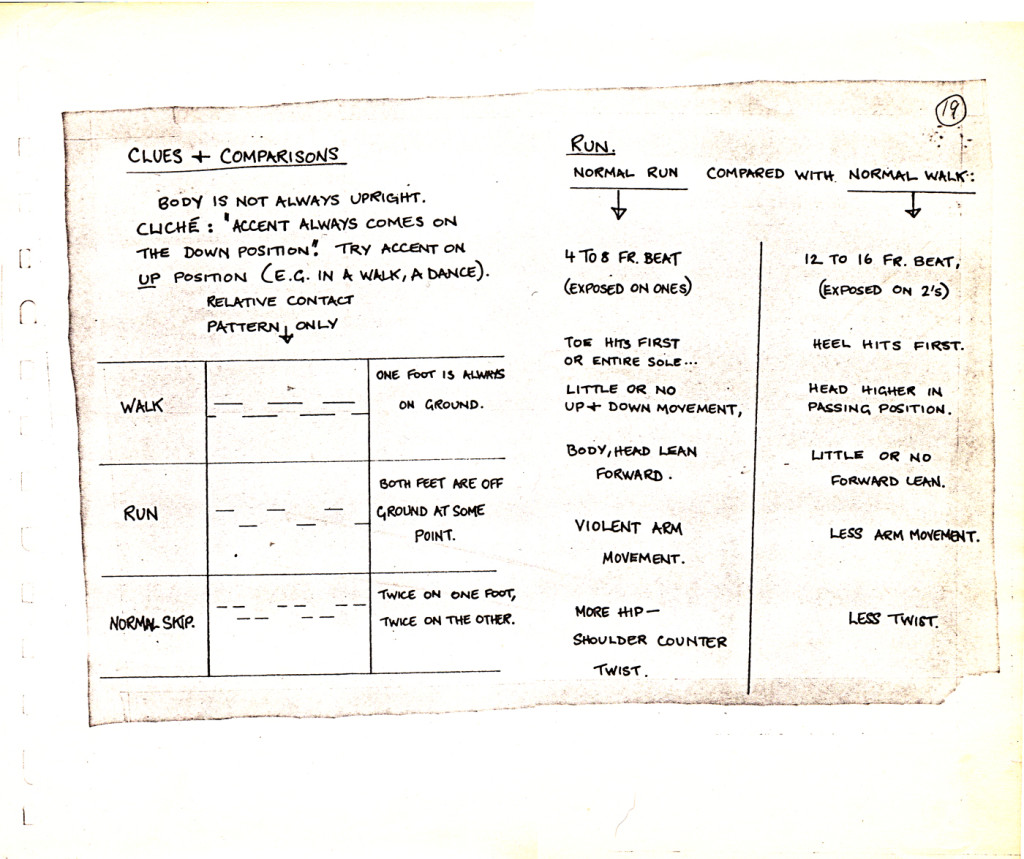

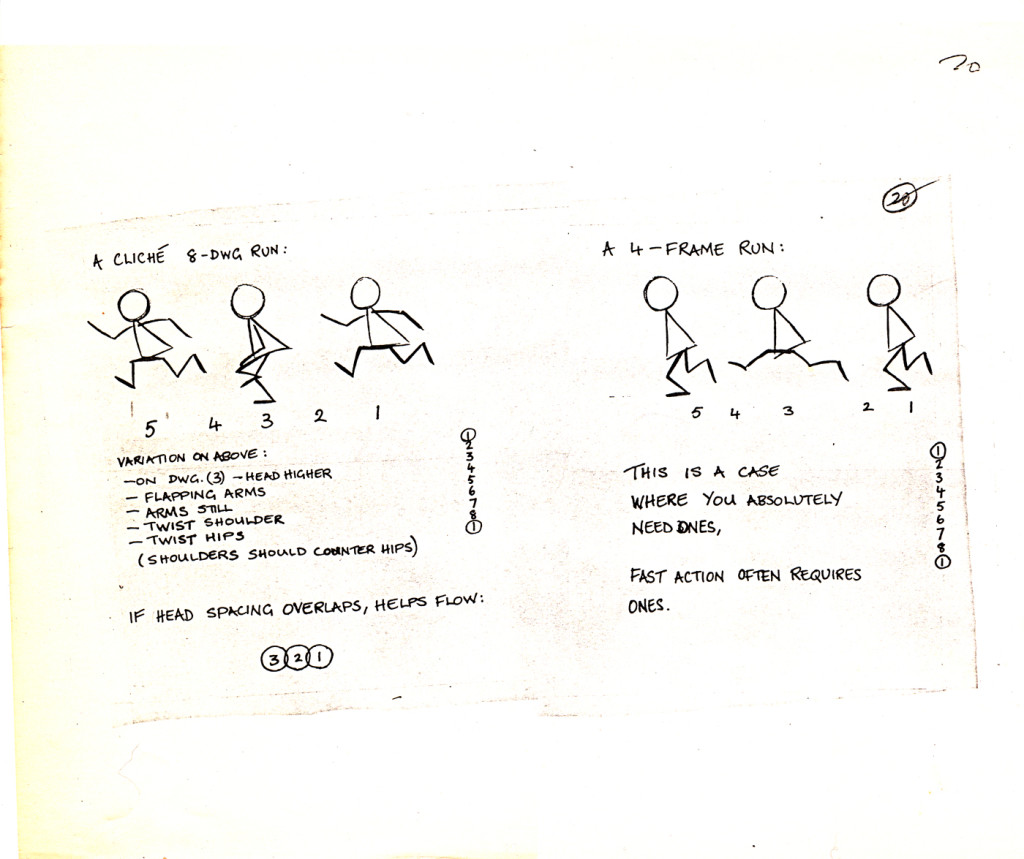

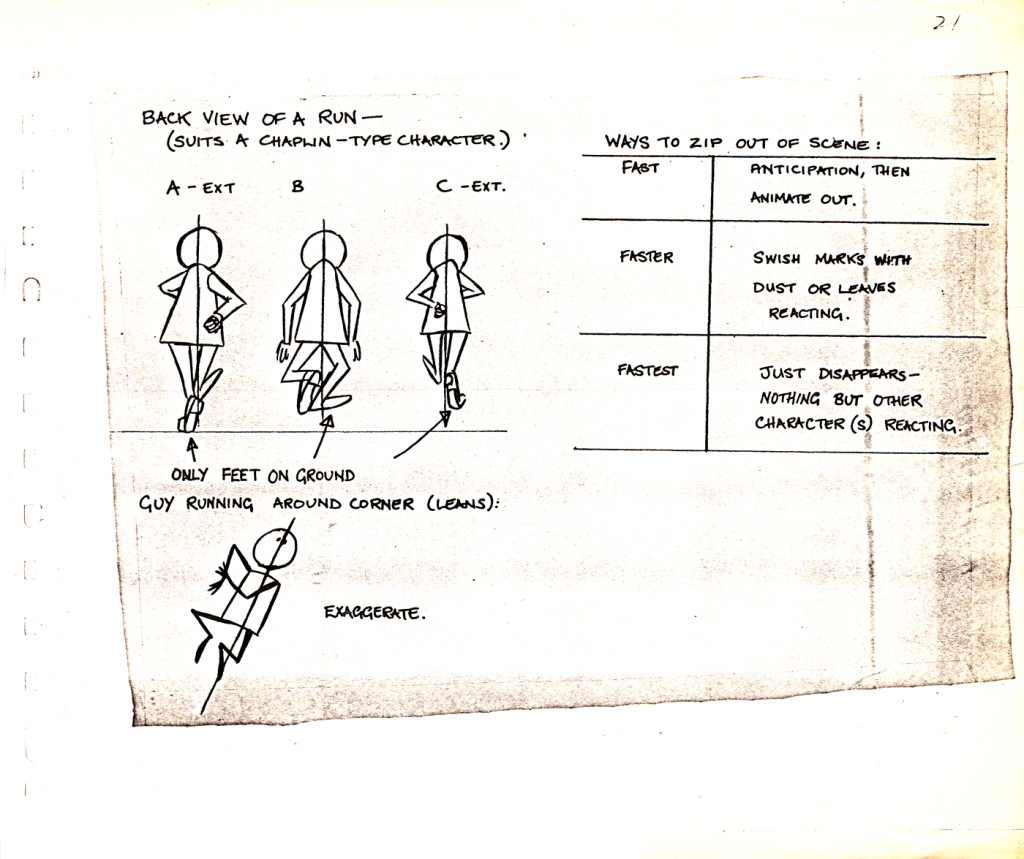

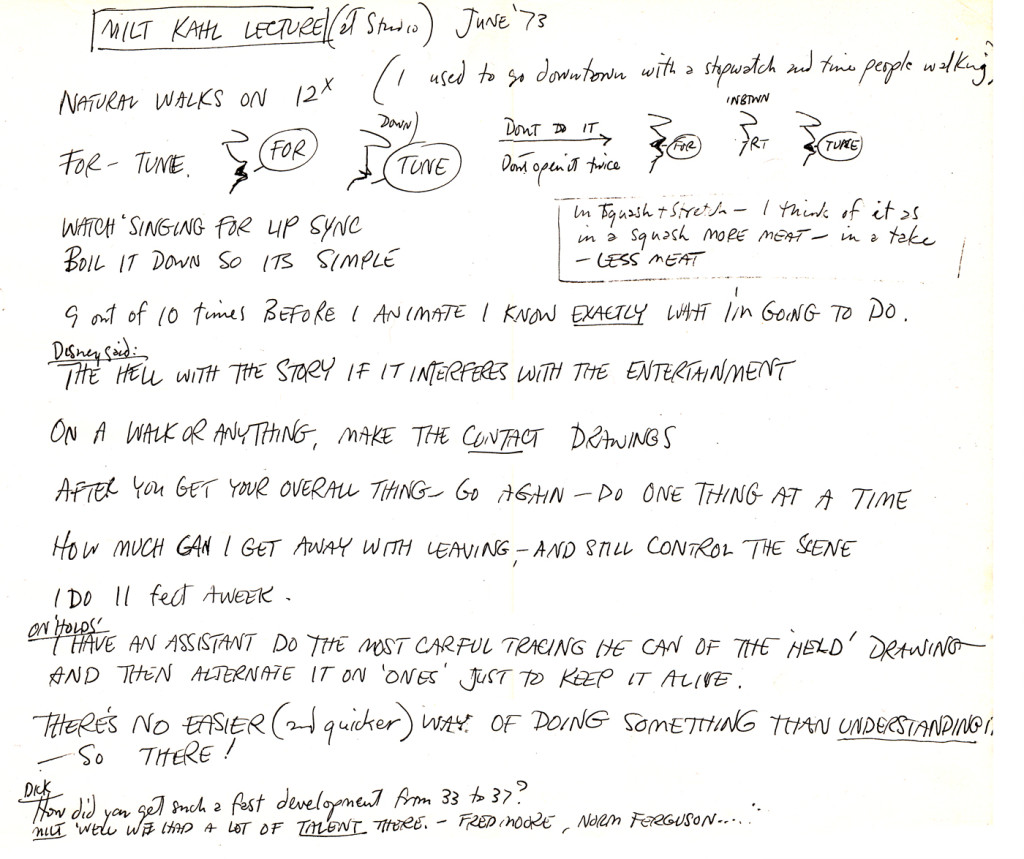

- One of the better pluses of working on Raggedy Ann, back in 1977, was the information available to us. There was circulated, there, a book of notes Richard Williams had kept during the lectures Art Babbitt had given at is studio in Soho Square. These still act as a unique bible I have on my shelf. (Unfortunately, these days it’s on a shelf in storage.)

There was also another set of notes. These weren’t 8½ x 11, they were 14 x 17 sheets of paper, and only a few had access. As one of the bosses there, I had access. (Basically, we couldn’t have everyone copying 14 x 17 sheets of paper; that got expensive.)

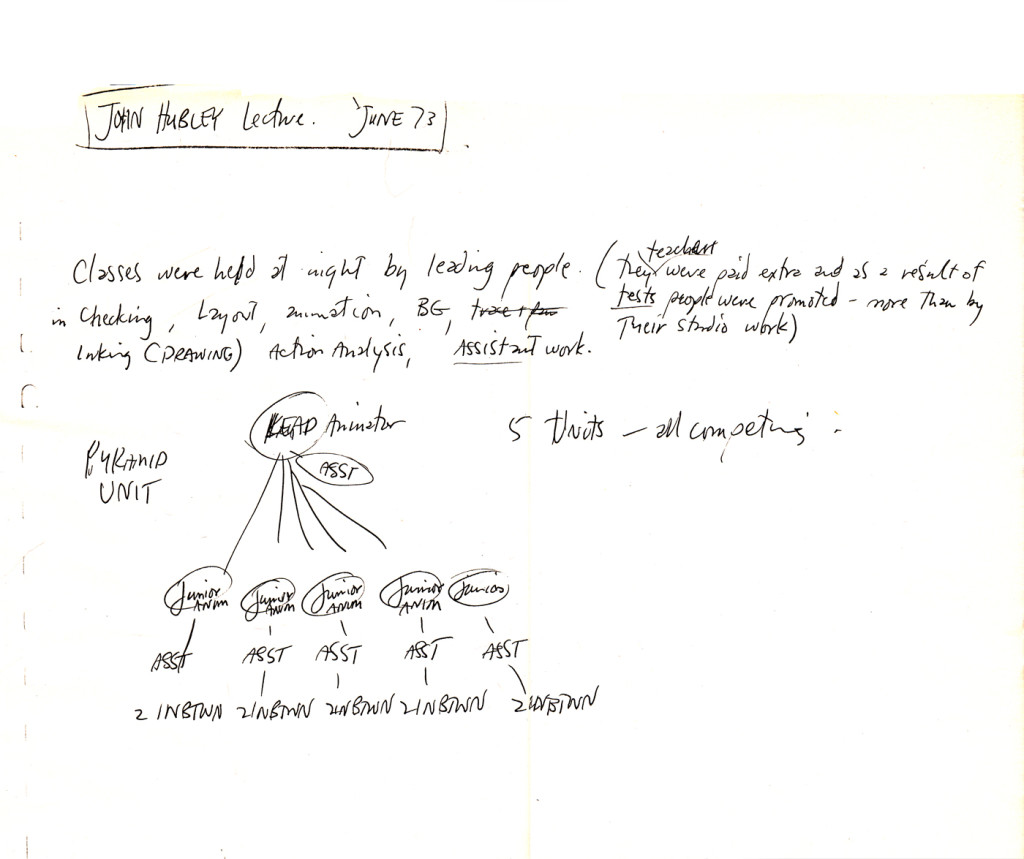

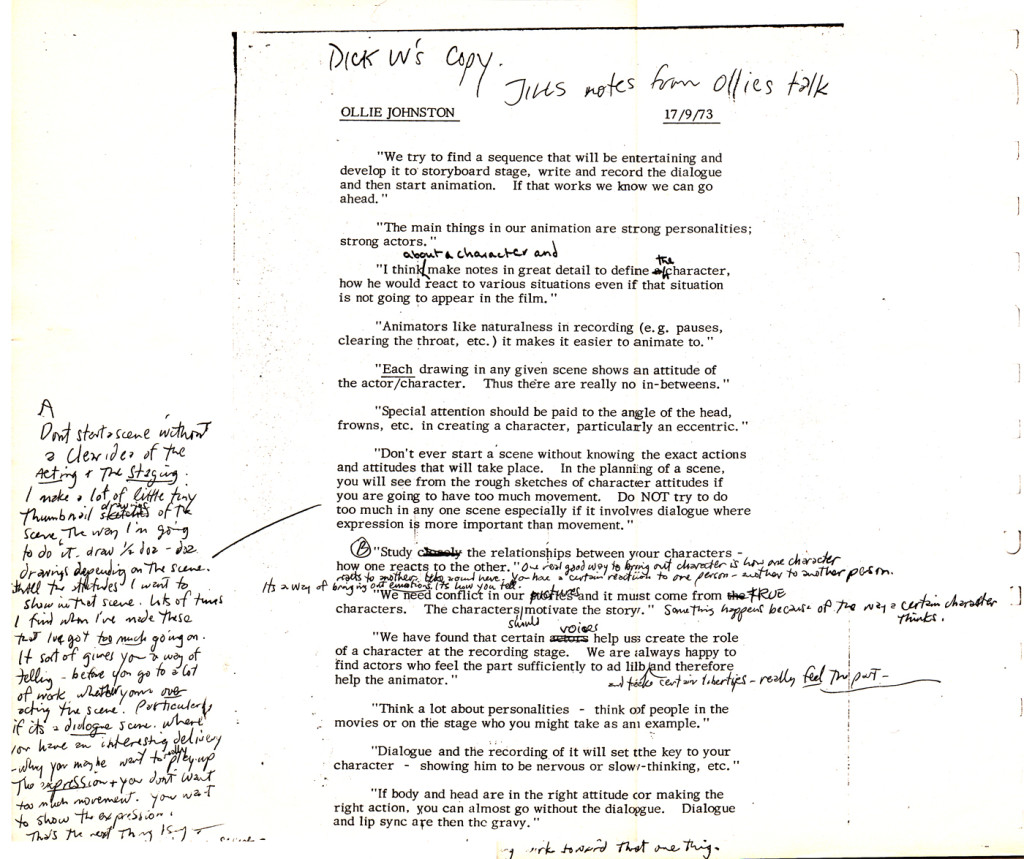

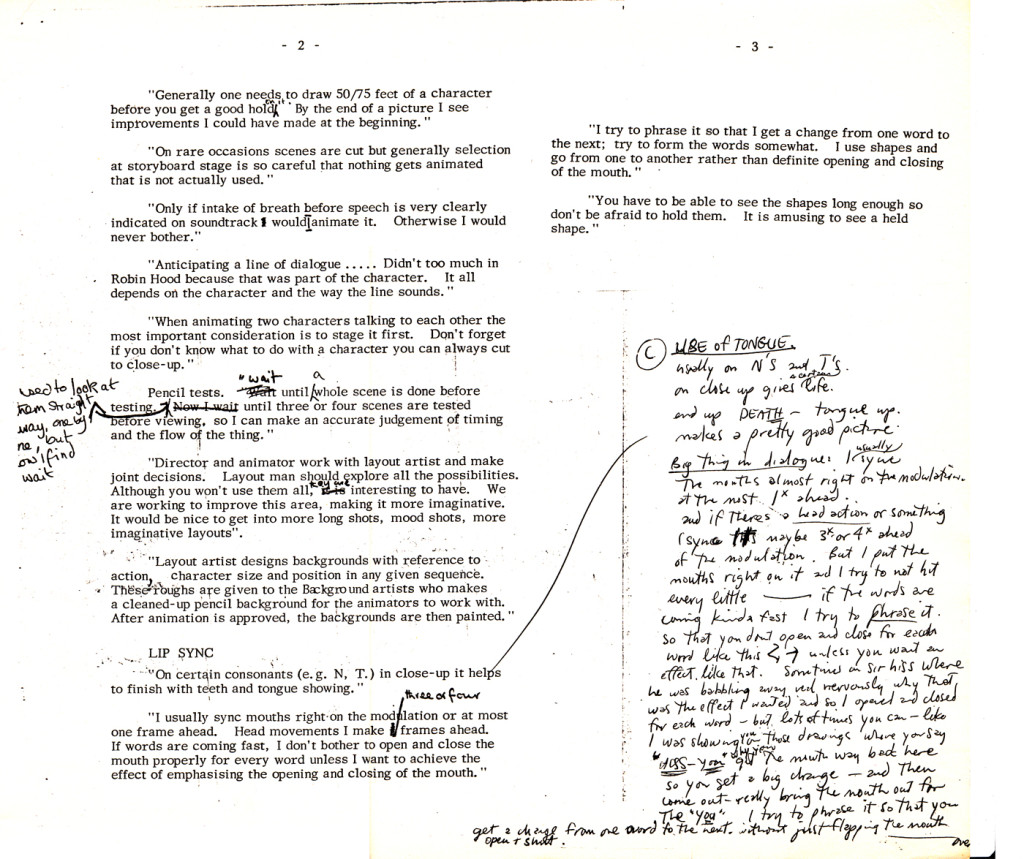

I think these were notes Dick was keeping for a potential book he’d write. They pulled from everywhere, whether it was Preston Blair‘s book or the Disney after-hours studio lecture notes. There were also notes Dick kept from other pros that had given lectures at his studio. Here’s a good sampler of some of these pages. There’s a Milt Kahl talk, a John Hubley talk, notes on an Ollie Johnston talk (typed by Jill, Dick’s assistant as well as notes of different walks from Dick, himself.

I won’t interpret them for you, but will just dump them on you. So here they are. Make sense of them, as you will:

1

1

commercial animation &Frame Grabs &repeated posts &Richard Williams &Title sequences 19 Mar 2013 04:58 am

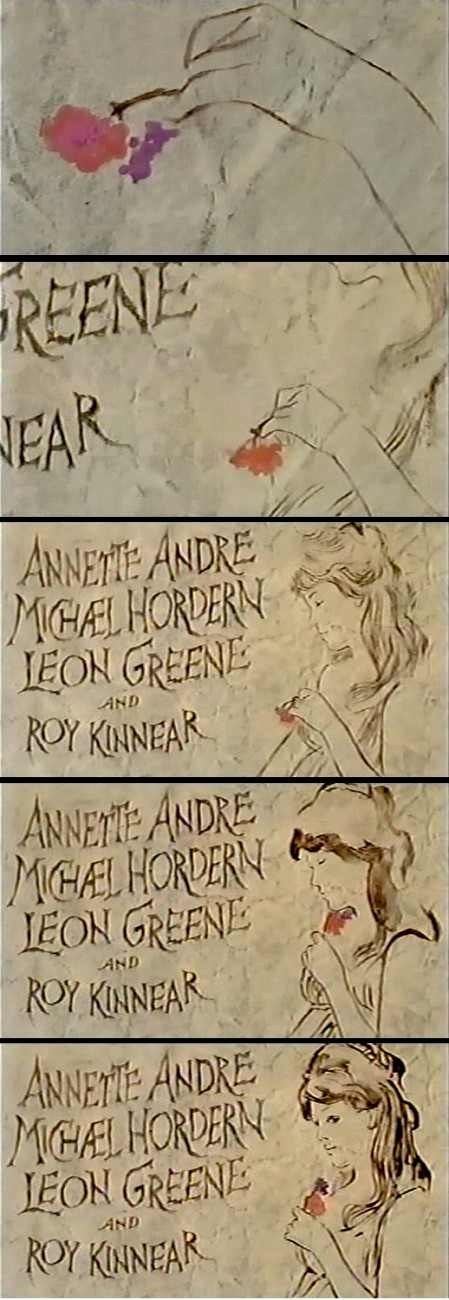

A Funny Thing Happened – again

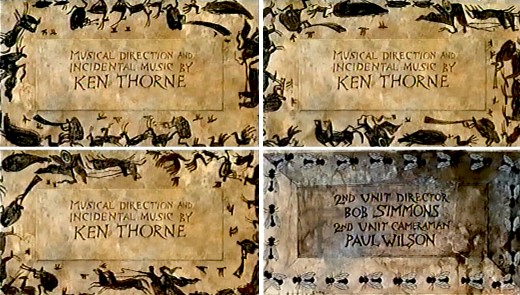

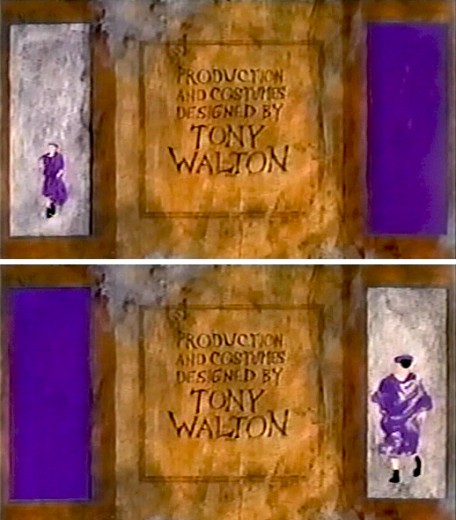

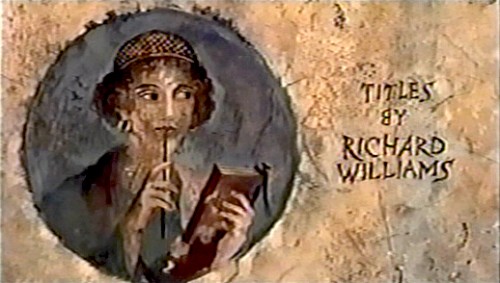

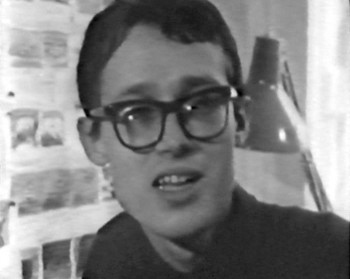

- Today marks the 80th birthday of RIchard Williams. To celebrate, I’ve chosen to post these images from the credit sequence of A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum. My first introduction to Richard Williams and his work came by way of a BBC documentary from 1965, The Creative Person: Richard Williams. It aired on WNDT’s ch 13 in New York (PBS before PBS existed.) Within the sequence there is once scene of a girl smelling a flower. (The Annette Andre credit.) I remember this as part of that doc, and Richard said that at times you should slow down the animation of a character if you want it to seem more real. There’s a dissolve animation going on here.

- Today marks the 80th birthday of RIchard Williams. To celebrate, I’ve chosen to post these images from the credit sequence of A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum. My first introduction to Richard Williams and his work came by way of a BBC documentary from 1965, The Creative Person: Richard Williams. It aired on WNDT’s ch 13 in New York (PBS before PBS existed.) Within the sequence there is once scene of a girl smelling a flower. (The Annette Andre credit.) I remember this as part of that doc, and Richard said that at times you should slow down the animation of a character if you want it to seem more real. There’s a dissolve animation going on here.

This is a great theatrical show and a mediocre movie. Despite the great cast, the brilliant people working behind the scenes (from Tony Walton‘s sets and costumes to Nicholas Roeg‘s extraordinary photography; from the incredible song score by Stephen Sondheim to Ken Thorne‘s excellent incidental music), somehow it all doesn’t really work.

However, animation enthusiasts would be primarily interested in the animated credit sequence by Richard Williams‘ fine animation. This was a sequence that brought Williams out of the cartoon world and into the more serious fold. Suddenly, his studio grew up.

Since we didn’t get to see his brilliant ads in the US, we had to seek out his title work. Credit sequences for future films such as The Charge of the Light Brigade, The Pink Panther sequels and What’s New Pussycat easily demonstrated how he really lifted his studio into the big time.

I’ve made frame grabs of the sequence from my recording, and thought I’d post them for your amusement. Sorry that the copy I have isn’t the most pristine and that the frames available are a bit soft. But I guess the idea comes across.

______________________________________(Images enlarge slightly by clicking them.)

The sequence starts at the end of the film. Buster Keaton runs on a circular treadmill, and dissolves to an animated version of himself.

He grows in the frames as some large-sized flies enter from the left.

Cut out to see a small Buster disappearing. The camera whips across to a picture of fruit. The flies zip over there and eat the picture. (This image of fruit was very dark on screen.)

A fly lands on the nose of a CU caricature of Zero Mostel. His eyes cross watching the fly.

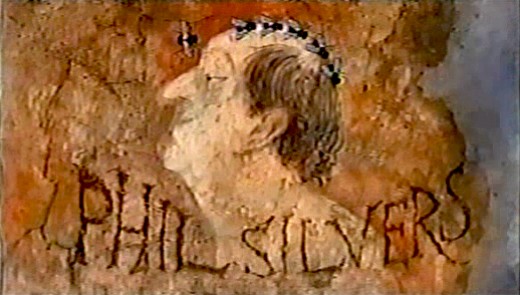

Flies land on Phil Silvers’ bald head and march across.

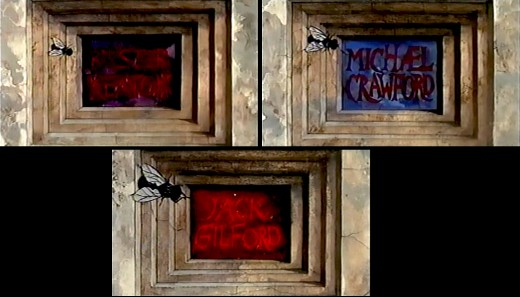

Buster runs across a painted frieze on the way to a series of inlayed boxes.

Zip to the second box credits Michael Crawford. Pan to the third box which features Jack Gilford’s name.

Dick talked with me about this scene in the film. He felt that to create realistic

characters in animation one had to slow everything down. He did it with dissolves.

It’s a technique he came back to often, quite noticeably in The Charge of

the Light Brigade.

Errol LeCain’s art seems to be featured in this elaborate scene. The entire group – top

and (upside down) bottom – dance.

An animated version of Zero Mostel chases a female through and across a painted wall moving into and across the cracks.

The cornucopia of fruit starts in full color but goes to B&W before it’s done, in honor of the great cinematographer.

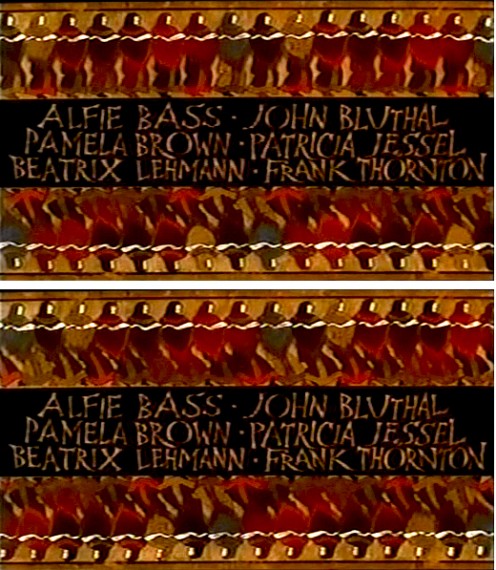

A very large cast of shilhouettes runs around this credit for Ken Thorne. There is no cycle here. This is a Dick Williams piece, so they’re all fresh drawings. They turn into flies for the next credit.

A Roman version of an Escher wall painting animates, confusing the fly trying to walk across.

The animated Buster Keaton runs toward us on one side

and away from us on the other side.

For the editor’s credit, a female looks at herself in a mirror. A hand comes in and clips off her pony-tail.

A slew of credits rots in one spot. This falls off revealing the choreographers’ names.

I’m always fascinated by the credit the designer gives himself. No sign of anyone else

who worked on this sequence. Titles have changed since then.

This is the first time I remember seeing letters from the type of one card falling down to match letters from the next card.

This card, the least significant one, comes back several times.

Of course it’s overanimated though it looks like a cycle.

The camera moves in on a fly crossing a checker board.

Truck out from “End” past “The End” to reveal several more boxes.

Happy Birthday, Richard. Thanks for all the wonderful gifts you gave animation, not the least being the obvious: a new respect for a medium that was dying when you stepped up to the plate. You restored its dignity at least once.

Animation &Commentary &Daily post &Errol Le Cain &Richard Williams 25 Feb 2013 05:28 am

POV

Next Friday, at the invitation of filmmaker-editor-director, Kevin Schreck, I’ll have the pleasure of seeing his recently completed documentary, Persistence of Vision. This is the story of the making of Richard Williams‘ many-years-in-the -making animated feature, The Cobbler and the Thief. I’m not sure of the film maker’s POV, but I somehow expect it to be wholly supportive of the insistent vision of Richard Williams in the making of this Escher-like version of an animated feature. A work of obsession.

It’s the tale of an “artist”, someone who sees himself as an artist, and continually pushes through the world with what would seem to be evident proof of such. After all, this man had single-handedly altered the face of 2D animation in a world that was about to throw it away with all its rich history and artistry and strengths. A medium that had developed through the years of Disney with giant, filmed classics such as Snow White, Pinocchio, Fantasia and even Sleeping Beauty. A medium that had drastically changed to 20th century graphics under the hands of people like John Hubley, Chuck Jones, George Dunning and many others and had just about reached a zenith where it was moving toward something wholly new, something adult.

Instead the medium took a turn in the wrong direction. The economics of television brought us back almost 100 years as films became more and more simplistic and simpleminded in the rush to be cheap. Even the Disney studio went for the poorest subject matter using cost-saving devices to sell their films. Films became shoddier and shoddier, and the economics ruled. The closest the medium would come to art was Ralph Bakshi‘s Fritz the Cat and Heavy Traffic, low budget movies that traded on racy material in exchange for an attempt at something adult, stories barely held together with editing tape. Animation was getting a bad name from every corner whether it was the sped-up graphics of Hanna-Barbera, the reach to the lowest common denominator with poor animation from Disney, or the shock and tell of Ralph Bakshi‘s filmed attempts at what he saw as art.

Williams took a different turn. He went back to the height of animation’s golden era, inviting artists such as Grim Natwick, John Hubley, Ken Harris and Art Babbitt to his London studio to lecture on the rules and backbone of the animation. He brought some of these people to work on a feature that he’d decided to create within his studio on the profits of commercials. These very same commercials financed the training of Dick and his young staff.

A documentary done in 1966, called The Creative Person: Richard Williams offers an excellent view of his studio. We see snippets of shorts Dick made with his own coin: Love Me Love Me Love Me (1962) or The Sailor and the Devil (1967) wherein we see the training of a young and brilliant illustrator named Errol le Cain. (Le Cain became known for his magnificent, glimmering children’s book illustrations. He was doing most of the backgrounds for The Cobbler and the Thief, and had certainly had a large part in its design.)

A documentary done in 1966, called The Creative Person: Richard Williams offers an excellent view of his studio. We see snippets of shorts Dick made with his own coin: Love Me Love Me Love Me (1962) or The Sailor and the Devil (1967) wherein we see the training of a young and brilliant illustrator named Errol le Cain. (Le Cain became known for his magnificent, glimmering children’s book illustrations. He was doing most of the backgrounds for The Cobbler and the Thief, and had certainly had a large part in its design.)

We see in this documentary the first hint of The Cobbler when it was called Nasruddin. It was based on a book of middle eastern tales of a wise fool whose every short story tells a new and positive anecdote. Dick had illustrated several books of these tales with many funny line drawings. The book was written by the Idres Shah who had undertaken a role within the Willams studio finding funds for the feature. Eventually, the two had a falling out, and Idres Shah left with his property. Williams took the work he had done as Nasruddin and reworked it into The Cobbler and the Thief. ________________________________Errol le Cain

We see in this documentary the first hint of The Cobbler when it was called Nasruddin. It was based on a book of middle eastern tales of a wise fool whose every short story tells a new and positive anecdote. Dick had illustrated several books of these tales with many funny line drawings. The book was written by the Idres Shah who had undertaken a role within the Willams studio finding funds for the feature. Eventually, the two had a falling out, and Idres Shah left with his property. Williams took the work he had done as Nasruddin and reworked it into The Cobbler and the Thief. ________________________________Errol le Cain

Meanwhile the work within his studio continued to develop, growing more and more mature. The commercials became the highlight of the world’s animation. Doing many feature film titles such as What’s New Pussycat (1965), A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1966), The Charge of the Light Brigade (1968) led to Dick’s directing a half-hour adaptation of The Christmas Carol (1971). Chuck Jones produced the ABC program, and it led to an Oscar as Best Animated Short.

Through all this The Cobbler and the Thief continued. Many screenplays changed the story and the stunning graphics that were being produced for that film were often shifted about to accommodate the new story.

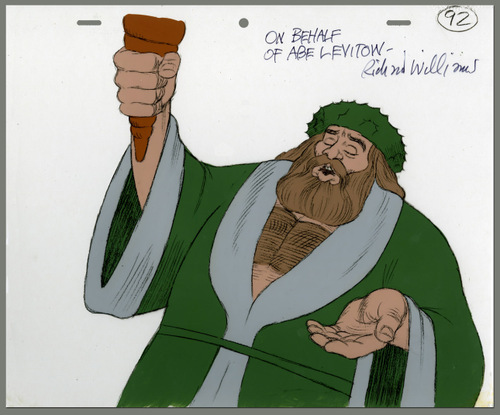

By this time, Williams had developed something of a name within the world of animation. Strong and important animation figures went to his studio to work for periods of time. Someone like Abe Levitow taught and animated for the studio. (His scenes for The Christmas Carol are among the most powerful.) Many of the Brits that worked in the studio and then left to start their own companies were now among the world’s best animators.

By this time, Williams had developed something of a name within the world of animation. Strong and important animation figures went to his studio to work for periods of time. Someone like Abe Levitow taught and animated for the studio. (His scenes for The Christmas Carol are among the most powerful.) Many of the Brits that worked in the studio and then left to start their own companies were now among the world’s best animators.

Williams had the opportunity of doing a theatrical feature adaptation of the children’s books The Adventures of Raggedy Ann and Andy and took it. A large staff of classically trained animation leaders such as Art Babbitt, Grim Natwick, Tissa David, Hal Ambro, Emery Hawkins and many others worked out of New York or LA as the company set up two studios to produce this film. Working for over two years, Dick’s attention was diverted to work away from his London studio, where commercials and some small devotion was given to The Thief by a few of the key personnel working there. Dick spent a good amount of his time in the air flying from NY to LA to NY to London and back again and again. He concentrated his animation efforts on cleaning up animation by some of the masters, rather than allow proper assistants to do these tasks. By doing this he was able to reanimate some of the work he didn’t wholly approve of. Entire song numbers were reworked by Dick as the film flew well behind its budget and schedule.

Eventually, the film finished in confusion and mismanagement, and Dick moved to his LA studio where he continued commercials and began Ziggy’s Gift, a Christmas Special for ABC.

From this he went back to his London studio and did the animation for Who Framed Roger Rabbit for producer/director Robert Zemeckis. He hoped that work on this feature, which won three Academy Awards, including a special one for the animation, would be the triumph he needed to help him raise the funds for The Thief and the Cobbler. Now that he was safely back in his own studio in Soho Square he felt more focused.

From this he went back to his London studio and did the animation for Who Framed Roger Rabbit for producer/director Robert Zemeckis. He hoped that work on this feature, which won three Academy Awards, including a special one for the animation, would be the triumph he needed to help him raise the funds for The Thief and the Cobbler. Now that he was safely back in his own studio in Soho Square he felt more focused.

A contract came from Warner Bros., and the work began in earnest.

Dick’s history wasn’t the best working on these long form films. Chuck Jones replaced him on The Christmas Carol to get it finished when work went overbudget and schedule. Dick was putting too much into it. Gerry Potterton finished Raggedy Ann when the budget went millions over with less than a third completed. Eric Goldberg took over Ziggy’s Gift, the Christmas Special for ABC, to get it done on time. On Roger Rabbit, the live action director stayed intimately involved in the animation after his shoot was complete. When it became obvious that things weren’t going well, he stepped in to complete that film.

In all cases of all of these films, Dick never left. He stayed on working separately on animation or assisting to try to keep a positive hand in the quality of the work that was done.

When The Cobbler and the Thief ran into very serious trouble, there was no secondary Director or Producer to come in and complete the work. Instead that job fell to the money men. The completion bond company, essentially an insurance company for Warner Bros. to make sure they wouldn’t lose their money if things didn’t go well, stepped in. They closed Dick’s studio and removed Dick from the premises. The boxed up and carted off all animation work done or in progress. It was all moved back to Los Angeles.

When The Cobbler and the Thief ran into very serious trouble, there was no secondary Director or Producer to come in and complete the work. Instead that job fell to the money men. The completion bond company, essentially an insurance company for Warner Bros. to make sure they wouldn’t lose their money if things didn’t go well, stepped in. They closed Dick’s studio and removed Dick from the premises. The boxed up and carted off all animation work done or in progress. It was all moved back to Los Angeles.

The Weinsteins, through their company, Miramax bought the film at auction and completed it with a poor excuse of an animation outfit they set up in LA. Work was also sent to Taiwan. The script was reworked trying to capitalize on the success of Disney’s Aladdin that had recently opened in the US. If Robin Williams‘ ad libbing could be such a success, imagine how well Jonathan Winters could do repeating that for a character who, in Dick’s original version, had no voice. Now he didn’t stop talking.

The new film failed miserably and deserved to do so. The primary audience, I would suspect, was the entire world animation community coming to look down on the artificially breathing corpse.

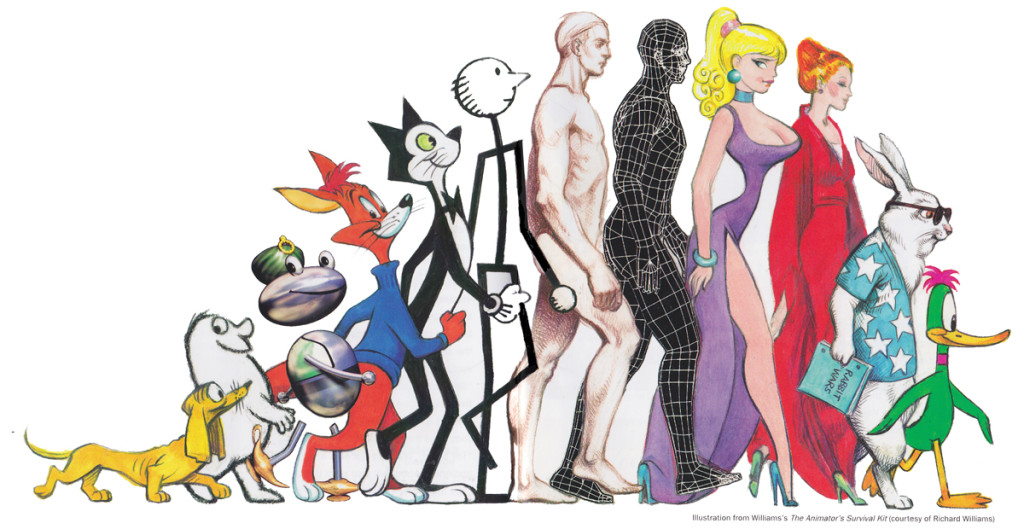

Richard Williams, himself, retired and moved far from the mainstream. He continues to work on small animation bits, but his primary work has been in making a series of DVD lectures revealing how animation should be done. This accompanies a well-received book he wrote and illustrated. Meanwhile, the animation community still hopes that something will emerge from that corner.

Richard Williams, himself, retired and moved far from the mainstream. He continues to work on small animation bits, but his primary work has been in making a series of DVD lectures revealing how animation should be done. This accompanies a well-received book he wrote and illustrated. Meanwhile, the animation community still hopes that something will emerge from that corner.

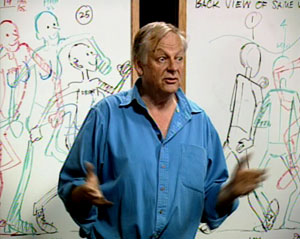

Dick turns 80 years old on March 19th. He’s still an amazing forceful and exciting personality. I wish I had more access to him (as does most of those who knew him back then.) He’s had probably the greatest effect on the animation industry of anyone since the late sixties. There are still studios thriving today on information they learned from Dick and his teaching.

If you’re unfamiliar with the blog, The Thief, I suggest you take a look.

Animation &Animation Artifacts &Richard Williams 08 Oct 2012 07:24 am

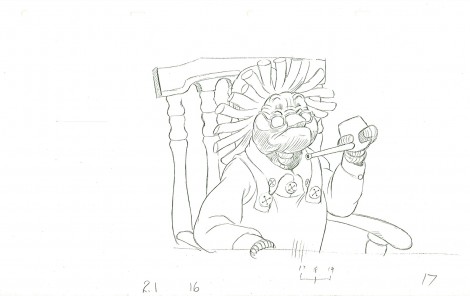

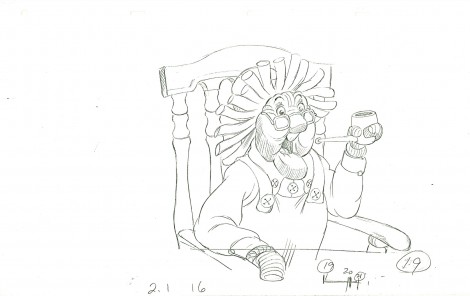

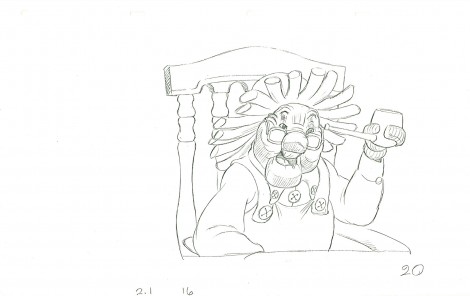

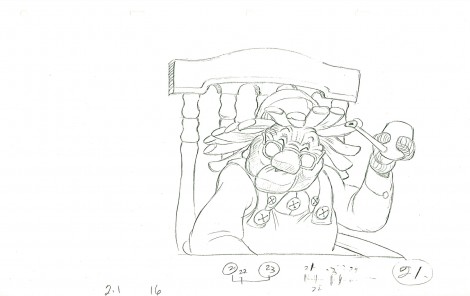

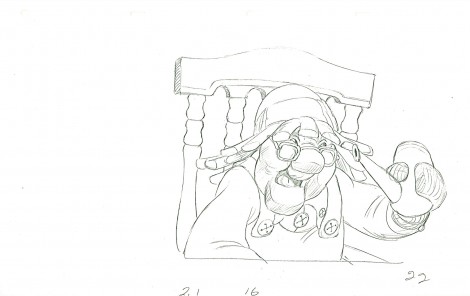

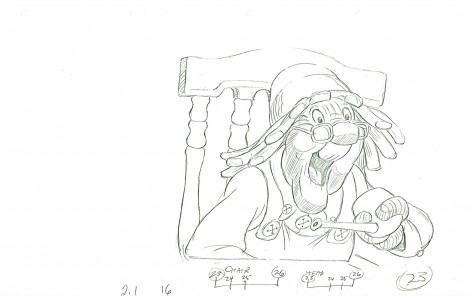

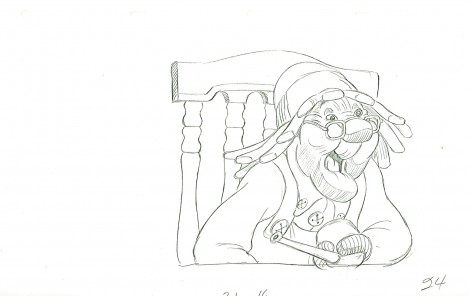

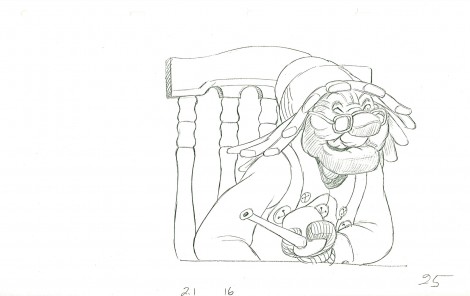

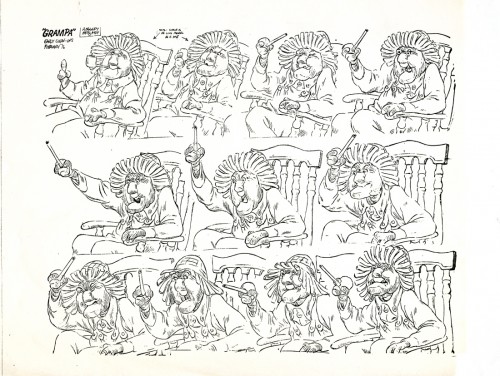

Gramps – anew

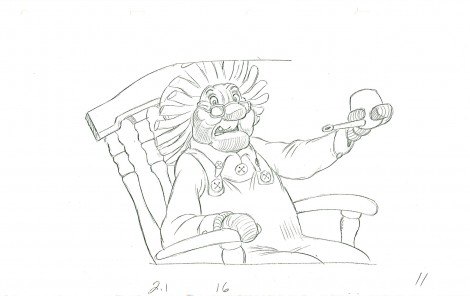

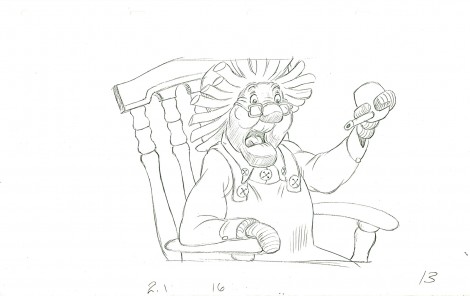

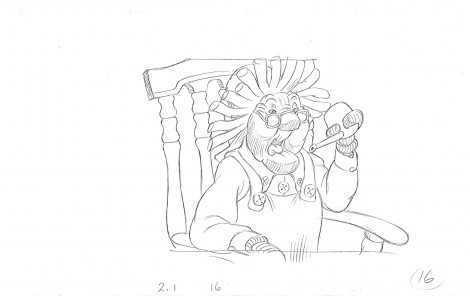

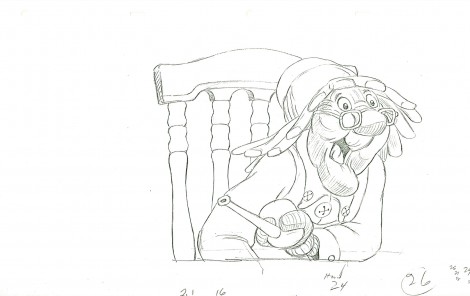

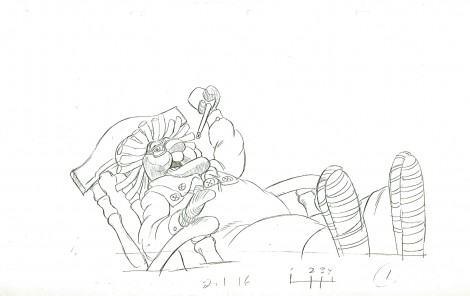

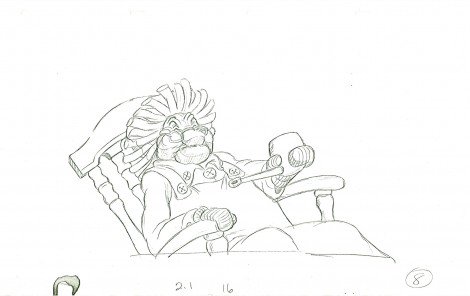

- I have the CU drawings done by Richard Williams for a small scene from Raggedy Ann & Andy. I had thought the original animation was done by Spencer Peel, though I’m not sure. The drafts seem to credit Gerry Chiniquy.

For the first half of the film, Dick spent much of the film holed up while assisting and inbetweening many of the animators at the film’s start. In doing this, he was also able to rework and retime the animation and, thus, have control over it all. Once Dick became involved in a scene, it’s hard to say who animated it.

The problem was that the director has bigger things to do that affect the big picture.

This scene, beautifully cleaned up, is typical of these playroom scenes. And yet, as far as I can tell this was eliminated from the final film. I don’t have time to check the actual film, but the drafts indicate that scene 2.1 / 16 was taken out of the movie. I’ll look at the film just to make sure, but it looks pretty certain to me.

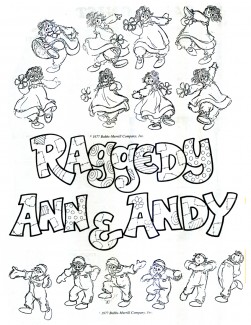

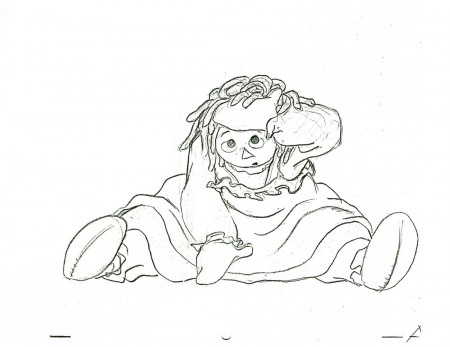

This is a model sheet taken from a similar scene in Raggedy Ann.

It’s obvious that his POV has shifted from left to right, and that may be

the reason for eliminating the scene pictured below.

The scene started out with 32 drawings, but it seems that Dick eliminated three of them (27-29) to hit an accent a bit harder than was done in the original animation.

1

1

3

3

Dick had a unique animation and cleanup style. He would draw

his drawings incredibly light going quickly through the entire scene.

4

4

The pencil line of that first round was almost invisible.

5

5

Then he’d go back and work over those lines

just as lightly and just as quickly.

6

6

then he’d do it again, and again, and again.

7

7

This gave him the opportunity of changing and adjusting as he went along.

8

8

It also is a method somewhat similar to the one

that Tytla and Ferguson used in the 1930s. They’d

go for the “forces” and then go back and build up from there.

9

9

Williams used his light pencil lines to build up around his forces.

10

10

Oddly the animation style is unlike Tytla and Ferguson and

more like the tight constructed, planned style of Babbitt.

________________________

Here’s a QT of the cycle with a mix of one’s and two’s.

Articles on Animation &Richard Williams &Tissa David 01 Oct 2012 06:37 am

Raggedy Ann and Andy

- On Tuesday, October 23rd a memorial service for Tissa David will be held at the Lighthouse Academy Theater at 111 East 59th Street. It will begin punctually at 7pm. Seats will be available on a first-come first-served basis. To continue celebration of Tissa’s work, here’s an article that appeared in Cartoonist Profiles Magazine, No.33, March 1977. No writer’s name is credited.

We thank Mike Hutner. of Twentieth Century-Fox, for the production notes about this new full-length animated film, RAGGEDY ANN & ANDY, which is having its world-premiere in New York on March 20th.

Raggedy Ann is a caricature of a rag doll, with stringy red hair, button eyes and a painted triangular nose.

Raggedy Ann is a caricature of a rag doll, with stringy red hair, button eyes and a painted triangular nose.

Harold Geneen is the Chairman of the Board of the ITT Corporation, an industrial empire which includes hotel chains, construction companies, the Bobbs-Mcrrill book publishing house and a car rental lirm which tries harder.

It was hardly destined that they would be linked in one of the year’s most ambitious entertainment ventures. But the proof is on 35mm Panavision film, in the form of “Raggedy Ann and Andy,” the feature-length animated musical from 20th Century Fox.

The genesis of the full-length am mated musical—one of the few such projects attempted during the past few decades without the Disney insignia—is a story which has its own touches of fantasy. In addition to ITT’s Board Chairman, the principals include:

• A team of Broadway theatre-owners and producers, who never before made a movie, lei alone an animated feature.

• An Emmy-winning composer, one of whose songs was a hit for both “Kermit the Frog” and Frank Sinatra.

• An Academy Award winning director who thought he was out of the picture until he look part in an all-night jam session at his Soho studio.

• Several legendary cartoonists, including the originator of “Betty Boop” and the man who gave Disney—and the rest of America—the beloved “Goofy.”

How they came to join forces really begins in Silvermine, Conn, in the early 1900′s. when newspaper cartoonist John Gruelle took a few minutes away from his drawing board to help his daughter fix a discarded rag doll. The toy was named “Raggedy Ann” by combining characters from two poems by James Whitcomb Riley — The Rag Man and Orphan Annie.

When Marcella Gruelle became desperately ill, her father sat by her bedside, making up stories about the doll’s adventures after everyone in the house was asleep. Marcella died on March 21st, 1916. after which her father determined to share with the world the stories he had not had time to tell her.

By the early 1970′s. Raggedy Ann was part of American folklore, a character whose exploits had sold some 80 million books and hundreds of millions of toys and games. That was when Lester Osterman. a former stockbroker who brought Sammy Davis Jr. to Broadway in “Mr. Wonderful.” and Richard Horner an ex-actor who had appeared in the Oberammergau “Passion Play” became involved. The producers of such Broadway successes as “Butley” and “Hadrian the Seventh,” they had just completed a live-action television special for the Hallmark Hall of Fame, based on the children’s classic. “The Littlest Angel.” Now they were searching for a similar property . . . for the same showcase.

A casual lunch with a merchandiser of children’s toys proved crucial. “Would you believe that after all these years. ‘Raggedy Ann’ is -.till one of the biggest sellers?” inquired the friend rhetorically. Within a few days. Osterman and Horner were on the doorstep of the Bobbs-Merrill Company, which publishes the “Raggedy Ann” stories, requesting development rights to the character.

An equally informal meeting with Joe Raposo. Emmy-winning composer-conductor of “Sesame Street,” brought music to the project. Horner and Osterman found themselves seated with Raposo at a Friars’ Roast for Johnny Carson. Somewhere between the broiled chicken and dessert, Raposo agreed lo score the “Raggedy Ann” tales.

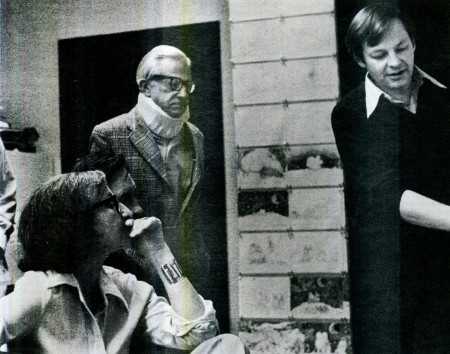

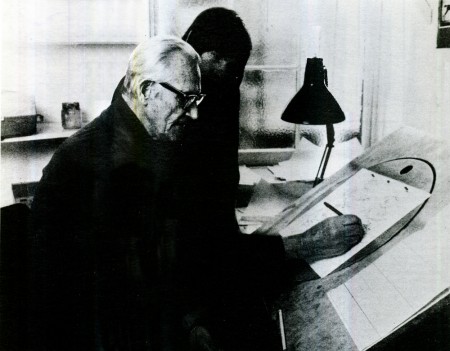

Animators Tissa David and Art Babbitt with director Dick Williams.

Next to join the troupe were writers Max Wilk and Pat Thackeray. True to Gruelle’s imagination, they created a fantasy world in which toys spring joyously to life. When Raggedy Ann discovers that the pixieish French doll, Babette, has been kidnapped by a pirate known as Captain Contagious, they set out to free her. That takes them into the “deep dark woods”, inhabited by such personalities as the “Looney King,” “the camel with the wrinkled knees” (one of Gruelle’s personal favorites) and the “Greedy,” a kind of confectionery version of the La Brea Tarpits. “We thought we were writing a live television special,” recalls Ms. Thackeray. “So much so that we began casting Raggedy Ann in our minds, alternating between personalities like Liza Minnelli and Goldie Hawn.”

But Raposo was having second thoughts. “It won’t work,” he finally admiitted. “Put a red fright wig and a painted mouth on an actress— any actress—and do you know what you’ll have? A circus clown.”

The obvious alternative was a full-length animated musical cartoon. Which is like saying the obvious alternative to your reliable family car is to go out and buy a Rolls Royce. There is a reason, as director Richard Williams would later point out, why animated features are almost exclusively the province of the Disney organization. “And even Disney turns out several live comedies and nature films for every animated movie.” Williams notes.

To create 90 minutes or more of full animation (as opposed to the jittery short-cuts of television cartooning) requires more than one million preliminary and final drawings. From inception to “answer print” lakes three years or more. “And the cost,” adds Williams, “is tremendous.”

“Since the Hallmark people had discussed a live musical, they were perfectly justified in walking away from a more costly animated feature,” says Horner. The producers now had a cartoon without a cartoonist, a television special without a sponsor, and a project without investors. But it was no time to think small. Why settle for a television special? Why not make “Raggedy Ann and Andy” as a movie?

It was back to Bobbs-Merrill with the suggestion that Osierman-Horner and the publishing house become partners in the proposed film. That, the publishing executives said, was up to their parent company, ITT. A meeting was arranged with Board Chairman Geneen. which developed into a corporate backers audition.

Pat Thackeray later described the “incredible afternoon” to author and critic John Canemaker, whose book, “The Animated ‘Raggedy Ann and Andy’-The Story Behind Ihe Movie,” will be published at the same time as the 20th Century Fox release.

“Geneen came into the room, asking questions, his mind like a laser,” she said. “He remembered a stage version of ‘Raggedy Ann’ he’d enjoyed as a youngster, in the I920′s. We made our presentation. Then, as we were going down in the elevator, a guard told me, ‘I don’t know who you are but you’ve got it made.’

“I asked why.

“The guard said, ‘Because the old man stuck his head out of the door and asked what I thought of the music coming from his office. I said it sounded pretty good to me. That wasn’t just good, Harry,’ he said, ‘that was terrific.’”

With financial backing assured, the next problem was simple. Who would draw the million-plus pictures which would make up the finished movie? And who would piece them all together with wit and style?

Firsl choice was Richard Williams, the Canadian-born, London based head of his own animation studio who had won an Academy Award for “A Christmas Carol” and a host of admirers for the “Return of the Pink Panther.” Despite a commitment to his own project, “The Thief and the Cobbler” Williams listened to Raposo’s score, and said yes.

“But my business manager said ‘no,’” Williams recalled. “Or to put it more accurately. he priced my services so high, there was no way the picture could have come in on budget.” What happened to the business manager? “He’s not with me anymore,” Williams replied with British sang-froid.

Tissa David’s rag doll

Osterman and Horner began negotiations with a New York cartoon “factory” which specialized in limited animation for television. Within a short period (according to Canemaker), the newcomers had virtually thrown away the Wilk-Thackeray script, replacing Gruelle’s characters with a “Love Fairy” and a “Cookie Giant.” Outraged. Raposo walked out of a story conference (“before 1 threw up from all that treacle,” he recalls) and caught a plane to London to make a last-ditch attempt at hiring Williams.

Discovering a shared taste in jazz, the two men opened a bottle of Scotch and during an impromptu jam session, past misunderstandings vanished in a vapor of 12-year-old malt and good will. The animated movie finally had an animator.

It was Williams who formulated the approach to the picture. “Disney’s contribution to animation is colossal,” he said. “The technique of bringing a cartoon character to life would slill be in the dark ages without Disnev. But to copy the ‘look’ of his films would have been disastrous.

“Instead, 1 said, ‘let’s be as rich and lush as Disney in a totally different style … in the style of Johnny Gruelle.’”

A remarkable team of animators was assembled in New York and Hollywood lo carry out that mission. Included were several men and women who can legitimately be termed ‘living legends’ in the field of motion picture cartooning.

There was Grim Natwick, a spry octogenarian, who had designed the first of the “Betty Boop” pictures for producer Max Fleischer in the thirties and animated the majority of Snow White’s scenes for Disney. Another Disney veteran was Art Babbitt, the co-creator of “Goofy” and the dancing mushrooms in “Fantasia,” whose verbal donnybrooks with Disney during the I940′s had been peppery Hollywood gossip.

85 year old animator Grim Natwick

with young animator Crystal Russell

To draw the “Greedy,” a ‘monster’ made of whipped cream, cherry banana taffy, chocolate fudge and other sugary delights. Emory Hawkins—a veteran of Disney as well as the MOM and Warner Brothers cartoon studios -was summoned from his New Mexico ranch. “Raggedy Ann” herself was drawn by Tissa David, a Transylvanian-born artist who had worked with Natwick at UPA Productions during the heyday of “Mr. Magoo” and “Gerald McBoing Boing.”

From Canada came Gerald Potterton, head of his own animation studio. whose credits include the Peabody Award winning “Pinter People” and key sequences in the Beatles’ “Yellow Submarine.” The design of the vital storyboards and layouts which gave the picture its graphics stamp was up to Cornelius “Corny” Cole, both an animator and a renowned painter.

The musical routines for the “Twin Penny Dolls,” whose movements are perfectly synchronized with each other, were drawn by Gerry Chiniquy. who looks like Gene Kelly and specializes in “dance animation.” During a ten year period at the Warner Brothers Studios, whenever Bugs Bunny or Daffy Duck were called on to trip the light fantastic, Chiniquy got the nod.

Soon, the sketches began mounting—at the unit’s bustling New York headquarters (which are wag dubbed “Raggedy Ann East”), a California studio and director Williams’ home base in London. Williams’ job was clearly defined.

“I was in charge of catching airplanes,” he laughed. Spending ten days to two weeks in each city, Williams would check the work of dozens of illustrators, pencil in his own suggestions, hold story conferences, review preliminary sound-track recordings, analyze the “Leica Reel” (a rough compilation of the motion picture in progress, pieced together as new drawings and backgrounds were added “like a jigsaw puzzle”), then rush to the airport.

“I became one of the world’s great authorities on jet lag,” he added.

Choosing the voices of Captain Contagious, Suzy Pincushion, the zany “Gazooks” and other denizens of Raggedy Ann’s fantasy world became a crucial problem. Tradition says the voices for a feature-length cartoon should be box-office names whose unseen presence will enhance the picture’s publicity and promotion. Raposo and Williams chose to defy tradition, backed by co-producer Horner. “We were treating the picture as a big, lavish Broadway musical—in the form of an animated cartoon—so we looked to Broadwav for vocally gifted actors,” said Raposo. Casting sessions were held in a New York studio, where hundreds of performers went through their paces.

“I knew the long hours were getting to me when 1 walked through the hall, outside the studio, and saw a man reading our script, who really looked like a camel,” said Williams. Ironically, the actor was dour-faced Fred Stuthman, who eventually did provide the voice for the “Camel With the Wrinkled Knees.”

Another actor’s reaction set the whimsical tone of the casting sessions.

“You want me to play what?” said Joe Silver, veteran of such movies as “The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz”, in utter disbelief.

“An enormous pit of taffy, filled with gum-drops and maraschino cherries and covered with chocolate sauce,” answered casting director Howard Feuer.

“Is this a gag?” asked Silver. He was quickly persuaded it was not and even more quicklv rose to the chocolate covered challenge.

Emory Hawkins Taffy Pit

Virtually all of the “Raggedy Ann and Andy” voices are better known to their peers than to the general public. Included are Didi Conn of the television series, “The Practice.” whose voice has been likened to that of a “sexy frog” as Raggedy Ann: Mark Baker, co-star of Leonard Bernstein’s “Candide” as Andy: Allan Sues from “Laugh-In.” Arnold Stang, Mason Adams and George S. Irving. The “sockworm” is vocally portrayed by a man with more impressive credentials in another phase of show business—Sheldon Harnick, lyricist of “Fiddler on the Roof.”

Only one performer is seen on film, during an introductory sequence about Marcella Gruelle. Casting the role, director Williams, recalls, was a thorny problem. “I needed a little girl on whom 1 could impose a 12 hour work day, to stay within schedule.” Rather than face some other lot’s outraged parents, he elected his own six-year-old daughter, Claire. “My presence made it a kind of game for her.” he adds.

Meanwhile, the pressure at Raggedy Ann East. Raggedy Ann West and the London base was mounting. Williams and his associates had promised a finished movie to Bobbs-Merrill in time for the film to be launched nationally by Easter, 1977. The million-plus drawings had been completed, and now the inkers, opaquers, “in betweeners,” and other technical craftsmen, vital to an animated movie, were working double and triple shifts, to meet the deadline.

The only rule, Williams paradoxically demanded as he fired memos to the tripartite staff (“usually dictated somewhere over Kansas,”) was that there must be no compromise in quality. Typical of the fine detail necessary to achieve “full animation” was an incident which occurred in the office of veteran supervisor Marlene Robinson. An “inbetweener”-responsible for linking the animators’ drawings, frame by frame—was frustrated. Several strands of Raggedy Ann’s hair refused to move in rhythm with the rest of the character.

The next hour was devoted to re-drawing the wisps of hair, over and over, until there was perfect synchronization.

“It seems like such a little thing,” Ms. Robinson said afterward. “But blown up to Panavision size, anything which distracts the eye of the moviegoer—shapes that vary, colors that fade, even a recalcitrant strand of hair, is enough to destroy the ‘illusion.’”

Babbitt’s “Camel with the wrinkled knees”

In another room, Cosmo Pepe, working with complex equipment designed by cameraman Al Rezek, was transferring the drawings onto sheets of transparent celluloid—by shooting 13.000 volts of electricity through them-prior to putting them through a Xerox enlarger. “We developed a special toner, for the enlargements, to Dick Williams’ specifications,” Pepe revealed. “The toning is vitally important: it affects the way the characters stand out on the big screen. The formula for this toner is as closely guarded as a three star chefs award winning recipe.”

By the lime “Raggedy Ann and Andy” was completed, and ready for release by 20lh Century Fox more than five years had passed from the date on which Osterman and Horner first solicited the rights from Bobbs-Merrill. More than two years had been spent in production.

Richard Williams summed up the feelings of everyone involved by quoting Johnny Gruelle. “It does pay to do more work than you are paid for, after all,” Gruelle once told an interviewer. “Someone, somewhere, sometime will see it and appreciate it.”