Monthly ArchiveFebruary 2015

Daily post 13 Feb 2015 03:02 pm

ASIFA EAST Memorial for Michael Sporn March 2, 2015

Michael Sporn was one of the giants of the New York animation community. From 1980 until his untimely death last year, Michael Sporn’s studio produced many acclaimed television specials, most of them animated entirely here in New York.

To commemorate the first anniversary of his passing, ASIFA-EAST is hosting an evening of Tribute to Michael Sporn–and we’re encouraging members of the animation community to contribute to a tribute reel to be presented at the event and preserved online.

ASIFA-East Tribute to Michael Sporn

Monday, March 2, 2015

6:30 pm – 9:00 pm (doors open at 6:00 pm)

SVA Theatre [Beatrice]

333 West 23rd Street (between 8th & 9th Ave.)

New York, NY

(no RSVP required)

For the tribute reel we are inviting anyone to participate and send their personal message about Michael, his work, what he means to you, his animation, whatever you feel moved to say. You can write, draw, paint, photograph, GIF, audio record or videotape your message. Please email your tribute to asifaeasttreasurer@gmail.com by next Friday, February 20.

Please join the others who knew him, worked with him, and read “Splogâ€â€“his celebrated blog to look back at his foot prints and keep his legacy alive for the future.

Daily post 07 Feb 2015 05:00 pm

Animation Day of Rememberance for Michael Sporn

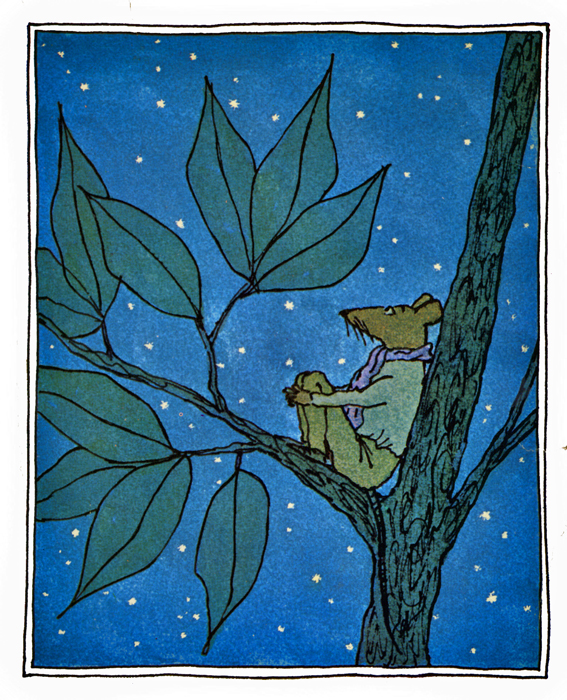

Today in Hollywood, Tom Sito and Yvette Kaplan will represent Michael at the Animation Day of Remembrance. Tom and Michael go all the way back to 1976 and Raggedy Ann. Yvette met Michael at The Hubley Studio here in NYC. I have requested that they include Ray Kosarin’s superlative memorial to Michael and his studio. It was written by Ray for Michael’s Memorial Celebration at the AMPAS Lighthouse screening room on March 31, 2014. Tom asked me if he could use the Michael’s rendering of the mouse, Abel, talking to The Star from Abel’s Island by William Steig for the program cover. I said, “Absolutely!” Both Tom and Yvette will be speaking. Michael would have been very pleased to be represented by such artists and friends. Tom will be sending some pics of the event that I will post later.

The image of Michael animating is by the great Tissa David. This image is one panel from a storyboard birthday card she drew for him in 1999 celebrating how they met at the Hubley Studio in 1972.

Ray’s memorial and Michael’s rendering of Abel are posted below. If you look closely at Abel’s eyes, you will see Michael.

Heidi

31 March 2014

Ray Kosarin

MICHAEL SPORN MEMORIAL

What Animation Should Be:

On Working with Michael

Michael was an extraordinary artist and his studio was an extraordinary place. And the two or three generations of animation artists, like me, who worked with Michael remain to this day something of an extended family. A great many of us admired Michael, learned from him and were, often importantly, influenced by him. This influence, along with Michael’s remarkable body of work, is a vital part of his legacy.

What makes Michael’s films as distinctive—and as good—as they are comes from who he was: from what mattered to Michael, in art of any kind, and his convictions about what animation was. His studio was something like a repertory company of artists he trusted, and from whom he coaxed the work he wanted. And the way did was rare and exciting.

When you worked for Michael, he invested you in what mattered to him. He shared films and art of all kinds he thought were good; he made clear (at times brutally) what he did not; and he demonstrated by his own example, continually infusing you with his ethos of what animation should be. Figuring out what to do about it was your problem. And you felt determined to get it right.

In this way, Michael’s direction was both firm and, thrillingly, open-minded. He’d hand out full sequences, casting animators according to their sensibilities, and if you wanted to do a particular sequence, he almost always made sure you got it, trusting there was probably a good reason it spoke to you. He seldom gave too-specific directions, preferring to watch where your instincts carried the scene.

This made for a studio atmosphere of personal responsibility and shared purpose. Your work had better be good, but not conspicuous about it. When busy on a production, Michael moved swiftly and spoke little, which sharpened you to the small but critical signals whether you were giving him what he wanted. When OK’ing a line test of a scene you’d just animated, he might enigmatically say, “It moves,†then get on with something else. But when you gave him something he really liked, he’d usually just say, “Great.†At least you were pretty sure that’s what he said. But he said it quickly, while already striding away toward his desk: there was other work to do. When the studio was humming, it felt like a large family, all cooking dinner.

Without a doubt, the quality Michael most prized, both in the work he admired and the work he made, was economy.

Michael is somewhat legendary for the small budgets with which he made most of his films. As his good friend, animation historian Michael Barrier—who’s with us tonight—wrote: “Michael’s genius, and his curse, was that he could do so much with such tiny budgets. I will never cease to wonder what he might have accomplished with the money that always seems to be available to people with only a fraction of his talent and none of his integrity.â€

Yet it would also be a mistake to think that the economy in Michael’s films was strictly about money. In fact, something much more important was going on—something about artistic morality.

Always Michael was drawn to artists who did powerful work with conspicuously minimalist means: painters like Paul Klee, composers like John Adams. Michael often played in the studio minimalist music by Adams, or Philip Glass—music balanced so precisely that, after many bars reiterating the same arpeggio, one note’s climbing a semitone became an epic event. Minimalism was no apology for limited means: it was an expression of artistic purity—a virtuosic display of an artist in peak control of his powers.

So Michael drove you to do much with little. He goaded you by example, dropping valuable hints through his running commentary on his own work. He might, after pencil-testing a scene, triumphantly shout, “Ten drawings!†and then do his pirate laugh.

But through it all was an unmistakable higher purpose. The leaner your animation got, the more focused—a quest for the sweet spot where the interval between one drawing and the next, as with the minimalist composers, became the richest possible event. You were not cheating the audience out of drawings: you were showing them the respect not to squander on them drawings that only smoothed, but did not tell.

It worked wonders. It forced you to work smarter. And, low budgets or not, the films stubbornly won Emmys, ACE Awards, festival prizes, endless critical praise.

All of us who were lucky to work with Michael have of course had our own experiences. And yet our shared experience working with him, as we always remember when our paths cross today, importantly shaped and strengthened us all—as artists and individuals. The vocabulary Michael shared with us for how to know and make good work, to this day, coaxes us to do better, even on projects Michael might not have deemed worthy. Michael’s habit of dogged perseverance reminds us of our own reserve. And stubbornly alive in all of us are Michael’s sharp eye and infallible taste. This is Michael’s living—and loyal— legacy.

Who could wish one any better?

Ray Kosarin