Search ResultsFor "two guys named joe"

Commentary 16 Mar 2010 07:52 am

Haiti and other stuff

- I received the following film in an email from Karl Cohen in San Francisco. Karl writes: “Alan Sperling is a former employee of Richard Williams when he had a studio in LA and has worked in SF for many years.”

In fact Alan also animated on Cool World, Toy Story, and Monsters Inc.

He did the following film, Scratch, for the Haitian relief effort and he’s just trying to get it seen by as many people as possible. So take a look, if you haven’t seen it as yet.

- Recent posts about the internet toast the 50th birthday of the late Joe Ranft.

- Recent posts about the internet toast the 50th birthday of the late Joe Ranft.

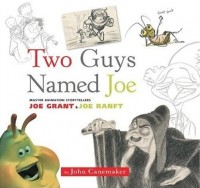

I think the most fitting tribute for this man will come later this year when John Canemaker‘s beautifully written and sensitive book, Two Guys Named Joe arrives in book stores. The stories of Joe Ranft and Joe Grant are detailed, elaborated and interrelated without an iota of sentimentality. This is a gorgeous and strong book and a magnificent tribute to both Ranft and Grant. It’s one of the best books in John’s canon. Look for it in August.

Speaking of Joe Ranft, I saw a screening at MOMA last night of Waking Sleeping Beauty, a must for any animation enthusiast. It’s a fast paced intriguing story when all layed out. I’ll review the film later this week. I just wanted to mention that Joe Ranft was featured prominently (though never identified) throughout the film. He, obviously, was a big part of that period.

Speaking of Joe Ranft, I saw a screening at MOMA last night of Waking Sleeping Beauty, a must for any animation enthusiast. It’s a fast paced intriguing story when all layed out. I’ll review the film later this week. I just wanted to mention that Joe Ranft was featured prominently (though never identified) throughout the film. He, obviously, was a big part of that period.

I also got to meet Tomm Moore, who sat in front of me, at the screening. I’m pleased to finally be able to put a face to The Secret of the Kells. I’ve seen the film twice and have a lot of respect for the enormous production he was able to pull off so successfully. It’s so hopeful for all of us independents to see the little guy with so tiny a distributor making such large waves.

- Other sites talk about the press release this past week of Disney’s closing Imagemovers Digital, the company Robert Zemeckis used to make his last couple of MoCap features. This was hardly great news given the costs that those films absorbed. When the Jim Carrey Christmas Carol costs $174 million, it’s unlikely to return its investment. Ultimately, it will probably break even, but one wonders if the same financial “success” wouldn’t have been achieved using traditional animation. When Bolt costs $150 million and returns $114 from US receipts, it’s averaging about the same as the $50 million loss Christmas Carol currently shows. Beowulf had a $150 million budget and brought in $82 million.

It seems clear to me that the writing was on the wall. The wonder is that Disney still has the deal to release The Yellow Submarine. Undoubtedly that film will ignore the great graphics of the original to bring us a MoCap version of the four Beatles – in that wonderful Zemeckis “walking-dead” style. How much can that lose – and cost?

It seems clear to me that the writing was on the wall. The wonder is that Disney still has the deal to release The Yellow Submarine. Undoubtedly that film will ignore the great graphics of the original to bring us a MoCap version of the four Beatles – in that wonderful Zemeckis “walking-dead” style. How much can that lose – and cost?

Remember, a bad movie is a bad movie, whether it’s traditionally animated like Treasure Planet or cgi like Space Chimps or MoCap like Beowulf. Disney’s not moving away from financing bad movies, they’re cutting costs on financial risks.

- For those of you not living in New York, this is the kind of outdoor advertising Adult Swim uses to promote its wares.

.

.

Almost as good as the shows themselves. 25% P’Toots.

________________

- Finally, I wanted to revisit something Amid Amidi posted on Cartoon Brew over the weekend. Brian Duffy wrote to me to introduce me to a couple of sites. As an enormous fan of optical toys, with a mini collection of non-authentic pieces of my own, I rushed to look at the wares on the site, the Richard Balzer collection. There, I loiotered for hours and have returned many times since first viewing them. Everyting from Praxinoscopes to Thaumatropes to Zoetropes are displayed in a stunning collection of artifacts in this wealthy collection. They also have a blog, dickbalzer.blogspot.com, which is demonstrating via flash videos how the pieces operate. I look forward to viewing some of the zoetrope animations and will continue to return for updated pieces. I love this stuff.

- Finally, I wanted to revisit something Amid Amidi posted on Cartoon Brew over the weekend. Brian Duffy wrote to me to introduce me to a couple of sites. As an enormous fan of optical toys, with a mini collection of non-authentic pieces of my own, I rushed to look at the wares on the site, the Richard Balzer collection. There, I loiotered for hours and have returned many times since first viewing them. Everyting from Praxinoscopes to Thaumatropes to Zoetropes are displayed in a stunning collection of artifacts in this wealthy collection. They also have a blog, dickbalzer.blogspot.com, which is demonstrating via flash videos how the pieces operate. I look forward to viewing some of the zoetrope animations and will continue to return for updated pieces. I love this stuff.

By the way, the toy zoetrope to the right is one I own, a giveaway from Wendy’s back in the ’90s.

Articles on Animation &Independent Animation 21 Jan 2010 08:29 am

Len Lye

- Len Lye, one of the original experimental animators, has rarely gotten the acclaim from the animation community that he has certainly deserved. Rarely is his name mentioned in animation books or articles. As a matter of fact, in more than 50 years of reading about animation, I can only remember two significant magazine articles about the man and his work that appeared in animation magazines. (If you really go looking you’ll find a lot written in art publications – not animation mags.)

Here, I’m posting one fof those two that I think is a significant and clear article, and I hope it will give the man another five minutes of your attention. The article was written by Joseph Kennedy for the February 1977 issue of Millimeter Magazine.

by Joseph Kennedy

Len Lye‘s Greenwich Village loft is an airy workshop, filled with the tools of the artist’s trade: machine saws, diagrams, models of projected works, and several silvery kinetic pieces glistening in the summer afternoon’s light. Len Lye himself is the Renaissance Man of the avant-garde, his prolific skills having manifested with equal success in diverse media: sketches and paintings, eel animation, paint of film, live-action films, essays and kinetic sculpture. Always the innovator, he has never bound himself to one mode of expression, choosing instead that which best suits his creative need.

Len Lye‘s Greenwich Village loft is an airy workshop, filled with the tools of the artist’s trade: machine saws, diagrams, models of projected works, and several silvery kinetic pieces glistening in the summer afternoon’s light. Len Lye himself is the Renaissance Man of the avant-garde, his prolific skills having manifested with equal success in diverse media: sketches and paintings, eel animation, paint of film, live-action films, essays and kinetic sculpture. Always the innovator, he has never bound himself to one mode of expression, choosing instead that which best suits his creative need.

For more than 50 of his 75 years he has pursued his quest of motion composition. As a teenager in Wellington, New Zealand, he had his first glimpse of the potential of this art form while delivering newspapers at sunrise. His attention was caught by the movement of clouds and he began to ponder creating artificial clouds to achieve that same quality of motion. “I thought then and there, ‘Why clouds? Why not try to compose motion yourself? — compose motion!”

After this “revelation”, he found the idea was not so easy to implement. “I tried to control motion, and I nearly broke my back. Christ, how do you? So I worked out shafts and handles that could be turned and stuck through shafts so the turning shaft could turn the particular stuff you’d stuck to it; and it was a crazy kind of attempt to control motion and compose it. I was having a ball nevertheless.”

Hoping to learn more about film, Lye moved to Australia in 1922, because New Zealand had no cinematic equipment. He worked at a Sydney studio that made animated advertising shorts. “I learned animation in Sydney, not too much because I was doing storyboards. But I took the job just to be around where people were handling film, just to see.”

Here he chanced upon the concept of “cameraless animation”: “I didn’t invent scratching on film. I saw some guys that had made some marks on it and I rather liked the way they went (through the projector) wiggling like that, you see. I scratched a few feet of film myself, so I kept that in the back of my mind. And then I saw something like it again from a German film crowd. I think it was also some kind of scratching that they did on film. I kept that in mind too.”

Here he chanced upon the concept of “cameraless animation”: “I didn’t invent scratching on film. I saw some guys that had made some marks on it and I rather liked the way they went (through the projector) wiggling like that, you see. I scratched a few feet of film myself, so I kept that in the back of my mind. And then I saw something like it again from a German film crowd. I think it was also some kind of scratching that they did on film. I kept that in mind too.”

These experiments inspired him to adapt his own kinetic works to cinematic technique: “I suddenly realized that films had cuts and sequences. Editors can chop it where they want to. So, instead of having handles and shafts to control motion, I could just swing (objects) on a string or hold them in a black velvet glove against black velvet or whatever; you could really control and make things happen in terms of sequential motion.”

The Russian Revolution had at first created an amazingly fertile environment for the arts, and for the first time film was being considered from an artistic rather than a commercial viewpoint. Later came barbaric suppression. Lye originally planned to travel to Russia, where he hoped to get a job with the Meyerhold Theatre. He worked his passage from Sydney to London on the White Star liner EURIPEDES as a stoker, arriving in 1926. Some fortunate events enabled him to remain in London to work on his first film, TUSALA VA. “I got all sorts of fabulous help that nobody would get now. For example, as a kind of caretaker, I got a rent free barge to work on, plus the use of part of a studio to which the barge was moored on the Thames. I got a promise from the first film society in the world (London Film Society) that they would pay for the photography. And so I settled down for two years worth of animation drawings.”

One of Lye’s early stylistic influences was primitive African and South Seas tribal art. “When I first came to London I didn’t quite know what sort of imagery would carry my figures of motion. I had lived in Australia and often wondered what on earth an Aussie ‘aboe witchitty grub’ dance looked like. To get the spirit of the imagery I also imagined I was myself an Australian aboriginal who was making this animated ritual dance film.” The articulated grublike forms in TUSALA VA are reminiscent of designs on aboriginal shields, but they are dynamic moving forms. The animation was painstakingly tedious. “These goddam grubs were animated sideways, like cogs in a bicycle chain. Each cog had to be animated separately. And there were about 20 of these bloody cog-links, they all had to be animated. Why the hell I picked on that I don’t know. Well, I just plodded on, about 16 hours a day; it turned out to be both the slowest motion and the slowest animation on God’s earth!”

TUSALA VA was received rather coolly after its 1928 premiere. “Except for the art critic Rogar Fry, there was just a big silence, a complete and utter silence.” Lye found himself without the means or the support to produce another film by eel animation, and he began to consider animating without a camera, recalling his Australian experiences. “I had already used up all my goodwill stuff with the Film Society. I didn’t have much spare cash and I used to go out to some friends in Baling Studios, London, and hang around — anything to get a job in films. I used to get the old n.g. sound takes, that is, clear film with just a skinny track on one side. I would then scratch and paint and mess around with these bits of film. I would join them together and take them up the GPO Film Unit where I had some friends and run it. All this was done under the counter, you know, on lunch hours.

“I hit some marvelous effects (with) wet paint on a strip of clear film; for instance, you take an ordinary fine tooth comb and just wriggle it as you go down the length of film in the wet paint and it makes a lot of striated wavy lines. So you run it. With all these fancy abstract designs going on, the film had a very peculiar abstract quality. I was very taken by it, but didn’t have much chance of developing it.”

With the help of a composer named Jack Ellit whom Lye had met in Australia (“he was the only fellow there of the whole lot of people I knew who had any understanding of contemporary art”), he ran his film to a catchy recording of a Cuban beguine. He presented it to John Grierson and Alberto Cavalcanti at the British Government’s Post Office Film Unit. He suggested they add some slogans to the end of it. Then, with the help of Ellit, he synchronized his painted film and turned it into a public service film; and so COLOUR BOX was released in 1935, informing delightful audiences about new low parcel post rates. “A Utopian bit of public service,” thinks Lye.

The success of COLOUR BOX resulted in subsequent films for the GPO: RAINBOW DANCE (1936), TRADE TATTOO (1937), and MUSICAL POSTER ttl (1939); as well as several advertising films: KALEIDOSCOPE (1935), for Churchman’s Cigarettes and COLOUR FLIGHT (1939) for Imperial Airways. All these films have in common the abstract “cameraless” technique used in COLOUR BOA’as well as an infectious synchronized score taken from classic jazz and Latin recordings.

The success of COLOUR BOX resulted in subsequent films for the GPO: RAINBOW DANCE (1936), TRADE TATTOO (1937), and MUSICAL POSTER ttl (1939); as well as several advertising films: KALEIDOSCOPE (1935), for Churchman’s Cigarettes and COLOUR FLIGHT (1939) for Imperial Airways. All these films have in common the abstract “cameraless” technique used in COLOUR BOA’as well as an infectious synchronized score taken from classic jazz and Latin recordings.

TRADE TATTOO is Lye’s most ambitious film (“That one’s got to be the most complex film ANYBODY’S ever done”). Lasting but six minutes on screen, it employs some of the most sophisticated editing, montage and processing effects yet seen. Using black-and-white footage from GPO documentaries, Lye combines stencilled patterns, titles and animated effects to form a brilliant montage. Each of the four layers of images that make up the final print had to be exposed three times via the old 3-color Technicolor process, requiring a total of 12 separate processes to arrive at the final color print (“the lab went crazy”). In addition, the footage was tightly edited, employing jump cuts and color reversal to synchronize with the highly percussive Rhumba and Conga beat of the score; once again, Lye was assisted by Jack Ellilt as music director. As one can imagine, the total effect is startling. Even today, some 40 years after its conception, its avant-garde approach still seems fresh and contemporary, capable of rousing an audience to cheers.

Len Lye turned his hand to live action films, directing several shorts for the GPO. In 1944, he was invited to America to direct films for the “March of Time”. Although his 1958 short abstract film FREE RADICALS won the Silver Medal at the Brussels World’s Fair, Lye began devoting more of his time to kinetic sculpture. “My type of film, which is a short film, might take me eight months; and it’s very definitely fine art, not folk art in any shape or form. I take eight months to make five minute’s worth of film. Nobody is going to pay me for any of those eight months. And in any case, it’s a pain in the neck to have a five-minute film. How’s it going to be laced up and tied in with the rest of the program? People go to a movie house to see a program of at least ninety minutes, and they couldn’t care less whether they miss a five-minute fine art job. So my films were a complete anomaly.”

Len Lye turned his hand to live action films, directing several shorts for the GPO. In 1944, he was invited to America to direct films for the “March of Time”. Although his 1958 short abstract film FREE RADICALS won the Silver Medal at the Brussels World’s Fair, Lye began devoting more of his time to kinetic sculpture. “My type of film, which is a short film, might take me eight months; and it’s very definitely fine art, not folk art in any shape or form. I take eight months to make five minute’s worth of film. Nobody is going to pay me for any of those eight months. And in any case, it’s a pain in the neck to have a five-minute film. How’s it going to be laced up and tied in with the rest of the program? People go to a movie house to see a program of at least ninety minutes, and they couldn’t care less whether they miss a five-minute fine art job. So my films were a complete anomaly.”

Nevertheless, Len Lye is still deeply involved in the creation of a new iconography, encompassing all the arts — a new understanding of the relationship mankind, myth, and creativity have in the scheme of life. “I think Art is the only way you can isolate the creative essence of humanity. This essence, like happiness, is individuality. Civilizations and religions may fall down the drain, but their arts remain. It takes the avant-garde to best symbolize the vitality of creativity. There are a lot of great parallels between great, or everlastingly evocative, happiness and great art. This relationship is mainly about value — human value, and it can teach us how to get the most out of ourselves, and life, that we can.”

Photos:

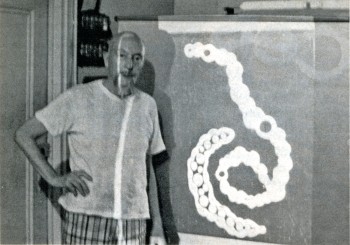

1. Len Lye and a slide from Tusalava (1928) (Photo by John Canemaker)

2. Trade Tatoo by Len Lye (Courtesy of Cecile Starr)

3. Rainbow Dance by Len Lye (Courtesy of Cecile Starr)

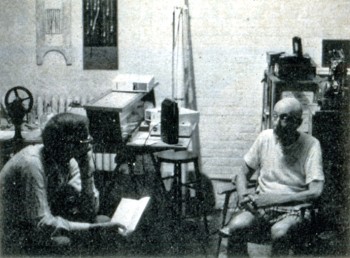

4. Joseph Kennedy (L) interviews Len Lye (photo by John Canemaker)

Joseph Kennedy is a New York City schoolteacher and a freelance writer. He has taught film history at Regis High School and he reviews films for Film news.

The magazine gave the above short bio about Mr. Kennedy in the Contributors column. Joe is a friend, and I am aware of how limited this makes his work seem (given that it was written in 1977.) He subsequently became a public relations executive and now has his own corporate communications practice; he worked with John Canemaker and Peggy Stern on The Moon and the Son and Chuck Jones: Memories of Childhood.

There is more information about Len Lye at several websites.

The Govett-Brewster gallery gives some good information about the man and his work.

Senses of Cinema offers an extensive bibliography of books and articles about the man.

Several of his film are available on YouTube (of course) in slightly degenerated versions:

Color Box

Swinging the Lambeth Walk

Particles in Space

Kaleidescope

Articles on Animation 13 Feb 2009 08:50 am

Heidi’s Song

- Animated features, like some of the shorts, come and go. While working on it, there’s often an expectation that THIS will be the film to catch gold and change history. It doesn’t happen often.

Looking back on a puff piece from some past feature is oftentimes ludicrous; sometimes it’s just sad. Here’s a 1981 story from Millimeter Magazine about Hanna Barbera’s upcoming feature, Heidi’s Song. It sounds like it may be the future, but really it’s even hard to remember the film. It certainly didn’t change the world.

Will HEIDI’S SONG be its SNOW WHITE?

by John Canemaker

Hanna-Barbera Productions Inc. is such a giant corporate entertainment entity that it prompts the old joke: What does a two-ton canary sing? Any damn thing it wants! This Hollywood “canary” tias expanded since 1957 to become the wold’s largest producer of animated TV series andspecials; more recently Hanna-Barbera has become involved in themed amusement parks and live action movies for television.

Now H-B is eager to enter and conquer the sacred Disney domain of fully animated, “quality” feature-length animated films for theatrical release. William Hanna and Joseph R. Barbera hope to do so with an expensive flourish this summer when they will premiere HEIDI’S SONG, a $9 million cartoon feature that has been in production for five years. The film’s staff of 200-plus includes 12 background painters, 60 assistant animators, eight layout people, and 18 top character animators. All cut their teeth years ago at the Disney studio, or at MGM, working with Hanna and Barbera during their halcyon days in the 1940s and ’50s producing Tom and jerry shorts and animated segments for live action features such as Jerry the Mouse dancing with Gene Kelly in ANCHORS AWEIGH.

A moment of menace for Heidi whose voice is dubbed in by

Broadway actress Margery Gray in the Hanna-Barbera feature.

Joseph Barbera claims HEIDI’S SONG will be “a step forward in animation that’s very exciting.” But perhaps it will actually be a welcome artistic step back—a comeback of sorts—for Hanna and Barbera, who were once considered by their peers and the public to be superior cartoon craftsmen, winners of seven Academy Awards for two decades of beautifully timed and fully animated Tom and Jerry cartoons. In the 23 years since forming their own company—a factory geared to the production of “limited” animation series, a reduced form of animation that, as an H-B publicity release points out, “ignored the time-consuming and expensive detail that would not be visible on the dimly lit video screen”—Hanna and Barbera have produced over 20 TV specials and some 60 series (“Huckleberry Hound,” “Yogi Bear,” “The Flintstones,” “The Jetsons,” “Scooby & Scrappy Doo,” and so on).

In other terms, H-B produces more film footage in a week today than it did in a year at MGM. The principals’ choice to, as they say, “exploit a niche Disney had missed in family entertainment, with low cost cartoons for television,” has made the two men cartoon tycoons, rich beyond their dreams. They claim “there is not one hour out of every 24 that a Hanna-Barbera cartoon is not entertaining some segment of the world’s population.”

When, in 1967, Taft Broadcasting Company of Cincinnati acquired H-B, the company expanded its operations into five themed amusement parks, including Kings Island (Cincinnati) and Marineland (Los Angeles), where life-sized replicas of H-B characters—Yogi, Huckleberry et al — roam about greeting visitors. More than 1500 licensed manufacturers world-wide turn out 4500 different products bearing likenesses to H-B characters, for example, Flintstone window shades, Scooby-Doo pajamas.

In 1978, H-B won an Emmy, this time for a live action TV movie, “The Gathering,” starring Ed Asner and Maureen Stapleton; more live action films are planned for theatrical release and TV. With all this success, why would Hanna-Barbera bother pouring money into turf that is traditionally Disney’s and has proved to be a producer’s graveyard, from GULLIVER’S TRAVELS (1939) to RAGGEDY ANN & ANDY (1977)?

Company is built on cartoons

One should not forget that cartoons are the heart of the H-B corporate structure (as they are at the Disney studio). And it must be noted that as popular as the TV series are with small children, there is, to Hanna and Barbera’s distress, a persistently vocal, mostly adult contingent that just plain doesn’t like their cartoons! Veteran animator/director Chuck Jones, for instance, dismisses the whole breed of limited animation TV fare as “illustrated radio!” Writer Leonard Maltin once denounced H-B cartoons as “consciously bad: assembly-line shorts grudgingly executed by cartoon veterans who hate what they’re doing.”

Years of this kind of criticism (and worse from TV critics, parents groups and, most painfully, professional peers) has hit Hanna and Barbera right in their pride of craftsmanship. Witness Bill Hanna’s responses during an interview with Eugene Slafer: “Are you accomplishing what you believe is good TV animation?” asked Slafer. “No, I do not,” came

Years of this kind of criticism (and worse from TV critics, parents groups and, most painfully, professional peers) has hit Hanna and Barbera right in their pride of craftsmanship. Witness Bill Hanna’s responses during an interview with Eugene Slafer: “Are you accomplishing what you believe is good TV animation?” asked Slafer. “No, I do not,” came

__Director Robert Taylor states that HEIDI’S SONG has _______Hanna’s candid reply.

__“a style unto itself, more like a live action picture in_______ To a further probe, “Have

__the staging, as opposed to what you’d see in animation.”____you ever been ashamed of your work, especially since parents have ranted about the general lack of quality on Saturday morning cartoon shows?” Hanna admitted, “Actually I feel like I should crawl under a seat sometimes.”

Joe Barbera recently spoke with Millimeter about his partner’s abilities to recognize the difference between good and bad quality animation and their alleged lack of craftsmanship. “We had to get that stuff out for Saturday morning,” he explains. “That’s a budget problem. Believe me, I don’t stand still for people saying, ‘Oh, they’re doing junk! They don’t know how to do…. ‘We’re not doing that. We only do it because you don’t get the money to do it differently. When we get the money —and you’re talking about millions—we doajob!”

So perhaps the initial thrust for the HEIDI feature came from Hanna’s and Barbera’s desire to prove they haven’t forgotten how to produce animation in the “classical” style, or how to create memorable characters that affect more than an audience’s funny-bone. Of course, Hanna and Barbera are too business-wise to produce a full-animation feature merely to assuage pain dealt their pride; there also had to be a bedrock of financial motivation behind the move and, sure enough, there was. “The thrust,” states Barbera, “was to do one every year and to build a superb perennial library, which Disney had for years.”

The Disney animated features, from SNOW WHITE (1937) to THE RESCUERS (1977), are re-released like clock-work every seven years, just in time to greet a new generation or to remind an older group of their existence. “They are,” says Barbera admiringly, “forever pictures;” that is, films that keep the Disney empire well-oiled with money derived from box office returns (pure profit, since there are no production costs on re-releases), and from lucrative merchandising spin-offs, like comic strips and dolls for themed amusement park rides. This money-making machine depends upon the public’s continuing affection for the cartoon characters and their “classic” stories found in the Disney features. Hanna and Barbera have not yet fully entered this profit arena, but they have been working on it.

Previous animated features

HEIDI’S SONG is not H-B’s first attempt to produce an animated feature. There was, for example, HEY THERE, IT’S YOGI BEAR in 1964 and A MAN CALLED FL1NTSTONE in 1966, both low-cost, limited animation, based on the one-dimensional characters from TV. Neither film was a “forever” picture.

There was,”in 1973, an H-B version of E.B. White’s book Charlotte’s Web, but this, too, suffered from the taint of limited animation and questionable production values. Reviewer Vincent Canby of The New York Times said of the film, “Parents will survive it, and so will the children.” Barbera acknowledges there was “a problem” with CHARLOTTE’S WEB, but to him it was a misjudgment of the financial potential of the material. “Charlotte’s Web,” says Barbera, “is an American classic. It is not an all-world classic. Germany ended up calling it Zuckerman’s Pig, after the name of the man who owned the pig in the story, because who ever heard of a Charlotte’s Web? The film version is recouping some of its money on Home Box-Office TV, on video cassettes and in non-theatrical markets, a fate H-B hopes to avoid for HEIDI’S SONG.

While Disney can produce almost any project known or unknown because of the sales value inherent in the name, “Disney,” Hanna-Barbera is not yet in that sublime position. To the general public, “Disney” means full-animation, perfect technological craftsmanship, beloved characters in stories containing mythic or nostalgic associations. To the same public, “Hanna-Barbera” means limited animation of flat characters on redundant television series. H-B seeks to improve its image with HEIDI’S SONG.

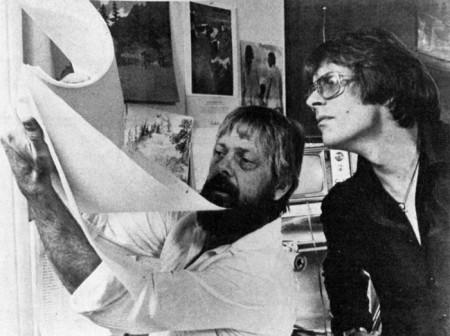

Animator Charlie Downs (left) flips drawings for director Bob Taylor.

HEIDI’S SONG is the story of an orphan girl, based on Johanna Spyri’s 100-year-old, internationally known book. The cartoon feature contains a”Broadway” score of 16 songs by veterans Sammy Cahn (lyrics) and Burton Lane (music). The characters’ voices include Lome Greene as Heidi’s reclusive grandfather, Broadway actress Margery Gray as Heidi, and Sammy Davis, Jr. as King Rat, leader of a band of rodents. Other characters include a “mean and scary ancient housekeeper,” Fraulein Rottenmeier; Sebastian, “the butler who helps Rottenmeier be miserable to Heidi”; Clara, a lonely girl “confined to a wheelchair”; Peter, “a young goatherd, agile as the animals he tends.”

Off-setting the human characters is a gaggle of animals; Spritz, Heidi’s “feisty” pet goat; Hooter, a baby owl who “warns Grandfather of Heidi’s imprisonment in the cellar”; Gruffle, Grandfather’s “gruff old hound”; Schnoodle, a “nasty little dachshund who is rotten like his mistress, Fraulein Rottenmeier.” There is also a “crusty” German Schnauzer, a white mare, a white kitten and the aforementioned royal rat, “the power-loving and peppy leader of the rats in Sebastian’s basement, who spurs his clownish rodents into a strong force to attack Heidi.”

“We do have our animals,” points out Barbera. “My gosh, if we don’t have animals, we’re in big trouble,” he notes with an eye toward audience appeal and merchandising. “But we do have humans and some marvelous dancing,” he continues. “We are not rotoscoping,” he says, referring to the technique of animators tracing frame-by-frame projections of live-action. “I don’t care for rotoscoping at all.”

Choosing talent

Hanna and Barbera have instead hired a team of 20 top character animators—”Let’s use the word humbly and respectfully: the old-timers, “adds Barbera—people like Hal Ambro and Charlie Downs, both of whom specialize in human figure animation and have worked on films such as Disney’s PETER PAN and Richard Williams’ RAGGEDY ANN & ANDY. There are also master animators of animal caricatures and comic timing, such as Irv Spence and Ed Barge, veterans of the fine Tom and ]erry shorts. Th’e great Disney/MGM animator, Preston Blair, was also involved with HEIDI for a time.

One might assume that the difficult task of manipulating the drawn human form in full animation is what kept the film in production for five long years. Barbera, however, offers this explanation: “When we are in the slow season, which happens in television all the time, everybody has to be laid off. We were going to keep people busy on the feature. We found that doesn’t work. The kind of people you use on a feature are the old super-pros of our industry, and there are few of them left.

One might assume that the difficult task of manipulating the drawn human form in full animation is what kept the film in production for five long years. Barbera, however, offers this explanation: “When we are in the slow season, which happens in television all the time, everybody has to be laid off. We were going to keep people busy on the feature. We found that doesn’t work. The kind of people you use on a feature are the old super-pros of our industry, and there are few of them left.

“Secondly, we wanted to use HEIDI’S SONG as a training ground for new animators. The first three or four years the picture would go into production and stop, then go back into production and then stop. That was not good for the picture. We were losing momentum, the enthusiasm of the artists and the excitement we wanted to build up. So finally, about a year and a half ago, we marshalled the last remnants of

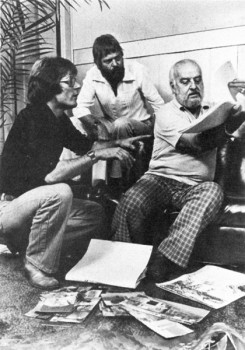

__Bob Taylor, director, and animators____ what we think are the best people in the

__Charlie Downs and Hal Ambro. ________business. When we brought these people in we had to change directors. We had a fine guy, but he had forgotten how to go back and really work these old-timers — really get the good animation! We then hired a brilliant young director, Bob Taylor, who is dynamite!”

Prior to rejoining H-B a couple of years ago (he had first worked there in 1966 for one year), Robert Taylor worked for Ralph Bakshi, Steve Krantz, DePatie-Freleng and Murakami-Wolf. “I always seem to come in on things that are hopeless,” he commented recently, “and we try to turn them into hopeful. I think we’ve done it with this picture. For me and the whole crew, and for Joe and Hanna-Barbera and Taft, this is our entrance into real good quality stuff!”

It has not been a piece of cake for Taylor. When he took on the HEIDI assignment, the script was written and the tracks were already recorded. “It was a hang-up for me,” he admits. “That’s the albatross around my neck. The story is episodic. If I had written it, I would have made it a little stronger in terms of her emotions and some of the dialogue. But,” he adds brightly,

I “my whole trip is to keep the audience entertained—get people to go to animated films and make them feel when they come out that they’ve seen something they can’t see anyplace else. It isn’t so much the tools;

i it’s what the hell I’m trying to do with it.”

Trying to elicit a description of the film’s style from both producer and director is difficult. According to Barbera, “The results have been what I call a Hanna-Barbera feature. It is not going to look like a Disney picture, or a FRITZ THE CAT or a RAGGEDY ANN & ANDY. We have our own style.” When pressed, Barbera cites “some very imaginative pieces of business.” Pressed further: “We’re not holding back. When they lock Heidi in the cellar, that’s a scary place—to be locked in a basement in a house in Frankfurt in the 1880s, that’s enough to put you away. We’re not holding back, yet we’re keeping it in good taste throughout.”

New wave animation

Taylor was a bit more specific: “I hate to opportunity for the guys to get back into what it’s really all about. We take as many new animators as we can bear—the ones that have the enthusiasm and are really interested in what we’re calling a ‘renaissance.’ But even more important, we are just interested in making great animated films and updating them into the 1980s.”

The HEIDI unit has already begun production of its next two animated features, ROCK ODYSSEY (which Barbera describes as “a marvelous treatment of music from the 1950s, ’60s and 70s. A rock-FANTASIA, if you want to call it that”), and NESSIE COME HOME, a tale about the Loch Ness monster. Again, the thinking behind the choice of both projects is carefully calculated toward maximizing box office. “If you are going to do a feature,”reasons Barbera, “you must have something people will identify with. You can’t do ‘Willie the Glowworm!’ That’s why HEIDI is so great. It’s always a problem finding material. Watership Down is a marvelous book, but we would have hesitated to do it because it’s just not that well known. It’s a gamble. You have to put four to five million dollars into something like that.”

Marketing concepts for animated features

At a time when Disney films are attempting to woo an older (“PG”) audience, one wonders why Hanna-Barbera appears to be aiming toward a traditional, family-oriented “G”-rated audience with its animated features. Barbera explains: “First of all, anything that Disney has done is going to play forever, so he will have that constant market in every media. Secondly, the theater audience isn’t going to be the only audience. There are going to be cassettes, a perennial that will run forever. And thirdly, we are going to have our own style. We’re not going to have a picture that will be only for kids. We will get the adults with this one.”

“ROCK ODYSSEY,” continues Barbera, “will appeal to those between the ages of 18 and 35, but we will not lose the kids because of the animation. And we will have the adults that remember those ’50s and ’60s songs. NESSIE will have a great, I hate to use the word, ‘environmental’ appeal, but we will be protecting a character that’s getting it. If there are monsters in that lake, they get bothered—by submarines, depth bombs, cameras—more than any character in the world. We have a very unusual twist that will make it appealing.”

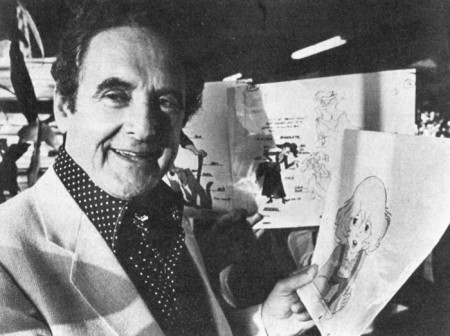

Joseph Barbara, executive producer, displays color models that some

150 animators used for reference while working on HEIDI’S SONG.

Asked whether the future might see Hanna-Barbera producing adult-oriented features a la Bakshi, Barbera answers, “Oh yes, very much! We had a recent all-day meeting where the thrust was the fact that we can’t depend on the children audiences to pay for these things. We must attract the adults, too. Statistics show there are less children around now. So whatever we do, we must attract the adults.” Barbera must have been thinking of a recent Bakshi product, i.e., LORD OF THE RINGS, for when asked if he would produce an unquestionably adult cartoon such as HEAVY TRAFFIC or FRITZ THE CAT, he replied, “No! I don’t think we would do that! We certainly wouldn’t shy away from a gutsy project, but it must bring in the kids, too. So there would be no bad taste.” For the time being, it is significant that Hanna-Barbera is training an enthusiastic crew in the techniques of full, character animation, one form of the art that for the last two decades has seemed to teeter constantly on the brink of extinction. It is enough for now that H-B is producing with integrity and care a film like HEIDI’S SONG, which will attract and appeal to large audiences.

The success of Hanna-Barbera will keep an avenue open for future animated features, and hold the public’s awareness of and interest in the medium of animation itself. With an increase in the number of future animated features will come diversity in form and content. Animation

as a vital and viable entertainment medium will then come closer to realizing its potential, as it did in 1968 when George Dunning directed YELLOW SUBMARINE, and in the early 1970s, when Ralph Bakshi excited audiences, and, indeed, as in 1937 when a struggling young producer named Walt Disney redefined the genre.