Monthly ArchiveNovember 2011

Books &Commentary 10 Nov 2011 06:45 am

Lutz

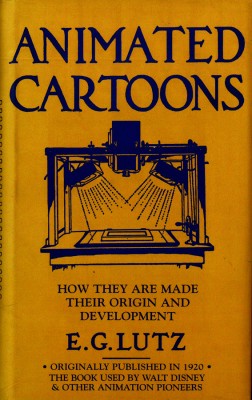

- This week, I posted a review of E.G. Lutz’ book, Animated Cartoons: How They Are Made, Their Origin and Development, and I commented that I have had this curiosity about who E.G.Lutz actually was. A quick Google search for biographical information comes up with nothing other than the Amazon listing of his books for sale and the references to him in other animation books.

It was a bit of a surprise to me to find that his singular animation book, published in 1920, is definitely not his best selling book. That would be Drawing made easy; A step by step guide to drawing for young artists. There are also another half dozen books he’s either written or illustrated.

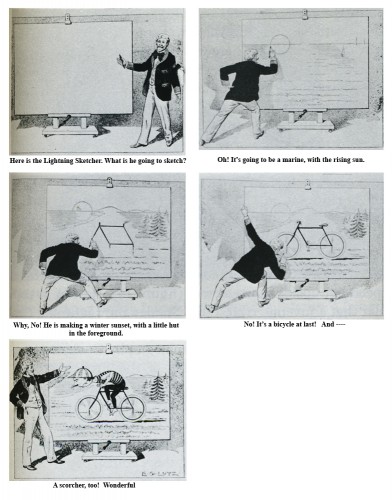

I decided, then, to look in all of the books I own. The best place to start was with Donald Crafton‘s book, Before Mickey. Sure enough, there was an illustration by Lutz that was done in 1897. It depicted the “Lightning sketcher.” These were the artists who appeared on stage in Vaudeville theaters sketching an image at “lightning” speed. Georges Méliès enjoyed doing this for a while, and J. Stuart Blackton put it on film. Lutz illustrated such an artist.

I’ve had to do a little retouching in photoshop to get

this image to read well. I retyped all the text there.

Crafton later quotes the Lutz book:

- The first book devoted solely to the craft was Animated Cartoons; How They are Made, their Origin and Development by former caricaturist Edwin G. Lutz. This book became the vulgate of modern industrial animation, canonizing the major studios’ practices. Its guiding philosophy was embodied in the statement that “of all the talents required by anyone going into this branch of art, none is so important as that of the skill to plan the work so that the lowest possible number of drawings need be made for any particular scenario.” Lutz illustrated the book with his own rather quaint drawings. He described peg registration, in-betweening, speech balloons, and studio organization, but curiously his description of cels was limited to their use as static overlays.

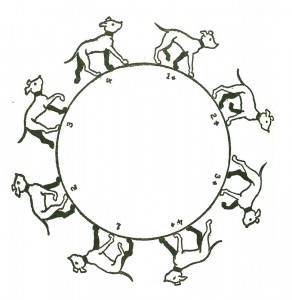

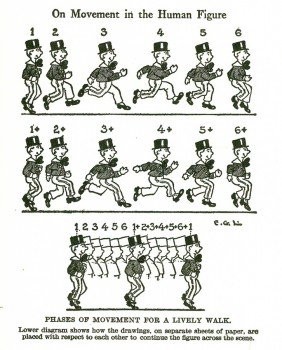

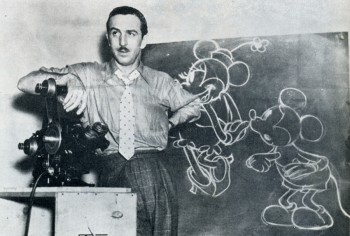

- Lutz’s book was a fountain of common-sense advice, such as limiting dialog so that films could be sold in foreign countries. Among its most important contributions were the detailed instructions for drawing perspective runs and other kinetic effects, which would grow increasingly visible throughout the 1920s, especially when combined with mobile and cycled backgrounds. Cycling, supposedly invented by Nolan, consisted of a sequence of eight drawings planned to match at the end of a cycle by making the first and eighth drawings identical. This effect may be seen in practically any 1920s studio production, but Paul Terry seemed to especially love it, With these and all the Other techniques explained in detail, almost anyone with the ambition could begin making animated cartoons. Of these neophytes, certainly the most ambitious reader of Lutz was Walt Disney of Kansas City—who, because he could not afford to buy it, checked the book out of the public library.

This, of course, is the story of how Walt Disney pored over the book slavishly to find out the tricks of the trade. Mike Barrier in his book, The Animated Man, describes this well:

- (Disney) was essentially self-taught as an animator; he wrote to an admirer many years later, “I gained my first information on animation from a book . . . which I procured from the Kansas City Public Library.” . . . According to its copyright page, Lutz’s book was published in New York in February 1920, the same month Disney joined Kansas City Film Ad, so he must have read it very soon after it was added to the library’s collection. He said of the book in 1956: “Now, it was not very profound; it was just something the guy had put together to make a buck. But, still, there are ideas in there.”

- As elementary as the Lutz book was, it still offered a vision of a kind of animation far more advanced than the Film Ad cutouts. Lutz wrote at a time when animators commonly worked entirely on paper. They made a series of drawings, each different from the one before, that were traced in ink and photographed in sequence to produce the same illusion of movement that Film Ad achieved by manipulating cutouts under the camera. Lutz advocated the use of celluloid sheets to cut down on the animator’s labor—the parts of a character’s body that were not moving could be traced on a single sheet and placed over the paper drawings of the moving parts. Such an expedient (and Lutz recommended others) would have resonated with Disney, who had been so impressed by commercial art’s shortcuts when he worked for Pesmen-Rubin.

Barrier also quotes Hugh Harman as saying, “Our only study was the Lutz book . . . that, plus Paul Terry’s films.”

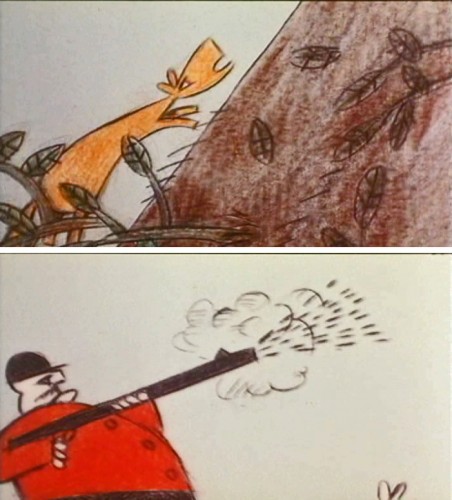

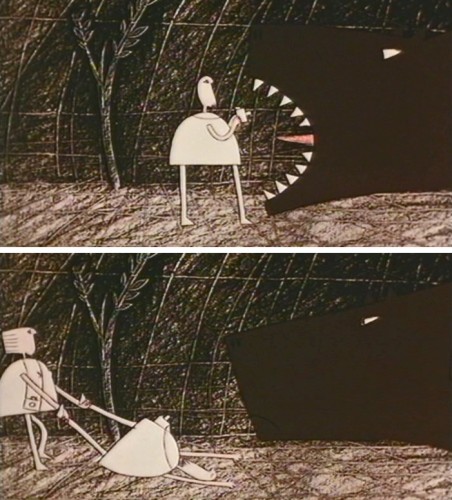

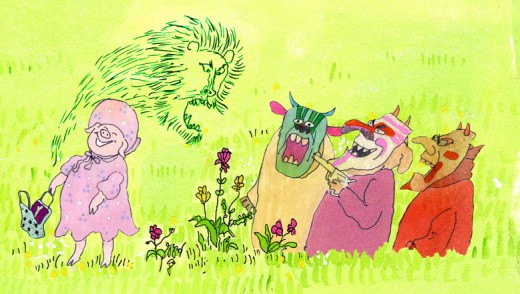

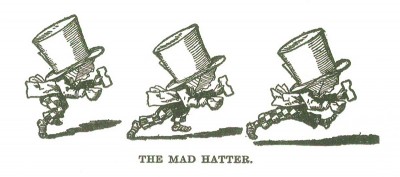

This is one of the illustrations Lutz did for his book,

The Animated Cartoon.

Donald Crafton talks extensively of the management theory of Frederick W. Taylor. Taylor basically stated that lower paid jobs should be done by lower paid employees on what would basically become an assembly line. This was adapted by J.R. Bray and Thomas Ince. The Inbetweener was born. Crafton writes:

- In his 1920 manual, Lutz was still promulgating the taylorist philosophy—for example, when he described the tracers’ function in language echoing Bray. “It can be seen from this way of working in the division of labor between the animator and his helper that the actual toil of repeating monotonous details falls upon the tracer. The animator does the first planning and that part of the subsequent work requiring artistic ability.

Initially, Disney rejected this theory. This was something that Ub Iwerks brought to the studio after traveling from Kansas City to LA. We see this in Leslie Iwerks & John Kenworthy‘s book, The Hand Behind the Mouse:

- Ub brought the studio renewed energy and new techniques. Abandoning the stiff and rudimentary methods Or animation he had previously learned, Ub would begin to evolve bis own straight-ahead style of drawing, which did not rely on model sheets or extremes. A key aspect of the Lutz orthodoxy was pose-to-pose animation, in which, for any action, a character was drawn in its starting and ending positions (or “extremes”) and intermediate poses were filled in later. Model sheets were used to trace over the original figure, allowing the animator to simply alter the parts of the body that needed variation. Ub instead professed a new method. He felt he could coax more expressive feeling from a drawing if he used model sheets as rough guides rather than being chained to them. By trusting in his own creativity and sense of movement, he threw out all structure to make way for his own free-flowing impulses.

- Russell Merritt and J. B. Kaufman in Walt in Wonderland assert that “If Iwerks had made no other contribution to the Studio, he would deserve to be remembered for this one. It marked the beginning of the smooth, flowing ‘Disney style’ of animation; and one can see it developing, slowly but surely, as the Alice series progresses.”

We also know that one of the sore points between Disney and Iwerks, which helped cause Iwerks to leave the studio, was that Disney tried to force Iwerks to leave inbetweens for others to follow. This would get more animation out of Iwerks, who already had been the animator with the greatest speed. Ultimately, Disney fell back on what he’d learned from Lutz.

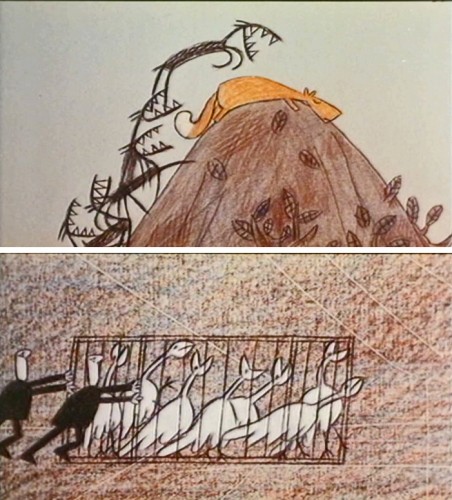

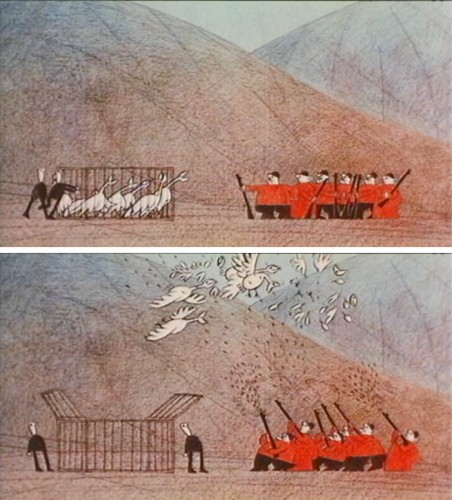

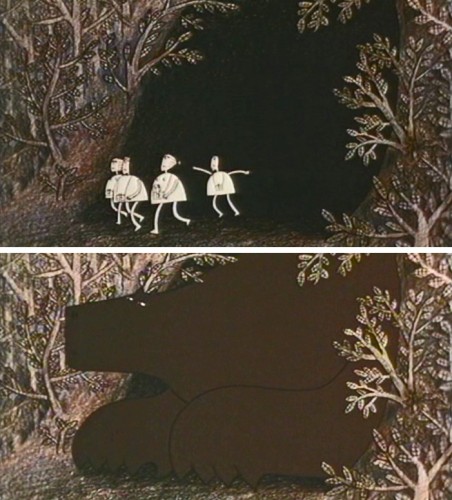

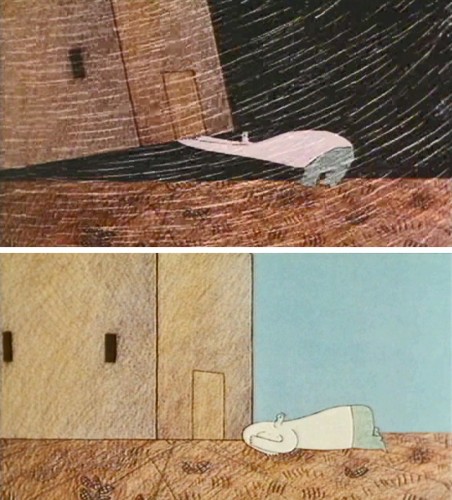

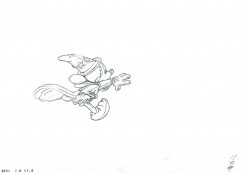

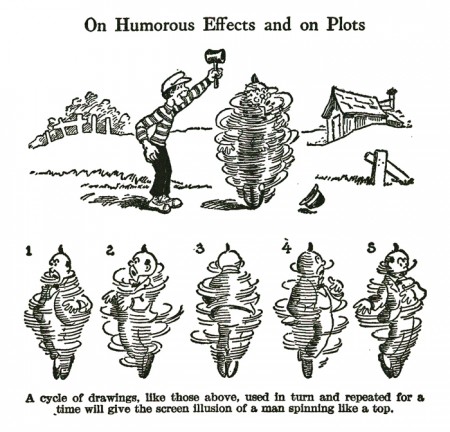

This is one of the illustrations Lutz did for his book,

The Animated Cartoon.

_________________

So, in the end, all this shows is that the Lutz book had a profound effect on animation in the developing 1920s. It also shows that Lutz did a lot of thinking about not only the process of how to make animated films and the technology available at the time of publication, but he thought of the methodology within a studio churning out many films.

We know from that initial “Lightning Sketch” illustration that Lutz was an artist. We also have to assume that he worked within an animation studio for some time to have been so thoroughly informed that he was able to describe the most meticulous details in the process of making films. Because he so completely details the workings of the camera (he also wrote a book in 1927 entitled The Motion Picture Cameraman) one would assume he must have spent some time actually shooting animation. I would guess that he started in that position, then moved into actually creating the art, as did Rudy Ising in the start of his career. It’s doubtful some producer wouldn’t use his artistic abilities in creating the animation.

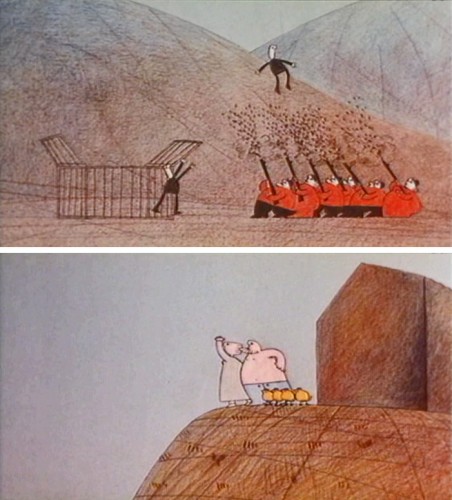

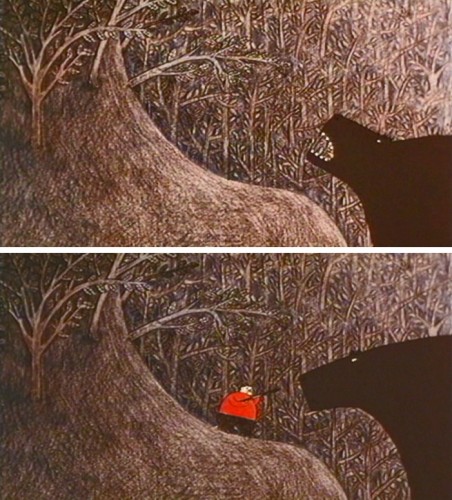

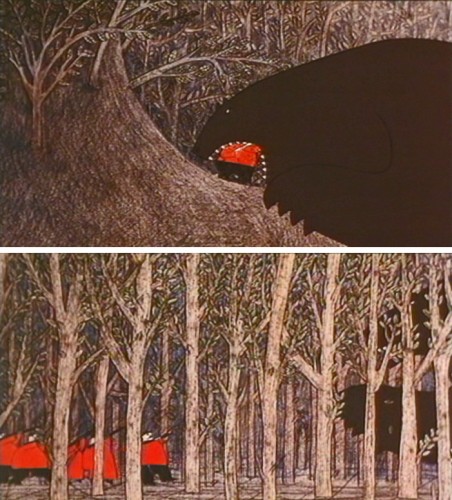

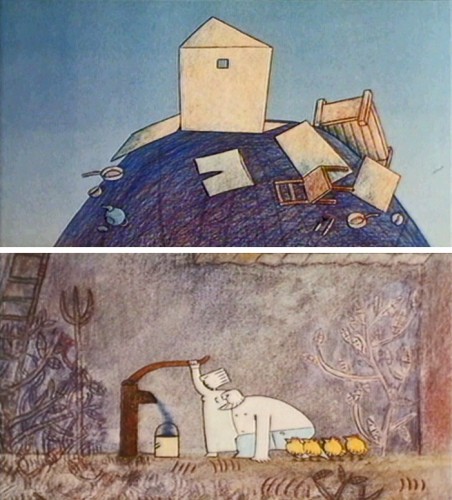

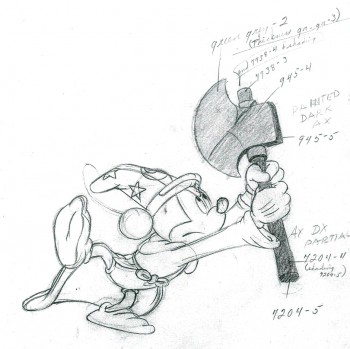

This is one of the illustrations Lutz did for his book,

The Animated Cartoon.

However, this is all speculation. Perhaps he just had a strong interest and was given the authority to sit and watch within a studio. Of course, that would lead one to believe that the studio that allowed him access would have been promoted within the book. Yet. there is no studio mentioned, hence I’m led to believe that he had to have worked within a studio for some time.

I haven’t gone much farther than the books in my studio or the information on the Web. In the end, I don’t know a heck of a lot more than I started out with. I do know that Lutz’ animation book was the most important he’d written. It affected an entire industry and changed the way the process was done in the all important formative years of the studio system.

If anyone has more biographical information on Lutz, please don’t hesitate to leave it. I’d like to know more and will keep on looking.

Daily post 09 Nov 2011 10:19 am

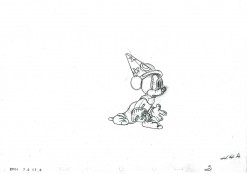

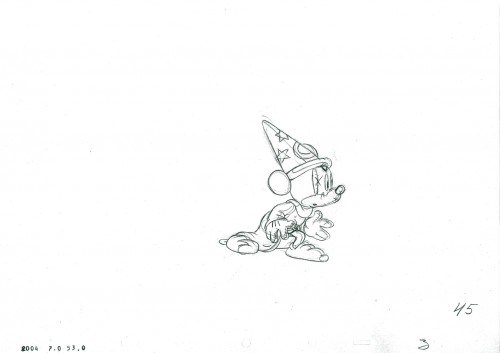

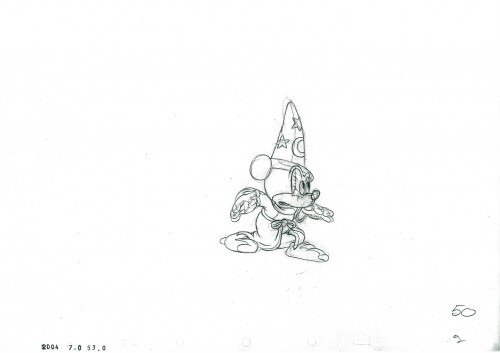

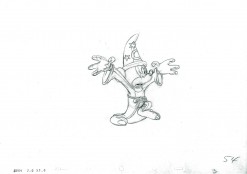

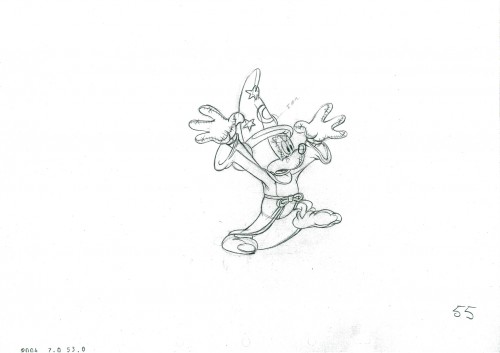

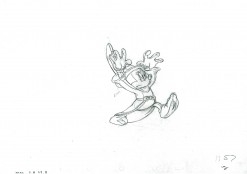

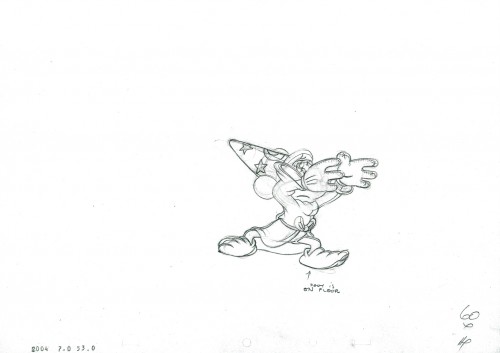

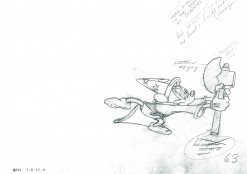

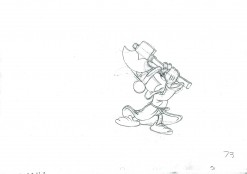

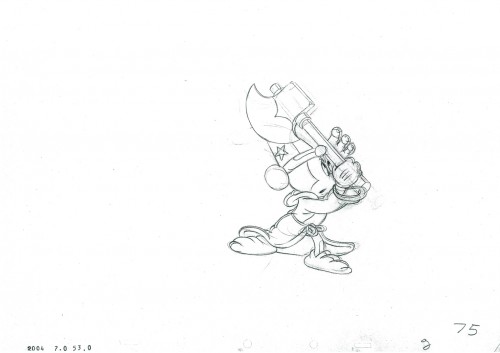

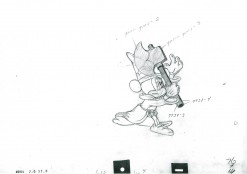

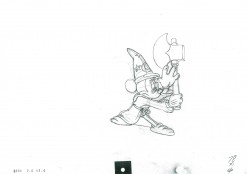

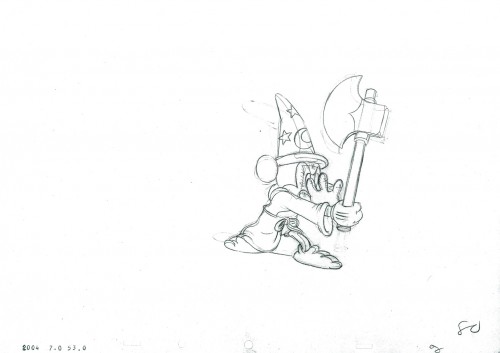

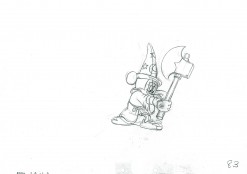

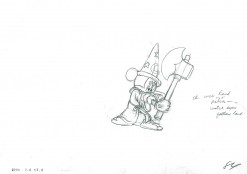

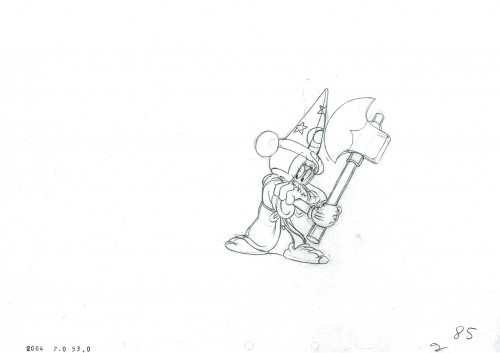

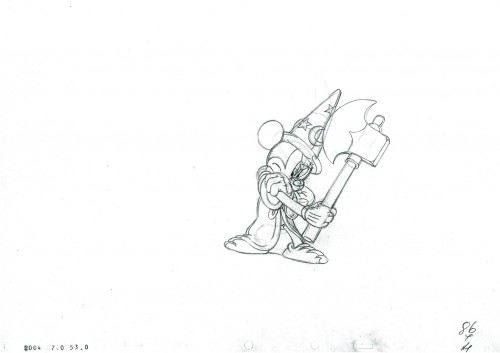

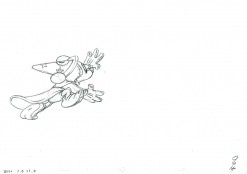

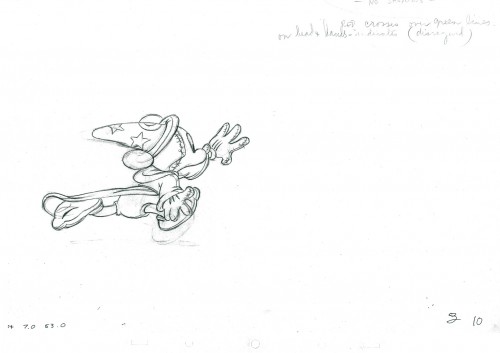

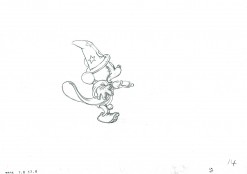

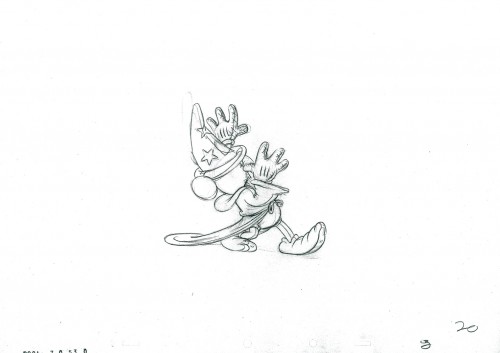

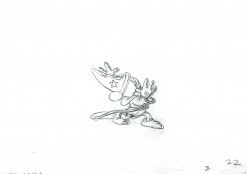

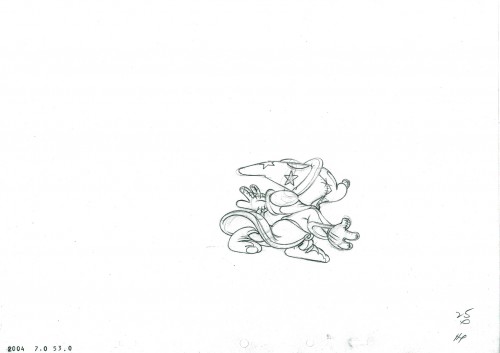

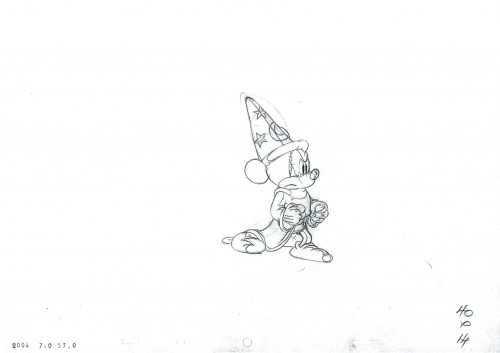

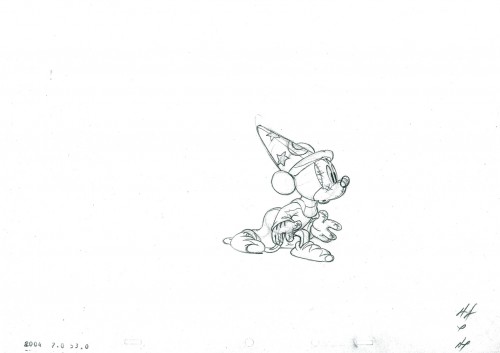

Mickey and the Brooms – 2

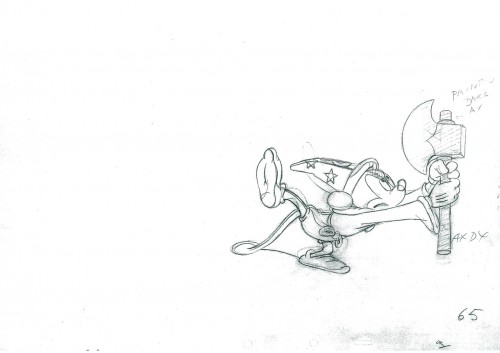

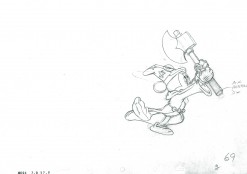

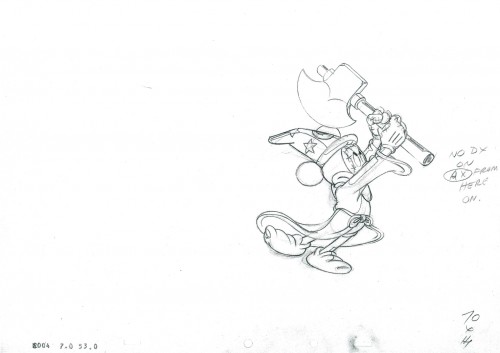

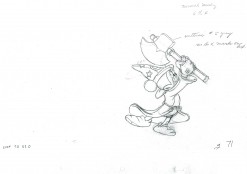

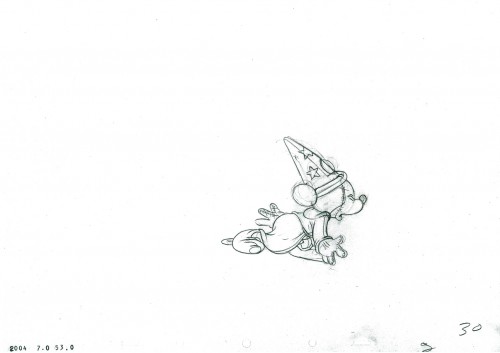

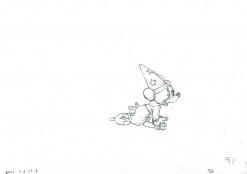

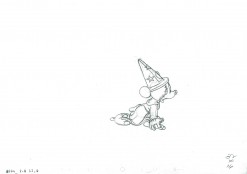

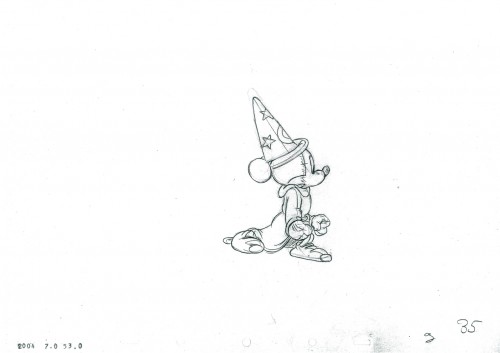

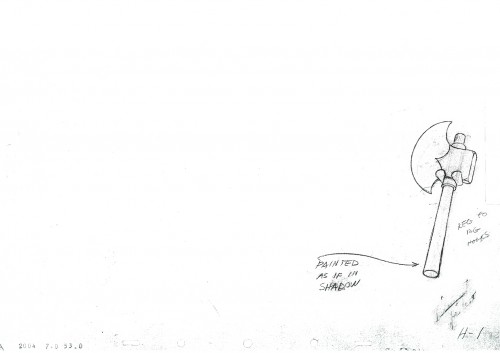

- Here I continue with the second part of Mickey’s action in this scene from Fantasia. Mickey and the brooms. The Mickey section of the scene will probably finish up next week, then on to the broom chopping shadows. There are a lot of those. We’ll keep it going until we’re done.

Riley Thomson animated this scene with an assist from Harvey Toombs.

Jim Algar directed this sequence.

This is production #2004- Seq. 7 – Scene 53. It runs 28 ft. 3 frs.

You can find out about all the scenes from Fantasia by studying the animator drafts posted in 2007 by Hans Perk on his site A Film LA, a great resource for animation study.

H1

H1

____________________________

The following QT incorporates all the drawings from this post

as well as the previous post, Part 1.

All drawings were exposed per the Exposure Sheets.

Books &Commentary 08 Nov 2011 08:12 am

Lutz’ “Animated Cartoons” – an Overdue Review

Animated Cartoons: How They Are Made, Their Origin and Development by Edwin G. Lutz is the first important book published about animation and how to do it. The book apparently had a lot of resonance with Walt Disney and his small Kansas City staff when they started out in making animated films. They borrowed a copy of the book from the library and studied it slavishly to learn how to make animated films.

Animated Cartoons: How They Are Made, Their Origin and Development by Edwin G. Lutz is the first important book published about animation and how to do it. The book apparently had a lot of resonance with Walt Disney and his small Kansas City staff when they started out in making animated films. They borrowed a copy of the book from the library and studied it slavishly to learn how to make animated films.

I’ve owned a copy of the book for at least the last thirty years but had not read it, so this week, I set myself to the task at hand. Surprise, surprise. I found the book not only interesting but informational. Yet not totally out of date.

Lutz starts out with a history of animation – no mean task for a 1920 publication. This amounts to comparing the differences between a praxinoscope and a phenakistoscope, a zoetrope and a thaumatrope. For quite some time, no book on animation would be complete without following the example of this book and revealing the evolution of the machinery that allowed for the animation of still pictures.

Once past this, it goes into the evolution of Motion Pictures, from Muybridge to Lumiere and Edison. The author has real knowledge of the 1920 motion picture camera and how it works, and he lets us in on the secrets.

Finally, with Chapter III, 57 pages into the book, we’re into “Making Animated Cartoons.” This is when some truly practical information is relayed. Not only the shape of a lightbox and the use of two pegs for registration but the explanation of using cels (primarily, for background overlays) and limited animation.

Some examples of the practical advice he gives:

- It’s revealed that using tempera to correct stray lines on the white linen animation paper might photograph as gray, and it would be better to cut out those lines and rub down the cut edges with an eraser.

- We learn that black velvet photographs truly black. (I knew this when Richard Williams told me in 1977, however Williams added that brilliant whites are found by using white blotter paper.)

- A cut-out object, such as an airplane, can be used to cross the screen with cut-out animation rather than having to redraw the plane endless numbers of times. However you have to be careful it doesn’t change perspective, or it will not work properly.

- A platen, flattening the art at the camera shooting, should be made of glass with a wood frame. If the frame is metal it can’t breathe and the glass may break. (They later figured out a suspension device with springs to allow some give.)

In point of fact, there are dozens of such mechanical tips in the middle of the book, and they’re really entertaining to read. I can’t remember any other book combining so many such photographic tips. Usually, “how to” books are about the animation, itself, not the camera design. Or they’re focused on the camera and not the animation technique. This book offers both and with some real knowledge.

In point of fact, there are dozens of such mechanical tips in the middle of the book, and they’re really entertaining to read. I can’t remember any other book combining so many such photographic tips. Usually, “how to” books are about the animation, itself, not the camera design. Or they’re focused on the camera and not the animation technique. This book offers both and with some real knowledge.

Of course, the book was written in 1920 so there’s only a limited amount we can learn about movement. They didn’t know that much until Disney had developed animation to a high craft in the 1930s. However, it’s astonishing, at least to me, to learn how much they DID know that early in the game. It’s also a surprise, given some of the illustrations in the book, how sophisticated some of the animation is. But then the very next series of drawings is crude and like something out of the Bray’s “Heeza Liar” series.

The latter part of the book goes into the construction of good gags (after all, animated films are about comedy, he tells us), and the conclusion seems to be that circuitous motions are the funniest. Lutz paraphrases Henri Bergson’s philosophy in explaining:

In a boisterous low comedy it is always incumbent upon the victim of a blow to reel around like a top before he falls. It never fails to bring laughter. An effect like this is easy to produce in animated cartoons. There is no need to consider physiological impossibilities of the human organism, the artist can make his characters spin as much as he pleases.

In a boisterous low comedy it is always incumbent upon the victim of a blow to reel around like a top before he falls. It never fails to bring laughter. An effect like this is easy to produce in animated cartoons. There is no need to consider physiological impossibilities of the human organism, the artist can make his characters spin as much as he pleases..

In a screen picture two boys will be seen fighting; at first they will parry a few blows, then suddenly begin to whirl around so that nothing is visible but a confused mass and an occasional detail like an arm or leg. It will be exactly like a revolving pinwheel. This is made on the film by having a drawing representing the boys as clinched and turning it around as if it were a pin-wheel.

.

In a panorama screen effect it seems to be sufficiently realistic, for laughter purposes, to have the legs and arms of the individual in a hurry give a blurred impression, in some degree, like that of the spokes of a rapidly turning wheel.

Lutz continues for six pages telling us how circular movements

provide gales of laughter for the audience. He just about

convinced me. I’ll be keeping my eyes open in the future.

.

The book ends with a discussion of the future. This, Lutz decides, is in educational animation. He gives examples of mechanical processes, such as pistons operating or gears in motion, or he mentions a device invented to teach deaf children to read lips. Oddly enough, this belief in the future of educating via animation was the same belief that both Fleischer and Disney had in the 1920s. I wonder if they got their notion of this future from Lutz. Interesting how both broke from this type of thinking when they found that there wasn’t much money in educational films. (Bray, on the other hand, did little more than educational work starting in the 20s and going well into the 50s. That man knew how to roust a buck.)

.

The book, Animated Cartoons: How They Are Made, Their Origin and Development is a good read, although the writing style is a bit stiff reflecting the style of its day. It’s almost Victorian in its stodginess. Accepting that – you always have to remember the book was published in 1920, yet there’s quite a bit to be found here. Any animator with one foot in the medium’s history really should read this book. It took me a few decades, and I’m sorry I didn’t get to it sooner.

.

While reading this book, I became particularly interested in who E.G. Lutz actually was. My limited research didn’t turn up a hell of a lot, but I did decide to share what I could find out. I’ll do it in another post, since I’d like to quote several other books in length, and it seems to be another direction than this review wants to take.

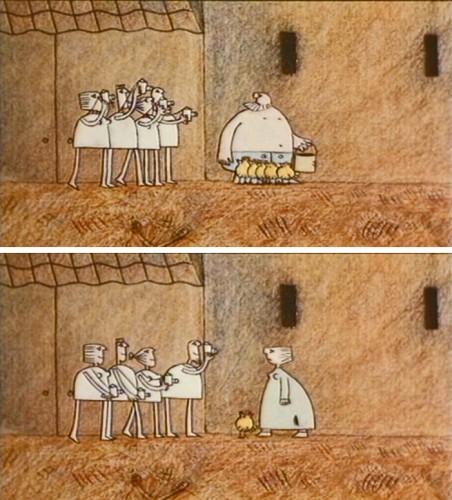

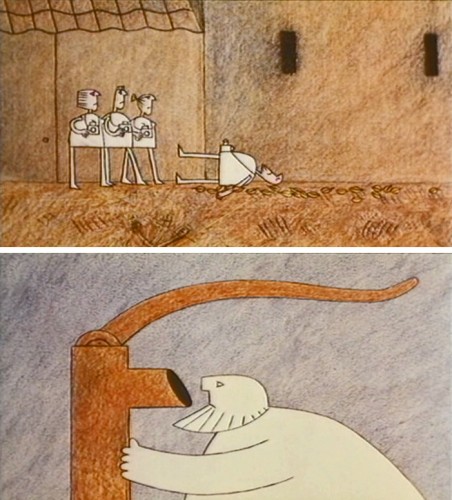

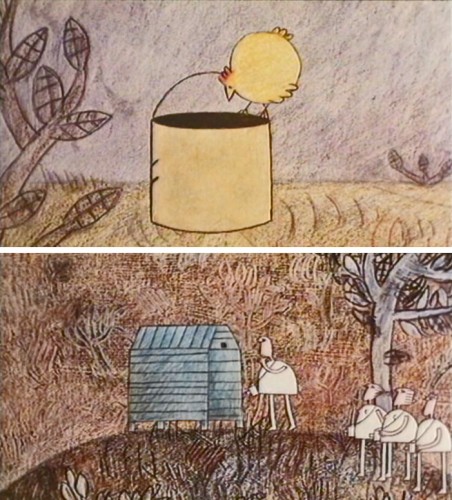

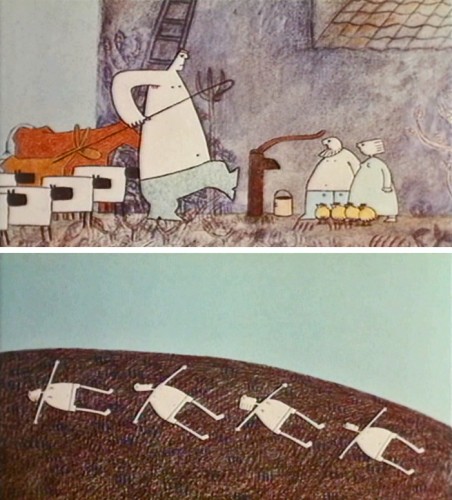

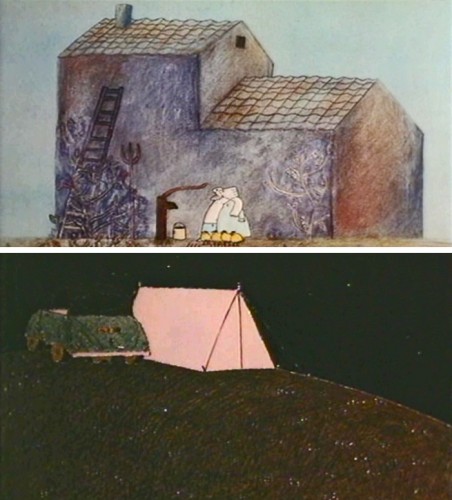

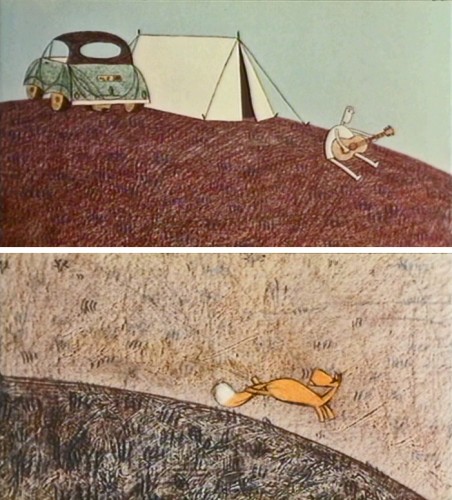

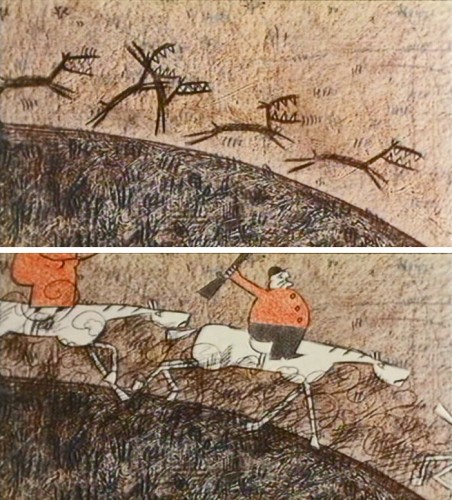

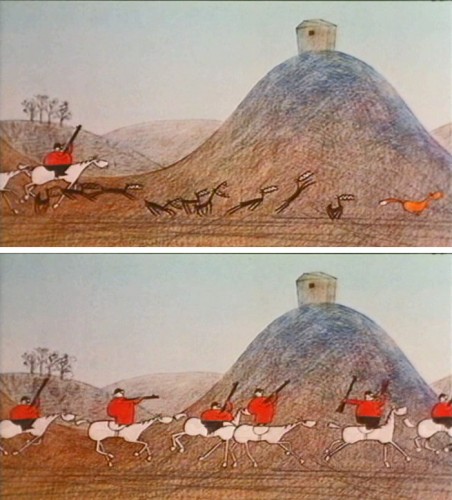

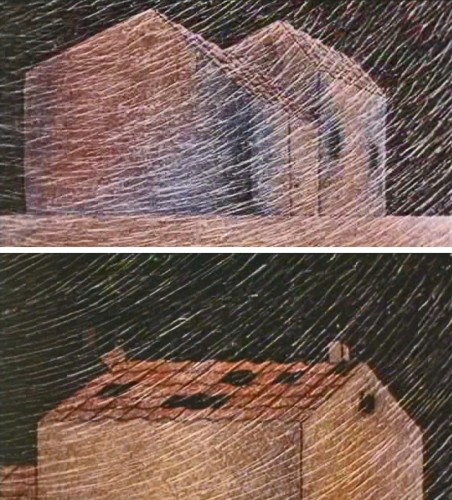

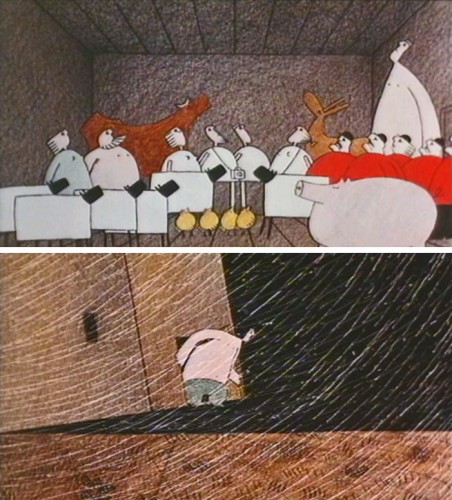

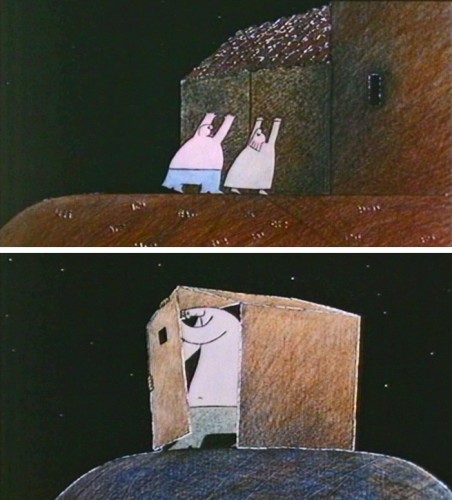

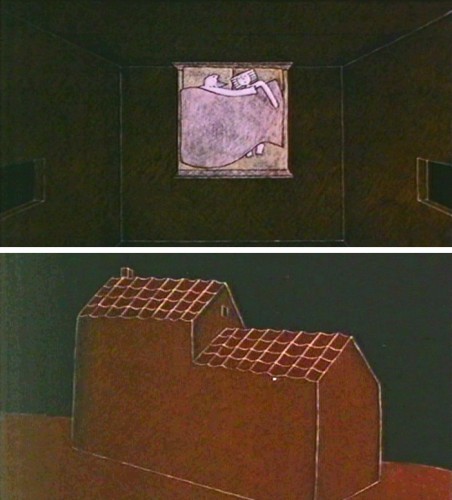

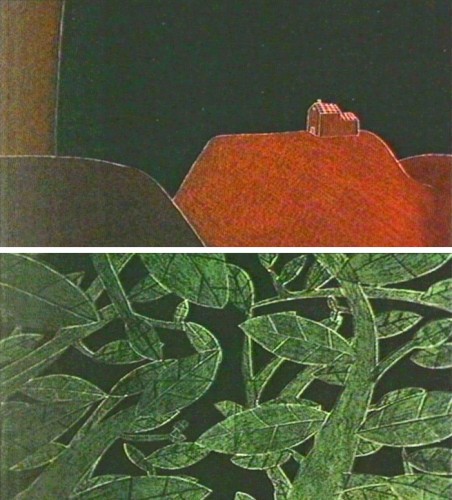

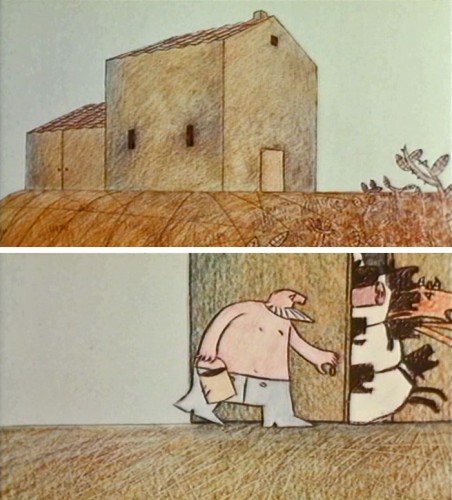

Frame Grabs &Independent Animation 07 Nov 2011 07:46 am

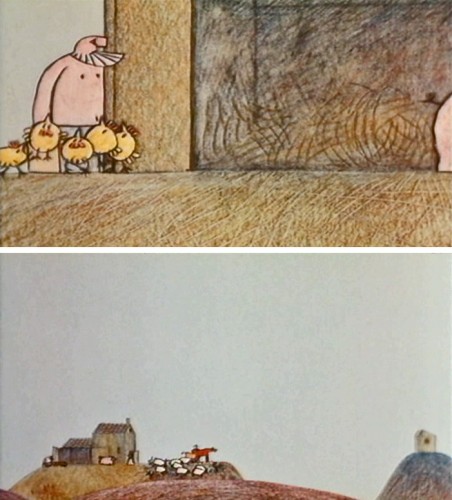

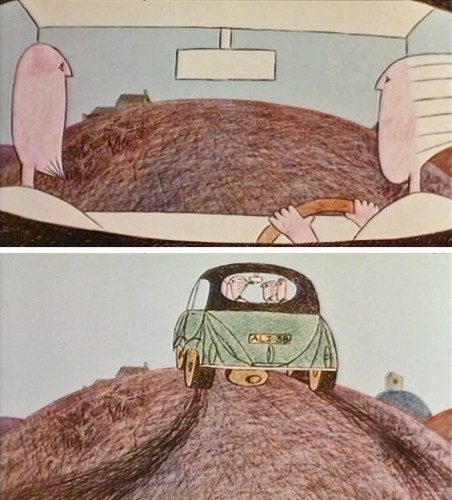

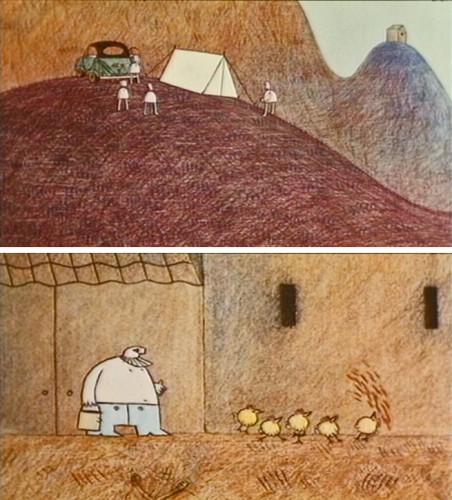

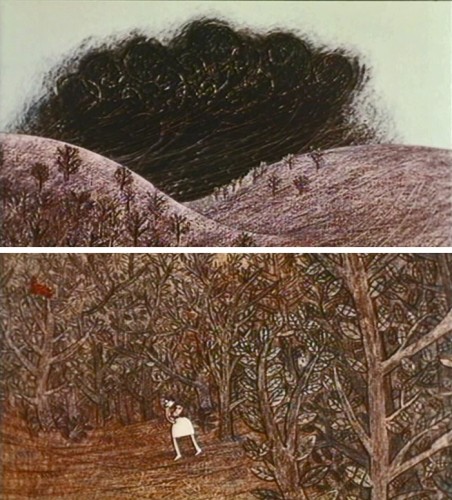

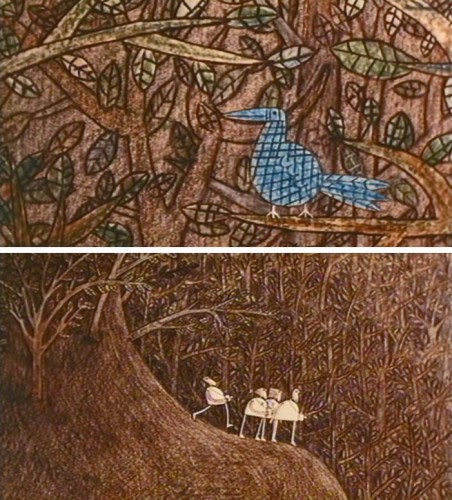

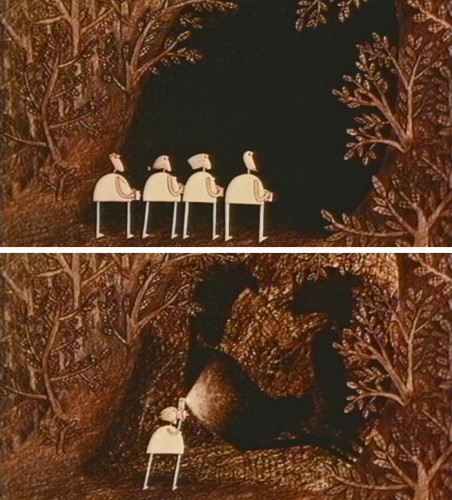

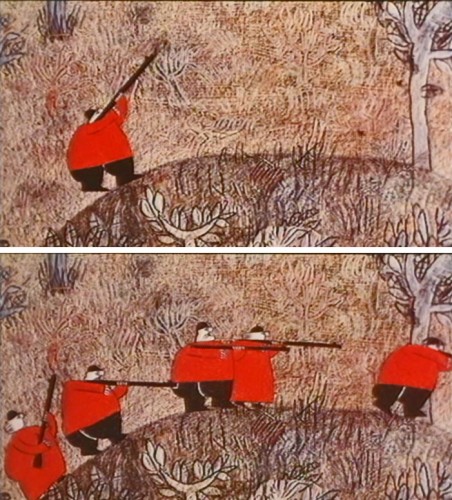

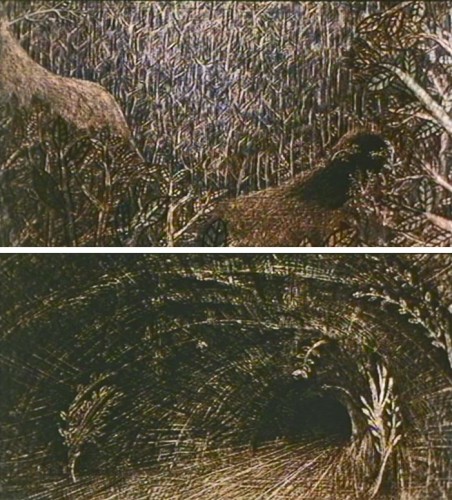

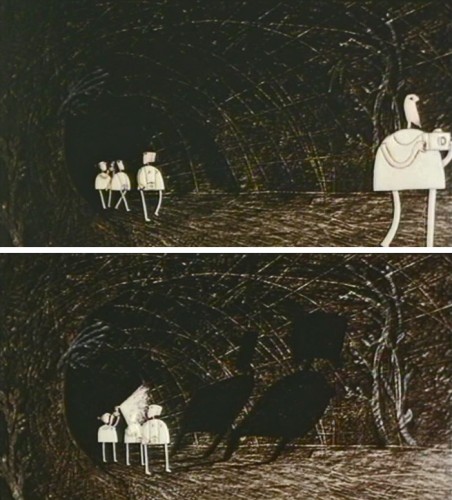

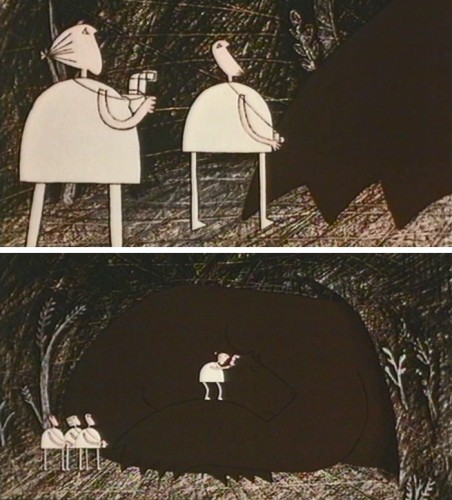

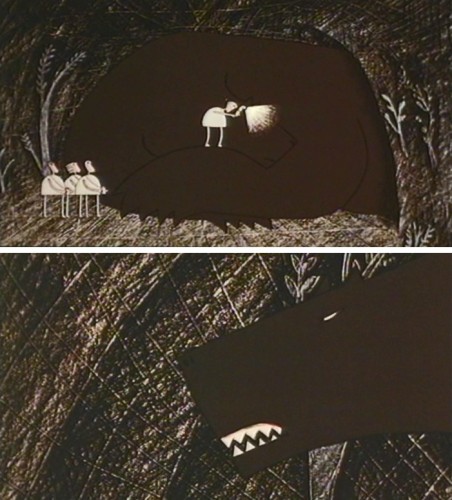

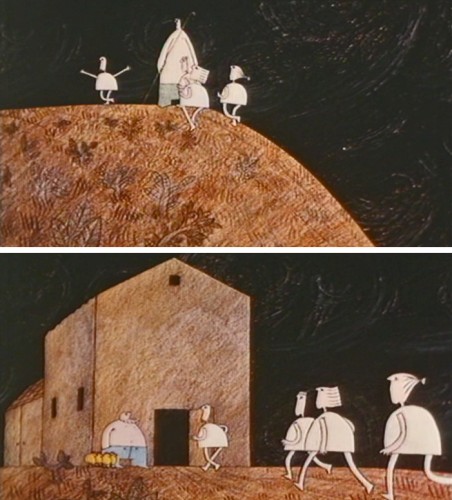

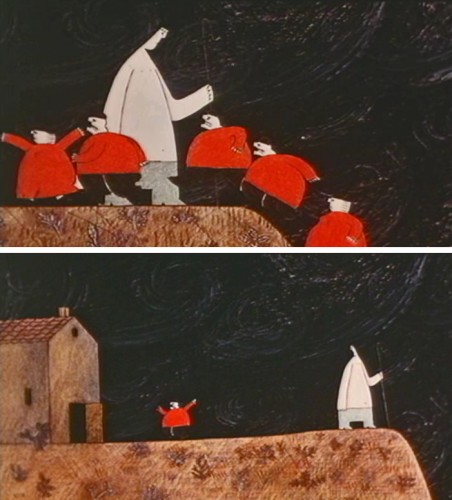

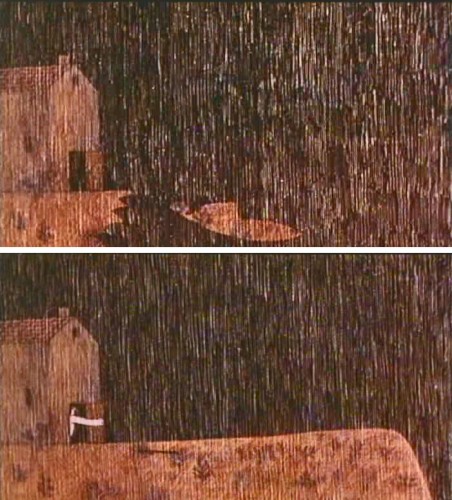

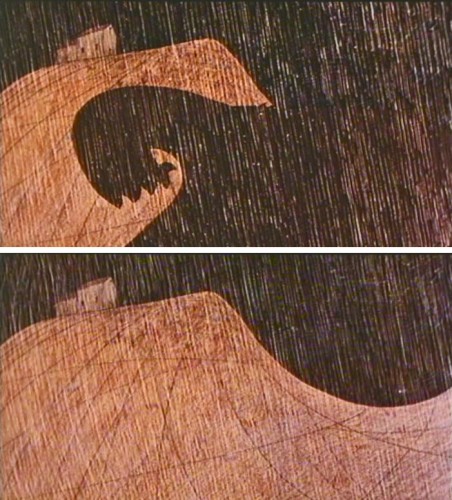

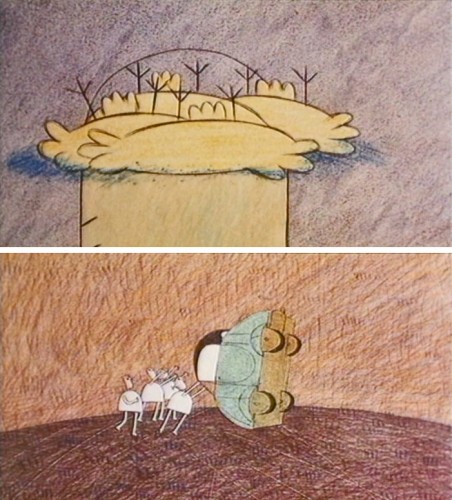

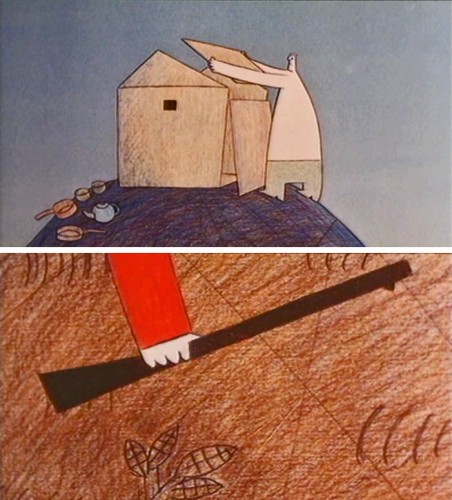

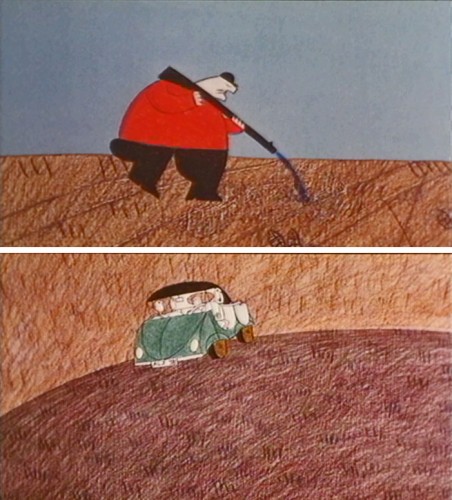

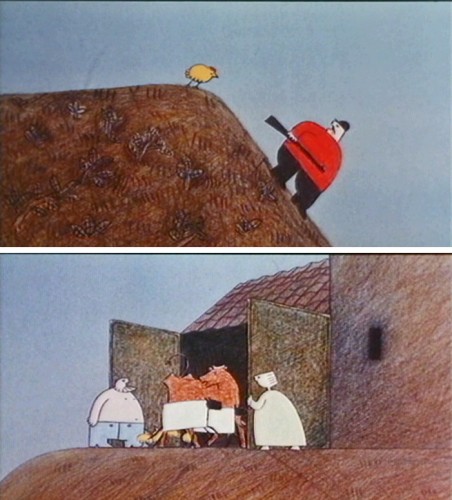

The Hill Farm – 2

- Last week I began posting frame grabs from one of my favorite short films, The Hill Farm; it was released in 1989. The film was the first significant work of a new film maker, Mark Baker. Baker went on to form a commercial production studio in London, Astley Baker Davies, Ltd. This company produced several recent television series: Peppa Pig, Ben & Holly’s Little Kingdom, The Big Knights.

Baker did two other significant short films: The Village and Jolly Roger. All three of his shorts, including The Hill Farm were nominated for Oscars. All three of them should have won the award, except that they were up against Aardman.

Here is the conclusion of the frame grab selection from The Hill Farm:

2

2

Photos &Steve Fisher 06 Nov 2011 08:26 am

All over NY

- Continuing the jump about NY, I have a stash of new pictures from my friend, Steve Fisher. These are shots from all over the city. Whether Manhattan, Queens, or Brooklyn, they’re all great photos. I hope you like them.

Twilit Buildings

1

1

Swings

13

13.

14

14.

15

15

Geese

16

16.

17

17.

18

18There’s always one malcontent.

.

Commentary 05 Nov 2011 07:07 am

Bobbing for Apples

- My studio is dead center for the Halloween Parade. That was last Monday, the beginning of the week. This is a day to get out of the area. The parade starts at 6pm, and I was out of here by 5. By then the nearest subway station was closed off, so I had to go across town (about 8 city blocks) to catch an East side train to go home. Crossing 6th Avenue, was a nightmare in that the police had blocked off the sidewalk making it hard to get into the street. Then, once across, there were hundreds of people walking in the opposite direction of me. They were coming toward the parade; I was leaving it.

The next morning there was a lot of water gathered at the foot of the stairs/entrance to my studio. It turns out at 1am, at the last minute of the parade, my superintendent had caught three female teenagers urinating at the half-hidden location outside the closed gate. He chased them away then threw bleached water to clean up after them. The water hadn’t dried in the morning.

What does this have to do with animation? The problem is that when you have your own studio you deal with so much more crap than actually doing animation. It’s the endless paperwork, phone calls, sales reps trying to sell you everything from software to paper clips to copier/scanners. It’s the balancing the books and paying the bills and still trying to get the work in shop to keep the overhead over head.

I wish I had a bit more time for the artwork. The studio doesn’t pay enough to have a lot of helpers doing some of these tasks. I think that’s why I’ve been reading about all the early days of Disney, lately. It’s fun hearing about some of the hardship he had to go through prior to making it big. For some reason those have always been the books I prefer reading.

There’s that Walter Lantz book by Joe Adamson where Lantz almost goes bankrupt and has to make a few shorts at his own expense to keep the product rolling.

There’s the Tim Susanin Walt Before Mickey book that counts every nickel and dime as Disney tries to get on solid ground only to have all his workers plot against him so that they could be the bosses.

There are a number of these books, and I love them all.

.

.

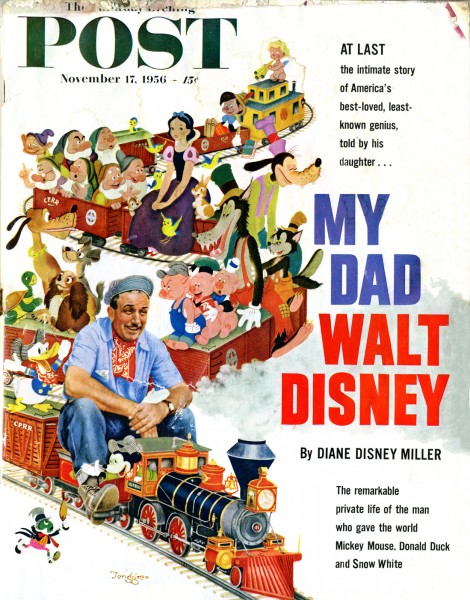

On Thursday, I’d posted a review of the 1957 biography, The Story of Walt Disney, by his daughter, Diane Disney Miller (aged 23 at the time) “as told to Pete Martin.” It’s an entertaining read if you’re interested in Uncle Walt, though I’m not so confident in the accuracy of all the history.

.

You can read the first chapter in the Saturday Evening Post edition I posted a couple of years ago. The magazine serialized some of the book prior to its publication.

.

.

- In today’s New York Times, Jeff Scher has a new animated piece on the Op Ed page. Focus is an “abstract expression of the New York marathon” (which will take place tomorrow.) Jeff brilliantly manipulates footage of the runners and the bystanders (or is it the “standers by”?) to a tightly driven two minute piece. The fine music is by the extraordinary Shay Lynch.

.

.

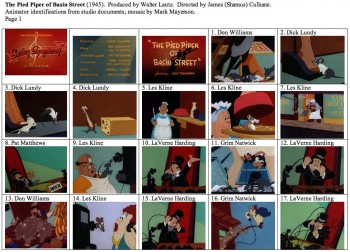

Was this the first mosaic?

Hans Perk on his site A Film LA has begun to post the animator drafts for Disney’s Ichabod and Mr. Toad. This blog is one of the great resources for animators on the web.

.

Sanek has begun taking Hans Perk’s copy of the draft and translating it into Mosaics. (I believe and assume that it was Mark Mayerson who coined the title “Mosaic” when he began doing these visual displays of the Disney drafts back in 2006. Now it’s an international word understood by all in the animation blogosphere. Sort of like the word “blogosphere.”)

.

Karl Cohen of ASIFA SF had sent me the link to an animated music video which used animated jelly beans as the medium of choice. It should have been plenty that that was labor intensive enough, but the film makers chose to combine a live actor in with the jelly beans. You can go here to see the video as well as a making-of video (which I found more interesting to watch.)

.

___________________________

- This past week, John Lasseter answered questions for readers in the NYTimes. There were either no hard ball questions, or the Times didn’t give them to Lasseter. A blah interview with questions like this:

- Q. Is it possible there will be a sequel to “Finding Nemo†someday? (G. W. German, Port Townsend, WA) One of my favorite PIXAR films is “The Incredibles,†are you going to make a sequel in the near future? If not, why? (Quinn F, Mount Vernon, NY)

A. We don’t know yet. The only reason we do a sequel at Pixar is if we come up with a great story that is as good or better than the original. So it lands on the shoulders of the director that created the original to be the seed, you might say, for these things. We may, we may not. It depends on if we come up with a great story.

I guess the director of Cars 2 thought he came up with a good story.

.

On Monday, Nov. 14th, the Museum of Modern Art in conjunction with the Motion Picture Academy (AMPAS) are presenting a program of film titles by Saul Bass. This includes a new restoration of Why Man Creates.

Go to the link to buy tickets in advance.

And speaking of Vertigo, I saw the feature film, The Artist, last night. It was a silent film done this year and about to be released by the Weinstein Company. This was a very sweet and romantic film. I’d recommend it highly.

As a silent film it had a full blown score by Ludovic Bource. This was an equally romantic pastiche of music for film. However, the highlight of the sound track was the 7-10 minutes of the score to Vertigo by the brillliant Bernard Herrmann as conducted by Elmer Bernstein. Loving this original score and having memorized it, I was jolted to hear it pop up in this new film. It was used, intact, for the climax of The Artist. Suddenly we went from a good film score to a great score. It truly showed the power of Herrmann’s work. Unfortunately, for Ludovic Bource, I spent the rest of the evening humming Bernard Herrmann’s melody. I wonder if this, in any way, disqualifies the film for nomination for the score. (You can hear the original Herrmann cue here.)

As a silent film it had a full blown score by Ludovic Bource. This was an equally romantic pastiche of music for film. However, the highlight of the sound track was the 7-10 minutes of the score to Vertigo by the brillliant Bernard Herrmann as conducted by Elmer Bernstein. Loving this original score and having memorized it, I was jolted to hear it pop up in this new film. It was used, intact, for the climax of The Artist. Suddenly we went from a good film score to a great score. It truly showed the power of Herrmann’s work. Unfortunately, for Ludovic Bource, I spent the rest of the evening humming Bernard Herrmann’s melody. I wonder if this, in any way, disqualifies the film for nomination for the score. (You can hear the original Herrmann cue here.)

Bill Peckmann &Comic Art &Illustration 04 Nov 2011 05:31 am

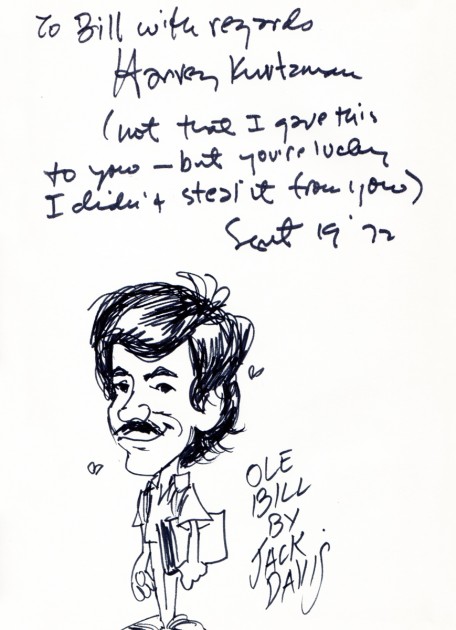

Harvey and Jack – Part 5

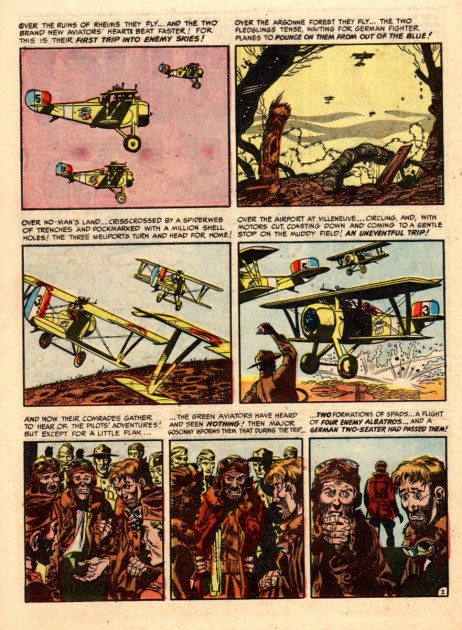

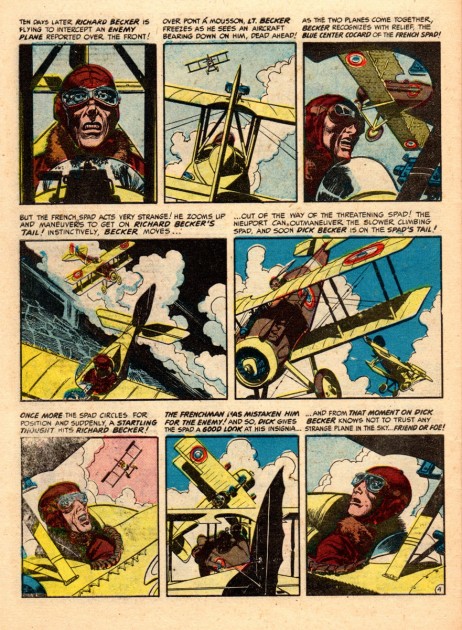

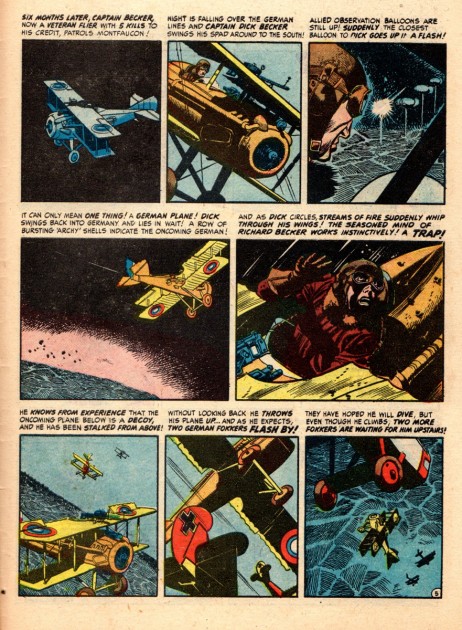

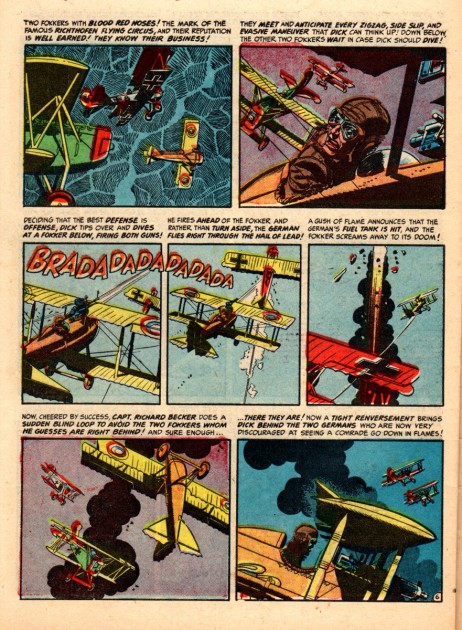

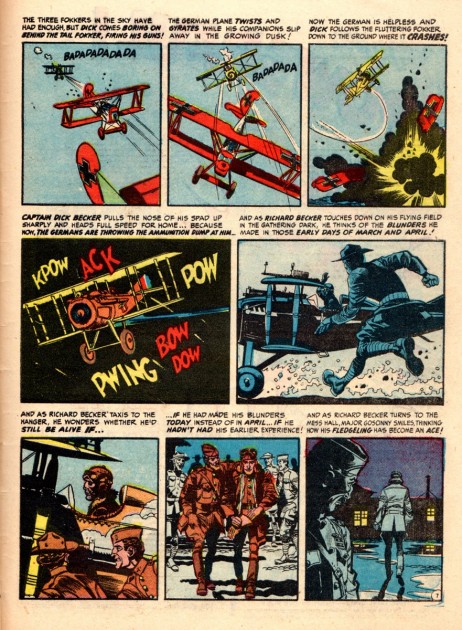

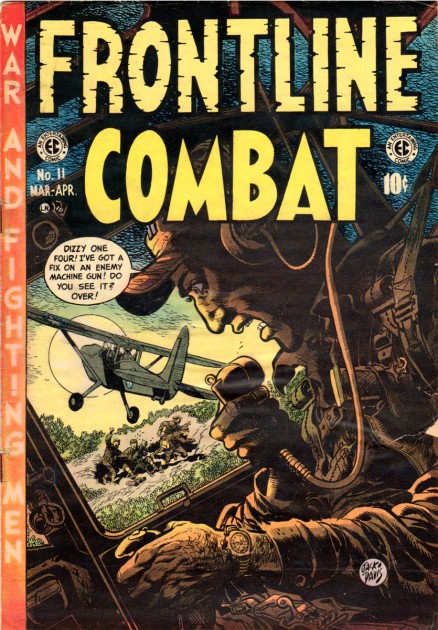

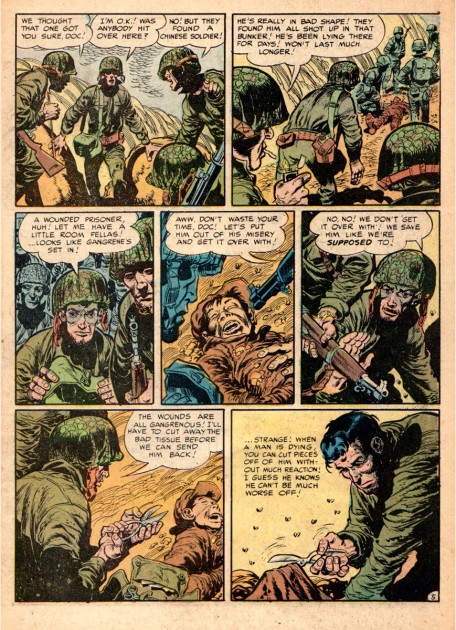

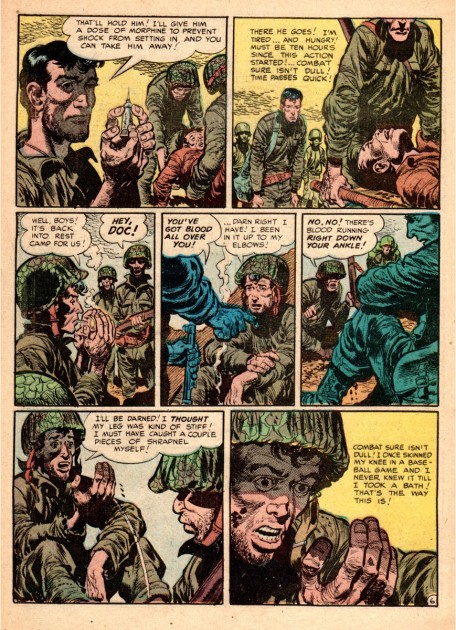

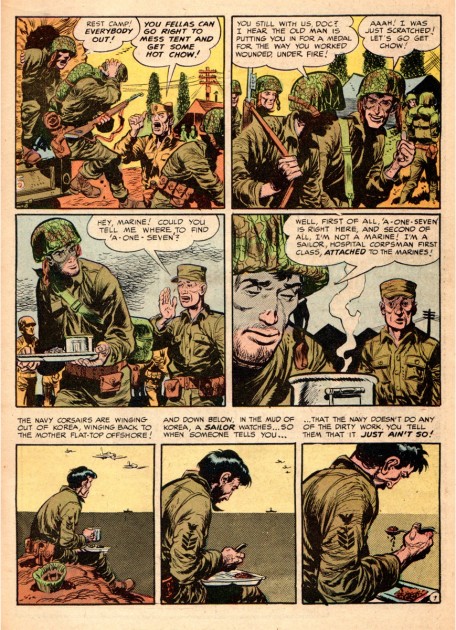

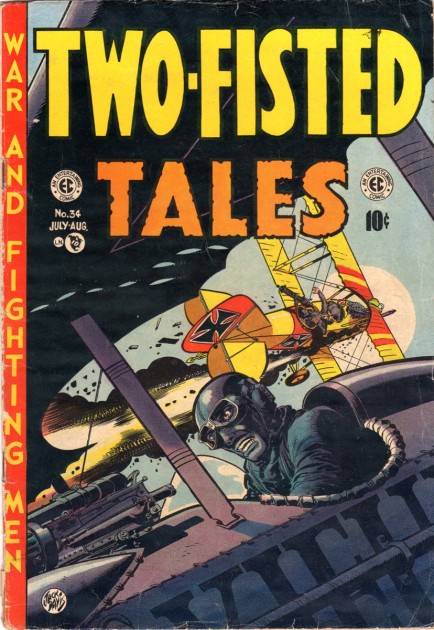

- The collaboration between Harvey Kurtzman and Jack Davis has proven to be a very fertile one.. Bill Peckmann has continued to send more material to extend the idea, and I take delight in posting it. Bill wrote the accomp;anying notes:

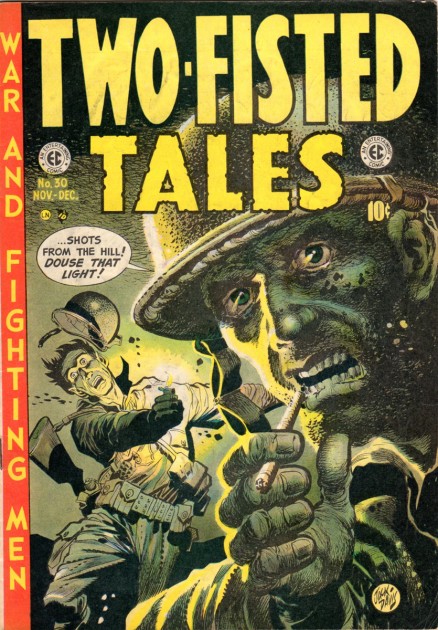

In really reaching and stretching to show more Harvey and Jack “firsts”, I’m sending you the first two covers that Jack did for Harvey’s war comics “Two-Fisted Tales” and “Frontline Combat” along with a Harvey and Jack story from each issue.

1

1Here is the cover of “Two-Fisted Tales” No. 30, 1952.

.

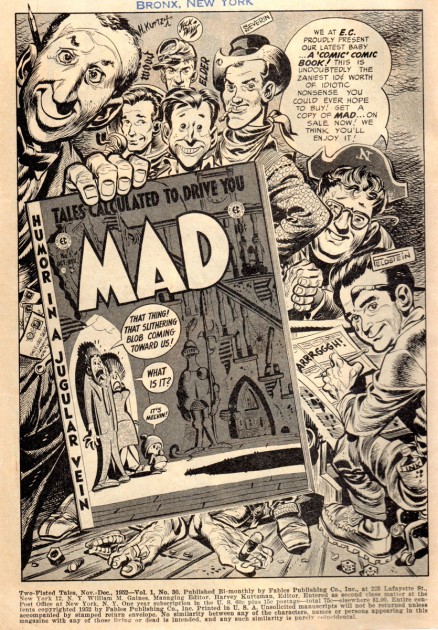

2

2This is the inside cover of “Two-Fisted”. One of the

big treats of EC Comics were their “in house” ads for

other titles. Here is the ad for MAD No.1 done by Jack.

It was great the way EC put faces to your favorite artists.

I’d say the roots for Jack’s future TV GUIDE covers are right here.

.

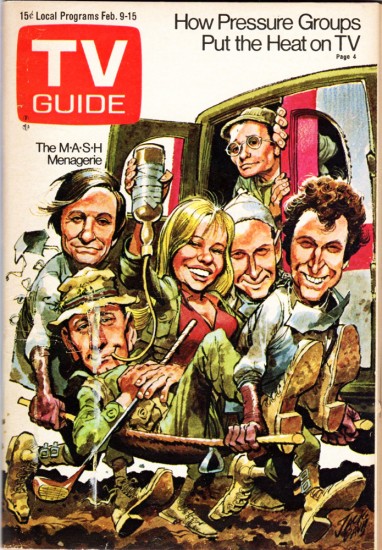

3

3Skipping ahead twenty-two years, (a break in the action)

I’m inserting a Jack Davis TV GUIDE cover from 1974.

(It also has a Korean War theme.)

.

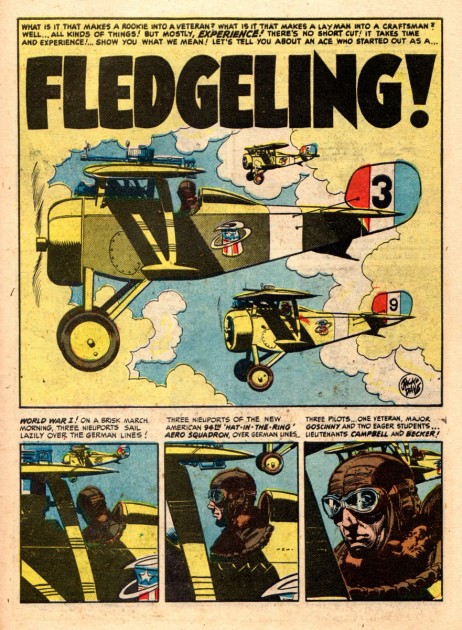

4

4Harvey and Jack’s story from No. 30.

(They certainly gave the great aviation cartoonist,

Alex Toth a run for his money!)

.

5

5.

6

6.

7

7.

8

8.

9

9.

10

10.

11

11Jack’s first “Frontline Combat” cover, No. 11, 1953.

.

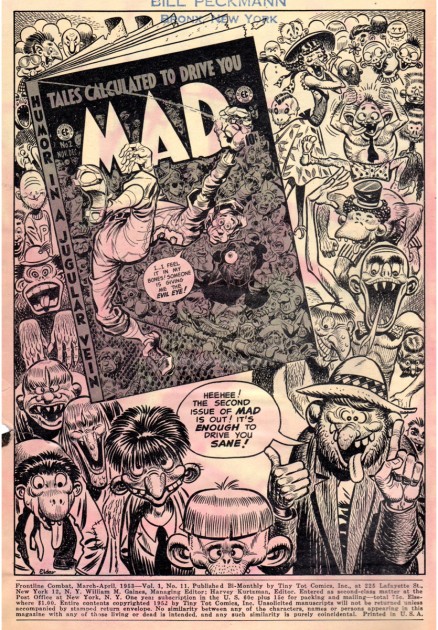

12

12Inside front cover of “FC”. It’s an ad for MAD No. 2 done by EC great, Bill Elder.

(Sorry about the front cover colors bleeding through.)

.

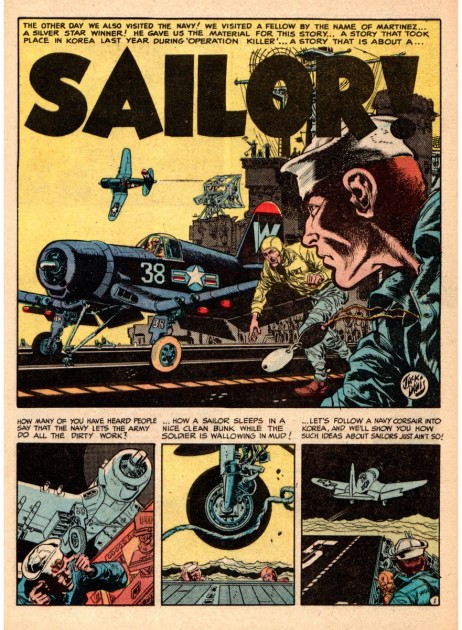

13

13“Sailor!”, Harvey and Jack’s collaboration for “FC” No. 11.

It shows the horrors of war (as much as you could in a

comic book back then), the realism that was to come later

in films like “Saving Private Ryan”.

.

14

14.

15

15.

16

16.

17

17.

18

18.

19

19.

20

20The colors, excitement and dynamics of the cover are just terrific.

Jack makes it look so easy.

.

21

21Back in the days before comic book reprints, fans had to do with

whatever copies they had collected. One way to keep comics from

getting battered and tattered was to have them bound in volumes.

Working with Harvey and Jack on animated projects back in the

early 70′s, I was very fortunate and they were very kind to put their

John Hancocks in my bound volume of “Frontline Combat”.

Many thanks to Bill Peckmann for sharing the material and putting it all together.

.

Books &Commentary 03 Nov 2011 06:58 am

Dad’s Daughter’s book – an Overdue Review

- I haven’t read the book, The Story of Walt Disney by Diane Disney Miller “as told to Pete Martin“, since it was originally published in 1957. Actually, I probably read the version that was serialized in the Saturday Evening Post in November 1956; then I most likely asked for a copy of the book for a Christmas present and read it then. After all, I was only 11.

- I haven’t read the book, The Story of Walt Disney by Diane Disney Miller “as told to Pete Martin“, since it was originally published in 1957. Actually, I probably read the version that was serialized in the Saturday Evening Post in November 1956; then I most likely asked for a copy of the book for a Christmas present and read it then. After all, I was only 11.

I remember being grabbed by the book and hooked for all time on animation. Two years later, the Bob Thomas Art of Animation would lock it up for me.

The Story of Walt Disney is an odd book to review. I wonder how much actual research went into the writing. Was it enough to have the source, Walt Disney, reveal his story verbally to Diane and Pete Miller? The voice undoubtedly comes through. The book comes off as one for youngsters; there’s an innocence in the writing that Pete Miller obviously got across. He did the writing; the book is labelled “by Diane Disney Miller as told to Pete Martin.” Martin was a writer for The Saturday Evening Post, where the book was serialized prior to its publication. Miller was also known for having collaborated with Bing Crosby on a book of memoirs before working on this Disney book.

Since this book is essentially out of the mouth of Walt, we have to pay attention to some of the stories being told. What was told and what was skipped?

Since this book is essentially out of the mouth of Walt, we have to pay attention to some of the stories being told. What was told and what was skipped?

There’s quite a bit more than usual about the Red Cross service Disney did at the end of WWI.

The “Alice” series is called by the title “Alice in Cartoonland.” Unfortunately, the Disney brothers called the series the “Alice Comedies.” Even though their first short was known as “Alice’s Wonderland,” they didn’t refer to the others with any reference to Lewis Carroll’s work. That may well have been the demand of the distributor Charles Mintz even though the Disneys may have thought of the series as “Alice in Cartoonland.” Obviously, Walt referred to it as that title in telling this story.

There’s a mention of Ub Iwerks when Walt asked him to move out to LA, but there’s no mention of his name when Iwerks left Disney to open his own studio under the assistance of Pat Powers. There’s some detail in the chapter about Snow White, but barely a mention of Pinocchio or Bambi. Lots to tell about Fantasia and a bit more about Dumbo. No mention

of Song of the South, Fun and Fancy Free or So Dear to My Heart, but Cinderella gets attention as do the documentary nature films. There’s an odd telling of the Disney strike in this book, and the suggestion of how the South American trip came about. In truth, the book becomes more about the juggling of money once Snow White goes into production and less about the actual films. There’s plenty of detail about going public with the stock options, and there’s a lot of detail about the government work done during WWII.

of Song of the South, Fun and Fancy Free or So Dear to My Heart, but Cinderella gets attention as do the documentary nature films. There’s an odd telling of the Disney strike in this book, and the suggestion of how the South American trip came about. In truth, the book becomes more about the juggling of money once Snow White goes into production and less about the actual films. There’s plenty of detail about going public with the stock options, and there’s a lot of detail about the government work done during WWII.

An interesting sentence comes at the beginning of the book when we read about the farm in Marcelline in hs childhood. “He can still draw a mental – or rather a sentimental – map of that whole community exactly as it was then.” This is a rare sentence by Diane commenting on her father’s recollections, and one wishes there were more like it. The last chapter of the book offers a bit more of this when Diane decides to tell a bit more about her father away from the office. What he likes to eat, how he acts, etc. There’s a lot of personality in this chapter.

One wonders how useful this book is for actual animation historians. Mike Barrier and John Canemaker have obviously read it, but do they trust the material? And why shouldn’t they, especially if there’s a second source for any of it. The story as a whole is very readable, and one rolls along easily in the telling of the tale. It’s especially entertaining. Obviously, the goal was to make the story for the largest possible audience, so details of the films were less interesting than the struggles of the imaginative entrepreneur.

You know that “dad” enjoyed telling his daughter of all his accomplishments. So this is his version, and it’s interesting how it comes out filtered through the voices of Diane and Pete Miller. Diane’s pride in the studio is certainly as great as Walt’s.

You know that “dad” enjoyed telling his daughter of all his accomplishments. So this is his version, and it’s interesting how it comes out filtered through the voices of Diane and Pete Miller. Diane’s pride in the studio is certainly as great as Walt’s.

- “Father did the outlines of the drawings. The other two filled them in. Gradually Father gave them bigger assignments, until they were doing whole scenes themselves. Even then Father insisted upon a distinctive Disney style of drawing and photography, and he trained his two helpers to do things his way.

.

“They weren’t the only ones who have conformed to the Disney style. Almost all animated techniques since have conformed to the basic formulas that emerged from that primitive studio. Although they may vary in spirit, or another cartoon maker’s conception of what gives greater pictorial impact may differ from Father’s, they all owe a debt that goes back to the inventiveness and experimentation that went on in the back room of that converted real estate office.”

That sense of pride is understandable.

The Story of Walt Disney is actually a good read if you have a copy and haven’t seen it in years. Or you might be able to locate a copy in the library. Take the time; it moves quickly and is fun.

Animation &Animation Artifacts &Disney 02 Nov 2011 07:54 am

Mickey and the Brooms – 1

- I’ve got a very long scene to share with you, and I’m busy. There are over 500 drawings involved – many are the shadows of Mickey’s chopping of the brooms. So this scene is going to go up in many parts. I also have the exposure sheets (which are complicated) and I’ll post those when I reach a good breaking point.

The scene is beautifully animated by Riley Thompson with assistant animation from Harvey Toombs. Here’s Mickey entering the scene and skidding to a stop outside the door.

1

1  2

2

__________________________

The following QT utilizes all the drawings displayed above.

as exposed on the X-sheets. Most are on ones. Moving

into and out of short holds drawings are on twos.

__________________________

Art Art 01 Nov 2011 05:37 am

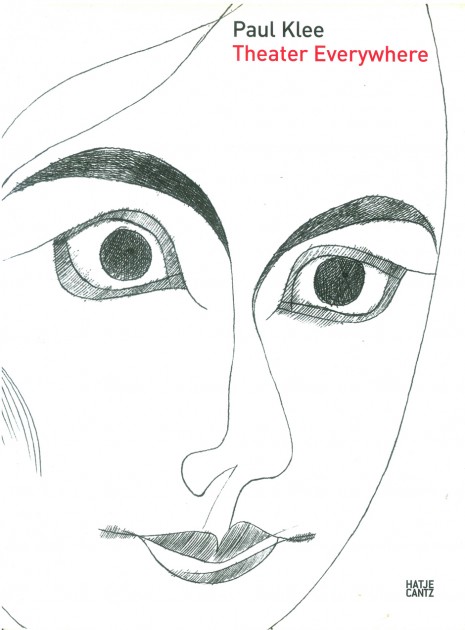

Klee – Theater Everywhere

- If there is any artist I would call my favorite, it would have to be Paul Klee. I must have at least a dozen art books on the man’s work, and I can’t get enough. My dear Heidi gifted me, recently, with a treasure of a book focusing on the artist’s love of theater and his representation of theatrical pieces in his art. We know that he was a theatrical man, having been taught to play the violin from an earlier age than when he’d started to paint. He was a virtuoso who performed on the instrument regularly. He couldn’t get enough of performance art in his life, and that’s well obvious from the drawings and paintings in this book.

One of my favorite periods at the Hubley studio was in the preparation for the CTW series, Letterman. I did a lot of library research for John Hubley on Paul Klee. The TV series grew out of Klee’s comic art, and I went to a lot of private libraries searching for elements that I thought John could use. This book would have been enormously helpful back then.

I intend to pull from Klee – Theater Everywhere a few times to post on this blog some of the great pieces in the book. Here are a few.

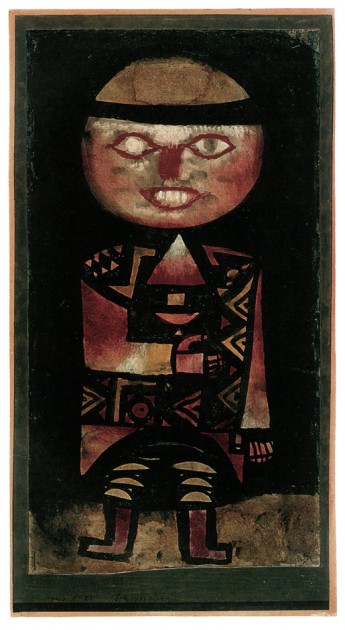

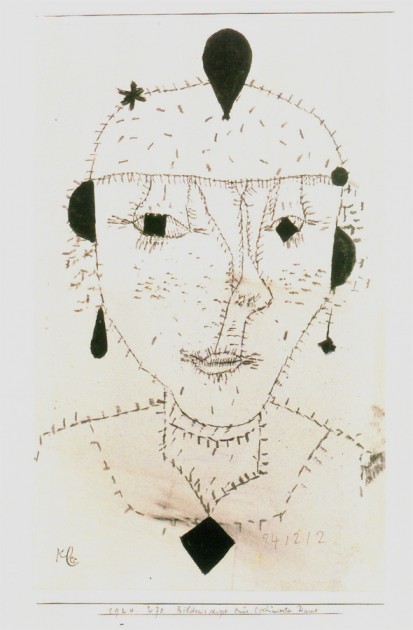

The book’s cover – Semitic Beauty

.

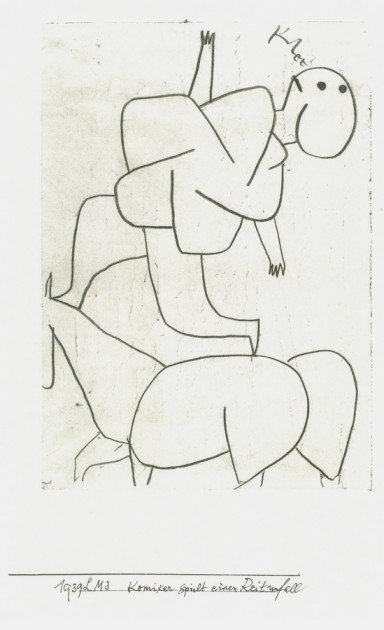

1

1Comic Actor Acting Out A Riding Accident

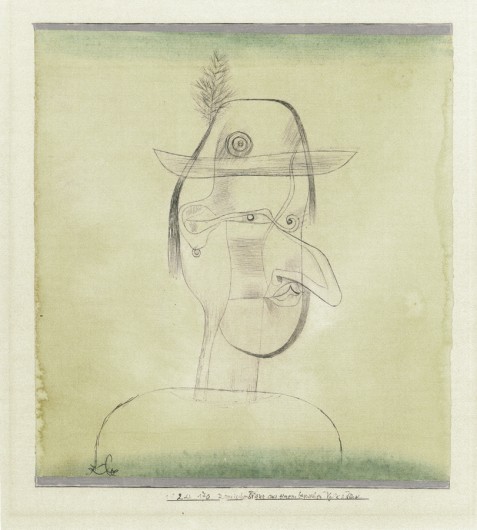

.

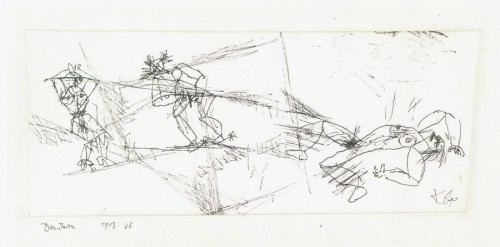

2

2Actor

.

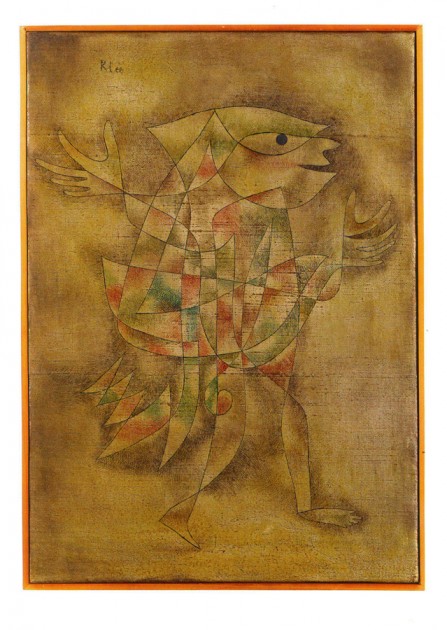

3

3Comic Character From A Bavarian Folk-Play

.

Dance of the Red Skirts

.

5

5Fool In A Trance

.

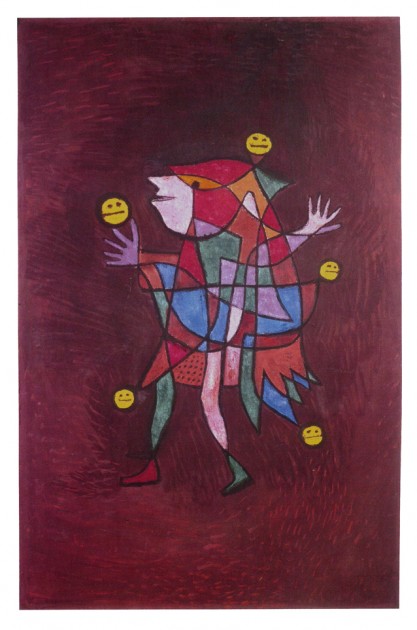

6

6Figurine – the Fool

.

7

7Portrait Sketch of a Costumed Lady

.

8

8Don Juan

.

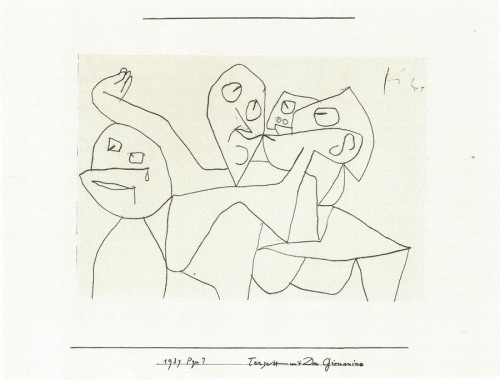

9

9Trio With Don Giovanni

.

10

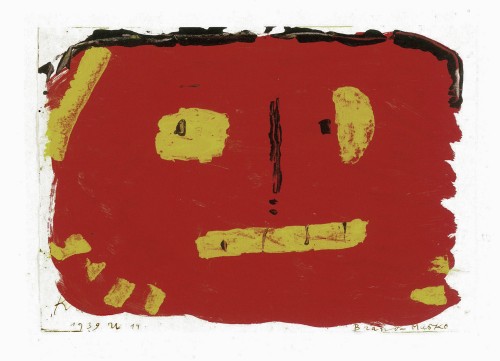

10Fire Mask

.

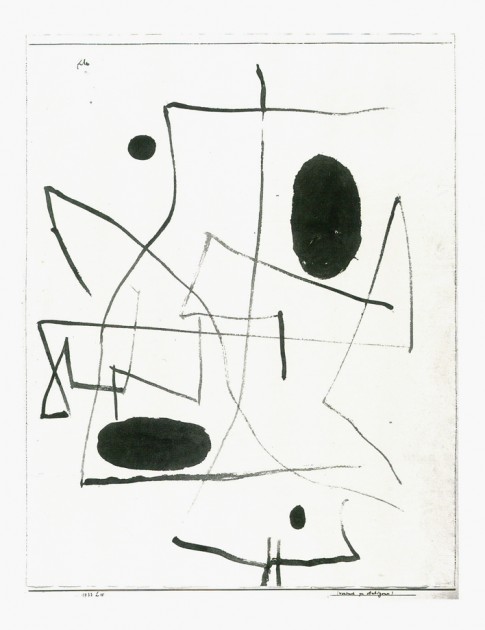

11

11Trial for Antigone

.

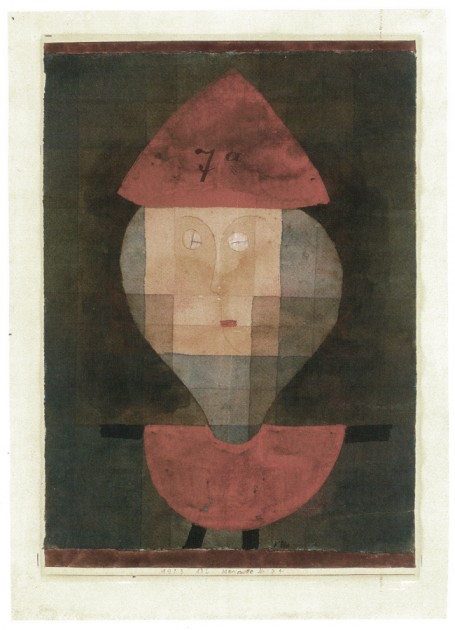

12

12Puppet number 7A

.

Group Portrait of Hand Puppets

.