Books &Commentary 10 Nov 2011 06:45 am

Lutz

- This week, I posted a review of E.G. Lutz’ book, Animated Cartoons: How They Are Made, Their Origin and Development, and I commented that I have had this curiosity about who E.G.Lutz actually was. A quick Google search for biographical information comes up with nothing other than the Amazon listing of his books for sale and the references to him in other animation books.

It was a bit of a surprise to me to find that his singular animation book, published in 1920, is definitely not his best selling book. That would be Drawing made easy; A step by step guide to drawing for young artists. There are also another half dozen books he’s either written or illustrated.

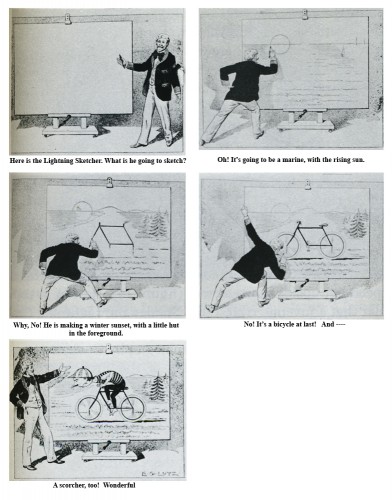

I decided, then, to look in all of the books I own. The best place to start was with Donald Crafton‘s book, Before Mickey. Sure enough, there was an illustration by Lutz that was done in 1897. It depicted the “Lightning sketcher.” These were the artists who appeared on stage in Vaudeville theaters sketching an image at “lightning” speed. Georges Méliès enjoyed doing this for a while, and J. Stuart Blackton put it on film. Lutz illustrated such an artist.

I’ve had to do a little retouching in photoshop to get

this image to read well. I retyped all the text there.

Crafton later quotes the Lutz book:

- The first book devoted solely to the craft was Animated Cartoons; How They are Made, their Origin and Development by former caricaturist Edwin G. Lutz. This book became the vulgate of modern industrial animation, canonizing the major studios’ practices. Its guiding philosophy was embodied in the statement that “of all the talents required by anyone going into this branch of art, none is so important as that of the skill to plan the work so that the lowest possible number of drawings need be made for any particular scenario.” Lutz illustrated the book with his own rather quaint drawings. He described peg registration, in-betweening, speech balloons, and studio organization, but curiously his description of cels was limited to their use as static overlays.

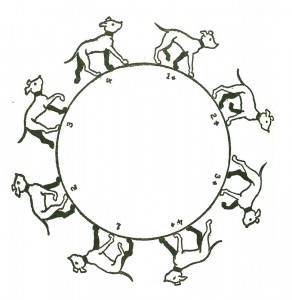

- Lutz’s book was a fountain of common-sense advice, such as limiting dialog so that films could be sold in foreign countries. Among its most important contributions were the detailed instructions for drawing perspective runs and other kinetic effects, which would grow increasingly visible throughout the 1920s, especially when combined with mobile and cycled backgrounds. Cycling, supposedly invented by Nolan, consisted of a sequence of eight drawings planned to match at the end of a cycle by making the first and eighth drawings identical. This effect may be seen in practically any 1920s studio production, but Paul Terry seemed to especially love it, With these and all the Other techniques explained in detail, almost anyone with the ambition could begin making animated cartoons. Of these neophytes, certainly the most ambitious reader of Lutz was Walt Disney of Kansas City—who, because he could not afford to buy it, checked the book out of the public library.

This, of course, is the story of how Walt Disney pored over the book slavishly to find out the tricks of the trade. Mike Barrier in his book, The Animated Man, describes this well:

- (Disney) was essentially self-taught as an animator; he wrote to an admirer many years later, “I gained my first information on animation from a book . . . which I procured from the Kansas City Public Library.” . . . According to its copyright page, Lutz’s book was published in New York in February 1920, the same month Disney joined Kansas City Film Ad, so he must have read it very soon after it was added to the library’s collection. He said of the book in 1956: “Now, it was not very profound; it was just something the guy had put together to make a buck. But, still, there are ideas in there.”

- As elementary as the Lutz book was, it still offered a vision of a kind of animation far more advanced than the Film Ad cutouts. Lutz wrote at a time when animators commonly worked entirely on paper. They made a series of drawings, each different from the one before, that were traced in ink and photographed in sequence to produce the same illusion of movement that Film Ad achieved by manipulating cutouts under the camera. Lutz advocated the use of celluloid sheets to cut down on the animator’s labor—the parts of a character’s body that were not moving could be traced on a single sheet and placed over the paper drawings of the moving parts. Such an expedient (and Lutz recommended others) would have resonated with Disney, who had been so impressed by commercial art’s shortcuts when he worked for Pesmen-Rubin.

Barrier also quotes Hugh Harman as saying, “Our only study was the Lutz book . . . that, plus Paul Terry’s films.”

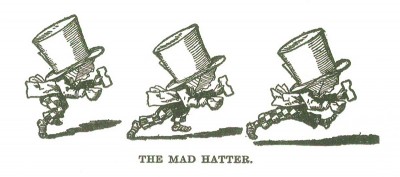

This is one of the illustrations Lutz did for his book,

The Animated Cartoon.

Donald Crafton talks extensively of the management theory of Frederick W. Taylor. Taylor basically stated that lower paid jobs should be done by lower paid employees on what would basically become an assembly line. This was adapted by J.R. Bray and Thomas Ince. The Inbetweener was born. Crafton writes:

- In his 1920 manual, Lutz was still promulgating the taylorist philosophy—for example, when he described the tracers’ function in language echoing Bray. “It can be seen from this way of working in the division of labor between the animator and his helper that the actual toil of repeating monotonous details falls upon the tracer. The animator does the first planning and that part of the subsequent work requiring artistic ability.

Initially, Disney rejected this theory. This was something that Ub Iwerks brought to the studio after traveling from Kansas City to LA. We see this in Leslie Iwerks & John Kenworthy‘s book, The Hand Behind the Mouse:

- Ub brought the studio renewed energy and new techniques. Abandoning the stiff and rudimentary methods Or animation he had previously learned, Ub would begin to evolve bis own straight-ahead style of drawing, which did not rely on model sheets or extremes. A key aspect of the Lutz orthodoxy was pose-to-pose animation, in which, for any action, a character was drawn in its starting and ending positions (or “extremes”) and intermediate poses were filled in later. Model sheets were used to trace over the original figure, allowing the animator to simply alter the parts of the body that needed variation. Ub instead professed a new method. He felt he could coax more expressive feeling from a drawing if he used model sheets as rough guides rather than being chained to them. By trusting in his own creativity and sense of movement, he threw out all structure to make way for his own free-flowing impulses.

- Russell Merritt and J. B. Kaufman in Walt in Wonderland assert that “If Iwerks had made no other contribution to the Studio, he would deserve to be remembered for this one. It marked the beginning of the smooth, flowing ‘Disney style’ of animation; and one can see it developing, slowly but surely, as the Alice series progresses.”

We also know that one of the sore points between Disney and Iwerks, which helped cause Iwerks to leave the studio, was that Disney tried to force Iwerks to leave inbetweens for others to follow. This would get more animation out of Iwerks, who already had been the animator with the greatest speed. Ultimately, Disney fell back on what he’d learned from Lutz.

This is one of the illustrations Lutz did for his book,

The Animated Cartoon.

_________________

So, in the end, all this shows is that the Lutz book had a profound effect on animation in the developing 1920s. It also shows that Lutz did a lot of thinking about not only the process of how to make animated films and the technology available at the time of publication, but he thought of the methodology within a studio churning out many films.

We know from that initial “Lightning Sketch” illustration that Lutz was an artist. We also have to assume that he worked within an animation studio for some time to have been so thoroughly informed that he was able to describe the most meticulous details in the process of making films. Because he so completely details the workings of the camera (he also wrote a book in 1927 entitled The Motion Picture Cameraman) one would assume he must have spent some time actually shooting animation. I would guess that he started in that position, then moved into actually creating the art, as did Rudy Ising in the start of his career. It’s doubtful some producer wouldn’t use his artistic abilities in creating the animation.

This is one of the illustrations Lutz did for his book,

The Animated Cartoon.

However, this is all speculation. Perhaps he just had a strong interest and was given the authority to sit and watch within a studio. Of course, that would lead one to believe that the studio that allowed him access would have been promoted within the book. Yet. there is no studio mentioned, hence I’m led to believe that he had to have worked within a studio for some time.

I haven’t gone much farther than the books in my studio or the information on the Web. In the end, I don’t know a heck of a lot more than I started out with. I do know that Lutz’ animation book was the most important he’d written. It affected an entire industry and changed the way the process was done in the all important formative years of the studio system.

If anyone has more biographical information on Lutz, please don’t hesitate to leave it. I’d like to know more and will keep on looking.

on 10 Nov 2011 at 4:22 pm 1.GG said …

Michael,

In addition to the “The Motion Picture Cameraman” Lutz wrote other books on pictorial composition and practical drawing. In Cameraman he gets into stop-motion (“one turn, one picture”), time lapse, animated trick effects, even developing, printing, and splicing. So, in a way, by describing a wide range of skills he was undermining Taylorism’s mantra of specialization.

So, I think Crafton may be coming down too hard on Lutz. Henry Ford was the master architect of industrialism. I was only a matter of time before the business of the animation studio would marginalize the straight-ahead approach.

When I began looking for books on how to animate in the late 60s (it wasn’t generally taught in schools), I found only three: Preston Blair of course, a Kodak pamphlet on titling, and Lutz. Of course, now there’s a new crop every year.

GG

on 10 Nov 2011 at 4:47 pm 2.The Gee said …

I appreciate the information on Lutz. To be quite frank, I can’t place him based on name or his style or the drawings you’ve shown. So, it is nice to find out anything about him.

“Lutz continues for six pages telling us how circular movements

provide gales of laughter for the audience. He just about

convinced me. I’ll be keeping my eyes open in the future.â€

You wrote that in the prior post on the book, Michael.

I know you are joking but the circular movements in animation– to a lesser extent and in slapsticky film comedy– led to great foley sounds.

I know in a basic way the circular movements he seems to refer to are a bunch of variations on easy visual gags, and more often than not it is animating emphasizing curves and can involve cheats, like zip/speed lines, but, dang, the sounds that go along with them add a lot of punch to the gags.

on 09 Jan 2012 at 12:21 am 3.Martin said …

Hi, if you check openlibrary.org you will see that Lutz published at least 17 books, including texts on art anatomy, etching and engraving, water-color, oil panting, pen drawing, pictorial composition, memory drawing, etc. I am sure he must have been a good artist (though not great, judging by his drawings). What it’s certain, is that he had knowledge of every aspect of the artistic representation. It’s a shame there’s not any other information available.