Animation Artifacts &Commentary 03 Mar 2009 09:39 am

Dope Sheets

Kayvon Darabi-Fard wrote the following letter to me:

THE DOPE SHEET!!!

THE DOPE SHEET!!!

I’m a student, of animation in the UK seeking the answer to the neglect of the dope sheet. No matter how hard I try I can’t seem to find a good reason as to why my classmates and production teams refuse to use the things.

It’s not mandatory for us to use the dope sheet, but its seriously being ignored to the extent, some directors think its just time wasting or some kind of magical adventure only the technically minded pursue.

At the college I’m studying at, we’re all broken off into production teams of around 5 people a team to produce a 2 minute short. I went round and had a look at what everyone was doing. Out of 11 teams, only one director was using the dope sheet system defined in Richard Williams Survival Kit, while the other directors and animators were either creating their own systems and methods, or just ‘doing it’.

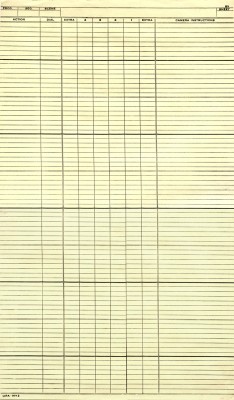

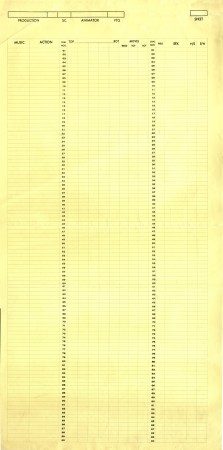

I was looking at the Steamboat Willie dope sheets you posted a few years ago. _____________X-sheet from UPA NY circa 1956

Even with music there’s always a use there. All

I need to do is convince the other 150 animators and directors that it’s not a lost cause.

After I found the one director who had an actual system (according to RW’s), I found that he was using the dope sheet you use for your studio, tailored with the 400 frames on the one page.

After I found the one director who had an actual system (according to RW’s), I found that he was using the dope sheet you use for your studio, tailored with the 400 frames on the one page.

Seriously, Do we change the dope sheet to ‘appeal’ to the new age of animators, or just crack the whip?

How would you go about teaching the dope sheet in education, and in the Sporn studio? What’s the system, and what are your views on the argument in keeping it alive?

I know there’s a war even with it becoming digital in things like Toon Boom and other CG applications, but what’s your opinions when it comes to training and producing the work within 2D traditional animation?

My answer is that, YES, I do believe in “Dope Sheets” (or as they’re known in the US, “Exposure Sheets” or “X Sheets.”)

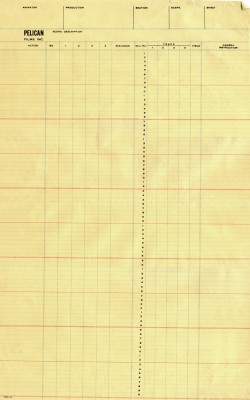

Pelican NY circa 1960

Because I was trained in using the X-sheet and

took a great interest in the differences these forms took from studio to studio, I amassed a collection of about 50 different sheets from varying studios. When I started my own studio, I took every element I thought key or helpful and put them all together on my studio’s sheets.

They were all designed, (I’m talking visually) more for the camera operator than for anyone else, but the usefulness of these sheets is enormous. A large amount of information can be placed on these sheets, and the more sophisticated animator created artpieces out of these sheets.

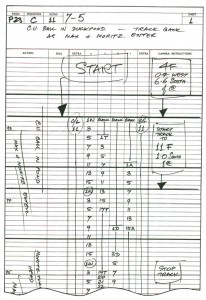

The 400 fr sheet, you mentioned was a composite I put together from my standard X-sheet. An exposure sheet should have 80 frames per page. The 400 page sheet acted similarly to bar sheets for me, as a director, more than anything else. It gave me an overview of a larger bit of the track so I could plan the cutting of the picture.

You see, when you get used to reading X-sheets, you see them as time. You don’t see the lines, you see seconds and footage, instantaneously. As an animator, you get an overview immediately of the scene; as a director you read the track, how the animator has constructed the scene, and what camera moves are indicated and why.

Of course, the real purpose of these sheets is for communication. If you’re doing a film by yourself and don’t think you need the sheets, then fine. But if you’re working with other people, how else would you communicate what the track is doing or how the scene is constructed?

Certainly, as students, you should be obligated to learn how to use sheets so that you’ll have the knowledge and the experience in your grasp. The more knowledge you’re armed with, the better you’ll make it in the real world.

With the advent of the computer, and as you mention programs such as Toon Boom (which employs its own version of an X-sheet,) studios presumably have reduced their dependence on such charts. Since I know how valuable these sheets are in relaying information, I’ve kept them up in my studio. The sound track is read on the prepared sheets. I don’t demand that anyone fills them out – certainly not when many animators today are developing their animation in the computer – but the sheet gives an excellent way to plan the scene, and the animators can take that information and use it as they like.

In studios of the past, a folder was designed. X-Sheets, when folded in half would sit neatly into the folder (and often be stapled into it) so they would always stay with the scene and not get lost.

I don’t quite know how other studios transfer such info from person to person and keep any oversight on the film as a whole, and your question raises a curiosity that sits in the back of my mind. How does a PIXAR or DREAMWORKS deal with such track readings and director’s notations? Is it all digital or do they actually have a form of X-sheet? If anyone out there knows definitively, I’d be curious.

The UPA NY sheet pictured above, is well designed except for the fact that it

does not include dial numbers. I guess someone can write out all the

numbers, but it doesn’t quite make sense to me.

The Pelican sheet includes the dial numbers, but it’d be nice if they were

also alongside the soundtrack area.

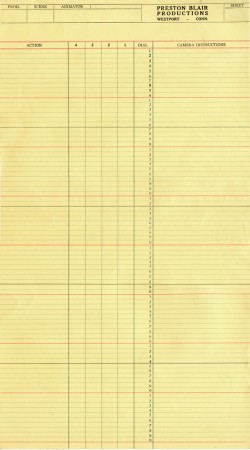

Shamus Culhane Prods circa 1972 | Murakami-Wolf Prods circa 1974

The Culhane sheets are designed for 100 frames per page. I’ve never understood

this calculation. If you do an 80 fr. page, you get five 35mm feet or two 16mm feet.

100 frames gets you nothing but an even number.

There are also no lines on the page making it harder to read.

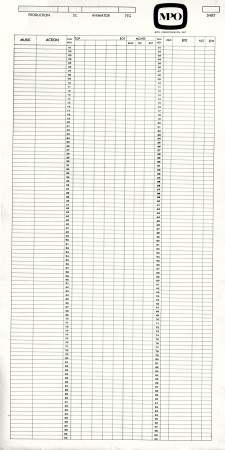

The Murakami-Wolf sheets include 96 fr. per page or six 35mm feet.

These sheets are also unruly in their length.

.

.

Preston Blair Prods circa 1967 | MPO Prods circa 1970

The Preston Blair sheets are close to perfect except for a red line that was added

at every tenth frame. What use is there for it?

The MPO sheets have no lines and are confusing.

They’re similar to Culhane sheets but a bit more legible.

I have more of these sheets, but I think this may interest only me.

I once spoke to my staff for about 2 hours about exposure sheets. Interestingly enough,

I didn’t have to wake anyone at the end of the chat.

I’ll have a bit more to write about this soon, when I pull it together.

on 03 Mar 2009 at 9:59 am 1.John Celestri said …

As an animator and director, I’ve always looked at and used X-sheets as the way to compose movement in an animated film/scene the same way a musician composes music for an orchestra: setting the tempo, calling for transitions, calling for emphasis, etc. Each frame is part of a “note” of movement…and how each “note” is “played” by the animator determines the success of the performance of the scene/film. To me, there is a theory of movement that parallels music theory.

on 03 Mar 2009 at 10:10 am 2.Michael said …

Actually, John, that’s a good analogy. The X-sheets are like music sheets to a composer. Good animation and editing is all about the timing, and I can’t imagine getting timing without looking at an exposure sheet.

on 03 Mar 2009 at 12:11 pm 3.Paul Spector said …

What a great post! I grew up looking at these sheets by the thousands, in my father’s workroom or spread across the dining room table. No one ever had to teach me how to read them, it was easy even for a kid to figure –like growing up in a bilingual household. My big regret is that I only have a few to look at anymore.

on 03 Mar 2009 at 1:16 pm 4.Richard O'Connor said …

Exposure sheets are the most important tool in animation (after the pencil). Especially for some -like me -who can’t draw.

Also to point out on the UPA, Pelican and Murakami-Wolf sheets the 8 frame bold line and the 16 frame dotted or double line. This gives a constant visual timing of feet and seconds.

Interestingly, in checking my web “stats” recently I found a few dozen hits for “exposure sheets”. Maybe students cramming for their animation history midterms.

(no hits for “dope” sheets. can’t use a derogatory term for an invention so useful.)

on 03 Mar 2009 at 2:17 pm 5.Tim Hodge said …

Interestingly, when I moved studios from traditional to CG (and started directing), I found that the small CG studio I was in didn’t use X-sheets. Coupled with that, I had a difficult time explaining timing changes to animators who had never seen a timing chart in the corner of a drawing. I would draw those strange little ladders and get nothing but blank stares.

I learned to work this way for years, then when we had to outsource our animation to India, the studio there insisted that we provide X-sheets w/ dialog breakdowns. At that point, it was almost a hassle for me, because we couldn’t find anyone to read the audio track! (My how times change!)

- T

P.S. Disney x-sheets have 4 feet on the first page and 5 on the following pages. Every 8 frames are separated by a bold line. After CAPS came in, we could have a near infinite number of levels (customized print outs), but had to use only every other column for characters to leave room for the effects levels that would be added later.

on 03 Mar 2009 at 2:26 pm 6.Tim Hodge said …

One more thing…

I’m sure this has been updated, but when I was at Disney, they had developed a proprietary software called Scene Machine. It was a pencil test system that ran on a Mac (and every animator had one in their office). After you shot your drawings, you could adjust the timing instantly by dragging and dropping the numbers in the virtual x-sheet. Once you were happy, you could put the file on the server for the directors to watch and print out your x-sheet so you could fill out the “real” one (the one that stayed in the folder with the drawings) by hand.

on 03 Mar 2009 at 3:50 pm 7.Mike Kazaleh said …

I’m a staunch believer in exposure sheets for all the reasons that have already been stated by others here. I’ve also seen how troublesome it is to try to work without them, as I’ve witnessed at TV studios who rely more on “animatics” than sheets. There’s a lot of problems with this, the two main things are, that it only gives the scene length, and does not break down the timing of what happens in the middle, and that the non-animators at the networks who look at the animatics don’t know how to watch them. Mainly the network guys think everything looks “slow”, but it in reality, the animatic should look slow, because still drawings read more quickly than moving ones, and the animatic doesn’t account for the motion that happens between the drawings. Timing is really the heart and soul of animation, and a lot of people nowadays treat timing as something that works itself out, which of course is absurd.

Those Murakami-Wolf x-sheets look just like the UPA sheets. The x-sheets they used to use at Format Films looked like that, too. I used to work at Playhouse Pictures, and we used leftover Format x-sheets for years (I still have a few pads.) Playhouse didn’t print their own x-sheets until they’d been using computer paint for a while (The new sheets had more columns for virtual “cels” since any number of layers could be used without distorting the background colors, an unfortunate necessity, as our spots were getting more and more complex over the years.) When my friend Ken Mitchroney started a small studio, I used the Format x-sheets as a basis for our own sheets. The only difference was that I added some extra blank space on the left side to give me room to make little sketches of the action.

on 03 Mar 2009 at 4:49 pm 8.Rudy Agresta said …

Excellent post!! Even when I’m using a digital format to produce my animation, I still chart it out on the “X” sheets first. Why one would not want to use an exposure sheet I really don’t understand. The important stuff is ALL there at a glance. As an educator (among other things) by profession, I have seen countless teaching aids/tools/devices fall by the wayside just because someone who doesn’t know any better says, “Hey, we don’t need this!” Presently, it’s the same mentality the “artistic illiterate” suits are using to run most of our beloved industry.

Michael, I’d love to see posted your other samples of exposure sheets that you have collected. They are not just dinosaurs culled from the depths of our artistic heritage, as some may see them. As a composer, studying theme and variation gives one insight into the mind of the creator. The variety of ways that the sheets are set up, I feel, lend itself to a similar type of learning.

on 03 Mar 2009 at 6:15 pm 9.Gene Hole said …

this is very interesting stuff to an avid student like me, I’d be eager to see what other x-sheet templates look like and to hear what you consider useful, distracting, or unnecessary about them, perhaps a post describing what elements make up the ideal x-sheet?

on 03 Mar 2009 at 8:08 pm 10.Hans Perk said …

Mike, you are not the only one who saves exposure sheets and is interested in them! I have a big roll somewhere in storage, and a few at hand, which show me that Disney’s (older) sheets had 5 feet (80x) on the first page with lots of room for notes, and 6 feet (96x) on the second sheets.

They also used the 6-ft sheets for track reading, as in this post here.

The sheets we used for Anna & Bella I had printed up based on older sheets that Børge had, which were exactly like your UPA sheet, which in turn was based on the Disney “2nd page.” These sheets were, I believe, still sold by the Cartoon Color Company in the late 70s, just without the UPA mention. Some of the biggest sheets I have ever seen were–not surprisingly–French, used for early Asterix films, from the late 60s and early 70s – like newspapers.

Børge also had sheets from Toonder studios, where he worked on commercials and shorts from 1950 to 1972, and some had lines at 16 and 25 frames – for PAL. The 10 frame lines on Preston Blair’s sheets would be for NTSC tv, running at 30 fps…

I LOVE seeing all these different x-sheets!

I TOTALLY agree with you in your post on the importance of the exposure sheet! CG animators have their time-line – the exposure sheet is basically a time-line for your drawings. It IS, as you say, the representation of time itself, and how can anyone make “drawings in time” without being able to plant them with “both feet” in that time??? It seems that nowadays people are taught do “make do without?” SHAME!

on 03 Mar 2009 at 8:18 pm 11.Hans Perk said …

–Small correction: Our Anna & Bella sheets were based on the UPA sheets in their Murakami-Wolf disguise as 6 ft (96x) sheets (like the Cartoon Color sheets). The sheets we used on Valhalla, and later, at our studio are based on these, as well. Admitted, you do get used to counting “96 – 192 – 288…,” but in the start I did need to have a little list of this as a cheat sheet…–

on 03 Mar 2009 at 11:02 pm 12.Charles Brubaker said …

Great post, Mike. Interesting to know more about these things.

I remember reading an old post here about musical bar sheets. Thought I’d point out that those sheets were apparently preferred by Hawley Pratt when directing Pink Panther cartoons. DePatie-Freleng’s cameraman would then transfer that to a regular dope sheet for his use.

on 04 Mar 2009 at 3:40 am 13.Steven Brown said …

Bar sheets are even more misunderstood than X-sheets, if that’s possible. Probably Hawley Pratt used them at Friz Freeling’s urging. Corney Cole told me that Friz timed everything on bar sheets, working from the music track.

By the way, now that we are scanning drawings, instead of shooting them on film, shouldn’t we discard the heavy lines every 16 frames indicating feet? How about placing them at every 12 frames indicating a half second (or use sheets like Borge Ring used if you are working on PAL, or Preston Blair’s if you are working in CGI)

on 04 Mar 2009 at 4:44 am 14.Hans Perk said …

Steven, not only does dividing into 16–and 8–make good sense timing-wise in many cases (e.g keys at 1 & 9, breakdown at 5, inbetweens at 3 & 7), but the core speed of film, at 24 fps, is so basic that the division in three parts, with lines every 8 frames is like the minute/second markers on an analog clock: if you tap the lines in a normal-though-not-slow speed, you are bound to do this in actual film speed–an 8-beat, after a little practice (with your metronome at 180 bpm). A 12-beat (half second) is not as easily mastered…

Scanning or shooting them on film immediately – I must admit that cannot see the difference. The thick lines alternating with the thin double lines are just there to make things more easily readable. My two bits…

(By the way, I have posted lots of bar sheets and explain how they were used at Disney during the so-called Golden Age…)

on 04 Mar 2009 at 8:17 am 15.Stephen Macquignon said …

When it comes to finding out how other studios are transferring information maybe

Sue P can put some light on the subject isn’t she a Timing Director?

I just remember how important that piece of paper was with all that information written on them. Computers are good but they don’t replace your brain. How can you build a house with out a blue print? I am happy there is a least one student going the extra mile to learn

on 04 Mar 2009 at 8:37 am 16.John Schnall said …

I’ve been holding my tongue for a day but I have to say it: I hate X sheets. There, I said it.

I spent years as Timing Supervisor (on Disney’s Doug, PB and J Otter, Stanley…), going thru stacks and stacks of X sheets; they’re used both to communicate (good thing!) and to assign blame (bad thing!). Whenever we had a retake my job was to assess whether it was a mistake in our X sheets or a mistake at the overseas studio (read this as: my job was to find out how to blame the overseas studio). So every week, before we shipped our sheets overseas, I had to go thru every sheet, line by line, and make sure it was communicating what we wanted it to. And then when the footage came back I had to show we got it right, and fix it if we didn’t. Somewhere in the middle of the retake sessions for a poorly animated show all eyes would turn to me and I had to become Hugh Grant with his pants down: “Oh, yes, I’m absolutely APPAULED at what we’re seeing. My word, yes, I’m outraged; of course I’ll fix it but more than that I’m sorry your eyes even had to SEE this dreadful work and it’s all MY FAULT…” And then I’d check the sheets and see what really happened.

Our sheets came from timers all over the world; my favorites were the ones that smelled like an Irish basement. Or that time the X sheets got lost in a German bar, and came in with cigarette holes, beer stains and missing pages.

And then there was the actor who was fired at the start of season two, a sound-alike was hired, but then the actor won an Emmy for season 1 and was immediately re-hired; I had to go in and strip in the new dialog track for every line before we shipped. And you know what? When an actor is fired and rehired he revels over every line of dialog; every word rolls off his tongue in a slow and leisurely fashion; every friggin’ shot had to be extended to cover his new dialog (cutting and pasting sheets together, page 80A, B and C; I still get nightmares…).

And then there was the time that an exposure sheet killed my entire family, wiped out my crops, and left me in ruins. Man, I hate those exposure sheets.

But I do still use them on occasion. Damn them.

on 04 Mar 2009 at 8:40 am 17.Michael said …

As I stated in the post, once you’ve learned to read the sheets automatically, you stop seeing lines and start seeing time. You actually, feel it. The lines at the 8fr. mark and the 16fr. mark are instrumental in helping you feel this.

Sheets like the Culhane sheets or the MPO sheets let you feel nothing. It’s just a page with lines on it.

Regardless of whether you’re shooting or scanning the drawings, it’s the animating I’m concerned with. The rest is just process. The exposure sheet with the track read has a heart in it, and the animator just exposes it.

on 04 Mar 2009 at 11:39 am 18.George Griffin said …

Michael, this is irresistible stuff: animator’s catnip. Made me think about those lines every 16 frames for one foot of 35mm film, which was also one second of time before sound. But you had to add a digit every 10 frames to keep the running count accurate. So, there was always a war between a kind of “scientific” decimal mentality and a more “organic” mentality where a second was a triad of 8 frames.

Then there was the idea of time running vertically. That was impossible to give up when I first tried Director with its “score” running horizontally. But now with the After Effects timeline (scalable and with an infinity of layers) I kind of understand the trend away from sheets, and toward ever larger monitors.

But it’s so good, even for experimenters, to have a record of the sequencing and layering, not just for checking (John’s story cracked me up), but also for a record of what “mistakes” actually “work.”

on 04 Mar 2009 at 5:43 pm 19.David Nethery said …

Long live X-sheets !

Though sometimes I do wonder about the relevancy of continuing to count in “feet” (35 mm film footage , 16 frames to the foot) . It was Gene Deitch who put this heretical thought into my head with his take on the matter in his online book “How to Succeed in Animation (Don’t let a little thing like failure stop you.)

In his chapter “The Great Footage Fallacy” he makes the case for seconds based X-sheets with the extra thick line marking every 24 frames rather than every 16 frames. He relates how this came about when he moved to Europe and had to adjust to using the metric system where film is measured in meters, not feet . Gene Deitch reasons:

“If most of the world outside of North America measure film lengths not in feet but in meters, what is it that every filmmaker on the entire planet has in common? Seconds, minutes, and hours! – TIME! Movie making exists in the dimension of time. “

Of course , Hans Perk makes a good point that having the X-sheet marked off with 16 and 8 frame segments (darker line every 8 frames) is better for musical timing with an 8 beat being more common than 12 .

I could go either way on this . Maybe an X-sheet marked off with extra thick lines ever 8 frames with every 24th frame being a thicker blue or red line ?

There’s a nice pencil test application called Toki Line Test which gives the option of formating the digital X-sheet with a thick line every 24 frame or every 16 frames , and also the option of formating the digital X-sheet with a frame count , feet, or time-code along the traditional Dial column.

on 05 Mar 2009 at 6:03 am 20.Gabor Soos said …

I have a question slightly related to this topic.

From what I can see, all X-sheets are geared towards animation working on 24 frames per second.

In my work we have to animate on 30fps, which presents a problem when trying to work out spacing.

Say I want to animate a walk on march tempo, which is a walk on 12′s if you animate on 24fps.

If I want to translate the same rhythm to 30fps, I’d need to animate my walk on 15′s which is a very difficult number to deal. If your contact poses are on frame 1 and 16, where do you put the passing position? It should really go on 8.5!

If I choose to work with more convenient numbers, I’ll miss the beat.

How do people working on 30 or 25 fps deal with issues like this and do they use X-sheets marked with different tempo’s? Like marking a thick line every 15 frames, 10 frames, 5 frames?!

on 05 Mar 2009 at 8:15 am 21.Hans Perk said …

As I mentioned re: Preston Blair’s sheets, you do see sheets with markings related to 30fps. Basically one uses what fits them best, and this fits well for NTSC.

I would think you should not treat timing as too rigid a thing. If your walk is on 15s, I could imagine that that can be close enough to 16s to actually start off as if it is on 16s, with e.g. keys on 1-5-9-13-… and then put one of the inbetweens with little ground contact on ones. Just a thought.

Don’t start me on beats

For those new to beats, for 30fps we find that

Beat = 1800 / MetronomeNumber, and vice versa,

MetronomeNumber = 1800 / Beat.

(1800 being the number of frames per minute – I guess for Drop-Frame this actually should be 1798).

on 05 Mar 2009 at 10:08 am 22.John Celestri said …

Regarding hitting beats: hit it on the frame or 1 frame ahead..passing position the same way. A slight variation keeps the repetitive motion from being too mechanical. However, animating on 24fps gives you the greatest range to work with beats on 4′s, 6′s, 8′s, 10′s, etc.

on 05 Mar 2009 at 4:28 pm 23.ethan said …

I learned to use X-Sheets in school and I still use them today. I find they help me keep my timing on track.

I work in computers, and I’m the only one using the X-Sheet, it doesn’t get handed down to a camera guy. So I’ve taken the liberty of brining the X-Sheet into Photoshop and using layers to figure out my timing. I can make the X-Sheet as long as I want and with the layers it’s easy to make corrections. Because I use a tablet PC it’s almost as good as drawing them. And it’s backed up, I don’t have to worry about loosing it.

on 06 Mar 2009 at 8:48 pm 24.Swinton Scott said …

Great post Michael! Do you know if Disney was the first to use/create exposure sheets? And has anyone ever thought of widening the action column for TV shows animated overseas? And getting rid of the animation columns as well for those shows as well since they are rewritten by translators anyway? When you work on gang shows as a timer there often isn’t enough space to fit all the characters and track their actions on the sheets as they are now. We often wind up pasting over the artwork columns with action columns cut out from blank sheets to give us more space to write descriptions.

Anyway, great post and good to see other sheets from the past!

on 08 Mar 2009 at 3:58 am 25.steven brown said …

Thanks Hans, I went to your site and you had a lot of great information about bar sheets there, as well as some great links. It was interesting what David Nethery reported Gene Deitch saying about timing to seconds, however what you said about 8-beat timing made great sense.

on 27 Mar 2010 at 2:00 am 26.Cheeks Delos Reyes said …

Hi Mike,

I am planning to make a short film.My colleagues wanted me to provide an x-sheet for them to use. My problem start because I don’t know how to expose action accordingly to the time line. Could you make a crash course how to prepare an actual expose sheet.

Thank you very much you help me a lot on your previous blog

on 27 Mar 2010 at 8:12 am 27.Michael said …

Charles, anything goes as long as you can relay the information you want to your animators. The “Action” is written in the left hand column and should indicate how long any action is. My tendency is to give very little information to the animators, but then I work with generally experienced animators who have a feel for timing.

If you want to dictate the length of every action – character bends over, character ties shoe – character stands up – you need only tell where that action takes place and for how long on the sheets. Try using a stop watch to guage how long every action is if you don’t feel comfortable just making it up.

write: Character bends over then draw a line through 16 frames (1-16) if that’s how long you want it to take.

Character ties show – draw a line through the next 36 frames (if you determine that’s how long it should take) (17-52)

Character stands up – draw a line trough the next 16 frames (53-68).

Continue this for as long as you want to detail instructions.

When they send timing sheets to an outside studio, every tiny detail is described and dictated. The director wants to make sure it’s his timing and the Outsided Studio doesn’t want the responsibility if the timing is too rushed or slow.

Here’s a sample XSheet taken from Harald Whitaker’s book, Timing for Animation. Action, again, is in the left hand column.

(Click image to enlarge.)

on 17 Apr 2013 at 1:39 am 28.Kathleen Quaife said …

For any one who wants a nice simple 8.5 X 11 Xsheet I made one ( mostly for students) and posted it on my blog here. ( 24FPS/ TWO seconds on a page/ thick line after 8 frames )

http://kathleenquaife.blogspot.com/2013/01/blog-post.html

Does anyone really know the origin of why this is called a “dope sheet?”

on 17 Apr 2013 at 5:50 am 29.Michael said …

I’d always assumed that the “dope” in “dope sheets” referred to the usage of the word wherein “dope” meant “information”.

from Merriam Webster:

3 the dope : information about someone or something that is not commonly or immediately known

â–ª What’s the dope [=skinny, scoop] on the new guy? [=what do you know about him?] â–ª The magazine claims to have the inside dope [=information known only by those involved] on her new romance. â–ª Give me the straight dope on it. [=tell me the truth about it]

It’s slang but it was used in the Thirties frequently enough.

on 27 Aug 2013 at 8:57 am 30.Verlene Mceuen said …

Your website has plenty of good information. Can I link to you with dofollow link?

on 27 Aug 2013 at 7:30 pm 31.Michael said …

I have no such link.

on 30 Mar 2017 at 1:52 pm 32.Daniel Werneck said …

This is one of my favorite posts of all time and I come back to it time and again. Thank you so much for this! I wish there was an entire book dedicated to dope sheets.

on 03 Aug 2024 at 7:21 am 33.latinas said …

Last modified on Thursday 20 February 2014 10.45 GMT.

on 07 Aug 2024 at 7:39 pm 34.crypto said …

Actually no matter if someone doesn’t be aware of afterward its up to other users that they will

assist, so here it occurs.

on 09 Aug 2024 at 10:36 pm 35.berita said …

Having read this I thought it was rather informative.

I appreciate you finding the time and effort to put this information together.

I once again find myself personally spending a lot of time both reading and leaving

comments. But so what, it was still worth it!

on 21 Feb 2025 at 4:25 am 36.Marketing sur les réseaux sociaux said …

Votre article sur le SEO local et les réseaux sociaux est très pertinent, merci!