Articles on Animation 16 Jun 2009 08:52 am

Journal of Int’l Animated Film 2

- Last week, I posted a short piece on British animation in 1957. This came from a Journal that was released (in the days before ASIFA) on the International state of the animated film.

- Last week, I posted a short piece on British animation in 1957. This came from a Journal that was released (in the days before ASIFA) on the International state of the animated film.

The Journal coincided with the “first International animated film festival in Britain” at the National Film Theatre during February and March 1957.

They screened some 150 films, including 12 of the 31 features produced to that time.

The hope for the festival was to encourage theatres to include animated shorts on their programs again. The art form was dwindling. At that time, no one saw television as the panacea it would become.

This document gathered seven different writers and filmmakers to write about the state of animation in the respective countries.

AT THE Cannes Film Festival in the spring of 1956 I overheard a ticket taker remark to a puzzled tourist who evidently had tried unsuccessfully to get into the premiere of one of the full length feature presentations, “II y a aussi des petites dessins-animes.” Judging from the tone in which he spoke, half condescending, half affectionate, his words seemed to imply “tough luck, but as a consolation there are some little cartoons to be seen if you care to have a look.” He was referring to the International Festival of Animated Films which was taking place at the same time in another part of the cinema Palais. His attitude was similar to that of the general run of movie-goer everywhere. The cartoon is usually considered a

pleasing little hors d’oeuvre to be enjoyed along with more substantial fare. That this hors d’oeuvre is welcome is apparent in the little murmurs of anticipated delight which still run through most audiences when the faces of Pluto, Mickey Mouse or Mr. Magoo come on to the screen. It is as though the audience realizes that for a few minutes they will be spared the sensational horrors which so often appear in the newsreel, or the tired cliches of a third rate travelogue. With the cartoon the audience can enter into a realm of pure fantasy, in which the laws of gravity are nonexistent, where pain is not pain and where characters become symbols or stereotypes, not to be taken very seriously.

pleasing little hors d’oeuvre to be enjoyed along with more substantial fare. That this hors d’oeuvre is welcome is apparent in the little murmurs of anticipated delight which still run through most audiences when the faces of Pluto, Mickey Mouse or Mr. Magoo come on to the screen. It is as though the audience realizes that for a few minutes they will be spared the sensational horrors which so often appear in the newsreel, or the tired cliches of a third rate travelogue. With the cartoon the audience can enter into a realm of pure fantasy, in which the laws of gravity are nonexistent, where pain is not pain and where characters become symbols or stereotypes, not to be taken very seriously.

The audience which strayed in to see the animated films at Cannes (the tickets were free) bore little resemblance to the self-conscious, publicity hungry international set which attended the gala openings of the longer features. The cartoons were attended by the producers themselves, a motley crew from every corner of the earth, and casual spectators from the streets, curious and unprejudiced. It was interesting to watch the reaction of this audience to films which ranged all the way from animated folk tales of Texas to heavy political propaganda from both sides of the iron curtain. The actor who drew the most spontaneous outburst of laughter was that ageless veteran whose career has remained unchanged throughout the years, Mr. Donald Duck. His frustration in the film which so delighted the audience was caused by his ineffectual efforts to fall asleep in spite of a relentless neon light which kept flashing off and on, and the insistent sound of dripping water from a tap which gradually increased in his imagination until each drop seemed a bomb visibly shaking the whole earth with rhythmic concussions. Donald’s frustration, seemed on that afternoon in Cannes to be such a note of understanding which reached across the

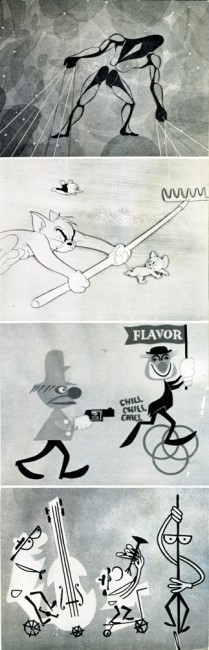

To Your Health, Tom & Jerry________barriers of language and nationality. This particular

Balentine Beer commercial,_________film was, as always with Disney, elaborately anima-

Winston Cigarette commercial_______ted, no economy tricks employed, no corners cut.

_______________________________The sound track with its metamorphosis of dripping water to world-shaking “booms” was imaginative and appropriate to the medium. Also, like most of Disney’s films, it was a sample of the usual over-cute style with background drawings similar to the easiest kind of commercial advertising.

It is impossible to consider the animated film in the United States without thinking first of Disney. After 30 years his name is still synonymous with the short cartoon in the minds of most of the American movie-audience. Sometimes during the long period since his first exciting Silly Symphonies appeared, the work from his large organisation in California seemed to have sunk into the doldrums. Formula replaced invention. The medium lost its initial public appeal. Disney’s excursions into the field of “live action” have been sometimes rewarding, sometimes disappointing. Some of the wild life films have recaptured the excitement of his early cartoons, while the romantic historic costume pieces have often seemed banal. Always a clever  showman, he has recently built a large fun fair, or amusement park in California which serves also as a setting for television programme material. When, from time to time, a new feature length cartoon appears, such as Lady and The Tramp, in which the chief characters are dogs, one is amazed at the technical slickness of the animation and annoyed by the weak story line, which seems to be influenced by the wish to include every sure-fire box-office trick. This approach does not lead to any fresh experiments within the medium.

showman, he has recently built a large fun fair, or amusement park in California which serves also as a setting for television programme material. When, from time to time, a new feature length cartoon appears, such as Lady and The Tramp, in which the chief characters are dogs, one is amazed at the technical slickness of the animation and annoyed by the weak story line, which seems to be influenced by the wish to include every sure-fire box-office trick. This approach does not lead to any fresh experiments within the medium.

It was the short film Gerald McBoing-Boing which first brought a radical change of style to the attention of the public in America and soon after to the cinema-goers in Europe. This highly original short film, produced by U.P.A. Pictures, with finely integrated music by Gail Kubik and with sophisticated visual elements, seemed to satisfy a public at that time weary of the Disney formula. The talented minds which produced “Gerald” had made previous cartoons in which visual wit and economical animation had replaced the elaborately evolved techniques established by the larger studios, but these films had never been seen in the theatres. Some of the U.P.A. men had worked previously in the Disney Studios. The organisation under the leadership of Stephen Busustow has now expanded into the field of television. Robert Cannon, one of the most brilliant U.P.A. directors, brings a fertile imagination and fresh approach to each new film he creates. Another director, Pete Burness, who has been with the U.P.A. since its early days, has created a now popular cartoon character, Mr. Magoo, whose blithe innocence and near-sightedness leads him unscathed and unconcerned through the violence of the modern world. Mr. Magoo, like Donald Duck, has become a beloved international personality.

The U.P.A. style, according to their own spokesmen, derives from “modern” art. It is uncluttered, flat and often linear. The characters do not seem bound by any natural physical laws of movement. Perhaps one of the greatest contributions of the U.P.A. is that they have shown the public that the less realistic a movement is, the more creditable it becomes optically. Disney sometimes bases the movement of his characters on live action models, as with Alice in Alice in Wonderland. The greater the effort to imitate realistic movement, the more apt one is to be aware of the stroboscopic nature of the medium, the more jittery the result. If legs are used to express the symbol of walking, rather than the imitation of walking, the illusion of movement is more acceptable, a paradox which indicates the validity of the “modern” art approach. Like any device this simplification can be carried too far. If the human figure becomes too abstract it may lose all its expressive power. Usually the U.P.A. figures, moving flatly on a flat screen are consistent, humorous and convincing.

Magoo Beats the Heat , Madeline

Less effective have been certain of the U.P.A. attempts to animate the drawings of “big name” illustrators, such as Thurber and Bemelmans. The Unicorn in the Garden and Madeline are examples. Since the quality of both Thurber’s and Bemelmans’ drawings depends on a subtlety and unevenness of line which is impossible to use in the animation technique, where every celleloid must have an almost mechanical similarity, the flavour of the original is lost and the result is far less successful than the work of lesser known artists, whose training within the film medium has taught them its restrictions.

Nevertheless, the U.P.A. has been a healthy influence in the United States. The proof that a new style has had its effect on Disney and his imitators is seen in their efforts to modernise their own productions. Disney has released a short history of music called Whistle, Toot, Plunk and Boom, which seemed to imply that if his studios wished, they too could work in the “modern” style. The popular M.G.M. films, with incredibly fast pacing and surrealist gags, seem also to have cancer research or democracy. Which does not mean that good films cannot be made on these themes. But there is little chance for the individual to produce a genuinely experimental film on his own subject.

It is difficult to say what the future of this medium in the U.S. will be. At present animation is still popular in the entertainment fields and in commercial television. Some of the most imaginative uses of animation at present are in one-minute TV commercials. Animation is in demand in those sponsored industrial films where a mechanical concept can be shown more clearly than it can in live-action. Animation is also useful in industrial films which try to express abstract ideas or fantasy.

Donald Duck, in his better movements, still communicates to an international audience. It would be interesting to speculate, however, as to what animation might have been if Disney had not had his enormous influence. In the first place, animation might not necessarily have been only cartoon. The simplest visual element, a dot, or a line, can become a dancing symbol and convey an idea, an association. These ideas could be developed with other means than by conventional story telling. The film need not always be based on a literary concept. It could be, for the spectator, an experience like seeing dancing, or hearing music. Within the medium not only new forms, but new ways of expression could be evolved. The animated film need not always be a pastische, a sequence of gags or a fairy tale. It could be a powerful medium. It is condensed and potent. Like most potent things, it is better in small doses. But in a brief time it can pack a terrific punch. In the end its possibilities are limited only by the imagination of the filmmaker.

on 16 Jun 2009 at 12:42 pm 1.Jerry Beck said …

Another great post. Thanks Michael. One small correction, and I realize the error may not be yours – it may have been captioned that way in the Journal. The Magoo image is a publicity cel set-up from the cartoon called MAGOO BEATS THE HEAT (1956, in which Magoo thinks he’s spending a day at the beach but he is actually in the middle of the desert), not MAGOO GOES WEST (which was also from 1956).

on 16 Jun 2009 at 2:00 pm 2.Michael said …

Thanks, Jerry. I just transcribed the title in the publication (which read: Magoo Goes West.) I corrected it in the original post.

on 16 Jun 2009 at 7:49 pm 3.Stephen Worth said …

The image of the jazz trio at the top is from a commercial by the Ray Patin studio. The original art for that still belongs to Dan Goodsell. He let the ASIFA-Hollywood Animation Archive scan his collection of Ray Patin artwork…

http://www.animationarchive.org/2005/12/media-last-of-ray-patin-art.html