Articles on Animation 17 Nov 2009 08:43 am

Norshtein 1980

- This article, written by Yurij Norstein, appeared in Animafilm 5, March 1980. How could I not reproduce it, since it appears nowhere else on line or in print, that I know of.

L’Art tout court

by Yuri Norstein

WHAT IS ANIMATION FOR ME? Just a field of art, I suppose. T don’t regard it as something separate, I don’t think it has its own laws different from those applying to art in general. Another thing is that being a new field of art, it is looked down upon by feature film, just as film itself was once looked down upon by the theatre. People often treat animated film as if it were something inferior, and underestimate its artistic possibilities and social significance.

WHAT IS ANIMATION FOR ME? Just a field of art, I suppose. T don’t regard it as something separate, I don’t think it has its own laws different from those applying to art in general. Another thing is that being a new field of art, it is looked down upon by feature film, just as film itself was once looked down upon by the theatre. People often treat animated film as if it were something inferior, and underestimate its artistic possibilities and social significance.

In my opinion the essence of art is not confined to the fact that it serves concrete purposes, such as providing emotional experience or entertainment. This does not mean that art does not perform these functions. It does. What Aristotle said still holds: art, above all teaches man to enjoy life.

But Leo Tolstoy, for instance, used to say that if he were commissioned to write a work on a clearly defined theme with a precisely stated social function, the writing would not take him more than two hours. He would add that he wrote mainly about people, about relations between people, in order to force the reader to laugh or cry, that he sought to release ordinary human reactions characteristic of life. His idea was that man should see in an artistic work everything he could perceive in life, out that this should be presented in the form of certain regularities. This means that life and art are different concepts; art always assumes objective significance, it becomes an historical phenomenon, while what we call ordinary life and the events taking place in it, do not have this character.

Of course I do not single out animated film as a field of art guided by its own principles. According to me its principles are exactly the same as those governing other fields of art; they are taken from life, but at the same time the collected material is subjected to some specific processing. This material consists of human emotions, joys, tears, love and everything that is contained in our life and that the artist turns into art.

NO, ANIMATION IS NOT THE ONLY FIELD OF MY ACTIVITY. As a matter of fact, I make drawings for animated films. I also practise painting, but I treat this as a purely personal affair. My attitude to animation is rather specific; it is determined by the neccessity of choice. This is not so much a matter of choosing content wirh a clearly defined plot or idea. It is something much more, for in my opinion an animated film does not merely express some idea.

NO, ANIMATION IS NOT THE ONLY FIELD OF MY ACTIVITY. As a matter of fact, I make drawings for animated films. I also practise painting, but I treat this as a purely personal affair. My attitude to animation is rather specific; it is determined by the neccessity of choice. This is not so much a matter of choosing content wirh a clearly defined plot or idea. It is something much more, for in my opinion an animated film does not merely express some idea.

An idea can be formulated in words; the means of expression used in the visual arts are not indispensable here. But there may be something more which I may find difficult to put into words and which perhaps is not necessary for me. I have in mind the ideas composed of concrete pictures, of the artistic context in which these pictures exist, of colours, tones, some kind of flora, words, music, all those devices which can create something that cannot he translated into a language of words, that cannot he formulated as a definite idea of a film.

Of course, the artist must have this idea in himself. However, this idea is much more general than the concrete idea existing in a film. This is how I understand art, and this is what animation means to me.

Of course, the artist must have this idea in himself. However, this idea is much more general than the concrete idea existing in a film. This is how I understand art, and this is what animation means to me.

I am not interested in films with a definite plot and do not want to make them. Why? Because a clearly formulated plot constitutes the deductive side of every film, a side followed attentively by every spectator. But if a film is reduced to the unequivocal content of its story, the content ceases to interest the public when they see it for the second or third time. I think that if a film is interesting, the spectator will always want to see it again, in order to follow not the plot itself but those elements that are connected with reality and have been expressed in a definite artistic language.

WHY DO I USE A TECHNIQUE that, in a way, makes my films different? I think this technique allows me to make wide use in animation of my artistic pursuits, for it combines animated puppets with animated cartoons.

Animated cartoons are a more dynamic art; animated puppets arc more static. Dynamism and inattention to the plot are alien to the latter owing to their very nature. Puppet animation is a much more philosophical art, I think. But at the same time it lacks the flexibility characteristic df animated cartoons; it does not give the artist the same freedom of handling figures and objects.

So my technique combines the good and bad sides of animated cartoons and puppets, and this can be reflected in various ways. The point is that in spite of everything, this allows me to subordinate the entire artistic background created for the needs of films to my inner ideas, to my artistic credo.

ARE THE POETIC NATURE OF THE PLOTS OF MY FILMS and their poetic form a result of my interest in painting? Yes, to some extent they are. I think that every animated film director is always interested in painting or in the fine arts in general. This is only natural. After all, an animated film has a dual nature. An artist creates a new original artistic background in which I, as a director, must create a definite dramatic action. Hence the dual character of animated films, and the difficulty of creating the proper artistic background. The spectator

ARE THE POETIC NATURE OF THE PLOTS OF MY FILMS and their poetic form a result of my interest in painting? Yes, to some extent they are. I think that every animated film director is always interested in painting or in the fine arts in general. This is only natural. After all, an animated film has a dual nature. An artist creates a new original artistic background in which I, as a director, must create a definite dramatic action. Hence the dual character of animated films, and the difficulty of creating the proper artistic background. The spectator  should adapt himself to this background, penetrate it, and participate in the film on terms dictated by the subject.

should adapt himself to this background, penetrate it, and participate in the film on terms dictated by the subject.

THE STYLE OF MY FILMS, THE WAY THEY COMBINE JOYS AND SORROWS, their light character? I think this is necessary in animation. After all, it is important to awaken something in the spectator, something that will remain in his soul, something he will want to return to. I wouldn’t like to make films that influence the public only by their physiology.

I have in mind overabundance of artistic elements or shocking, unusual scenes. The picture of a killed child will always move the public, but this is not necessarily an artistic experience. An artistic experience occurs when a film contains definite mutual relations perceived by the spectator, relations which make him think. The same scene with a killed child will then make a different impact.

In my work I seek to combine all the elements of an animated film into one absolute whole: the settings the background and figures and assembly.

IS AN ANIMATED FILM LESS determined by technical limitations than other kinds of film? On the whole, animated films arc all the better for technical limitations. To begin with, technical limitations make the artist consider the conditions dictated by the fact that he is making an animated film.

Besides, I think that both objective and deliberate, conscious limitations are necessary in animated films. 1 cannot express opinions about other kinds of films. I take no part in their making and I am only a spectator. But if we arc to compare them, my opinion is that is good for one kind of art is not good for another. And I don’t think one can say that one kind of work in film is less important or less difficult than another.

In an animated film the material itself may create greater possibilities. In a feature film with actors the shifting of a machine to where the director wants it to be may be very difficult. But the entire background is already there; it exists in its basic forms. In an animated film everything must be created from the very foundations; one has to choose, to find all the necessary elements, the best ones. This is just as complicated as the shifting of a machine in a feature film. As in art in general.

WHAT KIND OF SPECTATOR DO I HAVh IN MIND DURING MY WORK? This will sound like a paradox but I think mainly about myself. This may sound cynical. For me, however, this is the most objective evaluation of what I am doing. If I thought, let us say, about crowds of spectators, I wouldn’t be able to take the tastes of each of them into consideration. And if I assumed my film was meant for an artistic elite, sensitive to all artistic innovations, things would be very much the same. Especially as the elite may be wrong too, in fact it is often wrong because it is sensitive to the creative side and may not perceive the rest.

So when making a film I think of myself, of how I will receive it, whether it is simple and understandable. There is a certain danger here, for I move within my film all the time, so it may seem understandable to me without really being so.

Undoubtedly, this is not the most objective way of finding out whether I can reach the spectator or not. Nevertheless, I think that this approach to creative work allows me to come nearer the absolute which exists in my imagination. Another thing is that when I am working on a film I tell my friends what I am doing and watch their reactions. And this is often helpful as it allows me to see whether the effects I achieve arouse interest or bore people. I take these reactions into consideration, change certain things, have yet another look at some fragments. However, when I am absolutely convinced I am right, I do not change anything, even if I notice a lack of interest in my ideas during a conversations, I am inclined to admit that I may have made a mistake. Now and again, very often in fact, T talk with my children, relate various episodes to them, watch their reactions and draw conclusions.

I think that films for children can only be made by an artist who understands children. If he can play with three- or five-year olds, it means he can look at the world through their eyes and can make films for them.

THE FUTURE OF ANIMATION? I see it in rather dark colours. I cannot say whether this is connected with limitation of a technical nature or the crisis of the animated film in general. Each of us goes through some critical moments, especially when we have achieved something and feel that further work will be just a repetition. We then begin to look for something completely new, we find some analogies with literature and feel that this is what we want; but at the same time we feel that we cannot express this, that not everything has been fully grasped. These are very difficult moments, especially when one sets to make photographs and the doubts have not been removed yet. Such a crisis can be overcome all of a sudden, under the influence of something quite unimportant. But before this happens there is a lot logo through.

DRAMATURGY IN ANIMATED FILMS. In my opinion the present principles of dramaturgy in  animated films are wrong because they are the same as those in feature films with actors. Disney somehow managed to cope with it but not because he set himself high moral requirements but because at every moment he was in full control over every detail. Literature, which is now a kind of basic art, reaches the reader slowly and a bridge is a piece of metal difficult to be engraved upon but once this has been done, it lasts for a long time. Literature is similar in this respect and film cannot compete with it. A film does not usually remain long in human memory, and it seldom exerts an influence on people’s attitude to life, etc. There have been exceptions, hut they have been few.

animated films are wrong because they are the same as those in feature films with actors. Disney somehow managed to cope with it but not because he set himself high moral requirements but because at every moment he was in full control over every detail. Literature, which is now a kind of basic art, reaches the reader slowly and a bridge is a piece of metal difficult to be engraved upon but once this has been done, it lasts for a long time. Literature is similar in this respect and film cannot compete with it. A film does not usually remain long in human memory, and it seldom exerts an influence on people’s attitude to life, etc. There have been exceptions, hut they have been few.

The reason why I say this is that the principles of dramaturgy, especially in feature length animated film, have been transferred unchanged from ordinary films. This is wrong in my opinion. An animated film sould make use of all the means which an artist can create in his studio. In Chaplin’s films everything is contained in his acting. One gesture comprises elements of various genres: from the fantastic to absolute realism and even atavism.

An animated film is by its very nature an art composed of various genres. It contains myth, fantasy, cosmogonic ideas, absolute realism, and even naturalism or mysticism. I think that the combination of all these elements could contribute a lot to the animated film, especially feature-length film. But I have never seen such a film. Not yet. All I see are films with a plot which could just as well be played by an actor.

Painting is developing in various directions while the animated film seems to be at a standstill; it does not show dynamism in development. It lacks something; it seems to be confined to one genre. I think that a study of literature, especially ancient literature, which combines various genres, including the Bible, which contains practically all elements from comic to tragic ones, that is, the entire richness of human life, would be of great benefit for animated films, especially feature-length ones. I think that a feature-length animated film should not just tell a story. It should present the richness of human life and, making use of the specific properties of animation, look for its own ways of development.

Recorded by Mieczyslaw Walasek

YURI NORSTEIN: FILMOGRAPHY

1968: 25th – THE FIRST DAY

1971: THE BATTLE OF KERSHENZ (prizes: Zagreb, Tbilisi)

1973: THE FOX AND THE HARE (prizes: Baku, Zagreb)

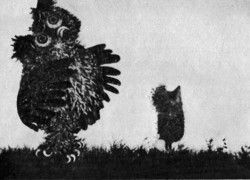

1974: THE HERON AND THE CRANE (Kischinjow, Annecy. New York, Teheran, Tampere, Melbourne)

1975: THE HEDGE-HOG IN THE FOG (prizes: Frunse, Karlove Vary, Melbourne, Gijon)

1979: THE TALE OF TALES (prizes: Ashabad, Lille, Obcrhauscn).

Illustrations:

1. Norstein (1980)

2. The Heron and the Crane (1975)

3. The Heron and the Crane

4. The Hedge-Hog In the Fog (1979)

5. The Hedge-Hog In the Fog

6. The Hedge-Hog In the Fog

on 17 Nov 2009 at 10:33 am 1.Ray Kosarin said …

A beautiful interview! Much here for us to think about. As with the films, he is 100% authentic and trusts us to stick with him, even if he asks us to pay closer attention than we are accustomed to the delicacy of what he has to say.

It’s the best compliment when an artist trusts us like this. Most artists interviews (DVD commentaries, too) hype–and generally cheapen–the work. This is very different. It enriches it and makes us wish to go back to it.

on 17 Nov 2009 at 1:35 pm 2.Michael said …

There’s no doubt that Norshtein is THE guy in animation. Keep an eye out for the post on Thursday. I’ll be offering cartoons published by a member of Norshtein’s crew – a delightful little Japanese book Richard O’Connor sent me.

on 17 Nov 2009 at 5:35 pm 3.Eimhin McNamara said …

Thanks so much for sharing. Everything he does seems to turn to gold.

on 25 Nov 2009 at 1:48 am 4.Niffiwan said …

Thank you very much, Michael. There is one sentence that I don’t understand – are you sure you transcribed it correctly?

“However, when I am absolutely convinced I am right, I do not change anything, even if I notice a lack of interest in my ideas during a conversations, I am inclined to admit that I may have made a mistake.”

The sentence seems to contradict itself.

on 25 Nov 2009 at 3:28 am 5.Niffiwan said …

Unless he means that he made a mistake in noticing the lack of interest.

on 25 Nov 2009 at 8:42 am 6.Michael said …

I’ve transcribed it exactly as it appeared in the magazine – bad translation and all (“conversations”). I think it may have been inaccurately translated for the magazine; it probably should have been: “I am NOT inclined to admit that I may have made a mistake.”

on 25 Nov 2009 at 11:16 pm 7.Niffiwan said …

I made a quick mention on my blog (I should’ve mentioned it sooner, but I was busy…):

http://niffiwan.livejournal.com/25040.html

I’ve also made a PDF of this essay over here, fixing a few transcription errors (eg. “arc” instead of “are”):

http://www.mediafire.com/?minjkznzdmg

on 06 Dec 2009 at 11:11 am 8.Sunny Kharbanda said …

Very inspiring! I wrote up a post about this, highlighting some important “lessons” from this article, along with my own thoughts or example films that support his ideas.

Thanks for reproducing this!

on 18 Mar 2012 at 5:49 am 9.catherine said …

Very nice post,Been looking for this. Thanks.