Action Analysis &Animation Artifacts &Disney &Frame Grabs &repeated posts 31 Jul 2012 05:12 am

Elmer Elephant X-Sheets – recap

- This old post on Exposure Sheets was a popular one back in March, 2009. Today most animators work with the track and no track reading or record of the moves they’ve done. It’d be a nightmare to try to reconstruct what they’ve done in a scene. All we now have to go on is the completed scene. A lot is lost in the history of animation being done today. For that reason, I thought it’d be nice to take a look at all we can learn from one simple X-Sheet.

Robert Cowan sent me an exposure sheet that was tucked into an envelope in the Ingeborg Willy Scrapbook, which he owns. (Ingeborg Willy was an inker working at Disney’s during the 30′s and made a photographic scrapbook of her stay.)

The sheet is from the Silly Symphony, Elmer Elephant (1935).

(Click any image to enlarge.)

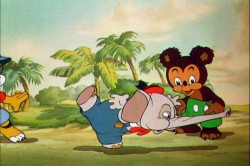

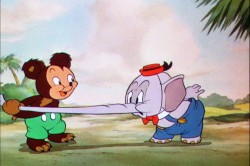

The film’s about a bunch of baby animals.

Elmer is the shy kid who gets laughed at by the other kids.

Eventually with the help of an old giraffe he saves the day by putting out a fire …

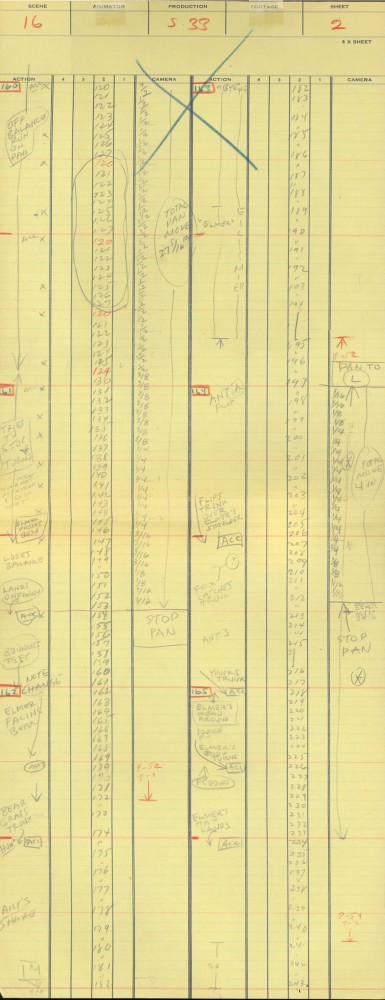

This exposure sheet is about a sequence wherein Elmer is pushed across a row of animals and is poked and prodded in absolute humiliation.

Let’s review what’s on the sheet for the completely unitiated viewer:

There are several columns: Action, 4,3,2,1 and camera.

These are basic to all X-sheets. Sometimes you get 5 numerals, oftentimes you get a column for Bg. Uusaly there’s also a Track column.

Below these descriptives you have lines. Each light blue line represents one frame of film. If the drawing’s on twos or threes or more it’s indicated as in #149. Other numbers are on ones – one frame per drawing.

In the “Action” column, the director writes notes telling where he wants some action to happen. For example: the director has noted that he wants Elmer to try to stop his turn from frames 32 through 49. The animator will follow this as best as possible.

The numbered columns represent cel levels. #1 is the bottom cel and #4 is the top cel. Most sheets also have a column for the Background so you know what number Bg is called for.

The “Camera” column indicates any special camera movements or effects. There we see a pan. The Bg is moving from screen right to left. The actual amount of the physical movement is indicated on every frame. 1/2 is a half inch, 1/4 is a quarter inch etc. Pans usually slow down as they come to a stop and gear up when they start out. This is why it goes from 1/2 to 3/8 to 1/4 to 3/16 to 1/8 to 1/16 before you reach STOP PAN.

You’ll see the sound track indicated at red marked 163 top line middle of the sheet. A character is saying, “Bye Elmer.” The actual number of frames it takes is broken down for you. The animator would animate the mouth accordingly.

Here are frame grabs for the part exposed.

1

1  2

2

Let’s analyze the exposure sheet a bit. (For those not familiar with X-sheets, I have more of a breakdown below.)

First off, for me it’s an oddity. There seem to be two sheets combined onto the one. It’s split down the middle into two full sheets – all using only one cel level.

Secondly, there are some highlighted numbers – 160 through 165.

These fall at every 32nd frame. I’m not sure why. It’s not a foot (16 frames) or a second (24 frames). Is it a beat? I notice that the action calls for “ACC” at each of these markings. I assume it stands for “Accent” which would make that part of a musical tempo. Every 16th frame is also marked in red. This would be the only indication that this is what it is.

The pan moves are indicate in FRACTIONS ! I’m not sure why since it created a difficult transposition to decimals for the camera operator. I mean 3/8 of an inch equals what? Quickly now. Time is money. How about 1/16th? I have only met fractions which divided into 20ths. When did the change come in? John Oxberry, anyone?

Of course, some master checker would probably do the math before the scene got to camera.

Some of the drawings are exposed on twos, even for a short bit during the pan. This would be anathema in modern day animation, yet it hasn’t gotten better.

The track reading isn’t the most detailed I’ve seen, yet it does the job, doesn’t it?

The film is directed by Wilfred Jackson. I assume the “Action” column was filled out by him. I think the animation was by Paul Hopkins.

There’s a lot of information that can be pulled out from this one exposure sheet of a film done 73 years ago. Is that enough reason to advocate for continued use of the Exposure Seet?

on 31 Jul 2012 at 9:15 am 1.John Celestri said …

Excellent post, Michael. As I’ve always said, exposure sheets are the Director’s plans for the entire picture, tying everything together for all departments to see and coordinate with each other.

on 01 Aug 2012 at 11:53 am 2.peter hale said …

I think the numbers 160-165 would be the “measures” on the bar sheet. The exposure sheets themselves were not the Director’s blueprint, they were transpositions from the bar sheets, which allowed the director to plan larger swathes of the action than the exposure sheets allowed.

While working on the first sound Mickeys, Wilf Jackson found it difficult to follow the musical ‘score’ over the numerous camera sheets and suggested they work on a separate chart divided up into musical bars, representing the beat, like sheet music. Each bar was called a “measure” and the number of beats per measure (the time signature) was noted at the start. This sheet was not divided into frames, as the number of frames per beat could vary, but the number of frames that a bar represented was noted on the chart, so that the divisions could be marked off that number of frames on the exposure sheet.

This became the Director’s overview and his planning would be done on these (fewer) sheets, then transposed onto the X-sheets for the animator’s use.

The bar sheet was so useful that it became the industry norm, though for convenience the bars were printed broken down into 16 frame units (feet) with the eighth frame marked taller to denote the half-foot (one-and-a-half feet being 24 frames = 1 second). This lost the point of the bars as beats – the beats had to be marked where they fell – but was invaluable in giving directors an overview of the film 12 seconds to a sheet.

on 01 Aug 2012 at 12:13 pm 3.peter hale said …

The double x-sheet is very interesting – I’d not come across the idea before. I guess the “8 x sheet” printed top right means it covered 8 seconds of action, unlike the 4 seconds of a ‘normal’ single sheet.

Was this an economy measure, intended just for the animators – maybe just for line tests? – with a clean single width sheet containing fuller camera instructions being prepared when animation was approved?

And as for the fractions – did Disney perhaps start off measuring camera moves in 16ths of an inch? They certainly had some practises that did not become universal – their field sizes for one: the idea of naming the field by the measurement of its width seems more obvious. Was the Disney system based on the column height of the camera, or what?

on 01 Aug 2012 at 1:36 pm 4.Scott said …

Wow. Planning out an ENTIRE film in advance by the frame? What a dying/lost art. In this day of “direction by correction,” due to a growing lack of ability by directors and film makers to visualize without tremendous amounts of detail, what a breath of fresh air.

on 01 Aug 2012 at 4:24 pm 5.Michael said …

The old Disney field guides were measured not in inches but in millimeters. One 35mm frame equaled a one field: 1 inch = 2.54 cm. Hans Perk has on his site A FILM LA a way of calculating a Disney field to an Acme field. You can read about it here. A Film LA is a a great site. Stay there and look at some of the material there including everything you want to know about bar sheets.

on 02 Aug 2012 at 11:26 pm 6.Rodney said …

Great find and walk through.

I have long been curious about the beginnings of xsheets and hope to explore more.

on 03 Aug 2012 at 12:05 pm 7.peter hale said …

Michael – thanks for your link to Hans Perk’s site (I do follow his blog, and was aware of his converters, but haven’t really read his back pages.) The great thing about your link to ‘bar sheets’ is that it goes straight to an X-sheet for Steamboat Willie, which has 3 sets of columns on a page! Interesting too that the words to Steamboat Bill are marked, along with the beat – presumably the only way to show how the music was unfolding (you could sing along to it!).

Are you sure about Disney fields having been measured in millimetres or related to the 35mm frame. The inch widths for Disney fields 3, 4 & 5 are 2â…â€, 5¼â€and 10½†– which do not have significant metric equivalents. The field heights do convert well to millimetres, being 100mm, 150mm and 200mm – but it is usual to measure the longest side, as this gives greatest accuracy; and why call these 3,4 & 5 rather than 10, 15 and 20 if the measuring is significant? It is worth noting that Disney animators habitually sub-divided numbers down into vulgar fractions. If they didn’t even use decimals why would they be measuring in millimetres rather than inches?

Hans Perk speculates that these sizes derived in some way from the camera bench. It

would seem likely to me that they are the result of someone dividing the distance the camera could move into quarters, and then numbering the divisions 1-5 (instead of 0-4). A fanciful idea might be that it started before the camera was mounted on a geared track, when the quickest way to get a smaller field was to raise up the artwork by adding platforms to the table. This would justify starting with position 1 being at the camera lens (a field size of 0 width) and 5 being at the normal working distance, with 2,3 & 4 being the three-quarters, half, and quarter heights. Of these divisions 1 (touching the lens) was not for use, and 2 would seem to be to close for a satisfactory image – leaving 3,4& 5 as the workable sizes. Perhaps these were just fixed heights tat which the camera could be set.

I don’t know if this is anywhere near the truth, but some system must have been in use whereby these last 3 field sizes became enshrined in the working practice – to such a degree that when the geared column moveable camera took over it was preferable to resort to subdivisions of these familiar fields – 2¾, 3½, 4¼ etc. – rather than create a new, more flexible system of fields.

Isn’t there anyone out there with more information on how Disney’s field sizes came to be?

on 03 Aug 2012 at 1:56 pm 8.Stephen Worth said …

32 frames would be a bar if it’s an action scene on an 8x beat.

on 03 Aug 2012 at 2:05 pm 9.Stephen Worth said …

Peter, a measure would be four bars or 128 frames.

on 03 Aug 2012 at 2:09 pm 10.Stephen Worth said …

8x scene means it’s animated on an 8 frame beat. Scenes would be 8x, 10x or 12x, because these numbers divide up most neatly into frames. 8x is generally action, 10x is a standard walk, 12x is an amble, or doubled to 24, a slow scene.

Sorry to multipost. Keep seeing stuff to reply to.

on 03 Aug 2012 at 4:57 pm 11.Michael said …

Stephen, I hate to correct you but 12x is a natural walk cycle and almost all walks are done on 12x (a march beat,) I have this in writing from Grim Natwick handed down through Tissa David. I’ve also seen it from other animators includidng Milt Kahl and Frank Thomas. You can also measure any 24FPS film walk, and you’ll see they all hit the 12 beat. This is true on every one of the walk cycles I prepared from the opening of 101 Dalmatians, for example.