Books &Commentary 13 May 2013 05:36 am

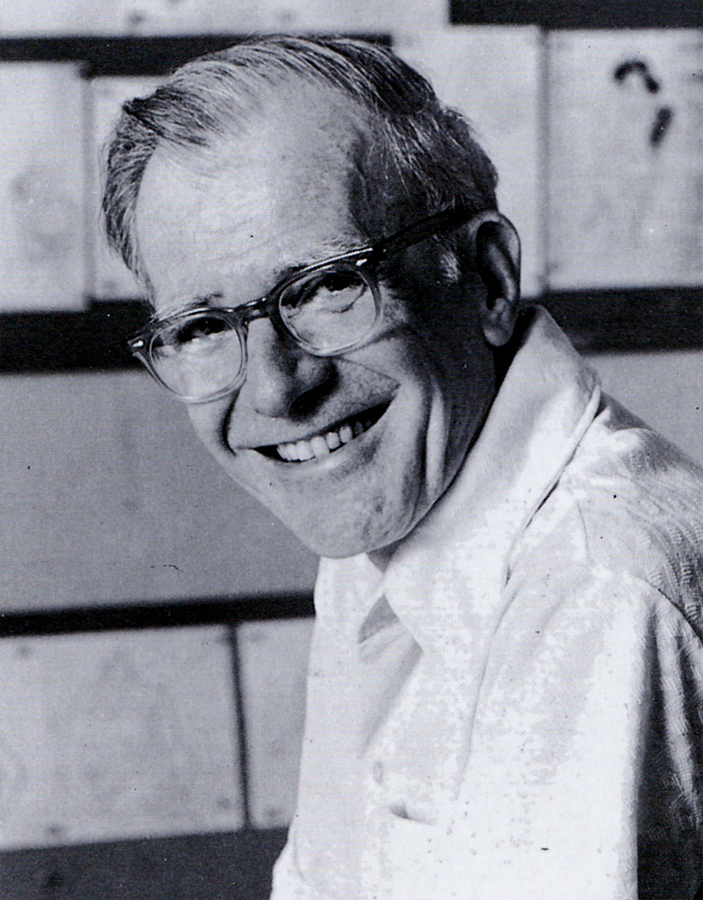

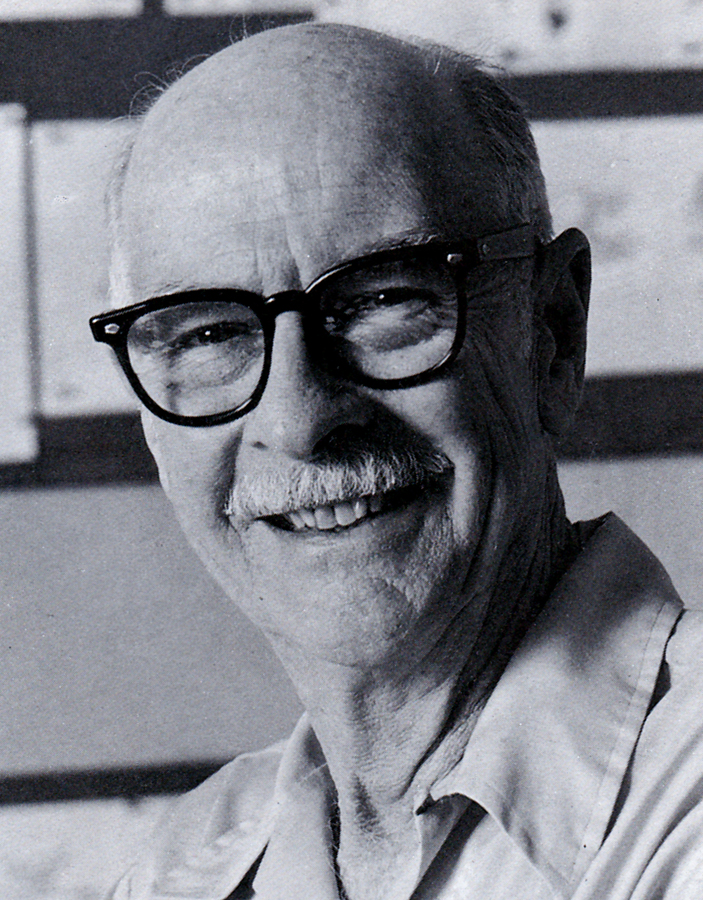

Illusions of Thomas, Johnston & Disney

- The Illusion of Life by Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston was first published in 1981. The book came out with a large splash and overwhelming acceptance by the animation community. It’s since remained the one bible that animation wannabees turn to as a source of inspiration and an attempt to learn about that business.

- The Illusion of Life by Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston was first published in 1981. The book came out with a large splash and overwhelming acceptance by the animation community. It’s since remained the one bible that animation wannabees turn to as a source of inspiration and an attempt to learn about that business.

I admitted a couple of weeks back that though I must have been one of the very first to have bought the book, I’d never actually read it. I spent hours poring over the many pictures and the extensive captions, but the actual book – I didn’t read it. I can’t say why, but this was my reality.

Then not too long ago, Mike Barrier wrote that he was not a supporter of the book and its theories, I wondered about that writing and decided to reconsider reading it. I knew I had to go back to find out what I’d stupidly ignored, so I started reading.

The book starts out with a lot of history of animation, something routine and expected from the two animators that lived through a good part of the story. As a matter of fact Thomas and Johnston were at the center of the history. It didn’t take long for the animation “how-to” to kick in. For the remainder of the book, using that history, the two master animators explained how and why Disney animation was done, in their opinions. They write about processes and systems set up at Disney during their tenure there. They write about theories and methods of fulfilling those theories. There’s a lot for them to tell and they’ve succinctly organized it into this book, as a sort of guide.

However, at two points they go wildly into a divergent path from the one that they started building. Their methods altered and, to me, seemed to be about the finances of doing the type of animation they did, rather than the reason. Impractical as those original theories were, I’d believed in the myth all those years to start changing now. So I want to review these two stances instead of outwardly reviewing the book. Besides it’s too long since the book has stood in its own royal space for me to pretend that I could properly review it.

The growth of animators at the Disney studio relied on a system wherein each of the better animators was assigned one character. Unless there was a minimal action by some external character, the one animator ruled over the character.

- Bill Tytla did Stromboli in Pinocchio. He did principal scenes of Dumbo in that film. He handled the Devil in Fantasia (as well as all his twisted mignons within those scenes.) Tytla worked on the seven dwarfs but was the principal animator of Grumpy.

- Bill Tytla did Stromboli in Pinocchio. He did principal scenes of Dumbo in that film. He handled the Devil in Fantasia (as well as all his twisted mignons within those scenes.) Tytla worked on the seven dwarfs but was the principal animator of Grumpy.

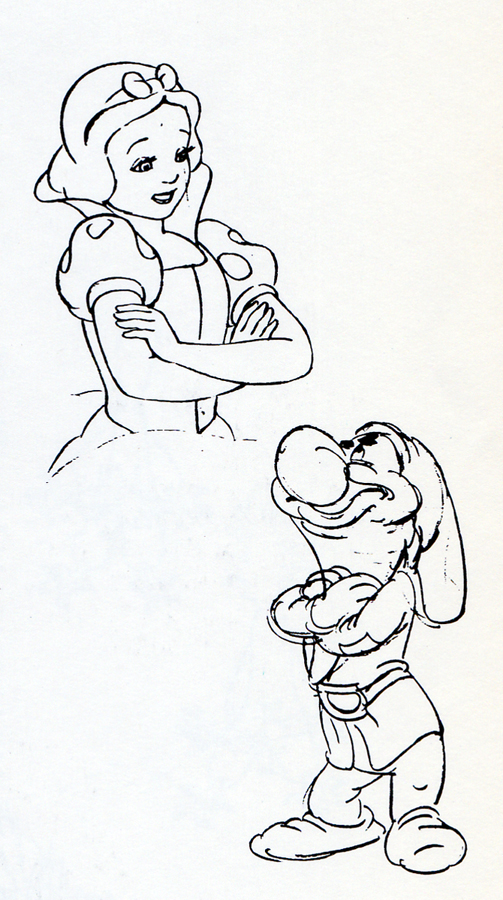

- Fred Moore also did the dwarfs in Snow White but seemed to focus on Dopey. He did Lampwick in Pinocchio and Mickey in The Sorcerer’s Apprentice.

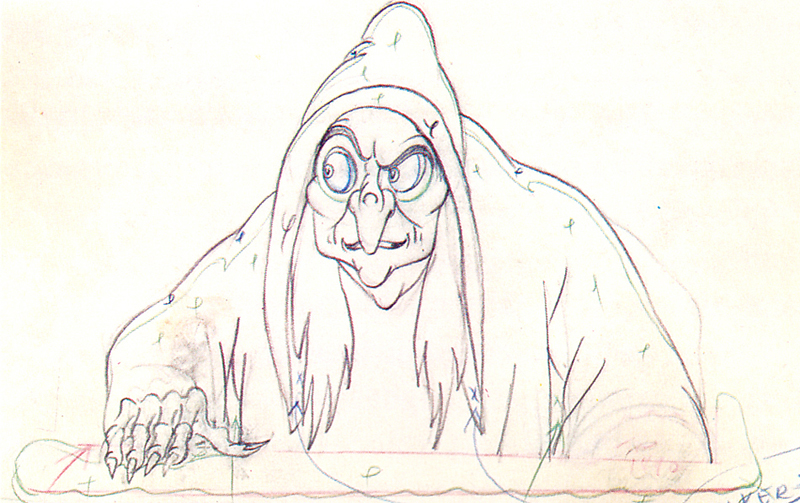

- Marc Davis started as an assistant under Grim Natwick on Snow White. He became the Principal artist behind Bambi, the young deer. He did Alice in Alice in Wonderland, Tinkerbell in Peter Pan, Maleficent in Sleeping Beauty and Cruella de Ville in 101 Dalmatians.

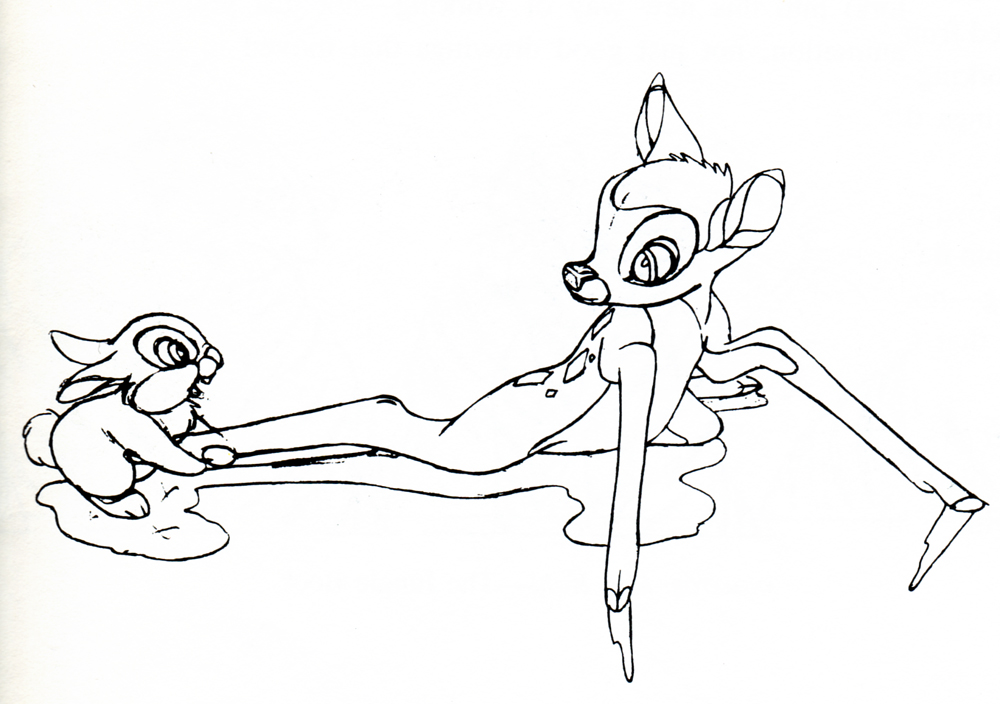

- Frank Thomas did Captain Hook in Peter Pan, the wicked Stepmother in Cinderella, Bambi and Thumper on the ice in Bambi.

- Ham Luske and Grim Natwick did Snow White. The two sides of her personality came about because of conflicts between the two animators. This was a way for Walt to complicate Snow White’s character; he employed two animators with different strong opinions about her movement. By putting Ham Luske in charge, he was sure to keep the virginal side of Snow White at the top, but by having Natwick create the darker sides of the character, Disney created something complex.

Many animators fell under these leaders’ supervision and tutelage, also working on one principal character in each film. This system was something they swore by and broadcast as their way of working at the studio. It would allow the individual characters to maintain their personalities as one animator led the way.

But as Walt grew more involved with his theme park and his television show and the live action movies that were doing well for the studio, things changed at the animation wing of the studio. It became clear, with the over budgeted spending on Sleeping Beauty and the new demands for a different look once xerography entered the picture in 1959. The rhythm and personality of the productions changed, and their methods of animation changed. Walt also sorted out nine loyalists to be his “Nine Old Men” thus dividing the animators into groups, a hurtful way of setting up competition among the animators. ________________________Kahl, Davis, Thomas, Walt, Jackson, Johnston seated

But as Walt grew more involved with his theme park and his television show and the live action movies that were doing well for the studio, things changed at the animation wing of the studio. It became clear, with the over budgeted spending on Sleeping Beauty and the new demands for a different look once xerography entered the picture in 1959. The rhythm and personality of the productions changed, and their methods of animation changed. Walt also sorted out nine loyalists to be his “Nine Old Men” thus dividing the animators into groups, a hurtful way of setting up competition among the animators. ________________________Kahl, Davis, Thomas, Walt, Jackson, Johnston seated

Thomas and Johnston get to justify this

in their book.

Let me read a section from the book to you:

- “Under this leadership, a new and very significant method of casting the animators evolved: an animator was to animate all the characters in his scene. In the first features, a different animator had handled each character. Under that system even with everyone cooperating, the possibilities of getting maximum entertainment out of a scene were remote at best. The first man to animate on the scene usually had the lead character, and the second animator often had to animate to something he could not feel or quite understand. Of necessity, the director was the arbitrator, but certain of the decisions and compromises were sure to make the job more difficult for at least one of the animators.

“The new casting overcame many problems and, more important, produced a major advancement in cartoon entertainment: the character relationship. With one man now animating ever character in his scene, he could feel all the vibrations and subtle nuances between his characters. No longer restricted by what someone else did, he was free to try out his own ideas of how his characters felt about each other. Animators became more observant of human behavior and built on relationships they saw around them every day.”

The question is, now, what are we to make of this statement? Do Thomas & Johnston mean for us to believe that they do more than the single character per film? Does it mean that, like all underprivileged animators everywhere, they now receive scenes rather than characters? Are they trying to tell us that the old, publicized method of animation they did during the “Golden Days” no longer exists?

The question is, now, what are we to make of this statement? Do Thomas & Johnston mean for us to believe that they do more than the single character per film? Does it mean that, like all underprivileged animators everywhere, they now receive scenes rather than characters? Are they trying to tell us that the old, publicized method of animation they did during the “Golden Days” no longer exists?

To be honest I don’t know. Also when are they talking about? At the start of the Xerox era? In the days since Woolie Reitherman has been directing? Do they mean ever since they’ve retired and started writing this book?

Let’s go back a bit.

- In 101 Dalmatians, Marc Davis did Cruella de Vil. That’s it. That’s all he was known for in that film. Oh wait, there were a couple of scenes where he did the “Bad’uns,” Cruella’s two sidekicks. He did these ging into or out of a sequence. In Sleeping Beauty (if we’re going back that far) Davis did Maleficent. Oh, he also did her raven sidekick.

- Milt Kahl did Prince Philip in Sleeping Beauty – and every once in a while his father. He did key Roger and Perdita scenes in 101 Dalmatians. He did Shere Khan in The Jungle Book.

- Milt Kahl did Prince Philip in Sleeping Beauty – and every once in a while his father. He did key Roger and Perdita scenes in 101 Dalmatians. He did Shere Khan in The Jungle Book.

Kahl also seems to be the go-to-guy when they’re looking to have the character defined. The closest thing to Joe Grant’s model department in the late Thirties. If you weren’t sure how Penny might look in a particular scene, you might go to Kahl who’d draw a couple of pictures for you. But that was Ollie Johnston‘s character. You’d probably go to him first, but Johnston would go to Kahl if he needed help.

Kahl also did Robin and some of Maid Marian in Robin Hood. I could keep going on, but let’s take a different direction.

Look at one of Thomas’ greatest sequences, the squirrels in the tree. Starting with Seq.006 Sc.23 and almost completely through and ending with Seq.06 Sc.136 Frank Thomas did the animation. That’s a lot of footage. Yes, that represents four characters: Merlin and Wart as squirrels, as well as the older and younger female squirrels. He did the whole thing (and it’s one of the most beautifully animated sequences ever.)

Look at one of Thomas’ greatest sequences, the squirrels in the tree. Starting with Seq.006 Sc.23 and almost completely through and ending with Seq.06 Sc.136 Frank Thomas did the animation. That’s a lot of footage. Yes, that represents four characters: Merlin and Wart as squirrels, as well as the older and younger female squirrels. He did the whole thing (and it’s one of the most beautifully animated sequences ever.)

But when he was done with that and needed work, he didn’t stop on this film; he also did a bunch of scenes in the “Wizard’s Duel” between Merlin and Mad Madame Mim. Another big chunk.

Hans Perk has done a brilliant service for all animation enthusiasts out there. On his blog, A Film LA, he’s posted many of the animator drafts of feature films. You can find out who animated what scenes from any of the features.

However as Hans posts the batches of sequences, he gives little notes about what we’ll find when we open the drafts. In my view, Hans’ notes are also a treasure.

You can read remarks such as, “Masterful character animation by Milt Kahl and Frank Thomas, action by John Sibley and a scene by Cliff Nordberg.” That seems to tell us everything.

In Sleeping Beauty we can read, “This sequence shows, like no other, the division between Acting and Action specialized animators. Or at least it shows how animators are cast that way. We find six of the “Nine Old Men”, and such long-time Disney staples as Youngquist, Lusk and Nordberg, each of them deserving an article like the great one on Sibley by Pete Docter.”

Or in The Rescuers we read, “Probably the most screened sequence of this movie, the sequence where Penny is down in the cave was sequence-directed by frank and Ollie. They would plan their part of this sequence in rough layout thumbnails, then continue by posing all scenes roughly as can be seen in this previous posting.

“They relished telling the story that Woolie told them the animatic/Leica-reel/work-reel was JUST the right length, and when they posed out the sequence and showed it to Woolie, he said: “See? Just as I said: just the right length!” They kept to themselves that the sequence had grown to twice the length!”

The work, right to the retiring of all of the “Nine Old Men,” would seem to me to prove that these guys, regardless of whether they added one or two other characters to the scenes, did, in fact, take charge of the one starring character.

The work, right to the retiring of all of the “Nine Old Men,” would seem to me to prove that these guys, regardless of whether they added one or two other characters to the scenes, did, in fact, take charge of the one starring character.

This continues past the retirement of all the oldsters: Glen Keane animated the “beast” in Beauty and the Beast. He animated Tarzan in Tarzan, Aladdin in Aladdin, Ariel in The Little Mermaid, and Pocahontas in Pocahontas. Andreas Deja animated Jafar, the Grand Vizier in Aladdin, Scar in The Lion King, Lilo in Lilo and Stitch, and Gaston in Beauty and the Beast. Mark Henn animated Belle in Beauty and the Beast (from the Florida studio), Jasmine in Aladdin, young Smiba in The Lion King, and Mulan and her father in Mulan.

Need I go on? What are Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston talking about in their book? I’m confused.

I have a lot left to say about this book, much of it good, but next time I want to write about something else that confuses me with another somewhat contradictory statement in the book.

This has gotten a bit long, and I have to cut it here.

on 13 May 2013 at 9:19 am 1.Luke said …

“Out of Necessity, the director was the arbitrator..”

YES! That’s what a GOOD director does! The biggest problem with Disney animation of that era was the animators becoming directors of their own sequences. They lost perspective, and the animation became more important than the story. Walt himself was probably to blame for this debacle, as he didn’t really mentor or train up new directors, other than to respond to his wishes. An impossible job when his attention was so frayed and his health failed.

Still, a strong directors hand with strong storytelling skills was what the animators needed most. But they were reluctant to relinquish the control they’d gotten. Originally, the “9 old men (a term that came later than the original use)” were a board to promote new talent in the studio—a portfolio review board of sorts.

I happen to prefer “animation by character,” but believe, as in Bambi, that animation of all characters can work–with strong direction, and animators who respect what a strong director brings to the table.

For over a decade, with animators rather than directors (and stories) driving the boat, the studio faltered. The stories created were weaker, and weakened further by only servicing the wants of the animators. The art of strong composition and layout were weakened by just providing a space for the animation to move around in.

The best thing to happen to the Disney Studios after the ’70′s was the influx of strong talent into the studio from CalArts and other places. And strong family films like Star Wars and Close Encounters. What a shame the studio itself was the last to notice it!

on 13 May 2013 at 9:32 am 2.Richard O'Connor said …

Great line: Walt also sorted out nine loyalists to be his “Nine Old Men†thus dividing the animators into groups, a hurtful way of setting up competition among the animators.

Even further, the beatification of Thomas, Johnson, Kahl, Kimball, Clark, Larson, Lounsbery, Davis and Reitherman (off the top of my head -I should try for Jeopardy!) does a huge disserve to artists like Babbitt and Sibley and Natwick and Luske who didn’t make the starting lineup for Walt-centric reasons. It’s funneled into a thoughtless mystification by popular media and many novice animators.

It’s been a long while since I’ve read the book, but I recall enjoying it very much. As mixture of memoir, how to, and coffee table book it scores an neat hat trick (to use two sport metaphors in one comment).

on 13 May 2013 at 10:40 am 3.Roberto Severino said …

To this day I’ve never read The Illusion of Life before, but had always heard that it contained some propaganda in there about Disney while simultaneously offering good animation advice and an insight of how the Disney studio actually worked. Maybe I should take a look at it soon and check it out at my local library.

on 13 May 2013 at 12:19 pm 4.Milton Gray said …

I suppose I’ll be the odd man out here by saying that I’ve never liked the text in The Illusion of Life. To me it is uniformly vacuous and shallow, and offers practically no insight into the thinking that went into the best of the Disney animated films. I’ve seen much better analyses and insights in other books on the subject. For the first several chapters, I initially thought, well, Thomas and Johnson were never storyboard or layout artists, so maybe they just got a superficial overview by talking briefly to other artists, but the chapter on animation should have some major insights. But no, not there either. For example, on the subject of character walks, all they said was, “Put personality into the walk.” This in spite of the fact that the studio spent years in the 1930s analyzing real human walks, so that the actions could be understood in depth and detail by the animators. But not a word about that in the book. For me the illustrations, which are fantastic, are the only good things in the book.

on 13 May 2013 at 12:38 pm 5.Liim Lsan said …

They could be talking about the way that before the war, when two animators shared a sequence, the one with the inciting action would take the first stab at it, and the other would react to his work (it would kinda shift around) – but after the strike, when such sequences were shown, the animator of the primary character would just draw the whole damn thing (he would probably get poses or model help from the animator of the other character, but he would draw the character in his own scenes himself).

I don’t know how much of the between-animator infighting was due to Geronomi’s philosophy of worker conflict and how much was just due to the temperament of the animators themselves. “Oh, Kahl doesn’t think about the acting.” “Frank only says that because he can’t draw.” “Nordberg is just WAY TOO DAMN LOOSE.” The bickering didn’t spill over into personal life, so it seeped into the working environment.

The ‘Working Units’ idea (Mike Barrier said it better than I ever could) was Milt Kahl’s plea to relieve his boredom – it was used on Bambi to mediocre results (great film, but the animators are too obviously constructing the character’s motions in a few more scenes than it needs). Throughout the fifties, what happened was that the ‘Nine Old Men’ would go over things on their own time (hence the inbreeding and ‘committee meeting’ vibe to the films). What I find interesting is the way that in the fifties and sixties, when Walt couldn’t be the Svengali he wanted to be because of the demands on his time, various people in the studio were elevated to authoritative positions for specific pictures. Mary Blair, Eyvind Earle, Ken Anderson, Bill Peet, Thomas/Johnston/Kahl… some left son after, some just sank back into the background. The films were chugging along without a conductor for their entire run.

Also? Not once in the entire fucking book do they mention the strike; nor is Art Babbitt especially noted. You can tell where their sympathies lay.

on 13 May 2013 at 12:47 pm 6.Tom Minton said …

In September of 1977, on a visit to the Disney studio Animation building when Reitherman, Johnson, Thomas, among other legends, were still working, I asked Disney production manager Ed Hansen to clarify an amazing statement he’d just made that the only ‘real’ animation ever done was Disney animation. After having seen Richard Williams “A Christmas Carol” and “Raggedy Ann and Andy,” I asked Hansen ‘What about Richard Williams?’ Hansen replied, deadpan, “Well, that’s animation. But it isn’t DISNEY animation!”

on 13 May 2013 at 1:40 pm 7.Stephen Worth said …

I don’t understand folks talking about Illusion of Life as a “how to” book. It’s a history book told from the point of view of Frank and Ollie.

By the way, although Luske was credited as supervising animator on Snow White, Grim told me that he had very little interaction with him. He just cranked out the footage with his own assistants working under him… Davis, Novros, etc. At one point he had nine assistants just to keep up with his footage.

After Snow White was completed, Grim looked at the draft and saw that Luske’s name had been put on scenes that he had animated. Grim did the lion’s share of animation on the character, and Luske got the credit and a massive bonus. That was a big reason why he left Disney instead of completing Sorcerer’s Apprentice, which he had started doing test scenes for.

on 13 May 2013 at 1:45 pm 8.Stephen Worth said …

One other thing not many people know… Walt was the one who came up with the Illusion of Life project. But he didn’t pick Frank and Ollie to write the book. He wanted Les Clark to write it. Unfortunately, Clark died and Frank picked it up. If Clark had written the book, it probably would have had a much more balanced view of the early history of the studio. Frank and Ollie tend to gloss over things that happened before 1938.

on 13 May 2013 at 4:05 pm 9.Roberto Severino said …

The extra background on this book from Milt Gray, Steve Worth, and Tom Minton was very insightful. Thanks, guys! I sense there might have been a degree of dogmatism and egoism coming from both Frank and Ollie for whatever reason. I would have also loved to see what Les Clark’s version of The Illusion of Life might have been like. Maybe it would have improved our understanding of Disney history.

on 13 May 2013 at 5:10 pm 10.Joel Brinkerhoff said …

I have the first edition of the book with all the studio history and incidental antics which I though gave a flavor of what the studio may have been like. I noticed drawings out of order in a few sequential animation spreads and made correct numbering in pencil on my copy.

There was another slimmer version that was supposed to be more nuts and blots without the studio history but I’ve not bothered to look into it.

I just enjoyed it for the lush artwork.

on 13 May 2013 at 5:15 pm 11.Joel Brinkerhoff said …

I forgot to mention the lack of credit due the assistant animators. At least Bill Tyla is on record as acknowledging the importance of these dedicated artists who made the nine old men look so good here:http://afilmla.blogspot.com/2009/03/tytla-speaks-on-forms-vs-forces-i.html

on 13 May 2013 at 8:06 pm 12.Mark Sonntag said …

It is interesting to think about the book and yes a lot of time is spent talking about work Frank and Ollie did do rather than focus on early Disney animation. As a memoir that’s understandable. That said, it would be fascinating to see a book or a two part book which really goes into the history of the animation process in all departments from say Oswald to the 90s. In my opinion, all the advancement happened not under the Nine Old Men but before under Babbit, Ferguson, Moore, Tytla, Clark etc. At best the Nine Old Men refined it, but for me those films from the 50s and 60s don’t have as much charm as the earlier “less refined” stuff.

on 13 May 2013 at 8:07 pm 13.Michael said …

As I wrote with your last comment, Stephen, you have to reread this book. It is NOT a history book. It is only about HOW to animate and Why the Disney people do it the way they do. They talk about the history a bit, but it is only in service of talking about how and why the Disney animation is done.

on 13 May 2013 at 8:38 pm 14.Alfred von Cervera said …

I have read this book twice, and I would like to share my opinion about it. I think it is more a way to narrate Disney’s animation from a very particular point of view, one where two people seem to be real important for the studio: Frank and Ollie himself. That’s the only way you can explain how they dedicate so little to films like Sleeping Beauty and 101 Dalmatians and so much to Robin Hood, The Rescuers and Snow White. If you analize the illustrations and animation examples, more than 60 percent of the footage is from Frank Thomas or Ollie Johnston assignments. The second animator with most animation is Milt Kahl. There is so little on Chernabog and almost nothing on Dumbo, when they dedicate almost two pages for the Lady and the Tramp spaguetti sequence. I think it is a good book, but I also think this is the begnning of the mythification of the 9 old men. Besides, it’s the only place where you find a consistent narrative relating to this joke Walt Disney made a long time ago (it is funny to watch the disney documentaries on each DVD and see how they always attempt to talk about the whole nine men, and always forget about Les Clark and sometimes forget to mention what John Lounsbery did. Maybe my opinion is biased, but after watching the DVD documentary “Frank and Ollie”, you start to think those guys were trying really high to lobby their importance on animation history.

on 13 May 2013 at 10:05 pm 15.Dan said …

I know very little about the book other than what has been mentioned here, on Mike Barrier’s site, and in a rather scathing Amazon review (which has seemingly been deleted) by Thad Komorowski, who noted the lack of mention of any of the ‘bombs’ (e.g., Alice in Wonderland, The Three Caballeros) put out by the studio, although there are plenty of references to animation from Robin Hood and the Rescuers apparently. It’s possible that Thad reviewed a version of the book without the drawings of the door knob from Alice, as there are apparently two editions.

on 13 May 2013 at 10:39 pm 16.Thad Komorowski said …

^ Yes, guilty as charged. I’ve reposted a few reviews in the past, and I’m working on a fresh look, which was prompted by Michael stating he had never read IoL and was going to be reviewing it himself. A decade later, I don’t really care for much of what I’ve reread now. It’s revealing that one of the heights of Disney acting and filmmaking, DUMBO (which Thomas and Johnston didn’t work on), isn’t even worthy of a sneer.

on 14 May 2013 at 8:19 am 17.Hans Perk said …

Thanks for the nice words, Michael! In September 1981, when The Illusion of Life came out, John Canemaker was so kind as to send two copies to Holland, one for my mentor Børge Ring and one for myself. We devoured the book immediately, as before it the only book dealing extensively with the techniques used in animation was Preston Blair’s first book. Most other books on animation were history books – or about camera work and field guides.

Børge noted that he was a bit irritated by the fact that he spent a lifetime learning this stuff – and now anyone could just read it here. The about 35 years I have been in the animation business taught me that these things are not learned by reading, but by doing. The book has HELPED me learn, and has helped many people in the business that I know, but really–nobody has ever become an animator by just reading about it.

There is a trap that many have fallen into, that may not be obvious at first: for those who do not animate out of their own emotions, animation can become formulaic and you may be able to see hints of Milt or Frank’s greatest hits in totally wrong context. As such, the advice can only be: know the principles, know the rules, but also know when to break them. And you’ll find that Frank and Ollie are writing this themselves. Breaking the rules is part of the principles. Thus, I advice all to not only read it, but to understand it.

That goes for ALL in the entertainment business, not just for animators. All the great tips on how to build emotions through layouts should hold up in paintings or in live action as well. Frank and Ollie’s original subtitle, nixed by their publisher, was “A theory regarding the presentation of amusement,” and I feel that that pretty much covers it. But some will always only see the history part of the book as valuable. They will likely not understand the lessons to be learned.

Because of this they fought to have a paperback version published, which the publisher wanted to only to contain the history part. They convinced him to make it a text book for the “making of,” but I believe it was only published once, in the mid 80s. Though it is only part of the “whole” book, it stands as a testimony for what they intended to achieve: passing on the flame of Disney animation, a form of animation that values the ILLUSION of life above just movement or graphics, making it possible for the audience to identify with the characters in the films. There is no denying that they pulled it off in their films. With any flaws that the book may may have, it will remain my animation bible, and I cannot see that change any time soon.

on 14 May 2013 at 9:14 am 18.Teodor Ajduk said …

I love and suport the comment from mr Hans Perk.

This is why I do not like at all ‘The Animator’s Survival Kit’…I’d stubbornly refused to draw every frame in 60 FPS.

on 14 May 2013 at 2:57 pm 19.Tom Minton said …

Frank and Ollie’s “A theory regarding the presentation of amusement” would have made the ideal subtitle. But I can see why the publisher nixed it: it destroys all notions of Disney magic by accurately explaining the ‘illusion of life.’

on 14 May 2013 at 5:24 pm 20.Mark Sonntag said …

I agree Hans, when I started in animation IOL was my textbook. I found other books at best rudimentary, at least in giving the ground work. But as you said, the real magic, of all art, is the emotion and getting it across. That’s a very personal thing and can’t really be taught in a traditional sense. I did find the IOL encouraging that.

on 15 May 2013 at 2:26 pm 21.Stephen Perry said …

Fred Moore animated very little if any of Mickey in the Sorcerer’s Apprentice, according to the final draft. But he must’ve done a lot of drawings for the other animators, maybe?

on 15 May 2013 at 9:58 pm 22.RodneyBaker said …

Those that pigeon hole Frank and Ollie as being self centered in their treatment of the book or skipping important areas of Disney animation should read the introduction… in the book itself… wherein they explain, apologetically, why the book contains ‘too much’ of their own work and too little of other artists and animators. While they would have preferred it otherwise, in the end they had to write a book based on their personal experience and could only complement that with the references that were then available.

As many others have noted, ‘The Illusion of Life’ is a tough read… I haven’t been able to read it all the way through either… but it does help to read at least some of it in order to gain insight into the minds and perspectives of the authors.

on 16 May 2013 at 1:28 am 23.Scott said …

There’s little in Natwick’s Snow White animation that didn’t need some help. Less in the drawing than in the animation. There’s little in Natwick’s work elsewhere–before or after–that doesn’t lend credence to this likelihood. The hand of a more assured, and controlled animator –such as Lusk–surely tied all Natwick’s work together. Hence the shared credit on Natwick’s scenes.

on 16 May 2013 at 7:50 am 24.Michael said …

I not only disagree with you but Walt Disney disagreed with you. Natwick brought a dark side to Snow White against the thoughts and wishes of Ham Luske. Luske wanted only that innocent virginal girl, and that was an innocent view, in itself. By having the counter of Natwick’s version of the character, Disney was able to create a fully rounded character of her. This was most definitely intentional on the part of the man who was creating a masterpiece. With only Luske, he would have had something less.