Category ArchiveBooks

Books &Commentary &Layout & Design 06 Dec 2011 06:37 am

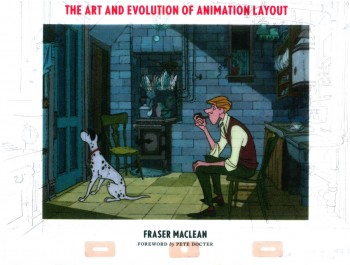

Setting the Scene – Book Review

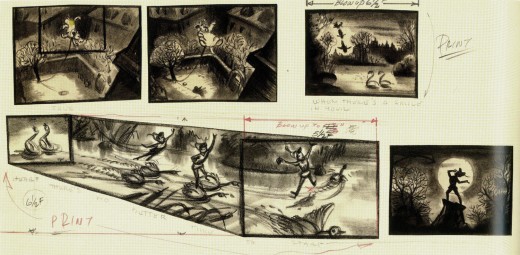

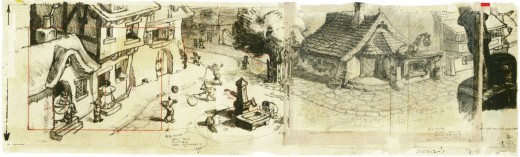

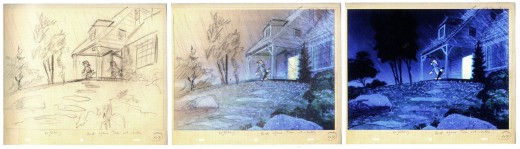

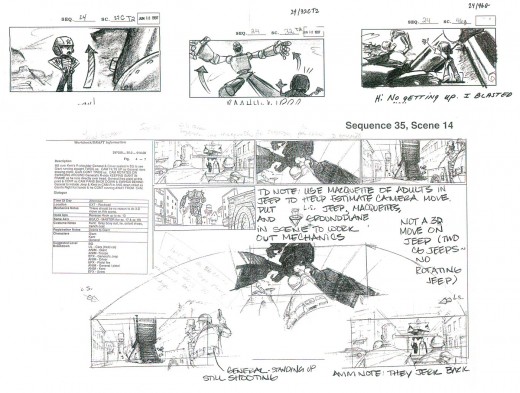

- Setting the Scene: The Art and Evolution of Animation Layout is a beautiful new book by Fraser MacClean. This is a stunningly attractive book with a great number of illustrations going all the way back to Winsor McCay right up to recent Dreamworks films.

- Setting the Scene: The Art and Evolution of Animation Layout is a beautiful new book by Fraser MacClean. This is a stunningly attractive book with a great number of illustrations going all the way back to Winsor McCay right up to recent Dreamworks films.

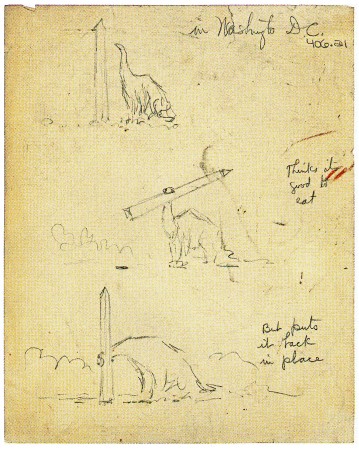

The book talks about the history of the layout artist and gives plenty of examples from the past to the present, 2D to CG. It addresses how McCay did his films, through the silent animation era, past the Golden Age of animation, right up to the present day’s more complicated methods for computer graphics. It’s a wonderful and heavily researched book with an enormous number of illustrated examples.

A Winsor McCay LO for Gertie

Original drawn layouts for the likes of One Hundred and One Dalmatians, Chuck Jones/Maurice Noble shorts, Betty Boop shorts, Gulliver’s Travels and The Thief and the Cobbler dress this book giving it a strength that none of the words could offer. Storyboard sequences for Peter Pan, The Rescuers Down Under, Cinderella or Song of the South help get any point across in the most visual way possible.

The book is somewhat dense and took me quite some time to go through it carefully. The material is so interesting, though, that I was ready to give it all the time necessary. Every time you turned a page there’d be another beautiful illustration that just took a lot of time to study.

A planning drawing for the great multiplane scene in Pinocchio

from B&W to color

Johnn Didrik Johnsen’s LO for Tom & Jerry “Puppy Tale” (1954)

Probably my only complaint about this book would be that the type is small and harder to read. At times even the illustrations are a bit smaller than I’d like. This, of course, is because anything larger would require greater printing costs and make the book too expensive. So, I’d rather have what sits in my hand than something I’d think hard about buying. As it is, the book is a must own for animation enthusiasts, and there’s a lot to learn for anyone interested in the process of animated film making. I wouldn’t hesitate to wholeheartedly recommend this book to anyone.

Brad Bird’s planning sketch for “The Iron Giant”

I could keep pulling more and more illlustrations from this book. They’re all unique and totally illustrate what the author is talking about at the moment. And they’re all gorgeous. You have to take a look at this book. It’s is another beautiful book from Chronicle Books. They are batting a perfect score, as far as I can see.

Art Art &Books &Comic Art &Illustration &John Canemaker &T.Hachtman 03 Dec 2011 07:45 am

Paul & Sandra and John and Tom and Bill

- This past Thursday night, Paul and Sandra Fierlinger presented an hour’s worth of their latest project at Parson’s School. The film, Slocum at Sea with Himself, tells the story of the first person to have sailed SOLO around the world.

- This past Thursday night, Paul and Sandra Fierlinger presented an hour’s worth of their latest project at Parson’s School. The film, Slocum at Sea with Himself, tells the story of the first person to have sailed SOLO around the world.

The film was a work in progress in every sense of the phrase. It started in full color, included scenes over final Bgs that weren’t colored and had other scenes that were pure pencil test. The sound was predominantly music composed and performed by the brilliant Shay Lynch. (You may know his music from the many films he did for Jeff Scher.) Yet, it all stood with a great dignity as a strong piece.

The film was full of potential to be even greater than their last feature, My Dog Tulip. Imagery was stunning and beautifully designed and animated (as usual from this team). It was a real treat seeing the work in progress, and it was easy to fill in the gaps. The movie takes place almost completely on water, and it’s amazing the effects they’ve achieved in animating such a difficult project. I was wholly taken by it.

As monumental as the screening was – truly inspirational, the talk Paul gave in advance was thought provoking. They are making the film with their own money and planning to release it online in short segments. All told the feed would take about six months to receive the entire feature. To buy these feeds, which will be built into a website that would constantly change for each segment, will cost about $30 in total. They’re hoping for a built-in audience of boaters and leisure craft enthusiasts around the world. Slocum is a well-known story to these folk, and the likelihood that they’d have interest in the subject is great.

Theirs is a provocative idea for distributing the film, and the business model Paul presented seemed original and probably a successful one. It will take some time before the feature is finished, but I’ll be watching closely to see how successful they’ll be. I’d bet on them, too.

There is no doubt of the love they’re pouring into this project. Take a look at these stills:

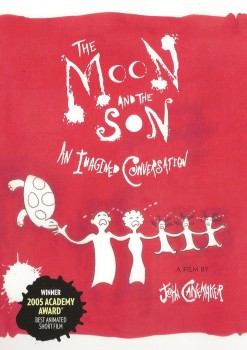

- The Moon and the Son: An Imagined Conversation, John Canemaker’s animated short, is now available in a special edition DVD. This powerful and moving film, which has won both the Academy Award and the Emmy Award, explores the difficult emotional terrain of father/son relationships as seen through Canemaker’s own turbulent relationship with his father.

The Moon and the Son combines many different elements from John’s remembered versions of the facts, to the actual evidence of the life on screen: the trial transcripts, audio recordings, home movies, and photos. The original and stylized animation tells the true story of an Italian immigrant’s troubled life and the consequences of his actions on his family. The film features the voices of noted actors Eli Wallach and John Turturro in the roles of father and son.

The DVD includes the complete 28-minute film and the following bonus materials:

- A new documentary detailing the film’s creative evolution, influences and reception, with animation director/designer John Canemaker and producer Peggy Stern.

- The first rough cut (working title: “Confessions of my Fatherâ€) with original soundtrack

- A Photo gallery of production sketches, preliminary artwork and storyboards

I enjoyed thumbing through all the extras on this DVD. When the film was being made, John shared its progress with me at several stages. I’m intrigued with how much material was there in the development. As a long time friend with John, I felt I’d known some of the story over the years. But the film, and now the new material, give me larger insight to the full story. Spending time reading the storyboard (one of the extras) again – having seen the film several times – allowed me to see some of the background which shaped John’s quest to tell this story.

The DVD is available now on Amazon.

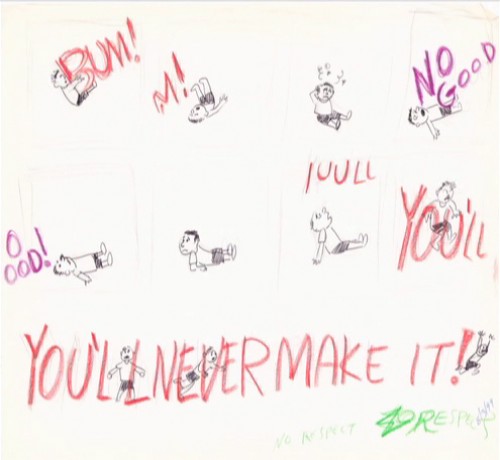

A somewhat Feiffer-like page within the storyboard.

A very “Canemaker” sketch that reminds me a bit of a Picasso sketch.

There’s lots more on the DVD.

____________________________________

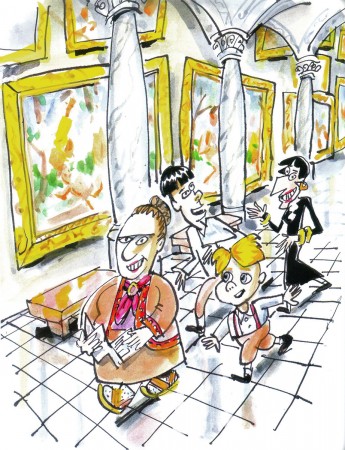

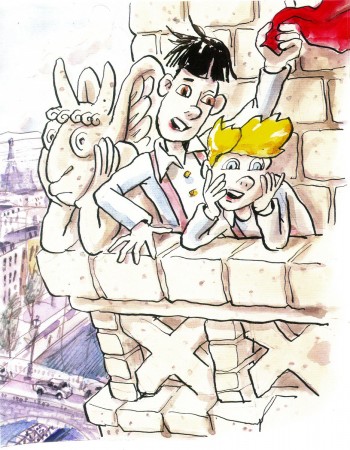

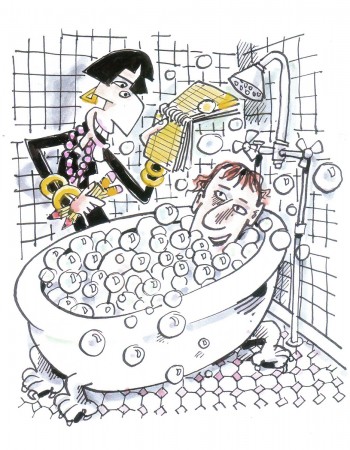

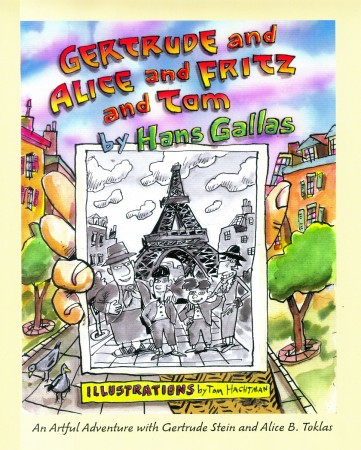

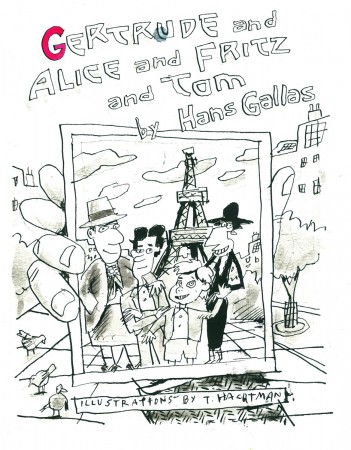

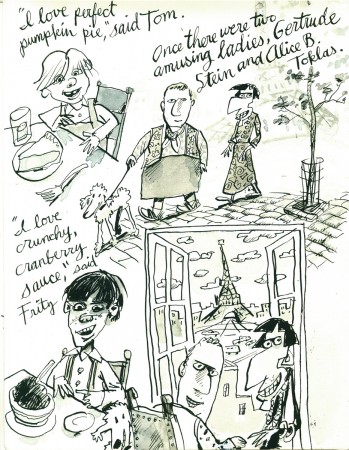

- Tom Hachtman has seen an unusual turn with his Gertrude and Alice characters. You’ll remember that he’d developed a comic strip, Gertrude’s Follies, built around Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas. A friend and admirer of the strip, Hans Gallas, has written a children’s book around Tom’s characters, and Tom illustrated the book. Now that book’s been published, and can be purchased from their site. Gertrude and Alice and Fritz and Tom is a charming account of what happens when Gertrude and Alice have to take care of a couple of young boys during their stay in Paris.

Here are some of the book’s exuberant illustrations.

The book’s cover

And here are some of Tom’s original sketches for the book.

Original sketch for the cover.

Très different from the final.

A preliminary sketch for a lot of pages

_____________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________

- Bill Benzon, on his blog New Savannah, has finally completed his treatise on Fantasia and has published it in a PDF form. You can download this here for a great read. 96 pages of intelligent discourse on the feature. This document contains his original, and shorter commentary on the Pastoral sequence. For his longer take on that sequence download this document.

Books &Commentary 29 Nov 2011 06:35 am

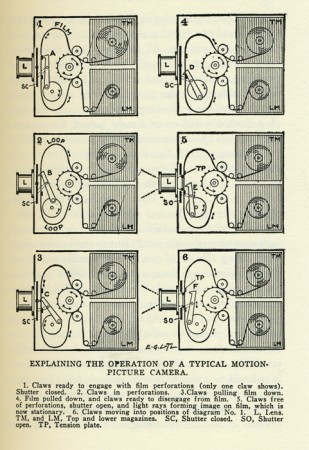

Overdue Review – The Motion Picture Cameraman

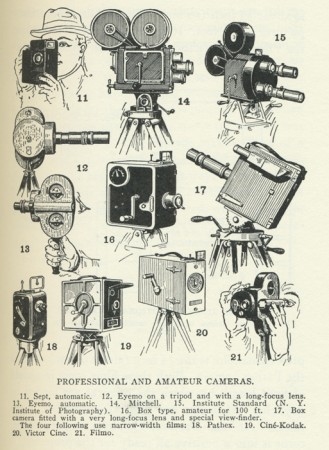

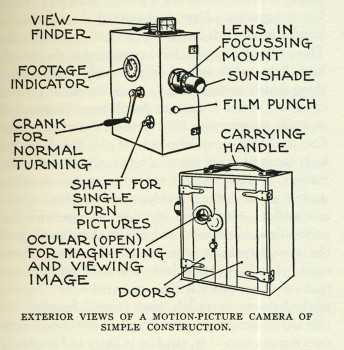

- A couple of weeks ago, I reviewed the E.G. Lutz book, Animated Cartoons. I was also intrigued by another of his many books, The Motion Picture Cameraman, and quickly ordered a copy from Amazon. This 1927 book is obviously dated, but like his earlier book, Animated Cartoons, it’s so filled with information that most of it has held up over the years. Of course, today everything is digital, so there’s no need for a lot of information about film and film stocks, but there’s still of lot to be learned for the aspiring motion picture photographer.

This is all illustrated by detailed drawings by Lutz, himself.

The book starts out talking about the camera. Lutz, at first, sticks to the simplest, the box camera, and moves on from there ultimately comparing and contrasting a number of different makes, at the time.

The simple box camera

The book offers lots of charts and details that are pertinent to the subject. Everything from filming outdoors “When subjects have a preponderance of red and yellow hues they require a large stop and a long exposure to procure any kind of result. In subjects where blue and violet prevail a smaller stop will do.” Naturally, there’s a chart analyzing daylight hours at different months of the year.

He has an entire chapter on shooting within a studio of the period: “A Motion-Picture studio is a huge structure with glass roof and sides in which artificial lights supplement daylight, or are used exclusively for the illumination.” Certainly, this is not what studios were even five years on. They would soon be doing color, and they would need to very carefully control the conditions for photography.

How quickly it all changed and how casually we shoot now with our digital cameras.

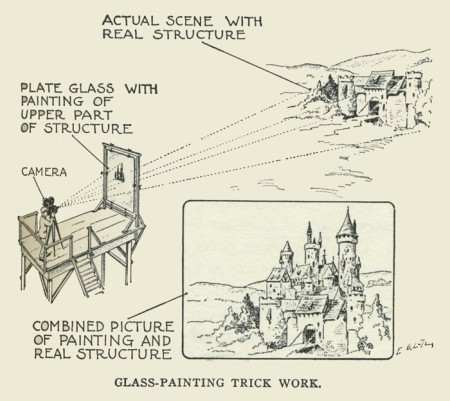

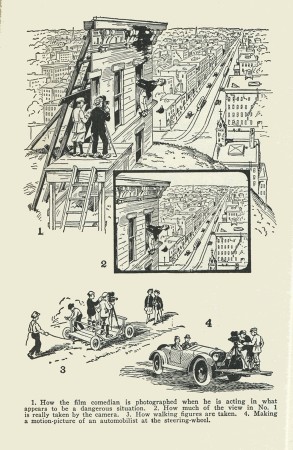

He has a chapter on effects photography covering everything from glass matte shots to split screen photography. Many of these effects are illustrated.

The glass matte shot explained in a very clear way

How people hang precariously

from clocks in silent films (see Hugo).

He has an entire chapter on how titling is done, and there’s another chapter on “‘One Turn, One Picture’ Work”, or as we call it “animation.” The “one turn, one picture” means that you crank the camera only once around to film one image. It took 16 cranks to shoot one foot of film, or one second in the silent pictures. Film ultimately went to 24 frames per second to accommodate sound photography.

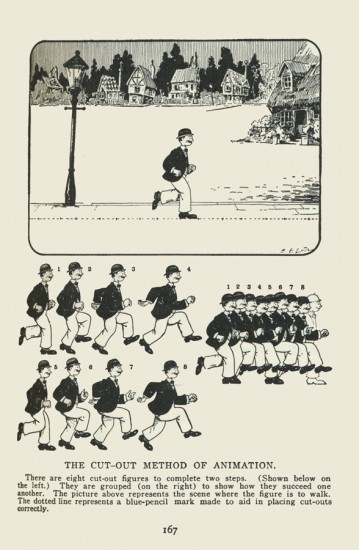

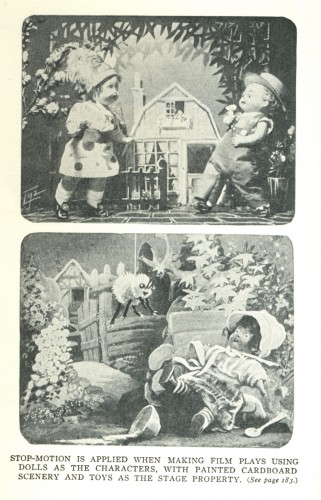

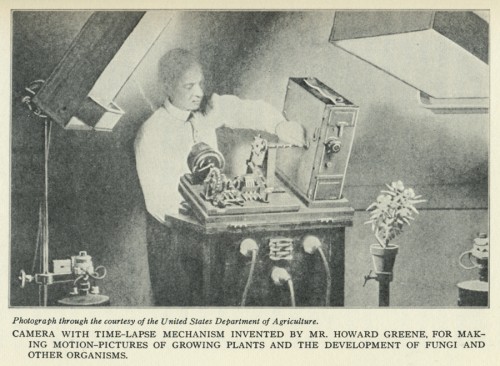

In that animation chapter, he analyzes the different types of animation from cut-out to stop-motion to time-lapse photography. It’s very succinct and well informed, as we might expect from the author of the first how-to book on the subject.

Puppets, prior to the ball and joint method

were just strung together with strong wire.

This man is shooting a time-lapse film although

it looks as though he were creating Frankenstein’s monster.

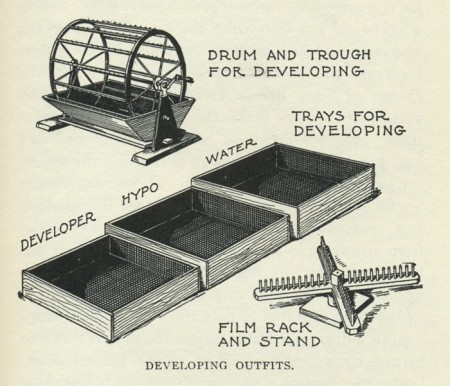

Ultimately, we even get instructions on how to develop the film. Fortunately, labs were created for that purpose and handle such an important part of the process today.

Equipment needed to develop your own film.

I guess the book seemed valuable for me because I have an interest in the process, both that of the past as well as that of today. I’m not sure everybody has that interest, but this book will serve you well and entertain if you do.

Books 22 Nov 2011 04:28 am

Hindu Deities

- In 2010, Pixar animator, Sanjay Patel had his book, Ramayana, Divine Loophole, published by Chronicle Books. This is a work of art, if ever there was one. There are more than 100 color illustrations mixed with B&W sketches and rough drawings in the book. The artwork is beautiful throughout the book illustrates the tale of the Rama’s adventures in loving detail.

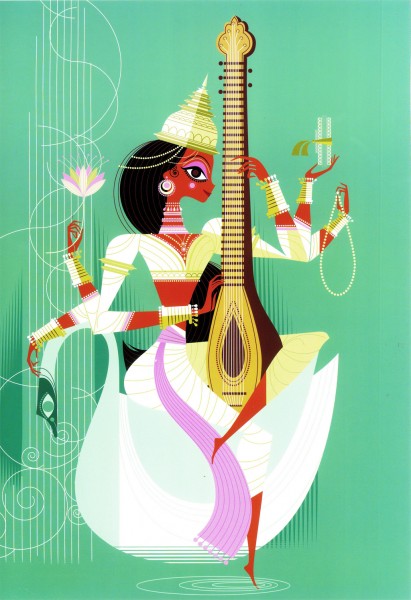

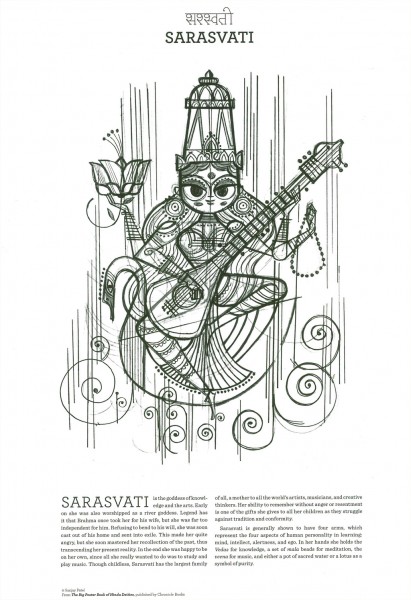

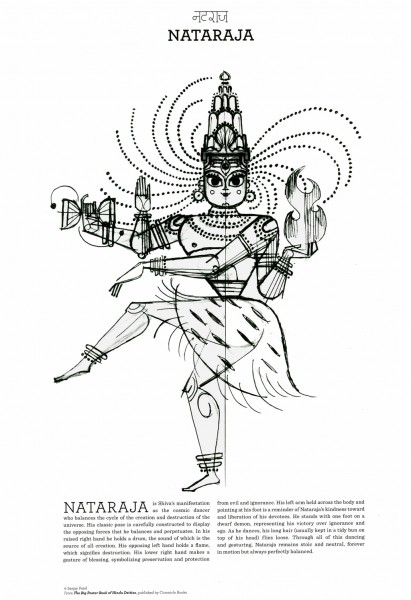

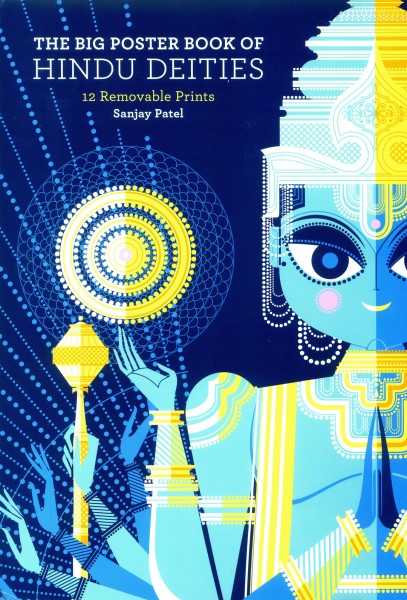

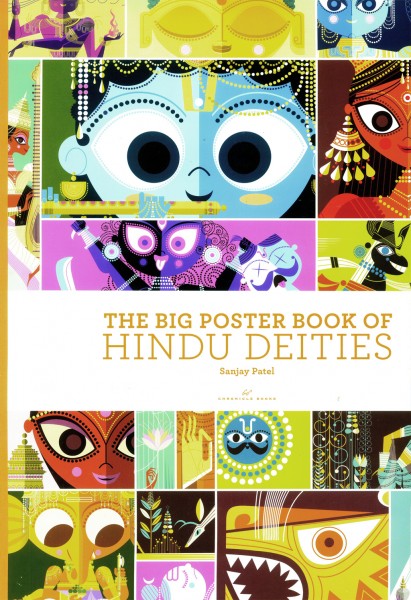

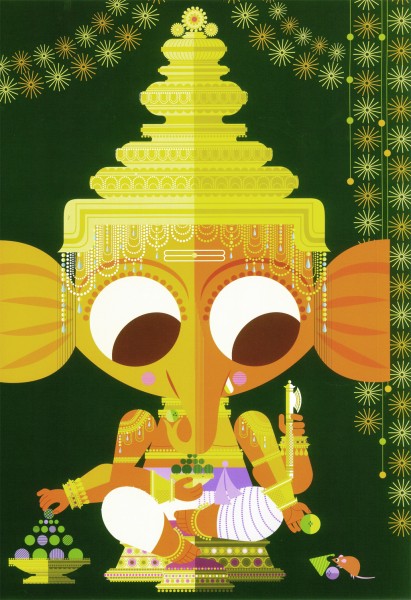

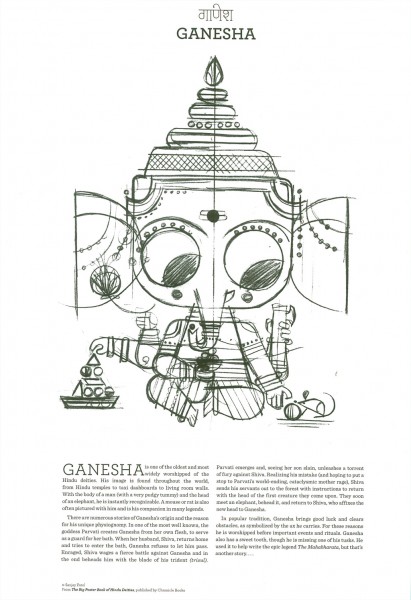

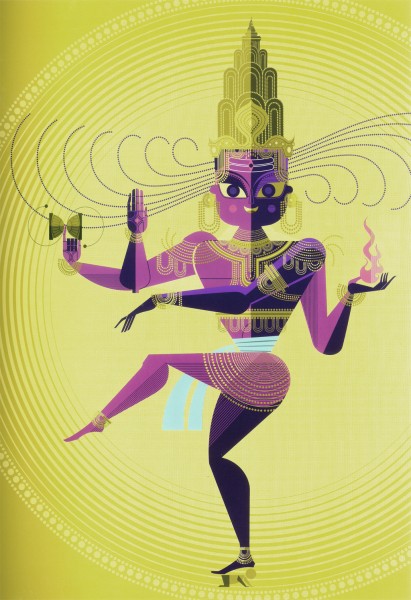

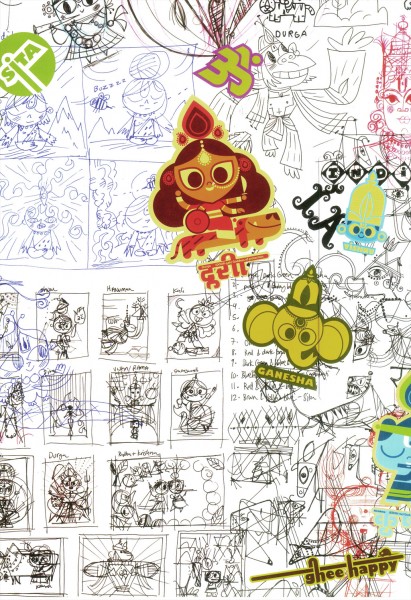

Now Mr. Patel has a new book, of sorts. The Big Poster Book of Hindu Deities features 12 color, poster-sized illustrations which can be taken out of the book and framed or left in bound form. They make up the body of this book/package.

Sanjay Patel is an animator and story artist working for PIXAR. He’s been involved in films from A Bug’s Life to Cars 2, including The Incredibles, Ratatouille, and Toy Story 2 and 3.

Patel’s illustration style is quite original and forceful. A strong sense of design, the colors and nuances of the book are very delicate, and Chronicle Books has done a wonderful job of capturing these in the printing and layout.

The outer cover is a sleeve which wraps around the bound envelope of a book.

The cover of the actual book, within the enveloping binding

gives a hint of the posters held within the volume.

Each illustration can be removed from the book and framed as a poster.

The back side of each page includes another sketched drawing

with a piece about the God/Goddess illustrated.

The printing of the illustrations is exceptional.

In scanning them, I had a difficult time trying to match the printing.

I did not succeed. The subtleties were too great for my scanner.

The inner cover of the bound book offers a look

at some preliminary sketches done for the tome.

The $25 book sells for $15.96 on Amazon and is quite large.

Books &Commentary 10 Nov 2011 06:45 am

Lutz

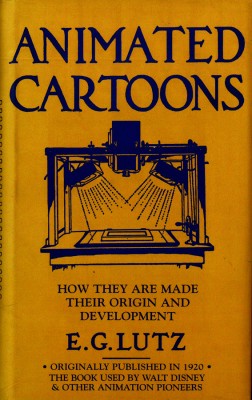

- This week, I posted a review of E.G. Lutz’ book, Animated Cartoons: How They Are Made, Their Origin and Development, and I commented that I have had this curiosity about who E.G.Lutz actually was. A quick Google search for biographical information comes up with nothing other than the Amazon listing of his books for sale and the references to him in other animation books.

It was a bit of a surprise to me to find that his singular animation book, published in 1920, is definitely not his best selling book. That would be Drawing made easy; A step by step guide to drawing for young artists. There are also another half dozen books he’s either written or illustrated.

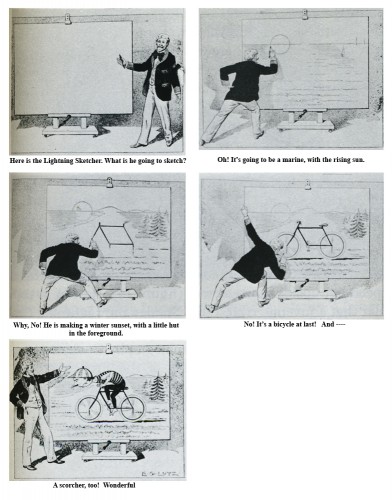

I decided, then, to look in all of the books I own. The best place to start was with Donald Crafton‘s book, Before Mickey. Sure enough, there was an illustration by Lutz that was done in 1897. It depicted the “Lightning sketcher.” These were the artists who appeared on stage in Vaudeville theaters sketching an image at “lightning” speed. Georges Méliès enjoyed doing this for a while, and J. Stuart Blackton put it on film. Lutz illustrated such an artist.

I’ve had to do a little retouching in photoshop to get

this image to read well. I retyped all the text there.

Crafton later quotes the Lutz book:

- The first book devoted solely to the craft was Animated Cartoons; How They are Made, their Origin and Development by former caricaturist Edwin G. Lutz. This book became the vulgate of modern industrial animation, canonizing the major studios’ practices. Its guiding philosophy was embodied in the statement that “of all the talents required by anyone going into this branch of art, none is so important as that of the skill to plan the work so that the lowest possible number of drawings need be made for any particular scenario.” Lutz illustrated the book with his own rather quaint drawings. He described peg registration, in-betweening, speech balloons, and studio organization, but curiously his description of cels was limited to their use as static overlays.

- Lutz’s book was a fountain of common-sense advice, such as limiting dialog so that films could be sold in foreign countries. Among its most important contributions were the detailed instructions for drawing perspective runs and other kinetic effects, which would grow increasingly visible throughout the 1920s, especially when combined with mobile and cycled backgrounds. Cycling, supposedly invented by Nolan, consisted of a sequence of eight drawings planned to match at the end of a cycle by making the first and eighth drawings identical. This effect may be seen in practically any 1920s studio production, but Paul Terry seemed to especially love it, With these and all the Other techniques explained in detail, almost anyone with the ambition could begin making animated cartoons. Of these neophytes, certainly the most ambitious reader of Lutz was Walt Disney of Kansas City—who, because he could not afford to buy it, checked the book out of the public library.

This, of course, is the story of how Walt Disney pored over the book slavishly to find out the tricks of the trade. Mike Barrier in his book, The Animated Man, describes this well:

- (Disney) was essentially self-taught as an animator; he wrote to an admirer many years later, “I gained my first information on animation from a book . . . which I procured from the Kansas City Public Library.” . . . According to its copyright page, Lutz’s book was published in New York in February 1920, the same month Disney joined Kansas City Film Ad, so he must have read it very soon after it was added to the library’s collection. He said of the book in 1956: “Now, it was not very profound; it was just something the guy had put together to make a buck. But, still, there are ideas in there.”

- As elementary as the Lutz book was, it still offered a vision of a kind of animation far more advanced than the Film Ad cutouts. Lutz wrote at a time when animators commonly worked entirely on paper. They made a series of drawings, each different from the one before, that were traced in ink and photographed in sequence to produce the same illusion of movement that Film Ad achieved by manipulating cutouts under the camera. Lutz advocated the use of celluloid sheets to cut down on the animator’s labor—the parts of a character’s body that were not moving could be traced on a single sheet and placed over the paper drawings of the moving parts. Such an expedient (and Lutz recommended others) would have resonated with Disney, who had been so impressed by commercial art’s shortcuts when he worked for Pesmen-Rubin.

Barrier also quotes Hugh Harman as saying, “Our only study was the Lutz book . . . that, plus Paul Terry’s films.”

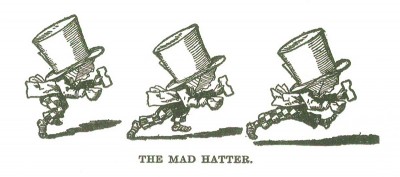

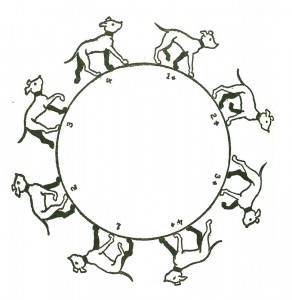

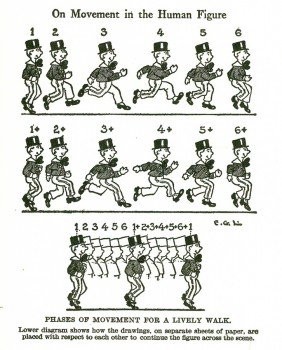

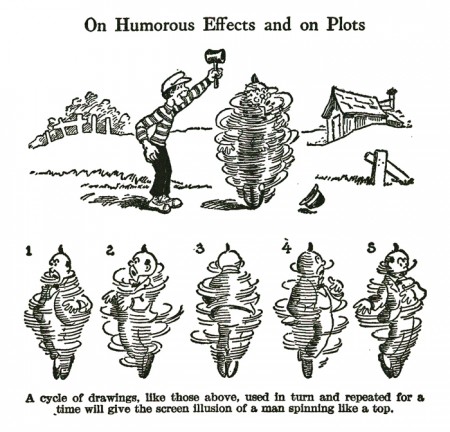

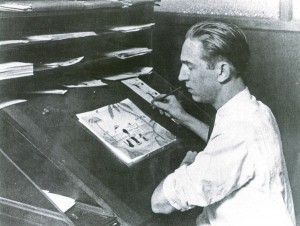

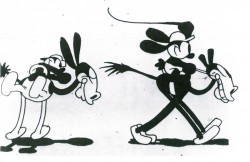

This is one of the illustrations Lutz did for his book,

The Animated Cartoon.

Donald Crafton talks extensively of the management theory of Frederick W. Taylor. Taylor basically stated that lower paid jobs should be done by lower paid employees on what would basically become an assembly line. This was adapted by J.R. Bray and Thomas Ince. The Inbetweener was born. Crafton writes:

- In his 1920 manual, Lutz was still promulgating the taylorist philosophy—for example, when he described the tracers’ function in language echoing Bray. “It can be seen from this way of working in the division of labor between the animator and his helper that the actual toil of repeating monotonous details falls upon the tracer. The animator does the first planning and that part of the subsequent work requiring artistic ability.

Initially, Disney rejected this theory. This was something that Ub Iwerks brought to the studio after traveling from Kansas City to LA. We see this in Leslie Iwerks & John Kenworthy‘s book, The Hand Behind the Mouse:

- Ub brought the studio renewed energy and new techniques. Abandoning the stiff and rudimentary methods Or animation he had previously learned, Ub would begin to evolve bis own straight-ahead style of drawing, which did not rely on model sheets or extremes. A key aspect of the Lutz orthodoxy was pose-to-pose animation, in which, for any action, a character was drawn in its starting and ending positions (or “extremes”) and intermediate poses were filled in later. Model sheets were used to trace over the original figure, allowing the animator to simply alter the parts of the body that needed variation. Ub instead professed a new method. He felt he could coax more expressive feeling from a drawing if he used model sheets as rough guides rather than being chained to them. By trusting in his own creativity and sense of movement, he threw out all structure to make way for his own free-flowing impulses.

- Russell Merritt and J. B. Kaufman in Walt in Wonderland assert that “If Iwerks had made no other contribution to the Studio, he would deserve to be remembered for this one. It marked the beginning of the smooth, flowing ‘Disney style’ of animation; and one can see it developing, slowly but surely, as the Alice series progresses.”

We also know that one of the sore points between Disney and Iwerks, which helped cause Iwerks to leave the studio, was that Disney tried to force Iwerks to leave inbetweens for others to follow. This would get more animation out of Iwerks, who already had been the animator with the greatest speed. Ultimately, Disney fell back on what he’d learned from Lutz.

This is one of the illustrations Lutz did for his book,

The Animated Cartoon.

_________________

So, in the end, all this shows is that the Lutz book had a profound effect on animation in the developing 1920s. It also shows that Lutz did a lot of thinking about not only the process of how to make animated films and the technology available at the time of publication, but he thought of the methodology within a studio churning out many films.

We know from that initial “Lightning Sketch” illustration that Lutz was an artist. We also have to assume that he worked within an animation studio for some time to have been so thoroughly informed that he was able to describe the most meticulous details in the process of making films. Because he so completely details the workings of the camera (he also wrote a book in 1927 entitled The Motion Picture Cameraman) one would assume he must have spent some time actually shooting animation. I would guess that he started in that position, then moved into actually creating the art, as did Rudy Ising in the start of his career. It’s doubtful some producer wouldn’t use his artistic abilities in creating the animation.

This is one of the illustrations Lutz did for his book,

The Animated Cartoon.

However, this is all speculation. Perhaps he just had a strong interest and was given the authority to sit and watch within a studio. Of course, that would lead one to believe that the studio that allowed him access would have been promoted within the book. Yet. there is no studio mentioned, hence I’m led to believe that he had to have worked within a studio for some time.

I haven’t gone much farther than the books in my studio or the information on the Web. In the end, I don’t know a heck of a lot more than I started out with. I do know that Lutz’ animation book was the most important he’d written. It affected an entire industry and changed the way the process was done in the all important formative years of the studio system.

If anyone has more biographical information on Lutz, please don’t hesitate to leave it. I’d like to know more and will keep on looking.

Books &Commentary 08 Nov 2011 08:12 am

Lutz’ “Animated Cartoons” – an Overdue Review

Animated Cartoons: How They Are Made, Their Origin and Development by Edwin G. Lutz is the first important book published about animation and how to do it. The book apparently had a lot of resonance with Walt Disney and his small Kansas City staff when they started out in making animated films. They borrowed a copy of the book from the library and studied it slavishly to learn how to make animated films.

Animated Cartoons: How They Are Made, Their Origin and Development by Edwin G. Lutz is the first important book published about animation and how to do it. The book apparently had a lot of resonance with Walt Disney and his small Kansas City staff when they started out in making animated films. They borrowed a copy of the book from the library and studied it slavishly to learn how to make animated films.

I’ve owned a copy of the book for at least the last thirty years but had not read it, so this week, I set myself to the task at hand. Surprise, surprise. I found the book not only interesting but informational. Yet not totally out of date.

Lutz starts out with a history of animation – no mean task for a 1920 publication. This amounts to comparing the differences between a praxinoscope and a phenakistoscope, a zoetrope and a thaumatrope. For quite some time, no book on animation would be complete without following the example of this book and revealing the evolution of the machinery that allowed for the animation of still pictures.

Once past this, it goes into the evolution of Motion Pictures, from Muybridge to Lumiere and Edison. The author has real knowledge of the 1920 motion picture camera and how it works, and he lets us in on the secrets.

Finally, with Chapter III, 57 pages into the book, we’re into “Making Animated Cartoons.” This is when some truly practical information is relayed. Not only the shape of a lightbox and the use of two pegs for registration but the explanation of using cels (primarily, for background overlays) and limited animation.

Some examples of the practical advice he gives:

- It’s revealed that using tempera to correct stray lines on the white linen animation paper might photograph as gray, and it would be better to cut out those lines and rub down the cut edges with an eraser.

- We learn that black velvet photographs truly black. (I knew this when Richard Williams told me in 1977, however Williams added that brilliant whites are found by using white blotter paper.)

- A cut-out object, such as an airplane, can be used to cross the screen with cut-out animation rather than having to redraw the plane endless numbers of times. However you have to be careful it doesn’t change perspective, or it will not work properly.

- A platen, flattening the art at the camera shooting, should be made of glass with a wood frame. If the frame is metal it can’t breathe and the glass may break. (They later figured out a suspension device with springs to allow some give.)

In point of fact, there are dozens of such mechanical tips in the middle of the book, and they’re really entertaining to read. I can’t remember any other book combining so many such photographic tips. Usually, “how to” books are about the animation, itself, not the camera design. Or they’re focused on the camera and not the animation technique. This book offers both and with some real knowledge.

In point of fact, there are dozens of such mechanical tips in the middle of the book, and they’re really entertaining to read. I can’t remember any other book combining so many such photographic tips. Usually, “how to” books are about the animation, itself, not the camera design. Or they’re focused on the camera and not the animation technique. This book offers both and with some real knowledge.

Of course, the book was written in 1920 so there’s only a limited amount we can learn about movement. They didn’t know that much until Disney had developed animation to a high craft in the 1930s. However, it’s astonishing, at least to me, to learn how much they DID know that early in the game. It’s also a surprise, given some of the illustrations in the book, how sophisticated some of the animation is. But then the very next series of drawings is crude and like something out of the Bray’s “Heeza Liar” series.

The latter part of the book goes into the construction of good gags (after all, animated films are about comedy, he tells us), and the conclusion seems to be that circuitous motions are the funniest. Lutz paraphrases Henri Bergson’s philosophy in explaining:

In a boisterous low comedy it is always incumbent upon the victim of a blow to reel around like a top before he falls. It never fails to bring laughter. An effect like this is easy to produce in animated cartoons. There is no need to consider physiological impossibilities of the human organism, the artist can make his characters spin as much as he pleases.

In a boisterous low comedy it is always incumbent upon the victim of a blow to reel around like a top before he falls. It never fails to bring laughter. An effect like this is easy to produce in animated cartoons. There is no need to consider physiological impossibilities of the human organism, the artist can make his characters spin as much as he pleases..

In a screen picture two boys will be seen fighting; at first they will parry a few blows, then suddenly begin to whirl around so that nothing is visible but a confused mass and an occasional detail like an arm or leg. It will be exactly like a revolving pinwheel. This is made on the film by having a drawing representing the boys as clinched and turning it around as if it were a pin-wheel.

.

In a panorama screen effect it seems to be sufficiently realistic, for laughter purposes, to have the legs and arms of the individual in a hurry give a blurred impression, in some degree, like that of the spokes of a rapidly turning wheel.

Lutz continues for six pages telling us how circular movements

provide gales of laughter for the audience. He just about

convinced me. I’ll be keeping my eyes open in the future.

.

The book ends with a discussion of the future. This, Lutz decides, is in educational animation. He gives examples of mechanical processes, such as pistons operating or gears in motion, or he mentions a device invented to teach deaf children to read lips. Oddly enough, this belief in the future of educating via animation was the same belief that both Fleischer and Disney had in the 1920s. I wonder if they got their notion of this future from Lutz. Interesting how both broke from this type of thinking when they found that there wasn’t much money in educational films. (Bray, on the other hand, did little more than educational work starting in the 20s and going well into the 50s. That man knew how to roust a buck.)

.

The book, Animated Cartoons: How They Are Made, Their Origin and Development is a good read, although the writing style is a bit stiff reflecting the style of its day. It’s almost Victorian in its stodginess. Accepting that – you always have to remember the book was published in 1920, yet there’s quite a bit to be found here. Any animator with one foot in the medium’s history really should read this book. It took me a few decades, and I’m sorry I didn’t get to it sooner.

.

While reading this book, I became particularly interested in who E.G. Lutz actually was. My limited research didn’t turn up a hell of a lot, but I did decide to share what I could find out. I’ll do it in another post, since I’d like to quote several other books in length, and it seems to be another direction than this review wants to take.

Books &Commentary 03 Nov 2011 06:58 am

Dad’s Daughter’s book – an Overdue Review

- I haven’t read the book, The Story of Walt Disney by Diane Disney Miller “as told to Pete Martin“, since it was originally published in 1957. Actually, I probably read the version that was serialized in the Saturday Evening Post in November 1956; then I most likely asked for a copy of the book for a Christmas present and read it then. After all, I was only 11.

- I haven’t read the book, The Story of Walt Disney by Diane Disney Miller “as told to Pete Martin“, since it was originally published in 1957. Actually, I probably read the version that was serialized in the Saturday Evening Post in November 1956; then I most likely asked for a copy of the book for a Christmas present and read it then. After all, I was only 11.

I remember being grabbed by the book and hooked for all time on animation. Two years later, the Bob Thomas Art of Animation would lock it up for me.

The Story of Walt Disney is an odd book to review. I wonder how much actual research went into the writing. Was it enough to have the source, Walt Disney, reveal his story verbally to Diane and Pete Miller? The voice undoubtedly comes through. The book comes off as one for youngsters; there’s an innocence in the writing that Pete Miller obviously got across. He did the writing; the book is labelled “by Diane Disney Miller as told to Pete Martin.” Martin was a writer for The Saturday Evening Post, where the book was serialized prior to its publication. Miller was also known for having collaborated with Bing Crosby on a book of memoirs before working on this Disney book.

Since this book is essentially out of the mouth of Walt, we have to pay attention to some of the stories being told. What was told and what was skipped?

Since this book is essentially out of the mouth of Walt, we have to pay attention to some of the stories being told. What was told and what was skipped?

There’s quite a bit more than usual about the Red Cross service Disney did at the end of WWI.

The “Alice” series is called by the title “Alice in Cartoonland.” Unfortunately, the Disney brothers called the series the “Alice Comedies.” Even though their first short was known as “Alice’s Wonderland,” they didn’t refer to the others with any reference to Lewis Carroll’s work. That may well have been the demand of the distributor Charles Mintz even though the Disneys may have thought of the series as “Alice in Cartoonland.” Obviously, Walt referred to it as that title in telling this story.

There’s a mention of Ub Iwerks when Walt asked him to move out to LA, but there’s no mention of his name when Iwerks left Disney to open his own studio under the assistance of Pat Powers. There’s some detail in the chapter about Snow White, but barely a mention of Pinocchio or Bambi. Lots to tell about Fantasia and a bit more about Dumbo. No mention

of Song of the South, Fun and Fancy Free or So Dear to My Heart, but Cinderella gets attention as do the documentary nature films. There’s an odd telling of the Disney strike in this book, and the suggestion of how the South American trip came about. In truth, the book becomes more about the juggling of money once Snow White goes into production and less about the actual films. There’s plenty of detail about going public with the stock options, and there’s a lot of detail about the government work done during WWII.

of Song of the South, Fun and Fancy Free or So Dear to My Heart, but Cinderella gets attention as do the documentary nature films. There’s an odd telling of the Disney strike in this book, and the suggestion of how the South American trip came about. In truth, the book becomes more about the juggling of money once Snow White goes into production and less about the actual films. There’s plenty of detail about going public with the stock options, and there’s a lot of detail about the government work done during WWII.

An interesting sentence comes at the beginning of the book when we read about the farm in Marcelline in hs childhood. “He can still draw a mental – or rather a sentimental – map of that whole community exactly as it was then.” This is a rare sentence by Diane commenting on her father’s recollections, and one wishes there were more like it. The last chapter of the book offers a bit more of this when Diane decides to tell a bit more about her father away from the office. What he likes to eat, how he acts, etc. There’s a lot of personality in this chapter.

One wonders how useful this book is for actual animation historians. Mike Barrier and John Canemaker have obviously read it, but do they trust the material? And why shouldn’t they, especially if there’s a second source for any of it. The story as a whole is very readable, and one rolls along easily in the telling of the tale. It’s especially entertaining. Obviously, the goal was to make the story for the largest possible audience, so details of the films were less interesting than the struggles of the imaginative entrepreneur.

You know that “dad” enjoyed telling his daughter of all his accomplishments. So this is his version, and it’s interesting how it comes out filtered through the voices of Diane and Pete Miller. Diane’s pride in the studio is certainly as great as Walt’s.

You know that “dad” enjoyed telling his daughter of all his accomplishments. So this is his version, and it’s interesting how it comes out filtered through the voices of Diane and Pete Miller. Diane’s pride in the studio is certainly as great as Walt’s.

- “Father did the outlines of the drawings. The other two filled them in. Gradually Father gave them bigger assignments, until they were doing whole scenes themselves. Even then Father insisted upon a distinctive Disney style of drawing and photography, and he trained his two helpers to do things his way.

.

“They weren’t the only ones who have conformed to the Disney style. Almost all animated techniques since have conformed to the basic formulas that emerged from that primitive studio. Although they may vary in spirit, or another cartoon maker’s conception of what gives greater pictorial impact may differ from Father’s, they all owe a debt that goes back to the inventiveness and experimentation that went on in the back room of that converted real estate office.”

That sense of pride is understandable.

The Story of Walt Disney is actually a good read if you have a copy and haven’t seen it in years. Or you might be able to locate a copy in the library. Take the time; it moves quickly and is fun.

Books &Commentary &Disney 27 Oct 2011 06:18 am

Walt in Wonderland – overdue review

- The book I reread this week was Russell Merritt and J.B.Kaufman‘s Walt in Wonderland. Actually, this was the third time I’d read the book, and I’ve also visited it another half dozen times just for the illustrations. Needless to say, I think this book is a treasure.

- The book I reread this week was Russell Merritt and J.B.Kaufman‘s Walt in Wonderland. Actually, this was the third time I’d read the book, and I’ve also visited it another half dozen times just for the illustrations. Needless to say, I think this book is a treasure.

In the past three weeks, I’ve read three versions of the same material in different forms. Timothy S. Susanin’s Walt Before Mickey: Disney’s Early Years, 1919-1928 led me to reread Donald Crafton ‘s Before Mickey and that led me to reread today’s book. They all come with different pleasures. Though the material was the same, in no way did I feel as though it was repetitious. All three writers have different approaches, and all three kept it lively for me.

Crafton’s Before Mickey tells the story most expeditiously. There’s a lot in this book, and the Walt Disney story is just a part of it. Susanin’s Walt Before Mickey reveals a very large gathering of data, much of which is really unnecessary to the story, but just the same was a delight to me. Merritt & Kaufman’s Walt in Wonderland expands on Crafton and holds back on extraneous material. However the book is overrun with enormously valuable visuals. Scripts, story pages, animation drawings, posters and pictures fill the space around the story of Walt Disney’s rise from nowhere through the creation of Mickey Mouse.

The authors take the time to reveal some of their methods of evaluating the material. For example, not all of the silent films exist today, so they create a complete filmography from archival texts they found. Copyright forms required synopses of the stories as well as credits for the films. This enables the authors to detail the material for us when they weren’t able to actually see the films. Prior to this book, we knew that Virginia Davis, Dawn O’Day and Margie Gay all played Alice in the Alice Comedies. However, Kaufman and Merritt were also able to identify a fourth Alice as Lois Hardwick, and they also calculate why the change. This is scholarship, well done.

The authors take the time to reveal some of their methods of evaluating the material. For example, not all of the silent films exist today, so they create a complete filmography from archival texts they found. Copyright forms required synopses of the stories as well as credits for the films. This enables the authors to detail the material for us when they weren’t able to actually see the films. Prior to this book, we knew that Virginia Davis, Dawn O’Day and Margie Gay all played Alice in the Alice Comedies. However, Kaufman and Merritt were also able to identify a fourth Alice as Lois Hardwick, and they also calculate why the change. This is scholarship, well done.

Though I’ve read this book several times already, I still call this series “Alice in Cartoonland.” In fact, many people do, yet the authors point out that it was never the title of the films. They were simply called the “Alice Comedies.”

I was not much of a fan of this animation series; actually, I was not a big fan of the Disney silent films. They pale in comparison to the Felix cartoons of the same period – in fact, almost everything does (of course with the exception of the McCay films.) The Disney silent films have a lot of energy, but a farmyard sense of humor that never seemed very funny to me.

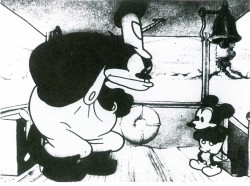

I’ve sat through numerous theatrical screenings of silent shorts (and fallen asleep in many of them). One, however, stands out memorably. There was a MoMA show which was a compilation of shorts from different studios. An organ soundtrack was attached to many of the shorts, but several were truly silent. (It’s interesting to attend an audience who doesn’t know if talking is allowed when the film is dead silent.) The program soon grew tiresome and dragged on. The last film screened was Disney’s “Steamboat Willie,” the first successful animated short with synchronized sound. Let me tell you, it was made perfectly clear how monumental this film was, and why it was so successful. That sound track was a godsend after 90 minutes of silent dross.

I’ve sat through numerous theatrical screenings of silent shorts (and fallen asleep in many of them). One, however, stands out memorably. There was a MoMA show which was a compilation of shorts from different studios. An organ soundtrack was attached to many of the shorts, but several were truly silent. (It’s interesting to attend an audience who doesn’t know if talking is allowed when the film is dead silent.) The program soon grew tiresome and dragged on. The last film screened was Disney’s “Steamboat Willie,” the first successful animated short with synchronized sound. Let me tell you, it was made perfectly clear how monumental this film was, and why it was so successful. That sound track was a godsend after 90 minutes of silent dross.

There is one telling sentence at the beginning of this book. “. . . the first striking fact about Disney’s 1920s films is that they take no particular direction: they don’t evolve, they accumulate.” The authors point out that knowing the films of the 30s Disney, one would expect that the work in the 20s would, likewise, be a developing road-map to the future; constant growth in the animation and production techniques. Yet, it isn’t until Mickey that we start seeing enormous growth. “Plane Crazy,” the first Mickey (still a silent film), is when we get the first truck in (Iwerks came up with this effect, created by placing books under the zooming background as it got closer to the lens of the stationary camera.) Perhaps it took the trauma of creating that first Mickey Mouse cartoon for Disney and crew to wake up to innovation. And perhaps realizing how powerful that innovation was to the animated film – the success of the first sound film, then the first color film – that Disney realized the importance of constant change and growth.

There is one telling sentence at the beginning of this book. “. . . the first striking fact about Disney’s 1920s films is that they take no particular direction: they don’t evolve, they accumulate.” The authors point out that knowing the films of the 30s Disney, one would expect that the work in the 20s would, likewise, be a developing road-map to the future; constant growth in the animation and production techniques. Yet, it isn’t until Mickey that we start seeing enormous growth. “Plane Crazy,” the first Mickey (still a silent film), is when we get the first truck in (Iwerks came up with this effect, created by placing books under the zooming background as it got closer to the lens of the stationary camera.) Perhaps it took the trauma of creating that first Mickey Mouse cartoon for Disney and crew to wake up to innovation. And perhaps realizing how powerful that innovation was to the animated film – the success of the first sound film, then the first color film – that Disney realized the importance of constant change and growth.

Whatever the reason, things changed with the coming of sound.

Walt in Wonderland is a key book that synthesizes this entire period in the evolution of Disney animation. It’s a little-known beginning, and the book not only details the making of all the films but gives a clear and good summary of the series that were done. You see the long shot as well as the close up, and you have no doubt as to the true history of the material.

Walt in Wonderland is a key book that synthesizes this entire period in the evolution of Disney animation. It’s a little-known beginning, and the book not only details the making of all the films but gives a clear and good summary of the series that were done. You see the long shot as well as the close up, and you have no doubt as to the true history of the material.

The authors obviously did enormous research, yet the look of the book, filled with new and different visuals, is anything but scholarly. As a matter of fact, there are times when the images almost create a distraction from the writing. A tough problem for an animation book to have.

All I can say is that if you have any interest in the early Disney, the young and vibrant Disney, I’d suggest you get a copy of this book. It’s a gem.

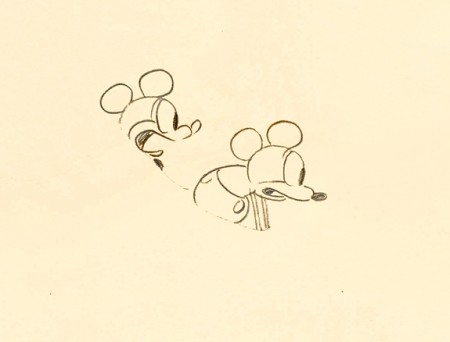

Here’s a drawing I have from Plane Crazy.

Click the image to see the whole drawing.

Books &Commentary 20 Oct 2011 07:23 am

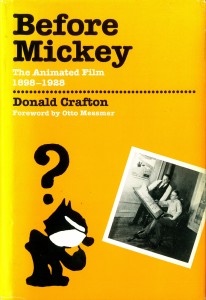

Crafton’s BEFORE MICKEY

- I’ve been rereading some of the animation books that were released long before this blog existed. This gives me the opportunity of reviewing them fresh. Rereading them means, most probably, that I liked them enough in the first place that I wanted to read them again. That’s probably true, at least it is in the case of today’s book. This was the third time I’ve read Donald Crafton‘s brilliant work of animation history, Before Mickey.

- I’ve been rereading some of the animation books that were released long before this blog existed. This gives me the opportunity of reviewing them fresh. Rereading them means, most probably, that I liked them enough in the first place that I wanted to read them again. That’s probably true, at least it is in the case of today’s book. This was the third time I’ve read Donald Crafton‘s brilliant work of animation history, Before Mickey.

This book is one of those that has been THE source for many researchers once it arrived on bookshelves. It is, as its title states, a history of animation prior to the first Mickey Mouse cartoon, meaning the first recognized sound cartoon. As such it’s an invaluable work, and I do mean invaluable.

The subject matter for this book is a large one, and prior to this, no one had written extensively about silent film animation. Even after the book was first published in 1982 to today, there have been few others devoted to the subject of early animation.

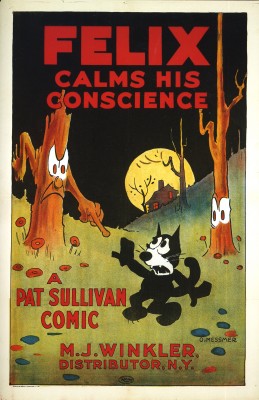

- John Canemaker wrote two books: one about McCay and a second about Felix.

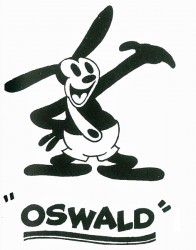

- There have been several about Disney’s work before the sound films, particularly Merritt & Kaufman‘s Walt in Wonderland: The Silent Films of Walt Disney and Timothy S. Susanin‘s Walt before Mickey: Disney’s Early Years, 1919-1928.

- Several have a wider scope, particularly Denis Gifford‘s scholarly tome, American Animated Films, the Silent Era, but even this book eliminates 2/3 of the world’s cinema. That’s pretty much it.

The surprise is that the book pretty much got it right with this first one. In the writing, Crafton records the short histories of many significant filmmakers from Bray to Terry, McCay to Messmer, from Disney to Dyer, Cohl to Fleischer. He gives an account of many animators who enter learning; people such as Tytla, Culhane, Huemer, Nolan and Iwerks among many others pass through the book before they become the giants of the industry.

The surprise is that the book pretty much got it right with this first one. In the writing, Crafton records the short histories of many significant filmmakers from Bray to Terry, McCay to Messmer, from Disney to Dyer, Cohl to Fleischer. He gives an account of many animators who enter learning; people such as Tytla, Culhane, Huemer, Nolan and Iwerks among many others pass through the book before they become the giants of the industry.

The book is divided into numerous sections. At first there’s a focus on the various individuals that created the medium, people like Blackton, Cohl and McCay. Then we move to those who turned it into an industry, those like Bray and Fleischer and Terry.

Once all of the US studios are touched on, Crafton moves to Europe; we learn how the different countries such as Britain, France, Germany, Sweden and Russia established their industries and animators. I’m sorry Crafton didn’t really go into the work in Japan and China since both countries developed strong and thriving animation studios, but the book could only house so much.

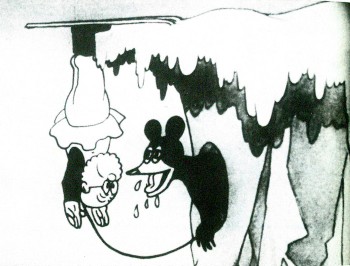

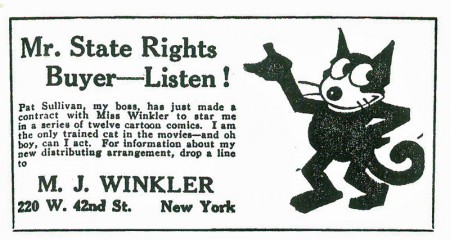

One of many ads printed in the book.

Following this, Donald Crafton goes back to a theme which slyly entered in the book’s opening, the subject matter of the films. At first he recognizes that animation follows the comic strips of the day with a heavy focus on human characters, but somewhere in the early 1920′s characters became animal – animals that stood upright and acted like humans. This is probably precipitated by the arrival of Felix the Cat and the Sullivan sudios. With his  enormous success, there were a large number of imitators. From Terry to Disney, everyone found animated cats that were able to unscrew their tails and use them in a multitude of comic situations. Sullivan sued, and Terry’s cat went from being named Felix to Herman; Disney named his cat Julius. It is an important theme to Crafton, this concern whether a character is human or animal, and one can ultimately understand the need to categorize when one has to include so many wildly varying types of film.

enormous success, there were a large number of imitators. From Terry to Disney, everyone found animated cats that were able to unscrew their tails and use them in a multitude of comic situations. Sullivan sued, and Terry’s cat went from being named Felix to Herman; Disney named his cat Julius. It is an important theme to Crafton, this concern whether a character is human or animal, and one can ultimately understand the need to categorize when one has to include so many wildly varying types of film.

The book is an enormous work, and Donald Crafton has got it right. It’s invaluable; that’s the only word I can muster for it. The book is invaluable. It’s as informative on the third read as it was on the first, and there’s a reason that all of the books mentioned in the third paragraph refer back to this book. It’s a big subject and is handled with seeming ease. The book reads easily; the author keeps your interest. This book is a corner stone for an entire section of the animation history section.

.

If you’d like to see some silent animated films, I heartily recommend Tom Stathes‘ site where you’ll find a large number of films available.

.

.

.

.

.

A personal note. I had just finished reading this book, back when it came out, and was gifted with another copy from Bob Blechman. I’d done some favor for him, and the book was a small means of thanking me for it. I appreciated it, and I cherish the little Felix that Bob drew in the book for me.

.

.

Books &John Canemaker 13 Oct 2011 05:50 am

Canemaker’s Felix Book

- I’ve recently been rereading the classics. No, I don’t mean Madame Bovary or Great Expectations; I mean animation’s classic books. Since this blog came into being a mere 6 years ago, I haven’t had the chance to review many of these books, which predate this blog, and I thought it time to share my guilty pleasure (reading) with you. So, I’m about to start reviewing some older books. In a sense, I’ve already done this by commenting on some of the books I never got up to reading – such as Culhane’s Talking Animals and Other People. I’m also going to review some books I’ve been rereading.

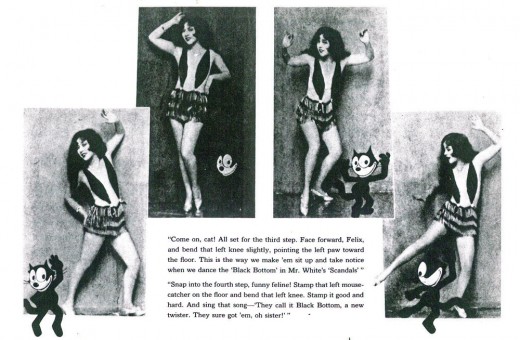

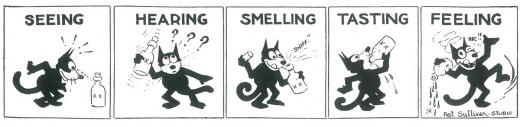

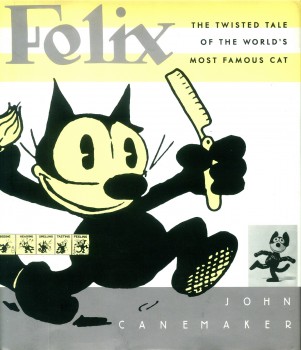

First up is Felix, The Twisted Tale of the World’s Most Famous Cat by John Canemaker. This was Canemaker’s second book, following his Winsor McCay, His Life & Art. This is the second time through this book for me (lately I’ve been into reading about the earliest days of animation’s history), and it’s every bit as entertaining and informative as my first read.

First up is Felix, The Twisted Tale of the World’s Most Famous Cat by John Canemaker. This was Canemaker’s second book, following his Winsor McCay, His Life & Art. This is the second time through this book for me (lately I’ve been into reading about the earliest days of animation’s history), and it’s every bit as entertaining and informative as my first read.

You get both a history of Pat Sullivan, the entrepreneur who made a success of Felix and Otto Messmer, the animator who actually developed and brought Felix to life. The two stories run concurrently, and it’s obvious that Sullivan’s life was more dramatic. His story is a potboiler.

At the very start of his studio, Sullivan was incarcerated for nine months after being convicted of raping a 14 year old girl. Then he watches Messmer develop Felix into a superstar, capable of competing with any live-action celebrity. Riches flowed into the studio most of which ended up in Sullivan’s pockets.

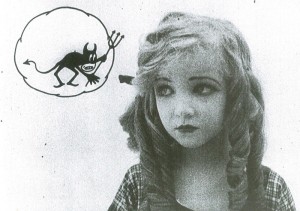

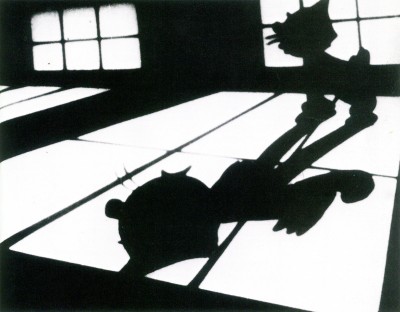

Still from “Sure Locked Homes”

At the end of his life, when Felix films were on a decline, Sullivan’s wife had committed suicide (although her falling out a window to her death may have been accidental), and Sullivan’s health began to quickly deteriorate. “Whether caused by grief over Marjorie’s death, years of alcoholic abuse, or the tertiary stage of syphilis that finally affects the brain, or a combination of all three, it was obvious that Pat Sullivan was losing his mind.”

This is a page turner of a story.

.

Threaded through it all is the steady and less interesting read of the shy animator who worked tirelessly to create, develop and produce the first character to exhibit a screen personality. Otto Messmer was the synthesis of most animators: work hard during the day in a mostly internal job, then go home to the mundane, middle class existence in the suburbs. It doesn’t make for a great read, but it made for great films.

Threaded through it all is the steady and less interesting read of the shy animator who worked tirelessly to create, develop and produce the first character to exhibit a screen personality. Otto Messmer was the synthesis of most animators: work hard during the day in a mostly internal job, then go home to the mundane, middle class existence in the suburbs. It doesn’t make for a great read, but it made for great films.

Canemaker tells both well, and it does have its effect. The book moves quickly and enjoyably.

It’s also something of a scrapbook in that there are plenty of images of Felix to show you what a complicated character Messmer had created. These cartoons were certainly more for adults than children. There was plenty of alcohol in the films and strips that flowed from the studio. War was a subject that was treated seriously. World War I had acutely affected many of the animators as well as the audience, and these films were particularly successful in the series.

For ten years the films reached a zenith of riches, and it was difficult for other animated films to break through the inner circle that Felix had developed. Margaret Winkler and her husband, Charles Mintz, distributed the Felix films, and when Sullivan sought greater fees he threatened to quit. Winkler then developed the young Walt Disney to serve as a backup plan should she lose the Felix films. She eventually did. Her husband ultimately forced Disney out as well, and that’s when the historic happened.

Disney created Mickey Mouse in his first sound film, Steamboat Willie. All of Sullivan’s tardy attempts to issue post-recorded versions of Felix with sound were useless, and Felix became a has been. Sullivan died within four years, and Otto Messmer quietly spent the rest of his life hiding behind the Felix the Cat comic strips. It’s a sad story that John Canemaker reveals, and he gives the full version in this attractive book.

Disney created Mickey Mouse in his first sound film, Steamboat Willie. All of Sullivan’s tardy attempts to issue post-recorded versions of Felix with sound were useless, and Felix became a has been. Sullivan died within four years, and Otto Messmer quietly spent the rest of his life hiding behind the Felix the Cat comic strips. It’s a sad story that John Canemaker reveals, and he gives the full version in this attractive book.

I remember way back when, I think it was 1975, that I accompanied John Canemaker on a trip to Otto Messmer’s house and got to meet the man. The afternoon was quite pleasant, and I sat as an observer witnessing a casual and enjoyable Q&A with Mr. Messmer. I don’t remember much about the interview, but I do remember it as sunny and quite agreeable. I also remember my first reading of this book and seeing how John had turned that interview into something meatier than I remembered witnessing. He certainly interviewed Messmer many more times for the book (and the valuable documentary Otto Messmer and Felix the Cat, that he made in 1977.) It was my first time to see the fruit turned into facts, and it was an eye-opening experience.

Today I see the very informative book, and I also see the stylistic prose John adapted in the writing. It’s obvious he was completely invested in the subject and period and people of this book, and you can’t ask for much more from such an historic account. If this book isn’t part of your collection, it should be. At least, borrow it from the public library and read it.

Here‘s a nice interview from1991 with John and ira Gallen.

The documentary, Otto Messmer and Felix the Cat can be found on the DVD John Canemaker, Marching to a Different Toon.