Category ArchiveArticles on Animation

Articles on Animation &Independent Animation &Layout & Design 17 Jan 2012 07:00 am

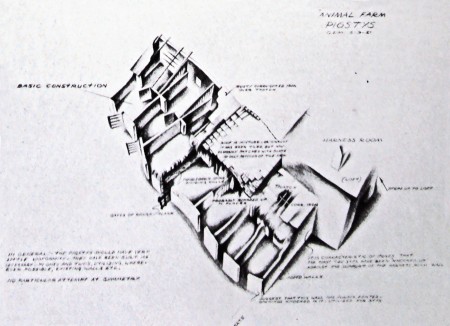

Designing Animal Farm

Chris Rushworth, whose site AnimalFarmWorld, is dedicated to the collection of material about and from the Halas & Batchelor feature animated film, Animal Farm, has sent me an article he’s found and which I thought extraordinarily interesting. It’s from a UK publication called “Art & Industry” dated September 1953.

Since there were difficulties with the scans, I had to retype the article so it could be legible and I played with the images in photoshop trying to bring some clarity to the sketches. I think they work well enough for this posting.

Geoffrey Martin, a senior member of the design team of the

Halas & Batchelor Cartoon Studios, describes his work on the production

of George Orwell’s ANIMAL FARM as a full-length feature cartoon film.

The painter and the film and stage designer work with similar motives but from varying standpoints. One one hand, the painter needs only to justify himself, while on the other, the work of the designer must fit within the framework of another man’s concept. The painter is more or less free to stand apart, and need not e called upon to explain his motives or analyze his emotions. The designer, to achieve his ends is dependent on others, and must therefore rationalize and be able to explain every nuance of his work in order to amplify the trends and emotions in a story and convey them to an audience.

The principles of designing a cartoon film are little different from those involved in a live-action film, With the obvious difference of the medium and its flat dimension, the other elements involved derive purely from the mechanics of animation. Both films set out to tell a story, to corner an idea, and to induce a reaction from the audience.

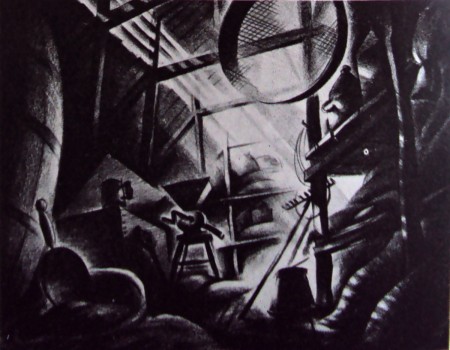

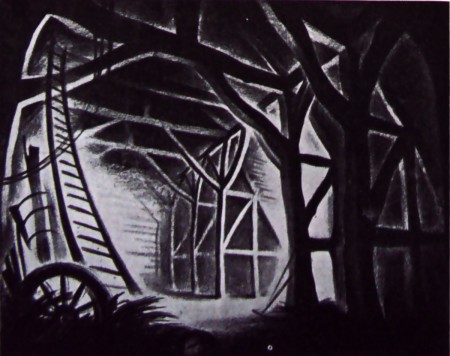

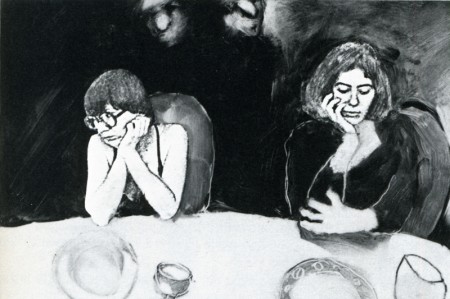

One of Geoffrey Martin’s rough atmosphere sketches

embodying his conception of the farm in relation to the story

in which the animals revolt and dispossess the farmer. The

mood of Orwell’s political satire is excellently captured in this scene.

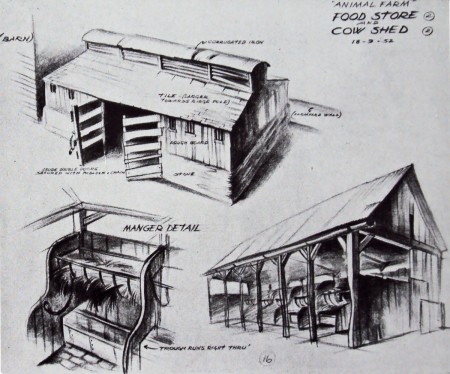

This sketch shows a corner in the farm’s food store

and was created to suggest possible props.

The cartoon designer is, if anything, more directly concerned with, and responsible for, the graphic impression on the screen than the art director in a live-action studio. To him falls the choice of angle of every sot and the responsibility of ensuring that the angle cuts smoothly to another, while constantly preserving the audience’s sense of time and place.

Once having designed and built his settings, the art director on the live-action film is largely in the hands of the director and his lighting cameraman; on these people depends how much of his original attempt is retained in the finished film. It is in this respect that the cartoon set designer is more fortunate; he has much more control over his medium, and is able to assess the result of his work more immediately by seeing the designs in actual use soon after leaving his drawing-board.

Above: The final interpretation of the scene shown opposite

painted by Matvyn Wright, principal background artist on the

production. Colour heightens the dramatic impact of the scene.

Until comparatively recent years, cartoon films were more or less and American monoply, but just ten years ago John Halas and his wife, Joy Batchelor, set up in London what is to-day the largest cartoon production group in Europe. Wisely, perhaps, they never attempted to emulate the exuberant style of M.G.M.’s ‘Tom and Jerry’ and others who work in similar vein, and as far as the feature field was concerned, Walt Disney, with his lavish and technically superb productions, reigned supreme. Instead, the concentrated on an entertaining series of educational and sponsored subjects with a definite adult flavour.

In late 1951, American producer Louis de Rochemont (‘The House on 92nd Street,’ ‘Boomerang,’ and ‘The March of Time’ series) asked the Halas and Batchelor studios to prepare an animated version of George Orwell’s sharp-edged political satire, Animal Farm. De Rochemont felt the studios to possess a style markedly different from their American counterparts – a style eminently suited, moreover, to what was, to all intents and purposes, a paradox, a ‘serious’ cartoon.

Above: Winter landscape. The half completed windmill

and the farmhouse are shown in this sketch suggesting

the starkness and economy of the settings.

When the studios first embarked on the subject, I was, as a designer, faced with many new problems. For although I possessed considerable experience of short films, Animal Farm was the first feature cartoon to be produced in this country and in length alone, was something completely new to me.

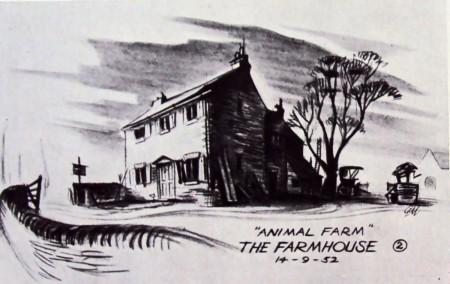

A first attempt to specify the

general style of the farmhouse.

After discussing the story with John Halas and Joy Batchelor, I made a considerable number of atmosphere sketches and rough plans. In these, I attempted to embody our many ideas regarding the conception of the farm in relation to the story.

On reading the book, I had been impressed by the windswept starkness of the farm-qualities contrasting strongly with the warm normality of the local Inn and the village, representing the outside world. We decided that the coulour would eventually go a long way towards emphasizing the contrast between those two main locations.

Since much of the designer’s work is dependent on other departments, I feel that at this point it would be well to describe the production processes of a cartoon studio. Firstly, a word here about animation, itself. In the layman’s view the animator merely ‘makes the characters move’. He does more than that, in effect, he is the very ‘life’ of the film. To make a character move does one thing, but to invest him with the spark of life and a distinct personality is a major achievement, and an element nowadays too often taken for granted.

Audiences have become accustomed to such miracles. Without character there can be no story; the characters within a play are the play. A cartoon film needs a gifted team of animators to bring life and conviction to the characters, and on their work it stands or falls.

To return to actual production, however, the story is broken down into convenient sequences to facilitate handling. In Animal Farm, we have 18 sequences, varying between three and four minutes of screen time each; this represents some 6,400 feet of film in all.

The animation director, who is to the cartoon what the choreographer is to the dance, must then time the action of each scene with stopwatch and metronome. The entire action is planned against a musical score, and to various tempi: so many bars per minute and hence per foot of film.

It is here that the designer enters the picture again. He must work to present the action the director has visualized in the most direct way possible. His department must produce the layout of each scene and the finished drawings of the settings – including sketches of the characters and their size in relation to their settings and notations as to camera movements within the scene.

A panoramic view of the farm – used to establish

the relationship of the outbuildings to the farmhouse.

Sets of the drawings are then passed to the animation team responsible for the sequence. On completion of the work, a test shot is made of their rough drawings.

This test is checked and corrected to refine and smooth out the action. I no drastic alterations are required, the layout drawings are passed to the background department who render them in colour. The animation is traced on to sheets of celluloid and coloured with opaque paint, and the characters on the ‘cells’ are finally united with their appropriate backgrounds under the Technicolor camera.

In planning the finished layout of each scene and staging each individual piece of action, we sometimes found that perhaps the story-line demanded a change in the location of a basic set. Having solved such a problem quite happily, we might then have to rearrange our set as it was originally a demand imposed, perhaps by a later sequence.

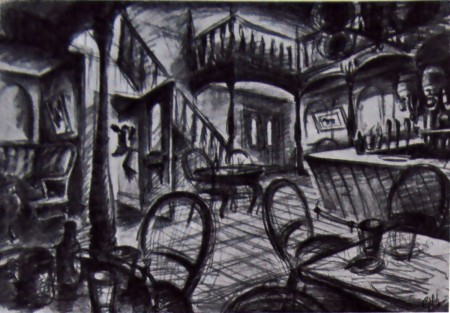

Tentative design for the interior of the village inn.

There is, in fact, a period in every cartoon film when the settings are in a continual state of change and compromise. The designer must bear in mind all the miscellaneous action which takes place in any given location throughout the film and work with this in mind.

The live-action film director is at an advantage in that once his sets are built, the are constant. He can modifu his ideas about camera angles as he goes along. But for us, any slight change of angle withina setting means a new drawing and it is quite possible to accumulate ten or fifteen layouts featuring the same doorway from various angles -made simply in order to stage differing pieces of action.

Such a process involves problems of continuity, for in each drawing ever stone and subtlety of texture must be identical from each angle. Inevitably, it becomes necessary to simplify in order to reduce the amount of work in reproducing every detail; pet ideas are swept away, and like any artist, one is sometimes reluctant to change what one feels to be an eminently satisfactory piece of design. But hard as this may be, there s the final satisfaction of knowing that one’s sets are completely workable.

Another atmosphere sketch depicting

the general appearance of the pigstys.

Interior of the great barn, the mise-en-scène

for the planning of the revolution.

Adaptability is, I feel, the first requisite of any setting, whether for stage, film or cartoon. Admittedly, it must carry the fight amount of atmospheric quality, but this must never hamper or dominate the actors – it is essentially a mounting, yet strong enough to be felt by the audience.

Designs establishing the appearance of farm outbuildings

and a detail of one of the mangers.

One of the main problems of designing for Animal Farm has been that the action takes place over a period of years. We have been faced with the problem of reproducing the same settings time and time again – sometimes in bright sunshine, and sometimes, in the depth of winter. It is here that the designer depends very greatly on the background department, and in Matvyn Wright, the principal background artist ont he production, we have been very fortunate. He has a reat feeling for mood and overal texture – qualities with which each of his paintings is invested. It is ovious, of course, that the background painters can make or mar the designer’s work; the effects striven for can be over-stated or lost completely. As an artist he is in the unenviable position of having to work on second-hand ideas. The initial conception is not his, only the interpretation. So often our first rough sketches have a life and excitement that is hard to reproduce.

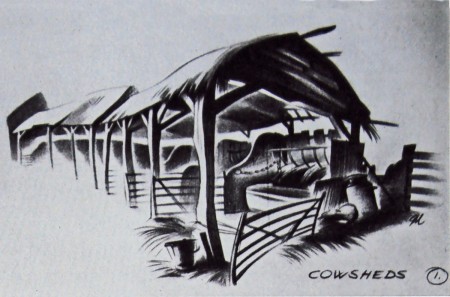

Sketch finalising the type of structure used for housing the cows.

The reader may now begin to understand that the cartoon studio is a closely integrated unit. It is, in fact, an essentially co-operative art. Although each and every person working on the production is an artist in his own right, we are all, to greater or lesser extent, interpreters, each of us contributing towards the achievement of a common idea.

The designer is dependent on a basic idea, and depends yet again on others to finalize his own individual contributions. The designer depends on the background artist; the animator depends on his assistants to refine his rough drawings, and the people who trace and colour his work. No one thing appearing on the screen can truly be claimed as any artist’s sole property, since we all of us have had a hand in it to a greater or lesser degree. The original conception came from George Orwell’s story – we have interpreted his ideas to the best of our several abilities. The final assessment of the studio’s work rests, as always, with the public.

.

Thanks, again, to Chris Rushworth for passing this article on.

I wasn’t even aware of its existence, but find it quite valuable.

.

Articles on Animation &Commentary &Illustration 17 Sep 2011 06:52 am

Tributes

- This past week, Yowp, the excellent site devoted to Hanna-Barbera’s early product, offered a fine piece on Arnold Stang. After reading it, I thought it worth telling about my one contact with Mr. Stang.

I was about to do my first half-hour show for HBO. It was a musical version of the Bernard Waber children’s book, LYLE LYLE CROCODILE. Charles Strouse had written some fine songs, and I cast them with auditions. The two people who made it through without auditions were: Charles Strouse, himself, in the bit singing role as a moving man. He had a small part of the chorus in the opening song. _____________Arnold and Charles’ characters sing together.

I was about to do my first half-hour show for HBO. It was a musical version of the Bernard Waber children’s book, LYLE LYLE CROCODILE. Charles Strouse had written some fine songs, and I cast them with auditions. The two people who made it through without auditions were: Charles Strouse, himself, in the bit singing role as a moving man. He had a small part of the chorus in the opening song. _____________Arnold and Charles’ characters sing together.

Arnold Stang was cast as a bird

owned by the family. I couldn’t help myself; I had to bring in the guy who was a key part of 50 & 60s animation history – at least for my own amusement.

Arnold had to squawk a number of times, speak a few scratchy lines, and sing a couple of lines in the opening song as he, the bird, is moved into the House on East 88th Street. When we recorded Arnold singing, it was to a temp track of the music. The engineer, Strouse and I sat in the control booth with Arnold in the large recording booth.

He sang the lines. I was excited and pleased and felt he’d gotten it on the first take.

Charles Strouse said otherwise and asked for them to be redone.

The same results; I knew they were great, Charles was annoyed about them, and he made the mistake of going over me, the director, to punching the button to talk to Arnold in the booth. The two of them got into a shouting match over the ridiculous. Charles wanted Arnold to sound more like a bird. Arnold kept pointing out that he wasn’t a bird and such birds don’t talk, never mind sing. He also pointed out that he played a cat and dog and many other types of animals, but he was always a human, not an animal.

With every jab, Charles Strouse came back with another. The two of them were screaming, and I finally had to stop it. I took the button from Charles’ hand and asked Arnold to excuse us while we discussed it in the control room. From that point on, Arnold couldn’t hear us as I told Charles that he was being ridiculous and Arnold had been doing a good job. He backed off (hopefully realizing what a jerk he’d become.) However, now Charles had gotten the talent upset and he was supposed to perform under such stressful conditions. It was very unprofessional of Charles, and equally so that he thought he could take charge of the recording session. I was the director and would make all decisions from then on, and only I was allowed to speak to the performer, Arnold.

Charles yielded. What else could he do. I asked Arnold if he could step back to the beginning and try to smooth his feathers and do it one more time for me. He agreed, did a great job, and I thanked him for his help.

In fact, it did turn out great. Arnold brought a nice and funny character to the bird. Which was a minor part and not worth an argument.

Years later, for a special Birthday I had coming up, Heidi wanted to throw a surprise party. She invited Arnold, and he left a wonderful message on her machine thanking her but not able to attend. She still has that recording and it’s pretty cute. Arnold speaking in his natural voice sounding so positive and lovely.

- J.J. Sedelmaier has started a new column for Imprint Magazine. Imprint is, basically, the blog for Print Magazine. You’ll remember that John Canemaker had a year’s worth of excellent and diverse columns there, and Steven Heller continues to write some very smart pieces. Just look at the announcement about Pablo Ferro which leads to this great, recent bio of the designer.

- J.J. Sedelmaier has started a new column for Imprint Magazine. Imprint is, basically, the blog for Print Magazine. You’ll remember that John Canemaker had a year’s worth of excellent and diverse columns there, and Steven Heller continues to write some very smart pieces. Just look at the announcement about Pablo Ferro which leads to this great, recent bio of the designer.

But, back to J.J. Sedelmaier’s piece on Gary Baseman. It’s a wonderfully illustrated piece with lots of artwork from Mr. Baseman. A wonderful illustrator, he has been working for years in animation thanks to both R.O.Blechman and J.J.’s studios. He also did a fine series for Disney with “Teacher’s Pet.”

J.J. shows how they achieved his painterly style, in a commercial his studio produced, using the cels. It’s a good article and something to look forward to monthly.

.

- Illostribute is a blog devoted to the art of Illustration. They currently have a tribute to Mary Blair, which seems to have pulled many of her gorgeous illustrations from the Canemaker book, The Art and Flair of Mary Blair. (This book is a beauty and should be owned by everyone in animation.)

It’s a curious site in that they seem to post illustrations inspired by the featured artist; this they do on the Mary Blair feature. There are several older posts I found interesting. It was nice, for example, to see some paintings by Jack Levine and be reminded of his great work.

Articles on Animation &Disney &Music 13 Sep 2011 06:39 am

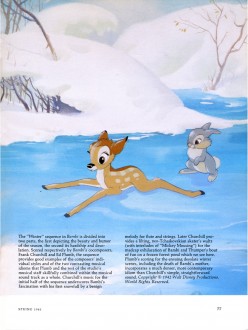

Bambi’s Music – recap

- I first met Ross Care years ago. He had scored the music to one of John Canemaker‘s early short films, The Wizard’s Son. I was impressed, and since I was looking for a composer for the first film of my new company, Byron Blackbear & The Scientific Method, I asked Ross for his help. He did a great job with little time and less money.

- I first met Ross Care years ago. He had scored the music to one of John Canemaker‘s early short films, The Wizard’s Son. I was impressed, and since I was looking for a composer for the first film of my new company, Byron Blackbear & The Scientific Method, I asked Ross for his help. He did a great job with little time and less money.

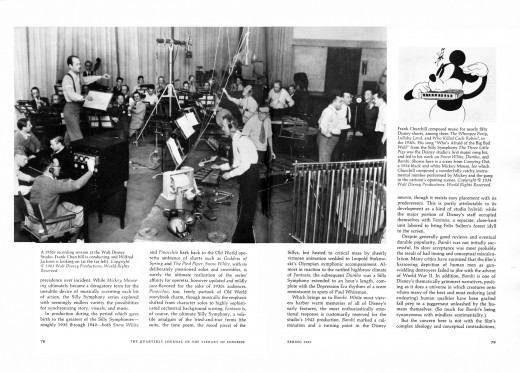

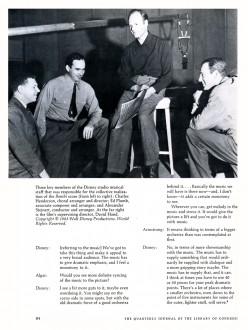

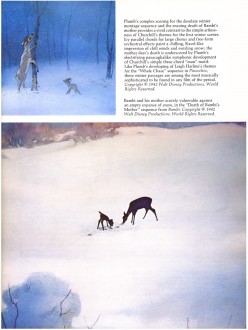

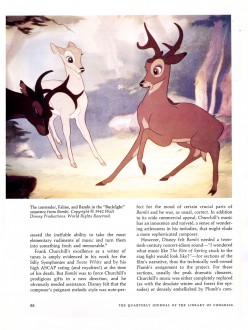

It was only a short time later, that I learned that Ross was an animation music historian. Somehow, we worked together in setting up a program for ASIFA East in which the conductor for Bambi, Alexander Steinert, took the stage with Ross to analyze the music for that film. I had a 16mm print of the film, and we watched about half of it. It was one of those memorable ASIFA meetings, that stay with you forever.

A year or two later, Ross had written an extensive article on Bambi’s music for The Quarterly Journal of The Library of Congress, the Spring 1983 edition. I just recently ran into the article on my shelves, and after getting Ross’ permission, I’m posting that article here.

_

_ 2

2___________(Click any image to enlarge to a readable size.)

4

_

4

_ 6

6

Article: Copyright © 1983 Ross B. Care

Articles on Animation 04 Aug 2011 07:20 am

Silent Animation articles

I’m reading Walt Before Mickey: Disney’s Early Years. 1919-1928 by Timothy Susanin, and I’m really enjoying it. I’ll give a review when I’m done with it. Interesting that Karl Cohen sent an article my way about silent animation. I did a short skip and a hop and found a couple of others (though none about Disney). So, today’s post will be some of those articles.

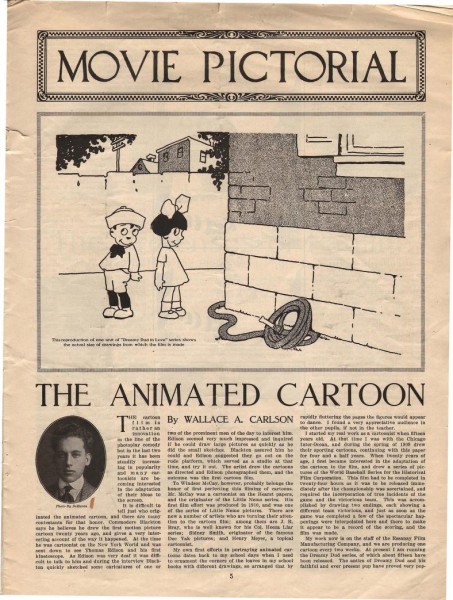

Karl Cohen of ASIFA San Francisco sent this article by Wallace Carlson about his “Dreamy Dud” series from the Movie Pictorial magazine.

cover of issue

But then I found this article to pair with it.

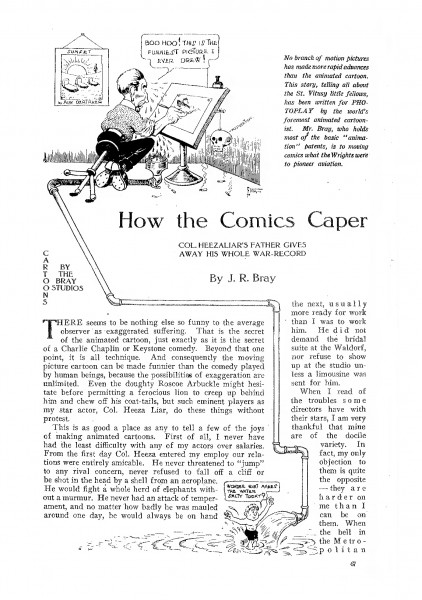

And as long as we’ve posted that one, we may as well offer this Photoplay Magazine article by J. R. Bray from the January, 1917 issue.

1

1

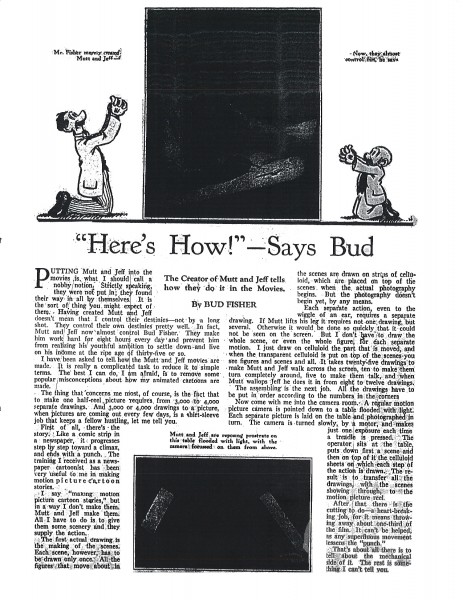

Finally, here’s an article Bud Fisher wrote for the Motion Picture Herald July 1920.

(This one took a lot of cleaning up to get it to be legible.)

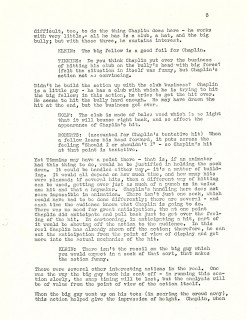

Action Analysis &Animation Artifacts &Articles on Animation &Disney 12 Jul 2011 06:46 am

Action Analysis – April 12, 1937

- Onto the next week’s class of Action Analysis at the Disney Studio, after hours. Actually, I’ve skipped a week. I only have four pages of the notes from the April 6 1937 class. Since it is missing a dozen pages, I’m not sure how worthwhile it’d be to post it. So I’ve skipped to this very full session.

Don Graham teaches. The film they study shows a 12 ft. (8 secs.) bit of a man picking himself up from mud – dragging and wading through mud. (It’s a little embarrassing posting this which actually reads: “Loop of young negro picking himself up from mud . . . Those were the days of feckless, racist behavior.) Obviously, we can’t see the footage (which is probably still somewhere in the Disney vaults), but we can pick up lots of information from the lesson.

The attendees who participate include: Jack Hannah, John Vincent Snyder, David Rose, Izzie Klein, Joe Magro, Chuck Couch, Robert Leffingwell, Milt Neil, Roy Williams, and Paul Satterfield.

Read on.

Title page

Articles on Animation &Independent Animation &John Canemaker 07 Jul 2011 07:15 am

Caroline Leaf meets John Canemaker

The following is from the book, Storytelling in Animation, The Art of the Animated Image Vol 2. This is an anthology that was edited by John Canemaker which was published in conjunction with the Second Annual Walter Lantz Conference on Animation.

A Conversation with Caroline Leaf

This transcript has been abridged from the “Tribute to Caroline Leaf” that took place on June 11,1988 during The Second Annual Walter Lantz Conference on Animation.

JOHN CANEMAKER: When Caroline Leaf was beginning work on her masterful short film THE STREET, she told an interviewer, “I wanted to tell stories with my films, and I used animal legends and myths. Now I am working more on dramatic representation: dialogue, character and human problems. Perhaps dramatic expression is not ultimately the best form for animation, but still, I do not try to do what live-action can do better. The strongest influence on me is from literature rather than film. Kafka, Genet, lonesco, Beckett, have affected me most with the depths of their visions and world views and ways of breaking up time to tell a story.”

Caroline Leaf’s work is a wonderful synthesis of many of the storytelling techniques and animation methods discussed at this conference. She represents to me both the old and the new—the traditional and the experimental. Her use of direct, under the camera techniques and brilliant metamorphoses recall the pioneering works of James Stuart Blackton and Emile Cohl. Her perfect sense of timing and implementation of personality to individuate her characters echoes the balletic movements and emotional impact of the best of Disney. Within her films the imagery can be, at one moment, representational, and, in the transitions, non-objective abstraction. Caroline tells ancient folk tales as well as modern short stories. And she uses tools as primal as her hands to position paint on a smooth surface, or push sand grains into impressionistic symbols. She records her art with a modern invention, the movie camera, which allows her to bring inert designs and stories to life, a miracle never realized by artists until our century.

Caroline Leaf created her finest films at the National Film Board of Canada, a sympathetic but nonetheless corporate structure, in which she has managed to retain her individuality and personal signature. She is also a vital link in the list of women animators, designers and storytellers past and present who have made their way in a male-dominated field. From the simplest means she conjures a complex world of emotions, which is a talent found only in the work of the greatest artists. The transformation and alienation of a man turned into a loathsome cockroach; the variety of feelings triggered in family members by the imminent death of a loved one; the pathetic, ultimately self-destructive attempts of a lovesick owl to assimilate into a different culture; a small boy and assorted animals facing death in the form of an eerily omniscient wolf are some of the stories told with consummate skill in the films of Caroline Leaf. I’m so glad you’re here.

CAROLINE LEAF: I’m glad to be here.

CANEMAKER: I think that what’s extraordinary about seeing all your work together like this is to view your first film and to realize that it was all there—right at the very beginning. The good design, the sense of timing, and your whole bold approach to the medium is already there—your ideas about how to tell the story. That was your first film, wasn’t it?

LEAF: PETER AND THE WOLF (1969) is my first film. And I must say, I agree. I haven’t changed very much.

CANEMAKER: Grim Natwick always said that timing is the last thing an animator learns. It seems as if it was the first thing that you learned. Where did that come from? Were you trained in theatrics in any way?

LEAF: I’m not sure where it comes from. I think I make shapes and then try to keep them in balance. That’s my idea of how they move. I don’t know how to say where the timing comes from.

CANEMAKER: But you also know when to not make them move—you have a good sense about “holds.” When the cockroach was looking in the mirror, it went on and on, and you had the guts to keep it there without having it move at all.

LEAF: I’ve heard people talk about feeling the movement, and I know that I feel it. Sometimes I have to get up and act something out, or look in the mirror to see what it looks like when something happens. Working directly under the camera the way I do, there’s nothing between me and drawing the motion, and that helps with that. Intuitive expression of the movement, the timing. CANEMAKER: Let’s talk about story. In PETER AND THE WOLF, it’s very experimental. In many ways it is a first film because you get a feeling you’re trying to do a lot of different things. How did you approach the story in PETER AND THE WOLF? There’s just barely a theme of Prokofiev in the beginning —it’s all there, yet it isn’t.

LEAF: I’ve read a lot, and I’ve been most influenced by stories that I have some good gut feeling about. But then I like to go off and do my own thing with them. And on that film in particular—you’re right, I was trying to experiment; and the way I was working, I just had to divide things into segments. The ideas would evolve out of a little pile of sand and then go into wh’ite, and then a few days later I’d start a new sequence. So, it was pretty much the situation of wanting to use a story while not following it precisely.

CANEMAKER: And you use touches of personality, too: the little goose steps down but has a very particular way of doing it and it got a couple of laughs each time because it was so goose-like. Your characters have a lot of personality. Do you feel that personality guides story?

LEAF: Can they be equal?

CANEMAKER: Whatever you want! Anything you want, Caroline!

LEAF: I would say the story is important to me because it sets the limits and anything I do I don’t want to deviate from the feeling I want to generate from the story. The characters are the vehicles that express the stories, so they have to be right for each other. And I don’t indulge the characters, I don’t think, because I would get off track with my story, so I think I always sustain a line to keep the story moving along.

THE STREET (1976), adapted from Mordecai Richler’s story

CANEMAKER: Let’s talk about THE STREET (1976). How detailed was the original short story? Why did you approach it?

LEAF: I just liked the story, but there I had Mordecai Richler, a living person, a writer who lived not too far away from me, and I wanted to respect his writing. His story was maybe twenty pages, and at first I thought that to be respectful to the writer I should put everything onto film. And I found as I was working, the more I could pare away the words and just work with the imagery and be true to the feeling I was getting in the story, the better it worked on film. So there I was really trying to follow his story, but because film is a different medium, it came out in a different form.

CANEMAKER: Did you ever show it to him or did you confer with him during the making of it at all?

LEAF: No, he was strangely disinterested. He didn’t like the story too much, and didn’t care what I did with it, and never got in contact with me about it. I didn’t discuss it with him.

CANEMAKER: Did he ever see the finished film?

LEAF: I sent him a print and he never answered. I don’t know what he thinks of it.

A family beset in THE METAMORPHOSIS OF MR. SAMSA (1977)

CANEMAKER: What about Kafka? Was your approach to pare away and get the imagery first in THE METAMORPHOSIS OF MR. SAMSA (1977)?

LEAF: The Kafka story is so complicated and wonderful. There I took just the element of what I was thinking about most—how horrible it would be to have a body, or the external part of one’s self that’s seen by the world be different from what’s inside one’s self, and not be able to communicate that. Since I’m a storyteller, I just worked with that one aspect of Kafka, so it’s quite different from his original story.

CANEMAKER: You really get into your characters; the emotion is there, it’s really extraordinary, I think. It’s just great. (Audience applauds.) Caroline doesn’t like to be interviewed, but she’s consented to this, and I appreciate it. I’d like to talk about the animated projects you’re working on now. One of them is a scratch-on-film technique.

LEAF: I’m just in the midst of starting two projects, and because I’ve been involved with live-action filming for a few years, and writing for live-action, now I’ve got a story that has all the characteristics and psychology and emotion of a live-action film, but I’m doing the images scratching on film. It is quite a restricted and crude image that I can make, but I find it exciting to find what I can tell of the story in imagery and how much I’ll have to rely on words.

Autobiographical insight in INTERVIEW (1979), co-directed with Veronica Soul

And the other project is a test of a computer animation program. It’s a small project, a program called Pastel, that was developed by the Film Board. They wanted to see how an animator would work with it, and what modifications it still needs.

CANEMAKER: Exciting. So you haven’t abandoned animation.

LEAF: No. Not at all. I just have had a hard time sitting still and doing it.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: I noticed in INTERVIEW (1979) that you had all those little thumbnails to the left [of the work under the camera]. Is that how you work, really planning it out in little sketches like that?

LEAF: Yes, that would be my detailed storyboard as I go along. I don’t storyboard too closely; to have done all the fun work, and to animate it, there are no surprises left. But I also need to know where I’m going since I work under the camera. If I take a wrong turn I can’fgo back. So, as I come to each scene, I do some little sketches, particularly to know what the characters look like in different positions, so I don’t get lost.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Your soundtracks have a powerful impact on the film. How much do you get involved? Do you sound-mix, or do you direct the actors and the dialogue?

LEAF: I am very involved with my soundtracks, and I enjoy working on them very much. The soundtrack for THE OWL WHO MARRIED A GOOSE (1974) was the first one I really conceived and executed. But when I’m working at the Film Board, I’m not the mixer, and I’m not the recorder, usually. There’s a crew of people that do that for me.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: You’re able to tell a story mostly through images, yet in THE METAMORPHOSIS OF MR. SAMSA and THE OWL WHO MARRIED A GOOSE you alter the language. Why did you make those choices?

LEAF: The Kafka story wasn’t in the public domain and I didn’t have the rights to the translation, so I made up a kind of gobbledy-gook language for that. And the Eskimo film was not a language you understood, either. They were speaking the Eskimo language.

CANEMAKER: THE OWL WHO MARRIED A GOOSE is exquisite. Sometimes in animation there are images you want to continue on and on and on. That scene of the birds flying, and the sound of wings getting as big and close as they are, and then they’re flapping for a while in front of you. I could watch it for a long time.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: In that vein, I’d like to know how long you studied the animals to get their movements so perfect.

LEAF: I don’t study animals. I don’t go to the zoo. And in fact my movement isn’t very realistic. I think you can make it convincing. It fits the shapes, I think. I’ve never really looked to see how birds fly, and it’s kind of awkward in fact how they do, but it somehow works.

CANEMAKER: In several films you have a character who will take a step and then the legs would switch in some unnatural way—but somehow it works. In THE OWL WHO MARRIED A GOOSE I think there’s a section where that happens.

LEAF: I know it happens in THE STREET once — arms change . . .

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Why are you working in Canada? Economics?

LEAF: Yes, the Film Board is quite a special place. It’s allowed me to do the films that I’ve done, which I don’t think I could have done down here.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Because no one’s going to buy them? Or distribute them?

LEAF: It’s because of the problem with the distribution of short films. Ask any of the independent animators who’ve spoken here. Most of them are teaching, and it’s hard to have films seen. I found it is also hard at the Film Board. It’s difficult to have short films seen, and I’m not happy with the distribution, but I’m paid a salary there, and I’m quite free. Not totally free, because it’s a government film agency, and there are restrictions.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: What kind of restrictions?

LEAF: I find there’s a rather insidious way of thinking that grows on one working in a place like that. The most obvious thing is that it’s not possible to experiment; or it’s not easy to do an abstract film, because they’re always concerned about their market, which is an educational market. And besides that they’re very sensitive to not provoke any public outrage, or outcry, so they take a middle road. Nothing should be too controversial. I can read stories and know right away, this is something that could be done at the Film Board or not. One isn’t free to do exactly what one would like to do but one can mold it to be close enough to be satisfying.

Exquisite images of geese in flight in THE OWL WHO MARRIED A GOOSE (1974)

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Does the Film Board expect to make their money back on films?

LEAF: No. The income they receive from the films goes back into production, but the Board receives government money each year. They have an annual amount given to them from Parliament. It’s voted each year.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Has it been growing?

LEAF: It’s been shrinking in recent years. So the place has shrunk a lot. Just last year they were voted an increase, which might just bring them equal with inflation for the first time in a few years. But everyone takes it as a vote of confidence.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Who owns the films you made while you were on salary?

LEAF: The Film Board owns them. I don’t have any rights to them at all.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Do you think that your technique would be used in any major projects, for instance in a Disney feature?

LEAF: Well, I’ve seen my way of transforming used in eel animation. But actually the way I work, under the camera, I don’t think I can work as a team in that way. So it would be hard to make a long film using my technique, and get everyone working in a way that looks the same, This winter I did a commercial in New York, arid that was the first time I’d really found that my under the camera technique could work commercially. Because normally I would do some designs and then I would start, and I’d go to the end. And here I didn’t have any way to fit into the system of checks and balances that are used commercially. The client couldn’t see beforehand what I was going to do. But I evolved enough different systems of storyboarding that they felt reasonably secure, when I started animating, what they’d get when I’d

finished.

CANEMAKER: If it were possible to direct other people in your technique, would you be interested in doing a feature?

LEAF: No, I wouldn’t. I can’t imagine directing other people, and also I have a lot of fun when my fingers are doing it and I discover for myself little things. That’s what keeps me going. And I don’t know what it would be like, if it would be enjoyable to direct other people.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Have you ever used colored sand?

LEAF: I got tangled in knots one time trying to use colored sand. When you use colored sand—colored anything—you put a lot of time into keeping your colors separate, so they don’t all become like mud. And keeping colored sand grains separate was very difficult! I gave it up quickly.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Have you had students or apprentices pick up on your technique and pursue it in their own pictures?

LEAF: There are a few people that have worked in the same materials that I’ve worked in, but not as many as I’d like. And I haven’t had students. I haven’t taught.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Will you be working on a team for the computer animation?

LEAF: This is just a small project, and I’m alone with the guy that developed the program. We’re working together. He listens to my complaints and makes alterations. I’m amazed sometimes by what he’s done, but it’s not really a team.

CANEMAKER: I would like to thank Caroline Leaf for being here.

LEAF: Thank you for being here!

Articles on Animation &Bill Peckmann 05 Jul 2011 06:48 am

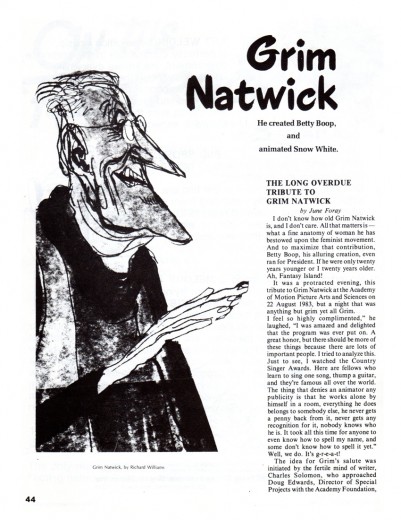

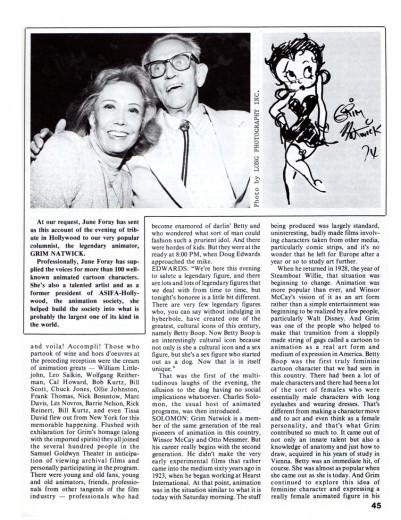

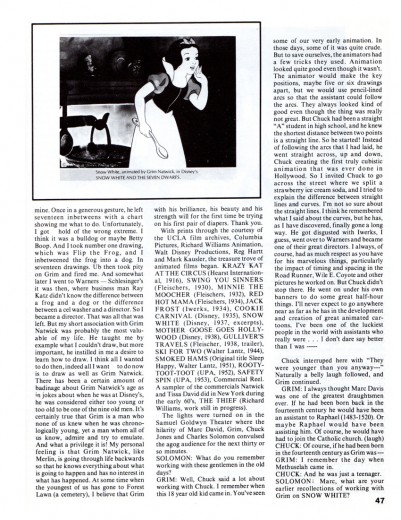

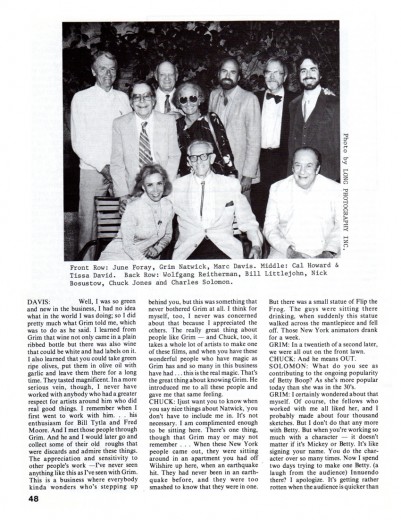

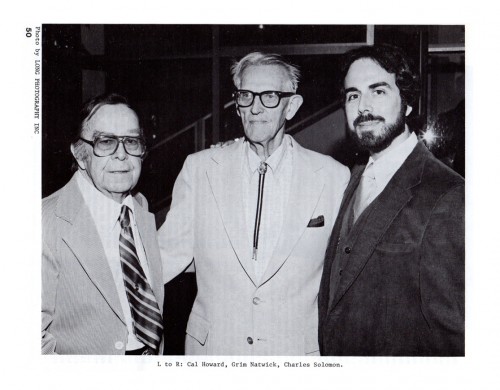

Grim by June

Articles on Animation &Bill Peckmann &Comic Art 28 Jun 2011 07:11 am

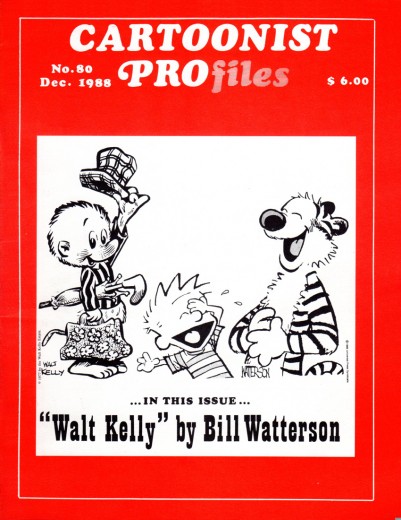

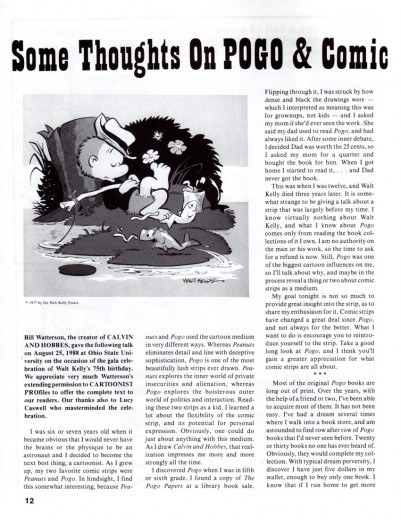

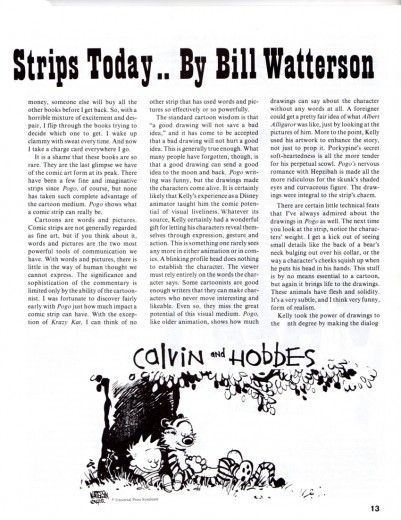

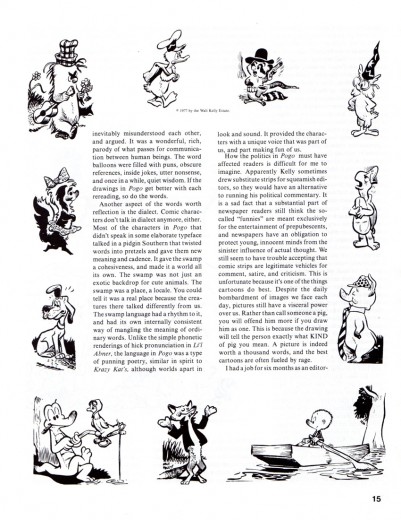

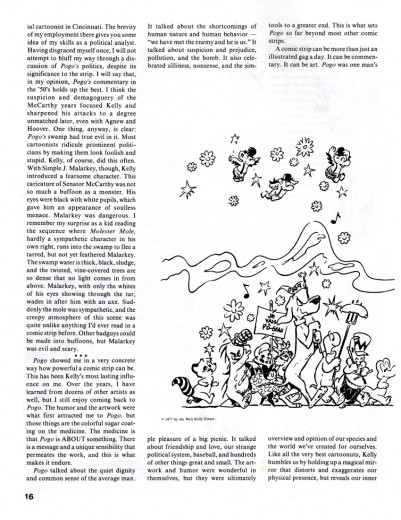

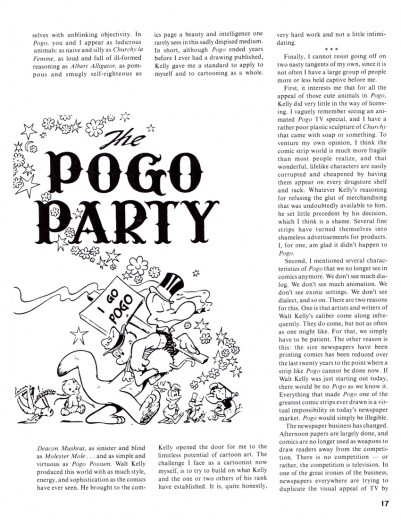

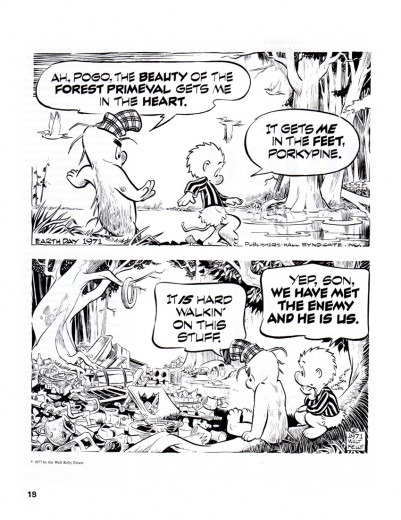

Kelly 1988

- Here’s an interview printed in Cartoonist Profiles Magazine in 1988. It’s Bill Watterson, of Calvin & Hobbes fame, of course, giving an appreciation of Walt Kelly of Pogo fame, obviously. It’s a gem of a piece sent to me by Bill Peckmann, and I’m posting it hoping you’ll find it interesting. Thanks to Bill Peckmann for sharing his incredible archives.

Cover

Action Analysis &Animation Artifacts &Articles on Animation &Disney 23 Jun 2011 06:56 am

Action Analysis – March 29, 1937

- I continue, today, with the Action Analysis notes from the lectures given at the Disney studio by instructor, Don Graham. The lectures were often built around film sequences that were screened. In this lecture, they screened a sequence from Charlie Chaplin’s Easy Street as well as an in-house loop of a man walking with two children.

The animation personnel who attended and participated on this lecture included: Reuben Timmins, Izzy Klein, Jacques Roberts, Bernie Wolfe, Chuck Couch, Jack Hannah, Amby Paliwoda, Bill Tytla, and Bruce Bushman.

Cover

If you enjoy reading these Action Analysis notes, there are a wealth of them on Hans Perk‘s wonderful resource of a site, A Film LA. Many of them from earlier periods than these that I’m posting.

Action Analysis &Animation Artifacts &Articles on Animation &Disney 16 Jun 2011 07:32 am

Action Analysis – March 22, 1937

- Today we continue with the Action Analysis notes from the lectures given at the Disney studio by instructor, Don Graham. The lectures, at this point, were generally built around film sequences that were screened. Oftentimes they were past Disney films, other times they were live action sequences from other studios. In this lecture, they were scenes from the Clark Gable feature, San Francisco. (This can be rented from Netflix or other distributors or can be often seen on TCM.)

The animation personnel who attended and participated included: Izzy Klein, Joe Magro, Jacques Roberts, Jimmie Culhane, Bill Tytla, Eddie Strickland, Bill Shull Moe Gollub (misspelled as Gallub) and Bernie Wolfe.

Cover

15

15