Category ArchiveGuest writer

Animation Artifacts &Articles on Animation &Guest writer &Photos 13 Aug 2008 07:51 am

Irv Spector – I

– Not too long ago, Paul Spector and I had an email conversation about his father, Irv Spector.

– Not too long ago, Paul Spector and I had an email conversation about his father, Irv Spector.

Irv was an animator that I knew periferally in New York during my first days in animation. We saw each otherat Union Meetings and some animation events in New York, but I didn’t really know about his start and key days in the business.

I jumped at the chance to ask Paul to share anything, anytime with this blog, and I’m pleased and excited to post this first entry from him.

__(Click any image to enlarge it.)

In 1941, during WWII, my father was an animator at Flesicher Studios in Miami, FL. At the the time, many cartoonists were being drafted into, or enlisting in, the miltary. Knowing he would soon be one of them he left Florida and drove across the country back to Los Angeles — where he was already registered for the draft — to push up his induction. (He began his career in LA at Mintz and Schlesinger, before taking a job with Fleischer when they were still located in New York).

Like a lot of other cartoonists my dad was assigned to the animation unit of the Signal Corp, making training films and other industrials; in his case back at the east coast unit.

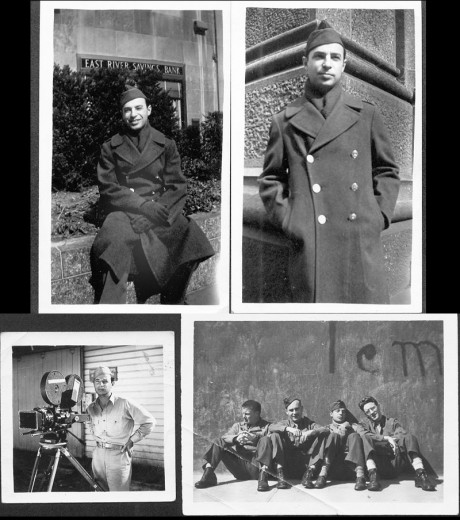

In this photograph, my father is second from the right.

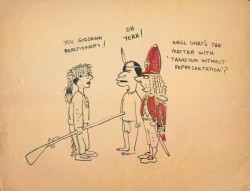

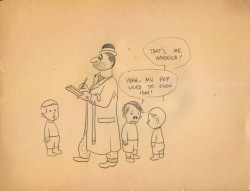

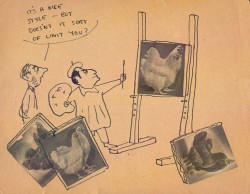

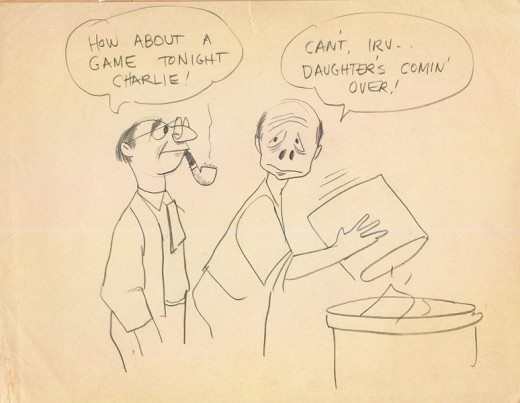

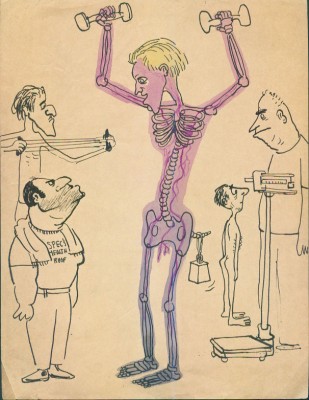

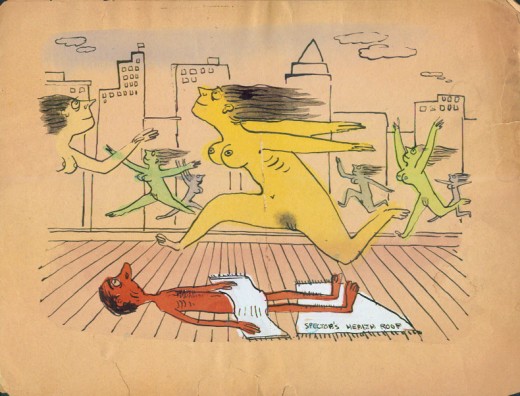

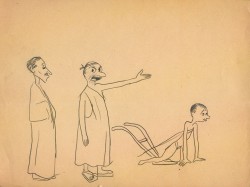

While many of these films incorporated animation as well as live action and photography it was not just those in the animation field who worked in the Corp. Although those of us with an interest in the animation field tend to focus in on that aspect, the Corp also produced pamphlets and manuals, etc. One of these non-animation inductees was Sam Cobean whose illustrations appear in many of the images below. Some of the most striking are done by him. A quick note about Cobean: during the war he was taken under the wing of The New Yorker magazine cartoonist-extradinaire Charles Addams, who introduced him to the editors at the magazine. Cobean soon began publishing there, and his star rose quickly through the post-war years until he was tragically killed in an automobile accident in 1951. The majority of those below came out of a manila envelope with “Sam Cobean, Bob Perry, Others” written on it. Several others were from untitled envelopes. Very few are signed by the artists, although you’ll notice several that are, especially two straighter drawings by the magnificient Lars Colonius. However, the vast remainder are pretty much gags and caricatures. Mostly funny, ludicrous, or just really nice to look at.

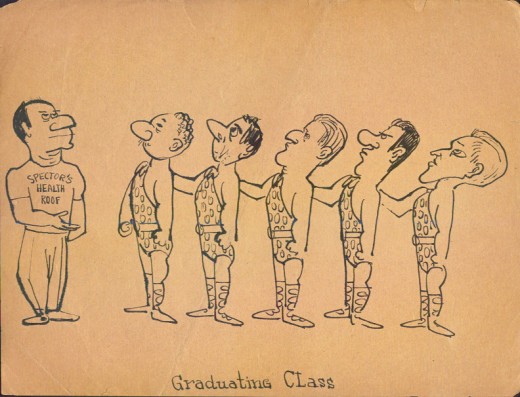

Some poke fun at army life, but most of all they lampoon my dad, who appears in almost all of them along with a cast of other cartoonists in the unit. (But whose else would I have? Naturally, about 98% of what I have is his work. This is the other 2%). The joke in some of these is that my father began to lift weights in the army, hence the drawings where he is muscled, or the mention of “Spector’s Health Roof”, or referred to as Simian(!) Here is are some real photographs of my dad in those years, so you can get a fix of what he really looked like then. Make sure you scroll down, and maybe someone out there can identify the three other gents in the image of them sitting along a wall (my father is second from right, with his eyes closed.)

Irv Spector

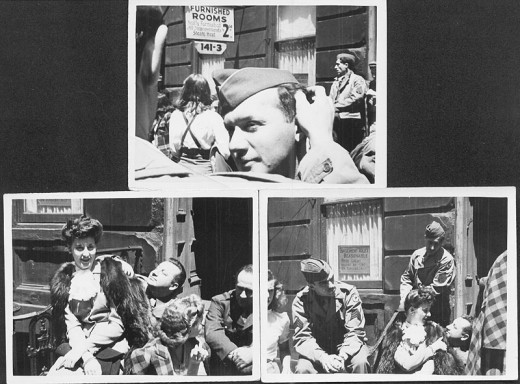

I’ll leave it up to all of you to try and identify anyone depicted throughout. One who is obvious to me is animator Herman Cohen, a longtime friend of my dad’s and our family in general. Here are some photographs on him — that’s his wife Juliet sitting on his lap.

An anecdote about Herm: In the mid-late 1960s, Herm and one of his sons, and my dad and myself, were shooting pool at our house. On one of Herm’s turns, we watched him take his cue stick and line it up by the 1-ball, sizing up angles. However, when it was time to take the shot, he actually hit the 1-ball with his cue — as if it were the cueball — to sink another ball. A moment later my dad says, “Hey, I forgot all about it. Herman is color blind!” Yep, Herm mistook the solid yellow 1-ball as the cueball. Just goes to show there’s hope that you too can have a lifetime career as a respected animator without being able to identify colors.

(Here are a few more of Irv’s caricatures of the period.

None of them have any background info on them.

If you can ID any of the people, please feel free to comment. MS)

Health Roof

For the historians out there: There seems to be a dearth of information on the internet regarding the Signal Corp Animation Unit, east coast and west. If it helps, I’ve pieced together some of my father’s own moving around — date-wise, using some of the mail he received during this time. Maybe this info can be extrapolated…I dunno, but perhaps it can help.

- April 1942: Bob Givens (also in the service) writes him at Ft. Monmouth, NY (from Ohio).

August 1942: Givens writes him c/o of the Signal Corp Animation Unit at Long Island City, NY (no return address).

September 1942: Jack Rabin (just about to be inducted) writes to him at the Training Publications Dept. of the Anti Aircraft School, Camera Crew Unit #1, at Camp Davis, NC.

July 1943: Written to at the Signal Corp Photographic Center on E.32nd St., NYC, NY.

Jan/Feb, 1944: Carmen Eletto writes to him, again at the Signal Corp Photographic Center on E.32nd St., NYC, NY.

Here’s an undated item from the TAG blog. Givens is in it, at Ft. Monmouth. So, pre-April ’42 maybe? Before he was shipped out to Ohio, of all places.

More images will follow on Friday.

Articles on Animation &Commentary &Guest writer &Independent Animation 12 Jul 2008 08:23 am

Guest writer: Why Cartoons?

– I received the following article from Nina Paley, the creator/animator/ director/designer of Sita Sings the Blues (which won the Best Feature Prize at Annecy this year.) The article came with a letter, which I think helps explain why she wrote it.

– I received the following article from Nina Paley, the creator/animator/ director/designer of Sita Sings the Blues (which won the Best Feature Prize at Annecy this year.) The article came with a letter, which I think helps explain why she wrote it.

Here’s the letter:

- Hi Michael,

I’m back in NY, finally, spending my first day home in my apartment with the AC on with the cat next to me, surfing the web. I read your review of Wall-E, which I haven’t seen yet, and thought to send you this essay I wrote for Frederator (which they never used) on the theme of “Why Cartoons?”.

Since Berlin, I’ve been convinced that most cinemagoers are simply voyeurs, craving simple stimulation of their primate visual senses in the form of close-up views of beautiful people courting and mating, and gory violence. Things our inner primates think about constantly but seldom get to see. Animation is more abstract and cerebral, visually. I prefer it to live action, but I am a freak (like most animation fans).

Pixar’s success lies in making animation that visually resembles live-action and satisfies the typical cinemagoer’s inner voyeur. Hence the expanding popularity of 3D “animation” among Hollywood producers.

Typical American cinemagoers are put off by 2D animation, but 3D gives them more of what their primate eyes want: to believe they’re watching real events up close without risking personal exposure.

Since I’m going to a lot of festivals with “Sita,” I am struck by the cultural differences between animation festivals and “real” film festivals. When I refer to films as “live-action,” most directors don’t know what I’m talking about; to them live-action is just “film,” and animation is completely off their radars. Most have never heard of Annecy or any other animation festivals. Most film festivals automatically exclude animation from competition, instead programming it in what I call the Animation Ghetto – or worse (in the case of “Sita”), the “Family” or “Children’s” sections. But their programming animation at all is evidence of some progress. And I’m grateful, especially for the 2D animation fans that already exist, and the chance to expose new viewers to the art form.

Hope you’re well,

–Nina

This is the article she sent.

- WHY CARTOONS?

Because less information = more meaning

Animation takes advantage of quirks of human perception. Good cartoons lie somewhere between nature (no abstraction) and text (full abstraction).

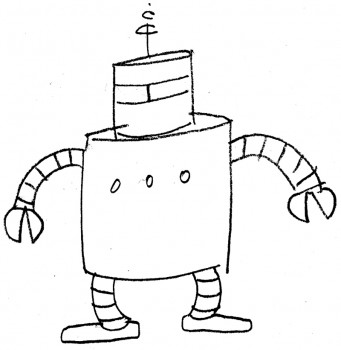

At its best, animation does what live action can’t. Good animation is unrealistic. This starts with the style itself: drawings and designs of things that can’t exist in the real world. Exaggerated heads and hands, huge or tiny eyes, rubber-hose limbs, cubism. A handmade line drawing of a robot requires our uniquely human imaginations to understand it as “a robot,” but we may recognize it more quickly than a photograph of a real robot.

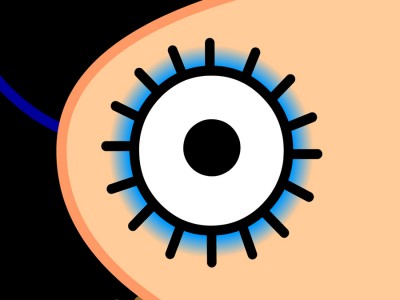

Exhibit A: cartoon drawing of a robot.

Animated motion should also defy reality. For example, bouncy walks that no robot (or human) could replicate, even though we can recognize them as “walks.” Good cartoons stimulate and exercise our imaginations in ways live action never can.

Like reading or working out, viewing cartoons can be exhausting. But far less time is needed to communicate more meaning. That’s why cartoons are so effective as shorts (and commercials).

Live action conveys too much information. “High production values” are the art of removing as much information from nature as possible.

Wrinkles and blemishes on actors’ faces are concealed with makeup; stray threads and hairs are tucked away by stylists; wires and microphones hidden through camouflage, meticulous set design and framing; unwanted details lost in shadows via careful lighting, which heightens only those few areas and outlines intended to convey meaning. But still, excessive information abounds in live action.

Cartoons start with only the information needed. There’s nothing extraneous to hide. If you mean “eyes,” you show a symbolic short-hand representation of “eyes,” nothing more. No gunk in the corner of the eyes, no moles on the eyelids, no eyebrow dandruff – unless you explicitly intend to convey these details as well. The picture is as clear as the idea in the mind of the artist, and that clarity of meaning is transferred to the viewer.

Exhibit C: real eye, belonging to the author.

Notice bloodshot veins indicating stress, wrinkles indicating wisdom and maturity,

shiny skin surface indicating absence of makeup, and other excess information.

(Also, producing animation totally trumps live action: No uppity actors. No obnoxious crew. No permits. No tedious laws of physics. If you can imagine it, you can animate it; no extra charge.)

But animation remains the bastard child of cinema. Most moviegoers just want to watch beautiful people. Bonus if the beautiful people are celebrities; extra bonus if the beautiful people are performing sex or violence onscreen. Animation can deliver meaning, story, ideas – but it doesn’t satisfy the sexual voyeur that drives most cinephiles. In live action, a camera can linger for minutes on a beautiful actress’ face, as the audience attends to all that information: every eye-blink, every change in pupil dilation, the subtlest nostril flare, the slightest movement of any of the hundreds of facial muscles lurking below the makeup. In live action, such a scene is watchable. How could such a serious and pensive scene be conveyed in animation? It would either be painfully dull (a long still) or ridiculous (imagine a Bill Plympton interpretation where every nuance is exaggerated: small nostril flare becomes huge, facial muscle twitch becomes twitchy animal running around under skin) and, like all animation, exhausting.

Live action satisfies our voyeurism, animation ridicules it.

Since I can’t take voyeurism seriously, I go for ridicule.