Monthly ArchiveJanuary 2010

Articles on Animation &Independent Animation 21 Jan 2010 08:29 am

Len Lye

- Len Lye, one of the original experimental animators, has rarely gotten the acclaim from the animation community that he has certainly deserved. Rarely is his name mentioned in animation books or articles. As a matter of fact, in more than 50 years of reading about animation, I can only remember two significant magazine articles about the man and his work that appeared in animation magazines. (If you really go looking you’ll find a lot written in art publications – not animation mags.)

Here, I’m posting one fof those two that I think is a significant and clear article, and I hope it will give the man another five minutes of your attention. The article was written by Joseph Kennedy for the February 1977 issue of Millimeter Magazine.

by Joseph Kennedy

Len Lye‘s Greenwich Village loft is an airy workshop, filled with the tools of the artist’s trade: machine saws, diagrams, models of projected works, and several silvery kinetic pieces glistening in the summer afternoon’s light. Len Lye himself is the Renaissance Man of the avant-garde, his prolific skills having manifested with equal success in diverse media: sketches and paintings, eel animation, paint of film, live-action films, essays and kinetic sculpture. Always the innovator, he has never bound himself to one mode of expression, choosing instead that which best suits his creative need.

Len Lye‘s Greenwich Village loft is an airy workshop, filled with the tools of the artist’s trade: machine saws, diagrams, models of projected works, and several silvery kinetic pieces glistening in the summer afternoon’s light. Len Lye himself is the Renaissance Man of the avant-garde, his prolific skills having manifested with equal success in diverse media: sketches and paintings, eel animation, paint of film, live-action films, essays and kinetic sculpture. Always the innovator, he has never bound himself to one mode of expression, choosing instead that which best suits his creative need.

For more than 50 of his 75 years he has pursued his quest of motion composition. As a teenager in Wellington, New Zealand, he had his first glimpse of the potential of this art form while delivering newspapers at sunrise. His attention was caught by the movement of clouds and he began to ponder creating artificial clouds to achieve that same quality of motion. “I thought then and there, ‘Why clouds? Why not try to compose motion yourself? — compose motion!”

After this “revelation”, he found the idea was not so easy to implement. “I tried to control motion, and I nearly broke my back. Christ, how do you? So I worked out shafts and handles that could be turned and stuck through shafts so the turning shaft could turn the particular stuff you’d stuck to it; and it was a crazy kind of attempt to control motion and compose it. I was having a ball nevertheless.”

Hoping to learn more about film, Lye moved to Australia in 1922, because New Zealand had no cinematic equipment. He worked at a Sydney studio that made animated advertising shorts. “I learned animation in Sydney, not too much because I was doing storyboards. But I took the job just to be around where people were handling film, just to see.”

Here he chanced upon the concept of “cameraless animation”: “I didn’t invent scratching on film. I saw some guys that had made some marks on it and I rather liked the way they went (through the projector) wiggling like that, you see. I scratched a few feet of film myself, so I kept that in the back of my mind. And then I saw something like it again from a German film crowd. I think it was also some kind of scratching that they did on film. I kept that in mind too.”

Here he chanced upon the concept of “cameraless animation”: “I didn’t invent scratching on film. I saw some guys that had made some marks on it and I rather liked the way they went (through the projector) wiggling like that, you see. I scratched a few feet of film myself, so I kept that in the back of my mind. And then I saw something like it again from a German film crowd. I think it was also some kind of scratching that they did on film. I kept that in mind too.”

These experiments inspired him to adapt his own kinetic works to cinematic technique: “I suddenly realized that films had cuts and sequences. Editors can chop it where they want to. So, instead of having handles and shafts to control motion, I could just swing (objects) on a string or hold them in a black velvet glove against black velvet or whatever; you could really control and make things happen in terms of sequential motion.”

The Russian Revolution had at first created an amazingly fertile environment for the arts, and for the first time film was being considered from an artistic rather than a commercial viewpoint. Later came barbaric suppression. Lye originally planned to travel to Russia, where he hoped to get a job with the Meyerhold Theatre. He worked his passage from Sydney to London on the White Star liner EURIPEDES as a stoker, arriving in 1926. Some fortunate events enabled him to remain in London to work on his first film, TUSALA VA. “I got all sorts of fabulous help that nobody would get now. For example, as a kind of caretaker, I got a rent free barge to work on, plus the use of part of a studio to which the barge was moored on the Thames. I got a promise from the first film society in the world (London Film Society) that they would pay for the photography. And so I settled down for two years worth of animation drawings.”

One of Lye’s early stylistic influences was primitive African and South Seas tribal art. “When I first came to London I didn’t quite know what sort of imagery would carry my figures of motion. I had lived in Australia and often wondered what on earth an Aussie ‘aboe witchitty grub’ dance looked like. To get the spirit of the imagery I also imagined I was myself an Australian aboriginal who was making this animated ritual dance film.” The articulated grublike forms in TUSALA VA are reminiscent of designs on aboriginal shields, but they are dynamic moving forms. The animation was painstakingly tedious. “These goddam grubs were animated sideways, like cogs in a bicycle chain. Each cog had to be animated separately. And there were about 20 of these bloody cog-links, they all had to be animated. Why the hell I picked on that I don’t know. Well, I just plodded on, about 16 hours a day; it turned out to be both the slowest motion and the slowest animation on God’s earth!”

TUSALA VA was received rather coolly after its 1928 premiere. “Except for the art critic Rogar Fry, there was just a big silence, a complete and utter silence.” Lye found himself without the means or the support to produce another film by eel animation, and he began to consider animating without a camera, recalling his Australian experiences. “I had already used up all my goodwill stuff with the Film Society. I didn’t have much spare cash and I used to go out to some friends in Baling Studios, London, and hang around — anything to get a job in films. I used to get the old n.g. sound takes, that is, clear film with just a skinny track on one side. I would then scratch and paint and mess around with these bits of film. I would join them together and take them up the GPO Film Unit where I had some friends and run it. All this was done under the counter, you know, on lunch hours.

“I hit some marvelous effects (with) wet paint on a strip of clear film; for instance, you take an ordinary fine tooth comb and just wriggle it as you go down the length of film in the wet paint and it makes a lot of striated wavy lines. So you run it. With all these fancy abstract designs going on, the film had a very peculiar abstract quality. I was very taken by it, but didn’t have much chance of developing it.”

With the help of a composer named Jack Ellit whom Lye had met in Australia (“he was the only fellow there of the whole lot of people I knew who had any understanding of contemporary art”), he ran his film to a catchy recording of a Cuban beguine. He presented it to John Grierson and Alberto Cavalcanti at the British Government’s Post Office Film Unit. He suggested they add some slogans to the end of it. Then, with the help of Ellit, he synchronized his painted film and turned it into a public service film; and so COLOUR BOX was released in 1935, informing delightful audiences about new low parcel post rates. “A Utopian bit of public service,” thinks Lye.

The success of COLOUR BOX resulted in subsequent films for the GPO: RAINBOW DANCE (1936), TRADE TATTOO (1937), and MUSICAL POSTER ttl (1939); as well as several advertising films: KALEIDOSCOPE (1935), for Churchman’s Cigarettes and COLOUR FLIGHT (1939) for Imperial Airways. All these films have in common the abstract “cameraless” technique used in COLOUR BOA’as well as an infectious synchronized score taken from classic jazz and Latin recordings.

The success of COLOUR BOX resulted in subsequent films for the GPO: RAINBOW DANCE (1936), TRADE TATTOO (1937), and MUSICAL POSTER ttl (1939); as well as several advertising films: KALEIDOSCOPE (1935), for Churchman’s Cigarettes and COLOUR FLIGHT (1939) for Imperial Airways. All these films have in common the abstract “cameraless” technique used in COLOUR BOA’as well as an infectious synchronized score taken from classic jazz and Latin recordings.

TRADE TATTOO is Lye’s most ambitious film (“That one’s got to be the most complex film ANYBODY’S ever done”). Lasting but six minutes on screen, it employs some of the most sophisticated editing, montage and processing effects yet seen. Using black-and-white footage from GPO documentaries, Lye combines stencilled patterns, titles and animated effects to form a brilliant montage. Each of the four layers of images that make up the final print had to be exposed three times via the old 3-color Technicolor process, requiring a total of 12 separate processes to arrive at the final color print (“the lab went crazy”). In addition, the footage was tightly edited, employing jump cuts and color reversal to synchronize with the highly percussive Rhumba and Conga beat of the score; once again, Lye was assisted by Jack Ellilt as music director. As one can imagine, the total effect is startling. Even today, some 40 years after its conception, its avant-garde approach still seems fresh and contemporary, capable of rousing an audience to cheers.

Len Lye turned his hand to live action films, directing several shorts for the GPO. In 1944, he was invited to America to direct films for the “March of Time”. Although his 1958 short abstract film FREE RADICALS won the Silver Medal at the Brussels World’s Fair, Lye began devoting more of his time to kinetic sculpture. “My type of film, which is a short film, might take me eight months; and it’s very definitely fine art, not folk art in any shape or form. I take eight months to make five minute’s worth of film. Nobody is going to pay me for any of those eight months. And in any case, it’s a pain in the neck to have a five-minute film. How’s it going to be laced up and tied in with the rest of the program? People go to a movie house to see a program of at least ninety minutes, and they couldn’t care less whether they miss a five-minute fine art job. So my films were a complete anomaly.”

Len Lye turned his hand to live action films, directing several shorts for the GPO. In 1944, he was invited to America to direct films for the “March of Time”. Although his 1958 short abstract film FREE RADICALS won the Silver Medal at the Brussels World’s Fair, Lye began devoting more of his time to kinetic sculpture. “My type of film, which is a short film, might take me eight months; and it’s very definitely fine art, not folk art in any shape or form. I take eight months to make five minute’s worth of film. Nobody is going to pay me for any of those eight months. And in any case, it’s a pain in the neck to have a five-minute film. How’s it going to be laced up and tied in with the rest of the program? People go to a movie house to see a program of at least ninety minutes, and they couldn’t care less whether they miss a five-minute fine art job. So my films were a complete anomaly.”

Nevertheless, Len Lye is still deeply involved in the creation of a new iconography, encompassing all the arts — a new understanding of the relationship mankind, myth, and creativity have in the scheme of life. “I think Art is the only way you can isolate the creative essence of humanity. This essence, like happiness, is individuality. Civilizations and religions may fall down the drain, but their arts remain. It takes the avant-garde to best symbolize the vitality of creativity. There are a lot of great parallels between great, or everlastingly evocative, happiness and great art. This relationship is mainly about value — human value, and it can teach us how to get the most out of ourselves, and life, that we can.”

Photos:

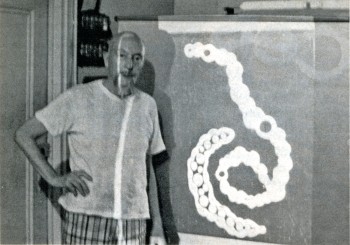

1. Len Lye and a slide from Tusalava (1928) (Photo by John Canemaker)

2. Trade Tatoo by Len Lye (Courtesy of Cecile Starr)

3. Rainbow Dance by Len Lye (Courtesy of Cecile Starr)

4. Joseph Kennedy (L) interviews Len Lye (photo by John Canemaker)

Joseph Kennedy is a New York City schoolteacher and a freelance writer. He has taught film history at Regis High School and he reviews films for Film news.

The magazine gave the above short bio about Mr. Kennedy in the Contributors column. Joe is a friend, and I am aware of how limited this makes his work seem (given that it was written in 1977.) He subsequently became a public relations executive and now has his own corporate communications practice; he worked with John Canemaker and Peggy Stern on The Moon and the Son and Chuck Jones: Memories of Childhood.

There is more information about Len Lye at several websites.

The Govett-Brewster gallery gives some good information about the man and his work.

Senses of Cinema offers an extensive bibliography of books and articles about the man.

Several of his film are available on YouTube (of course) in slightly degenerated versions:

Color Box

Swinging the Lambeth Walk

Particles in Space

Kaleidescope

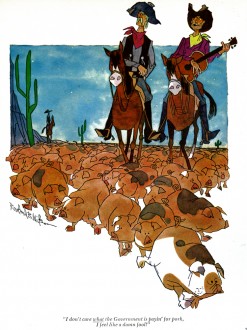

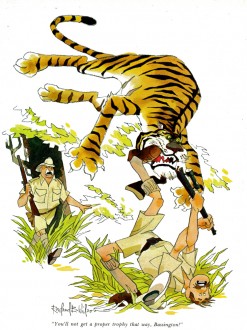

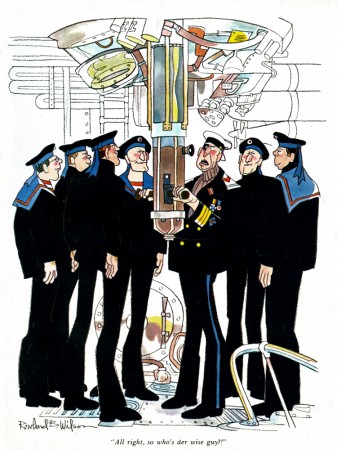

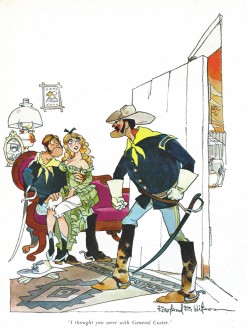

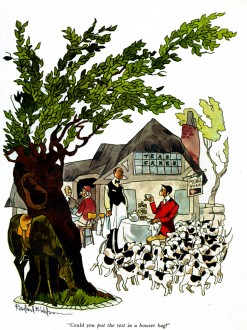

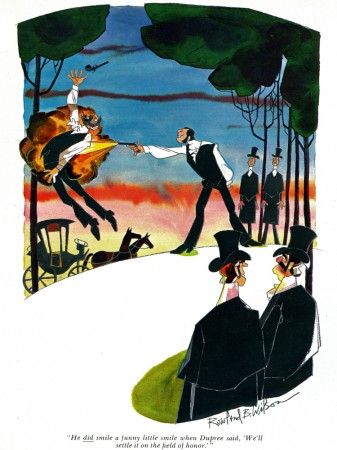

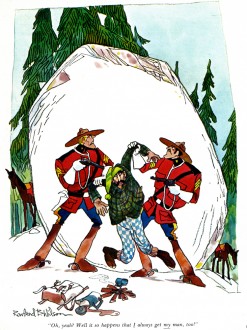

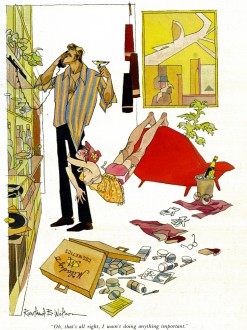

Bill Peckmann &Comic Art &Illustration &Rowland B. Wilson 20 Jan 2010 08:49 am

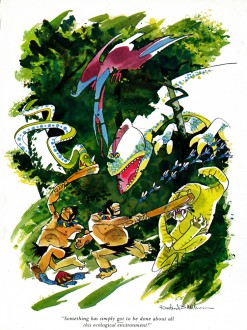

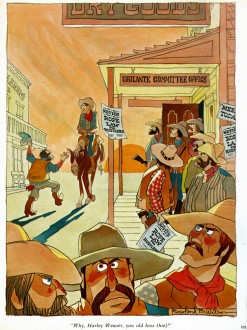

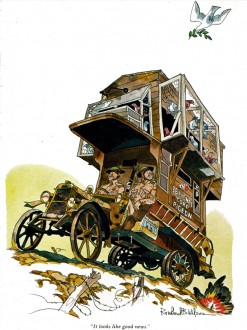

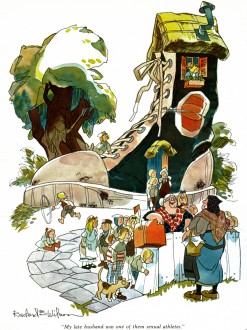

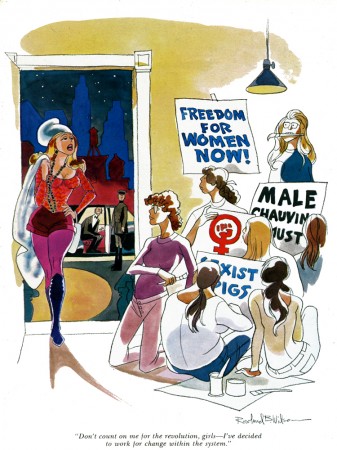

RBWilson Gag Cartoons – 1

- Back in the innocent years, the joke was that one read Playboy for the articles, not the pictures. In my case (and I’m sure it was true for many others), that wasn’t much of a joke. I did thumb through Playboy and it was for the pictures – the pictures by Rowland B. Wilson, Gahan Wilson and a couple of other of the great cartoonists of that magazine.

Bill Peckmann has saved a number of Rowland Wilson’s cartoons, and I’m eager to post them. It’s my pleasure that Bill has a small archive of Rowland’s material. He was an enormous source of inspiration for me, and it’s my joy to see a lot of these again. It’s amazing how many I still remember after all these years.

1

1(Click any image to enlarge.)

SpornFilms 19 Jan 2010 09:19 am

Meeting Ray Seti

- I promised back in Dec 2008 that I would tell the story of how I met Ray Seti. He was a very nice, very experienced guy who had his own, small, one-man studio back in 1971 when I entered the world of film.

But first I have to back track to the point where I entered the business. I had a long hard time getting into the Hubley Studio (this is a long-ish story that I’ll tell another time, if I haven’t already.) When I’d gotten out of the Navy in October 1971, I was unemployed, and had just started to receive unemployment checks. I was receiving $72 a week for a couple of weeks when I’d done a mass-mailing of intro letters to every name in the Backstage Annual of studios that listed themselves as doing animation.

Back in those days, there were no computers, and copies were Xeroxes done on a shiny, coated paper. You couldn’t send copies of letters to many people without individually typing them up. So I did. I wrote and typed about a hundred letters to all these different studios, knowing full well that only about a dozen or two really did animation. A lot of small studios credited themselves as doing animation rather than lose a job. After all, how hard was it for them to hire people to do the work, if it actually came their way? But, what the hell, if one of those studios wanted to hire me, I’d prefer the work than the unemployment check.

The day after I dropped those letters into a mailbox, I got a call from Hal Seeger, himself.

Seeger was an ex-Fleischer animator, production manager who’d set up his own studio in the early 60s and did Out of the Inkwell, Milton the Monster and Batfink cartoons. Now he actually had a bunch of studios all under the one umbrella called Channel Films.

My letter to these studios was humble enough. I said I would do anything to work for them including mopping the floors. Seeger introduced himself and then asked, “Did you mean it?”

I had a job. It paid $10 less than unemployment. I was a runner for the company. This meant I would help out editing as much as I could (they were doing a lot of work for ABC films.) My first job was to cut the commercials out of 120 episodes of The Smokey the Bear cartoon shows that were going to be sent to South America. By the end of that day I knew how to hotsplice, and my wrists were sore.

I had a job. It paid $10 less than unemployment. I was a runner for the company. This meant I would help out editing as much as I could (they were doing a lot of work for ABC films.) My first job was to cut the commercials out of 120 episodes of The Smokey the Bear cartoon shows that were going to be sent to South America. By the end of that day I knew how to hotsplice, and my wrists were sore.

I spent a lot of time at labs (learning the lingo and the insider view of the labs), mixes (meeting big time sound mixers and seeing how it was all done) and working in Channel Sound helping Roy Valle create sound effects. Roy had worked at Paramount cartoons making S/Effx and had brought the Maurice Manne library with him to Seeger’s studio. I also did a lot of transferring from 1/4″ tape to 16 & 35mm mag tape.

Oh yes, I also swept the floors once a day and mopped once a week.

Lenny Bird was the guy at Seeger’s studio. He pretty much ran it, and he edited all those docs for ABC Sports and edited local trailers for NY’s Monday Night at the Movies. (Then it was Tues, Wed, Thurs etc. Night at the Movies.) I assisted Lenny in the editing, mostly 16mm. He taught endless amounts of film craft and really took me under his wing for the time I was there.

One night, Lenny, knowing I was interested in animation, said he was going to do some freelance work and wanted to know if I wanted to go with him to meet an animator, Ray Seti. I was there. Ray’s studio was literally around the corner. We were on 45th St; he was on 46th St.

It turns out Lenny had taken some freelance work editing a porno feature. Ray was lending his space (and editing equipment) to his friend, Lenny, to help out.

I spent a good hour talking with Ray. He was a brilliant draftsman whose animation business had reduced to his doing animatics for commercials. They would do these test commercials, then test them. If they worked, the films were made; if not, the agency didn’t spend millions. Ray had become the king of the commercial animatic in NY. He did all the work by himself and made a comfortable living.

After the hour’s chat, I said goodbye to Lenny and Ray and went home. Ray’s final advice to me for getting ahead in animation was to move to California.

I got to meet other animation people via the Seeger studio. Hal Seeger, of course, would infrequently tell me stories about the old days. He was a pretty big person in his telling, so I’m not sure how much truth was there.

Myron Waldman would come in a couple of times a month. He used Seeger’s space as his own NYC office and would work out of there. He and Seeger were close and did a couple of small jobs during the time I was there.

Myron Waldman would come in a couple of times a month. He used Seeger’s space as his own NYC office and would work out of there. He and Seeger were close and did a couple of small jobs during the time I was there.

Seymour Mandel operated and serviced the three fully functioning Oxberry cameras that Seeger had in the space. He was an old Paramount cameraman and

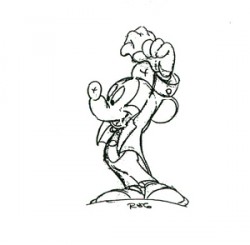

I practice inbetweened this ugly scene while at Seeger’s______had worked with Seeger since the early 60′s. He had a lot of free time and would answer my questions if I could get him in a good mood. The trick was that he was usually pretty cranky.

Six months later, I was about to be promoted to a full-time Assistant Editor. I said NO. It was all right to do it in the job I’d had, but actually doing the Titled job meant I was on the wrong career path. I wanted to be an animator and I had to quit.

This meant taking a gamble. It paid off in three months when the Hubley Studio came through. It gave me three day’s work that turned into a career.

Ultimately, Seeger folded his company into a bigger venture, Today Video. It was run by Beverly, his wife, and David, his son. I used their facility often (and never got a discount). Leny was the production coordinator for the tape house, and stayed with them until he retired somewhere in the early ’90s.

Animation &Bill Peckmann &Disney &Models 18 Jan 2010 08:46 am

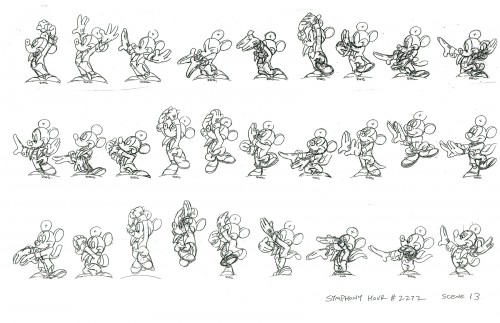

Symphony Hour – sc 13

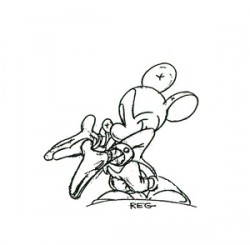

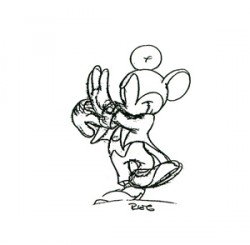

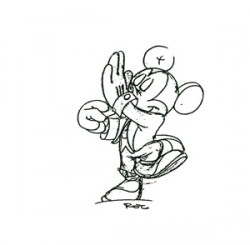

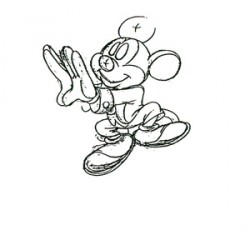

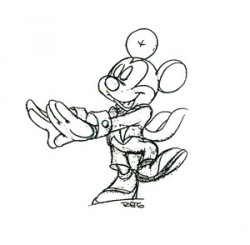

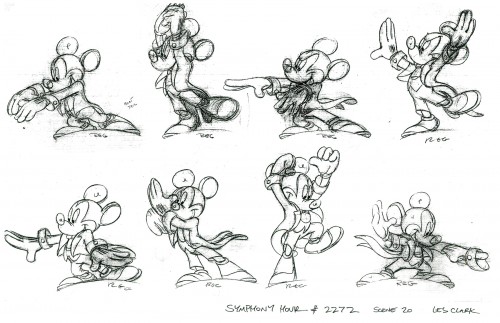

- Bill Peckmann had sent me a couple of model sheets from The Symphony Hour. I’m posting two of them below; one is taken from Scene 13, the second from Scene 20. Both scenes were animated by Les Clark, and, as was to be expected, he employs more drawings than those posted on the model charts. Inbetweens fill it out.

- Bill Peckmann had sent me a couple of model sheets from The Symphony Hour. I’m posting two of them below; one is taken from Scene 13, the second from Scene 20. Both scenes were animated by Les Clark, and, as was to be expected, he employs more drawings than those posted on the model charts. Inbetweens fill it out.

You might want to check out Mark Mayerson‘s mosaic and comments on this film.

(Click any images to enlarge.)

These are the two charts as printed.

The following is more of an enlargement of Sc. 13.

In putting together a rough QT of the piece I put everything on twos

which, roughly, matches the length but not the beautiful timing.

It’s designed only to give an idea of the flow of the action.

Right side to watch single frame.

Books &Photos 17 Jan 2010 08:50 am

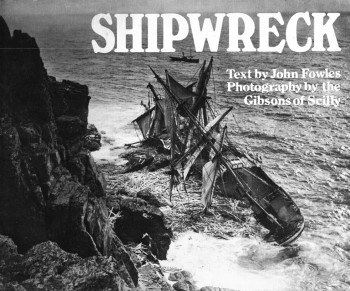

Shipwrecks

- By far one of my favorite writers was the British author, John Fowles. I enjoyed The Magus, but with The French Lieutenant’s Woman he had me as more than a fan. His language, his intellectual arguments, his absolute respect for his reader all brought me back again and again to follow his every word. I spent time with a specific retailer in New York who specialized in Fowles’ books to make sure that I wasn’t missing anything that he published.

- By far one of my favorite writers was the British author, John Fowles. I enjoyed The Magus, but with The French Lieutenant’s Woman he had me as more than a fan. His language, his intellectual arguments, his absolute respect for his reader all brought me back again and again to follow his every word. I spent time with a specific retailer in New York who specialized in Fowles’ books to make sure that I wasn’t missing anything that he published.

In 1985, on a vacation in London, I found a translation Fowles did of a French play, Martine by Jean Jacques Bernard, playing at the National theater. I hastily bought a couple of tickets to the show at the last preview, just prior to the play’s opening. Arriving early, there was an hour to kill before going into the theater. Fortunately, some vendors had set up book stalls selling used books, and I pleasantly sorted through the wares. Looking up from a book of Edmund Dulac’s illustrations, I saw John Fowles an aisle away. I was too timid back then to introduce myself and shake his hand. I just gloried in the knowledge that he was a brush away. The play was not memorable, but the evening was.

For a short while, Fowles wrote the text for a number of books which were really photographic essays. One of my favorites of these is one called Shipwreck. Featured throughout the book are historic photos of ships that crashed on the coasts of the Scilly Islands and West Cornwall. (Fowles was always dedicated to his home town of Lyme Regis.)

Here, I’m posting a few of the photos in the book because they are inordinately interesting to me, and I think you may also find them such. The text is by Fowles.

Seine

Ran ashore in Perran Bay (Perranporth), December 28th, 1900.

This beautiful ship was a French ‘bounty clipper’ – so called because

a government subsidy to French ship-owners allowed them to build

for elegance rather than more mundane qualities. The crew got off

in heavy seas. By dawn the next day she was dismasted and on her

beam-ends, and broke up on the next flood-tide. Two weeks later the

hulk of this celebrated barque was bought for only £42.

Mildred

Struck under Gurnard’s Head in thick fog at midnight, April 6th, 1912.

She was carrying slag from Newport to London. When she began to

pound broadside on, the captain and crew launched a boat and rowed

along the cliffs to St Ives. The Mildred, Cornish built and owned,

was launched in 1889.

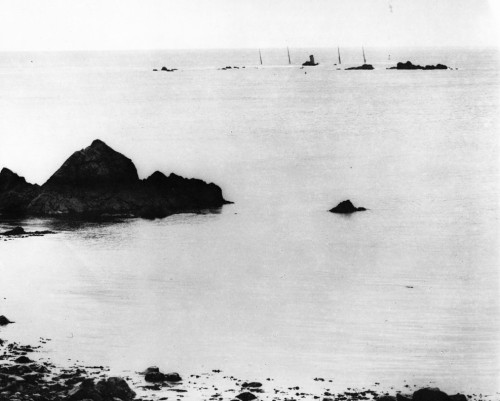

River Lune

Struck in fog and at night just south of Annet (Scillies), July 27th, 1879 –

the same day as the Maipu. The master later blamed a faulty

chronometer, since he had believed himself fifteen miles to the west.

The ship heeled and sunk aft in the first ten minutes. The crew took

to their boats, but returned in daylight to collect their belongings.

This barque was only eleven years old. She broke up soon afterwards.

Jeune Hortense

Stranded near St Michael’s Mount, May lyth, 1888. The foreground

carriage is for the Penzance lifeboat. This sturdy brigantine lived

to sail another day.

Mohegan

Struck the Manacles, October 14th, 1898. One of the most dreaded of all reefs,

the Manacles (from the Cornish ‘maen eglos’, rocks of the church, a reference

to the landmark of St Keverne’s tower) stand east of the Lizard promontory,

in a perfect position to catch shipping on the way into Falmouth — and before

Marconi ‘Falmouth for orders’ (as to final North European destination) was

the commonest of all instructions to masters abroad. But the Mohegan was

outward bound, and hers is one of the most mysterious of all Victorian sea-disasters.

She was a luxury liner on only her second voyage, from Tilbury to New York.

Somewhere off Plymouth a wrong course was given. A number of people on shore

realized the ship was sailing full speed (13 knots) for catastrophe; a coastguard

even fired a warning rocket, but it came too late. The great ship struck just as

the passengers were sitting down to dinner. She sank in less than ten minutes,

and 106 people were drowned, including the captain and every single deck officer,

so we shall never know how the extraordinary mistake, in good visibility, was made.

The captain’s body was washed up headless in Caernarvon Bay three months later.

Most of the dead were buried in a mass grave at St. Keverne.

Blue Jacket

Stuck fast – and surely a classic example of the expression-on the

Longships lighthouse rocks off Land’s End, December 9th, 1898. This

tramp was in ballast from Plymouth to Cardiff. The captain went below

to his cabin – and his wife – at 9.30 p.m., leaving the mate on watch.

He was woken near midnight by a tremendous crash, and came on deck

to find his listing ship brilliantly illuminated by the lighthouse only a few

yards away. Captain, wife and crew took to their boats and were picked

up by the Sennen lifeboat. How the mate managed to play moth to this

gigantic candle-the weather was poor, but provided at least two miles’

visibility-has remained a mystery. The Bluejacket sat perched in this

ludicrous position for over a year.

Hansy

Wrecked in Housel Bay near the Lizard Point, November 13th, 1911.

Sailing from Sweden to Melbourne with timber and pig-iron, she missed stays

while trying to come about in a gale. The crew were brought ashore by

breeches-buoy. Two days later a salvage party boarded – to find a pair of

goats lying happily in a seaman’s bunk. Local fishermen did a thriving trade

in timber for weeks afterwards; and the iron pigs are fished up for ballast

to this day. The Scottish-built Hansy (formerly Aberfoyle) had had an

unhappy history. In 1890 the bulk of the crew jumped ship in Australia,

after a bad voyage out – only to be returned on board following a fortnight

in jail. Jail must have been more agreeable, for eight men jumped ship again

at the next port of call. In 1896 a steamer found the Aberfoyle drifting helplessly

off Tasmania. The captain had been swept overboard, the first mate had

committed suicide by leaping into the sea and the rest had given up hope.

Similar stories of low morale – and often of insane bitterness between

officers and crew – are manifold.

Susan Elizabeth

Driven ashore at Porthminster Beach (St Ives), October 17th, 1907.

A gale blew this collier’s sails out off the Mumbles. Less than three months

later the Lizzie R. Wilce and the Mary Barrow also had to beach here.

Commentary &SpornFilms 16 Jan 2010 09:11 am

Notes

- Every couple of months HBO Family schedules a lot of my shows for a one day marathon. Today’s one of those days. Here’s the schedule for the films on that channel in case you’re channel surfing looking to fill a couple of minutes:

Saturday January 16th

LYLE LYLE CROCODILE

LYLE LYLE CROCODILE

2:00 PM HBO FAMILY – EAST

5:00 PM HBO FAMILY – WEST

THE STORY OF THE DANCING FROG

2:30 PM HBO FAMILY – EAST

5:30 PM HBO FAMILY – WEST

THE RED SHOES

3:00 PM HBO FAMILY – EAST

6:00 PM HBO FAMILY – WEST

EARTHDAY BIRTHDAY

3:30 PM HBO FAMILY – EAST

6:30 PM HBO FAMILY – WEST

MIKE MULLIGAN & HIS STEAMSHOVEL

MIKE MULLIGAN & HIS STEAMSHOVEL

4:00 PM HBO FAMILY – EAST

7:00 PM HBO FAMILY – WEST

THE MARZIPAN PIG

5:00 PM HBO FAMILY – EAST

8:00 PM HBO FAMILY – WEST

THE LITTLE MATCH GIRL

5:30 PM HBO FAMILY – EAST

5:30 PM HBO FAMILY – WEST

IRA SLEEPS OVER

6:30 PM HBO FAMILY – EAST

9:30 PM HBO FAMILY – WEST

Each month I update the full monthly schedule of the screening of my work over at my site www.michaelspornanimation.com

- Variety, this week, had a couple of articles about animation that were probably designed to catch the eye of Oscar voters, but gave me a bit of reading about 2D, Hollywood style.

Strong voices toon up was nominally about voices for animation, but in this case, particularly Keith David who did a couple of voices for animated features this year. He was the villain, Dr. Facilier, in The Princess and the Frog and the cat in Coraline.

Strong voices toon up was nominally about voices for animation, but in this case, particularly Keith David who did a couple of voices for animated features this year. He was the villain, Dr. Facilier, in The Princess and the Frog and the cat in Coraline.

Retro sequence sings in ‘Princess’ is a short piece about the well-designed “Moderne” song number (“Almost There”) from The Princess and the Frog. I rather liked this sequence and would have hoped for more from Variety on this piece (probably also promoting the song for the Oscar). During Friday Night’s Critics’ Choice Awards, this was the song that was singled out for attention. It might have been nice if Variety had named an animator or designer in the article.

This image was pulled from Chronicle Books’ The Art of The Princess and the Frog by Jeff Kurti. The four images are credited to visual development artist, Sue Nichols. I would have liked to have seen more about this sequence in this book, as well. A total of two pages go to the standout sequence. Short shrift.

There were also quite a few lines about animation in other articles in Variety that perked my ears. This one, for example, had me wondering about the WGA:

“This year’s eligible WGA titles include an animated film — Henry Selick’s adapted script for Coraline from Neil Gaiman’s book. Since the WGA doesn’t usually cover animation, those screenplays are usually ineligible.”

Why are screenplays ineligible? Is it because animation is considered inferior by the WGA relegating animation writers to the Screen Cartoonists’ Guild? Ratatouille received a WGA nomination, though it looks as though Brad Bird was not a WGA member at the time.

Meanwhile the Oscar rules for music contribution have gotten a bit arcane and bizarre. This week it was decided that Randy Newman’s score for The Princess and the Frog was ineligible to compete for an Academy Award for the Best Score. The rule states: “scores diluted by the use of tracked themes or other preexisting music,

diminished in impact by the predominant use of songs, or assembled from the music of more than one composer.”

In English, that means there are songs so they don’t want the musicals to compete for score, too. Apparently this idiotic rule came in when Alan Menken won a number of Best Songs and Best Scores in a row. The board put a stop to that!

Why isn’t there still an award for Best Song Score? This existed for many years and now it’s a no-no. Pretty foolish. Just like the automatic selection of 10 films for Best Picture so that some popular films won’t be left out. The problem is this year there aren’t 10 films that I can name which are worthy of an Oscar.

- There’s an excellent article in the NYTimes (actually one of many) by André Aciman celebrating the work and the intimacy of Eric Rohmer. I still am sad over this week’s enormous loss.

Bill Peckmann &Books &Comic Art &Illustration 15 Jan 2010 09:00 am

Walt Kelly Comics – 2

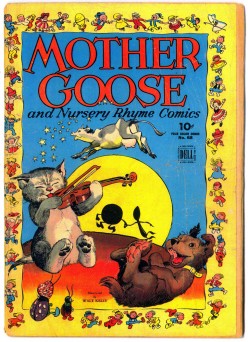

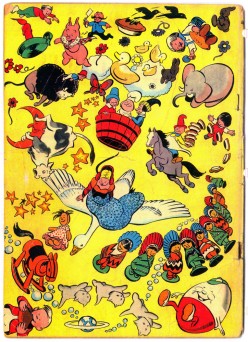

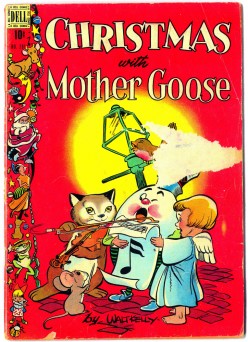

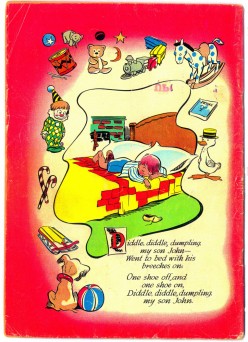

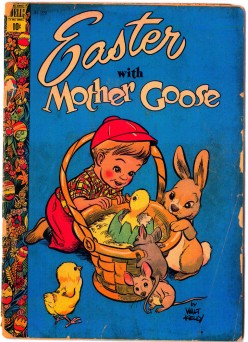

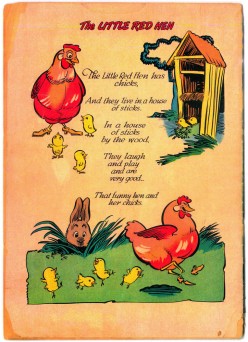

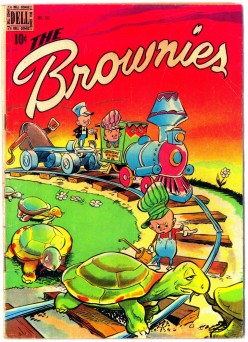

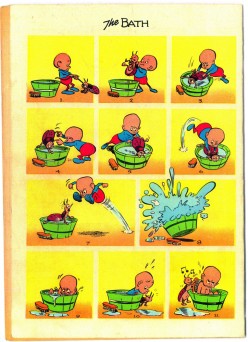

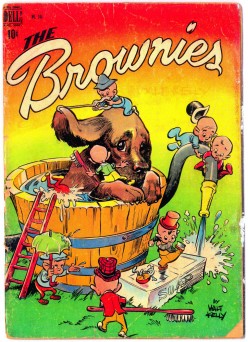

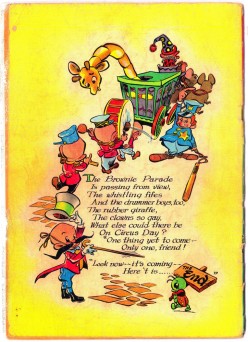

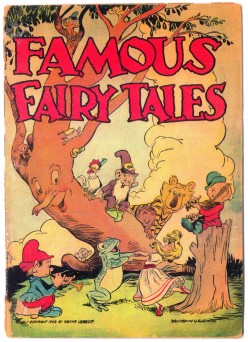

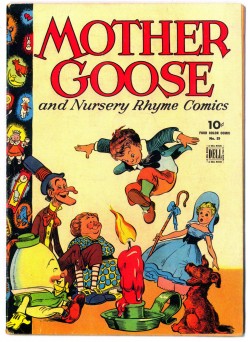

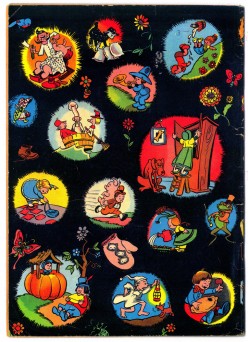

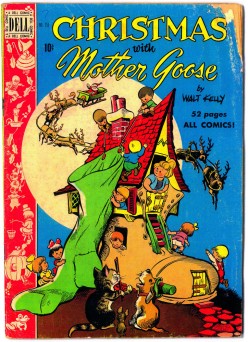

- Last week I posted the first part of this display of comic book covers (front and back) drawn by the inimitable Walt Kelly in his pre-Pogo days.

As he completed the series of Fairy Tale covers, he moved into Mother Goose and then The Brownies. There’s a charge I get looking at the brilliant draftsmanship on display here. The man could draw. We knew this from the quality of the art in Pogo, but these covers give us a different light in which to view this artist. It’s a great trip to waltz through the years 1942 – 1948 with Walt Kelly seeing the progression of his comic art.

As I mentioned last week, these covers were copied in the 1980′s by Bill Peckmann from the great collection of John Benson. Bill has loaned them to me, and I’m sharing.

1a

1a  1b

1b(Click any image to enlarge.)

2a

2a  2b

2b

Mother Goose develops after the Fairy Tale comics.

4

4

Mother Goose becomes a holiday item.

Animation &Animation Artifacts &Bill Peckmann &Disney &Models 14 Jan 2010 09:04 am

Little Whirlwind – 2

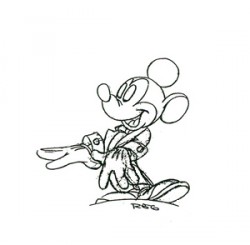

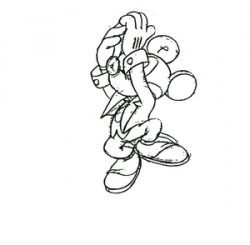

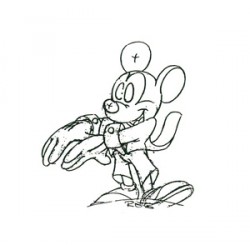

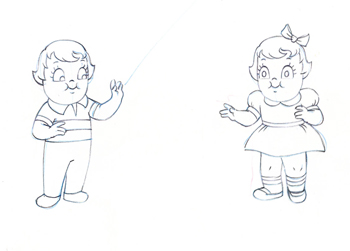

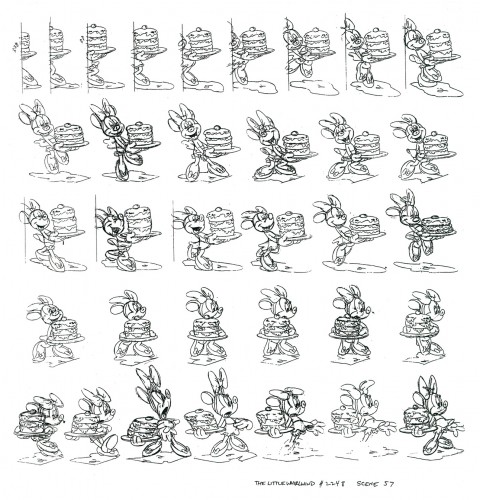

- A second model sheet of Minnie shows the animation breakdown for scene 57 from the film, The Little Whirlwind. The scene was animated by Ward Kimball and Reuben Timmins (effx).

Here’s the full model sheet. Note that some of the drawings are out of order (row 2 should be row 3.)

(Click any image to enlarge.)

Here’s a breakdown of those same drawings enlarged for viewing.

1

1 2

2

twos since I have nothing to go by, I just let it play itself. Click left side of the black bar to play.

Right side to watch single frame.

Thanks to Bill Peckmann for the generous loan of this model sheet.

Daily post 13 Jan 2010 06:19 pm

Acceptance Speeches

Thia was Wes Anderson’s acceptance speech at the National Board of Review:

At the NYFilm Critics Awards on Monday, George Clooney introduced Wes Anderson with an embarrassing speech, according to Variety.

Clooney said, “Before the show started Wes said, ‘George, tonight when I give my acceptance speech, I am going to blow the roof off this place. I’m going to give the best god-damn acceptance speech in New York Film Critics Circle history.’

I said, ‘You know, Wes, there are some people here that are good at this shit like Meryl Streep,’ and he said, ‘Fuck her. Fuck Meryl Streep!’ I mean who says that? Really, Wes!”

A visibly embarrassed Anderson then gave a brief acceptance speech, to which Meryl Streep gave him a standing ovation.

This was Anderson’s speech:

- “This movie took approximately the same amount of time as an undergraduate college education, and to me it also had a kind of university-like atmosphere,†he said. “More or less every person in the entire very large crew was a kind of scholar in their area — a very gifted, knowledgeable specialist. And all the various movements, they often resembled basement laboratories where experimental projects were being invented. I certainly was a student in this establishment, although an extremely old one compared to most of my professors.†He concluded by thanking the “think tank of artists and crafts people†who “educated me in stop-motion animation.â€

Articles on Animation &Independent Animation 13 Jan 2010 09:02 am

Canemaker meets Dunning – 1980

The Jan-Mar 1980 issue of Animafilm included this interview with George Dunning by John Canemaker. John was very taken by the Dunning film in progress, The Tempest, and he starts off his interview with questions about that film.

One has to live

George Dunning talks with John Canemaker

JOHN CANEMAKER: I saw a pencil test of “The Tempest” five years ago on CBS-TV. Are you still working on this film?

GEORGE DUNNING: I am indeed. More so, stronger on it than I was then. I’ve got a few hits and pieces in a rather unfinished state and some more going on now. It’s an attempt to he as personal as I can be. My approach is to do a few minutes to present to hackers. To justify doing Shakespeare as an animated film. Obviously live-action with stars and so on is a great advantage in box-office terms. People ask me why do it in animation. It’s all very well with the fantasy side of it, that seems appropriate. But beyond that, it’s something that I think should be demonstrated. And that’s what I’m doing, and then that helps open a technical line on it as well so that others can carry on.

J.C.: Will you be removing the words as you did with the poem you based “Damon the Mower” on?

G.D.: This is a difficult thing to make a statement about cause I’m in the middle of it. I might change my mind and do it all differently. But at this stage I find that I’m always taking out. I’ve taken a sequence of dialogue and cut it enormously -taken out half of it. Then I look at it and I take out more. I keep taking chunks away. I think this is legitimate but I am worried because it is tampering. But at the same time I think the verbal side of it, from a stage point of view, has a kind of function that on film is not necessary, if I could put it that way. I mean it sounds like I’m saying I know how to rewrite Shakespeare and I’m a bit timid about that. I just feel that in the end it is a film that one is making. I’m not rewriting Shakespeare, I’m making a film. In that sense it’s to use the dialogue but to pull a lot of it.

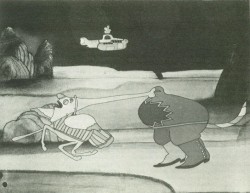

J.C.: The clip I saw showed a tree-like creature walking.

G.D.: That’s Caliban. He’s a tree through the whole thing. I just got carried away with that one phrase where he says, “This island is mine”. It just suddenly hit me, I saw this image of this tree, which is full of creatures as well. It’s sort of an ecology thing all together. And in the end of the play they leave and you have this island with Caliban left. And it’s sort of a hack-to-nature situation.

J.C.: Will you he mixing graphic techniques in the film?

G.D.: At this point it isn’t that far-out as far as technical things are concerned. I’ve been using ccl levels and Xerox drawings. It’s an attempt to keep things handle-able and in a condition where others can help. Cause if you get to do it in a technique which only one person can do it’s very limiting obviously.

(Click any image to enlarge.)

J.C.: Do you work out of a studio in London?

G.D.: Yes, our studio is TVC London. It’s based on the name TV Cartoons. Auspicious name! And we’re having our twenty- first birthday this year. In June we had it. It’s really a studio Dick Williams has had a lot to do with in the sense that he did a great deal to help in the early days to get it started. When I got to London he was working on “The Little Island”, and I helped him a little bit on that. Then he did a lot of commercials, a lot of stuff sort through our studio. I was sent over to London by Bosustow and UFA to set up a UFA satellite. They wanted to get some more footage for the “Gerald McBoing Show” on CBS. In those days Bosustow was on a big expansion drive and he sent Leo Salkin and me over to set that up. We set it up and seven months later UFA was practically bankrupt. This was ’56 or ’57.1 was in this position of going around to agencies cause we were doing commercials at that time and doing very well. Everyone was very glad that UFA was in London and so on. And Dick was doing commercials with us. So then I went around to all the agencies to say good-bye and they said, “Oh, stay. Can’t you keep this thing going? It’s marvelous”. So it was a matter of trying to make a set-up which I did with some businessmen. I had long talks with Dick, saying “What’ll I do…” And he said “I’ll help you and stick with it. This is great and you should stay on.” The prospect otherwise was

first birthday this year. In June we had it. It’s really a studio Dick Williams has had a lot to do with in the sense that he did a great deal to help in the early days to get it started. When I got to London he was working on “The Little Island”, and I helped him a little bit on that. Then he did a lot of commercials, a lot of stuff sort through our studio. I was sent over to London by Bosustow and UFA to set up a UFA satellite. They wanted to get some more footage for the “Gerald McBoing Show” on CBS. In those days Bosustow was on a big expansion drive and he sent Leo Salkin and me over to set that up. We set it up and seven months later UFA was practically bankrupt. This was ’56 or ’57.1 was in this position of going around to agencies cause we were doing commercials at that time and doing very well. Everyone was very glad that UFA was in London and so on. And Dick was doing commercials with us. So then I went around to all the agencies to say good-bye and they said, “Oh, stay. Can’t you keep this thing going? It’s marvelous”. So it was a matter of trying to make a set-up which I did with some businessmen. I had long talks with Dick, saying “What’ll I do…” And he said “I’ll help you and stick with it. This is great and you should stay on.” The prospect otherwise was

to go back to New York in tatters. It all seemed downhill. I remember Dick came to me exactly a year later and he said, “The year is up.” And I said, “What do you mean, the year is up?” He said, “I said I’ll help you, and give you a push. Now I really want to do stuff through my own company’s name and things like that.” We went on collaborating on some things but he was much more active with the Richard Williams Studio and developed it and so on. I have always had the greatest respect for all his abilities.

to go back to New York in tatters. It all seemed downhill. I remember Dick came to me exactly a year later and he said, “The year is up.” And I said, “What do you mean, the year is up?” He said, “I said I’ll help you, and give you a push. Now I really want to do stuff through my own company’s name and things like that.” We went on collaborating on some things but he was much more active with the Richard Williams Studio and developed it and so on. I have always had the greatest respect for all his abilities.

J.C.: So you set up your own company and were doing commercials?

G.D.: Lots of stuff like that and industrial films.

J.C.: Did you do features before the “Yellow Submarine”?

G.D.: No, we did a Saturday morning (TV) series

J.C.: Did you do features before the “Yellow Submarine”?

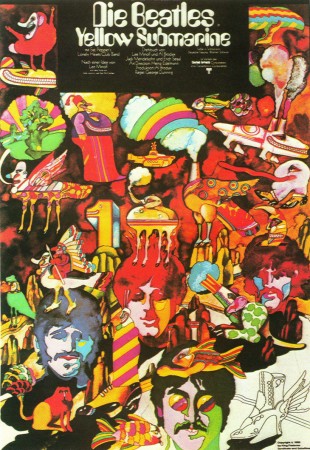

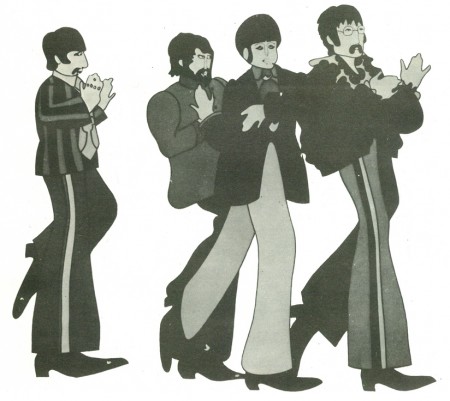

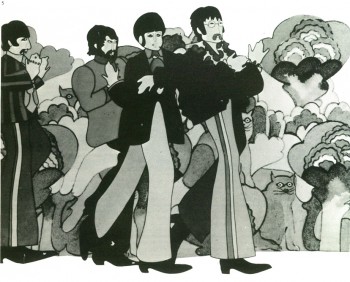

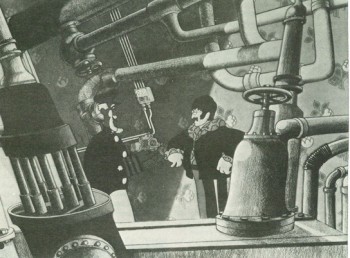

G.D.: No, we did a Saturday morning (TV) series for the Beatles music. King Features organized that with the Beatles and got permission to do cartoon versions of the four of them. It was terrifying. It was a very poor kind of design, but there it was. The show was very ordinary, very cheap cut-rate kind of thing. It was that kind of show with two numbers set into fifteen minutes framing it then another fifteen minutes to make the half hour. We made up a new half hour show one way or another each week, got to the lab then got that onto the plane, had the day off, then started in again, grinding on with this. It was King Features (newspaper syndicate) that had the idea to do a feature-length film and they kept hammering away to Brian Epstein (Beatles’ manager). He didn’t want to buy that for the longest time. Then finally agreed.

J.C.: Which would be around 1967?

G.D.: Yes. So that’s why our studio did the thing. As I said, the design of the characters in the TV show was hopeless, although King Features had no objection. They were completely without any point of view on the thing. It was sort of business. We were desperate and I was jumping around like mad because I knew that had to be really well solved or we were dead. I tried with different kinds of designs. We got a bit of track of the four boys talking after they’d left the pot open once on a recording. So we took this talk and animated to it and kept testing and trying different things. We saw and had admired Heinz Edelmann’s graphic designs in “Twin” magazine. And thought why don’t we even try him. So we got in touch with him, he flew over and we showed him what we were doing and he disappeared for two weeks. I remember this brown envelope arrived with four drawings in it, one of each Beatle. It was really marvelous cause it had that solved, attended-to quality. You could see it wasn’t Mickey Mouse, it wasn’t this, it wasn’t that – it was just there! The film is very much a phenomenon.

G.D.: Yes. So that’s why our studio did the thing. As I said, the design of the characters in the TV show was hopeless, although King Features had no objection. They were completely without any point of view on the thing. It was sort of business. We were desperate and I was jumping around like mad because I knew that had to be really well solved or we were dead. I tried with different kinds of designs. We got a bit of track of the four boys talking after they’d left the pot open once on a recording. So we took this talk and animated to it and kept testing and trying different things. We saw and had admired Heinz Edelmann’s graphic designs in “Twin” magazine. And thought why don’t we even try him. So we got in touch with him, he flew over and we showed him what we were doing and he disappeared for two weeks. I remember this brown envelope arrived with four drawings in it, one of each Beatle. It was really marvelous cause it had that solved, attended-to quality. You could see it wasn’t Mickey Mouse, it wasn’t this, it wasn’t that – it was just there! The film is very much a phenomenon.

J.C.: It’s a time capsule of the sixties.

G.D.: It is that. That’s the contribution of many people. The film would have had a life because of the Beatles music.

That’s a separate consideration. And the fact that Heinz solved that side of it was so great and that was marvelous.

We had a budget of a million dollars, and eleven months to do it. The Beatles took $ 200,000, off the budget. There were three animation directions on it: Jack Stokes, who learned his trade with a group of people – a whole generation of animators in London – from a Disney man who came over, David Hand (Director of “Snow White”). Eddie Radich was another animation director on “Submarine”; Bob Balser, who has been for a long time in Barcelona. He’s the third director.

We had a budget of a million dollars, and eleven months to do it. The Beatles took $ 200,000, off the budget. There were three animation directions on it: Jack Stokes, who learned his trade with a group of people – a whole generation of animators in London – from a Disney man who came over, David Hand (Director of “Snow White”). Eddie Radich was another animation director on “Submarine”; Bob Balser, who has been for a long time in Barcelona. He’s the third director.

There was a period of about five months where we had 200 people working together in out studio in Soho Square. My memory of that time is that it was amazingly unfrantic, in the sense of devoted and productive. Everybody was very grim, hardworking. The whole atmosphere was “We’ll show them” meaning the rest of the world “that we can do this in London.” This odd thing of making a feature.

J.C.: This was the first British feature since “Animal Farm”?

G.D.: Absolutely yes. The film made money left and right. But it didn’t for TVC and very nearly bust us. That’s a very long and very bitter story. We had a really nasty time of it. We went over the budget, not a large amount over. The producer people through King Features organized to take over the company. And we learned an awful lot. Very bitter situation. After it was all over it got smoothed down. We repaired our relationship with King Features. But the whole thing was very sour.

J.C.: You have retained your credentials as a film artist by making personal films. Is your work at TVC to help you to continue as an independent artist?

J.C.: You have retained your credentials as a film artist by making personal films. Is your work at TVC to help you to continue as an independent artist?

G.D.: I would guess that is the answer, yes. One has to live. I had a long stint at the Canadian Film Board. I learned a lot and enjoyed that kind of existence – government backing, budgets for films and all kinds of special facilities that you could get that way, that you don’t get out in the cold world of commerce.

J.C.: Who were some of the artistic influences in your career?

G.D.: McLaren. Alexeleff. Bartosch. Then there’s that whole world of Disney stuff that we’d all he poorer without, and I think in hits and pieces and in various ways it’s been an enormous influence.

J.C.: What is your age?

G.D.: 57

J.C.: Thank you very much for your time.

G.D.: Pleasure.

GEORGE DUNNING (1920-1979): FILMOGRAPHY

1943: J’AI TANT DANSE (I have danced so much), AUPRES DE MA BLONDE (By my blonde, Chants populates), 1944: GRIM PASTURES, 1945: THREE BLIND MICE, 1946: CADET ROUSSELIE, (UPRIGHT AND WRONG), 1947: THE ADVENTURES OF BARON MUNCHHAUSEN, FAMILY TREE (with Evelyn Lambard), 1959: THE WARDROBE, 1962: THE FLYING MAN, THE APPLE, 1968: CHARLEY, THE LADDER, THE YELLOW SUBMARINE, 1970: MOON ROCK, 1973: THE MAGGOT.

Publicity and sponsored films including: 1946: DISCOVERY – PENICILLIN, 1958: THE STORY OF THE MOTOR-CAR ENGINE, 1962: THE EVER-CHANGING MOTOR-CAR, 1962-65: THE ADVENTURES OF THUD AND BLUNDER (safety film for the Coal Board), 1966: BEATLES (TVseries with Jack Stokes), CANADA IS MY PIANO (with Bill Sewell).