Search ResultsFor "disney"

Animation &Books 09 Jul 2011 07:12 am

Tytla, Celestri, Anik and Eric Larsen

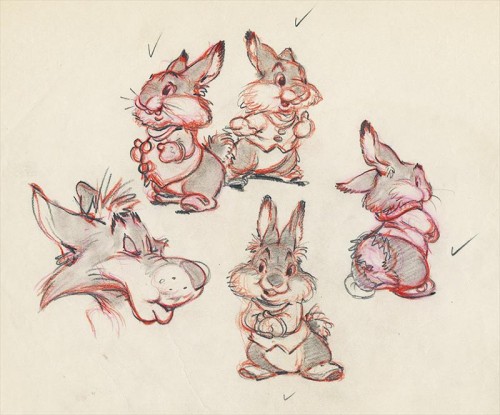

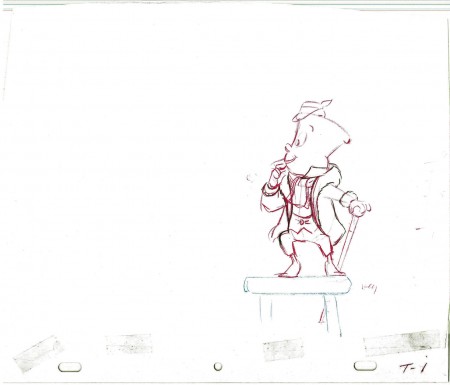

- Mark Sonntag just sent me a model sheet from The Hungry Wolf that he found on auction at Howard Lowery’s. There’s no way to tell if these drawings are by Tytla, but the drawing is beautiful just the same. The inclination to shade in the characters on this film is interesting, though. Many thanks to Mark for sharing.

______________________________

- I am such a fan of Bill Tytla‘s work, I can’t even begin to tell you how much. This week, on his blog, Andreas Deja posted some roughs by Tytla and I couldn’t believe how wonderful some of those drawings are.

- I am such a fan of Bill Tytla‘s work, I can’t even begin to tell you how much. This week, on his blog, Andreas Deja posted some roughs by Tytla and I couldn’t believe how wonderful some of those drawings are.

There’s a series of Grumpy posing in the middle of one of his negative rants, that just sends me. I’ve gone back to the blog at least a dozen times to look at those drawings again and again. The character starts by throwing all of his hostility out to whomever he’s talking to. Then he crosses his arms, with back to the listener. That immediately has him reach out to that person with his entire body, even though his arms stay crossed. It’s such a wonderful mix of emotions so beautifully and graphically presented. All the emotion within Grumpy is out on the floor; he thinks he has nothing to hide and is letting it all out. Thanks to Tytla, we see that Grumpy wants to be like all the others and love Snow White as well. He’s so conflicted and trying so hard not to be honest. This is a brilliant animator at the top of his game.

In the past, I’ve posted quite a few Tytla drawings – most of them loaned to me by John Canemaker. I think in the next week or two I’m going to pull out many of them for a recap. They’re just too great to sit hiding in the morgue of my blog. I want to take another look at them, and maybe share that, again, with you. I hope you’ll indulge my obsession.

- John Celestri is a very good animator who has been a fan of Tytla’s work since I first met him back in 1977 on Raggedy Ann & Andy. John was in the NY Assistant pool that I supervised, and he was a talent to reckon with. Now, John has a new blog that is starting to take shape. It’s like many animator/director blogs in that it’s built around his work in the industry, and there’s a lot of experience for him to draw on. After he left Raggedy Ann, John moved onto Tubby the TUba at NYIT, then Nelvana to work on Rock & Rule. From there he worked on many features in LA, some with Richard Rich‘s studio for Nest Animation. In every step forward, John’s animation kept getting stronger. Now he has his own studio in Kentucky.

- John Celestri is a very good animator who has been a fan of Tytla’s work since I first met him back in 1977 on Raggedy Ann & Andy. John was in the NY Assistant pool that I supervised, and he was a talent to reckon with. Now, John has a new blog that is starting to take shape. It’s like many animator/director blogs in that it’s built around his work in the industry, and there’s a lot of experience for him to draw on. After he left Raggedy Ann, John moved onto Tubby the TUba at NYIT, then Nelvana to work on Rock & Rule. From there he worked on many features in LA, some with Richard Rich‘s studio for Nest Animation. In every step forward, John’s animation kept getting stronger. Now he has his own studio in Kentucky.

The blog, at present, uses John’s own work to show basic animation techniques and script writing problems. It’s growing up into something quite interesting, and I suggest you check it out, if you haven’t already.

By the way, I love that John has pursued a completely non-animation, secondary path in his life. He has also authored quite a few mystery novels with his wife, Cathie. (Their joint site is called CathieJohn.)

- Also worth visiting is the studio site for Dancing Line Productions. This is the animation company of Anik Rosenblum, a Vancouver, Canada animator who brings a lot of grace and lyricism to the animation he’s been doing for some beautiful spots. There are many examples of his work on the site, and you should take a look at some of it.

Below is an animated piece called “The Autumnal Walk” which gives a good idea of Anik’s work.

The Autumnal Walk

This is one of my favorite pages of Dancing Line’s site. It answers the question, “Why hire us?” Anik has a good, sweet sense of humor. More power to him; I hope his company is successful.

- I just read an interview with Eric Larsen in Don Peri‘s book, Working with Walt. Something Eric said caught me and I thought it would be good to quote him:

- When I came into this business, Frank [Thomas] and Ollie [Johnston] and Marc Davis and Ward Kimball and John Lounsbery all came about the same time. Hal King and a few more came then, too. There was a group of us who developed, and Walt started putting a certain’ amount of responsibility on us in a way. But we came through what we called me unit system: each one of us came up through a very strong animator. These are the men I spoke of a little while ago when I said that here were such great talents and yet they opened up their arms to you to let you have everything they had: Ham Luske, Norm Ferguson, Bill Roberts, Wilfred Jackson, Ben Sharpsteen, Freddy Moore, and then just a little bit later Bill Tytla. Good gosh, what more could you ask for! We came up under those men, being taught, you might say, with them looking over our shoulders. A number of years ago, we dissolved the unit system. Don’t ask me why because I can’t answer. It’s the biggest mistake we made. Now we are trying to set up units again. Like on Bambi, I had ten animators plus all their assistants

working with me. I spent most of my time up here in this room and then would go down and animate at night. But you could keep control of certain things. You learn by working with somebody who has gone I tough the mill. But you’re always learning. There’s no such thing as I graduation in an animation class.

Basically, Eric Larsen is saying that only by our working together can we advance the art of Animation. That’s true. But I wonder if we do that anymore. I wonder if we’re open to each other to try to help out. I hope so. I hope all these new sites, such as John Celestri’s site, help to impart some tidbit of knowledge to someone coming up. It’d be great if it does.

Articles on Animation &Independent Animation &John Canemaker 07 Jul 2011 07:15 am

Caroline Leaf meets John Canemaker

The following is from the book, Storytelling in Animation, The Art of the Animated Image Vol 2. This is an anthology that was edited by John Canemaker which was published in conjunction with the Second Annual Walter Lantz Conference on Animation.

A Conversation with Caroline Leaf

This transcript has been abridged from the “Tribute to Caroline Leaf” that took place on June 11,1988 during The Second Annual Walter Lantz Conference on Animation.

JOHN CANEMAKER: When Caroline Leaf was beginning work on her masterful short film THE STREET, she told an interviewer, “I wanted to tell stories with my films, and I used animal legends and myths. Now I am working more on dramatic representation: dialogue, character and human problems. Perhaps dramatic expression is not ultimately the best form for animation, but still, I do not try to do what live-action can do better. The strongest influence on me is from literature rather than film. Kafka, Genet, lonesco, Beckett, have affected me most with the depths of their visions and world views and ways of breaking up time to tell a story.”

Caroline Leaf’s work is a wonderful synthesis of many of the storytelling techniques and animation methods discussed at this conference. She represents to me both the old and the new—the traditional and the experimental. Her use of direct, under the camera techniques and brilliant metamorphoses recall the pioneering works of James Stuart Blackton and Emile Cohl. Her perfect sense of timing and implementation of personality to individuate her characters echoes the balletic movements and emotional impact of the best of Disney. Within her films the imagery can be, at one moment, representational, and, in the transitions, non-objective abstraction. Caroline tells ancient folk tales as well as modern short stories. And she uses tools as primal as her hands to position paint on a smooth surface, or push sand grains into impressionistic symbols. She records her art with a modern invention, the movie camera, which allows her to bring inert designs and stories to life, a miracle never realized by artists until our century.

Caroline Leaf created her finest films at the National Film Board of Canada, a sympathetic but nonetheless corporate structure, in which she has managed to retain her individuality and personal signature. She is also a vital link in the list of women animators, designers and storytellers past and present who have made their way in a male-dominated field. From the simplest means she conjures a complex world of emotions, which is a talent found only in the work of the greatest artists. The transformation and alienation of a man turned into a loathsome cockroach; the variety of feelings triggered in family members by the imminent death of a loved one; the pathetic, ultimately self-destructive attempts of a lovesick owl to assimilate into a different culture; a small boy and assorted animals facing death in the form of an eerily omniscient wolf are some of the stories told with consummate skill in the films of Caroline Leaf. I’m so glad you’re here.

CAROLINE LEAF: I’m glad to be here.

CANEMAKER: I think that what’s extraordinary about seeing all your work together like this is to view your first film and to realize that it was all there—right at the very beginning. The good design, the sense of timing, and your whole bold approach to the medium is already there—your ideas about how to tell the story. That was your first film, wasn’t it?

LEAF: PETER AND THE WOLF (1969) is my first film. And I must say, I agree. I haven’t changed very much.

CANEMAKER: Grim Natwick always said that timing is the last thing an animator learns. It seems as if it was the first thing that you learned. Where did that come from? Were you trained in theatrics in any way?

LEAF: I’m not sure where it comes from. I think I make shapes and then try to keep them in balance. That’s my idea of how they move. I don’t know how to say where the timing comes from.

CANEMAKER: But you also know when to not make them move—you have a good sense about “holds.” When the cockroach was looking in the mirror, it went on and on, and you had the guts to keep it there without having it move at all.

LEAF: I’ve heard people talk about feeling the movement, and I know that I feel it. Sometimes I have to get up and act something out, or look in the mirror to see what it looks like when something happens. Working directly under the camera the way I do, there’s nothing between me and drawing the motion, and that helps with that. Intuitive expression of the movement, the timing. CANEMAKER: Let’s talk about story. In PETER AND THE WOLF, it’s very experimental. In many ways it is a first film because you get a feeling you’re trying to do a lot of different things. How did you approach the story in PETER AND THE WOLF? There’s just barely a theme of Prokofiev in the beginning —it’s all there, yet it isn’t.

LEAF: I’ve read a lot, and I’ve been most influenced by stories that I have some good gut feeling about. But then I like to go off and do my own thing with them. And on that film in particular—you’re right, I was trying to experiment; and the way I was working, I just had to divide things into segments. The ideas would evolve out of a little pile of sand and then go into wh’ite, and then a few days later I’d start a new sequence. So, it was pretty much the situation of wanting to use a story while not following it precisely.

CANEMAKER: And you use touches of personality, too: the little goose steps down but has a very particular way of doing it and it got a couple of laughs each time because it was so goose-like. Your characters have a lot of personality. Do you feel that personality guides story?

LEAF: Can they be equal?

CANEMAKER: Whatever you want! Anything you want, Caroline!

LEAF: I would say the story is important to me because it sets the limits and anything I do I don’t want to deviate from the feeling I want to generate from the story. The characters are the vehicles that express the stories, so they have to be right for each other. And I don’t indulge the characters, I don’t think, because I would get off track with my story, so I think I always sustain a line to keep the story moving along.

THE STREET (1976), adapted from Mordecai Richler’s story

CANEMAKER: Let’s talk about THE STREET (1976). How detailed was the original short story? Why did you approach it?

LEAF: I just liked the story, but there I had Mordecai Richler, a living person, a writer who lived not too far away from me, and I wanted to respect his writing. His story was maybe twenty pages, and at first I thought that to be respectful to the writer I should put everything onto film. And I found as I was working, the more I could pare away the words and just work with the imagery and be true to the feeling I was getting in the story, the better it worked on film. So there I was really trying to follow his story, but because film is a different medium, it came out in a different form.

CANEMAKER: Did you ever show it to him or did you confer with him during the making of it at all?

LEAF: No, he was strangely disinterested. He didn’t like the story too much, and didn’t care what I did with it, and never got in contact with me about it. I didn’t discuss it with him.

CANEMAKER: Did he ever see the finished film?

LEAF: I sent him a print and he never answered. I don’t know what he thinks of it.

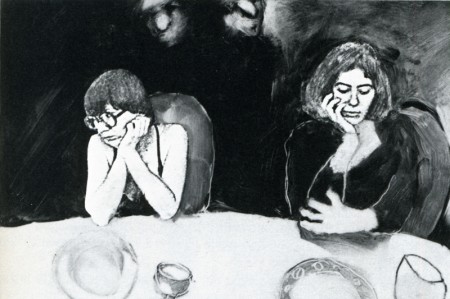

A family beset in THE METAMORPHOSIS OF MR. SAMSA (1977)

CANEMAKER: What about Kafka? Was your approach to pare away and get the imagery first in THE METAMORPHOSIS OF MR. SAMSA (1977)?

LEAF: The Kafka story is so complicated and wonderful. There I took just the element of what I was thinking about most—how horrible it would be to have a body, or the external part of one’s self that’s seen by the world be different from what’s inside one’s self, and not be able to communicate that. Since I’m a storyteller, I just worked with that one aspect of Kafka, so it’s quite different from his original story.

CANEMAKER: You really get into your characters; the emotion is there, it’s really extraordinary, I think. It’s just great. (Audience applauds.) Caroline doesn’t like to be interviewed, but she’s consented to this, and I appreciate it. I’d like to talk about the animated projects you’re working on now. One of them is a scratch-on-film technique.

LEAF: I’m just in the midst of starting two projects, and because I’ve been involved with live-action filming for a few years, and writing for live-action, now I’ve got a story that has all the characteristics and psychology and emotion of a live-action film, but I’m doing the images scratching on film. It is quite a restricted and crude image that I can make, but I find it exciting to find what I can tell of the story in imagery and how much I’ll have to rely on words.

Autobiographical insight in INTERVIEW (1979), co-directed with Veronica Soul

And the other project is a test of a computer animation program. It’s a small project, a program called Pastel, that was developed by the Film Board. They wanted to see how an animator would work with it, and what modifications it still needs.

CANEMAKER: Exciting. So you haven’t abandoned animation.

LEAF: No. Not at all. I just have had a hard time sitting still and doing it.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: I noticed in INTERVIEW (1979) that you had all those little thumbnails to the left [of the work under the camera]. Is that how you work, really planning it out in little sketches like that?

LEAF: Yes, that would be my detailed storyboard as I go along. I don’t storyboard too closely; to have done all the fun work, and to animate it, there are no surprises left. But I also need to know where I’m going since I work under the camera. If I take a wrong turn I can’fgo back. So, as I come to each scene, I do some little sketches, particularly to know what the characters look like in different positions, so I don’t get lost.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Your soundtracks have a powerful impact on the film. How much do you get involved? Do you sound-mix, or do you direct the actors and the dialogue?

LEAF: I am very involved with my soundtracks, and I enjoy working on them very much. The soundtrack for THE OWL WHO MARRIED A GOOSE (1974) was the first one I really conceived and executed. But when I’m working at the Film Board, I’m not the mixer, and I’m not the recorder, usually. There’s a crew of people that do that for me.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: You’re able to tell a story mostly through images, yet in THE METAMORPHOSIS OF MR. SAMSA and THE OWL WHO MARRIED A GOOSE you alter the language. Why did you make those choices?

LEAF: The Kafka story wasn’t in the public domain and I didn’t have the rights to the translation, so I made up a kind of gobbledy-gook language for that. And the Eskimo film was not a language you understood, either. They were speaking the Eskimo language.

CANEMAKER: THE OWL WHO MARRIED A GOOSE is exquisite. Sometimes in animation there are images you want to continue on and on and on. That scene of the birds flying, and the sound of wings getting as big and close as they are, and then they’re flapping for a while in front of you. I could watch it for a long time.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: In that vein, I’d like to know how long you studied the animals to get their movements so perfect.

LEAF: I don’t study animals. I don’t go to the zoo. And in fact my movement isn’t very realistic. I think you can make it convincing. It fits the shapes, I think. I’ve never really looked to see how birds fly, and it’s kind of awkward in fact how they do, but it somehow works.

CANEMAKER: In several films you have a character who will take a step and then the legs would switch in some unnatural way—but somehow it works. In THE OWL WHO MARRIED A GOOSE I think there’s a section where that happens.

LEAF: I know it happens in THE STREET once — arms change . . .

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Why are you working in Canada? Economics?

LEAF: Yes, the Film Board is quite a special place. It’s allowed me to do the films that I’ve done, which I don’t think I could have done down here.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Because no one’s going to buy them? Or distribute them?

LEAF: It’s because of the problem with the distribution of short films. Ask any of the independent animators who’ve spoken here. Most of them are teaching, and it’s hard to have films seen. I found it is also hard at the Film Board. It’s difficult to have short films seen, and I’m not happy with the distribution, but I’m paid a salary there, and I’m quite free. Not totally free, because it’s a government film agency, and there are restrictions.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: What kind of restrictions?

LEAF: I find there’s a rather insidious way of thinking that grows on one working in a place like that. The most obvious thing is that it’s not possible to experiment; or it’s not easy to do an abstract film, because they’re always concerned about their market, which is an educational market. And besides that they’re very sensitive to not provoke any public outrage, or outcry, so they take a middle road. Nothing should be too controversial. I can read stories and know right away, this is something that could be done at the Film Board or not. One isn’t free to do exactly what one would like to do but one can mold it to be close enough to be satisfying.

Exquisite images of geese in flight in THE OWL WHO MARRIED A GOOSE (1974)

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Does the Film Board expect to make their money back on films?

LEAF: No. The income they receive from the films goes back into production, but the Board receives government money each year. They have an annual amount given to them from Parliament. It’s voted each year.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Has it been growing?

LEAF: It’s been shrinking in recent years. So the place has shrunk a lot. Just last year they were voted an increase, which might just bring them equal with inflation for the first time in a few years. But everyone takes it as a vote of confidence.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Who owns the films you made while you were on salary?

LEAF: The Film Board owns them. I don’t have any rights to them at all.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Do you think that your technique would be used in any major projects, for instance in a Disney feature?

LEAF: Well, I’ve seen my way of transforming used in eel animation. But actually the way I work, under the camera, I don’t think I can work as a team in that way. So it would be hard to make a long film using my technique, and get everyone working in a way that looks the same, This winter I did a commercial in New York, arid that was the first time I’d really found that my under the camera technique could work commercially. Because normally I would do some designs and then I would start, and I’d go to the end. And here I didn’t have any way to fit into the system of checks and balances that are used commercially. The client couldn’t see beforehand what I was going to do. But I evolved enough different systems of storyboarding that they felt reasonably secure, when I started animating, what they’d get when I’d

finished.

CANEMAKER: If it were possible to direct other people in your technique, would you be interested in doing a feature?

LEAF: No, I wouldn’t. I can’t imagine directing other people, and also I have a lot of fun when my fingers are doing it and I discover for myself little things. That’s what keeps me going. And I don’t know what it would be like, if it would be enjoyable to direct other people.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Have you ever used colored sand?

LEAF: I got tangled in knots one time trying to use colored sand. When you use colored sand—colored anything—you put a lot of time into keeping your colors separate, so they don’t all become like mud. And keeping colored sand grains separate was very difficult! I gave it up quickly.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Have you had students or apprentices pick up on your technique and pursue it in their own pictures?

LEAF: There are a few people that have worked in the same materials that I’ve worked in, but not as many as I’d like. And I haven’t had students. I haven’t taught.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Will you be working on a team for the computer animation?

LEAF: This is just a small project, and I’m alone with the guy that developed the program. We’re working together. He listens to my complaints and makes alterations. I’m amazed sometimes by what he’s done, but it’s not really a team.

CANEMAKER: I would like to thank Caroline Leaf for being here.

LEAF: Thank you for being here!

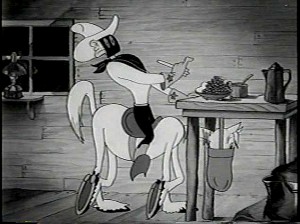

Animation &Animation Artifacts &Tytla 05 Jul 2011 11:28 pm

Tytla’s Hungry Wolf

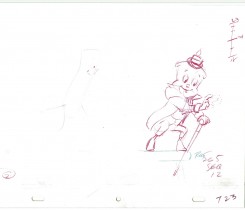

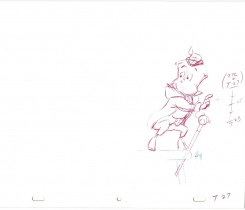

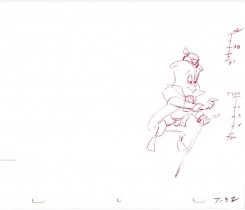

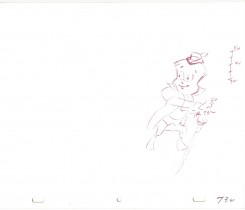

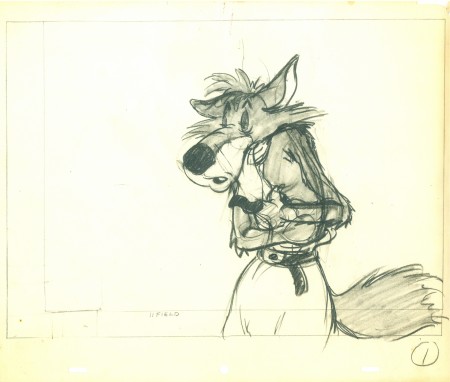

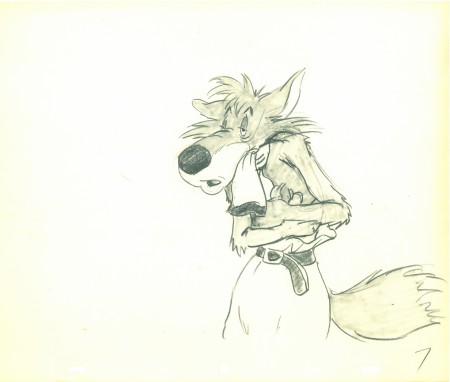

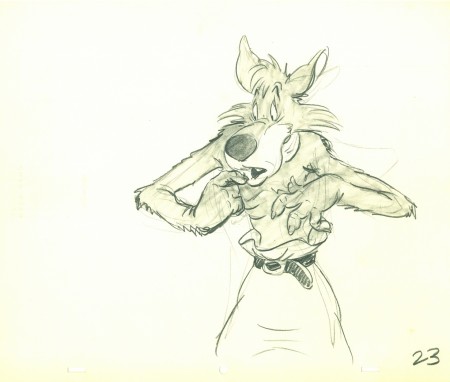

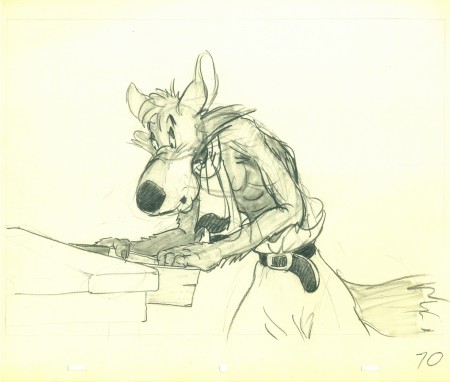

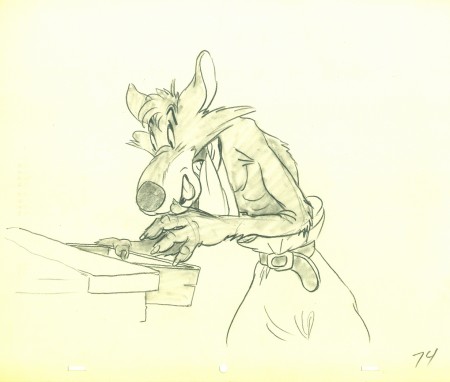

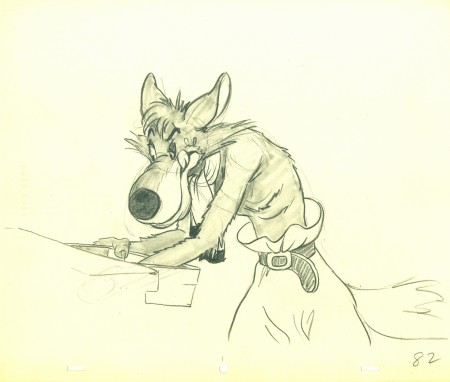

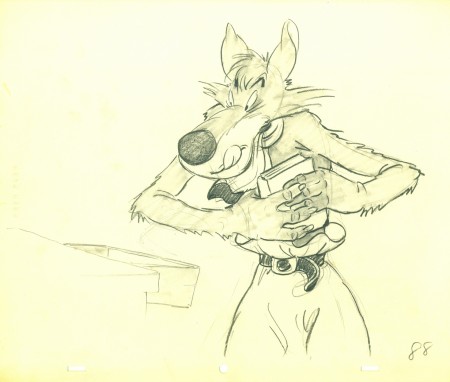

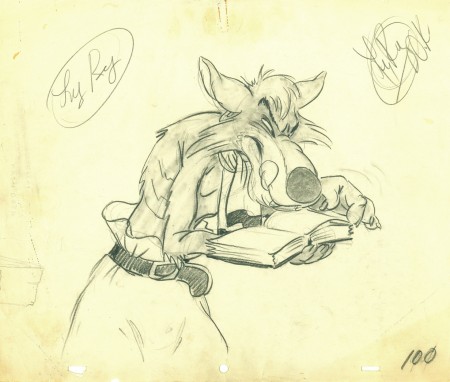

- Well, John Canemaker visited with a surprise. He brought a Bill Tytla scene. But this wasn’t Disney or Terry or Paramount. It was from a Hugh Harman film, The Hungry Wolf, made in 1940 at MGM. Not a very good film, the drawings are signed by Tytla, but they have no ladder indication for an Asst. to do the inbetweens. And most oddly, the wolves are shaded in by Tytla. Also take note of the table being animated into place. Are these animation drawings? Is it LO posing for someone else? And biggest of all, what is Tytla doing at MGM?

- Well, John Canemaker visited with a surprise. He brought a Bill Tytla scene. But this wasn’t Disney or Terry or Paramount. It was from a Hugh Harman film, The Hungry Wolf, made in 1940 at MGM. Not a very good film, the drawings are signed by Tytla, but they have no ladder indication for an Asst. to do the inbetweens. And most oddly, the wolves are shaded in by Tytla. Also take note of the table being animated into place. Are these animation drawings? Is it LO posing for someone else? And biggest of all, what is Tytla doing at MGM?

Since this would have been completed in early 1942, I can only assume that it was during the strike at Disney that Tytla did some work for Harman in mid 1941. Perhaps he came on as an animation director under Harman, who got credit for directing.

Here are all the drawings.

1

________________________

1

________________________.

The following is a QT of the entire scene with all the drawings included.

Since I didn’t have exposure sheets, I calculated everything on ones

(which seems to reflect the timing in the final film) and left however many

Many thanks to John Canemaker for the loan of the drawings. It was great just touching them.

Commentary 02 Jul 2011 07:53 am

More Odds & Ends

- A week or so ago Jeff Scher had a new film tha was posted on The NYTimes website. ‘You Might Remember This’ is a piece which focuses on Jeff’s son, Buster. Jeff writes:

While these films portray childhood, the perspective is parental. If Buster had made this film it would be all baseball, and the actual point of view, looking up at grownups twice his size, would surely feature more chins and nostrils. The angle might seem a small thing, but it can alter the feeling in subtle ways. Looking at children, our perspective is angled down and as they look up, we see eyes, those big ones, looking up like lasers. And, like every portrait, these films are double portraits, simultaneously reflecting the sensibility of who made them as well as who they picture.

While these films portray childhood, the perspective is parental. If Buster had made this film it would be all baseball, and the actual point of view, looking up at grownups twice his size, would surely feature more chins and nostrils. The angle might seem a small thing, but it can alter the feeling in subtle ways. Looking at children, our perspective is angled down and as they look up, we see eyes, those big ones, looking up like lasers. And, like every portrait, these films are double portraits, simultaneously reflecting the sensibility of who made them as well as who they picture. It’s a beautiful piece and well worth viewing. Like many of Jeff’s films, there’s a great score by Shay Lynch. (It’s worth visiting his website, too. He’s writing the score to Paul Fierlinger‘s next feature, Slocum.)

– Remember when Toy Story 3 came out, and the word from Pixar was that this was the last of the series? Now we learn that Tom Hanks has said the Toy Story 4 is in the works. (Will that come before or after Cars 3?)

– Remember when Toy Story 3 came out, and the word from Pixar was that this was the last of the series? Now we learn that Tom Hanks has said the Toy Story 4 is in the works. (Will that come before or after Cars 3?)

Hopefully, the future feature won’t be anything like the horrible little short that’s currently attached to Cars 2 in theaters. That short in combination with the companion feature, for an awfully tedious outing. I guess it’s too hard to pass up the billion dollars they made on the last Toy Story film; and who can blame them. It also received an Oscar and four nominations. Now they have a financial success with Cars 2, and you know the franchise won’t end there. (One wonders after the abysmal critical failure of this recent movie, will Lasseter continue writing and directing the upcoming film, himself?) Let’s hope that Oscar doesn’t fawn over Pixar with this terrible movie as they did with TS3.

Pixar is getting to smell like the Dreamworks of Shrek 4 fame. Anything for a buck – or is it a billion bucks for these things.

- One more thing I’ve been wondering about Cars 2. John Lasseter not only gets credit for directing (Brad Lewis gets credit as “co-Director”), but he also takes credit for the story along with Brad Lewis & Dan Fogelman. Ben Queen is credited for the screenplay.

- One more thing I’ve been wondering about Cars 2. John Lasseter not only gets credit for directing (Brad Lewis gets credit as “co-Director”), but he also takes credit for the story along with Brad Lewis & Dan Fogelman. Ben Queen is credited for the screenplay.

Now where does the storyboard fall into this schema? How do they work it? Do they write the “Story” first, then do a board changing things and then they write a screenplay from the board? Do they develop the story by doing a storyboard and then the script writer comes in to put down the dialogue? I’m curious as to how Pixar works. How does John Lasseter run Pixar, run Disney and then sit with board artists to construct a convoluted script like Cars 2? I honestly do not know. It sounds like a lot of hard work!

- Bill Benzon has an interesting piece on his blog New Savannah. In it he shows the connection between the 1945 Warner Brother’s cartoon, Book Revue, and the more recent feature-length film, The Secret of Kells (2009).

A site I hadn’t added to my Blog Roll until recently is Alltop. This lists the last five posts of a number of animation and drawing sites. It’s handy to see a large group of sites in a quick viewing to see if there’s anything you’ve missed. I also like seeing my site there on a regular basis.

- Grayson Ponti has a blog that is built around the 50 Most Influential Animators in Disney History. There’s a large number of people and their histories to wade through for Mr. Ponti, and it makes for a different kind of blog.

- Grayson Ponti has a blog that is built around the 50 Most Influential Animators in Disney History. There’s a large number of people and their histories to wade through for Mr. Ponti, and it makes for a different kind of blog.

I like that he not only looks at animators of the past but those of the present, as well. I don’t know many from the present and I should, so reading this blog acts like a wonderful crib sheet for me.

However, I wonder if these are the “most influential animators in Disney history” or just the lesser known. Although Mr. Ponti says that he, admittedly, has a hard time just selecting 50, I assume he’s gone over his quota. In a recent post, he does call Hugh Fraser, Don Lusk, Hicks Lokey and others “Honorable Mentions”.

Regardless, this is a fascinating blog and you should check it out. There’s plenty o’ reading here.

Note: The TAG Blog wrote about this last week. Mr. Ponti contacted me a week ago, but the link he sent me didn’t work, and it’s taken me ’til now to be able to get there.

I’m glad I did.

Disney &Frame Grabs 27 Jun 2011 06:28 am

More Pinocchio Multiplane

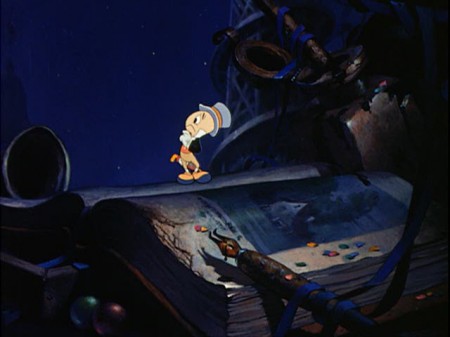

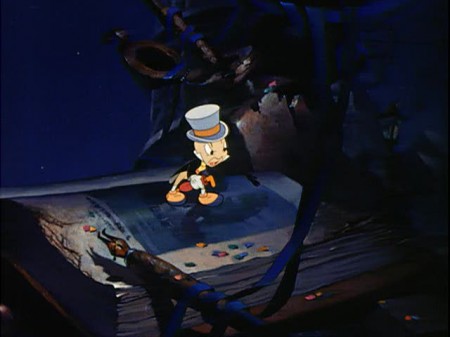

- I had such a good time last week posting images of scenes from Pinocchio using the multiplane camera that I decided to go back to the well. There are a lot of very small shots in that film that use the camera for a more limited but very effective purpose.

1

1A vaguely seen wagon rolls across the screen in a heavy rain storm.

2

2

The camera pans across the screen with the wagon.

3

3

Camera trucks in to the water spout.

4

4

Jiminy sits on the water spout in the rain.

cut

5

5

The wagon sits at rest in the rain

cut

7

7

Gepetto in the far distance, in the rain, walks toward the camera.

8

8

Lightning lights up the background.

9

9

Barely seen Gepetto moves forward calling for “Pinocchio!”

10

10

Gepetto slowly moves forward

11

11

He continues on in the rain.

12

12

He hears the wagon approaching screen left.

13

13

The wagon moves in front of him (slightly out of focus).

14

14

The wagon blocks across Gepetto who watches it.

At one point when I worked at the Hubley studio, John and Tissa David had a laughing disagreement. She had animated something with a couple of overlays panning over the background trying to create some sense of dimension.

John told Tissa that she was moving the overlays too quickly; they would look as though they were moving of their own accord, not that it would look like dimension as the camera moved in. She was adamant that she was doing it correctly. John told her that he had received a phone call from an historian in Europe. The guy had told John that he admired the way he used the multiplane camera on the carriage ride to Pleasure Island. The historian felt it was the best use of the multiplane, ever. John told Tissa that he had proof, then, that he knew what he was talking about. Tissa laughing, agreed to change her panning overlays.

I thought it’d be a good point to look at the multiplane use throughout this entire sequence.

18

18We start with the carriage moving quickly through some wooded overlays.

19

19

It’s definitely the multiplane. There’re levels of focus

and a very smooth movement to the panning trees.

21

21

The overlays move quickly past.

23

23

The overlay trees seem to have a slight highlight on the left side.

Could it be a cut line of a piece of paper picking up a light streak?

cut

25

25

No multiplane as we see Coachman, Pinocchio and Lampwick in the driver’s seat.

26

26

Jiminy with dust galore under the coach carriage.

27

27

Cut in for a tighter, beautiful shot of Jiminy talking to the audience.

28

28

Back to the carriage moving quickly behind multiplane levels.

29

29

. . . it passes trees . . .

30

30

. . . and moves to a stone bridge . . .

32

32

It comes to a pier and stops.

33

33

A steamship then takes them across the body of water.

No multiplane but quiet and beautiful water effects.

34

34

Dissolve to a beautiful shot of the steamship crossing.

No multiplane.

36

36

It finally stops at Pleasure Island.

No multiplane.

37

37

Pan with kids in front of coachman.

38

38

Across the screen as we open up . . .

39

39

. . . to see Pleasure Island.

43

43

Late night. Destruction and desolation.

44

44

A small pan across to the cowboy.

Very quiet use of the multiplane.

45

45

Notice the out of focus wheel in the left foreground.

47

47

Jiminy climbs up from behind the hill and looks back calling for Pinocchio.

51

51

. . . going out of focus as we rack focus to the 8 ball in the Bg.

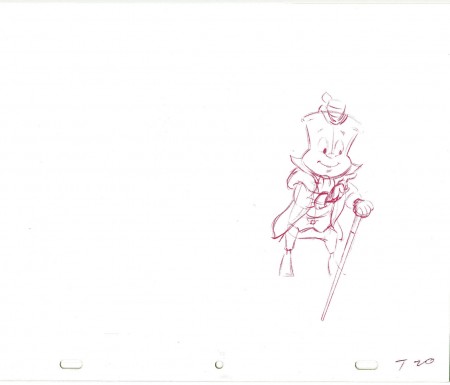

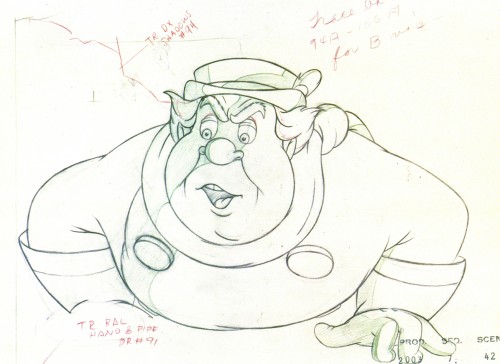

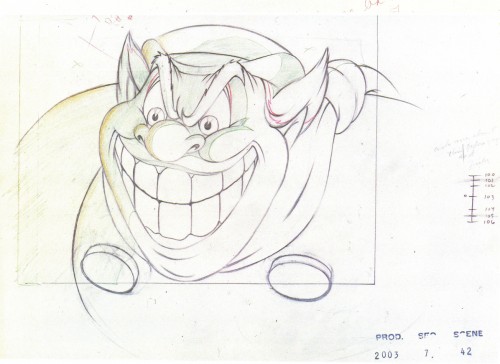

Here are a couple of drawings by Charles (Nick) Nichols done as part of the animation of the Coachman. The drawings come from the Canemaker book, Treasures of Disney Animation Art.

1

1

Action Analysis &Animation Artifacts &Articles on Animation &Disney 23 Jun 2011 06:56 am

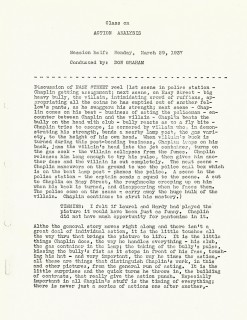

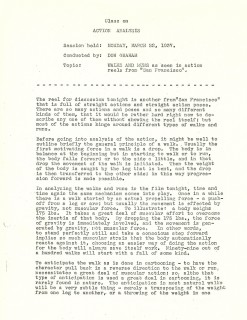

Action Analysis – March 29, 1937

- I continue, today, with the Action Analysis notes from the lectures given at the Disney studio by instructor, Don Graham. The lectures were often built around film sequences that were screened. In this lecture, they screened a sequence from Charlie Chaplin’s Easy Street as well as an in-house loop of a man walking with two children.

The animation personnel who attended and participated on this lecture included: Reuben Timmins, Izzy Klein, Jacques Roberts, Bernie Wolfe, Chuck Couch, Jack Hannah, Amby Paliwoda, Bill Tytla, and Bruce Bushman.

Cover

If you enjoy reading these Action Analysis notes, there are a wealth of them on Hans Perk‘s wonderful resource of a site, A Film LA. Many of them from earlier periods than these that I’m posting.

Animation &Disney &Frame Grabs &Layout & Design 20 Jun 2011 06:56 am

Pinocchio – Multiplane

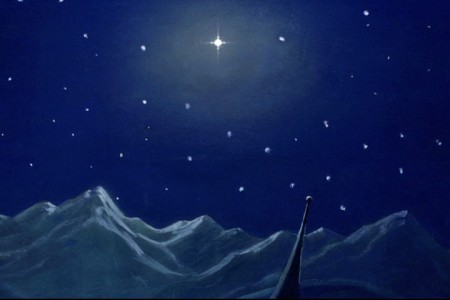

- In highlighting the use of the multiplane camera in Disney’s animated films, the pinnacle has to be Pinocchio. Two specific scenes jump out in any mention of the multiplane camera: the move in to Gepetto’s workshop and the awakening of the village.

So let’s get right into it:

Sequence director: Ham Luske

Layout by Hugh Hennesy

Animated by “Music Room 2″

1

1Start in the sky with the wishing star that will play

a large part in the film in a couple of moments.

2

2

Circle down from the sky field to an overhead of the village.

3

3

Continue moving down over the rooftops.

5

5

We first see Gepetto’s workshop from a distance.

6

6

There’s a matching cut and we continue to move in.

7

7

The POV of the camera is through Jiminy’s eyes.

8

8

When he moves in, it’s in hops.

10

10

Leaps and bounds as he (through our camera’s eye) gets closer.

12

12

The warm window into the workshop begins to fill the screen.

15

15

. . . looking into the workshop through the window.

16

16

Cut to an interior shot – the interior side of the window.

Jiminy Crickey, with hands and face up to the glass.

Then we move onto a miracle of a shot that would be hard even for computer users. Today, we wouldn’t anchor the feet properly on all those kids walking and running about. It’s an amazing piece of animation history.

The sequence director was Wilfred (“Jaxon”) Jackson.

Layout by Thorington C. “Thor” Putnam.

The animators involved in this scene include: John McManus, Jack Campbell, Cornett Wood, John Reed, Art Babbitt, Milt Kahl, Don Lusk, and Sandy Strother.

1

1The camera starts at the bell tower over the sleeping village.

2

2

Doves fly out as the bell starts to chime.

3

3

The birds fly out of focus as they move forward.

4

4

This allows the camera to start the big move

with the birds covering the tower.

6

6

The camera pushes in to cross the

little footbridge to enter the town.

7

7

The last bird leaves us, and . . .

8

8

. . . we’re into the village.

10

10

We move in toward the cross section of the town . . .

11

11

. . . as people start to come out of their houses.

12

12

The camera moves to the right.

13

13

We move toward a woman with geese as the

camera goes under an overpass.

15

15

We head a few steps down as more

chldren come out running to school.

17

17

The camera continues to the right

seemingly led there by one running boy.

19

19

. . . reaching Gepetto’s house.

20

20

The camera moves in on the house.

21

21

At this time we cut in and the big-time animators take over.

Milt Kahl handles Pinocchio, Art Babbitt does Gepetto, Don Lusk animates Figaro.

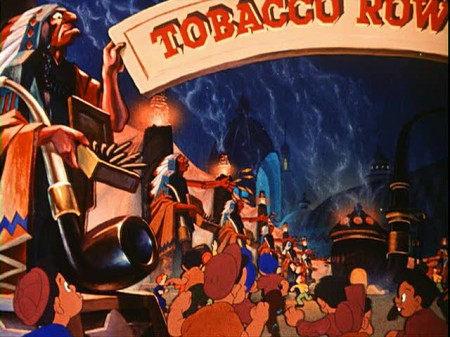

Although there are numerous beautiful scenes from Pinocchio that employ the multiplane camera, there’s one last sequence I’d like to concentrate on. This is where J. Worthington Foulfellow (“Fox”) and Gideon the cat cajole Pinocchio into following them so that they can sell him to the puppetmaster, Stromboli. This is a particularly interesting scene for the multiplane camera.

The sequence director was T. Hee.

Layout by Ken O’Connor.

The animators involved in this scene include: Ugo D’Orsi, Jack Campbell, Hugh Fraser, Charles Nichols, Marvin Woodward, Preston Blair, Milt Kahl and Charles Otterstrom and

Phil Duncan.

1

1The multiplane camera scene is several away from this,

but I feel as though this scene really sets up the big one.

2

2

We properly meet the fox and cat as they walk through the town.

3

3

They are well into conversation.

5

5

The fox picks up a cigar stub, telling us about their financial state.

7

7

Several short scenes later, they run into Pinocchio and

coax him away from school to follow them to the theater.

9

9

This cuts into the overhead multiplane shot.

11

11

We watch from overhead with trees and ornaments

marginally blocking our vision of the characters.

13

13

They turn a corner and the camera follows them.

17

17

A quick circling of the tree.

19

19

They do it again, but . . .

20

20

. . . Gideon the cat continues forward moving off screen.

21

21

The fox and Pinocchio continue on the path.

23

23

. . . catching up with them.

24

24

We view them through a tree and the side of a building.

25

25

They go up several steps, but the camera stops.

28

28

. . . the next scene, Jiminy Cricket is running. He’s late trying

to catch up to Pinocchio, thinking he’s on the way to school.

29

29

Jiminy is animated here by Phil Duncan.

David Nethery correctly points out in the comment section,

that Milt Kahl animated this scene.

Commentary &Disney 18 Jun 2011 07:34 am

Sight Seeing

- This past week Jonna commented on this blog: I can only imagine how it would have been to see one of the classics at a theater (I was born in the 90’s). It would have been great fun if any of you told about a premiere or screening that you’ve attended (e.g. the first time you saw Sleeping Beauty or something).

So I thought of a couple of memories I have of seeing some of the classic Disney films theatrically for the first time. So kiddies gather round Gran’pa while he tells you a story.

The first film I’d ever seen was Bambi. I don’t remember much about it, but I’m sure that the experience permeated my brain and sent me on a direction I could never return from. This is still one of my favorite classic Disney films. I’m not big on the cutesy aspects of the movie – specifically the “twitterpated” sequence, but I am big on everything else. Back in those days, there were often Surprise guests coming to the movie theaters to promote the shows. At this one particular event, to celebrate Christmas they drew back the curtain and had a pile of large gifts all wrapped in foil-colored gift wrap. Clarabelle the clown from the Howdy Doody Show was a special guest who was going to give out gifts to the boys and girls in the audience. He went through a short routine which ended with the supposed gift-hand-out. But it didn’t happen that way. Clarabelle took out his bottle of seltzer and started spraying the audience. The blustered theater manager called for the curtain to be closed, and that was that. Even at the age of 4 or 5, I knew we was robbed. No wonder I couldn’t remember much about Bambi.

The first film I’d ever seen was Bambi. I don’t remember much about it, but I’m sure that the experience permeated my brain and sent me on a direction I could never return from. This is still one of my favorite classic Disney films. I’m not big on the cutesy aspects of the movie – specifically the “twitterpated” sequence, but I am big on everything else. Back in those days, there were often Surprise guests coming to the movie theaters to promote the shows. At this one particular event, to celebrate Christmas they drew back the curtain and had a pile of large gifts all wrapped in foil-colored gift wrap. Clarabelle the clown from the Howdy Doody Show was a special guest who was going to give out gifts to the boys and girls in the audience. He went through a short routine which ended with the supposed gift-hand-out. But it didn’t happen that way. Clarabelle took out his bottle of seltzer and started spraying the audience. The blustered theater manager called for the curtain to be closed, and that was that. Even at the age of 4 or 5, I knew we was robbed. No wonder I couldn’t remember much about Bambi.

The second film I’d ever seen was Peter Pan. That would have been for the 1953 theatrical release. My father took me to one of those large movie palaces in upper Manhattan, the Loew’s 181st Street. I remember it playing with a film about a jungle cat of some kind; I’ve always remembered this as The Black Cat, but that title isn’t right. So I obviously don’t remember the title of the film, a B&W scary movie.

The second film I’d ever seen was Peter Pan. That would have been for the 1953 theatrical release. My father took me to one of those large movie palaces in upper Manhattan, the Loew’s 181st Street. I remember it playing with a film about a jungle cat of some kind; I’ve always remembered this as The Black Cat, but that title isn’t right. So I obviously don’t remember the title of the film, a B&W scary movie.

Re the animated feature, I remember most the swirls of color of Pan and gang flying; I don’t remember much else about it from that initial introduction. I was absolutely enamored with the moviegoing experience from The Black Cat to the brilliant cartoon. Remember, I was only 6 or 7 years old, at the time.

In 1955, I was in charge of about five kids (a couple of siblings and a couple of cousins) going to a local theater to see the NY premiere of Lady and the Tramp. Back then, it would cost 25 cents for a kid to get into the movies. When we’d gotten to the local movie theater for this film, they’d raised the price to 35 cents – more than our parents had allotted.

Outside the theater we were counting up our monies and trying to figure out how much we’d need to get in and buy some candy or popcorn for all of us. Within seconds my cousin announced that she’d lost her money, and it was obvious there wasn’t going to be enough for refreshments. The cousin started crying loudly, bawling until the movie theater manager came up to ask what was the problem. She spluttered out the word that she couldn’t afford any candy now that she’d lost the money to get into the movie. The manager just reached into his pocket and gave me an additional dollar. Enough money for movie and candy and more importantly it stopped my cousin’s screaming.

Outside the theater we were counting up our monies and trying to figure out how much we’d need to get in and buy some candy or popcorn for all of us. Within seconds my cousin announced that she’d lost her money, and it was obvious there wasn’t going to be enough for refreshments. The cousin started crying loudly, bawling until the movie theater manager came up to ask what was the problem. She spluttered out the word that she couldn’t afford any candy now that she’d lost the money to get into the movie. The manager just reached into his pocket and gave me an additional dollar. Enough money for movie and candy and more importantly it stopped my cousin’s screaming.

Once inside the theater I ignored them – even though the cousins were badly behaved and squirmed about through most of the show. I liked the film so much that I made the whole group sit with me to watch it a second time. That big, wide Cinemascope screen. It was heaven.

We did this often back then. I remember another time going to see Pinocchio with my younger sister, Christine. We sat through Pinocchio three times before we left the movie theater. That meant we had to sit through the second feature (usually some live action dud) twice to get to the third showing of the cartoon. My sister reminds me often enough that when she turned around she’d seen that the theater was empty except for the two of us. The usher stood in the back giving us the evil eye.

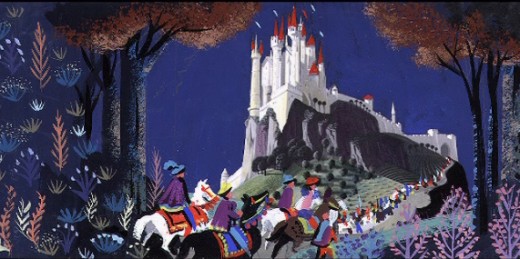

Prior to Sleeping Beauty‘s release, I’d been doing some reading. I’d received Bob Thomas’ The Art of Animation the previous Christmas, and I read it over and over at least a hundred times. I memorized every still in that book and couldn’t wait to get my eyes on Sleeping Beauty.

The film opened at Radio City Music Hall, and I was given permission to make one of my first trips downtown to see the film. An hour subway ride for a 12 year old. I went into this largest of movie theaters in the City, and I picked a great seat. The audience wasn’t overflowing; the show wasn’t sold out. But it was BIG.

The screen is enormous in that theater, and Sleeping Beauty was made to fill such a screen, especially in its Technirama debut. But somehow I came out of the theater disappointed. I don’t know what had gotten into me. I don’t remember any reason for disliking it. As a matter of fact, I absolutely love the film now. Those Eyvind Earle settings; the great animation of Maleficent; the dragon fight. There’s just a million reasons I have for loving it, but something about that first viewing left me cold. And I remember trying to analyze, at the time, what I thought was missing from the experience. I had no answer.

I’ve seen all of the pre-cgi Disney films in theaters. I also remember all the experiences of sitting through them. Dumbo and Alice In Wonderland were the only two that I saw on TV first. They were both special presentations on the Disneyland show. Eventually, I’d see them both in theaters at special screenings.

Of all of them, Dumbo still stands as my favorite though in a close tie to Snow White. There’s something they both have that goes beyond the brilliant animation and the graphics on screen. There’s an emotion there that they both have, not quite an innocence but more like a daring. Without consciously saying it, you felt the Disney people were shouting, “Look what we can do!” And they did do it. (By the time they did Fantasia, they were too conscious of what they could and had done, and they’d lost it – for me.)

Eddie Fitzgerald is either a genius or a real-life looney toon – who I treasure. Probably, I think both; he’s at least an original. His blog is like no other in that he gives us real deep rooted comedy that makes you laugh aloud. He puts together these photo-montage storyboards creating a wacky movie that you just gotta keep reading, and when he’s on the mark, there’s nothing short of brilliance.

Eddie Fitzgerald is either a genius or a real-life looney toon – who I treasure. Probably, I think both; he’s at least an original. His blog is like no other in that he gives us real deep rooted comedy that makes you laugh aloud. He puts together these photo-montage storyboards creating a wacky movie that you just gotta keep reading, and when he’s on the mark, there’s nothing short of brilliance.

Bob Clampett did a wacky WB short called The Lone Stranger and Porky. Obviously, it was a parody of the big radio show of the time, The Lone Ranger. Well, Eddie takes off on that parody and does Clampett one better. It’s crazy and hilarious and you have to check it out (if you haven’t already.) The Lone Stranger (Parody) via photomontage.

Someone should finance this guy to make a real movie. This artwork would take cgi in a direction that hasn’t been considered before. Maybe then they’d have the first REAL animated cgi film instead of all these cutesy viewmaster things we get.

Last week I started a new series that I hope will go on forever. I’ve been interviewing Independent animators, the ones who are trying to make artful animation on their own. They don’t have the dollars that a Dreamworks would, but they’re using all of their resources to make movies that have something to say.

Last week I started a new series that I hope will go on forever. I’ve been interviewing Independent animators, the ones who are trying to make artful animation on their own. They don’t have the dollars that a Dreamworks would, but they’re using all of their resources to make movies that have something to say.

The first post was an interview with George Griffin, who has been something of an inspiration to me. Upcoming this Tuesday will be an in depth look at the amazing career of Kathy Rose. She takes animation, mixes it with dance and Performance Art and comes out with amazingly original work. I’m having a good time putting these pieces together, and there are so many who deserve the attention.

- I have one last bit of self-aggrandizement to post. THis coming Wednesday, June 22nd, HBO will premiere the latest Special we’ve done for them. (Notice how I date myself by calling it a “Special”. That’s what they were called when I was younger. These days I only know the industry word for them, “one offs”. I don’t like to think of my show as a “one off”; it’s a Special.)

The show is about half animated; the other half consists of kids saying the wackiest things. It’s fun. So there you go.

Action Analysis &Animation Artifacts &Articles on Animation &Disney 16 Jun 2011 07:32 am

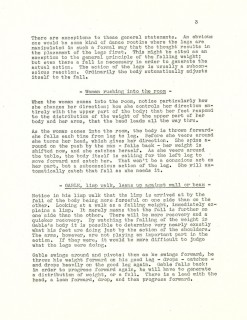

Action Analysis – March 22, 1937

- Today we continue with the Action Analysis notes from the lectures given at the Disney studio by instructor, Don Graham. The lectures, at this point, were generally built around film sequences that were screened. Oftentimes they were past Disney films, other times they were live action sequences from other studios. In this lecture, they were scenes from the Clark Gable feature, San Francisco. (This can be rented from Netflix or other distributors or can be often seen on TCM.)

The animation personnel who attended and participated included: Izzy Klein, Joe Magro, Jacques Roberts, Jimmie Culhane, Bill Tytla, Eddie Strickland, Bill Shull Moe Gollub (misspelled as Gallub) and Bernie Wolfe.

Cover

Animation &Animation Artifacts 15 Jun 2011 07:19 am

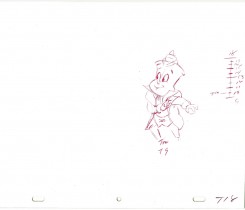

DeMattia’s Tubby

- Not every animated film is good, nor do they have good animation. But there’s usually a preponderance of workmanlike animation done for these films. Tubby the Tuba is a dog that was produced by my alma mater, New York Institute of Technology. Alexander Schure was the head of the school, and he brought it from Manhattan to Old Westbury, Long Island. He was an animation buff and wanted to be the next Walt Disney. He used his money to build an animation studio working out of his college. The studio ran through a number of heads from Sam Singer (Courageous Cat) to Alexander Schure, himself. Johnny Gentilella ultimately became the director of the project. The film took a couple of years to make with a lot of “B” animators, many of them culled from Los Angeles.

A footnote on the school was that Schure ultimately invested in some early computer animation, and though he was determined to compete with Saturday morning, limited animation quality via the computer, he financed some of the future cgi developers for animation including Ed Catmull, Ed Emschwiller and Alvy Ray Smith.

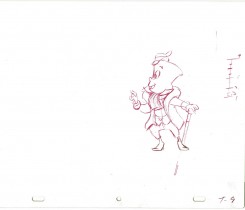

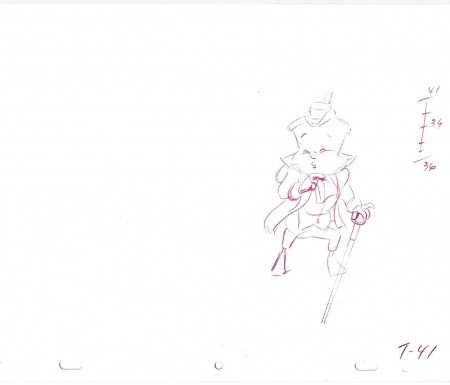

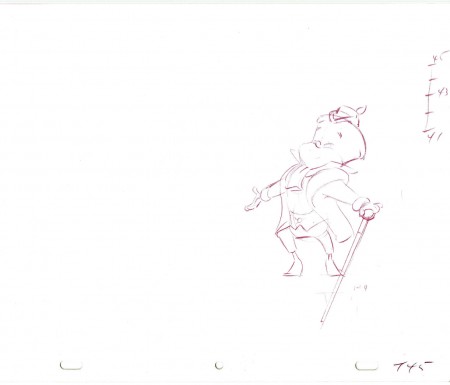

Ed DeMattia was an animator on Tubby the Tuba who did a number of scenes. I pulled one of them to give an idea of his animation. It’s surely not something worthy of study.

Since some of the drawings are just mouths calling for TraceBacks, I don’t post most of those.

1

1

________________________

.

The following is a QT of the entire scene with all the drawings included.

Since I didn’t have exposure sheets, I calculated everything on twos but

since there were only every other drawing most of the action is on fours here.

15

15