Search ResultsFor "jack zander"

Animation &Animation Artifacts &commercial animation &Hubley &Models &repeated posts 03 Sep 2012 05:11 am

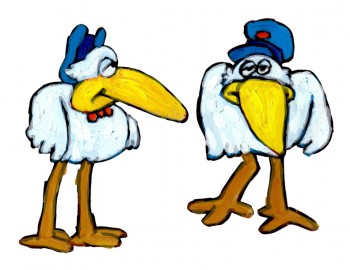

Vlasic Business at the Hubleys

– Years ago I worked at the Hubley studio on a pair of commercials for Vlasic pickles. One of the two spots made it to the air.

– Years ago I worked at the Hubley studio on a pair of commercials for Vlasic pickles. One of the two spots made it to the air.

This is from the spot that never made it.

Vlasic had a commercial they wanted, and because of the agency’s long time relationship with the Hubleys, they came to him to try to develop the character. (The agency was W.B. Doner, the agency that had done so well with Hubley’s Maypo commercials.)

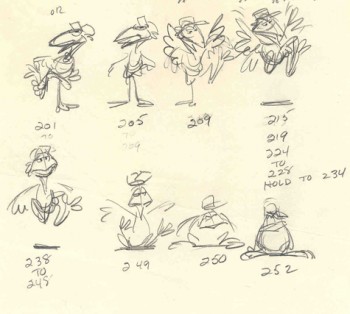

The agency came with two already-recorded voices: one was a Groucho Marx impersonator (Pat Harrington was the Groucho impersonator ultimately used for the stork’s voice.*) The other voice was character actor, Edgar Buchanan, a man with a gruff voice who appeared in a million westerns. John Hubley wanted Edgar Buchanan – it was a much richer voice, lots of cowboy appeal.

John designed the character to look like one of those stationmasters in cowboy films. The guy who gives out tickets and does morse code when he has to. The stork had a vest and a blue, boxy, stationmaster-type cap cocked off to the side. It was a great character.

Phil Duncan was the animator. A brilliant character guy who had done everything from Thumper to George of the Jungle. I loved cleaning up and inbetweening his work. It was all fun and vibrating with life.

The rough thumbnail drawing (above) fell out of one of Phil’s packages. It was a thumbnail plan of the action. Phil would do these things which usually stretched around the edges of his final drawings. In a nutshell, you could see the scene and how he worked it out. Lovely stuff.

I felt this drawing was as beautiful as the original animation drawings.

The agency approved the stork, Edgar Buchanan and the plan of action.

The agency approved the stork, Edgar Buchanan and the plan of action.

We’d already finished the first commercial which was on the air. (Represented by the two set-ups posted here.) The style was done with acrylic paints – out of a tube – on top of the cel. Ink with Sharpie on cel; paint dark colors – ON TOP of cel

- up to and over ink line; after drying we painted it again with lighter tones, and we pained it again after it dried using even lighter tones with a translucent color. Imagine kids & a gun in a spot today!)

Phil Duncan did a great job of animating it. I inbetweened, and the Agency loved it and approved it to color.

All this time, John and Faith were busy preparing the start of Everybody Rides the Carousel. It was to be three half-hour shows (Eventually CBS changed their mind and asked the shows, still in production, to be reconfigured to make a 90 min film) and was in preproduction. I did the spots on my own with John checking in. Faith wanted nothing to do with a commercial and was somewhat furious that a commercial was ongoing. She daily spoke out against this spot with many shouting matches. I never quite understood the problem. The spots didn’t hold up any other studio work; I was making it as easy as possible for John to not have to do much work on the spots, and they were getting necessary money to help finance some of the preliminary work for the Carousel. (Of course, the Hubley name was involved, but even Michelangelo did commercial work – like the Sistine Chapel to pay for the art. Not that Vlasic was the Sisine Chapel, of course.)

Within weeks the spot was in color and two junior exec. agency guys, John and I stood around the Hubley moviola. (It was a great machine with four sound heads and a picture head that was the size of a sheet of animation paper. Pegs were actually attached to enable rotoscoping!)

Within weeks the spot was in color and two junior exec. agency guys, John and I stood around the Hubley moviola. (It was a great machine with four sound heads and a picture head that was the size of a sheet of animation paper. Pegs were actually attached to enable rotoscoping!)

The two agency guys were buttoned up with good suits and briefcases. They stood behind John and me, and I operated the moviola.

We screened the spot the first time. I turned around and these two guys had come undone. Their ties were loose and astray; they were visibly sweating. I swear this all happened within the course of 30 secs.

John smiled and optimistically asked how they liked it. They looked at each other, and couldn’t answer. I don’t think they were able to form a decision or say what they actually thought. Eventually, they left with the spot in their briefcase and would get back. It wasn’t good.

John smiled and optimistically asked how they liked it. They looked at each other, and couldn’t answer. I don’t think they were able to form a decision or say what they actually thought. Eventually, they left with the spot in their briefcase and would get back. It wasn’t good.

They did get back. I was asked to pack up all the elements and ship them back to W.B. Doner. The spot was thrown out of the studio by John who refused to change it. (Hubley’s stork.)

He liked what was done, and apparently had

a rider in his contract which covered him – somehow.

The spot showed up at Jack Zander‘s studio, Zander’s Animation Parlour. They used the Groucho impersonation and slicked it up a lot. Vlasic is still using that stork, and that was John’s last commercial endeavor. The character is still showing up in a cg version, just as bad as the 2D version.

* Thanks to Mark Mayerson for this information.

Animation &Animation Artifacts &commercial animation 04 Apr 2012 07:20 am

Tangy Popeye – repost

Tangy Popeye

- Here are some of the drawings I have from what is probably the last piece of animation Jack Zander did professtionally.

- Here are some of the drawings I have from what is probably the last piece of animation Jack Zander did professtionally.

It must be remembered it was Zander’s Animation Parlour that did the TV one hour “Special”, Popeye and the Man Who Hated Laughter. I was working as an Assistant Editor at Hal Seeger’s Studio when the job came through to Seeger. He decided to hire Zander’s Studio when he got the show from King Feature’s Syndicate. It was exciting to watch, first-hand, as the show developed.

This is from a Start commercial, a Tang competitor, done at Zander’s Animation Parlour. Instead of doling out the animation, Jack was intrigued with the idea of animating the character. He hadn’t animated Popeye before.

61

61 65

65

(Click any image to enlarge.)

71

71  74

74

Do you think the assistant asked for a straight on model of Popeye’s face to do the inbetweens?

85

85  91

91

I think Jack might have been a bit out of practice when he did this spot. It looks a bit stiff.

By the way, this drawing is an example of how Jack drew

Popeye, straight on. I’m not sure anyone else used this pose.

.

Tangy Olive Oyl

– Continuing my posting of the animation keys from the Popeye Tang commercial done at Zander’s Animation Parlour back in the early 70′s. Jack Zander cast himself to animate the spot since he hadn’t worked with these characters before. (His studio did the animation for The Man Who Hated Laughter for King Features Syndicate via Hal Seeger Prods. back in 1972, but Jack didn’t animate on it.)

– Continuing my posting of the animation keys from the Popeye Tang commercial done at Zander’s Animation Parlour back in the early 70′s. Jack Zander cast himself to animate the spot since he hadn’t worked with these characters before. (His studio did the animation for The Man Who Hated Laughter for King Features Syndicate via Hal Seeger Prods. back in 1972, but Jack didn’t animate on it.)

(Click on any image to enlarge.)

On Saturday past, I put up the Popeye portion of this scene. Here are the Olive Oyl drawings. Jack has a bit more fun with her, and his drawings are much more loose.

57

57

I’d thought this was a Tang commercial, but

Charles Brubaker in the comments, below, directed

me to one of the spots on YouTube. It’s for

“Start”, which I assume was a Tang competitor.

AWN has on its site an excellent Joe Strike interview with Jack Zander about his career.

Articles on Animation 01 Jul 2010 08:02 am

Commercials History

- Earlier this week, I’d posted an excellent piece by Mike Barrier on the work of the Hubleys. This article was taken from a 1977 Millimeter Magazine animation issue. In that same issue, is an article about the history of the TV commercial. There’s a lot of good information in the piece and the shortened history of a lot of important studios that many of you are unfamiliar with. Unfortunately, it also mentions a lot of ads you may not be familiar with. But there’s plenty there in the packed piece. So I thought it a good idea to put this info out there.

Here’s the piece by Arthur Ross.

A Retrospective View

by Arthur Ross

ANIMATE, according to the time-honored Webster’s definition, means “to give natural life to; to give spirit to; to stimulate; to rouse; to prompt; to impart an appearance of life, as to animate a cartoon.”

And that is exactly what animated TV commercials have been doing for the past 30 years. They have given life, spirit, and verve to the selling of thousands of products both in America and abroad.

Psychologically speaking, they work by expanding the fixed limits of reality, by creating new and exciting worlds of fun and fantasy, and by captivating the viewer with fresh perspectives that reinforce our basic drives and motivations for love, success, beauty, comfort, and self-esteem.

During the course of a single 60 second spot, we see 1,440 individual pictures, or frames, come to life! Often with the kind of humor, or whimsy, or charm that speaks to our unguarded and childlike selves, and in some instances, even to the deepest recesses of our unconscious.

That is precisely why they are so potent a sales tool for industry, an educational device for schools, and an entertainment vehicle unto themselves. They work by playfulness, destroying all logical opposition to the messages they may contain.

They dazzle our senses and charm us into belief. Or, at least, they help suspend our disbelief in the ideas they put forth. They are 20th century dreams — dreams that money can buy!

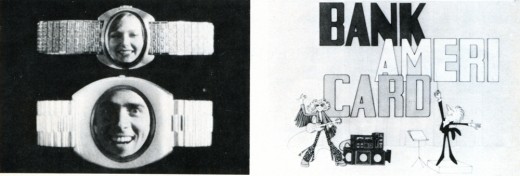

1. Object Animation: Speidel’s “Faces In The Watches”

created by John Gati of Action Pictures.

2. West Coast animation: Bank Americard (FilmFair) 1961-1976

While they operate on our most primative emotional level, animated commercials are highly sophisticated forms of art — employing words, graphics, color, motion, sound, music and symbols to activate the sale of goods and services.

Some of America’s foremost art talent has worked in the field at one time or another, including Saul Steinberg, John Hubley, William Steig, Saul Bass, to name a few.

The earliest animation in the forties was generally quite conventional — literally cartoon commercials of the straight Disney school of animation. It was essentially an extension of theatrical animation such as characterized the products of Warner Brothers, Paramount, MGM, and Disney at the time. Its novelty was successful and proved animated characters could sell products as well as live spokespeople. Everything was executed in glorious black and white, since color on TV was still years away. Commercial studios began to emerge in the late ’40s and early ’50s to supply the demand for animated spots — among them Academy Pictures, Shamus Culhane, Bill Sturm Studios, Film Graphics turning out such early “hall of famers” as the Ajax “Down the Drain” Bubbles and Mott’s “Singing Apples”.

In the early “50s a new trend entered TV commercials when UPA, creators of Gerald McBoing-Boing for theaters, introduced its unique avant-garde style of animation breaking away from the more conventional school of Disney design and execution.

We had the pleasure in the early ’50s of working personally1 with ex-UPA star John Hubley on some of the most successful of these avant-garde spots, including those for Speedway 79 gasoline, Altes Golden Lager Beer and Faygo Beverages (for the W.B. Doner agency in Detroit) as well as Chevrolet (for Campbell-Ewald, again in Detroit.) Other notable avant-garde entries during this period included the famous Saul Steinberg Jello “Busy Day” spot, as well as the classic Bert and Harry Piels spots (for Young and Rubicam).

Continuing through the mid ’50s, two trend-setting studios emerged when John Hubley formed Storyboard Inc. and Abe Liss joined forces with Sam Magdoff to start Elektra Films. Hubley continued his classic style with such winners as Heinz Worcestershire Sauce’s “Tongue-tied Spokesman”, Ford “It’s a Ford” series, and Maypo’s “I Want My Maypo” commercial. Elektra came forth with highly experimental works, creating new breakthroughs in photo-animation, multiple image and optical effects, and totally fresh avenues of design. During this time Elektra spawned such outstanding animation and graphics talents as Jack Goodford, Pable Ferro, Cliff Roberts, the Canattas, Lee Savage, Phil Kimmelman, and Hal Silvermintz, as well as Arnie Levin, Howard Beckerman, and Mordi Gerstein. Among the outstanding Elektra efforts of this era were the NBC Peacock, the legendary “Talking Stomachs” Alka Seltzer spot designed by R.O. Blechman, as well as award-winners for Chevron, Esso, Chevrolet, and Alcoa. One notable achievement, I fondly recall, was a 60-second spot done for the United States Army “Great Moments” series (which I had the pleasure of writing and producing) in which Elektra’s people (including the late Len Appleson) recreated the entire Louis-Schmelling Championship fight with stills quick-cut to the rapid beat of music and crowd cheers. It was a montage breakthrough that Sergei Eisenstein would have been proud of.

Following the success of Storyboard, Inc. and Elektra, more top studies and talent emerged in commercial animation. Pelican films emerged under the able leadership of Jack Zander and did notable work for American Motors, Volvo (designed by Mordi Gerstein) and Alka Seltzer (“The Blahs” designed by cartoonist Willilam Steig.)

Use of famous cartoonists and illustrators in TV Commercials:

Still from a commercial made in the 60s by Elektra Productions,

utilizing cartoonist Bill Steig.

Other fine studios of the fifties were those begun by Lars Calonius, Transfilm, Kim-Gifford, Robert Lawrence and Ernest Pintoff — the latter going on to win an Academy Award for “The Critic” some years later. Arnold Stone was a heavy contributor in those years to the Pintoff output, which included excellent animated spots for Proctor-Silex appliances, Yoo-Hoo Chocolate Drink, and The Bell Telephone Company.

These proved to be the “golden years” for commercial animation with many studios maintaining large staffs to cover the growing need for their excellent product. At one point, there was even a shortage of talent available to handle the work load and one had to “wait on line” for delivery.

In the ’60s, the trend increased towards graphics and we saw a sharp decline in traditional animation. New techniques were perfected — like the super quick cuts of Elektra and Ferro, Mogubgub and Schwartz. The latter also held the industry in marvelous disbelief at its outrageously “insane comic inventions” such as the award-winning “Crazy Hat” commercial for County Fair Bread (which we had the pleasure of producing with them).

Continuing the trend to more limited animation, which UPA orginated as an economical move to cope with the high cost of full animation, studios in the ’60s experimented with photomatics, “squeeze”, semi-abstracts, paper sculpture, and technique of combining live photos with animated bodies (perfected by Paul Kim of Kim-Gifford in a prize winner for the National Safety Council on preventing highway accidents.) Tighter budgets, a declining economy, and a swing away from animation to greater use of realism created massive layoffs in the commercial animation field in the late ’60s and early ’70s — and many good, long-established shops passed from the scene. Smaller one and two-man companies emerged to take their place and this trend continues up to the present day.

It should be pointed out that throughout the ’50s and into the ’60s traditional animation continued as a popular communications tool for many agencies and companies. Outstanding among these was William Tytla Associates. The late Bill Tytla was one of the foremost Disney animators, contributing greatly to the success of such Disney immortals as FANTASIA, PINOCCHIO, SNOW WHITE and DUMBO. In the ’50s, Bill took his talents into the commercial arena and did some outstanding work in the more conventional animation forms. We had the pleasure of working with him in the animation development of the worldwide symbol for Esso, “Happy the Oil Drop,” a fantasy figure that Bill brought to wondrous “life” through his skills as an animation director.

Simplicity of design in 50s & 60s; Still frame from the famous Blechman

“Talking Stomach” Alka Seltzer commercial produced by Elektra in the 60s.

In spite of downtrends in the economy, the late ’60s and early ’70s saw a brilliant new bursting forth of creative energy in animation influenced by Peter Max and the worldwide success of “The Yellow Submarine.”

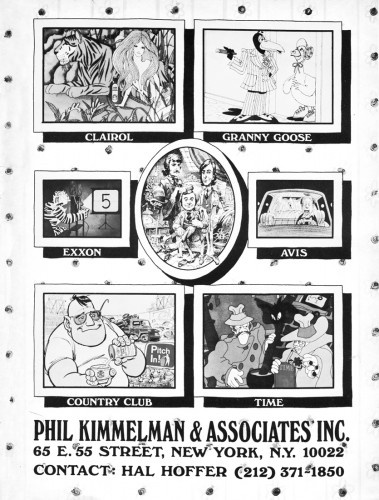

Among the many fine companies that emerged were Focus Productions, which turned out such award-winners as Vote Toothpaste “Dragon Mouth,” designed by Rowland Wilson; Gillette’s “Moveable Features,” designed by Tomi Ungerer, and the Utica Club Beer series designed by Jack Davis and Mort Drucker. In 1972, Phil Kimmelman left Focus to open his own shop, Phil Kimmelman & Associates. Here, along with Bill Peckman, he has turned out some outstanding efforts including the Cheetos Mouse campaign, the Exxon Tiger, and the delicately sensuous Clairol Herbal Essence commercial.

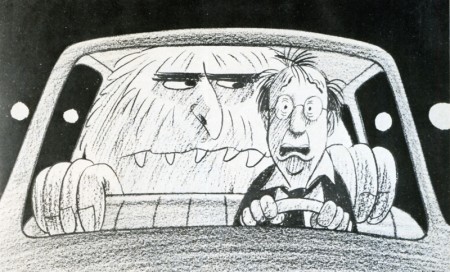

Horror Fantasy in TV commercial animation (1976): Avis Rent-A-Car;

Designer/Director: Mordi Gerstein; Producer Phil Kimmelman & Associates.

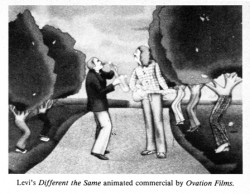

Other exciting breakthroughs in the ’70s include the highly graphic look of computer animation, perfected by such companies as Dolphin Productions for use as station and program attractions; rotoscope animation brought to brilliant maturity by Ovation Films in New York and Snazelle Films on the West Coast. The Levi campaign is an outstanding example of rotoscope animation, bringing a fresh new excitement to the field.

On the West Coast, throughout the ’50s and ’60s animation led by UP A, and Storyboard, Inc., continued to expand along with the fine efforts of such companies as TV Spots for Johnson’s Wax, Lucky Lager Beer and L&M Cigarettes; John Sutherland Productions (“A 1580 Atom”); Playhouse Pictures (Ford, Falstaff Beer, H.J. Heinz) Quartet Films (Western Airlines); Animation, Inc. for Oscar Mayer, Soho Boron Gasoline and Pabst Blue Ribbon Beer; and Five Star Productions whose animation department headed by Howard Swift (another ex-Disney man) created some of the earlier TV and cinema commercials for Ford, Pabst, F.T.D., Coca-Cola, as well as bringing Speedy Alka-Seltzer to “life” via the George Pal puppet-type stop motion use of a series of replaceable heads. Interestingly, after a decade of experimenting with other creative directions, Alka Seltzer has just reverted back to using “Speedy” again in its current advertising.

It is an outstanding example of how things come creatively full-circle and how each generation rediscovers the “great ideas” of the past.

Joop Geesink continued to perfect the puppet type animation throughout the fifties, working in Holland for American companies through Transfilm in the United States. His “Brewster, the Goebel Rooster” and Heinz Aristocrat Tomato were two fine creations in this genre.

The use of “stylized” animation-type settings in which live action unfolds was another outgrowth of animation in the late ’50s. S. Rollins Guild whom we had the pleasure of working with at McCann-Erickson in the ’60s contributed greatly to the perfection of this commercial art form for such companies as Nabisco and Coca-Cola. Both series were produced by Bill Sturm Productions in New York.

Black-Lite, while basically a live photographic technique, creates a unique “animation” look to commercials. We had the opportunity of creating and producing the first such black-lite commercial in 1955 for Flagg Brothers Shoes (“Dancing Shoes”) which won numerous Art Director Club Awards for originality and effectiveness. The producing company was Sundial Films, headed by the multi-talented Sam Datlowe. It marked the first commercial assignment for young and talented Jerry Hirshfeld, who later became the ace of the MPO Productions staff, before turning to feature films.

One of the continuing trends in animation today, largely aided by Elektra and Jack Zander in the ’50s, is the use of well-known cartoonists and illustrators from outside the industry. Among the best are Bill Steig, Frank Modell, Charles Saxon, Seymour Chwast, Milton Glaser, and Peter Max, all contributing greatly to the resurgence of animation in the “70s.

Other outstanding work in animated commercials was achieved on the West Coast by Ray Patin, whose chief animator (another Disney graduate) was Gus Jekel, now the head of Film Fair, Inc. They accomplished some fine efforts for Y&R on Jello in the early ’50s through Jack Sidebotham, one of the really great art directors in the advertising field. These include such classics as “Banana-ana,” and “Chinese Baby.” Ray Patin also turned out the NY AD gold medal Bardahl series, aping Dragnet, as well as noteworthy campaigns for National Bohemian Beer and Jax Beer.

In passing, one must not forget to include in the pantheon of animation producers such fine organizations as Cascade Productions, Playhouse Pictures, Quartet, Imagination, Inc. all of whom executed award-winning series in the ’50s and ’60s.

In the ’60s, Gus Jekel’s Film Fair did noteworthy series for BankAmericard and Bardahl which won the Cannes and Venice Awards. Today, Film Fair does exceptional work with continuing characters, such as Peter Pan (Peanut Butter). Charlie Tuna, Tony Tiger, and the Snap, Crackle and Pop trio for Kellogg’s Like Elektra in the East, Film Fair nurtured a great deal of the best West Coast talent including Art Babbitt, Bob Cannon, Dick Van Benthem, Ken Walker, Fred Wolf, Norm Gottfredson, Ken Champin, and Corny Cole. It is one of the reasons the West Coast continues to do such exciting creative work in the field along with its East Coast counterparts.

One of the long-standing successful animation partnerships in the East has been Paul Kim and Lew Gifford, doing fine work in the field since 1958. Among their top creative efforts are award-winners for Piels Brothers, and the Emily Tipp series. Their Modess a delicate subject with taste, simplicity, and artistry. And their famous Winston “Montage” introduced a 14 way split screen in constant movement to the Winston jingle — breaking exciting new ground in the use of matte work and animation design.

Another top West Coaster is veteran animator Herbert Klynn, President of Format Productions. Herb served 16 years as designer and then Executive Production Manager for UPA, before organizing his own animation company. His Format Productions is active in entertainment series such as the Alvin Shows, the Lone Ranger and Popeye programs, as well as creating titles for such TV shows as I Spy, Smothers Brothers, and The Mothers-In-Law. Among his fine animated TV commercials are those for Max Factor, Post Cereals, Wells Fargo Bank, and Dreyfus Investments. During his tenure with UPA, Herb worked on such classic film cartoon short subjects as “Madeline,” “Mister Magoo,” and “Gerald McBoing-Boing.” Our own particular favorite is his treatment of Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart” for UPA.

1. Graphic animation of a “strobe” like image of a golfer, made with 90 kodalith negatives

in registration. (World Series of Golf” Show opening by Goldsholl Associates.

2. The Unspoken Spoken Message: Modess “Because” (1962) Kim & Gifford Productions

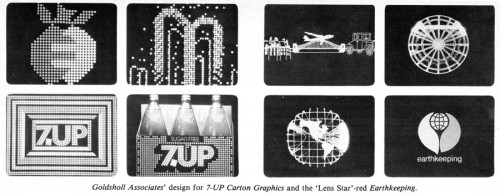

Some fine animation has come out of the Midwest, too, in recent years. A key contributer from that area is Goldsholl Associates, an Illinois-based house that has brought fresh innovative graphics and experimental style to animated TV spots. In such commercials as 7-UP’s Sugar-Free “Carton Graphics” they infuse “life” into abstract dots to create a rich new imagery on screen. Colors, shapes, and textures all impart a “meaning” experi-entally to the message.

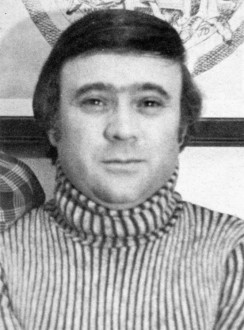

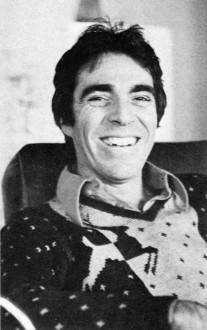

One of the more prolific of New York’s animators is Jack Zander. He began his career in 1946 at Willard Pictures doing an animated Chiclets commercial in which he animated Chiclets’ boxes like a choo-choo train to a music track taken off a 78 rpm radio transcription. In 1948, he started up the animation department at Transfilm, where he created the first animated Camel Cigarette commercials and helped develop the paper “cut-out” technique. In 1954 he and Joe Dunford opened Pelican Films and did successful commercials for over 16 years, along with Mordi Gerstein, Lars Colonius, Paul Harvey, Wayne Becher and Dino Kata-polis. During this period, Jack utilized the service of several wellknown cartoonists, including Charles Saxon for American Airlines, and later Bill Steig and George Price of “New Yorker” fame. It was also during this period that Jack did the famous Nichols and May “Jax Beer” animated series, as well as some of the early Bert and Harry Piels spots.

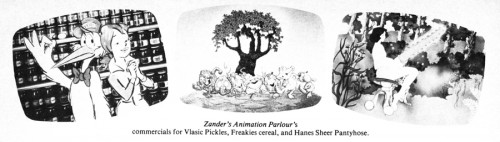

In 1970, Jack moved across the street and launched Zander’s Animation Parlor with his son Mark. He has created his share of “hits” in recent years, too, including the exceptionally fine Freakies campaign, beautifully animated by Preston Blair.

Another fine New York animation talent is Art Petricone who today heads up Ovation Films. In addition to his fine work for Eastern Airlines, his brilliant use of rotoscope can be seen in his work for Levi Strauss and Clairol Herbalessence.

In the area of object and figure animation and stop motion, John Gati, the Director of Special Effects, for Action Pictures in New York is unsurpassed. John has been working at his craft for 26 years and has won many awards for technique and innovation.

The art of Object and Figure Animation requires enormous craftsmanship. Basically, it resembles conventional (drawn) animation in that it follows the rule of “creating the movement” by the process of frame by frame photography. But as opposed to eel animation, which occurs on a two dimensional (acetate) surface, Object Animation is similar to live action photography taking place in a three-dimensional area.

John Gati’s creations succeed in making the product itself (the object) become the hero of the commercial, which is one of the basic tenets of good “sell” advertising. Complicated rigs and special dimensional lighting are required to make this form of animation truly work. It requires enormous intricacy to sustain the fantasy of “life” for these objects. John works with such materials as foams, wires, rubbers, vinyls, plastics, silks, clays and waxes to create the illusion of “reality.” Working in the tradition of the great artists and artisans of the past, John — like McLaren and Trnka and Geesink — has created a wondrous world of living and moving objects that reflect a “life all their own. Among his most recent successes are Fleischman’s “Egg Beaters” and Speidel’s “Faces In the Watch-bands. ”

In passing, we would also like to salute the following fine practioners of the art: Snazelle Films and Kurtz and Friends for their fine Levis efforts; Bill Melendez (Bill Melendez Productions); Hal Silvermintz (Perpetual Motion); Carlos Sanchez (IF Studios); William Littlejohn (William Littlejohn Productions); and Art Babbitt (Hanna-Barbera Commercials.)

The boundaries of animation are limitless. They defy time and space. They fuse reality with fantasy. They create new life out of old forms. Most animators believe the future will see the development of completely new and exciting techniques for the art. More use of famous illustrators and designers from the non-animation world. New developments in computer animation. More combinations of live action and animation within the same frame. More sophisticated “selling” within the framework of fantasy and humor. New breakthroughs in stop motion object animation. Fresh combinations of tape and film in animation. Unusual variations on dimensional and multi-plane animation effects.

For the most part animators strongly feel animation commercials can achieve greater results than live action, because “they can be funnier and they can be controlled absolutely” (Lee Savage); “You can get information across quicker” (Bob Godfrey);” ” “Animation makes an incredible statement real… In animation, sweeping moves are totally acceptable as opposed to the heaviness of human action (Mort Goldsholl).”

What is evident, too, is that small teams are creating the most significant new work in animation today. While the Disneys and Hanna-Barberas continue to produce a great volume of praise-worthy animation for film and TV, the breakthroughs are, for the most part, coming from the isolated artists and small creative teams working throughout the country.

And bridging the gap between these artists and the advertising agencies are producers like Harold Friedman of The Directors Circle, who fully understand the needs of both parties for creative expression, on the one hand, and sound selling messages, on the other. In the final analysis, an animated commercial to be successful must motivate the consumer to buy the product, or the service, or the idea put forth by the commercial. That is its major raison d’etre. It should be charming, to be sure, and filled with fun and fantasy — but it must ultimately sell its clients’ products in the marketplace to achieve its truest objectives.

Articles on Animation 16 Jan 2009 09:42 am

NY Makes it Big

- For as long as I can remember, we, in NY, have been told that the big studio is returning. Again and again we hear that lots of big projects are coming, and we’ll all have to gear up for the glory days. I saw this with Raggedy Ann & Andy; I heard this with Shamus Culhane studio’s Noah’s Ark series of 1/2 hours (before he skipped town to do them in Italy.) It was obviously happening with the advent of Doug, and then MTV, or Courage the Cowardly Dog, or whatever.

- For as long as I can remember, we, in NY, have been told that the big studio is returning. Again and again we hear that lots of big projects are coming, and we’ll all have to gear up for the glory days. I saw this with Raggedy Ann & Andy; I heard this with Shamus Culhane studio’s Noah’s Ark series of 1/2 hours (before he skipped town to do them in Italy.) It was obviously happening with the advent of Doug, and then MTV, or Courage the Cowardly Dog, or whatever.

It always seems to get back to a few smallish studios (like mine) doing individual work. That’s jsut the way it is.

Here’s an article John Canemaker wrote for Millimeter magazine back in January 1981 (a year after I’d formed my studio.)

Return of “Long” Cartoons

by John Canemaker

Recently, New York’s animation industry has been enjoying the flattering attention of the television networks in the area of TV specials and series. Last year, three animated prime-time specials and one Saturday morning series (live-action with animated segments) were produced in the Big Apple. With three specials currently on the drawing boards at one studio, and proposals for “longer” shows being prepared by several other local houses, it appears the East Coast, particularly New York City, is witnessing a new and healthy growth in television cartoon production.

Recently, New York’s animation industry has been enjoying the flattering attention of the television networks in the area of TV specials and series. Last year, three animated prime-time specials and one Saturday morning series (live-action with animated segments) were produced in the Big Apple. With three specials currently on the drawing boards at one studio, and proposals for “longer” shows being prepared by several other local houses, it appears the East Coast, particularly New York City, is witnessing a new and healthy growth in television cartoon production.

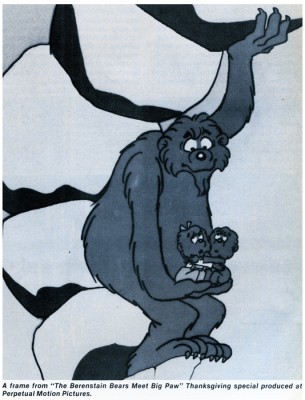

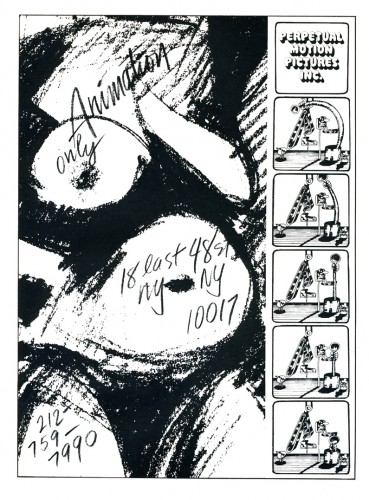

Busiest and one of the largest of the New York studios is 12-year-old Perpetual Motion Pictures, whose 1979 half-hour NBC special, “The Berenstain Bears’ Christmas Tree,” was the fifth highest rated out of 70 specials that year. The show’s success led to 1980′s “The Berenstain Bears Meet Big Paw,” aired during the Thanksgiving holiday, and a repeat of the Christmas show. This spring will see “The Berenstain Bears’ Easter Surprise” and in 1982, “The Berenstain Bears’ Comic Valentine.” In addition, Perpetual Motion is producing a special which may develop into a series, “Strawberry Shortcake in Big Apple City,” as well as its usual 60 to 70 commercials each year.

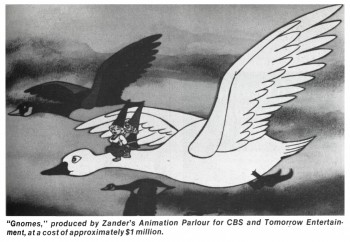

Zander’s Animation Parlour, which occupies two floors in midtown Manhattan and (as its ads say) has been “keeping the nicest company for 10 years,” managed to produce its annual load of commercials (close to 100) while producing the hour-long special, “Gnomes, “based on the best-selling picture book, for CBS/Tomorrow Entertainment.

The well-established Kim & Gifford Productions Inc. also completed a full complement of titles and commercials while producing the animation for the NBC kidvid series, “Drawing Power,” produced by the creative team of George Newall and Tom Yohe. “Drawing Power,” the only new entry in Children’s Programming on NBC’s line-up of Saturday daytime programs last fall, was Newall and Yohe’s first series, although they previously produced “Schoolhouse Rock” cartoon inserts for ABC and “Metric Marvels” for NBC.

Exploring the significance of increased production

Buzz Potamkin is the 35-year-old president of Perpetual Motion Pictures. He is fond of quoting Pasteur’s, “Chance favors the mind that is prepared” to explain his studio’s dominance in the production of East Coast cartoon specials. “My partner, Hal Silvermintz, and I decided back in the early ’70s that we wanted to get into the programming area. So when opportunities arose, we took advantage of them.” Perpetual produced animated segments throughout the last decade for NBC’s “First Tuesday,” “Grandstand” and “Weekend,” among other shows.

Potamkin acknowledges a “strong negative reaction against New York City about 10, 15 years ago” on the part of TV programmers. “First, the rise of the TV commercial industry in New York required a different production flow than animated series produced on the West Coast. From a production point of view, more care than is necessary is put into a commercial. The best people went into commercials because the money was good and that was the market available in New York City. There were a few shows done in New York 10 or 12 years ago, but they were not done well—bad scripts, the wrong people working on them, not enough money, wrong concepts. And because there were so few of them done in New York, it became axiomatic that if you do it in New York, it’s going to be bad.

“Secondly,” continues Potamkin, “Hanna-Barbera had discovered a way to produce animation less expensively. That spread like wild-fire through the West Coast, so the West was being set up to produce less expensive, longer animation, and the East Coast to produce short-form, more expensive animation. And the labor pool followed that. We still have a local labor pool of perhaps 300 people as compared to 2500 people on the Coast.”

Jack Zander, who started in the animation business in 1931, recalls network negativity about the smaller New York talent pool. “A lot of people said you can’t make a long film in New York because there are not enough good animators. I said that’s not true!”

Potamkin feels the turning point in this attitude came about three years ago. “The West Coast,” he explains, “became overloaded. With the networks pushing back their pick-up dates for Saturday morning to such an extent, for that six-month period that there was work on the West Coast, you literally couldn’t fit a special in anywhere.”

Network producers began to compare the quality of East and West Coast animation, and as Zander points out, “some commercial clients expressed the opinion that the California group of animators has been working so long on Saturday morning stuff that all their animation looks alike.”

Network producers began to compare the quality of East and West Coast animation, and as Zander points out, “some commercial clients expressed the opinion that the California group of animators has been working so long on Saturday morning stuff that all their animation looks alike.”

Potamkin agrees: “With the tremendous footage requirements per week, a lot of very good West Coast animators forgot how to animate. They have difficulty getting back into fuller animation. The networks became aware of this as their specials tended to drop off in quality level.”

“New York animation,” begins Tom Yohe of “Drawing Power,” is just crisper. There is something about the formula look to Saturday morning animation done’on the West Coast—a tendency on the Coast to take a budget and figure if you have so much a minute, that comes out to three drawings a second, or whatever. I think budgets are utilized in a much more thoughtful way by New York animators, like Kim & Gifford’s Al Eugster. Here you have a scene of limited animation or a pan across something, then in another scene you heavy-up the animation. So the overall feeling is more properly paced and gives you a feeling of fuller animation than you get from the formula stuff coming out of most West Coast studios.” I Lew Gifford adds, “There’s plenty of I talent around New York. Often East Coast animators go west for work. I can see the West Coast animators coming here under the right circumstances.”

More studios available.

Another factor in New York’s favor is I the current availability of New York studios with the physical space and personnel necessary for the production of longer films. Zander cites “relatively cheaper costs in L.A. in terms of film footage and work space. And people at the networks are impressed by the space in L.A. Big rooms with lots of people sitting in them—it is important.” Potamkin agrees. “For the first time in 10 years,” he says, “two studios grew up in New York, Perpetual and Zander’s, that were large enough for someone to say, ‘we can trust them with a project this size.’ We’re not four guys sitting in an office somewhere.”

“Perpetual was being forced to consider having to relocate its studio out of New York because of the difficulty in finding a suitable studio area,” comments Nancy Littlefield, head of the New York City Mayor’s Office of Motion Pictures and Television. Potamkin acknowledges that the City’s support was especially helpful “when it came to negotiations over the space—having a couple of people from the City call the landlord and say we don’t want you to lose money, but we really want these people to stay here.” Perpetual moved into its new 11,000-foot space last June with a 10-year lease and Potamkin adds, “We intend to stay here.”

Under Potamkin’s supervision, Perpetual’s “Big Paw” special required one board and track director, one animation and layout director, five animators, six assistant animators, six in-betweeners, a production coordinator, three checkers, two Xerox operators, 20 opaquers, a camera service and so on, through other divisions in the studio’s staff of 67 full-time employees.

Zander’s Animation Parlour normally staffs about 25, plus freelancers, but hired about 85 for the “Gnomes” special. Lew Gifford of Kim & Gifford estimates he has a dozen on staff, but added six or seven animators when his company was preparing the animation for the Saturday morning series, “Drawing Power.” “We have been successful,” he points out, “in not raising the amount of space we have. For a six-to-eight-month run, you don’t want to raise your space.” He notes that the Astoria studio facility in the New York borough of Queens “has space for both live action and animation, and that’s a possible space factor for expansion of facilities.”

The bulk of the preparation for “Drawing Power” came from its two energetic young producers, George Newall and Tom Yohe. “We had a tight schedule,” recalls Yohe. “We got a very late pick-up at the end of April for an October 11 premiere.” Newall adds, “When we got the order, we just started working night and day. Never having done it before, and not even sure we could do it, we worked a lot harder than we might have.”

The informational series takes place, interestingly enough, inside an animation studio. “The show needed animation to be competitive on Saturday morning,” Yohe explains. “We were very lucky in regard to the crippling SAG strike; in six or eight weeks we had all our tracks written and recorded and to the animators before July, so we beat the strike. The live action was under an AFTRA contract; we shot tape during daytime, so we were able to stay in production right through the summer when a lot of guys had to close down.”

Yohe figures that one reason they were able to produce “Drawing Power” without taking on a large staff “is the segments of animation are short—none lasts more than 45 seconds.” The cost of the animation was “in the $7000 per minute range, without tracks.” There were 12 shows containing 10 minutes of live action, with about 14 minutes of animation per show at a cost of about $150,000 per show, or “equivalent to what Hanna-Barbera gets.”

No immediate profit

The half-hour specials of Perpetual Motion are budgeted roughly in the $400,000 range, according to Potamkin. “But costs are inching up now to about $450,000 per. All network shows have relatively me same budget because that is what is available to be spent. Frequently that’s more than the networks are willing to spend! Making specials is not as immediately profit-oriented as making commercials. With commercials, you know what the profit is going to be. With shows, that is not true. The profit doesn’t exist up front. The chances of someone paying $750,000 for a half-hour special in today’s market is very, very unlikely. One has to accept the reality that you’re going to make less money. A lot of people in this business of animated commercials don’t want to accept this.”

Zander’s “Gnomes” had costs that “hovered around one million bucks, which,” says Zander, “is a lot of money for an hour show. The standard rate for an hour special is $750,000, but CBS and Tomorrow Entertainment threw in some extra money and brought it up to the point where we could do something with it.” The 48-minute, 16-second special took almost two and a half years to see completion. Explains Zander, “It took a year or two to get a good story. The script had to be redone. After that, there was still a year’s work in animating.”

Zander’s “Gnomes” had costs that “hovered around one million bucks, which,” says Zander, “is a lot of money for an hour show. The standard rate for an hour special is $750,000, but CBS and Tomorrow Entertainment threw in some extra money and brought it up to the point where we could do something with it.” The 48-minute, 16-second special took almost two and a half years to see completion. Explains Zander, “It took a year or two to get a good story. The script had to be redone. After that, there was still a year’s work in animating.”

Zander believes that for half-hour specials, “money is not too hard to come by if you find a good property.” But he speaks candidly about the dangers of “animators almost pricing ourselves out of business. We’ve just signed a new contract with the union [Motion Picture Screen Cartoonists, Local 841]. Really, the wages are going up pretty steep. Minimum for an animator is close to $550 per week, and categories below that have come up, too, like inkers, painters getting about $250 per week.

“One time,” recalls Zander, “we had a separate contract for long films. Now in my mind, if you guarantee a person work for a year at $400 a week or whatever, that’s better than working catch-as-catch-can for $600. And it makes it more appetizing for somebody to invest in a film. I think,” continues Zander, “applying commercial rates to feature films is not going to help us. We do a half-minute commercial now for about $20,000. Multiply that by 30 minutes. That makes animation an awfully expensive medium! If we are now seriously considering bringing longer films back to New York, and they are considering us, we’re going to have to work out a different contract.”

Interest in longer films

Indications are that the opportunities to do longer films in New York will continue to occur. “I think the reputation of the City has shifted,” claims Potamkin. “Doors closed to us are now open. People are more willing to talk to us now. I’m sure Jack (Zander) is having the same experience. And they’re not just talking to us as a production office, where work is shipped toL.A., Japan, Europe, but produced right here in NeW York. I know the union is very Happy abouht, lopuhtmildly.”

“The day after ‘Gnomes’ was shown,” recalls Zander, “I got three phone calls from people who have properties they want made into specials. I’m interested, despite the hard work, because, first, it was a lot of fun. Very gratifying, too. I personally put in time on weekends. I enjoyed the challenge and my staff did, too!”

“I don’t know if it’s a trend,” points out Yohe. “I think the networks are happy with the animation they’re getting from us. We’d like to do an animated special at this point. We have things sitting on desks at the three networks, but it’s so unpredictable. They do have an interest in having production done here. It’s also very nice for the children’s programming people here to be able to pop in and look at things without a trip to the Coast.” Newall adds, “We’ve been in business for three years and have yet to set foot in California. And now that the air fares are going up, we’re even less likely to go!”

Lew Gifford finds that “there’s a lot more fun in doing things that you can continue for a long period of time, providing they’re of high quality. There is still a great deal of fun, in solving problems for advertising agencies, but it’s not the same thing as doing an entertainment.

“In the commercials business, you’re lucky if you can look two months ahead. The significant difference,” Potamkin states, “is that instead of being tactical planners where we plug up the dikes and the anxiety about how long the work is going to last, now we can get into strategic things—two we’re finishing, roll over, do one more, plus commercials. What should we do after that? Who should we be talking to? How do we want to bring our younger people along, which we’ve always had a commitment to doing?”

Potamkin has every right to feel confident and secure about his studio’s future in animation produced in New York. “For the first time,” he states “since Hal Silvermintz and I opened this studio 12. years ago, we can look a year ahead and know—bottom line minimum—the work that we have. For a year,” he emphasizes.

Articles on Animation 18 Dec 2008 09:07 am

Spots – 1976

- Back in 1976 John Canemaker asked if I was interested in writing a piece on commercial studios for Millimeter Magazine. I was interested and took the job (while at the same time working at the Raggedy Ann studio.)

- Back in 1976 John Canemaker asked if I was interested in writing a piece on commercial studios for Millimeter Magazine. I was interested and took the job (while at the same time working at the Raggedy Ann studio.)

I found that commercial production was on a downswing and theatrical production up, keeping a lot of the smaller studios operating. That became my thesis for the piece, and I got in trouble for speaking my mind. One producer I praised said I was on his “s##t list” and I didn’t have to bother applying at his studio for a job. Since I had never sought work in his company, I found the thought amusing but was still confused that he’d found my article bothersome.

Looking back on the article now, I see that it was much ado about nothing; the article is and was harmless. However, it does give an overview of the commercial world – particularly in New York. Hence, I thought I’d entertain myself by posting it.

As much as 20 years ago, the animated commercial was fast becoming a viable art form. Bert and Harry Piels and Marky Maypo had already entered our lives via the television spot, and audiences waited through many an hour of mediocre TV presentations to be entertained by such characters in their one-minute commercial messages.

As much as 20 years ago, the animated commercial was fast becoming a viable art form. Bert and Harry Piels and Marky Maypo had already entered our lives via the television spot, and audiences waited through many an hour of mediocre TV presentations to be entertained by such characters in their one-minute commercial messages.

Commercial studios competed with one another to produce higher quality productions and more popular and entertaining films. The studios were major ones employing up to 75 people to produce their work. UPA, Academy, Storyboard, Pelican, and Elektra all existed with creativity and design strongly apparent in their storyboards and continuing right through to their finished product.

There was much experimentation in design and approach. The public readily accepted the new styles which they rarely saw or sought in theatres. (Even the trend setting UFA films of the early 50′s didn’t really receive audience acceptance till the arrival of these commercials.) The workers and producers alike took pride in their commercial product, and the results showed in the finished films.

Needless to say, many things have happened in the past 20 years. TV animation took a turn for the worse. Saturday morning, which had been filled with Mighty Mouse, Winky Dink, and Ruff and Ready filtered into a heyday for revitalized prehistoric monsters sliding across the screen with a superhero or two or seven talking for endless hours. Mind you, nothing moved but the sliding monsters and their mouths, but the networks bought it.

The animated commercial also took a nose dive. Individuals from these large studios began setting up their own one- or two-man studios. Their overhead was lower and, naturally, could come up with a lower bid for the commercials. The larger studios couldn’t compete with them and, as a result, became smaller. Dozens of people were thrown out of work. They were made to fight for freelance work from these small studios, change their careers midstream, or retire from their art. Many a good animator, assistant animator, inker or background artist was lost to the system. The result of underbidding was that the budgets never increased while the cost of animation became prohibitively expensive. The producers were forced to find new methods of presentation to stay alive in the commercial market.

The “classic” commercial became a rarity rather than the norm. Even the time allotted the producer to relay the message was reduced. The spots went from 60 seconds to 30 or even 20. The commercials, like Saturday morning TV, became limited in imagination, if not in animation. The agencies took charge of the writing for all campaigns, and more often than not creativity was lacking by the time the producer-had received the spot. There was too much concern for the statistics of the testing and too little concern for what was entertaining as well as selling. When the storyboard was lacking in creativity, even the most conscientious producer was able to do little more than contribute good production values to the finished spot. The spark had been eclipsed.

It is common knowledge that the film business, particularly animation, has had an inordinately poor first half of 1975. Many an animator, unable to find work at any studio, was ready to move for the sun and retire. There was just too little work on the boards. Agencies were looking for live action; a large number of spots were being sent out of the U.S., and a large number of non-union people were competing with and undercutting the established producers (the agencies didn’t seem to mind the cut in production values if they could get the spots done less expensively). With all of these problems apparent, it seemed difficult to imagine how a production house could, indeed, remain in operation.

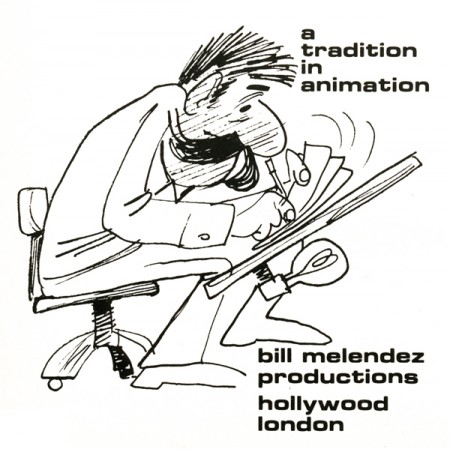

Toward mid-year, a number of theatricals began to creep into production: THE METAMORPHOSIS brought a new company, San Rio, into being, while RAGGEDYANN AND ANDY brought a theatrical producer, Lester Osterman, into animation; Ralph Bakshi continued his films, COONSKIN, HEY GOOD LOOK-IN’, and THE WAR WIZARDS, while Alexander Schure brought his college, New York Institute of Technology, into production of the feature TUBBY THE TUBA; a third Charlie Brown feature began production at Bill Melendez’ studio, while the 24th feature, THE RESCUERS, began production at the Disney studio. Business in animation was returning to the theatres, just when it seemed that the animated commercial was hardly capable of supporting any studio.

The Hubley Studio, owned and operated by John and Faith Hubley, was formed from Storyboard, Inc., the company set up by the Hubleys in the early 50′s after John had left UFA and he’d met Faith. Storyboard’s commercial films were unique, clever and consistently high in quality. Marky Maypo’s dialogue still exists in the minds of most of TV’s first generation of viewers. The Hubleys used the commercials to pay for their theatrical ventures. Eventually, they moved almost completely to the production of these personal, theatrical films.

The most recent of these personal films is a 90-minute TV production, produced by CBS. Everybody Rides the Carousel is based on the writings of Erik Erikson, the noted psychologist. The film shows the development of a person in a society. This is, obviously, unique material for animation, not to speak of TV animation. It will be curious to see if any effect will be made on other animated programs.

The Peanuts specials, needless to say, have had a great impact on television animation, if not on all phases of American society. Bill Melendez runs the studio that has been producing these films. His studio has been operating for the last 12 years, but, obviously, never has it been so successful. There have been two feature-length films to spin off the very successful TV specials, and now a third theatrical film is in the works. Curiously enough, the few commercials that move through the studio are Peanuts-oriented. At the moment there are two spots being produced for Japanese television starring Charles Schulz’ characters. The studio, thanks to Peanuts, is able to keep a staff of, at least, 15 people on full time.

Most of the other commercial film producers are beginning to look into theatricals. Phil Kimmelman, producer and executive member of Phil Kimmelman & Associates, continued his use of noted designers (Jack Davis, Mort Drucker and Rowland Wilson, who has become an important mainstay of the studio, had designed ads and episodes of Scholastic Rock) when they commissioned Gahan Wilson to design a Halloween special for television. The prospect never passed the boarding stage, since the money ran out. They are still hoping for a backer.

Other studios such as Zander’s Animation Parlour and Ovation, which normally produce only commercials, (Jack Zander had directed the TV feature The Man Who Hated Laughter, and Ovation is currently making a 10-minute industrial film) have said that they are interested in making theatrical films, but they want to be sure that the budgets are large enough.

The problems involved in searching for theatrical films from the vantage point of a commercial film producer can be best illustrated by demonstrating the situation at Perpetual Motion. Studio heads Buzz Potamkin and Hal Silvermintz openly stated that they want to enter the theatrical market. They have been producing a series of low-budgeted spots for NBC’s network, late-night program Weekend. The show is aired the first Saturday of each month on NBC. Each program incorporates in its schedule one or two animated, editorial cartoons. These are usually satirical comments on some phase of the current news stories. Both producers enjoy doing these films since they’re given a freer rein than they usually have with the commercials. Stylization, story and design all combine to make miniature entertainment films for television. They would like to begin a longer film, but they want to make sure that it’ll be a project they’ll enjoy working on for the year or two it’d take to complete.

Buzz Potamkin left little doubt that he thought the animated commercial was far from dead. He stated that he expects this to be far from Perpetual’s worst year, however, if it weren’t for the Weekend spots and several jobs for NBC Sports (animated spots for Joe Garagiola’s pre-game show), the studio might have had a much poorer year. These short films allowed Perpetual to maintain a staff, however minimal.

Morton and Millie Goldsholl are designers in the Chicago area who operate a studio which includes three full-time animators who are capable of table-top, stop-motion films, as well as cel animation. Morton Goldsholl states that half the studio’s film work is in longer films. They have produced a large body of work with some 12 titles listed among their experimental films. Much time is spent in experimentation, and, consequently, they have developed a “strange optical method” which is called “Lens Star.” The end result is a product which bears a resemblance to the “computer image” but, in fact, retains the warmth of the human touch. This method was used in a title to Earthkeeping, an ecology series. The 60-second title represents the beginning of life to the present ecological dilemma.

The Goldsholls seem to have touched on the best of both worlds, and perhaps this is actually what the majority of the commercial studios would like to strive for. They produce a number of commercials each year while still making the short industrial films. This has kept their studio very busy in the past two years.

Commercials, of course, have not disappeared, nor have they been as poor as this article might have led you to believe. There were a number of well-produced spots within this last year, and most of the studios can admit to a good second half of 1975. At the moment, several of the studios are at peak production.

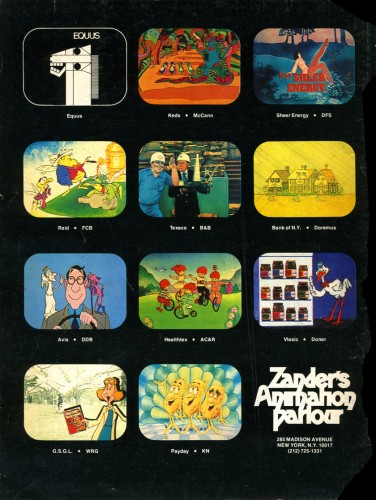

Zander’s Animation Parlour is New York’s largest commercial producing studio. They are presently able to maintain a staff of 25 people to handle their film production. Jack Zander, a long- time veteran animator, heads the studio since 1970 when his studio, Pelican, closed. A large number of specialized commercial films are produced at Zander’s. The spots for Freakies breakfast cereal, animated by Preston Blair, have achieved quite a bit of success. Each eel is a major rendering effort, being prepared with colored pencils on colored paper and pasted to the celluloid sheets. The same method of rendering was employed in the most recent Vlasic Pickle commercials and the Hanes Sheer Pantyhose ads. The studio artists combined live-action with animation successfully on the spots for Dayton’s, a department store located in Chicago, and in an ad for Texaco.

Perpetual Motion has done a spot for Baggies which they are quite proud of. The commercial was designed by Hal Silvermintz. A recent AT&T corporate spot was designed by Guy Billout and animated by Vinnie Cafarelli and Vinnie Bell. Perpetual also has recently acquired the Schickhaus commercials, and for the past year, they have produced the Hawaiian Punch commercials. With these spots, they had a somewhat interesting problem: they were given an established character and design style and told to continue the series in the same vein. They’ve been successful.

Phil Kimmelman & Associates had a slightly different problem with the Cheeto’s Mouse. They were given these spots several years back. The client had been unhappy with the results he had received from other studios. Kimmelman has had the spots ever since. Bill Peck-man, a designer at the studio and a board member of the group, stated that these spots give them a chance to explore a bit with nuances in character. Since they’ve been handling the character for a while now, they feel that they can have some fun with him.

This is all quite interesting when you realize that they have just recently begun producing a number of commercials for Piels Beer which star Bert & Harry Piels.The studio has asked to continue the line of commercials done in the 50′s by UPA. The result was several 30-second spots starring the two characters (once again voiced by Bob and Ray). Kimmelman remarked that he found himself using several of the artists who had worked on the original films (Lu Guarnier had animated the spots at UPA in the 50′s and worked on them again in the 70′s). The only difference between these commercials and the earlier ones is that these are in color.

This is all quite interesting when you realize that they have just recently begun producing a number of commercials for Piels Beer which star Bert & Harry Piels.The studio has asked to continue the line of commercials done in the 50′s by UPA. The result was several 30-second spots starring the two characters (once again voiced by Bob and Ray). Kimmelman remarked that he found himself using several of the artists who had worked on the original films (Lu Guarnier had animated the spots at UPA in the 50′s and worked on them again in the 70′s). The only difference between these commercials and the earlier ones is that these are in color.

Bajus-Jones was formed six years ago in Minneapolis by Mike Jones and Don Bajus. The main office remains in that city, where some 14 people are employed. The studio has representatives in Chicago and New York, and some production is done in New York. Their work has principally been the making of animated commercials—recent commercial productions include a spot for Phillips Petroleum, and one for GMC Truck division— but they are now at work on a pilot for a feature-length film.

Ovation is owned and operated by Jerry Lieberman, Howard Basis and Art Petricone. Their most recent pride is for a number of spots just completed for Whitman’s Chocolate. The commercials, animated by Doug Crane, are done in the style of the sampler on the box of the chocolates. The end result is an animated crewel that is quite effective. Also of interest from the studio is a Clairol Herbal Essence spot which has a live-action figure walking through an animated garden of earthly delight. This is also the studio that did the campaign for Eastern Airlines. Each commercial incorporates a great number of animated figures. The detail is staggering.

Ovation is owned and operated by Jerry Lieberman, Howard Basis and Art Petricone. Their most recent pride is for a number of spots just completed for Whitman’s Chocolate. The commercials, animated by Doug Crane, are done in the style of the sampler on the box of the chocolates. The end result is an animated crewel that is quite effective. Also of interest from the studio is a Clairol Herbal Essence spot which has a live-action figure walking through an animated garden of earthly delight. This is also the studio that did the campaign for Eastern Airlines. Each commercial incorporates a great number of animated figures. The detail is staggering.

Several studios consider themselves, basically, graphic design studios. The work of the Goldsholls was previously mentioned, though indeed, their commercial work is outstanding. A recent one for 7-Up received well-earned celebrity among TV spots. Their Gillette Right Guard ads employed rotoscoped animation within the graphics. Just recently begun were two fully animated spots for Kellogg, which Morton Goldsholl feels will be a milestone for the studio.

George McGinnis and Mark Howard are the proprietors of the Image Factory. The two producers are designers who would like to see greater use of design and camera in animated films. This approach is, obviously, echoed in their film production. They’ve designed and directed the introductions for the five Mobile Showcase Presentations; (this included the famed TV productions of Moon for the Misbegotten and Queen of the Stardust Ballroom.) They’ve also designed the end logo used in the Metropolitan Life Insurance campaign. They’ve produced the Fall campaign for the CBS-owned and -operated stations. The two producers have a strong interest in moving toward more wholly animated projects, and their final goal will be reached when they can successfully see the combination of animated graphics with in-depth character animation.

George McGinnis and Mark Howard are the proprietors of the Image Factory. The two producers are designers who would like to see greater use of design and camera in animated films. This approach is, obviously, echoed in their film production. They’ve designed and directed the introductions for the five Mobile Showcase Presentations; (this included the famed TV productions of Moon for the Misbegotten and Queen of the Stardust Ballroom.) They’ve also designed the end logo used in the Metropolitan Life Insurance campaign. They’ve produced the Fall campaign for the CBS-owned and -operated stations. The two producers have a strong interest in moving toward more wholly animated projects, and their final goal will be reached when they can successfully see the combination of animated graphics with in-depth character animation.

Edstan is run by Stanley Beck and Ed Feldman. They are a graphics studio which will put the designs brought to them on film. They recently produced the graphics for NBC, CBS and Metromedia’s Fall campaigns. They also produced the opening graphics for the networks’ film programs. The studio has been in operation since 1959 and has produced a large number of network titles (most of the late night movie titles were produced at Edstan.)

With the Cheeto’s mouse, Freakies’ freakies, the Hawaiian Punch character, Vlasic’s stork, and the revival of Bert and Harry, it looks auspiciously as though animated commercials are turning toward the characters to entertain us. Perhaps this will be the trend; the agencies will spend more time caring about the viewer and a lot of good animation will come across the TV sets in America.

Animation Artifacts &Articles on Animation &Bill Peckmann 11 Dec 2008 08:33 am

Ads for Ad Companies

- Flipping through some old film and animation magazines, I couldn’t help but look at all the old ads for the many animation companies that were ever present and are now gone. In a way, back then, you were pleased to see the small companies that promoted themselves regularly in all the film mags.

- Flipping through some old film and animation magazines, I couldn’t help but look at all the old ads for the many animation companies that were ever present and are now gone. In a way, back then, you were pleased to see the small companies that promoted themselves regularly in all the film mags.

You have to remember that animation wasn’t all present back then. It wasn’t easy to find a lot about the medium. Now you just turn on the computer, but back in the ’70s you bought a magazine and cherished the few articles. And when you found something like the Film Comment issue of 1975 (though there were no ads for animation companies in that issue), you kept the magazine close and read and reread the articles. Then you looked at all the ads for the boutique commercial companies.

The following ads all came out of three issues of Millimeter one from 1976 two from 1977.

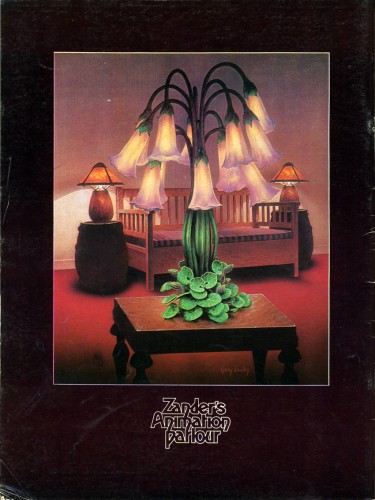

Zander’s Animation Parlour was the largest commercial company

in NY in the 70′s and their ads were the biggest and most entertaining.

They often appeared on the back cover of these magazine issues.

Ads changed from issue to issue, so someone in the studio

kept designing them. Jack Produced the spots with animators

Doug Crane, Dean Yeagle and Bill Railey on staff.

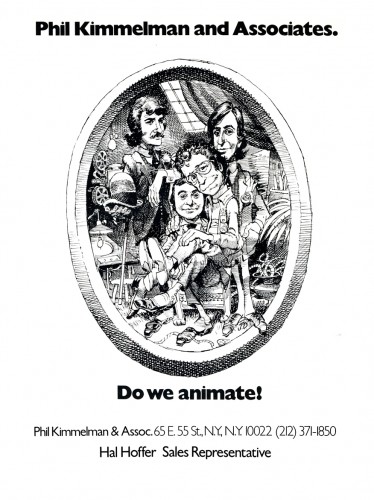

Phil Kimmelman’s studio, PK&A, was also a dominating advertiser.

Though their ads changed, as well, this one appeared often enough

to be recognizable.

Phil Kimmelman ran the studio with Bill Peckman supervising and

doing layout. Jack Schnerk, Sal Faillace and Dante Barbetta were

regularly used animators.

Perpetual Motion was another large studio run by Buzz Potamkin.

Their ads weren’t as obviously frequent as the other two, but

they did focus on their art.

Buzz ran the studio in NY with animators Vinnie Cafarelli and Jan Svochak

on staff. Candy Kugel was the up and coming star to emerge.

Bill Melendez, on the west coast, did the Charlie Brown shows, but

his studio also did commercials (often featuring Charlie Brown.)

Kurtz and Friends, in California, was hot.

Herb Stott’s Spungbuggy Works certainly caught my eye.

That name for a studio was genius.

Murakami Wolf, Swensen was a diverse animation studio that seemed to do everything from “The Point” to “Biker Mice From Mars” to commercials.

Mort and Millie Goldscholl ran the largest studio in Chicago, Goldscholl Ass.

Their focus seemed to be graphic animation.

IF Studio was run by cameraman, Carlos Sanchez. They filmed animation

and produced a lot of graphic animation.

Bajus Jones was a hip studio operating out of Minneapolis. They caught a lot of attention and did excellent character animation.

Ray Seti was an animator who opened his own one-man studio. He did a

lot of animatics for commercials and thrived for quite some time.

I have a funny story about meeting him that I’ll hold for another time.

George McGuinnes and Mark Howard ran The Image Factory. They did

dynamic graphic animation. I think I did the only drawn animation for

them – which they used for a graphic spot.

Articles on Animation &Bill Peckmann &Rowland B. Wilson 29 Nov 2008 09:46 am

Producers of 1976

- Last Tuesday I featured the Young Independent animators of 1977. Today let me showcase a couple of commercial producers from the same period. This article came from the famous Raggedy Ann issue of Millimeter/1976, edited by John Canemaker. It was part of their regular column:

PHIL KIMMELMAN

Phil Kimmelman is a New Yorker who stayed. “My love was always animation,” says the cherubic President and Director of Animation at Phil Kimmelman & Associates. At 17, he gave up a three-year scholarship to go to work for Paramount Famous. It was the 50′s; Hollywood was doing fine; budgets were big in the New York animation departments. “I’m delighted to have been a part of that. It really did a lot for me.”

Phil Kimmelman is a New Yorker who stayed. “My love was always animation,” says the cherubic President and Director of Animation at Phil Kimmelman & Associates. At 17, he gave up a three-year scholarship to go to work for Paramount Famous. It was the 50′s; Hollywood was doing fine; budgets were big in the New York animation departments. “I’m delighted to have been a part of that. It really did a lot for me.”

After gaining some experience at Kim-Gifford and Chad Studios in New Jersey, Phil served a stint in the army as an illustrator. In 1961, he joined Elektra as an animator and animation director. “Elektra was into experimenting. We were really into exploring new areas. I think that’s where it all began for me.”

After five years, Phil left Elektra for Focus. Four years later (1971), he opened his own shop. “Fortunately, I wasn’t enough of a businessman at the time to realize how bad things were. We staffed up rather heavily at a time when everybody was resorting to freelance … we got into some problems, but now we’re busier than ever.”

“I consider myself part of a team, the other part being Bill Peckman, one of my associates. We’ve been together through Elektra and Focus. I think Bill’s one of the best talents in this business . . . and I’m glad he’s with me.”

Phil’s other associates are Bill Hegman, designer, and Sid Horn, production manager. Morty Gerstein, a former competitor, is now affiliated as a designer/director. Working madly in the next room is Roland Wilson, a Playboy cartoonist beloved by ad folks for his New England Life campaign.

These gentlemen are just the tip of the iceberg. PK & A is crawling with creative types, and the company has recently leased additional space. “One of the things that has made us successful is the versatility of our reel. We’re great admirers of a lot of cartoonists and designers from outside. If a job comes through that we feel requires a certain look—like a Gahan Wilson or a Jack Davis—we’ll put our own egos aside and go after them. I’ll give you one example: Harvey Kurtzman. Harvey is the creator of Little Annie Fanny for Playboy. He’s best known, I guess, for starting Mad Magazine (he’s no longer with them). We’ve always been fans of Harvey Kurtzman—I think the man’s an absolute genius. Bill Peckman and I chased after him, and he was very apprehensive about working in animation. He said he had a bad experience at one time. But we got him to look at our reel, and at the end of it, he applauded and said he’d be willing to chance it again. So we had Harvey design and write some scripts for Sesame Street, which we’ve sold and produced, and we’ve won a lot of awards with them. They’re beautiful spots—and they’re one example of the ‘Kimmelman look.’ ”

Yes, but how does he work with agency art directors and writers? “When an agency board comes in, I like the option of taking the board and recreating it to our way of thinking. Generally, that’s why they come to us—for our input. I think a lot of art directors and writers are not really geared, you know, to think animation. When he or she gets involved in animation, there’s a long time period where there’s very little to do. You know, it’s difficult for the people in agencies who are making the schedules to understand the time element. Where we used to have a good eight weeks to do an average 30-second commercial, we’re constantly being asked to do it in four or five weeks. It’s what I see happening more and more today that kind of upsets me. We’re working nights—around the clock—too often. That’s what it’s become. I guess we love it enough to keep doing it. I do have a line I won’t go over. If I really feel it can’t be done, we won’t do it. I’ve been in that situation many times.”

What about Ralph Bakshi and his controversial coonskins? “Fantastic. Whether you or I like his films, there’s no question that they’re breakthroughs. He’s gotten animation into the adult mind. For that reason alone, I’m delighted it’s happening.

“I think it’s sad. So much more should be happening in this industry. I think animation still hasn’t been scratched. It’s an extension beyond what live can do. There’s no limit. There are people who think it’s a dying art. I don’t think it will ever die. I’m very optimistic about that. I think, if anything, it can only go upward.”

JERRY LIEBERMAN

Jerry Lieberman says he originally “wanted to be a doctor,” and he endured two years of pre-med before allowing all the “fantasy, other-world head aspects involved in growing up in corny, carny, show-biz pizzaz-zy Atlantic City” to take over. As a kid he “always drew” and worked three summers as a caricaturist on Atlantic City’s Million Dollar Pier.

Jerry Lieberman says he originally “wanted to be a doctor,” and he endured two years of pre-med before allowing all the “fantasy, other-world head aspects involved in growing up in corny, carny, show-biz pizzaz-zy Atlantic City” to take over. As a kid he “always drew” and worked three summers as a caricaturist on Atlantic City’s Million Dollar Pier.

He admired John Hubley’s Moonbird (1960) and Saul Bass’ titles and he constructed his own make-shift 16mm camera stand to “experiment with stop-motion, and even some professional work for WCAU-TV in Philadelphia doing promos for a local kids’ show.”

After studying design and graphics on a scholarship to the Philadelphia Museum’s School of Art, and a brief stint in the Army, Jerry came to New York City in 1964. “My first year in New York,” says Jerry today, “I made a storyboard six feet by ten feet long with 200 panels. It was my portfolio and it used to knock people over when I unfolded it.”

He managed to get work right away doing animated films for NBC-TV’s Exploring, “but I learned success doesn’t come easy. There were times when I walked the pavements going from one local production house to another for six months before getting work. One time my portfolio was so severely criticized by one potential employer, I stopped seeing people and had a phobia about work and my talent.

“I worked very hard; I paid my dues; eventually I made a lot of money in a short time and went to Europe. I thought foreign influences might be good for my work.” In London, Jerry met George Dunning who told him “the best place to go for work is Italy.” In Rome, Jerry was hired by American Harry Hess, a former UFA animator, and he worked for a year doing storyboards, design and animation for Italian commercials both in Rome and Milan. He even acted in a few live-action beer commercials.

Jerry returned to America with an excellent reel and his next big break was to be hired by Jack Zander at Pelican Productions as a designer. “Because animation does include every form of art, I wrote to Lee Strasberg and asked to join the Actor’s Studio Directors Unit, and I was accepted and studied there for two years. After a year at Pelican, he freelanced on educational films and was, for a short hilarious time, Phyllis Diller’s painting instructor.

“In 1968, Art Petricone, Howard Basis and I got together and started Ovation Films, Inc.,” says Jerry. “Howard and Art met at Kim and Gifford, and I had worked with Howard on a job. We started our business during the decline of the ‘Golden Years’ of TV commercial production, but we didn’t know that at the time. We had our reputations, things built up slowly, and in March of ’76 we’ll have been in business for eight years.”