Search ResultsFor "trnka"

Commentary 04 Feb 2012 07:04 am

Oddities and Endities

- Thanks to its Oscar nomination, Chico & Rita, the 2D Spanish, animated feature film will play in New York & Los Angeles. The distributor, G Kids, will bring the film to the Angelika Film Center starting Friday, February 10th for a week.

Directors Fernando Trueba & Javier Mariscal will be doing Q&A’s following the 7:40 PM shows Sat & Sun, Feb 11-12.

Angelika Film Center (18 W. Houston Street, 212-995-2570)

Friday, February 10, daily at 11:00, 1:10, 3:20, 5:30, and 7:40.

Screenings in Los Angeles will be Mon, Feb 6 at 2 PM (Linwood Dunn Theater), and Mon, Feb 13 at 9:20 PM (Samuel Goldwyn Theater). These are designated as Official Academy Screenings.

Annies Live

- The Annie Awards will take place tonight, Saturday, in Los Angeles starting at 7pm (Pacific Time) which is 10pm (Eastern). The awards will be available on line via streaming through a number of different sites. These include: Animation Guild site, Hans Perk’s A Film LA, Tee Bosustow’s Animazing site, and of course Cartoon Brew. If one has problems, go to the next.

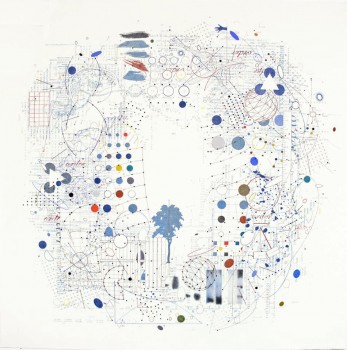

- The brilliant abstract animator, Paul Glabicki, is going to have an exhibition of his art March 15 to April 14th. I’d encourage you all to see this show; his work is always smart, exciting and worth the little effort it would take. He’s also an East coast animator and deserves our support. Here is the press release for the exhibition:

ORDER

- We are pleased to announce Paul Glabicki’s second solo exhibition at the Kim Foster Gallery. His new ORDER series explores expressions of “order†as image, concept, construct, and language – and the organization and potential ambiguity of information, communication, and language within complex and concurrent data systems.

Each drawing begins with an Internet search of the word “order.†Hundreds of images, interpretations, demonstrations, and associations are generated by each search, arranged in a hierarchy of relevance determined by the search engine. Each search becomes increasingly customized to the searcher, often branching off into intricate or obscure expressions of the word, its multiple meanings, or practice (specific arrangement, sequence, command, rank, importance, by discipline.) Each drawing is a selection and orchestration of these hierarchies of order systems and applications, filtered through the artist’s response to the information collected in each search.

Each drawing begins with an Internet search of the word “order.†Hundreds of images, interpretations, demonstrations, and associations are generated by each search, arranged in a hierarchy of relevance determined by the search engine. Each search becomes increasingly customized to the searcher, often branching off into intricate or obscure expressions of the word, its multiple meanings, or practice (specific arrangement, sequence, command, rank, importance, by discipline.) Each drawing is a selection and orchestration of these hierarchies of order systems and applications, filtered through the artist’s response to the information collected in each search.The process engages the artist’s own creative compulsion to organize and compose images. The first element of each drawing is deliberately placed at random, initiating a process of response, modification, and overlay. New imagery/data is added in a sequential chain, and in response to the placement of each previous element. Each drawing is rotated as new imagery and information is considered and assigned to the developing space; with its final viewing orientation established as the accumulated imagery satisfies the artist’s own personal impulse to impose “order†and closure – but only momentarily, until the process is carried on to the next piece.

Each drawing is a result of a chain of events, choices, and decisions generated by the initial, specific, finite fragment of data. The process plays with notions of causality, the desire/impulse to find, recognize or impose organization, response to (and interpretations of) vast sources of available data, and the complex interactions of image, language, communication and meaning in the representation of information.

- The work of Paul Glabicki continues to be involved with time and sequence, and an obsessive process of evolving images and complex compositions generated by an intimate examination of a finite word or found object.

All of the imagery in his work is drawn by hand (Graphite Pencil, Prismacolor Pencil, Ink, and Acrylic on Paper.)

- Paul Glabicki is best known for his experimental film animations that have appeared at major film festivals, as well as national and international museum exhibitions. His animation work in film has been carefully crafted by means of thousands of hand-drawn images on paper – each drawing representing both a frame of film and a unique complete work on paper. His film works have been widely screened at such prestigious sites as the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center, the Cannes Film Festival, the Museum of Modern Art and Whitney Museum of Art in New York (Whitney Biennial), and the Venice Biennale. He has received numerous awards, grants, and fellowships, including a Guggenheim Fellowship, grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, the American Film Institute, and several grants from the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts.

KIM FOSTER GALLERY

529 West 20th New York, NY 10011 212-229-0044

www.kimfostergallery.com

info@kimfostergallery.com

- Paul Glabicki

ORDER

March 15 – April 14, 2012

( Tuesday – Saturday, 11 am to 6 pm)

Reception: Thursday, March 15, 6 to 8 pm

Just prior to the opening, I’ll remind you of the dates.

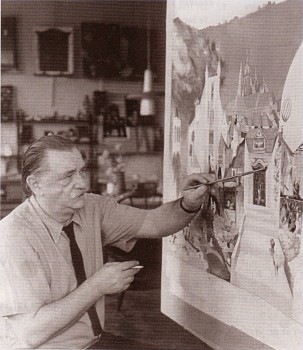

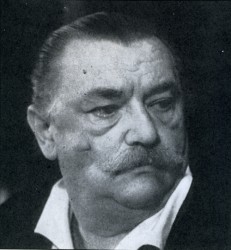

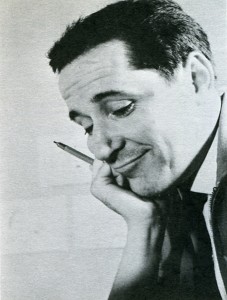

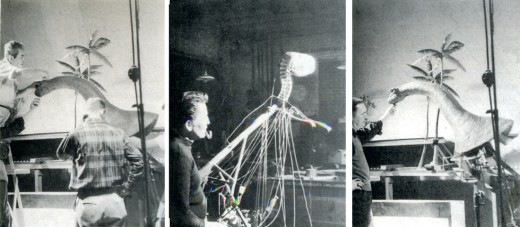

- Gene Deitch has hit another home run on his blog this week. He posts a piece about the great puppet animator and artist, Jiřà Trnka. Deitch tells intimate stories that make me feel closer to the man, Trnka, than I’ve gotten from many other books about the master’s work. (Just look at the image to the left from Deitch’s site. We see not only that Trnka was left handed, but that he couldn’t stop smoking even in the middle of painting during a photo shoot!) We learn about an aborted collaboration between Deitch and Trnka and several of the drawings Trnka did are posted on the site.

- Gene Deitch has hit another home run on his blog this week. He posts a piece about the great puppet animator and artist, Jiřà Trnka. Deitch tells intimate stories that make me feel closer to the man, Trnka, than I’ve gotten from many other books about the master’s work. (Just look at the image to the left from Deitch’s site. We see not only that Trnka was left handed, but that he couldn’t stop smoking even in the middle of painting during a photo shoot!) We learn about an aborted collaboration between Deitch and Trnka and several of the drawings Trnka did are posted on the site.

Deitch also gives us a good report with photos on the recent memorial in Prague celebrating the 100th anniversary of Trnka’s birth. This is a fabulous read.

Of course, there are many other articles equally as good on this site. Another recent post is on the artist, Jiřà BrdeÄka. He was just as great a force, in many ways, as was Trnka. This is a wonderful site and should be regularly followed.

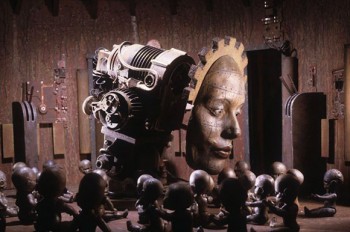

Robot Puppet Porn

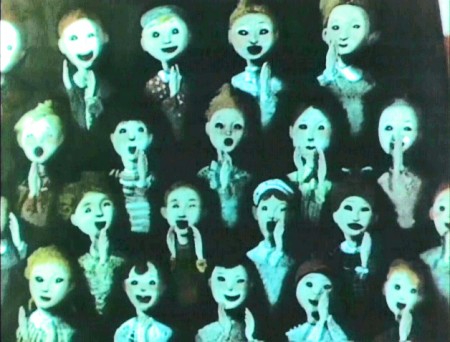

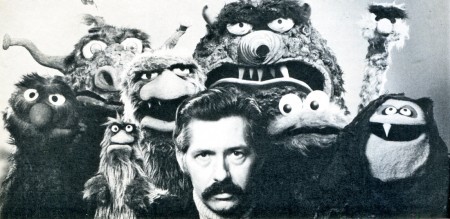

- Michael Sullivan is a New York animator/effects wizard/actor/artist who gets little attention.

- Michael Sullivan is a New York animator/effects wizard/actor/artist who gets little attention.

He’s amassed years worth of puppets, dolls and small artifacts which he develops into his characters for the eccentric films he produces. Currently, he’s been making a film about robots – actually, a pornographic film about robots. This has been chronicled into a short film documentary that ran at the recently completed Sundance Film Festival. Titled, The Meaning of Robots, the doc is by filmmaker, Matt Lenski. There’s a trailer for the doc here and articles about the film here and here.

Watch part of Michael Sullivan’s work here.

Thanks to Tom Hachtman for the good word..

- Finally, the news that Don Cornelius had died this week, as a result of suicide, made me want to take another look at the opening title animation to Soul Train. There are no good quality copies on YouTube, but I found this small sampling of the show and felt that something was better than nothing. The titles were produced by Jim Simon with his company, Wantu Animation. I think I remember Dan Haskett telling me that he had done some animation on it. He did do a lot of work for Jim Simon, so it’s likely. Regardless, the titles are worth a nod. I haven’t seen any other animation site point it out.

Jim Simon/Wantu Animation for Don Cornelius Productions

repeated posts &Trnka 21 Nov 2011 07:42 am

Trnka’s Merry Circus – repost

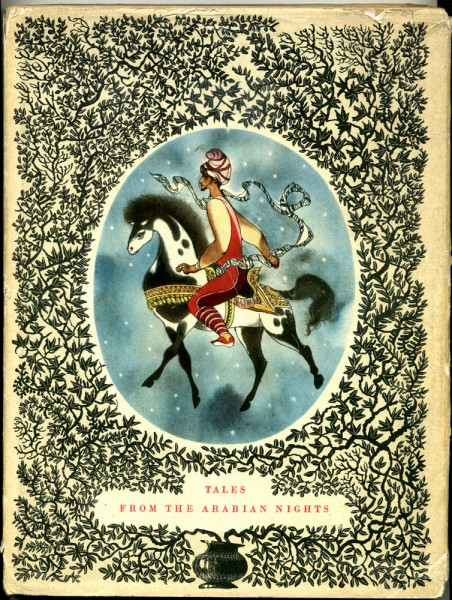

– I’ve been a fan of Jirà Trnka‘s work since I first saw it back in the 60′s. I’ve bought every publication I’ve ever found which discusses or displays his films or illustration. These days I can also own a number of his films.

– I’ve been a fan of Jirà Trnka‘s work since I first saw it back in the 60′s. I’ve bought every publication I’ve ever found which discusses or displays his films or illustration. These days I can also own a number of his films.

His puppet films were always the gold standard of that medium. However, since I’ve studied his illustrations for many years, I’m always interested in the 2D work he’s done.

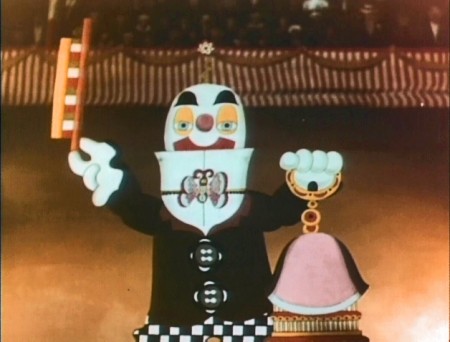

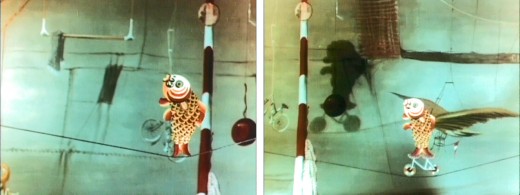

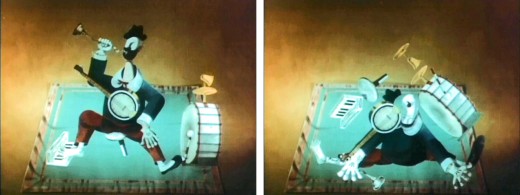

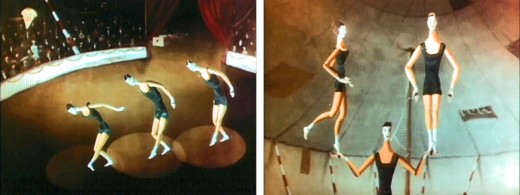

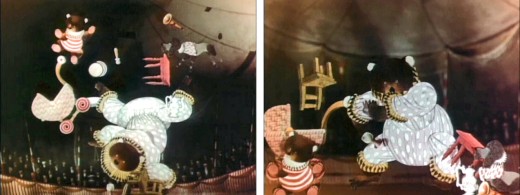

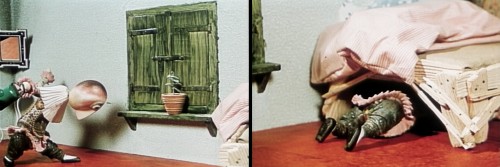

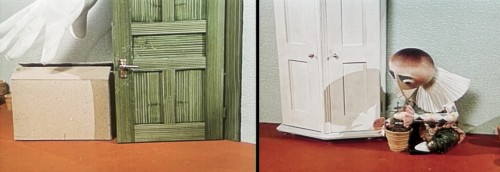

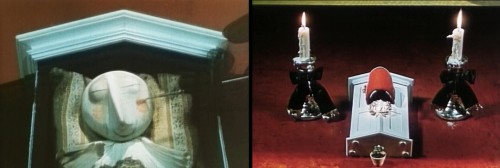

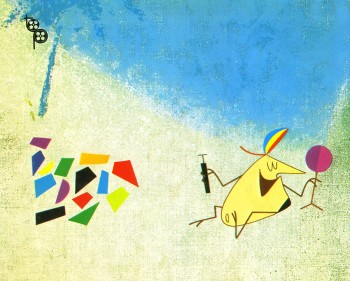

The dvd titled The Puppet Films of Jirà Trnka includes one of these 2D films. It’s cut-out animation, so it really borders the world between 2D and 3D. Trnka exploits the shadows on his constructed cardboard backgrounds to great effect. The style purposefully hides the three dimensions of the constructions, but it uses it when it needs to. The film is a delicate piece which just shows a number of acts in a local circus setting.

It’s a sweet film with a quiet pace. I’m not sure it could be done in today’s world of snap and speed. No one seems to want to take time to enjoy quiet works of art.

I’m posting a number of frame grabs from this short so as to highlight the piece.

Note the real shadows on the background.

These were obviously animated on glass levels in a multiplane setup.

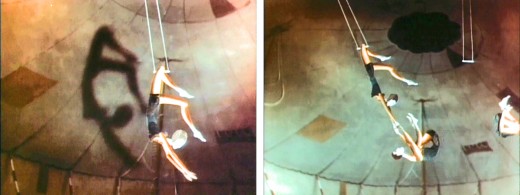

Again, note the excellent use of shadows. It’s very

effective in these long shots of the trapeze artists.

Animation &Frame Grabs &Trnka 03 Jan 2011 08:20 am

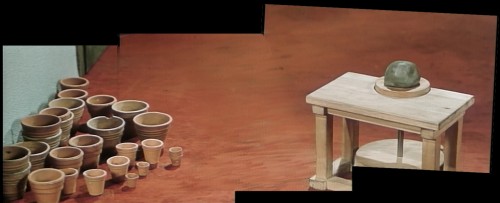

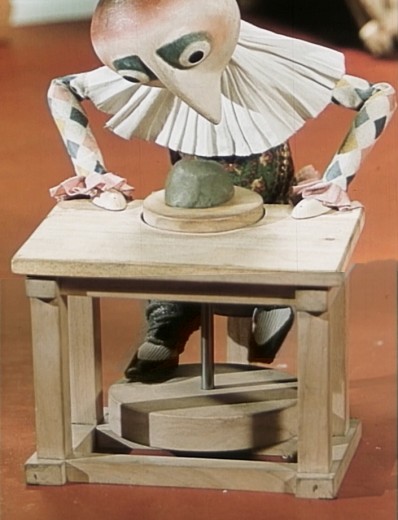

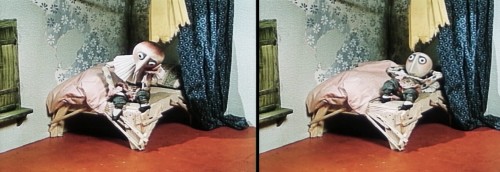

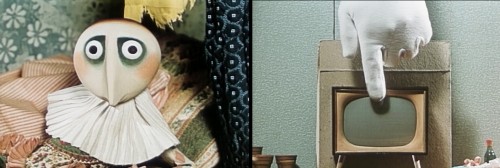

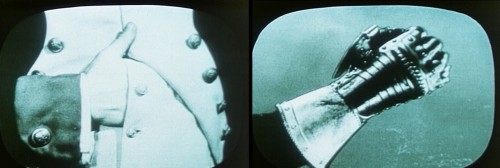

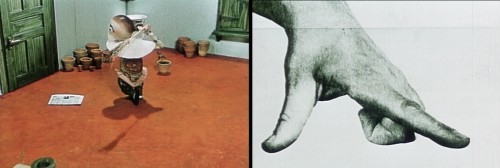

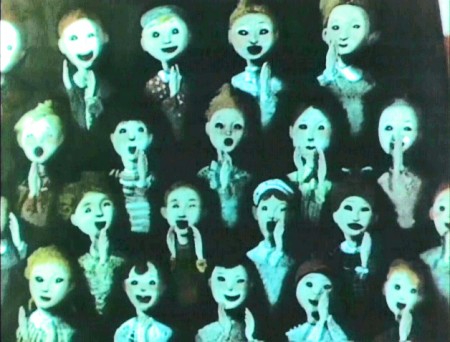

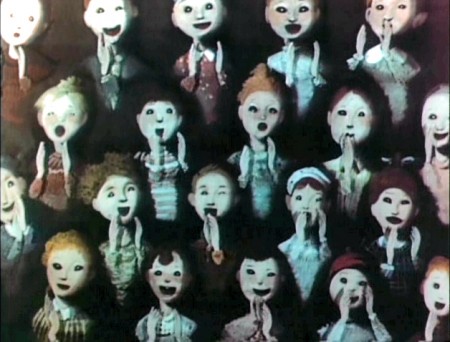

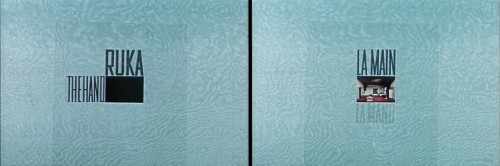

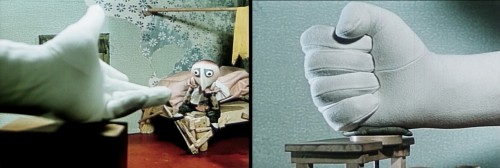

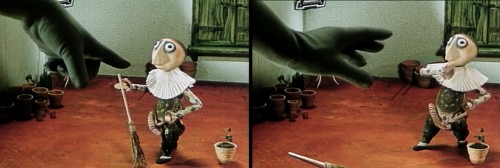

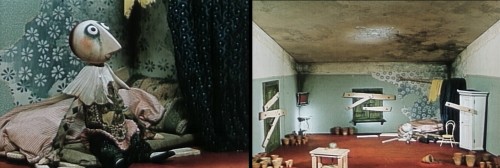

The Hand

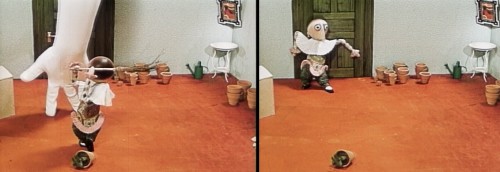

- I decided this week, I wouldn’t go to a Disney cartoon to give a frame grab display. Instead, I’ve chosen to showcase images from Jiri Trnka‘s brilliant film, THE HAND. This is an anti-totalitarian film done from behind the Iron Curtain when it was forbidden for him to do so. There, presumably, were consequences (though I don’t know any specifics.)

1

1The film’s title plays in four different languages.

2

2

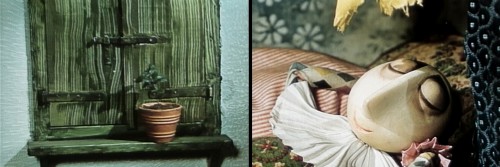

We see inside the sculpter’s house. LS to . . .

3

3

. . . closer shot of him in bed.

5

5

One plant in a pot in the window.

6

6

He gets up, exercises and . . .

9

9

He says a formal good morning to his plant.

12

12

A loud knock – is it the door?

14

14

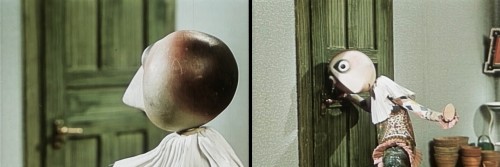

A giant hand bursts through the window knocking the plant to the ground.

15

15

The potter goes through the same formality of bowing, good morning, to the hand.

16

16

The hand tells the potter he wants a commissioned statue of himself.

17

17

The potter says “NO” many times.

18

18

Even rushing to get back to creating a new pot.

19

19

Then he pushes the hand out of the shop . . .

20

20

. . . and he attends to the damaged plant.

21

21

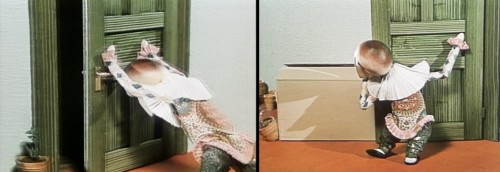

The hand is back again and the potter tries to keep him out.

22

22

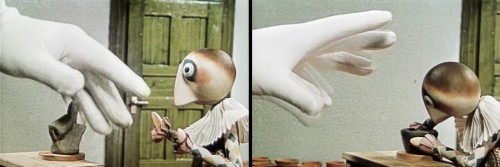

The hand pushes in a cardboard box.

23

23

The hand bursts out and impatiently demands a statue of himself.

The potter pulls out a broom.

24

24

He uses the broom to push the hand out the door.

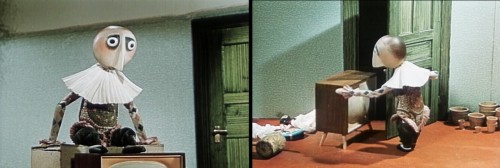

25

25

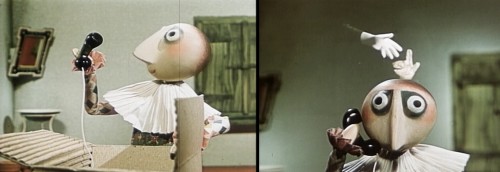

A phone rings in the crardboard box, and the potter answers it.

The phone demands the statue . . .

26

26

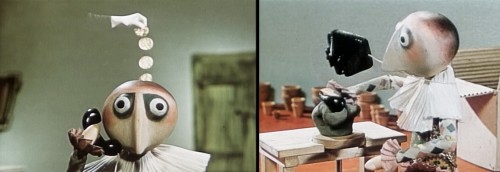

. . . and offers lots of money.

The potter throws the phone away.

28

28

He dreams of flowers until he’s awakened.

31

31

We see many examples of great hands in history.

33

33

Again the hand implores and then demands the statue.

34

34

The sculptor drags a heavy mallet out from under the bed.

35

35

He swings it at the hand to get rid of him.

36

36

The hand goes into the box.

37

37

The sculptor pushes the box and the tv out the door.

39

39

In no time the hand is back . . . demanding.

40

40

The sculptor stands resistant.

41

41

He’s pushed back into a corner.

42

42

The hand grabs him by the head.

43

43

And he is dragged to the potter’s wheel.

45

45

He makes a marionette of the potter.

46

46

The potter’s encaged and forced to sculpt the statue.

48

48

He’s forced to work endless days and nights sculpting.

49

49

Until, finally, the statue is completed.

50

50

The sculptor uses the statue to crash through the bars of the cage.

51

51

He jumps free of the bondage of the “State.”

52

52

Eventually, damaged, he makes his way back home.

53

53

He boards up the door and window.

54

54

He cares for the hurt plant.

55

55

And places it in a secure spot out of reach.

56

56

The sculptor is haunted by the sound of the hand.

He dies.

57

57

The hand enters, places him in a casket he makes of the cabinet.

(Thus destroying the plant.)

Books &Independent Animation 02 Nov 2010 07:25 am

Just Published

The NYTimes features a longish article about Sylvain Chomet’s film, The Illusionist. It appeared in Sunday’s paper.

Likewise, the NYTimes also has an article about Megamind. It’s essentially a photo essay.

- George Griffin sent me a couple of links: one to an article at ArtForum Magazine about the scupture of animation artist Robert Breer; it’s a good read. Take a look here.

There’s also a spot called “Dot” from Aardman Animation that’s worth viewing at YouTube. Here It reveals what went in to making the world’s smallest character animated film and how it was shot using a Nokia N8.

Book Review

- David Levy has fashioned an exceptional career for himself. He’s been producing animated shorts, teaching at the School of Visual Arts, and writing books. It’s the latter career choice that I’m interested in, today. Dave’s got a new book hitting the market today, and I’d like to talk about it.

- David Levy has fashioned an exceptional career for himself. He’s been producing animated shorts, teaching at the School of Visual Arts, and writing books. It’s the latter career choice that I’m interested in, today. Dave’s got a new book hitting the market today, and I’d like to talk about it.

Directing Animation is published by Allworth Press, and it’s his third book and a good companion to the other two: the first, Your Career in Animation: How to Survive and Thrive and the follow up, Animation Development: From Pitch to Production.

David is concerned with the nuts and bolts of animation. He wants to reveal how things work. In the first book, Your Career in Animation: How to Survive and Thrive, he focussed on how the individual should work in an animation studio. It was something that hadn’t been touched on before: proper manners and activities within a studio environment; essentially, how to work with others. The second book, Animation Development: From Pitch to Production spoke to those were trying to develop a series for television and how to present it to those in the position of power. It perfectly, again, taught the proper protocol for delivering your message and selling yourself. Neither of these books, really, had any predecessor.

This third book, Directing Animation, is also something original. It talks about the person who controls a film. There are many book on live-action directing, none that I know of – except this one – for animation. David spends much of his time talking to professionals and gives a guide to working within a group, a studio structure. He also spends plenty of space talking about the Independent animation Director.

I’m mentioned quite a bit in the book, as is Bill Plympton (who did the cover art for the book.) We’re the old timers, it would seem, and a lot of other younger directors such as David Palmer, Tatia Rosenthal and Ian Jones-Quartey get plenty of coverage. Even Web Directors, such as Xeth Feinberg, are discussed.

I’m sorry there isn’t time spent discussing the history of animation direction with some of the past geniuses who set the way: Chuck Jones, John Hubley, Bob Clampett, Jiri Trnka and the many others with strong personalities. It would be nice to see what made those people strong directors and how we can learn from their films.

The book gives more of an overview than an actual how-to approach to the subject. Unlike a book on how to direct a live-action film, there’s little talk of the language of film; no mention of such things as: “the inadvisability of cutting from LS to CU or back”, “the complications of shooting a pull back – zoom out” or even “crossing the 180°”. No, this book is more about getting the job and what’s expected of you. However, using a lot of anecdotes and answers to questions from the directors chosen, a lot is revealed. The subject takes us from TV series to animated features to web productions. A lot to cover, and it does it gracefully.

The book is a good companion to those questioning the career choice. However, it takes a lot of experience to do it properly. The knowledge of film structure and live action history has a lot to do with properly directing a film – even an animated film. Hitchcock once said that there’s only ONE possible setup for a scene, and you had to find that setup. In animation we usually jump from one hyper dynamic pose to another; it’s not film language but comic book language. A book can only tell you so much; the experience will reveal much more.

I’d say that if you want to direct, you should make a film – by yourself, if necessary. You’ll learn a lot of mistakes to avoid for the future and get your directing career going.

The book’s a great read, as are all of David’s works. I’m looking forward to his upcoming book about Bill Plympton. This is something different for David, and I’m curious to see how he’ll approach it.

_____________________

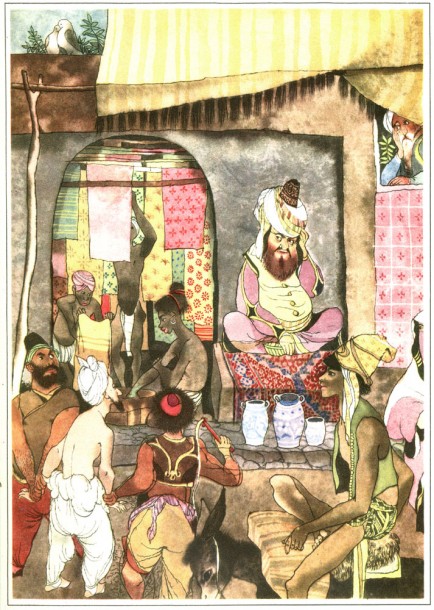

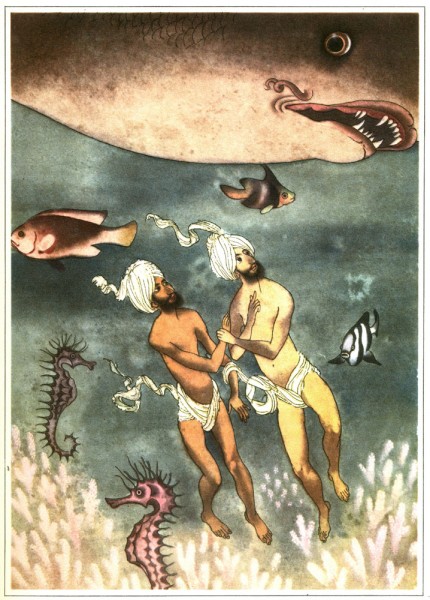

Animation &Puppet Animation 28 Aug 2010 07:45 am

Kihachiro Kawamoto

- This last week saw the death of two Japanese animation masters. The very young (46) 2D director, Satoshi Kon, died of pancreatic cancer on Tuesday.

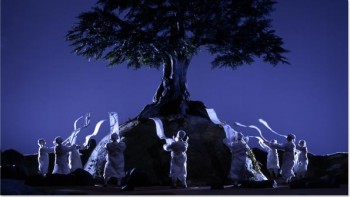

Then we learned that the brilliant puppet animator, Kihachiro Kawamoto had died on Monday. (Cartoon Brew has an excellent obituary for him.)

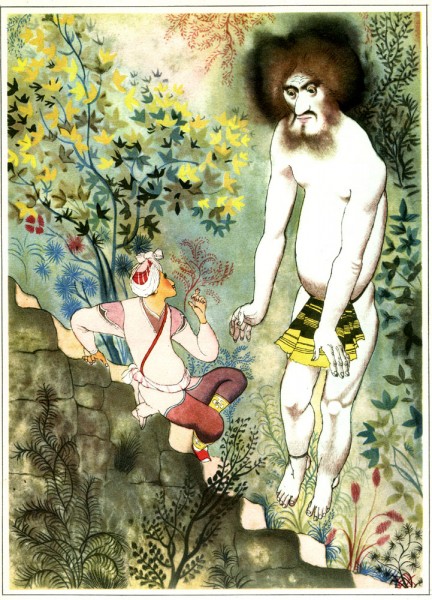

He was an acolyte of Jiri Trnka‘s, having travelled to Czechoslovakia to work with the great puppet filmmaker. Kawamoto’s own short films were gem-like little jewels which often told harrowing Japanese folk tales. Films such as The Demon (1972), Dojoji Temple (1976) and House of Flame (1979) are pure film yet they retain the spirituality of old Japanese mysticism.

He was an acolyte of Jiri Trnka‘s, having travelled to Czechoslovakia to work with the great puppet filmmaker. Kawamoto’s own short films were gem-like little jewels which often told harrowing Japanese folk tales. Films such as The Demon (1972), Dojoji Temple (1976) and House of Flame (1979) are pure film yet they retain the spirituality of old Japanese mysticism.

Aside from the numerous beautiful short films he animated and directed, he did two features: The Book of the Dead and Rennyo and His Mother. He also supervised the cut out feature, Winter Days, a film inspired by the renka couplets of celebrated haiku poet Matsuo Basho. 35 of the world’s top animators created two-minute segments for the film. The most popular of these was Yuri Norstein

Aside from the numerous beautiful short films he animated and directed, he did two features: The Book of the Dead and Rennyo and His Mother. He also supervised the cut out feature, Winter Days, a film inspired by the renka couplets of celebrated haiku poet Matsuo Basho. 35 of the world’s top animators created two-minute segments for the film. The most popular of these was Yuri Norstein

Again I saw him in Ottawa in 2006 at an animation festival. His feature, The Book of the Dead, was being screened. He spoke to an audience at a Q&A for the filmmakers. It wasn’t quite the same feel meeting him this time, but it was more relaxed and a treat, all the same.

Again I saw him in Ottawa in 2006 at an animation festival. His feature, The Book of the Dead, was being screened. He spoke to an audience at a Q&A for the filmmakers. It wasn’t quite the same feel meeting him this time, but it was more relaxed and a treat, all the same.

He died of complications from pneumonia on Monday, August 23 at the age of 85. He was a brilliant puppet filmmaker – one of the very best.

Articles on Animation 01 Jul 2010 08:02 am

Commercials History

- Earlier this week, I’d posted an excellent piece by Mike Barrier on the work of the Hubleys. This article was taken from a 1977 Millimeter Magazine animation issue. In that same issue, is an article about the history of the TV commercial. There’s a lot of good information in the piece and the shortened history of a lot of important studios that many of you are unfamiliar with. Unfortunately, it also mentions a lot of ads you may not be familiar with. But there’s plenty there in the packed piece. So I thought it a good idea to put this info out there.

Here’s the piece by Arthur Ross.

A Retrospective View

by Arthur Ross

ANIMATE, according to the time-honored Webster’s definition, means “to give natural life to; to give spirit to; to stimulate; to rouse; to prompt; to impart an appearance of life, as to animate a cartoon.”

And that is exactly what animated TV commercials have been doing for the past 30 years. They have given life, spirit, and verve to the selling of thousands of products both in America and abroad.

Psychologically speaking, they work by expanding the fixed limits of reality, by creating new and exciting worlds of fun and fantasy, and by captivating the viewer with fresh perspectives that reinforce our basic drives and motivations for love, success, beauty, comfort, and self-esteem.

During the course of a single 60 second spot, we see 1,440 individual pictures, or frames, come to life! Often with the kind of humor, or whimsy, or charm that speaks to our unguarded and childlike selves, and in some instances, even to the deepest recesses of our unconscious.

That is precisely why they are so potent a sales tool for industry, an educational device for schools, and an entertainment vehicle unto themselves. They work by playfulness, destroying all logical opposition to the messages they may contain.

They dazzle our senses and charm us into belief. Or, at least, they help suspend our disbelief in the ideas they put forth. They are 20th century dreams — dreams that money can buy!

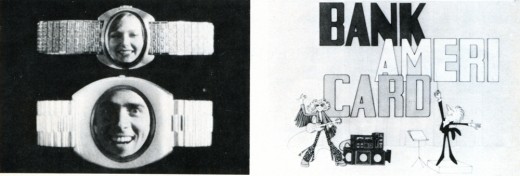

1. Object Animation: Speidel’s “Faces In The Watches”

created by John Gati of Action Pictures.

2. West Coast animation: Bank Americard (FilmFair) 1961-1976

While they operate on our most primative emotional level, animated commercials are highly sophisticated forms of art — employing words, graphics, color, motion, sound, music and symbols to activate the sale of goods and services.

Some of America’s foremost art talent has worked in the field at one time or another, including Saul Steinberg, John Hubley, William Steig, Saul Bass, to name a few.

The earliest animation in the forties was generally quite conventional — literally cartoon commercials of the straight Disney school of animation. It was essentially an extension of theatrical animation such as characterized the products of Warner Brothers, Paramount, MGM, and Disney at the time. Its novelty was successful and proved animated characters could sell products as well as live spokespeople. Everything was executed in glorious black and white, since color on TV was still years away. Commercial studios began to emerge in the late ’40s and early ’50s to supply the demand for animated spots — among them Academy Pictures, Shamus Culhane, Bill Sturm Studios, Film Graphics turning out such early “hall of famers” as the Ajax “Down the Drain” Bubbles and Mott’s “Singing Apples”.

In the early “50s a new trend entered TV commercials when UPA, creators of Gerald McBoing-Boing for theaters, introduced its unique avant-garde style of animation breaking away from the more conventional school of Disney design and execution.

We had the pleasure in the early ’50s of working personally1 with ex-UPA star John Hubley on some of the most successful of these avant-garde spots, including those for Speedway 79 gasoline, Altes Golden Lager Beer and Faygo Beverages (for the W.B. Doner agency in Detroit) as well as Chevrolet (for Campbell-Ewald, again in Detroit.) Other notable avant-garde entries during this period included the famous Saul Steinberg Jello “Busy Day” spot, as well as the classic Bert and Harry Piels spots (for Young and Rubicam).

Continuing through the mid ’50s, two trend-setting studios emerged when John Hubley formed Storyboard Inc. and Abe Liss joined forces with Sam Magdoff to start Elektra Films. Hubley continued his classic style with such winners as Heinz Worcestershire Sauce’s “Tongue-tied Spokesman”, Ford “It’s a Ford” series, and Maypo’s “I Want My Maypo” commercial. Elektra came forth with highly experimental works, creating new breakthroughs in photo-animation, multiple image and optical effects, and totally fresh avenues of design. During this time Elektra spawned such outstanding animation and graphics talents as Jack Goodford, Pable Ferro, Cliff Roberts, the Canattas, Lee Savage, Phil Kimmelman, and Hal Silvermintz, as well as Arnie Levin, Howard Beckerman, and Mordi Gerstein. Among the outstanding Elektra efforts of this era were the NBC Peacock, the legendary “Talking Stomachs” Alka Seltzer spot designed by R.O. Blechman, as well as award-winners for Chevron, Esso, Chevrolet, and Alcoa. One notable achievement, I fondly recall, was a 60-second spot done for the United States Army “Great Moments” series (which I had the pleasure of writing and producing) in which Elektra’s people (including the late Len Appleson) recreated the entire Louis-Schmelling Championship fight with stills quick-cut to the rapid beat of music and crowd cheers. It was a montage breakthrough that Sergei Eisenstein would have been proud of.

Following the success of Storyboard, Inc. and Elektra, more top studies and talent emerged in commercial animation. Pelican films emerged under the able leadership of Jack Zander and did notable work for American Motors, Volvo (designed by Mordi Gerstein) and Alka Seltzer (“The Blahs” designed by cartoonist Willilam Steig.)

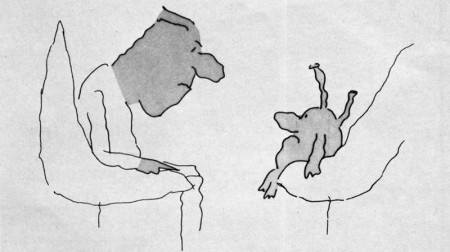

Use of famous cartoonists and illustrators in TV Commercials:

Still from a commercial made in the 60s by Elektra Productions,

utilizing cartoonist Bill Steig.

Other fine studios of the fifties were those begun by Lars Calonius, Transfilm, Kim-Gifford, Robert Lawrence and Ernest Pintoff — the latter going on to win an Academy Award for “The Critic” some years later. Arnold Stone was a heavy contributor in those years to the Pintoff output, which included excellent animated spots for Proctor-Silex appliances, Yoo-Hoo Chocolate Drink, and The Bell Telephone Company.

These proved to be the “golden years” for commercial animation with many studios maintaining large staffs to cover the growing need for their excellent product. At one point, there was even a shortage of talent available to handle the work load and one had to “wait on line” for delivery.

In the ’60s, the trend increased towards graphics and we saw a sharp decline in traditional animation. New techniques were perfected — like the super quick cuts of Elektra and Ferro, Mogubgub and Schwartz. The latter also held the industry in marvelous disbelief at its outrageously “insane comic inventions” such as the award-winning “Crazy Hat” commercial for County Fair Bread (which we had the pleasure of producing with them).

Continuing the trend to more limited animation, which UPA orginated as an economical move to cope with the high cost of full animation, studios in the ’60s experimented with photomatics, “squeeze”, semi-abstracts, paper sculpture, and technique of combining live photos with animated bodies (perfected by Paul Kim of Kim-Gifford in a prize winner for the National Safety Council on preventing highway accidents.) Tighter budgets, a declining economy, and a swing away from animation to greater use of realism created massive layoffs in the commercial animation field in the late ’60s and early ’70s — and many good, long-established shops passed from the scene. Smaller one and two-man companies emerged to take their place and this trend continues up to the present day.

It should be pointed out that throughout the ’50s and into the ’60s traditional animation continued as a popular communications tool for many agencies and companies. Outstanding among these was William Tytla Associates. The late Bill Tytla was one of the foremost Disney animators, contributing greatly to the success of such Disney immortals as FANTASIA, PINOCCHIO, SNOW WHITE and DUMBO. In the ’50s, Bill took his talents into the commercial arena and did some outstanding work in the more conventional animation forms. We had the pleasure of working with him in the animation development of the worldwide symbol for Esso, “Happy the Oil Drop,” a fantasy figure that Bill brought to wondrous “life” through his skills as an animation director.

Simplicity of design in 50s & 60s; Still frame from the famous Blechman

“Talking Stomach” Alka Seltzer commercial produced by Elektra in the 60s.

In spite of downtrends in the economy, the late ’60s and early ’70s saw a brilliant new bursting forth of creative energy in animation influenced by Peter Max and the worldwide success of “The Yellow Submarine.”

Among the many fine companies that emerged were Focus Productions, which turned out such award-winners as Vote Toothpaste “Dragon Mouth,” designed by Rowland Wilson; Gillette’s “Moveable Features,” designed by Tomi Ungerer, and the Utica Club Beer series designed by Jack Davis and Mort Drucker. In 1972, Phil Kimmelman left Focus to open his own shop, Phil Kimmelman & Associates. Here, along with Bill Peckman, he has turned out some outstanding efforts including the Cheetos Mouse campaign, the Exxon Tiger, and the delicately sensuous Clairol Herbal Essence commercial.

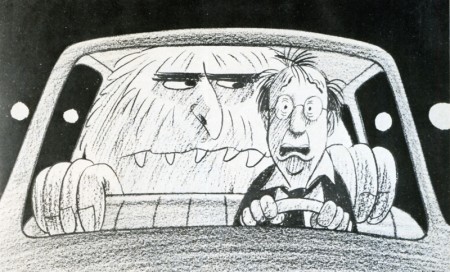

Horror Fantasy in TV commercial animation (1976): Avis Rent-A-Car;

Designer/Director: Mordi Gerstein; Producer Phil Kimmelman & Associates.

Other exciting breakthroughs in the ’70s include the highly graphic look of computer animation, perfected by such companies as Dolphin Productions for use as station and program attractions; rotoscope animation brought to brilliant maturity by Ovation Films in New York and Snazelle Films on the West Coast. The Levi campaign is an outstanding example of rotoscope animation, bringing a fresh new excitement to the field.

On the West Coast, throughout the ’50s and ’60s animation led by UP A, and Storyboard, Inc., continued to expand along with the fine efforts of such companies as TV Spots for Johnson’s Wax, Lucky Lager Beer and L&M Cigarettes; John Sutherland Productions (“A 1580 Atom”); Playhouse Pictures (Ford, Falstaff Beer, H.J. Heinz) Quartet Films (Western Airlines); Animation, Inc. for Oscar Mayer, Soho Boron Gasoline and Pabst Blue Ribbon Beer; and Five Star Productions whose animation department headed by Howard Swift (another ex-Disney man) created some of the earlier TV and cinema commercials for Ford, Pabst, F.T.D., Coca-Cola, as well as bringing Speedy Alka-Seltzer to “life” via the George Pal puppet-type stop motion use of a series of replaceable heads. Interestingly, after a decade of experimenting with other creative directions, Alka Seltzer has just reverted back to using “Speedy” again in its current advertising.

It is an outstanding example of how things come creatively full-circle and how each generation rediscovers the “great ideas” of the past.

Joop Geesink continued to perfect the puppet type animation throughout the fifties, working in Holland for American companies through Transfilm in the United States. His “Brewster, the Goebel Rooster” and Heinz Aristocrat Tomato were two fine creations in this genre.

The use of “stylized” animation-type settings in which live action unfolds was another outgrowth of animation in the late ’50s. S. Rollins Guild whom we had the pleasure of working with at McCann-Erickson in the ’60s contributed greatly to the perfection of this commercial art form for such companies as Nabisco and Coca-Cola. Both series were produced by Bill Sturm Productions in New York.

Black-Lite, while basically a live photographic technique, creates a unique “animation” look to commercials. We had the opportunity of creating and producing the first such black-lite commercial in 1955 for Flagg Brothers Shoes (“Dancing Shoes”) which won numerous Art Director Club Awards for originality and effectiveness. The producing company was Sundial Films, headed by the multi-talented Sam Datlowe. It marked the first commercial assignment for young and talented Jerry Hirshfeld, who later became the ace of the MPO Productions staff, before turning to feature films.

One of the continuing trends in animation today, largely aided by Elektra and Jack Zander in the ’50s, is the use of well-known cartoonists and illustrators from outside the industry. Among the best are Bill Steig, Frank Modell, Charles Saxon, Seymour Chwast, Milton Glaser, and Peter Max, all contributing greatly to the resurgence of animation in the “70s.

Other outstanding work in animated commercials was achieved on the West Coast by Ray Patin, whose chief animator (another Disney graduate) was Gus Jekel, now the head of Film Fair, Inc. They accomplished some fine efforts for Y&R on Jello in the early ’50s through Jack Sidebotham, one of the really great art directors in the advertising field. These include such classics as “Banana-ana,” and “Chinese Baby.” Ray Patin also turned out the NY AD gold medal Bardahl series, aping Dragnet, as well as noteworthy campaigns for National Bohemian Beer and Jax Beer.

In passing, one must not forget to include in the pantheon of animation producers such fine organizations as Cascade Productions, Playhouse Pictures, Quartet, Imagination, Inc. all of whom executed award-winning series in the ’50s and ’60s.

In the ’60s, Gus Jekel’s Film Fair did noteworthy series for BankAmericard and Bardahl which won the Cannes and Venice Awards. Today, Film Fair does exceptional work with continuing characters, such as Peter Pan (Peanut Butter). Charlie Tuna, Tony Tiger, and the Snap, Crackle and Pop trio for Kellogg’s Like Elektra in the East, Film Fair nurtured a great deal of the best West Coast talent including Art Babbitt, Bob Cannon, Dick Van Benthem, Ken Walker, Fred Wolf, Norm Gottfredson, Ken Champin, and Corny Cole. It is one of the reasons the West Coast continues to do such exciting creative work in the field along with its East Coast counterparts.

One of the long-standing successful animation partnerships in the East has been Paul Kim and Lew Gifford, doing fine work in the field since 1958. Among their top creative efforts are award-winners for Piels Brothers, and the Emily Tipp series. Their Modess a delicate subject with taste, simplicity, and artistry. And their famous Winston “Montage” introduced a 14 way split screen in constant movement to the Winston jingle — breaking exciting new ground in the use of matte work and animation design.

Another top West Coaster is veteran animator Herbert Klynn, President of Format Productions. Herb served 16 years as designer and then Executive Production Manager for UPA, before organizing his own animation company. His Format Productions is active in entertainment series such as the Alvin Shows, the Lone Ranger and Popeye programs, as well as creating titles for such TV shows as I Spy, Smothers Brothers, and The Mothers-In-Law. Among his fine animated TV commercials are those for Max Factor, Post Cereals, Wells Fargo Bank, and Dreyfus Investments. During his tenure with UPA, Herb worked on such classic film cartoon short subjects as “Madeline,” “Mister Magoo,” and “Gerald McBoing-Boing.” Our own particular favorite is his treatment of Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart” for UPA.

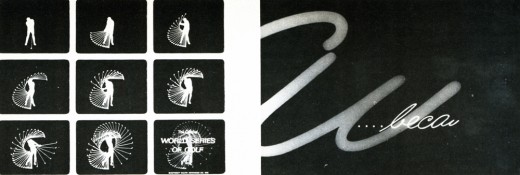

1. Graphic animation of a “strobe” like image of a golfer, made with 90 kodalith negatives

in registration. (World Series of Golf” Show opening by Goldsholl Associates.

2. The Unspoken Spoken Message: Modess “Because” (1962) Kim & Gifford Productions

Some fine animation has come out of the Midwest, too, in recent years. A key contributer from that area is Goldsholl Associates, an Illinois-based house that has brought fresh innovative graphics and experimental style to animated TV spots. In such commercials as 7-UP’s Sugar-Free “Carton Graphics” they infuse “life” into abstract dots to create a rich new imagery on screen. Colors, shapes, and textures all impart a “meaning” experi-entally to the message.

One of the more prolific of New York’s animators is Jack Zander. He began his career in 1946 at Willard Pictures doing an animated Chiclets commercial in which he animated Chiclets’ boxes like a choo-choo train to a music track taken off a 78 rpm radio transcription. In 1948, he started up the animation department at Transfilm, where he created the first animated Camel Cigarette commercials and helped develop the paper “cut-out” technique. In 1954 he and Joe Dunford opened Pelican Films and did successful commercials for over 16 years, along with Mordi Gerstein, Lars Colonius, Paul Harvey, Wayne Becher and Dino Kata-polis. During this period, Jack utilized the service of several wellknown cartoonists, including Charles Saxon for American Airlines, and later Bill Steig and George Price of “New Yorker” fame. It was also during this period that Jack did the famous Nichols and May “Jax Beer” animated series, as well as some of the early Bert and Harry Piels spots.

In 1970, Jack moved across the street and launched Zander’s Animation Parlor with his son Mark. He has created his share of “hits” in recent years, too, including the exceptionally fine Freakies campaign, beautifully animated by Preston Blair.

Another fine New York animation talent is Art Petricone who today heads up Ovation Films. In addition to his fine work for Eastern Airlines, his brilliant use of rotoscope can be seen in his work for Levi Strauss and Clairol Herbalessence.

In the area of object and figure animation and stop motion, John Gati, the Director of Special Effects, for Action Pictures in New York is unsurpassed. John has been working at his craft for 26 years and has won many awards for technique and innovation.

The art of Object and Figure Animation requires enormous craftsmanship. Basically, it resembles conventional (drawn) animation in that it follows the rule of “creating the movement” by the process of frame by frame photography. But as opposed to eel animation, which occurs on a two dimensional (acetate) surface, Object Animation is similar to live action photography taking place in a three-dimensional area.

John Gati’s creations succeed in making the product itself (the object) become the hero of the commercial, which is one of the basic tenets of good “sell” advertising. Complicated rigs and special dimensional lighting are required to make this form of animation truly work. It requires enormous intricacy to sustain the fantasy of “life” for these objects. John works with such materials as foams, wires, rubbers, vinyls, plastics, silks, clays and waxes to create the illusion of “reality.” Working in the tradition of the great artists and artisans of the past, John — like McLaren and Trnka and Geesink — has created a wondrous world of living and moving objects that reflect a “life all their own. Among his most recent successes are Fleischman’s “Egg Beaters” and Speidel’s “Faces In the Watch-bands. ”

In passing, we would also like to salute the following fine practioners of the art: Snazelle Films and Kurtz and Friends for their fine Levis efforts; Bill Melendez (Bill Melendez Productions); Hal Silvermintz (Perpetual Motion); Carlos Sanchez (IF Studios); William Littlejohn (William Littlejohn Productions); and Art Babbitt (Hanna-Barbera Commercials.)

The boundaries of animation are limitless. They defy time and space. They fuse reality with fantasy. They create new life out of old forms. Most animators believe the future will see the development of completely new and exciting techniques for the art. More use of famous illustrators and designers from the non-animation world. New developments in computer animation. More combinations of live action and animation within the same frame. More sophisticated “selling” within the framework of fantasy and humor. New breakthroughs in stop motion object animation. Fresh combinations of tape and film in animation. Unusual variations on dimensional and multi-plane animation effects.

For the most part animators strongly feel animation commercials can achieve greater results than live action, because “they can be funnier and they can be controlled absolutely” (Lee Savage); “You can get information across quicker” (Bob Godfrey);” ” “Animation makes an incredible statement real… In animation, sweeping moves are totally acceptable as opposed to the heaviness of human action (Mort Goldsholl).”

What is evident, too, is that small teams are creating the most significant new work in animation today. While the Disneys and Hanna-Barberas continue to produce a great volume of praise-worthy animation for film and TV, the breakthroughs are, for the most part, coming from the isolated artists and small creative teams working throughout the country.

And bridging the gap between these artists and the advertising agencies are producers like Harold Friedman of The Directors Circle, who fully understand the needs of both parties for creative expression, on the one hand, and sound selling messages, on the other. In the final analysis, an animated commercial to be successful must motivate the consumer to buy the product, or the service, or the idea put forth by the commercial. That is its major raison d’etre. It should be charming, to be sure, and filled with fun and fantasy — but it must ultimately sell its clients’ products in the marketplace to achieve its truest objectives.

Animation &Articles on Animation &Books &Independent Animation 20 May 2010 09:35 am

Zagreb’s Start

- Recently, I’ve tried to put a bit of focus on some International world leaders in animated film and give some attention to the heroes of the past. Naturally, Zagreb Film would be a source of many important names. This was a Yugoslavian studio that had limited resources and budget and they did the most with what they had. When their film, Ersatz, won the Oscar in 1961, it put this small studio on the map. Dusan Vukotic, the director of that film, led the studio.

Here’s a couple of small excerpts from a book, Z is for Zagreb by Ronald Holloway, that gives a good overall view of the start of the studio and a bit about Vukotic’ biography.

In the early Fifties, the Yugoslav economy was getting off the ground and business advertisements began to appear in the newspapers. The possibility arose again of producing publicity films, as the Maar Brothers had done successfully before the war. Besides, a staff of trained Duga personnel was becoming bored with comic strips and illustrations for books and magazines, and itched to get back into animation. When an English book store opened in Zagreb and news poured across Kostelac’s desk of UPA and Bob Cannon’s Gerald McBoing Boing, the itch became a torture. How were these beautifully designed cartoons made? There were no clues, but everyone was sure it was something for them.

Another break came in the least expected fashion. American films were being bought for Yugoslav consumption, and among those screened for selection was Irving Reis’s The Four Poster (1952). The film itself was not so important, but the animation bridges between sequences were. A sparking, tongue-in-cheek design by John and Faith Hubley graced the antics of Rex Harrison and Lili Palmer in the two-role film: it was the first UPA “cartoon” to enter the country. The film was screened by an excited small audience over and over, and then sent back to the source from which it came—unbought! Harrison and Palmer were never to know how important they were to the growth of Zagreb animation.

Another break came in the least expected fashion. American films were being bought for Yugoslav consumption, and among those screened for selection was Irving Reis’s The Four Poster (1952). The film itself was not so important, but the animation bridges between sequences were. A sparking, tongue-in-cheek design by John and Faith Hubley graced the antics of Rex Harrison and Lili Palmer in the two-role film: it was the first UPA “cartoon” to enter the country. The film was screened by an excited small audience over and over, and then sent back to the source from which it came—unbought! Harrison and Palmer were never to know how important they were to the growth of Zagreb animation.

With these innovations in mind a veteran group of cartoonists gathered around Kostelac and Vukotic to make advertising films on their own. Production manager was Kostelac, script and direction flowed from Vukotic, Marks (already an acknowledged graphic artist) did the designs, Jutrisa and Kostanjsek animated, and Bourek and Kolar painted the backgrounds. The money came out of their own pockets, but they were able to secure from Zagreb Film production and distribution help. Vukotic and Kostelac toured the country, and with the help of a fellow Montenegran Vukotic secured the necessary commissions from factories and business concerns. Then he and Kostelac retired to a hotel room with typewriter and drawing board to come up with a suitable idea. Thirteen advertising films, ranging in length from thirty seconds to one minute, were produced in the period 1954—55, eleven of them in colour.

Since material resources and particularly the availability of cels (transparent celluloids containing the drawings to be photographed) were limited, the process of “reduced animation” was discovered. Some films took an unbelievable eight cels to make, without losing any of the expressive movement a large number of eels usually required. Drawings were reduced to the barest minimum, and in many cases the visual effect was stronger than with twice the number of drawings. Marks and Bourek went out of their way to round up a number of artist friends to help solve complicated problems. Writers, architects, sculptors lent a creative hand whenever needed. The cartoons took on a daring, avant-garde surface, a strange character for a business enterprise. But not one of their commercial customers complained or rejected a film.

The freed drawings brought about by “reduced animation” cannot be underestimated. These were the forerunners of modern experimental television commercials, and although they appear commonplace today they were highly revolutionary in the Fifties. For the young Zagreb cartoonists the process provided a school of freedom, originality and invention. Every phase of the cartoon was broken down to its basic parts and tested and retested: script, design, background, musical accompaniment, editing, factors of rhythm and timing. By limiting the drawings the characters were freed from realistic movement and given a characteristic life of their own, thereby increasing the film’s tempo and enriching scenes with new forms of expression. Shades of meaning entered into the cartoon’s movements, details began to determine the action, and the preciseness of an expression drew its force from duration of time minutely calculated. A cartoon done at Duga Film normally required 12,000 to 15,000 drawings; reduced, it came down to 4,000 to 5,000 drawings. Further experiments uncovered new ways to compose a scene, paint a background, add a sound effect, construct a bold graphic, build a proper atmosphere, and finally edit tensions into the action to reach a satisfying whole. The only phase left untouched from the Duga days was the general direction of movement; everything else had somehow changed. And, most important of all, the character was no longer an anthropomorphic imitation.

The freed drawings brought about by “reduced animation” cannot be underestimated. These were the forerunners of modern experimental television commercials, and although they appear commonplace today they were highly revolutionary in the Fifties. For the young Zagreb cartoonists the process provided a school of freedom, originality and invention. Every phase of the cartoon was broken down to its basic parts and tested and retested: script, design, background, musical accompaniment, editing, factors of rhythm and timing. By limiting the drawings the characters were freed from realistic movement and given a characteristic life of their own, thereby increasing the film’s tempo and enriching scenes with new forms of expression. Shades of meaning entered into the cartoon’s movements, details began to determine the action, and the preciseness of an expression drew its force from duration of time minutely calculated. A cartoon done at Duga Film normally required 12,000 to 15,000 drawings; reduced, it came down to 4,000 to 5,000 drawings. Further experiments uncovered new ways to compose a scene, paint a background, add a sound effect, construct a bold graphic, build a proper atmosphere, and finally edit tensions into the action to reach a satisfying whole. The only phase left untouched from the Duga days was the general direction of movement; everything else had somehow changed. And, most important of all, the character was no longer an anthropomorphic imitation.

When they appeared in the cinemas, the fantastic, dynamic feeling inside these cartoons charmed the public. Former staff members couldn’t match the finished product with the number of cels used. More commissions began to roll in, and Zagreb Film took another look at the young innovators within the company. As the way opened for new production standards in 1956 (due to a new law separating Zagreb Film from its film distribution branch), it was decided to give story animation another try. The resourceful Kostelac pulled out of a sleeve a card file of former Duga employees, and rounded them up with a taxi and a knock on the door. Enough responded to begin work immediately on a story cartoon for the Pula Festival (another scheme of Fadil Hadzic to promote the growth of Yugoslav cinema), and they worked day and night on The Playful Robot. Script was by Andre Lusicic, direction by Vukotic, design by Marks and Kolar, animation by Jutrisa and Kostanjsek, backgrounds by Bourek—and mistakes by all. There was something basically Disneyish about this effort, and it was admittedly inferior to the high-powered antics of the characters in the ad films.

Nevertheless, Vukotic won a prize at Pula for pioneering Yugoslav animation, and Zagreb Film found itself with an animation studio.

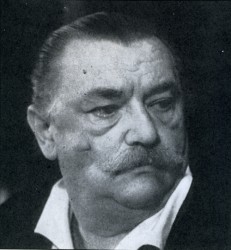

Dusan Vukotic

(Born 1927 in Bileca).

The most important name in Yugoslav animation. It was through his drive and determination that the cartoon won respectability at home and recognition abroad. He has won over fifty prizes and citations for his sixteen major cartoons. He studied architecture and worked as cartoonist on Fadil Hadzic’s Kerempuh, moving up to head of his own unit under Hadzic at Duga Film in 1951—52. As director, designer and animator he created the national figure of Kico, a little government official on inspection tours about the country. How Kico was Born (1951) and The Haunted Castle at Dudinci (1952) represent the best work done at Duga Film, and drew their inspiration from Trnka’s Czech cartoons instead of Disney. After the collapse of Duga Film, Vukotic and Kostelac produced on their own homemade advertising films, and with Marks, Kolar and Bourek he discovered the principles of “reduced animation” (sharply limiting the number of drawings for a short cartoon). He made eleven advertising films as scriptwriter and director, distributed through Zagreb Film, and one publicity film. The Magic Catalogue (1956), for Dragutin Vunak at Interpublic. When Zagreb Film turned to the feature cartoon, Vukotic created The Playful Robot (1956) with the combined talents of Marks, Kolar, Kostanjsek, Jutrisa and Bourek, and was given the Golden Arena at the Pula Festival for pioneering animation in Yugoslavia. He fostered the satire in animation, aiming Cowboy Jimmie (1957), Concerto for Sub-Machine Gun (1958) and The Great Fear (1958) at the American Western, the gangster film, and the horror film. In the beginning he preferred to work with another designer, employing Marks on The Playful Robot, Cowboy Jimmie, and Magic Sounds (1957), and Kolar on Abra Kadabra (1957). The Great Fear, Revenger (1958), Concerto for Sub-Machine Gun, and My Tail is My Ticket (1959), and Grgic on Cow on the Moon (1959). He was the first in the studio to direct, design and animate independently, winning a number of awards for Piccolo (1959) and establishing his characteristic theme of feuding neighbours. His next two

The most important name in Yugoslav animation. It was through his drive and determination that the cartoon won respectability at home and recognition abroad. He has won over fifty prizes and citations for his sixteen major cartoons. He studied architecture and worked as cartoonist on Fadil Hadzic’s Kerempuh, moving up to head of his own unit under Hadzic at Duga Film in 1951—52. As director, designer and animator he created the national figure of Kico, a little government official on inspection tours about the country. How Kico was Born (1951) and The Haunted Castle at Dudinci (1952) represent the best work done at Duga Film, and drew their inspiration from Trnka’s Czech cartoons instead of Disney. After the collapse of Duga Film, Vukotic and Kostelac produced on their own homemade advertising films, and with Marks, Kolar and Bourek he discovered the principles of “reduced animation” (sharply limiting the number of drawings for a short cartoon). He made eleven advertising films as scriptwriter and director, distributed through Zagreb Film, and one publicity film. The Magic Catalogue (1956), for Dragutin Vunak at Interpublic. When Zagreb Film turned to the feature cartoon, Vukotic created The Playful Robot (1956) with the combined talents of Marks, Kolar, Kostanjsek, Jutrisa and Bourek, and was given the Golden Arena at the Pula Festival for pioneering animation in Yugoslavia. He fostered the satire in animation, aiming Cowboy Jimmie (1957), Concerto for Sub-Machine Gun (1958) and The Great Fear (1958) at the American Western, the gangster film, and the horror film. In the beginning he preferred to work with another designer, employing Marks on The Playful Robot, Cowboy Jimmie, and Magic Sounds (1957), and Kolar on Abra Kadabra (1957). The Great Fear, Revenger (1958), Concerto for Sub-Machine Gun, and My Tail is My Ticket (1959), and Grgic on Cow on the Moon (1959). He was the first in the studio to direct, design and animate independently, winning a number of awards for Piccolo (1959) and establishing his characteristic theme of feuding neighbours. His next two  independent cartoons were also highly awarded: Ersatz (1961), winning the first Academy Award for animation outside the United States, and Play (1962), voted the best short film of the year at Mannheim. Turning to the feature film, his The Seventh Continent for children in 1966 was not successful but it encouraged him in the cartoon to continue the mixture of live action and animation begun in Play. Stain on the Conscience (1968) employed animation drawing on documentary footage and proved him capable of directing actors ; in a psychological atmosphere. Opera Cordis (1968) restored his eminent position in animation with a salty commentary on Dr. Barnard’s heart transplants, and Ars Gratia Art/s (1 969) more than effectively spoofed the amateur who will do anything for the sake of art and applause. He also wrote the scripts for Vrbanic’s All the Drawings of the Town (1959) (with Vrbanic), Gospodnetic’s The Lion Tamer (1961), Dovnikovic’s The Doll (1961), Grgic’s A Visit from Space (1961), and Blazekovic’s Gorilla’s Dance (1968), and had a hand in supervising most of these films as well as Grgic’s The Devil’s Work (1965). His gifts as a leader are evident every step of the way, but particularly in the first phase of Zagreb Film (1956— 62) when his unit competed for honours with Mimica’s and Kristl’s. He is best in the cool domains of satire and caricature.

independent cartoons were also highly awarded: Ersatz (1961), winning the first Academy Award for animation outside the United States, and Play (1962), voted the best short film of the year at Mannheim. Turning to the feature film, his The Seventh Continent for children in 1966 was not successful but it encouraged him in the cartoon to continue the mixture of live action and animation begun in Play. Stain on the Conscience (1968) employed animation drawing on documentary footage and proved him capable of directing actors ; in a psychological atmosphere. Opera Cordis (1968) restored his eminent position in animation with a salty commentary on Dr. Barnard’s heart transplants, and Ars Gratia Art/s (1 969) more than effectively spoofed the amateur who will do anything for the sake of art and applause. He also wrote the scripts for Vrbanic’s All the Drawings of the Town (1959) (with Vrbanic), Gospodnetic’s The Lion Tamer (1961), Dovnikovic’s The Doll (1961), Grgic’s A Visit from Space (1961), and Blazekovic’s Gorilla’s Dance (1968), and had a hand in supervising most of these films as well as Grgic’s The Devil’s Work (1965). His gifts as a leader are evident every step of the way, but particularly in the first phase of Zagreb Film (1956— 62) when his unit competed for honours with Mimica’s and Kristl’s. He is best in the cool domains of satire and caricature.

Images:

1. The Four Poster – from Amid Amidi‘s Cartoon Modern

2. Cowboy Jimmie

3. Dusan Vukotic

4. Ersatz

Daily post 24 Apr 2010 07:52 am

Recap – Trnka’s Merry Circus

- I’ve been posting quite a few pieces about 3D stop motion animation. It’s always good to remember that the first real genius of this medium was Jiri Trnka. I previously posted this piece in 2007 which focuses on one of the few 2D animated films of Trnka.

– I’ve been a fan of Jirà Trnka‘s work since I first saw it back in the 60′s. I’ve bought every publication I’ve ever found which discusses or displays his films or illustration. These days I can also own a number of his films.

– I’ve been a fan of Jirà Trnka‘s work since I first saw it back in the 60′s. I’ve bought every publication I’ve ever found which discusses or displays his films or illustration. These days I can also own a number of his films.

His puppet films were always the gold standard of that medium. However, since I’ve studied his illustrations for many years, I’m always interested in the 2D work he’s done.

The dvd titled The Puppet Films of Jirà Trnka includes one of these 2D films. It’s cut-out animation, so it really borders the world between 2D and 3D. Trnka exploits the shadows on his constructed cardboard backgrounds to great effect. The style purposefully hides the three dimensions of the constructions, but it uses it when it needs to. The film is a delicate piece which just shows a number of acts in a local circus setting.

It’s a sweet film with a quiet pace. I’m not sure it could be done in today’s world of snap and speed. No one seems to want to take time to enjoy quiet works of art.

I’m posting a number of frame grabs from this short so as to highlight the piece.

Note the real shadows on the background.

These were obviously animated on glass levels in a multiplane setup.

Again, note the excellent use of shadows. It’s very

effective in these long shots of the trapeze artists.

Animation &Articles on Animation &Independent Animation &Puppet Animation 06 Apr 2010 06:15 am

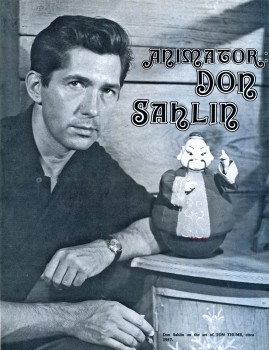

Don Sahlin

- After posting some stills from Ray Harryhausen’s Golden Voyage of Sinbad, I decided to look back and see if there were any other material I could post about 3D model animation.

I came upon this interview with Don Sahlin in Closeup Magazine, no. 2. published in 1976 by David Prestone.

(Bio)

Born in Stratford, Connecticut, Don Sahlin (say—lien) was introduced to the world of marionettes at age eleven, when he saw a production of HANS BRINKER AND THE SILVER SKATES by the New York Marionette Guild.

Born in Stratford, Connecticut, Don Sahlin (say—lien) was introduced to the world of marionettes at age eleven, when he saw a production of HANS BRINKER AND THE SILVER SKATES by the New York Marionette Guild..

Joining the PUPPETEERS OF AMERICA organization, he was soon inundating many of that group’s members with letters of inquiry as to the correct method of constructing and performing marionette shows. This correspondence brought Don an offer from Rufus Rose (who, several years later, was to create all of the figures for the HOWDY DOODY televison show) to spend several weekends with Rose and his wife as an apprentice.

.

In 1946, Don started another apprenticeship of many years standing when he began working with Martin and August Stevens, who performed sophisticated marionette dramas of subjects like Macbeth, Joan of Arc, and Cleopatra.

.

A stint of Summer Stock in Rhode Island followed, when Don felt he would try his hand at the acting profession, but he soon became disenchanted with this form of theater work. In 1949, Don traveled to Hollywood, where he worked with puppeteerist Bob Baker, doing party shows for many of the movie stars there.

.

Don then returned home to perform a show of his own designing, SAINT GEORGE AND THE DRAGON, which played around the Connecticut area. Later jobs involved working with very large puppets accompanied by a symphonic orchestra, Chinese shadow plays, and, in 1950, a marionette version of the LAND OF OZ stories that Burr Tilstrom was preparing as a television pilot. Working for a year on this project, Don was then drafted into the army.

CLOSEUP: How did you first get involved with stop-motion animation?

.

DON SAHLIN: When I got out of the Army in 1953, I had heard that Michael Myerberg was looking for puppeteers to work on HANSEL & GRET-EL. For some reason, he thought that puppeteers would make better animators than (stop-motion) animators! I was interviewed and got the job. I had to then go through a three-week training period with Myerberg in order to better acclimate myself with stop-motion. It was a very bizarre setup.

DON SAHLIN: When I got out of the Army in 1953, I had heard that Michael Myerberg was looking for puppeteers to work on HANSEL & GRET-EL. For some reason, he thought that puppeteers would make better animators than (stop-motion) animators! I was interviewed and got the job. I had to then go through a three-week training period with Myerberg in order to better acclimate myself with stop-motion. It was a very bizarre setup..

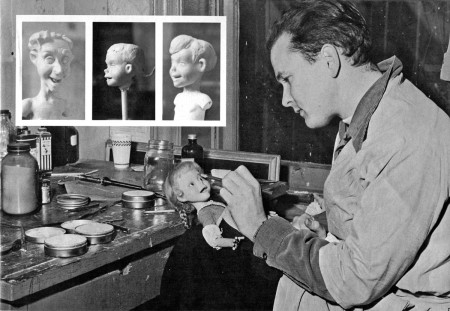

CU: Do you recall who sculpted the puppets?

.

DS: A man by the name of Jim Summers did the sculpturing. As I recall, they had a special machine shop where all the armatures were constructed. I’d give anything to own one of those armatures now. They were pieces of art.

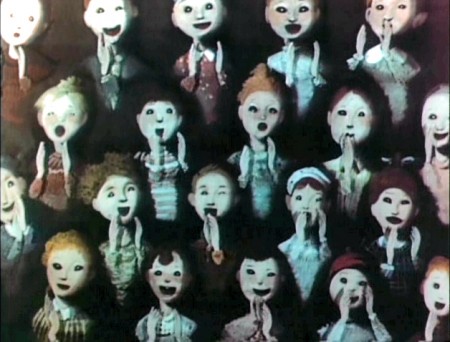

James Summers applies makeup to an almost finished Gretel.

Inset: Clay heads by Summers.

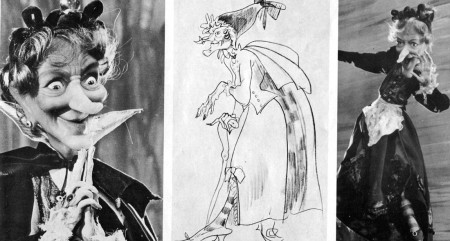

Below: Evil Witch Rosina Rubylips views herself

as portrayed in a preproduction sketch.

.

CU: Were they all ball-socket in construction?

DS: They were, but you’d press levers, which was really interesting. If you wanted to move the thigh, for instance, you’d press a little lever near the thigh area which would release it for a tiny movement. Removing pressure from the lever would freeze the puppet in position. As you may know, they were all held on the stage with electromagnets.

CU: Could you elaborate on how that was done? It’s interesting that Myerberg used that method of support as opposed to the tie-downs used by today’s animators. . .

DS: The base of the stage was all metal, and they had these strong electromagnets underneath. The puppets really clomped down on them. Of course, we’d have to break the electromagnetic field in order to move the legs to their next position. One night, as I remember, we were working on a very hard scene. Myerberg had a twenty-four-hour shift there, and the animation varied so greatly because people would come in and start animating where the day-shift had left off! We went out to dinner, and somehow, somebody had hooked the electromagnets into the main power source. Naturally, we killed all the lights as we went out. As we pulled the switch, we heard a series of plops. All the puppets had fallen over! We had to start the whole thing all over again! I quit twice on that film … I never got screen credit, because I quit before it ended.

CU: Here’s a quote from the book Puppet Animation in the Cinema: “The Kinemins used in HANSEL & GRETEL . . . were controlled by the use of electrical solenoids, and electromagnets in the feet. . . a system which is a closely-guarded trade secret…”

DS: (Laugh) That’s a lot of bunk, you know. The only thing “electronic” was the electromagnetic setup that held the puppets on the stage. Myerberg had a big panel upstairs where he’d use close-up heads that were wired to this big, blinking board. You’d turn knobs, but there was nothing electronic involved. There was simply a wire inside the mouth, and with a twist of a certain knob, the mouth would go “that way,” and so on. But it was all manual. Anything else that was said was a big put-on.

CU: A similar incident occurred with the publicity on Ray Harryhausen’s 7TH VOYAGE OF SIN-BAD, where the reporters of the media were quot-iny the producer on how the skeleton fight was “electronically” controlled . . .

DS: Nothing but press stuff, I would imagine. I’m glad you mentioned Harryhausen. God, I love his work. The one I saw recently again that I just adore was JASON AND THE ARGONAUTS. His work was absolutely superb. Classical mythology is such a wonderful area to explore. Why don’t they do more things like that?

CU: We’ve been asking ourselves the same question !

DS: Those skeletons were frightening! You know, I’ve learned to enjoy animation more now because I’ve been away from it for so long. But it’s a curious thing. Do you remember Trnka’s A MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM? I saw it again and fell asleep through most of the whole thing! I was just so aware of how long it took to do each scene that it fatigued me … But it was a beautiful film.

CU: Getting back to HANSEL & GRETEL. Who actually did the camerawork on it?

DS: That was a very strange thing. Myerberg hired Martin Munkasci to photograph the animation. He was one of the great still photographers and had done a lot of things with Garbo and so on. Oddly enough, Myerberg felt that since stop-motion was nothing but a series of still frames, a capable still photographer would be more appropriate to do the camerawork. It was a very strange rationale on his part. Martin knew virtually nothing about motion pictures. Fortunately, a very fine Acme camera was used which was simple to operate, and he would just line up the shots and photograph. Anyhow, we went nuts, going up and down opening and closing those trapdoors all night long, sitting under that stage! And those sets were gigantic. Many of the backdrops were paintings, but a lot of it was also dimensional.

CU: We know that Myerberg isn’t with us anymore. What became of his organization after HANSEL & GRETEL?

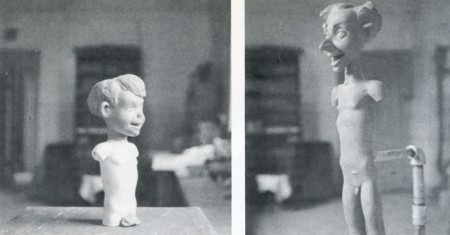

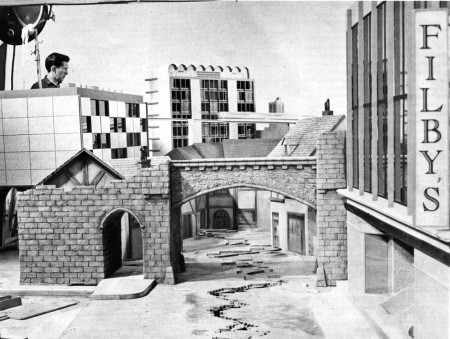

Above: The beginnings of the KINEMINS . . .

incomplete sculptures of Hansel and his father .

Below: Several puppet figures and a set (which predate all work

on HANSEL AND GRETEL) from ALADDIN AND THE WONDERFUL LAMP.

All sets and puppets for this project were put aside

once work began on the Humperdink musical.

.

DS: Myerberg had all sorts of aspirations to do other things, but they never materialized. I think his sons own the film now.

CU: Where did you go from there?

DS: After I left Myerberg, I was in association with Kermit Love, who had also worked on the film. We were going to do a full-length motion picture Of Beatrix Potter’s TAILOR OF GLOUCESTER. It’s a charming story about a tailor and a Whole community of mice. We were going to animate all of the mice. We had the whole thing set up in London . . . Robert Donat was signed to play the lead role and Margaret Rutherford was also cast for the film. We began building the mice and we had some funding, although we hadn’t gotten to the point where we were able to build them all. Suddenly, we had a bad partnership and the whole project collapsed.

CU: Would the animated mice have been combined with live actors in the same scene?

DS: No, they would have been separate. I don’t really like it when they combine things, although Ray Harryhausen is a master at it. I wouldn’t want to do it in that way, but I respect what he does very much. Anyhow, I returned to the States when our TAILOR OF GLOUCESTER failed, and then got 3 call to go out and do work on TOM THUMB. That film, I think, was the most enjoyable thing I worked on during this period, because it was my first big job in Hollywood.

CU: How did you get involved with George Pal?

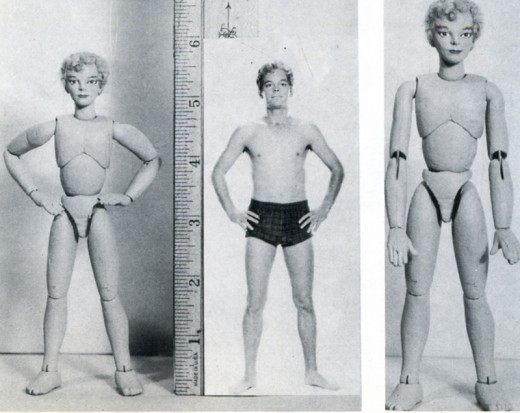

DS: At the time, 1 had been out in California working with a puppeteer friend of mine named Bob Baker. When TOM THUMB began, I was asked to build a little six-inch stop-motion marionette of Tom that they were going to use in the long shots. It was a funny thing. They said that he had to wear a fig leaf, so I carved this puppet with ball and socket joints, and he really looked naked. George was in England shooting in 1957, and decided that he wanted the puppet for a particular scene. But all my work was in vain, because the fig leaf that Tom wore covered almost his entire body. I had thought that the fig leaf would be in scale with his body, but that’s not the way it turned out. I think Wah Chang has the little Tom Thumb figure now, but I would love to own it. It was really an exquisite little puppet. It was all carved out of walnut, and I filled the legs with lead to make them heavy. It was never used in the closer shots, just distance stuff.

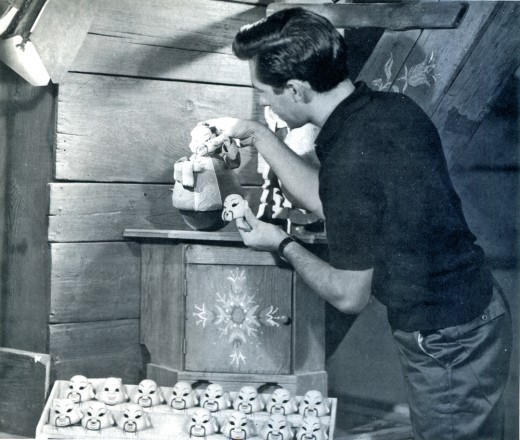

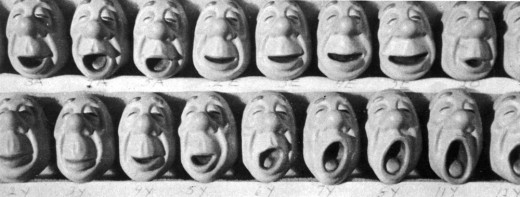

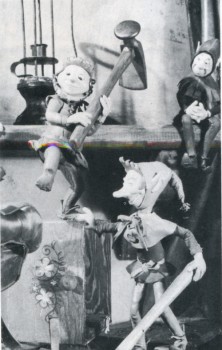

Two photos illustrating the replacement method of animation, utilized on TOM THUMB.

Instead of achieving changes of expression through manipulation of a stop-motion model’s

facial features, a series of heads are prodced, each head having a slightly different

expression on it. Changes are made by simply substituting one head for another.

Above: Don Sahlin placing a head on Con-fu-shun, and

Below: Numbered heads created for The Yawning Man animated by Gene Warren.

.

CU: How did you get to be a part of Project Unlimited?

DS: After I had carved the little stop-motion marionette, they started filming all of the animation sequences, but 1 had to go back to New York. Then Bob Baker called me from California and told me that they needed an animator. I talked to Wah Chang, I think it was, and he said, “Come on out and work for us!” 1 worked out at Project until about 1962. They wanted me to stay on, but Burr Tillstrom of Kukla, Fran and Ollie fame wanted me to come back to New York to work with him on a Broadway show. And it’s funny how fate is. I didn’t want to go; I really loved working at the studio, especially after THE TIME MACHINE. Anyhow, I did go to work for Burr on this small, cabaret-type show at the old Astor Hotel, but it soon folded. And like I say, 1 regretted leaving Hollywood, but I also met Jim Henson of the Muppets here in Mew York, and it led to probably my most successful period.

CU: Could you tell us just what you animated on TOM THUMB?

DS: I animated Con-fu-shun, a lot of the little guys that just popped up, and the Jack-in-the-Box. Gene Warren and I did all of the animation, just the two of us. Gene is a marvelous animator; he did the Yawning Man sequence. I spoke to Gene a little over a year ago, and I was so happy to find out that he does my favorite commercials—Chuck-wagon! To me, the most charming commercials ever done!

CU: What were some of the techniques used in animating Con-fu-shun?

DS: I remember Con-fu-shun was a very simple puppet. The armature was bolted to the stage and he just rocked. Occasionally, I think he got off for a couple of drop shots. The facial expressions were accomplished by replacing just the faces, which were made out of wax. We had a whole tray of all his faces. We’d just put on “E1″ or “E2,” or “Smile 1,” “Smile 2.” I know his eyes were not connected to the face; they were always independent. The faces just slipped on in perfect registration. I remember the little eye-pick I used for animating his eyes; it looked like a little hypodermic needle.

The TOM THUMB marionette created by Don Sahlin and used only in long shots.

CU: Did you have anything to do with constructing the large prop furniture, or giant hands and horse’s ears, that Russ Tamblyn was to interact with?

DS: No, that was all done at MGM, in England. Project Unlimited was a kind of neat little studio by itself, completely independent. Pal would do all of his stuff at MGM, but I wasn’t involved in the work done there, even on THE TIME MACHINE.

CU: You did some work on DINOSAURUS. Could you talk a bit about it? We know that,the models were built by Marcel Delgado, but little is known about who actually did what as far as the animation goes . . .

DS: I animated the Tyrannosaurus and the fight scenes that were involved with it. The rest of the animation was done by myself and Tom Holland; he got to do most of the Brontosaurus, the less ferocious of the creatures. I remember the night we finished the scene where the Brontosaurus died in the quicksand. The material used for quicksand was Fuller’s earth; I guess it’s used because it looks in scale. We had a kind of screw-jack that the puppet got on, and we kept pulling it down slowly in stop-motion, beneath the surface of the quicksand. When we finished the scene, we were exhausted. Then we asked ourselves, “Should we leave him in or take him out,” this great piece of sponge rubber? So we pulled him out again and we were hosing him off and cleaning him up. It was funny!

I also remember the night the big dinosaur fight took place. They were playing Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring in the background and boy, it really inspired us to animate! We got through that fast, where they were tearing and ripping at each other.

CU: Is Tom Holland still animating in Hollywood?

DS: I don’t know what Tom is doing now. It’s interesting; Tom wasn’t really an animator. He was an actor, primarily, and he somehow got involved in animation. We did all of those scenes together. I recall another amusing incident on DINOSAURUS. Do you remember those close-up shots of the manually-operated dinosaurs that we intercut? We once spent a whole day boiling ochra and straining it to make it look like saliva was really dripping from their mouths. It was just hideous!

CU: DINOSAURUS is an interesting thing to look at as an animation film, but technically, it did seem to be somewhat under par in comparison with some of the others. . .

DS: It was a very cheap film. A lot of the rear projection work was just awful, especially the scene at the beginning when the guy came running out of the shack and the dinosaur came to life. Those shots were far from pleasing.

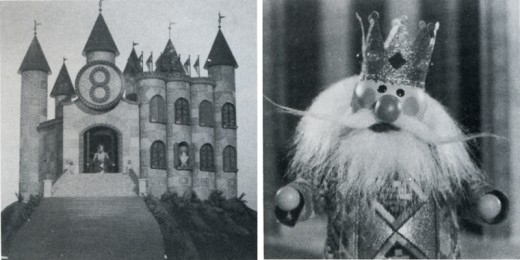

Project Unlimited technicians working on the large

manually-operated dinosaurs created for DINOSAURUS.

Left: Marcel Delgado applies the finishing touches to the Brontosaurus mockup.

Middle: Tom Holland and the Tyrannosaurs Rex “skeleton”.

CU: How big were the models in DINOSAURUS?

DS: Most of them were relatively small, except for the Brontosaurus, which was awfully big. You probably remember that we had a little doll of a boy riding on its back. I have a theory that large figures are hard to animate. Something happens, some strange phenomenon, which I can’t understand, takes place. I guess I’m not that kind of a perfect animator; I sort of do it loosely. I did TOM THUMB because that was all very contained. I got a lot out of the character as far as hand movements and so on. But the stuff that Jim Danforth did for BROTHERS GRIMM was just so superb that I would go insane doing that. I’m really into marionettes; I think that there’s a lot of potential in them for fantasy films in certain instances. I remember telling Gene Warren about some of those long shots where they were Trudging through the jungle in DINOSAURUS: “You know, I could do that better with marionettes.” I really think that one can augment the two.

CU: Project Unlimited also did some work on SPARTACUS…

DS: Yes, our little studio was always doing unusual props and effects for films, in between our animation jobs. Kirk Douglas was producing and starring in a monumental production of SPARTACUS, and Project Unlimited was called in to make about ‘ two or three hundred dead bodies, in various f scales, for some of the battle scenes. The largest * were about one-third life-size … We used molds to make them, and then we’d dress them in armor and sort of strew them all over the battlefields. I then i had to slash and “gore them up” with fake blood! We also made a bunch of horses out of polyure-thane foam. They weren’t very detailed, though-we just had to make sure they’d be recognizable from a distance, but none of them were shown in closeups.

CU: What did you do on THE TIME MACHINE?

DS: I worked on virtually all of the special effects.