Category ArchivePuppet Animation

Commentary &Puppet Animation 27 Feb 2009 08:56 am

Puppets

- Brian Sibley has written a quite wonderful piece on Viewmaster slides. He shows people prepping to photograph these little sets and characters for the 3D setups. It’s a chance for many of us to get a quick joyride from the past.

- Brian Sibley has written a quite wonderful piece on Viewmaster slides. He shows people prepping to photograph these little sets and characters for the 3D setups. It’s a chance for many of us to get a quick joyride from the past.

Brian’s post had me do a bit more research, and I came across Brian Butler‘s site, What My Dad Saw which has many posts on the subject and actually posts a number of the slide images recreating the 3D effect.

Likewise, this led me to Brian Hunn’s site Mystery Hoard which had a longer piece on Florence Thomas and Joe Liptak who created many of these scenes.

.

.- For those of you who’d like to see more puppets on parade, Ken Priebe sent me the link to a beautiful copy of a hard-to-see George Pal Puppetoon on YouTube. Rhythm in the Ranks.

The color on this piece, given the format, is exceptional, well preserved.

. .

. .

_____________

- For those of you who get excited reading new material about puppets, Wade Sampson has an excellent article about Bob Baker’s puppet productions of Walt Disney’s animated musicals. This is an entertaining read.

- I’ve yet to see Coraline, but I’ll have to get there.

I would prefer not seeing it in 3D (polarized glasses HAVE to grey/green down the image, and I’d prefer seeing actual colors on the screen, despite the 3D effect. However, I don’t believe it’s playing in Manhattan except in 3D. The film seems to be top of the craft, though I’ve read enough semi-negative about the story. I like most of the voice talent and expect that to give the animators something good to work with.

Like Tim Burton’s Corpse Bride, Coraline enhances the 3D stop-motion animation with cgi enhancement. This is a distinct advantage modern animators have. Even 2D animation isn’t solely dependent on the Pencil Tests and computerized compositing; animated 2D films are also filled with cg embellishment. And they should be. All tools are available and should be used (although I’m not sure many cg films use 2D enhancement.) I think that’s why I get such joy out of the old George Pal and Ray Harryhausen films. What they saw was what we got. If they opened the shutter, they were usually committed to that frame. It’s amazing that we still haven’t improved on Pinocchio or Bambi or, in some ways, John Henry and the Inky-Poo

Animation &Books &Puppet Animation 28 Jan 2009 08:52 am

Jason & The Argonauts

- Currently playing at the New Victory Theatre on 42nd Street (until Feb. 1) is a theatrical presentation of Jason and the Argonauts. Given the quality of the shows that play at the New Vic, I can pretty much guarantee that this is a first rate show.

I also have no doubt that the creators have seen the Ray Harryhausen film, Jason and the Argonauts, and must have been under its spell (however subliminally) in creating the show. It would be hard to believe otherwise given the reputation of the film. The skeleton fight, alone, makes the film famous.

This gives me a good excuse to attend to Mr. Harryhausen’s film and post the chapter from his 1972 book, Film Fantasy Scrapbook, about that film. The book is written in the first person singular and collects B&W images like a scrapbook.

Here it is:

Of the 13 fantasy features I have been connected with I think Jason and the Argonauts pleases me the most. It had certain faults, but they are not worth detailing.

Its subject matter formed a natural storyline for the Dynamation medium and like The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad strayed far from the conventional path of the “dinosaur exploitation film” with which this medium seemed to be identified.

Taking about two years to make, it unfortunately came out on the American market near the end of a cycle of Italian-made dubbed epics based loosely on the Greek-Roman legends, which seldom visualized mythology from the purely fantasy point of view. But the exhibitors and the public seem to form a premature judgment based on the title and on the vogue. Again, like Sinbad, the subject brewed in the back of my rnind for years before it reached the light of day through producer Charles Schneer. It turned out to be one of our most expensive productions to date and probably the most lavish. In Great Britain it was among the top ten big money makers of the year.

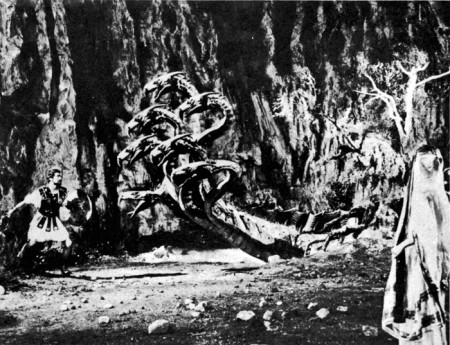

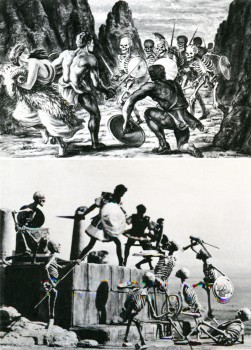

A preproduction drawing (above) compares favorably with a film still (below.)

The drawing is quite a bit more dynamic. (After all, it is Dynamation!)

(Click any image to enlarge a bit.)

Likewise, a drawing of the hydra (above) film still (below.)

Some of the difference in basic composition between the pre-production sketches I made for Jason and the counterparts frames of the production is the direct result of compromising with available locations.

For example, the ancient temples in Paestum, southern Italy, finally served as the background for the “Harpy” sequence. Originally we were going to build the set when the production was scheduled for Yugoslavia. Wherever possible we try to use an actual location to add to the visual realism. To my mind, most overly designed sets one sees in some fantasy subjects can detract from, rather than add to the final presentation.

Again, it depends on the period in which it is made as well as on the basic subject matter. Korda’s The Thief of Bagdad was the most tastefully produced and designed production of any film of this nature but unfortunately the budget that was required would be prohibitive with today’s costs.

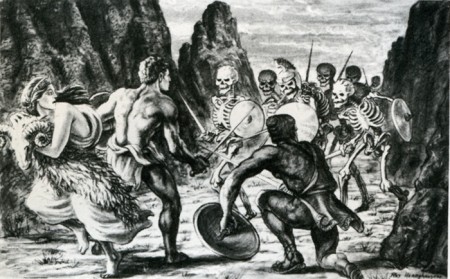

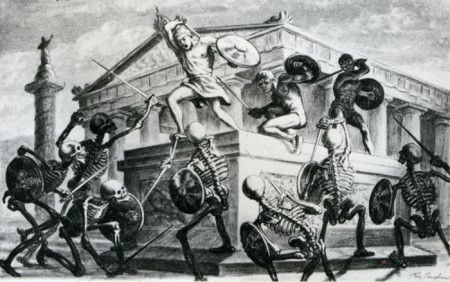

The Skeleton Sequence was the most talked-ahout part of Jason. Technically, it was unprecedented in the sphere of fantasy filming. When one pauses to think that there were seven skeletons fighting three men, with each skeleton having five appendages to move each frame of film, and keeping them all in synchronization with the three actors’ movements, one can readily see why it took four and a half months to record the sequence for the screen.

My one regret is that this section of the picture did not take place at night.

Its effect would have been doubled.

Certain other time-consuming technical “hocus-pocus” adjustments had to be done during shooting to create the illusion of the animated figures in actual contact with the live actors. Bernard Herrmann’s original and suitably fantastic music score wrapped the scenes in an aura of almost nightmarish imagination.

In the story, Jason’s only way of escaping the wild battling sword wielding “children of Hydra’s teeth” is to leap from a cliff into the sea. (Above left) A stuntman, portraying Jason for this shot, leaps from a 90-foot-high platform into the sea closely followed by seven plaster skeletons. It was a dangerous dive and required careful planning and great skill. It becomes an interesting speculation when dealing with skeletons in a film script. How many ways are there of killing off death?

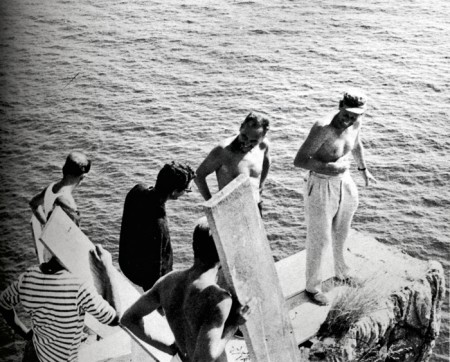

(Above right) Another angle with the real Jason jumping off a wooden platform into a mattress a few feet below. The skeletons and the rocky cliff were put in afterwards while the mattress was blotted out by an overlay of sea.

Director Don Chaffey and Ray Harryhausen discuss the leap with Italian stunt director Fernando Poggi.

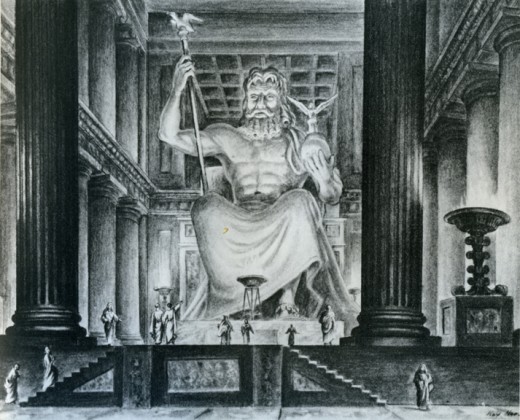

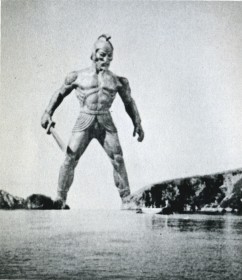

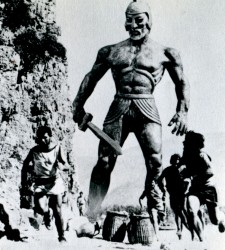

When transferring published material to the screen it is almost always necessary to take certain liberties in the work in order to present it in the most effective visual terms. Talos, the man of bronze, did exist in Jason legend, although not in the gigantic proportions that we portrayed him in the film. My pattern of thing in designing him on a very large scale stemmed from research on the Colossus of Rhodes.

The actior: his blocking the only entrance to the harbor stimulated many exciting possibilities. Then too, the idea of a gigantic metal statue coming to life has haunted me for years, but without story or situation to bring it to life. It was somewhat ironic when most of my career was spent in trying to perfect smooth and life-like action and in the Talos sequence, the longest animated sequence in the picture, it was necessary to make his movements deliberately stiff and mechanical.

Most of Jason and the Argonauts was shot in and around the little seaside village of Palinuro, just south Naples. The unusual rock formations, the wonderful white sandy beaches, and the natural harbor were within a few miles of each other, making the complete operation convenient and economical. Paestum, w its fine Greek temples, was just a short distance north. All interiors and special sets were photographed in a sm studio in Rome.

(Above left) Talos, the statue of bronze, pursues Jason’s men.

(Above left) Talos, the statue of bronze, pursues Jason’s men.

(Above right) Talos blocks the Argo

from the only exit of the bay.

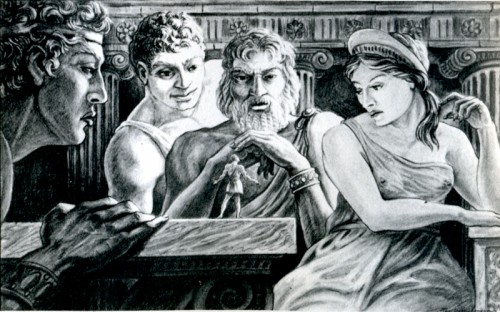

Pre-production drawing of Jason speaking to the Gods of Greece.

For the second unit operation a special platform had to be fitted to the Argo in order to achieve certain camera angles. Although it looks precarious it was far more convenient than using another boat for the shots.

The Argo had to be, above all, practical in the sense that it must be seaworthy as well as impressive. It was specially constructed for the film over the existing framework of a fishing barge. There were twin engines for speed in maneuvering, which also made the ship easily manipulated into proper sunlight for each new set-up.

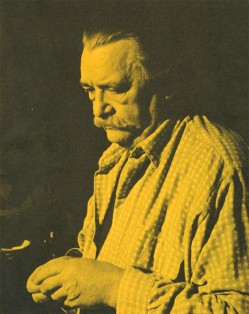

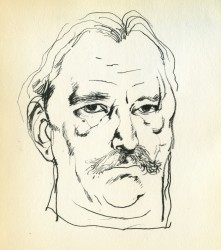

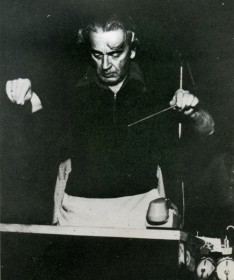

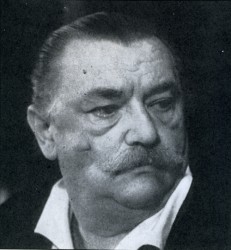

Harryhausen off the book’s back cover

to give an idea of scale of drawing sizes.

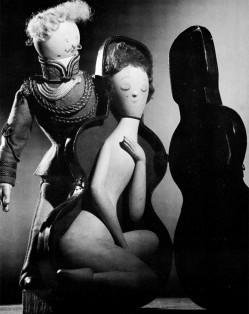

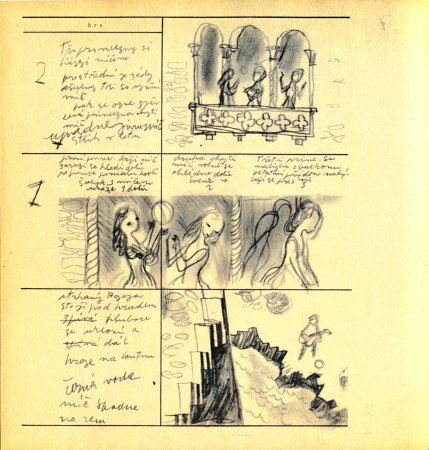

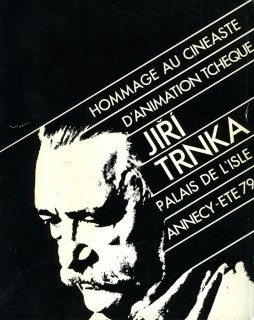

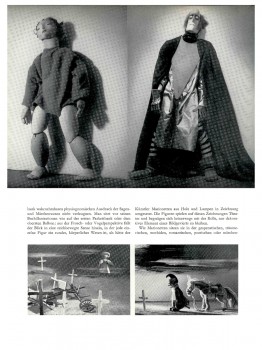

Articles on Animation &Puppet Animation &Trnka 30 Dec 2008 09:11 am

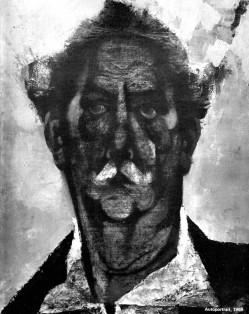

Trnka – 79

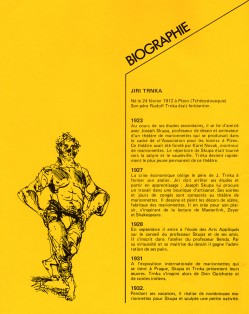

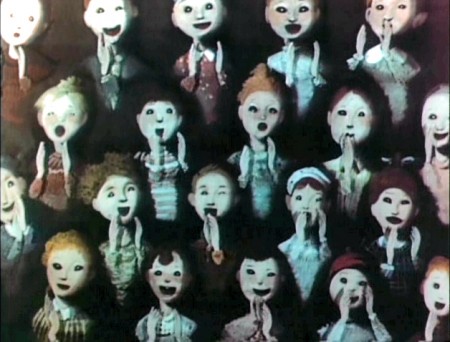

- In 1979, the Annecy animation festival celebrated the work of Jiri Trnka.

- In 1979, the Annecy animation festival celebrated the work of Jiri Trnka.

They produced a companion booklet for the film program and art exhibition. I’d long ago managed to get my hands on a copy of this booklet and am posting it here for any Trnka fanatics out there.

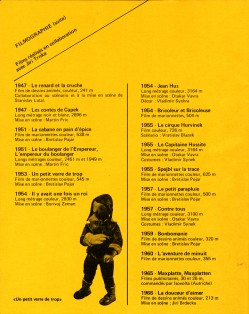

The artwork in the booklet is somewhat hard to find elsewhere, and the stills from the films are quite nicely chosen. There’s also a comprehensive biography and filmography that was included on very orange paper stock.

There aren’t too many chances to see the films anymore (other than the scattered, poor-quality YouTube pieces) except for the dvd produced by Jon Snyder. The Puppet Films of Jiri Trnka

The booklet is in French, but that shouldn’t be too much of a problem; it’s fairly self-explanatory.

(Click any image to enlarge.)

Books &Puppet Animation &Trnka 17 Nov 2008 09:14 am

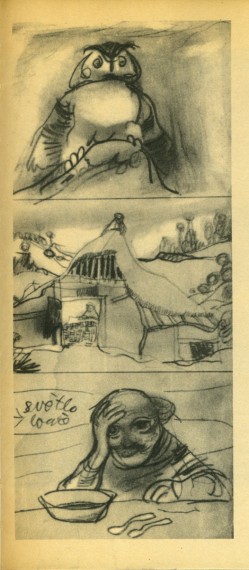

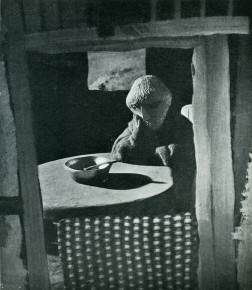

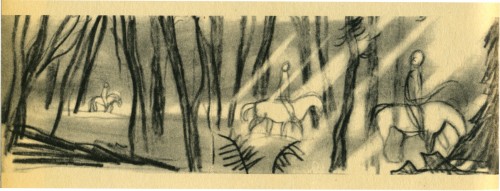

Trnka’s “Bayaya”

– Early in the history of this blog, I wrote quite a bit about Jiri Trnka. This man’s artwork has long been a source of great inspiration to me. His illustrations for the fairy tales of Grimm and Andersen are stunning and the two books are of inestimable value to me. His puppet films are so brilliantly strong and lyrically beautiful that I was overwhelmed when I first saw them, even though his reputation preceded them. I’d read enough about him and owned a magnificent biographical account of his work, that I was confident I would be a bit disappointed when I finally saw the films. I wasn’t.

– Early in the history of this blog, I wrote quite a bit about Jiri Trnka. This man’s artwork has long been a source of great inspiration to me. His illustrations for the fairy tales of Grimm and Andersen are stunning and the two books are of inestimable value to me. His puppet films are so brilliantly strong and lyrically beautiful that I was overwhelmed when I first saw them, even though his reputation preceded them. I’d read enough about him and owned a magnificent biographical account of his work, that I was confident I would be a bit disappointed when I finally saw the films. I wasn’t.

The Hand was magnificent and remains one of my favorite films, to this day.

The Archangel Gabriel and Mother Goose is a beautiful animated puppet film about Venice during the late Middle Ages.

The Midsummer Night’s Dream is a feature-length masterwork that has to be seen for any lover of animation – nevermind puppet animation.

The film, Bayaya was a mystery to me for many years. It was not an easy film to view. Back in the 70s, there was no video, and seeing Trnka’s films meant trips to the NYPublic Library in NY to visit their collection of 16mm films. There you could watch any of the collection or borrow them to watch at home. These films were often littered with many bad splices where the films had broken. The quality of the colors deteriorated over the years. It made for tough viewing, but it also made it possible to see some of the Trnka canon.

The film, Bayaya was a mystery to me for many years. It was not an easy film to view. Back in the 70s, there was no video, and seeing Trnka’s films meant trips to the NYPublic Library in NY to visit their collection of 16mm films. There you could watch any of the collection or borrow them to watch at home. These films were often littered with many bad splices where the films had broken. The quality of the colors deteriorated over the years. It made for tough viewing, but it also made it possible to see some of the Trnka canon.

Bayaya was not part of this collection. In fact, I’ve only seen part of the film once. John Gati, a NY puppet animator who was a good friend, located a copy of a 20 min excerpt (in Czechoslovakian) for an ASIFA-East screening and showed it to a small audience in a classroom at NYU. The print was black and white, but since I’d only seen B&W illustrations, this made sense.

This film represented a strong change for Trnka. He had previously done a number of cel animated films. These shorts were remarkable in that they were a strong step away from the Disney mold. This was a bold step to take in the animation community in Europe circa 1947.

The film was purely lyrical, and the story accented the folk tales quality of these legends of Prince Bayaya and The Magic Sword. Consolidating the two, he named the film after the hero and made him the embodiment of courage, morality and honor.

Trnka considered Bayaya a turning point in his career. He realized that the puppet film had taken on new strength and he had to follow through with every film thereafter.

Here are a couple of scenes from the Trnka book I treasure, Jiri Trnka: Artist & Puppet Master.

There are two parts of a documentary on Trnka available via YouTube. They’re worth the watch. Part 1, Part 2.

Articles on Animation &Puppet Animation 15 Nov 2008 09:44 am

Harryhausen Interview

- It’s been a while since I’ve posted anything about stop-motion animation, and seeing an attractive poster for Coraline made me realize it was time. I’ve recently posted some articles from the Millimeter/1975 animation issue which was edited by John Canemaker. This is another excellent piece from the same magazine, and I think it a good one.

An Interview with the Master of Stop-Motion Animation

by Mark Carducci

Film history records the earliest three-dimensional animator as George Melies, the showman-turned-filmmaker of A TRIP TO THE MOON fame. Melies, unlike many special-effects men of today, realized the value in using several different effects processes at the same time. Thus he would utilize stop-action, animation, miniature photography and mechanical effects all in the same frame. Melies was a pioneer in the field of effects animation in three dimensions, and he paved the roads other animators would one day travel. One such traveler was Willis H. O’Brien. O’Brien single-handedly elevated the techniques of three-dimensional model animation to a fine art, beginning in the silent era with short subjects and continuing through the 1925 classic THE LOST WORLD to KING KONG a mere eight years later. As Kong was king of Skull Island, so O’Brien was king of model manipulation, and tike Melies before him, O’Brien never missed an opportunity to add drama, atmosphere or pathos by mixing effects together. Witness the clash between Kong and a flying reptile atop Kong’s mountain lair: Kong and the pterodactyl are jointed foot-high foam rubber models; the mountain’s ledge is a plaster recreation; the sky background is a painting on glass; the flying reptiles in the sky are double-printed eel animation. It was this intelligent and intentional combining of effects that allowed O’Brien to achieve the marvelous sense of reality he did in KING KONG, a reality so intense as to make a thirteen-year-old named Raymond Harryhausen choose the field of special effects animation as his life’s work.

Film history records the earliest three-dimensional animator as George Melies, the showman-turned-filmmaker of A TRIP TO THE MOON fame. Melies, unlike many special-effects men of today, realized the value in using several different effects processes at the same time. Thus he would utilize stop-action, animation, miniature photography and mechanical effects all in the same frame. Melies was a pioneer in the field of effects animation in three dimensions, and he paved the roads other animators would one day travel. One such traveler was Willis H. O’Brien. O’Brien single-handedly elevated the techniques of three-dimensional model animation to a fine art, beginning in the silent era with short subjects and continuing through the 1925 classic THE LOST WORLD to KING KONG a mere eight years later. As Kong was king of Skull Island, so O’Brien was king of model manipulation, and tike Melies before him, O’Brien never missed an opportunity to add drama, atmosphere or pathos by mixing effects together. Witness the clash between Kong and a flying reptile atop Kong’s mountain lair: Kong and the pterodactyl are jointed foot-high foam rubber models; the mountain’s ledge is a plaster recreation; the sky background is a painting on glass; the flying reptiles in the sky are double-printed eel animation. It was this intelligent and intentional combining of effects that allowed O’Brien to achieve the marvelous sense of reality he did in KING KONG, a reality so intense as to make a thirteen-year-old named Raymond Harryhausen choose the field of special effects animation as his life’s work.

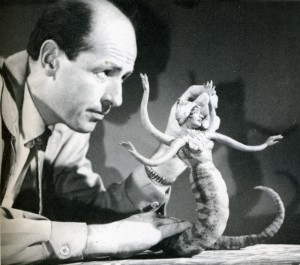

From the time he saw KING KONG in 1933, until the mid-40′s, the youthful Harryhausen animated in what might be called a highly animated fashion.

He even managed, on several occasions, to gain an audience with his future mentor. Though Ray’s fledgling efforts were crude, O’Brien saw in them a promise of future greatness, and he was quick to offer constructive advice to his precocious- protege whenever he was asked. In 1946, impressed by Ray’s solo efforts in producing a series of animated fairy tales; O’Brien offered him encouragement of a more concrete nature: a position as an animator on the Merian C. Cooper production MIGHTY JOE YOUNG. Of this opportunity-of-a-lifetime Harryhausen recalls: “It was, of course, the climax of a long-awaited dream come true. I had a magnificent two-year period of working with O’Brien, during the long pre-production and design stage, up to the end of animation photography. He was so involved in production problems that I ended up animating aboul 80% of the picture.”

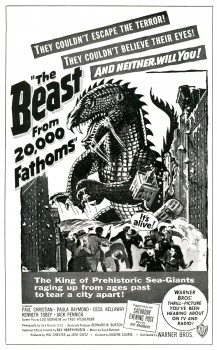

In 1952, as a result of his Oscar-winning work on MIGHTY JOE YOUNG (Best Special Effects of 1949) Ray was approached by Jack Dietz and asked to create the effects for THE BEAST FROM 20,000 FATHOMS. These he executed ably, employing an innovative front-projection system of his own design, as the preferable but more expensive rear-project ion equipment the work called for was outside the boundaries of Dietz’s budget. THE BEAST came in at $200,000, a remarkably low figure considering the expertise and high quality of Ray’s animation and effects. Audiences of 1952 flocked to the picture in droves, making it the unexpected sleeper of the year for Warner Brothers. Completing THE BEAST left Ray on the brink of a long, creatively satisfying and financially rewarding association with a then-youthful producer, Charles Schneer.

In 1952, as a result of his Oscar-winning work on MIGHTY JOE YOUNG (Best Special Effects of 1949) Ray was approached by Jack Dietz and asked to create the effects for THE BEAST FROM 20,000 FATHOMS. These he executed ably, employing an innovative front-projection system of his own design, as the preferable but more expensive rear-project ion equipment the work called for was outside the boundaries of Dietz’s budget. THE BEAST came in at $200,000, a remarkably low figure considering the expertise and high quality of Ray’s animation and effects. Audiences of 1952 flocked to the picture in droves, making it the unexpected sleeper of the year for Warner Brothers. Completing THE BEAST left Ray on the brink of a long, creatively satisfying and financially rewarding association with a then-youthful producer, Charles Schneer.

Schneer wished to produce a script about a giant octopus that terrorizes San Francisco, and after meeting hirn^ {Schneer, not the octopus) Ray agreed to work on the picture. The result was IT CAME FROM BENEATH THE SEA, the first of a series of ten feature films produced by Schneer with special visual effects by Ray Harryhausen. Along the way, Ray has freelanced twice: once in 1958 to animate the dinosaur sequences in Irwin Allen’s THE ANIMAL WORLD, and again in 1966 to handle effects on Hammer Film’s OWE MILLION YEARS B.C.

A comparison of the work of Ray Harryhausen and Willis O’Brien yields some interesting observations. One of O’Briens trademarks throughout, his career was his use of glass paintings. The three-dimensional effect of the jungles of Skull Island was achieved through the painting, on glass, of dense trees and vines. By animating his models behind several layers of these realistic depictions of forest, O’Brien was able to achieve an illusion of depth that added tremendously to the dramatic impact of the entire film. O’Brien was a dramatic romantic, and a stickler for any detail •haqlbuld romanticize. Harryhausen, on •hefOtner hand, is a realist, and in his Jiifork there is a sense of reserve; of a wpjehful eye on the cost of each particular effect. No layers of intricate glass paintings for him—too expensive. For Ray’s purposes a simple but effective matte painting will suffice. The net result is always a little less atmospheric than O’Brien’s work and ultimately less powerful. To compensate for this Harryhausen outshines his master in the fluidity of his animation. His smoothness of movement of his foam rubber creatures is the most striking difference between his and O’Brien’s digital prestidigitation. In this area the pupil could have taught his teacher.

A comparison of the work of Ray Harryhausen and Willis O’Brien yields some interesting observations. One of O’Briens trademarks throughout, his career was his use of glass paintings. The three-dimensional effect of the jungles of Skull Island was achieved through the painting, on glass, of dense trees and vines. By animating his models behind several layers of these realistic depictions of forest, O’Brien was able to achieve an illusion of depth that added tremendously to the dramatic impact of the entire film. O’Brien was a dramatic romantic, and a stickler for any detail •haqlbuld romanticize. Harryhausen, on •hefOtner hand, is a realist, and in his Jiifork there is a sense of reserve; of a wpjehful eye on the cost of each particular effect. No layers of intricate glass paintings for him—too expensive. For Ray’s purposes a simple but effective matte painting will suffice. The net result is always a little less atmospheric than O’Brien’s work and ultimately less powerful. To compensate for this Harryhausen outshines his master in the fluidity of his animation. His smoothness of movement of his foam rubber creatures is the most striking difference between his and O’Brien’s digital prestidigitation. In this area the pupil could have taught his teacher.

The exact processes by which Harryhausen combines his animated models with live actors are ones he prefers to anyone with a basic of animation can grasp the*1 rudiments of what Schneer and Harryhausen have dubbed “Dynarama.” Let us take an example from Harry-hausen’s latest film, THE GOLDEN VOYAGE OF SINBAD. The script called for a battle between Sinbad and a giant one-eyed centaur. The first step in creating the illusion of a human dueling with a mythical monster was to film the actor, in this case John Philip Law, leaping to and fro fighting with an imaginary creature. The resulting footage is loaded onto a rear-screen projector which has been modified to move a frame at a time instead of at sound speed. In front of this rear screen, Harryhausen constructs a miniature set, which corresponds to the full-size one on the film in the projector. Placing his foot-and-a-half tall centaur into this miniature setting, Harryhausen animates it a frame at a time, being careful to similarly advance the rear-projected image of Sinbad. Re-photographing this entire set-up with a locked down animation camera produces the desired effect. This description can only serve to illustrate the bare bones of the Dynarama process. Many sequences have required much more complex techniques of Ray and his equipment. As a result the time element involved in the production of a Dynarama picture is staggering. Pre-production lasts six months to a year. Principal photography lasts several months and the animation photography consumes an incredible year or more! But the results, which speak for themselves, have always seemed to justify the commitment of two or three years of Ray Harryhausen’s life; at least in the past they have.

The exact processes by which Harryhausen combines his animated models with live actors are ones he prefers to anyone with a basic of animation can grasp the*1 rudiments of what Schneer and Harryhausen have dubbed “Dynarama.” Let us take an example from Harry-hausen’s latest film, THE GOLDEN VOYAGE OF SINBAD. The script called for a battle between Sinbad and a giant one-eyed centaur. The first step in creating the illusion of a human dueling with a mythical monster was to film the actor, in this case John Philip Law, leaping to and fro fighting with an imaginary creature. The resulting footage is loaded onto a rear-screen projector which has been modified to move a frame at a time instead of at sound speed. In front of this rear screen, Harryhausen constructs a miniature set, which corresponds to the full-size one on the film in the projector. Placing his foot-and-a-half tall centaur into this miniature setting, Harryhausen animates it a frame at a time, being careful to similarly advance the rear-projected image of Sinbad. Re-photographing this entire set-up with a locked down animation camera produces the desired effect. This description can only serve to illustrate the bare bones of the Dynarama process. Many sequences have required much more complex techniques of Ray and his equipment. As a result the time element involved in the production of a Dynarama picture is staggering. Pre-production lasts six months to a year. Principal photography lasts several months and the animation photography consumes an incredible year or more! But the results, which speak for themselves, have always seemed to justify the commitment of two or three years of Ray Harryhausen’s life; at least in the past they have.

At present Ray is involved in yet a third film about the adventures of the swashbuckling Sinbad, though he characteristically refuses to give details about the project. This is understandable, since at the time we spoke he didn’t even have a story-line. This, too, is characteristic; perhaps unfortunately so. For it is in this area, the script, that Ray’s films have shown their vulnerable underbellies. Starting as they do with Ray’s sketches of the fantastic monsters involved, most Dynarama films are built around a monster or monsters on the loose. Plot, dialogue and characterization have always played second fiddle to special effects in Harryhausen’s films, and this is nowhere as painfully obvious as in THE GOLDEN VOYAGE OF SINBAD. Although his cart-before-the-horse method of scripting has always netted Harryhausen films of a very satisfying financial nature, it has never netted him a film with the impact and scope of KING KONG, and never will. One can only hope that as he has more say in his productions than any effects animator on earth, (he is a co-producer) Harryhausen will one day put as much creative energy into his script, casting and choice of director, as he does into his visuals. Perhaps then the day may yet come when Dynarama films will have some saving graces beyond their impressive opticals. Be that as it may, for anyone at all interested in animation and effects cinematography, the words of the grandmaster of Dynarama paint a fascinating portrait of a seldom glimpsed phase of film production.

At present Ray is involved in yet a third film about the adventures of the swashbuckling Sinbad, though he characteristically refuses to give details about the project. This is understandable, since at the time we spoke he didn’t even have a story-line. This, too, is characteristic; perhaps unfortunately so. For it is in this area, the script, that Ray’s films have shown their vulnerable underbellies. Starting as they do with Ray’s sketches of the fantastic monsters involved, most Dynarama films are built around a monster or monsters on the loose. Plot, dialogue and characterization have always played second fiddle to special effects in Harryhausen’s films, and this is nowhere as painfully obvious as in THE GOLDEN VOYAGE OF SINBAD. Although his cart-before-the-horse method of scripting has always netted Harryhausen films of a very satisfying financial nature, it has never netted him a film with the impact and scope of KING KONG, and never will. One can only hope that as he has more say in his productions than any effects animator on earth, (he is a co-producer) Harryhausen will one day put as much creative energy into his script, casting and choice of director, as he does into his visuals. Perhaps then the day may yet come when Dynarama films will have some saving graces beyond their impressive opticals. Be that as it may, for anyone at all interested in animation and effects cinematography, the words of the grandmaster of Dynarama paint a fascinating portrait of a seldom glimpsed phase of film production.

M.C.: Have you ever considered remaking the film which first inspired you, KING KONG?

R.H.: Yes, but KONG couldn’t be re-made today without spending vast amounts of money. The time and cost involved in doing all those glass paintings would be astronomical. You know O’Brien really developed the technique of glass painting single-handedly. In a way his use of them was a forerunner of Disney’s multi-plane camera. On KONG Obie had animation tables sandwiched between the glass paintings, and on these tables he’d place his models. He needed a tremendous amount of light for the camera to record through all those panes of glass. Often a light would blow in the middle of a scene, ruining a shot he had worked on for days. To remake KONG would be much too complex a thing to get into today.

M.C.: Some hold the opinion that your films have little merit aside from their impressive effects. I don’t mean to criticize, but I tend to agree with that, excepting MYSTERIOUS ISLAND, a Him I feel could stand alone if the footage of the monsters was cut.

R.H.: Really? I don’t think you would feel that way about MYSTERIOUS ISLAND if you actually did cut that footage. Pick up an 8mm version some time and try it. (Laughs) The original Jules Verne novel was really just a tale of survival on a desert island. The survivors in the story saw rather mundane things, so we modified their adventures a bit by adding Capt. Nemo and his giant creatures.

M.C.: With newer and better emulsions now available in 16mm, have you considered working in that gauge?

M.C.: With newer and better emulsions now available in 16mm, have you considered working in that gauge?

R.H.: No, I have no reason to work in 16mm. With 16 you don’t have the options and accuracy of 35mm and the optical printer. Certain subjects might show up quite well on a blow-up from 16, but my work is much too complicated to further complicate it by working in a smaller gauge than 35mm.

M.C.: What about 70mm?

R.H.: We released FIRST MEN IN THE MOON in 70mm, but that was a blow-up from 35. Shooting on a 70mm negative is too costly a proposition, necessitating the use of too many specialized pieces of equipment.

M.C.: FIRST MEN was shot in Panavision. What effect did shooting wide screen have on your usual methods?

R.H.: I was forced to re-design many things, because certain techniques are impractical in Panavision. I relied more heavily on traveling matte work in FIRST MEN, whereas normally I might have used front or rear projection.

M.C.: you are quite active in other areas of production besides animation photography. Have you ever considered directing an entire film?

R.H.: Oh, yes, I would very much like to direct if I find the right subject. But it’s a big job just to keep track of the special effects. There’s a limit to how much one man can do.

M.C.: Didn’t you once remark that you were unhappy with the animation of the miniature horse in THE VALLEY OF GWANGI? If so, why?

R.H.: No, what I did say was that it was a sequence I ‘dreaded doing because the horse really didn’t have anything dynamic to do. It just had to sit there and look coy. It’s always difficult to decide what to have the creature do in scenes like that. An action sequence involving a giant animal is much more impressive. So I let that scene go until last.

M.C.: Box-office-wise your films have usually done quite well. How can you account for the relative failure of THE VALLEY OF GWANGI?

R.H.: It was released at a time when Warners was being sold and it received very poor distribution. There was no advertising to speak of and nobody knew what the picture was about.

M.C.: Alternately, THE GOLDEN VOYAGE OF SINBAD has really hit big with audiences here.

R.H.: You must remember the time when GWANGI was released. Everyone was on a sex binge then, and we only had sexy dinosaurs. Warners didn’t push the picture at all. Columbia, on the other hand, has put a great deal of effort into their campaign for GOLDEN VOYAGE. That and word-of-mouth really paid off.

M.C.: In the past you have utilized the talents of film composer Bernard Herrmann for your scores. Why was he not used on GOLDEN VOYAGE?

R.H.: There were many reasons. Sometimes people are tied up, and sometimes the situation just isn’t conducive to getting the people you would prefer. I think the composer we did use, Miklos Rozsa [SPELLBOUND], writes a different kind of music than Herrmann, and that he did a very good job for us.

R.H.: There were many reasons. Sometimes people are tied up, and sometimes the situation just isn’t conducive to getting the people you would prefer. I think the composer we did use, Miklos Rozsa [SPELLBOUND], writes a different kind of music than Herrmann, and that he did a very good job for us.

M.C.: Taking his past efforts into account, why was Gordon (THE OBLONG BOX) Messier chosen to direct GOLDEN VOYAGE?

R.H.: Again, there were many reasons, and I can’t go into them here. I think Hessler has a very good sense of direction. You must remember that the quality of each picture a director works on depends largely on how much money is in the budget. Some people think we have carte blanche to make a picture any way we please. Except for a David Lean or a Stanley Kubrick, this is not the case. We make a commercial product, and though there are many things we might like to do on a picture, it always comes down to whether or not the money is there.

M.C.: All told, how long were you at work on the effects for GOLDEN VOYAGE?

R.H.: About a year. All the work was done here in London at Gold Hock Studios.

M.C.: Did British Museum sculptor Arthur Hayward assist you in constructing the animation models, as he had on ONE MILLION YEARS B.C. and GWANGI?

R.H.: No, I had others assist me. Molding and casting are very time-consuming jobs, so I farm some of it out to certain individual. I can’t do all the models myself, because I don’t have the time.

M.C.: Do you paint your own matte paintings?

M.C.: Do you paint your own matte paintings?

R.H.: No, I don’t. In fact nowadays I try to avoid using them. There are very few people who can do them well enough so that you don’t have to cut away from them right away. Today it’s practically a lost art, unfortunately. Most of the ones in my other films were done by staff matte painters at Shepperton Studios.

M.C.: I found there was quite a bit of grain in GOLDEN VOYAGE. Why was this?

R.H.: We worked with dupes quite a lot. There are shots in the film where you’re looking at a third-generation dupe, so naturally there’s an increase in grain. Another reason you might have spotted some excess grain was because we printed several optical zones and dolly shots on the printer.

M.C.: What can you tell me about your next film project?

R.H.: It’s called SINBAD AT THE WORLD’S END, and that’s about all I can say. We have a formal company which releases information to the public, and at the moment I’m not at liberty to say anything more. Does that pacify you? (Laughs)

M.C.: Not really. Will John Philip Law again play Sinbad?

R.H.: That depends on his availability, and the characterization in the script, which we don’t even have yet. There have been several Sinbads—Douglas Fairbanks, Kerwin Mathews, Guy Williams. We would like to give him a different quality each time. The irony is that when you knock yourself out to make a picture different, the critics chastise you for not putting in the expected cliches. One reviewer said of GOLDEN VOYAGE that he missed the dancing girls. Now that is a typical Arabian Nights cliche that we avoided on purpose.

M.C.: I have one final question concerning THE SEVENTH VOYAGE OF SINBAD. There is a sequence in that film which depicts Sinbad’s crew walking up the beach loaded down with fruit. There is a black man in the crew, and he’s carrying a watermelon.

R.H.: Oh no…(torrents of laughter at this) only a member of today’s generation would notice something like that. I assure you it was all accidental as to who got what prop.

Thus satisfied that THE 7th VOYAGE OF SINBAD contained no racist undertones, I bid Mr. Harryhausen a fond farewell, leaving his Kensington High Street home for the bleak and foggy streets of London. As I ambled towards the nearest Underground I gave additional thought to the question of Mr. Harryhausen’s responsibility for the over-all quality of his films. Approached on an adult level they are rather silly entertainments. But for a child they create a vivid fantasy world where skeletons come to life and fire-breathing dragons battle with cyclops. I was a child once, and the marvels of Harryhausens monsters, both mythic and imaginary, overwhelmed me. There is a definite place in cinema for this type of film. The adult critical eye must squint a bit to watch THE GOLDEN VOYAGE OF SINBAD, but if that’s not enough, one can always leave the theatre to the little people, whose eyes Ray Harryhausen’s films are created for.

Daily post &Puppet Animation 03 Oct 2008 08:00 am

Lost head

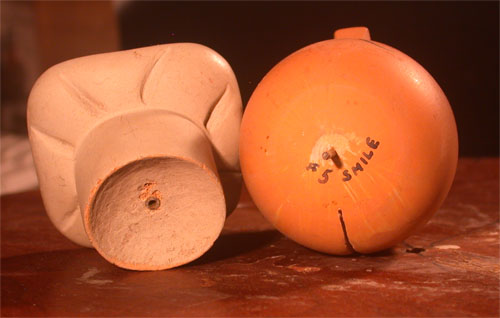

I received this email from NY animator, Willy Hartland. He’d bought a Puppetoon head and is trying to locate the film it comes from.

- I need help authenticating that it’s in fact a Puppetoon head.

It’s clearly a chef character, from perhaps a TV commercial, because

I have yet to find the character on my various George Pal DVDS.

Hopefully someone will be able to identify the character from some obscure short or TV spot.

Underneath the head, is written, “#5 smile.”

(Click any image to enlarge.)

Chef with hat off.

View from below.

When Willy described it to me in Ottawa, I clearly remembered a chef character from one of the shorts, though I couldn’t remember which one. This is definitely the character I remembered, and I still can’t remember the film.

It doesn’t seem to be on the dvd The Puppetoon Movie, though there are a number of shorts not included on that such as: many of the Jasper shorts, or the musical shorts Dipsy Gypsy (a great one), Rhapsody in Wood, or the excellent Dr. Seuss shorts, 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins and And To Think I Saw It on Mulberry Street.

Unfortunately, most of these films are out of our reach and impossible to view.

This face doesn’t look unlike the incidental characters from Tom Thumb, the 1958 live-action/animation film starring Russ Tamblyn. In that movie, there’s an Asian character with an almost identical head.

If anyone has a clue as to which film the head appeared in, please don’t hesitate to leave a comment.

Articles on Animation &Puppet Animation &repeated posts &Trnka 17 Sep 2008 07:31 am

Trnka Graphis revisited

I love Jiri Trnka’s work, and in June 2006 I posted this. It’s worth revisiting.

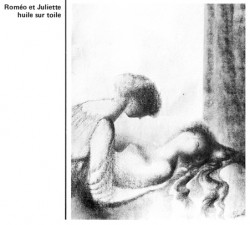

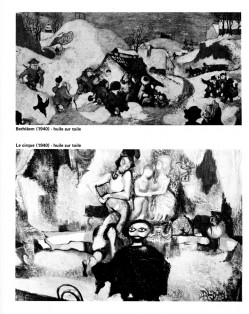

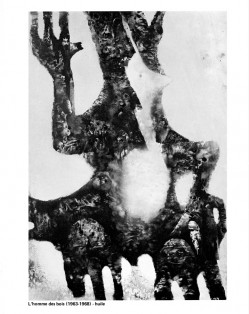

- To continue with my interest in animators that leave fingerprints, I return to the father of all puppet animators, Jiri Trnka. I have this Graphis Magazine article from 1947. This was published before any of the great Trnka films: The Hand, Archangel Gabriel and Mother Goose, Midsummer’s Night Dream.

Regardless, there are still some beautiful images in his earlier work.

(Click on any image to enlarge.)

(Note: Graphis printed in three languages; all of the English is included.)

Commentary &Puppet Animation 22 Jan 2008 09:13 am

Lun Bunin’s Beginnings & Oscar Nominees

- Lou Bunin was born in Russia near Kiev. He received his early art training at the Chicago Art Institute and followed up studying with the sculptor Bourdelle in France at the Academie de la Grande Chaumiere. In 1930 he returned to the US with a one man show at Chicago’s Younge Gallery. This was followed by a year in Mexico where he served as an assistant to the painter, Diego Rivera.

He started a marionette theater in Chicago with the author, Meyer Levin. they produced a version of Eugene O’Neill’s The Hairy Ape and Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus.

In 1938 he collaborated with Charles Bowers on his first film with “stringless” puppets. Petroleum Pete and His Cousins (sometimes known as Pete-roleum and His Cousins). This was a 30 min. movie commissioned by the Petroleum Industry for the 1938 World’s Fair and was directed by Joseph Losey. 12 mins. of the film were animated.

During World War II, he was involved in the production of another stop-motion animated film, Bury The Axis. This film is available in dvd from Steve Stanchfield on his Cartoons For Victory. (I highly recommend this disc. A great collection of truly rare WW II films.) I found this film on YouTube and thought I’d share to celebrate this animator’s beginnings.

– The Oscar nominees were revealed this morning.

The animated features were excellently chosen:

Persepolis

Ratatouille

Surf’s Up

I think you know which one I’d like to see win. A hint – it’s 2D.

Those nominated for animated short include:

I Met the Walrus

Madame Tutli-Putli

Meme Les Pigeons Vont au Paradis (Even Pigeons Go to Heaven)

My Love(Moya Lyubov)

Peter & the Wolf

Peter & the Wolf

I’m quite disappointed that Jeu didn’t make it. Georges Schwizgebel‘s film was brilliant, but the voters didn’t get it, I guess. I’m also a bit surprised the The Pearce Sisters wasn’t nominated. Instead the insipid My Love made it. One could have predicted that, but then I already wrote about this film.

Congratulations to them all, and also to Brad Bird and Jim Capobianco, Jan Pinkava for the nomination for Best Screenplay for Ratatouille. If they win, Jan Pinkava could win after being replaced by Brad Bird.

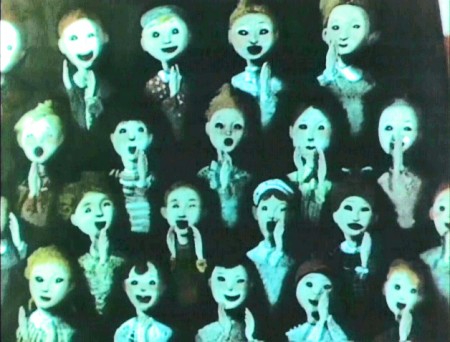

Animation Artifacts &Puppet Animation &Trnka 03 Nov 2007 08:23 am

Trnka’s Merry Circus

– I’ve been a fan of Jirà Trnka‘s work since I first saw it back in the 60′s. I’ve bought every publication I’ve ever found which discusses or displays his films or illustration. These days I can also own a number of his films.

– I’ve been a fan of Jirà Trnka‘s work since I first saw it back in the 60′s. I’ve bought every publication I’ve ever found which discusses or displays his films or illustration. These days I can also own a number of his films.

His puppet films were always the gold standard of that medium. However, since I’ve studied his illustrations for many years, I’m always interested in the 2D work he’s done.

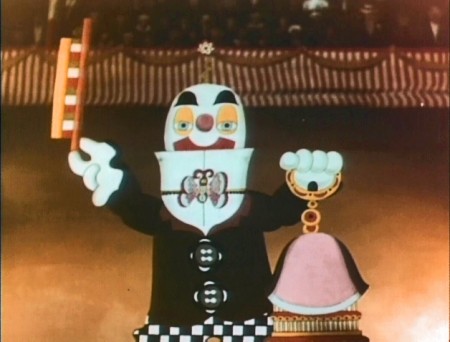

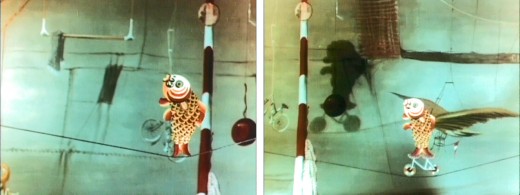

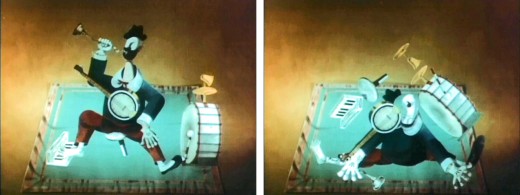

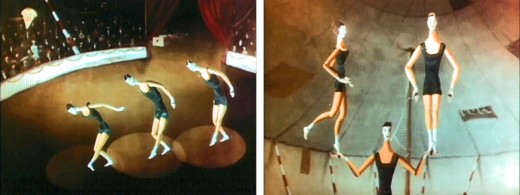

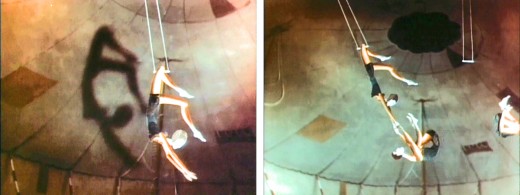

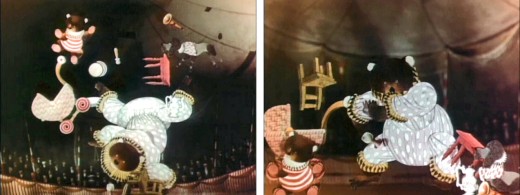

The dvd titled The Puppet Films of Jirà Trnka includes one of these 2D films. It’s cut-out animation, so it really borders the world between 2D and 3D. Trnka exploits the shadows on his constructed cardboard backgrounds to great effect. The style purposefully hides the three dimensions of the constructions, but it uses it when it needs to. The film is a delicate piece which just shows a number of acts in a local circus setting.

It’s a sweet film with a quiet pace. I’m not sure it could be done in today’s world of snap and speed. No one seems to want to take time to enjoy quiet works of art.

I’m posting a number of frame grabs from this short so as to highlight the piece.

Note the real shadows on the background.

These were obviously animated on glass levels in a multiplane setup.

Again, note the excellent use of shadows. It’s very

effective in these long shots of the trapeze artists.

Animation Artifacts &Articles on Animation &Puppet Animation 03 Oct 2007 07:31 am

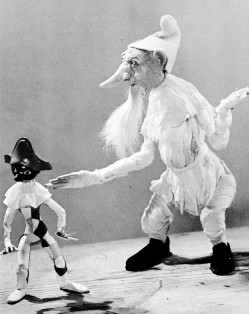

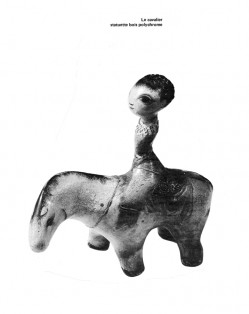

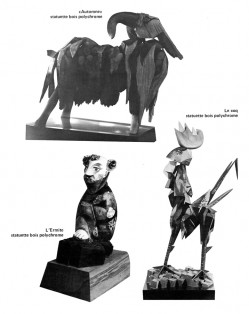

Starévitch

- I’m continuing a small series of lifts from a catalogue I have which features master French animation pioneers. It was a souvenir of a 1981 Parisian exhibition on the history of French animation.

My focus here is one of the greatest stop motion animators in history, Ladislas Starévitch. I’m offering, here, a loose translation of the catalogue entry (with a couple of additions I’ve chosen to add.)

Ladislas Starévitch (1882-1965)

- Born to a Polish family living in Moscow a century ago, Starévitch was an entomologist. When the idea occurred to him to use the technique of frame by frame animation to reconstruct aninsect battle which he’d witnessed, animation entered his life. The film was titled Lucanus Cervus (1910).

So attracted to this conceit of animating his bugs, in the next few years, he made several other stop-motion films before actually beginning a full-time career in animation. This included one of his most famous films, The Revenge of a Kinematograph Cameraman in 1912. The Russian Revolution led to his emigration to France in 1919; this put a temporary halt to his filmmaking. However, a new career began in France when he started to make fiction films exclusively. Assisted by his daughter, Irene, he grew dedicated to 3D puppet filmmaking for the rest of his life.

The Voice of the Nightingale (1923)

Poet and craftsman, as inventive as he was clever, Starévitch created new films including In the Spider’s Grip (1920), The Voice of the Nightingale (1923), and The Eyes of the Dragon (1925), etc. Many technical innovations came from his fertile imagination and resulted in a high level of animation.

Starévitch completed a full-length film (65 mins) entitled The Story of Fox (1930) which found distribution years later (1941) after adding sound to the feature. He lzo created a series with the dog “Fétiche” (1934) as his principal protagonist.

_ __

__

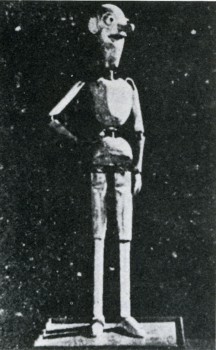

_To the left, an early Starévitch armature from the MOMA collection.

_To the right, a scene from The Story of Fox.

When I was young I had a 16mm print of The Revenge of the Kinematographic Cameraman, and I think I must have watched that print a couple of hundred times. I was absolutely intrigued with the accomplishment he had done in 1912 and felt, then, that it was on the same level as Winsor McCay’s Gertie the Dinosaur.

I’ve seen a number of his films at the Museum of Modern Art and was completely taken with his technique and craft in the film, The Magical Clock (1928) (aka The Little Girl Who Wanted to Be a Princess). The film includes some amazing combinations of Live Action with stop motion animation.

It’d be lovely if some of these films were collected for dvd release in a good quality version. Because many of these films are in public domain, there are a lot of bad, unwatchable copies out there. The official website for Starévitch includes links to some copies of films from Doriane Films including The World of Magic of Starevitch and The Story of Fox. Presumably these might be the best available.