Category ArchiveArticles on Animation

Articles on Animation &Independent Animation 17 Jul 2009 07:40 am

Bob Godfrey Interview

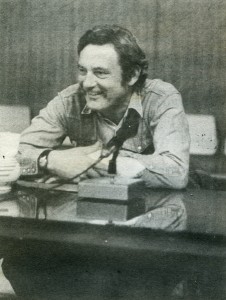

Here’s an interview with Bob Godfrey by John Cannon pulled from Animafilm 2/1979.

John Cannon: What do you think of animation as a specific category of film art? What are its capabilities and limitations?

Bob Godfrey: My answers to it vary with the kind of mood I’m in. It is a very small part of film art and has tremendous capabilities and many, many limitations. One of the reasons for the present state of the industry is that we are not enough aware of the limitations of the medium that we are in. There are lots of things that animation cannot do or shouldn’t do and we seem to be doing them.

Bob Godfrey: My answers to it vary with the kind of mood I’m in. It is a very small part of film art and has tremendous capabilities and many, many limitations. One of the reasons for the present state of the industry is that we are not enough aware of the limitations of the medium that we are in. There are lots of things that animation cannot do or shouldn’t do and we seem to be doing them.

JC: Such as?

BG: The things that live-action handles terribly well like Ingmar Bergman, … personal relationships. In fact live-action is moving into areas that should really be our areas like “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” or “Star Wars”. Animated film should go into the impossible, the fantastic, into the mind of man, because the live-action camera has been literally everywhere it can ___________Bob Godfrey

go on earth — it’s even been to the moon. It’s getting

extremely difficult to amaze people. What cinema has to be into is.

FANTASY AND SPECTACLE. To do spectacular things in animation on a big screen costs a lot of money, a high risk with the decline of the short film, which I lament terribly – the short film is slowly being strangulated by the people who run our business, the distributors. There are no short films exhibited in the principal market, the United States, and very few short films shown here. There’s the old adage “if you want to lose money make a short” and that dies hard in Wardour Street. You can’t get the money to make shorts. Nobody goes to the cinema to see a short – they go to see a long.

So we as animation producers are being forced (if not forced some of us are going willingly) into one of two areas; television with commercials of forced into making longer films, the long feature-length animated film. One has to think very long and very hard before venturing into this area. Judging by the films I’ve heard about or seen recently we are not coming up with the ‘smash hits’ and unless you’re a smash hit your’re nothing; there’s no longer a place for a B feature. We’re not coming up with the ‘smashes’.

So we as animation producers are being forced (if not forced some of us are going willingly) into one of two areas; television with commercials of forced into making longer films, the long feature-length animated film. One has to think very long and very hard before venturing into this area. Judging by the films I’ve heard about or seen recently we are not coming up with the ‘smash hits’ and unless you’re a smash hit your’re nothing; there’s no longer a place for a B feature. We’re not coming up with the ‘smashes’.

JC: Why not?

BG: Wrong subjects perhaps. Perhaps it should be for the children’s market here. Children are catered for by Walt Disney but I don’t know many other children’s producers. I want to make a children’s musical because I think it’s a good idea, because when you’ve outgrown one audience, in another seven years there’s another coming along.

I don’t say that animation should cater solely for children of the family audience. Look at the work of Ralph Bakshi – he works for the young teenage market, the biggest audience we have, the young people who don’t want to sit at home at night.

There’s been a whole spate of animated films recently from the West Coast of America and I don’t think any one of them has really been the

‘smash’. It shouldn’t be to difficult – at least we’ve got to do something to our audience: if we can’t amaze them, perhaps we can still make them laugh, make them cry. You must engage your audience’s emotions and possibly animation is failing in this.

THE ENTREPRENEURS. In animation tend to be the artists — artists in the sense of an artistic background – and perhaps these aren’t the right people to communicate with audiences. One must be a showman first and an artist second, like Disney. He had the great faculty for giving people what they wanted, whereas today there seems the great tendency for self-indulgence on the part of animation producers. It’s what they want first and what the public wants second. It’s a strong temptation for anybody working in animation.

JC: Can animation still hold the audience? BG: Yes, more than anything. We’re just wasting the medium – a sameness is coming over. There’s a tremendous desire to do a quality product after all the conveyor-belt type stuff we’ve had over the last few years.

There’s reaction against that and a strong desire here in London and the West Coast of America to do the quality product. Against that there is the lack of mone’y, the sheer cost of producing an animated film. We’re exploring ways – that’s what “Great” was, an economical way of doing something at the same time as keeping it moving and keeping it entertaining. In these respects it’s successful – it only cost ‘£ 36,00 to make, not a lot for a half-hour animated musical.

It’s good to continue with the musical but we need good stories… maybe animation’ought to be yanked out of art schools and put into drama schools. That would be a start. There are far too m%y artistic considerations and not enough dramatic or story-structure considerations, that is the trouble. We must rethink plus the fact we have no tradition to fall back on.

JC: Has there been no tradition at all? Where do you place the old ‘classics’ of America animation?

BG: The Disney films and Fleischer films came out of the short tradition. The animation house on the side of the big American distributors.

JC: They all had to have a house cartoon?

BG: Yes, Warners, UA and that sorl Everyone on the side of the live-action Out of this came the “Silly Symphonies the longer things. Disney is the only one his place with long animation films. Af Disney moved to live-action which si way he was going anyway; he moved “Jungle Book” which was terrific for me. There was another lull after his death and suddenly came up with “Yellow Submarine.”

BG: Yes, Warners, UA and that sorl Everyone on the side of the live-action Out of this came the “Silly Symphonies the longer things. Disney is the only one his place with long animation films. Af Disney moved to live-action which si way he was going anyway; he moved “Jungle Book” which was terrific for me. There was another lull after his death and suddenly came up with “Yellow Submarine.”

JC: Which was a shot out of the blue?

BG: I don’t think it changed anything at all. It was certainly a milestone. We talk about before “Yellow Submarine” and after “Yellow Submarine”.

A very important and good film but somehow synonymous with swinging London, the Beatles, 1967, 1968 and now it doesn’t seem to matter so much, it’s history. It changed nothing because we all suddenly went back to making things that came before it.

BAKSHI’S HAPPENED – a phenomenon. He has tremendous energy and makes more features than dogs have fleas. He does a great amount of work. He’s now doing “The Lord of the Rings.” All he does is interesting. He’s a fantastic foree in our world, extremely good for the industry. We rush to see his latest films here. He’s taken animation out of the slightly infantile area of pigs in sailor hats and animated nursery-rhymes. He’s made it into the urban nightmare… Look at the New York of “Hoppity Comes to Town” and compare it with, say, “Heavy Traffic” and there’s great sociological comment there. It reveals what has happened to a city in thirty years and what has happened to attitudes. Bakshi has brought animation up to date and one must admire him for that. He’s not had a ‘smash’ yet but I hear amazing stories of “The Lord of the Rings” and it being Bakshi whatever I hear, I believe. He’s the saviour of the West Coast. Box-office success it what it’s all about.

JC: Could critics help animation?

BG: You have drama critics, ballet critics, opera critics. You don’t really have animation critics. This is a great pity. I never see an animated film really criticized properly.

JC: Who could do that?

BG: Someone who knows something about animation. We work in a subject there’s a lot of ignorance about. It’s always handled by the run-of-the-mill film critic. We need an Apollinaire, someone to write about us from the inside, perhaps a failed animator turned journalist… We do need some penetrating analysis right now. Animation, because of animation festivals, is terribly incestuous. At festivals – the only place we meet nowadays — we’re

PREACHING TO THE CONVERTED and in a way the pressures on animation have reduced it to the sort of sameness. The days of the house-style of a few years ago have gone. There’s kind of faceless uniformity about it now.

The advertisers have forced their styles onto us here whereas in the past they had to have our style or leave it. There is still a Disney style, they’re the only ones who can afford it and they don’t make commercials.

JC: Haven’t commercials been of positive use beyond keeping some animators is business? BG: It’s a two-edged sword. On balance it has done more harm than good. Well, they’ve kept us alive. We have to look for alternatives although there are studios completely dedicated to producing animation for commercials who would not want to do anything else.

Halas and Bachelor try to get away. I probably do more entertainment than anyone else in Britain. Richard Williams has his films, “Raggety Ann and Andy”. He built up the Pink Panther tradition too when it was fashionable to have expensive titles. In “Charge of the Light Brigade” the animation said it all, I don’t know why we needed the live action! But financial recession has slammed the door of artistic titles in our faces.

All images are from Godfrey’s film, GREAT.

JC: What doors are opening?

BG: Well, the National Script Development Fund have given me money to work out a package to do an animated feature. I have made a couple of successful animated shorts that prove that you can make money out of them, but I don’t want to keep on trying to prove it. It’s too exhausting.

Having proved it, I’m doing one last short with Vladko Grgic in Yougoslavia which I think will possibly be the best short I’ve been associated with. I’d like to take a

HOLIDAY FROM SHORTS. I’ve done more than most people – and get into the longs. I feel I’m equipped to do it because of the two series which were the equivalent of four hours of animation, a hell of a lot. I’m venturing now into a new area for me. I hope I don’t catch a cold.

One must now think internationally. The film “Jumbo” is set in England and New York so this gives it the transatlantic appeal. The trouble with “Great” was it was so English; no-one understood it.

JC: But it won an Oscar?

BG: It won an Oscar but it’s never been distributed in the States; they’ve never heard of Brunei and they’ve only just heard of Queen Victoria. I blame the distribution system. It’s no good making an animated film unless you have good links with a distributor. JC: But,,Great” was fortunate in Britain? BG: It was fortunate in that it was commissioned by British Lion who subsequently went bankrupt… not solely because of “Great”! You must have the guarantee of distribution before you start anything.

JC: What is it like working in Britain now?

BG:. It’s a bit like Dickens, a best of times and a worst of times. It’s amazing now we keep going. One reason it that British animators are among the best in the world – I say that not to bang the drum or rattle the sabre — I believe that. “Yellow Submarine” helped to bring on a generation of, talented animators, mostly spread out in little tiny companies. I’d hate to see them go down because of escalating costs, rents, etc…

IT’S A TERRIBLE STRUGGLE we have to go on, for some there’s nothing else. We’re attracting more work from abroad – France and Germany. I’m working on “Sesame Street” for Kuwait, Nigeria. Africa is opening up – one door shuts, another door opens. I have to keep my ear to the ground and move with the times. The markets and patterns change all the time, but we are still keyed to the side of the advertising industry.

JC: How should animation be taught?

BG: I teach in an art school one day a week and I am anti-art school and pro-drama school. We must avoid the artistic self-indulgent area. I’m guilty of this too because I financed the films myself and why the hell shouldn’t I?

The cult of the director is something out of Europe — not America where one had the great commercial directors who until recently no-one had ever heard of. In the 1960′s they were re-discovered and the French began saying isn’t Howard Hawks marvellous, which of course he was, or Ford, or Wyler. Nobody said the films were great because they directed them. It was out of Europe that we got the ‘artistic’ film and the cult of the director which has been shipped in animation over to Canada which rarely makes it into the commercial cinema.

JC: Are the new technologies offering any new opportunities for animation?

BG: You mean the great video-tape breakthroughs that are always going to happen? The computer animation that will take over the world? It never happens. Basically it is produced now as BY FLEISCHER ALL THOSE YEARS AGO, equipment’s a lot better and we’re standardizing more. There are more and more animation rostrums in London. Let’s hope they all keep busy.

JC: What about animation and television?

BG: Animation goes into television through commercials and is well paid but animation for programmes is poorly paid and consequently we’re not doing well there. The “Muppets” work — they’ve effected the compromise between instant live action and the sheer labour of animation which makes it impracticable for instant television. Television is instant; animation isn’t. Perhaps the demarcations are natural.

Animation belongs in the cinema where we can afford to labour longer and spend more – for television we can’t produce it fast enough or economically enough.

I’ve never liked puppets very much — I’m not exactly a puppetteer – I love Trnka puppets and Pojar but it doesn’t seem to belong in this country; rather in Poland, Russia, Czechoslovakia where there are such marvellous tradition of puppet work. The “Muppets” however, who grew out of “Sesame Street” are superb, really funny. The “Sesame Street” tradition has helped get work on the small screen. I don’t know how we can solve

the major problem though of the very badly paid area of animation for television programmes. That’s why most of the animation on television is of so low a standard, but what can anyone do with a microscopic budget?

JC: We’ve talked of financial limitations a great deal. What of the other limitations?

BG: Animation is still the art of the impossible; it should concern itself with this but so has live action recently. “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” does this and this is what makes it so mind-boggling. It wouldn’t have been believable as animation as it would lose credibility.

People see animation and do not find it offensive. “It’s a doll” or “it’s a cartoon”. We can make dogs talk. We should deal in imaginative situations. My students don’t really think cartoon. They think live-action and you’ve got to really work on them to think like a cartoonist. A lot of students will have a hand come on the screen and move something. I ask “why the hand?”; it’s simple, acceptable cinematic trick to make the thing move by magic. You must condition yourself to the world of Melies, he was so wonderful because he did tricks.

JC: But your persona is not so much a trickster on screen but an everyday ordinary bloke?

BG: Oh, the Stan Hayward/Bob Godfrey syndrome. Yes, he’s your everyday standard man, with a blown mind. His fantasies are extra-ordinary and this is what I’m doing now. My elephant is ordinary – well he’s not ordinary, he’s the biggest elephant in the world – but his fantasies are amazing. It’s the coming together of the fantasy world and the real world. A mad person cannot differentiate between the two; the two worlds merge. But some people, like “Henry 9 Till 5″ keep fantasy in one compartment and reality in another. I like working with Stan Hayward: he’s one of the few people who’s bothered to sit down and think what animation is all about.

JC: How do animators benefit from film festivals?

BG: The thing about festivals is to realise the background against which those films are produced. How difficult it is for Bruno Bozzetto in Italy? What are the difficulties in Czechoslovakia, Moscow, Yugoslavia? You and I are going to Poland so we’ll find out what things are like there. How do animators function UNDER STATE SUBSIDY? There’s a lot more corning here insofar as a lot of the work I do now is short information films for the Central Office of Information. Does the Canadian Film Board work? – yes, because we get wonderful animators like Caroline Leaf. Without the Film Board a woman like Caroline would not get the opportunity to come through and carry on her experiments. There’s nothing like it anywhere else.

In Britain we’ve got the National Film School now which is supposed to be working well and the London International Film School and the arts schools and colleges. A lot of the people working in London are old student of mine from Farnham and Guildford and are moving in. I suppose one person in three gets fixed up in the industry from school. One minute everybody is working, then the film finishes, and everyone is out of work and a great nebulous mass of people move round trying to get absorbed on other things – like musicians here moving form gig to gig, band to band.

JC: Can you tell us something about your new project, “Jumbo”?

BG: It’s a pilot. If I hadn’t done “Great” I wouldn’t be doing “Jumbo”. HE WAS A BIG ELEPHANT, who was around in the nineteenth century. I don’t make films about the nineteenth century through choice. I seem to get lumbered with them. Other people might say I’ve got a size fixation; the smallest man in the world making the biggest ship in the world and now the biggest elephant in the world.

I read Professor Bill Jolly’s book, bought the film rights and applied to the National Script Development Fund and was very lucky and got allocated the money last August. I’m now trying to get the pilot together. I think you always start by trying to make the film the same way as the one you’ve just finished , so I tried to get the old team off “Great” together again, some times with success. With my films there is a sort of continuity. I always start off with making the last one all over again and somewhere through it changes — thank God it changes, otherwise I’d be making the same film through all over again!

“Great” was made in an incredibly disorganised way because it was the first long film I’d ever made. I have to be organised now because we’re only paid to develop the script. So, for my £10,000, I have to produce a story-board, ten to fifteen musical numbers and lyrics and a screenplay. I’m story-boarding with one of my great artists Anne Jolliffe; music is being done by Johnnie Johnson; Colin Pearson who did the lyrics for “Great” is doing the lyrics. It’s a little bit of the old team but learning from our mistakes in the last one.

It’ll run for seventy-five minutes. We’ve got this awful, almost surrealist fact that the elephant got run over by a train and although I’ve been advised to leave it out as it might disturb children I can’t. I’m haunted by this poor beast’s death and I’ve got to put it into the story whether it kills me at the box-office or not. To me why Jumbo is immortal and famous is not because he was big but because he was run over by the train. I’ve tried to make it as funny as I can and have shifted it up to the front of the film. Death can be humorous, it doesn’t have to be incredibly tragic. One of the great twentieth century phobias is death. We’ve had the sexual hang-up and luckily we’re talking or screwing our way out of that one. Death? Why not? Stan Hayward’s making funny films about death and kids go “bang, bang, you’re dead” all the time. If we keep it at that superficial level and at the front of the film so that the kids don’t get too attached to the elephant I think we’ll get away with it.

It is important Jumbo dies. Brunei dies. I seem to be getting stuck with people who die at the high point of the film. Jumbo gave his name to the dictionary, he is synonymous with everything big, enormous, large and wonderful, It’s the story of a simple, everyday, neighbourly elephant who becomes a star, a world-beater, a blockbuster if you like.

I’m at the story-board stage now. I have a love-hate relationship with this stage of a film, it’s the most difficult part of the film after the story – the rest is just shovelling coal. It’s hard work but THE IDEA MAKES THE STORY and this underlines all I’ve been saying in the interview. If the story’s not right you can do all the most brilliant animation in the world and it’s not going to work. The idea must be right.

by John Cannon

Articles on Animation 16 Jul 2009 07:25 am

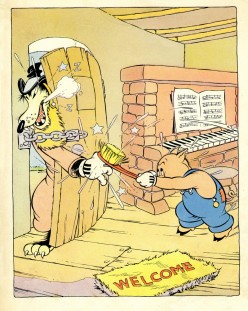

House of Brick

- I found this short piece by E.B.White in a 1933 edition of The New Yorker magazine, and thought you’d find it amusing.

- I found this short piece by E.B.White in a 1933 edition of The New Yorker magazine, and thought you’d find it amusing.

- House of Brick

WALT DISNEY raised his own salary from $150 a week to $200 a week, as a reward for having produced “Three-Little Pigs.” We got that from his brother, Roy Disney, who was in town last week. Roy manages the Walt Disney interests, and is full of figures about the pigs. They, the pigs, have been shown at 400 theatres in New York City alone, far a total run of 1,200 weeks. They ran for eight weeks at the Trans-Lux Broadway theatre, the only picture that was ever shown there for more than one week. It, or they, flashed on the screen one hundred times a week, and about 250,000 people cheered the opus at that one theatre alone. Out of town, the pigs were just as much of a smash, and Walt has received countless requests for further adventures. He doesn’t think he’ll make a series, though: thinks the chances are against his being able to repeat.

The Music Hall gets the credit for having first shown “Three Little Pigs” here, the week of May 25th to 31st, 1933, Pinto Colvieg, (sic) a former newspaperman now working for Disney, gets the credit for the line “Who’s afraid of the big had wolf?” The song was published in September by Irving Berlin and in two weeks had become the second national best-seller, being topped only by “The Last Round-Up.” The Disney staff are just a bit sheep-faced about the pigs, because when Walt suggested the idea, in September, 1932, none of the directors reacted. It seems that, the Disney procedure is, Walt proposes but a director disposes. Not getting any reaction, Walt shelved the pigs. They kept coming up in his mind, though, and he suggested them a second time. Again no reaction. The third time, the reaction came and the pigs went into production.

The Music Hall gets the credit for having first shown “Three Little Pigs” here, the week of May 25th to 31st, 1933, Pinto Colvieg, (sic) a former newspaperman now working for Disney, gets the credit for the line “Who’s afraid of the big had wolf?” The song was published in September by Irving Berlin and in two weeks had become the second national best-seller, being topped only by “The Last Round-Up.” The Disney staff are just a bit sheep-faced about the pigs, because when Walt suggested the idea, in September, 1932, none of the directors reacted. It seems that, the Disney procedure is, Walt proposes but a director disposes. Not getting any reaction, Walt shelved the pigs. They kept coming up in his mind, though, and he suggested them a second time. Again no reaction. The third time, the reaction came and the pigs went into production.

A Mr. Frank Churchill, one of Disney’s 140 employees, took five minutes off and wrote the chorus of the wolf song, It is the first song hit ever to come out of an animated-cartoon studio (and incidentally it always seemed to us to come out of “Die Fledermaus”). Originally the words appeared like this: “Who’s afraid of the big bad wolf, big bad wolf. big bad wolf? Who’s afraid of the big bad wolf? He don’t know from nothin’.” The last line didn’t seem to fit, somehow, and the staff men convened and tried to find a word that rhymed with “wolf,” They huffed and they puffed, but they finally gave up and had the two pigs who sing the song play the last line on their flute and violin.’

Colvieg (sic) was called upon to speak the part of the wolf, and he also did the pig in overalls. Girls from a trio called the Rhythmettes, Hollywood talent, sang for the two jerry-builders. The cost of making a Silly Symphony runs from $18,000 to $30,000; and the pigs were by no means the most expensive to make. Most Sillies gross between $80,000 and $100,000 over a three-year period; “Three Little Pigs,” Roy told us, would probably triple that amount. Walt makes thirteen Mickeys and thirteen Sillies a year. All the profits go back into the business. Two new Sillies are all ready to he sprung: “The China Shop,” to be released in the next couple of weeks, and “The Might Before Christmas,” at Yuletide. The pigs are soon going into the French and the Spanish. We’ll try and get you the words.

Colvieg (sic) was called upon to speak the part of the wolf, and he also did the pig in overalls. Girls from a trio called the Rhythmettes, Hollywood talent, sang for the two jerry-builders. The cost of making a Silly Symphony runs from $18,000 to $30,000; and the pigs were by no means the most expensive to make. Most Sillies gross between $80,000 and $100,000 over a three-year period; “Three Little Pigs,” Roy told us, would probably triple that amount. Walt makes thirteen Mickeys and thirteen Sillies a year. All the profits go back into the business. Two new Sillies are all ready to he sprung: “The China Shop,” to be released in the next couple of weeks, and “The Might Before Christmas,” at Yuletide. The pigs are soon going into the French and the Spanish. We’ll try and get you the words.

The above recapitulation serves to remind us of a grotesque moment in the lobby of the Music Hall when we asked a tall, elaborately uniformed man what time the “Three Little Pigs” would go on. “I assure you I haven’t the remotest idea,” he snapped. This answer didn’t have the familiar Roxy note, and we looked up and saw that the man was a West Point cadet. You got to watch yourself.

And now for something completely different:

Today’s NYTimes includes an article about a short film, Live Music, that was done via the internet utilizing volunteers through a facebook situation. Each volunteer was offered $500 for the finished scene. Sony will distribute the short with their upcoming animated feature, Planet 51.

The article goes on to say that they would like to do a feature film this way. “I certainly see this as a step in the democratization of creative storytelling in Hollywood,†said Yair Landau, the producer of the film.

What we have here is further proof that character animation is dead. Picking up one scene from a film, that you are in no other way connected to, does not give one the opportunity of doing ANYTHING in the way of proper character animation or development. The only profitable thing about this type of filmmaking is that the producer will be making money off the backs of those volunteering to animate for him. He might as easily send the work to India or China (except that there’s a better likelihood that the professionals over there would be able to add a twitch of character animation.) The animation industry seems to have built it’s house of straw.

Animation &Animation Artifacts &Articles on Animation &Disney &Models 13 Jul 2009 07:31 am

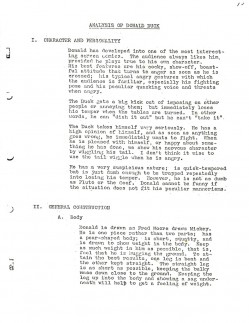

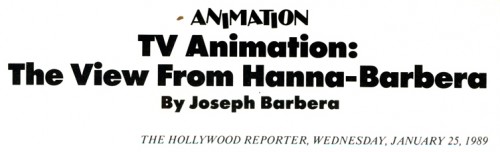

Donald Models

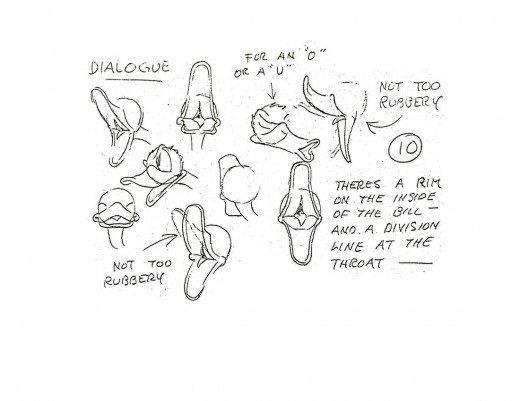

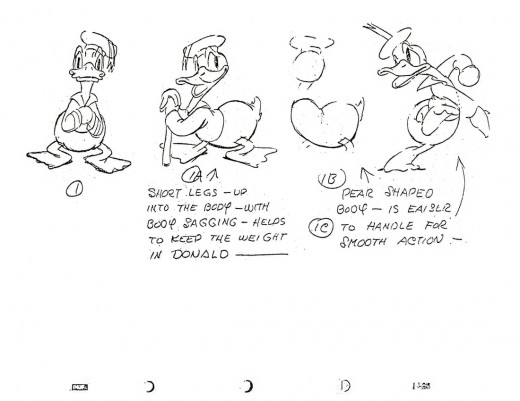

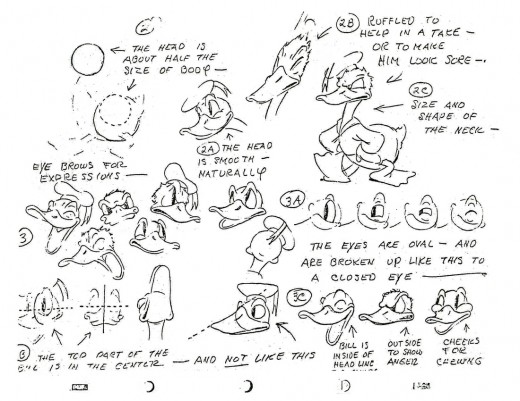

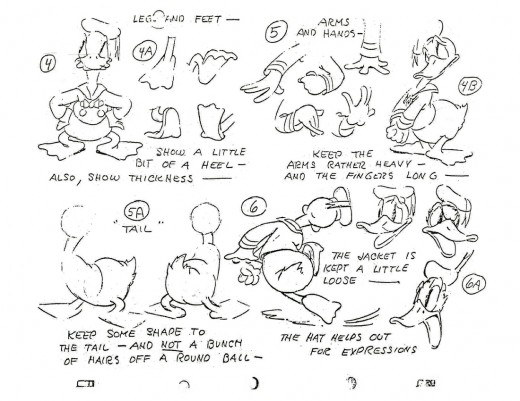

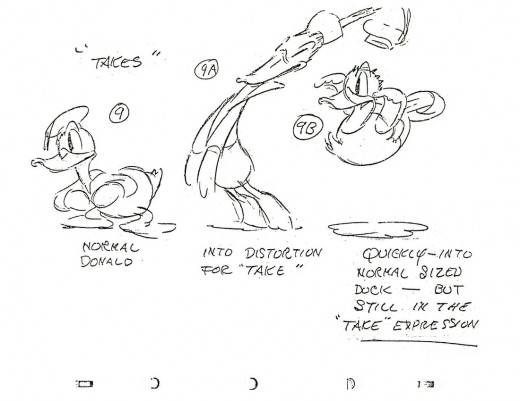

- A few weeks ago I posted the handout sheets that were given at Disney’s in 1938 to advise people on how to draw Mickey. The same was done for Donald, Goofy and Pluto.

- A few weeks ago I posted the handout sheets that were given at Disney’s in 1938 to advise people on how to draw Mickey. The same was done for Donald, Goofy and Pluto.

Here are the notes from the Fred Spencer class analyzing Donald Duck. There’s a lot here that even the Disney studio sees to have forgotten about the Duck. He’s a brilliant and unique character, and he hasn’t been done as well as he was drawn in the 30s.

These same notes appeared in a synthesized and cleaned-up form in Frank Thomas Ollie Johnston’s Illusions of Life. Somehow I prefer the slightly browning mimeo sheets from the studio. (Although mine are just a xerox of same.) These are all worth it for the incredible drawings on the last page.

1

1  2

2(Click any image to enlarge.)

You can see what the actual pieces look like at Didier Ghez’ Disney History site. He posts two pages courtesy of Gunnar Andreassen.

Articles on Animation &Commentary 05 Jul 2009 08:37 am

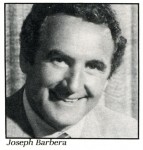

Violence & Joe Barbera

Having posted some photos yesterday for July 4th, let me turn to something animated.

- After seeing Ice Age 3 (or half of it, I had to leave), I began to think about children’s films. The pendulum seems to have swung again. There was a time when Variety and The Hollywood Reporter were filled with articles pro and con cartoon violence. (Violence can be ripping the hair off an animal’s chest or attacking dinosaurs.) Once the networks stopped airing their Saturday morning blocs of programming, no one seems to have taken much notice.

This is an article by Joe Barbera about why he should be allowed to smash Tom in the teeth with a golf ball. (It’s funny!)

I’m posting this as a reminder that there ARE consequences to what we show and tell our children.

Pick a cartoon gag. Any gag. Remember the one when Tom hit a golf ball off Jerry’s ear, only to have it ricochet off a tree and come back dead solid perfect off Tom’s teeth? Or how about the one in which the bad guy drops an anvil off the head of Huckleberry Hound, who shakes it off and wobbles away. Sound familiar? Remember when you were a kid, how you laughed at those? Take my word, you did. But those gags and others like them are only memories now because you won’t see them on cartoons produced today.

Today’s cartoon shows, believe it or not, are not allowed to contain gags of this type. Why, you can’t even throw a cream pie at a character. Explain that to Soupy Sales, who made it into a comic art form that gave us all a big laugh. These visual gags are considered too violent; too extreme; too negative an influence on today’s cartoon watcher.

Today’s cartoon shows, believe it or not, are not allowed to contain gags of this type. Why, you can’t even throw a cream pie at a character. Explain that to Soupy Sales, who made it into a comic art form that gave us all a big laugh. These visual gags are considered too violent; too extreme; too negative an influence on today’s cartoon watcher.

For that you can blame, or thank, depending on your point of view, broadcasters, who have been effectively lobbied by small but exceptionally effective pressure groups. I’m sure they have all the best intentions in the world, but what they may not realize is that they are destroying the cartoon as we know it and diminishing the creativity that has made animation a successful, entertaining medium. Now cartoons are produced using what I call “compromise humor.”

It started a decade, ago when a concerned group of parents and teachers complained that cartoons were to blame for society’s ills. Television personnel took heed of the outcry of a vocal minority and put their collective foot down as to what is and what is not acceptable in today’s cartoon.

Now, don’t get me wrong. I understand everyone’s concern. But I don’t think they fully realize the consequences of these limitations. By placing the same restraints on the animation producers, the material is being flattened out. In other words, the creativity in what we can do is limited. Because the same “rules” apply to us all, there comes a feeling of sameness in all new cartoons produced, which television critics have noted this season. The little touches of style and timing that would separate each cartoon series and production house are not as distinctive as they once were, and that is a shame.

If the same set of rules were around 30 years ago, Hanna-Barbera would have never produced Huckleberry Hound, Yogi Bear, Quick Draw McGraw and the Flintstones as we know them today. What made those shows and others successful was exaggeration — the hallmark of animation. Cartoons are an exaggeration of real life. Cartoons are fantasy and fun. Cartoons are not real life. Cartoons are not the solution to the world’s problems, and it is my belief they should not be forced to pretend they are.

The cartoon is a visual medium, expressing universal humor that reaches all children of every nationality without the need for words. I still don’t know if adults realize that children have different standards as to what is funny and what isn’t.

Again, don’t get me wrong. There are still boundaries of good taste we should adhere to. Hanna-Barbera will never do a cartoon promoting drugs, for example. In fact, we produced a primetime special ABC aired this season called “The Flint-stone Kids, Just Say No.” The White House commended the special, which is now available on home video, with a portion of the proceeds to benefit the Just Say No campaign.

Obviously cartoons should not take the place of the personal guidance of parents and teachers. Situations that are real and factual are the job of schools, mom and dad, grandma and grandpa.

Let’s face it. Kids are not watching cartoons for educational input: They are watching to be entertained. You can’t have a cat chasing a mouse stop to teach it about American history. It doesn’t work. We tried it. We’ve worked with consultants and pressure groups but the kids were bored and turned us off.

Let’s face it. Kids are not watching cartoons for educational input: They are watching to be entertained. You can’t have a cat chasing a mouse stop to teach it about American history. It doesn’t work. We tried it. We’ve worked with consultants and pressure groups but the kids were bored and turned us off.

If children don’t find something that entertains them on television, they pop a cassette of classic cartoons into the VCR and watch them instead.

While my partner Bill Hanna and I are on the road promoting the homevideo tapes we sell, we hear from hundreds of parents who make a special point of telling us how much they love our shows, and trust them. Many parents have confided to me that they are concerned about what their children watch, but think it’s completely safe for their children to watch a Han-na-Barbera show. They confess that they like to watch our shows with their children, but don’t find the cartoons of today very funny. They want to know when we are going to bring our good old ones back.

I think the kids who watch cartoons agree with me. ABC brought back Bugs Bunny and Tweety cartoons to Saturday morning this season. These are not new cartoons. Most of them were made more than 40 years ago, with good old exaggerated gags. The fact that the show is doing well in the ratings suggests that children like these cartoons. But if those cartoons were being produced under today’s strict standards, the same type of humor wouldn’t be there, and I guarantee the ratings wouldn’t be either.

Cartoons are supposed to start where reality ends. If you want to put three heads on a character, you do it. You shouldn’t have to stop and think about who would like it and who would find it distasteful. Something like that works better visually than it will ever sound in words.

We did a successful cartoon series in 1964 called “Jonny Quest.” It was the forerunner to Indiana Jones. It was a family action-adventure series with human characters, not animal characters with human traits. It featured Jonny Quest, an 11-year-old boy, who helped his father battle Dr. Zin and others with futuristic gadgets, lasers and submarines. Now we don’t expect 11-year-old boys to find their neighborhood submarine and leave home, but our watchdogs act as if those things were really going to happen. With the restrictions that inhibit imagination, the Indiana Jones-type entertainment would not be nearly as successful. In fact, if today’s standards were around back in the Golden Days of Television, I seriously doubt if Laurel and Hardy and Buster Keaton would have made it.

Children are entitled to their own entertainment. Today’s children exhibit signs of stress and pressures at younger ages. I would rather they found a release valve by watching cartoons purely for entertainment than be exposed to the sex and violence of primetime programs and the news.

So what is the answer? Let Hanna-Barbera and the other animation producers govern themselves. Let Hanna-Barbera take the experience of seven Oscars and eight Emmys and do what we do best. We know what makes a cartoon funny. We know the boundaries of good taste. Please don’t let “compromise humor” become the standard that governs creativity.

To end this, let me give you the lyrics of a great song by Stephen Sondheim from Into the Woods:

Nothing’s all black, but then nothing’s all white

How do you say it will all be all right

When you know that it might not be true?

What do you do?

Careful the things you say

Children will listen

Careful the things you do

Children will see and learn

Children may not obey, but children will listen

Children will look to you for which way to turn

Co learn what to be

Careful before you say “Listen to me”

Children will listen

Careful the wish you make

Wishes are children

Careful the path they take

Wishes come true, not free

Careful the spell you cast

Not just on children

Sometimes the spell may last

Past what you can see

And turn against you

Careful the tale you tell

That is the spell

Children will listen

How can you say to a child who’s in flight

“Don’t slip away and I won’t hold so tight”

What can you say that no matter how slight won’t be misunderstood

What do you leave to your child when you’re dead?

Only whatever you put in it’s head

Things that your mother and father had said

Which were left to them too

Careful what you say

Children will listen

Careful you do it too

Children will see

And learn, oh guide them that step away

Children will glisten

Tample with what is true

And children will turn

If just to be free

Careful before you say

“Listen to me”

Articles on Animation 30 Jun 2009 07:30 am

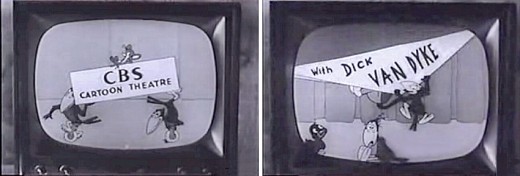

Terry TV

Images from Toon Tracker

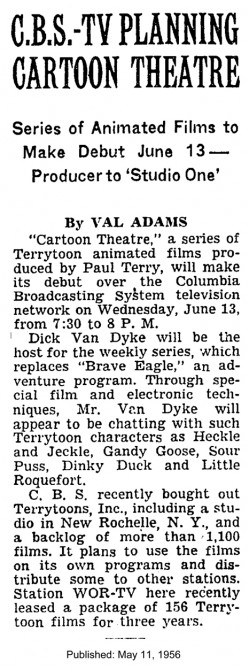

- I can remember somewhat clearly the show on CBS television, Wednesday nights at 7;30 pm, 1956. Dick Van Dyke (a relatively new-on-the-scene comic/dancer whose face was already familiar to the young me) appearing in a cramped living room set talking with Terrytoon characters on B&W TV.

CBS Cartoon Theatre – It wasn’t something worth rushing to see, but for a cartoon crazed youth who maneuvered the television set to anything approaching animation, it would certainly do. They screened a lot of late-thirties/early-forties shorts. Li’l Roquefort and Sourpuss, the Terry Bears and Gandy Goose were the stars of these animated “gems.” Mind you this was before The Mighty Mouse Show (pre-Ralph Bakshi and John K version) on Saturday morning. This was Terry trying to do what Disney had done at ABC on Wednesday nights at 7:30.

CBS Cartoon Theatre – It wasn’t something worth rushing to see, but for a cartoon crazed youth who maneuvered the television set to anything approaching animation, it would certainly do. They screened a lot of late-thirties/early-forties shorts. Li’l Roquefort and Sourpuss, the Terry Bears and Gandy Goose were the stars of these animated “gems.” Mind you this was before The Mighty Mouse Show (pre-Ralph Bakshi and John K version) on Saturday morning. This was Terry trying to do what Disney had done at ABC on Wednesday nights at 7:30.

You can watch the opening of an episode of this show here.

Sorry, it wasn’t good enough, and the show disappeared quickly. It ended up only a Summer replacement.

here’s a NYTimes announcement of the upcoming program.

(Click any image to enlarge to read.)

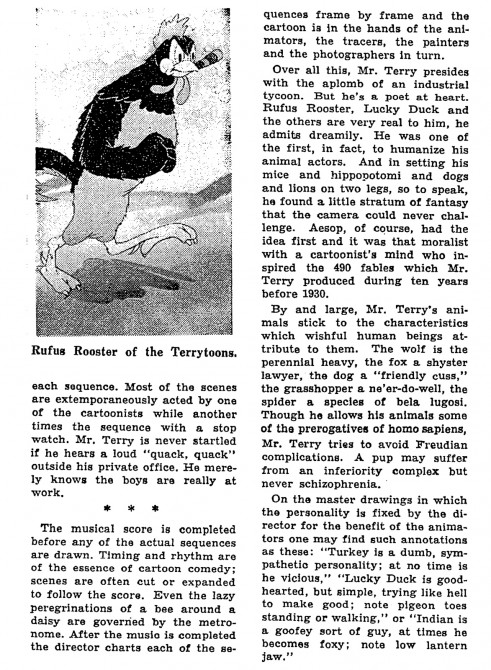

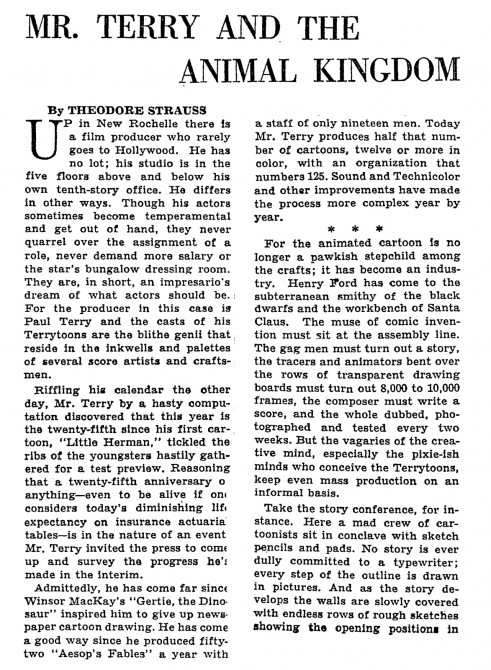

Here’s a more elaborate NYTimes article from 1941 about Terry’s barnyard stable of characters:

pt 1

pt 1

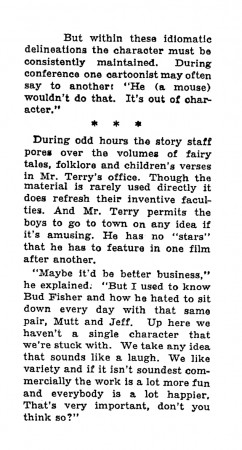

And here’s an article from the Times in the waning years of the Terrytoon studio, 1961

pt 1

pt 1

Articles on Animation 16 Jun 2009 08:52 am

Journal of Int’l Animated Film 2

- Last week, I posted a short piece on British animation in 1957. This came from a Journal that was released (in the days before ASIFA) on the International state of the animated film.

- Last week, I posted a short piece on British animation in 1957. This came from a Journal that was released (in the days before ASIFA) on the International state of the animated film.

The Journal coincided with the “first International animated film festival in Britain” at the National Film Theatre during February and March 1957.

They screened some 150 films, including 12 of the 31 features produced to that time.

The hope for the festival was to encourage theatres to include animated shorts on their programs again. The art form was dwindling. At that time, no one saw television as the panacea it would become.

This document gathered seven different writers and filmmakers to write about the state of animation in the respective countries.

AT THE Cannes Film Festival in the spring of 1956 I overheard a ticket taker remark to a puzzled tourist who evidently had tried unsuccessfully to get into the premiere of one of the full length feature presentations, “II y a aussi des petites dessins-animes.” Judging from the tone in which he spoke, half condescending, half affectionate, his words seemed to imply “tough luck, but as a consolation there are some little cartoons to be seen if you care to have a look.” He was referring to the International Festival of Animated Films which was taking place at the same time in another part of the cinema Palais. His attitude was similar to that of the general run of movie-goer everywhere. The cartoon is usually considered a

pleasing little hors d’oeuvre to be enjoyed along with more substantial fare. That this hors d’oeuvre is welcome is apparent in the little murmurs of anticipated delight which still run through most audiences when the faces of Pluto, Mickey Mouse or Mr. Magoo come on to the screen. It is as though the audience realizes that for a few minutes they will be spared the sensational horrors which so often appear in the newsreel, or the tired cliches of a third rate travelogue. With the cartoon the audience can enter into a realm of pure fantasy, in which the laws of gravity are nonexistent, where pain is not pain and where characters become symbols or stereotypes, not to be taken very seriously.

pleasing little hors d’oeuvre to be enjoyed along with more substantial fare. That this hors d’oeuvre is welcome is apparent in the little murmurs of anticipated delight which still run through most audiences when the faces of Pluto, Mickey Mouse or Mr. Magoo come on to the screen. It is as though the audience realizes that for a few minutes they will be spared the sensational horrors which so often appear in the newsreel, or the tired cliches of a third rate travelogue. With the cartoon the audience can enter into a realm of pure fantasy, in which the laws of gravity are nonexistent, where pain is not pain and where characters become symbols or stereotypes, not to be taken very seriously.

The audience which strayed in to see the animated films at Cannes (the tickets were free) bore little resemblance to the self-conscious, publicity hungry international set which attended the gala openings of the longer features. The cartoons were attended by the producers themselves, a motley crew from every corner of the earth, and casual spectators from the streets, curious and unprejudiced. It was interesting to watch the reaction of this audience to films which ranged all the way from animated folk tales of Texas to heavy political propaganda from both sides of the iron curtain. The actor who drew the most spontaneous outburst of laughter was that ageless veteran whose career has remained unchanged throughout the years, Mr. Donald Duck. His frustration in the film which so delighted the audience was caused by his ineffectual efforts to fall asleep in spite of a relentless neon light which kept flashing off and on, and the insistent sound of dripping water from a tap which gradually increased in his imagination until each drop seemed a bomb visibly shaking the whole earth with rhythmic concussions. Donald’s frustration, seemed on that afternoon in Cannes to be such a note of understanding which reached across the

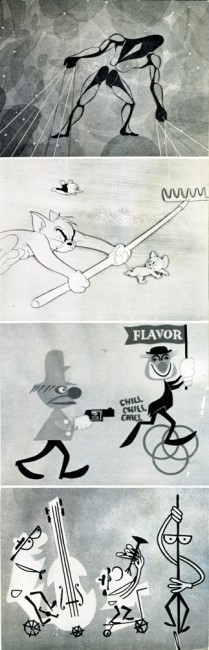

To Your Health, Tom & Jerry________barriers of language and nationality. This particular

Balentine Beer commercial,_________film was, as always with Disney, elaborately anima-

Winston Cigarette commercial_______ted, no economy tricks employed, no corners cut.

_______________________________The sound track with its metamorphosis of dripping water to world-shaking “booms” was imaginative and appropriate to the medium. Also, like most of Disney’s films, it was a sample of the usual over-cute style with background drawings similar to the easiest kind of commercial advertising.

It is impossible to consider the animated film in the United States without thinking first of Disney. After 30 years his name is still synonymous with the short cartoon in the minds of most of the American movie-audience. Sometimes during the long period since his first exciting Silly Symphonies appeared, the work from his large organisation in California seemed to have sunk into the doldrums. Formula replaced invention. The medium lost its initial public appeal. Disney’s excursions into the field of “live action” have been sometimes rewarding, sometimes disappointing. Some of the wild life films have recaptured the excitement of his early cartoons, while the romantic historic costume pieces have often seemed banal. Always a clever  showman, he has recently built a large fun fair, or amusement park in California which serves also as a setting for television programme material. When, from time to time, a new feature length cartoon appears, such as Lady and The Tramp, in which the chief characters are dogs, one is amazed at the technical slickness of the animation and annoyed by the weak story line, which seems to be influenced by the wish to include every sure-fire box-office trick. This approach does not lead to any fresh experiments within the medium.

showman, he has recently built a large fun fair, or amusement park in California which serves also as a setting for television programme material. When, from time to time, a new feature length cartoon appears, such as Lady and The Tramp, in which the chief characters are dogs, one is amazed at the technical slickness of the animation and annoyed by the weak story line, which seems to be influenced by the wish to include every sure-fire box-office trick. This approach does not lead to any fresh experiments within the medium.

It was the short film Gerald McBoing-Boing which first brought a radical change of style to the attention of the public in America and soon after to the cinema-goers in Europe. This highly original short film, produced by U.P.A. Pictures, with finely integrated music by Gail Kubik and with sophisticated visual elements, seemed to satisfy a public at that time weary of the Disney formula. The talented minds which produced “Gerald” had made previous cartoons in which visual wit and economical animation had replaced the elaborately evolved techniques established by the larger studios, but these films had never been seen in the theatres. Some of the U.P.A. men had worked previously in the Disney Studios. The organisation under the leadership of Stephen Busustow has now expanded into the field of television. Robert Cannon, one of the most brilliant U.P.A. directors, brings a fertile imagination and fresh approach to each new film he creates. Another director, Pete Burness, who has been with the U.P.A. since its early days, has created a now popular cartoon character, Mr. Magoo, whose blithe innocence and near-sightedness leads him unscathed and unconcerned through the violence of the modern world. Mr. Magoo, like Donald Duck, has become a beloved international personality.

The U.P.A. style, according to their own spokesmen, derives from “modern” art. It is uncluttered, flat and often linear. The characters do not seem bound by any natural physical laws of movement. Perhaps one of the greatest contributions of the U.P.A. is that they have shown the public that the less realistic a movement is, the more creditable it becomes optically. Disney sometimes bases the movement of his characters on live action models, as with Alice in Alice in Wonderland. The greater the effort to imitate realistic movement, the more apt one is to be aware of the stroboscopic nature of the medium, the more jittery the result. If legs are used to express the symbol of walking, rather than the imitation of walking, the illusion of movement is more acceptable, a paradox which indicates the validity of the “modern” art approach. Like any device this simplification can be carried too far. If the human figure becomes too abstract it may lose all its expressive power. Usually the U.P.A. figures, moving flatly on a flat screen are consistent, humorous and convincing.

Magoo Beats the Heat , Madeline

Less effective have been certain of the U.P.A. attempts to animate the drawings of “big name” illustrators, such as Thurber and Bemelmans. The Unicorn in the Garden and Madeline are examples. Since the quality of both Thurber’s and Bemelmans’ drawings depends on a subtlety and unevenness of line which is impossible to use in the animation technique, where every celleloid must have an almost mechanical similarity, the flavour of the original is lost and the result is far less successful than the work of lesser known artists, whose training within the film medium has taught them its restrictions.

Nevertheless, the U.P.A. has been a healthy influence in the United States. The proof that a new style has had its effect on Disney and his imitators is seen in their efforts to modernise their own productions. Disney has released a short history of music called Whistle, Toot, Plunk and Boom, which seemed to imply that if his studios wished, they too could work in the “modern” style. The popular M.G.M. films, with incredibly fast pacing and surrealist gags, seem also to have cancer research or democracy. Which does not mean that good films cannot be made on these themes. But there is little chance for the individual to produce a genuinely experimental film on his own subject.

It is difficult to say what the future of this medium in the U.S. will be. At present animation is still popular in the entertainment fields and in commercial television. Some of the most imaginative uses of animation at present are in one-minute TV commercials. Animation is in demand in those sponsored industrial films where a mechanical concept can be shown more clearly than it can in live-action. Animation is also useful in industrial films which try to express abstract ideas or fantasy.

Donald Duck, in his better movements, still communicates to an international audience. It would be interesting to speculate, however, as to what animation might have been if Disney had not had his enormous influence. In the first place, animation might not necessarily have been only cartoon. The simplest visual element, a dot, or a line, can become a dancing symbol and convey an idea, an association. These ideas could be developed with other means than by conventional story telling. The film need not always be based on a literary concept. It could be, for the spectator, an experience like seeing dancing, or hearing music. Within the medium not only new forms, but new ways of expression could be evolved. The animated film need not always be a pastische, a sequence of gags or a fairy tale. It could be a powerful medium. It is condensed and potent. Like most potent things, it is better in small doses. But in a brief time it can pack a terrific punch. In the end its possibilities are limited only by the imagination of the filmmaker.

Articles on Animation 11 Jun 2009 07:46 am

Journal of Int’l Animated Film

- In 1957, the British Film Academy, directed by Roger Manvell, published a short “Journal” which included reports from a number of writers around the world talking about the animation industries in their respective countries. Somewhat similar to the ASIFA International Bulletins we receive quarterly.

- In 1957, the British Film Academy, directed by Roger Manvell, published a short “Journal” which included reports from a number of writers around the world talking about the animation industries in their respective countries. Somewhat similar to the ASIFA International Bulletins we receive quarterly.

Needless to say, these are all outdated pieces, but there’s some entertainment (at least) to be gathered from reading these reports. The first, naturally enough, came from Great Britain and – appropriate to the times – is Halas & Batchelor-centric.

All of the essays talk about the effect UPA has had on the medium, most particularly Phillip Stapp’s report of the USA. (I’ll probably post that one next week.)

Here’s the state of England in 1957:

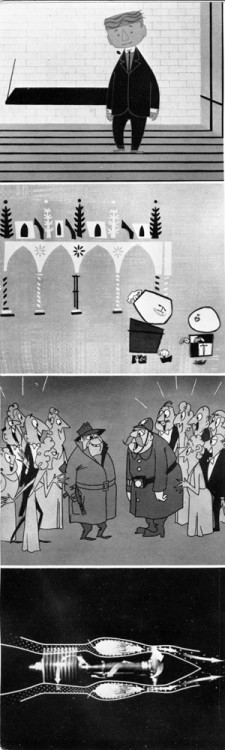

IN America, most animation work is linked with the major studios. Tom and Jerry come from the M.G.M. studios, Popeye from Paramount, Tweety Pie from Warners; even the U.P.A. unit works under the general umbrella of Columbia, whilst Disney’s is almost a separate major studio in itself.

IN America, most animation work is linked with the major studios. Tom and Jerry come from the M.G.M. studios, Popeye from Paramount, Tweety Pie from Warners; even the U.P.A. unit works under the general umbrella of Columbia, whilst Disney’s is almost a separate major studio in itself.

In Britain, animation is a family business, operating in the style of the medieval craftsmen’s guilds. The Units tend to stay together in small communities, usually in converted houses or tiny offices. Personnel grow up with their production companies, often entering the business direct from University or Art School. Training is done by experience, as the young learn from the old in the day-to-day work at the animation tables. There is a struggle to maintain continuity of production. Leadership is based on the personality of one or two people who often manage the whole operation as a kind of family concern, imposing their style to a degree which they themselves would scarcely admit, for many strive to encourage as much individual experiment as possible amongst those who work for them.

The Units are divided into four main categories. First, there are the groups who produce sponsored films but, because they have been in existence for a long time and have established some measure of independence, are able to conduct occasional experiments that lead to theatrical distribution, or even to produce films specifically for the entertainment market. Halas and Batchelor Productions are a Unit of this kind.

John Halas came to this country before the War, having worked in Hungary with George Pal; Joy Batchelor first met him in London and shared in the making of animation films, both here and in Budapest. They married and now operate the company under joint control. Like most British Units, they depend on sponsorship of various forms for their existence. This comes from three main sources:

Mr. Finley’s Feelings, Earth is A Battlefield, __1. Official Bodies, Government Departments

Britvic Commercial, The Gas Turbine. ______or International Authorities.

_____________________________________Examples of films made recently in this category include To Your Health, for the World Health Organisation: Basic Fleetwork, for the Admiralty; The Sea, for the Ford Foundation; and The Candlemaker, for the United Lutheran Church in America.

2. Sponsorship through Industry. Recent films include: Power to Fly, for the British Petroleum Company, and Invisible Exchange for Shell.

3. Direct Advertisments, made now mainly for Commerical Television. Halas and Batchelor made the famous Murraymints series, as well as a special series for Dunlop.

Using the resources gained over years of work in the “bread-and-butter” business, Halas and Batchelor have been able to amuse themselves (and very large cinema audiences) with such pictures as their delightful History of the Cinema, which was chosen for the Royal Film Performance in 1956. Of a more serious character was the feature length Animal Farm, a rare example of an attempt to use the cartoon film for the interpretation of a complicated political satire. The Unit that made these films is now ninety strong; it is run personally by John Halas and Joy Batchelor, both of whom are active at every stage in the making of the films as well as handling the complicated business problems that arise in sustaining the flow of the sponsorship so essential to their continued existence. The shaping of spiralling movements around little twirls of Matyas Seiber’s clever wood-wind orchestrations in well-known tunes is characteristic of their work, as well as a love of perky, bouncing little men who tackle everything from Income Tax forms to oil-well drilling with a gay, impertinent but pleasing confidence.

Halas and Batchelor produced the first feature-length cartoon in this country (Animal Farm), the first stereoscopic experiment in animation (The Owl and the Pussycat), and the first major puppet-animation production (Figurehead). Ever since their formation in 1940, they have remained completely independent of any financial links with other organisations.

The second type of Unit in Britain is that devoted entirely to sponsored work, but taking full advantage of the chances offered them by enlightened business concerns to experiment. The William Larkins Studio, operated by Geoffrey Sumner and Theodore Thumwood, was started in 1942 under the name of Analysis Films. It became part of the Film Producer’s Guild in 1947 and, as Larkins Studio, has since produced about 820 short animated films. There are seventy people in the Unit, which turns out about 30,000 feet of final-cut material a year. Personnel tends to remain static, and the Unit’s tradition in training can be gathered from the fact that, on a recent prize-winning film, the average age of the production team was 23.

As in the case of Halas and Batchelor, :ertain of their films have broken through to he theatrical field, although they have not so ~ar made films except to order. Men of Merit, “or example, was shown in some 3,000 cinemas in this country alone; 602 copies were printed by Technicolor. The studio’s style is still, perhaps almost unconsciously, influenced by the work of Peter Sachs, notably by his angular figures, clear-cut lines and sharply-defined backgrounds, in which detail is reduced to a minimum. Earth is a Battlefield, their current production, has a clever extension of the technique in a series of disjointed, cut-out figures which perform to a sound track in the rhyming style of Enterprise, an earlier film by Peter Sachs.

The third main type of animation Unit is exemplified by Nicholas and Mary Spargo’s group at Henley-on-Thames. Formed to produce material specifically for Commercial Television, the Unit now consists of eleven people working in a large room over a shop in the centre of the town. Following the well-established pattern, there are already two trainees in the group, working on the fifteen, thirty- and fifty-second commercials for which the Unit was set up. Because they are lively and imaginative, work flows at a fast pace; Nicholas Spargo spends much of his time on the business side at the moment, while his wife is usually to be found in the studio. Both gained their experience in the tough school of the David Hand Unit at Cookham.

In addition to the independent units, there are a number of small animation groups in Britain attached to certain large organisations like the Shell Film Unit. Francis Rodker and a small team of specialists have been producing excellent diagrams and animated sections for the Shell Unit since its formation in 1935. Three animation cameras are in use, each producing about 4,000 feet of exposed film a year.

A Short Vision, Down a Long Way

Finally, there are the experimental groups, whose status borders between professional and amateur. Typical is the case of Joan and Peter Foldes, who produce animated films in their own home in Edgware. Peter Foldes, like John Halas, came to London from Hungary; he met his wife here and they now work together on all their films. Animated Genesis, their first film, was made on their own resources up to picture rough-cut stage. It was then shown to the British Film Institute, who persuaded Sir Alexander Korda to see it; he completed the sound track and gave the picture distribution through British Lion. A Short Vision, the six-minute story of an artist’s impression of the world destroyed by nuclear fission, was also made as a private venture in the beginning; it was completed with the help of the British Institute’s Experimental Production Fund, and later shown on American television.

The personal quality of British animation films derives from the struggle for independence, the imprint of a beneficent sponsorship and the style of those who founded their own groups and continue to run them. The system is not without drawbacks. Experiment, especially in subject matter, is always subordinate to the needs of the sponsor. Full public screenings are the exception, however delicate the advertisement. The Units are too busy with their own work to indulge in large-scale publicity. They have to contend with the fact that the major circuits are, by-and-large, completely deaf to their work. By contrast many European countries encourage the work of their animation units.

In spite of these difficulties, British animated films have won many international awards. These films are being used increasingly in the United States, both in the cinemas and over television. The battle for a screening is being won at long last; in every country, except Britain.

Articles on Animation 09 Jun 2009 06:45 am

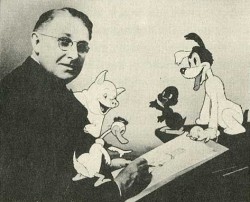

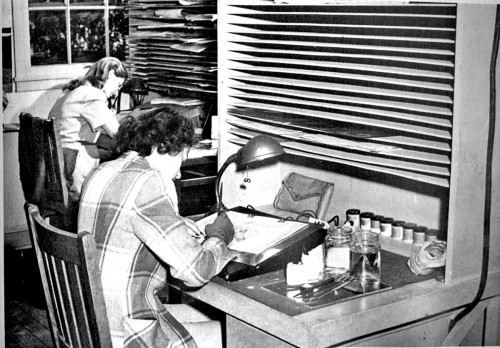

Working for Lantz in the ’30s

- 22 years ago, “The Walter Lantz Conference on Animation” was held in LA. There were numerous gatherings and talks about animation on a few sunny days in LA. I got to meet a number of fine people there, but, in my usual shy manner, stayed a bit to myself. I did enjoy the event. I can’t remember going out specifically for that, but I was there just the same. My memory is a bit shaky about it. I know there were other conferences that I didn’t make.

A publication, The Art of the Animated Image was an Anthology that was published by AFI and edited by Charles Solomon. Writers such as John Canemaker, Cecile Starr and Donald Crafton wrote for it. The late, great Leo Salkin wrote this short piece which I thought might be interesting to some folks who haven’t seen it.

in the 30′s

A Reminiscence

BY LEO SALKIN

I went to work for Walter Lantz on March 3,1932. At that time he was producing Oswald The Lucky Rabbit cartoons for Universal Pictures. It was my first job. I had had an interview with Walter a couple of weeks earlier; he reviewed my portfolio of cartoons, drawn while I was at Hollywood High, and on the basis of that interview he hired me. It was the era of Prohibition, bathtub ginjohn Held, Jr. drawings, and the Great Depression. I was to be paid $17.50 a week, which seemed to me an enormous sum.

My duties were to wash cels, help in camera, learn to ink and paint, practice inbetweening on my own time. There was no training program: You picked up what you could as .you went along. During that time economic conditions were bad and getting worse, and while you were trying to learn how to ink and paint and flip animation drawings, you were never free of the fear that this job couldn’t last and that at any moment Universal might decide that they didn’t want any more cartoons and the animation department would be closed down. They were scary times but fortunately Walter managed well and we kept going.

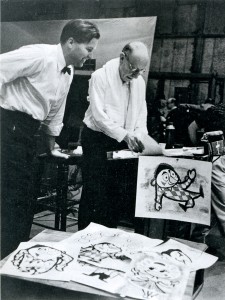

Walter Lantz at his drawing table, Universal Pictures, 1928.

In time, I learned how to animate a walk cycle, a run, a squash and stretch action, and something about the mystique of the exposure sheet and animation timing. After awhile I became a pretty good animator. And somewhere along in there I learned about gags. As a matter of fact, there was no way you could have avoided learning about gags: They were the life blood of the place.

What I value most about having worked for Walter in those years is what I learned about gags. The work days in the studio consisted of two major activities: one was making animated cartoons; it was the primary reason we were there, and it was the basis of our livlihood. The second activity, only slightly less important than the first, was drawing cartoon gags of each other. That; was a big thing. And it took place simultaneously with the production of the films. What was remarkable about the situation is that Walter not only tolerated and accepted it, he, at times, contributed and took part in it. And despite the horseplay, production schedules were met and budgets were contained.

It would be absurd to describe the atmosphere of the place as playful—that’s too refined—it was a funny place. It was a place of gags. The physical environment in which we worked influenced the kind of gags that were played. The animation building was a one-story structure. One side had windows running the length of the building. The interior was divided down the middle by a seven-foot high partition. The ink and paint girls were on the side by the windows—they provided a big part of the audience— and the animation department on the other side was in semi-darkness. It was the semi-darkness that seemed to have nurtured the particular kind of nuttiness that took place.

Inking and painting tables, Universal Pictures.

There were the physical gags like filling a small paper envelope-type of cup with water then pinning it to the bottom side of your animation board so that it slowly dripped on to the crotch of your pants as you were sitting there drawing. Tnere were the eraser gags in which someone would place a piece of rubber eraser on top of the hot light bulb under your animation disc and then wait eagerly for you to become aware of the stench that was enveloping you: There were the hot-foot gags—in fact that was the era of the hot-foot. Most of the guys smoked. Everybody carried matches. The room was in semi-darkness. The entire under-structure of the desks was open: four legs and a cross-piece to put your feet on. Perfect set-up.

And the imbecility went on endlessly. Then there were the belching gags—a standard after-lunch performance: A very loud belch. Voice in the darkness, “Are you okay?” Second voice, “Yeah, I think so.” “You didn’t tear anything, did you?” “No, I’m okay.” “You want some water or something?” “No thanks, but thanks anyway.” “Okay.” Finally, there were the so-called practical jokes which were plentiful, at times painful, embarrassing, humiliating and stupid.

Now we come to a special category which 1 treasure: the personal cartoon gags and caricatures. They were indigenous to the animated cartoon studio. Everybody in the place could draw. The ability to draw was almost a cheap commodity. The personal cartoon gag was the dominant form of communication; people expressed what they felt and observed in cartoons. Anything that happened during the course of the day, however trivial, was potentially the basis of a cartoon. The event could be blown up out of all proportion to what had actually occurred; it could be seen as ridiculous, absurd, pathetic, idiotic, or whatever. The gags were sometimes tasteless, crude, vulgar and obscene,but they generally got laughs.

To analyze why this provided so much pleasure—at least to everyone but the butt of the joke—would require another reading in the psychopathology of humor, and I’d rather avoid that. I think the guys wanted to have fun, to find relief from the boredom of flipping animation paper all day long.

The ability of the artists to create a strikingly recognizable likeness of whoever they were cartooning was extraordinary. Whatever was characteristic and unique about any given person

would be pounced upon, exaggerated and burlesqued, and combined with some personal incident, made a continuing source of cartoon gags and caricatures. Sometimes the way they drew you

would be embarrassing, “My God! I don’t look like that, do I?” And the only person youieould turn to for consolation was Robert Burns:

“O wad some power the giftie give us

To see oursel’s as ithers see us!”

We were granted that.

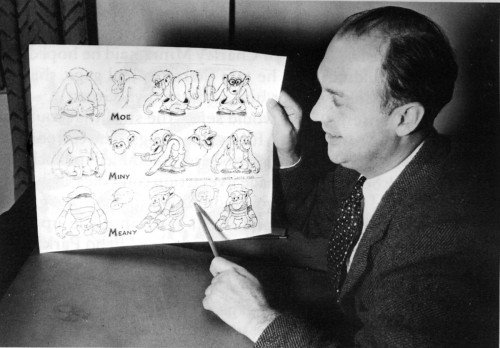

Walter Lantz with a model chart.

This brings me to that stage of development in which I began to learn something about the nature of gags, their structure and function in film. In the early ’30′s Walter Lantz didn’t have a story department. Walt essentially put the stories together with the contributions of a number of people who had shown an ability to think funny and to come up with gags for the films. The way it worked was this: first a subject was chosen: Oswald Camping Out or Oswald at the North Pole or a take-off on King Kong; then a notice was put up on the bulletin board asking those interested to turn in gags; this was followed by a story meeting. The guys called into the meeting were people who had turned in gags—at that time I remember there was Tex Avery, Cal Howard, Jack Carr, me, a few of the key animators, and Walt.

A story meeting, for those who have never attended one, was an extraordinary experience. The prevailing atmosphere was a mood of What the hell, it’s okay to say anything that comes to mind, what’s important is getting laughs. The out-going, extroverted, comic naturals had a hilarious time. For some of us to whom this was unfamiliar territory, the uninhibited, right-off- the-top-of-their-head-shouters were a bit intimidating. There was a lot of talking and laughing and making jokes. Sample joke: in one story meeting I remember Jack Carr, an inveterate punster, who had previously worked for Charley Mintz, said he hoped the Lantz group wouldn’t think he was there to steal gags, that he hoped they wouldn’t consider him a Mintz spy. (Groan).

Out of the nonsense Walt would select the stuff that could be made into a film: comedy bits, funny lines, gags. The cartoons of that period were still being concocted and assembled in much the same way Mack Sennett had made live-action comedies: “Charlie, there’s some kid auto races going on down in Venice—grab a cameraman, go down there and see if you can come up with something funny.” Or, “Hey! They just drained Echo Park Lake, it’s all mud, that oughta be funny as hell!” That’s what we did. We took a locale, an occupation, a situation, or the basic premise of a popular feature and did a lot of gags, strung them together, built in a chase, and got out in under seven minutes.

There was no market testing, or who is our target audience, or will a sponsor buy this? Come on, fellas, it’s just comedy. Get some laughs. Walter was the judge. What he thought was funny was what got up on the screen.

Story meetings despite all the laughter and kidding around had a lot of emotional tension running through them and you had to enjoy doing story to be able to cope with them. Bill Nolan, who co-directed with Walt, was one of the great innovative animators of the late 1920′s period, and he disliked working on story. In fact he hated it, and most of all he hated puns.

We were having a meeting with Bill on a story that Tex Avery, who was then the key animator on the Nolan unit, wanted to develop. It was to be based on a popular song of the period. “I Found a Million Dollar Baby in the Five and Ten Cent Store.” There was the usual amount of banter and gossip and making jokes and Bill was getting increasingly restless, irritated and annoyed. Then someone made a casual remark about how you could sure get some good buys in the dime store, and at that point Jack Carr, the pun man, said, “Right! I mean everybody knows that whatever you get at the five and dime is Woolworth every cent you pay for it!” That did it. The last straw. Bill Nolan jumped up, lunged at Carr and had to be forcefully restrained from punching him out.

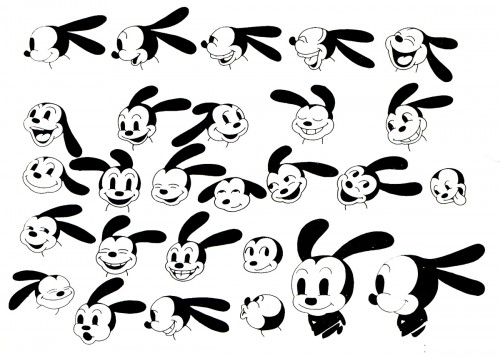

Model chart for Oswald The Lucky Rabbit, 1928.

The dynamics of a story meeting were instructive: You were in a competition to be funny, to get laughs. Your mind was totally involved—the right hemisphere, the left hemisphere, the conscious, the pre-conscious, and the unconscious—all trying to come up with that funny bit that would get a laugh. And suddenly you got it. “Wow! Wouldn’t it be funny,” you’d say to yourself, “if Oswald did this and then he did that and then he…” And then you’d stop. “Damn! That’s a gag I saw Chaplin do. I can’t suggest that. I didn’t think it up. That’s stealing.” And right at that moment, somebody else would jump up, say exactly what you were going to say and everybody would laugh and say, “Terrific! Hey, that’s funny!” And you’d be sitting there thinking, “I can’t believe it. Don’t they know that gag was already done by Chaplin or Keaton, or by Harry Langdon or Harold Lloyd?” It was but that was totally irrelevant.

What you had to learn was that it didn’t matter a damn that a piece of business, a comedy bit, a gag, had been done before, and who had done it. Those gags were like common currency, coin of the realm. They belonged to whomever thought of them. And a good memory for gags could be a valuable asset. What made a gag yours was the way you did it. Talented comics made the old stuff look new, mediocrities made it a bore.

You learned your craft as a gag man by doing gags, getting them in a picture, then going to a preview—imagine previewing a cartoon—at the Alexander Theater in Glendale and seeing if they got laughs. There was something ludicrous about the experience, in that the intensity of your emotional involvement didn’t seem justified by the actual event: screening a cartoon. Nobody went to the theater to see a cartoon. At best it was an amusing filler till the feature came on. Big deal. But here you are, sitting there in a cold sweat waiting for the film to unwind, waiting to see if your gag got a laugh. All you’ve got is one gag in the picture. Nobody in that entire theater knows you did it, or even gives a damn. You wait. The gag comes on. If it got a laugh you were ecstatic. Exhilarated. You just sat there in the dark and beamed. If it didn’t get a laugh the failure was personal and embarrassing. “Damn! How could I ever have thought that gag was funny?”

That’s the way it was. A gag got a laugh or it didn’t. The audience was live, there were no laugh tracks to fall back on. There was Walter Lantz and the studio, and you went back to the drawing board and tried again. And again and again.

That was my initiation into the world of cartoons. Walter made that possible. I felt privileged to be there. I used to be delighted when someone I had just met asked me what I did, and I could say,

“I’m in animation—you know, animated cartoons.” Then I would hand them my card which said, “Oswald Cartoons, Universal Pictures,” and there in bright orange, black and white was a smiling Oswald pointing directly to my name.

Articles on Animation &Festivals 20 May 2009 07:45 am

1st NY World Animation Festival

- Back in 1972, a month after I first started my initial job in animation, New York hosted the First NY World Animation Festival.

I had never been to a Festival of any kind before, and it intrigues me, as you might imagine. There were quite a few world famous animation figures that actually came to town to present their films, talk to other animators and shine.

This was an event that was created by the entrepeneur, Fred Mintz. All I knew of him was a joke Tissa told me. She, a Hungarian, said that Fred was a Roumanian, and the old story was true: if you went into a revolving door behind a Roumanian, you should check your wallet when you come out. Of course, this was a joke, and Fred turned out to be a nice guy who put a lot on the line to get this notion of a NY Animation Festival up and running.

In fact, there were three annual editions of this fest, and I went to all. I met quite a few famous International animators by just showing up.

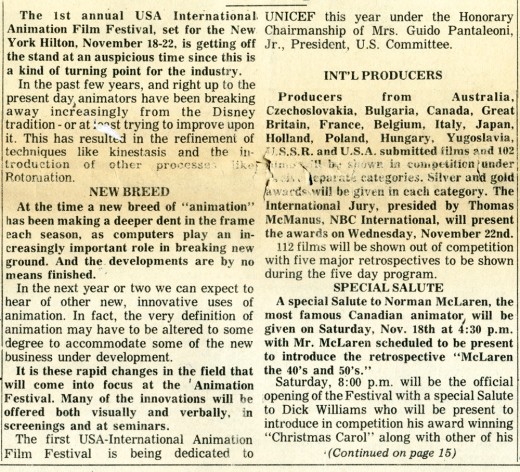

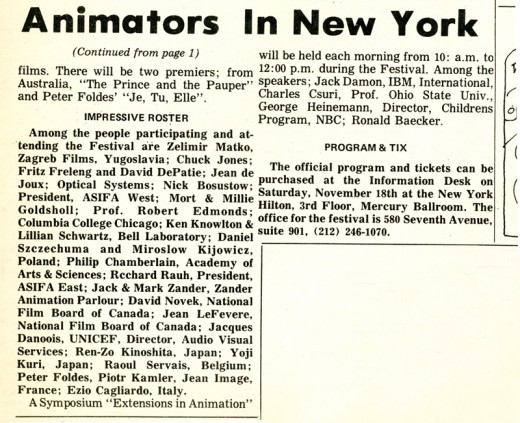

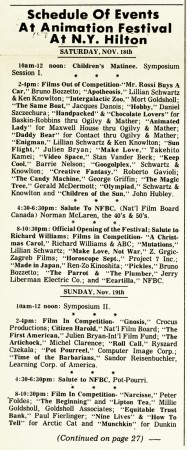

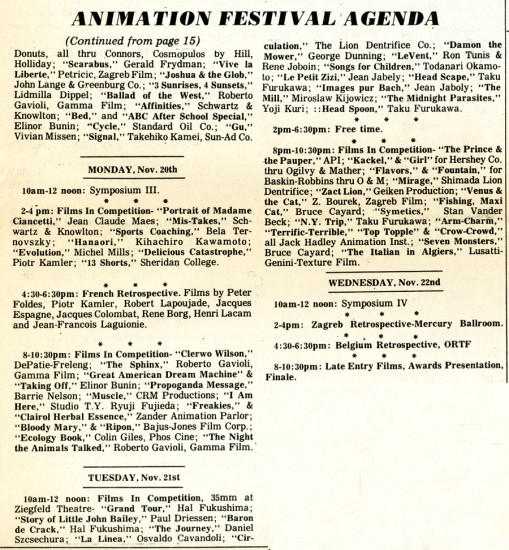

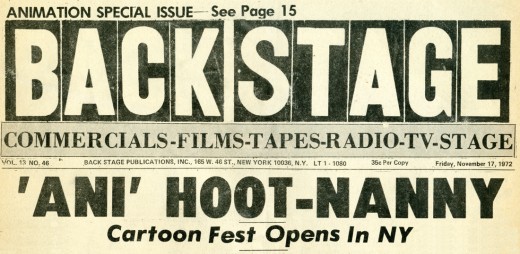

For some reason, I haven’t been able to locate the program for this first festival (I do have those for 2 & 3), but I found this article in Backstage, which was a commercial Industry newspaper. I’m posting the cover story from this issue and hope it will be a some interest.

(Click any image to enlarge.)

.

.

This was the first time I met Bruno Bozzetto, Yoji Kuri, Millie Goldscholl, and many others. I have to say that I didn’t meet a lot of New York animators. At the time, people in the industry stayed away from such events. The older Paramount/Terrytoons crowd wasn’t interested in animation outside of work.

I did meet up with a few of the more art-interested people like Tissa David (who I had just met at Hubley’s), Lu Guarnier, John Gati and a few others.

The events were well attended. Not as many students as there are today, but there were some.

Articles on Animation 12 May 2009 07:54 am

Wilson, Pigs, Orson, and Igor

- Another thoughtful letter from the estimable Borge Ring

-