Category ArchiveArticles on Animation

Articles on Animation &Disney 08 May 2009 08:04 am

Into the Future, Past

- Back in the 80s things were starting to perk up in animated features. After a long stretch of nothing but garbage, the people at Disney started taking the form seriously, and others followed suit.

I love posting old articles that have no relevance to anything anymore, but they’re worth viewing to see how seriously we take ourselves. This is an article written by the excellent LA writer, Charles Solomon, for The Hollywood Reporter‘s animation issue: Jan. 25, 1989.

.

.

Animation Features Thrive

BY CHARLES SOLOMON

Since his death in 1966, various artists have tried to assume Walt Disney’s technical and aesthetic leadership of animation. Although no one has matched the breadth of Disney’s vision, the art form is thriving at the studio he founded nearly 70 years ago. With almost 400 artists at work, including 41 full-fledged animators, the animation division of Walt Disney Pictures is larger now than it ever was during his lifetime.

When the new management team took over the company in 1984, they announced plans for an ambitious rogram that in cluded production of a new, fully animated feature every 12 to 18 months. Disney had hoped to institute a similar schedule during the late ’30s, but the box-office failures of “Fantasia” and “Pinocchio” and the outbreak of World War II disrupted his plans.

When the new management team took over the company in 1984, they announced plans for an ambitious rogram that in cluded production of a new, fully animated feature every 12 to 18 months. Disney had hoped to institute a similar schedule during the late ’30s, but the box-office failures of “Fantasia” and “Pinocchio” and the outbreak of World War II disrupted his plans.

“I’m confident that we’ll be able to continue producing one new animated feature a year,” says Peter Schneider, vice president of feature animation at Walt Disney Pictures. “Quality versus speed is an issue we always wrestle with, and a sensitive one with the artists and myself. We continually struggle to find that balance.”

The first feature made entirely under the new leadership was “The Great Mouse Detective” (1986), an unpretentious and entertaining film that chronicled the adventures of Basil of Baker Street, a Sherlock Holmesian mouse. (Most of the work on “The Black Cauldron,” 1985, had been done under the previous administration.)

“Oliver & Co.”

The climactic confrontation between Basil and the archvil-lain, Ratigan, took place inside the clockwork mechanism of Big Ben. Computer graphics were used to create a three-dimensional world of gears and cogs, while the characters were animated by hand, an exciting example of the possibilities offered by mixing media. “Oliver & Company” (1988) included 11 minutes of computer animation of backgrounds and objects.

‘Rabbit’ Sets a Standard

The most innovative and imaginative animated film of the ’80s was the Touchstone/Amblin co-production, “Who Framed Roger Rabbit.” Directed by Bob Zemeckis, the film set a new standard for combining animation with live action and became the most successful film of 1988, grossing more than $150 million in its domestic release.

The popularity of the film led to a spate of character merchandise, and Roger appeared at the Disney theme parks and at many of the events celebrating the 60th birthday of Mickey Mouse. In the fall of 1988, the studio announced it would produce at least one “Maroon Cartoon” short starring Roger Rabbit and Baby Herman, and there were widespread rumors that a sequel was in the works.

“As it was in the past, the goal of the animation department is to create characters that live beyond their movies,” says Schneider. “With Roger, we’ve certainly created a character who’s entered the American lexicon: For the first time we’ve created a new character that has the potential to become a Mickey Mouse. I think you’re going to see a lot activity over the next five years for Roger: Over time, we hope to build him into a character as big as Mickey.”

“Obviously there’s been talk about a sequel to ‘Roger Rabbit,’ but the project really is in the talking phase right now,” adds animation producer Don Hahn. “A lot of people would like to do a sequel, but we’re still trying to recuperate and evaluate the plans for Roger. Sure, it’d be great to do another one, but it’s just too early to say.”

The success of “Roger Rabbit” has tended to overshadow “Oliver & Company,” a feature based loosely on Dickens’ “Oliver Twist.” The title character became an orphan kitten in contemporary New York City, and Fagin’s gang of pickpockets was transformed into a pack of stray dogs led by the super-cool Dodger. The upbeat tone, broader, cartoon-style animation and celebrity vocal cast (including Billy Joel, Bette Midler and Cheech Marin) placed the film in the tradition of “The Jungle Book” (1967) rather than “Pinocchio.”

The success of “Roger Rabbit” has tended to overshadow “Oliver & Company,” a feature based loosely on Dickens’ “Oliver Twist.” The title character became an orphan kitten in contemporary New York City, and Fagin’s gang of pickpockets was transformed into a pack of stray dogs led by the super-cool Dodger. The upbeat tone, broader, cartoon-style animation and celebrity vocal cast (including Billy Joel, Bette Midler and Cheech Marin) placed the film in the tradition of “The Jungle Book” (1967) rather than “Pinocchio.”

“Oliver & Company” opened in November 1988 to favorable reviews (in Time, Richard Corliss called it “the snazziest Disney cartoon since Walt died”) and good business. The film earned a very respectable $20 million in the first four weeks of its domestic release.

Disney’s next feature will be “The Little Mermaid” in late 1989. The writers have lightened the melancholy tone of the original Hans Christian Andersen story, and added seven songs by Howard Ashman and Alan Menken (“Little Shop of Horrors”). Previewed animation from the film looks impressive, and the animators are excited about their work.

” ‘Little Mermaid’ is definitely on track for Christmas of ’89,” says Schneider. “I think the quality of animation is up sub stantially from anything we’ve done before. You have to realize that we have a very young staff — most of the people real ly started animating on ‘The Great Mouse Detective.’ They got through that experience, then jammed through ‘Oliver’ learned some more in the process, and have now hit their stride as artists.”

Many of the top artists from the international crew who animated “Roger Rabbit” in London joined the Disney staff in Glendale and went to work on “Little Mermaid” when the production ended. This influx of artists helped to bring the animation staff to its current record level.

Building the Animation Staff

“It takes a long while to pick uf the particular subtleties that define a Disney animator,” observes Schneider. “The artists from London are extremely good animators, but they’re a little more accustomed to working in a more Warner Bros./Tex Avery style. Animators like Tom Sito, Chuck Harvey and Nik ‘ Ranieri are really starting to come along and I think they’ll hit their stride on the next picture. But for now, it’s our older artists — Glen Keane, Mark Henn, Reuben Aquino — who are really pulling this picture through.”

Slated to follow “Mermaid” in 1990 is “The Rescuers Down Under,” starring Bernard and Bianca, the mice from the popular comedy-adventure “The Rescuers” (1977). Although the Disney artists sometimes reused characters from the features (e.g. Jimiiny Cricket), “Down Under” represents the studio’s first sequel to an animated feature.

“We’ve never done a sequel before, but I think the appeal of the Bernard and Bianca characters justifies the departure,” says Schneider. “I think the film is going tosurprise a lot of peo pie with its warmth, its heart and its comedy. We’ve found a new setting and added some new characters: Jake, the kangaroo mouse; a really great Disney villain, McLeach; and his sidekick, Fenton.”

“Down Under” will be directed by two supervising animators from “Oliver &, Company,” Hendel Butoy and Mike Gabriel. (Butoy did the key animation of Tito, the hyperactive Chihuahua; Gabriel designed the characters and did animation of both Dodger and Oliver.) The decision to promote two of the studio’s best animators to director indicates that the pool of well-trained young artists remains small.

“I would say the biggest difficulty we face in the industry is finding experienced, qualified directors for our animated projects,” says Schneider. “We don’t see the kind of talent we’d like on the outside, so we’ve been taking staff artists who understand the Disney way and giving them the opportunity to fcdirect Disney pictures.

“I would say the biggest difficulty we face in the industry is finding experienced, qualified directors for our animated projects,” says Schneider. “We don’t see the kind of talent we’d like on the outside, so we’ve been taking staff artists who understand the Disney way and giving them the opportunity to fcdirect Disney pictures.

“Promoting from within does ^nean we’re robbing our core animation group to get directors,” he continues. “But I think having an artist like Hendel directing helps the animators improve: Everyone he worked with on ‘Oliver’ took a leap forward. I hope the same thing will happen as he and Mike direct ‘Down Under/ that they’ll bring the staff a notch further, and more than replace the animation they might otherwise do.”

“The Rescuers Down Under” will be followed by “Beauty and the Beast,” tentatively scheduled for 1991. The film is currently in preproduction, and experimental animation will begin in early 1989. Studio veteran Mel Shaw has done inspirational artwork for the film, and Schneider and Hahn agree that his handsome pastel drawings have set the style for the film and excited the animators about it.

To supplement the new features, Disney will continue to reissue its early classics. A special rerelease is planned for “Fantasia” in 1990 to mark the 50th anniversary of its premiere. For the occasion, the original Sto-kowski soundtrack is being restored with digital audio technology to replace the new soundtrack that film conductor Irwin Kostel and a pickup orchestra recorded in 1982.

“I think a lot of people have forgotten that ‘Fantasia’ really was a creative collaboration be tween Leopold Stokowski and Walt Disney,” says Hahn. “While the Kostel score was a great effort, you can’t retrofit something that was so tightly put together at that time. We’ve gone back to the original camera negatives, and when you see the film again, it will be in all its original splendor.”

A Force in TV

Disney has also become a force in the television cartoon market: The studio began producing Saturday morning animation in Japan with “The Wuzzles” and “Gummi Bears” in 1985. “The New Adventures of Winnie the Pooh” debuted on ABC in 1988. “DuckTales” (1987) remains the most successful cartoon show in syndication, and another syndicated series, “Chip and Dale’s Rescue Rangers,” is scheduled to debut in fall 1989. (The generally high quality of the Disney TV cartoons is balanced against the egregious live action/animation specials made for the studio by Joie Albrecht and Scot Garen.)

In April, Disney will open a second animation facility in Orlando, Fla., as part of the Disney/MGM Studios. A staff of approximately 90 artists will animate the classic Disney characters — Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, Goofy, et al. — in a series of featurettes. The first film in the series will be either “Mickey’s Arabian Adventure” or “Mickey and the Emperor’s New Clothes.”

“The Florida studio is both exciting and extremely difficult,” says Schneider. “Six of our top artists are going there to head the staff; we’ll fill the rest of the positions with people from various schools and professionals from around the country. We’re hoping to expand both the need and the opportunities for young animators, which will only help us in California.”

The artists’ offices in the new building have glass walls that will enable visitors on the studio tour to see how an animated film is made. Jerry Rees (“The Brave Little Toaster”) is directing a series of short live-action/ animation films that explain the animation process. Robin Williams, Walter Cronkite, Walt Disney Co. chairman Michael Eisner, Roger Rabbit and Mickey Mouse provide the narration.

As he considers the possibilities of the expanded production facilities and schedule, Schneider grows thoughtful. “It’s my goal that each time we do a picture we get better at the craft of making movies,” he concludes. “I think the group of people that includes myself, Jeffrey (Katzenberg), Roy (Disney) and the animators really has the opportunity to set the agenda for animation for the next 50 years, as the older group of artists set it for Walt’s generation.” -k

Charles Solomon’s next book, Enchanted Drawings: A History of Animation in America, will be published by Alfred A. Knopf in fall 1989.

As a followup sometime, I’m planning to post an extremely long article from the NY TImes Magazine about the Bluth rebellion away from the Disney mainstream. It’ll take a while to put together.

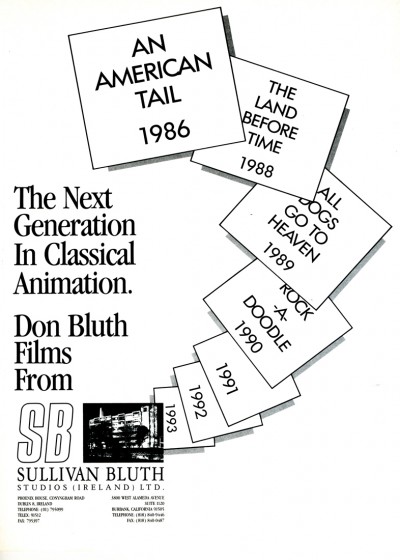

For now, here’s an attractive ad from that very same issue of The Hollywood Reporter.

Articles on Animation &Festivals 02 May 2009 07:48 am

ASIFA East Fest

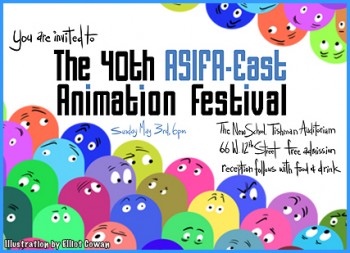

- Tomorrow, Sunday May 3rd marks the 40th anniversary of ASIFA East’s annual festival.

A couple of hours worth of films will be screened in the New School’s auditorium at 66 West 12th Street. Immediately thereafter a party will be celebrated in an adjoining room of the school.

This has always been the big event of the New York animation community, and everyone’s encouraged to attend. The only admission requirement is a pleasant demeanor.

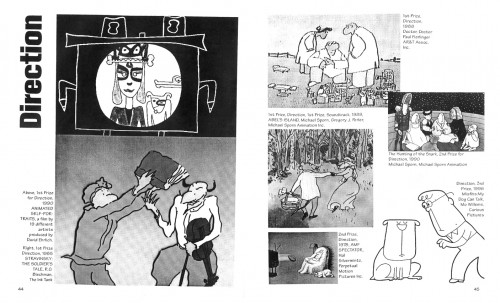

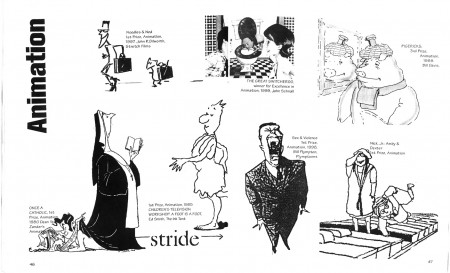

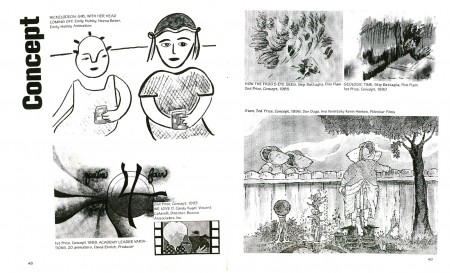

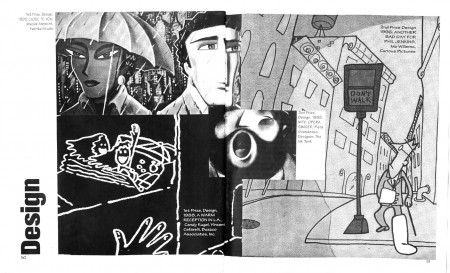

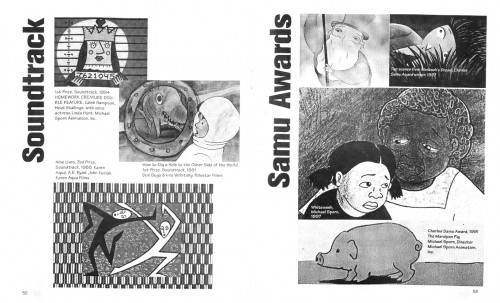

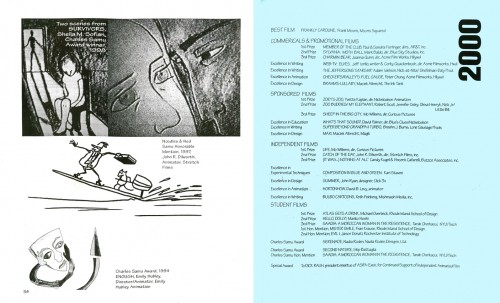

-Back in the year 2000, ASIFA East, celebrating their 30th Anniversary, produced a book outlining the history of their festival. All of the award winners over all of those 30 years were listed, and a lot of images featured some of the highlights of the past festivals.

-Back in the year 2000, ASIFA East, celebrating their 30th Anniversary, produced a book outlining the history of their festival. All of the award winners over all of those 30 years were listed, and a lot of images featured some of the highlights of the past festivals.

I loved this little xeroxed booklet. It let me feel like I was an important part of this organization’s history. The booklet was designed and edited by Mark Segall, with help from Howard Beckerman and Bill Lorenzo.

Now that ASIFA East is about to celebrate their 40th Festival, I thought it not a bad idea to post all of the pages from that little publication.

Here they are:

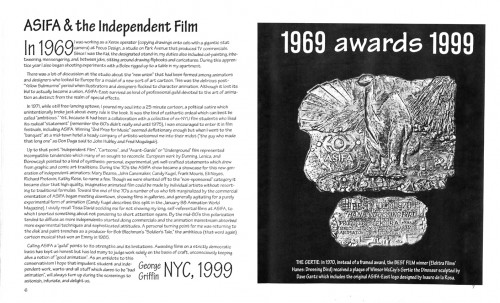

Comment by Howard Beckerman | Back Cover

(Click any image to enlarge to read,)

There are a lot of films that won here and went on to win everything else out there. Frank Film, Your Face, A Soldier’s Tale, The Chicken From Outer Space and many others started out at this little fest and became Oscar/EMMY contenders/winners.

You never know what’ll show up – be there Sunday at 6.

Articles on Animation &Daily post 22 Apr 2009 07:37 am

Norstein’s Words

- Animatsaya in English is a site I visit frequently even though it doesn’t change that frequently. It’s a site that gives a good insiders view of Russian animation. Currently, I think they’re doing some of the best animation worldwide. Not too long ago, Niffiwan, the site’s host, offered a translation of a Russian article about the effect of the financial crisis on Russian animation. Naturally, the results were devastatingly bad.

However, toward the end of the piece, several prominent animators were asked their opinion, and I thought that Yurij Norstein offered some valuable words. Hence, I repost them here:

It has always been difficult for an artist, but today is doubly difficult. Always difficult, because the artist, in general, is a person who finds it difficult to live with himself. Today is doubly hard, because the lack of money and the constant attention to the question of “how to get money” kills art by half.

It has always been difficult for an artist, but today is doubly difficult. Always difficult, because the artist, in general, is a person who finds it difficult to live with himself. Today is doubly hard, because the lack of money and the constant attention to the question of “how to get money” kills art by half.

But it is also obvious that it is very difficult without a community. If we lose each other, then we will all be worth one kopek, and it is unlikely that we are individually worth something and can do something. I, of course, am talking about my own experiences at “Soyuzmultfilm”. And although we did not have ideal relations, though we argued with each other, we were still a community, and our only desire, emotional and mental, was to make a film be as good as possible.

The last thing we thought about was the market, what would sell … If you remember, say, the Renaissance, an artist back then sought primarily to make something. This is why the artist must be at the head of everything.

I suggest you visit the site and read the entire article. Things in your community may not be as bleak as you thought.

- Jeff Scher has one of his lively animation pieces in the NYTimes, in case you haven’t seen it recently. This is an ode to Spring. “Welcome Back.” It’s another excellent spot by Jeff, and I urge you to view it. We have to support the animation on newspaper sites. It’s the way of the future, and the newspapers should know it. The only way that can happen is for the pieces to get hits. Go there.

- Thad Komorowski has some positive words about a Fox & Crow cartoon, (they’re not easy to find) and Bob Jaques has an excellent post about Paramount animator, Tom Golden.

Articles on Animation 26 Mar 2009 08:03 am

Terry Arcana

- I found a couple of articles about Terrytoons and thought I might share them. (Even Terrytoons had their share of PR.) The first talks about the films they’re about to release in 1941.

Click any image you’d like to enlarge to read.)

Many years later Terrytoons, having been sold to CBS, were about to premiere a prime time show (7:30 wednesday nights) that featured Dick Van Dyke (pre Dick Van Dyke show) talking to cartoon characters on a television set.

Even back then I thought it was a cheesy show but still tuned in for the few weeks it was on air. Eventually, after the show was pulled Terrytoon cartoons showed up on saturday morning with The Mighty Mouse Show. This was a big deal; it was the best show on Saturday mornings way back then – years before Bullwinkle, Huckleberry Hound and terrible terrible programming.

Here’s a piece promoting the Dick Van Dyke hosted show:

The cartoons leased to local WOR-TV included a lot of silent shorts with classical music backing and some early-30′s cartoons.

The cartoons leased to local WOR-TV included a lot of silent shorts with classical music backing and some early-30′s cartoons.

They started a show called Barker Bill’s Cartoon Show. A ringmaster named Barker Bill introduced cartoons. He was a cartoon character that appeared in a couple of early 30′s cartoons. For this show a live actor impersonated him and introduced old time B&W cartoons.

The show was later retitled Super Circus with Claude Kirschner, then Big Time Circus with Claude Kirschner. He was a local NY announcer who acted as the ringmaster (who was not Barker Bill.) He was apapropriately dressed as a ringmaster and chatted with a clown hand puppet named, “Clowny.” (You can see the originality of the creation.)

The show was later retitled Super Circus with Claude Kirschner, then Big Time Circus with Claude Kirschner. He was a local NY announcer who acted as the ringmaster (who was not Barker Bill.) He was apapropriately dressed as a ringmaster and chatted with a clown hand puppet named, “Clowny.” (You can see the originality of the creation.)

When the Terrytoon deal ran out, they then showed foreign, dubbed cartoons.

Articles on Animation &Disney 14 Mar 2009 08:12 am

After Walt

- Didier Ghez on his site Disney History recently posted an article about life at the Disney Studio after Walt’s death in 1966. There were quite a few such articles during this period, and we were made to hope something would happen to generate life into the animation division of a company that was turning out bad films.

Time Magazine had the following article in their Aug. 16, 1979 issue:

CORPORATIONS

Running Disney Walt’s Way

When lung cancer killed Walt Elias Disney a decade ago, there were fears that the world of Disney would lose some of its wonder—and its profits. But before his own death in 1971, Roy Disney, who succeeded his younger brother, and a cadre of post-Walt executives had turned Walt Disney Productions into a thriving empire of fantasy. Today the company is bigger and richer than ever. Profits flow in from Disney’s two successful theme parks, Disneyland in California and the magic kingdom at Walt Disney World in Florida, from film rentals and television, from re-releases of such longtime favorites as Bambi, Pi-nocchio and Fantasia, and from sales of record albums, Mickey Mouse wrist-watches and everything else bearing the Disney stamp.

Last year the various forms of escapism earned Disney nearly $62 million on sales of $520 million—four times the total in 1966 when Walt died. For the first nine months of its current fiscal year, Disney was flying higher than Dumbo the elephant. Corporate profits were up 30%, and sales rose 16%. More than 6 million people flocked to Disneyland (which turned 21 in July), another 9 million to Disney World. The fifth re-release of the animated Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, which came out in 1937, will gross an estimated $10 million in the U.S. alone by the end of this year.

Last year the various forms of escapism earned Disney nearly $62 million on sales of $520 million—four times the total in 1966 when Walt died. For the first nine months of its current fiscal year, Disney was flying higher than Dumbo the elephant. Corporate profits were up 30%, and sales rose 16%. More than 6 million people flocked to Disneyland (which turned 21 in July), another 9 million to Disney World. The fifth re-release of the animated Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, which came out in 1937, will gross an estimated $10 million in the U.S. alone by the end of this year.

Analysts’ View. No one questions that Disney has come a long way since the studio gambled $1.5 million on Snow White. But Wall Street analysts insist that the company should be doing even better and are hypersensitive to any developments that could remotely be considered adverse. Last month, for example, Disney stock fell several points (to around $50, or more than 20 times earnings) because third-quarter earnings, though a record $19 million, were not up to Wall Street’s expectations. Says a Disney vice president: “That’s a source of irritation around here. They seem to run in a pack on the Street.”

The founder’s ideas still run the show: almost everything Disney is now into was conceived of by Walt. “That’s the way Walt would want it” is a refrain heard frequently in the stucco Disney headquarters in Burbank, Calif. The executive most responsible for sticking to Walt’s winning formulas is E. Car-don Walker, 60, who joined Walt as a camera operator in the 1930s and has been Disney president since 1971. A tall, husky man whose use of profanity is limited to an occasional G-rated “damn,” Card Walker occupies an unpretentious office on the Disney lot not far from Dopey Drive and Mickey Avenue. His only concessions to the Hollywood movie mogul image are tinted glasses and a sleek gray Porsche (license plate: CAR WIN).

The founder’s ideas still run the show: almost everything Disney is now into was conceived of by Walt. “That’s the way Walt would want it” is a refrain heard frequently in the stucco Disney headquarters in Burbank, Calif. The executive most responsible for sticking to Walt’s winning formulas is E. Car-don Walker, 60, who joined Walt as a camera operator in the 1930s and has been Disney president since 1971. A tall, husky man whose use of profanity is limited to an occasional G-rated “damn,” Card Walker occupies an unpretentious office on the Disney lot not far from Dopey Drive and Mickey Avenue. His only concessions to the Hollywood movie mogul image are tinted glasses and a sleek gray Porsche (license plate: CAR WIN).

Walker believes that “the biggest challenge we face is still to make top-quality films,” and film critics tend to agree. Though slick and successful, the recent crop of Disney animated and live-action films (Gus, Treasure of Mate-cumbe, Robin Hood) shows little of Walt’s skill at tugging an audience over pop-emotional peaks and valleys. Nor do the forthcoming The Rescuers and Pete’s Dragon. Indeed, not since Mary Poppins in 1964 has Disney produced a genuinely smashing, supercalifragilisti-cexpialidocious hit.

This fact troubles Walt’s corporate heirs. Says Walker: “I don’t know exactly what it is. We don’t cut costs. Based on the quality of people involved in the film making, I would just have to say that we do our best.” Others blame excessive reverence for the traditional Disney method of moviemaking: batteries of cartoonists working under a rigid discipline on a single project for as long as three years. Says one young artist-animator who worked briefly for Disney: “The work is too confining. There’s not enough room to use your creative talents. It’s sterile.”

More and more, Disney is setting its animators to work on gutsier movies that seize audiences instead of rocking them to sleep. One feature in the storyboard stage, The Hero from Otherwhere, is about two schoolboys who find themselves on a strange planet whose black leader persuades them to help destroy a wolf that has been ravaging the land. Another, Spacecraft One, about a mile-long spaceship in its search for life on other planets, is Disney’s most elaborate sci-fi undertaking since 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. The Black Cauldron, still in the treatment-writing stages, is about a pig keeper’s struggle with a villain whose shtick is regenerating an army of warriors from dead bodies—a long way from Poppins. Sex and excessive violence still are taboo on the Disney lot, but Walker foresees increased sophistication as younger animators reflect contemporary themes.

Non-film projects, however, account for three-fourths of Disney revenues and therefore generate the greatest excitement in the Disney organization. With Disneyland and Walt Disney World booming, the company is now moving on the biggest of Walt’s ideas: EPCOT, or Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow. To be built by the early 1980s in Florida as an expansion of Disney World, EPCOT will be a living laboratory of applied technology in transportation, housing, communications and waste disposal. Near it will rise the World Showcase, a permanent World’s Fair. Still another theme park. Oriental Disneyland, now planned to open late in 1979, will border Tokyo Bay in Japan; the Disney people expect it to draw 10 million visitors annually at the tourist hub of Asia. Estimated cost: about $175 million—most to be borne by the Japanese.

Non-film projects, however, account for three-fourths of Disney revenues and therefore generate the greatest excitement in the Disney organization. With Disneyland and Walt Disney World booming, the company is now moving on the biggest of Walt’s ideas: EPCOT, or Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow. To be built by the early 1980s in Florida as an expansion of Disney World, EPCOT will be a living laboratory of applied technology in transportation, housing, communications and waste disposal. Near it will rise the World Showcase, a permanent World’s Fair. Still another theme park. Oriental Disneyland, now planned to open late in 1979, will border Tokyo Bay in Japan; the Disney people expect it to draw 10 million visitors annually at the tourist hub of Asia. Estimated cost: about $175 million—most to be borne by the Japanese.

Double Duty. Whatever its problems, Disney has perfected one talent that other Hollywood fantasy factories envy: piggybacking. The familiar cartoon characters boost attendance at the theme parks, and the parks increase attendance at the movies. Though no one at Disney claims to be Walt’s equal in artistry or dreaming, Card Walker has made Disney’s characters do double duty as stars and as barkers to all the world. As a merchandising idea, it has proved to be almost as successful an inspiration as the original Mickey Mouse.

Articles on Animation &Books 04 Mar 2009 08:36 am

Tekenfilm

- Marten Toonder lived through much of the history of Dutch animation. (Like many other throughout Europe he gained the moniker of the “Walt Disney of Holland.”)

- Marten Toonder lived through much of the history of Dutch animation. (Like many other throughout Europe he gained the moniker of the “Walt Disney of Holland.”)

He was born in 1912 and died July, 2005. In 1940, with puppet animator, Joop Geesink, he formed the Geesink-Toonder Studio. The break-up of the two led to his forming the Toonder Studio in 1942.

He left this studio, as tituilar head, to get back to illustration in 1965, and ultimately retired in 1977.

Toonder is probably best remembered for his several successful comic strips. You can visit a sample of these here or here.

He made animated shorts of his comic strip, Tom Puss, which you can see on YouTube.

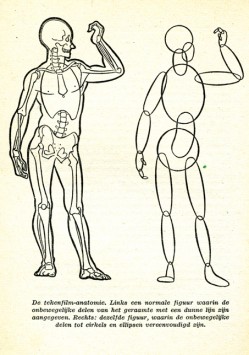

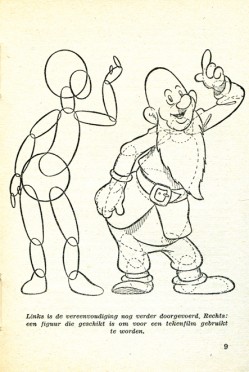

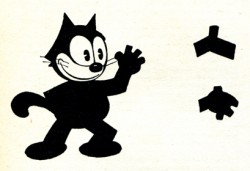

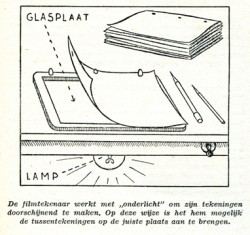

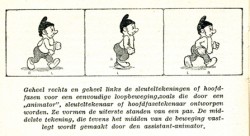

I make Toonder the subject of this post because I have an early book about animation which he wrote. Called Tekenfilm, it seems to have been written in 1946; at least that’s the only date I can find in the smallish publication.

It’s in Dutch, so I’m not able to read the book. However, I thought I’d post a couple of pages of the book . I haven’t been able to find any reference to the publication to date. ___________________The book’s flyleaf – in Dutch

The book’s Front cover & Back cover

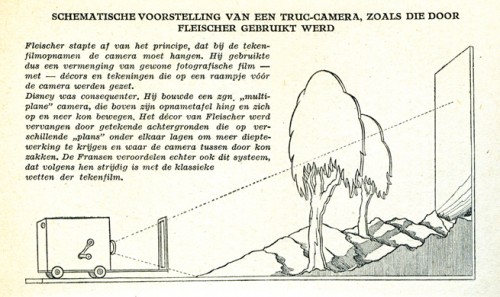

Here the Fleischer studio gets credit for the Multiplane Camera.

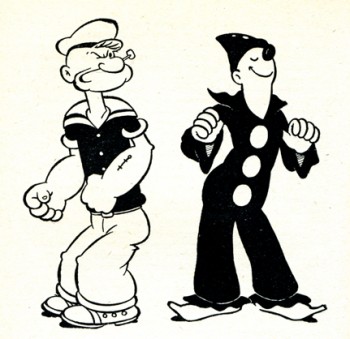

I like the way Popeye is drawn. Koko looks more on model.

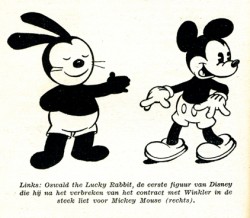

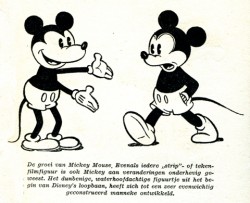

A wierd looking Oswald leads to Mickeys.

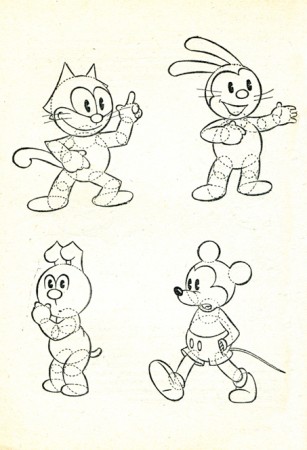

How to try to draw some characters.

Where’s Bugs?

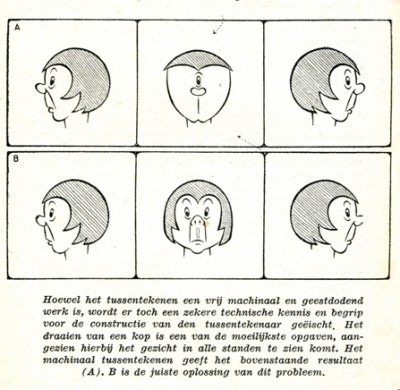

Here’s a lesson you still don’t see in many animation books.

How not to draw the mechanical inbetween.

His solution isn’t the best.

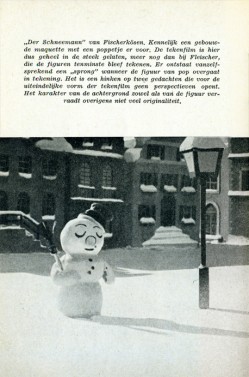

Ending with two European cartoons of merit from 1944:

The Snowman in July by Hans Fischer-Kösen

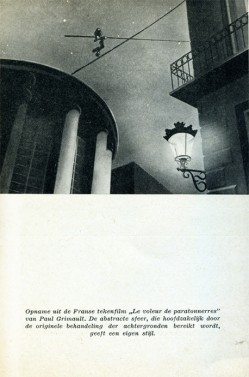

and Voleur de Paratonnerres by Paul Grimault

Articles on Animation 13 Feb 2009 08:50 am

Heidi’s Song

- Animated features, like some of the shorts, come and go. While working on it, there’s often an expectation that THIS will be the film to catch gold and change history. It doesn’t happen often.

Looking back on a puff piece from some past feature is oftentimes ludicrous; sometimes it’s just sad. Here’s a 1981 story from Millimeter Magazine about Hanna Barbera’s upcoming feature, Heidi’s Song. It sounds like it may be the future, but really it’s even hard to remember the film. It certainly didn’t change the world.

Will HEIDI’S SONG be its SNOW WHITE?

by John Canemaker

Hanna-Barbera Productions Inc. is such a giant corporate entertainment entity that it prompts the old joke: What does a two-ton canary sing? Any damn thing it wants! This Hollywood “canary” tias expanded since 1957 to become the wold’s largest producer of animated TV series andspecials; more recently Hanna-Barbera has become involved in themed amusement parks and live action movies for television.

Now H-B is eager to enter and conquer the sacred Disney domain of fully animated, “quality” feature-length animated films for theatrical release. William Hanna and Joseph R. Barbera hope to do so with an expensive flourish this summer when they will premiere HEIDI’S SONG, a $9 million cartoon feature that has been in production for five years. The film’s staff of 200-plus includes 12 background painters, 60 assistant animators, eight layout people, and 18 top character animators. All cut their teeth years ago at the Disney studio, or at MGM, working with Hanna and Barbera during their halcyon days in the 1940s and ’50s producing Tom and jerry shorts and animated segments for live action features such as Jerry the Mouse dancing with Gene Kelly in ANCHORS AWEIGH.

A moment of menace for Heidi whose voice is dubbed in by

Broadway actress Margery Gray in the Hanna-Barbera feature.

Joseph Barbera claims HEIDI’S SONG will be “a step forward in animation that’s very exciting.” But perhaps it will actually be a welcome artistic step back—a comeback of sorts—for Hanna and Barbera, who were once considered by their peers and the public to be superior cartoon craftsmen, winners of seven Academy Awards for two decades of beautifully timed and fully animated Tom and Jerry cartoons. In the 23 years since forming their own company—a factory geared to the production of “limited” animation series, a reduced form of animation that, as an H-B publicity release points out, “ignored the time-consuming and expensive detail that would not be visible on the dimly lit video screen”—Hanna and Barbera have produced over 20 TV specials and some 60 series (“Huckleberry Hound,” “Yogi Bear,” “The Flintstones,” “The Jetsons,” “Scooby & Scrappy Doo,” and so on).

In other terms, H-B produces more film footage in a week today than it did in a year at MGM. The principals’ choice to, as they say, “exploit a niche Disney had missed in family entertainment, with low cost cartoons for television,” has made the two men cartoon tycoons, rich beyond their dreams. They claim “there is not one hour out of every 24 that a Hanna-Barbera cartoon is not entertaining some segment of the world’s population.”

When, in 1967, Taft Broadcasting Company of Cincinnati acquired H-B, the company expanded its operations into five themed amusement parks, including Kings Island (Cincinnati) and Marineland (Los Angeles), where life-sized replicas of H-B characters—Yogi, Huckleberry et al — roam about greeting visitors. More than 1500 licensed manufacturers world-wide turn out 4500 different products bearing likenesses to H-B characters, for example, Flintstone window shades, Scooby-Doo pajamas.

In 1978, H-B won an Emmy, this time for a live action TV movie, “The Gathering,” starring Ed Asner and Maureen Stapleton; more live action films are planned for theatrical release and TV. With all this success, why would Hanna-Barbera bother pouring money into turf that is traditionally Disney’s and has proved to be a producer’s graveyard, from GULLIVER’S TRAVELS (1939) to RAGGEDY ANN & ANDY (1977)?

Company is built on cartoons

One should not forget that cartoons are the heart of the H-B corporate structure (as they are at the Disney studio). And it must be noted that as popular as the TV series are with small children, there is, to Hanna and Barbera’s distress, a persistently vocal, mostly adult contingent that just plain doesn’t like their cartoons! Veteran animator/director Chuck Jones, for instance, dismisses the whole breed of limited animation TV fare as “illustrated radio!” Writer Leonard Maltin once denounced H-B cartoons as “consciously bad: assembly-line shorts grudgingly executed by cartoon veterans who hate what they’re doing.”

Years of this kind of criticism (and worse from TV critics, parents groups and, most painfully, professional peers) has hit Hanna and Barbera right in their pride of craftsmanship. Witness Bill Hanna’s responses during an interview with Eugene Slafer: “Are you accomplishing what you believe is good TV animation?” asked Slafer. “No, I do not,” came

Years of this kind of criticism (and worse from TV critics, parents groups and, most painfully, professional peers) has hit Hanna and Barbera right in their pride of craftsmanship. Witness Bill Hanna’s responses during an interview with Eugene Slafer: “Are you accomplishing what you believe is good TV animation?” asked Slafer. “No, I do not,” came

__Director Robert Taylor states that HEIDI’S SONG has _______Hanna’s candid reply.

__“a style unto itself, more like a live action picture in_______ To a further probe, “Have

__the staging, as opposed to what you’d see in animation.”____you ever been ashamed of your work, especially since parents have ranted about the general lack of quality on Saturday morning cartoon shows?” Hanna admitted, “Actually I feel like I should crawl under a seat sometimes.”

Joe Barbera recently spoke with Millimeter about his partner’s abilities to recognize the difference between good and bad quality animation and their alleged lack of craftsmanship. “We had to get that stuff out for Saturday morning,” he explains. “That’s a budget problem. Believe me, I don’t stand still for people saying, ‘Oh, they’re doing junk! They don’t know how to do…. ‘We’re not doing that. We only do it because you don’t get the money to do it differently. When we get the money —and you’re talking about millions—we doajob!”

So perhaps the initial thrust for the HEIDI feature came from Hanna’s and Barbera’s desire to prove they haven’t forgotten how to produce animation in the “classical” style, or how to create memorable characters that affect more than an audience’s funny-bone. Of course, Hanna and Barbera are too business-wise to produce a full-animation feature merely to assuage pain dealt their pride; there also had to be a bedrock of financial motivation behind the move and, sure enough, there was. “The thrust,” states Barbera, “was to do one every year and to build a superb perennial library, which Disney had for years.”

The Disney animated features, from SNOW WHITE (1937) to THE RESCUERS (1977), are re-released like clock-work every seven years, just in time to greet a new generation or to remind an older group of their existence. “They are,” says Barbera admiringly, “forever pictures;” that is, films that keep the Disney empire well-oiled with money derived from box office returns (pure profit, since there are no production costs on re-releases), and from lucrative merchandising spin-offs, like comic strips and dolls for themed amusement park rides. This money-making machine depends upon the public’s continuing affection for the cartoon characters and their “classic” stories found in the Disney features. Hanna and Barbera have not yet fully entered this profit arena, but they have been working on it.

Previous animated features

HEIDI’S SONG is not H-B’s first attempt to produce an animated feature. There was, for example, HEY THERE, IT’S YOGI BEAR in 1964 and A MAN CALLED FL1NTSTONE in 1966, both low-cost, limited animation, based on the one-dimensional characters from TV. Neither film was a “forever” picture.

There was,”in 1973, an H-B version of E.B. White’s book Charlotte’s Web, but this, too, suffered from the taint of limited animation and questionable production values. Reviewer Vincent Canby of The New York Times said of the film, “Parents will survive it, and so will the children.” Barbera acknowledges there was “a problem” with CHARLOTTE’S WEB, but to him it was a misjudgment of the financial potential of the material. “Charlotte’s Web,” says Barbera, “is an American classic. It is not an all-world classic. Germany ended up calling it Zuckerman’s Pig, after the name of the man who owned the pig in the story, because who ever heard of a Charlotte’s Web? The film version is recouping some of its money on Home Box-Office TV, on video cassettes and in non-theatrical markets, a fate H-B hopes to avoid for HEIDI’S SONG.

While Disney can produce almost any project known or unknown because of the sales value inherent in the name, “Disney,” Hanna-Barbera is not yet in that sublime position. To the general public, “Disney” means full-animation, perfect technological craftsmanship, beloved characters in stories containing mythic or nostalgic associations. To the same public, “Hanna-Barbera” means limited animation of flat characters on redundant television series. H-B seeks to improve its image with HEIDI’S SONG.

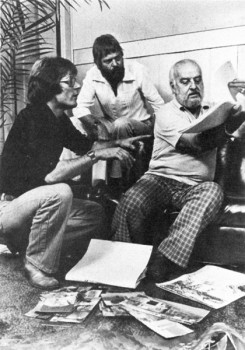

Animator Charlie Downs (left) flips drawings for director Bob Taylor.

HEIDI’S SONG is the story of an orphan girl, based on Johanna Spyri’s 100-year-old, internationally known book. The cartoon feature contains a”Broadway” score of 16 songs by veterans Sammy Cahn (lyrics) and Burton Lane (music). The characters’ voices include Lome Greene as Heidi’s reclusive grandfather, Broadway actress Margery Gray as Heidi, and Sammy Davis, Jr. as King Rat, leader of a band of rodents. Other characters include a “mean and scary ancient housekeeper,” Fraulein Rottenmeier; Sebastian, “the butler who helps Rottenmeier be miserable to Heidi”; Clara, a lonely girl “confined to a wheelchair”; Peter, “a young goatherd, agile as the animals he tends.”

Off-setting the human characters is a gaggle of animals; Spritz, Heidi’s “feisty” pet goat; Hooter, a baby owl who “warns Grandfather of Heidi’s imprisonment in the cellar”; Gruffle, Grandfather’s “gruff old hound”; Schnoodle, a “nasty little dachshund who is rotten like his mistress, Fraulein Rottenmeier.” There is also a “crusty” German Schnauzer, a white mare, a white kitten and the aforementioned royal rat, “the power-loving and peppy leader of the rats in Sebastian’s basement, who spurs his clownish rodents into a strong force to attack Heidi.”

“We do have our animals,” points out Barbera. “My gosh, if we don’t have animals, we’re in big trouble,” he notes with an eye toward audience appeal and merchandising. “But we do have humans and some marvelous dancing,” he continues. “We are not rotoscoping,” he says, referring to the technique of animators tracing frame-by-frame projections of live-action. “I don’t care for rotoscoping at all.”

Choosing talent

Hanna and Barbera have instead hired a team of 20 top character animators—”Let’s use the word humbly and respectfully: the old-timers, “adds Barbera—people like Hal Ambro and Charlie Downs, both of whom specialize in human figure animation and have worked on films such as Disney’s PETER PAN and Richard Williams’ RAGGEDY ANN & ANDY. There are also master animators of animal caricatures and comic timing, such as Irv Spence and Ed Barge, veterans of the fine Tom and ]erry shorts. Th’e great Disney/MGM animator, Preston Blair, was also involved with HEIDI for a time.

One might assume that the difficult task of manipulating the drawn human form in full animation is what kept the film in production for five long years. Barbera, however, offers this explanation: “When we are in the slow season, which happens in television all the time, everybody has to be laid off. We were going to keep people busy on the feature. We found that doesn’t work. The kind of people you use on a feature are the old super-pros of our industry, and there are few of them left.

One might assume that the difficult task of manipulating the drawn human form in full animation is what kept the film in production for five long years. Barbera, however, offers this explanation: “When we are in the slow season, which happens in television all the time, everybody has to be laid off. We were going to keep people busy on the feature. We found that doesn’t work. The kind of people you use on a feature are the old super-pros of our industry, and there are few of them left.

“Secondly, we wanted to use HEIDI’S SONG as a training ground for new animators. The first three or four years the picture would go into production and stop, then go back into production and then stop. That was not good for the picture. We were losing momentum, the enthusiasm of the artists and the excitement we wanted to build up. So finally, about a year and a half ago, we marshalled the last remnants of

__Bob Taylor, director, and animators____ what we think are the best people in the

__Charlie Downs and Hal Ambro. ________business. When we brought these people in we had to change directors. We had a fine guy, but he had forgotten how to go back and really work these old-timers — really get the good animation! We then hired a brilliant young director, Bob Taylor, who is dynamite!”

Prior to rejoining H-B a couple of years ago (he had first worked there in 1966 for one year), Robert Taylor worked for Ralph Bakshi, Steve Krantz, DePatie-Freleng and Murakami-Wolf. “I always seem to come in on things that are hopeless,” he commented recently, “and we try to turn them into hopeful. I think we’ve done it with this picture. For me and the whole crew, and for Joe and Hanna-Barbera and Taft, this is our entrance into real good quality stuff!”

It has not been a piece of cake for Taylor. When he took on the HEIDI assignment, the script was written and the tracks were already recorded. “It was a hang-up for me,” he admits. “That’s the albatross around my neck. The story is episodic. If I had written it, I would have made it a little stronger in terms of her emotions and some of the dialogue. But,” he adds brightly,

I “my whole trip is to keep the audience entertained—get people to go to animated films and make them feel when they come out that they’ve seen something they can’t see anyplace else. It isn’t so much the tools;

i it’s what the hell I’m trying to do with it.”

Trying to elicit a description of the film’s style from both producer and director is difficult. According to Barbera, “The results have been what I call a Hanna-Barbera feature. It is not going to look like a Disney picture, or a FRITZ THE CAT or a RAGGEDY ANN & ANDY. We have our own style.” When pressed, Barbera cites “some very imaginative pieces of business.” Pressed further: “We’re not holding back. When they lock Heidi in the cellar, that’s a scary place—to be locked in a basement in a house in Frankfurt in the 1880s, that’s enough to put you away. We’re not holding back, yet we’re keeping it in good taste throughout.”

New wave animation

Taylor was a bit more specific: “I hate to opportunity for the guys to get back into what it’s really all about. We take as many new animators as we can bear—the ones that have the enthusiasm and are really interested in what we’re calling a ‘renaissance.’ But even more important, we are just interested in making great animated films and updating them into the 1980s.”

The HEIDI unit has already begun production of its next two animated features, ROCK ODYSSEY (which Barbera describes as “a marvelous treatment of music from the 1950s, ’60s and 70s. A rock-FANTASIA, if you want to call it that”), and NESSIE COME HOME, a tale about the Loch Ness monster. Again, the thinking behind the choice of both projects is carefully calculated toward maximizing box office. “If you are going to do a feature,”reasons Barbera, “you must have something people will identify with. You can’t do ‘Willie the Glowworm!’ That’s why HEIDI is so great. It’s always a problem finding material. Watership Down is a marvelous book, but we would have hesitated to do it because it’s just not that well known. It’s a gamble. You have to put four to five million dollars into something like that.”

Marketing concepts for animated features

At a time when Disney films are attempting to woo an older (“PG”) audience, one wonders why Hanna-Barbera appears to be aiming toward a traditional, family-oriented “G”-rated audience with its animated features. Barbera explains: “First of all, anything that Disney has done is going to play forever, so he will have that constant market in every media. Secondly, the theater audience isn’t going to be the only audience. There are going to be cassettes, a perennial that will run forever. And thirdly, we are going to have our own style. We’re not going to have a picture that will be only for kids. We will get the adults with this one.”

“ROCK ODYSSEY,” continues Barbera, “will appeal to those between the ages of 18 and 35, but we will not lose the kids because of the animation. And we will have the adults that remember those ’50s and ’60s songs. NESSIE will have a great, I hate to use the word, ‘environmental’ appeal, but we will be protecting a character that’s getting it. If there are monsters in that lake, they get bothered—by submarines, depth bombs, cameras—more than any character in the world. We have a very unusual twist that will make it appealing.”

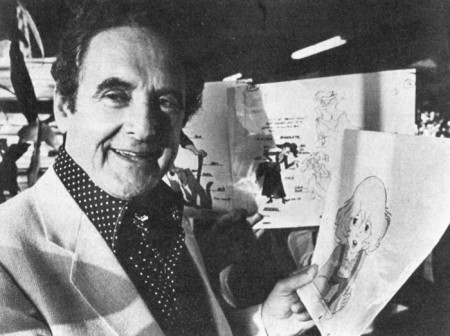

Joseph Barbara, executive producer, displays color models that some

150 animators used for reference while working on HEIDI’S SONG.

Asked whether the future might see Hanna-Barbera producing adult-oriented features a la Bakshi, Barbera answers, “Oh yes, very much! We had a recent all-day meeting where the thrust was the fact that we can’t depend on the children audiences to pay for these things. We must attract the adults, too. Statistics show there are less children around now. So whatever we do, we must attract the adults.” Barbera must have been thinking of a recent Bakshi product, i.e., LORD OF THE RINGS, for when asked if he would produce an unquestionably adult cartoon such as HEAVY TRAFFIC or FRITZ THE CAT, he replied, “No! I don’t think we would do that! We certainly wouldn’t shy away from a gutsy project, but it must bring in the kids, too. So there would be no bad taste.” For the time being, it is significant that Hanna-Barbera is training an enthusiastic crew in the techniques of full, character animation, one form of the art that for the last two decades has seemed to teeter constantly on the brink of extinction. It is enough for now that H-B is producing with integrity and care a film like HEIDI’S SONG, which will attract and appeal to large audiences.

The success of Hanna-Barbera will keep an avenue open for future animated features, and hold the public’s awareness of and interest in the medium of animation itself. With an increase in the number of future animated features will come diversity in form and content. Animation

as a vital and viable entertainment medium will then come closer to realizing its potential, as it did in 1968 when George Dunning directed YELLOW SUBMARINE, and in the early 1970s, when Ralph Bakshi excited audiences, and, indeed, as in 1937 when a struggling young producer named Walt Disney redefined the genre.

Articles on Animation &Chuck Jones &Frame Grabs 11 Feb 2009 09:00 am

Wackiki Art

- John McGrew is a principal designer in the history of animation who quite radically changed things for us all. He led the way out of the 19th Century and, with Chuck Jones’ blessing, pulled the art of animation into the 20th. Others followed or were running alongside him, but he left the first mark.

Mike Barrier interviewed McGrew in his studio in France in 1995, (photo right by Phyllis Barrier from Mike’s site) published the interview in Funnyworld Magazine and has it now posted permanently on his website. If you have any interest in design in animation, you should have already read it. I just reread it for about the 15th time, and am amazed at how much history is packed in there. Go here.

Mike Barrier interviewed McGrew in his studio in France in 1995, (photo right by Phyllis Barrier from Mike’s site) published the interview in Funnyworld Magazine and has it now posted permanently on his website. If you have any interest in design in animation, you should have already read it. I just reread it for about the 15th time, and am amazed at how much history is packed in there. Go here.

McGrew, with his work on The Dover Boys and dozens of other brilliant cartoons, took animation into abstraction and back. His work, I think, is comparable to Scott Bradley’s music at the MGM cartoons. Bradley was the very first film music (live action or animated) to incorporate Schoenberg’s 12 tone serial music. McGrew didn’t imitate Picasso or Steinberg, he created modern art in animation.

McGrew did his layouts in color showing the background artists what he wanted. He worked with strong designers, in their own right, painting backgrounds:Paul Julian, at first, and  Gene Fleury after 1941. When he left the unit, during the War, Bernyce Fleury took his place working with her husband, Gene, on Jones’ films.

Gene Fleury after 1941. When he left the unit, during the War, Bernyce Fleury took his place working with her husband, Gene, on Jones’ films.

Wackiki Wabbit is one of the most interesting of Chuck Jones cartoons.

Precisely because of the layouts and backgrounds. They’re done in an abstraction that almost dominates the film, but actually serves to represent a world of foliage. The style uses cutouts and a wide range of techniques. Mcgrew probably did not work on this film; it came exactly at time of  change when Bernyce Fleury entered the picture. McGrew, in the Barrier interview, says that he had never worked with her on a film. Her style seems evident throughout. Cut-outs mixed with the wallpaper-like patterns.

change when Bernyce Fleury entered the picture. McGrew, in the Barrier interview, says that he had never worked with her on a film. Her style seems evident throughout. Cut-outs mixed with the wallpaper-like patterns.

The film gives no credit to Layouts or Backgrounds.

I’ve made some frame grabs of the backgrounds (eliminating most of the characters – unless they were stationary) and

___ (Click any image to enlarge.)__________am posting them below.

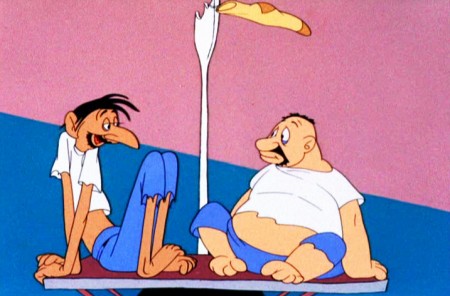

The film opens with tones of blue against a pink sky.

The two solidly drawn cartoon characters float in a sea of color.

This is about as green as the Island will ever get.

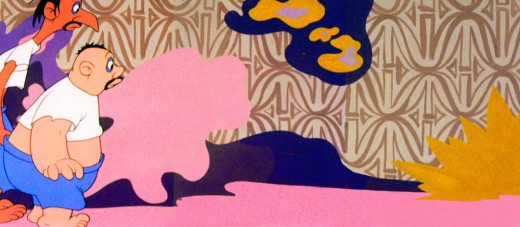

On the island, Bugs Bunny lives in a world of abstract foliage.

The colors are skewed – not verdant but warm.

Large masses of solid colors sit against brush drawn lines.

A limited number of colors allows the scenes to cut

without following through with any other consistency.

However, if you remove the characters, you’re missing the center.

As it should be.

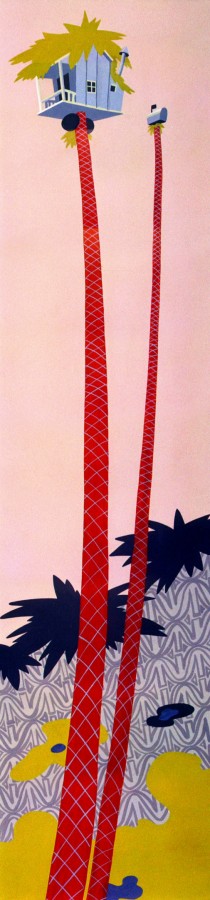

There are numerous large and fast pans,

this one a diagonal from right to left.

Some areas like the blue, above left, or the red, above right, animate.

The solid colors help them all to combine seamlessly.

Bugs dances on the right, a pan

to the left reveals the two humans.

Cut from the pot to a quick pan high up in the trees.

This serves as a sunset with our two humans

chasing each other into the distance and the film’s end.

Articles on Animation 07 Feb 2009 09:34 am

Dilemma

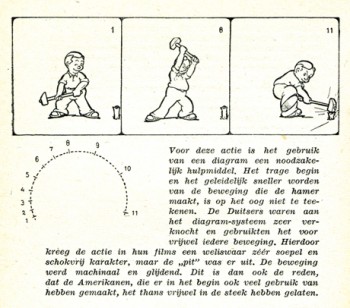

John Halas was always an advocate for computer animation. He wrote about it long before there was any visible signs of success and he produced some early films using available technology. In 1981, in conjunction with Computer Creations, he produced a 10 min. film done completely digitally.

Computer animation, in those days, was rather priimitive. 6 years earlier, Peter Foldes with his film, Hunger, had offered wire-frame imagery that was didn’t really suggest to character animators the revolution to come. Perhaps Dilemma did, though it didn’t get the attention it might have.

A scene from the film attempts some animation as the winged man

slowly moves his wings up and down as he recedes into Leonardo’s head.

Rather than try to create 3D dolls, the filmmakers were attempting to do graphic animation. There’s nothing in the way of character animation in the piece, though there is a lot of machinery and gears moving and turning. They attempt to tell a story using a lot of morphing graphics and electronic music and sounds.

Within a couple of years, Abel Associates and PDI were producing a lot of shiny things and silver robots animating – change that to moving on the commercials for Levis and cars.

Within a couple of years, Abel Associates and PDI were producing a lot of shiny things and silver robots animating – change that to moving on the commercials for Levis and cars.

Only 11 years after Dilemma, Pixar would offer Toy Story. Little Viewmaster-like dolls took over computer animation and sealed the near future.

Here’s an article that appeared in a 1981 issue of Millimeter that talks about Dilemma.

by Jim Lindner

Attempting a 10-minute film produced entirely with the assistance of digital computers in the style of traditional animation could send chills up the spine of even the most stalwart animator. Complicate matters by having the film contain over 160 scenes, special effects that include three dimensional simulation, utilize several thousand separate colors, produce the film from start to finish in less than two months, and you have a project that most would consider highly improbable. Such a film, however, is being produced as a joint effort of international scope between Halas & Batchelor Animation Ltd. of London, and Computer Creations of South Bend, Indiana, and New York.

“Dilemma” is a story of evolution; an evolution of intellect and achievement, and of the evolution of destructive capability. Indeed, man has often used his most powerful technological achievements as tools of destruction. The film portrays the progression of this evolution and the resulting dilemma between the application of technology for artistic or destructive intent. The implications of such devastation are clearly global, and it seems appropriate that the film be produced for and distributed by The United Nations General Assembly.

John Halas (veteran animator for over 40 years, producer of over 600 films, and the author of many books and articles on animation) is the visual designer behind the film for Halas & Batchelor in London. When asked why digital computer animation is being utilized for such a project, Mr. Halas responds that “There is no doubt that computer animation has potential to be exploited, and its impact will be felt in all aspects of visual

communication. In this case an approach that could deliver the art style inherent in Janos Kass’ [sculptor and designer whose work provided the inspiration for the film] design was required.”

Computers and animation are nothing new for Halas. In 1974, he wrote that “Artists and designers must come to terms with the computer as they must other gadgets operated by electricity, and if they seriously want to utilize the values and facilities, they obviously must learn to use the computer in much the same way they are using pencils, pens, and brushes.”

Working with John Halas was the Computer Creations team of president Tom Klimek, and senior art director Eric Brown. The challenge was clearly to accomplish such an ambitious undertaking within budget and within a very tight time deadline. Mr. Halas said that the normal productdion requirements for a job of this nature would take “ten full-time workers a minimum of eight months.” Mr. Halas adds that “Because of the reduced time and labor requirements, substantial cost savings have been achieved.”

The process utilized to produce “Dilemma” is known as VideoCel® and is purely digital in nature. There are no cameras, although the images have depth and perspective in full color and are not limited to moving colored lines. The actual artwork is entered into the computer by the artist, using an electronic tablet. The artist provides the coloring and timing instructions by answering simple-questions posed by the computer in ordinary English. In this fashion, the.artist is totally in control, with the engineers and programmers waiting in the wings should their assistance be required. The computer keeps track of all the colors, shapes, areas, and movements, exactly as transmitted by the skilled hand (and style) of the artist. The artist can view the work and modify the instructions for any part of the work at any time. When each scene has been completed, the computer draws each frame (over 18,000 for “Dilemma”), calculating the values for the over 250,000 colored points required for each individual frame.

Here’s an example of the often-used morphing technique that the

filmmakers use to move their story forward.

The images presented in “Dilemma” represent a cross between character animation /and three-dimensional graphic simulation. Several scenes are a computer-generated blend from one scene to another. Images swing and change position in dimension and recombine to produce entirely different pictures and scenes. In other sections of the film, objects delicately form and move about the screen in an abstract form eventually shifting to elements within the story. Still other scenes show fantasy space demons of the future being propelled through space in dimension.

One of the most interesting aspects of “Dilemma” is its pacing. While some sections are gracefully paced and balanced, other scenes race by with the urgency of the theme being conveyed by movement and design. Throughout the film, color is used in a fashion similar to that of conventional eel animation, with subtlety being the emphasis as opposed to high color or the typical glowing lines that have become so popular. With “Dilemma,” the computer has been successfully utilized as a design instrument with the design being determined by the artist — not by machine.

You can watch a clip of this film here.

.

Articles on Animation 25 Jan 2009 09:22 am

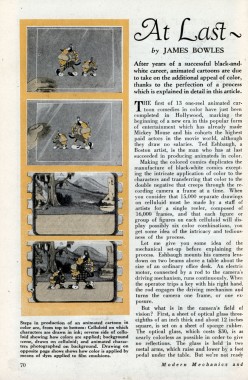

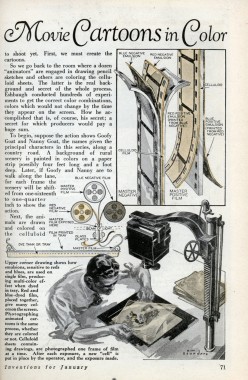

At Last – Color Cartoons

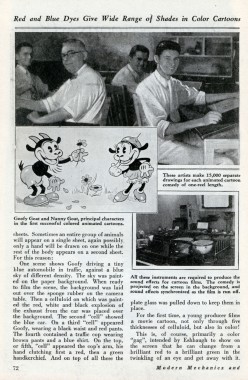

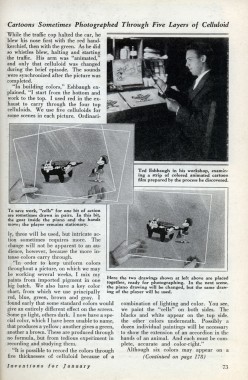

Here’s an article from Modern Mechanix January 1932. Ted Eshbaugh seems to have invented the first color cartoon, or at least he thinks he did. (Wasn’t Lantz’ titles for The King of Jazz in two strip technicolor color in 1930?) Eshbaugh, out of Boston, began his series, featuring Goofy and Nanny Goat, in 1932. This was the same year that Disney reworked his in-production B&W cartoon, Flowers and Trees to three strip technicolor. He had secured the exclusive rights to this newly patented innovation. Perhaps this article pushed Disney into rushing this film into color production.

At any rate, Eshbaugh’s film – and Eshbaugh himself – have been relegated to history’s darker bin. The article’s fun, anyway.

1

1  2

2(Click any image to enlarge to a legible size.)