Search ResultsFor "Grim Natwick"

Commentary 18 Mar 2013 04:05 am

Smears, Distortions, Abstractions & Emotions – 1

It took a full twenty years for the industrialized animated cartoon to develop into anything approaching a professional, never mind artistic, level. Thanks specifically to Walt Disney‘s efforts, in the twenties and thirties, animation developed as a process with guidelines, rules and specifics designed to create the most consistency. To have those characters moving in anything resembling the elements of real life, it took a real education. And the development continued past the zenith of Snow White so that things grew faster and faster in leaps and bounds. Studios outside of Disney’s were slower on the uptake fighting the inevitable costs that this better animation required. Just as a Paul Terry held off on turning to sound or color, until he had no choice if he wanted to compete in the marketplace, so, too, did he not approve pencil tests to better the animation in his films. The second largest studio at the time, the Fleischer studio, likewise was slow to agree to the new developments. Whereas the Color Classics exploited color film, the successful series, Popeye and Betty Boop stayed B&W. Likewise Fleischer’s animators didn’t get to see pencil tests except on more important product.

However, once we hit the early forties, animators started doing their own variations on differing ways of introducing “quality” to the animation. The artists wanted to explore the “Art” and ways to get there.

A sample of John McGrew’s work on The Arist-o-cat

Maybe they didn’t think they were doing “Art”, but that’s what I’d say they were doing. And god bless the soul that gets in the way of an artist and his dream works.

Chuck Jones was always looking to better his product; so was Bob Clampett. They had different ways of going about it. Jones’ work with John McGrew meant that the filmmaking was pushed beyond the obvious and the artwork got unusual and daring. Check out the insane film cutting from 6:40 on in Conrad the Sailor. The artwork also turned more abstract in the layouts and backgrounds.

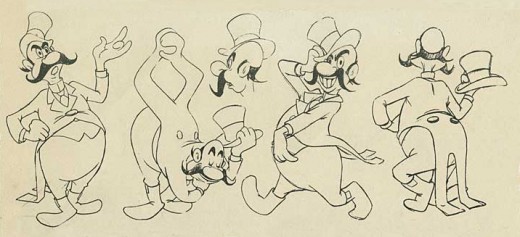

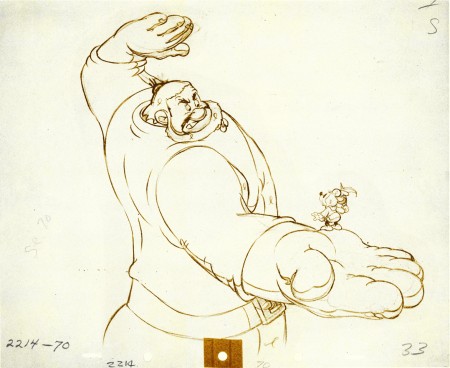

With Jones’ film, The Dover Boys, the animation was drafted to be daring as well. The animator, Bobe Cannon introduced smears. To pop a character from one extreme to another, accenting and parodying the 19th Century dramatic style Jones had sought. The character could move from one position to the next by smearing a couple of inbetween drawings and coming to a properly composed “hold.” It brought an unusual comedy bit to the scenes.

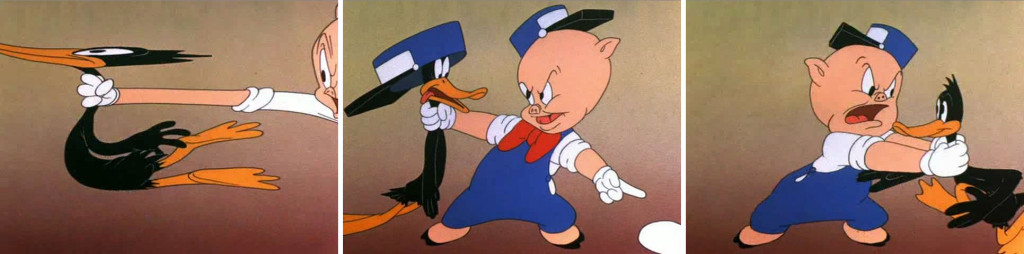

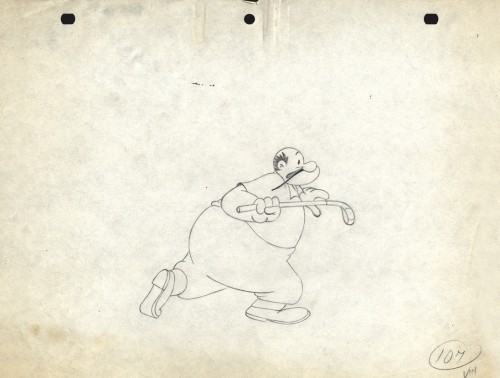

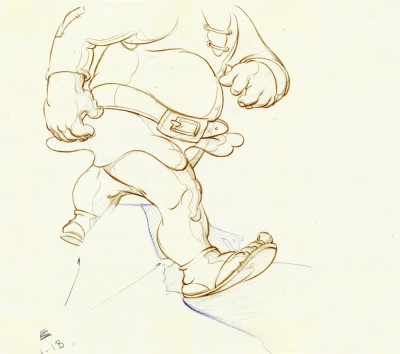

Frame by frame Cannon hurriedly smeared the artwork so that the character . . .

. . . could zip from one pose to another. This put the melodramatic action . . .

. . .blatantly into the action in a funny and purposeful way.

It also helped by accenting the peculiar track readings that Jones had caught from his actors. Immediately following The Dover Boys, the Jones team tuned out The Case of the Missing Hare. Smears abound as Bugs Bunny fights a magician against very stylized backgrounds. Cannon, Rudy Larriva and Ken Harris animated. No doubt Cannon’s smears were controlled a bit more as Chuck Jones experimented more with holds and freezes on his characters. John McGrew and Eugene Fleury designed them.

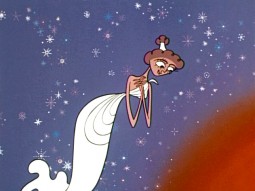

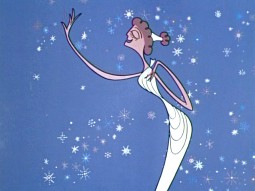

Cannon brought these “smears” into UPA with him, as an animator. He also started experimenting with the rule of “breaking of the joints” which meant that under no circumstances would an arm bend except at a wrist, elbow or shoulder. However, he allowed himself some distortion, flexibility to determine where the elbow was on the arm or how far the bend at the shoulder could be. Let’s just say he exaggerated. This was also an ideal form of animation for the limited animated practices at UPA. Grim Natwick had Nellie Bly corkscrew her arms around each other in Rooty Toot Toot. This was probably a direction Hubley called for in his quest for “modern art”. By this time, Cannon was already an Oscar winning director at UPA; Gerald McBoing Boing had won the previous year.

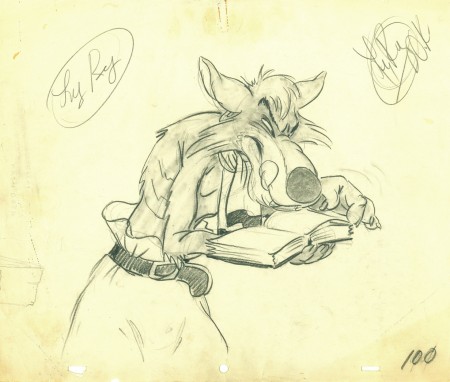

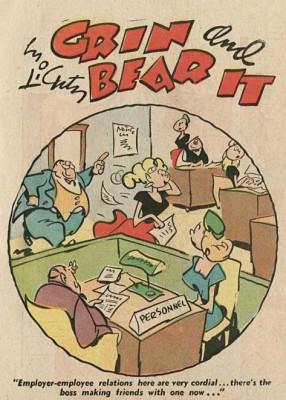

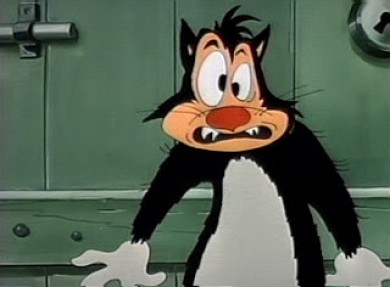

It was at the same time Cannon and Jones were developing these smear tactics for their drawings that Bob Clampett was talking with Rod Scribner. Scribner was an enormous fan of newspaper cartoonist, George Lichty. Scribner wanted to pull the designed looseness of Lichty into his animation and allow it to take control. Distortions would represent inner emotions, and Scribner was desperate to try it. Clampett agreed as long as he, as director, was calling the shots. He would tell Scribner when to “Lichty” something. They first tried it in “A Tale of Two Kitties” (the first Tweety & Sylvester cartoon.) They immediately took what they learned into “Coal Black and de Sebben Dwarfs.” Scribner used it wildly in relaying the emotional intensity of the characters. Now, they were not only distorting the characters on the inbetweens, they were visibly distorting the extremes as well. Not only were the characters’ surface emotions visible, but the internal emotions were allowed to run rampant.

It was at the same time Cannon and Jones were developing these smear tactics for their drawings that Bob Clampett was talking with Rod Scribner. Scribner was an enormous fan of newspaper cartoonist, George Lichty. Scribner wanted to pull the designed looseness of Lichty into his animation and allow it to take control. Distortions would represent inner emotions, and Scribner was desperate to try it. Clampett agreed as long as he, as director, was calling the shots. He would tell Scribner when to “Lichty” something. They first tried it in “A Tale of Two Kitties” (the first Tweety & Sylvester cartoon.) They immediately took what they learned into “Coal Black and de Sebben Dwarfs.” Scribner used it wildly in relaying the emotional intensity of the characters. Now, they were not only distorting the characters on the inbetweens, they were visibly distorting the extremes as well. Not only were the characters’ surface emotions visible, but the internal emotions were allowed to run rampant.

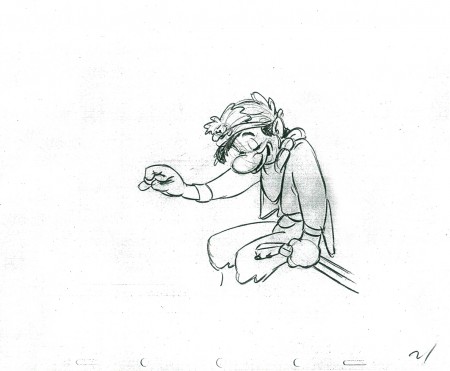

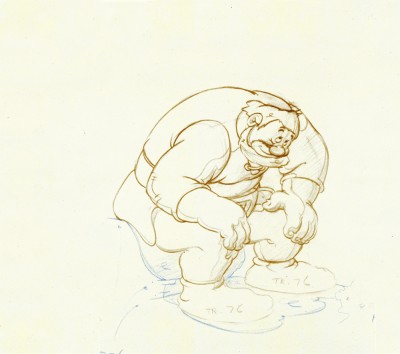

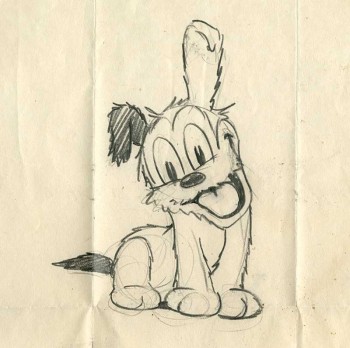

Rod Scribner had a different way of distorting.

The character would start off normally and distort by completely shifting . . .

. . . the masses of the character keeping the volume the same within . . .

. . . the body of the character who’d end up somewhat normal again.

The experiments between this animator and director were enormously successful, just as had been Jones’ experiments with Cannon and other animators under him. And these experiments continued to play into other films by both directors. The control was strong and personal and unique. Clampett and Jones were doing similar things for different reasons, however subtle.

On the East Coast, the animator, Jim Tyer was doing something altogether different. His style was bursting at the seams of control; he had been drawing his distortions more and more forcefully as his directors grew weaker.

On the East Coast, the animator, Jim Tyer was doing something altogether different. His style was bursting at the seams of control; he had been drawing his distortions more and more forcefully as his directors grew weaker.

I’m sure, at Paramount, he was kept under control. Assistants altered his drawings in their “clean ups” trying to pull Popeye back onto the model sheet. A number of them actually complained to me about it.

The kindest animator in the world, Johnny Gentilella had a dig as well, “He had difficulty keeping his character on model.” Once Tyer landed at Terrytoons, that was it. All was clear for his graphic distortions. The characters never appeared on model, never mind their ever having been “cleansed” in “clean-up.”

The kindest animator in the world, Johnny Gentilella had a dig as well, “He had difficulty keeping his character on model.” Once Tyer landed at Terrytoons, that was it. All was clear for his graphic distortions. The characters never appeared on model, never mind their ever having been “cleansed” in “clean-up.”

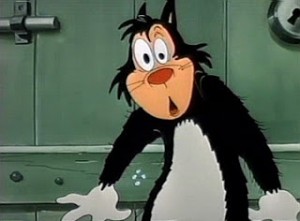

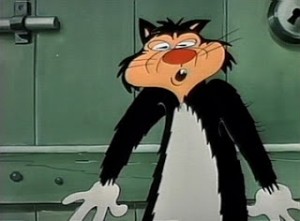

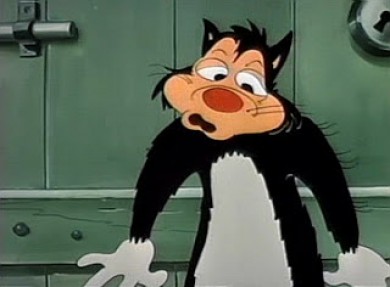

There was a difference with Jim Tyer, though. It would seem to have been more a graphic adjustment rather than an emotional one that Tyer was drawing.

The characters were not trying to break out of their skins emotionally, as they did under Scribner’s pencil. Here they stood out from everything else and every other animator’s style. There was no attempt by the Terrytoon directors to emotionally cast these graphic outbursts. A Tyer scene, wild as it might flow in its distortions, would be allowed to flow into the work of some very tight animator, then come right back to Tyer. One would expect his scenes to, at least, be the action scenes; but no, they could have been very

The characters were not trying to break out of their skins emotionally, as they did under Scribner’s pencil. Here they stood out from everything else and every other animator’s style. There was no attempt by the Terrytoon directors to emotionally cast these graphic outbursts. A Tyer scene, wild as it might flow in its distortions, would be allowed to flow into the work of some very tight animator, then come right back to Tyer. One would expect his scenes to, at least, be the action scenes; but no, they could have been very

quietly building up to the wild actions of another animator who would try to rein in the stylization.

quietly building up to the wild actions of another animator who would try to rein in the stylization.

The Terrytoons cartoons were all over the map, and in many a case they were held hostage by Jim Tyer. As a kid I enjoyed these outbursts, and I looked forward to watching another Mighty Mouse or Terry Bears cartoon to see what that crazy animator did. The problem, of course, was that Tyer’s animation separated from the film as a whole and broke down

the entire short it came from. Mark Mayerson talked about this at length in his great piece, “Jim Tyer: The Animator Who Broke the Rules” (1990). As he points out, ” Tyer’s work is animation’s equivalent of a train wreck or a freak show. It’s not something you’d necessarily choose to look at, but once it’s caught your eye it’s hard to look away.”

the entire short it came from. Mark Mayerson talked about this at length in his great piece, “Jim Tyer: The Animator Who Broke the Rules” (1990). As he points out, ” Tyer’s work is animation’s equivalent of a train wreck or a freak show. It’s not something you’d necessarily choose to look at, but once it’s caught your eye it’s hard to look away.”

This was unlike the work of Cannon or Scribner. All three are funny and to differing degrees. They,

all three, have different levels of depth. However, whereas Cannon worked his style with one key director and Scribner did the same, Tyer worked against his directors – at least, one would guess that was the case. I can’t imagine a Connie Rasinski even talking about the style except to chastise Tyer, possibly to his face. I’m sure things got easier for Tyer after UPA and their “wild” stylization made his work more acceptable and possibly even more comprehensible for these directors like Rasinski,

all three, have different levels of depth. However, whereas Cannon worked his style with one key director and Scribner did the same, Tyer worked against his directors – at least, one would guess that was the case. I can’t imagine a Connie Rasinski even talking about the style except to chastise Tyer, possibly to his face. I’m sure things got easier for Tyer after UPA and their “wild” stylization made his work more acceptable and possibly even more comprehensible for these directors like Rasinski,

Eddie Donnelly or a Mannie Davis. Tyer seemed to have an autonomy over anything he was working on.I’m surprised, in a way, that he, himself, wasn’t more concerned about his work fitting more appropriately into the cartoon as a whole. It’s doubtful that he would have mentally dismissed the films he worked on – other than for his own animation.

Eddie Donnelly or a Mannie Davis. Tyer seemed to have an autonomy over anything he was working on.I’m surprised, in a way, that he, himself, wasn’t more concerned about his work fitting more appropriately into the cartoon as a whole. It’s doubtful that he would have mentally dismissed the films he worked on – other than for his own animation.

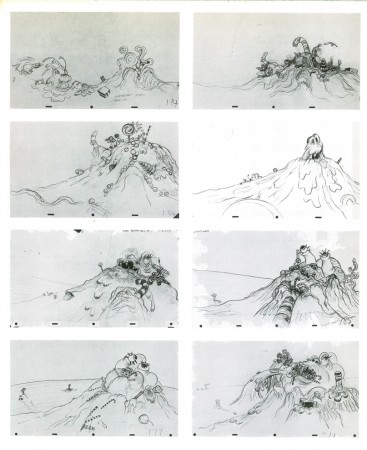

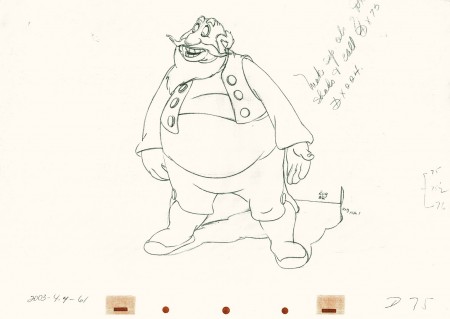

Even Tyer’s still work shows signs of blowing up at any moment, as can be seen in this storyboard still or this comic strip. Paul Terry, himself, must have accepted, if not supported, this work. Tyer did it for so many years.

There was one other key animator who distorted his characters, but his was a greater example than any other. For a short time, he was producing some of the most important animation of is time. We’ll tackle him (again) in another post.Of course, I’m talking about Bill Tytla.

Animation Artifacts &Commentary &commercial animation &Layout & Design &Models 12 Mar 2013 03:43 am

Larry Riley Recap Plus

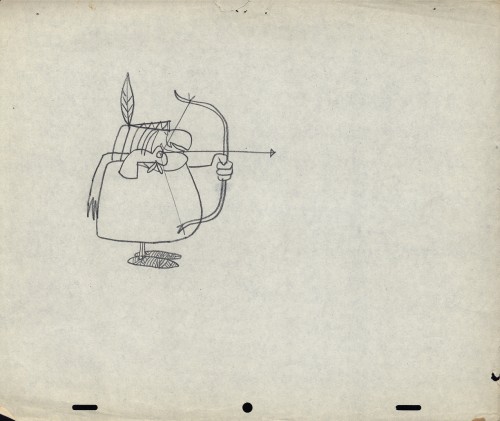

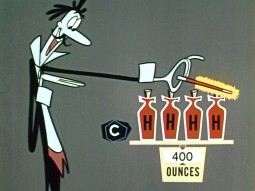

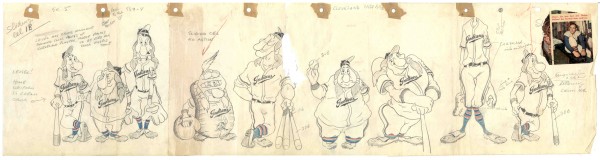

In celebration of the new season of baseball I have a couple of model sheets from a Paramount cartoon.

In celebration of the new season of baseball I have a couple of model sheets from a Paramount cartoon.

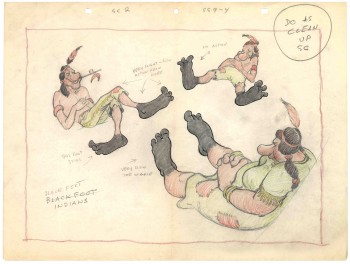

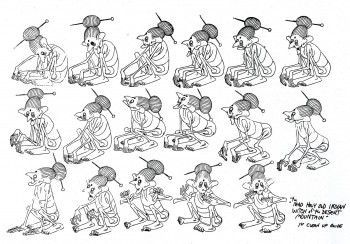

Larry Riley, a story writer, gave me these drawings back in 1972, but he never told me the film’s title. Thanks to Thad Komorowski and Bob Jaques – both left comments when I originally posted hese in 2007 – we know the drawings come from Heap Hep Injuns (1950).

______________(Click images to enlarge.)

Larry Riley was a wild guy. On my first commercial job at Phil Kimmelman & Ass. he and I were the inbetweeners working side-by-side on some of the Multiplication Rock series. Larry had had a long and busy career in animation.

He had been an asst. animator at Fleischer‘s, a story writer at Paramount, an animator at many studios. Like many other older animators, he ended up doing anything – including inbetweening at Kimmelman’s for the salary and the u-nion benefits.

The stories Larry told me kept me laughing from start to finish. There was no doubt he had been a writer for years. In a not very exciting job, it made it a pure pleasure for me to go to work every day to hear those hilarious stories. I can’t see Lucky 7 without thinking of laughing. It wasn’t the stories per se that were funny, it was his take on it.

Larry told me of his years at Fleischer’s in Florida where he was an assistant. He and Ellsworth Barthen shared a room, and, according to Larry, had lined one of the walls of their room with empty vodka bottles. Now, I’ve heard of frats doing this with beer cans, but doing it with vodka bottles requires some serious drinking. One of the many times I got to work with Ellsworth, I asked him about the story, and he reluctantly backed it up telling me what a wild guy Larry was.

Ellsworth was an interesting character in his own right. There were a group of lifetime Assistant Animators in New York when I started out. This is what they did and all that they aspired to do. They liked the steady work and didn’t want heavy pressure. Those I can name, off the top of my head, were: Helen Komar, Jim Logan, Gerry Dvorak, Tony Creazzo, Eddie Cerullo, Joe Gray, and Vincent Barbetta. They all have interestng stories I could tell. Maybe another time.

Ellsworth Barthen was one of these permanent Asst. Animators. He had his work life and he had his play life. Ellsworth lived in New Jersey with his brother and spent much of the time in his garden growing orchids. He had specialty breeds of orchids that he’d grow and enter in flower shows. Ellsworth loved it.

The other thing he loved was performing as Franklin D. Roosevelt. Just about everywhere he went, he took his pince-nez and would pop it on his eyes and go into character. Now I was born after Roosevelt had already died, so I couldn’t tell you if Ellsworth had been doing an accurate impersonation, but I saw him do it pretty often.

Ellsworth appearing on the Joe Franklin Show in NY

as Franklin D. Roosevelt. Joe Franklin is bottom left.

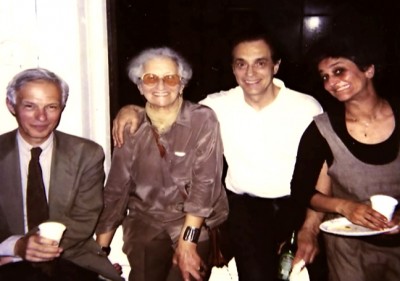

At Grim Natwick’s 100th Birthday Party in LA, Ellsworth came in character and stayed there all night. He was basically a big and shy guy, but this Roosevelt impersonation would bring him out and loud. Very curious character.

Back to Larry Riley:

________Forgive the racist pictures, but I guess they’re a product of their times.

Larry also told of a 3D process he’d developed for Paramount in the 50′s when the movies were all going 3D. I believe there were two Paramount shorts done in this process: Popeye: The Ace of Space and Casper: Boo Man. Larry offered to give me the camera on which he shot these films – he had it stored in his basement. He was afraid it would get thrown out when he died. I didn’t have room for it.

My regret; I still hear the sadness in Larry’s voice.

(When I originally posted this in 2006, Larry’s grandson, John, wrote to tell me that another collector took possession of the camera and kept it from destruction.)

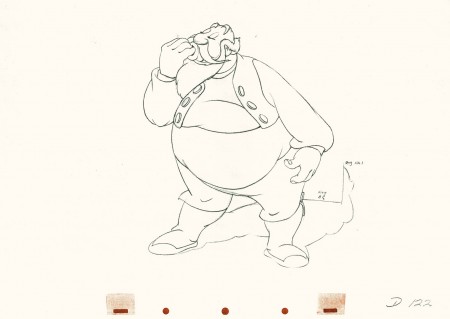

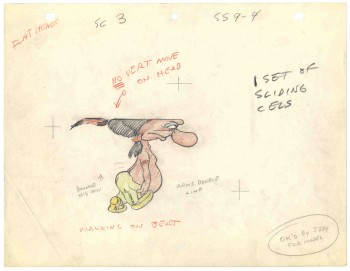

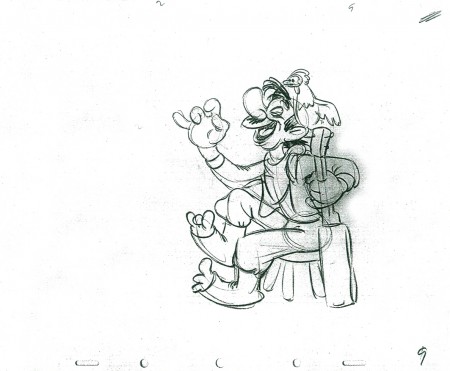

The animator who drew these is Tom Johnson (he signs the second one), and they were approved by the director Isadore (Izzy) Sparber per the first one.

The drawings are deteriorating, obviously. The pan above uses a lot of glue to hold it together, and that’s eating away at the paper.)

– This is the final model I have from Heap Hep Injuns a 1950 Paramount cartoon. Tom Johnson drew this image, prior to animating it, and Izzy Sparber directed the film. I’d heard some stories about I. Klein regarding this film, though he’s not credited, so I suspect he may have had something to do with model approvals, as well. Actually, he may have been the “Izzy” referred to on the pan posted yesterday.

– This is the final model I have from Heap Hep Injuns a 1950 Paramount cartoon. Tom Johnson drew this image, prior to animating it, and Izzy Sparber directed the film. I’d heard some stories about I. Klein regarding this film, though he’s not credited, so I suspect he may have had something to do with model approvals, as well. Actually, he may have been the “Izzy” referred to on the pan posted yesterday.

______________(Click images to enlarge.)

I was never a big fan of the Paramount cartoons. Growing up in New York, we’d always get Paramount or Terrytoons shorts playing with features in the theaters. Only rarely did a Warners cartoon or a Disney short show up. (I don’t think I saw a Tom & Jerry cartoon until I was 17 when they started jamming the local TV kidshows with them.)

Saturdays there was always the placard outside the theater advertising “Ten Color Cartoons”. A haughty child, I naturally wanted to know why they didn’t show B&W cartoons – that’s what we saw on television, and I usually liked them more. I must have been insufferable for my siblings to put up with me.

The starburst at the beginning of the Mighty Mouse cartoons always got an enormous cheer in the local theaters. I don’t remember ever hearing that for the Popeye or Harveytoons.

(I love that if you go on a “Google search” for images of Larry Riley, you get dozens of title cards from Paramount cartoons. Go, Larry.)

Commentary 11 Mar 2013 02:09 am

European Animation

I know I’ve written about some of this stuff before (repeatedly), and I hope my take on it here is a bit different. At least I’m leading somewhere different, so please have a bit of patience with the opening.

- When I was a kid, animation was in the dark ages for the general public. By that, I mean there wasn’t a hell of a lot of material available to allow you to know how it was done or learn how to do it. There were maybe a dozen or so books available.

- -

Of course the 40s Rob’t D. Feild book, The Art of Walt Disney. Some great information but not many illustrations. What are there are GREAT.

Of course the 40s Rob’t D. Feild book, The Art of Walt Disney. Some great information but not many illustrations. What are there are GREAT.

- The Preston Blair book, Animation, good and cheap. Very helpful for an amateur like me.

- Halas and Manvell‘s The Technique of Film Animation had more to do with animation as done in Europe, but it is extraordinarily helpful.

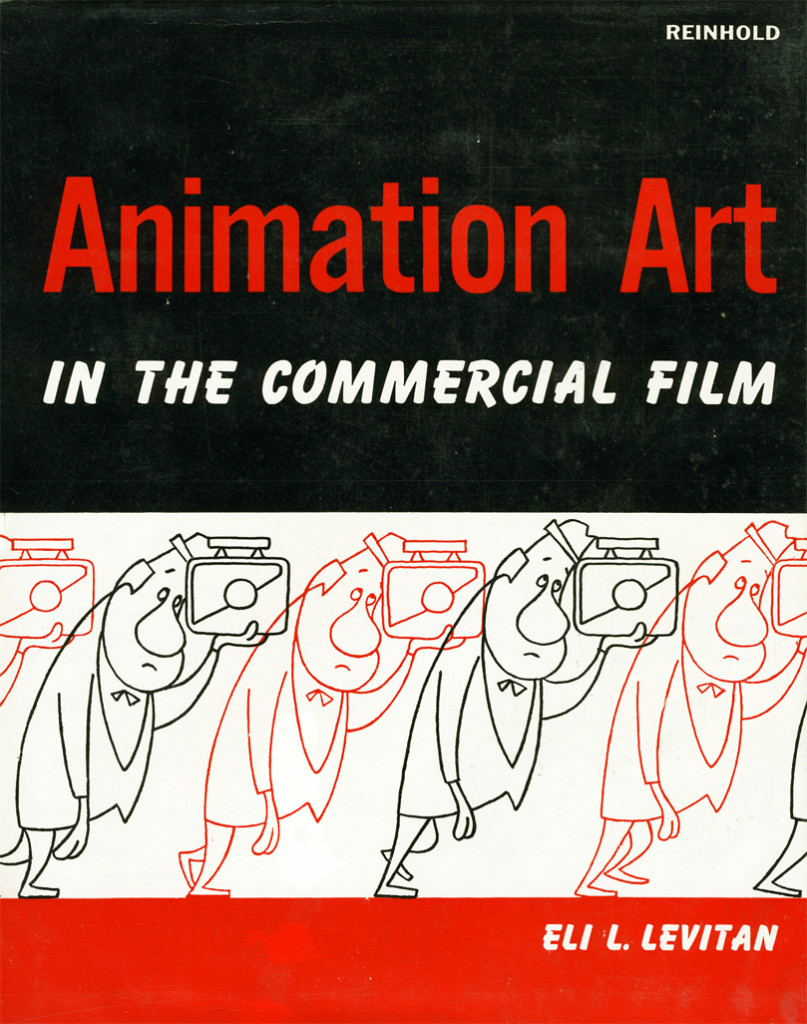

- Eli Levitan, an animation cameraman, had written several books. Animation Art in the Commercial Film is one of the better books.

There were a few others. My local library had them all, and I borrowed them endlessly and just about memorized them all. I owned the Preston Blair book (of course and my parents bought the brand new Bob Thomas Art of Animation for me Christmas 1958.

On ABC you had the Disneyland TV show which became The Wonderful World of Color when it moved to NBC. The Mighty Mouse Show was the staple on Saturday morning. Local channels featured Popeye and B&W Warner Bros cartoons.

I was completely intrigued with some silent cartoons that were run on the local ABC affiliate on early Saturday mornings. Every once in a while a sound Van Buren cartoon would pop up or a Harman-Ising MGM cartoon..

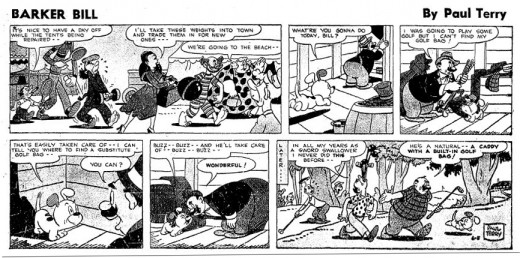

The show that also intrigued me was this horrible “Big Time Circus” starring Claude Kirschner (normally a VO announcer) as a ringmaster who talked to a $5 clown hand-puppet named “Clowny.” They showed cartoons, some B&W Terrytoons with Barker Bill and other early 30s things. They also showed a lot of foreign cartoons badly dubbed into English. They even had Russian features like The Golden Antelope serialized. They had a horrible title on the top of the film and a “The End” title pasted onto the end of the film. I used to tune in to see these B&W European and Russian cartoons. They moved so differently from what I was used to with the cartoons from the US. At 12, I could definitely see the difference and watched closely.

The show that also intrigued me was this horrible “Big Time Circus” starring Claude Kirschner (normally a VO announcer) as a ringmaster who talked to a $5 clown hand-puppet named “Clowny.” They showed cartoons, some B&W Terrytoons with Barker Bill and other early 30s things. They also showed a lot of foreign cartoons badly dubbed into English. They even had Russian features like The Golden Antelope serialized. They had a horrible title on the top of the film and a “The End” title pasted onto the end of the film. I used to tune in to see these B&W European and Russian cartoons. They moved so differently from what I was used to with the cartoons from the US. At 12, I could definitely see the difference and watched closely.

When I started collecting 16mm films I picked up a bunch of these shorts. The timing didn’t get any better.

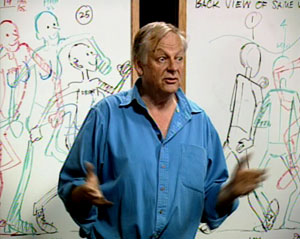

On my second day at the Hubley Studio, I met the notorious Tissa David who dug into me quickly for my bad inbetweening. She offered to teach me after hours, which I certainly jumped to accept. In that first contact with her, I mentioned that I had a potential job offer from Richard Williams and I might go to England. She immediately said to me, “Oh, please don’t go there. Stay here. Only the Americans know how to animate properly.” After all those years of watching Russian and European cartoons, I understood what she was saying. (I was also working for my real hero, John Hubley, so I had no real plans to go anywhere.) Dick Williams came to me a couple of years later with Raggedy Ann. By then, I was knowledgeable enough to run the Asst. & Inbtwng dept – about 100-150 people.

But then Dick Williams was changing everything. He was teaching his people in England how to animate the way Disney people did it. He brought those people into his studio to teach: Art Babbitt, Ken Harris, John Hubley, Grim Natwick, and others. I believe Williams changed animation throughout Europe. Mind you, the problems of all those years of history is still there, but it’s enormously better.

What do I call “European Animation”? Well, it’s all about the timing. The characters often move at such an even speed that there is no sense of weight or real character movement. Basically, all characters move the same. The Golden Antelope is all rotoscoped, so the movement is on ones and all traced off the live action. You can tell when it’s not; there’s a sameness in the motion. It’s almost like there are no extremes just motion.

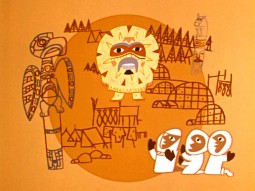

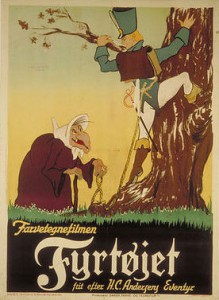

In Europe’s first attempt to imitate the US in a feature, The Tinderbox a 1946 film from Denmark, they were obviously trying to imitate the Fleischers of Gulliver’s Travels. Wild distortions and odd extremes but a lot of the evenly spaced timing. Consequently, with the distorted extremes moving in and out of position at an even pace, it’s doubly peculiar.

In Europe’s first attempt to imitate the US in a feature, The Tinderbox a 1946 film from Denmark, they were obviously trying to imitate the Fleischers of Gulliver’s Travels. Wild distortions and odd extremes but a lot of the evenly spaced timing. Consequently, with the distorted extremes moving in and out of position at an even pace, it’s doubly peculiar.

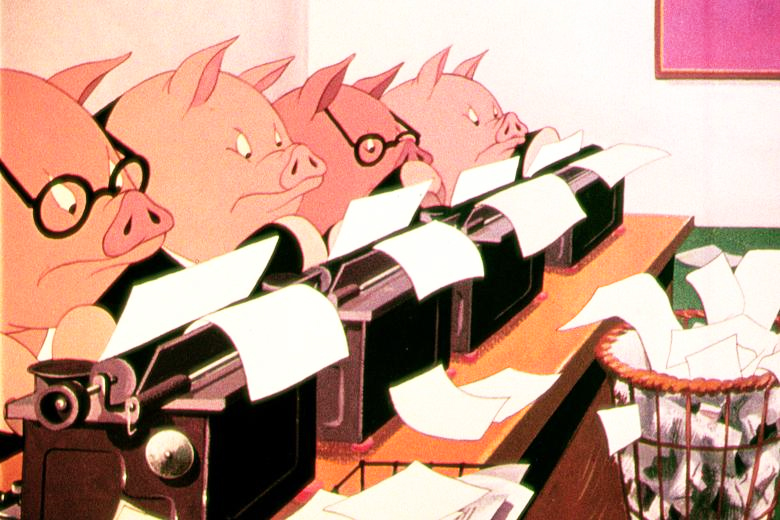

Halas and Batchelor‘s Animal Farm is so lethargic in its movement, it’s difficult to watch. However, whenever a Harold Whitaker scene pops up, it’s something to study. The guy was a fine animator. His work definitely sands out. He came from the Anson Dyer Studio, and had somehow learned to animate in the US methodology.

The Disney studio was having its effect , though as animators such as Borge Ring pretty much taught himself to go well beyond the basics of he European mold. He was close with a number of the Disney animators and studied Disney films religiously. His own personal style is definitely constructed from the US mold.

Even through The Yellow Submarine (1968), you see this flat style of animation. Of course, with the more graphic style of George Dunning‘s feature, the even pacing is better hidden in the mood of the piece.There’s also a lot of music that hides the timing problems.

Even through The Yellow Submarine (1968), you see this flat style of animation. Of course, with the more graphic style of George Dunning‘s feature, the even pacing is better hidden in the mood of the piece.There’s also a lot of music that hides the timing problems.

After Dick Williams, began his effort to alter the look of work coming out his studio, there was a big change in the look of work coming from all over Europe. Sure they slipped into and out of the old school of animation, but now they had learned from Art Babbitt and Ken Harris. (I wish they’d had more of Grim Natwick.) Take a look at the marvelous animation done for Bruno Bozzetto in the Ravel Bolero section of his 1977 feature, Allegro Non Troppo. To some extent, now, the best animation worldwide is coming out of England and France, especially from the younger animators.

So let’s take a look at the differences between the two styles..

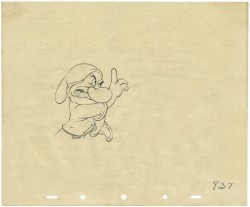

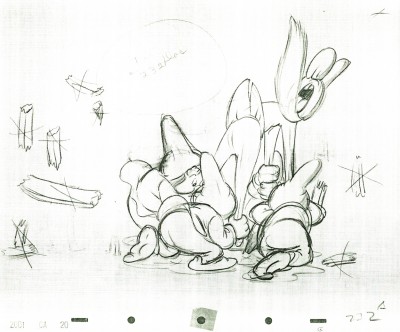

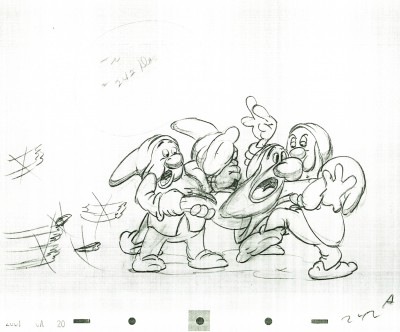

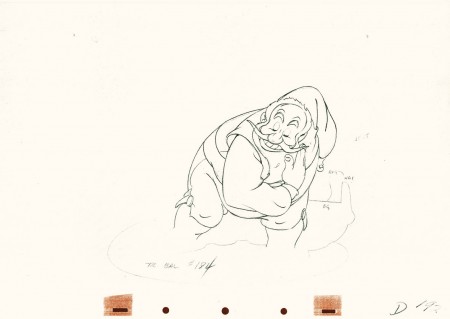

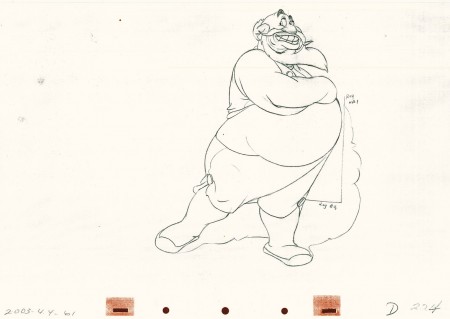

- The best of the US style can be seen in those dwarfs in Snow White or the Siamese cat song in Lady & the Tramp or Scar in The Lion King. It’s all in the timing.

- The European style is very obvious in Jiri Trnka‘s 2D animation as in The Four Musicians Of Bremen or Spring-heeled Jack. You can see it in about half of Sylvain Chomet‘s The illusionist (the other half was wonderfully done US style), or, as I’ve already written, Animal Farm – the entire movie.

The US tradition came directly from the wonderful work done mostly after hours at Disney’s studio in the 30′s. They learned how to time animation for weight, for mood, for expression and for balance. Bill Tytla, Marc Davis and Frank Thomas were brilliant at it (though they all did it). The word reached outside the Disney studio and others came into the fold: Ken Harris and Bobe Cannon, Grim Natwick and Rod Scribner, Jack Schnerk and Abe Levitow, Hal Ambro and Tissa David. There are another couple of hundred people I could include if we were naming names. These people all mastered their timing. They knew what they were doing and did it as planned. The animation never does what IT wants to do, but it is controlled by the animator and his (her) timing.

The European style is a very different animal. The timing is flat. It’s usually even paced and moves robotically forward, not always by going in a straight line. The weight is always soft; the emotion is almost nil. The drawings are often beautiful, but there’s no real strength behind that movement.

The European style is a very different animal. The timing is flat. It’s usually even paced and moves robotically forward, not always by going in a straight line. The weight is always soft; the emotion is almost nil. The drawings are often beautiful, but there’s no real strength behind that movement.

Things have changed quite a bit since the advent of Richard Williams and his work, but even there I see it at times. In Dick’s work, I mean, I sometimes see it. (Not surprising since I infrequently see it in Art Babbitt‘s animation. – and lest you think I’m biased, I often see it in my own work and have to rework it. (I’m not trying to hurt anyone here, I’m just reporting what I sense and see and feel.) Just talkin’ animation here. It’s basic and can so easily be bypassed. Animation is ALL ABOUT the timing. Norm Ferguson couldn’t draw very well at all, but he was one of the GREAT animators of all time. There was no even-paced timing in his makeup; the same has to be said of Tytla or Grim Natwick. Babbitt did do it. He was one of our great animators, but he infrequently paced his work in a very dull way. I could give you examples, but I won’t look for yourself, because when he’s good, he’s brilliant. Take the scene he did in The Thief and the Cobbler where the evil Vizier, Zig Zag, shuffles the playing cards.

A great example of what I’m talking about has all to do with Tom & Jerry. Take a look at some of those produced by Gene Deitch out of Czecheslovakia in the early 60s. Don’t compare this with the fully-animated shorts produced by Hanna & Barbera at MGM. No, compare it to the films done by Jack Kinney using a pickup studio. Most of the staff was free lance California employees. Turks without a space to work in the studio. Those Kinney films, badly animated though they are, are pure US-styled animation. The Deitch films are equally, poorly animated, but these also are animated with a European staff that animated the way a European would. The timing is rigidly even in its pacing.

You often get that European feel in the cgi work done today.

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve seen scenes where things suddenly go slack and move, seemingly, of their own accord in cg films. Perhaps the two arms will complete a motion that was started by an animator, and (s)he will allow the rest of the motion continue on its own to a final rest stop. It’s not animation anymore, it’s just a completion. I do quite dislike this when and if I see it. (Thought, admittedly, too often I’m not paying attention enough.) There’s a scene somewhere in Paperman where the male, standing in profile, has his two arms moving forward to a rest. They move at exactly the same speed, doing exactly the same thing, and it bothers me. Tissa certainly would have scolded me for allowing such a move to happen. I have to hope and believe that that’s what the animator wanted.

I had actually intended to keep going. One can’t really just say US and European animation styles. After all, there’s also the work out of Asia. The Japanese market, of course, is very different than the rest, and, thanks to what Miyazaki has been doing and his success in doing it, things are changing radically. Where he once blended in with the Anime animation that was all present, things are now changing to more of an emotional, Western appeal. My Neighbor Totoro started something, that changed wildly when he did Spirited Away and Ponyo. When I saw The Secret World of Arrietty, I knew things had changed completely. There was real character animation on the screen. One character was different from the next, and a lot of it had to do with the movement.

I had actually intended to keep going. One can’t really just say US and European animation styles. After all, there’s also the work out of Asia. The Japanese market, of course, is very different than the rest, and, thanks to what Miyazaki has been doing and his success in doing it, things are changing radically. Where he once blended in with the Anime animation that was all present, things are now changing to more of an emotional, Western appeal. My Neighbor Totoro started something, that changed wildly when he did Spirited Away and Ponyo. When I saw The Secret World of Arrietty, I knew things had changed completely. There was real character animation on the screen. One character was different from the next, and a lot of it had to do with the movement.

I was also fascinated with the work of Satoshi Kon, before his untimely death. His work was growing enormously with each and every film. The movies he made were adult in every sense of the word, and they were beautifully constructed, drawn and animated. I still go back to watch copies of his films. ________“Arrietty”

I was going to write about Katsuhiro Ôtomo, but I realize I’ve taken a sidestep. These are directors, and this article is about animators. In short, there is an Eastern style, and I’m glad to see that because of a couple of directors, they’re doing thier own take on the US version of animation character developement. It’s good to see it happening.

Essentially, the world is becoming smaller. Global animation styles are settling in, and I hope there will be a 2D animation so that the job can be complete in a few more years.

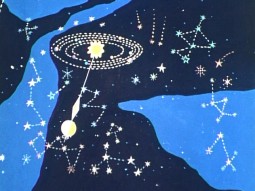

Animation &Commentary &Daily post &Errol Le Cain &Richard Williams 25 Feb 2013 05:28 am

POV

Next Friday, at the invitation of filmmaker-editor-director, Kevin Schreck, I’ll have the pleasure of seeing his recently completed documentary, Persistence of Vision. This is the story of the making of Richard Williams‘ many-years-in-the -making animated feature, The Cobbler and the Thief. I’m not sure of the film maker’s POV, but I somehow expect it to be wholly supportive of the insistent vision of Richard Williams in the making of this Escher-like version of an animated feature. A work of obsession.

It’s the tale of an “artist”, someone who sees himself as an artist, and continually pushes through the world with what would seem to be evident proof of such. After all, this man had single-handedly altered the face of 2D animation in a world that was about to throw it away with all its rich history and artistry and strengths. A medium that had developed through the years of Disney with giant, filmed classics such as Snow White, Pinocchio, Fantasia and even Sleeping Beauty. A medium that had drastically changed to 20th century graphics under the hands of people like John Hubley, Chuck Jones, George Dunning and many others and had just about reached a zenith where it was moving toward something wholly new, something adult.

Instead the medium took a turn in the wrong direction. The economics of television brought us back almost 100 years as films became more and more simplistic and simpleminded in the rush to be cheap. Even the Disney studio went for the poorest subject matter using cost-saving devices to sell their films. Films became shoddier and shoddier, and the economics ruled. The closest the medium would come to art was Ralph Bakshi‘s Fritz the Cat and Heavy Traffic, low budget movies that traded on racy material in exchange for an attempt at something adult, stories barely held together with editing tape. Animation was getting a bad name from every corner whether it was the sped-up graphics of Hanna-Barbera, the reach to the lowest common denominator with poor animation from Disney, or the shock and tell of Ralph Bakshi‘s filmed attempts at what he saw as art.

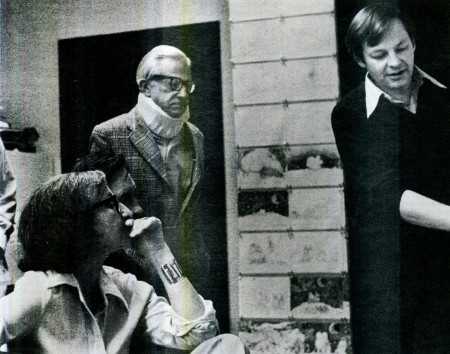

Williams took a different turn. He went back to the height of animation’s golden era, inviting artists such as Grim Natwick, John Hubley, Ken Harris and Art Babbitt to his London studio to lecture on the rules and backbone of the animation. He brought some of these people to work on a feature that he’d decided to create within his studio on the profits of commercials. These very same commercials financed the training of Dick and his young staff.

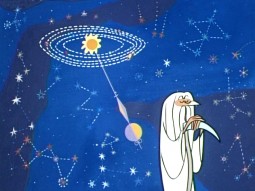

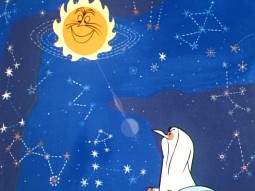

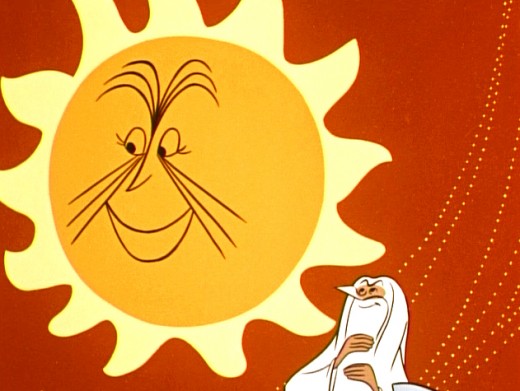

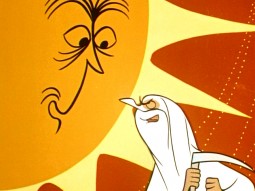

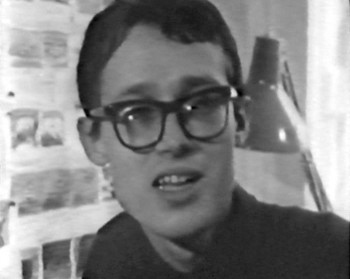

A documentary done in 1966, called The Creative Person: Richard Williams offers an excellent view of his studio. We see snippets of shorts Dick made with his own coin: Love Me Love Me Love Me (1962) or The Sailor and the Devil (1967) wherein we see the training of a young and brilliant illustrator named Errol le Cain. (Le Cain became known for his magnificent, glimmering children’s book illustrations. He was doing most of the backgrounds for The Cobbler and the Thief, and had certainly had a large part in its design.)

A documentary done in 1966, called The Creative Person: Richard Williams offers an excellent view of his studio. We see snippets of shorts Dick made with his own coin: Love Me Love Me Love Me (1962) or The Sailor and the Devil (1967) wherein we see the training of a young and brilliant illustrator named Errol le Cain. (Le Cain became known for his magnificent, glimmering children’s book illustrations. He was doing most of the backgrounds for The Cobbler and the Thief, and had certainly had a large part in its design.)

We see in this documentary the first hint of The Cobbler when it was called Nasruddin. It was based on a book of middle eastern tales of a wise fool whose every short story tells a new and positive anecdote. Dick had illustrated several books of these tales with many funny line drawings. The book was written by the Idres Shah who had undertaken a role within the Willams studio finding funds for the feature. Eventually, the two had a falling out, and Idres Shah left with his property. Williams took the work he had done as Nasruddin and reworked it into The Cobbler and the Thief. ________________________________Errol le Cain

We see in this documentary the first hint of The Cobbler when it was called Nasruddin. It was based on a book of middle eastern tales of a wise fool whose every short story tells a new and positive anecdote. Dick had illustrated several books of these tales with many funny line drawings. The book was written by the Idres Shah who had undertaken a role within the Willams studio finding funds for the feature. Eventually, the two had a falling out, and Idres Shah left with his property. Williams took the work he had done as Nasruddin and reworked it into The Cobbler and the Thief. ________________________________Errol le Cain

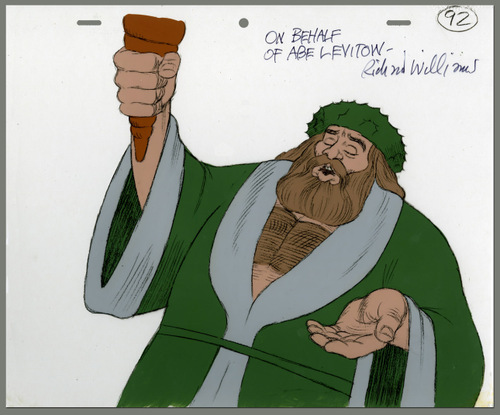

Meanwhile the work within his studio continued to develop, growing more and more mature. The commercials became the highlight of the world’s animation. Doing many feature film titles such as What’s New Pussycat (1965), A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1966), The Charge of the Light Brigade (1968) led to Dick’s directing a half-hour adaptation of The Christmas Carol (1971). Chuck Jones produced the ABC program, and it led to an Oscar as Best Animated Short.

Through all this The Cobbler and the Thief continued. Many screenplays changed the story and the stunning graphics that were being produced for that film were often shifted about to accommodate the new story.

By this time, Williams had developed something of a name within the world of animation. Strong and important animation figures went to his studio to work for periods of time. Someone like Abe Levitow taught and animated for the studio. (His scenes for The Christmas Carol are among the most powerful.) Many of the Brits that worked in the studio and then left to start their own companies were now among the world’s best animators.

By this time, Williams had developed something of a name within the world of animation. Strong and important animation figures went to his studio to work for periods of time. Someone like Abe Levitow taught and animated for the studio. (His scenes for The Christmas Carol are among the most powerful.) Many of the Brits that worked in the studio and then left to start their own companies were now among the world’s best animators.

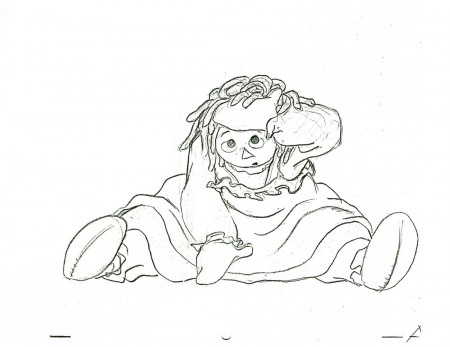

Williams had the opportunity of doing a theatrical feature adaptation of the children’s books The Adventures of Raggedy Ann and Andy and took it. A large staff of classically trained animation leaders such as Art Babbitt, Grim Natwick, Tissa David, Hal Ambro, Emery Hawkins and many others worked out of New York or LA as the company set up two studios to produce this film. Working for over two years, Dick’s attention was diverted to work away from his London studio, where commercials and some small devotion was given to The Thief by a few of the key personnel working there. Dick spent a good amount of his time in the air flying from NY to LA to NY to London and back again and again. He concentrated his animation efforts on cleaning up animation by some of the masters, rather than allow proper assistants to do these tasks. By doing this he was able to reanimate some of the work he didn’t wholly approve of. Entire song numbers were reworked by Dick as the film flew well behind its budget and schedule.

Eventually, the film finished in confusion and mismanagement, and Dick moved to his LA studio where he continued commercials and began Ziggy’s Gift, a Christmas Special for ABC.

From this he went back to his London studio and did the animation for Who Framed Roger Rabbit for producer/director Robert Zemeckis. He hoped that work on this feature, which won three Academy Awards, including a special one for the animation, would be the triumph he needed to help him raise the funds for The Thief and the Cobbler. Now that he was safely back in his own studio in Soho Square he felt more focused.

From this he went back to his London studio and did the animation for Who Framed Roger Rabbit for producer/director Robert Zemeckis. He hoped that work on this feature, which won three Academy Awards, including a special one for the animation, would be the triumph he needed to help him raise the funds for The Thief and the Cobbler. Now that he was safely back in his own studio in Soho Square he felt more focused.

A contract came from Warner Bros., and the work began in earnest.

Dick’s history wasn’t the best working on these long form films. Chuck Jones replaced him on The Christmas Carol to get it finished when work went overbudget and schedule. Dick was putting too much into it. Gerry Potterton finished Raggedy Ann when the budget went millions over with less than a third completed. Eric Goldberg took over Ziggy’s Gift, the Christmas Special for ABC, to get it done on time. On Roger Rabbit, the live action director stayed intimately involved in the animation after his shoot was complete. When it became obvious that things weren’t going well, he stepped in to complete that film.

In all cases of all of these films, Dick never left. He stayed on working separately on animation or assisting to try to keep a positive hand in the quality of the work that was done.

When The Cobbler and the Thief ran into very serious trouble, there was no secondary Director or Producer to come in and complete the work. Instead that job fell to the money men. The completion bond company, essentially an insurance company for Warner Bros. to make sure they wouldn’t lose their money if things didn’t go well, stepped in. They closed Dick’s studio and removed Dick from the premises. The boxed up and carted off all animation work done or in progress. It was all moved back to Los Angeles.

When The Cobbler and the Thief ran into very serious trouble, there was no secondary Director or Producer to come in and complete the work. Instead that job fell to the money men. The completion bond company, essentially an insurance company for Warner Bros. to make sure they wouldn’t lose their money if things didn’t go well, stepped in. They closed Dick’s studio and removed Dick from the premises. The boxed up and carted off all animation work done or in progress. It was all moved back to Los Angeles.

The Weinsteins, through their company, Miramax bought the film at auction and completed it with a poor excuse of an animation outfit they set up in LA. Work was also sent to Taiwan. The script was reworked trying to capitalize on the success of Disney’s Aladdin that had recently opened in the US. If Robin Williams‘ ad libbing could be such a success, imagine how well Jonathan Winters could do repeating that for a character who, in Dick’s original version, had no voice. Now he didn’t stop talking.

The new film failed miserably and deserved to do so. The primary audience, I would suspect, was the entire world animation community coming to look down on the artificially breathing corpse.

Richard Williams, himself, retired and moved far from the mainstream. He continues to work on small animation bits, but his primary work has been in making a series of DVD lectures revealing how animation should be done. This accompanies a well-received book he wrote and illustrated. Meanwhile, the animation community still hopes that something will emerge from that corner.

Richard Williams, himself, retired and moved far from the mainstream. He continues to work on small animation bits, but his primary work has been in making a series of DVD lectures revealing how animation should be done. This accompanies a well-received book he wrote and illustrated. Meanwhile, the animation community still hopes that something will emerge from that corner.

Dick turns 80 years old on March 19th. He’s still an amazing forceful and exciting personality. I wish I had more access to him (as does most of those who knew him back then.) He’s had probably the greatest effect on the animation industry of anyone since the late sixties. There are still studios thriving today on information they learned from Dick and his teaching.

If you’re unfamiliar with the blog, The Thief, I suggest you take a look.

Commentary 08 Jan 2013 06:41 am

Some Movies I’ve Thought About

- The feature length cut of The Cobbler and the Thief as was assembled by the remarkable Garrett Gilchrist can be found on line:

A beautiful copy of the workprint.

Let me tell you some thoughts I have about this incredible movie.

It’s sad watching it again. I had only the slightest of involvement on the film. It touched my life more than I touched it. I’d seen the documentary on PBS back in the early sixties. The Creative Person: Richard WIlliams. I was impressed. I scoured the newspapers and any other media searching for words about this film or its mad director, Dick Williams. His London studio had sent me a packet they produced full of publicity articles on papers slightly larger than 8 1/2 x 11. I read and reread all those non-bound pages, and they grew dog eared. Williams, his studio and his film was my obsession for a while. It seemed to be the only place where real animation was being done anymore, back in the sixties,.

John Hubley was my hero, and his studio hired me in NYC. It was supposed to be a three day line of employment, but the job ended up lasting the last six years of John’s life.

On the second day there, I met Tissa David. During our first conversation, maybe 15 minutes long, I told her that it was my intention to eventually leave New York to work in London for Dick Williams. (We’d written, and Dick said that he’d see me the next time he came through NY.) On telling Tissa this story, after she had just introduced herself by saying I had done the worst inbetweens she’d ever seen, she – in the most sincere and pleading voice I’d heard – said, “Please don’t leave America. We need you here, animation needs you here.” Or it was certainly something very much to that effect.

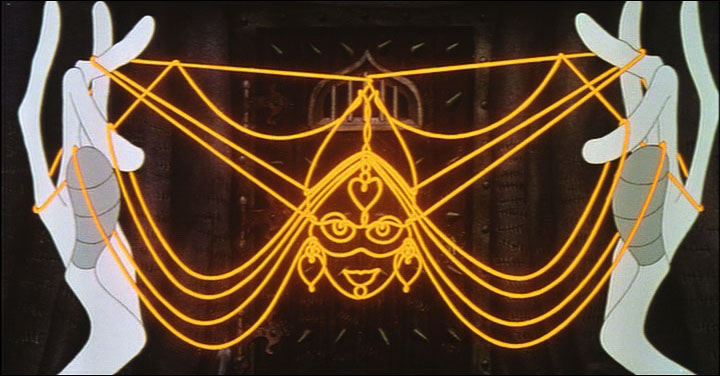

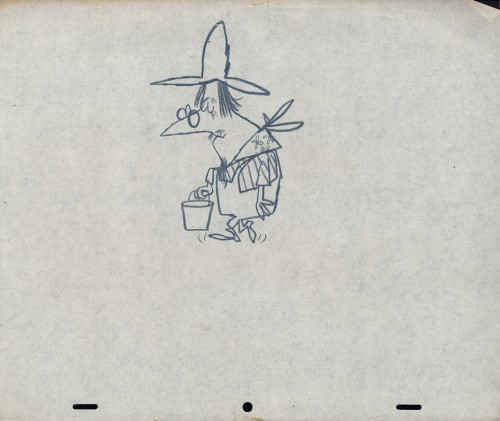

The story never quite worked, the Cobbler’s story never quite worked. I remember once reading the script and thinking it’s a feature length Road Runner cartoon. There was too much madcap humor at the Thief’s expense. I may have been wrong. The film seems to have been made to challenge animators. It’s difficult to animate the old Holy, Mad witch, but if you put her on a swinging basket while she talks, it’s even more difficult. Two uneven and oddly attached ropes makes it an extraordinarily difficult challenge. The weight and balance become everything. That’s what’s been done. It’s that way with every scene or character or motion in the film. If the challenge to the character in the scene can be made more difficult, then do it. Grim Natwick loved the challenge, helped develop the character, and Dick accomplished it.

The story never quite worked, the Cobbler’s story never quite worked. I remember once reading the script and thinking it’s a feature length Road Runner cartoon. There was too much madcap humor at the Thief’s expense. I may have been wrong. The film seems to have been made to challenge animators. It’s difficult to animate the old Holy, Mad witch, but if you put her on a swinging basket while she talks, it’s even more difficult. Two uneven and oddly attached ropes makes it an extraordinarily difficult challenge. The weight and balance become everything. That’s what’s been done. It’s that way with every scene or character or motion in the film. If the challenge to the character in the scene can be made more difficult, then do it. Grim Natwick loved the challenge, helped develop the character, and Dick accomplished it.

This, of course, is not only fine, it’s fun for the very talented animator – animators such as Dick Williams – but the problem is that it doesn’t really advance the story. The animation for this film is beyond complicated and done so extraordinarily well. The more you know about it, the more you realize how hard it was to do and how well it was done.

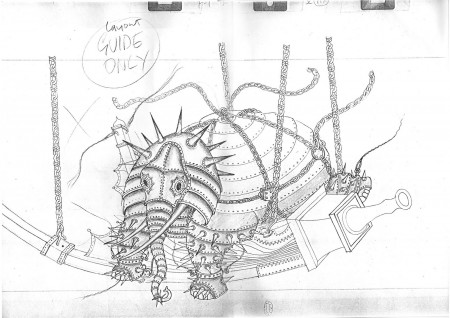

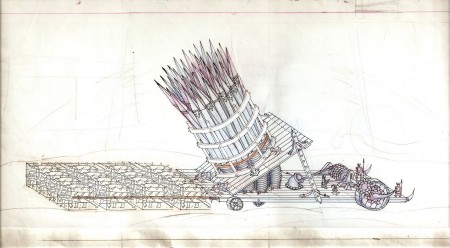

A couple of Roy Naisbit War Machines

Roy was one of the great Artists Dick introduced to animation.

Today, of course, we have computers that could animate most of the objects in this film. I’m not sure the “War Machine” would be any better, but it would have taken fewer man-hours. All that glorious drawing, Ink & Pt coloring and design was dependent on the perfect timing. The animation. Perhaps in time a computer would’ve gotten it.

In the first third of the film, there are two lovely scenes animated by Tissa David. Both are pencil tests of the princess, Princess Yum-Yum, in the bath. We’re looking over her shoulder and she looks back toward us, where we are off screen. The hair is up in her scenes, appropriate to a bath. In between there’s another pencil test scene of the princess with her hair down, and it no longer looks like the same character. The art is flatter. Tissa’s princess was voluptuous. As a matter of fact, her princess was two. Two mirroring twins who echoed each other in animation (anything to challenge the animator). Princesses Yum Yum and Mee-Mee. At the suggestion of the brilliant Jake Eberts, one of the two princesses was dropped. Mee Mee.

Tissa in working for Dick out of her NY apartment had purchased a Lyon-Lamb machine. Large and a bit cumbersome, this video machine came in the pre-computer days and was wholly a video tape machine. It employed reel to reel tape and was rather large. It had the distinction of being able to shoot something at 24 frames per second and also play back at that speed. After buying the machine, Tissa had built for herself a piece of furniture which acted as an animation stand that could sit alongside her desk. She saved all those video tapes (reel to reel, remember). She intermixed commercial animation she did for R.O. Blechman at the same time. (She needed the commercial work to be able to afford working for Dick Williams. He was self-financing his movie then, and Tissa loved working on his project. It was her only passion for several years.) This occurred for the years immediately following Raggedy Ann & Andy. Tissa had supervised Ann and Andy. I saw it all, I watched Yum Yum and Mee Mee grow. I heard all the stories first from Tissa’s side, then from Dick’s side. I was in a wonderful place in the world.

I also got to see several screenings of Dick’s developing workprint. Just prior to Dick’s making the Ziggy’s Gift TV special, he’d had a screening of 40 minutes of the feature. Many key people were there, and I can remember a few of them. Tom Wilson (Ziggy’s creator) was there with Lena Tabori. They were a couple, though I don’t think romantically. She was an editor who had developed many big Disney art books for Abrams before forming her own company, Stewart, Tabori & Chang and Welcome Books. She was the daughter of actress, Viveca Landfors. She, Wilson and Williams were the producers of Ziggy’s Gift, though ultimately Dick Williams was pushed out when the budget continued to rise as it did on most Williams films. Midway through production, Eric Goldberg got the chance to take the directorial reins and complete the film in a make-shift studio in LA. It was a packed screening. I sat next to Chuck Jones with Sidney Lumet sitting on my left. We three had great things to say about what we’d seen afterwards. How could you not? The animation, coloring, graphics, everything was extraordinary. There was no hint of a story in the 40 minute presentation; I was starting to notice that. I can’t remember many animation people there, though Willis Pyle was one. Tissa, of course, was there. She was getting to see her pencil tests projected.

I also got to see several screenings of Dick’s developing workprint. Just prior to Dick’s making the Ziggy’s Gift TV special, he’d had a screening of 40 minutes of the feature. Many key people were there, and I can remember a few of them. Tom Wilson (Ziggy’s creator) was there with Lena Tabori. They were a couple, though I don’t think romantically. She was an editor who had developed many big Disney art books for Abrams before forming her own company, Stewart, Tabori & Chang and Welcome Books. She was the daughter of actress, Viveca Landfors. She, Wilson and Williams were the producers of Ziggy’s Gift, though ultimately Dick Williams was pushed out when the budget continued to rise as it did on most Williams films. Midway through production, Eric Goldberg got the chance to take the directorial reins and complete the film in a make-shift studio in LA. It was a packed screening. I sat next to Chuck Jones with Sidney Lumet sitting on my left. We three had great things to say about what we’d seen afterwards. How could you not? The animation, coloring, graphics, everything was extraordinary. There was no hint of a story in the 40 minute presentation; I was starting to notice that. I can’t remember many animation people there, though Willis Pyle was one. Tissa, of course, was there. She was getting to see her pencil tests projected.

In time, things broke somehow between Dick and Tissa, and she was pulled from the project. It broke her heart, but she never once mentioned how or why to me. Dick was like that. He loved an animator (or any craftsman/artist) to death until he didn’t. Eventually, he’d worked up enough venom to decide, finally to split from the person. Things might right themselves again, but most people didn’t even know what was wrong. (The same happened between me and Dick. I know why he stopped caring for me, and I know when we split. I didn’t stop loving him or what he was doing. He came close to animation “Art”, there in the seventies.)

- As long as we’re posting Richard Williams‘ remarkable movies available on-line thanks to the work of Garrett Gilchrist, let me direct you to this one movie title sequence.

Prudence and the Pill was an comedy done in the sixties starring David Niven. It got its share of attention thanks to the title. The “Pill” was in the headlines and had made its way onto many newscasts when Congress legalized the contraceptive for women. Richard Williams studio did the titles and credits for this movie, and one thing stands out about them. Sharing the title with Dick Williams is the incredibly talented artist, Errol LeCain. He is credited as “animator”. The only other “animator” credit listed for this genius of an artist was for the Sailor and the Devil.

Honestly, I’ve been hooked on The Life of Pi. I saw the film in a theater twice, once for myself and the second time I went back to see it for Heidi’s sake. On the second viewing she seemed to love it more than I did. I found some things that bothered me, but I couldn’t really respond properly to them. Then this past week I got a new DVD player, and I tried it out, once the basic part of it was hooked up. The Life of Pi, a screener copy, was played to test run the machine. I was hooked up. I couldn’t stop watching it. All the faults I’d found on the second screening melted away, and I loved it again.

The Mychael Danna music played in my head over and over and over. I watched those opening credits at least another half dozen times. They’re beautiful and magic. It’s still playing in my head while I write this.

I wrote to the Effx house Rhythm & Hues saying I’d like to write about the film and its Effx. I haven’t heard back from them. I’ve been annoying enough about this subject that I received a comment from James Nethery saying he’d contacted a Rhythm & Hues animator asking if he’d be interested in being interviewed by me about PI. Thank you, James. That’d be fun.

For me, this year, the best animated scenes were many of those of Richard Parker, the tiger, in Pi. I was also equally astounded by most of the work of the Gollum in The Hobbit. One is straight cgi; the other is what used to be called “motion capture” and is now something much much more. There’s real feeling in both those films, and in both those films those characters exist. There can be no question of it. In essence I have a theory that this – the work in these two films and others like it – is the real purpose of computer crafted animation. Some people have learned how to make a living by faking little dolls talking, but that work – to me – doesn’t have far to go. It’s all in the writing for those films, and writing lately, especially for animation, is poor. Anmation, itself,

is stunned, stultified, unable to advance given the short sidedness of the “Producers”. This would seem to be the era of its greatest potential growth, but then some of our finest animators are forced into an early retirement. Milt Kahl, Frank Thomas and some others were afraid to retire for fear of animation dying. Perhaps it has.

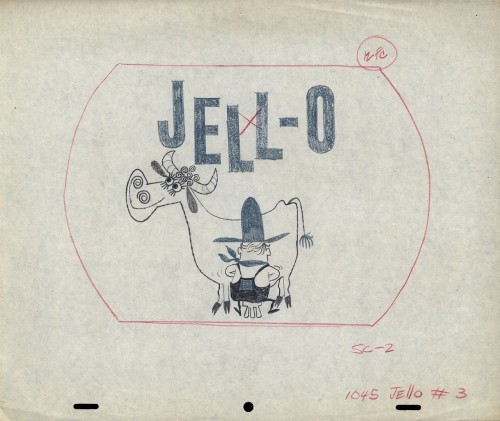

Animation Artifacts &commercial animation &Layout & Design &Models &UPA 21 Nov 2012 06:56 am

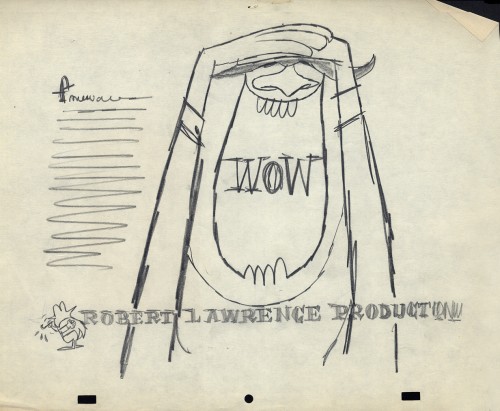

Robert Lawrence Prods. – part 1

- Robert Lawrence Productions was a thriving studio in New York in the days post-UPA. Many of the animators moved from UPA, once they closed, to Robert Lawrence. Grim Natwick/Tissa David worked there (freelance), Lu Guarnier/Vince Cafarelli worked there, and consequently, Vince collected a lot of artwork from the spots he did. This post features a lot of that artwork. You’ll see how great the design and styling was at the studio, even though I don’t know what clients or sonsors they were done for. The designers certainly took off where UPA left off.

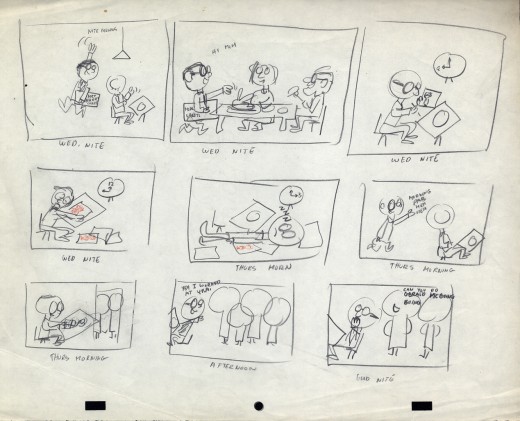

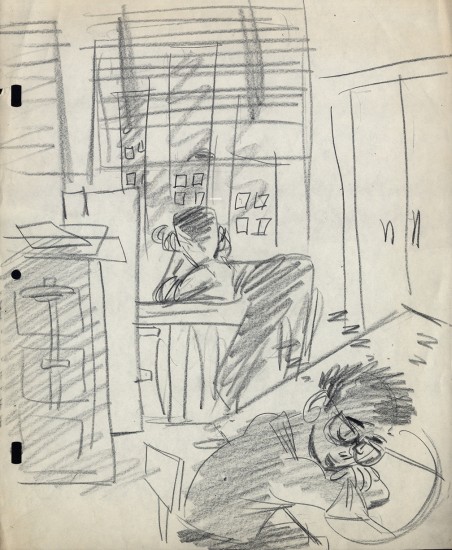

But first, let me share two in-house studio gags done at UPA.

1

1

2

2

At UPA – NY, Lu Guarnier was the only animator

who had a window. Vince Cafarelli and Pablo Ferro

were Lu’s Assistants/Inbetweeners, so they also

had the luxury of a window.

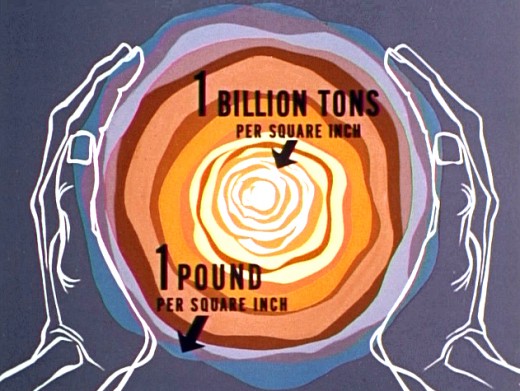

- OK, now onto Robert Lawrence. The more I look into this company’s work the more impressed I am. The quality of designers and animators on board was extraordinarily high. I have a lot of Layouts for films that are completely lost. I’m not sure what most of the images are for or what the stories of the spots was. I just have drawings, and most of them are impressive, even more so in some ways than much of the UPA work I’ve seen.

So let’s take a look.

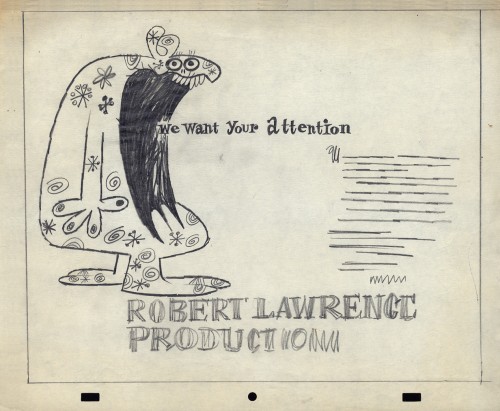

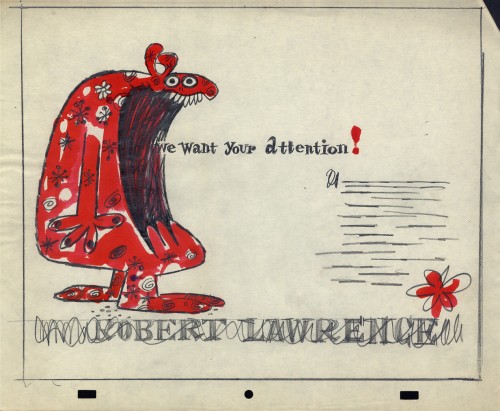

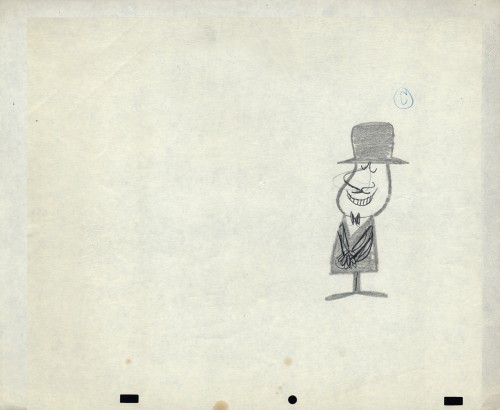

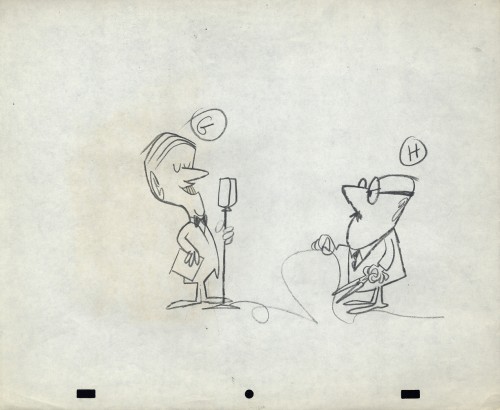

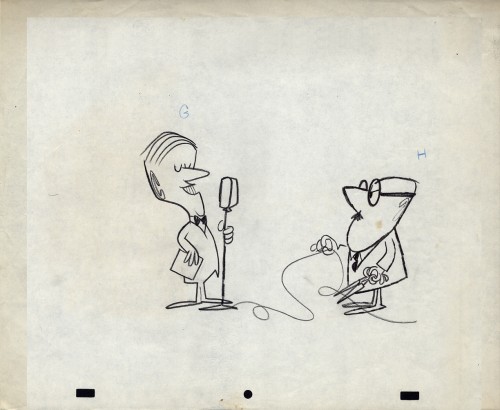

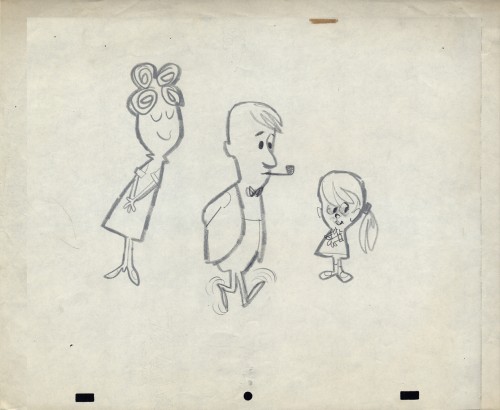

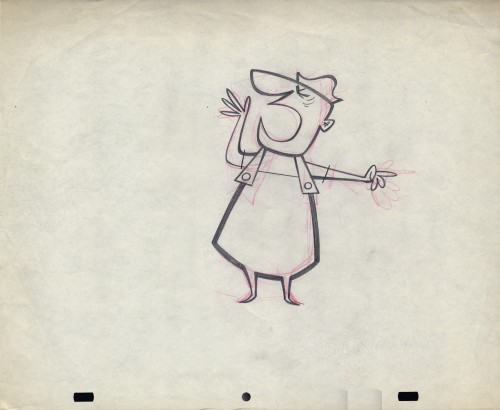

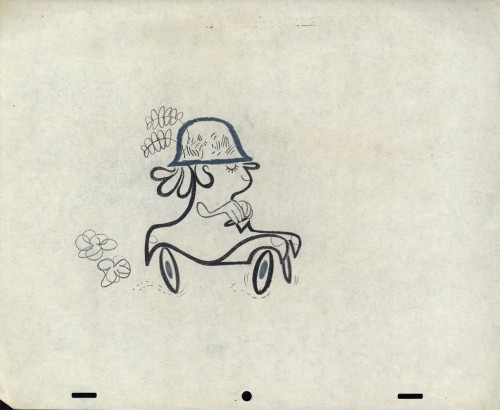

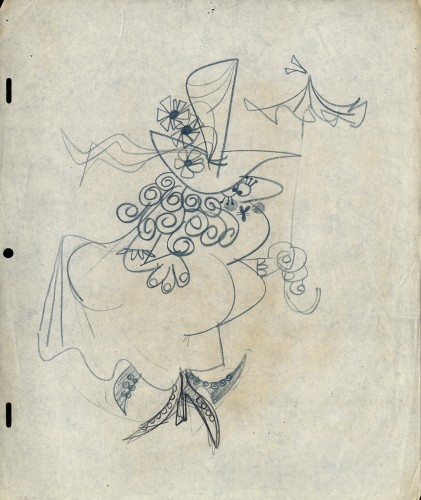

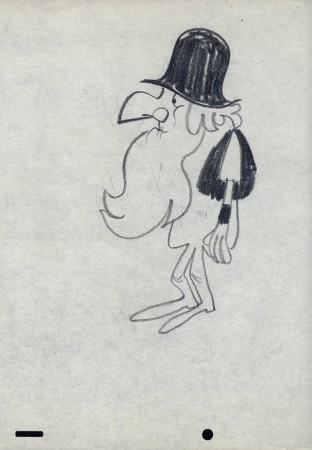

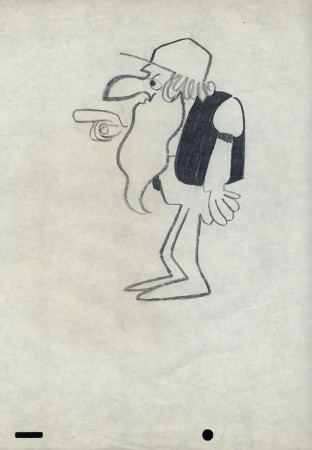

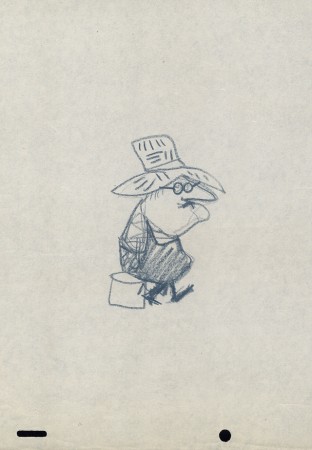

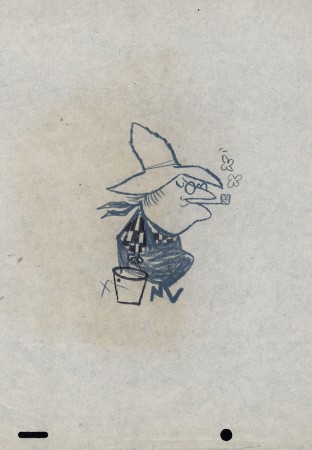

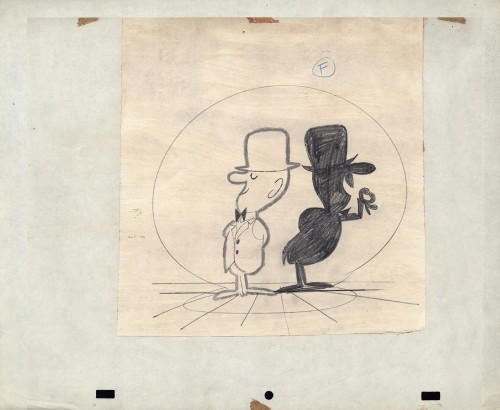

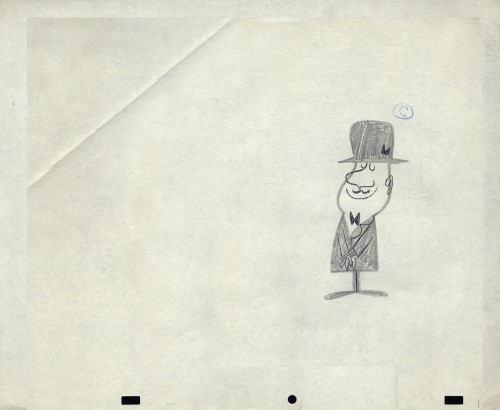

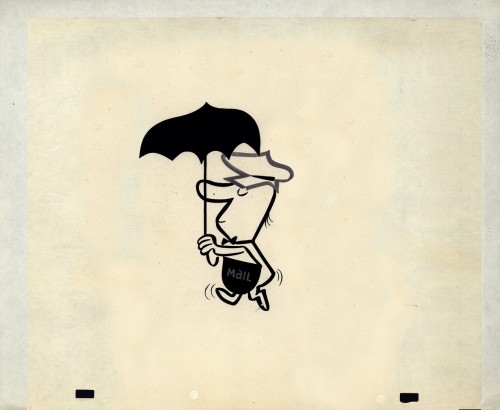

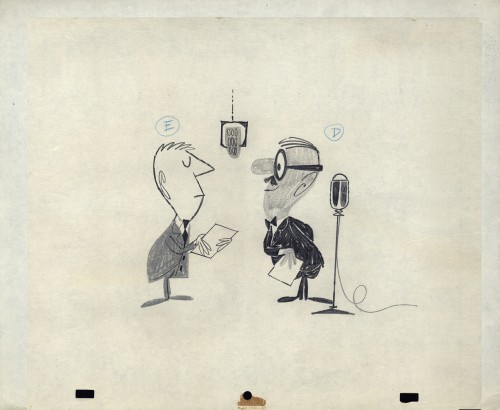

First there is the promo art. As an introduction to the company, here are four self-promo pieces that were used as trade ads for the company.

I’ve assumed that these images were created for a print ad in some magazine or another. There are three of them; one comes in a 2-color version.

1

____________________________

1

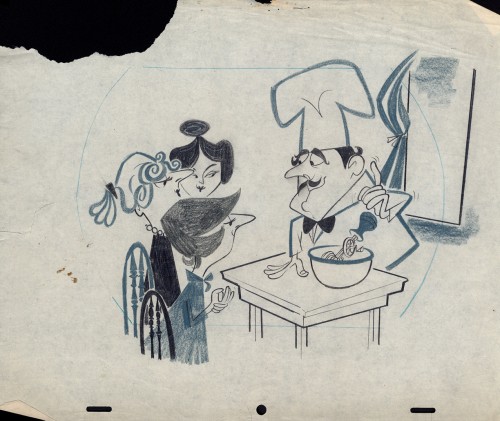

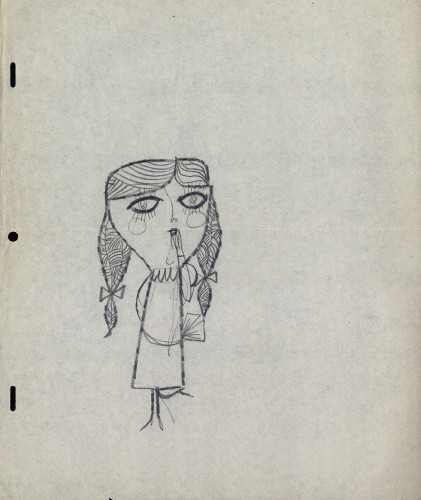

____________________________Now we get into some of the fun stuff. Here are the layouts done in a million styles, all beautifully drawn and designed. I feel like I want to say thank you to some of the artists involved. If only I knew who the artists were. The drawings and cels were all done on paper with a “Signal Corps” hole-punch. (Looks like Oxberry, but the center hole is the same diameter thickness as the square pegs.)

1

1This is a beautiful gag told a million times,

but done perfectly in this drawing.

3

3

The inked arms in #1 are the variant. (Possibly a correction?)

4

4

A cel not opaqued but beautifully inked.

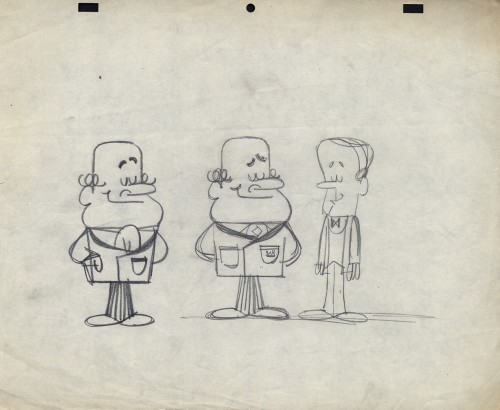

5

5

Obviously #5, 6, & 7 are the same characters in development.

It looks like #5 is probably the finished model.

10

10

This looks a bit like Howard Beckerman’s style, but I’d

probably bet against that. The characters aren’t cute enough

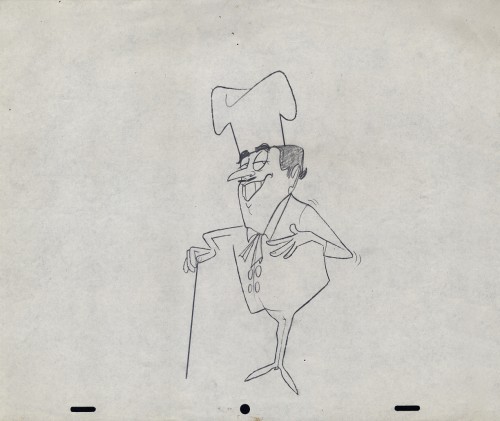

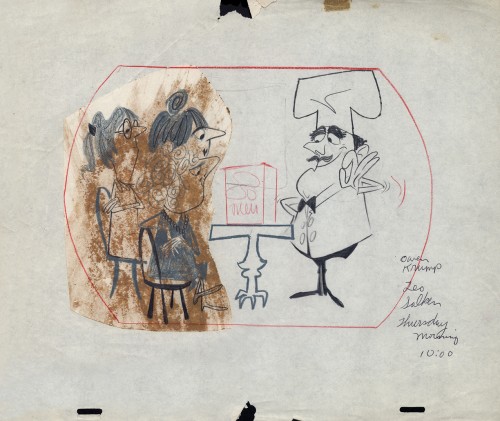

12

12

There’s a whole series of chef models

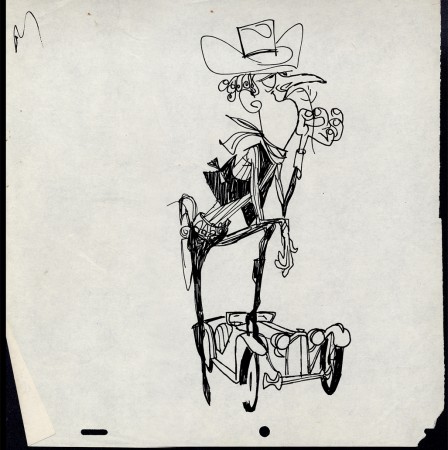

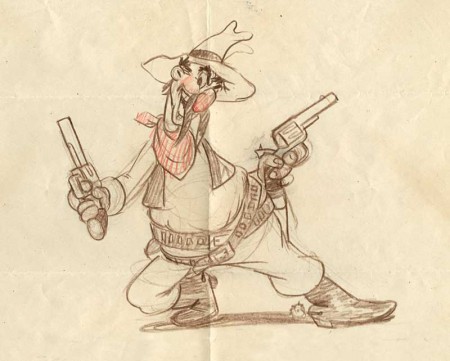

Then there’s a series of Cowboys.

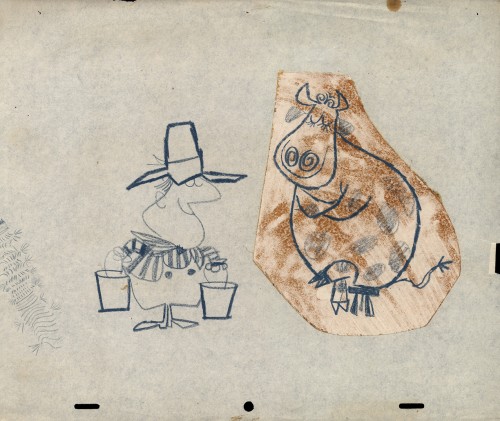

24

24

Then there’s the farmer milking the cow. Casting problems.

Commentary &Tissa David 05 Nov 2012 07:27 am

Speeches

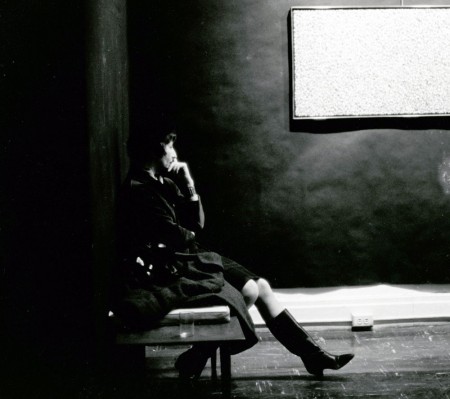

At the memorial service for Tissa David five people gave speeches. I have some of those talks and am posting them here. I also have some photos that I’ll post with them. The photos are identified at the end of the post.

The entire evening was hosted, essentially, by Tissa David, herself. A 90 minute video shot at NYU has Tissa talking about her career and animation, in general. I’ve chosen a lot of clips from this video. Our entire program starts with Tissa talking to the audience about her love for animation. Short clips then precede every section of later film clips screened, and the very last word of the evening is also Tissa’s.

John Canemaker was the first speaker:

- Sunday in the Park with Tissa.

I walk across Central Park at noon to Tissa’s residence on East 83rd Street, a cozy one-bedroom apartment that always smells of baked apples and spices. It’s where she has lived since coming to New York from Paris in 1956; and that’s the year she began working as assistant to master animator Grim Natwick at UPA Studios, then located on Fifth Avenue.

It is a perfect autumn day: crisp and cool, trees in full-color spectrum, bright sunlight. The New York City marathon is in full swing. Barricades, crowds cheering the runners, detours to get you where you need to go. Friendly, happy people everywhere. New York City at its gridlocked best!

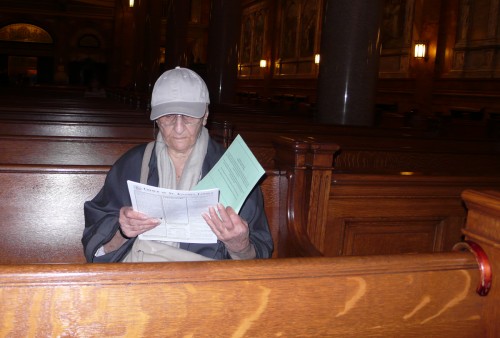

Tissa is waiting patiently outside her building, age 90 and ready to go. She wears a white peaked cap, purple/pink sweater and a stylishly long, beige raincoat over wool slacks and shiny black shoes. And she holds a rubber-tipped black cane.

She attended Catholic mass this morning, as she does every day at St. Ignasius Loyola, a church around the corner on Park Avenue run by Jesuits. As is our custom, I lean down to air-kiss one cheek, then the other, saying, “in the European manner.” She smiles and mimics me: “Yes. In the European manner.”

She takes my arm as we walk very slowly toward the Metropolitan Museum of Art two blocks west of her apartment.

She expresses interest in seeing the new Met galleries for “Art of the Arab Lands.†Both sides of her family are Armenian and the rugs of the Arabs stir her, she says.

“Have ever been to Spain?†she suddenly asks.

“Barcelona,†I answer.

“Barcelona is not Spain,†she responds. “It is — Barcelona. I mean a city like Granada, such a beautiful city. The Moorish influence in the city’s architecture and art.â€

Tissa has strong opinions about everything, especially art. I remember some years earlier running through a gallery at the Met containing one of Damien Hirst’s dead animals in formaldehyde, trying to keep up with Tissa as she hissed like a cobra: “Diss-gusting! Disssssss-gusting!â€

Her tastes are eclectic, but she maintains a special passion for Giorgio Morandi, who once said, “Nothing is more abstract than reality.†There is something in Morandi’s quiet, reclusive, deeply thoughtful, and pared-down paintings that speak to her on both personal and professional levels.

Today, however, instead of entering the museum she prefers that we walk; or, as she pronounces it in her soft Hungarian accent, “ve vauk.†Passing windows containing the Temple of Dendur, we pause. The slightly uphill route winds Tissa and she points her cane toward a cement wall. We sit watching marathon runners dash past, cheers erupting from the young crowd around us who greet the exhausted competitors, who have run for hours through all the boroughs and down Fifth Avenue and into the park for a finish near Columbus Circle.

A runner in a Superman costume hobbles by. Tissa is enjoying everything about the moment and the day, and so am I.

We talk of mutual friends. She remarks how happy she is that Michael Sporn is working on a new film. She says how much she loves Emily Hubley’s feature, The Toe Tactic.

Emily’s father, the legendary animation designer/director John Hubley, defied sexist barriers against women animators in the 1950s and 60s by hiring Tissa to animate several prestigious commercials and shorts. Tissa loved working for him, even if, she candidly notes, he was “cheap†when it came to salaries.

After ten minutes or so, we continue down the path and sit on a bench in the sun near Greywacke Arch, as runners gallop and limp across the bridge.

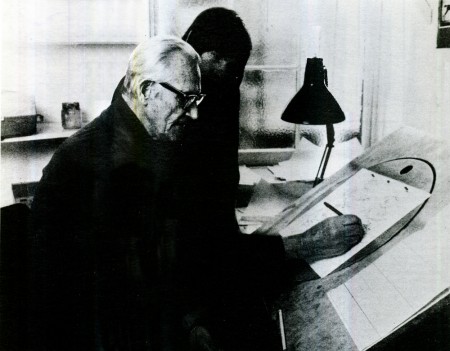

Inevitably, Tissa speaks of her longtime mentor Grim Natwick. And soon comes the mantra that is well-known to all her friends: “I really learned everything I know about animation from Grim.â€

She learned her lessons well. After Natwick retired, she slowly became recognized as one of the world’s great animators, and a pioneer who forged a brilliant career in a male-dominated industry. Charm, vivacity, female sensuality radiates from her superbly staging and well-timed animation, which is weaved into an admirable economical style. “You don’t do many drawings, “ she often advised novices, “but you know how to use them.â€

She thinks about animation constantly. She wonders how she would animate the Met’s splashing fountains. She ponders the numbers on digital clocks, which change shape instantaneously.

“I stare at the numbers,†she says, “and think about how I would animate the change from one to the other.â€

“It isn’t fully metamorphic,†I suggest, “but a decision about where the animator would ease into the new change.â€

Tissa thinks about that. “I would make the inbetween drawing closer to the ‘old’ number before the change,†she decides, “so there is a snap into the new number.â€

I ask Tissa if she ever wanted to marry or was in love. “Oh yes,†she answers. “I was in love many times and wanted to marry a doctor. But I was glad that he was shot by the Russians.â€

Seeing my shocked expression, she quickly adds, “I mean that it was better that I never married him because I would have quickly been miserable and it would have never worked out.â€

What about Grim?

Laughing, she says she loved him and he loved her, but it was never a romantic love. “He was my teacher. He was like my father.

“The greatest love of my life,†Tissa admits, “ was the art of animation.â€

She reflects that parts of her life have been hard. I assume she’s referring to the 1944 siege of Budapest, and her daring escape from Communist Hungary, or difficulties through the years finding her way as a female artist.

But she is thinking of more recent and personal troubles. “Between 2000 and 2010,†she explains, “I lost two brothers, two sisters, nephews and a niece. The loss of so many loved ones was almost overwhelming. I’m still angry with my younger sister Margit for dying and leaving me. She killed herself with smoking,†Tissa explains with bitter sadness.

We make our way up Fifth Avenue, then turn eastward toward her apartment.

“Thank you, John. It was really great to get out and valk.â€

I thank her for the opportunity to escape my cloistered work habits.

“You’re a long distance runner,†I say, “like the marathon racers.†She smiles and reminds me that I wrote that line in 1977 as the heading of her chapter in my first book The Animated Raggedy Ann & Andy. I don’t remind her that the full title was “Tissa David: The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Animator.â€

At her apartment house, we air-kiss “in the European manner.†My offer to help her down two steps to the front door is refused.

“I can do it,†she insists.

And she did.

This talk was followed by clips from the Hubley films:

Cockaboody

Eggs

Everybody Rides the Carousel (the Meryl Streep sequence)

Howard Beckerman followed John Canemaker

- Tissa David

Tissa, after working at Paris based studios, entered New York animation in 1955 at UPA situated diagonally across from the Museum of Modern Art and John and Faith Hubley’s Storyboard, Inc. It was the right place for her.

Tissa, after working at Paris based studios, entered New York animation in 1955 at UPA situated diagonally across from the Museum of Modern Art and John and Faith Hubley’s Storyboard, Inc. It was the right place for her.

There had been few women animators in New York in past decades but, among the men, the held opinion was that women couldn’t do the job. There was also a general attitude that the craft was dominated by Americans. To them animation was a trade for which females and foreigners need not apply. UPA, however, was a progressive studio where the staff included various minorities and nationalities. As one talented African-American artist remarked, “When you walk in here you feel comfortable and welcomed.”

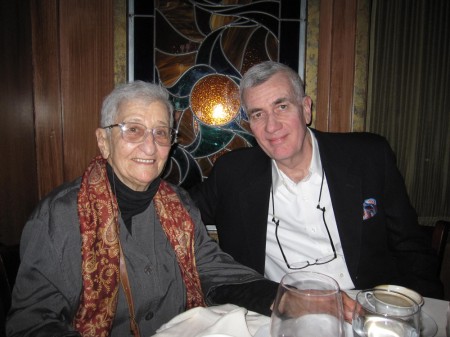

Tissa was greeted by animator Grim Natwick. His European art studies long behind him, he was the choice crew member to interview the then English challenged Tissa. Natwick was direct, ___________Tissa and Grim at Christmas

“What do you think of animation?”

Tissa hesitated , then replied, “Animation is animation.” That satisfied Natwick. Tissa was given a try out on a character from the studio’s popular Piel’s Beer commercials and then hired. The brief meeting with Grim was expressly important because the film that inspired her to get into animation was Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs for which Natwick had animated 80% of the lead character. Tissa became Grim’s assistant beginning an association that lasted 35 years.

In time, Tissa became an animator in her own right at local studios giving life to TV commercials. Later came requests from producers with a broader range of diverse characters. These included John and Faith Hubley, R.O. Blechman and Michael Sporn all who came to depend on her animation skills and unique intellectual qualities. Tissa entered a legacy laid down by earlier European animators, illustrators and designers whose influence profoundly effected American cartoons. Working at Disney and Fleischer Studios, their affinity to old world castles, cottages and colorful personalities added credibility, charm and warmth to animated features.

Tissa also played an outstanding role in the ASIFA-East chapter. She organized and corralled the membership lists and dues collections. This was at a time when new graphics guilds were entering the field with lists of 2000 or more, but Tissa proudly managed our 250 or so enthusiatic members.

She was a prime promoter and facilitator of the ASIFA-East Film Festival, and tabulated the voting results as well as commanding the arranging of the event’s refreshment tables. Under her discriminating gaze many of us schlepped wine bottles and tubs of cheese.

I worked with Tissa at various studios around the city and remember a gratifying moment one rainy day when she and Grim came to one of my classes. They had gotten lost in SVA’s internal maze, arriving late and dripping wet. Though tardy, they added substance to the class by answering questions and giving weight to the realities of the field. To the familiar student concern about whether the character of Snow White was traced over live-action actors, Grim, chalk in hand, sketched Snow White to clearly illustrate why her cartooned proportions didn’t allow for rotoscoping.

There’s one anecdote regarding Tissa that I’ve repeated many times, but it still warms my heart, so pardon me if you’ve heard this before. I feel it’s worth repeating since it indicates Tissa’s warmth, humor and life-energizing spirit that rose above everyday twists and turns.

Tissa often traveled to Europe to see family and to animate for small studios. She also had a country house in Southern France. In the spring of 1974, while working in Holland, she contacted Iris and I about attending the animation festival in Zagreb. Her suggestion was that we meet her in Paris a week before the event. She kept a small Volks station wagon there and proposed that we drive across Europe to Zagreb. We accepted gladly. It would be a wonderful journey with a great guide. After a night in Paris we drove south through agrarian countryside evoking the colors of Van Gogh and other post impressionist painters. We stopped in a small town so Tissa could check out her French country place and then we found a small, inexpensive hotel for the night. Tissa suggested that Iris and I take a back room and she a front room. Our lodging was simple, but when we opened the shutters to let in the good night air, we saw the shining moon behind silhouetted castle towers. We slept soundly.

The next morning at breakfast we wondered if she had slept well. “Oh it was terrible!” she replied, “Big trucks rattling past my window all night!” We traveled on through southern France and into northern Italy. One late afternoon we arrived at a local hotel and prepared for a night’s rest before entering Venice. We agreed that this time Tissa would take a back room and we a front room. We slept soundly.

In the morning came our question,” How did you sleep?” It was terrible!” she replied, “There were people playing guitars and singing all night in the courtyard!”

Tissa David will be remembered as a person of taste, humor, artistic skills and a wide understanding of people and the world in general. She observed and interpreted things in a private way. She appreciated much but was opinionated and disdainful of things that didn’t meet her standards. Tissa was a dedicated animator on all manner of productions from workaday TV announcements to celebrated award winners. Though a very private person, she was a friend and mentor to many. She was a treasure in our midst. For all of us who knew and admired her, she will be missed.

Howard’s talk was followed by a clip from Raggedy Ann and Andy

her Candy Hearts and Paper Flowers sequence.

R.O. Blechman was the next speaker. His short talk was planned but spoken off the cuff, improvised. There’s no transcript of it.

R.O. Blechman was the next speaker. His short talk was planned but spoken off the cuff, improvised. There’s no transcript of it.

He started by quoting a poem Tissa liked by T.S.Elliott in which Tissa had substituted the word “animator” for “poet”. Bob also told the story of an article about his show Simple Gifts in which he called the 5 designers, “Artists.” Bob was surprised that Tissa had confronted him by telling him that she was an “Artist” yet there was no mention of her in the promotional article.

Bob’s talk was followed by clips from his studio:

3 commercials for:

– Perrier

– Banco

– WQXR radio

a clip from a promotional trailer for Candide, a film Bob sought to make as a feature.

a clip from The Soldier’s Tale, Blechman’s Emmy winning adaptation of Stravinsky’s work.

Candy Kugel was the next speaker.

Tissa was my role model—a pathfinder. When I entered the animation industry in the 1970’s there were no other female animators beside her and I was experiencing the same sexist attitudes as she did. And I was in awe of her ability—her fluid line and acting. And finally, I was always grateful for her introduction__________(LtoR) Blechman, Tissa, Vince Cafarelli, Candy Kugel

Tissa was my role model—a pathfinder. When I entered the animation industry in the 1970’s there were no other female animators beside her and I was experiencing the same sexist attitudes as she did. And I was in awe of her ability—her fluid line and acting. And finally, I was always grateful for her introduction__________(LtoR) Blechman, Tissa, Vince Cafarelli, Candy Kugelto international animation and ASIFA.

The first time I was introduced to Tissa was on the telephone in the summer of 1972. I was about to go to Italy for my last year of art school after spending summers interning at Perpetual Motion Pictures.

My boss, the designer Hal Silvermintz, told me that Tissa knew everyone in Europe and she could give me the names of studios so that I could visit them while there. She did, and I did – in Rome, Zagreb and Budapest. And then, since Annecy would have its festival that June, she encouraged me to go and gave me the address to write for certification.

I did go to Annecy and it opened my eyes to international animation in a way I could never have imagined before. There was no internet then, no DVDs and no video collections—the only way you could see these movies was projected in a theater. And I do remember briefly meeting Grim Natwick (who drew me a Betty Boop) and Tissa.

When I returned to New York, it was a bad time for animation so I went to Los Angeles to try my luck there. In New York I had had the good fortune to be treated well by my bosses—my main responsibility was to help the designer.

I had some rudimentary animation experience, but the real animation was done by experienced animators, and they came from a culture of secrecy.

In LA I went to Disney with my “reel†and portfolio and found a whole other set of obstacles. The front gate passes had “Mr.†printed on the guest line. This was during the feminist movement and I jokingly said to the woman behind the window—“I guess you don’t see very many women hereâ€â€”she scratched off the Mr and roughly handed it back to me. I met with 3 men, including Don Duckwall. They told me I drew nicely but that women just don’t have what it takes to be an animator. Women lack timing. Maybe I should consider becoming a designer or background artist.

“But I want my drawings to ACT!†I protested. They smiled and shook their heads.

In the end, I returned to work fulltime at Perpetual. I was determined to learn how to animate well. I got to know Tissa through ASIFA and she offered to help me.