Search ResultsFor "alice in wonderland"

Books &Commentary &Disney 27 Oct 2011 06:18 am

Walt in Wonderland – overdue review

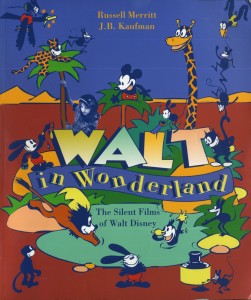

- The book I reread this week was Russell Merritt and J.B.Kaufman‘s Walt in Wonderland. Actually, this was the third time I’d read the book, and I’ve also visited it another half dozen times just for the illustrations. Needless to say, I think this book is a treasure.

- The book I reread this week was Russell Merritt and J.B.Kaufman‘s Walt in Wonderland. Actually, this was the third time I’d read the book, and I’ve also visited it another half dozen times just for the illustrations. Needless to say, I think this book is a treasure.

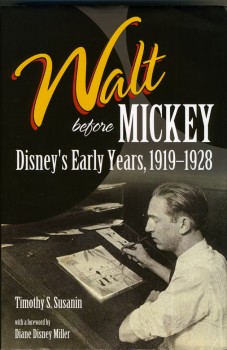

In the past three weeks, I’ve read three versions of the same material in different forms. Timothy S. Susanin’s Walt Before Mickey: Disney’s Early Years, 1919-1928 led me to reread Donald Crafton ‘s Before Mickey and that led me to reread today’s book. They all come with different pleasures. Though the material was the same, in no way did I feel as though it was repetitious. All three writers have different approaches, and all three kept it lively for me.

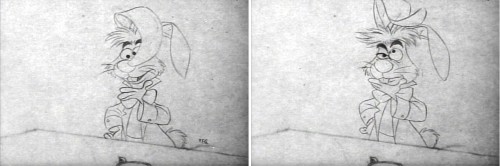

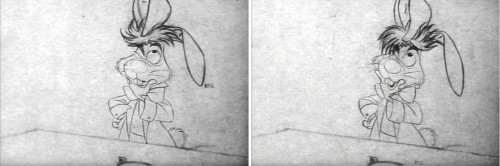

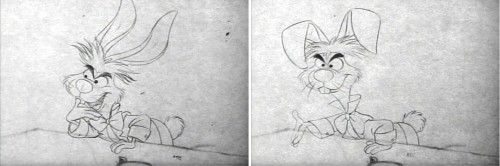

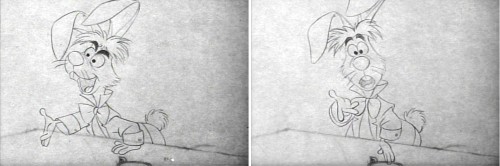

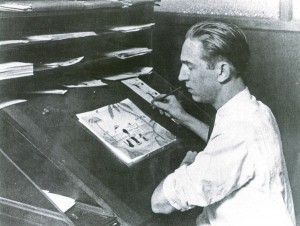

Crafton’s Before Mickey tells the story most expeditiously. There’s a lot in this book, and the Walt Disney story is just a part of it. Susanin’s Walt Before Mickey reveals a very large gathering of data, much of which is really unnecessary to the story, but just the same was a delight to me. Merritt & Kaufman’s Walt in Wonderland expands on Crafton and holds back on extraneous material. However the book is overrun with enormously valuable visuals. Scripts, story pages, animation drawings, posters and pictures fill the space around the story of Walt Disney’s rise from nowhere through the creation of Mickey Mouse.

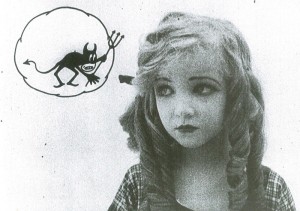

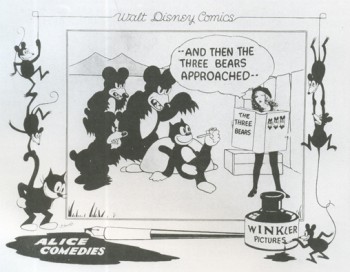

The authors take the time to reveal some of their methods of evaluating the material. For example, not all of the silent films exist today, so they create a complete filmography from archival texts they found. Copyright forms required synopses of the stories as well as credits for the films. This enables the authors to detail the material for us when they weren’t able to actually see the films. Prior to this book, we knew that Virginia Davis, Dawn O’Day and Margie Gay all played Alice in the Alice Comedies. However, Kaufman and Merritt were also able to identify a fourth Alice as Lois Hardwick, and they also calculate why the change. This is scholarship, well done.

The authors take the time to reveal some of their methods of evaluating the material. For example, not all of the silent films exist today, so they create a complete filmography from archival texts they found. Copyright forms required synopses of the stories as well as credits for the films. This enables the authors to detail the material for us when they weren’t able to actually see the films. Prior to this book, we knew that Virginia Davis, Dawn O’Day and Margie Gay all played Alice in the Alice Comedies. However, Kaufman and Merritt were also able to identify a fourth Alice as Lois Hardwick, and they also calculate why the change. This is scholarship, well done.

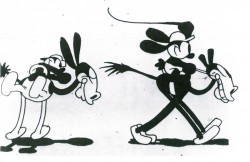

Though I’ve read this book several times already, I still call this series “Alice in Cartoonland.” In fact, many people do, yet the authors point out that it was never the title of the films. They were simply called the “Alice Comedies.”

I was not much of a fan of this animation series; actually, I was not a big fan of the Disney silent films. They pale in comparison to the Felix cartoons of the same period – in fact, almost everything does (of course with the exception of the McCay films.) The Disney silent films have a lot of energy, but a farmyard sense of humor that never seemed very funny to me.

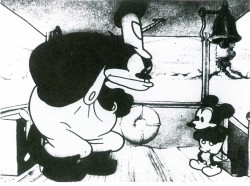

I’ve sat through numerous theatrical screenings of silent shorts (and fallen asleep in many of them). One, however, stands out memorably. There was a MoMA show which was a compilation of shorts from different studios. An organ soundtrack was attached to many of the shorts, but several were truly silent. (It’s interesting to attend an audience who doesn’t know if talking is allowed when the film is dead silent.) The program soon grew tiresome and dragged on. The last film screened was Disney’s “Steamboat Willie,” the first successful animated short with synchronized sound. Let me tell you, it was made perfectly clear how monumental this film was, and why it was so successful. That sound track was a godsend after 90 minutes of silent dross.

I’ve sat through numerous theatrical screenings of silent shorts (and fallen asleep in many of them). One, however, stands out memorably. There was a MoMA show which was a compilation of shorts from different studios. An organ soundtrack was attached to many of the shorts, but several were truly silent. (It’s interesting to attend an audience who doesn’t know if talking is allowed when the film is dead silent.) The program soon grew tiresome and dragged on. The last film screened was Disney’s “Steamboat Willie,” the first successful animated short with synchronized sound. Let me tell you, it was made perfectly clear how monumental this film was, and why it was so successful. That sound track was a godsend after 90 minutes of silent dross.

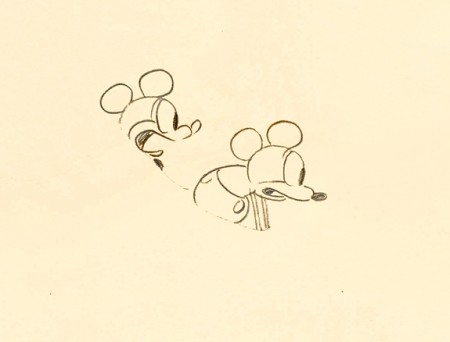

There is one telling sentence at the beginning of this book. “. . . the first striking fact about Disney’s 1920s films is that they take no particular direction: they don’t evolve, they accumulate.” The authors point out that knowing the films of the 30s Disney, one would expect that the work in the 20s would, likewise, be a developing road-map to the future; constant growth in the animation and production techniques. Yet, it isn’t until Mickey that we start seeing enormous growth. “Plane Crazy,” the first Mickey (still a silent film), is when we get the first truck in (Iwerks came up with this effect, created by placing books under the zooming background as it got closer to the lens of the stationary camera.) Perhaps it took the trauma of creating that first Mickey Mouse cartoon for Disney and crew to wake up to innovation. And perhaps realizing how powerful that innovation was to the animated film – the success of the first sound film, then the first color film – that Disney realized the importance of constant change and growth.

There is one telling sentence at the beginning of this book. “. . . the first striking fact about Disney’s 1920s films is that they take no particular direction: they don’t evolve, they accumulate.” The authors point out that knowing the films of the 30s Disney, one would expect that the work in the 20s would, likewise, be a developing road-map to the future; constant growth in the animation and production techniques. Yet, it isn’t until Mickey that we start seeing enormous growth. “Plane Crazy,” the first Mickey (still a silent film), is when we get the first truck in (Iwerks came up with this effect, created by placing books under the zooming background as it got closer to the lens of the stationary camera.) Perhaps it took the trauma of creating that first Mickey Mouse cartoon for Disney and crew to wake up to innovation. And perhaps realizing how powerful that innovation was to the animated film – the success of the first sound film, then the first color film – that Disney realized the importance of constant change and growth.

Whatever the reason, things changed with the coming of sound.

Walt in Wonderland is a key book that synthesizes this entire period in the evolution of Disney animation. It’s a little-known beginning, and the book not only details the making of all the films but gives a clear and good summary of the series that were done. You see the long shot as well as the close up, and you have no doubt as to the true history of the material.

Walt in Wonderland is a key book that synthesizes this entire period in the evolution of Disney animation. It’s a little-known beginning, and the book not only details the making of all the films but gives a clear and good summary of the series that were done. You see the long shot as well as the close up, and you have no doubt as to the true history of the material.

The authors obviously did enormous research, yet the look of the book, filled with new and different visuals, is anything but scholarly. As a matter of fact, there are times when the images almost create a distraction from the writing. A tough problem for an animation book to have.

All I can say is that if you have any interest in the early Disney, the young and vibrant Disney, I’d suggest you get a copy of this book. It’s a gem.

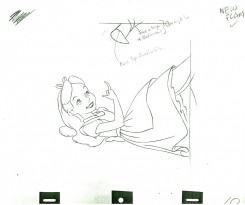

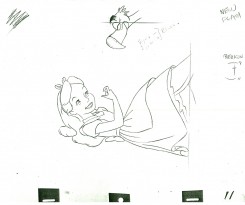

Here’s a drawing I have from Plane Crazy.

Click the image to see the whole drawing.

Commentary 04 Oct 2011 06:39 am

Hubley/Blair

- Two shows are about to take place; one in New York (Monday October 10th An Academy Salute to John Hubley), another in Los Angeles (Thursday October 20th, Mary Blair’s World of Color; A Centennial Tribute). I wish I could attend bothh of them; I’m happy to be in NY to attend the John Hubley program (and be a small part of it.)

Interesting that these two shows appear in the same month at two different AMPAS stations. Yet, the two artists couldn’t be more diametrically opposed in their work. One was more of an illustrator, albeit a brilliant illustrator, and the other was more a fine artist.

.

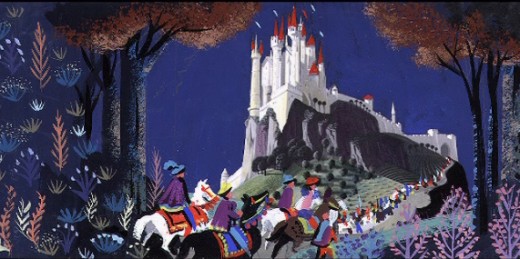

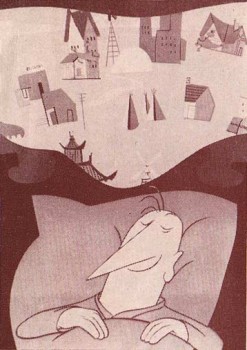

Everything about Blair’s work, from The Little Golden Books to the designs for the Disney features of the early 50′s to the overall design for It’s a Small World in Disneyland, are all glorious testaments to a first rate, gifted illustrator of the highest caliber. She radically changed her style on the trip to South America with the Disney group, and she brought these brilliant color mixes back with her to the work she did at Disney. The colors were almost there for the sake of the colors, alone. The work developed and grew more sophisticated with all that she did, and her color schemes became more radical as she designed for the Disney features.

.

.

The grand statement of the art . . . well, there was no grand statement. It was done to further the films or the projects, and had no message. It was beautiful production art, but it was not really “Art.”

.

.

Hubley’s work sought to create art, and the style and growth continued upward through his years. The work at Disney’s studio started as gifted illustration (Snow White), then turned to a looser feel with oils (Pinocchio) and watercolor (Bambi). As he moved to UPA, the art followed Steinberg and Picasso closer to the world of abstraction. Ultimately, with Adventures of an * and films that followed (done by and for himself and his wife Faith) the Abstract Expressionists ruled, and Hubley’s art went far into that direction and stayed there through most of his films.

Hubley’s work sought to create art, and the style and growth continued upward through his years. The work at Disney’s studio started as gifted illustration (Snow White), then turned to a looser feel with oils (Pinocchio) and watercolor (Bambi). As he moved to UPA, the art followed Steinberg and Picasso closer to the world of abstraction. Ultimately, with Adventures of an * and films that followed (done by and for himself and his wife Faith) the Abstract Expressionists ruled, and Hubley’s art went far into that direction and stayed there through most of his films..

Tender Game, which followed Adventures of, was a variation that seemed to emulate some of the work of Baziotes. Moonbird was where Hubley came into his own and created a very rich style that was all his own. Variations on it came with The Hat, The Hole and Of Stars and Men. A new direction came with Windy Day. By the time we reached Cockaboody, a softness settled into that very same style and watercolor backgrounds dominated. There was throughout all this work a beautiful development where one phase grew out of another which had grown out of another.

.

And there was a grand statement: all art, abstract or realistic was an abstraction and it touched all of our lives regardless of our thoughts about it. Picasso could be dismissed by those not in the know, but eventually the masses would warm up to him and eventually take it for granted that this, too, was Art. Hubley helped make that world – this world – so. Acceptance and understanding was part of his oeuvre.

.

One wonders if Hubley had remained at Disney’s as long as Blair had whether any of his rich design style would have controlled the films as her work had. Of course, the answer is obvious. He never would have been able to remain at Disney’s studio. His penchant for the further development of the art – out of the 19th century illustration – would not have allowed him to sit still there. By leaving, he not only pushed his own work into a higher realm, but he pulled animation there with him.

.

.

In a sense, without his work, animation would still be stuck in the 19th Century graphics and would not have moved into the 21st Century. We can see evidence of this with all the cgi features being done today. Those little fabricated computerized puppets are wholly stuck in 19th Century art, yet 2D has moved on. We accept “Beavis & Butthead” or “Aqua Teen Hunger Force” (both badly drawn works that are most definitely 21st century graphics) because Hubley changed things. Not that John Hubley was the only one who wanted to do more, graphically, in animation, but others seem content with modernized cartooning. Chuck Jones, for example, who led the way in 1941 settled into a stylized cartooning in the 1950s. Hubley sought art – something different and deeper than was acceptable to others.

Picasso led to acceptance of Andy Warhol and Robert Rauschenberg; Hubley led to acceptance of “South Park” and Yurij Norshtein.

.

Pictures:

1. Mary Blair – personal painting

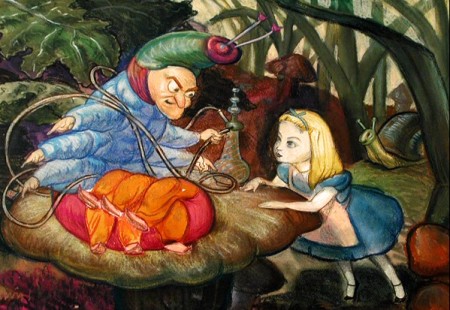

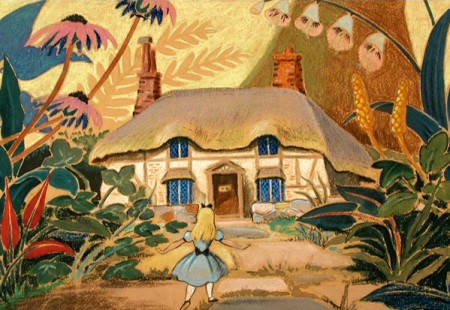

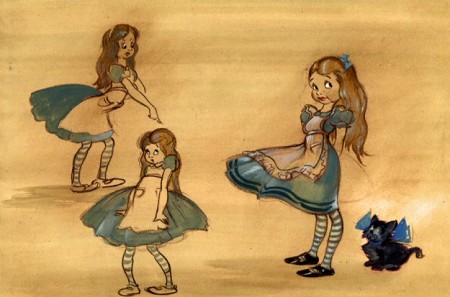

2. Mary Blair – Alice In Wonderland

3. John Hubley – Bambi

4. John Hubley – Brotherhood of Man

5. John Hubley – Everbody Rides the Carousel

6. John Hubley – Moonbird

Books &Disney 09 Aug 2011 06:44 am

Walt Before Mickey – a book report

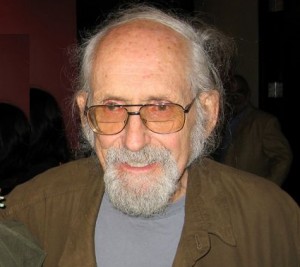

- Before I write about the book, let me say that I am truly sad to hear of the death of Corny Cole, one of those great people you meet in the world of animation who seriously changes things for you. I thank Richard Williams for introducing me to him. I’ll try to post a number of his drawings later this week.

- I’ve spent a lot of time in the past two weeks reading a thoroughly enjoyable and inspiring animation book, and I wholeheartedly recommend it to anyone interested in Walt Disney or animation. Walt Before Mickey: Disney’s Early Years 1919-1928 is by Timothy Susanin, and it’s such a real treat that I had a hard time putting down. Yet I wanted to keep it alive, so I brought a bunch of other books in for the ride. I took my time reading it even though taking my time was hard to do.

- I’ve spent a lot of time in the past two weeks reading a thoroughly enjoyable and inspiring animation book, and I wholeheartedly recommend it to anyone interested in Walt Disney or animation. Walt Before Mickey: Disney’s Early Years 1919-1928 is by Timothy Susanin, and it’s such a real treat that I had a hard time putting down. Yet I wanted to keep it alive, so I brought a bunch of other books in for the ride. I took my time reading it even though taking my time was hard to do.

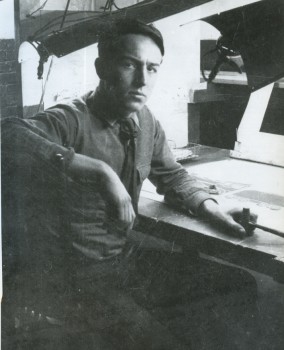

The book tells in elaborate detail (and I do mean elaborate) all of the steps that Disney had taken to get started in this business. The boy who learned how animation could become much more than it was and fought with all the “jack” he had to put it all on the screen. He and Roy, partners in those early days, staked everything on their belief in what they were doing. It’s a great story and makes for something of a page turner.

In J.B. Kaufman and Russell Merritt‘s book, they open with an evaluation of the early period of Disney animation: ” . . . the first striking fact about Disney’s 1920′s films is that they take no particular direction: they don’t evolve, they accumulate.” How accurate an assessment of these films. They don’t get better, they get worse almost as though Disney soon tired of doing them. The gags become repetitive; the characters lose all sense of characterization; even the live-action “Alice” goes from having a large part in the films to flailing her arms so that we can cut back to the drawn animation. This is not the Disney we know from the Thirties & Forties – the one who pushed his people to create the Art form. Essentially, Kaufman and Merritt are looking for the “Art” and give a sharp report on their findings.

This isn’t true of Susanin. His book searches only for the facts and records. But then, let’s look at how the two books were constructed. Susanin’s interviews were limited in comparison to someone like Mike Barrier who did several hundred interviews to write Hollywood Cartoons. He helped Mr. Susanin with many an interview; he also got some help from Kaufman and numerous others in gathering the details and data for the book. Mr. Susanin said, “. . .the Library of Congress, the New York Public Library, MOMA, and the like. I visited the studio when work took me to Burbank, and the Walt Disney Family Museum construction site when work took me to San Francisco. Otherwise, it was lots of virtual work and lots of phone calls with librarians around the country! ”

A lot of the source information came from authors who’d done their own books. Susanin gathered the material – and gathered A LOT OF MATERIAL.

A lot of the source information came from authors who’d done their own books. Susanin gathered the material – and gathered A LOT OF MATERIAL.

The accumulation of the facts is collected in an almost overwhelming fashion by Susanin. Every sentence in the book seems to have some source information backing it up. An almost minute-to-minute account of these early days is gathered and written about. Prior to this book, I found myself guessing at some of the material. I hadn’t really seen all the details until I had them laid out in this book. Add to that details upon details, and you’re breathless from the material presented. (Every person Disney meets seems to have their history displayed. And just read about the Laugh-O-Grams bankruptcy suit in the epilogue.)

Make no mistake about it, this is a period I am wholly and completely intrigued with. I’ve read every book and interview about it that I could find. Kaufman & Merritt’s Walt In Wonderland, Mike Barrier’s The Animated Man, Donald Crafton’s Before Mickey, even Canemaker’s Winsor McCay. I’ve read and read and read again through the material. Yet the way it’s ultimately presnted in this book is so involving. Perhaps it’s all those details I love reading.

In the three week period Walt and Lillian spent in New York looking to sign a second contract to produce the Oswald animation for Universal, you see all the meetings he has taken. All the visits to Universal and Charlie Mintz (who actually contracts the job to Disney and ultimately steals a large part of his staff so that he can dump Disney) and to MGM (Fred Quimby – of all people) and Fox. He spends a lot of time with Jack Alicote the editor of Film Daily who counsels Walt on the business side of the business. You see all the connections; you understand the seriousness of Walt’s situation and you ride with him trying to grasp what straws he has left. It’s hypnotic in all its detail, and it serves as a tight climax in a well written book.

In the three week period Walt and Lillian spent in New York looking to sign a second contract to produce the Oswald animation for Universal, you see all the meetings he has taken. All the visits to Universal and Charlie Mintz (who actually contracts the job to Disney and ultimately steals a large part of his staff so that he can dump Disney) and to MGM (Fred Quimby – of all people) and Fox. He spends a lot of time with Jack Alicote the editor of Film Daily who counsels Walt on the business side of the business. You see all the connections; you understand the seriousness of Walt’s situation and you ride with him trying to grasp what straws he has left. It’s hypnotic in all its detail, and it serves as a tight climax in a well written book.

This segment takes Mr. Susanin 12 pages, full of details, yet it took Mr. Barrier fewer than 2 pages in The Animated Man and fewer in Hollywood Cartoons. It took Kaufman & Merritt in Walt In Wonderland just a bit more than 2 pages to get the information across. It’s not that I needed that additional information to grasp the dire situation Disney was in, it’s that I wanted it. Yet any strong quote in Barrier’s books or Kaufman & Merritt’s has ended up in Susanin’s. It seems that ANY detail that could be found was used to tell the story.

For a geek like me who can’t get enough of this, it’s great. But I wonder about the average reader.

My only real problem with the book is that I wanted the story to go on. At least through Steamboat Willie. Susanin gives a quick sketch of the rest of Disney’s career, but I wanted to get more about that two month period when Plane Crazy was in production. After all, the staff that would leave him – Hugh Harman, Max Maxwell, Mike Marcus, Ham Hamilton and Ray Abrams – stayed on to finish the Oswald pictures while Ubbe Iwerks worked with Les Clark and Johnny Cannon to draw the first Mickey film. A real disappointment set in for me when I came to that epilogue as Disney boarded the train home to start over again.

Yet even in that epilogue there are those delicious details. All of the books personae are laid out with short bios of where they went and when they died. Everyone from Hazel Sewell to Johnny Cannon to Les Clark to Rudy Ising. What a sense of detail. I can tell you I’ll use this book for information for a long time, and there’s not doubt I’ll read it a few more times. This is a wonderful book, and I encourage you to pick it up.

There are some fine interviews with Mr. Susanin on several sites:

- Didier Ghez talks with him on his Disney History site.

- On Imaginerding there’s a nice informal interview.

- Moving Image Archive News also has a review mixed with interview.

Commentary &Disney 18 Jun 2011 07:34 am

Sight Seeing

- This past week Jonna commented on this blog: I can only imagine how it would have been to see one of the classics at a theater (I was born in the 90’s). It would have been great fun if any of you told about a premiere or screening that you’ve attended (e.g. the first time you saw Sleeping Beauty or something).

So I thought of a couple of memories I have of seeing some of the classic Disney films theatrically for the first time. So kiddies gather round Gran’pa while he tells you a story.

The first film I’d ever seen was Bambi. I don’t remember much about it, but I’m sure that the experience permeated my brain and sent me on a direction I could never return from. This is still one of my favorite classic Disney films. I’m not big on the cutesy aspects of the movie – specifically the “twitterpated” sequence, but I am big on everything else. Back in those days, there were often Surprise guests coming to the movie theaters to promote the shows. At this one particular event, to celebrate Christmas they drew back the curtain and had a pile of large gifts all wrapped in foil-colored gift wrap. Clarabelle the clown from the Howdy Doody Show was a special guest who was going to give out gifts to the boys and girls in the audience. He went through a short routine which ended with the supposed gift-hand-out. But it didn’t happen that way. Clarabelle took out his bottle of seltzer and started spraying the audience. The blustered theater manager called for the curtain to be closed, and that was that. Even at the age of 4 or 5, I knew we was robbed. No wonder I couldn’t remember much about Bambi.

The first film I’d ever seen was Bambi. I don’t remember much about it, but I’m sure that the experience permeated my brain and sent me on a direction I could never return from. This is still one of my favorite classic Disney films. I’m not big on the cutesy aspects of the movie – specifically the “twitterpated” sequence, but I am big on everything else. Back in those days, there were often Surprise guests coming to the movie theaters to promote the shows. At this one particular event, to celebrate Christmas they drew back the curtain and had a pile of large gifts all wrapped in foil-colored gift wrap. Clarabelle the clown from the Howdy Doody Show was a special guest who was going to give out gifts to the boys and girls in the audience. He went through a short routine which ended with the supposed gift-hand-out. But it didn’t happen that way. Clarabelle took out his bottle of seltzer and started spraying the audience. The blustered theater manager called for the curtain to be closed, and that was that. Even at the age of 4 or 5, I knew we was robbed. No wonder I couldn’t remember much about Bambi.

The second film I’d ever seen was Peter Pan. That would have been for the 1953 theatrical release. My father took me to one of those large movie palaces in upper Manhattan, the Loew’s 181st Street. I remember it playing with a film about a jungle cat of some kind; I’ve always remembered this as The Black Cat, but that title isn’t right. So I obviously don’t remember the title of the film, a B&W scary movie.

The second film I’d ever seen was Peter Pan. That would have been for the 1953 theatrical release. My father took me to one of those large movie palaces in upper Manhattan, the Loew’s 181st Street. I remember it playing with a film about a jungle cat of some kind; I’ve always remembered this as The Black Cat, but that title isn’t right. So I obviously don’t remember the title of the film, a B&W scary movie.

Re the animated feature, I remember most the swirls of color of Pan and gang flying; I don’t remember much else about it from that initial introduction. I was absolutely enamored with the moviegoing experience from The Black Cat to the brilliant cartoon. Remember, I was only 6 or 7 years old, at the time.

In 1955, I was in charge of about five kids (a couple of siblings and a couple of cousins) going to a local theater to see the NY premiere of Lady and the Tramp. Back then, it would cost 25 cents for a kid to get into the movies. When we’d gotten to the local movie theater for this film, they’d raised the price to 35 cents – more than our parents had allotted.

Outside the theater we were counting up our monies and trying to figure out how much we’d need to get in and buy some candy or popcorn for all of us. Within seconds my cousin announced that she’d lost her money, and it was obvious there wasn’t going to be enough for refreshments. The cousin started crying loudly, bawling until the movie theater manager came up to ask what was the problem. She spluttered out the word that she couldn’t afford any candy now that she’d lost the money to get into the movie. The manager just reached into his pocket and gave me an additional dollar. Enough money for movie and candy and more importantly it stopped my cousin’s screaming.

Outside the theater we were counting up our monies and trying to figure out how much we’d need to get in and buy some candy or popcorn for all of us. Within seconds my cousin announced that she’d lost her money, and it was obvious there wasn’t going to be enough for refreshments. The cousin started crying loudly, bawling until the movie theater manager came up to ask what was the problem. She spluttered out the word that she couldn’t afford any candy now that she’d lost the money to get into the movie. The manager just reached into his pocket and gave me an additional dollar. Enough money for movie and candy and more importantly it stopped my cousin’s screaming.

Once inside the theater I ignored them – even though the cousins were badly behaved and squirmed about through most of the show. I liked the film so much that I made the whole group sit with me to watch it a second time. That big, wide Cinemascope screen. It was heaven.

We did this often back then. I remember another time going to see Pinocchio with my younger sister, Christine. We sat through Pinocchio three times before we left the movie theater. That meant we had to sit through the second feature (usually some live action dud) twice to get to the third showing of the cartoon. My sister reminds me often enough that when she turned around she’d seen that the theater was empty except for the two of us. The usher stood in the back giving us the evil eye.

Prior to Sleeping Beauty‘s release, I’d been doing some reading. I’d received Bob Thomas’ The Art of Animation the previous Christmas, and I read it over and over at least a hundred times. I memorized every still in that book and couldn’t wait to get my eyes on Sleeping Beauty.

The film opened at Radio City Music Hall, and I was given permission to make one of my first trips downtown to see the film. An hour subway ride for a 12 year old. I went into this largest of movie theaters in the City, and I picked a great seat. The audience wasn’t overflowing; the show wasn’t sold out. But it was BIG.

The screen is enormous in that theater, and Sleeping Beauty was made to fill such a screen, especially in its Technirama debut. But somehow I came out of the theater disappointed. I don’t know what had gotten into me. I don’t remember any reason for disliking it. As a matter of fact, I absolutely love the film now. Those Eyvind Earle settings; the great animation of Maleficent; the dragon fight. There’s just a million reasons I have for loving it, but something about that first viewing left me cold. And I remember trying to analyze, at the time, what I thought was missing from the experience. I had no answer.

I’ve seen all of the pre-cgi Disney films in theaters. I also remember all the experiences of sitting through them. Dumbo and Alice In Wonderland were the only two that I saw on TV first. They were both special presentations on the Disneyland show. Eventually, I’d see them both in theaters at special screenings.

Of all of them, Dumbo still stands as my favorite though in a close tie to Snow White. There’s something they both have that goes beyond the brilliant animation and the graphics on screen. There’s an emotion there that they both have, not quite an innocence but more like a daring. Without consciously saying it, you felt the Disney people were shouting, “Look what we can do!” And they did do it. (By the time they did Fantasia, they were too conscious of what they could and had done, and they’d lost it – for me.)

Eddie Fitzgerald is either a genius or a real-life looney toon – who I treasure. Probably, I think both; he’s at least an original. His blog is like no other in that he gives us real deep rooted comedy that makes you laugh aloud. He puts together these photo-montage storyboards creating a wacky movie that you just gotta keep reading, and when he’s on the mark, there’s nothing short of brilliance.

Eddie Fitzgerald is either a genius or a real-life looney toon – who I treasure. Probably, I think both; he’s at least an original. His blog is like no other in that he gives us real deep rooted comedy that makes you laugh aloud. He puts together these photo-montage storyboards creating a wacky movie that you just gotta keep reading, and when he’s on the mark, there’s nothing short of brilliance.

Bob Clampett did a wacky WB short called The Lone Stranger and Porky. Obviously, it was a parody of the big radio show of the time, The Lone Ranger. Well, Eddie takes off on that parody and does Clampett one better. It’s crazy and hilarious and you have to check it out (if you haven’t already.) The Lone Stranger (Parody) via photomontage.

Someone should finance this guy to make a real movie. This artwork would take cgi in a direction that hasn’t been considered before. Maybe then they’d have the first REAL animated cgi film instead of all these cutesy viewmaster things we get.

Last week I started a new series that I hope will go on forever. I’ve been interviewing Independent animators, the ones who are trying to make artful animation on their own. They don’t have the dollars that a Dreamworks would, but they’re using all of their resources to make movies that have something to say.

Last week I started a new series that I hope will go on forever. I’ve been interviewing Independent animators, the ones who are trying to make artful animation on their own. They don’t have the dollars that a Dreamworks would, but they’re using all of their resources to make movies that have something to say.

The first post was an interview with George Griffin, who has been something of an inspiration to me. Upcoming this Tuesday will be an in depth look at the amazing career of Kathy Rose. She takes animation, mixes it with dance and Performance Art and comes out with amazingly original work. I’m having a good time putting these pieces together, and there are so many who deserve the attention.

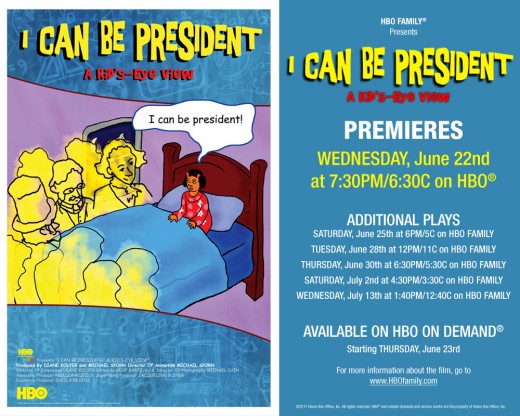

- I have one last bit of self-aggrandizement to post. THis coming Wednesday, June 22nd, HBO will premiere the latest Special we’ve done for them. (Notice how I date myself by calling it a “Special”. That’s what they were called when I was younger. These days I only know the industry word for them, “one offs”. I don’t like to think of my show as a “one off”; it’s a Special.)

The show is about half animated; the other half consists of kids saying the wackiest things. It’s fun. So there you go.

Books &SpornFilms 30 Apr 2011 07:49 am

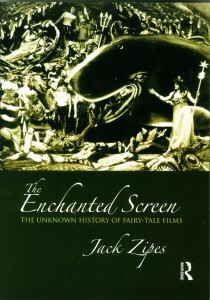

Zipes’ The Enchanted Screen

- Author, Jack Zipes, has just released a new book called, The Enchanted Screen. Mr. Zipes is a professor of German and Comparative Literature at the University of Minnesota. He is a scholar whose focus has been children’s literature and culture, and he has written at least seven other books. I’ve been aware of his work since his book, Hans Christian Andersen, the Misunderstood Storyteller. It was in that book that Mr. Zipes gave some attention to the films we’ve done in our studio. Although he felt that Andersen was often misused or misunderstood when translated to other media, he wrote that our films offered excellent adaptations. Of course, I’d be interested in anything Jack Zipes had to write in the future.

- Author, Jack Zipes, has just released a new book called, The Enchanted Screen. Mr. Zipes is a professor of German and Comparative Literature at the University of Minnesota. He is a scholar whose focus has been children’s literature and culture, and he has written at least seven other books. I’ve been aware of his work since his book, Hans Christian Andersen, the Misunderstood Storyteller. It was in that book that Mr. Zipes gave some attention to the films we’ve done in our studio. Although he felt that Andersen was often misused or misunderstood when translated to other media, he wrote that our films offered excellent adaptations. Of course, I’d be interested in anything Jack Zipes had to write in the future.

This new book, The Enchanted Screen, goes deeper than just Andersen’s tales, taking in all world literature. However, there can be no doubt that Andersen is a primary interest of Mr. Zipes’ studies. There are elaborate analyses of the various productions of The Snow Queen or The Little Mermaid or The Emperor’s New Clothes. Disney is certainly taken to task for sentimentalizing children’s literature. Indeed, there’s a complete chapter entitled, “De-Disneyfying Disney: Notes on the Development of the Fairy-Tale Film.” To be honest, it’s hard to argue with his premise, if you take Grimm and Andersen seriously. When he points out that J.M.Barrie’s Peter Pan becomes Walt Disney’s Peter Pan or Lewis Carroll’s Alice In Wonderland becomes Walt Disney’s Alice, you begin to realize the change in ownership which also recognizes a change in the values imparted in those original tales. (Shrek actually fares well under this scrutiny since it spoofs the Disneyfication of the tales.)

In short, the book is an excellent read if you’re interested in the subject – as I am. It’s especially pleasing when the author has nice things to say about your work, but that is hardly the reason I enjoyed the book. I appreciated the honest and intellectual discussion of the material, and I enjoyed some of the sources he considered at length. Since I make films using this material, I am curious to hear what critics have to say.

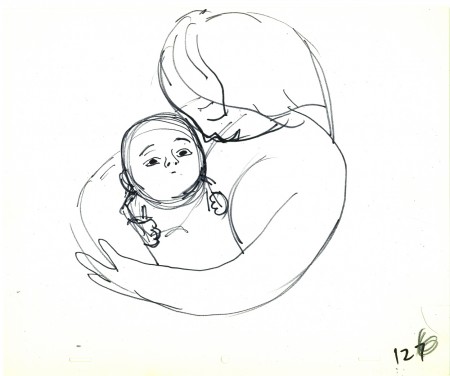

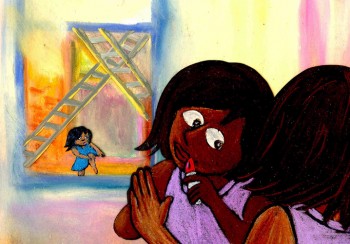

As an addendum to these comments, I thought I’d post a page from the book that talks about a couple of my films. Why shouldn’t I spread the news? I’m proud of these films. I’ve added some illustrations from a couple of these films to punch up the post. So over to Mr. Zipes:

- From 1990 to 1992 Michael Sporn, an American animator, adapted three of Andersen’s fairy tales, “The Nightingale,” “The Red Shoes,” and “The Little Match Girl” for Italtoons Corporation, and they are currently distributed by Weston Woods Studios, an educational company. The films, all about twenty-five minutes long and created for children between five and ten, have been shown on HBO, but for the most part they have not received wide public attention, and they can be considered marginal cultural products of the culture industry—all the more reason that they deserve our attention, because Sporn’s films written by Maxine Fisher are profound interpretations of Andersen’s stories that transcend age designation and keep alive Andersen’s legacy. They all use voiceover and colorful still sets as backdrops, and naively ink-drawn characters who come alive because they are so unpretentious and resemble the simple and found art of children.

Two of Sporn’s films are particularly important because they transform motifs from Andersen’s tales to deal with contemporary social problems. Both take place in New York City, and the music and dialogue capture the rhythms and atmosphere of present-day urban life. In The Red Shoes, Sporn depicts the warm friendship of two little black girls, Lisa and Jenny, and how they almost drift apart because of a change in their economic situation. The story is narrated by Ozzie Davis as a shoemaker who lives in a poor section of New York. Lisa and Jenny often visit him, and he describes their lives and how both love to dance and play and enjoy each other’s company. One day Lisa’s family wins the lottery, and they move to another part of the city. Now that she is rich, Lisa ignores Jenny until they meet at a ballet about red shoes. The spoiled Lisa ignores Jenny, but later she returns to her own neighborhood and steals some red shoes that the shoemaker had been making for Jenny. Guilt-ridden, Lisa finds that the red shoes have magic and bring her back to the old neighborhood and help her restore her friendship with Jenny.

Two of Sporn’s films are particularly important because they transform motifs from Andersen’s tales to deal with contemporary social problems. Both take place in New York City, and the music and dialogue capture the rhythms and atmosphere of present-day urban life. In The Red Shoes, Sporn depicts the warm friendship of two little black girls, Lisa and Jenny, and how they almost drift apart because of a change in their economic situation. The story is narrated by Ozzie Davis as a shoemaker who lives in a poor section of New York. Lisa and Jenny often visit him, and he describes their lives and how both love to dance and play and enjoy each other’s company. One day Lisa’s family wins the lottery, and they move to another part of the city. Now that she is rich, Lisa ignores Jenny until they meet at a ballet about red shoes. The spoiled Lisa ignores Jenny, but later she returns to her own neighborhood and steals some red shoes that the shoemaker had been making for Jenny. Guilt-ridden, Lisa finds that the red shoes have magic and bring her back to the old neighborhood and help her restore her friendship with Jenny.

In The Little Match Girl, Sporn depicts a homeless girl, Angela, who sets out to sell matches on New Year’s Eve 1999 to help her family living in an abandoned subway station on Eighteenth Street. She meets a stray dog named Albert who becomes her companion, and together they try to sell matches in vain at Times Square. The night is bitter cold, and they withdraw to a vacant lot where Angela lights three matches. Each time she does this, she has imaginary experiences that reveal how the rich neglect the poor and starving people in New York City. Nothing appears to help her, and when she tries to make her way back to the subway station, she gets caught in a snowstorm, and it seems that she is dead when people find her at U nion Square the next morning. However, she miraculously recovers, thanks to Albert, and the rich people gathered around her (all reminiscent of those in the dream episodes) begin to help her and her family.

In The Little Match Girl, Sporn depicts a homeless girl, Angela, who sets out to sell matches on New Year’s Eve 1999 to help her family living in an abandoned subway station on Eighteenth Street. She meets a stray dog named Albert who becomes her companion, and together they try to sell matches in vain at Times Square. The night is bitter cold, and they withdraw to a vacant lot where Angela lights three matches. Each time she does this, she has imaginary experiences that reveal how the rich neglect the poor and starving people in New York City. Nothing appears to help her, and when she tries to make her way back to the subway station, she gets caught in a snowstorm, and it seems that she is dead when people find her at U nion Square the next morning. However, she miraculously recovers, thanks to Albert, and the rich people gathered around her (all reminiscent of those in the dream episodes) begin to help her and her family.

Sporn’s films are obviously much more uplifting than Andersen’s original tales. But his optimism does not betray Andersen’s original stories because of his moral and ethical concern in Andersen and his subject matter. In fact, his films enrich the tales with new artistic details that relate to contemporary society, and they critique them ideologically by focusing on the intrepid nature of the little girls rather than on the power of some divine spirit. At the same time, they are social comments on conditions of poverty in New York that have specific meaning and can also be applied to the conditions of impoverished children throughout the world. What distinguishes Sporn’s films from Andersen’s stories is that he envisions hope for change in the present, whereas Andersen promises rewards for suffering children in a heavenly paradise.

Sporn’s films are tendentious in that they purposely pick up tendencies in Andersen’s tales to express some of the same social concerns that Andersen wanted to address. His critical spirit is maintained, and even some of his faults are revealed. Most important, he is taken seriously.

It’s a pleasure to be taken seriously, and I have to thank Jack Zipes for that.

Photos &Steve Fisher 10 Apr 2011 07:30 am

Springing Ahead

- Checking in with Steve Fisher, here are some of the recent photos he’s taken around New York.

Starting with the NY Botanical Garden in the Bronx:

Right out of Disney’s Alice in Wonderland.

To remind us of the hard winter we’ve just gone through, the local trees haven’t bloomed as yet.

Then there are these interior images of the former Bowery Savings Bank on 42nd Street.

Then a bit down the block is Grand Central Station – inside and out.

Outside

Finally there’s this still life with color.

Animation &Animation Artifacts &Disney 06 Apr 2011 06:54 am

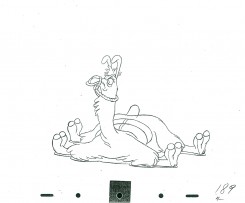

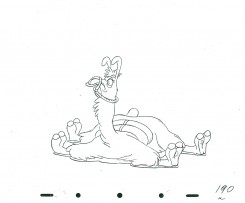

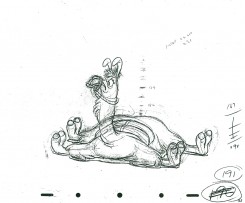

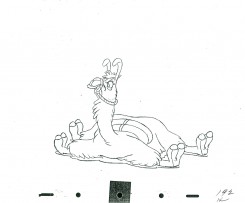

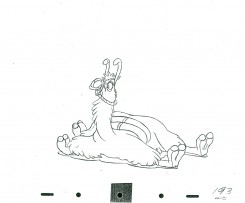

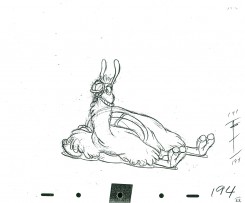

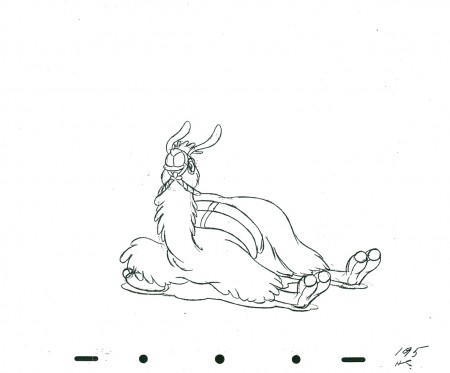

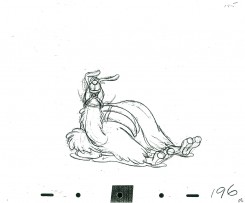

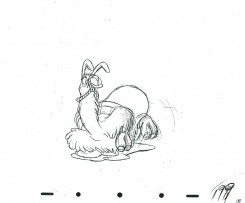

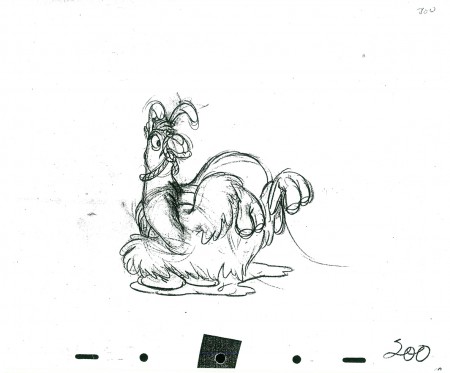

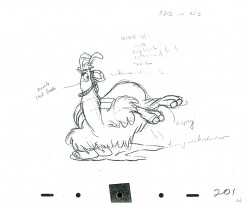

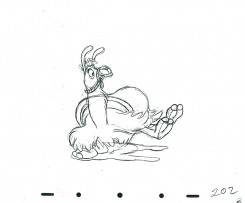

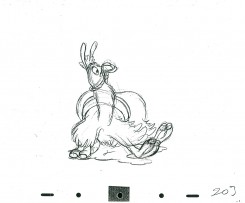

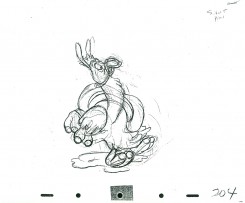

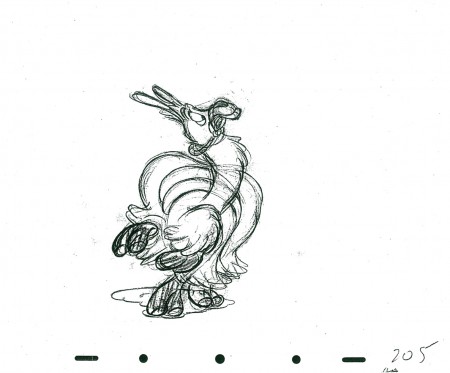

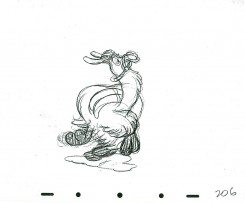

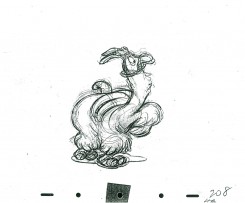

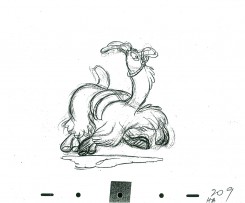

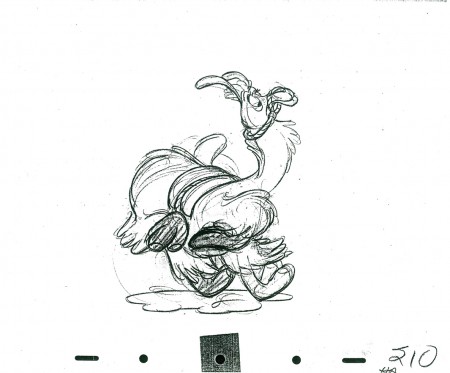

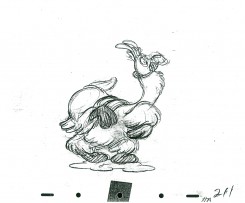

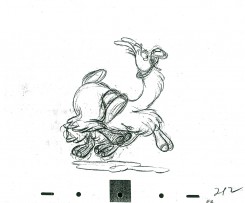

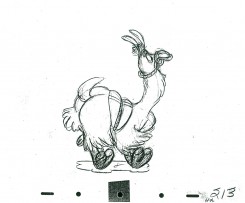

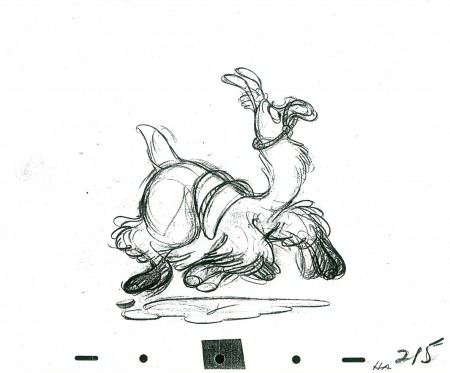

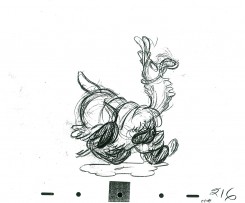

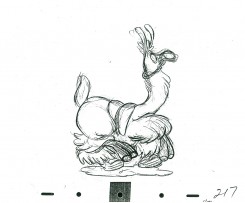

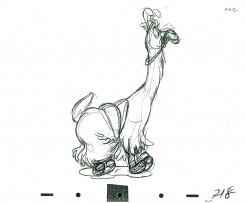

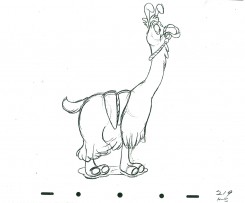

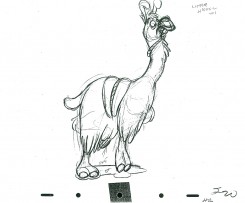

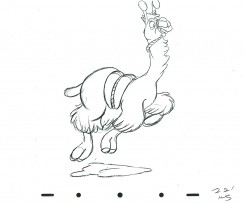

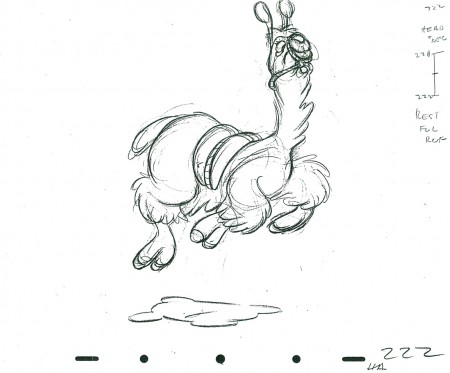

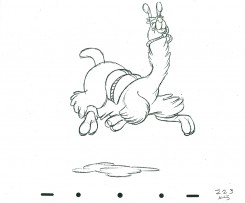

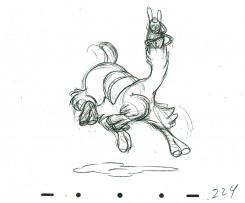

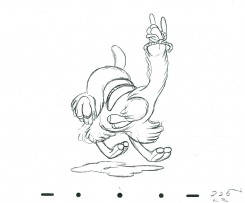

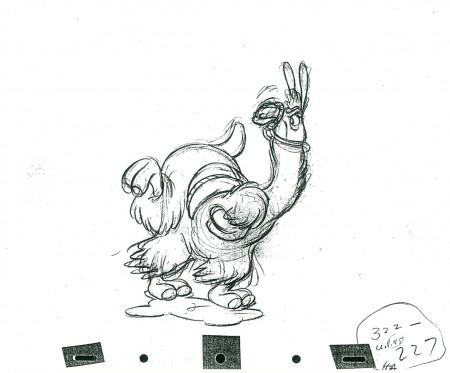

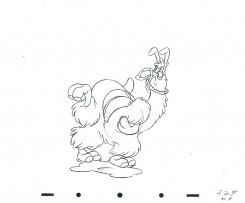

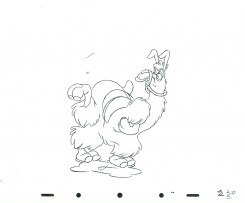

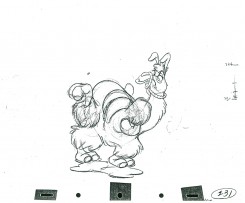

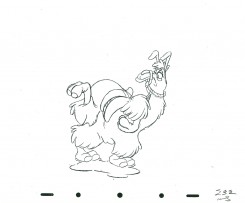

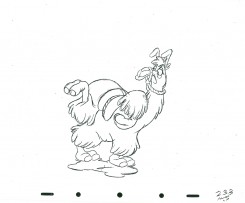

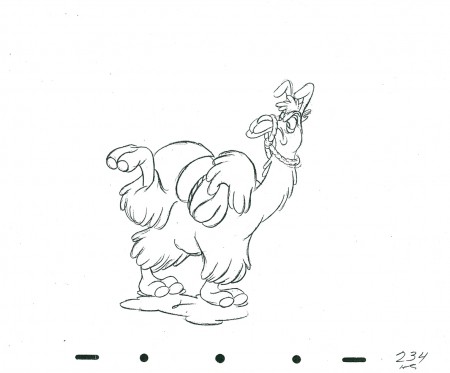

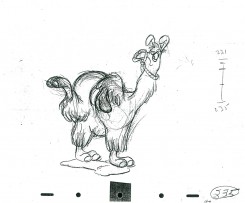

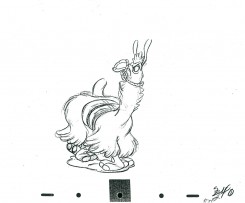

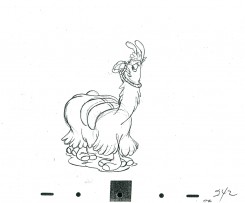

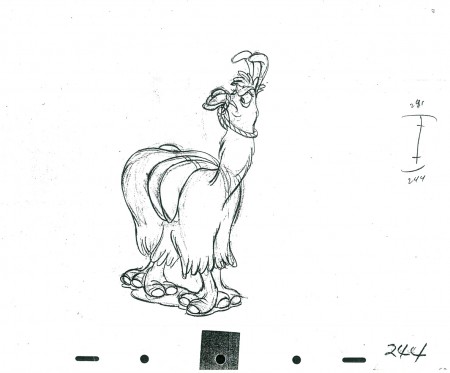

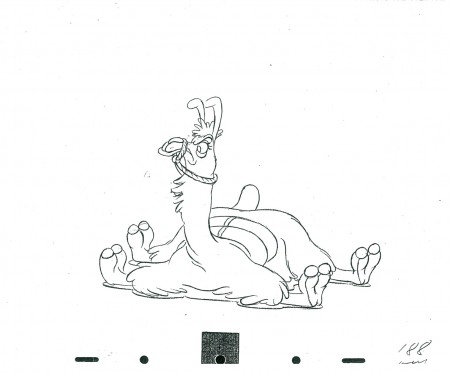

Kahl’s Llama – part 4

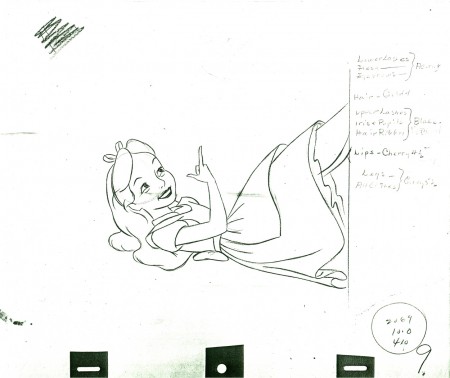

- On to the next section of the Dancing Llama animated by Milt Kahl for Saludos Amigos. Much has been made of this comedic scene by Milt Kahl, who was known for his animation of dramatic characters (Prince Philip, Peter Pan, Alice etc.). Kahl says in the recently posted interview with Mike Barrier that he was “outmaneuvered”.

- Barrier: In your own animation, you frequently were given difficult human characters, as opposed to the funnier characters …

Kahl: Yes, I was. I got stuck with Pinocchio—well, I don’t feel I got stuck with Pinocchio, because it was an opportunity for me. But on Alice in Wonderland, who did Alice; on Peter Pan, who did Peter Pan and Wendy and John and Michael. I don’t think it was because I was better at doing that sort of thing, I think it was because I was outmaneuvered. I would have given my eye teeth to do the Cheshire Cat or the Queen of Hearts …

Barrier: … the mad tea party …

Kahl: Well, yes. But some of these things were more fun, let’s put it that way. I didn’t mind Alice—I wouldn’t have minded Alice so much if I could have done all of Alice. But I didn’t, and there’s so much terrible stuff in the picture, where live-action was used and it wasn’t used well. Some of these people weren’t even up to doing stuff from live action.

It’s obvious Kahl was having fun when he did this character. The first drawing here is the last drawing given on Part 3.

188

________________________

188

________________________

The following is a QT of this part of the scene with all the drawings posted here.

Thanks to John Canemaker for the loan of the scene to post.

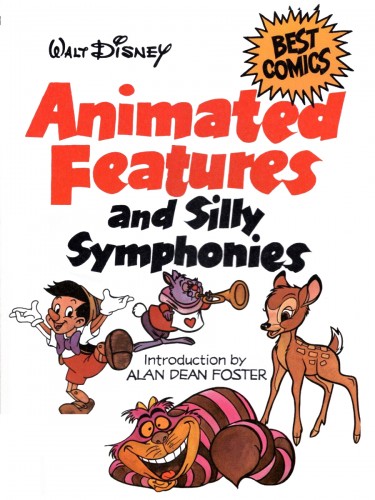

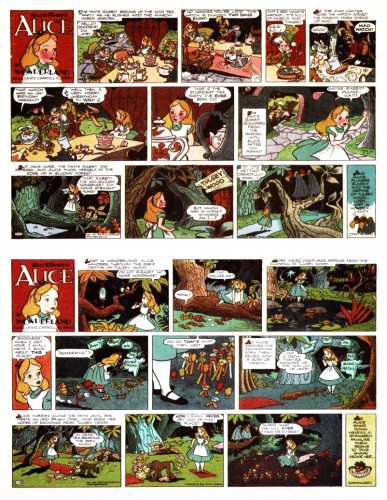

Bill Peckmann &Comic Art &Disney 17 Dec 2010 09:03 am

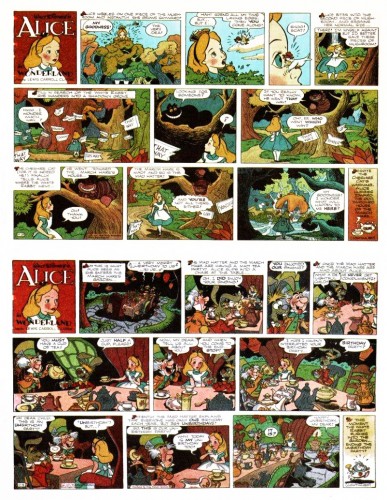

Alice Comix – pt 2

.

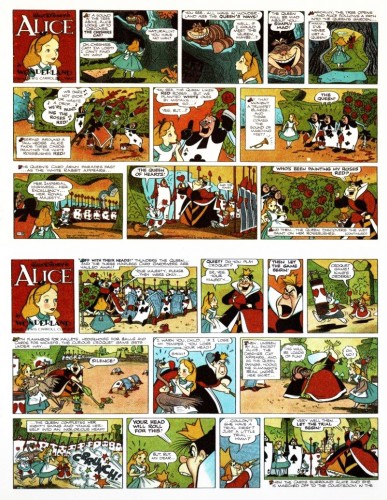

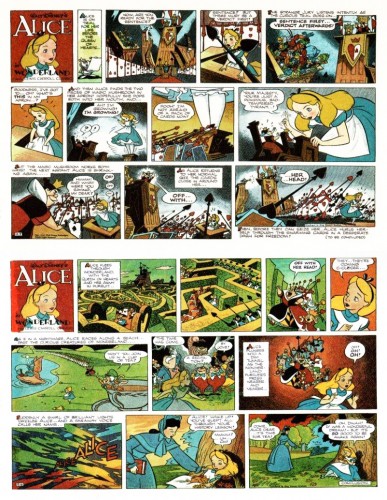

- Last month I posted some Part 1 of strips of Alice In Wonderland taken from from the excellent book Bill Peckmann owns: Animated Features and Silly Symphonies.

The strips are dated 1951, and each page contains 2 Sunday strips. I believe the artwork is by Manuel Gonzales, penciler, and Dick Moores, inker. Gorgeous stuff.

Here we continue with the next 8 strips of the series to conclude the story.

Many thanks go out to Bill Peckmann for the scans and loan of the material.

Enjoy.

9-10

9-10(Click any image to enlarge.)

Animation Artifacts &Disney &Frame Grabs 18 Nov 2010 08:37 am

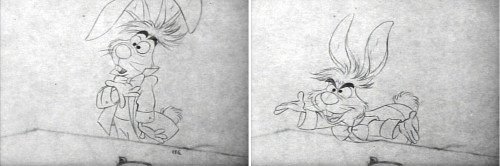

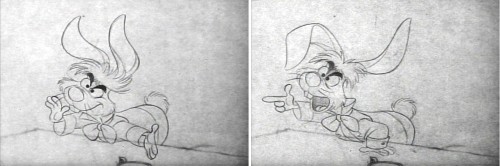

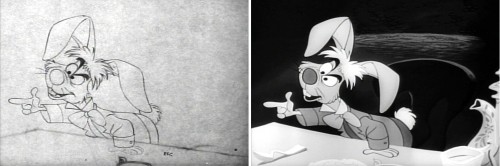

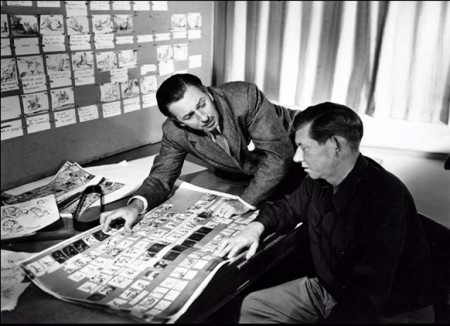

Operation Wonderland

- On the DVD of Alice in Wonderland, there’s an extra little short that supposedly gives you a tour of the studio and a lesson in how animated films are made. (Do you think we’ll ever see one about Dreamworks or Pixar? I’d like to get a video tour of either studio.)

Since I’ve been focussing on Alice’s Milt Kahl scenes, I thought it’d be interesting, as an accompaniment, to post some frame grabs from this theatrical short that was done to promote Alice.

1

1(Click any image to enlarge.)

2

2

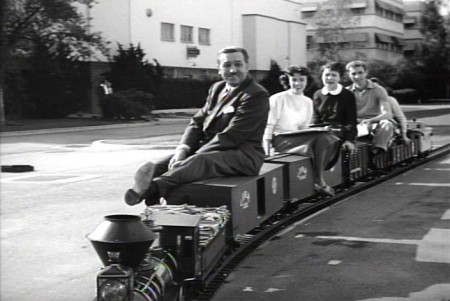

Of course, the film has to start with Walt

riding a toy train around the studio.

3

3

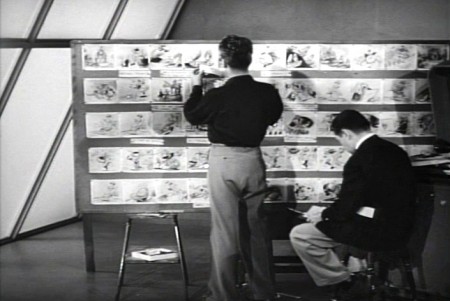

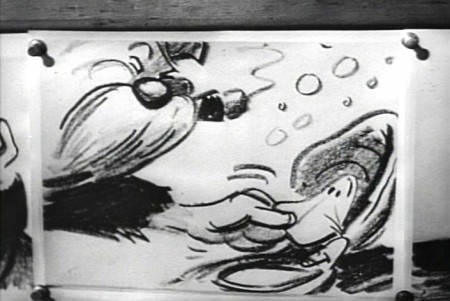

Two storyboard guys sitting in the middle of the studio.

4

4

Storyboard: the walrus grabs a clam.

5

5

Ward Kimball in a funny jacket.

6-7

6-7

The actor posing as the Walrus for the camera.

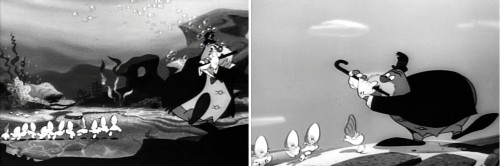

9-10

9-10

The Walrus & Carpenter sequence.

12

12

Walt and Winston Hibler. Hibler eventually narrated

most of the Disneyland shows and True-Life adventures.

14

14

Flowers from storyboard to final film.

15

15

Walt gives a demo of the animation camera and

seems to be wrinkling the cels as he does this.

16

16

Walt operating an animation camera. Ludicrous.

17

17

Walt and Kathryn Beaumont (who’s

supposed to be doing schoolwork.)

18

18

Kathryn Beaumont and Ed Wynn.

20

20

John Lounsbery on the right. The other animator looks to be

Fred Moore. Older and heavier than we’ve seen him in the past.

22

22

More of wacky Ward Kimball pretending to draw.

23

23

Kathryn Beaumont and Jerry Colonna.

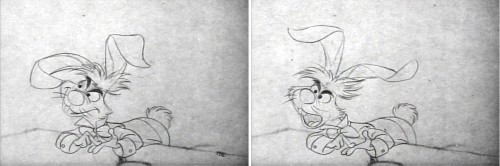

25

25

Jerry Colonna leads us into pencil test of the scene.

27

27

This scene was animated by Ward kimball & Cliff Nordberg.

46

46

John Lounsbery is on the left.

I’m not sure who the other two are.

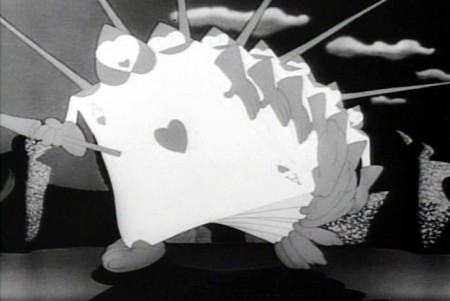

47

47

The cards in action in the film.

49

49

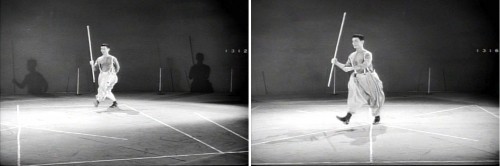

One of the highlights of the film is this dancer doing

march steps for the cards – to be studied.

50

50

The multiplane camera in operation.

51

51

The cameraman at the top always looks a bit devilish.

52

52

No “how animation is made” film would be complete

without the sound effects guys making a racket.

54

54

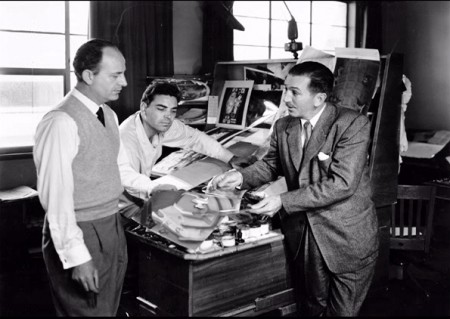

Walt going over some artwork with

John Hench (L) and Claude Coats (center)

Thanks to Hans Bacher and Gunnar Andreassen for identifying them.

55

55

Before riding his toy train into the sunset, Walt sits

in front of his real toy, the multiplane camera.

If anyone can identify any of those I couldn’t, or if you think I’ve mistakenly identified anyone, please leave a comment.

There’s an art gallery of images, many of which are by Mary Blair (and I’ve already posted her pictures a while back.) I’ll finish this post with some more of the images on the dvd.

1

1Mary Blair in B&W.

4

4

Thiis looks like it comes from HOPPITY GOES TO TOWN.

To see more Mary Blair designs for Alice go here.

Animation &Animation Artifacts &Disney 17 Nov 2010 08:13 am

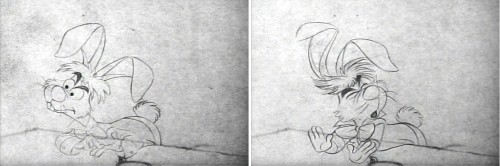

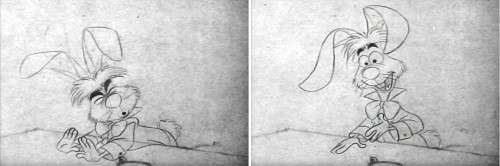

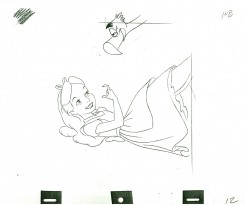

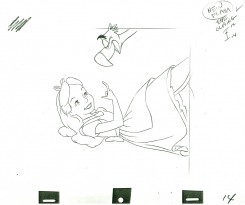

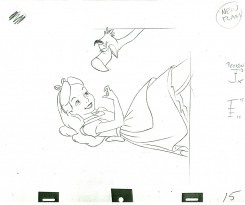

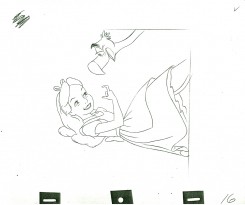

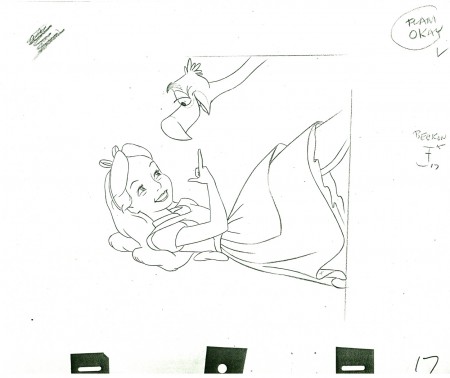

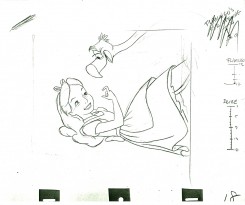

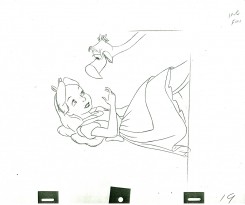

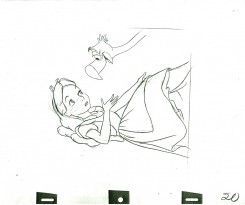

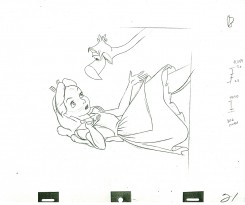

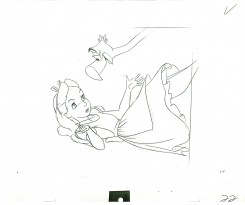

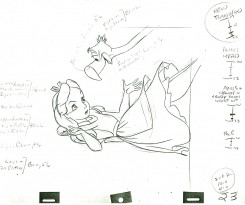

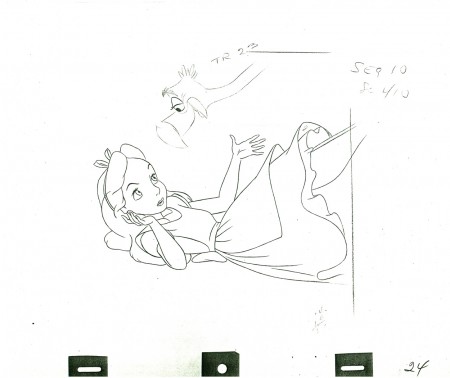

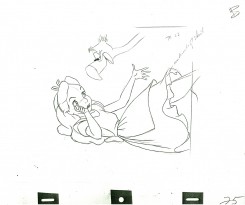

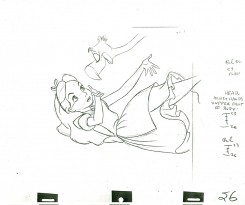

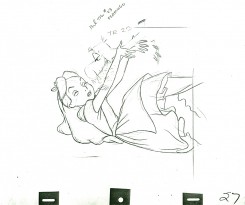

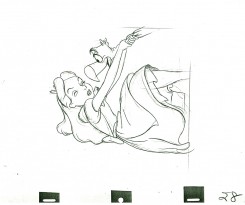

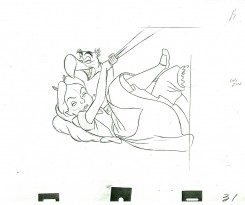

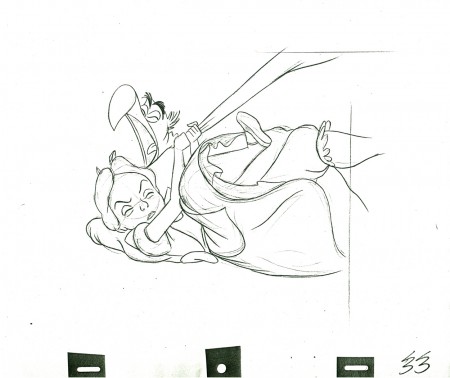

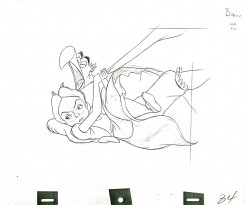

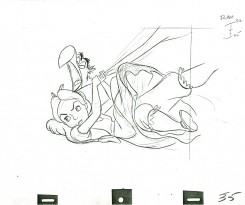

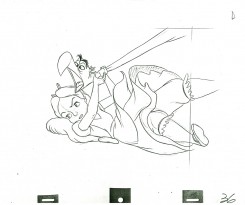

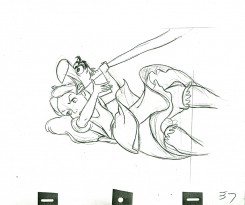

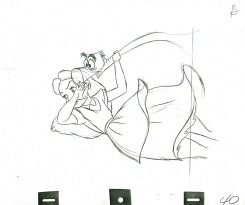

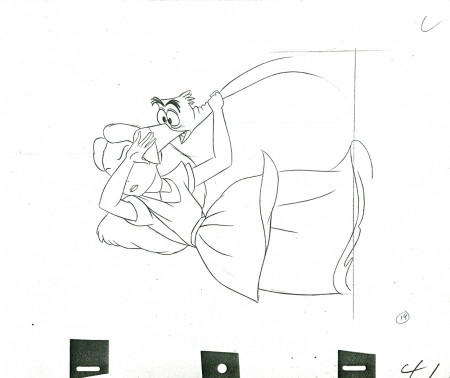

Milt’s Alice – 3

- Here’s another scene animated by Milt Kahl for Alice In Wonderland. Alice’s tangled up with the flamingo trying to play croquet with the Red Queen. Sticky wicket.

The scene was loaned to me by Lou Scarborough. Many thanks are in order.

9

9(Click any image to enlarge.)

________________________

Here’s a QT movie of the action layed out above. Since the scene has been inbetweened, it’s exposed, for the most part, on ones.