Search ResultsFor "animal farm"

Articles on Animation &Independent Animation 13 Jan 2010 09:02 am

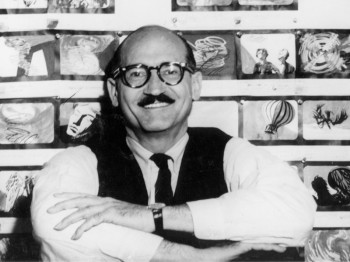

Canemaker meets Dunning – 1980

The Jan-Mar 1980 issue of Animafilm included this interview with George Dunning by John Canemaker. John was very taken by the Dunning film in progress, The Tempest, and he starts off his interview with questions about that film.

One has to live

George Dunning talks with John Canemaker

JOHN CANEMAKER: I saw a pencil test of “The Tempest” five years ago on CBS-TV. Are you still working on this film?

GEORGE DUNNING: I am indeed. More so, stronger on it than I was then. I’ve got a few hits and pieces in a rather unfinished state and some more going on now. It’s an attempt to he as personal as I can be. My approach is to do a few minutes to present to hackers. To justify doing Shakespeare as an animated film. Obviously live-action with stars and so on is a great advantage in box-office terms. People ask me why do it in animation. It’s all very well with the fantasy side of it, that seems appropriate. But beyond that, it’s something that I think should be demonstrated. And that’s what I’m doing, and then that helps open a technical line on it as well so that others can carry on.

J.C.: Will you be removing the words as you did with the poem you based “Damon the Mower” on?

G.D.: This is a difficult thing to make a statement about cause I’m in the middle of it. I might change my mind and do it all differently. But at this stage I find that I’m always taking out. I’ve taken a sequence of dialogue and cut it enormously -taken out half of it. Then I look at it and I take out more. I keep taking chunks away. I think this is legitimate but I am worried because it is tampering. But at the same time I think the verbal side of it, from a stage point of view, has a kind of function that on film is not necessary, if I could put it that way. I mean it sounds like I’m saying I know how to rewrite Shakespeare and I’m a bit timid about that. I just feel that in the end it is a film that one is making. I’m not rewriting Shakespeare, I’m making a film. In that sense it’s to use the dialogue but to pull a lot of it.

J.C.: The clip I saw showed a tree-like creature walking.

G.D.: That’s Caliban. He’s a tree through the whole thing. I just got carried away with that one phrase where he says, “This island is mine”. It just suddenly hit me, I saw this image of this tree, which is full of creatures as well. It’s sort of an ecology thing all together. And in the end of the play they leave and you have this island with Caliban left. And it’s sort of a hack-to-nature situation.

J.C.: Will you he mixing graphic techniques in the film?

G.D.: At this point it isn’t that far-out as far as technical things are concerned. I’ve been using ccl levels and Xerox drawings. It’s an attempt to keep things handle-able and in a condition where others can help. Cause if you get to do it in a technique which only one person can do it’s very limiting obviously.

(Click any image to enlarge.)

J.C.: Do you work out of a studio in London?

G.D.: Yes, our studio is TVC London. It’s based on the name TV Cartoons. Auspicious name! And we’re having our twenty- first birthday this year. In June we had it. It’s really a studio Dick Williams has had a lot to do with in the sense that he did a great deal to help in the early days to get it started. When I got to London he was working on “The Little Island”, and I helped him a little bit on that. Then he did a lot of commercials, a lot of stuff sort through our studio. I was sent over to London by Bosustow and UFA to set up a UFA satellite. They wanted to get some more footage for the “Gerald McBoing Show” on CBS. In those days Bosustow was on a big expansion drive and he sent Leo Salkin and me over to set that up. We set it up and seven months later UFA was practically bankrupt. This was ’56 or ’57.1 was in this position of going around to agencies cause we were doing commercials at that time and doing very well. Everyone was very glad that UFA was in London and so on. And Dick was doing commercials with us. So then I went around to all the agencies to say good-bye and they said, “Oh, stay. Can’t you keep this thing going? It’s marvelous”. So it was a matter of trying to make a set-up which I did with some businessmen. I had long talks with Dick, saying “What’ll I do…” And he said “I’ll help you and stick with it. This is great and you should stay on.” The prospect otherwise was

first birthday this year. In June we had it. It’s really a studio Dick Williams has had a lot to do with in the sense that he did a great deal to help in the early days to get it started. When I got to London he was working on “The Little Island”, and I helped him a little bit on that. Then he did a lot of commercials, a lot of stuff sort through our studio. I was sent over to London by Bosustow and UFA to set up a UFA satellite. They wanted to get some more footage for the “Gerald McBoing Show” on CBS. In those days Bosustow was on a big expansion drive and he sent Leo Salkin and me over to set that up. We set it up and seven months later UFA was practically bankrupt. This was ’56 or ’57.1 was in this position of going around to agencies cause we were doing commercials at that time and doing very well. Everyone was very glad that UFA was in London and so on. And Dick was doing commercials with us. So then I went around to all the agencies to say good-bye and they said, “Oh, stay. Can’t you keep this thing going? It’s marvelous”. So it was a matter of trying to make a set-up which I did with some businessmen. I had long talks with Dick, saying “What’ll I do…” And he said “I’ll help you and stick with it. This is great and you should stay on.” The prospect otherwise was

to go back to New York in tatters. It all seemed downhill. I remember Dick came to me exactly a year later and he said, “The year is up.” And I said, “What do you mean, the year is up?” He said, “I said I’ll help you, and give you a push. Now I really want to do stuff through my own company’s name and things like that.” We went on collaborating on some things but he was much more active with the Richard Williams Studio and developed it and so on. I have always had the greatest respect for all his abilities.

to go back to New York in tatters. It all seemed downhill. I remember Dick came to me exactly a year later and he said, “The year is up.” And I said, “What do you mean, the year is up?” He said, “I said I’ll help you, and give you a push. Now I really want to do stuff through my own company’s name and things like that.” We went on collaborating on some things but he was much more active with the Richard Williams Studio and developed it and so on. I have always had the greatest respect for all his abilities.

J.C.: So you set up your own company and were doing commercials?

G.D.: Lots of stuff like that and industrial films.

J.C.: Did you do features before the “Yellow Submarine”?

G.D.: No, we did a Saturday morning (TV) series

J.C.: Did you do features before the “Yellow Submarine”?

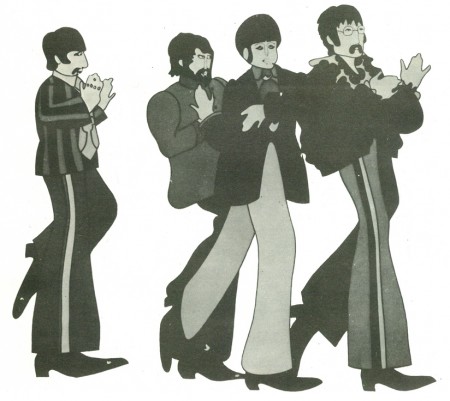

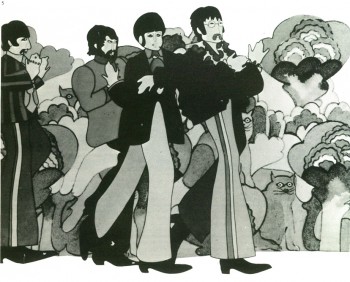

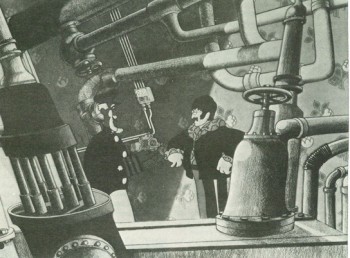

G.D.: No, we did a Saturday morning (TV) series for the Beatles music. King Features organized that with the Beatles and got permission to do cartoon versions of the four of them. It was terrifying. It was a very poor kind of design, but there it was. The show was very ordinary, very cheap cut-rate kind of thing. It was that kind of show with two numbers set into fifteen minutes framing it then another fifteen minutes to make the half hour. We made up a new half hour show one way or another each week, got to the lab then got that onto the plane, had the day off, then started in again, grinding on with this. It was King Features (newspaper syndicate) that had the idea to do a feature-length film and they kept hammering away to Brian Epstein (Beatles’ manager). He didn’t want to buy that for the longest time. Then finally agreed.

J.C.: Which would be around 1967?

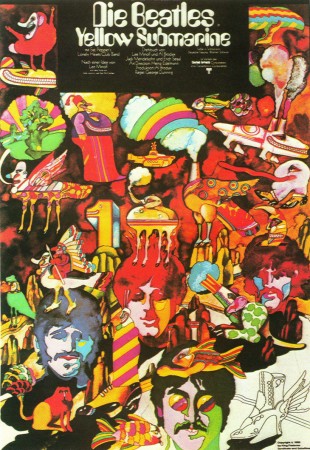

G.D.: Yes. So that’s why our studio did the thing. As I said, the design of the characters in the TV show was hopeless, although King Features had no objection. They were completely without any point of view on the thing. It was sort of business. We were desperate and I was jumping around like mad because I knew that had to be really well solved or we were dead. I tried with different kinds of designs. We got a bit of track of the four boys talking after they’d left the pot open once on a recording. So we took this talk and animated to it and kept testing and trying different things. We saw and had admired Heinz Edelmann’s graphic designs in “Twin” magazine. And thought why don’t we even try him. So we got in touch with him, he flew over and we showed him what we were doing and he disappeared for two weeks. I remember this brown envelope arrived with four drawings in it, one of each Beatle. It was really marvelous cause it had that solved, attended-to quality. You could see it wasn’t Mickey Mouse, it wasn’t this, it wasn’t that – it was just there! The film is very much a phenomenon.

G.D.: Yes. So that’s why our studio did the thing. As I said, the design of the characters in the TV show was hopeless, although King Features had no objection. They were completely without any point of view on the thing. It was sort of business. We were desperate and I was jumping around like mad because I knew that had to be really well solved or we were dead. I tried with different kinds of designs. We got a bit of track of the four boys talking after they’d left the pot open once on a recording. So we took this talk and animated to it and kept testing and trying different things. We saw and had admired Heinz Edelmann’s graphic designs in “Twin” magazine. And thought why don’t we even try him. So we got in touch with him, he flew over and we showed him what we were doing and he disappeared for two weeks. I remember this brown envelope arrived with four drawings in it, one of each Beatle. It was really marvelous cause it had that solved, attended-to quality. You could see it wasn’t Mickey Mouse, it wasn’t this, it wasn’t that – it was just there! The film is very much a phenomenon.

J.C.: It’s a time capsule of the sixties.

G.D.: It is that. That’s the contribution of many people. The film would have had a life because of the Beatles music.

That’s a separate consideration. And the fact that Heinz solved that side of it was so great and that was marvelous.

We had a budget of a million dollars, and eleven months to do it. The Beatles took $ 200,000, off the budget. There were three animation directions on it: Jack Stokes, who learned his trade with a group of people – a whole generation of animators in London – from a Disney man who came over, David Hand (Director of “Snow White”). Eddie Radich was another animation director on “Submarine”; Bob Balser, who has been for a long time in Barcelona. He’s the third director.

We had a budget of a million dollars, and eleven months to do it. The Beatles took $ 200,000, off the budget. There were three animation directions on it: Jack Stokes, who learned his trade with a group of people – a whole generation of animators in London – from a Disney man who came over, David Hand (Director of “Snow White”). Eddie Radich was another animation director on “Submarine”; Bob Balser, who has been for a long time in Barcelona. He’s the third director.

There was a period of about five months where we had 200 people working together in out studio in Soho Square. My memory of that time is that it was amazingly unfrantic, in the sense of devoted and productive. Everybody was very grim, hardworking. The whole atmosphere was “We’ll show them” meaning the rest of the world “that we can do this in London.” This odd thing of making a feature.

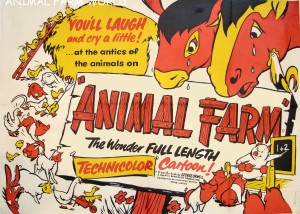

J.C.: This was the first British feature since “Animal Farm”?

G.D.: Absolutely yes. The film made money left and right. But it didn’t for TVC and very nearly bust us. That’s a very long and very bitter story. We had a really nasty time of it. We went over the budget, not a large amount over. The producer people through King Features organized to take over the company. And we learned an awful lot. Very bitter situation. After it was all over it got smoothed down. We repaired our relationship with King Features. But the whole thing was very sour.

J.C.: You have retained your credentials as a film artist by making personal films. Is your work at TVC to help you to continue as an independent artist?

J.C.: You have retained your credentials as a film artist by making personal films. Is your work at TVC to help you to continue as an independent artist?

G.D.: I would guess that is the answer, yes. One has to live. I had a long stint at the Canadian Film Board. I learned a lot and enjoyed that kind of existence – government backing, budgets for films and all kinds of special facilities that you could get that way, that you don’t get out in the cold world of commerce.

J.C.: Who were some of the artistic influences in your career?

G.D.: McLaren. Alexeleff. Bartosch. Then there’s that whole world of Disney stuff that we’d all he poorer without, and I think in hits and pieces and in various ways it’s been an enormous influence.

J.C.: What is your age?

G.D.: 57

J.C.: Thank you very much for your time.

G.D.: Pleasure.

GEORGE DUNNING (1920-1979): FILMOGRAPHY

1943: J’AI TANT DANSE (I have danced so much), AUPRES DE MA BLONDE (By my blonde, Chants populates), 1944: GRIM PASTURES, 1945: THREE BLIND MICE, 1946: CADET ROUSSELIE, (UPRIGHT AND WRONG), 1947: THE ADVENTURES OF BARON MUNCHHAUSEN, FAMILY TREE (with Evelyn Lambard), 1959: THE WARDROBE, 1962: THE FLYING MAN, THE APPLE, 1968: CHARLEY, THE LADDER, THE YELLOW SUBMARINE, 1970: MOON ROCK, 1973: THE MAGGOT.

Publicity and sponsored films including: 1946: DISCOVERY – PENICILLIN, 1958: THE STORY OF THE MOTOR-CAR ENGINE, 1962: THE EVER-CHANGING MOTOR-CAR, 1962-65: THE ADVENTURES OF THUD AND BLUNDER (safety film for the Coal Board), 1966: BEATLES (TVseries with Jack Stokes), CANADA IS MY PIANO (with Bill Sewell).

Commentary &Disney 30 Dec 2009 08:49 am

Another look at 2 features

- I’ve seen a couple of this year’s features another time this past week and have had some more thoughts about them.

I’ve now seen The Fantastic Mr. Fox a third time. Twice in theaters and once on DVD. All three times it was every bit as entertaining for me as it was on the first viewing. I was more impressed with the levels of depth cleverly written within the film.

I’ve now seen The Fantastic Mr. Fox a third time. Twice in theaters and once on DVD. All three times it was every bit as entertaining for me as it was on the first viewing. I was more impressed with the levels of depth cleverly written within the film.

There are the same father/son complications of every Wes Anderson film, however more interesting to me was the thought on the nature of the film’s creatures.

The Royal Tenanbaums treat each other as if they are Royal. The Foxes are wild animals; they know it and allow their true nature to emerge. Look at every time they eat, attacking wildly and voraciously.

The Royal Tenanbaums treat each other as if they are Royal. The Foxes are wild animals; they know it and allow their true nature to emerge. Look at every time they eat, attacking wildly and voraciously.

The animals in costume are little more than their natural selves: a fox is a fox and it’s unable to resist its natural, wild tendencies. A badger is a badger and tempers will rise when mixing with a fox. Though he’s a friend and lawyer to the fox, the two spit and spat whenever they meet.

This is not the same lax world as many past cartoon creations. Bugs Bunny was rarely, if ever, a bunny. He was more a foil for Elmer Fudd (or in some cases Daffy Duck, who started life as a duck but became something other.) Mickey Mouse could mix with Donald Duck, or Goofy, and all could just act as humans do with little regard for their off-sized proportions or animal natures. (Admittedly, Pluto always stayed a dog despite the fact that Goofy was also a dog, and Mickey Mouse was his owner and larger than the dog.)

This is the cartoon world, and there’s nothing wrong with it. It’s just that Mr. Fox takes it into a different direction – thanks to the spirit of Raold Dahl, which Wes Anderson followed closely. And in doing that Anderson asks what is our true nature? What is wild within us when we, as adults, seem to have learned to temper those base instincts.

The animation of some of the Beatrix Potter stories have followed the animal natures of the characters, but adaptations of The Wind in the Willows have not followed the book’s logic. In the book the animals ARE pointedly animals – despite wearing clothes and acting more human-like.

To me, the film is witty, charming and wholly satisfying. Even the stodgy, stiff animation is part of the appeal. There’s a quaint and homespun feeling to the characters in this old-time, hand-made animation. Sitting next to me in the theater, this last time, was a mother (about 30) with her son (about 10). She was quiet during the film, he was certainly enjoying it. When the film ended, the boy asked his mother excitedly, “Didn’t you just love the farmer?” The mother hesitated for a long time, then said, “I guess so.” She seemed not to enjoy the film while her son gushed over it all the way out of the theater. Not all films are for everyone.

The Princess and the Frog I saw for a second time on DVD. Actually, I could only make it through about 2/3 of the film on the second viewing. Its flaws were larger for me on the small screen and at second viewing.

The largest hurdle for me on the first viewing was the story, and it remained the complete shambles it was the second time out. It’s an embarrassment to me that this film came out of the Disney studio with no one noticing how poor the story and the storytelling is.

The only joy was in seeing animation so rich – not always good but always rich and professional. It’s been a while since we’ve had even that.

The only joy was in seeing animation so rich – not always good but always rich and professional. It’s been a while since we’ve had even that.

The movement and character development, in this film, was often more Warner Bros than Disney – wilder, broader and hard-edged. The last few Disney 2D features seemed to be making a split. Half the animation seemed very Don Bluth while the other half was more WB. This, of course, was just my perception. Only a couple of animators seemed distinctly out of the Disney mold – Andreas Deja and Glen Keane, for two.

I like Andreas Deja‘s animation of the voodoo queen, Mama Odie, introduced to us in the last third of the film. (Really! Was there no way to introduce this character earlier in the film?! I can think of half a dozen ways to do it, and the film could have used more of her.) Unfortunately, she’s on the screen too short a time to separate her from Mad Madam Mim or The Rescuers’ Madame Medusa.

It’s interesting that the film includes the death of a bug (a bug also introduced in the last third of the film), and that’s supposed to make us feel something. Of course, it becomes a star (there must be lots of stars – meaning dead bugs – that we don’t see up there) as the directors try pointlessly to pull the heartstrings. More disheartening than heartfelt.

In Mr. Fox, when the villainous rat dies, no such poor attempt is made to manipulate our emotions. Anderson didn’t sentimentalize the death. “Just another dead rat in the garbage pail behind the Chinese restaurant.”

Daily post 26 Jun 2009 07:38 am

JulesEngelFilms/AnimalFarmFigurines

- Janeann Dill has assembled and released through the Iota Center a DVD collection of the works of Jules Engel vol I.

This first volume of Engel’s selected animation work offers fifteen of his films ranging from one of his earliest experimental works (Carnival, 1963) to one of his last (The Toy Shop, 1998). Arranged chronologically, the collection offers one view of the artist’s progression over almost four decades. Also included is an excerpt from Jules Engel: An Artist For All Seasons, a documentary from Janeann Dill, Ph.D, containing rare footage of his artwork and interviews.

This first volume of Engel’s selected animation work offers fifteen of his films ranging from one of his earliest experimental works (Carnival, 1963) to one of his last (The Toy Shop, 1998). Arranged chronologically, the collection offers one view of the artist’s progression over almost four decades. Also included is an excerpt from Jules Engel: An Artist For All Seasons, a documentary from Janeann Dill, Ph.D, containing rare footage of his artwork and interviews. You can view a sample of Engle’s work on the dvd here.

You can view a small clip from Janeann Dill’s documentary included as an extra on the dvd here.

Here’s the Facebook page devoted to Engel.

Here’s another web page devoted to Engel’s work.

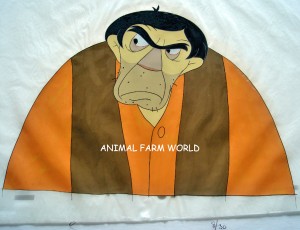

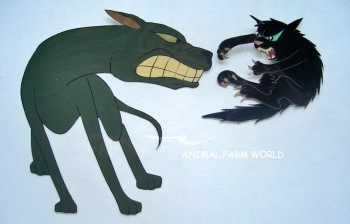

- Chris Rushworth is an avid fan of halas & Batchelor’s Animal Farm. His collection of cels and artwork and other materials for this film is astounding, and he displays them all on his site, Animalfarmworld. As a fan of the film, myself, I can’t help but salivate over some of his materials. Currently, he’s posting some beautiful statuettes that were made at the time of the film. He posts many of these Goebel figurines on a special page. Take a look, if you have any interest.

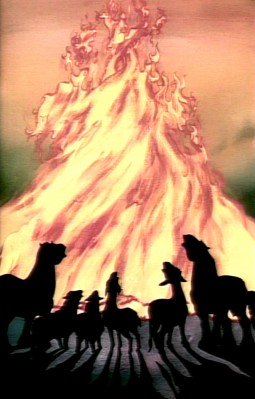

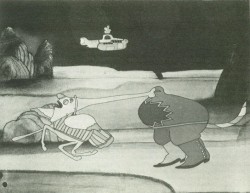

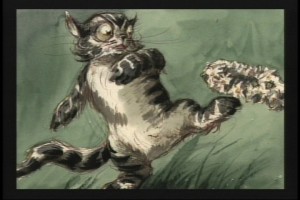

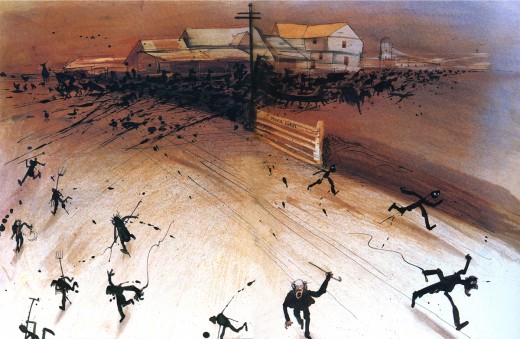

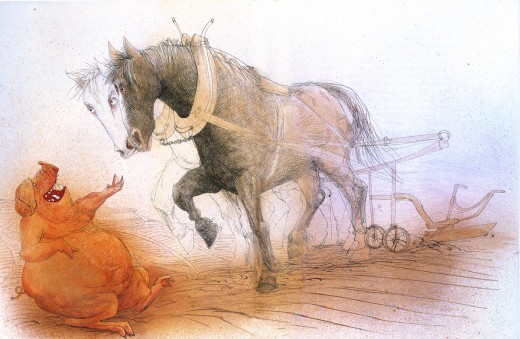

This is one of the many stills Chris Rushworth posts from his collection.

This is a cel I have in my collection. I also have the drawing for the scene.

I’d love to know who did the animation for it.

Does anyone have the drafts for the film?

- Stuart Bury, an animation student at the Kansas City Art Institute, wrote me and asked that I look at a five min. puppet animated film, Dried Up, a short he made with two other students, Isaiah Powers and Jeremy Casper.

- Stuart Bury, an animation student at the Kansas City Art Institute, wrote me and asked that I look at a five min. puppet animated film, Dried Up, a short he made with two other students, Isaiah Powers and Jeremy Casper.

“’Dried Up’ is the story of a quiet old man who, surrounded by desolation and apathy, perseveres to remain true to the nature of his own beliefs and character. He toils daily to forge a last ditch effort to bring hope and life to a faithless, drought ridden old town. ”

The film is quite professional and deserves a look. I’m pleased to see that there’s gold in Kansas City.

_____Stuart Bury

Take a look for yourself. It’s worth the five minutes.

- There’s the opportunity for New Yorkers to see the feature, The Secret of Kells, upcoming to the IFC Center.

- There’s the opportunity for New Yorkers to see the feature, The Secret of Kells, upcoming to the IFC Center.

There will be two shows:

Sat July 18 at 11:00am

Sun July 19 at 11:00am.

You can reserve your tickets here.

Articles on Animation 11 Jun 2009 07:46 am

Journal of Int’l Animated Film

- In 1957, the British Film Academy, directed by Roger Manvell, published a short “Journal” which included reports from a number of writers around the world talking about the animation industries in their respective countries. Somewhat similar to the ASIFA International Bulletins we receive quarterly.

- In 1957, the British Film Academy, directed by Roger Manvell, published a short “Journal” which included reports from a number of writers around the world talking about the animation industries in their respective countries. Somewhat similar to the ASIFA International Bulletins we receive quarterly.

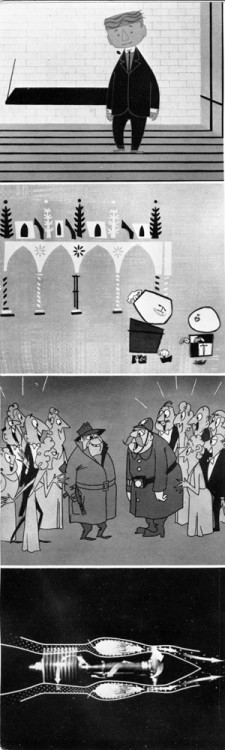

Needless to say, these are all outdated pieces, but there’s some entertainment (at least) to be gathered from reading these reports. The first, naturally enough, came from Great Britain and – appropriate to the times – is Halas & Batchelor-centric.

All of the essays talk about the effect UPA has had on the medium, most particularly Phillip Stapp’s report of the USA. (I’ll probably post that one next week.)

Here’s the state of England in 1957:

IN America, most animation work is linked with the major studios. Tom and Jerry come from the M.G.M. studios, Popeye from Paramount, Tweety Pie from Warners; even the U.P.A. unit works under the general umbrella of Columbia, whilst Disney’s is almost a separate major studio in itself.

IN America, most animation work is linked with the major studios. Tom and Jerry come from the M.G.M. studios, Popeye from Paramount, Tweety Pie from Warners; even the U.P.A. unit works under the general umbrella of Columbia, whilst Disney’s is almost a separate major studio in itself.

In Britain, animation is a family business, operating in the style of the medieval craftsmen’s guilds. The Units tend to stay together in small communities, usually in converted houses or tiny offices. Personnel grow up with their production companies, often entering the business direct from University or Art School. Training is done by experience, as the young learn from the old in the day-to-day work at the animation tables. There is a struggle to maintain continuity of production. Leadership is based on the personality of one or two people who often manage the whole operation as a kind of family concern, imposing their style to a degree which they themselves would scarcely admit, for many strive to encourage as much individual experiment as possible amongst those who work for them.

The Units are divided into four main categories. First, there are the groups who produce sponsored films but, because they have been in existence for a long time and have established some measure of independence, are able to conduct occasional experiments that lead to theatrical distribution, or even to produce films specifically for the entertainment market. Halas and Batchelor Productions are a Unit of this kind.

John Halas came to this country before the War, having worked in Hungary with George Pal; Joy Batchelor first met him in London and shared in the making of animation films, both here and in Budapest. They married and now operate the company under joint control. Like most British Units, they depend on sponsorship of various forms for their existence. This comes from three main sources:

Mr. Finley’s Feelings, Earth is A Battlefield, __1. Official Bodies, Government Departments

Britvic Commercial, The Gas Turbine. ______or International Authorities.

_____________________________________Examples of films made recently in this category include To Your Health, for the World Health Organisation: Basic Fleetwork, for the Admiralty; The Sea, for the Ford Foundation; and The Candlemaker, for the United Lutheran Church in America.

2. Sponsorship through Industry. Recent films include: Power to Fly, for the British Petroleum Company, and Invisible Exchange for Shell.

3. Direct Advertisments, made now mainly for Commerical Television. Halas and Batchelor made the famous Murraymints series, as well as a special series for Dunlop.

Using the resources gained over years of work in the “bread-and-butter” business, Halas and Batchelor have been able to amuse themselves (and very large cinema audiences) with such pictures as their delightful History of the Cinema, which was chosen for the Royal Film Performance in 1956. Of a more serious character was the feature length Animal Farm, a rare example of an attempt to use the cartoon film for the interpretation of a complicated political satire. The Unit that made these films is now ninety strong; it is run personally by John Halas and Joy Batchelor, both of whom are active at every stage in the making of the films as well as handling the complicated business problems that arise in sustaining the flow of the sponsorship so essential to their continued existence. The shaping of spiralling movements around little twirls of Matyas Seiber’s clever wood-wind orchestrations in well-known tunes is characteristic of their work, as well as a love of perky, bouncing little men who tackle everything from Income Tax forms to oil-well drilling with a gay, impertinent but pleasing confidence.

Halas and Batchelor produced the first feature-length cartoon in this country (Animal Farm), the first stereoscopic experiment in animation (The Owl and the Pussycat), and the first major puppet-animation production (Figurehead). Ever since their formation in 1940, they have remained completely independent of any financial links with other organisations.

The second type of Unit in Britain is that devoted entirely to sponsored work, but taking full advantage of the chances offered them by enlightened business concerns to experiment. The William Larkins Studio, operated by Geoffrey Sumner and Theodore Thumwood, was started in 1942 under the name of Analysis Films. It became part of the Film Producer’s Guild in 1947 and, as Larkins Studio, has since produced about 820 short animated films. There are seventy people in the Unit, which turns out about 30,000 feet of final-cut material a year. Personnel tends to remain static, and the Unit’s tradition in training can be gathered from the fact that, on a recent prize-winning film, the average age of the production team was 23.

As in the case of Halas and Batchelor, :ertain of their films have broken through to he theatrical field, although they have not so ~ar made films except to order. Men of Merit, “or example, was shown in some 3,000 cinemas in this country alone; 602 copies were printed by Technicolor. The studio’s style is still, perhaps almost unconsciously, influenced by the work of Peter Sachs, notably by his angular figures, clear-cut lines and sharply-defined backgrounds, in which detail is reduced to a minimum. Earth is a Battlefield, their current production, has a clever extension of the technique in a series of disjointed, cut-out figures which perform to a sound track in the rhyming style of Enterprise, an earlier film by Peter Sachs.

The third main type of animation Unit is exemplified by Nicholas and Mary Spargo’s group at Henley-on-Thames. Formed to produce material specifically for Commercial Television, the Unit now consists of eleven people working in a large room over a shop in the centre of the town. Following the well-established pattern, there are already two trainees in the group, working on the fifteen, thirty- and fifty-second commercials for which the Unit was set up. Because they are lively and imaginative, work flows at a fast pace; Nicholas Spargo spends much of his time on the business side at the moment, while his wife is usually to be found in the studio. Both gained their experience in the tough school of the David Hand Unit at Cookham.

In addition to the independent units, there are a number of small animation groups in Britain attached to certain large organisations like the Shell Film Unit. Francis Rodker and a small team of specialists have been producing excellent diagrams and animated sections for the Shell Unit since its formation in 1935. Three animation cameras are in use, each producing about 4,000 feet of exposed film a year.

A Short Vision, Down a Long Way

Finally, there are the experimental groups, whose status borders between professional and amateur. Typical is the case of Joan and Peter Foldes, who produce animated films in their own home in Edgware. Peter Foldes, like John Halas, came to London from Hungary; he met his wife here and they now work together on all their films. Animated Genesis, their first film, was made on their own resources up to picture rough-cut stage. It was then shown to the British Film Institute, who persuaded Sir Alexander Korda to see it; he completed the sound track and gave the picture distribution through British Lion. A Short Vision, the six-minute story of an artist’s impression of the world destroyed by nuclear fission, was also made as a private venture in the beginning; it was completed with the help of the British Institute’s Experimental Production Fund, and later shown on American television.

The personal quality of British animation films derives from the struggle for independence, the imprint of a beneficent sponsorship and the style of those who founded their own groups and continue to run them. The system is not without drawbacks. Experiment, especially in subject matter, is always subordinate to the needs of the sponsor. Full public screenings are the exception, however delicate the advertisement. The Units are too busy with their own work to indulge in large-scale publicity. They have to contend with the fact that the major circuits are, by-and-large, completely deaf to their work. By contrast many European countries encourage the work of their animation units.

In spite of these difficulties, British animated films have won many international awards. These films are being used increasingly in the United States, both in the cinemas and over television. The battle for a screening is being won at long last; in every country, except Britain.

Articles on Animation &Puppet Animation 15 Nov 2008 09:44 am

Harryhausen Interview

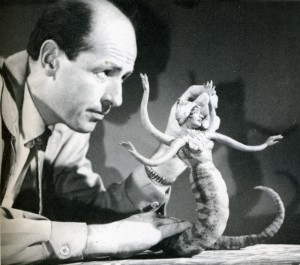

- It’s been a while since I’ve posted anything about stop-motion animation, and seeing an attractive poster for Coraline made me realize it was time. I’ve recently posted some articles from the Millimeter/1975 animation issue which was edited by John Canemaker. This is another excellent piece from the same magazine, and I think it a good one.

An Interview with the Master of Stop-Motion Animation

by Mark Carducci

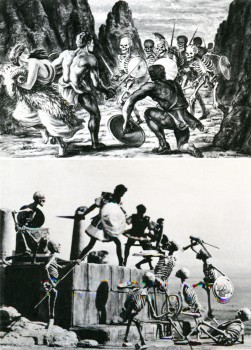

Film history records the earliest three-dimensional animator as George Melies, the showman-turned-filmmaker of A TRIP TO THE MOON fame. Melies, unlike many special-effects men of today, realized the value in using several different effects processes at the same time. Thus he would utilize stop-action, animation, miniature photography and mechanical effects all in the same frame. Melies was a pioneer in the field of effects animation in three dimensions, and he paved the roads other animators would one day travel. One such traveler was Willis H. O’Brien. O’Brien single-handedly elevated the techniques of three-dimensional model animation to a fine art, beginning in the silent era with short subjects and continuing through the 1925 classic THE LOST WORLD to KING KONG a mere eight years later. As Kong was king of Skull Island, so O’Brien was king of model manipulation, and tike Melies before him, O’Brien never missed an opportunity to add drama, atmosphere or pathos by mixing effects together. Witness the clash between Kong and a flying reptile atop Kong’s mountain lair: Kong and the pterodactyl are jointed foot-high foam rubber models; the mountain’s ledge is a plaster recreation; the sky background is a painting on glass; the flying reptiles in the sky are double-printed eel animation. It was this intelligent and intentional combining of effects that allowed O’Brien to achieve the marvelous sense of reality he did in KING KONG, a reality so intense as to make a thirteen-year-old named Raymond Harryhausen choose the field of special effects animation as his life’s work.

Film history records the earliest three-dimensional animator as George Melies, the showman-turned-filmmaker of A TRIP TO THE MOON fame. Melies, unlike many special-effects men of today, realized the value in using several different effects processes at the same time. Thus he would utilize stop-action, animation, miniature photography and mechanical effects all in the same frame. Melies was a pioneer in the field of effects animation in three dimensions, and he paved the roads other animators would one day travel. One such traveler was Willis H. O’Brien. O’Brien single-handedly elevated the techniques of three-dimensional model animation to a fine art, beginning in the silent era with short subjects and continuing through the 1925 classic THE LOST WORLD to KING KONG a mere eight years later. As Kong was king of Skull Island, so O’Brien was king of model manipulation, and tike Melies before him, O’Brien never missed an opportunity to add drama, atmosphere or pathos by mixing effects together. Witness the clash between Kong and a flying reptile atop Kong’s mountain lair: Kong and the pterodactyl are jointed foot-high foam rubber models; the mountain’s ledge is a plaster recreation; the sky background is a painting on glass; the flying reptiles in the sky are double-printed eel animation. It was this intelligent and intentional combining of effects that allowed O’Brien to achieve the marvelous sense of reality he did in KING KONG, a reality so intense as to make a thirteen-year-old named Raymond Harryhausen choose the field of special effects animation as his life’s work.

From the time he saw KING KONG in 1933, until the mid-40′s, the youthful Harryhausen animated in what might be called a highly animated fashion.

He even managed, on several occasions, to gain an audience with his future mentor. Though Ray’s fledgling efforts were crude, O’Brien saw in them a promise of future greatness, and he was quick to offer constructive advice to his precocious- protege whenever he was asked. In 1946, impressed by Ray’s solo efforts in producing a series of animated fairy tales; O’Brien offered him encouragement of a more concrete nature: a position as an animator on the Merian C. Cooper production MIGHTY JOE YOUNG. Of this opportunity-of-a-lifetime Harryhausen recalls: “It was, of course, the climax of a long-awaited dream come true. I had a magnificent two-year period of working with O’Brien, during the long pre-production and design stage, up to the end of animation photography. He was so involved in production problems that I ended up animating aboul 80% of the picture.”

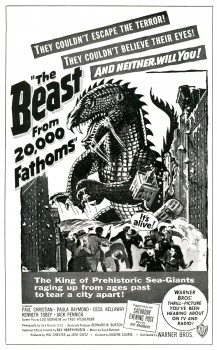

In 1952, as a result of his Oscar-winning work on MIGHTY JOE YOUNG (Best Special Effects of 1949) Ray was approached by Jack Dietz and asked to create the effects for THE BEAST FROM 20,000 FATHOMS. These he executed ably, employing an innovative front-projection system of his own design, as the preferable but more expensive rear-project ion equipment the work called for was outside the boundaries of Dietz’s budget. THE BEAST came in at $200,000, a remarkably low figure considering the expertise and high quality of Ray’s animation and effects. Audiences of 1952 flocked to the picture in droves, making it the unexpected sleeper of the year for Warner Brothers. Completing THE BEAST left Ray on the brink of a long, creatively satisfying and financially rewarding association with a then-youthful producer, Charles Schneer.

In 1952, as a result of his Oscar-winning work on MIGHTY JOE YOUNG (Best Special Effects of 1949) Ray was approached by Jack Dietz and asked to create the effects for THE BEAST FROM 20,000 FATHOMS. These he executed ably, employing an innovative front-projection system of his own design, as the preferable but more expensive rear-project ion equipment the work called for was outside the boundaries of Dietz’s budget. THE BEAST came in at $200,000, a remarkably low figure considering the expertise and high quality of Ray’s animation and effects. Audiences of 1952 flocked to the picture in droves, making it the unexpected sleeper of the year for Warner Brothers. Completing THE BEAST left Ray on the brink of a long, creatively satisfying and financially rewarding association with a then-youthful producer, Charles Schneer.

Schneer wished to produce a script about a giant octopus that terrorizes San Francisco, and after meeting hirn^ {Schneer, not the octopus) Ray agreed to work on the picture. The result was IT CAME FROM BENEATH THE SEA, the first of a series of ten feature films produced by Schneer with special visual effects by Ray Harryhausen. Along the way, Ray has freelanced twice: once in 1958 to animate the dinosaur sequences in Irwin Allen’s THE ANIMAL WORLD, and again in 1966 to handle effects on Hammer Film’s OWE MILLION YEARS B.C.

A comparison of the work of Ray Harryhausen and Willis O’Brien yields some interesting observations. One of O’Briens trademarks throughout, his career was his use of glass paintings. The three-dimensional effect of the jungles of Skull Island was achieved through the painting, on glass, of dense trees and vines. By animating his models behind several layers of these realistic depictions of forest, O’Brien was able to achieve an illusion of depth that added tremendously to the dramatic impact of the entire film. O’Brien was a dramatic romantic, and a stickler for any detail •haqlbuld romanticize. Harryhausen, on •hefOtner hand, is a realist, and in his Jiifork there is a sense of reserve; of a wpjehful eye on the cost of each particular effect. No layers of intricate glass paintings for him—too expensive. For Ray’s purposes a simple but effective matte painting will suffice. The net result is always a little less atmospheric than O’Brien’s work and ultimately less powerful. To compensate for this Harryhausen outshines his master in the fluidity of his animation. His smoothness of movement of his foam rubber creatures is the most striking difference between his and O’Brien’s digital prestidigitation. In this area the pupil could have taught his teacher.

A comparison of the work of Ray Harryhausen and Willis O’Brien yields some interesting observations. One of O’Briens trademarks throughout, his career was his use of glass paintings. The three-dimensional effect of the jungles of Skull Island was achieved through the painting, on glass, of dense trees and vines. By animating his models behind several layers of these realistic depictions of forest, O’Brien was able to achieve an illusion of depth that added tremendously to the dramatic impact of the entire film. O’Brien was a dramatic romantic, and a stickler for any detail •haqlbuld romanticize. Harryhausen, on •hefOtner hand, is a realist, and in his Jiifork there is a sense of reserve; of a wpjehful eye on the cost of each particular effect. No layers of intricate glass paintings for him—too expensive. For Ray’s purposes a simple but effective matte painting will suffice. The net result is always a little less atmospheric than O’Brien’s work and ultimately less powerful. To compensate for this Harryhausen outshines his master in the fluidity of his animation. His smoothness of movement of his foam rubber creatures is the most striking difference between his and O’Brien’s digital prestidigitation. In this area the pupil could have taught his teacher.

The exact processes by which Harryhausen combines his animated models with live actors are ones he prefers to anyone with a basic of animation can grasp the*1 rudiments of what Schneer and Harryhausen have dubbed “Dynarama.” Let us take an example from Harry-hausen’s latest film, THE GOLDEN VOYAGE OF SINBAD. The script called for a battle between Sinbad and a giant one-eyed centaur. The first step in creating the illusion of a human dueling with a mythical monster was to film the actor, in this case John Philip Law, leaping to and fro fighting with an imaginary creature. The resulting footage is loaded onto a rear-screen projector which has been modified to move a frame at a time instead of at sound speed. In front of this rear screen, Harryhausen constructs a miniature set, which corresponds to the full-size one on the film in the projector. Placing his foot-and-a-half tall centaur into this miniature setting, Harryhausen animates it a frame at a time, being careful to similarly advance the rear-projected image of Sinbad. Re-photographing this entire set-up with a locked down animation camera produces the desired effect. This description can only serve to illustrate the bare bones of the Dynarama process. Many sequences have required much more complex techniques of Ray and his equipment. As a result the time element involved in the production of a Dynarama picture is staggering. Pre-production lasts six months to a year. Principal photography lasts several months and the animation photography consumes an incredible year or more! But the results, which speak for themselves, have always seemed to justify the commitment of two or three years of Ray Harryhausen’s life; at least in the past they have.

The exact processes by which Harryhausen combines his animated models with live actors are ones he prefers to anyone with a basic of animation can grasp the*1 rudiments of what Schneer and Harryhausen have dubbed “Dynarama.” Let us take an example from Harry-hausen’s latest film, THE GOLDEN VOYAGE OF SINBAD. The script called for a battle between Sinbad and a giant one-eyed centaur. The first step in creating the illusion of a human dueling with a mythical monster was to film the actor, in this case John Philip Law, leaping to and fro fighting with an imaginary creature. The resulting footage is loaded onto a rear-screen projector which has been modified to move a frame at a time instead of at sound speed. In front of this rear screen, Harryhausen constructs a miniature set, which corresponds to the full-size one on the film in the projector. Placing his foot-and-a-half tall centaur into this miniature setting, Harryhausen animates it a frame at a time, being careful to similarly advance the rear-projected image of Sinbad. Re-photographing this entire set-up with a locked down animation camera produces the desired effect. This description can only serve to illustrate the bare bones of the Dynarama process. Many sequences have required much more complex techniques of Ray and his equipment. As a result the time element involved in the production of a Dynarama picture is staggering. Pre-production lasts six months to a year. Principal photography lasts several months and the animation photography consumes an incredible year or more! But the results, which speak for themselves, have always seemed to justify the commitment of two or three years of Ray Harryhausen’s life; at least in the past they have.

At present Ray is involved in yet a third film about the adventures of the swashbuckling Sinbad, though he characteristically refuses to give details about the project. This is understandable, since at the time we spoke he didn’t even have a story-line. This, too, is characteristic; perhaps unfortunately so. For it is in this area, the script, that Ray’s films have shown their vulnerable underbellies. Starting as they do with Ray’s sketches of the fantastic monsters involved, most Dynarama films are built around a monster or monsters on the loose. Plot, dialogue and characterization have always played second fiddle to special effects in Harryhausen’s films, and this is nowhere as painfully obvious as in THE GOLDEN VOYAGE OF SINBAD. Although his cart-before-the-horse method of scripting has always netted Harryhausen films of a very satisfying financial nature, it has never netted him a film with the impact and scope of KING KONG, and never will. One can only hope that as he has more say in his productions than any effects animator on earth, (he is a co-producer) Harryhausen will one day put as much creative energy into his script, casting and choice of director, as he does into his visuals. Perhaps then the day may yet come when Dynarama films will have some saving graces beyond their impressive opticals. Be that as it may, for anyone at all interested in animation and effects cinematography, the words of the grandmaster of Dynarama paint a fascinating portrait of a seldom glimpsed phase of film production.

At present Ray is involved in yet a third film about the adventures of the swashbuckling Sinbad, though he characteristically refuses to give details about the project. This is understandable, since at the time we spoke he didn’t even have a story-line. This, too, is characteristic; perhaps unfortunately so. For it is in this area, the script, that Ray’s films have shown their vulnerable underbellies. Starting as they do with Ray’s sketches of the fantastic monsters involved, most Dynarama films are built around a monster or monsters on the loose. Plot, dialogue and characterization have always played second fiddle to special effects in Harryhausen’s films, and this is nowhere as painfully obvious as in THE GOLDEN VOYAGE OF SINBAD. Although his cart-before-the-horse method of scripting has always netted Harryhausen films of a very satisfying financial nature, it has never netted him a film with the impact and scope of KING KONG, and never will. One can only hope that as he has more say in his productions than any effects animator on earth, (he is a co-producer) Harryhausen will one day put as much creative energy into his script, casting and choice of director, as he does into his visuals. Perhaps then the day may yet come when Dynarama films will have some saving graces beyond their impressive opticals. Be that as it may, for anyone at all interested in animation and effects cinematography, the words of the grandmaster of Dynarama paint a fascinating portrait of a seldom glimpsed phase of film production.

M.C.: Have you ever considered remaking the film which first inspired you, KING KONG?

R.H.: Yes, but KONG couldn’t be re-made today without spending vast amounts of money. The time and cost involved in doing all those glass paintings would be astronomical. You know O’Brien really developed the technique of glass painting single-handedly. In a way his use of them was a forerunner of Disney’s multi-plane camera. On KONG Obie had animation tables sandwiched between the glass paintings, and on these tables he’d place his models. He needed a tremendous amount of light for the camera to record through all those panes of glass. Often a light would blow in the middle of a scene, ruining a shot he had worked on for days. To remake KONG would be much too complex a thing to get into today.

M.C.: Some hold the opinion that your films have little merit aside from their impressive effects. I don’t mean to criticize, but I tend to agree with that, excepting MYSTERIOUS ISLAND, a Him I feel could stand alone if the footage of the monsters was cut.

R.H.: Really? I don’t think you would feel that way about MYSTERIOUS ISLAND if you actually did cut that footage. Pick up an 8mm version some time and try it. (Laughs) The original Jules Verne novel was really just a tale of survival on a desert island. The survivors in the story saw rather mundane things, so we modified their adventures a bit by adding Capt. Nemo and his giant creatures.

M.C.: With newer and better emulsions now available in 16mm, have you considered working in that gauge?

M.C.: With newer and better emulsions now available in 16mm, have you considered working in that gauge?

R.H.: No, I have no reason to work in 16mm. With 16 you don’t have the options and accuracy of 35mm and the optical printer. Certain subjects might show up quite well on a blow-up from 16, but my work is much too complicated to further complicate it by working in a smaller gauge than 35mm.

M.C.: What about 70mm?

R.H.: We released FIRST MEN IN THE MOON in 70mm, but that was a blow-up from 35. Shooting on a 70mm negative is too costly a proposition, necessitating the use of too many specialized pieces of equipment.

M.C.: FIRST MEN was shot in Panavision. What effect did shooting wide screen have on your usual methods?

R.H.: I was forced to re-design many things, because certain techniques are impractical in Panavision. I relied more heavily on traveling matte work in FIRST MEN, whereas normally I might have used front or rear projection.

M.C.: you are quite active in other areas of production besides animation photography. Have you ever considered directing an entire film?

R.H.: Oh, yes, I would very much like to direct if I find the right subject. But it’s a big job just to keep track of the special effects. There’s a limit to how much one man can do.

M.C.: Didn’t you once remark that you were unhappy with the animation of the miniature horse in THE VALLEY OF GWANGI? If so, why?

R.H.: No, what I did say was that it was a sequence I ‘dreaded doing because the horse really didn’t have anything dynamic to do. It just had to sit there and look coy. It’s always difficult to decide what to have the creature do in scenes like that. An action sequence involving a giant animal is much more impressive. So I let that scene go until last.

M.C.: Box-office-wise your films have usually done quite well. How can you account for the relative failure of THE VALLEY OF GWANGI?

R.H.: It was released at a time when Warners was being sold and it received very poor distribution. There was no advertising to speak of and nobody knew what the picture was about.

M.C.: Alternately, THE GOLDEN VOYAGE OF SINBAD has really hit big with audiences here.

R.H.: You must remember the time when GWANGI was released. Everyone was on a sex binge then, and we only had sexy dinosaurs. Warners didn’t push the picture at all. Columbia, on the other hand, has put a great deal of effort into their campaign for GOLDEN VOYAGE. That and word-of-mouth really paid off.

M.C.: In the past you have utilized the talents of film composer Bernard Herrmann for your scores. Why was he not used on GOLDEN VOYAGE?

R.H.: There were many reasons. Sometimes people are tied up, and sometimes the situation just isn’t conducive to getting the people you would prefer. I think the composer we did use, Miklos Rozsa [SPELLBOUND], writes a different kind of music than Herrmann, and that he did a very good job for us.

R.H.: There were many reasons. Sometimes people are tied up, and sometimes the situation just isn’t conducive to getting the people you would prefer. I think the composer we did use, Miklos Rozsa [SPELLBOUND], writes a different kind of music than Herrmann, and that he did a very good job for us.

M.C.: Taking his past efforts into account, why was Gordon (THE OBLONG BOX) Messier chosen to direct GOLDEN VOYAGE?

R.H.: Again, there were many reasons, and I can’t go into them here. I think Hessler has a very good sense of direction. You must remember that the quality of each picture a director works on depends largely on how much money is in the budget. Some people think we have carte blanche to make a picture any way we please. Except for a David Lean or a Stanley Kubrick, this is not the case. We make a commercial product, and though there are many things we might like to do on a picture, it always comes down to whether or not the money is there.

M.C.: All told, how long were you at work on the effects for GOLDEN VOYAGE?

R.H.: About a year. All the work was done here in London at Gold Hock Studios.

M.C.: Did British Museum sculptor Arthur Hayward assist you in constructing the animation models, as he had on ONE MILLION YEARS B.C. and GWANGI?

R.H.: No, I had others assist me. Molding and casting are very time-consuming jobs, so I farm some of it out to certain individual. I can’t do all the models myself, because I don’t have the time.

M.C.: Do you paint your own matte paintings?

M.C.: Do you paint your own matte paintings?

R.H.: No, I don’t. In fact nowadays I try to avoid using them. There are very few people who can do them well enough so that you don’t have to cut away from them right away. Today it’s practically a lost art, unfortunately. Most of the ones in my other films were done by staff matte painters at Shepperton Studios.

M.C.: I found there was quite a bit of grain in GOLDEN VOYAGE. Why was this?

R.H.: We worked with dupes quite a lot. There are shots in the film where you’re looking at a third-generation dupe, so naturally there’s an increase in grain. Another reason you might have spotted some excess grain was because we printed several optical zones and dolly shots on the printer.

M.C.: What can you tell me about your next film project?

R.H.: It’s called SINBAD AT THE WORLD’S END, and that’s about all I can say. We have a formal company which releases information to the public, and at the moment I’m not at liberty to say anything more. Does that pacify you? (Laughs)

M.C.: Not really. Will John Philip Law again play Sinbad?

R.H.: That depends on his availability, and the characterization in the script, which we don’t even have yet. There have been several Sinbads—Douglas Fairbanks, Kerwin Mathews, Guy Williams. We would like to give him a different quality each time. The irony is that when you knock yourself out to make a picture different, the critics chastise you for not putting in the expected cliches. One reviewer said of GOLDEN VOYAGE that he missed the dancing girls. Now that is a typical Arabian Nights cliche that we avoided on purpose.

M.C.: I have one final question concerning THE SEVENTH VOYAGE OF SINBAD. There is a sequence in that film which depicts Sinbad’s crew walking up the beach loaded down with fruit. There is a black man in the crew, and he’s carrying a watermelon.

R.H.: Oh no…(torrents of laughter at this) only a member of today’s generation would notice something like that. I assure you it was all accidental as to who got what prop.

Thus satisfied that THE 7th VOYAGE OF SINBAD contained no racist undertones, I bid Mr. Harryhausen a fond farewell, leaving his Kensington High Street home for the bleak and foggy streets of London. As I ambled towards the nearest Underground I gave additional thought to the question of Mr. Harryhausen’s responsibility for the over-all quality of his films. Approached on an adult level they are rather silly entertainments. But for a child they create a vivid fantasy world where skeletons come to life and fire-breathing dragons battle with cyclops. I was a child once, and the marvels of Harryhausens monsters, both mythic and imaginary, overwhelmed me. There is a definite place in cinema for this type of film. The adult critical eye must squint a bit to watch THE GOLDEN VOYAGE OF SINBAD, but if that’s not enough, one can always leave the theatre to the little people, whose eyes Ray Harryhausen’s films are created for.

Daily post 21 Jun 2008 08:21 am

Hopping Skipping & Jumping

- Thursday night I went to the Academy screening of Get Smart (which turned out to be a zero of a movie. I should have expected that despite the J. Hoberman/Village Voice rave.) There was another film playing that evening, Brick Lane, a small British movie about an Indian woman who is sent to England at age 17 to marry a cousin she has never met.

- Thursday night I went to the Academy screening of Get Smart (which turned out to be a zero of a movie. I should have expected that despite the J. Hoberman/Village Voice rave.) There was another film playing that evening, Brick Lane, a small British movie about an Indian woman who is sent to England at age 17 to marry a cousin she has never met.

That short synopsis was all I knew about the film. Rotten Tomatoes gave it a 63% on the “tomatometer,” and I expected something small and hoped for the best. I was in the mood.

The film turned out to be great. The music by Jocelyn Pook virtually lifted this film to one of the best films of the year. It’s excellent, and I thought I should tell you all to look out for it. If you’re thinking of going to Get Smart, don’t. Go to see Brick Lane, if it’s available near you. If it isn’t, keep the film in mind for the future. There’s real poetry and heartbreak there, and it’s a fine film.

I’ll get to see Wall-E next Tuesday and will probably comment on it afterward.

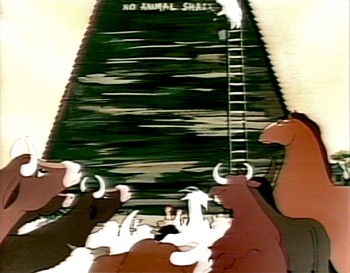

- I don’t have to repeat myself. I like Animal Farm a lot. That’s why I like to visit Chris Rushworth‘s excellent site, animalfarmworld.

- I don’t have to repeat myself. I like Animal Farm a lot. That’s why I like to visit Chris Rushworth‘s excellent site, animalfarmworld.

Chris regularly posts lots of images from his collection of artwork from this film, and continually adds to it. I amazed at the number of cels and drawings up on this site. He has recently added some new pages for links to other sites and posters.

I’ve added Animalfarmworld to my list o’ links.

– Almost as a companion piece, Thad Komorowski has complimented my posts of the storyboards for Alice In Wonderland. He’s posted David Hall’s boards for sequence 1 and sequence 2.

– Almost as a companion piece, Thad Komorowski has complimented my posts of the storyboards for Alice In Wonderland. He’s posted David Hall’s boards for sequence 1 and sequence 2.

This film, Alice In Wonderland, has generated a lot of beautiful artwork. David Hall’s boards are so illustration-like as compared to the energetic boards roughed out by Joe Rinaldi. (At least I think they’re Joe Rinaldi’s work.) Compare both to the amazing color styling of Mary Blair. (Check out Canemaker’s book, The Art and Flair of Mary Blair.

Note: after I post the third and final of the boards John Canemaker has loaned me I’ll post a bunch of Mary Blair images.

Lynda Barry has an interesting essay on “the power of the paintbrush” on the Tricycle archive. Read it. After you read that go out and get her new book, What It Is.

Lynda Barry has an interesting essay on “the power of the paintbrush” on the Tricycle archive. Read it. After you read that go out and get her new book, What It Is.

I was sent to the article via a link on Drawn. I learned of the book from Matt Clinton, a principal animator in my studio, who stood on line for a while to get Barry’s signature. She spoke at length to each of those on line, so there was a bit of a wait. She drew a cartoon for Matt, making it all worth waiting for.

Lynda also recently spoke at NYU as part of a symposium on the cultural importance of comics. Annulla tells the tale on her great blog, Blather from Brooklyn.

Daily post 27 Mar 2008 08:43 am

Singles

- I’ve become intrigued with websites devoted wholly to one film or studio. I’m not talking about studio paid sites that are designed to promote a film such as the Pixar sites or the Persepolis site (By the way, whatever happened to the English language version of this film? They recorded Sean Penn and Gena Rowlands acting the parts? Will it only be released as a dvd?)

I’m talking more of the sites established by fans or past employees who write about their collections and/or experiences.

Richard Williams‘ film, The Thief and the Cobbler has The Thief. This is a blog by four former artists who have worked on the film. Holger Leihe,

Richard Williams‘ film, The Thief and the Cobbler has The Thief. This is a blog by four former artists who have worked on the film. Holger Leihe,

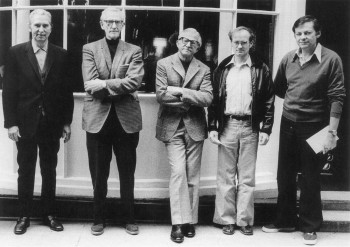

Dietmar Kremer, Andreas Wessel-Therhorn, and Michael Schlingmann have all animated on the film, and they all have lots to tell. It’s also open to others who have stories to share. Guests such as Producer, Carl Gover or cameraman, Brian Riley have contributed strong posts.___This photo of Ken Harris, Grim Natwick,

____________________________________Art Babbitt, Richard Purdum and Dick Williams

_____________________________________________comes from The Thief.

The end result is an informative site full of

interesting stories and technical details about this very complex movie. All of the animation seems to have created problems for its artists, and the stories on this blog really show how things were accomplished. From bipacking to static electricity to rotoscoping; technical achievements and problems are all detailed in a clear and entertaining way. It’s not only informative; it’s attractive, and it’s filled with photos and artwork that can’t be found elsewhere.

- Garrett Gilchrist has also devoted a lot of work in recreating this film to something close to Dick Williams’ original version. He’s taken the best quality copies of the rough cuts that were assembled – before they were taken away from Dick’s hands.

- Garrett Gilchrist has also devoted a lot of work in recreating this film to something close to Dick Williams’ original version. He’s taken the best quality copies of the rough cuts that were assembled – before they were taken away from Dick’s hands.

He’s posted a number of versions of this on YouTube and has an ongoing forum about the film. He recently posted The Little Island, an impossible-to-see film, on YouTube.

Garrett’s extensive and admirable reconstruction work on Dick’s films was probably the original inspiration for The Thief. I’d like to see a site by Garrett about Dick’s films.

- Chris Rushworth‘s site focuses on another British film, Animal Farm. The site, Animalfarmworld, is designed solely to feature some of the interesting cels and art that Mr. Rushworth has collected, and there’s quite a bit of it.

- Chris Rushworth‘s site focuses on another British film, Animal Farm. The site, Animalfarmworld, is designed solely to feature some of the interesting cels and art that Mr. Rushworth has collected, and there’s quite a bit of it.

Since March 25th, he’s added more than 100 drawings to the site including many of the handsome horse, Boxer.

Somehow the flavor of the pencil drawings, for the most part, seems to accurately depict the flavor of the film, itself. There’s something tentative about them. Even in the loosest of drawings the dynamism of some of the great Disney animators is missing. They are beautiful in their own right and feel as though they are from another time.

Daniel Thomas MacInnes is the proprietor of the excellent site, Conversations on Ghibli. This is a site, as its title would indicate, devoted to all things Ghibli, which of course is the studio that produces the films of Hayao Miyazaki. Daniel Thomas not only gives advance notices of the work in production, but he actually posts entire features done by Miyazaki. There are quite a few comments and discussions of lesser known films by this brilliant film maker.

Daniel Thomas MacInnes is the proprietor of the excellent site, Conversations on Ghibli. This is a site, as its title would indicate, devoted to all things Ghibli, which of course is the studio that produces the films of Hayao Miyazaki. Daniel Thomas not only gives advance notices of the work in production, but he actually posts entire features done by Miyazaki. There are quite a few comments and discussions of lesser known films by this brilliant film maker.

The site is quite a resource for all of us who are looking for information about the artist and his work. One would like more frequent posts, but that seems to be a problem with many of the best sites – you always want more. _______A still from the soundtrack of

____________________________________________Ponyo on the Cliff, an upcoming

_____________________________________________________Miyazaki film.

- Finally, let me change the subject. I’m overwhelmed by today’s post on Michael Barrier‘s site. There’s no greater example of pure history in its discovery. Mike hones in on the hiring of Rudy Ising at Disney’s Kay Cee studios in Kansas City, 1922. This is the premiere site out there for me. History is written and unique photos back it up.

Daily post 15 Mar 2008 08:21 am

New Directors & Gerry Potterton

- Emily Hubley‘s first feature film has made it into the New Directors:New Films series at MOMA in conjunction with the Lincoln Center Film Society.

The Toe Tactic is 2/3 live action and 1/3 animation. Emily directed both parts of the film and wrote it as well.

The Toe Tactic is 2/3 live action and 1/3 animation. Emily directed both parts of the film and wrote it as well.

The film’s stars include: John Sayles, Marian Seldes, Eli Wallach, Andrea Martin, and Mary Kay Place.

The short synopsis found on line is: In this hybrid of live-action and animation, a young woman grieves for her father while unaware of the magical world around her.

A review appeared in the Austin Chronicle when the film played as part of the South by Southwest Festival.

The film will play:

______Sat Mar 29: 6:00pm (Walter Reade Theater)

______Mon Mar 31: 9:00pm (MoMA)

- I was pleased to have received word that the great Gerald Potterton will be awarded the Pulcinella Lifetime Achievement Award from the 12th Annual Cartoons on the Bay International Festival of Television Animation in Salerno, Italy.

- I was pleased to have received word that the great Gerald Potterton will be awarded the Pulcinella Lifetime Achievement Award from the 12th Annual Cartoons on the Bay International Festival of Television Animation in Salerno, Italy.

The award is presented each year to “a prestigious personality of the world of cinema and television animation,” will be given to Gerry during the awards ceremony on April 12th. Previous recipients of the Lifetime Achievement Award include Italian animator Bruno Bozzetto, Roy E. Disney, and Bill Hanna & Joe Barbera.

I met Gerry on Raggedy Ann when I first started in a very big office with almost no one as yet hired. I spent a great Saturday with Gerry and Dick Williams coloring storyboard drawings mostly drawn by the brilliant Corny Cole. The drawings were being fed to, cameraman, Al Kouzel to shoot an animatic on 35mm film. It was a funny day, and I was in heaven working with Dick and Gerry for a solid Saturday.

I met Gerry on Raggedy Ann when I first started in a very big office with almost no one as yet hired. I spent a great Saturday with Gerry and Dick Williams coloring storyboard drawings mostly drawn by the brilliant Corny Cole. The drawings were being fed to, cameraman, Al Kouzel to shoot an animatic on 35mm film. It was a funny day, and I was in heaven working with Dick and Gerry for a solid Saturday.

Both Gerry and Dick were part of the Grasshopper Group in England back in the 50′s (along with the likes of Bob Godfrey, George Dunning and Stan Hayward. They’d known each other for quite some time and were close. I was the odd man out, but couldn’t have enjoyed the company more – with questions aplenty that I snuck in during the day.

During Raggedy Ann, I’d let Gerry know that I wanted desperately to see a film he’d done in 1969, Pinter People. This was a documentary about Harold Pinter and his characters,  showing the varied places that his characters inhabited: the parks, the pubs, the places. The films includes Pinter talking about these characters and includes five animated segments (about 45 mins of animation) from Pinter’s short plays. It is truly one of the first adult animated films built around words. Gerry brought me a 16mm copy to view, and I returned it immediately.

showing the varied places that his characters inhabited: the parks, the pubs, the places. The films includes Pinter talking about these characters and includes five animated segments (about 45 mins of animation) from Pinter’s short plays. It is truly one of the first adult animated films built around words. Gerry brought me a 16mm copy to view, and I returned it immediately.

I couldn’t be more pleased to see him receive this award, and I don’t think there is anyone more deserving. Congratulations, Gerry.

Here’s the part of the press release that was sent which includes Gerry’s bio, for those who are unfamiliar with Mr. Potterton’s distinguished career.

- Few Canadian film careers have been as colorful as that of British-born writer, director, producer and animator Gerald Potterton. In a career spanning over fifty years, he has worked on dozens of live action and animated films, including the classic British animated feature Animal Farm and the Beatles’ Yellow Submarine. He left the National Film Board to start up Potterton Productions, the largest film production house in Canada at the time, but he is best known as the director of the cult classic, Columbia Pictures release Heavy Metal, which was released in 1980. He directed the great American silent film comedian Buster Keaton in a National Film Board live-action short, The Railrodder, for which he was awarded a Buster for “film excellence in the Buster Keaton tradition” in 2002 at the annual Buster Keaton Celebration in Iola, Kansas.

In 1998, Potterton was selected as one of the “Ten Men Who Rocked the Animation World” at the first World Animation Celebration in Pasadena, California. His prolific career has been honored with retrospectives at North American film festivals from Ottawa to Seattle.

Daily post 04 Mar 2008 09:14 am

Missed events and AnimalFarmWorld

- A couple of events passed through New York in the last couple of days, and I’m sad to say that I missed them all. If anyone out there attended any of these, please feel free to let us know what you thought.

- A couple of events passed through New York in the last couple of days, and I’m sad to say that I missed them all. If anyone out there attended any of these, please feel free to let us know what you thought.

- Last night, there was a panel discussion at the Jewish Museum re the art of William Steig. Participating in this panel were:

- - Leonard Marcus who discussed Steig’s career as a

__ children’s book illustrator and author.

- Jeffrey Katzenberg, Chief Executive Officer of

__ DreamWorks Animation, discussed bringing the

__ character of Shrek to life on film.

- Chris Miller, director of the Shrek the Third film,

__ offered a movie director’s take on Shrek.

- Jason Moore, director of the forthcoming SHREK THE MUSICAL

- David Lindsay-Abaire, book and lyrics for SHREK THE MUSICAL, spoke about

__ the creative process that is driving the musical stage production.

Yesterday, there was a NYTimes article about Steig and the exhibit. It was obviously also in anticipation of the discussion.

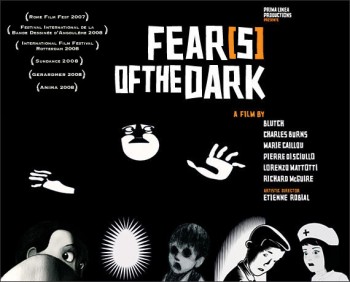

- On Saturday night, as part of the the “Rendez-Vous With French Cinema” – a short series of new French films playing at several venues aroung town – there was a single screening of Fear(s) of the Dark played at the IFC center.

- On Saturday night, as part of the the “Rendez-Vous With French Cinema” – a short series of new French films playing at several venues aroung town – there was a single screening of Fear(s) of the Dark played at the IFC center.

This is the animated feature directed by six different animators, including Charles Burns, Blutch, Marie Caillou and Richard McGuire. The film has been playing at a number of festivals recently, including Cinequest in San Jose, and Brussels’ Anima International Festival.

Fear(s) of the Dark was produced in France by Prima Linea Productions. Their site describes the film with a lot of stills (appropriately enough) and these words:

- Six of the worlds hottest graphic artists and cartoonists have breathed life into their

nightmares, bleeding away colour only to retain the starkness of light and the pitch black of shadows.

nightmares, bleeding away colour only to retain the starkness of light and the pitch black of shadows.Their intertwined stories make up an unprecedented epic where phobias, disgust and nightmares come to life and reveal Fear at its most naked and intense…

Variety reviewed the film positively at Sundance. They had glowing things to say about Richard McGuire‘s segment. I report this because McGuire, a New Yorker, introduced the film this past Saturday. It’s unfortunate that there was relatively little press about it, and that there was only the one screening. it conflicted with other plans I’d made, and I learned too late to alter my plans.

Postscript: Commentor Masako Kanayama left the information that the film will be screened again this Sunday March 9, at 1:30pm, at the Walter Reade Theater (Lincoln Center). You can buy advanced tickets online: www.filmlinc.com or at the box office.

- Something I have not missed lately is Chris Rushworth’s web site,

- Something I have not missed lately is Chris Rushworth’s web site,

Animal Farm World.

Chris is an ardent fan of the Halas and Batchelor feature, Animal Farm. As such he has collected quite a few drawings and cels from the 1955 feature. He also has many editions of the novel featuring work from different illustrators.

I first learned of this site when Chris responded to a post I’d written about the illustrations by Joy Batchelor for a tie-in edition of the book released in 1955. I’ve written more than a few pieces about this book and film to give you a good indication that I’m a fan as well.

Harvey Deneroff has an excellent article on his site about the history of the multiplane camera. He tries to track Willis O’Brien’s rear screen projection developments and the influence that may have had on the three studios that developed their cameras: Ub Iwerks, Max Fleischer or Disney.

Harvey Deneroff has an excellent article on his site about the history of the multiplane camera. He tries to track Willis O’Brien’s rear screen projection developments and the influence that may have had on the three studios that developed their cameras: Ub Iwerks, Max Fleischer or Disney.

He also details a bit about the multiplane setup developed by Lotte Reiniger utilized in producing Prince Achmed.

The connection between stop motion animation and the machinery is interesting. Given that both Iwerks and Fleischer used horizontal animation stands, it seems a natural that 3D animation was an obvious by product. Indeed, the little sets that Fleischer’s studio created are virtually 3D animation sets.

It’s a good article with excellent observations.

Lotte Reiniger pictured to the left.

Books &Frame Grabs &Illustration 25 Jan 2008 08:54 am

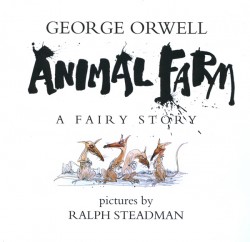

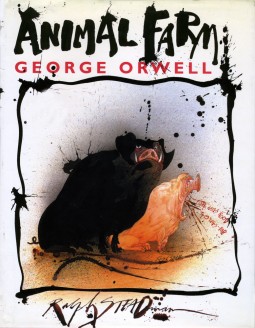

Steadman’s Animal Farm

- I saw Halas & Batchelor’s Animal Farm at a seminal point in my animation development, so I guess you could say I was struck over the head at just the right time. The same is true of Lady and the Tramp, Sleeping Beauty or Magoo’s Christmas Carol. They, and a number of other films from that period, have enormously affected how I see animated cartoons and what it is that I like. Somehow, I think I’ve mentioned this before.

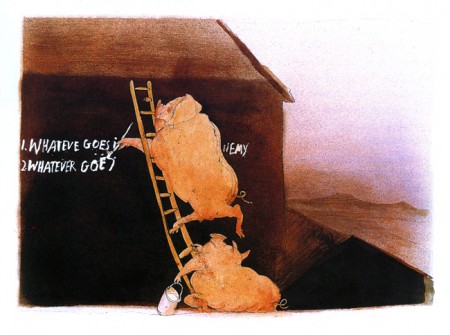

I am also a big fan of Ralph Steadman‘s work. For some inspiration, I was looking over his illustrations for Orwell’s book. The story vibrates in his hands. I thought it might be interesting to post some of these and find relative images from the film to see how they compare.

Make no bones about it, I think Steadman is as close to an artist an illustrator can become, and I have no similar thoughts about the artwork for the Halas & Batchelor film. I am interested, however, in how different people view images they get from the same text.

_ _

_

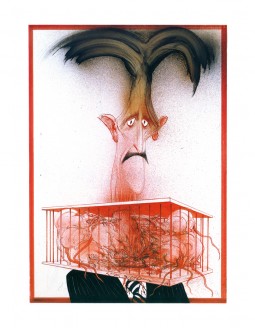

___On the left, we have the book’s dust jacket, cover. On the right, Steadman offers a

___caricature of George Orwell holding rats in a cage. A reference out of “1984.”

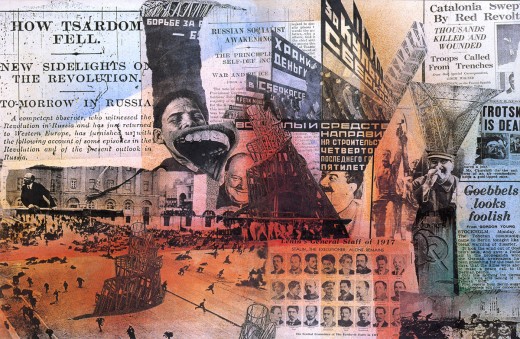

___The inner cover of the book’s front features this double page collage/painting by

___Steadman. Politics of Orwell’s time is put front and center.

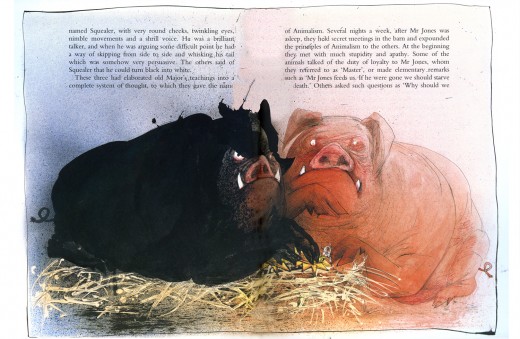

____Napoleon and Snowball closely align with each other and give each other support.

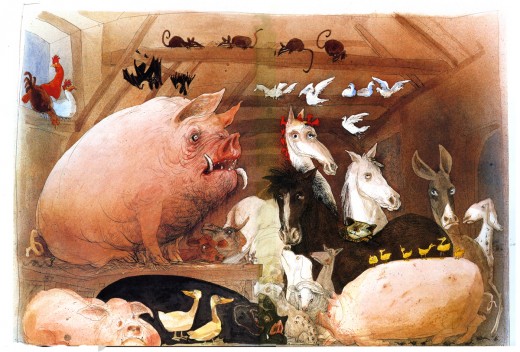

_______All the animals meet in the barn to create a plan. The pigs take the lead.