Category ArchiveArticles on Animation

Articles on Animation 17 Nov 2009 08:43 am

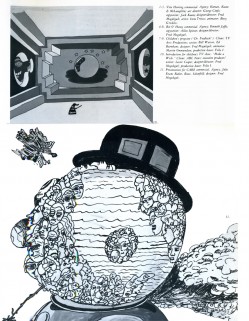

Norshtein 1980

- This article, written by Yurij Norstein, appeared in Animafilm 5, March 1980. How could I not reproduce it, since it appears nowhere else on line or in print, that I know of.

L’Art tout court

by Yuri Norstein

WHAT IS ANIMATION FOR ME? Just a field of art, I suppose. T don’t regard it as something separate, I don’t think it has its own laws different from those applying to art in general. Another thing is that being a new field of art, it is looked down upon by feature film, just as film itself was once looked down upon by the theatre. People often treat animated film as if it were something inferior, and underestimate its artistic possibilities and social significance.

WHAT IS ANIMATION FOR ME? Just a field of art, I suppose. T don’t regard it as something separate, I don’t think it has its own laws different from those applying to art in general. Another thing is that being a new field of art, it is looked down upon by feature film, just as film itself was once looked down upon by the theatre. People often treat animated film as if it were something inferior, and underestimate its artistic possibilities and social significance.

In my opinion the essence of art is not confined to the fact that it serves concrete purposes, such as providing emotional experience or entertainment. This does not mean that art does not perform these functions. It does. What Aristotle said still holds: art, above all teaches man to enjoy life.

But Leo Tolstoy, for instance, used to say that if he were commissioned to write a work on a clearly defined theme with a precisely stated social function, the writing would not take him more than two hours. He would add that he wrote mainly about people, about relations between people, in order to force the reader to laugh or cry, that he sought to release ordinary human reactions characteristic of life. His idea was that man should see in an artistic work everything he could perceive in life, out that this should be presented in the form of certain regularities. This means that life and art are different concepts; art always assumes objective significance, it becomes an historical phenomenon, while what we call ordinary life and the events taking place in it, do not have this character.

Of course I do not single out animated film as a field of art guided by its own principles. According to me its principles are exactly the same as those governing other fields of art; they are taken from life, but at the same time the collected material is subjected to some specific processing. This material consists of human emotions, joys, tears, love and everything that is contained in our life and that the artist turns into art.

NO, ANIMATION IS NOT THE ONLY FIELD OF MY ACTIVITY. As a matter of fact, I make drawings for animated films. I also practise painting, but I treat this as a purely personal affair. My attitude to animation is rather specific; it is determined by the neccessity of choice. This is not so much a matter of choosing content wirh a clearly defined plot or idea. It is something much more, for in my opinion an animated film does not merely express some idea.

NO, ANIMATION IS NOT THE ONLY FIELD OF MY ACTIVITY. As a matter of fact, I make drawings for animated films. I also practise painting, but I treat this as a purely personal affair. My attitude to animation is rather specific; it is determined by the neccessity of choice. This is not so much a matter of choosing content wirh a clearly defined plot or idea. It is something much more, for in my opinion an animated film does not merely express some idea.

An idea can be formulated in words; the means of expression used in the visual arts are not indispensable here. But there may be something more which I may find difficult to put into words and which perhaps is not necessary for me. I have in mind the ideas composed of concrete pictures, of the artistic context in which these pictures exist, of colours, tones, some kind of flora, words, music, all those devices which can create something that cannot he translated into a language of words, that cannot he formulated as a definite idea of a film.

Of course, the artist must have this idea in himself. However, this idea is much more general than the concrete idea existing in a film. This is how I understand art, and this is what animation means to me.

Of course, the artist must have this idea in himself. However, this idea is much more general than the concrete idea existing in a film. This is how I understand art, and this is what animation means to me.

I am not interested in films with a definite plot and do not want to make them. Why? Because a clearly formulated plot constitutes the deductive side of every film, a side followed attentively by every spectator. But if a film is reduced to the unequivocal content of its story, the content ceases to interest the public when they see it for the second or third time. I think that if a film is interesting, the spectator will always want to see it again, in order to follow not the plot itself but those elements that are connected with reality and have been expressed in a definite artistic language.

WHY DO I USE A TECHNIQUE that, in a way, makes my films different? I think this technique allows me to make wide use in animation of my artistic pursuits, for it combines animated puppets with animated cartoons.

Animated cartoons are a more dynamic art; animated puppets arc more static. Dynamism and inattention to the plot are alien to the latter owing to their very nature. Puppet animation is a much more philosophical art, I think. But at the same time it lacks the flexibility characteristic df animated cartoons; it does not give the artist the same freedom of handling figures and objects.

So my technique combines the good and bad sides of animated cartoons and puppets, and this can be reflected in various ways. The point is that in spite of everything, this allows me to subordinate the entire artistic background created for the needs of films to my inner ideas, to my artistic credo.

ARE THE POETIC NATURE OF THE PLOTS OF MY FILMS and their poetic form a result of my interest in painting? Yes, to some extent they are. I think that every animated film director is always interested in painting or in the fine arts in general. This is only natural. After all, an animated film has a dual nature. An artist creates a new original artistic background in which I, as a director, must create a definite dramatic action. Hence the dual character of animated films, and the difficulty of creating the proper artistic background. The spectator

ARE THE POETIC NATURE OF THE PLOTS OF MY FILMS and their poetic form a result of my interest in painting? Yes, to some extent they are. I think that every animated film director is always interested in painting or in the fine arts in general. This is only natural. After all, an animated film has a dual nature. An artist creates a new original artistic background in which I, as a director, must create a definite dramatic action. Hence the dual character of animated films, and the difficulty of creating the proper artistic background. The spectator  should adapt himself to this background, penetrate it, and participate in the film on terms dictated by the subject.

should adapt himself to this background, penetrate it, and participate in the film on terms dictated by the subject.

THE STYLE OF MY FILMS, THE WAY THEY COMBINE JOYS AND SORROWS, their light character? I think this is necessary in animation. After all, it is important to awaken something in the spectator, something that will remain in his soul, something he will want to return to. I wouldn’t like to make films that influence the public only by their physiology.

I have in mind overabundance of artistic elements or shocking, unusual scenes. The picture of a killed child will always move the public, but this is not necessarily an artistic experience. An artistic experience occurs when a film contains definite mutual relations perceived by the spectator, relations which make him think. The same scene with a killed child will then make a different impact.

In my work I seek to combine all the elements of an animated film into one absolute whole: the settings the background and figures and assembly.

IS AN ANIMATED FILM LESS determined by technical limitations than other kinds of film? On the whole, animated films arc all the better for technical limitations. To begin with, technical limitations make the artist consider the conditions dictated by the fact that he is making an animated film.

Besides, I think that both objective and deliberate, conscious limitations are necessary in animated films. 1 cannot express opinions about other kinds of films. I take no part in their making and I am only a spectator. But if we arc to compare them, my opinion is that is good for one kind of art is not good for another. And I don’t think one can say that one kind of work in film is less important or less difficult than another.

In an animated film the material itself may create greater possibilities. In a feature film with actors the shifting of a machine to where the director wants it to be may be very difficult. But the entire background is already there; it exists in its basic forms. In an animated film everything must be created from the very foundations; one has to choose, to find all the necessary elements, the best ones. This is just as complicated as the shifting of a machine in a feature film. As in art in general.

WHAT KIND OF SPECTATOR DO I HAVh IN MIND DURING MY WORK? This will sound like a paradox but I think mainly about myself. This may sound cynical. For me, however, this is the most objective evaluation of what I am doing. If I thought, let us say, about crowds of spectators, I wouldn’t be able to take the tastes of each of them into consideration. And if I assumed my film was meant for an artistic elite, sensitive to all artistic innovations, things would be very much the same. Especially as the elite may be wrong too, in fact it is often wrong because it is sensitive to the creative side and may not perceive the rest.

So when making a film I think of myself, of how I will receive it, whether it is simple and understandable. There is a certain danger here, for I move within my film all the time, so it may seem understandable to me without really being so.

Undoubtedly, this is not the most objective way of finding out whether I can reach the spectator or not. Nevertheless, I think that this approach to creative work allows me to come nearer the absolute which exists in my imagination. Another thing is that when I am working on a film I tell my friends what I am doing and watch their reactions. And this is often helpful as it allows me to see whether the effects I achieve arouse interest or bore people. I take these reactions into consideration, change certain things, have yet another look at some fragments. However, when I am absolutely convinced I am right, I do not change anything, even if I notice a lack of interest in my ideas during a conversations, I am inclined to admit that I may have made a mistake. Now and again, very often in fact, T talk with my children, relate various episodes to them, watch their reactions and draw conclusions.

I think that films for children can only be made by an artist who understands children. If he can play with three- or five-year olds, it means he can look at the world through their eyes and can make films for them.

THE FUTURE OF ANIMATION? I see it in rather dark colours. I cannot say whether this is connected with limitation of a technical nature or the crisis of the animated film in general. Each of us goes through some critical moments, especially when we have achieved something and feel that further work will be just a repetition. We then begin to look for something completely new, we find some analogies with literature and feel that this is what we want; but at the same time we feel that we cannot express this, that not everything has been fully grasped. These are very difficult moments, especially when one sets to make photographs and the doubts have not been removed yet. Such a crisis can be overcome all of a sudden, under the influence of something quite unimportant. But before this happens there is a lot logo through.

DRAMATURGY IN ANIMATED FILMS. In my opinion the present principles of dramaturgy in  animated films are wrong because they are the same as those in feature films with actors. Disney somehow managed to cope with it but not because he set himself high moral requirements but because at every moment he was in full control over every detail. Literature, which is now a kind of basic art, reaches the reader slowly and a bridge is a piece of metal difficult to be engraved upon but once this has been done, it lasts for a long time. Literature is similar in this respect and film cannot compete with it. A film does not usually remain long in human memory, and it seldom exerts an influence on people’s attitude to life, etc. There have been exceptions, hut they have been few.

animated films are wrong because they are the same as those in feature films with actors. Disney somehow managed to cope with it but not because he set himself high moral requirements but because at every moment he was in full control over every detail. Literature, which is now a kind of basic art, reaches the reader slowly and a bridge is a piece of metal difficult to be engraved upon but once this has been done, it lasts for a long time. Literature is similar in this respect and film cannot compete with it. A film does not usually remain long in human memory, and it seldom exerts an influence on people’s attitude to life, etc. There have been exceptions, hut they have been few.

The reason why I say this is that the principles of dramaturgy, especially in feature length animated film, have been transferred unchanged from ordinary films. This is wrong in my opinion. An animated film sould make use of all the means which an artist can create in his studio. In Chaplin’s films everything is contained in his acting. One gesture comprises elements of various genres: from the fantastic to absolute realism and even atavism.

An animated film is by its very nature an art composed of various genres. It contains myth, fantasy, cosmogonic ideas, absolute realism, and even naturalism or mysticism. I think that the combination of all these elements could contribute a lot to the animated film, especially feature-length film. But I have never seen such a film. Not yet. All I see are films with a plot which could just as well be played by an actor.

Painting is developing in various directions while the animated film seems to be at a standstill; it does not show dynamism in development. It lacks something; it seems to be confined to one genre. I think that a study of literature, especially ancient literature, which combines various genres, including the Bible, which contains practically all elements from comic to tragic ones, that is, the entire richness of human life, would be of great benefit for animated films, especially feature-length ones. I think that a feature-length animated film should not just tell a story. It should present the richness of human life and, making use of the specific properties of animation, look for its own ways of development.

Recorded by Mieczyslaw Walasek

YURI NORSTEIN: FILMOGRAPHY

1968: 25th – THE FIRST DAY

1971: THE BATTLE OF KERSHENZ (prizes: Zagreb, Tbilisi)

1973: THE FOX AND THE HARE (prizes: Baku, Zagreb)

1974: THE HERON AND THE CRANE (Kischinjow, Annecy. New York, Teheran, Tampere, Melbourne)

1975: THE HEDGE-HOG IN THE FOG (prizes: Frunse, Karlove Vary, Melbourne, Gijon)

1979: THE TALE OF TALES (prizes: Ashabad, Lille, Obcrhauscn).

Illustrations:

1. Norstein (1980)

2. The Heron and the Crane (1975)

3. The Heron and the Crane

4. The Hedge-Hog In the Fog (1979)

5. The Hedge-Hog In the Fog

6. The Hedge-Hog In the Fog

Articles on Animation 06 Nov 2009 08:41 am

Ed Benedict – Animafilm Intvw

- Amid Amidi in Animation Blast #8 printed a brilliant interview with Ed Benedict. There was another interview in the European magazine Animafilm 6, 1980. It was written by Dana B. Larrabee.

Ed Benedict on Animation

We have often dealt in our journal with the prospects of computer animation. We believe that also the views of an advocate of the traditional methods of animated film deserve popularization.

Ed Benedict first spoke to me on the telephone about an animated tv spot I had done for a local car dealer. When 1 learned of his extensive hack-ground in animation, I asked it” we might meet and talk further. Shortly thereafter we met twice at his home in Carmel, California.

Ed Benedict first spoke to me on the telephone about an animated tv spot I had done for a local car dealer. When 1 learned of his extensive hack-ground in animation, I asked it” we might meet and talk further. Shortly thereafter we met twice at his home in Carmel, California.

We talked mostly of the views Ed has developed during his forty-plus years in the animation business. From those interviews I have assembled the following for those interested in a personal ac-count of the craft and business of animated filmmaking as it has evolved in the United States.

It wasn’t a business. It was a group of guys that had to organize themselves for eight hours of the day basically.

In 1930 Ed went to work for the Walt Disney Studios as an apprentice inbetweener. The Mouse was an established cartoon character then, and Walt trying to launch a new kind of cartoon series that did not feature a regular character. These were the “Silly Symphonies”.

Ed recalled: – When I first worked at Disney’s (show you how thorough that guy was), we were required to make our own little animation tests. This is when we were just assistants. We’re not animators yet. I did a horrifying job when I think of it now, of a guy taking a horn and blowing it. That sounds pretty damn simple . . . and it could look like it too. And you could do it and it would look like, “Oh, brother! Is that keen!” A guy big, full of air: then blowing out, turns thin, you know. No animation. Just going from A to B. But we had to do it our own way. Start with nothing. No instructions. Just a blank piece of paper, and how many drawings we took to do it, that was our own thing.

We had to take all of our test papers in to the test-camera which was a little Tinker Toy baling wire rigged-up thing. This was at the first studio on Hyperion. He wasn’t making cameramen out of us. He was just rubbing our noses in the business.

So you got kind of an overview – I interjected.

So you got kind of an overview – I interjected.

Yes. An appreciation for every department. Then the cameraman would take it out and develop it – and not print it. We’d just look at the negative on the Moviola. We would get our strip of film and that was it. At the end of the day Walt would come around and look at it with us and just go over it.

There was one of the early “Silly Symphonies ” called “The China Plate” (1931) when I was assistant to Rudy Zamora. One of the scenes was trucking in on one of these plates with Chinese scenes painted on it. Rudy had this scene and he was quite delighted to have thought to do this himself; I remember him leaning over to me, flipping the animated drawings saying: “Hey, how do you like this?”

You know these little Chinese girls with the little Chinese bobs? Straight bobs. Whether they ever had them or not, I don’t know. That’s the way we thought of them at the time. This little girl was to turn from left to right – but when she turned, the hair trailed across her face. That had never been done before. That’s a first beginning to loosen up things. Not only animating the figure from here to herc~but there’s little things on them too, where a thing will trail an action and then come back again and then settle down. It was just sort of lifelike.

He also worked under Wilfred Jackson {who had previously been an assistant to Ub Iwerks) doing breakdown, clean-up and inbetweening.

I’d been there a couple of months and we were working on this picture that had an Indian character ot a fox fighting with another character. I noticed that in this particular scene the fox’ tail was missing. When I remarked on it to Jackson, he said there was so much action that no one would miss it. I guess you could say that was my first experience with the “facts of life”.

He chuckled and continued: – Jackson was to later become a first class triple-plus director . . . and he was the last guy in the place that looked like it. A wonderful guy . . . straight . . . and he didn’t appear to have a sense of humor. He just didn’t look like he belonged in that business. But I guess he was the first genius of the directing end who knew to get the “Disney” out of the Disney Product.

In 1933 Benedict went to work for Walter Lantz at Universal as an assistant animator. Then he worked for Charles Mintz at Columbia for a year-and-one-half before returning to Universal where he became a full fledged animator. It look an average of four years to make animator, Ed recalls.

Then on the side with a co-worker at Lantz’, he set up an independent company. They first tried to interest Richfield Oil in the idea of animated billboards – a project Ed describes as “successfully unsuccessful”. Then he hit on the notion of selling commercial ideas to independent theatres. But without a distribution set-up, the idea “took a long time to develop into a state of nothing”.

From 1938 Ed worked with Paul J. Fennel at Cartoon Films, Limited making commercials for Borden’s, Shell Oil, Rinso, etc. He returned to the Disney organization in 1942.

Did you work on “Willie, the Operatic Whale”? I asked.

Yeah. I worked with Ken O’Connor on that. An excellent artist.

Ed went on to explain about the drawing materials used by the animators.

The paper that everybody used to use was called Management Bond.

What kind of ink did they use on the cells? I asked.

I can tell you back then it was India. And there were Gillot pens and there were other kinds of pens for certain widths. And then they started getting these spread lines and working with brush. The girls had to be pretty sharp with a brush. You couldn’t just take any girl, like with a pen. A girl had to be trained with a pen for tracing before she’d get into brush. Ed was kept busy at Disney’s doing “war stuff”. He worked on an aerology series for the Navy and Victory Through Air Power as well as educational films. This period of employment with the Disney organization lasted three years. After the war, he took a leave of absence to help Paul Fennel found his own cartoon studio.

About this time United Productions of America, better known as U.P.A. was getting under way.

Now U.P.A. was my idol. U.P.A. was the greatest – Ed enthused. Steve Bosustow was living down in Santa Monica on the beach and one time I visited with him. And in one of the rooms on the wall was a bunch of story sketches that he wanted to show me, things they were working on. They were a little weird-ish compared with the typical bulb-headed looking things. They were attractive and intruiguing. And that was the beginning of U.P.A.

It was later taken over by a different outfit – made a garbage can out of it. Like the Dusenberg. gone. Period. End. Fin.

Later Ed called Tex Avery at M.G.M. (whom he knew from his days at Universal) and asked him if he needed a layout man. In animation “layout” refers to the design and relation of the cartoon characters to the backgrounds and to the total visual concept of the film as a whole.

Ed explained: – You see when I left Universal I was an animator. But with Paul I was laying out and doing the models – everything. So I got away from animation – animation bored me. I don’t know. I wasn’t a good animator. But my inclination ran towards more drawing. So laying out and models got to be my thing from then on.

By models, do you mean model sheets? For the characters?

Not model sheets – models. Just a drawing of the one character . . . and overall three-quarter thing showing what it’s all about. Model sheets are based on models.

The model sheets are referred to by the animators as they work on their scenes. They show the characters in multiple views, different poses, expressions, etc., and their proportion to other characters they may be working with. By doing models Ed was designing cartoon characters.

At M.G.M. Tex Avery gave me a model sheet of Droopy to see what I would do to modernize it. He liked what I did and said; – Okay, come to work.

Later M.G.M. started cutting down. And TV started to cut in. So Tex’ unit was cut out. But Bill and Joe (Hanna-Barbera) wanted me to stay there and work for them. I didn’t work on “Tom and Jerry” – but other special pictures they were doing. Then the thing got cut way down. I left the place and was home doing comic books for awhile. And then I got a eall from Quimby (Fred Quimby was in charge of the cartoon units at M.G.M) to come in and talk to him about doing the set-up for this Gene Kelly thing. This was a whole picture -not just a sequence. It could have been really good-looking but they were all too sissy about it.

In the meantime Tex established his own commercial unit, Tex Avery Cartoons, and is sending over model jobs for me to do via one of the animators that worked at M.G.M. who was doing outside work for Tex. Hell, I was making more working a half-hour on a model (for Tex) on M.G.M.’s time than I made a whole day sitting there for M.G.M.!

Things were getting pretty hot over here, beginning to fold up. And Joe and Bill are working on things of their own. I did the Ruff ‘n’ Reddy models for’em. Anyway, we’re doing commercials over at M.G.M. for a while. For Schlitz, S-H stamps, and then the thing folded. Meanwhile I’ve been doing models and commercial layout for Tex. Hell, I’m making a minimum of twice what I was getting at M.G.M. I was doing all the H-B models “Huckleberry Hound”, “Quick Draw Me Graw”, “Flintstones”, etc. as well as the layouts. Now when they get loaded down at H-B, I get a call.

I asked Ed about working with the numbering system I’d heard was used at Hanna-Barbera. He called it a “file and number system”.

It was driving me crazy – he sighed. You would spend more time getting up from the board here and going over checking the files and numbers to see where you’re going . . . or looking up the right background. It would’ve been less work if I’d done the whole thing myself.

What about the u-nions? I asked. What’s the difference between the two, if any?

I can’t say what he is now – he emphasized. I can say of the middle era (The ‘forties and ‘fifties). The screen Cartoonists ‘Guild was considered a “Liberal” u-nion. The Motion Picture Screen Cartoonists was part of the I.A.T.S.E. It was considered the more moderate of the two.

If you’re looking for work in Hollywood, do you have to belong to the u-nion to get in down there?

Yeah. Furthermore, they’re not that long on work. So all the u-nion guys would have to come first.

I moved up here in ‘sixty-one. If the work followed me -fine. If it didn’t, the Hell with it! I’d had it. And I’d never liked it since I’d been in the business anyway. There were very few “talented” guys in the business. But the ones that had it – like Art Babbitt, Tom Oreb, John Hubley, Bob Cannon and Norm Ferguson – they were real geniuses! But many of the guys couldn’t draw their own breath. In the earlier days, the business was made up of cartoonists more than artists. Had there been more artists, there might have been a different picture.

Where did you think the future of animation lies?

I think it’s walking towards its grave. I can’t tell you how far it is between here and the grave. It’s like centuries ago when guys were carving with chisels, these ultra-fine hunks of lettering and sculpting in marble. The exactness. The fantastic things they were doing then. A guy could stand off and say: “Gee, that’s what I’m going to be when I grow up.” And you can go and keep saying it ’cause it was so beautiful, it was so superb-what’s better? But is it? There ain’t none of it. None. It’s just an old dead art.

Is that analogy valid for animation?

Sure it is.’

Why? Look at some of these television commercials…

That’s not animation. That’s using the animation medium … To me, most of it has no advertising value whatsoever… It’s just a lot of talk that somebody is trying to sell somebody and they’re not. The ad agencies are all wrapped up in their own immediately constructed little world. And they turn to each other and all of ‘em think: “This is ours”. Completely losing the total picture of whether it’s ours or yours or the next-door-neighbors’ . . . What’s it doing? What’s it supposed to do?

You don’t see any future in the business?

No.

Do you think it’s stupid to try getting into it?

Well, I can afford to be wrong. But for the most part . . . I would say “yes”. Stupid from the standpoint if you think you ‘re ever going to make something out of those things. But not stupid from the standpoint if you’re fascinated with it. If you’re intrigued to the point that nothing else will do, no, you’re not stupid. You’re smart. Go through and milk it . . . Being in the business was beautiful. Being in the business was keener than Hell. Informal! Friends of mine that had to work in offices – oh, they envied the Hell out of me. And I didn’t blame them!

With regard to the dollars and cents end of animated film making, Ed felt that the producer “might make a couple of bucks.” He cited ever rising labor and material costs as the main reason the profit potential in animation is lessened all the time.

Together we examined some “how to” books on animation by Eli Levitan and Roger Manvell. Later, Ed had this to say about them:

- Much of this stuff in the books was too much analysis. That never was done at all. That attitude just wasn ‘t there. It was more a natural reaction to things that they were seeing, or doing, or thinking.Finally we discussed “contemporary animation”. Ed took a pretty dim view of it all.

I was looking at these things on channel nine. And every one of ‘em are done in Yugoslavia or Arabia or some other place where the guys don’t make ten cents an hour. A gay is sitting down at a drawing board and doing anything that comes through his mind…I don’t even put it in the category of drawing. Animation? No such thing.

Have you seen any computer animation? I asked.

I have no use for it – he answered quickly. I have nothing but utter, unadulterated contempt for it.

Are you sure you’re not a little afraid of it?

Not in the least. It will never in your time touch animation. They are still a mathematically run machine. It hasn’t an iota of looseness. They’re finding out that computers have their limitations . . . It always has the same flavor, same attitude. It’s always there as a graph.

One can take issue with some of Ed’s opinions about animation as apart form and as a business. But what makes his remarks so compelling is his first-hand knowledge of the craft itself and of the many personalities who made the business of animation a “business”. His sentiments concerning the current “state of the art” are disconcerting to the animation enthusiast. But they are the outcome of his having been caught up in the rise and fall of the theatrical cartoon studio operations as well as the growth of a never, and to him, less satisfying sort of production geared to television.

I also suspect that this attitude stems from his own genuine concern for the craft – his frustration ai what animation has come down to as opposed to this notions of what it should be.

To some, Ed’s opinions may seem overly pessimistic. But before Ed would consent to this interview in preparation for this article, he forewarned me that he would not “romanticize the cartoon business”. He explained that this was his pet peeve with most of the articles and books that dealt with the history of his craft. And Ed Benedict was not about to further that sort of misrepresentation.

photos:

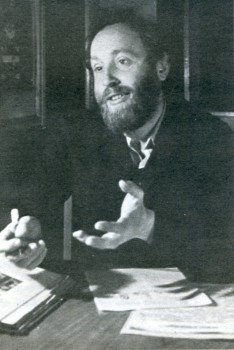

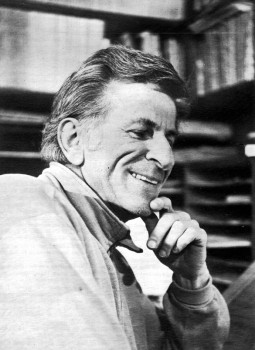

1. Ed Benedict

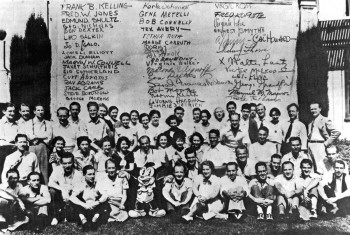

2. The Oswald the Rabbit team at Lantz

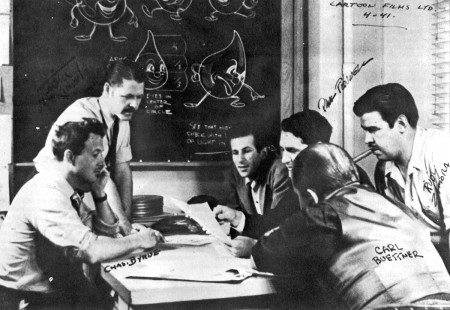

3. Ed Benedict among his collaborators

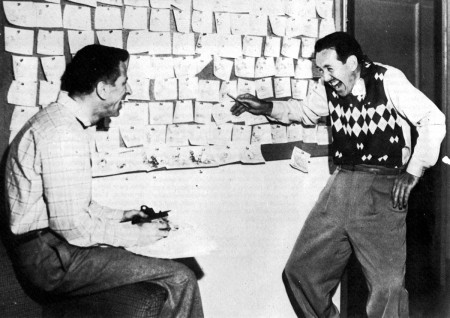

4. Ed Benedict and Mike Lah

A couple of comments.

- Sorry, I had to write the word “u-nion” that way because WordPress (on several different computers wouldn’t allow me to save that word. (Secret conspiracy?)

It’s unfortunate that Ed wasn’t asked more about his brilliant work at Hanna-Barbera. That’s where he truly came into his own and had such an enormous effect on the world of animation.

Articles on Animation &Commentary 30 Oct 2009 08:57 am

Live Action Directors Animate

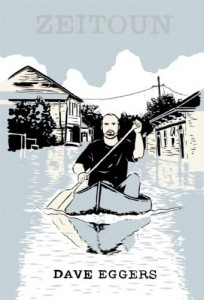

- The New York Times reported that Jonathan Demme is planning to make an animated feature of the book, Zeitoun by Dave Eggars.

- The New York Times reported that Jonathan Demme is planning to make an animated feature of the book, Zeitoun by Dave Eggars.

The book is about the reconstruction efforts taking place in New Orleans done since the Katrina disaster effort.

Apparently Demme was taken by the illustration on the cover of the book and immediately saw it as animation. He’s quoted as saying, “I was staring at the book, and there’s this wonderful line drawing on the cover, the character of Zeitoun in his canoe, paddling through a submerged neighborhood. And I suddenly imagined, What if we could do an animated film and visualize the experiences of the Zeitoun family and all of New Orleans?â€

They haven’t decided what the style of the film will look like, but Demme favors a hand-drawn style for the film.

The New Yorker magazine has a profile of Wes Anderson. (I’ve given the link to the magazine, but it’s open only to subscribers.) Anderson is the director of Rushmore, The Royal Tenanbaums and The Darjeeling Limited. He’s also the director of the upcoming puppet film, The Fantastic Mr. Fox, which was based on the Roald Dahl book.

The article opens and closes with a couple of columns about the animated film, but primarily focuses on Anderson’s bio and career.

In reading the article, a short bit popped out at me.

- For stop-motion animation, the actors’ voices must be recorded in advance, so that the figurines’ mouths can be moved in synch with the dialogue. The recording is usually done in a sound studio. Anderson did things differently. In the fall of 2007, he took a handful of actors, including (George) Clooney and (Bill) Murray, to a friend’s farm in Connecticut. In order to make the voices and the film’s soundscape realistic, Anderson had his actors perform the motions—running, digging, and climbing—that the figurines would perform; he recorded the exterior scenes in the fields, and the interiors in the farmhouse.

Anderson’s direction, with its protracted long takes and tight closeups, treats the figurines like actors, emphasizing their “performances.” The production designer, Nelson Lowry, told me that Anderson’s approach to animation was “very counterintuitive.” He made, Lowry added, “unconventional choices, such as keeping characters still. Usually, animators keep characters constantly in motion; if they re doing nothing, they blink.” Lowry calls Anderson’s expressive stillness a “compression of character.”

Let me repeat part of that last sentence: “Usually, animators keep characters constantly in motion; if they re doing nothing, they blink.”

This is the notion that live-action directors (probably all live action film makers) have of acting in animation. And I can’t argue too much with that. This is a good deal of acting in animated films: keep it moving, keep it moving, keep it moving regardless of the thought the characters are supposed to be having.

However, Anderson’s notion of acting, “keep it still” isn’t acting either. I remember Ralph Bakshi giving a talk after making Lord of the Rings, just prior to a screening. He said that humans stand still most of the time, but that if an animated character would sit still, it wouldn’t be acceptable. It would look like poor limited animation. It’s a problem good animators enjoy solving.

Unfortunately, what I’ve seen of The Fantastic Mr. Fox looks like poor limited animation in puppets – a bit like those old Rankin-Bass episodes of Pinocchio. The difference is that the characters, here, are covered with fur making them look more like an early Starevich film. (Regardless, I like Anderson’s films so I’m still looking forward to seeing this – however it’s animated.)

Unfortunately, what I’ve seen of The Fantastic Mr. Fox looks like poor limited animation in puppets – a bit like those old Rankin-Bass episodes of Pinocchio. The difference is that the characters, here, are covered with fur making them look more like an early Starevich film. (Regardless, I like Anderson’s films so I’m still looking forward to seeing this – however it’s animated.)

Getting back to some real animation, Hans Perk (in case you didn’t know) has been posting the drafts from Snow White. What a resource his site is! Many thanks, Hans.

Articles on Animation &Bill Peckmann &Daily post 21 Oct 2009 08:19 am

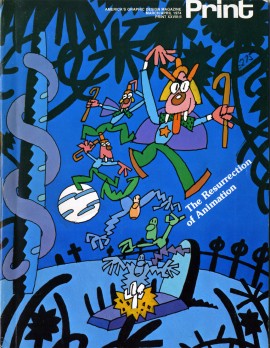

Print ’74

- I seem to remember a lot of industry magazines that would regularly publish articles about the animation industry. Millimeter, Film Comment, On Location, Hollywood Reporter all had their animation issues that I’d search out (long before I entered the business professionally), pore over, memorize and save.

- I seem to remember a lot of industry magazines that would regularly publish articles about the animation industry. Millimeter, Film Comment, On Location, Hollywood Reporter all had their animation issues that I’d search out (long before I entered the business professionally), pore over, memorize and save.

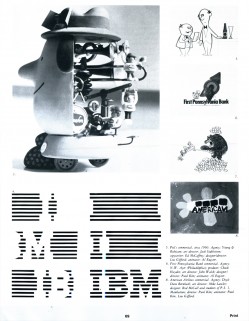

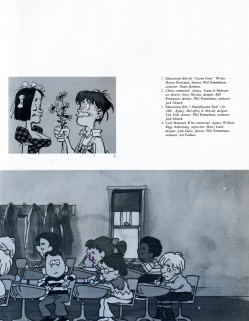

Print Magazine was a glossy magazine that featured lots of articles about design, usually print design, although there was the occasional animtion article. In 1974, there was a big issue about animation. One article, by Rod McCall, who was a designer for print as well as film, wrote an article about the commercial studios in New York with an accent on the design aspect.

Here’s that article, which is picture-centric in jpegs. If there were more text I’d have transcribed it, but this format seems best since the article is so attractively designed within the magazine.

1

1  2

2(Click any image to enlarge and read.)

Thanks to Bill Peckmann for the magazine to scan and share.

Animation Artifacts &Articles on Animation &Puppet Animation 22 Sep 2009 07:31 am

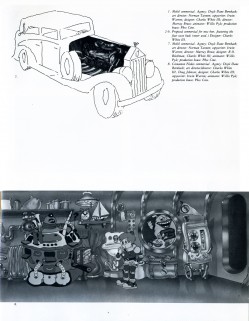

Coronet George Pal

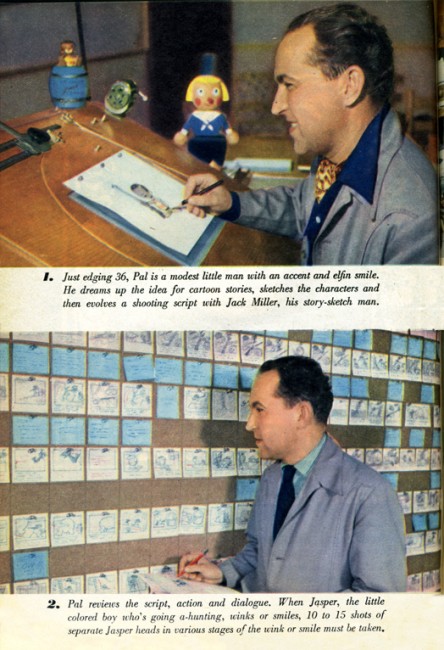

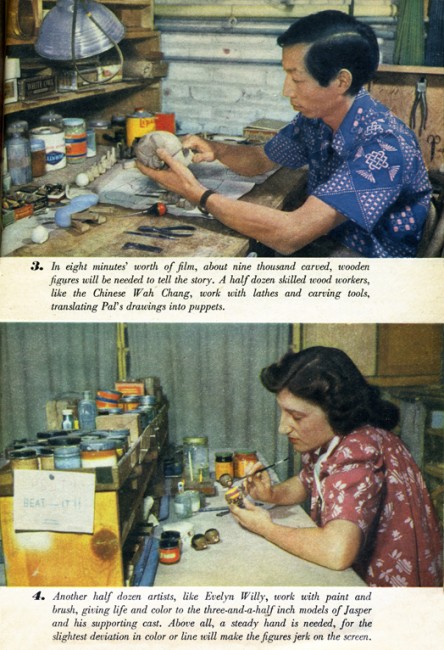

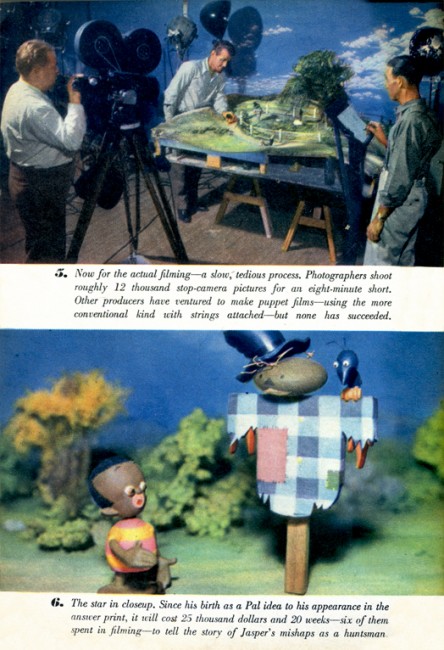

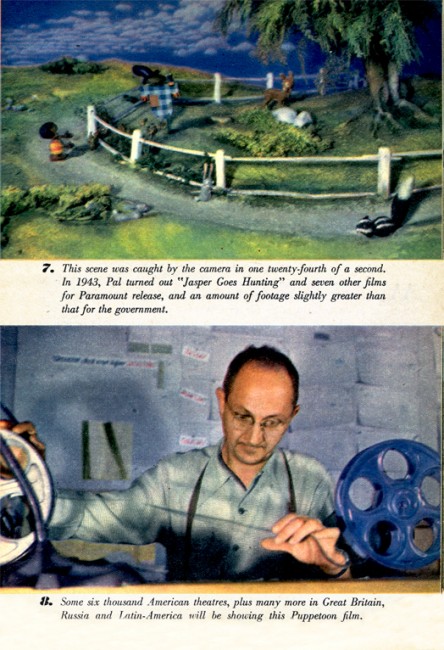

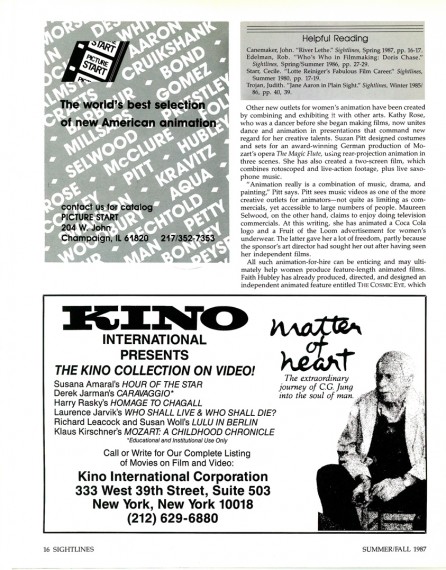

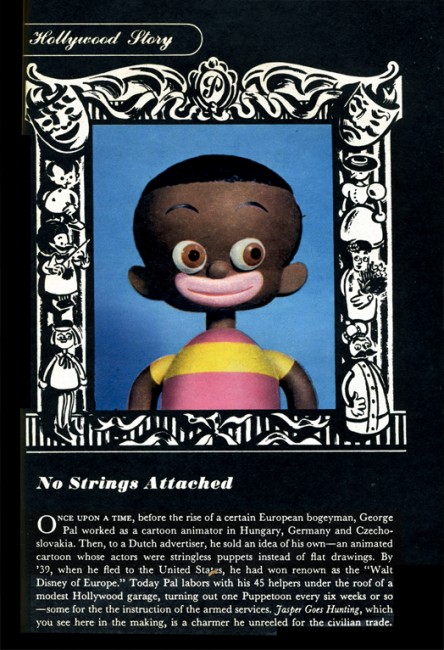

- In April 1944, Coronet Magazine printed an article about George Pal and the making of one of his very successful shorts done for Paramount. He had been nominated for seven Oscars for the shorts which included When Tulips Bloom, John Henry and the Inky Poo, and Dr. Seuss’ The 500 Hats of Bartholemew Cubbins, and he was given a special Oscar in 1943 for his puppet work.

- In April 1944, Coronet Magazine printed an article about George Pal and the making of one of his very successful shorts done for Paramount. He had been nominated for seven Oscars for the shorts which included When Tulips Bloom, John Henry and the Inky Poo, and Dr. Seuss’ The 500 Hats of Bartholemew Cubbins, and he was given a special Oscar in 1943 for his puppet work.

The short featured is Jasper Goes Hunting. This is one of the last of the films featuring this character, a holdover from the racist days of yore. Sort of a puppet version of Harman-Ising’s Bosco.

Pal’s style animated puppetry involved lots of replacement parts. If you wanted to move an arm, you had to create a dozen arms which would be replaced from frame to frame. It’s a very time consuming process and offers lots of opportunity of messing up a shot and having to start over.

(Click any image to enlarge.)

Note that Jerry Beck on Cartoon Brew just recently directed us to an auction

of many of George Pal’s puppets. Some of the puppets for the film featured

in Coronet are among those up for sale. This is the link to the auction.

Articles on Animation &Disney 05 Sep 2009 07:41 am

Snow White at 50

- Last week I posted an article about women in animation which originally appeared in Sightlines Summer/Fall 1987 issue. I’d also mentioned that the very same issue had an article by John Canemaker about Snow White’s 50th Anniversary. Naturally, I have to post that article as well. It ties in with the recent issue of D23 wherein John has an article about Snow White celebrating a new remastering of the film and the ways it continues to inspire new animation artists. This is its 72nd anniversary.

Here’s the article:

This year, Walt Disney’s first animated feature, SNOW WHITE AND THE SEVEN DWARFS, celebrates its golden anniversary with its re-release in some 2,000 theatres in North America and in venues in 60 countries overseas. The blitz of media events and publicity has encompassed proclamations, parades, and public appearances; soft-drink, clothing, and book tie-ins; a TV special; and, according to Jon Lang, Disney’s director of film licensing, “More merchandising for this movie than any other, including STAR WARS.” Even a Snow White rose has been created, with 100 bushes shipped to mayors in 40 major cities.

This year, Walt Disney’s first animated feature, SNOW WHITE AND THE SEVEN DWARFS, celebrates its golden anniversary with its re-release in some 2,000 theatres in North America and in venues in 60 countries overseas. The blitz of media events and publicity has encompassed proclamations, parades, and public appearances; soft-drink, clothing, and book tie-ins; a TV special; and, according to Jon Lang, Disney’s director of film licensing, “More merchandising for this movie than any other, including STAR WARS.” Even a Snow White rose has been created, with 100 bushes shipped to mayors in 40 major cities.

To date, the half-century-old SNOW WHITE has worldwide grosses totalling more than $330 million, making it one of the most popular motion pictures of all time and the movie that saved the Disney studio from financial disaster. “You should have heard the howls of warning when we started making a full-length cartoon,” recalled Walt Disney years later. Hollywood pundits called it “Disney’s Folly,” and predicted no one would sit through a seven-reel cartoon.

One of Disney’s reasons for producing SNOW WHITE as a full-length, animated cartoon was financial: The introduction of double-features during the 1930′s bumped Disney’s one-reelers—his cartoon “fillers”—off the screen. The other reason was an artistic one: A bold visionary and innovator, Walt Disney wanted to make full use of his staff’s extraordinary skills, which were developed during the making of his short films. Starting with Mickey Mouse’s debut in 1928, the Disney studio artists made remarkable and steady progress in expanding the stylistic and narrative parameters of the animated cartoon.

Disney’s introduction of certain technological elements-sound and color—forced animation to change. Soundtracks dimensionalized a character’s personality and toned down the over-exaggerated pantomime favored by the silent cartoons. In 1932′s FLOWERS AND TREES, one of Disney’s experimental Silly Symphonies (a series of shorts begun in 1929), Disney utilized a three-toned Technicolor process that allowed for a full range of hues. Old graphic formulas for characters and forces of nature were gradually redesigned to convey the illusion of reality and sincerity that Walt saw in his mind’s eye. The plots of the shorts came to be based on the personalities of the characters, rather than on mere action or gags. Thus, the emotional possibilities for animation were extended as never before.

Unprecedented Problems

The problems encountered in the making of SNOW WHITE were unprecedented. More than 750 artists worked on the film for three years, creating at least two million drawings (of which 250,000 made it into the film).

One of the most formidable problems was the animation of the human figures. The Princess, the Queen, the Prince, and the Huntsman had to be convincing for the melodrama to work. Indeed, the audience had to truly believe that two cartoon characters were going to murder another cartoon character. Previous unsuccessful attempts to portray human motion included the 1934 Silly Symphony, THE GODDESS OF SPRING. To overcome the drawing problems and stiff animation of that experiment, Disney established art classes on the studio lot. All staff artists were obliged to attend in order to study films frame-by-frame and to draw from a nude model. In addition, live models were filmed for the animators to study; interestingly, the model for Snow White was a young dancer who later became famous as Marge Champion.

The animation of the human characters works, for the most part, but is spotty. Snow White has a unique, sweet charm, but the poor Prince is never more than a cardboard symbol of a romantic hero. In contrast, the seven dwarfs are superbly realized. “These inspired gnomes,” wrote New York Times caricaturist Al Hirschfeld, “with their geometrical noses, flexible cheeks, linear mouths and eyes, highly stylized beards and costumes . . . lend themselves to articulation because of the tremendous magic of well-directed lines. But the characters Snow White, Prince Charming, and the Queen are badly drawn attempts at realism. … To imitate an animated photograph, except as satire, is in poor taste.”

For SNOW WHITE’S feature-length format, the violent, fast action and bright colors used in Disney’s earlier short films had to be softened and paced to sustain audience interest. Muted earth tones of green and brown predominate, and the extensive use of shadows enhances cool forest scenes, as well as bright meadows and moonlit castles. Snow White’s nightmarish escape through the forest is a scene full of rapid cuts and violent movement. It is followed by the sequence in which the forest animals discover Snow White, which is gentler and slower-paced than the one that precedes it.

The score, eight songs by Frank Churchill and Larry Morey (including “Whistle While You Work,” “Someday My Prince Will Come,” and “Heigh-Ho”), advances the plot and adds to our knowledge of the characters and their motivations, desires, and inner thoughts. The integration of songs with the plot precedes Broadway’s Oklahoma by six years.

Disney’s greatest personal input was in the development of the script and the personalities of the characters. The final scenario is admirably lean, clocking in at 83-action-packed minutes. While the story is succinctly told, it is also filled with details, the result of three years of intensive story conferences and ruthless storyboard critiques by Walt and his creative staff. Six months of work on the film was scrapped by Disney, and he ordered entire scenes redrawn. Three sequences in story-board or rough animation were cut from the film, not because they were bad, but because they impeded the flow of the story. At a recent press conference at the new Disney animation studio in Glendale, California, drawings and test footage from those “lost” sequences were shown. It was apparent that those sequences—which feature the dwarfs’ bed-building routine, soup-eating song, and a dream ballet with Snow White and the Prince—would have been as charming and entertaining as anything that remains in the film.

Disney’s perfectionism drove up the cost of the movie, produced during the Depression years of 1934-37, to astronomical heights, from an initial $150,000 to $1.5 million. “As the budget climbed higher and higher,” said Walt, “I began to have some doubts, too, wondering if we could ever get our investment back.” There was a cliff-hanging deal with a bank to borrow more money; but as the world knows, SNOW WHITE finally proved a great success. The film made its world premiere on December 21, 1937, and reviews were glowing. SNOW WHITE initially earned $8.5 million at the box-office, an enormous sum for the time, especially since children’s movie tickets cost 10 cents.

Feminist Reassessment

Although SNOW WHITE is undeniably a masterpiece of American cinema and a classic of character animation technique, the film has recently become the focus of feminist reassessment and anger. Feminists argue that Snow White is a symbol of female passivity, as she waits to be rescued by an active male, who will give her life purpose and meaning. Film historian Sally Fiske suggests that in order to “comprehend the statement SNOW WHITE makes, imagine reversing it. Try to imagine that the dwarfs were seven little women and the title character was a young prince. The story becomes utterly inconceivable—which is a very telling comment about how we perceive women.”

Charles Solomon, writing in The Los Angeles Times about this subject, interviewed Karen Rowe, an associate professor of English at UCLA specializing in fairy tales and folklore. “While children need a sense that a young figure can confront problems and surmount them, heroes tend to overcome problems in more active ways,” claims Rowe. “What I think is problematic for the 20th century reader of popular tales-including the Disney versions— is that no provision is made for activity on the part of the heroine. It’s all rescue, all passivity. What that communicates to a female child is that it’s never by your own will or action that you overcome a problem. It’s through intervention on your behalf by some other figure. That undercuts any sense of growth and leads to a cultural emphasis on female dependency, which I think is very destructive.”

When SNOW WHITE AND THE SEVEN DWARFS was made in the 1930′s, issues concerning women’s rights, feminism, and role models were not part of the social consciousness of the time. Our approach to viewing SNOW WHITE today should be the same as the one we bring to viewing other film classics, such as THE BIRTH OF A NATION, whose ideology is out of step with current important social issues. Parents should discuss such anachronistic screen images with their children, placing the characters within the context of the period in which they were created and supplementing them with alternative stories and female characters who are, as Professor Rowe says, “more affirmative of a young girl’s ability to act.”

John Canemaker, a contributing editor to Sightlines, ;s the author of Winsor McCay—His Life and Art, recently published by Abbeville Press.

If you want to see more pictures from Snow White, I posted a bunch of model sheets last Monday. Go here.

Articles on Animation &Independent Animation &Tissa David 29 Aug 2009 07:45 am

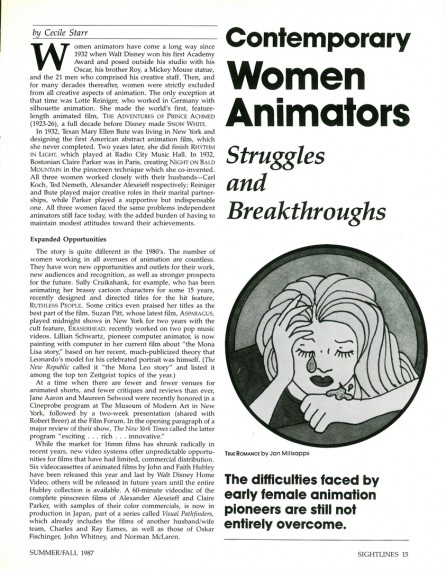

Sightlines – Women

- The Summer/Fall 1987 issue of Sightlines magazine had an article about women in animation. The article is by Cecile Starr who wrote frequently about Independent Animation. This feature was a companion piece to one the magazine offered about Snow White’s 50th anniversary.

- The Summer/Fall 1987 issue of Sightlines magazine had an article about women in animation. The article is by Cecile Starr who wrote frequently about Independent Animation. This feature was a companion piece to one the magazine offered about Snow White’s 50th anniversary.

Back from the 70′s through the 80′s there were a number of articles and features about women animators, and it was welcome. However since then the notice has been limited. Rarely are there articles about women animation artists (other than the infrequent Mary Blair article).

I’d like to see more of them, and it’s not a bad start by posting this article. (I’ve decided to show ads and all.)

1

1(Click any image to enlarge.)

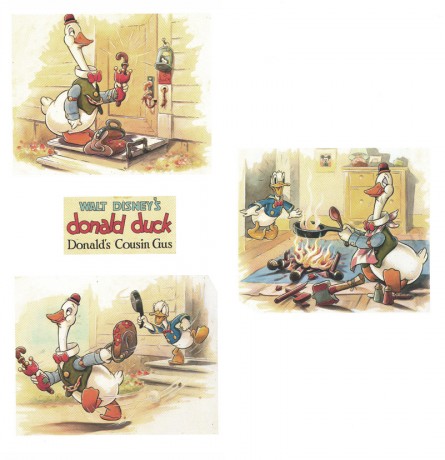

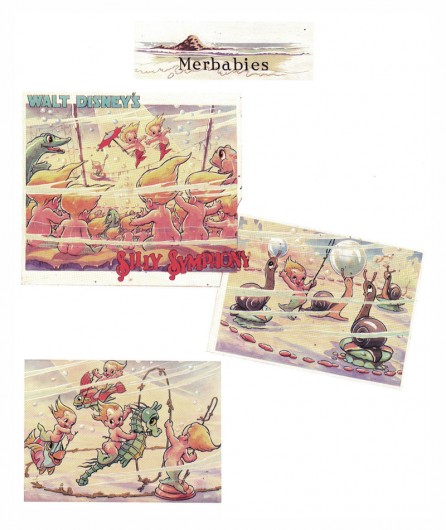

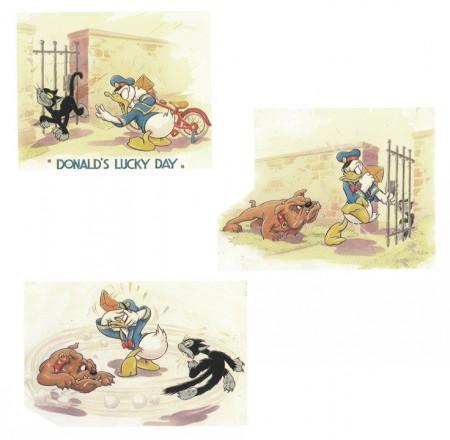

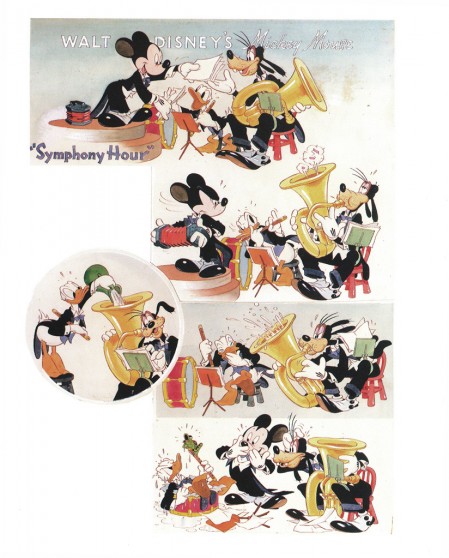

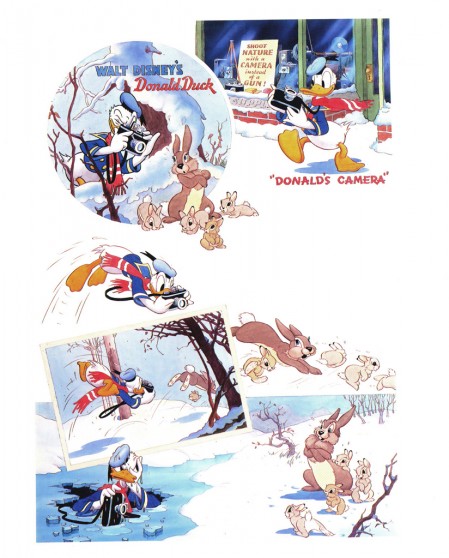

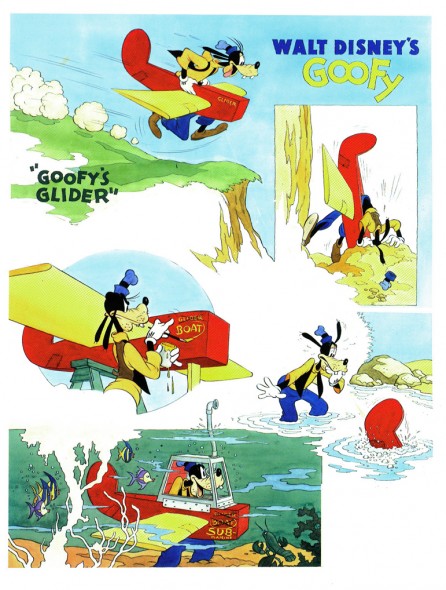

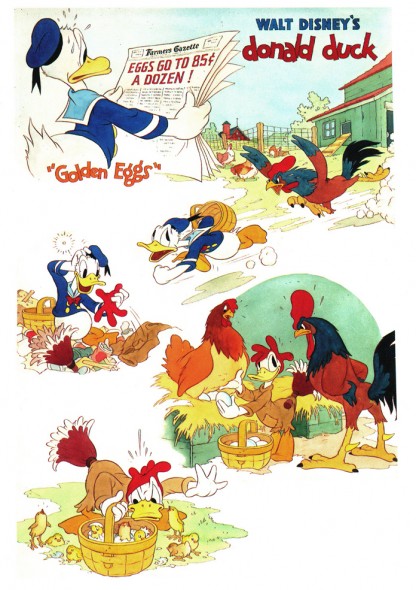

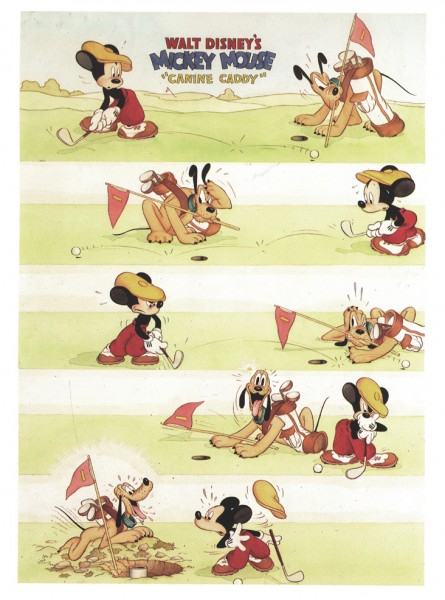

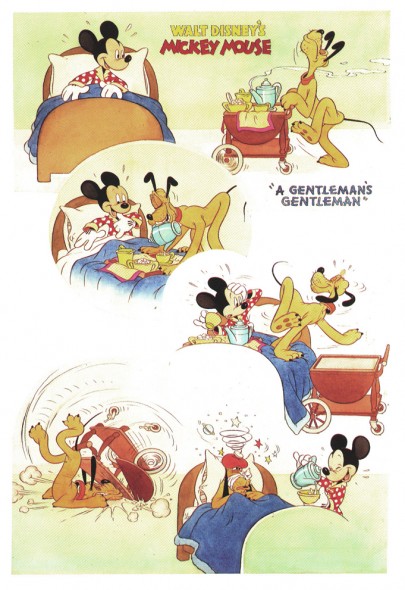

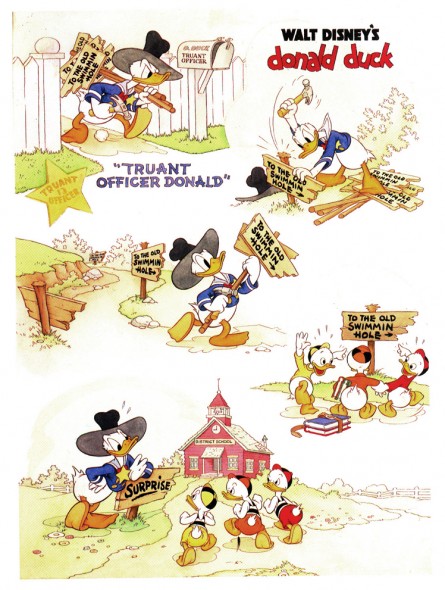

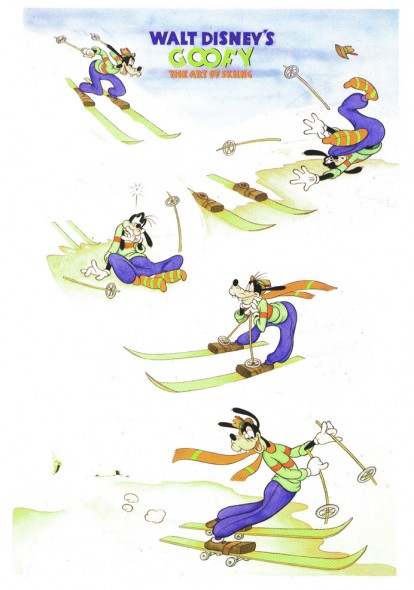

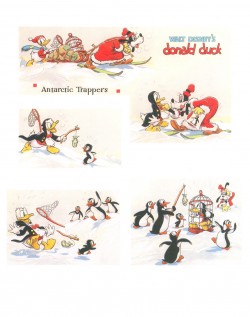

Articles on Animation &Bill Peckmann &Books &Disney &Illustration 27 Aug 2009 07:26 am

Good Housekeeping 2

- Before getting into today’s post, I want to make sure you’ve all seen the notation on Tom Sito‘s great blog today. (An amazing and unique blog if there was one.)

- 1968- Former master animator Bill Tytla’s request to return to Disney was turned down. The artist who animated Grumpy the Dwarf, Dumbo and the Devil on Bald Mountain even offered to do a free “trial animation test” to show he still had it. Disney exec W.H. Anderson wrote him:” We really have only enough animation for our present staff.”

Tytla died later that year.

- This is the second part of my posting of the illustrations from Good Houskeeping Magazine.

- This is the second part of my posting of the illustrations from Good Houskeeping Magazine.

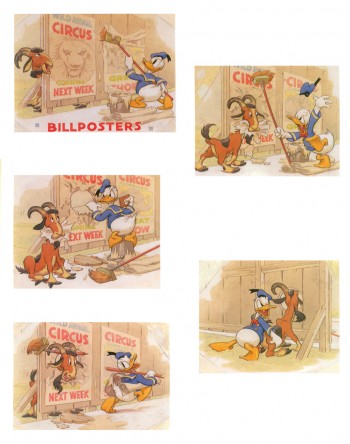

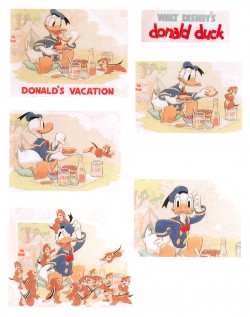

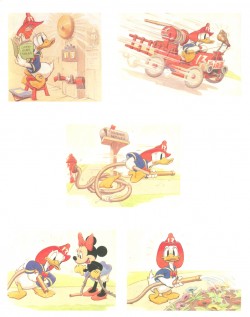

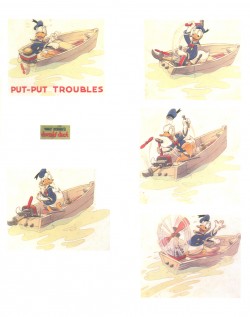

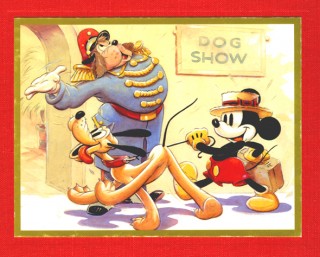

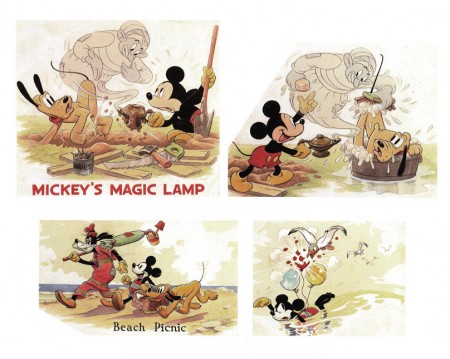

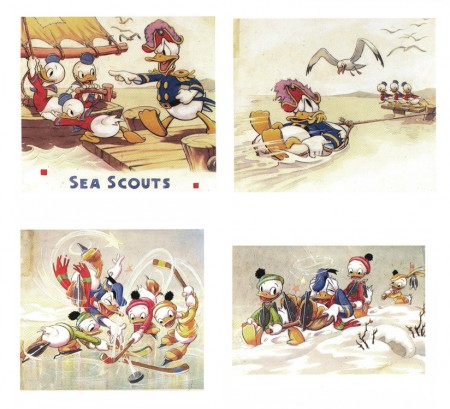

From 1934 continuing into the late 1940′s, they printed four-color full page previews of newly-released Disney shorts. These illustrations were, at first, painted by Tom Wood, and later by Hank Porter.

The Alexander Gallery collected these illustrations in 1987 for an exhibition, and they published a book of them. Bill Peckmann has kindly loaned me his copy of the book.

These illustrations were published recently in the book, Walt Disney’s Mickey and the Gang. It’s a good book which publishes more art than the Alexander Gallery collector’s item. However, the printing in this book feels more glossy and contrasty. The delicacy of the watercolors is sacrificed. That’s why I’m intent on posting them in the better form. However, this book also includes a lot of other info on the animated films and it includes the text originally published in Good Housekeeping.

Here is the second group of pages:

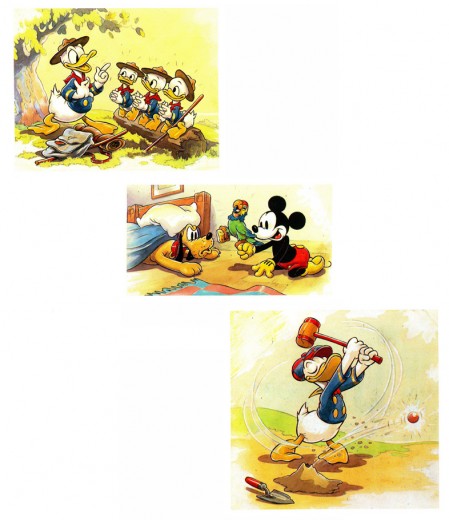

Mickey’s Magic Lamp 1940 | Beach Picnic 1938

The Sea Scouts 1939 | The Hockey Champ 1939

The Good Scouts 1938 | Mickey’s Parrot 1938 | Donald’s Golf Game 1938

Interesting to note the play with Mickey’s ears. These are the ears

with three dimensions used in only a couple of shorts.

Another play on Mickey’s ears – very different.

.

Animation Artifacts &Articles on Animation &Disney 22 Aug 2009 07:46 am

Animated Film Techniques 2

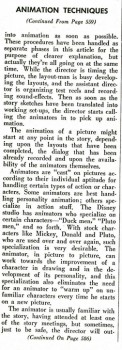

Here’s the completion of a series of articles from American Cinematographer Magazine as published in 1958. It was split in four parts. Written by Carl Fallberg, the article illuminates about the process of animation production.

Animated Film Techniques

This is an old xerox copy, so I apologize for any quality problems. Here’s the last of two parts of the article.

21

21

(Click any image to enlarge to a legible size.

23____

23____ 24

24___

25

25___

26

26  27

27___

28

28  29

29

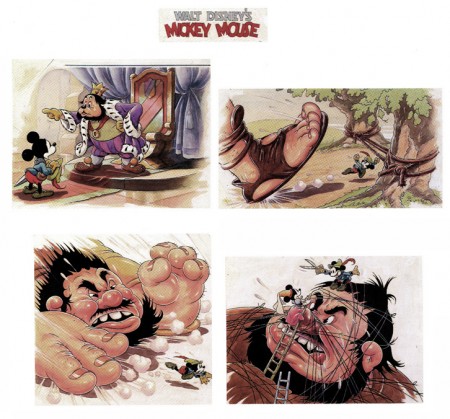

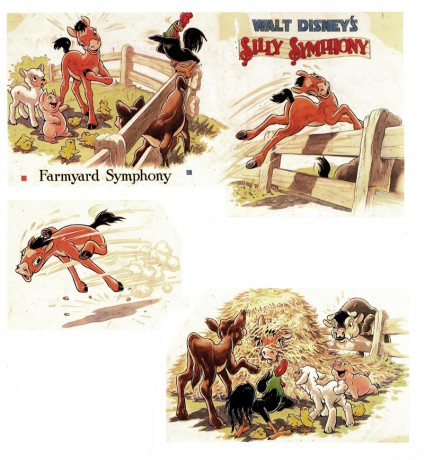

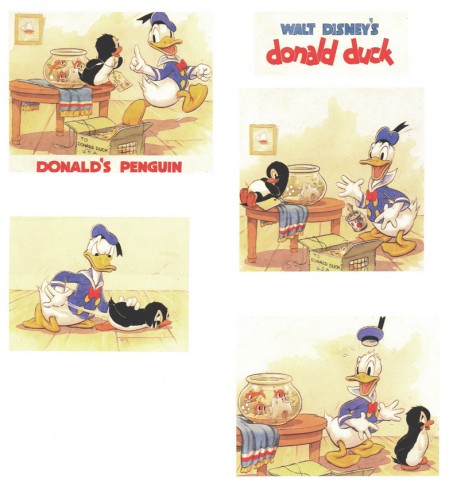

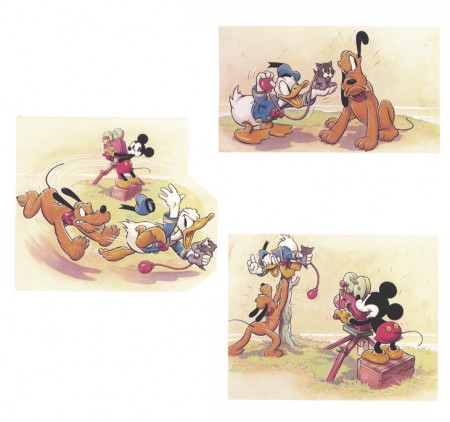

Articles on Animation &Bill Peckmann &Comic Art &Disney &Illustration 20 Aug 2009 07:20 am

Good Housekeeping 1

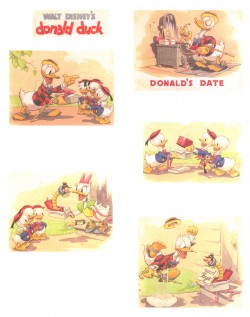

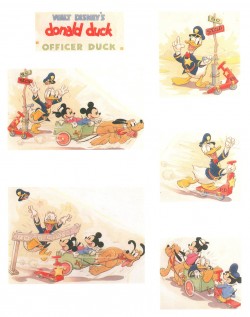

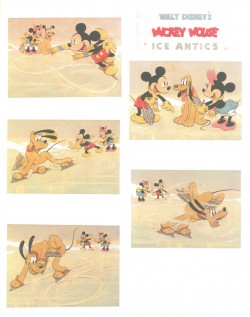

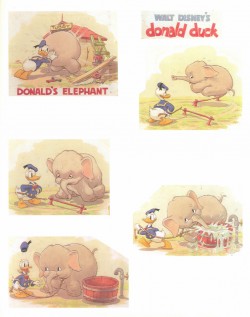

- From 1934 continuing into the late 1940′s, Good Houskeeping Magazine printed four-color full page previews of newly-released Disney shorts. These illustrations were, at first, painted by Tom Wood, and later by Hank Porter.

- From 1934 continuing into the late 1940′s, Good Houskeeping Magazine printed four-color full page previews of newly-released Disney shorts. These illustrations were, at first, painted by Tom Wood, and later by Hank Porter.

Here’s information from the book on Wood and Porter:

- Tom Wood came to Disney Studios in 1932 from his position as a Los Angeles daily newspaper artist. A quiet, hardworking individualist, he was well liked and highly regarded by those who knew him both personally and professionally. He worked at the Studio until his untimely death in 1940 and, as publicity artist, assumed primary responsibility for the monthly Good Housekeeping page as well as the creation of publicity stills for the theater. Since Good Housekeeping was the only magazine for which Disney produced these monthly watercolor sequences, we recognize their scarcity.

Wood typically worked on each of these pages for a full week. Beginning with sketchy, pencilled drawings which he would then ink himself, he also created the final watercolors which represented a 7-minutc Disney film short. Assisted by an “idea man” and a third person who wrote the story or dialogue, the publicity artist had the final approval on the finished version. After Wood’s death Hank Porter would continue working with the magazine well into the late 1940′s. Thereafter, production of these shorts was discontinued as costs became prohibitive and the Studio refused to compromise on quality.

The Alexander Gallery collected these illustrations in 1987 for an exhibition, and they published a book of them. Bill Peckmann has kindly loaned me his copy of the book, so I’ll post the illustrations over a number of posts.

Here are the first group of pages:

1

1

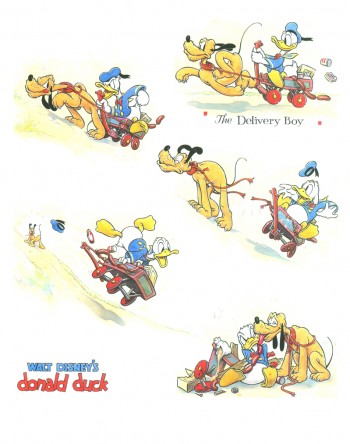

Donald Duck in “The Delivery Boy” 1938

(L) Donald Duck – Antarctic Troopers 1938

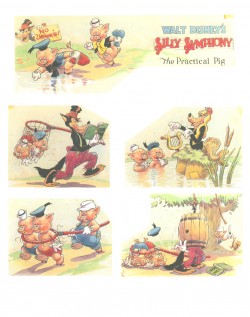

(R) Silly Symphony – The Practical Pig 1938

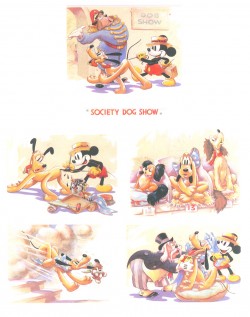

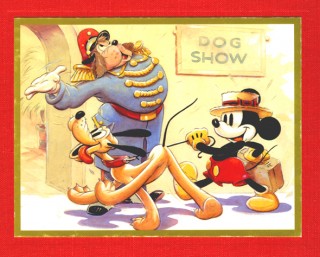

(L) Mickey Mouse – Society Dog Show 19389

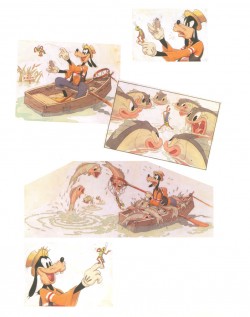

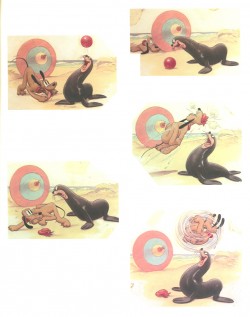

(R) Goofy and Wilbur – Goofy and Wilbur 1939

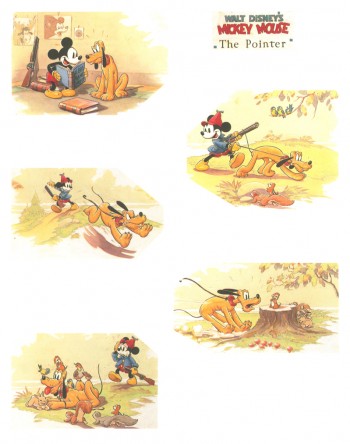

Mickey Mouse – The Pointer 1939

(L) Donald Duck – Donald’s Date 1939

(R) Donald Duck – Officer Duck 1940

(L) Mickey Mouse – Ice Antics 1940

(R) Donald Duck – Donald’s Elephant 1940

Donald Duck – Billposters 1940

(L) Donald Duck – Donald’s Vacation 1940

(R) Donald Duck – Window Cleaners 1940

(L) Donald Duck – Fire Chief 1940

(R) Donald Duck – Put-Put Troubles 1940

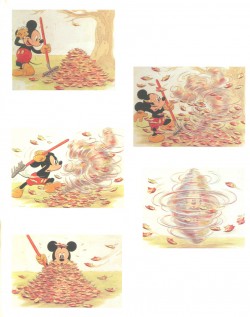

(L) Mickey Mouse – The Little Whirlwind 1941

(R) Mickey Mouse – Big-Hearted Pluto 1941

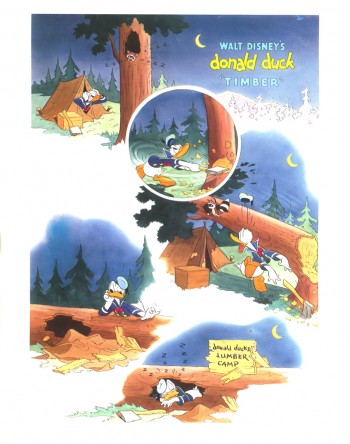

Donald Duck – Timber 1941