Monthly ArchiveJuly 2010

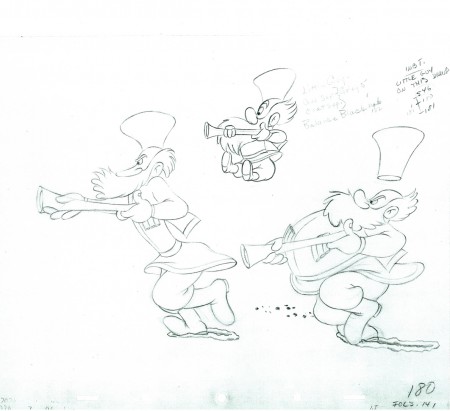

Animation &Animation Artifacts &Disney 21 Jul 2010 07:21 am

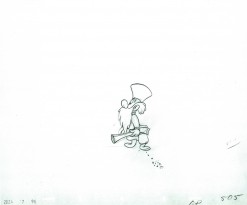

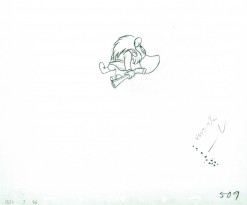

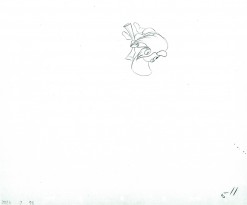

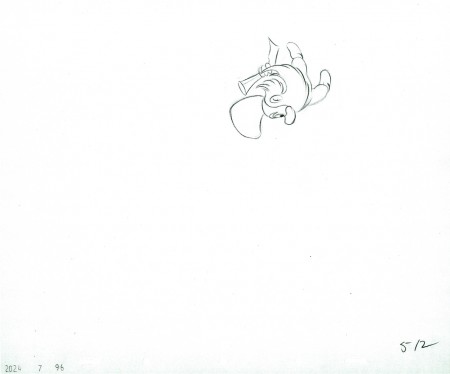

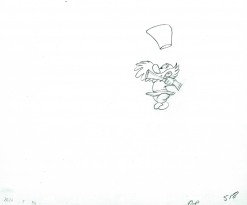

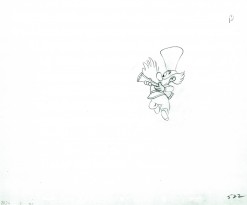

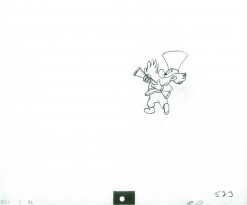

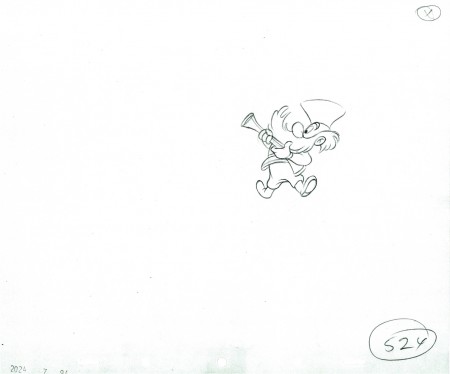

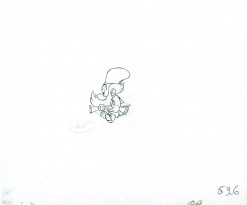

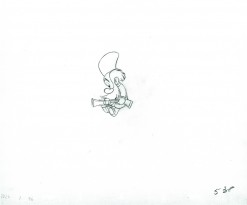

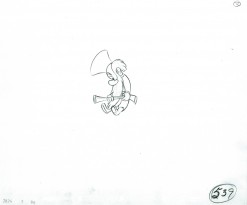

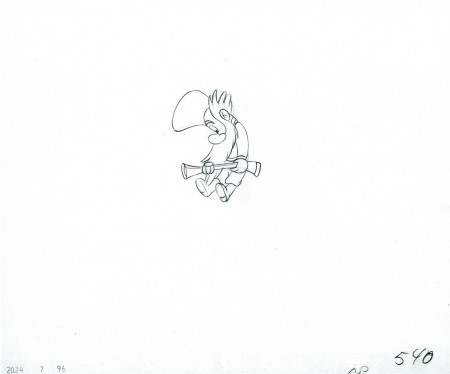

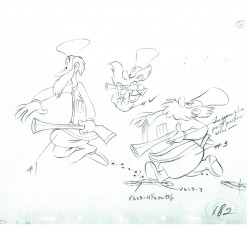

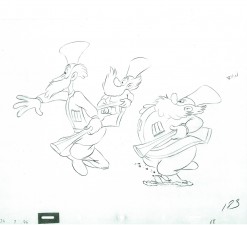

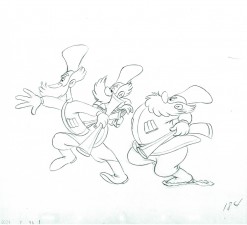

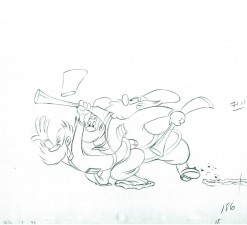

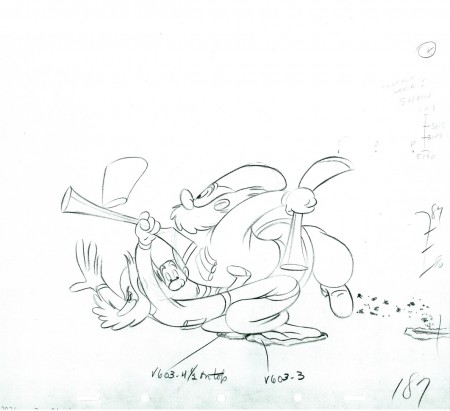

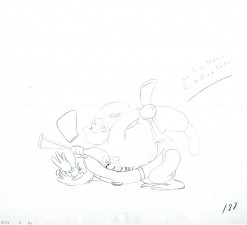

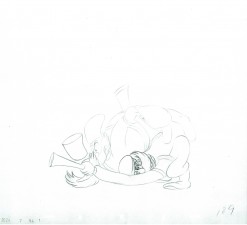

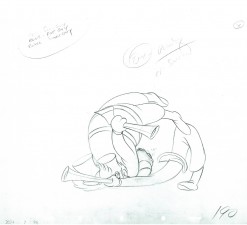

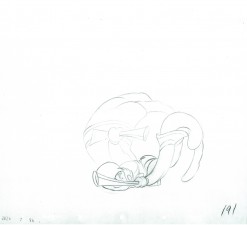

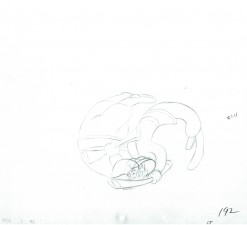

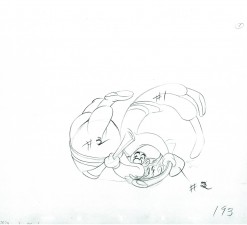

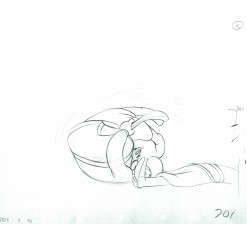

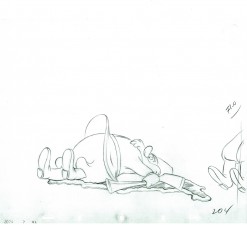

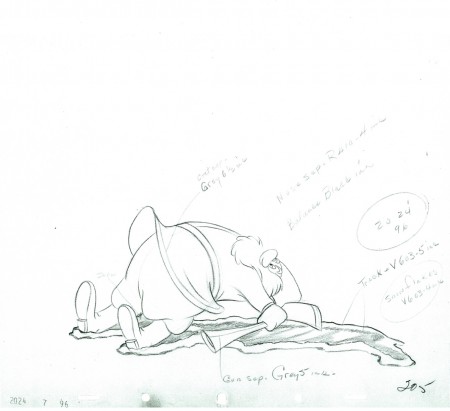

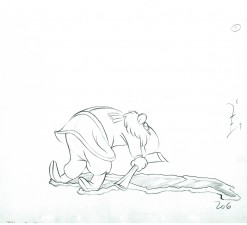

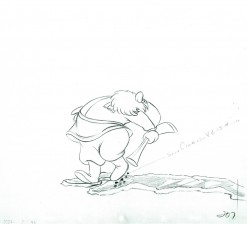

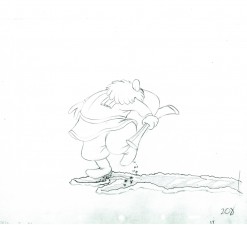

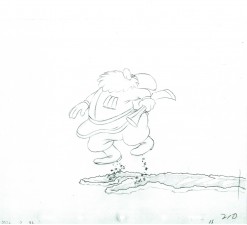

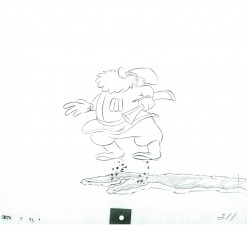

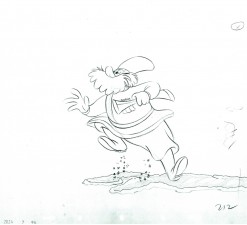

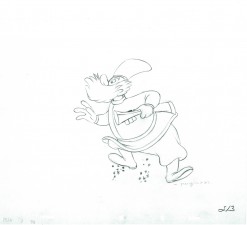

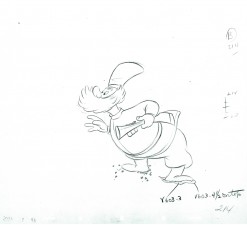

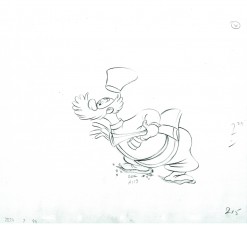

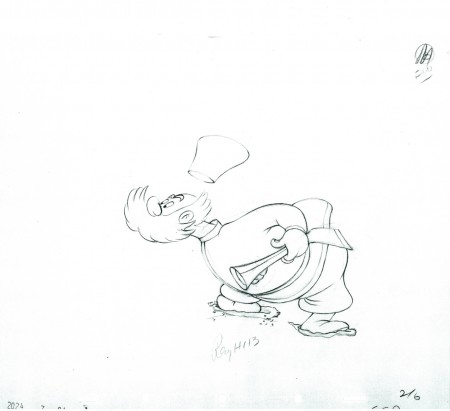

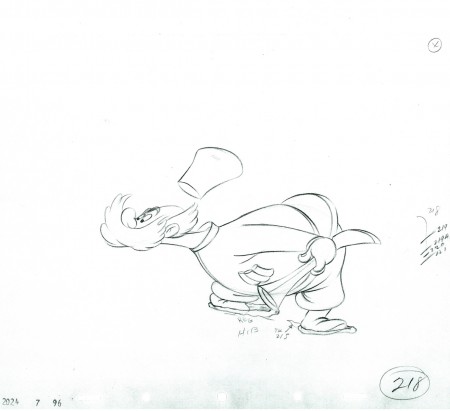

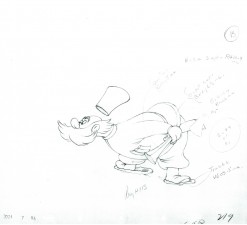

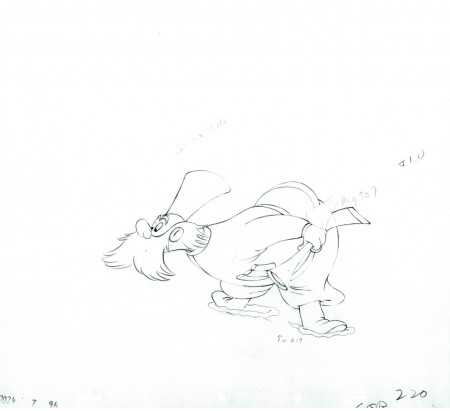

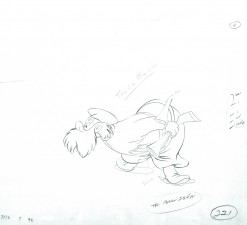

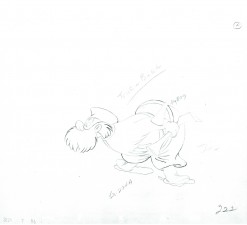

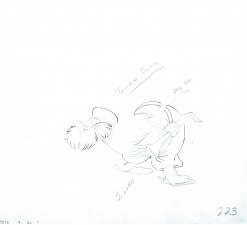

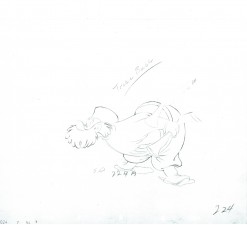

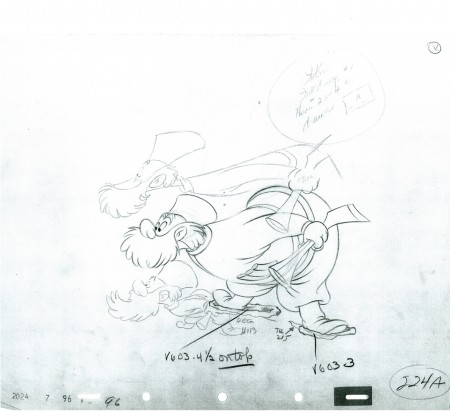

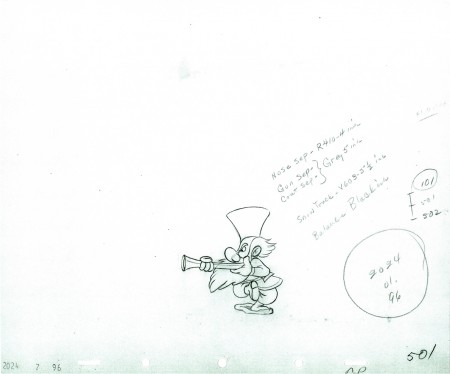

P&W-Kimball Scene – 6

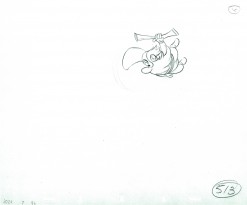

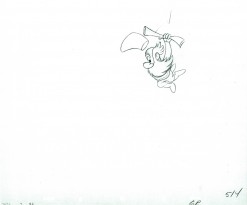

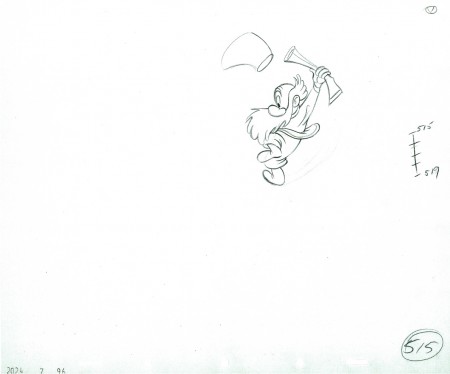

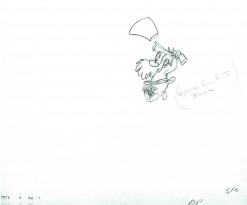

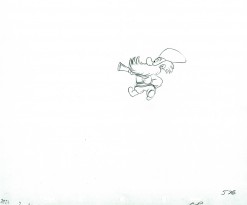

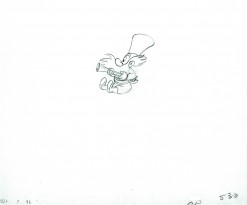

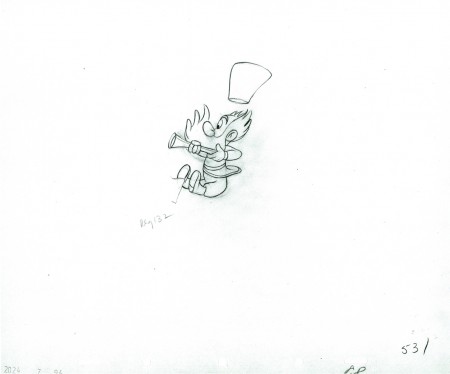

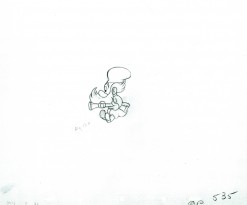

- I’ve posted the principal level of the three hunters from this scene out of Peter and the Wolf. It was animated by Ward Kimball.

At one point the little guy pops onto his own level, and as Mark Mayerson astutely noted in a recent comment on this blog, he’s the animation that makes the scene work. The curve against the straights. It’s all goofy animation, and works in a very funny way.

Here, I start posting the 117 drawings of the little guy (roughly 40 at a shot) and will combine him with the others in the PT below.

The scene is on loan from John Canemaker and my thanks couldn’t be greater.

501

501

The following QT movie represents all the drawings of the bottom level

as well as the first 40 drawings of the Little Guy who comes in where he should.

I exposed all drawings on ones.

Right side to watch single frame.

To see the past five parts of the scene go to: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3,

Part 4, Part 5

Articles on Animation &Books &Commentary &Independent Animation 20 Jul 2010 07:50 am

Women Animators

- Back in the enlightened Eighties, Independent animation actually took note of gender in the making of animated films. In The Art of the Animated Image, An Anthology edited by Charles Solormon included an article about Women Animators in the medium. The article by Lauren Rabinovitz was part of a series published in conjunction with the Walter Lantz Conferences on Animation held June 12th thru 14th, 1987 at the American Film Institute in LA.

I reprint the article here, and I consider that, to my knowledge, it’s nice to know that all but one of these women mentioned are still making Independent films. I wonder if the record is as strong for the “Independent” male animators of the same period.

and

Women’s Experiences

BY LAUREN RABINOVITZ

Histories of American animation have most often located the form within the confines of the Hollywood cinema and television system. Over the seventy-five years or so of its existence, that system has seldom proven hospitable to women filmmakers, or animators, whether they were working in film or, later, in television.

Outside Hollywood, the medium of animation has flourished in the work-a-day world of education, industrial and advertising films, and in those arenas women animators have found opportunities not available in Hollywood (especially over the past twenty years). Of even greater significance, the growth of avant-garde film after World War II nurtured female, as well as male, animators, filmmakers dedicated to individual artistic expression and to the creation of new film syntaxes within an alternative economic support system.

As independent cinema became increasingly tied to college and museum institutional frameworks in the late 1960s, so too did the individual filmmakers. In that period and thereafter, they typically became identified with academic training and teaching positions, the aesthetic vocabularies of vanguard art movements, and the apparatus of an American avant-garde cinema. In the 1970s and 1980s, rising from those antecedents, feminist filmmakers and animators have participated in independent cinema networks.

However much independent cinema may be viewed as a “marginal” practice within the Hollywood hegemony, women filmmakers—and animation as a cinematic form—lie at the outskirts of those heterogeneous cinematic margins. As neither women filmmakers nor animators have extensive showcases, distribution outlets, and production monies available to them, their short works are known largely through a variety of exhibition practices: film festivals; distributors’ animation packages (often collected for and exhibited at schools and film societies); cable TV “fillers”; and individual (and often visiting) artist screenings at museums, colleges and media centers.

Within this somewhat limited and restricted production, distribution and exhibition network, women animators have created a broad spectrum of work, utilizing a range of animation techniques, styles, and subjects. Line animation, cut-outs, xerography, photos, computer-generated imagery, sand-on-glass, have all been used by woman animators. Some have chosen to explore formal and spatial relationships; others delve into the “serious” art of highly abstracted, non-representational animation. Some have relayed children’s stories and folktales, personal experiences and feelings; others have created humorous narratives and political satires. Many have chosen to construct animated tales that comment on the artistic process itself. There is no “women’s animation” any more than there is one unique form of women’s film or video.

Nonetheless, just as male filmmakers have frequently exposed intimate, often sexual experiences from a subjective point-of-view, women animators tend to explore women’s experiences from an equally subjective perspective. Such subject matter takes on a dual political dimension—in the increased visibility and expression of gender identities and experiences, and in the recognition of the systematic repression of women’s subjective experiences within the Hollywood cinema. A significant number of contemporary women animators rely on cartoon animation— figuration in short narratives—as a means of recasting their relationship to the ideology of representational cartoons.

There is a long list of recent films by women animators that address women’s experiences in this fashion. They run the gamut, from Tanya Weinberger‘s tiny naked woman who carouses on and then arouses a sleeping giant in Gulliver Comes to Lilliput (1983) to Suzan Pitt‘s Asparagus (1978), an elaborate eel-animated psychodrama that intertwines a woman artist’s creative process with metaphors of sexual activity.

Christine Panushka‘s The Sum of Them (1983), line portraits set against a familiar collage of sounds, depicts many women as an absorbing poem of humanity. In Another Great Day (1980), Jo Bonney and Rugh Peyser dramatize the important inter-relationships among popular cultural forms, fantasies, and women’s labor through a housewife who moves freely between the cartoonesque world of her chaotic household and the photographic world of television soap opera and romance photo-novels. Women have also collaborated to celebrate collectively their experiences as’ women who are not always “solitary” animators. Lisze Bechtold, Lesley Keen, and Candy Kugel, My Film, My Film, My Film (1983); Caroline Leaf and Veronica Soul, Interview (1979).

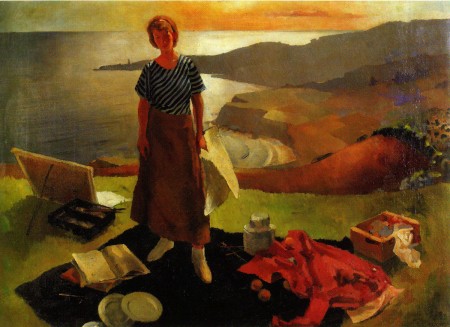

Some artists portray an autobiographical female subject notable for her physical metamorphoses, which approaches self-induced schizophrenia. In turn, this state of fluid change can often provide a positive catharsis. For example, Karen Aqua‘s Vis-a-Vis (1983) turns the artist/character into two connected halves of one person—the animator at her storyboard and the woman gazing out the window. When the halves split, the artist animates kaleidoscopic images while the woman passes through richly colored sea and mountains. When the woman returns to the artist, she empties radiant color into the drawings.

Kathy Rose’s Pencil Booklings (1978)

Kathy Rose also plays with the magical transformations of an animator character. Mirror People (1974) and The Doodlers (1975) both rely upon the protagonist’s constantly evolving physical shapes in an eerie, surrealistic world. In Pencil Booklings (1978), the artist/character (who resembles Rose) is represented more naturalistically through rotoscoping. Within the narrative she is pulled into the world of her imaginative creation and eventually back out of it, her identity assured by her exploration of the creative process itself.

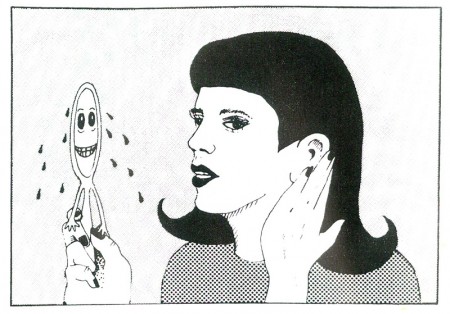

Joanna Priestley‘s Voices (1985:) also relies upon the artist’s physical presence as well as her v ice to comment on her self-image. As a likeness of the filmmaker addresses an anthropomorphic (and smart-alecky) mirror, she describes first her bodily-related fears of aging, gaining weight, and wrinkles. As she succumbs to her preoccupation with fear itself, she gives vent to increasingly cataclysmic horrors that are visually portrayed— things that go bump in the night, monsters of the id, nuclear holocaust. The background prattle provides a counterpoint to the character’s self-absorbed fears creating a tongue-in-cheek commentary that suggests women’s fears about themselves are a culturally induced neurotic obsessiveness.

Joanna Priestly’s Voices (1985)

It is important to note that these artists depart from the traditional Hollywood use of sound, the acoustical enhancement of nature. Although the cartoon world may always be seen as inherently fantastic, the animation studio’s use of sound helped reinforce the notion of a spatial and physical world. These animators employ layers of sound effects and music to destabilize the spectator and to stress the fantastic itself.

Emily Hubley, the daughter of animators John and Faith Hubley, carries the metamo-phosing, autobiographic subject to new intensities. In Delivery Man (1982), she presents a simply drawn, ever-changing abstract self in an equally volatile, abstracted world. Less the object of whimsical artistic introspection than the subject of her fearful dreams relived, the constant visual metamorphosis supports a remembered vision of personal traumas. The woman’s personal narrative of five key dreams involving her birth, her mother’s surgery, and her father’s death during surgery visualize the crisis of familial relationships, development and sexual identity that comprise the subjects of many patients’ transactional analysis.

Kathy Rose has extended the woman animator’s autobiographic involvement to a redefinition of the medium itself. Her Primitive Movers (1982) is a 30-minute piece that combines animation and Rose’s dance performance in front of the moving images. The animation is a constantly moving, colorful backdrop of lifesized dancers who evoke series of art styles—from Egyptian to Cubist to Art Deco. Their relentlessly rhythmic, angular movements provide not so much a chorus line for Rose’s sharply expressive movements but a fluid commentary on changing spatial relations, perspective, and Rose’s intertwining of 2 and 3 dimensions, as well as her bodily interaction with them.

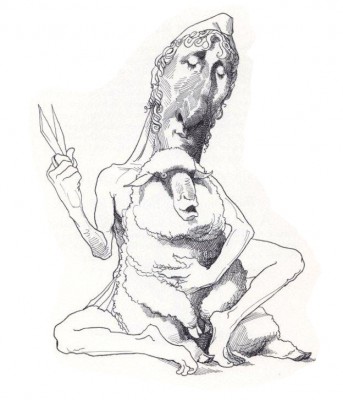

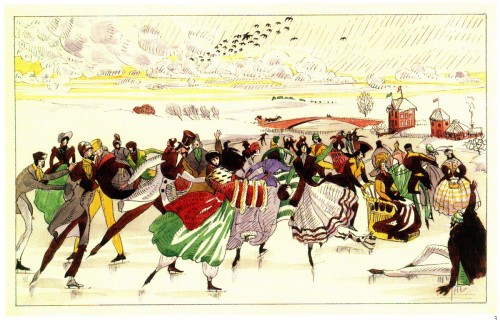

In this regard, several women animators connect their work to the history of art in ways that allow them to reconstitute woman’s place—no longer the object of male desire, but as the controlling subject. Maureen Selwood‘s Odalisque (1981) is, perhaps, the best example. In a humorous inversion of the history of western painting, Selwood portrays her odalisque as the subject who imagines and controls the flow of images. This female is no longer the prisoner of other artists.

Maureen Selwood’s Odalisque (1981)

Selwood calls attention to a more naturalistic figuration as the basis for a realism regarding women in Western art. By juxtaposing two styles in a jarring fashion, she poises fluid, graceful motion associated with the feminine against the disintegration and evaporation of form associated with the cartoon world. Made with the aid of romance and adventure—as a cafe artist and an opera singer—in these dreams, she deflates as male fantasies the romantic conventions usually associated with these constructs. In each sequence, she escapes the conventional confines of the fantasy that would relegate Woman to passivity or death and flows back to her living room, her visually nurturant world.

Whether there is an inherently feminine language in these works as well as in women’s writing, visual arts, and other expressive arts has been a topic of much feminist discussion in the 1970s and 1980s. Some critics maintain that even acknowledging the existence of feminine language does not insure that such “inscriptions of women’s voices” will be necessarily heard by all audiences. Female filmmakers frequently rely upon existing codes and conventions no matter how much they are filtered through their own vocabulary. In addition, their audiences may choose to interpret the films within the confines of already established canons, an act sometimes amplified by the films’ marketing and critical reviews.

What is at stake here is not the discovery of a feminine or feminist aesthetic running through women’s animated films, but the ways in which contemporary animators collectively construct feminist experience. They rely upon devices usually associated with expressive animation—physical metamorphosis, strongly-defined character personalities, and dream-like fantasy logic. But they represent these processes by defining women as their subjects, presenting specifically female sexual and non-sexual fantasies, and imagining self-identity and fears through one’s physical changes and fluidity as well as through controlling the environment outside oneself.

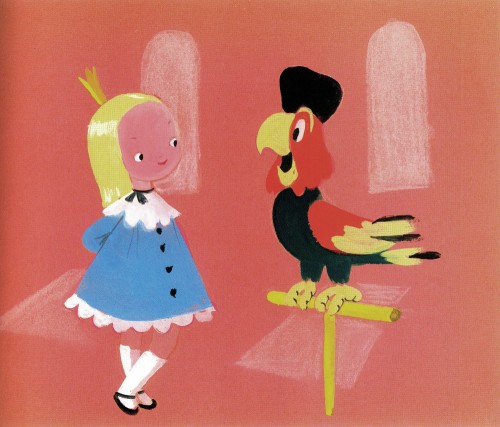

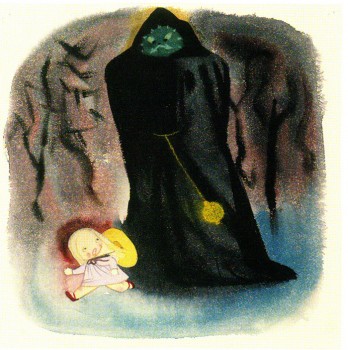

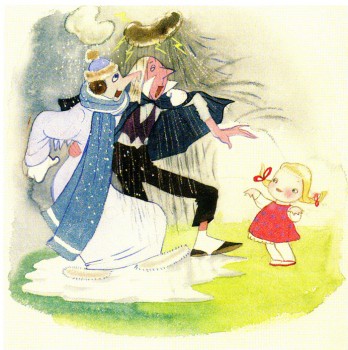

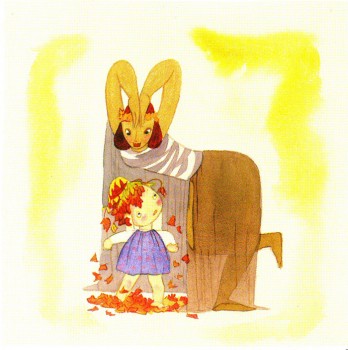

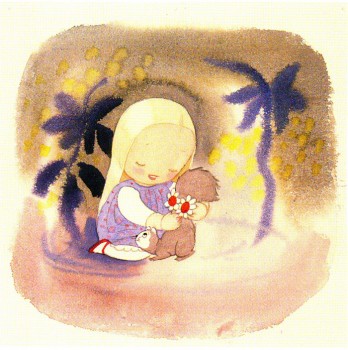

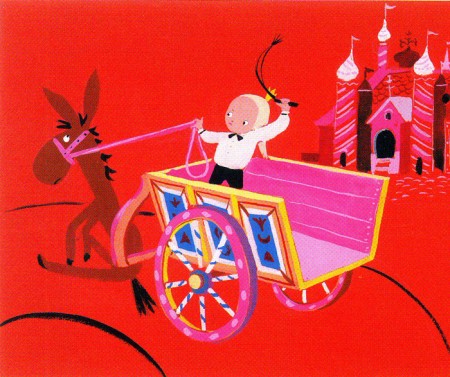

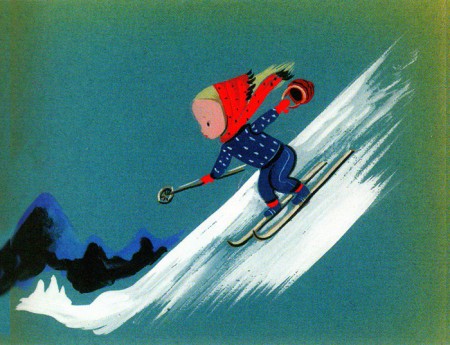

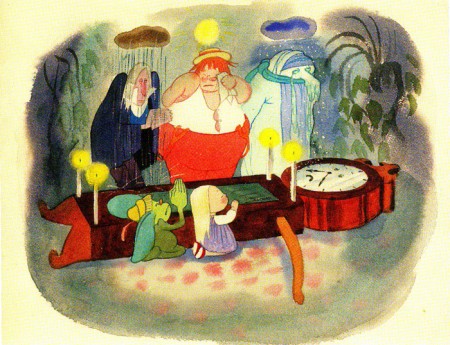

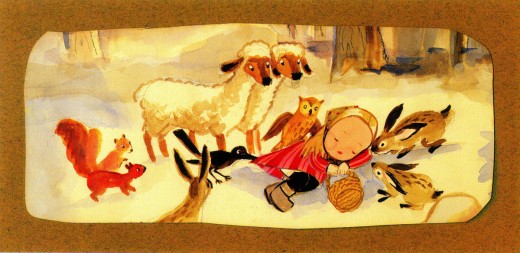

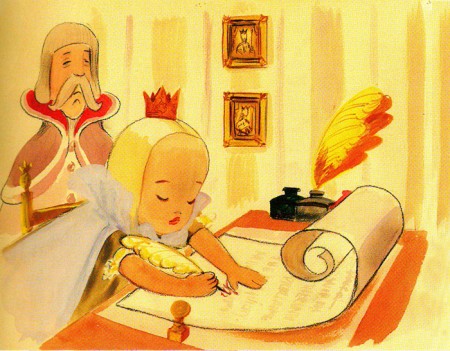

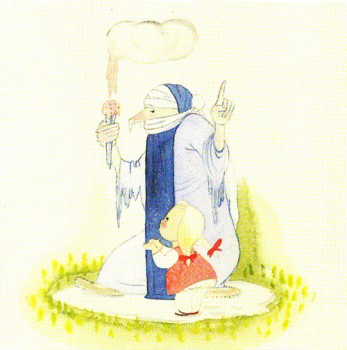

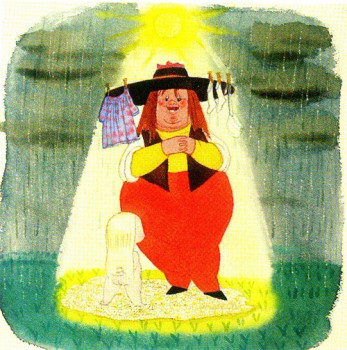

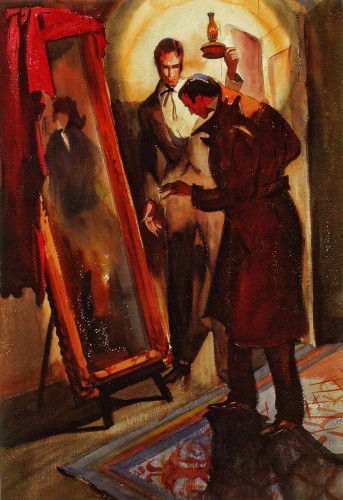

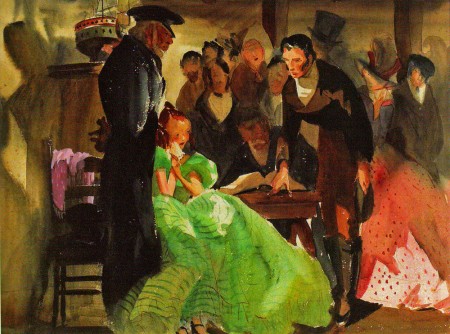

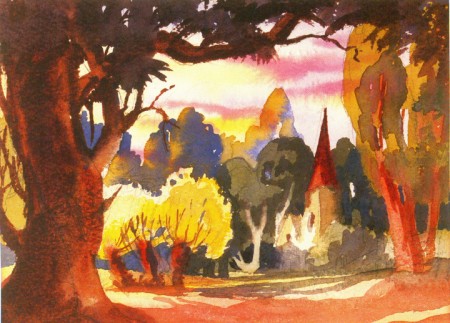

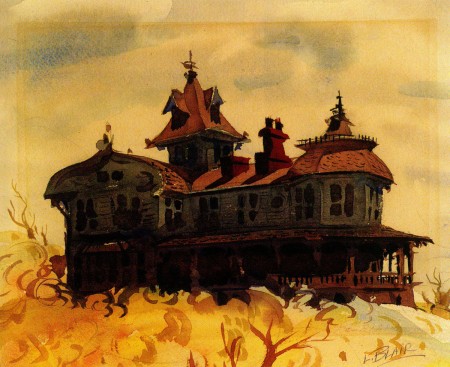

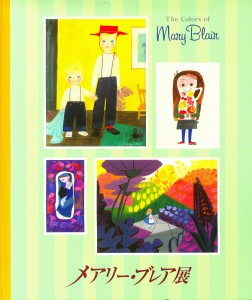

Books &Disney &Illustration &Layout & Design &Mary Blair 19 Jul 2010 07:58 am

Mary Blair – 2

- I’d like to continue showing some of the Mary Blair work pictured in the Japanese book, The Colors of Mary Blair.

The work is sensational, of course, but they aren’t very well identified (in English). Hence I’ve chosen images almost at random without really knowing what projects they’re designed to illustrate. When I do have information, I’m passing it along. I suspect others of you may be able to identify it better that I. (I certainly don’t consider myself an authority on Mary Blair.) If so, please feel free to leave comments.

Mary Blair at Disney.

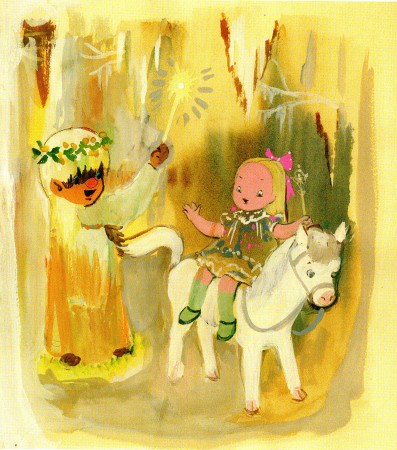

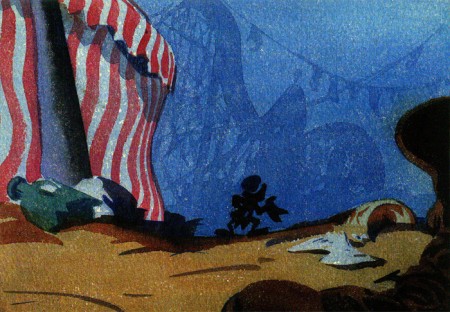

These first 5 images are from Penelope, a feature about a

time-travelling girl that was never produced.

The following group come from various sources.

Some are from Penelope, although others look like they were

done on the South American trip, with the bold colors.

The following group of six are labelled: “Upsidedownia.”

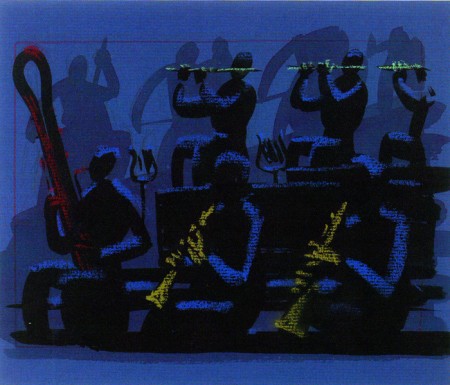

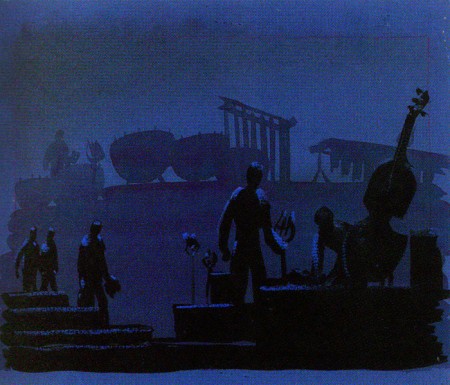

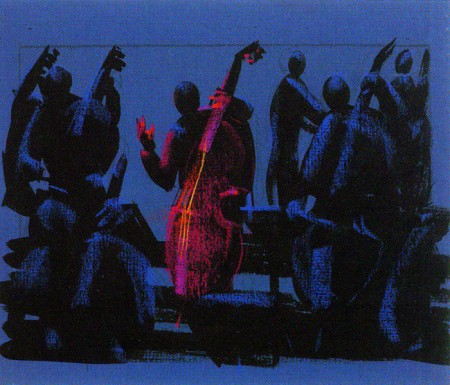

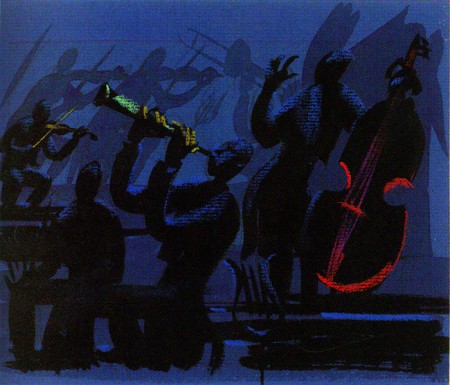

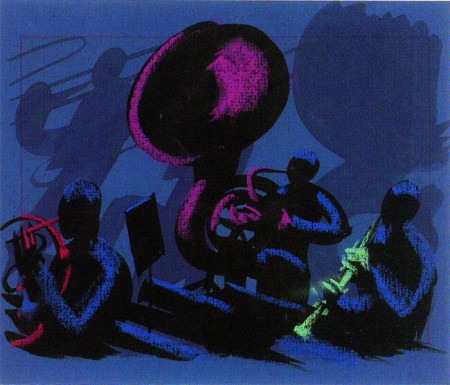

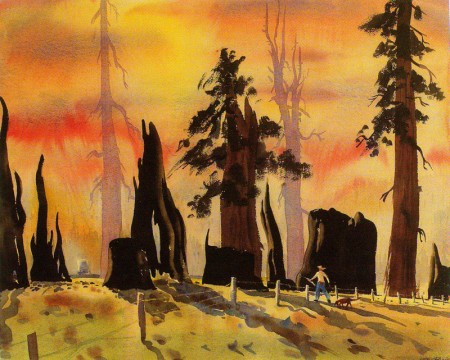

Here are some watercolors Lee Blair did for Fantasia:

And a couple for what looks like Pinocchio.

Commentary &Photos 18 Jul 2010 07:26 am

More Things I Love

- A couple weeks back, I posted some photos of things I love around my studio. When you have a place like I do, and you’re as much of a gatherer as I am, things start piling up. There are in the maelstrom I call my workplace a number of things I absolutely love and love looking at.

Here are more of them:

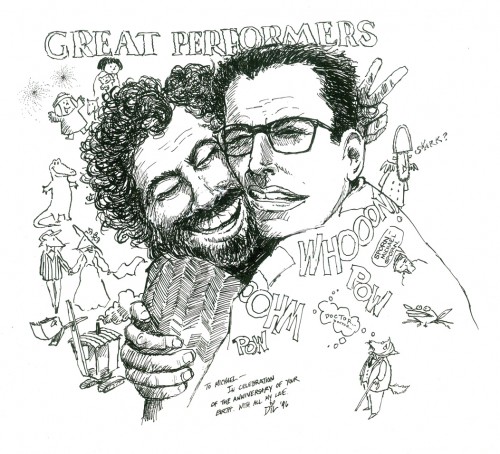

John Dilworth did this drawing of me with him surrounded by

some of the characters from my films. The picture came from

a photo taken of the two of us up at Lincoln Center.

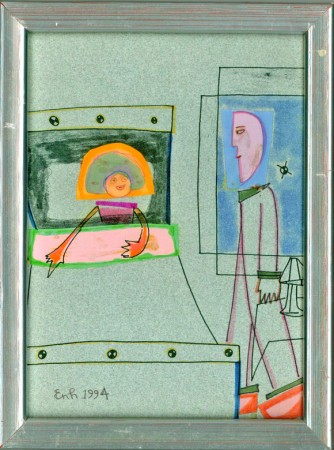

Laura Bryson did this little jewel of a painting – almost a Persian

miniature – of some of the bits from a number of my films.

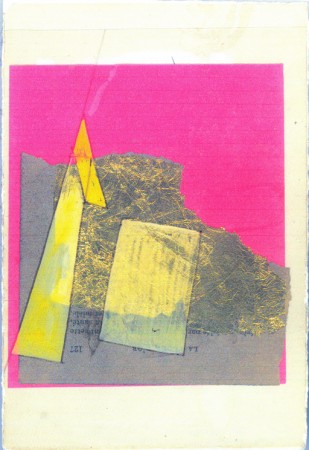

Emily Hubley gave me this great framed drawing.

Bridget Thorne collaborated with her son, Matthew,

on this illustration that says everything to me.

But then this was the first time they collaborated as mother/son.

Here’s Bridget’s birth announcement for Matthew many years ago.

Away from the art, here are some more things:

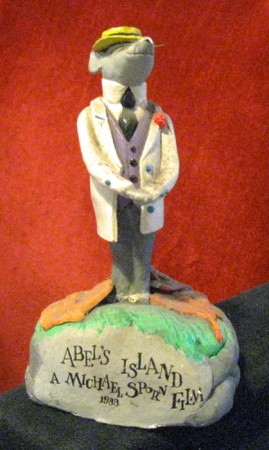

When we were completing Abel’s Island, John Dilworth made this

little sculpty statue of Abel. His walking stick has long been lost.

Wendy’s, at one time, gave away this little zoetrope

(that never really worked.)

I love this Oswald the Rabbit pin which was a giveaway

for all lovers of the Bill Nolan rabbit back in 1931.

I treasure this Pinocchio marionette, that was given to me by my

beloved Heidi as a birthday gift many years ago. The puppet is an

antique made of a wood pulp that they used before they invented plastic.

Bill Peckmann &Books &Illustration 17 Jul 2010 07:17 am

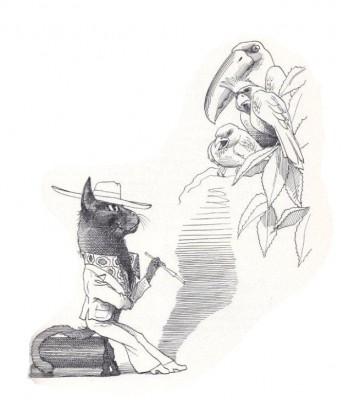

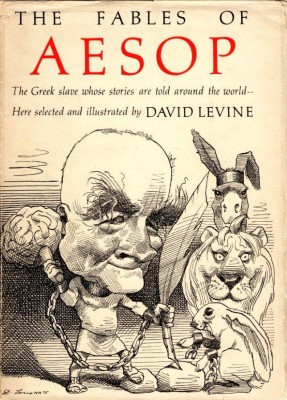

David Levine Lions

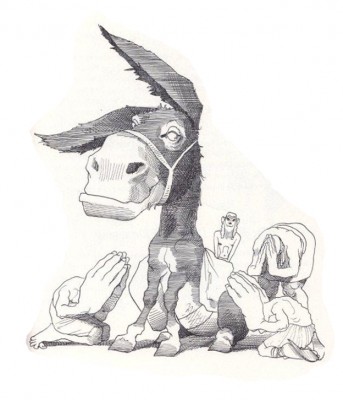

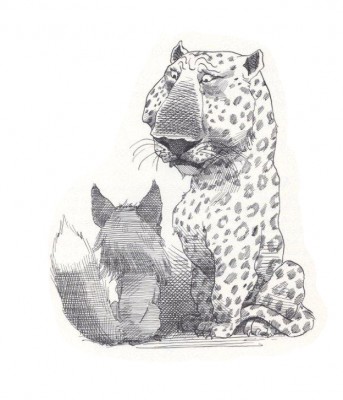

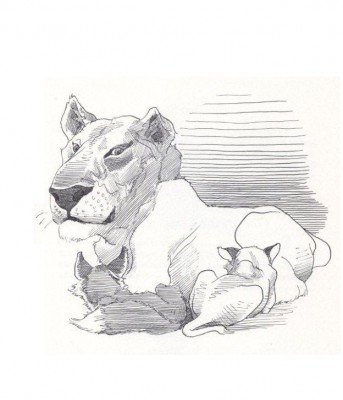

- Bill Peckmann sent me a parcel of lions and Aesop’s Fables from David Levine. These dawings are so brilliant that it’s impossible not to share them today. Enjoy.

Many thanks to Bill.

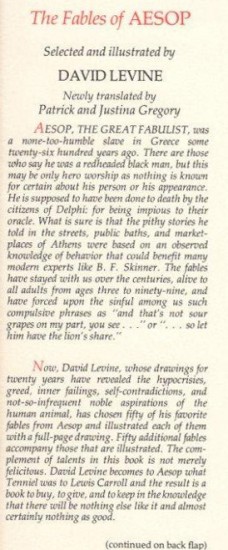

The cover ant the (enlarged) frontispiece from the book.

2

2

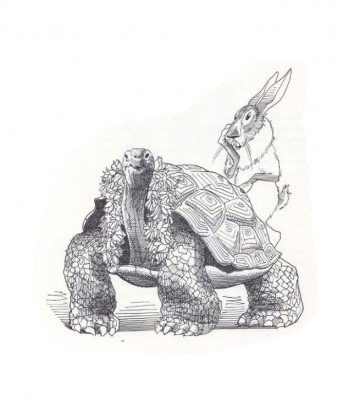

They don’t get any more gorgeous than this turtle and rabbit.

Commentary &Daily post 16 Jul 2010 06:45 am

Drips and Drabs

- The totally-lacking-courage, Cartoon Network is finally realeasing the official DVD of the first season (mind you it’s only the first season) of John R. Dilworth‘s masterful series Courage the Cowardly Dog.

- The totally-lacking-courage, Cartoon Network is finally realeasing the official DVD of the first season (mind you it’s only the first season) of John R. Dilworth‘s masterful series Courage the Cowardly Dog.

The DVD hits the stores on January 20, 2010 some 11 years after it was first aired. How embarrassing for a network that claims it has to move into live action to finally get strong. If they had taken advantage of the brilliant properties in their hands – all those under the original creative team – they might have been a bit more original, successful, and useful. Now it’s just a network without a real name.

The Sundance Channel has released ANIMATION BIZARRO 2 – a collection of seven animated shorts made by some of the most provocative and unique Canadian animators/artists:

- Each film was chosen for its diversity, quality and individuality. The episodes provide a range of color and bizarre visions of the world as depicted through a variety of animation styles including: cel, paper cut outs, stop motion and CGI. The films touch on a variety of moods (funny, touching and sardonic).

The series features the work of established veterans like Mad Magazine legends Al Jaffee and Sergio Aragones, and emerging animators like Brandon Blommaert and Sean Stoops. Their work, juxtaposed with our other featured artists like Robbie Conal, Steve Brodner and the emerging new stars of the Hot House program, really tells a bigger story of the progression of modern humor, cartooning, political satire and comedy in art. We think this will be

both fascinating and thoroughly entertaining for the diehard fans and

general audiences as well.

Following the launch, Sundance will add new videos, images and interviews to the Animation Bizarro site on each remaining Monday throughout the month, so please keep checking the site for additional content.

- Bill Benzon continues his study of Nina Paley’s feature length film, Sita Sings the Blues. In his current essay on the blog New Savannah, he writes about Ritual in Sita Sings the Blues, Part 1.

- Bill Benzon continues his study of Nina Paley’s feature length film, Sita Sings the Blues. In his current essay on the blog New Savannah, he writes about Ritual in Sita Sings the Blues, Part 1.

It’s nice to see Nina’s film taken so seriously. It should outlive its shelf life.

- Tom Hachtman’s Gertrude’s Follies got a nice writeup in The Comics Journal. That strip deserves all the attention it can muster. In my opinion, Tom’s the equivalent of a modern day Milt Gross, only he has received enough praise.

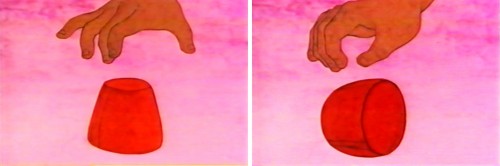

Animation &Frame Grabs &SpornFilms 15 Jul 2010 07:08 am

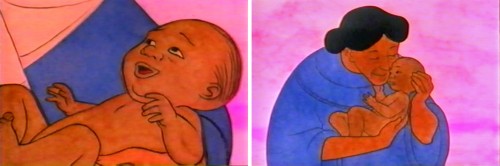

Child Development

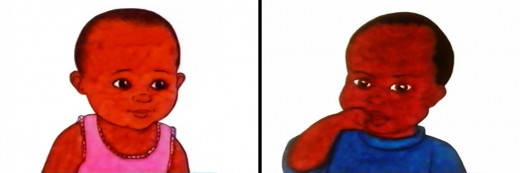

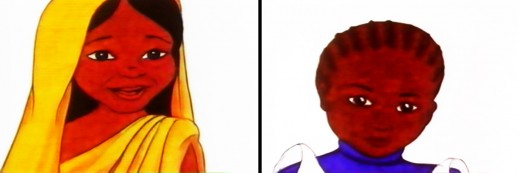

- I want to give some attention to a series of films we did for UNICEF back in the 90′s. There were four films which focussed on Child Development, trying to teach parents in the Third World how to take care of their children in the first eight years of development.

These films were brought to me by one, Cassie Landers. A well trained educator and an employee of Unicef where she promoted child development training and was hoping to use film to get the message across to the Third World.

Primary to these films was to get the point across that females deserved as much attention, including education, as the boys did. This is a major problem throughout the world, and UNICEF has done an entire series specifically for India about it.

Our aim was to encourage good diet, good behavioral practices and, again, the importance of a good education. The four films were ultimately combined with some live action footage of T. Berry Brazelton talking with children and introducing each of the four segments.

Hillary Rodham Clinton, as First Lady, introduced the entire 1/2 hr. show.

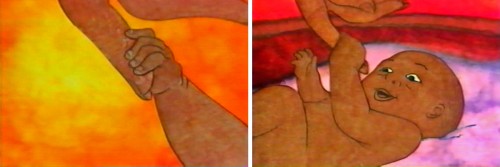

Here are some frame grabs from about 2/3 the scenes of the first film, Off To A Good Start.

1

1

2

2

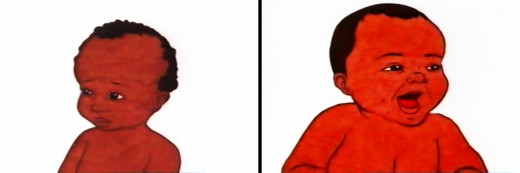

After the UNICEF logo, the film started with a montage of children’s faces.

3

3

I’ve compiled about a third of the faces.

4

4

The camera continually moves in on the faces while …

5

5

… constantly dissolving to the next setup.

6

6

This was the opening to all four of the films.

7

7

It was accompanied by narration by Celeste Holme describing the films about to be seen.

8

8

The narration was written by UNICEF Producer/educator, Cassie Landers.

Sue Perotto drew all of the children’s faces for the opening. She had the right sweet look for the children and the many faces we’d be seeing in a very short amount of time. I knew Sue could keep it interesting and I depended on her – with good reason.

10

10

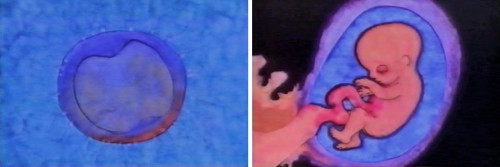

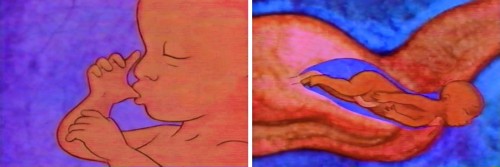

The first film started with prenatal care.

11

11

Giving a very short the child in the womb.

12

12

Right through to the actual birth.

13

13

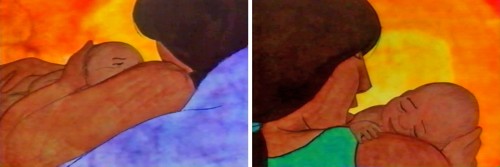

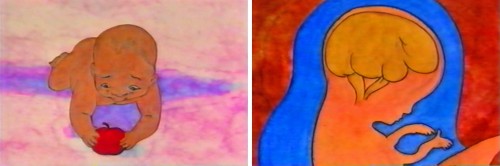

Then it jumps to the first year of development.

14

14

The art style was designed after Matisse’s Moroccan paintings.

15

15

He had a very primitive set up, colors with

earth-toned characters dominating their paintings.

16

16

We tried to reproduce the feel of these paintings

allowing the texture of the paintings to run and bleed.

18

18

This was all done pre-computer days, so all art was

painted on paper, then cut out and pasted to cels.

19

19

It was all shot on camera by Gary Becker at his FStop Studios.

Masako Kanayama and Stephen MacQuignon were able to bring a smooth look to the wildly varing colors.

It was designed to look like Matisse’s African period, and I think it did.

20

20

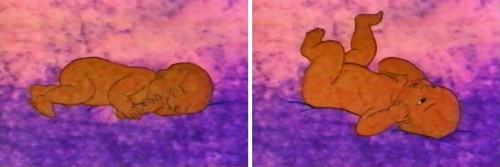

The first year continues with similar setup.

21

21

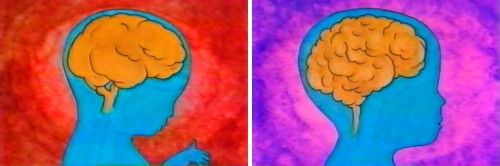

After showing some advanced activity . . .

22

22

. . . we show how the brain has started to . . .

23

23

develop enormously in this first year.

24

24

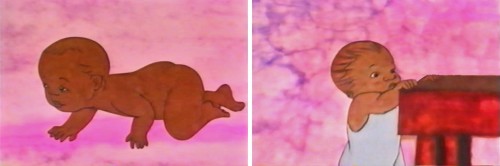

The child learns to get up and crawl.

25

25

From here she learns to walk.

27

27

Then he learns to play more sophisticated games . . .

28

28

. . .utilizing tools that require more dexterity and thought.

Directed by Michael Sporn

Produced and Written by Cassie Landers EdD, MPH

Narrated by Celeste Holme

Music by David Evans

Production Coordinated by Masako Kanayama

Backgrounds by Jason McDonald

Edited by Ed Askinazi

Photography by FStop Studio – Gary Becker & Bob Bushell

Technical Consultant Marc Borstein Nat’l Inst of Health, Bethesda MD.

Office Manager Marilyn Rosado

Animation by Rodolfo Damaggio, Sue Perotto, Michael Sporn

Rendering by Christine O’Neill, Matt Sheridan, Stephen MacQuignon, Masako Kanayama

Special Thanks to Nigel Fisher, Deputy Regional Director,

UNICEF Regional Office for the Middle East and Africa

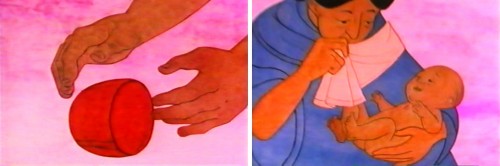

Animation &Disney 14 Jul 2010 07:00 am

P&W-Kimball Scene – 5

- This is the final part of this level of animation. We’re posting the scene from Peter and the Wolf animated by Ward Kimball of the three hunters after the wolf. There are a lot of drawings, so posting them has had to be in five segments.

Next week, the level where the littlest hunter separates from these two bigger guys.

As with past posts, I start with the last drawing from last week.

180

180

The following QT movie represents all the drawings posted to date.

I exposed all drawings on ones.

Right side to watch single frame.

To see the past four parts of the scene go to: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, http://www.michaelspornanimation.com/splog/?p=2298>Part 4, Part 5http://www.michaelspornanimation.com/splog/?p=2298>Part 5.

Many thanks go out to John Canemaker for the loan of the scene to share.

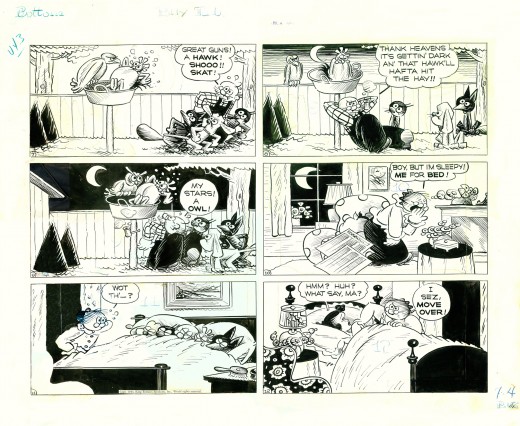

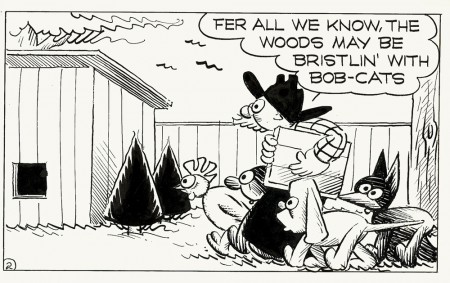

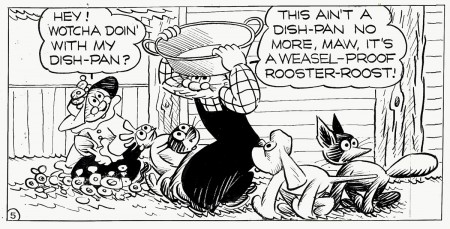

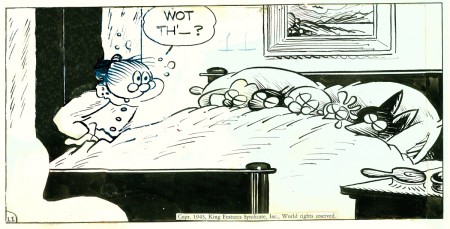

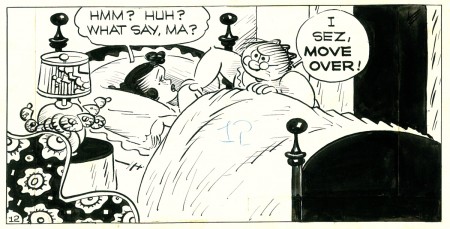

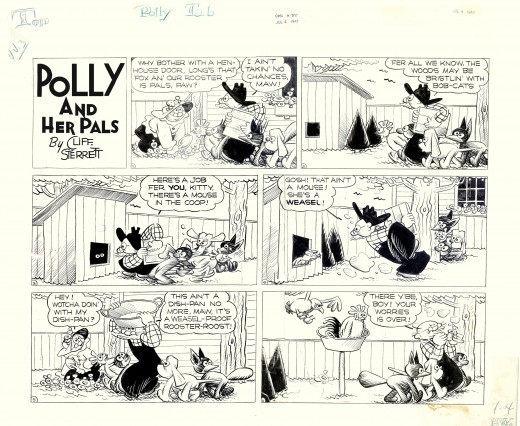

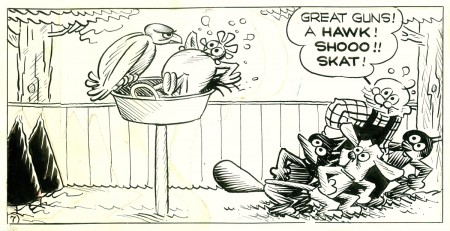

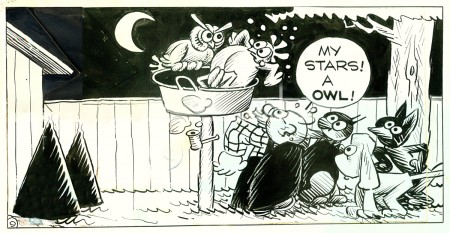

Comic Art &Illustration 13 Jul 2010 06:55 am

Polly Original

- I’ve been posting some great comic strip and comic book strips here in the last two weeks. By far, my favorite strip is Polly and Her Pals by Cliff Sterrett. I haven’ yet posted the original I own. It’s a Sunday page from March 1943.

The art is large sized and comes in two halves. I’ll post it actual size and add a couple of cut ins so that the art can be seen a little better.

I’ve had to do some photoshop touchup since the original got a bit of water damage during a flood in my studio.

(Click any image to enlarge.)

7

7

White paper covers more trees on the left of this panel.

You can see the shapes coming through.

9

9

This panel is composed of a lot of pasted on bits of paper.

All the glue is trying to fall off, and the papers are delicate,

especially on the roof of the building, left.

Books &Disney &Illustration &Layout & Design &Mary Blair 12 Jul 2010 07:03 am

Mary Blair – 1

(Click any image to enlarge.)

- I received a magnificent gift, recently, from John Canemaker. It’s a book that was published in Japan that intensely focusses on the work of Mary Blair, the brilliant artist who

designed and stylized many Disney’s golden films.

designed and stylized many Disney’s golden films.

The book is chock-a-block with images, and even though most of the writing is in Japanese, the book is a glorious item to read through – just for the pictures. Fortunately, there is identification in English under all of the images. John Canemaker also has a wonderfully written Foreward in the book.

I’m going to make a couple of posts selecting some images that I found exciting and relevant to Ms. Blair’s career. Included, of course, will be some paintings and designs by her husband, Lee Blair, and her brother-in-law, Preston Blair.

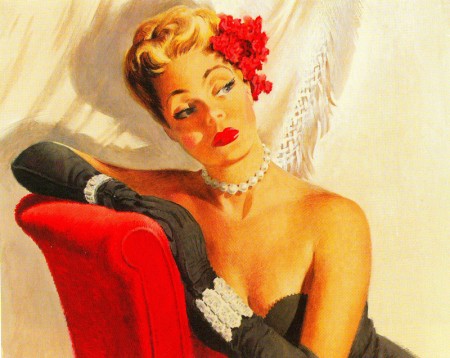

I’m sure a lot of the paintings were chosen to act as a comparison to some of the animated segments done by the trio. Take, for example, “Woman with Red Flowers in Hair” by Preston Blair.

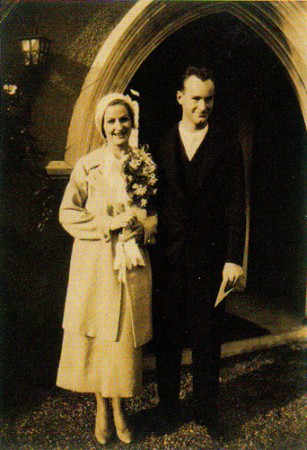

This post will attend to the pre-Disney paintings of all three artists.

Wedding Photo – March 3, 1934

Mary and Lee Blair

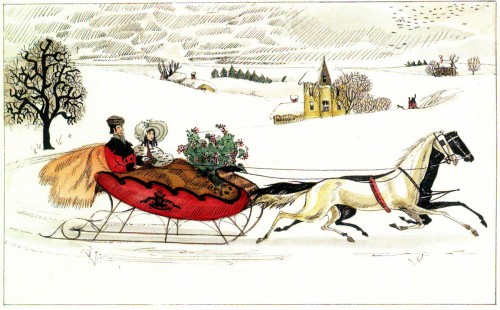

Mary Blair – Couple in Snow Sled

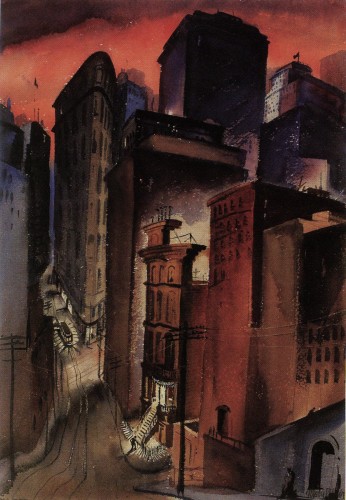

Mary Blair – San Francisco Nights

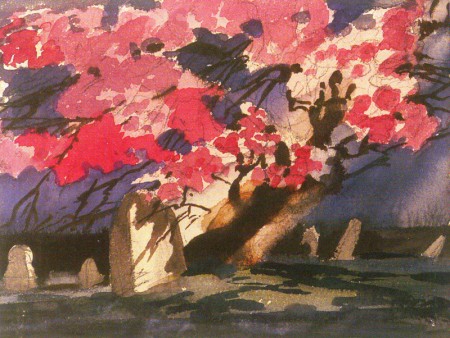

Mary Blair – Landscape of Trees

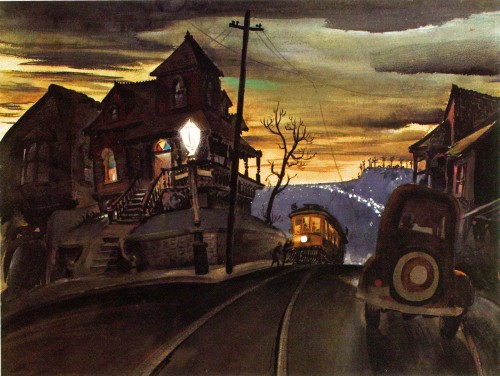

Preston Blair – Night Street Scene with Cable Car

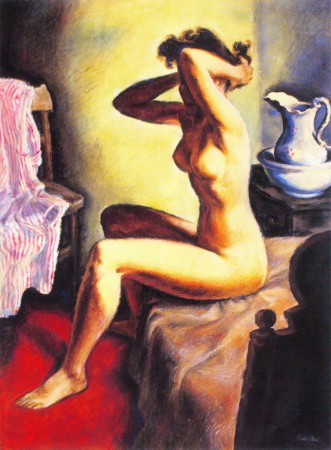

Preston Blair – Female Nude Preening

May I also remind you that John Canemaker has a wonderful book available in the US. The Art and Flair of Mary Blair is still for sale on Amazon.