Search ResultsFor "Ambro Raggedy Ann"

Books &Commentary &John Canemaker &Photos 28 Apr 2013 05:55 am

Raggedy Ann Photos

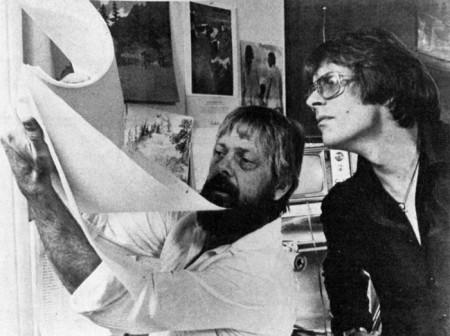

- John Canemaker recently loaned me a stash of photos of the Raggedy Ann crew. These were pictures that were used in his book on the “making of”. It was a better book than movie (as they often are). There are also some photos that didn’t make it to the book. John Canemaker shot all the photos, himself and all copyright belongs to him.

I thought I’d post the pictures and add some comments that pop off the top of my head. Hopefully, a couple of interesting stories will show up in my memories.

There are enough photos that it’ll probably take about three posts to get them all in. The next two Sundays are booked, I’d guess.

1

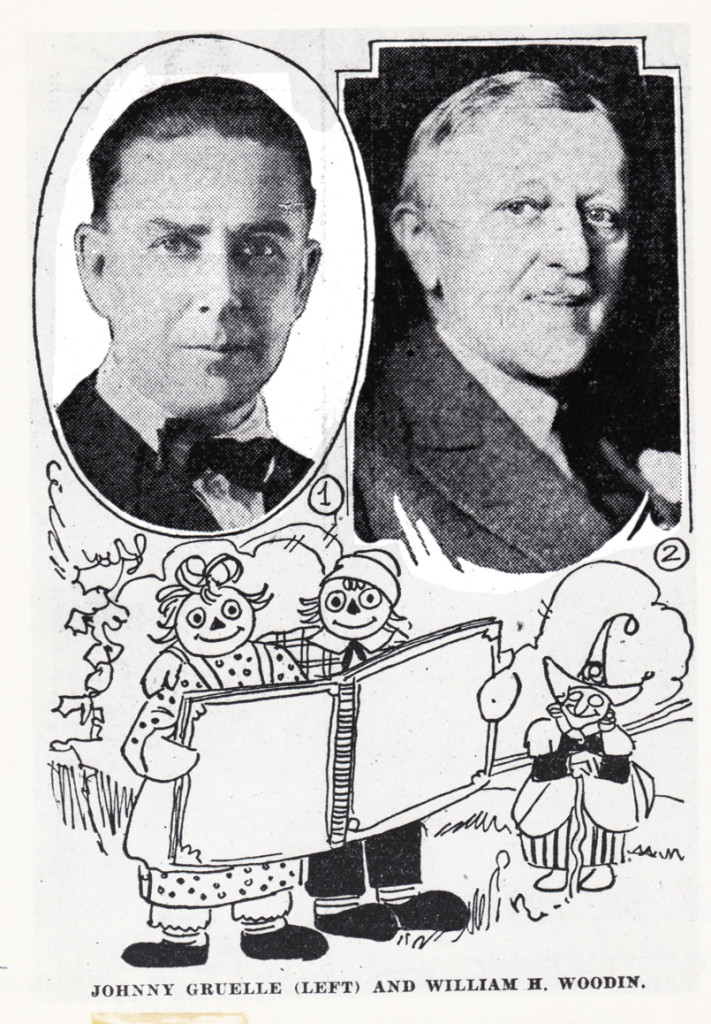

1Johnny Gruelle (artist, writer) and William H. Woodin (song writer)

Dec.28, 1930 Indianapolis Star – “Raggedy Ann’s Sunny Songs”

This was apparently a theatrical piece Johnny Gruelle

put together with his very successful characters.

2

2

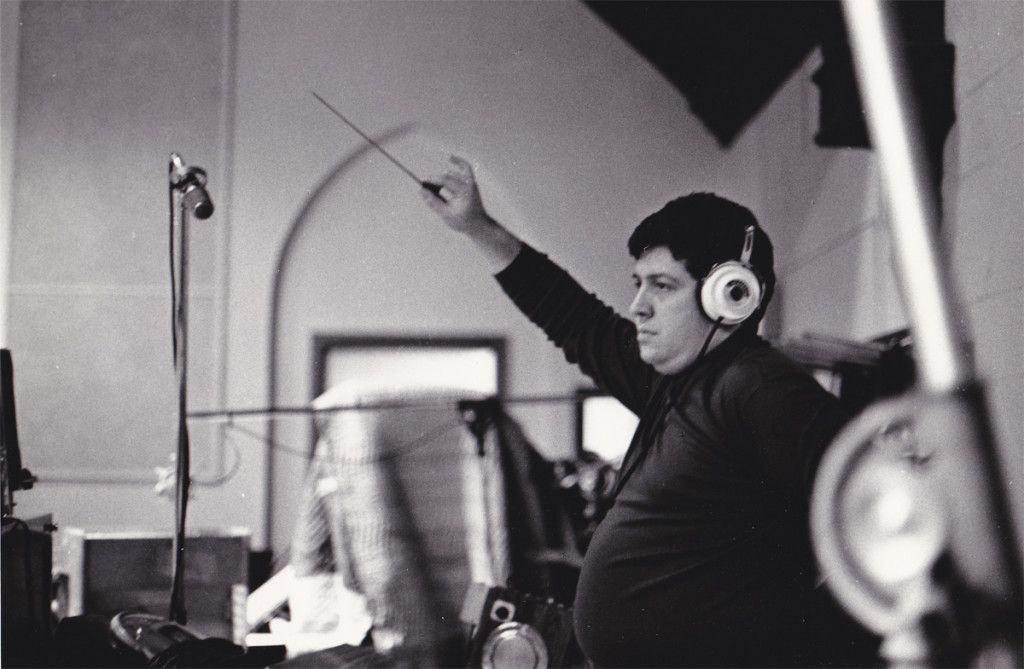

It all started with Joe Raposo, the composer of “Bein’ Green”

and many other hit Sesame Street songs. He wrote a musical for “Raggedy Ann

and Andy” and was made to see that it would make a wonderful animated musical.

3

3

He wrote a lot of songs for the slim script and they prerecorded

the songs for the animation. We lived with a soundtrack of about

a dozen musicians playing this very nice score to the delicate voices

that sang the tuneful pieces.

4

4

We heard this at least once a week as the animatic/story reel

grew into a full animated feature shot completely in Cinemascope.

5

5

When the final film was released, that 12 person orchestra

became 101 strings and a big over-polished sound track.

No matter where you went the music was there and in the way.

It was too big, and the movie was too small. It was bad.

The track was incredibly amateurish. The composer had too much control.

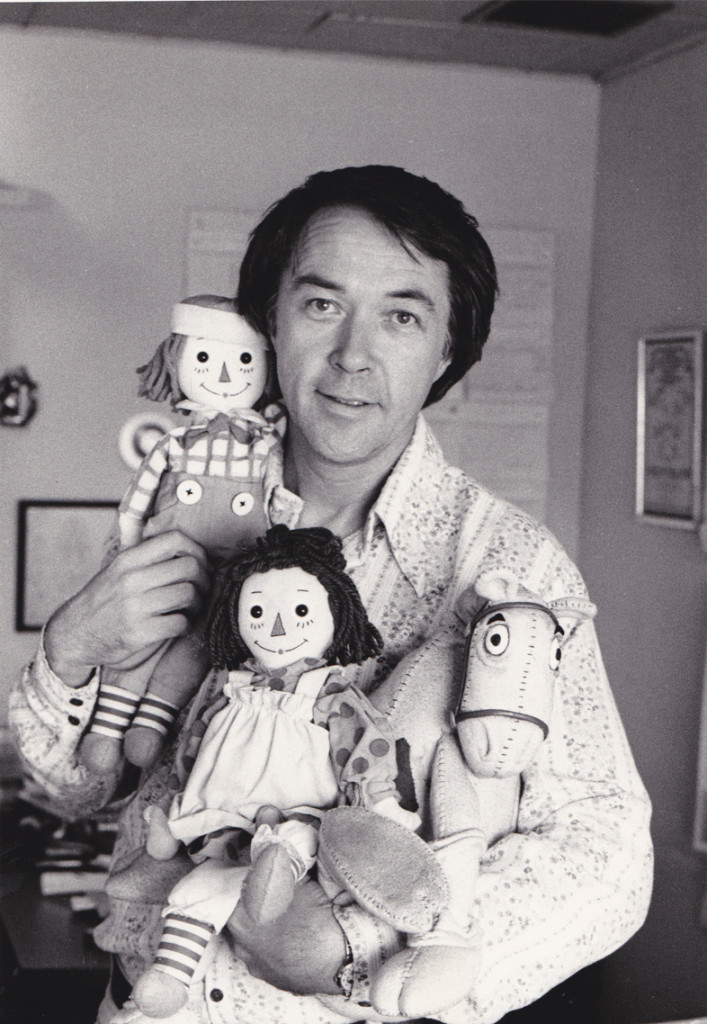

6

6

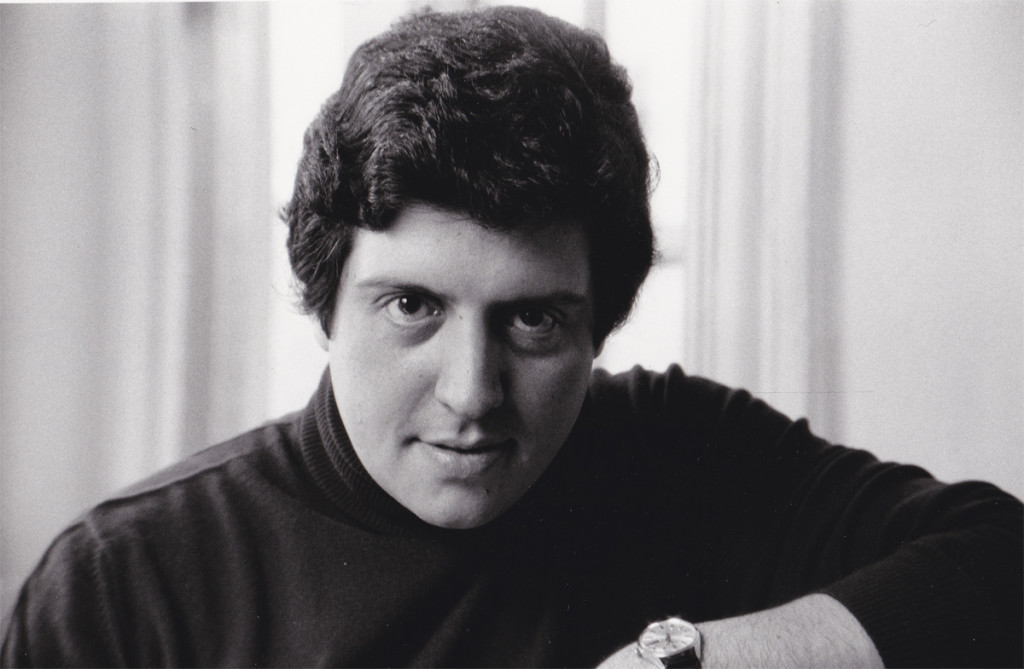

This was Richard Horner. He was one of the two producers of the film.

Stanley Sills (a Broadway producer and Beverly’s brother) was the

other producer who didn’t know what he was doing.

They represented Bobbs-Merrill who owned the property.

I really liked Mr. Horner. We met again a number of years later

when Raggedy Ann was distantly behind us. I’d offered to take Tissa to church,

one Easter Sunday; Richard Horner and wife were there. He asked to meet with me.

He sought advice on some videos of artists and their work that he was producing,

and hoped I could offer my help in leading him to some distributors.

7

7

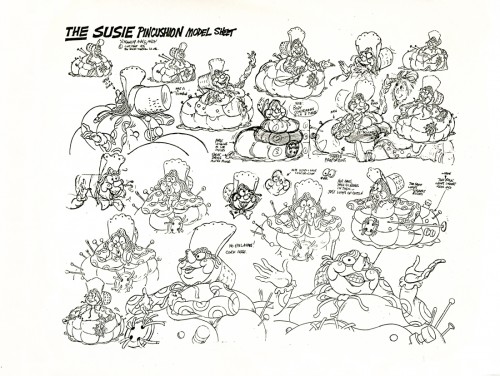

This is one of the dolls in the play room,

Susie Pincushion. She was charming.

8

8

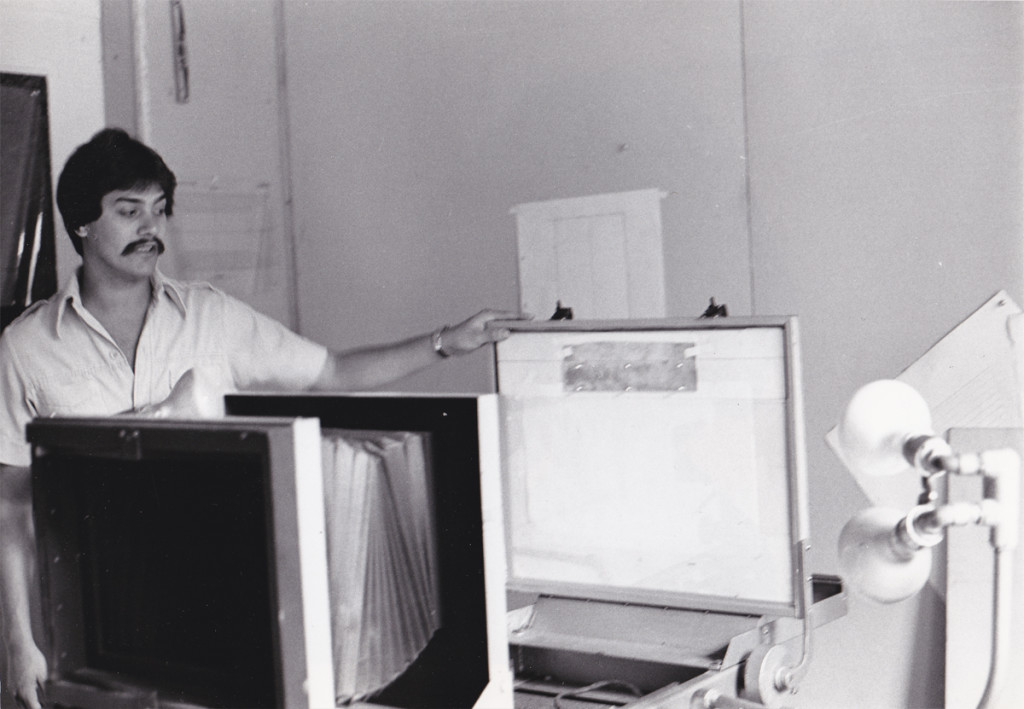

This is Cosmo Pepe; he was one of the leaders of the Xerox department.

It was Bill Kulhanek‘s department, but Cosmo really did great work.

They had this room-sized machine that they converted drawings into cels.

It was all new to NY, and the whole thing was so experimental.

Especially when Dick decided to do the film with grey toner rather than black.

The film always felt out of focus to me (even though it wasn’t.)

In the end when they rushed out the last half of the film, Hanna Barbera

sub-contracted the Xeroxing, and it was done in a sloppy and poor black line.

9

9

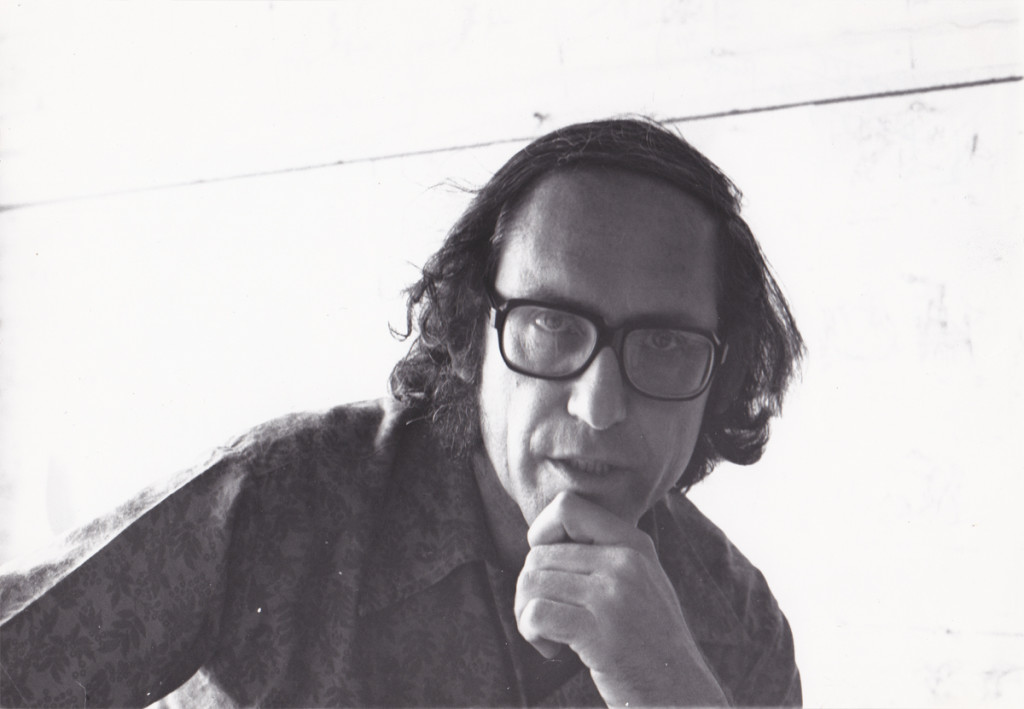

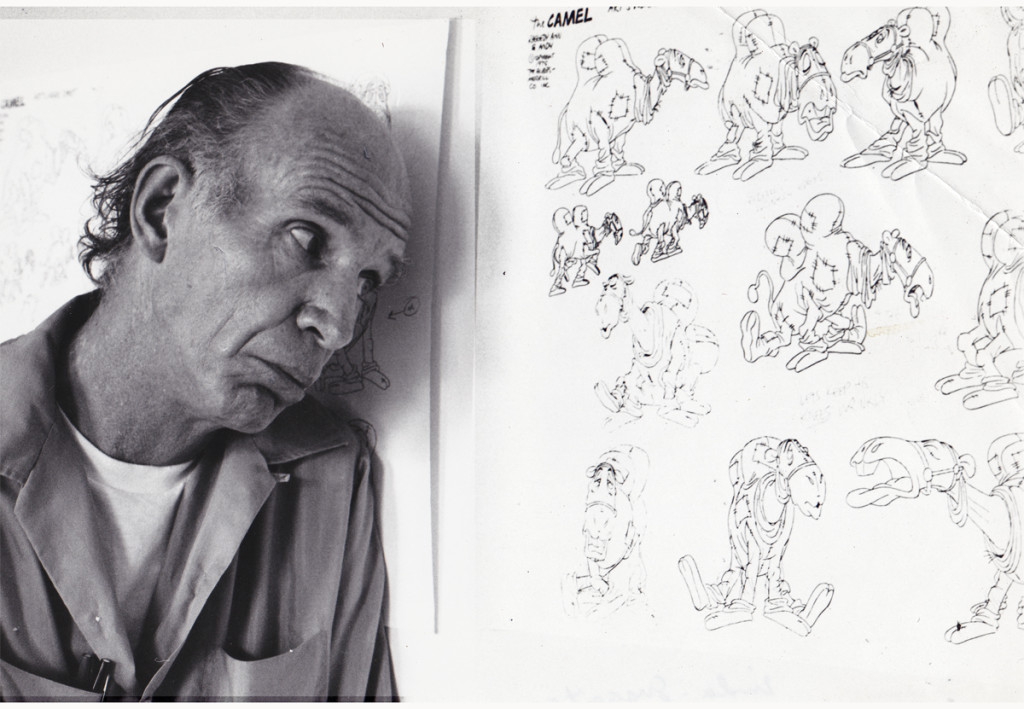

This is Corny Cole. He was the designer of the film, and all the great art

emanated out of his Mont Blanc pen nib. Or maybe it was a BIC pen.

Whatever, it was inspirational.

I wrote more about him here.

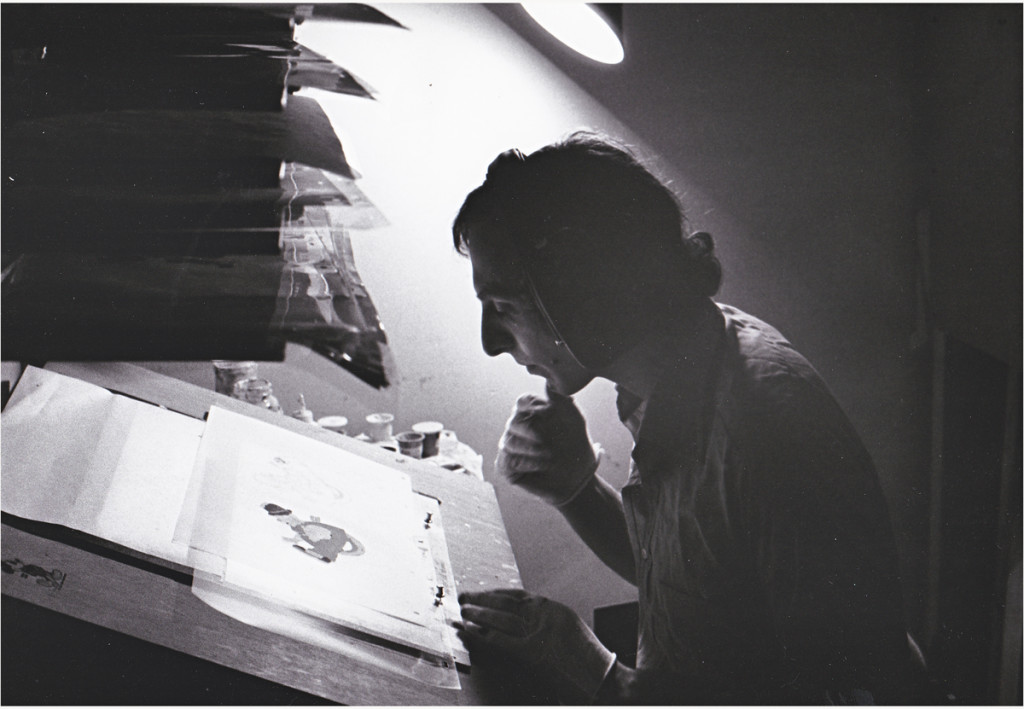

10

10

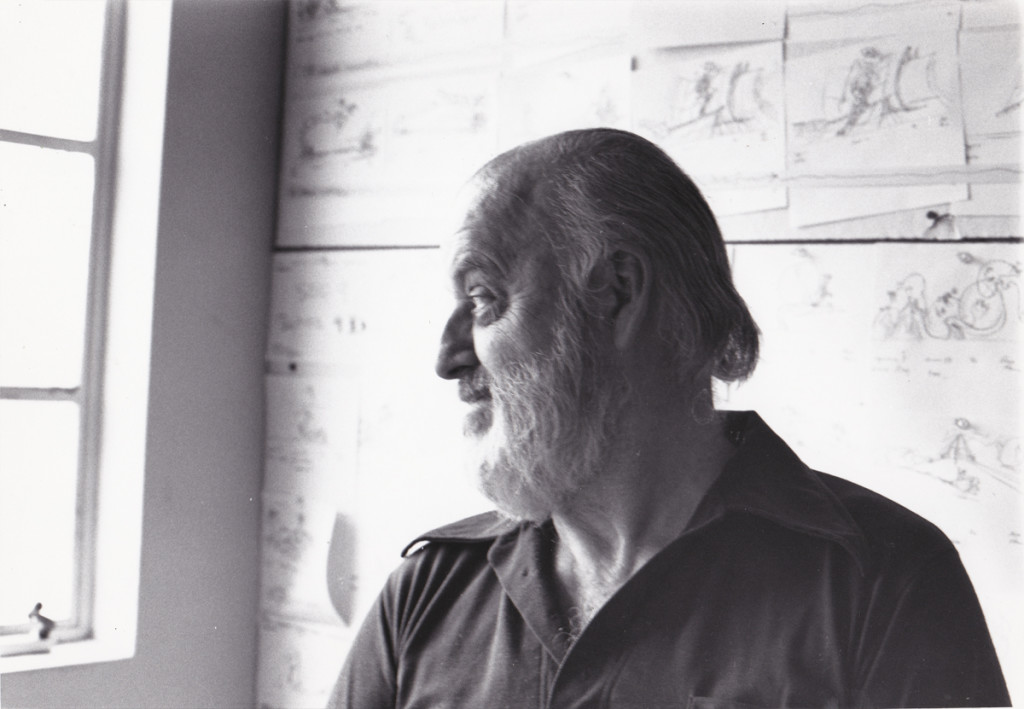

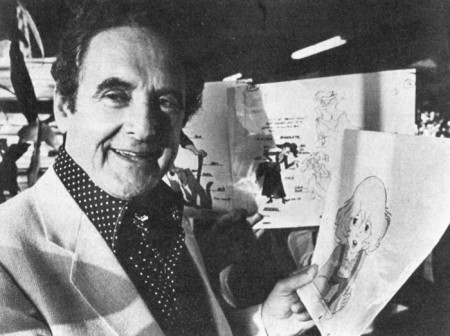

The gifted and brilliant animator, Hal Ambro. Can you tell that

I admired the man? I wanted badly to meet him during this production,

but that never was to happen. Now, I can only treasure his work.

11

11

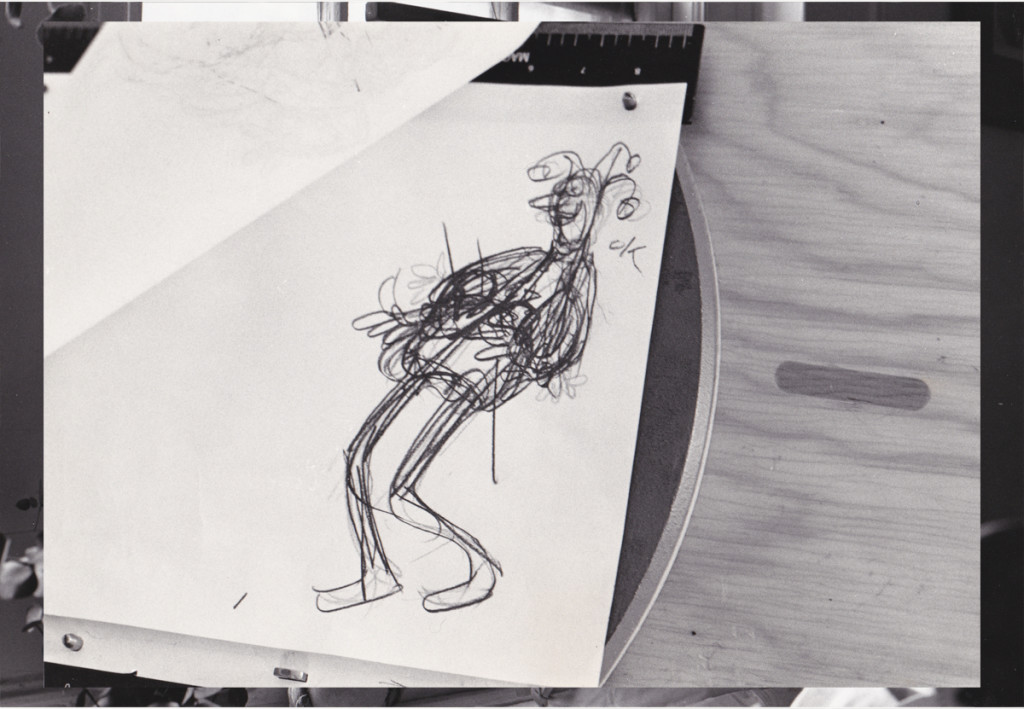

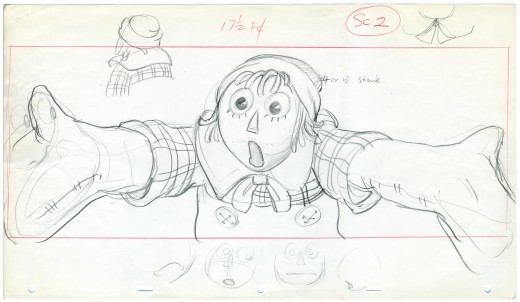

This is a very rough planning drawing that Grim Natwick did on

the Jack-in-the-Box he animated. See the scene here.

12

12

Here’s a close up of that very same drawing.

13

13

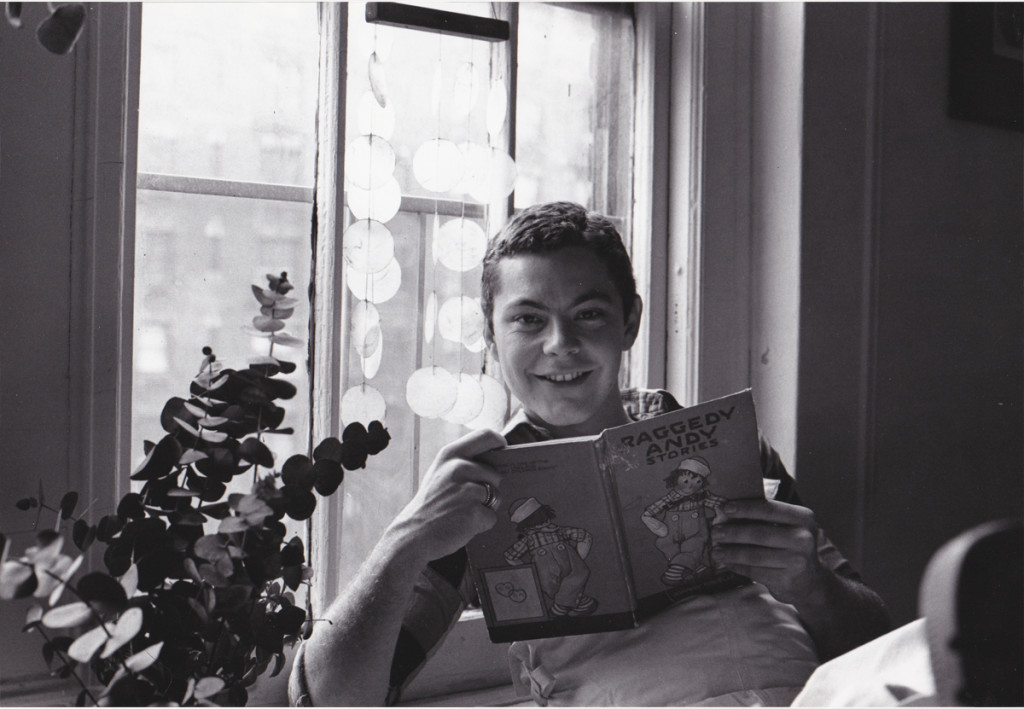

Mark Baker did the voice of Raggedy Andy.

He’d won the Tony Award as Best Featured Actor in the musical, Candide.

14

14

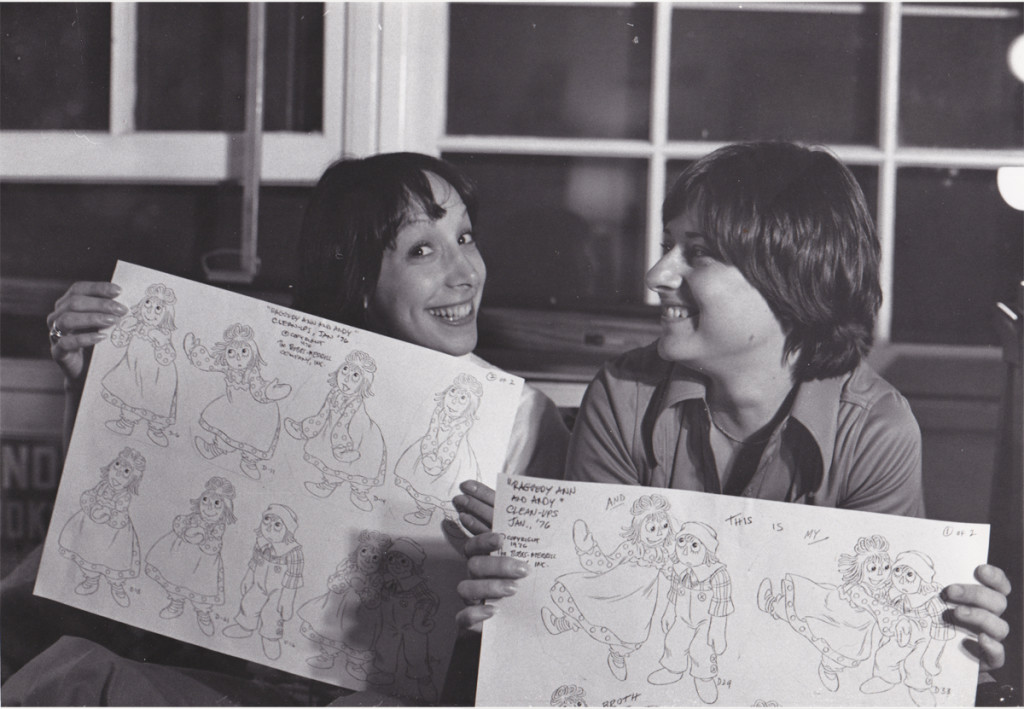

Didi Conn, the voice of Raggedy Ann, with Chrystal Russell, an animator

of Raggedy Ann. She backed up Tissa David who was the primary actor for

that character and did most of the film’s first half. Chrystal did many

scenes in the first half and most of the second.

She had a rich identifiable style all her own.

15

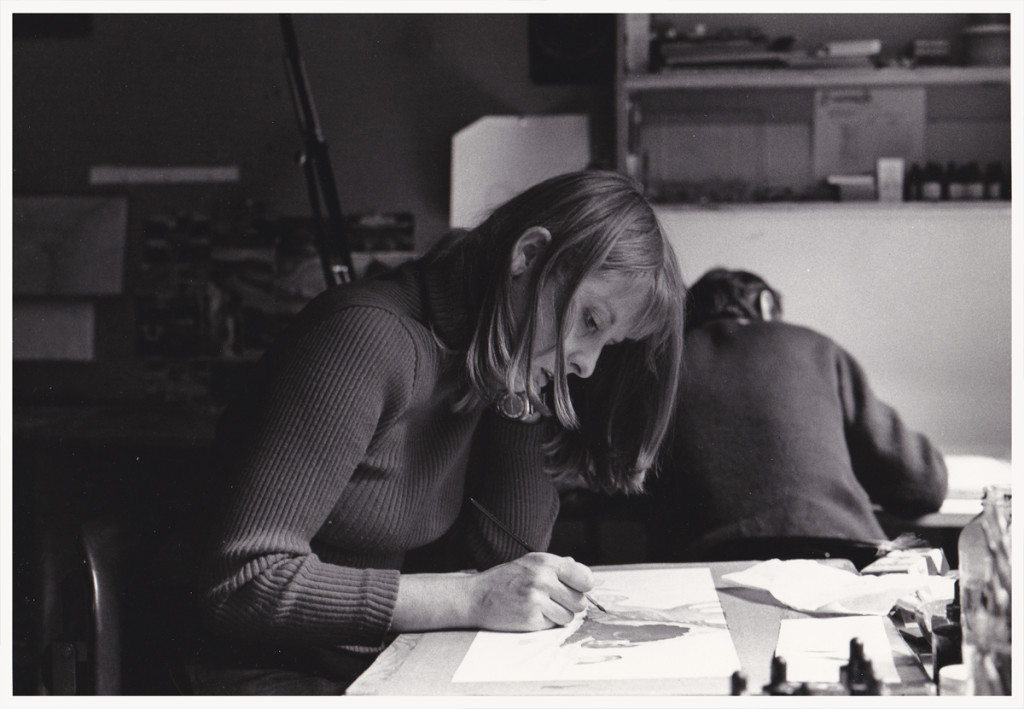

15

Sue Butterworth, head of the BG dept who designed the watercolor style

of the film. Michel Guerin, her assistant, can be seen in the rear.

Bill Frake was the third part of that BG department.

16

16

Painter, Nancy Massie. A strong and reg’lar person

in the NY animation industry. She’d been working forever for a reason.

On the average, I spent about an hour a day down in the Ink & Pt dept.

Often they had problems to resolve with some animator’s work. Either the

exposure sheets were confusing or they didn’t match the artwork, or there

was some question that they found confusing. My being available made it

helpful to them, and I did so without hesitation.

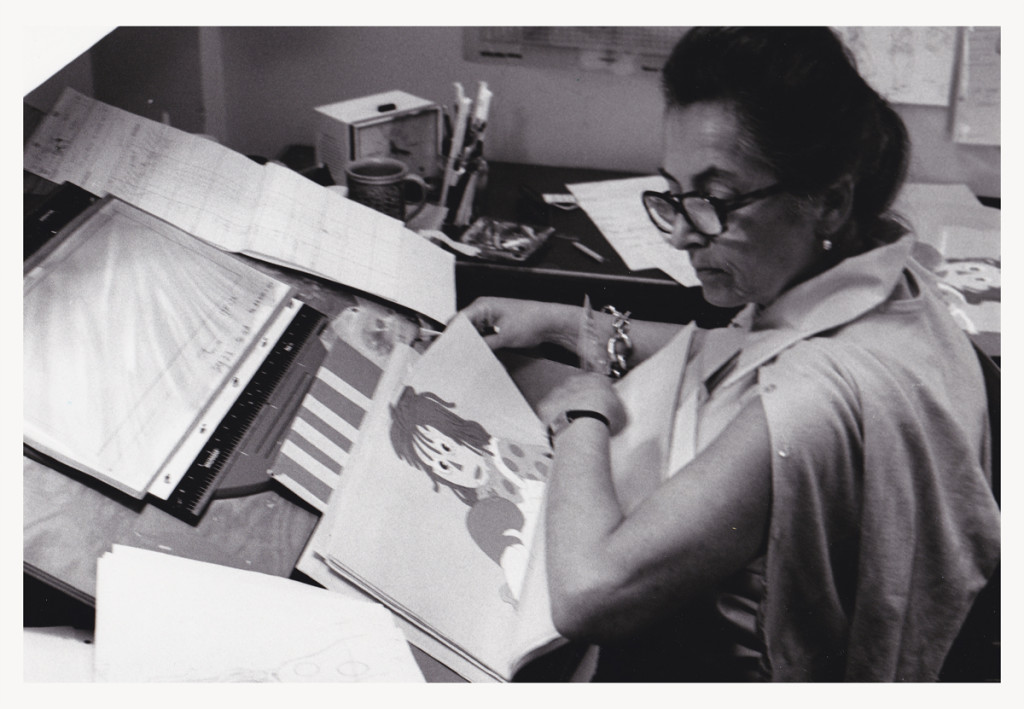

17

17

Checker, Klara Heder. Another solid person

within the NY industry.

Generally, before a scene left my department for the I&Pt dept., I’d

have studied the exposure sheets and felt I knew the scenes before

they were handed out to the Inbetweener or Assistant. It meant taking

a lot of time with the work in studio so that I was not only prepared

to answer questions of a checker but the Inbetweener as well.

18

18

Sorry I don’t know who this is. If you have info,

please leave it for me. For some reason, I’d thought

he was an inbetweener (which would’ve made it odd for

me not to recognize him by name.) Apparently he’s a painter.

19

19

Carl Bell was the West Coast Production Coordinator.

We spoke frequently during the making of the show.

When I left the film, I went to LA for a couple of weeks.

Chrystal Russell threw a small party for me, and Carl came.

(I think he might have brought Art Babbitt, who was there.)

The group was small enough that we could have a talk that we all

participated in. We talked for some time (though not about

Raggedy Ann.) It was great for me.

20

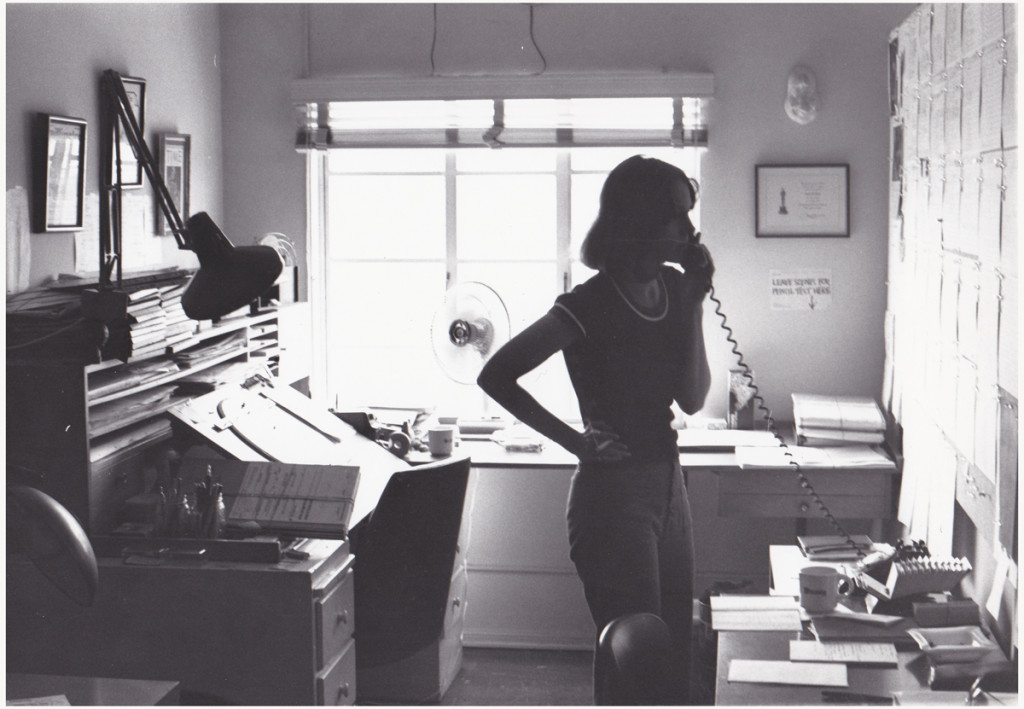

20

Jan Bell, Carl’s wife, was the West Coast Office Manager.

21

21

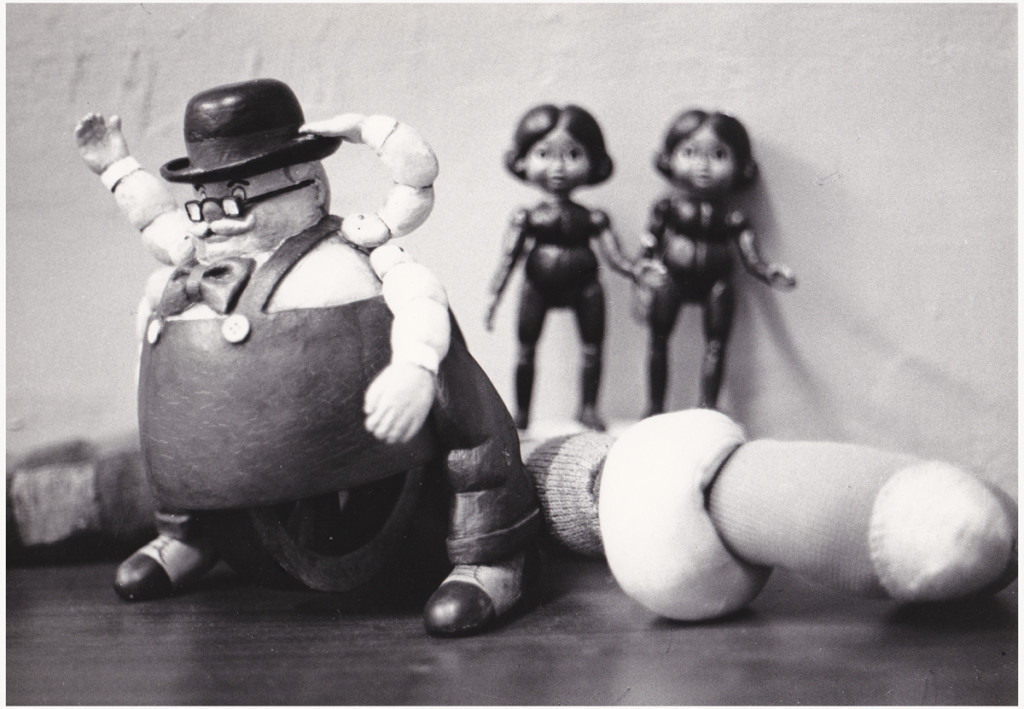

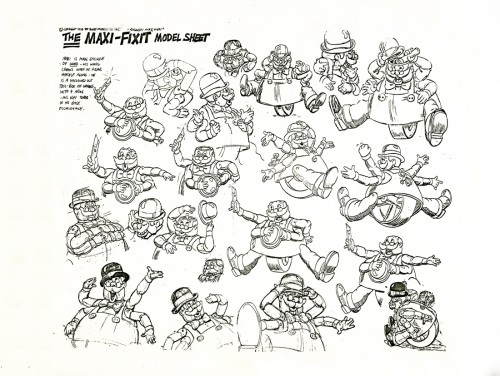

Maxie Fix-it. This was a great doll that wound up to get the legs going.

He rolled around the floor beautifully. The “Twins” in the back were animated

by Dan Haskett. though I’m not sure they gave him credit for it. I was a bit

embarrassed by these characters. They were just a naked bit of racism running

about our cartoon movie for very young children.

22

22

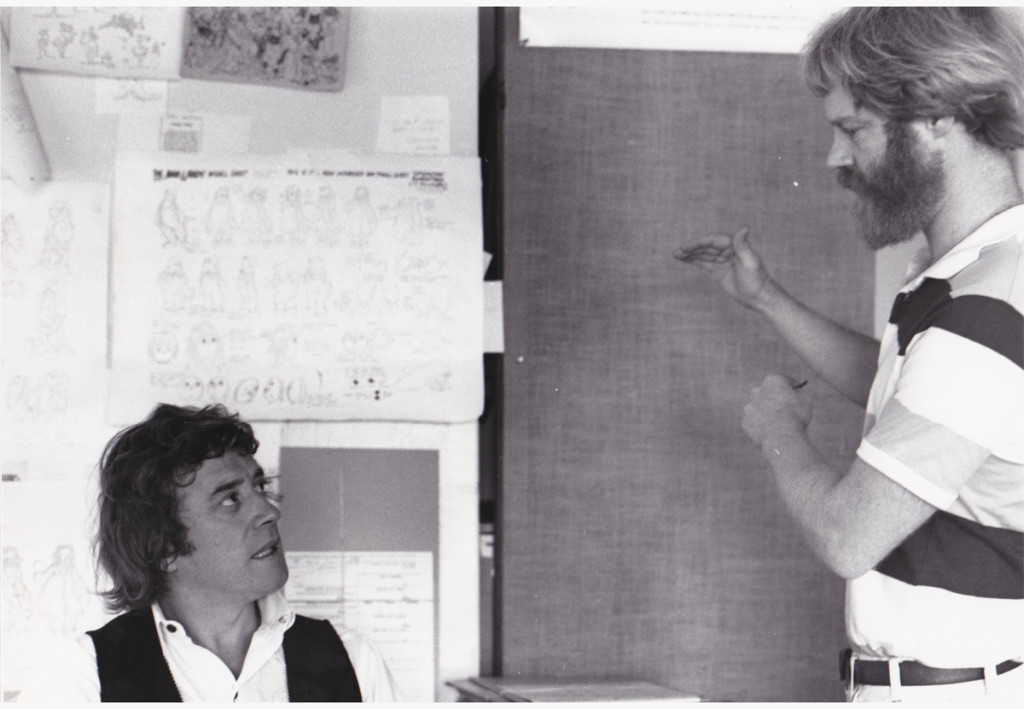

Gerry Potterton (left) and John Kimball (right).

Gerry was one wonderful person. I always enjoyed spending time with him.

He produced/directed a number of intelligent, adult animated films.

This includes an animated Harold Pinter‘s Pinter People.

After Raggedy, I tracked Gerry down to get to see Pinter’s People. It was

rather limited but full of character. Gerry knew how to handle the money

he was given, unlike some other directors.

John Kimball was, at the time, not in the caliber of Babbitt or Ambro or

David or Hawkins or Chiniquy. However, he did some imaginative play

on a few scenes which were lifted whole from strong>McCay’s Little Nemo

in Slumberland. One of these scenes I animated but was pulled

from it before I could finish it. I had too much else to do with the

tardy inbetweens of Raggedy Ann (an average of 12 drawings per day)

and the stasis of the taffy pit (an average of 1 inbetween per day).

Too many polka dots on Ann and too much of everything in the pit.

23

23

Fred Stuthman, the voice of the camel with the wrinkled knees.

He did add a great voice for the camel, though for some reason

I remember his being a dancer, predominantly.

All photos copyright ©1977 John Canemaker

.

Commentary 11 Mar 2013 02:09 am

European Animation

I know I’ve written about some of this stuff before (repeatedly), and I hope my take on it here is a bit different. At least I’m leading somewhere different, so please have a bit of patience with the opening.

- When I was a kid, animation was in the dark ages for the general public. By that, I mean there wasn’t a hell of a lot of material available to allow you to know how it was done or learn how to do it. There were maybe a dozen or so books available.

- -

Of course the 40s Rob’t D. Feild book, The Art of Walt Disney. Some great information but not many illustrations. What are there are GREAT.

Of course the 40s Rob’t D. Feild book, The Art of Walt Disney. Some great information but not many illustrations. What are there are GREAT.

- The Preston Blair book, Animation, good and cheap. Very helpful for an amateur like me.

- Halas and Manvell‘s The Technique of Film Animation had more to do with animation as done in Europe, but it is extraordinarily helpful.

- Eli Levitan, an animation cameraman, had written several books. Animation Art in the Commercial Film is one of the better books.

There were a few others. My local library had them all, and I borrowed them endlessly and just about memorized them all. I owned the Preston Blair book (of course and my parents bought the brand new Bob Thomas Art of Animation for me Christmas 1958.

On ABC you had the Disneyland TV show which became The Wonderful World of Color when it moved to NBC. The Mighty Mouse Show was the staple on Saturday morning. Local channels featured Popeye and B&W Warner Bros cartoons.

I was completely intrigued with some silent cartoons that were run on the local ABC affiliate on early Saturday mornings. Every once in a while a sound Van Buren cartoon would pop up or a Harman-Ising MGM cartoon..

The show that also intrigued me was this horrible “Big Time Circus” starring Claude Kirschner (normally a VO announcer) as a ringmaster who talked to a $5 clown hand-puppet named “Clowny.” They showed cartoons, some B&W Terrytoons with Barker Bill and other early 30s things. They also showed a lot of foreign cartoons badly dubbed into English. They even had Russian features like The Golden Antelope serialized. They had a horrible title on the top of the film and a “The End” title pasted onto the end of the film. I used to tune in to see these B&W European and Russian cartoons. They moved so differently from what I was used to with the cartoons from the US. At 12, I could definitely see the difference and watched closely.

The show that also intrigued me was this horrible “Big Time Circus” starring Claude Kirschner (normally a VO announcer) as a ringmaster who talked to a $5 clown hand-puppet named “Clowny.” They showed cartoons, some B&W Terrytoons with Barker Bill and other early 30s things. They also showed a lot of foreign cartoons badly dubbed into English. They even had Russian features like The Golden Antelope serialized. They had a horrible title on the top of the film and a “The End” title pasted onto the end of the film. I used to tune in to see these B&W European and Russian cartoons. They moved so differently from what I was used to with the cartoons from the US. At 12, I could definitely see the difference and watched closely.

When I started collecting 16mm films I picked up a bunch of these shorts. The timing didn’t get any better.

On my second day at the Hubley Studio, I met the notorious Tissa David who dug into me quickly for my bad inbetweening. She offered to teach me after hours, which I certainly jumped to accept. In that first contact with her, I mentioned that I had a potential job offer from Richard Williams and I might go to England. She immediately said to me, “Oh, please don’t go there. Stay here. Only the Americans know how to animate properly.” After all those years of watching Russian and European cartoons, I understood what she was saying. (I was also working for my real hero, John Hubley, so I had no real plans to go anywhere.) Dick Williams came to me a couple of years later with Raggedy Ann. By then, I was knowledgeable enough to run the Asst. & Inbtwng dept – about 100-150 people.

But then Dick Williams was changing everything. He was teaching his people in England how to animate the way Disney people did it. He brought those people into his studio to teach: Art Babbitt, Ken Harris, John Hubley, Grim Natwick, and others. I believe Williams changed animation throughout Europe. Mind you, the problems of all those years of history is still there, but it’s enormously better.

What do I call “European Animation”? Well, it’s all about the timing. The characters often move at such an even speed that there is no sense of weight or real character movement. Basically, all characters move the same. The Golden Antelope is all rotoscoped, so the movement is on ones and all traced off the live action. You can tell when it’s not; there’s a sameness in the motion. It’s almost like there are no extremes just motion.

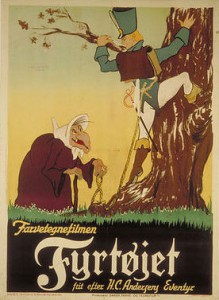

In Europe’s first attempt to imitate the US in a feature, The Tinderbox a 1946 film from Denmark, they were obviously trying to imitate the Fleischers of Gulliver’s Travels. Wild distortions and odd extremes but a lot of the evenly spaced timing. Consequently, with the distorted extremes moving in and out of position at an even pace, it’s doubly peculiar.

In Europe’s first attempt to imitate the US in a feature, The Tinderbox a 1946 film from Denmark, they were obviously trying to imitate the Fleischers of Gulliver’s Travels. Wild distortions and odd extremes but a lot of the evenly spaced timing. Consequently, with the distorted extremes moving in and out of position at an even pace, it’s doubly peculiar.

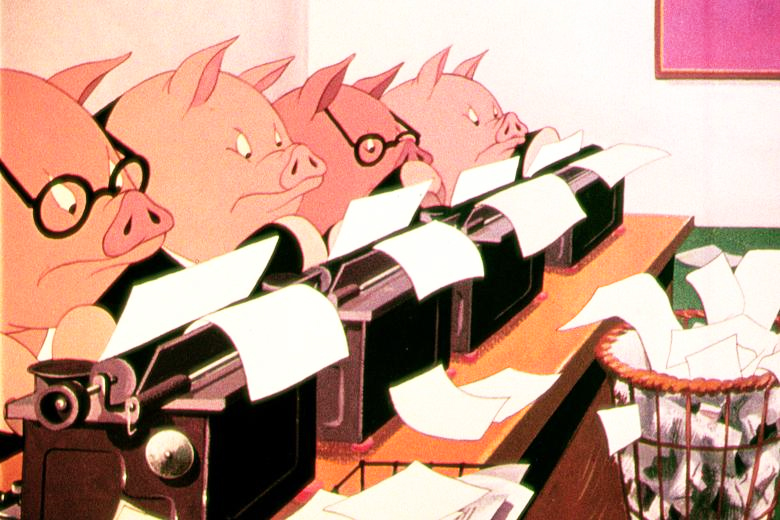

Halas and Batchelor‘s Animal Farm is so lethargic in its movement, it’s difficult to watch. However, whenever a Harold Whitaker scene pops up, it’s something to study. The guy was a fine animator. His work definitely sands out. He came from the Anson Dyer Studio, and had somehow learned to animate in the US methodology.

The Disney studio was having its effect , though as animators such as Borge Ring pretty much taught himself to go well beyond the basics of he European mold. He was close with a number of the Disney animators and studied Disney films religiously. His own personal style is definitely constructed from the US mold.

Even through The Yellow Submarine (1968), you see this flat style of animation. Of course, with the more graphic style of George Dunning‘s feature, the even pacing is better hidden in the mood of the piece.There’s also a lot of music that hides the timing problems.

Even through The Yellow Submarine (1968), you see this flat style of animation. Of course, with the more graphic style of George Dunning‘s feature, the even pacing is better hidden in the mood of the piece.There’s also a lot of music that hides the timing problems.

After Dick Williams, began his effort to alter the look of work coming out his studio, there was a big change in the look of work coming from all over Europe. Sure they slipped into and out of the old school of animation, but now they had learned from Art Babbitt and Ken Harris. (I wish they’d had more of Grim Natwick.) Take a look at the marvelous animation done for Bruno Bozzetto in the Ravel Bolero section of his 1977 feature, Allegro Non Troppo. To some extent, now, the best animation worldwide is coming out of England and France, especially from the younger animators.

So let’s take a look at the differences between the two styles..

- The best of the US style can be seen in those dwarfs in Snow White or the Siamese cat song in Lady & the Tramp or Scar in The Lion King. It’s all in the timing.

- The European style is very obvious in Jiri Trnka‘s 2D animation as in The Four Musicians Of Bremen or Spring-heeled Jack. You can see it in about half of Sylvain Chomet‘s The illusionist (the other half was wonderfully done US style), or, as I’ve already written, Animal Farm – the entire movie.

The US tradition came directly from the wonderful work done mostly after hours at Disney’s studio in the 30′s. They learned how to time animation for weight, for mood, for expression and for balance. Bill Tytla, Marc Davis and Frank Thomas were brilliant at it (though they all did it). The word reached outside the Disney studio and others came into the fold: Ken Harris and Bobe Cannon, Grim Natwick and Rod Scribner, Jack Schnerk and Abe Levitow, Hal Ambro and Tissa David. There are another couple of hundred people I could include if we were naming names. These people all mastered their timing. They knew what they were doing and did it as planned. The animation never does what IT wants to do, but it is controlled by the animator and his (her) timing.

The European style is a very different animal. The timing is flat. It’s usually even paced and moves robotically forward, not always by going in a straight line. The weight is always soft; the emotion is almost nil. The drawings are often beautiful, but there’s no real strength behind that movement.

The European style is a very different animal. The timing is flat. It’s usually even paced and moves robotically forward, not always by going in a straight line. The weight is always soft; the emotion is almost nil. The drawings are often beautiful, but there’s no real strength behind that movement.

Things have changed quite a bit since the advent of Richard Williams and his work, but even there I see it at times. In Dick’s work, I mean, I sometimes see it. (Not surprising since I infrequently see it in Art Babbitt‘s animation. – and lest you think I’m biased, I often see it in my own work and have to rework it. (I’m not trying to hurt anyone here, I’m just reporting what I sense and see and feel.) Just talkin’ animation here. It’s basic and can so easily be bypassed. Animation is ALL ABOUT the timing. Norm Ferguson couldn’t draw very well at all, but he was one of the GREAT animators of all time. There was no even-paced timing in his makeup; the same has to be said of Tytla or Grim Natwick. Babbitt did do it. He was one of our great animators, but he infrequently paced his work in a very dull way. I could give you examples, but I won’t look for yourself, because when he’s good, he’s brilliant. Take the scene he did in The Thief and the Cobbler where the evil Vizier, Zig Zag, shuffles the playing cards.

A great example of what I’m talking about has all to do with Tom & Jerry. Take a look at some of those produced by Gene Deitch out of Czecheslovakia in the early 60s. Don’t compare this with the fully-animated shorts produced by Hanna & Barbera at MGM. No, compare it to the films done by Jack Kinney using a pickup studio. Most of the staff was free lance California employees. Turks without a space to work in the studio. Those Kinney films, badly animated though they are, are pure US-styled animation. The Deitch films are equally, poorly animated, but these also are animated with a European staff that animated the way a European would. The timing is rigidly even in its pacing.

You often get that European feel in the cgi work done today.

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve seen scenes where things suddenly go slack and move, seemingly, of their own accord in cg films. Perhaps the two arms will complete a motion that was started by an animator, and (s)he will allow the rest of the motion continue on its own to a final rest stop. It’s not animation anymore, it’s just a completion. I do quite dislike this when and if I see it. (Thought, admittedly, too often I’m not paying attention enough.) There’s a scene somewhere in Paperman where the male, standing in profile, has his two arms moving forward to a rest. They move at exactly the same speed, doing exactly the same thing, and it bothers me. Tissa certainly would have scolded me for allowing such a move to happen. I have to hope and believe that that’s what the animator wanted.

I had actually intended to keep going. One can’t really just say US and European animation styles. After all, there’s also the work out of Asia. The Japanese market, of course, is very different than the rest, and, thanks to what Miyazaki has been doing and his success in doing it, things are changing radically. Where he once blended in with the Anime animation that was all present, things are now changing to more of an emotional, Western appeal. My Neighbor Totoro started something, that changed wildly when he did Spirited Away and Ponyo. When I saw The Secret World of Arrietty, I knew things had changed completely. There was real character animation on the screen. One character was different from the next, and a lot of it had to do with the movement.

I had actually intended to keep going. One can’t really just say US and European animation styles. After all, there’s also the work out of Asia. The Japanese market, of course, is very different than the rest, and, thanks to what Miyazaki has been doing and his success in doing it, things are changing radically. Where he once blended in with the Anime animation that was all present, things are now changing to more of an emotional, Western appeal. My Neighbor Totoro started something, that changed wildly when he did Spirited Away and Ponyo. When I saw The Secret World of Arrietty, I knew things had changed completely. There was real character animation on the screen. One character was different from the next, and a lot of it had to do with the movement.

I was also fascinated with the work of Satoshi Kon, before his untimely death. His work was growing enormously with each and every film. The movies he made were adult in every sense of the word, and they were beautifully constructed, drawn and animated. I still go back to watch copies of his films. ________“Arrietty”

I was going to write about Katsuhiro Ôtomo, but I realize I’ve taken a sidestep. These are directors, and this article is about animators. In short, there is an Eastern style, and I’m glad to see that because of a couple of directors, they’re doing thier own take on the US version of animation character developement. It’s good to see it happening.

Essentially, the world is becoming smaller. Global animation styles are settling in, and I hope there will be a 2D animation so that the job can be complete in a few more years.

Animation &Commentary &Daily post &Errol Le Cain &Richard Williams 25 Feb 2013 05:28 am

POV

Next Friday, at the invitation of filmmaker-editor-director, Kevin Schreck, I’ll have the pleasure of seeing his recently completed documentary, Persistence of Vision. This is the story of the making of Richard Williams‘ many-years-in-the -making animated feature, The Cobbler and the Thief. I’m not sure of the film maker’s POV, but I somehow expect it to be wholly supportive of the insistent vision of Richard Williams in the making of this Escher-like version of an animated feature. A work of obsession.

It’s the tale of an “artist”, someone who sees himself as an artist, and continually pushes through the world with what would seem to be evident proof of such. After all, this man had single-handedly altered the face of 2D animation in a world that was about to throw it away with all its rich history and artistry and strengths. A medium that had developed through the years of Disney with giant, filmed classics such as Snow White, Pinocchio, Fantasia and even Sleeping Beauty. A medium that had drastically changed to 20th century graphics under the hands of people like John Hubley, Chuck Jones, George Dunning and many others and had just about reached a zenith where it was moving toward something wholly new, something adult.

Instead the medium took a turn in the wrong direction. The economics of television brought us back almost 100 years as films became more and more simplistic and simpleminded in the rush to be cheap. Even the Disney studio went for the poorest subject matter using cost-saving devices to sell their films. Films became shoddier and shoddier, and the economics ruled. The closest the medium would come to art was Ralph Bakshi‘s Fritz the Cat and Heavy Traffic, low budget movies that traded on racy material in exchange for an attempt at something adult, stories barely held together with editing tape. Animation was getting a bad name from every corner whether it was the sped-up graphics of Hanna-Barbera, the reach to the lowest common denominator with poor animation from Disney, or the shock and tell of Ralph Bakshi‘s filmed attempts at what he saw as art.

Williams took a different turn. He went back to the height of animation’s golden era, inviting artists such as Grim Natwick, John Hubley, Ken Harris and Art Babbitt to his London studio to lecture on the rules and backbone of the animation. He brought some of these people to work on a feature that he’d decided to create within his studio on the profits of commercials. These very same commercials financed the training of Dick and his young staff.

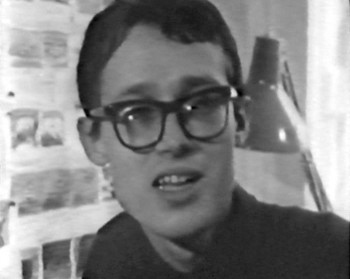

A documentary done in 1966, called The Creative Person: Richard Williams offers an excellent view of his studio. We see snippets of shorts Dick made with his own coin: Love Me Love Me Love Me (1962) or The Sailor and the Devil (1967) wherein we see the training of a young and brilliant illustrator named Errol le Cain. (Le Cain became known for his magnificent, glimmering children’s book illustrations. He was doing most of the backgrounds for The Cobbler and the Thief, and had certainly had a large part in its design.)

A documentary done in 1966, called The Creative Person: Richard Williams offers an excellent view of his studio. We see snippets of shorts Dick made with his own coin: Love Me Love Me Love Me (1962) or The Sailor and the Devil (1967) wherein we see the training of a young and brilliant illustrator named Errol le Cain. (Le Cain became known for his magnificent, glimmering children’s book illustrations. He was doing most of the backgrounds for The Cobbler and the Thief, and had certainly had a large part in its design.)

We see in this documentary the first hint of The Cobbler when it was called Nasruddin. It was based on a book of middle eastern tales of a wise fool whose every short story tells a new and positive anecdote. Dick had illustrated several books of these tales with many funny line drawings. The book was written by the Idres Shah who had undertaken a role within the Willams studio finding funds for the feature. Eventually, the two had a falling out, and Idres Shah left with his property. Williams took the work he had done as Nasruddin and reworked it into The Cobbler and the Thief. ________________________________Errol le Cain

We see in this documentary the first hint of The Cobbler when it was called Nasruddin. It was based on a book of middle eastern tales of a wise fool whose every short story tells a new and positive anecdote. Dick had illustrated several books of these tales with many funny line drawings. The book was written by the Idres Shah who had undertaken a role within the Willams studio finding funds for the feature. Eventually, the two had a falling out, and Idres Shah left with his property. Williams took the work he had done as Nasruddin and reworked it into The Cobbler and the Thief. ________________________________Errol le Cain

Meanwhile the work within his studio continued to develop, growing more and more mature. The commercials became the highlight of the world’s animation. Doing many feature film titles such as What’s New Pussycat (1965), A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1966), The Charge of the Light Brigade (1968) led to Dick’s directing a half-hour adaptation of The Christmas Carol (1971). Chuck Jones produced the ABC program, and it led to an Oscar as Best Animated Short.

Through all this The Cobbler and the Thief continued. Many screenplays changed the story and the stunning graphics that were being produced for that film were often shifted about to accommodate the new story.

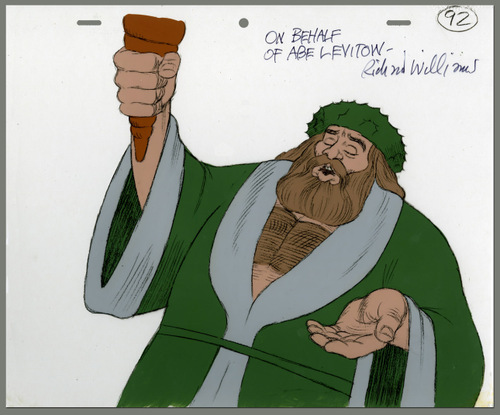

By this time, Williams had developed something of a name within the world of animation. Strong and important animation figures went to his studio to work for periods of time. Someone like Abe Levitow taught and animated for the studio. (His scenes for The Christmas Carol are among the most powerful.) Many of the Brits that worked in the studio and then left to start their own companies were now among the world’s best animators.

By this time, Williams had developed something of a name within the world of animation. Strong and important animation figures went to his studio to work for periods of time. Someone like Abe Levitow taught and animated for the studio. (His scenes for The Christmas Carol are among the most powerful.) Many of the Brits that worked in the studio and then left to start their own companies were now among the world’s best animators.

Williams had the opportunity of doing a theatrical feature adaptation of the children’s books The Adventures of Raggedy Ann and Andy and took it. A large staff of classically trained animation leaders such as Art Babbitt, Grim Natwick, Tissa David, Hal Ambro, Emery Hawkins and many others worked out of New York or LA as the company set up two studios to produce this film. Working for over two years, Dick’s attention was diverted to work away from his London studio, where commercials and some small devotion was given to The Thief by a few of the key personnel working there. Dick spent a good amount of his time in the air flying from NY to LA to NY to London and back again and again. He concentrated his animation efforts on cleaning up animation by some of the masters, rather than allow proper assistants to do these tasks. By doing this he was able to reanimate some of the work he didn’t wholly approve of. Entire song numbers were reworked by Dick as the film flew well behind its budget and schedule.

Eventually, the film finished in confusion and mismanagement, and Dick moved to his LA studio where he continued commercials and began Ziggy’s Gift, a Christmas Special for ABC.

From this he went back to his London studio and did the animation for Who Framed Roger Rabbit for producer/director Robert Zemeckis. He hoped that work on this feature, which won three Academy Awards, including a special one for the animation, would be the triumph he needed to help him raise the funds for The Thief and the Cobbler. Now that he was safely back in his own studio in Soho Square he felt more focused.

From this he went back to his London studio and did the animation for Who Framed Roger Rabbit for producer/director Robert Zemeckis. He hoped that work on this feature, which won three Academy Awards, including a special one for the animation, would be the triumph he needed to help him raise the funds for The Thief and the Cobbler. Now that he was safely back in his own studio in Soho Square he felt more focused.

A contract came from Warner Bros., and the work began in earnest.

Dick’s history wasn’t the best working on these long form films. Chuck Jones replaced him on The Christmas Carol to get it finished when work went overbudget and schedule. Dick was putting too much into it. Gerry Potterton finished Raggedy Ann when the budget went millions over with less than a third completed. Eric Goldberg took over Ziggy’s Gift, the Christmas Special for ABC, to get it done on time. On Roger Rabbit, the live action director stayed intimately involved in the animation after his shoot was complete. When it became obvious that things weren’t going well, he stepped in to complete that film.

In all cases of all of these films, Dick never left. He stayed on working separately on animation or assisting to try to keep a positive hand in the quality of the work that was done.

When The Cobbler and the Thief ran into very serious trouble, there was no secondary Director or Producer to come in and complete the work. Instead that job fell to the money men. The completion bond company, essentially an insurance company for Warner Bros. to make sure they wouldn’t lose their money if things didn’t go well, stepped in. They closed Dick’s studio and removed Dick from the premises. The boxed up and carted off all animation work done or in progress. It was all moved back to Los Angeles.

When The Cobbler and the Thief ran into very serious trouble, there was no secondary Director or Producer to come in and complete the work. Instead that job fell to the money men. The completion bond company, essentially an insurance company for Warner Bros. to make sure they wouldn’t lose their money if things didn’t go well, stepped in. They closed Dick’s studio and removed Dick from the premises. The boxed up and carted off all animation work done or in progress. It was all moved back to Los Angeles.

The Weinsteins, through their company, Miramax bought the film at auction and completed it with a poor excuse of an animation outfit they set up in LA. Work was also sent to Taiwan. The script was reworked trying to capitalize on the success of Disney’s Aladdin that had recently opened in the US. If Robin Williams‘ ad libbing could be such a success, imagine how well Jonathan Winters could do repeating that for a character who, in Dick’s original version, had no voice. Now he didn’t stop talking.

The new film failed miserably and deserved to do so. The primary audience, I would suspect, was the entire world animation community coming to look down on the artificially breathing corpse.

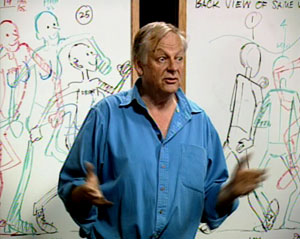

Richard Williams, himself, retired and moved far from the mainstream. He continues to work on small animation bits, but his primary work has been in making a series of DVD lectures revealing how animation should be done. This accompanies a well-received book he wrote and illustrated. Meanwhile, the animation community still hopes that something will emerge from that corner.

Richard Williams, himself, retired and moved far from the mainstream. He continues to work on small animation bits, but his primary work has been in making a series of DVD lectures revealing how animation should be done. This accompanies a well-received book he wrote and illustrated. Meanwhile, the animation community still hopes that something will emerge from that corner.

Dick turns 80 years old on March 19th. He’s still an amazing forceful and exciting personality. I wish I had more access to him (as does most of those who knew him back then.) He’s had probably the greatest effect on the animation industry of anyone since the late sixties. There are still studios thriving today on information they learned from Dick and his teaching.

If you’re unfamiliar with the blog, The Thief, I suggest you take a look.

Animation Artifacts &Richard Williams 22 Feb 2011 08:18 am

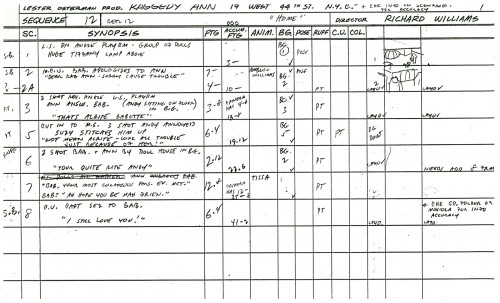

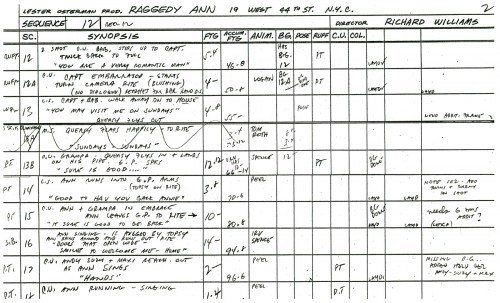

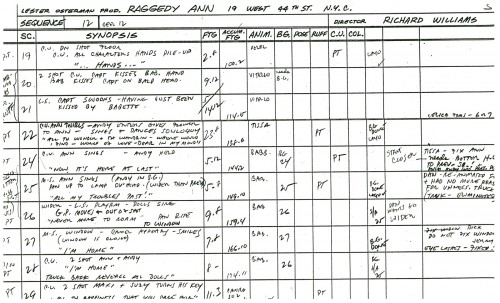

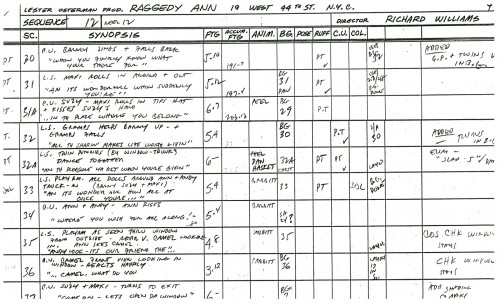

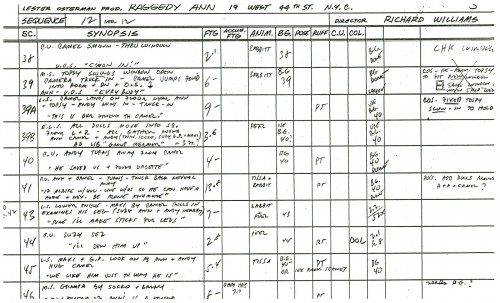

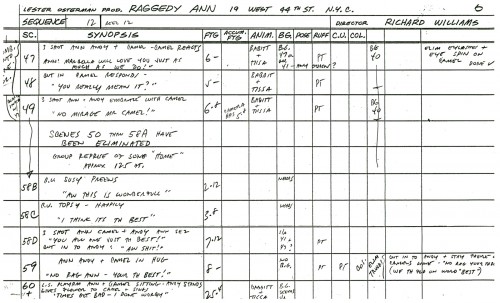

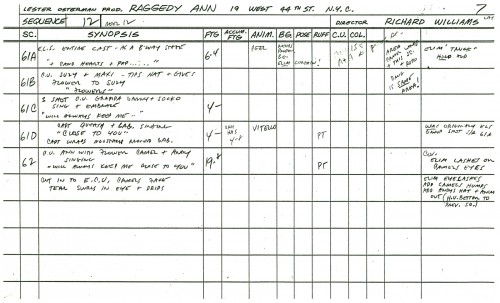

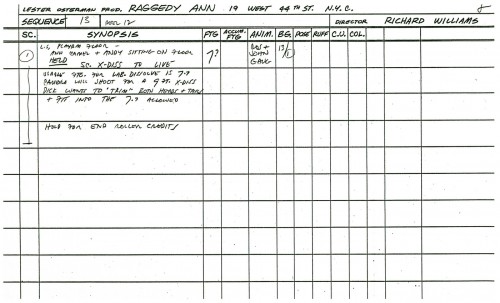

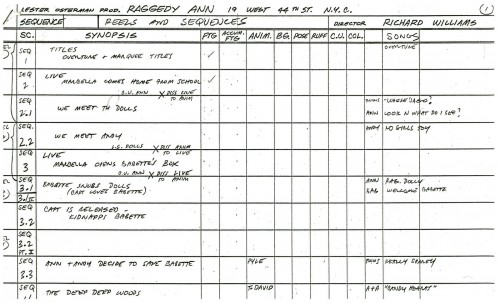

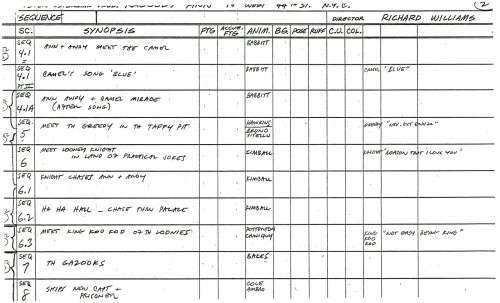

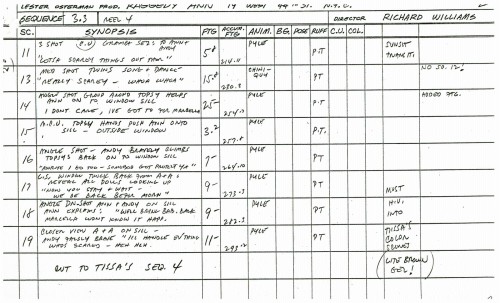

Raggedy Drafts – 7/ seq. 12

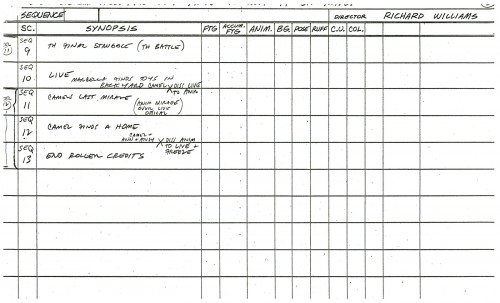

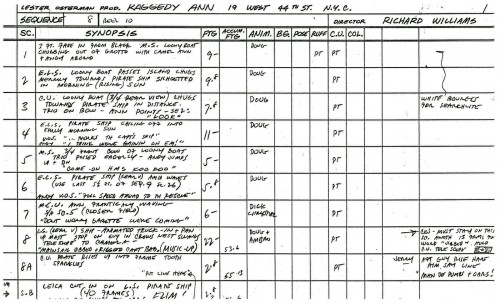

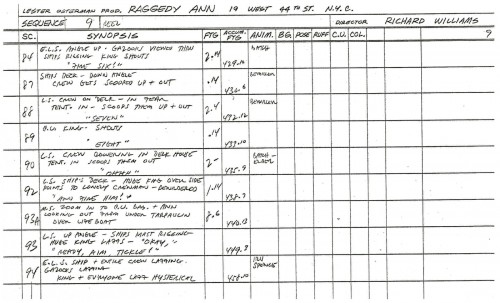

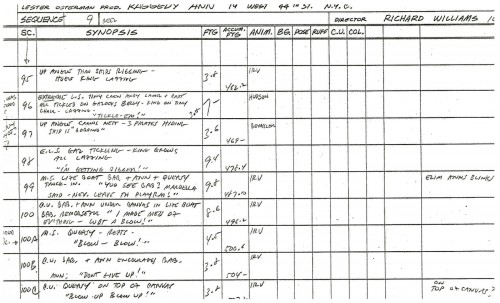

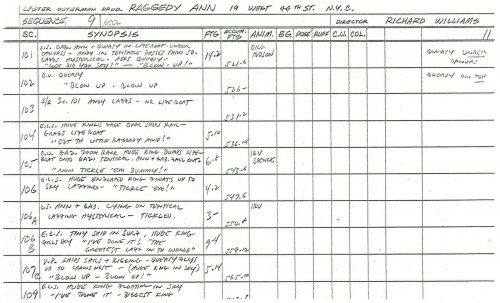

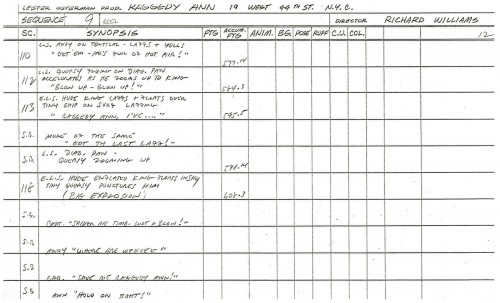

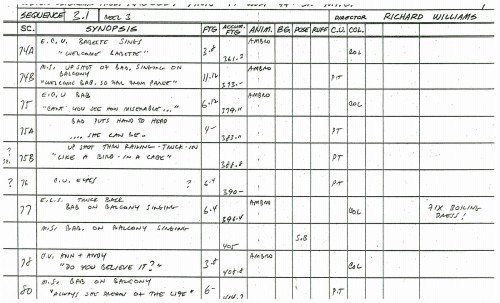

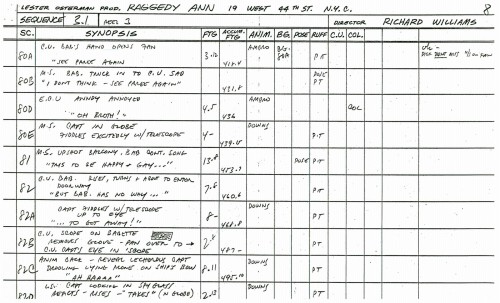

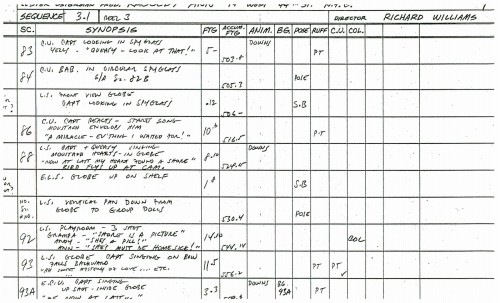

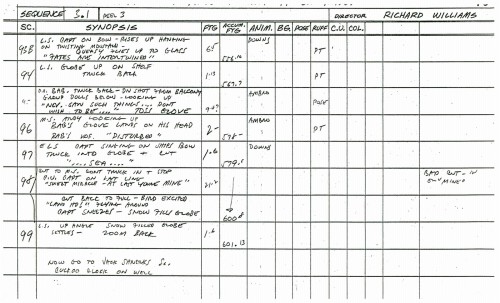

- Here we go with the final installment of the Raggedy Ann & Andy: A Musical Adventure drafts. This, of course, was the feature Richard Williams directed (3/4 of the way) in 1977. You’ll note that as we’ve gone on, the drafts have gotten sloppier and sloppier. This last batch (separated from the last installment by 2 sequences of live-action film) included a couple of faux sheets. They were started and redone. I only include the redone sheets.

The animators working on this ending sequence include: Hal Ambro, Dick Williams, Tissa David, Jim Logan, Tom Roth, Spencer Peel, Irv Spence,Art Vitelo, Art Babbitt, Dan Haskett, Cosmo Anzilotti and John Gaug.

The final three sheets are a sequence breakdown – a reduction of the drafts, in case you’ve lost your place and want to find out what sequence to look for.

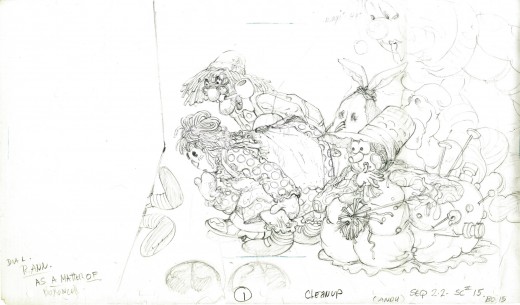

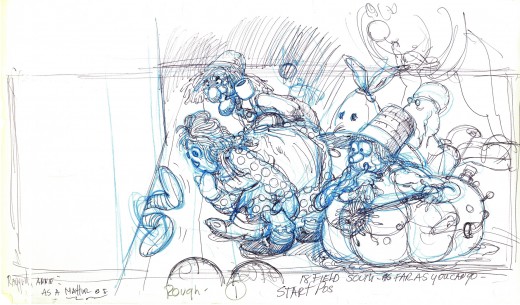

A Corny Cole rough (above) done with BIC pen and

a Corny Cole clean up (below) done in pencil.

Sequence 12

1

1

Corny Cole storyboard drawings.

Sequence Breakdown

Animation &Animation Artifacts &Richard Williams &Tissa David 16 Feb 2011 08:15 am

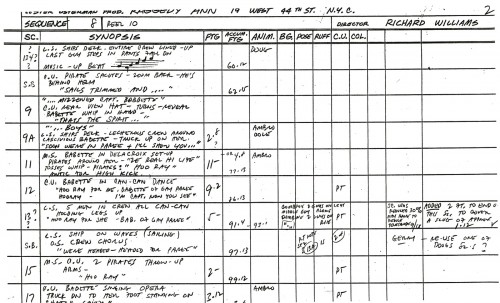

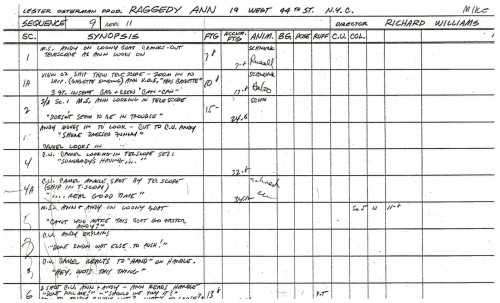

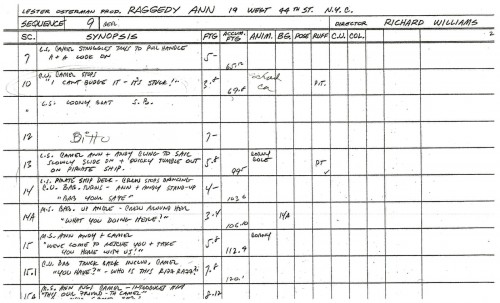

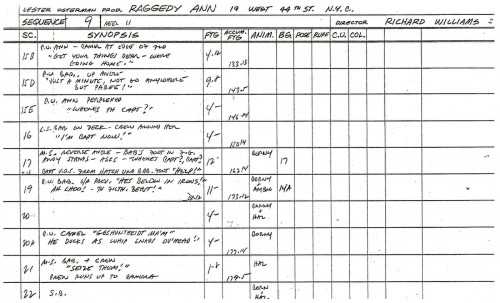

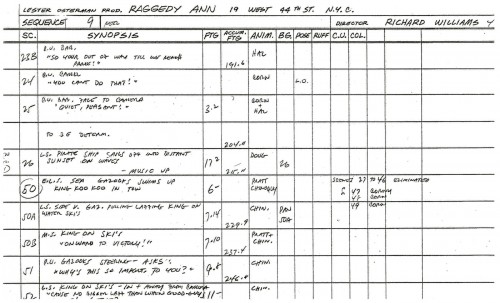

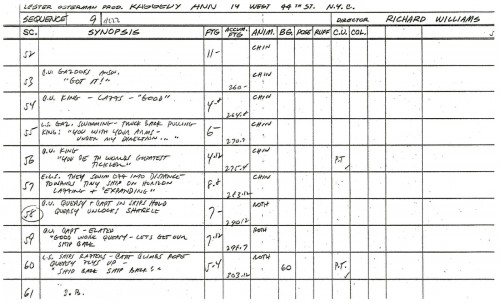

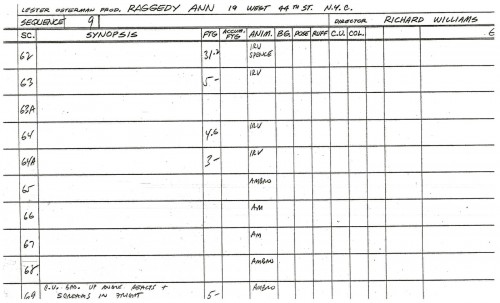

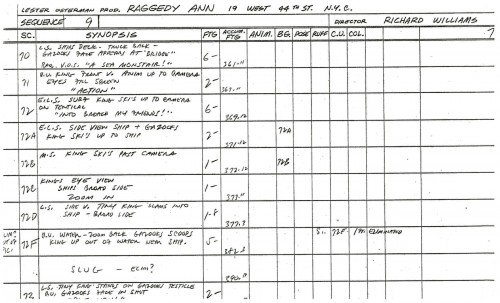

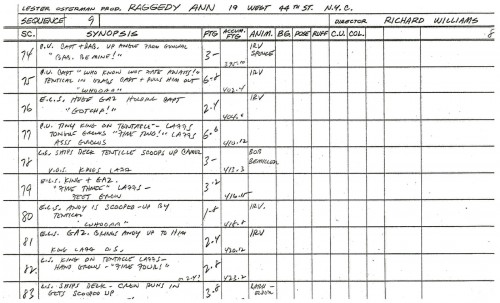

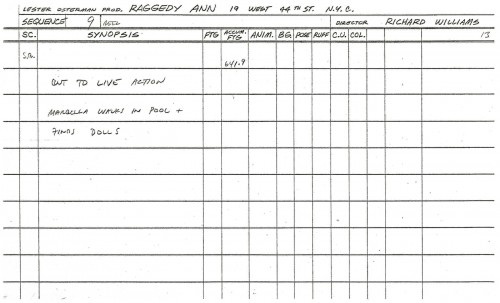

Raggedy Drafts – 6 / seq. 7, 8 & 9

- Continuing on with the Raggedy Ann & Andy: A Musical Adventure drafts, we move onto seqeunces 7, 8 and 9. This involves the Loony King, the Loony Knight and Babette at sea.

Animators for these sequences include: George Bakes, Gerry Chiniquy, Doug Crane, Dick Williams, Chrystal (Russell) Kablunde, Hal Ambro, Charlie Downs, Art Vitello, Jack Schnerk, Corny Cole, Tom Roth, Irv Spence, Bob Bemiller, and Warren Batchelder.

A lot of talent in one place; too bad the film doesn’t hint at it.

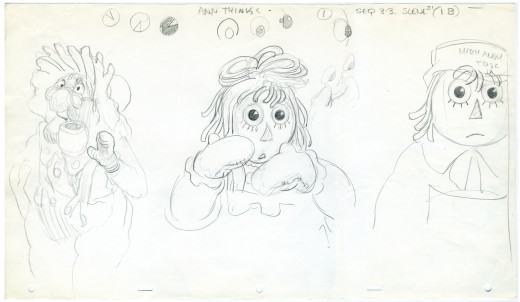

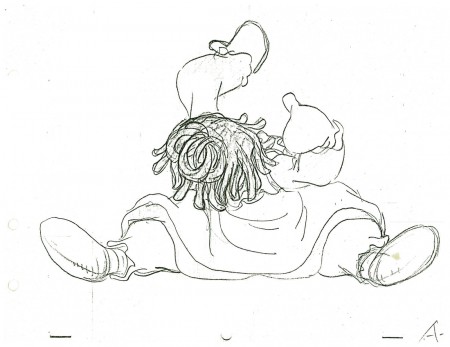

To dress up the post I’ve added five of Tissa’s key drawings from an early scene.

Sequence 7

Sequence 8

8-5

8-5

For some reason this bad drawing of the “Greedy” was attached

to the drafts. So I just iuncluded it here, as well.

Sequence 9

Animation Artifacts &Richard Williams 17 Jan 2011 09:20 am

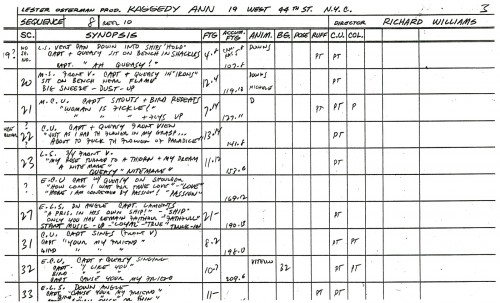

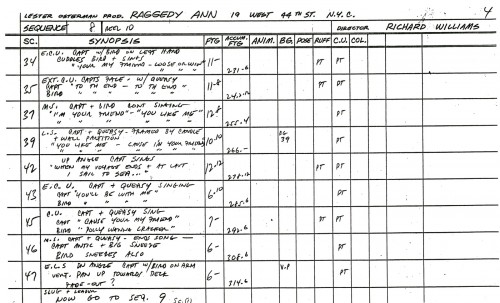

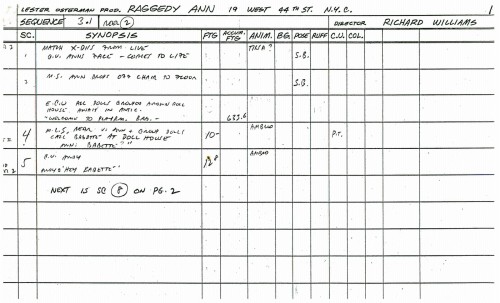

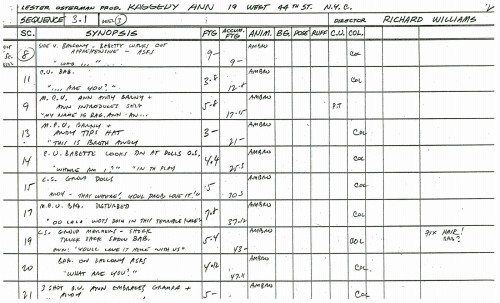

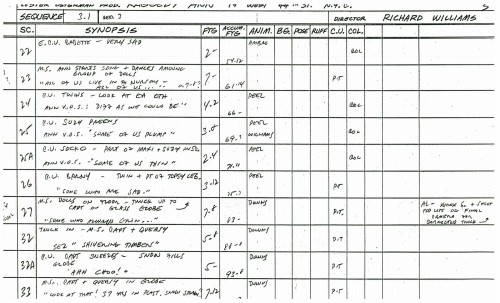

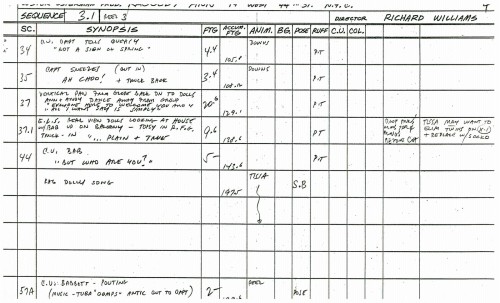

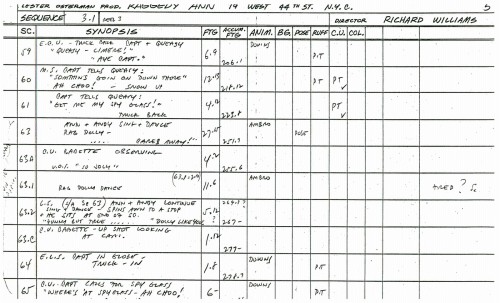

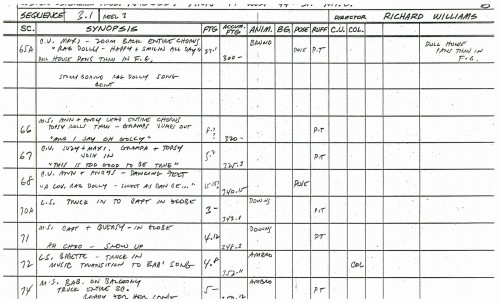

Raggedy Drafts – 2 / seq. 3

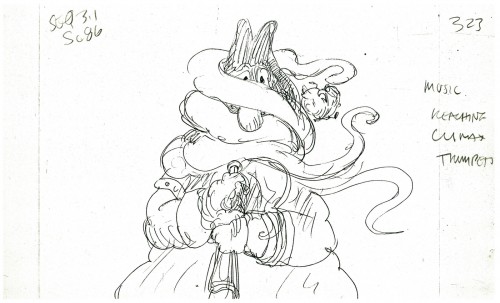

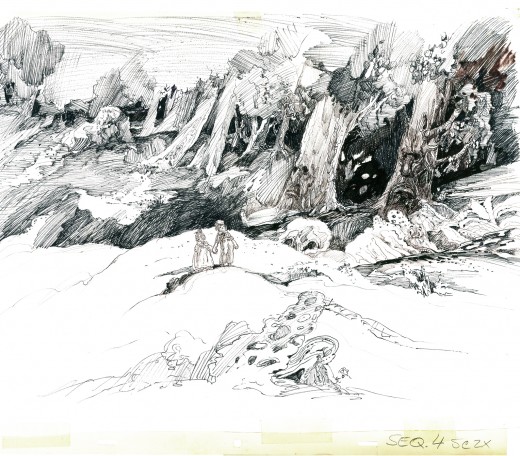

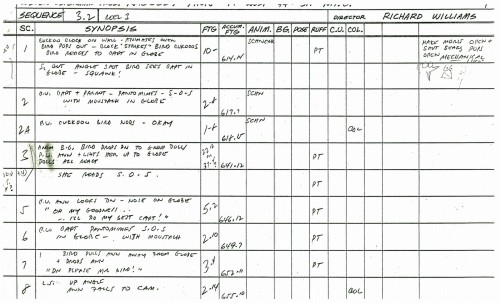

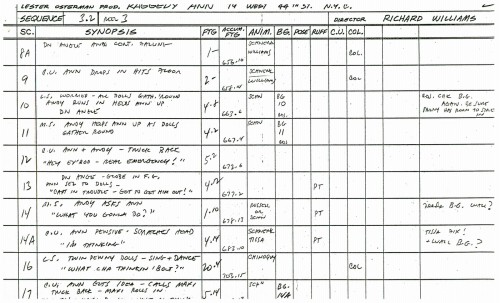

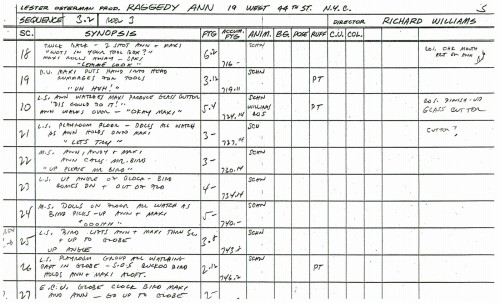

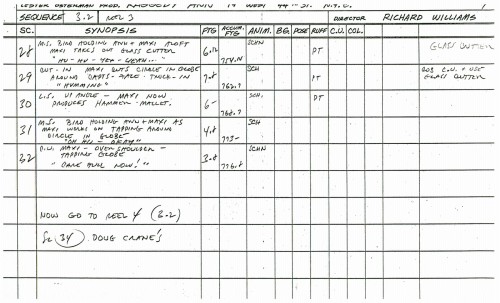

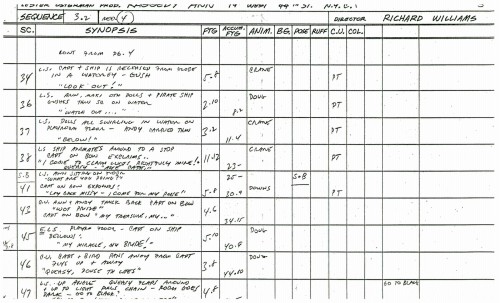

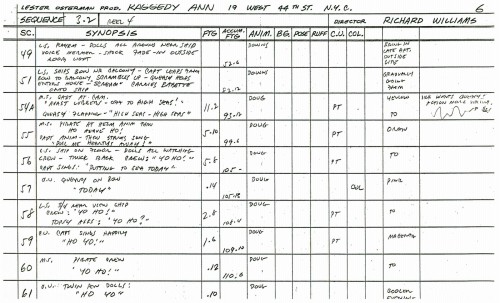

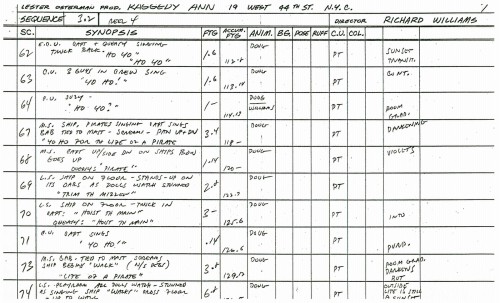

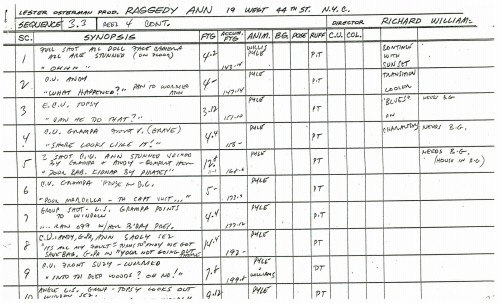

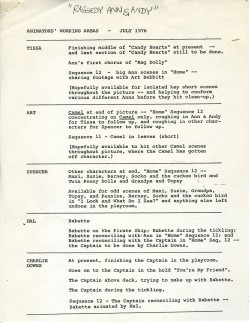

- Continuing with the drafts I have from Raggedy Ann & Andy, I give you sequence 3.1, 3.2 & 3.3.

The animators employed are: Hal Ambro, Sencer Peel, Dick Williams, Charlie Downs, Tissa David, John Bruno, Jack Schnerk, Chrystal (Russell) Klabunde, Gerry Chiniquy, Doug Crane, and Willis Pyle.

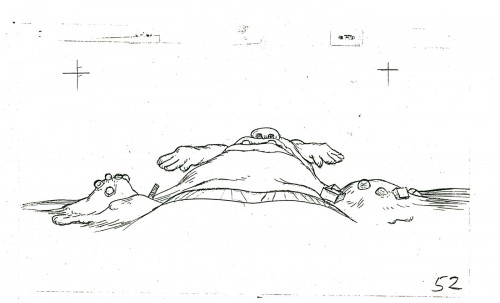

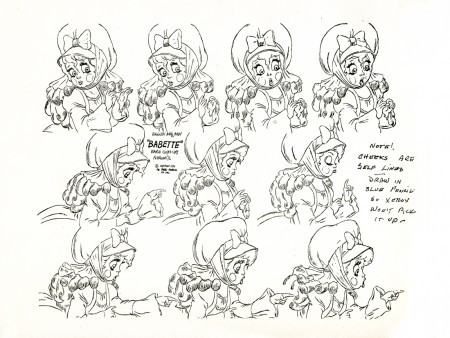

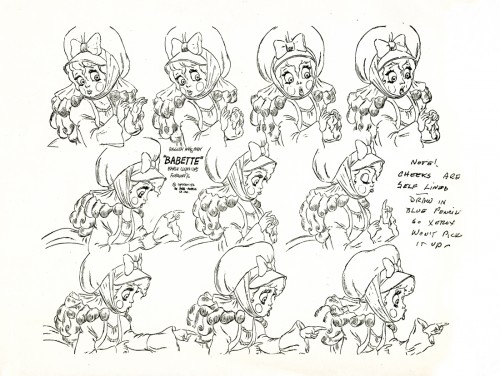

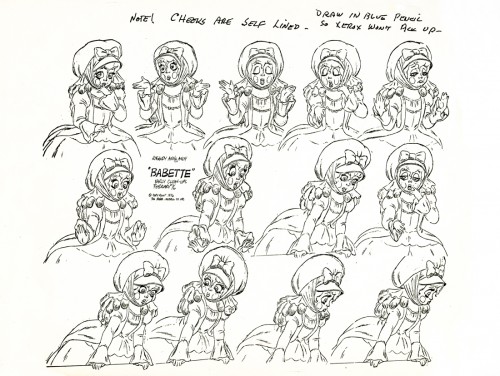

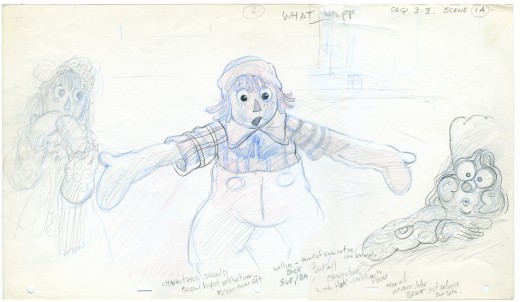

Dick Williams did most of the cleanup of this sequence himself. He was particularly interested in the character of “Babette” which Hal Ambro animated. Dick reworked every one of those scenes while doing CU & Inbts. I’ve posted a model sheet of Babette from one of the scenes in this sequence.

For those of you who’d rather see artwork than charts, I give you another of Corny Cole’s oversized stunning bits of preliminary artwork for Tissa David‘s sequence, the deep dark woods.

“Babette”

Articles on Animation 13 Feb 2009 08:50 am

Heidi’s Song

- Animated features, like some of the shorts, come and go. While working on it, there’s often an expectation that THIS will be the film to catch gold and change history. It doesn’t happen often.

Looking back on a puff piece from some past feature is oftentimes ludicrous; sometimes it’s just sad. Here’s a 1981 story from Millimeter Magazine about Hanna Barbera’s upcoming feature, Heidi’s Song. It sounds like it may be the future, but really it’s even hard to remember the film. It certainly didn’t change the world.

Will HEIDI’S SONG be its SNOW WHITE?

by John Canemaker

Hanna-Barbera Productions Inc. is such a giant corporate entertainment entity that it prompts the old joke: What does a two-ton canary sing? Any damn thing it wants! This Hollywood “canary” tias expanded since 1957 to become the wold’s largest producer of animated TV series andspecials; more recently Hanna-Barbera has become involved in themed amusement parks and live action movies for television.

Now H-B is eager to enter and conquer the sacred Disney domain of fully animated, “quality” feature-length animated films for theatrical release. William Hanna and Joseph R. Barbera hope to do so with an expensive flourish this summer when they will premiere HEIDI’S SONG, a $9 million cartoon feature that has been in production for five years. The film’s staff of 200-plus includes 12 background painters, 60 assistant animators, eight layout people, and 18 top character animators. All cut their teeth years ago at the Disney studio, or at MGM, working with Hanna and Barbera during their halcyon days in the 1940s and ’50s producing Tom and jerry shorts and animated segments for live action features such as Jerry the Mouse dancing with Gene Kelly in ANCHORS AWEIGH.

A moment of menace for Heidi whose voice is dubbed in by

Broadway actress Margery Gray in the Hanna-Barbera feature.

Joseph Barbera claims HEIDI’S SONG will be “a step forward in animation that’s very exciting.” But perhaps it will actually be a welcome artistic step back—a comeback of sorts—for Hanna and Barbera, who were once considered by their peers and the public to be superior cartoon craftsmen, winners of seven Academy Awards for two decades of beautifully timed and fully animated Tom and Jerry cartoons. In the 23 years since forming their own company—a factory geared to the production of “limited” animation series, a reduced form of animation that, as an H-B publicity release points out, “ignored the time-consuming and expensive detail that would not be visible on the dimly lit video screen”—Hanna and Barbera have produced over 20 TV specials and some 60 series (“Huckleberry Hound,” “Yogi Bear,” “The Flintstones,” “The Jetsons,” “Scooby & Scrappy Doo,” and so on).

In other terms, H-B produces more film footage in a week today than it did in a year at MGM. The principals’ choice to, as they say, “exploit a niche Disney had missed in family entertainment, with low cost cartoons for television,” has made the two men cartoon tycoons, rich beyond their dreams. They claim “there is not one hour out of every 24 that a Hanna-Barbera cartoon is not entertaining some segment of the world’s population.”

When, in 1967, Taft Broadcasting Company of Cincinnati acquired H-B, the company expanded its operations into five themed amusement parks, including Kings Island (Cincinnati) and Marineland (Los Angeles), where life-sized replicas of H-B characters—Yogi, Huckleberry et al — roam about greeting visitors. More than 1500 licensed manufacturers world-wide turn out 4500 different products bearing likenesses to H-B characters, for example, Flintstone window shades, Scooby-Doo pajamas.

In 1978, H-B won an Emmy, this time for a live action TV movie, “The Gathering,” starring Ed Asner and Maureen Stapleton; more live action films are planned for theatrical release and TV. With all this success, why would Hanna-Barbera bother pouring money into turf that is traditionally Disney’s and has proved to be a producer’s graveyard, from GULLIVER’S TRAVELS (1939) to RAGGEDY ANN & ANDY (1977)?

Company is built on cartoons

One should not forget that cartoons are the heart of the H-B corporate structure (as they are at the Disney studio). And it must be noted that as popular as the TV series are with small children, there is, to Hanna and Barbera’s distress, a persistently vocal, mostly adult contingent that just plain doesn’t like their cartoons! Veteran animator/director Chuck Jones, for instance, dismisses the whole breed of limited animation TV fare as “illustrated radio!” Writer Leonard Maltin once denounced H-B cartoons as “consciously bad: assembly-line shorts grudgingly executed by cartoon veterans who hate what they’re doing.”

Years of this kind of criticism (and worse from TV critics, parents groups and, most painfully, professional peers) has hit Hanna and Barbera right in their pride of craftsmanship. Witness Bill Hanna’s responses during an interview with Eugene Slafer: “Are you accomplishing what you believe is good TV animation?” asked Slafer. “No, I do not,” came

Years of this kind of criticism (and worse from TV critics, parents groups and, most painfully, professional peers) has hit Hanna and Barbera right in their pride of craftsmanship. Witness Bill Hanna’s responses during an interview with Eugene Slafer: “Are you accomplishing what you believe is good TV animation?” asked Slafer. “No, I do not,” came

__Director Robert Taylor states that HEIDI’S SONG has _______Hanna’s candid reply.

__“a style unto itself, more like a live action picture in_______ To a further probe, “Have

__the staging, as opposed to what you’d see in animation.”____you ever been ashamed of your work, especially since parents have ranted about the general lack of quality on Saturday morning cartoon shows?” Hanna admitted, “Actually I feel like I should crawl under a seat sometimes.”

Joe Barbera recently spoke with Millimeter about his partner’s abilities to recognize the difference between good and bad quality animation and their alleged lack of craftsmanship. “We had to get that stuff out for Saturday morning,” he explains. “That’s a budget problem. Believe me, I don’t stand still for people saying, ‘Oh, they’re doing junk! They don’t know how to do…. ‘We’re not doing that. We only do it because you don’t get the money to do it differently. When we get the money —and you’re talking about millions—we doajob!”

So perhaps the initial thrust for the HEIDI feature came from Hanna’s and Barbera’s desire to prove they haven’t forgotten how to produce animation in the “classical” style, or how to create memorable characters that affect more than an audience’s funny-bone. Of course, Hanna and Barbera are too business-wise to produce a full-animation feature merely to assuage pain dealt their pride; there also had to be a bedrock of financial motivation behind the move and, sure enough, there was. “The thrust,” states Barbera, “was to do one every year and to build a superb perennial library, which Disney had for years.”

The Disney animated features, from SNOW WHITE (1937) to THE RESCUERS (1977), are re-released like clock-work every seven years, just in time to greet a new generation or to remind an older group of their existence. “They are,” says Barbera admiringly, “forever pictures;” that is, films that keep the Disney empire well-oiled with money derived from box office returns (pure profit, since there are no production costs on re-releases), and from lucrative merchandising spin-offs, like comic strips and dolls for themed amusement park rides. This money-making machine depends upon the public’s continuing affection for the cartoon characters and their “classic” stories found in the Disney features. Hanna and Barbera have not yet fully entered this profit arena, but they have been working on it.

Previous animated features

HEIDI’S SONG is not H-B’s first attempt to produce an animated feature. There was, for example, HEY THERE, IT’S YOGI BEAR in 1964 and A MAN CALLED FL1NTSTONE in 1966, both low-cost, limited animation, based on the one-dimensional characters from TV. Neither film was a “forever” picture.

There was,”in 1973, an H-B version of E.B. White’s book Charlotte’s Web, but this, too, suffered from the taint of limited animation and questionable production values. Reviewer Vincent Canby of The New York Times said of the film, “Parents will survive it, and so will the children.” Barbera acknowledges there was “a problem” with CHARLOTTE’S WEB, but to him it was a misjudgment of the financial potential of the material. “Charlotte’s Web,” says Barbera, “is an American classic. It is not an all-world classic. Germany ended up calling it Zuckerman’s Pig, after the name of the man who owned the pig in the story, because who ever heard of a Charlotte’s Web? The film version is recouping some of its money on Home Box-Office TV, on video cassettes and in non-theatrical markets, a fate H-B hopes to avoid for HEIDI’S SONG.

While Disney can produce almost any project known or unknown because of the sales value inherent in the name, “Disney,” Hanna-Barbera is not yet in that sublime position. To the general public, “Disney” means full-animation, perfect technological craftsmanship, beloved characters in stories containing mythic or nostalgic associations. To the same public, “Hanna-Barbera” means limited animation of flat characters on redundant television series. H-B seeks to improve its image with HEIDI’S SONG.

Animator Charlie Downs (left) flips drawings for director Bob Taylor.

HEIDI’S SONG is the story of an orphan girl, based on Johanna Spyri’s 100-year-old, internationally known book. The cartoon feature contains a”Broadway” score of 16 songs by veterans Sammy Cahn (lyrics) and Burton Lane (music). The characters’ voices include Lome Greene as Heidi’s reclusive grandfather, Broadway actress Margery Gray as Heidi, and Sammy Davis, Jr. as King Rat, leader of a band of rodents. Other characters include a “mean and scary ancient housekeeper,” Fraulein Rottenmeier; Sebastian, “the butler who helps Rottenmeier be miserable to Heidi”; Clara, a lonely girl “confined to a wheelchair”; Peter, “a young goatherd, agile as the animals he tends.”

Off-setting the human characters is a gaggle of animals; Spritz, Heidi’s “feisty” pet goat; Hooter, a baby owl who “warns Grandfather of Heidi’s imprisonment in the cellar”; Gruffle, Grandfather’s “gruff old hound”; Schnoodle, a “nasty little dachshund who is rotten like his mistress, Fraulein Rottenmeier.” There is also a “crusty” German Schnauzer, a white mare, a white kitten and the aforementioned royal rat, “the power-loving and peppy leader of the rats in Sebastian’s basement, who spurs his clownish rodents into a strong force to attack Heidi.”

“We do have our animals,” points out Barbera. “My gosh, if we don’t have animals, we’re in big trouble,” he notes with an eye toward audience appeal and merchandising. “But we do have humans and some marvelous dancing,” he continues. “We are not rotoscoping,” he says, referring to the technique of animators tracing frame-by-frame projections of live-action. “I don’t care for rotoscoping at all.”

Choosing talent

Hanna and Barbera have instead hired a team of 20 top character animators—”Let’s use the word humbly and respectfully: the old-timers, “adds Barbera—people like Hal Ambro and Charlie Downs, both of whom specialize in human figure animation and have worked on films such as Disney’s PETER PAN and Richard Williams’ RAGGEDY ANN & ANDY. There are also master animators of animal caricatures and comic timing, such as Irv Spence and Ed Barge, veterans of the fine Tom and ]erry shorts. Th’e great Disney/MGM animator, Preston Blair, was also involved with HEIDI for a time.

One might assume that the difficult task of manipulating the drawn human form in full animation is what kept the film in production for five long years. Barbera, however, offers this explanation: “When we are in the slow season, which happens in television all the time, everybody has to be laid off. We were going to keep people busy on the feature. We found that doesn’t work. The kind of people you use on a feature are the old super-pros of our industry, and there are few of them left.

One might assume that the difficult task of manipulating the drawn human form in full animation is what kept the film in production for five long years. Barbera, however, offers this explanation: “When we are in the slow season, which happens in television all the time, everybody has to be laid off. We were going to keep people busy on the feature. We found that doesn’t work. The kind of people you use on a feature are the old super-pros of our industry, and there are few of them left.

“Secondly, we wanted to use HEIDI’S SONG as a training ground for new animators. The first three or four years the picture would go into production and stop, then go back into production and then stop. That was not good for the picture. We were losing momentum, the enthusiasm of the artists and the excitement we wanted to build up. So finally, about a year and a half ago, we marshalled the last remnants of

__Bob Taylor, director, and animators____ what we think are the best people in the

__Charlie Downs and Hal Ambro. ________business. When we brought these people in we had to change directors. We had a fine guy, but he had forgotten how to go back and really work these old-timers — really get the good animation! We then hired a brilliant young director, Bob Taylor, who is dynamite!”

Prior to rejoining H-B a couple of years ago (he had first worked there in 1966 for one year), Robert Taylor worked for Ralph Bakshi, Steve Krantz, DePatie-Freleng and Murakami-Wolf. “I always seem to come in on things that are hopeless,” he commented recently, “and we try to turn them into hopeful. I think we’ve done it with this picture. For me and the whole crew, and for Joe and Hanna-Barbera and Taft, this is our entrance into real good quality stuff!”

It has not been a piece of cake for Taylor. When he took on the HEIDI assignment, the script was written and the tracks were already recorded. “It was a hang-up for me,” he admits. “That’s the albatross around my neck. The story is episodic. If I had written it, I would have made it a little stronger in terms of her emotions and some of the dialogue. But,” he adds brightly,

I “my whole trip is to keep the audience entertained—get people to go to animated films and make them feel when they come out that they’ve seen something they can’t see anyplace else. It isn’t so much the tools;

i it’s what the hell I’m trying to do with it.”

Trying to elicit a description of the film’s style from both producer and director is difficult. According to Barbera, “The results have been what I call a Hanna-Barbera feature. It is not going to look like a Disney picture, or a FRITZ THE CAT or a RAGGEDY ANN & ANDY. We have our own style.” When pressed, Barbera cites “some very imaginative pieces of business.” Pressed further: “We’re not holding back. When they lock Heidi in the cellar, that’s a scary place—to be locked in a basement in a house in Frankfurt in the 1880s, that’s enough to put you away. We’re not holding back, yet we’re keeping it in good taste throughout.”

New wave animation

Taylor was a bit more specific: “I hate to opportunity for the guys to get back into what it’s really all about. We take as many new animators as we can bear—the ones that have the enthusiasm and are really interested in what we’re calling a ‘renaissance.’ But even more important, we are just interested in making great animated films and updating them into the 1980s.”

The HEIDI unit has already begun production of its next two animated features, ROCK ODYSSEY (which Barbera describes as “a marvelous treatment of music from the 1950s, ’60s and 70s. A rock-FANTASIA, if you want to call it that”), and NESSIE COME HOME, a tale about the Loch Ness monster. Again, the thinking behind the choice of both projects is carefully calculated toward maximizing box office. “If you are going to do a feature,”reasons Barbera, “you must have something people will identify with. You can’t do ‘Willie the Glowworm!’ That’s why HEIDI is so great. It’s always a problem finding material. Watership Down is a marvelous book, but we would have hesitated to do it because it’s just not that well known. It’s a gamble. You have to put four to five million dollars into something like that.”

Marketing concepts for animated features

At a time when Disney films are attempting to woo an older (“PG”) audience, one wonders why Hanna-Barbera appears to be aiming toward a traditional, family-oriented “G”-rated audience with its animated features. Barbera explains: “First of all, anything that Disney has done is going to play forever, so he will have that constant market in every media. Secondly, the theater audience isn’t going to be the only audience. There are going to be cassettes, a perennial that will run forever. And thirdly, we are going to have our own style. We’re not going to have a picture that will be only for kids. We will get the adults with this one.”

“ROCK ODYSSEY,” continues Barbera, “will appeal to those between the ages of 18 and 35, but we will not lose the kids because of the animation. And we will have the adults that remember those ’50s and ’60s songs. NESSIE will have a great, I hate to use the word, ‘environmental’ appeal, but we will be protecting a character that’s getting it. If there are monsters in that lake, they get bothered—by submarines, depth bombs, cameras—more than any character in the world. We have a very unusual twist that will make it appealing.”

Joseph Barbara, executive producer, displays color models that some

150 animators used for reference while working on HEIDI’S SONG.

Asked whether the future might see Hanna-Barbera producing adult-oriented features a la Bakshi, Barbera answers, “Oh yes, very much! We had a recent all-day meeting where the thrust was the fact that we can’t depend on the children audiences to pay for these things. We must attract the adults, too. Statistics show there are less children around now. So whatever we do, we must attract the adults.” Barbera must have been thinking of a recent Bakshi product, i.e., LORD OF THE RINGS, for when asked if he would produce an unquestionably adult cartoon such as HEAVY TRAFFIC or FRITZ THE CAT, he replied, “No! I don’t think we would do that! We certainly wouldn’t shy away from a gutsy project, but it must bring in the kids, too. So there would be no bad taste.” For the time being, it is significant that Hanna-Barbera is training an enthusiastic crew in the techniques of full, character animation, one form of the art that for the last two decades has seemed to teeter constantly on the brink of extinction. It is enough for now that H-B is producing with integrity and care a film like HEIDI’S SONG, which will attract and appeal to large audiences.

The success of Hanna-Barbera will keep an avenue open for future animated features, and hold the public’s awareness of and interest in the medium of animation itself. With an increase in the number of future animated features will come diversity in form and content. Animation

as a vital and viable entertainment medium will then come closer to realizing its potential, as it did in 1968 when George Dunning directed YELLOW SUBMARINE, and in the early 1970s, when Ralph Bakshi excited audiences, and, indeed, as in 1937 when a struggling young producer named Walt Disney redefined the genre.

Animation Artifacts &Richard Williams 22 Aug 2007 08:41 am

More Ragged odds & ends

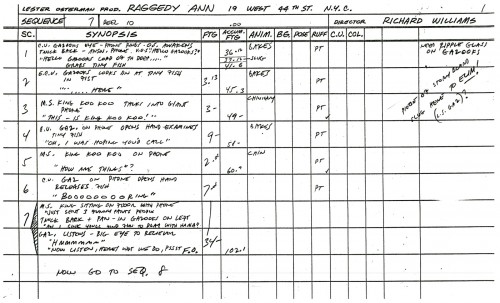

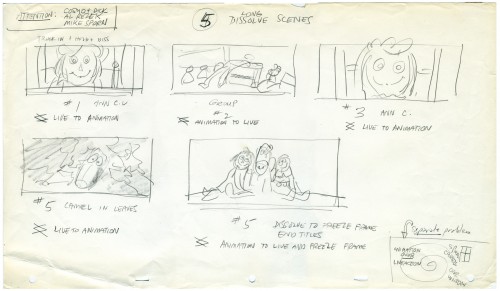

- Aside from the usual models that came my way on Raggedy Ann and Andy: A Musical Adventure, I was privy to a lot of private notes, cartoons and comments by some of the upper echelon, and I have all the production charts and drafts (which I’ll spare you) so that I can verify any info I’m sharing. I’ve chosen a couple of items to post today just as curiosity pieces.

Part of my job on the film was overseeing special effects (shadows, stars, etc.).

Dick gave an improvised storyboard, during one of our meetings, in which he detailed

all the combination live action/animation shots. Listed to receive this item are Al Rezek,

our camera supervisor, and Cosmo Anzilotti, the Asst. Director of the film.

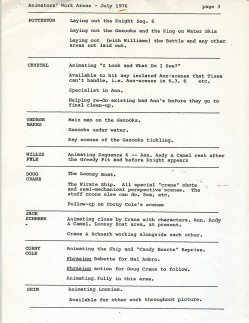

About six months into animation, crisis mode started to set into the production. It was w a y behind schedule, and they were constantly searching for ways to move things along. At one point it was decided that more clarification was essential so that everyone would share in the same knowledge. Dick Williams prepared the following document to define what the animators would be doing for the remainder of the project.

Needless to say things changed from this plan.

The animators listed in order are:

Tissa David, Art Babbitt, Spencer Peel, Hal Ambro, Charlie Downs, Gerry Chiniquy, John Kimball, Warren Batchelder, Tom Roth, Dick Williams, Emery Hawkins, John Bruno, Gerry Potterton, Crystal Russell, George Bakes, Willis Pyle, Doug Crane, Jack Schnerk, Corny Cole, Grim Natwick, Cosmo Anzilotti, and Art Vitello.

To my knowledge, Jerry Hathcock, Jan Svochak, Bill Hudson, Jack Stokes, Terry Harrison, and Michael Lah didn’t work on the film even though they were all approached.

Not listed here is Irv Spence who did quite a bit of animation.

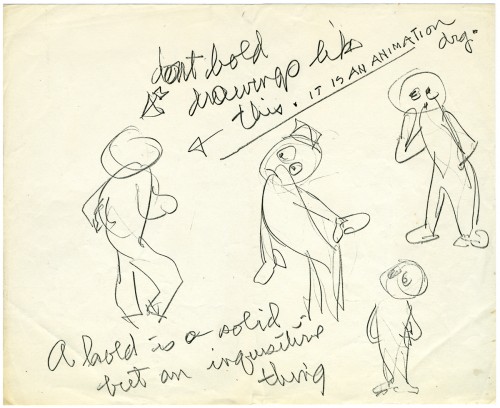

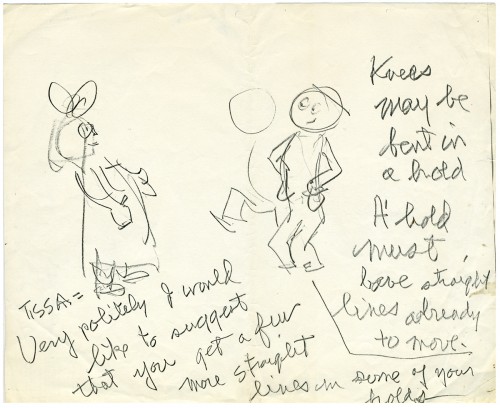

Grim Natwick wrote a note to Dick a couple of months after the start of animation commenting on some of the animation problems he saw. It was done very large on

16 fld animation paper. (Grim always seemed to write LARGE.)

Grim’s note ends with a personal comment to Tissa David. A note from mentor to student.

It just goes to show you can always get animation lessons no matter how old or important you are.

Stay humble.

Happy Birthday, George Herriman

Animation &Animation Artifacts &Models &Richard Williams 21 Aug 2007 07:22 am

Raggedy Models

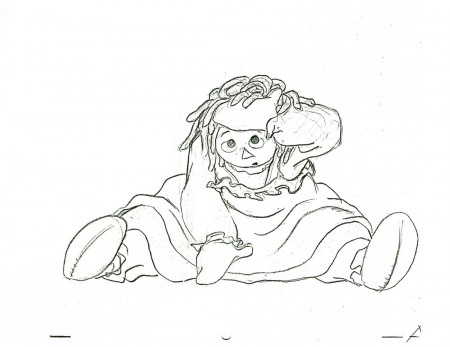

– As I posted last Friday, to celebrate the 30th Anniversary of Raggedy Ann & Andy: the Musical, I’m going to post a bunch of artwork from this film. I’m not even sure much of this material is of interest to anyone but those who worked on the movie, but since I worked on it, I’m interested.

– As I posted last Friday, to celebrate the 30th Anniversary of Raggedy Ann & Andy: the Musical, I’m going to post a bunch of artwork from this film. I’m not even sure much of this material is of interest to anyone but those who worked on the movie, but since I worked on it, I’m interested.

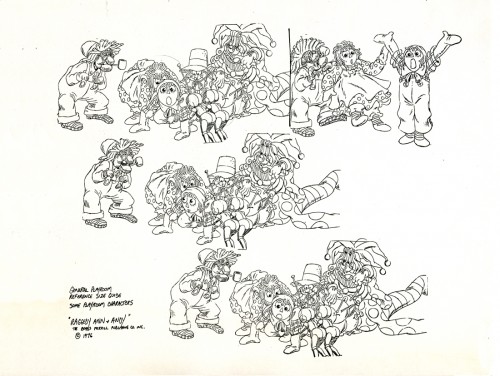

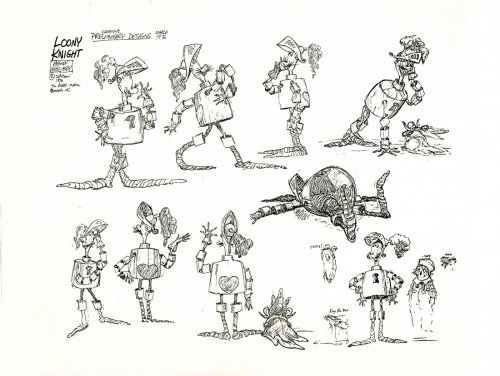

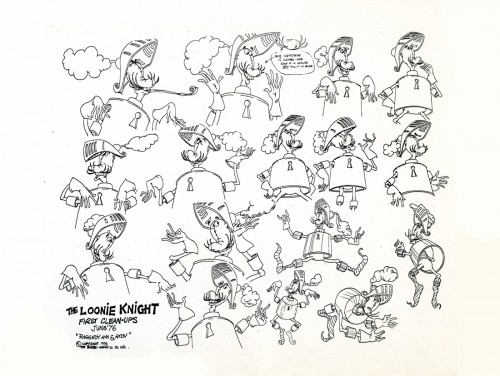

Here are a bunch of model sheets of the secondary characters. The film opens in a playroom, and lots of toys inhabit these first few minutes. They all suffer from the same problem – too much. There are too many lines, there were too many colors, there was too much flailing-about animation. It would have been better to keep it a bit quieter, but that was never the Dick Williams way.

Here they are, right off Xeroxed copies:

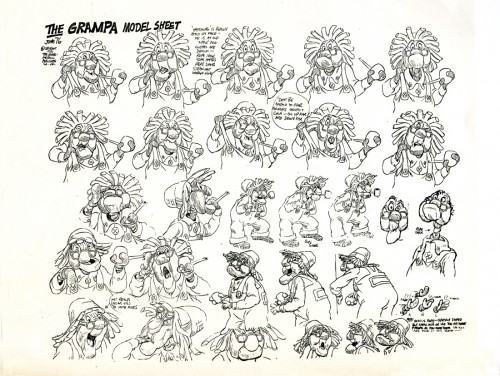

Most of these model sheets were pulled from completed animation. In the case of this

group shot, Dick Williams did these drawings in reworking Fred Helmich’s animation in

the “No Girl’s Toy” musical number.

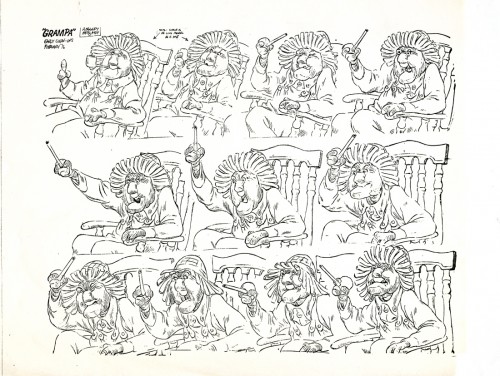

I really have to encourage you to click these images to enlarge. Gramps is the

perfect example of the brilliant detail that Dick Williams put into his animation.

Both these Gramps model sheets represent separate scenes. Most of the key drawings

from the scenes were placed on these models.

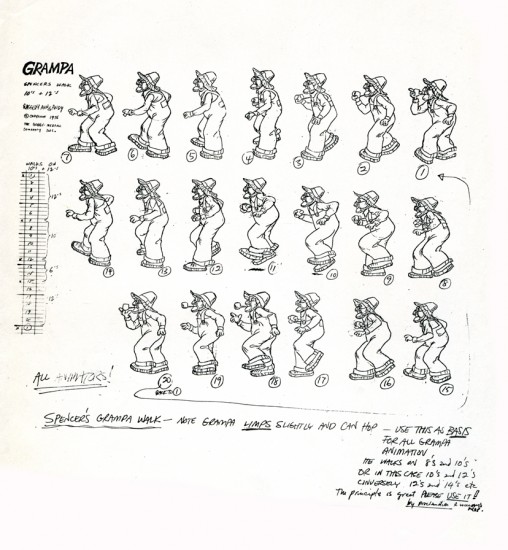

Here’s the walk cycle of Gramps done by Spencer Peel and approved by Dick Williams.

Hal Ambro did the animation on the Babette character, at least in the opening of the film where it was good. Dick Williams did the clean-up and inbetweens, himself.

Dick’s clean-up did a stunningly brilliant job of locking in this character. I’m not quite sure we had anyone else on staff who could have done this character as well. Dick Williams is

an enormous talent, but it was too bad he was limited to inbetweening.

Maxi Fix-it was a nothing of a character, yet he involved endless energy in animation and clean-up. No wonder the film’s budget quadrupled during production, and it wasn’t enough.

Susie Pincushion was just another character who had 22 colors on her.

The drawings that were used for this preliminary model sheet were by designer, Corny Cole. What a talent! The character looks as though it could have fallen out of the oriiginal books by Johnny Gruelle. The life in each and every one of these drawings was solid gold. Too bad it ended up such a lifeless and annoying character when it finally hit the screen.

The clean up guide for the knight shows you what’s been lost.

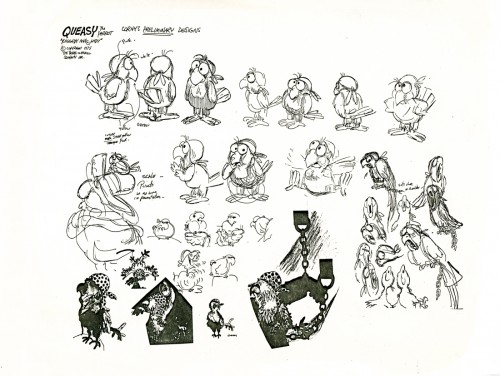

Queasy was the parrot that sat on the Pirate’s shoulder. Arnold Stang did his voice.

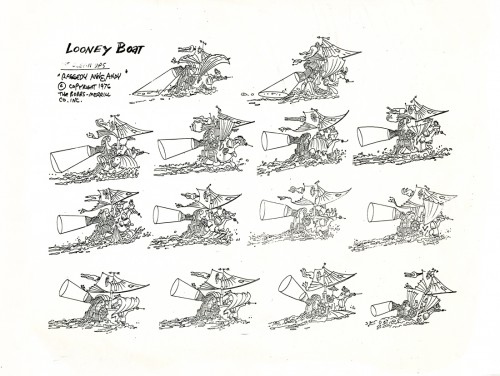

The animation of the pirate ship was split between Corny Cole and Doug Crane. I have

a couple of scenes done by Corny with his Bic pen animation. Someday I’ll post some of these drawings, but it’ll be a big chore to do it. Each drawing is so large that it’ll take three scans for each one and will require photoshop reconsrtuction. Lotsa work.

But they’re beautiful drawings, so it’ll probably be worth it if I can find the time.

Animation Artifacts &Layout & Design &Richard Williams &Story & Storyboards 17 Aug 2007 07:41 am

30 Raggedy Years

– Tom Sito‘s blog, yesterday, reminded me that it was the 30th anniversary of the release of Raggedy Ann & Andy:A Musical Adventure .

– Tom Sito‘s blog, yesterday, reminded me that it was the 30th anniversary of the release of Raggedy Ann & Andy:A Musical Adventure .

To quote Tom’s blog:

___ASIFA/Hollywood is planning

___to have a reunion of the crew of

___Raggedy Ann to celebrate the

___anniversary. It will be at the

___American Film Institute in

___Hollywood on November 17th.

___A simultaneous reunion will

___happen in New York City. A lot of wonderful people worked on this film, many getting

___their first start.

This gives me a good reason to post some artwork from this film in the next few months. So, excuse me if you find it annoying to see artwork from a second rate feature. However, this was a seminal film for a lot of talented people who got a chance to work along some of the masters.

Just check out this list of animators on the film:

_____Hal Ambro, Art Babbitt, George Bakes, John Bruno, Gerry Chiniquy,

_____Tissa David, Emery Hawkins, John Kimball, Chrystal (Russell) Klabunde,

_____Charlie Downs, Grim Natwick, Spencer Peel, Willis Pyle, Jack Schnerk,

_____Art Vitello, Carl Bell and Fred Hellmich left mid-production.

_____Gerry Potterton was the consulting Director.

_____Cosmo Anzilotti was the Asst. Director.

_____Corny Cole was the designer of the film.

These were some of the younger upstarts inbetweening and assisting:

_____Bill Frake, Jeffrey Gatrall, John Gaug, Eric Goldberg, Dan Haskett, Helen Komar,

_____Judy Levitow, Jim Logan, Carol Millican, Lester Pegues Jr, Louis Scarborough Jr,

_____Tom Sito, Sheldon Cohen and Jack Mongovan.

_____I supervised assistants and inbetweeners in NY,

_____Marlene Robinson did that job in LA.

If you don’t know who these people are, trust me they were the backbone of the business for many, many years prior to 1976.

In some ways I think this along with some of the Bakshi and Bluth films led directly toward the rebirth of animated features. There was a long dark period before it.

So to start with the artwork.

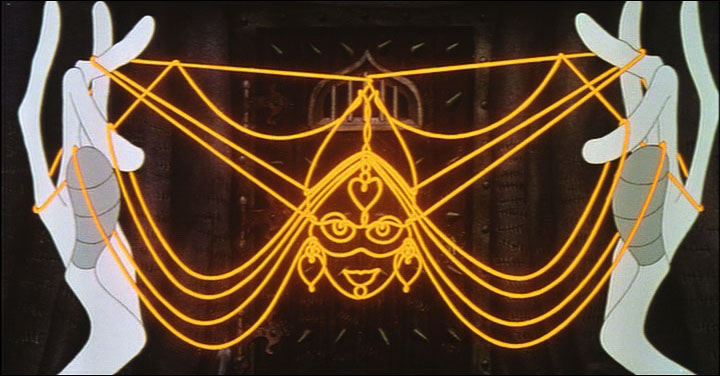

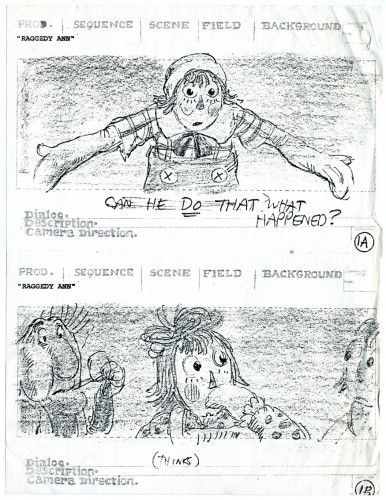

This is a scene which immediately follows the Pirate kidnapping Babette.

Here’s the storyboard for the two scenes. It’s a copy of

Corny Cole’s drawing from the director’s workbook.

This is Corny Cole’s layout for Sc. 1A.

Here we have Dick Williams’ reworking of the same pose.

Fred Hellmich originally animated this, but Dick Williams redid the entire sequence, and

Fred left the film.

Cut back to Andy (as drawn by Dick Williams) for Sc. 2.

How small it all gets on a pan and scan video.