Category ArchiveArticles on Animation

Articles on Animation &Bill Peckmann &Disney &Illustration &Mary Blair 19 Aug 2009 07:33 am

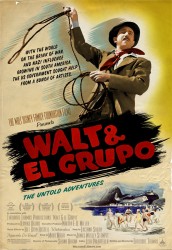

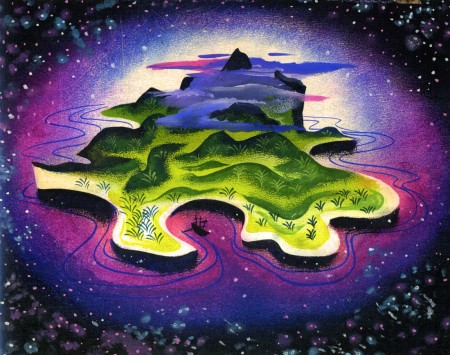

El Groupo & Mary Blair’s Peter Pan

- Yesterday I saw a preview screening of Walt and El Groupo. This is a documentary exploration of the Disney trip to South America to bring back material for Saludos Amigos and Three Caballeros. If you have any interest in Walt Disney or the history of his studio or Mary Blair, you’ll have to see this film. It features interviews with a number of the children of those who went to South America with Disney. Interviews with those who hosted Disney talk about the visit.

- Yesterday I saw a preview screening of Walt and El Groupo. This is a documentary exploration of the Disney trip to South America to bring back material for Saludos Amigos and Three Caballeros. If you have any interest in Walt Disney or the history of his studio or Mary Blair, you’ll have to see this film. It features interviews with a number of the children of those who went to South America with Disney. Interviews with those who hosted Disney talk about the visit.

The film is shot in a beautifully lush color that is almost reminiscent of IB Technicolor. One would expect the home movies to be grainy and unattractive, but instead they’re gorgeous.

The film is worth the visit. It’ll open in NY & LA on Sept. 11th. I’ll write more about it as the event gets closer.

There’s also upcoming a screening for MOCCA, the Museum of Comic and Cartoon Art featuring a Q&A with writer/director Ted Thomas and producer Kuniko Okubo, moderated by John Canemaker. This will take place on Thursday, August 27th, 7:30 PM at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, BAM Cinema 4, (30 Lafayette Avenue, Brooklyn, NY).

Admission is free for Members of MoCCA. To rsvp, call (212) 254-3511.

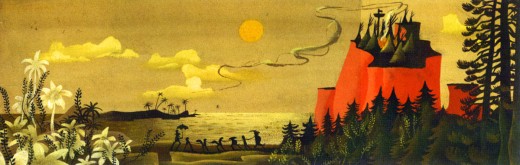

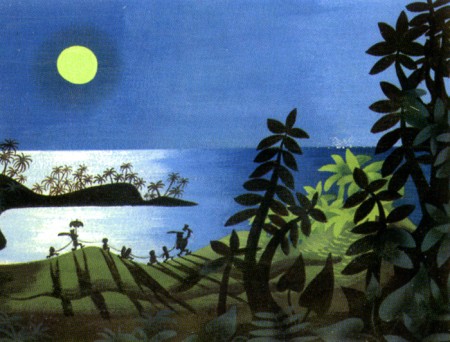

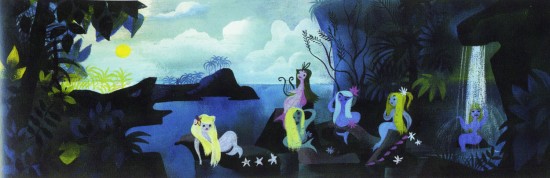

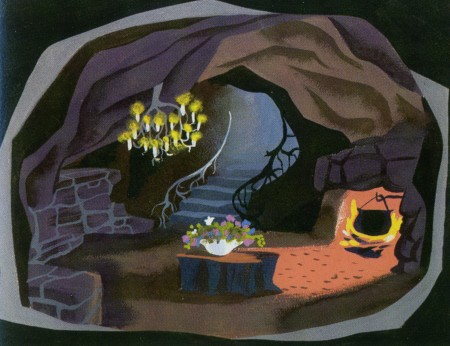

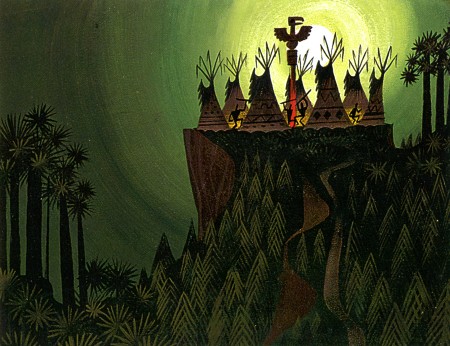

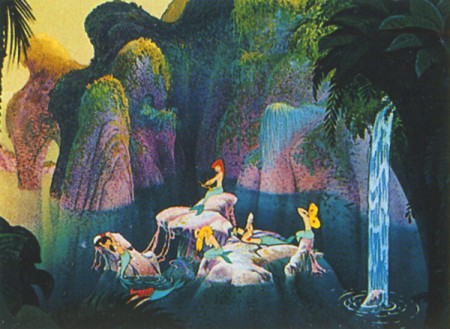

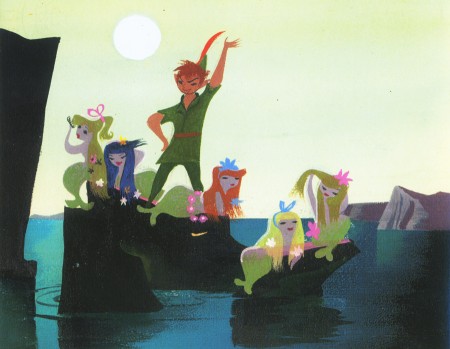

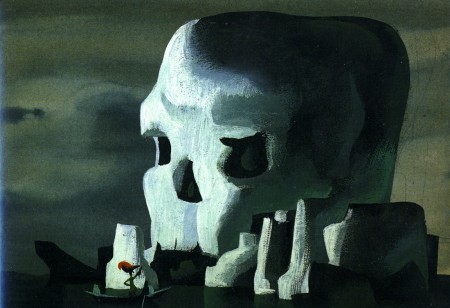

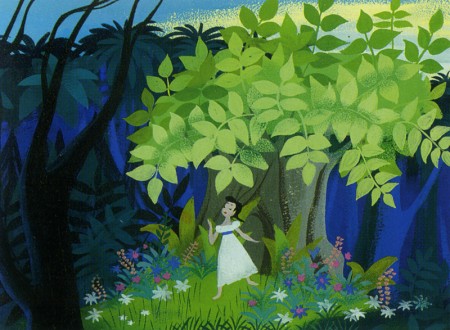

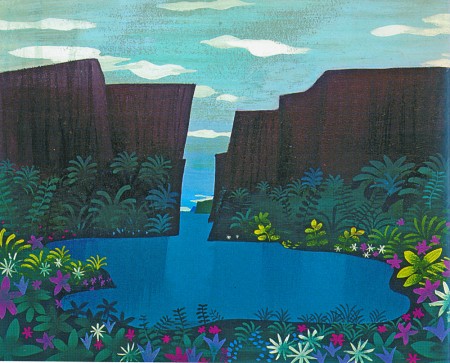

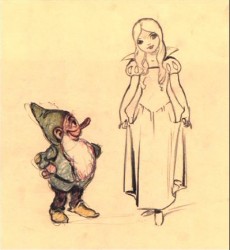

- In tune with the above comments and having posted, this past week, the wonderful 1940 model sheets from Disney’s Peter Pan (thanks to Bill Peckmann and his fine collection), I thought about the Mary Blair art for this film. Neither those model sheets nor Mary Blair’s art made it to the film.

- In tune with the above comments and having posted, this past week, the wonderful 1940 model sheets from Disney’s Peter Pan (thanks to Bill Peckmann and his fine collection), I thought about the Mary Blair art for this film. Neither those model sheets nor Mary Blair’s art made it to the film.

I thought, as a companion piece to those early model sheets, I’d post the Peter Pan illustrations in John Canemaker‘s fine book: The Art and Flair of Mary Blair. A number of these have been used to illustrate the new book, Walt Disney’s Peter Pan. They’re all attractive and modern in style. I think the film took the colors without the style and came up with a picture postcard look.

Here are Mary Blair‘s paintings:

(Click any image to enlarge.)

Articles on Animation 15 Aug 2009 07:03 am

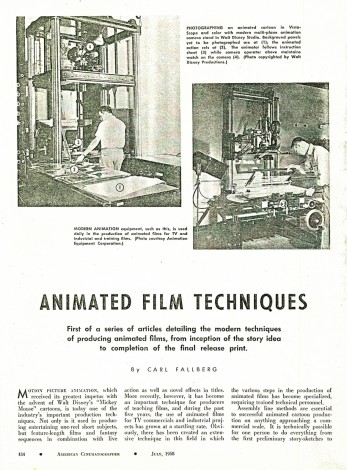

Animated Film Techniques

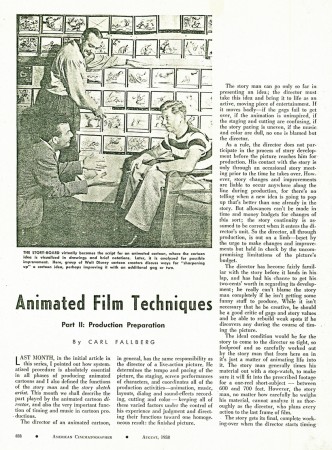

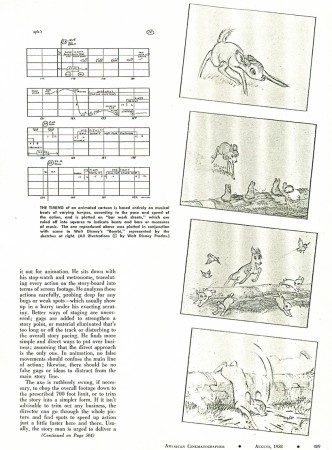

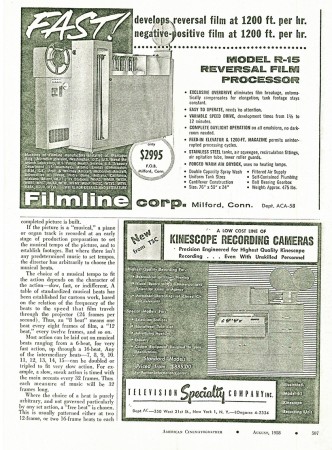

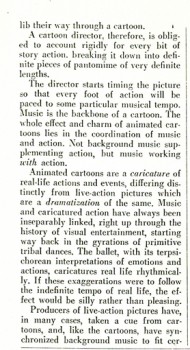

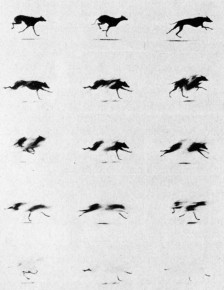

Here’s an old article from American Cinematographer Magazine. Published in 1958, it continued through four separate issues of the magazine. Written by Carl Fallberg, the article tries to detail the methods of animation production. Animated Film Techniques

This is a very old xerox copy, so I apologize for any quality problems. Here’s the first two parts of the article. The next two will come next Saturday.

1

1(Click any image to enlarge to a legible size. ___

3

3

Articles on Animation 12 Aug 2009 07:40 am

Wartoons

I wish that the article were a bit more of a commentary from the German viewpoint. I’d like to hear their opinion of some of this obviously biased material. There were also some well chronicled animated propaganda that came from the German side.

Two stills from Trnka’s The Springman and the SS

This film includes the horrific image of 2 GAY Nazis !

The DVD Cartoons for Victory! (from Thunderbean Animation) includes a number of these films from both sides. There are a number of Private Snafu shorts, Jiri Trnka’s The Springman and the SS, Hans Fischerkosen’s Der Schneeman and Nimbus Libere (another Nazi propaganda short).

Thanks to Kathy Ryan for pointing me in the right direction for the Der Spiegel article.

Much more has been written about this subject at David Lesjack‘s excellent blog, Toons at War blog. This is a site I’d encourage you to view often. Material like the image below are frequently featured there.

______________________

Congratulations to those New Yorkers who got films in competition in the upcoming Ottawa Animation Festival. They include:

- Fran & Will Krause

Jake Armstrong

Jennifer Oxley

Mike & Tim Rauch

Signe Bauman

Articles on Animation 11 Aug 2009 07:24 am

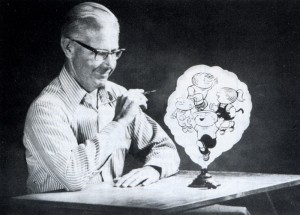

Jules Engel on Teaching / 1976

- Here’s an article from the Feb. 1976 issue of Millimeter. It’s part of an article written by three separate Animation instructors: Yvonee Anderson (Yellow Ball Workshop), Greg Shelton (J.Marshall High School, Ind.), and Jules Engel (CalArts).

This is the piece written by Mr. Engel:

________________________________ by Jules Engel

When the Polish animator Jan Lenica toured America last year, he ended up in Los Angeles and came to visit California Institute of the Arts. After seeing a program of films made by the animation students at the Institute, he exclaimed in astonishment, “But these are not student films; they are films by artists! And here in Hollywood! Who would have thought?”

When the Polish animator Jan Lenica toured America last year, he ended up in Los Angeles and came to visit California Institute of the Arts. After seeing a program of films made by the animation students at the Institute, he exclaimed in astonishment, “But these are not student films; they are films by artists! And here in Hollywood! Who would have thought?”

Lenica is not the only one to have said this about Cal Arts and its animated “student” films, but the comments of so great an artist are particularly gratifying—and particularly revealing.

I began working with animation at the Disney Studios in the 40′s when FANTASIA was under production. I was one of about I200 people employed in the Disney

________ Jules Engel ___________ Studio—many of whose names are never recorded, though their contributions to the artistry of the films was considerable. I was hired as a choreography consultant for the Chinese and Russian dancers in the “Nutcracker Suite,” but

I drew out exacting choreography sketches for both sequences—up to 50 pictures for a one-minute movement—which were then passed on through countless hands (background artists, character animators, in-betweeners, eel painters, etc., etc.) before the finished film was able to be seen. Miraculously, many of my original conceptions—for example, the pure black backgrounds for the low-angle perspectives on the twirling Russian flowers—and the choreography on the Chinese and Russian dance actually survived into the final product!

I drew out exacting choreography sketches for both sequences—up to 50 pictures for a one-minute movement—which were then passed on through countless hands (background artists, character animators, in-betweeners, eel painters, etc., etc.) before the finished film was able to be seen. Miraculously, many of my original conceptions—for example, the pure black backgrounds for the low-angle perspectives on the twirling Russian flowers—and the choreography on the Chinese and Russian dance actually survived into the final product!

Later we founded UPA and opened up other possibilities of this much-maligned medium. With only about a handful of people, we were able to produce artistically integrated works. As a measure of our success, people quickly came to regard American animation in terms of two poles — ________ Engels “Accidents”

the Disney style, and the UPA style (always different,

with a range of subject matter and visual technique as broad as Modern Art itself). And “Disney” soon enough came under the influence of UPA by introducing more stylized elements into their previously realism-oriented product.

After UPA, I produced animation films independently with my own Format Films, including, in addition to Popeye cartoons and various commercials, a film based on a Ray Bradbury story, Icarus, which won an Academy Award nomination and a Gold Medal at the Atlanta Film Festival.

I had been offered jobs teaching painting and sculpture many times, but I had always refused, because I don’t really believe you can teach “art.” The ideas, feelings and meanings of artwork must come from inside the artist. You learn concepts and attitudes, techniques and materials of production. It is always better for the artist to learn about his art by trial and error. We learn through experience and experiencing.

But Cal Arts is different. When Anais Nin recommended me to Herb Blau, and then Robert Corrigan asked me to develop an animation program there, I accepted because I knew I wouldn’t be expected to teach “how” or “what” since the school is conceived as an artists’ conglomerate, as a co-operative workshop where painters and dancers, musicians and actors, philosophers and filmmakers could share their talents and experiences with each other. If one learns by a “how to do” method, one does not reveal one’s self, one only reveals the skill for doing.

Don’t take—search!

I don’t call myself a teacher, and I don’t consider the people I work with as students. They are “talents” or “artists” or “friends.” I hate to hear people say, “I taught him everything he knows.” That’s not education. In the first place, if “everything he knows” can be measured and categorized so easily, “it” must not be too much or too complex, and in the second place, education should be a process of opening and broadening horizons, so if “everything” has supposedly already been “taught,” the process must have been one of closing off possibilities rather than opening them up. Furthermore, a “student” must always have the feeling that he is working for and by himself, developing his own potentials, his own initiatives, his own ideas—not being obliged to or dependent on a “teacher.”

At Cal Arts I have something of an ideal situation. The working environment is not classroom oriented—but more like a working artist’s studio. It is an environment in which experiencing can take place. Studio is open 24 hours and seven days a week. An artist has no limits of working hours! Almost all of the exchange between me and my “talents” is on a one-to-one basis, since out of the 30-or-so talents I work with each year, there are maybe 20 different directions they want to go in.

I never discourage people, and I never force them. Work with the talent where he is, and not where you think he should be. I like to take chances on people and let them find out how they feel about animation. I encourage them to play around with the medium, and some fall in love with it while others learn that it’s not really a vehicle they find satisfying or profitable for their ideas or capabilities. In addition to my 30 full-time talents, I usually have I0 or I5 other talents who come in from other schools (dance, music, design, art) to try out animation. I never say no to anyone, because, after all, with young talent who can say which one is going to develop into something great? I end up working with a Jot of talents. I’m looking for the innovators, (as well as for the craftsman), the dreamers, the leaders. The great artists of animation—the Lenicas, the Fischingers, the Kuris, McLarrens, Hublys, Disney, undoubtedly weren’t model students (and maybe weren’t even pleasant people) because their genius was too eccentric. They broke all the rules, and invented new ones, and that’s precisely why we admire them.

The talents I have come to me from widely varying backgrounds, too. Dennis Pies, for example, had four years of art school behind him and wanted to explore film as a means of adding a controlled time dimension to his paintings, which he did beautifully in films like Aura Corona. Kathy Rose, with a background of a dancer, came on as one of the most intuitive creative artists, winner of the Gold Hugo—at Chicago International (Mirror People). Jane Kirkwood had no experience at all with drawing, yet she produced a superb, award-winning film, drawing for An Exhibition, proof once again that animation is far from synonymous with drawing. Disney himself couldn’t draw all that well. So what!? He was an entertainer. He had the instinct of an actor—and an inspired director. He needed the craftsmen to complete his dreams.

Films produced by students at California Institute of the Arts

Each talent has his own rhythm as well. It takes some people months to get acclimatized to the kind of freedom that I offer in order to find themselves on all levels: intellectual, spiritual, and intuitive. The artist has to discover for himself his own road. Then some talents work very slowly or irregularly, while others like the prodigious Adam Beckett have spent hundreds of hours laboring every day on the drawing board, the Oxberry and the optical printer for each of his five films. The most important part of teaching is not in reading and lecturing or even looking at films, but the actual “doing” of the film.

There is no competition in our classes, either. Competition creates a false sense of artificial tension which might be all right in sports where competitive performance is the only way to demonstrate your skill, but not in art where individuality and individual expression is supremely important. I don’t bother pointing up the talents’ bad points, since they stumble over those soon enough by themselves; I prefer to point up the good points and build on them—to give the talent a confidence in-themselves.

We have excellent equipment and I put together a fine collection of animation films which I show to the talents, and later they can study them for themselves, frame by frame, if they want, on the viewer in the library. We also have guest animators—Americans Mary Ellen Bute and Elfriede Fishcinger, Dragich and Matko from Yugoslavia, Richard Williams and Bob Godfriend from England, Yoji Kuri from Japan, and Dale (Further Adventures of Uncle Sam) Case, Leo Salkin, Herb Klynn, from right here in Hollywood.

Is our program successful? I think our films attest to that. And our talents have had no trouble finding jobs. Joyce Borenstein, for example, is already working for the National Film Board of Canada. If she had tried to learn animation through the studios, she would have spent five years as an in-betweener and five more years as an assistant animator before getting that precious director’s status-symbol, the stopwatch, which they can get the first day in my class and learn to use it at their own pace and in their own way. One day a beginning talent came to me and said, “Oh, I’m sorry about this; look at the mistakes I’ve made!” “No,” I told him, “you can’t make mistakes at this early stage. Mistakes you make later when you know better.” But strange to say, they don’t seem to get around to making too many mistakes later either.

Articles on Animation &Disney 06 Aug 2009 07:10 am

Gilbert Seldes meets Walt Disney

- As a young boy growing up in the far upper reaches of Manhattan I lived for animation. I watched the limited fare offered on television (usually B&W Warner Bros cartoons, the Disneyland TV show on Wednesday nights, early Saturday morning cartoons – Mighty Mouse show being the best of the lot) or I went to the library and to borrow any book I could locate that mentioned the medium.

There were half a dozen books back then, and I probably memorized the lot of them in short time. (I suspect I was the only one borrowing those treasured books.) I remember when I came across a book of collected essays by the film critic, Gilbert Seldes. In this book, The 7 Lively Arts, there was a chapter on Walt Disney. I read and reread it carefully and thoroughly, and I enjoyed it immensely. I’ve recently run into it again (in a different form – he reworked it for the book since that version covers quite a bit more than the very earliest years) in the New Yorker Magazine’s archives. Not bad reading on this rainy day in New York, so I thought I’d share it.

Remember this was written in 1931 when the studio really was just in its earliest phases. Mickey Mouse was barely two years old.

From the Dec. 19, 1931 issue of the magazine:

- IN the current American mythology, Mickey Mouse is the imp, the benevolent dwarf of older fables, and like them lie is far more popular than the important gods, heroes, and ogres. Over a hundred prints of each of his adventures are made, and of the fifteen thousand movie houses wired for sound in America, twelve thousand show his pictures. So far he has been deathless, as the demand for the early Mickey Mouses continues although they are nearly four years old; they are used at children’s matinees, for request programs, and as acceptable fillers in programs of short subjects. It is estimated that over a million separate audiences see him every year.

- IN the current American mythology, Mickey Mouse is the imp, the benevolent dwarf of older fables, and like them lie is far more popular than the important gods, heroes, and ogres. Over a hundred prints of each of his adventures are made, and of the fifteen thousand movie houses wired for sound in America, twelve thousand show his pictures. So far he has been deathless, as the demand for the early Mickey Mouses continues although they are nearly four years old; they are used at children’s matinees, for request programs, and as acceptable fillers in programs of short subjects. It is estimated that over a million separate audiences see him every year.

Thirteen Mickey Mouses are made each year. Tin- same workmen produce also thirteen pictures in another series, the Silly Symphonies, so that exactly fourteen days is the working time for each of these masterpieces which Serge Eisenstein, the great Russian director, called, with professional extravagance, America’s most original contribution to culture. The creative, power behind them is a single individual, Walt Disney, who happens to be such a mediocre draughtsman, in comparison with the artists he employs, that he never actually draws Mickey Mouse. He has, however, a drop personal relation to the creature: the speaking voice of Mickey Mouse is the voice of Walt Disney.

HE is a slender, sharp-faced, quietly happy, frequently smiling young man, thirty this month. He is married to Lillian Marie Hounds, whom he met in Hollywood, where she was probably unique, as she had nothing to do with pictures. She has enough to do with them now, because she is the first receiver of her husband’s ideas. Mickey Mouse pictures are talked into being before they are drawn, talked and cackled and groaned and boomed and squeaked and roared and barked and meowed, with ever}- variation of animal sound, with appropriate gesture, and with music. If strange outcries anil queer noises waken Mrs. Disney at night, it is only Walt working on a new story. He never stops; he swims and rides and lie plays baseball with his stall, but all the time he is inventing. He is one of the lucky ones who can make a fortune out of the work the) love and he does not love Mickey for his wealth alone. He was just as keen when exhibitors refused to look at the Mouse, and just as keen over earlier efforts which were, as he now says, “pretty awful.”

He is fortunate also in having as his chief co-worker his elder brother, who is the businessman of the firm. Roy Disney and five assistants attend to finance; Walt and about a hundred others—a quarter of them are artists, the rest are gagmen, story-men, and technical experts— make the picture’. ‘The distribution and sales are in other hands.

When a Mouse or a Silly Symphony is finished, the business side and most of the artists watch it carefully for commercial value, for those mysterious qualities which they think, or guess, will make it popular. They find their congratulations to Walt Disney accepted without enthusiasm. He is not putting on artistic side; he is not indifferent to profits. What he is frequently doing is referring each finished picture back to the clear idea with which it started, the thing he saw and heard in his mind before it ever came to India ink and sound tracks. In the process of making the picture, something often escapes, and Disney wanders moodily away from the projection-room grumbling: “Where did it go to?” and often will begin outlining the original idea again, with gestures and sound effects, to prove that he is right.

THE mechanics of creating Mickey Mouse are complicated and, to the workers, tedious. Six or seven drawings are required for every movement, and the first and last, the position of thr Mouse at the beginning and at the end of any motion, are drawn by the principal artists, or “animators.” After them, the “in-betweeners” fill the intervening space, with minute changes in the figure. The final step in preparing for tin camera is the photographic transfer of these drawings to celluloid. As the background changes less frequently, dozens of celluloid drawings ma)’ be placed over a single background scene.

The drawings are now ready for the camera, which photographs each separately. The tracing of the moving figure is placed on its background, the photograph is taken, and the next drawing is moved into position. About eight hundred photographs can can be taken in one day —- some fifty feet of film.

The sound track is made after the picture has been completed. A short section of the film is projected; the music, which has been selected in advance, is rehearsed by musicians, who watch the screen as they play; and when the timing has been perfected, the music is recorded.

The two advantages of the animated cartoon over the feature picture are only implied in the above description: there are no stars and only *as much film is taken as will be used, A few feet arc allowed for adjustments, but the filming of a hundred and fifty thousand feet for a six-thousand-foot picture does not occur.

WALT DISNEY is, as I have said, thirty, and that means that he is too young to have had a history, too young to have developed oddities and idiosyncrasies. He is a simple person in the sense that everything about him harmonizes with everything else; his work reflects the way he lives, and vice versa. Mickey Mouse appears on the screen with features and Super-specials, but Mickey Mouse is far removed from the usual Hollywood product, with its sex appeal, current interests, personalities, studio intrigue, and the like. And Disney, living” in Hollywood, shares hardly at all in Hollywood’s life. He has not only made a lot of money (between forty and fifty per cent of the return on each film is net profit) better than that, his potential income is enormous: he has the surest bet in filmdom; experts think that he is only at the beginning of his great success. In these circumstances, Hollywood builds itself a palace and a pool; Disney lives in the house he built five years ago when he and his brother were too poor to buy a lot for each, and combined on a corner that both the houses they built would have, sufficient light and air. His house is a six-room bungalow, the commmoner type of middle-class construction in Hollywood; the car he drives is a medium-priced domestic one; his clothes are ordinary. He goes to pictures, but rarely to the flash openings; he neither gives nor attends great parties. Outside of the people who work with him, he has few friends in the industry. The only large sum of money he ever spent was one hundred and twenty-five thousand dollars; it was the cost of his new studio. Everything he earns and everything his brother earns, on the fifty-fifty basis they established years ago, is reinvested in the business.

Walt Disney’s life before he went into movie-making divides into two almost equal and almost entirely un-distinguished section. He was born in Chicago In 1901, his father .was an Irish-Catholic builder and. contractor, his mother a German-American. He went to the Chicago Public. schools and studied drawing for a few months at the Art Institute. Arguing, perhaps, from his present enthusiasms, friends of the Chicago days now say that he was exceptionally fond going to the Zoo. The second period a little shorter in time, is more varied. The family moved to Kansas City; from there Disney, too young for service in the trenches went to the war with a Red Cross unit; fo Kansas City he returned and. tried to become a newspaper cartoonist. He found no job. He went to work as a commercial artist and saved up enough money to make his first animated cartoons.

There were animations of well known fairy tales and children’s classics. In competition with the highly developed product of the experts, they were crude and uninteresting, and they failed. Disney felt that if he wanted to make pictures, he would have to go where pictures were made and, in 1923, departed for Hollywood. His brother, who had come out of the war in shattered health, expected to live only a short time, and thought that California would be an agreeable place for his few remaining months of life. Walt had forty dollars when he arrived in Los Angeles Roy contributed about two hundred and fifty; they borrowed enough to make: a total of five hundred dollars and made their first picture. It was done in a bastard medium, using human beings and drawn figures simultaneously, ordinary movie photography and pen and ink; the inspiration comes from “‘Alice m Wonderland” and the series was called after the heroine which is interesting because – since the success of Mickey Mouse, Disney is continually receiving requests to make the original Alice in his own medium.

The first picture brought in fifteen hundred dollars; half of this was profit, if you figure that the brothers were not entitled to salary. During the making of the picture they had lived skimpily, on one full (cafeteria) meal a day, Roy ordering: the most filling vegetable, Walt the most filling meat, and then sharing, as they shared everything in those days, including their bank account. The lean time was soon over; the pictures were moderately successful, and after about four years, Disney went, in 1927 to Universal, where he created Oswald the Rabbit, the true forerunner of Mickey Mouse. Oswald was left behind when, in the middle of 1928, the Disneys, with fifteen thousand dollars saved, started out again on their own.

Sound was just coming in and Disney’s still-silent cartoons were unacceptable. Instantly he adapted his idea to the new medium. Unlike the producers of feature pictures he had nothing to scrap, no equipment to save, and hardly any public to worry about. He made a drawn comic and took it to New York for synchronisation, When he was finished he took it to the great producers and distributors — the men who had a few months earlier turned down the whole talking mechanism and were now furiously witnessing the success of the Vitaphone, Unanimously they informed Disney that no one would care for animated cartoons with sound. After several weeks, he found an independent backer, and on the nineteenth of September, 1928, the audience at the Colony Theatre in New York was “panicked” by “Steamboat Willie,” the first adventure of Mickey Mouse. A few days later Mickey was the hit at Roxy’s. Almost at once England all-hoiled him. The rest has been roses, roses all the way.

Roses and children. Leaving the distribution of the films to others, the Walt Disney Corporation concentrates commercially on the creation of movie audiences. Disney’s own connection with the vast enterprise which now enrolls three-quarters of a million children in Mickey Mouse clubs is not close. The clubs are the invention of an enterprising member of the business staff, and Disney’s only interest in them is as a source of knowledge; he learns from them what children like. The club members attend morning or early-afternoon performances at movie houses, led by a Chief Mickey Mouse and Chief Minnie Mouse; they have a club yell, and official greeting, a theme song, and a creed. As I find myself a little unsympathetic to this actiity, I sall limit myself to an exact quotation of the creed:

“I will be a square-shooter in my home, in school, on the playground, wherever I may be. I will be truthful and honorable and strive always to make myself a better and more useful little citizen. I will respect my elders and help the aged, the helpless, and children smaller than myself. In short, I will be a good American.”

For the good Americans there are commercial tie-ups with local businessmen, such as druggists who may feature a Mickey Mouse sundae, florists with Mickey Mouse bouquets, and so on; Parent-Teacher Associations are enlisted; the films at the matinees are swift-moving Westerns and other clean films, with a rather elaborate ritual of patriotism and good-fellowhip before and after.

It was reported that at the great Leipzig Trade Fair this year, forty percent of all the novelties offered were inspired by Mickey Mouse. One American company lists a velvet doll, a wood-jointed figure, a mechanical drummer, a metal sparkler, and half-a-dozen oter toys; there is a “Mickey Mouse Coloring Book” and another book of the adventures of Mickey Mouse; you can have Mickey Mouse on your writing paper; you can have him as a radiator cap. He appears in a comic strip in twenty-seven languages. From all of these exploitations, the originators receive royalties, since the own both the name and the design of the figure. (Infringements have been successfully prosecuted.) On the screen, Mickey Mouse appears in every country to which equipment for projecting sound films has penetrated. His name in Japan is Miki Kuchi.

Neither at homr nor abroad has Mickey’s career been without accidents. In Germany the appearance of an army of animals in Uhlan helmets was considered an affront, and the film was censored. In more dainty Ohio a cartoon was barred because a cow was discovered reading “Three Weeks.” Cows seem to have given more offence than any other beast in the Disney jungle, for many State Boards of Censorship protested against the grotesque and emotionally expressive udders which Nature and Disney gave them, and hereafter udders are to be at least partially concealed under a small provocative skirt. Disney himself is amused by the fuss; quite justifiably he takes it as a tribute to the remarkable reality of his totally unreal figure.

The process of creating this unreality begins in Disney’s mind. By this time it is only necessary for him to think of Mickey running to a fire, or Mickey skating; the rest is worked out in discussions with the artists and the gagmen. The automatic thing, the formula of the present, is the creative work of years ago, when Disney saw a series of pictures, saw moving forms across landscapes, rhythmic dances, compositions in black and white. These are still the essence of his pictures; his imagination is still largely visual. Only now that his assistants know the kind of picture he wants, his work has to he selecting the general idea, thinking out the tiny plot (even if it be only a modern version of “Little Red Riding Hood’* or a burlesque of some popular feature film), leaving the rest to experts.

I HAVE kept Mickey Mouse in the foreground because in general it is with Mickey that Disney is identified; but I belong to the heretical sect which considers the Silly Symphonies by far the greater of Disney’s products. Although there is a theme in each one, DISNEY’S IMAGINATION is freer to roam than it is in the more formal Mouse series. The Symphonies, moreover, are true sound pictures, without dialogue; the Mouse series has a tendency, lately, to run to verbal fun which is a little out of place.

Unlike the Mouse pictures, the Symphonies have no central character and no clearly defined plot. In them the animals and vegetation, purely incidental to Mickey Mouse, are brought into the foreground, and go through a wide range of activity — dances, skating contests, and so on — to the accompaniment of a reiterated musical theme.

The Symphonies reinforce what the Mouse tells us about Disney’s character: his delight in quick surprises, his uncomplicated sense of fun, his keen observation (Mickey Mouse has, correctly, four fingers, (not five). In addition they suggest his passion for all animals—he dropped his work and ran all over the vacant lot near his studio when he heard that a gopher snake had been seen there; he watched some sparrows for hours while they bent off a hawk and set up their nest. And he likes enormously the kind of laughter he himself creates; laughter at absurdities and impossibilities. Out of these natural, simple interests, backed by enormous files of pictures, cross-sections, and data on every animal extant, he creates the Silly Symphonies.

Like the first Mouse, the first Silly Symphony was long rejected by exhibitors; once shown, it ran six weeks at one house, an exceptional occurrence for a short subject. It was the Skeleton Dance, a theme naturally macabre, but treated with such humor and fantasy that no child has ever been frightened by it. Soon after followed a masterly series on the four seasons.

In one of these occurs a moment typical of Disney’s method. A frog dances on a log, its shadow following in the pool below. Presntly the frog moves to the opposite end of the picture, the shadow stays where it is, but continues to reflect the dance; then it joins its owner. Perhaps fifteen seconds cover the incident; it is a gracenote of wit over the broad humorous symphony of the whole picture.

With a picture to make every two weeks, both Disney and his associates have to use certain formulas, like the dancing of animals and chairs, chases and the sudden elongations of necks and legs. But the freshness of picture after picture proves that the creative force behind the formula is still powerful, and the combination of ingenuity and innocence (which was typical of prewar America) can still give pleasure. At the end of three and a half years, Disney’s ingenuity seems more fertile than ever. And his innocence is attested by the fact that he can think of nothing better to do with his time, his talent, and the five thousand a week (or thereabouts) which he earns, tan to put all of them back into the work he enjoys.

- Gilbert Seldes

Animation Artifacts &Articles on Animation &Disney 29 Jul 2009 07:47 am

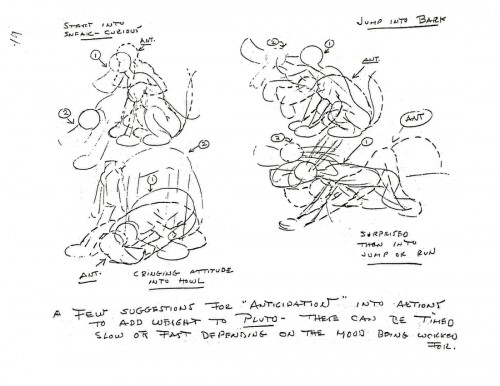

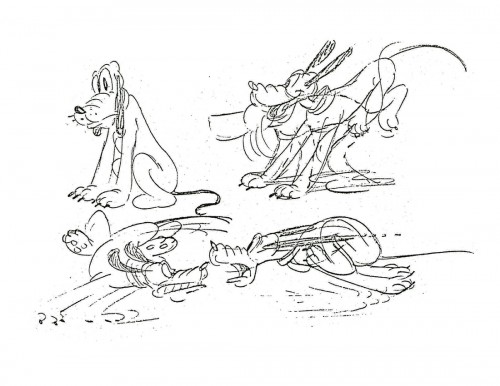

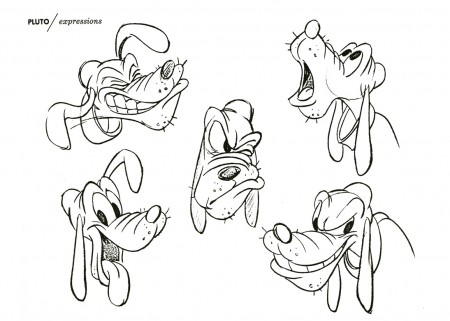

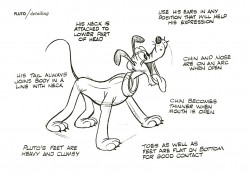

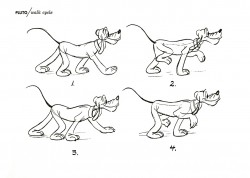

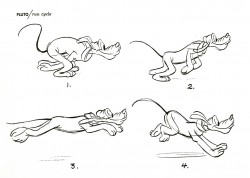

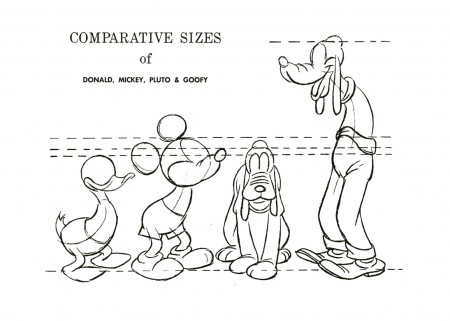

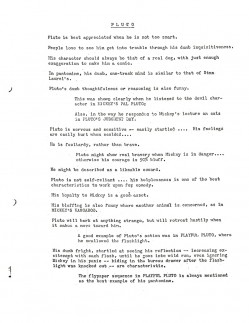

Pluto models

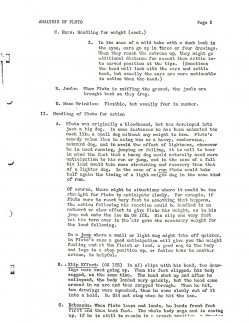

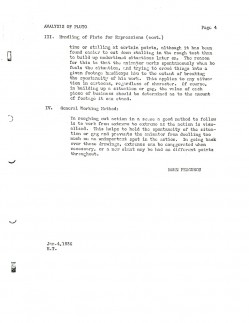

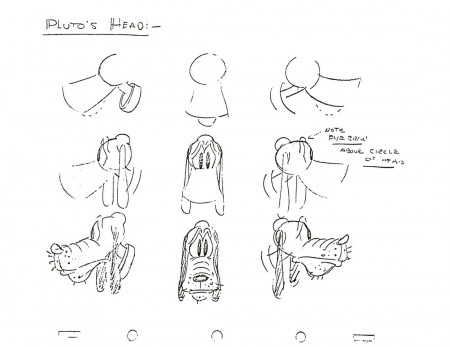

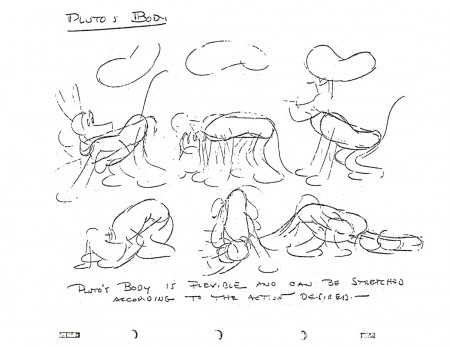

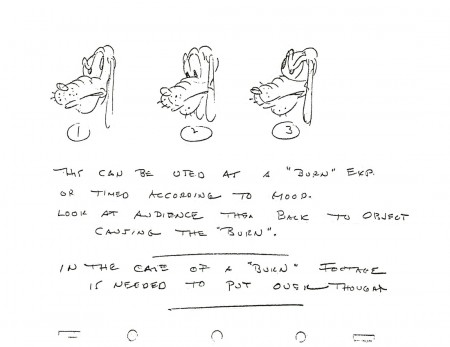

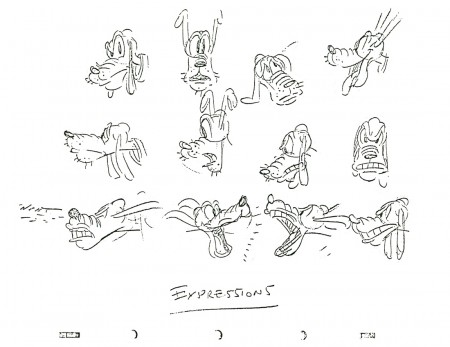

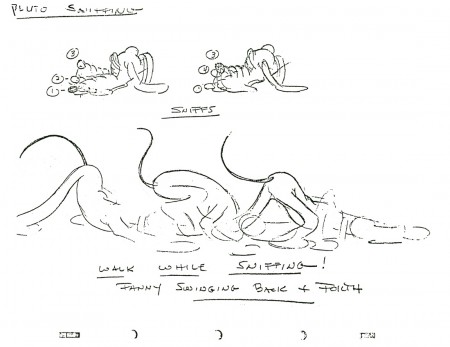

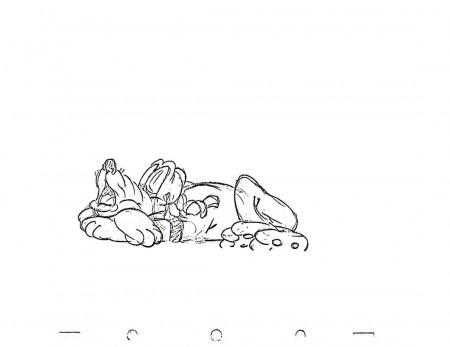

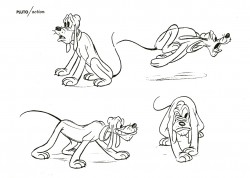

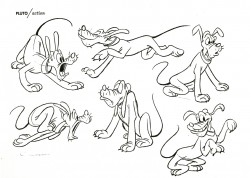

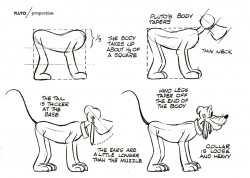

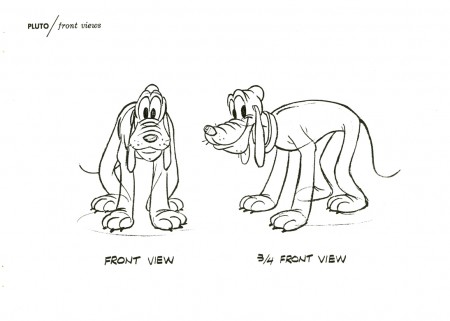

- When I posted the Goofy model notes I thought that I’d finished posting all that I had. Well I’ve just come up with this series of excellent lecture notes on drawing Pluto and his character. Ted Sears leads us to Norm Ferguson, who was the promary speaker for this lecture given to the Disney animation group back in 1936. They gave up drawing these characters so beautifully way back in the Thirties.

- When I posted the Goofy model notes I thought that I’d finished posting all that I had. Well I’ve just come up with this series of excellent lecture notes on drawing Pluto and his character. Ted Sears leads us to Norm Ferguson, who was the promary speaker for this lecture given to the Disney animation group back in 1936. They gave up drawing these characters so beautifully way back in the Thirties.

These finish off the character analysis lecture notes I have. You can find those for Mickey, Donald and Goofy elsewhere on this blog.

An edited form of these notes were published in Frank Thomas & Ollie Johnston‘s The Illusion of Life.

Here are the Pluto notes:

1

1  2

2(Click any image to enlarge.)

5

5

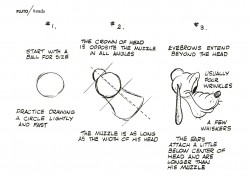

These drawings just never made it to the How to Draw Pluto

book that they sold at Disneyland in the Fifties.

Too much raw life and funny pictures.

All that’s left is for me to post the How to Draw Mickey and How to Draw Donald books from the Art Center at Disneyland. Next week.

Articles on Animation &Disney 28 Jul 2009 07:42 am

Old Black Magic

- Back in 1979, an eruption took place at the Disney studio. A group of the younger, talented artists at the studio – 20 of them – decided they couldn’t put up with it anymore and they walked out of the studio. Led by Don Bluth, they moved into his garage and a new studio came into being with competition for Disney’s troubled animation department.

- Back in 1979, an eruption took place at the Disney studio. A group of the younger, talented artists at the studio – 20 of them – decided they couldn’t put up with it anymore and they walked out of the studio. Led by Don Bluth, they moved into his garage and a new studio came into being with competition for Disney’s troubled animation department.

The rebellion didn’t just happen. Foment had started years earlier as Disney produced films such as The Black Cauldron, Pete’s Dragon and The Small One. Together with John Pomeroy and Gary Goldman, Bluth had put together an idea for a trial film, Banjo the Woodpile Cat, in 1975. The three got together after-hours and worked on their pilot film.

The article by John Culhane that appeared in the 1976 NYTimes really got this small group going. Disney was trying to put a little kick in their animation studio, and the kick ultimately resulted in a new animation studio – which, ironically, helped to get Disney back on track. It also got a couple of other studios going – Amblin and Ted Turner. They proved that there was money to be made in animation and slowly studios grew.

Here’s that NYTimes Magazine article:

1

1  2

2(Click any page to enlarge to a readable size.)

In April, I wrote about Bluth and Banjo in two parts:

Part 1

Part 2

Articles on Animation &Comic Art 23 Jul 2009 07:22 am

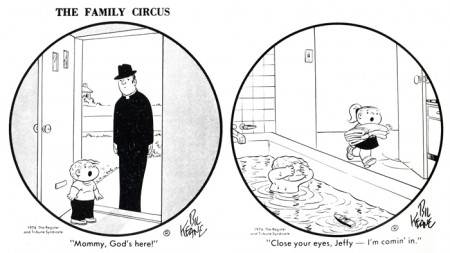

Keane Family Circus

- I’ve had a bizarre attraction to Bil Keane‘s comic strip, The Family Circus. I was always sure that this strip might make a good animated show for television. In fact, A Family Circus Christmas directed by Al Kouzel was a good show. It came as a surprise when I first saw it, though there’s no reason I should have been. The story was first rate. The real surprise came years later when I learned that Bil’s son, Glen, had become one of the finest of the new-generation animators at Disney.

- I’ve had a bizarre attraction to Bil Keane‘s comic strip, The Family Circus. I was always sure that this strip might make a good animated show for television. In fact, A Family Circus Christmas directed by Al Kouzel was a good show. It came as a surprise when I first saw it, though there’s no reason I should have been. The story was first rate. The real surprise came years later when I learned that Bil’s son, Glen, had become one of the finest of the new-generation animators at Disney.

Bil Keane was interviewed in the Dec. 1975 issue of CARTOONIST PROfiles by the magazine’s editor, Jud Hurd, and I post it here:

BIL KEANE is one of those fairly rare cartoonists who is just as funny on the speaking platform as he is onpaper in the two panels, THE FAMILY CIRCUS and CHANNEL CHUCKLES, he creates for THE REGISTER & TRIBUNE SYNDICATE. We heard another of Bil’s great talks again recent-ly, which prompted us to ask him some questions ahout cartooning for our magazine. BU and his famih- live in Paradise Valley, near Phoenix, Arizona.

BIL KEANE is one of those fairly rare cartoonists who is just as funny on the speaking platform as he is onpaper in the two panels, THE FAMILY CIRCUS and CHANNEL CHUCKLES, he creates for THE REGISTER & TRIBUNE SYNDICATE. We heard another of Bil’s great talks again recent-ly, which prompted us to ask him some questions ahout cartooning for our magazine. BU and his famih- live in Paradise Valley, near Phoenix, Arizona.

Q: Some time ago we did an interview with you that has caused a lot of comment. Your answers were hilariously funny, but not too informalive. l’d like this tobea serions interview that imparts to our readers the inner workings of Bil Keane.

KEANE: Fine. Which way to the X-ray machine?

Q: Seriously, could you give us a brief resumé of your art background?

KEANE: It’ll be quite brief because I never studied art. I taught myself to draw while I was in high school by imitating the cartoonists whose work I admired.

Q: Who were they?

KEANE: Each month I would have a different New Yorker magazine idol… George Price, Richard Decker, Peter Arno, Robert Day, Whitney Darrow, Barlow, Wortman… This was in the late thirties. l’d practice each style and technique until, in my mind, my drawings looked “similar” to the master. I still think this is an excellent way to develop a style. Eventually your own “thing” will emerge. I enjoyed studying cartoonists’ styles and learned to recognize them like handwriting. I used to play a game when Collier’s, The Saturday Evening Post, or American Magazine would arrive in the mail. As l’d turn a page on which there was a cartoon, l’d quickly cover the part of the cartoon bearing the signature and name the cartoonist who had made the drawing. Then, l’d lift my hand to see if I was right. I had a very high rate of accuracy. l’d be fooled only by a newcomer. I also became a fanatic cartoon clipper. I eut out every magazine cartoon I could find and pasted them in huge scrapbooks. I remember one time I was thrown out of a public library for slicing cartoons out of the current magazines with a razor blade. In fact, it was last week!

Q: Were magazine cartoons the only ones thaï interested you, or did you follow the newspaper cartoonists too?

KEANE: I never was an avid fan of the comic strip guys although I certainly admired most of the big ones. However, I had a real penchant for the newspaper panel cartoonists. George Lichty was my all-tirne favorite. I also liked H. T. Webster, Fontaine Fox, J. R. Williams, Gène Ahern and particularly Clare Briggs. Another genius to me was J. Norman Lynd who drew “Vignettes of Life.”

Q: Do you feel that most magazine gag cartoonists can develop a successful syndicated feature?

KEANE: Not necessarily. Some cartoonists are prolific and can turn out volumes of material from which a magazine editor may select the best. A syndicated cartoonist, for the most part, is his own editor. Unless he has the ability to discern which of his creations are good and which are poor, his feature will not hâve the batting average required to maintain success. I hâve seen highly successful magazine men fall fiât on their faces when attempting a 6 day a week feature done entirely by themselves.

Q: Some people write inspirations for cartoon ideas on the backs of old envelopes. Russell Myers carries a lape recorder and talks into it when he thinks of a “Broom Hilda” idea.

What system do you use for this?

KEANE: I don’t think of many “Broom Hilda” ideas, but when I do, I talk into the back of an old envelope.

Q: You promised this would he a serious interview.

KEANE: Frankly, for “Family Circus”, the only gimmick I use to think of ideas is thumbing through family type magazines where articles, pictures, ads, columns, etc., will suggest a setting or bring to mind one of the incidents that has happened in our home in the past. Given a specific setting or situation I can readily create a child’s reaction to it. I have a childish mind.

Q: Do you then write the caption or do the drawing first?

KEANE: It works both ways. Frequently the idea comes from a quote or phrase that is typical, or a youngster’s mispronounced word, or a childish musing such as: “Mommy, I need a hug.” Then all I do is create a cartoon that best fits with the line. At other times the picture depicts the identifiable scene such as a little girl dressed in her mother’s clothes, or a little boy running into the house with a bug in ajar, etc. Then I need to create a line to go with the illustration.

In most cases the caption is not really finalized till I am through with the drawing. As I am penciling the cartoon I keep saying the line over and over again to myself, changing it slightly to see how it sounds in various versions. I think it is terribly important in the kind of thing I do to have what a child says, or Mommy says, or whoever, sound natural, unmanufactured and clear.

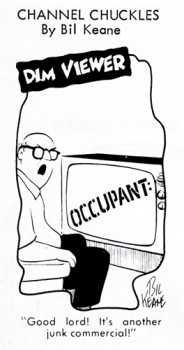

Q: In “Channel Chuckles” you use a different type of humor than you do in “Family Circus.” Would you comment on this?

KEANE: “Channel Chuckles” humor is more satirical, zany and topical than “Family Circus.” The latter utilizes the identifiable, typical, “our kids have done the same thing” type of humor. Another entirely different field of humor that I like is the pun. I developed a solid background in this type of humor as a young boy when I was an avid collector of the old College Humor magazines that had been published in the 20′s and 30′s where piuis ran rampant. When I worked for the Philadelphia Bulletin in the late 40′s and during the 50′s I developed a Sunday color feature called “Mirth-quakers” which featured illustrated puns and the old “he-she” jokes (Sample: “Many big men born in this town?” “Nope, only little babies!”). For a few years, I drew a feature for the Saturday Evening Post “Pun-Abridged Dictionary. When my Sunday “Family Circus” page started in 1′ appended it with a weekly panel “Sideshow”, consisting of reader-contributed puns. The 25,000 letters a year that this feature drew, as well as the enthusiastic response other pun features convinced me that thi many pun-lovers in the country. (And quite few in the city, too, but they won’t admit it.)

KEANE: “Channel Chuckles” humor is more satirical, zany and topical than “Family Circus.” The latter utilizes the identifiable, typical, “our kids have done the same thing” type of humor. Another entirely different field of humor that I like is the pun. I developed a solid background in this type of humor as a young boy when I was an avid collector of the old College Humor magazines that had been published in the 20′s and 30′s where piuis ran rampant. When I worked for the Philadelphia Bulletin in the late 40′s and during the 50′s I developed a Sunday color feature called “Mirth-quakers” which featured illustrated puns and the old “he-she” jokes (Sample: “Many big men born in this town?” “Nope, only little babies!”). For a few years, I drew a feature for the Saturday Evening Post “Pun-Abridged Dictionary. When my Sunday “Family Circus” page started in 1′ appended it with a weekly panel “Sideshow”, consisting of reader-contributed puns. The 25,000 letters a year that this feature drew, as well as the enthusiastic response other pun features convinced me that thi many pun-lovers in the country. (And quite few in the city, too, but they won’t admit it.)

Q: You mentioned having worked for the Philadelphia Bulletin. Is this where you started and would you fill us in on your career to date?

Q: You mentioned having worked for the Philadelphia Bulletin. Is this where you started and would you fill us in on your career to date?

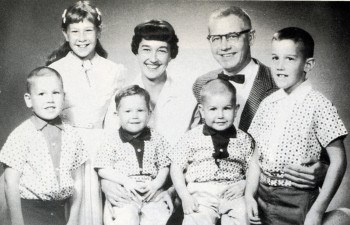

KEANE: My first job was or, Philadelphia Bulletin as a messenger in the year I graduated from high school. / years in the Army where I drew for Yank, Pacific Stars & Stripes, etc., I came back to the Bulletin with a fist full of my published service cartoons. This landed me a job in the news art department drawing spot cartoons and caricatures for the entertainment section which eventually led into my syndicate feature “Channel Chuckles” in 1954. I drew magazine cartoons for most of the markets, did a weekly Sunday comic for the Bulletin called “Silly Philly” (a little Quaker character based on William Penn), and edited a 16 page weekly supplement in the Sunday paper called “Fun Book”. When the income from “Channel Chuckles” and my free stuff enabled me to leave the 9 to 5 job at the Bulletin, my wife Thel (who I had met in Australia during the war and returned down under to marry in 1948) and I, along with our five small children moved to Paradise Valley, Arizona (near Phoenix) in 1959. Working at home for the first time with our little people underfoot, I discovered that most of the magazine cartoons I was selling had to do with family life and small children. I then decided to produce a second feature for the Register and Tribune Syndicate and introduced “Family Circus” in 1960.

Q: Wasn’t it originally called “Family CIRCLE”?

KEANE: Yes. I felt the name and circle format were a perfect combination. However, Family Circle Magazine (the one you read while waiting at the checkout counter in the supermarket) objected to the use of what they claimed to be their title and forced us to change the name of the feature. Frankly, I think if my syndicate had fought a small legal battle, we could have retained the CIRCLE title. The conversion was simple: I changed the last two letters from L-E to U-S. And, many feel that the CIRCUS title is more indicative of what goes on in the cartoon.

KEANE: Yes. I felt the name and circle format were a perfect combination. However, Family Circle Magazine (the one you read while waiting at the checkout counter in the supermarket) objected to the use of what they claimed to be their title and forced us to change the name of the feature. Frankly, I think if my syndicate had fought a small legal battle, we could have retained the CIRCLE title. The conversion was simple: I changed the last two letters from L-E to U-S. And, many feel that the CIRCUS title is more indicative of what goes on in the cartoon.

Q: Would you give us a rundown on your average working day?

KEANE: On most mornings I get up about 7:30, hit the studio (which overlooks the tennis court in case somebody wants to play) about 9, and work through most of the day with a break for lunch. It seems that the creative juices flow best late in the afternoon and will continue into the evening. I occasionally work after dinner till about 10 P.M. A comfortable couch in my studio is put to good use for 20 minute naps when 1 grow weary. Some mornings, especially in the summertime, I awaken about 4:30 A.M. and work till the morning Arizona sun is drenching Camelback Mountain with yellow. I then go back to bed (about 8 A. M.) for another hour of sleep. After breakfast I return to the studio to answer mail and to the more mechanical chores of drawing. It seems that the very early morning and early evening are the best times for uninhibited creative work. Of course, this work schedule varies around our social engagements and fairly frequent tennis matches. Totally, I average about 45 hours of real work each week and love every minute of it.

Q: An interviewer once asked you if “Family Circus” was based on your real life, and you replied that, on the contrary, your real life is based on the cartoon. If a particular situation gets a laugh in the feature, you try to work it into your home the following week. Bit, is that true?

KEANE: No, but it’s a bit more amusing than the truth. My ideas are really based on our own family experiences and so are the characters. Our children aren’t as young as they once were, but, then who is? I have an excellent memory for detail and can recall vividly incidents from years ago. In fact, 1 even base a lot of the moods and childish attitudes in my cartoon on my own experiences as a small boy.

KEANE: No, but it’s a bit more amusing than the truth. My ideas are really based on our own family experiences and so are the characters. Our children aren’t as young as they once were, but, then who is? I have an excellent memory for detail and can recall vividly incidents from years ago. In fact, 1 even base a lot of the moods and childish attitudes in my cartoon on my own experiences as a small boy.

Bil and Thel review cartoons to submit.

Q: What are the ages of your five children now?

KEANE: The oldest is 25 and the youngest is 17. Glen, our 21 year old, is presently working in the animation department at Disney Productions in California.

Q: Do you get many cartoon ideas from reader mail?

KEANE: Well, not cartoon ideas per se. A young mother will occasionally write and say “Here’s something that happened in our house — maybe you can use it.” The incident she relates will form the nucleus of a situation to which I then apply my own family experience and whatever expertise I have as a gag creator. The result is usually a scene that took place in thousands of homes that very week. Basically, children never change and family life is universal and timeless.

Q: What advice would you give a young cartoonist aspiring to do a feature?

KEANE: I would highly recommend an art background. It is quicker in the long run than learning by your own mistakes. Also, stick to a subject with which you are familiar. This is the only way you will maintain high quality material. Don’t be a phony. Do what comes naturally.

Q: Obviously, since you live in Arizona, it has not been necessary for you to be close to the New York market to achieve success. Would you comment on this? KEANE: Even when I lived in Philadelphia I sold my cartoons to the Saturday Evening Post entirely through the mail and their offices were very close to the Bulletin Building where I worked. One of the beautiful things about this cartoon business is that it allows you to live anywhere there is a mailbox.

Q: How is your new cartoon book on tennis doing?

KEANE: It has only been out for a few months now, and already it’s selling into the dozens. Truthfully, the book (DEUCE AND DONTS OF TENNIS) is doing phenomenally well. Tennis is a popular subject and the $2.95 price is low enough to make it a hot item.

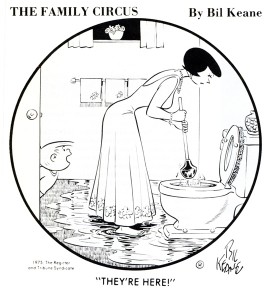

Q: What other books have you had published?

KEANE: Fawcett Gold Medal has published 12 paperback collections of my “Family Circus” cartoons. The newest, being released in October, is titled: “I CANT UNTIE MY SHOES!” The cover depicts Jeffy standing in a bathtub full of water. Several different publishing houses have put out books of my other cartoons. I collaborated with columnist Erma Bombeck on a book

KEANE: Fawcett Gold Medal has published 12 paperback collections of my “Family Circus” cartoons. The newest, being released in October, is titled: “I CANT UNTIE MY SHOES!” The cover depicts Jeffy standing in a bathtub full of water. Several different publishing houses have put out books of my other cartoons. I collaborated with columnist Erma Bombeck on a book

_________I believe that’s Glen to the far left._______________for Doubleday: “JUST WAIT TILL YOU HAVE CHILDREN OF YOUR OWN.” Erma is a neighbor and a genuinely funny lady.

Q: Not many cartoonists are funny on their feet as well as on paper. You have quite a reputation as a stand-up comedian delivering side-splitting talks at a microphone. Is this a natural talent or something you learned?

KEANE: It’s another thing I’ve taught myself through the years. I love to make people laugh and just eat up the immediate crowd reaction and applause, which is a pleasant change from drawing a cartoon and waiting weeks or months till after it is published for any reaction. When I give a talk, I write every word in advance. I plan the comments and one-liners carefully, making the material as topical and intimate as possible for that audience. In addition to concise, fresh material, the two important things for a stand-up comedian are delivery and timing. While giving speeches can be profitable, it is terribly time-consuming. I limit my personal appearances to only the ones I really want to do.

Q: Thanks, Bit. Do you have a final word?

KEANE: Yes — ZYZZOGETON. It’s on the last page of my dictionary. Before I close, Jud, I would like to say something nice about CARTOONIST PROfiles. I’d like to, but I can’t think of anything. Seriously, folks — your publication is an excellent chronicle of every phase of cartooning. We have all learned a lot about each other through your meticulous efforts. You deserve a big round of applause. (Jud gets a sitting ovation.) A hundred years from now people will be talking about Jud Hurd — which will give you an idea of how dull things are going to be in a hundred years.

Bill, Thel and Paradise Valley.

Articles on Animation &Commentary 22 Jul 2009 07:12 am

Recap – theories

I’d written this a couple of years ago and posted it then, but I thought I’d expand on it a bit.

I have my own, odd thoughts about animators – great, master animators – these are the only ones I’m talking about.

I think there are two types of animator. Both types, I think, are brilliant but I have my preference. Basically it’s the same breakdown I have with live action actors: the difference between Laurence Oliver and Marlon Brando. Both are geniuses, but I’d go out of my way to see one of them more than the other.

One works from the outside in, and the other works from the inside out. It’s Royal Academy vs. Stanislavsky.

Animators:

- One is a brilliant mechanic of an artist who gets every pose every gesture just right. The movement of the character is perfectly flawless, the accents are always in the right place, the timing is perfect, and the weight captured is exact.

The character is developed but usually in a manipulated, studiously planned way. Usually, this animation, to me, is cold. Give the character a fake nose, and Laurence Olivier could be playing it.

(Art Babbitt, at the top of the triangle, is to me the model for this type of animator.)

(Babbitt dwng of Mime from Hubley’s Everybody Rides the Carousel)

.

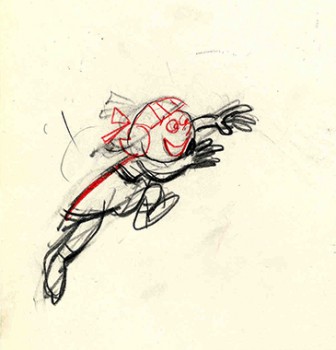

Then there is the emotional animator. The poses, gestures, actions of the character are emotionally executed by the animator as if this were the only way it could come out. The drawings are often violent and immediate – pencils ripping through paper and dark blotchy artwork.

This animator often puts emotion above mechanics, but (s)he digs to the depth of the part to find a real living thing. It isn’t always beautiful, but there’s a gem of a character on the screen. Like any living organism it’s unexpected and natural. Often this type animator works straight ahead (Does dwg#1 first, then #2,

This animator often puts emotion above mechanics, but (s)he digs to the depth of the part to find a real living thing. It isn’t always beautiful, but there’s a gem of a character on the screen. Like any living organism it’s unexpected and natural. Often this type animator works straight ahead (Does dwg#1 first, then #2,

(Grim Natwick, to me, is the prime example of this type.)

No, I’m not saying if you draw dirty, rough, violent drawings you’ll be a great animator. I’m speaking somewhat metaphorically – although the two examples I gave actually did draw that way. I’m sure Art Babbitt did one or two rough,

(Grim Natwick drawing from a Mountain Dew spot.)________violent drawings in his life, but

__________________________________________________his animation feels tight, controlled, yet beautiful. Grim also did one or two clean drawings in his time – I have one, as a matter of fact, but his animation is controlled by his feelings, accumulated knowledge of craft, and emotions. It all feels immediate, spur-of-the moment. It’s alive!

I’ve only ever watched animated films with this guide going in the back of my head. Mind you, also, I have enormous respect for both of these types; it’s just that I prefer the emotional type. More than wanting my characters to think, I want them to feel.

My temptation, here, is to give the obvious list of animators and where they fall in my model, but I think for now I won’t. CGI also fits into this mold, but it’s not a great picture. I’m curious to hear what others think of this model.

- I don’t mean for this post to turn into a “praise Grim Natwick” nor a “put down Art Babbitt” statement. I hope it doesn’t read that way.

- I don’t mean for this post to turn into a “praise Grim Natwick” nor a “put down Art Babbitt” statement. I hope it doesn’t read that way.

As I’ve said in the past, I treasure the drawings I have that were done by Art. I study and love every frame of any piece he’s ever animated. I just have more fun, personally – and I underline that word, personally, reviewing Grim’s animation.

Marlon Brando wasn’t a better actor than Laurence Olivier. They just came at it from different angles, and my preference has always been the more natural side of the acting world.

Back in the late thirties when the Group Theater was formed, these actors went to Russia to search out Stanislavsky, an acting teacher who preached at the bible of natural movement – getting in touch with your inner soul to project through the acting.

Back in the late thirties when the Group Theater was formed, these actors went to Russia to search out Stanislavsky, an acting teacher who preached at the bible of natural movement – getting in touch with your inner soul to project through the acting.

On Broadway, recently, was a revival of Awake and Sing. Clifford Odets was a member of the original Group Theater, and his plays reflected their “common man” attitude to theatrical productions. They weren’t trying to do spectacles or Royalty plays, they were trying to project the “average Joe” back from the stage. It changed theater, created Arthur Miller and a whole breed of acting styles. Compare, ex-Group Theater performer, John Garfield’s performances of the thirties with someone who was praised to the hilt back then, Paul Muni. Completely different acting styles – one natural and one overemotional and unrealistic.

The same was and is true of animators’ performances.

At Disney’s, these guys took their animation seriously. Some, such as Fred Moore and Norm Ferguson, thought they had it right and continued their own paths. Some looked into Stanislavsky and rejected it; others adopted it wholeheartedly. Still others, such as Grim Natwick, did it naturally and always had. Just as in the theater.

At Disney’s, these guys took their animation seriously. Some, such as Fred Moore and Norm Ferguson, thought they had it right and continued their own paths. Some looked into Stanislavsky and rejected it; others adopted it wholeheartedly. Still others, such as Grim Natwick, did it naturally and always had. Just as in the theater.

Next time you look at Fantasia, try just watching the acting styles. There’s nothing more Stanislavsky than Bill Tytla‘s scenes in Night On Bald Mountain, and there’s nothing less Stanislavsky than most of the animation in the Pastoral sequence.

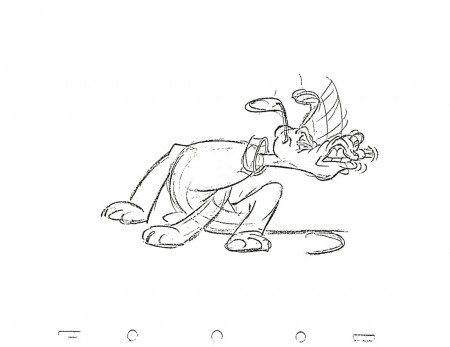

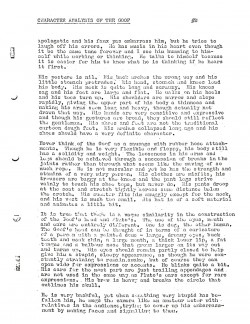

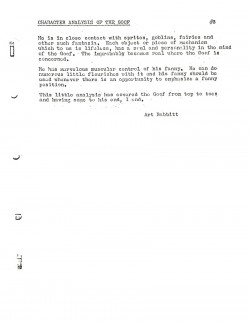

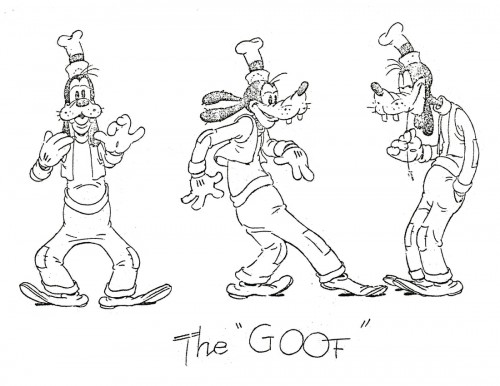

Articles on Animation &Books &Disney &Models 20 Jul 2009 07:21 am

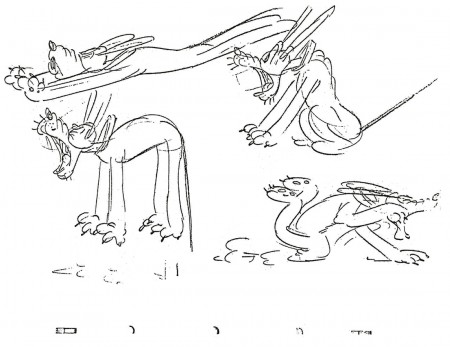

Goofy/Pluto models

- I’ve recently posted some discussions about Mickey and Donald which were part of the extrawork courses that the Disney studio held in the Thirties. Go here to see Mickey, go here to see Donald.

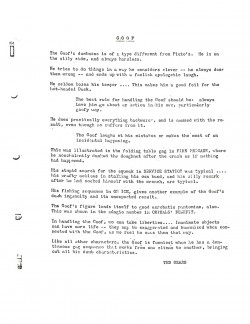

Here’s the section on the “Goof” which also includes a couple of Pluto models.

Art Babbitt is the lecturer.

1

1  2

2(Click any image to enlarge.)

Since there were so few pages to the above document, I thought I’d add the pages of the How to Draw Pluto book which was part of the Disney Animation Kit you once could buy from the Art Corner at Disneyland. It included books on How to Draw Mickey, Donald, Goofy and Pluto as well as a book on Tips in Animation.

Here’s Pluto:

1

1  2

2