Category ArchiveArticles on Animation

Animation &Animation Artifacts &Articles on Animation &Disney &Illustration &Models &repeated posts 29 Jun 2013 03:51 am

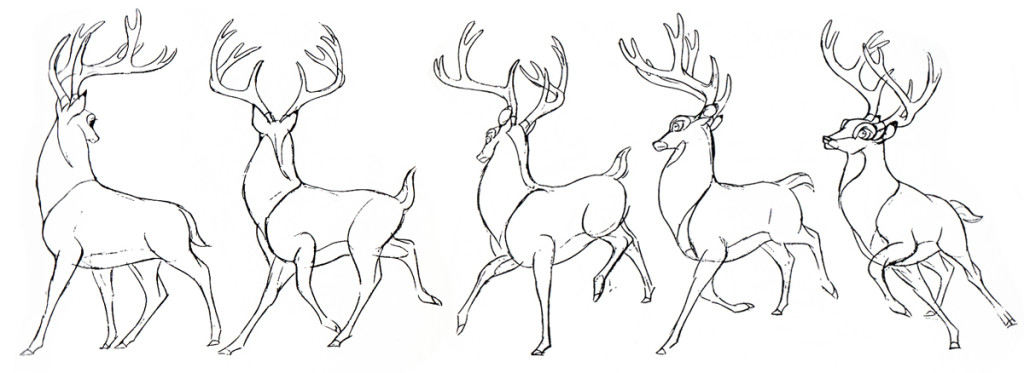

Young Bambi – repost

- It all starts with a drawing.

The brilliant host of cartoonists that came before us were an amazing group. To think of the complicated set of characters that the created. Characters with complex personalities and sophisticated drawing techniques.

Those characters went trough the mill in my own life time. Seeing the horrendous things that have happened not only to Mickey, Donald and Goofy but to Bugs, and Daffy and other Warner’s Bros characters. It’s been shameful.

I was going to post illustrations of some of those bastardizations, but I think it’s enough just to mention some of them.

Think of the Mickey Mouse Clubhouse running now on the Disney Channel. If ever there was proof positive that cgi weren’t cartooning, that would be it. Those are very unsophisticated digital puppetry shows where every move is obvious and preplanned, the voices are hideous, and the stories nowhere sophisticated enough to call trite.

Take a quick jump from those to the flash animated whirls that are being released with a lot of fanfare, and you’ll see what can go wrong with animation of stars. They may as well have dug Marilyn Monroe and Clark Gable out of the ground to allow the computers to move them as well. Like all new animation that’s being called good, these beasts-of-films are moved at the speed of light where no move gets to have any personality. Think of that naked Mickey in the most recent release. A thin slime of a creature, all black, that looks like a clam being animated by a Jim Tyer. There isn’t a pose in the film that could compare with what Terrytoons did – Terrytoons, the bottom of the barrel. They had personality all over these poorly drawn efforts.

There were the old Greg Ford versions of the WB characters for theatrical release, compilations of old with new. They were all mediocre but had the honor of the past directors in mind. The Bakshi Mighty Mouse cartoons were a take on their group of characters, but you had someone with a personality, Bakshi, trying to do wonders with a library of “B” stars. Even with the TV budgets, they were trying hard to do something, and often they were successful.

Today it’s all for poor exploitation, and no one is trying to do wonders with their characters. It’s all too sad.

The WB characters have had even greater attempts at poor art. You don’t have to think back too far to remember the sitcom version of the characters now running on Cartoon Network, also done in Flash. Think back to the poorly designed wretches that WB issued to their local network of stations, the WB. Those poor animated creatures were redesigned versions with scales and all. It’s just about time to scream, “Enough!” Is there not one executive who can offer some honor to these golden characters of our past? How much do we have to watch?

Why did these studios create their archives? Was it just to resell the goodies or was anything preserved so that the future animators could do right by these characters?

- It all starts with a drawing.

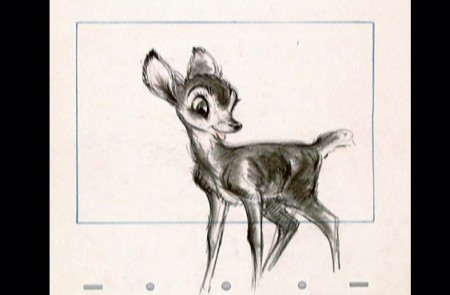

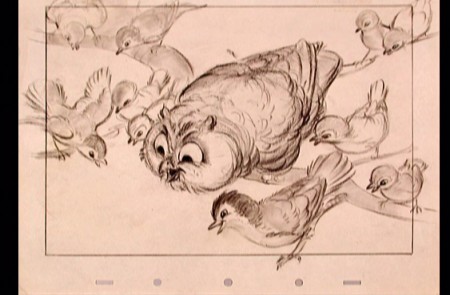

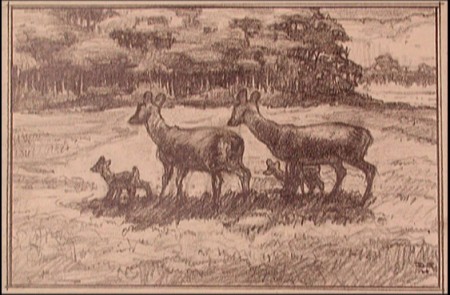

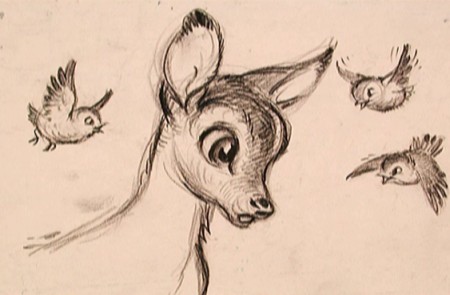

That’s all I can think. With that I’m just going to post a number of gems from Bambi. These had to have had some purpose greater than feeding Bambi !!. Or maybe I’m wrong.

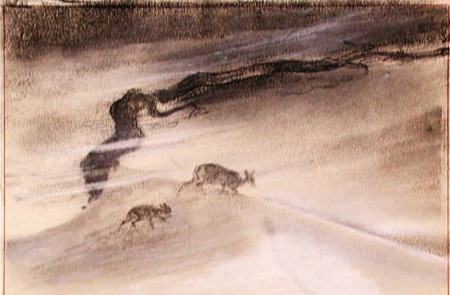

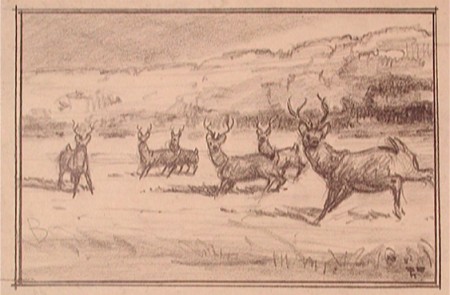

Bambi is, to me, one of the most beautiful of animated features. Collectively, the artists at the Disney studio pulled together to create some wonderful artwork which produced a wonderful film.

The initial work went through many phases, as would be a natural state for animation. However, all of the artists seem to be trying for a higher plane, and oftentime they reached it.

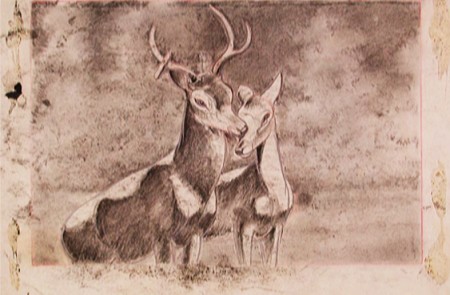

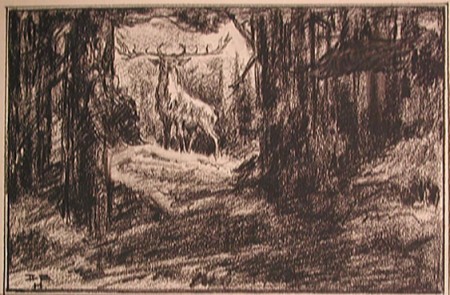

To celebrate the latest release of this film, the Blu-Ray/DVD version, I’ve pulled a lot of the drawings from the film and post them here. It’s amazing how much influence Marc Davis had early on. I can only ID the artists of some of the sketches. If you know, let me know. We have to continue to ID these artists. Without their names we just have these flash animatedMickes that don’t even include one credit. And maybe they shouldn’t be credited; the work is so embarrassing.

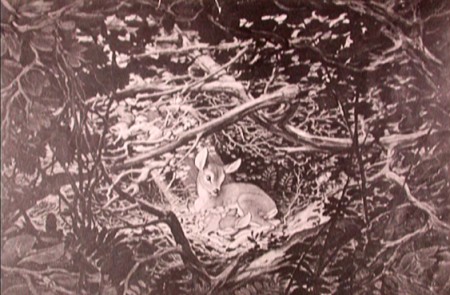

1

1David Hall

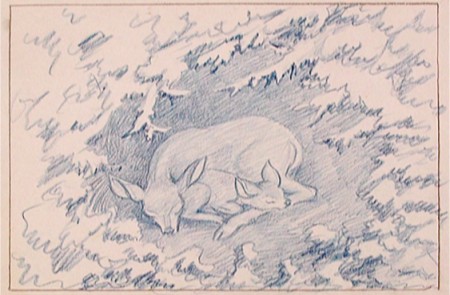

3

3

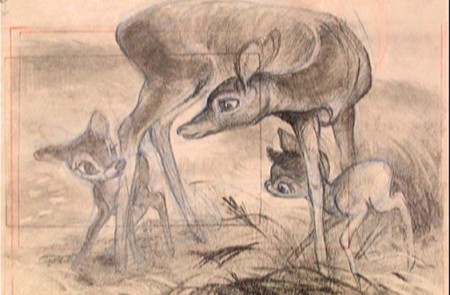

(above and below) Marc Davis

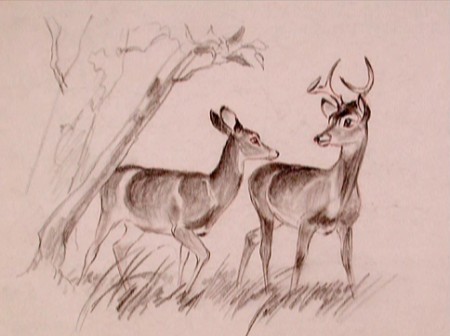

7

7

(above and below) Ken Peterson

Animation &Animation Artifacts &Articles on Animation &Commentary &commercial animation &Independent Animation &Layout & Design 22 Jun 2013 05:13 am

John Wilson 1920 – 2013

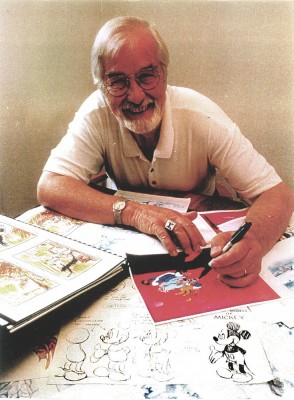

A number of years ago I’d made a short trip to LA. During that visit, a man came up to introduce himself. It was John Wilson. He told me that he had just nominated me for an ASIFA Hollywood Award because he’d loved my work. I’d learned so much from watching Mr. Wilson’s films that it was wonderful to see that the mutual admiration society ran both ways.

John Wilson died yesterday. His son, Andrew, wrote to tell me of it. My feelings go out to the family and am enormously sorry that animation loses another one of its masters.

He was a director, designer and animator about whom I’d done a series of posts on his career. Out of respect for Mr. Wilson, I’d like to post all of those articles together (and hold them there for the entire weekend.)

Hope you’ll enjoy.

1.

Let me start by sharing some bio information about John Wilson and his company Fine Arts Films.

- John Wilson was born in Wimbledon in 1920. He attended the Royal College of Art and was working by age 18 as a commercial artist with Willings Press Service. In WWII he served with the London Rifle Brigade in African where he was seriously wounded. Recuperating in hospital, he drew many cartoons of which several were printed. Eventually he would recover and get work at Pinewood Studios in the art department where he worked on GREAT EXPECTATIONS and THE THIEF OF BAGHDAD, among other films.

- John Wilson was born in Wimbledon in 1920. He attended the Royal College of Art and was working by age 18 as a commercial artist with Willings Press Service. In WWII he served with the London Rifle Brigade in African where he was seriously wounded. Recuperating in hospital, he drew many cartoons of which several were printed. Eventually he would recover and get work at Pinewood Studios in the art department where he worked on GREAT EXPECTATIONS and THE THIEF OF BAGHDAD, among other films.- By the time he was 25, he was working in animation at Gaumont-British Animation, a newly formed division of J. Arthur Rank’s studio, working under the direction of David Hand on the “Animaland” series starring “Ginger Nut.”

- In 1950 he moved to the United States working in layout and animation at UPA. He found himself working with Bobe Cannon, Pete Burness, Jules Engel, and Paul Julian. Eventually he left for the Disney studio working in Les Clark’s ‘Tinkerbell’ unit on PETER PAN and with Ward Kimball on TOOT WHISTLE PLUNK & BOOM.

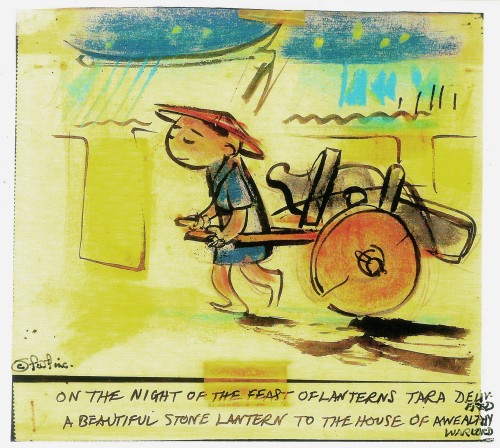

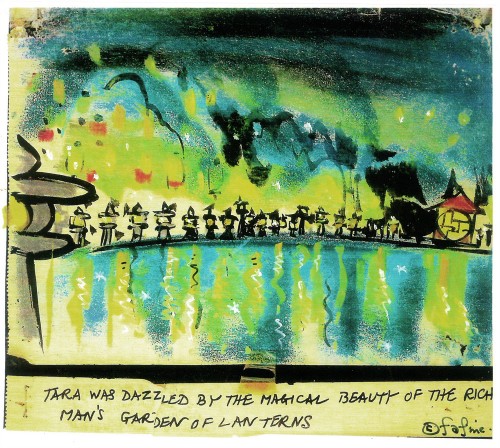

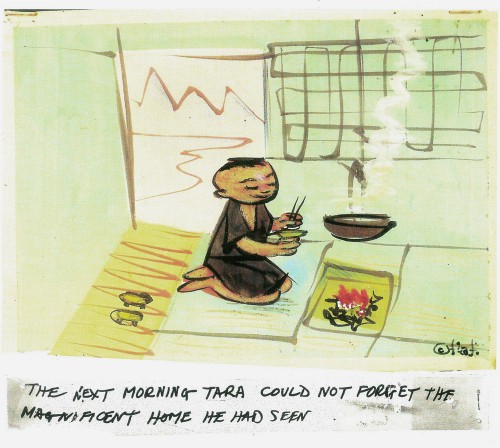

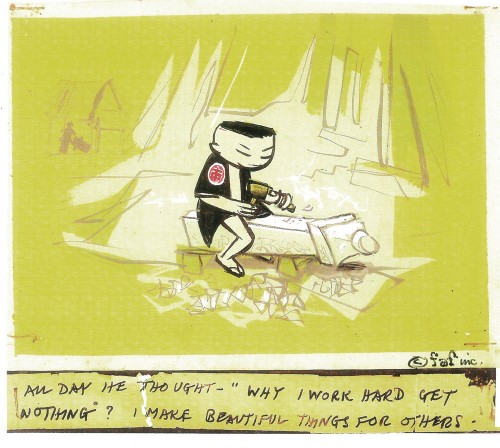

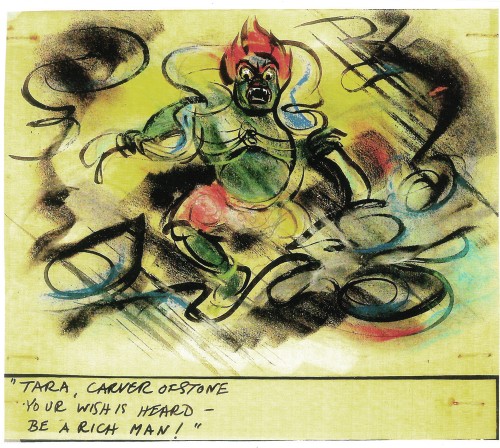

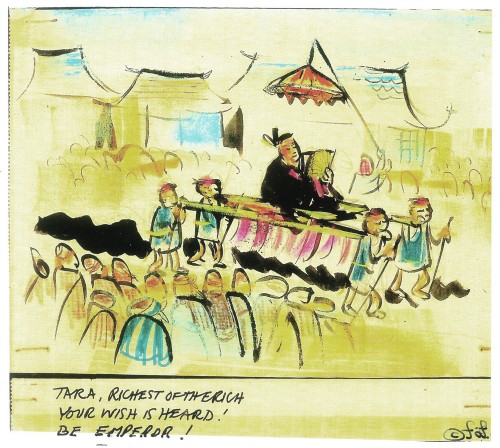

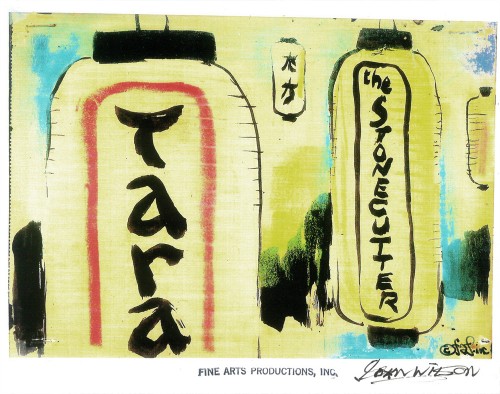

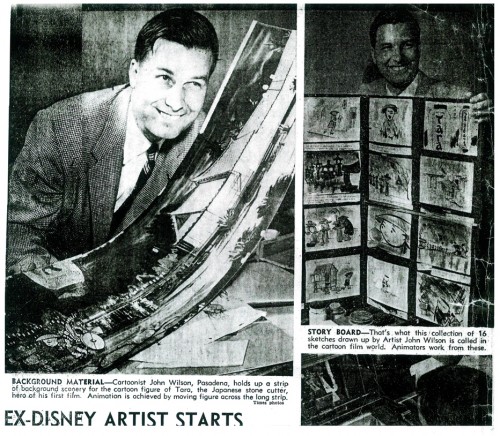

- He tried to sell Disney on the film Tara, the Stonecutter, but they weren’t interested. He completed it himself in 1955 using a Japanese style to tell the story. Wilson was impressed with the UPA style of modern art in animation, and that’s the route he took for his personal film. Thus his studio was born, called Fine Arts Films, in 1955. Tara had some success playing theatrically with the successful Japanese feature film, GATE OF HELL by Kinugasa (which had won the Oscar for Best Foreign Film.)

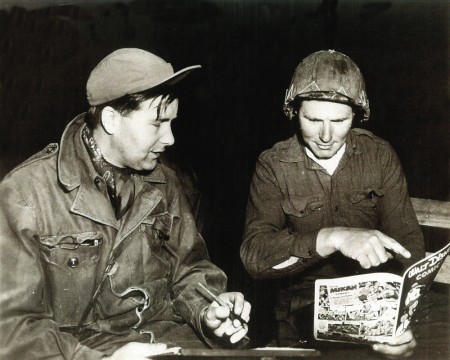

Wilson in Korea with the Bob Hope Tour to entertain the troops.

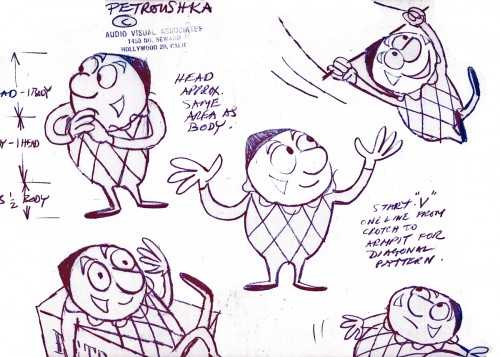

- This film led to his producing a verion of Stravinsky’s Petroushka for NBC which aired in 1956 as part of The Sol Hurok Music Hour. Notably, Stravinsky, himself, arranged and conducted the shortened version of the score suing the LA Philharmonic Orchestra. The film was designed by John Wilson and Dean Spille with anmation by Bill Littlejohn, Art Davis, and Phil Monroe. Chris Jenkyns, Dean Spille and Ed DeMattia designed the 16 minute show from Wilson’s storyboard.

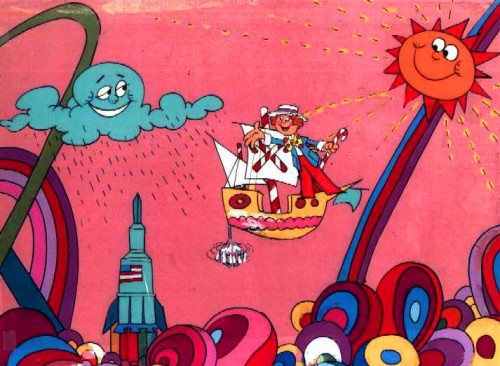

- Fine Arts Films had produced ‘Journey to the Stars’, a project for the 1961 World’s Fair, an animated voyage through space for NASA, which was seen in 70 mm Cinerama by ten million visitors to Seattle.

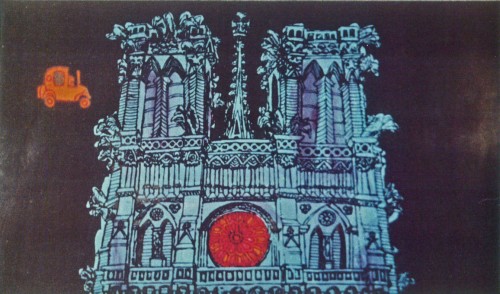

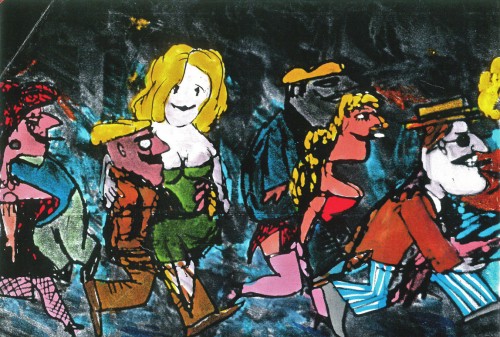

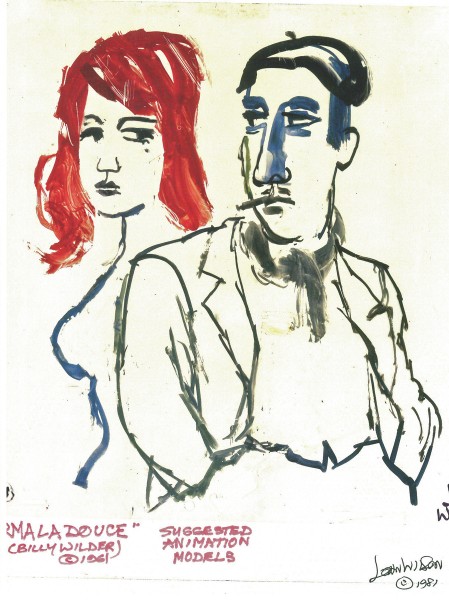

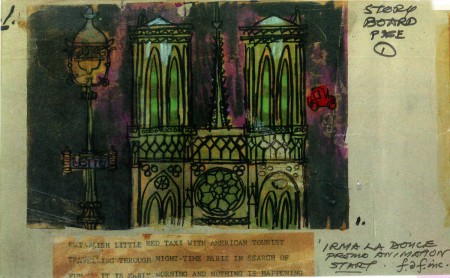

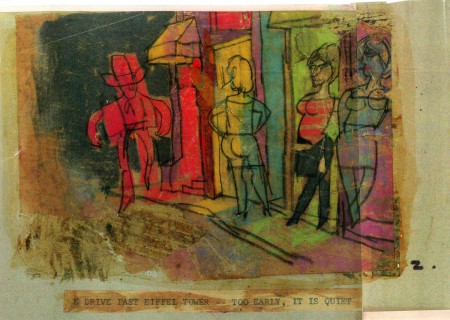

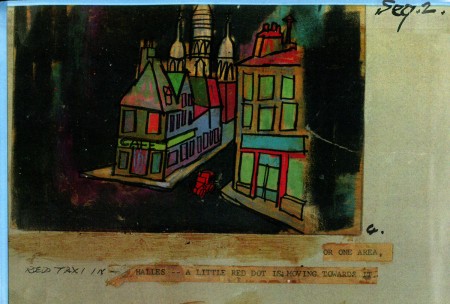

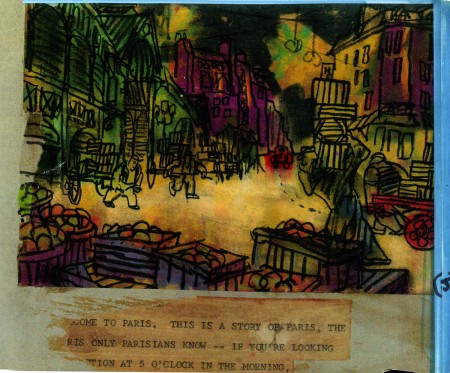

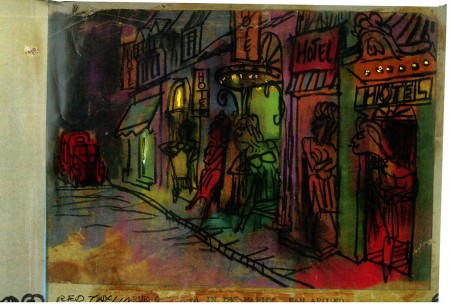

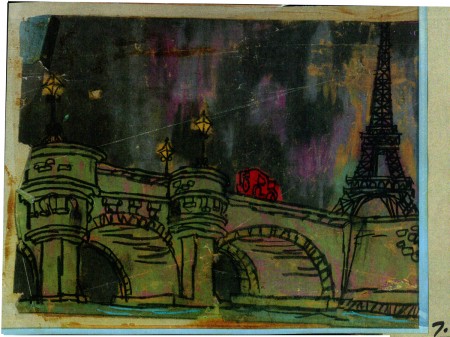

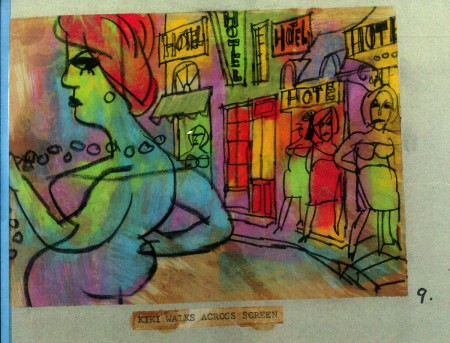

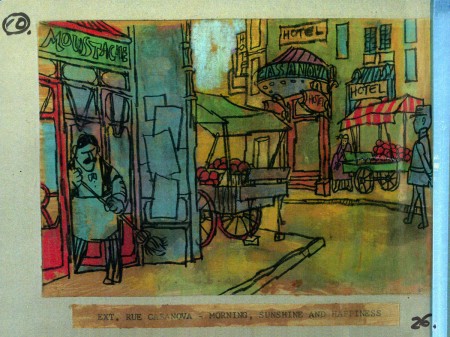

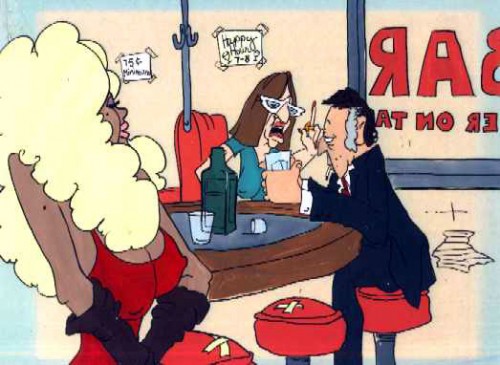

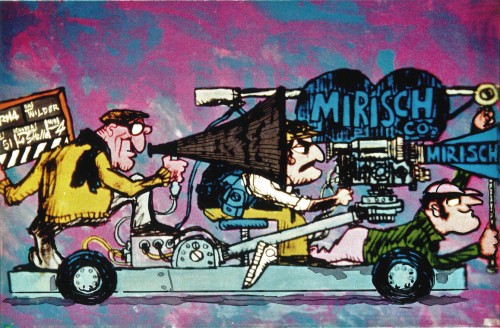

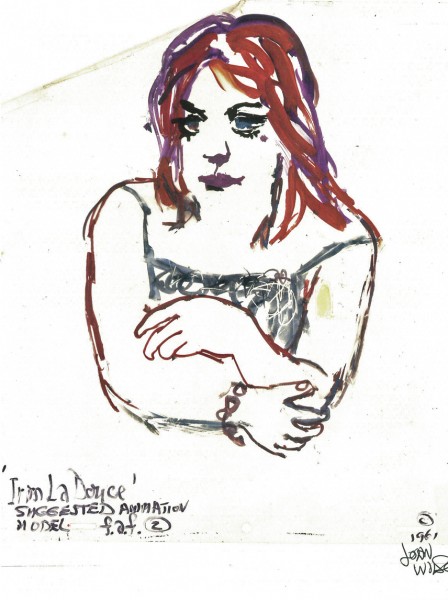

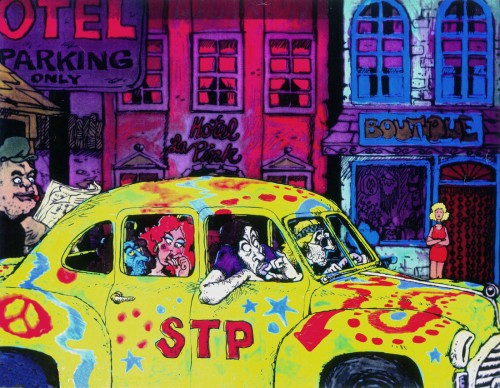

- Billy Wilder employed Wilson to do the titles for Irma La Douce after which they did a six-minute trailer for this Jack Lemmon, Shirley McLaine feature. It was all about Parisian prostitutes romping about in Montmartre, and animation could apparently make it acceptable. Artists Ron Maidenberg, Sam Weiss, Sam Cornell and Bob Curtis caught the vivid nightlife of Paris in a sexually charged animated short. It was a huge success in promoting the feature.

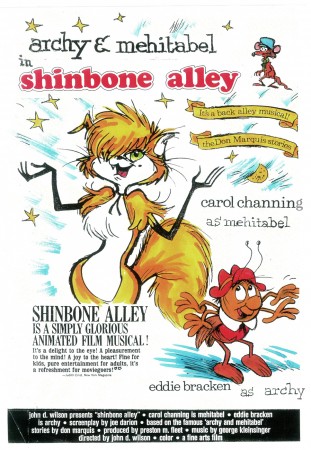

- In 1970 Wilson flew to Chicago to see Carol Channing and Eddie Bracken appearing in “archy and mehitabel in Shinbone Alleyâ€. On the basis of this theatrical musical, Wilson bought the screen rights to the book “archy and mehitabel” by George Herriman and began work on an animated feature which was released by Allied Artists in 1971.

- Fine Arts Films was also responsible for many animated commercials as well as weekly music video segments for the weekly CBS-TV series “The Sonny and Cher Show.†The songs included Joni Mitchell’s “Big Yellow Taxi†and Jim Croce’s “Leroy Brown.â€

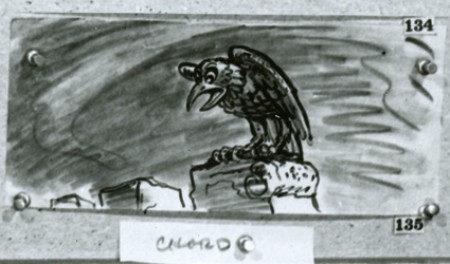

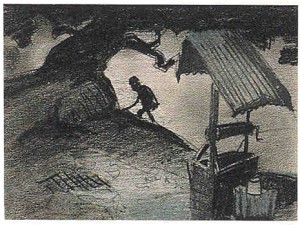

Here are some storyboard sketches by John Wilson for his initial short film, Tara, the Stonecutter. This film started it all for Wilson.

1

1

I haven’t seen the finished film, but I understand that Japanese decorative papers were used in the backgrounds and costumes of the characters.

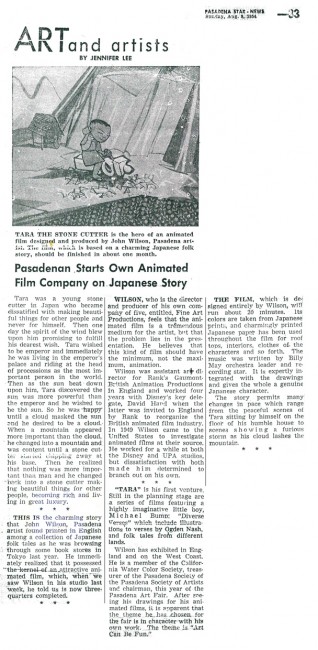

Here are two press clippings for this film from California papers.

(Click any image to enlarge.)

2.

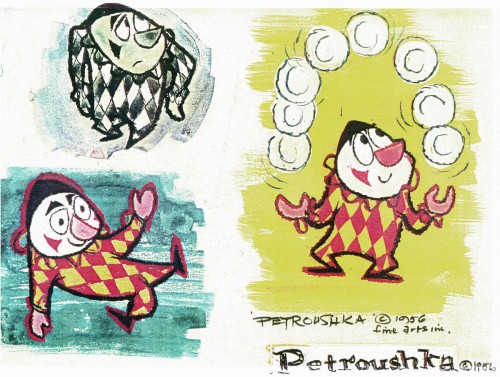

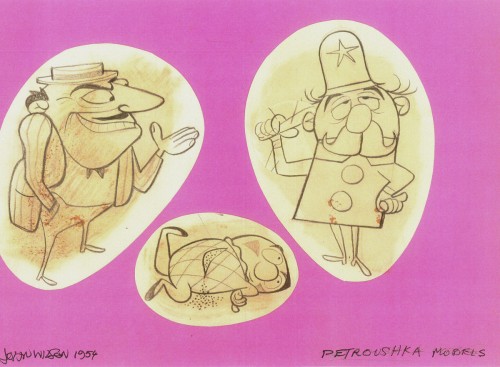

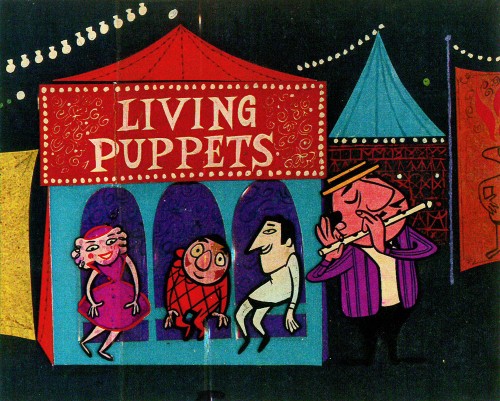

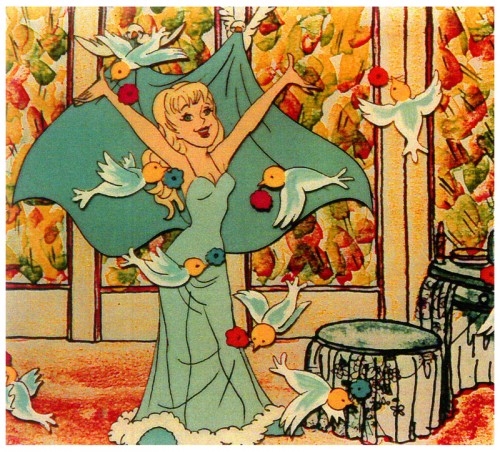

- After completing the film, Tara the Stone Cutter in 1955, John Wilson and his newly formed company,Fine Arts Films, was able to sell the idea of an animated version of Stravinsky’s Petroushka to NBC. They aired the 16 min. film in 1956 as part of The Sol Hurok Music Hour. Stravinsky, himself, arranged and conducted the shortened version of the score using the LA Philharmonic Orchestra.

The film was designed by John Wilson and Dean Spille; animation was done by Bill Littlejohn, Art Davis, and Phil Monroe. Chris Jenkyns, Dean Spille and Ed DeMattia designed the show from Wilson’s storyboard. This is considered the first animated Special ever to air on TV.

Here are some stills from that film and its artwork.

1

1Petroushka – model 1

11

11

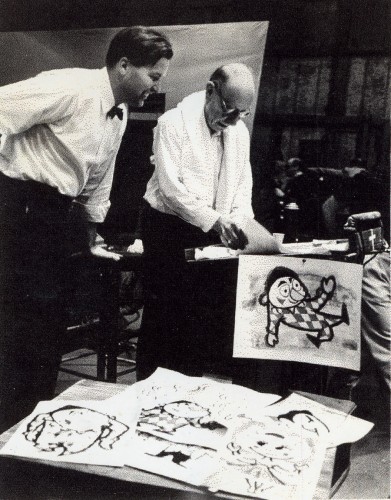

John Wilson and Igor Stravinsky preparing for recording of Petroushka

with the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra (1955).

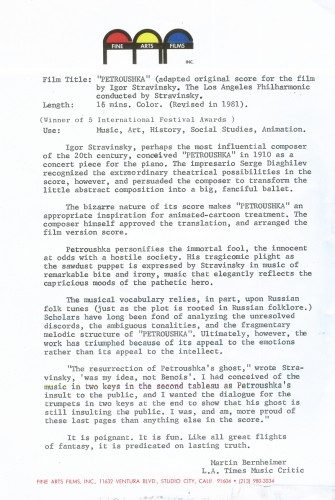

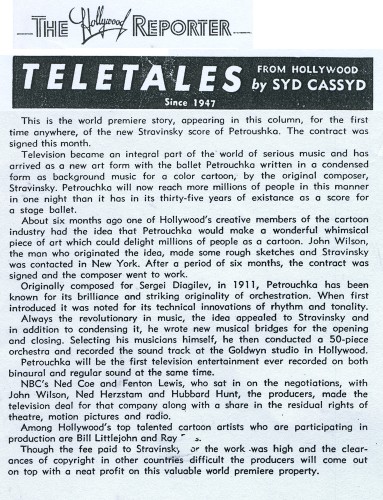

Here are copies of two reviews:

Los Angeles Time review (1956)

Hollywood Reporter review )1956)

(Click any image to enlarge.)

Petroushka was released on VHS tape combined with a number of the song pieces he did for the Sonny and Cher program. This tape, John Wilson’s Fantastic All Electric Music Movie, can still be found on Amazon but is pricey.

Thanks to Amid Amidi for the loan of this material.

3.

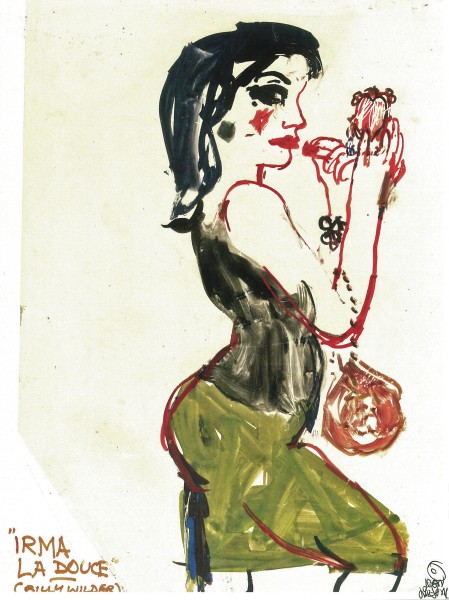

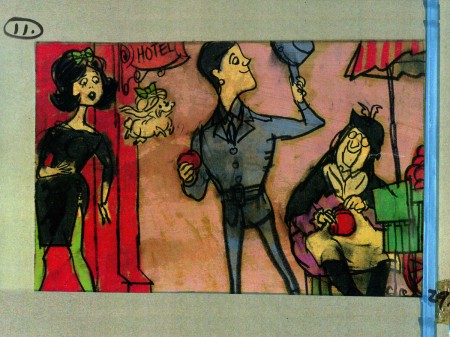

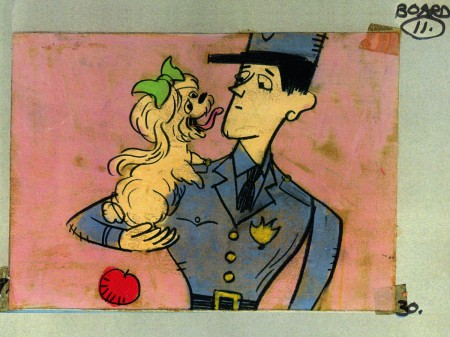

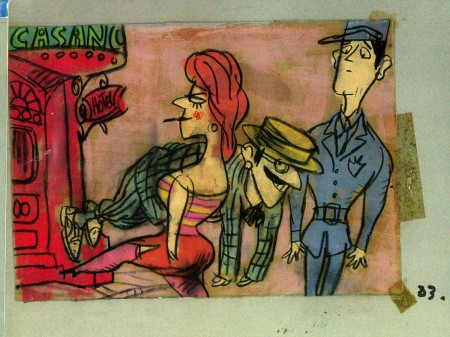

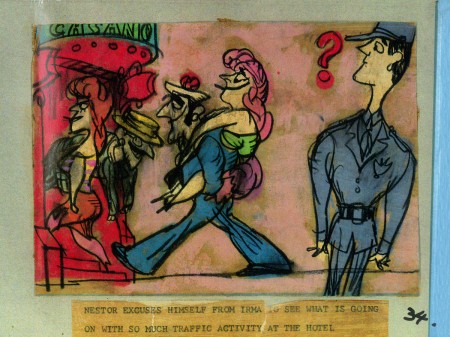

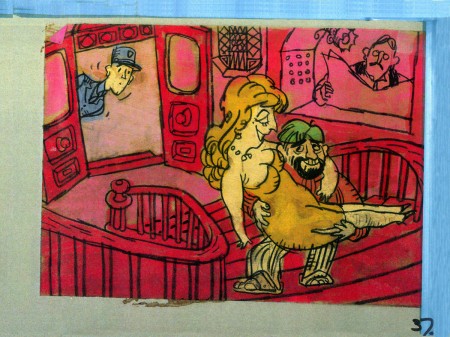

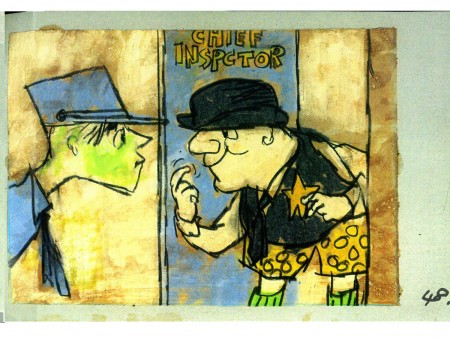

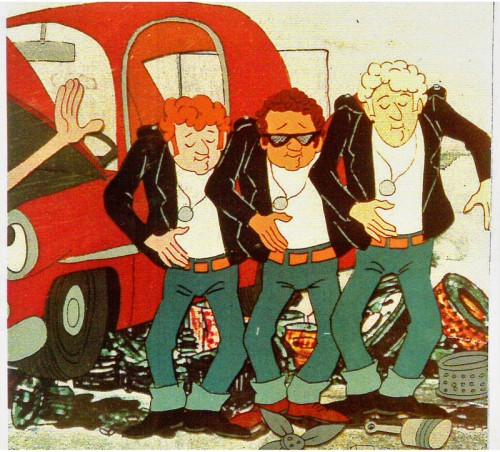

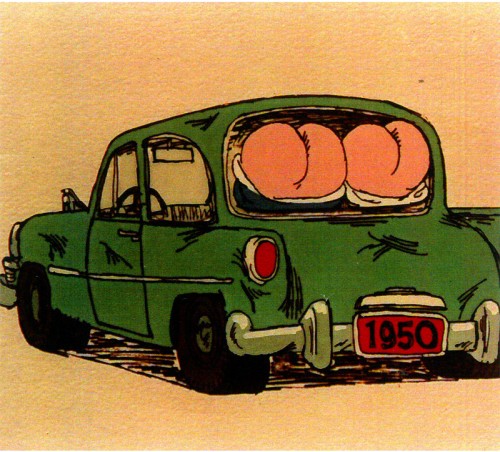

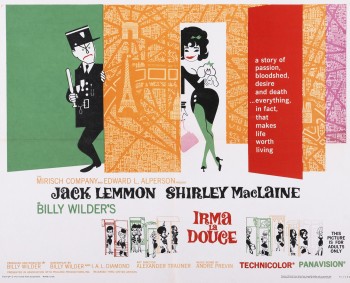

Irma La Douce was a racy film written and directed by Billy Wilder that starred Shirley MacLaine as a Parisian prostitute and Jack Lemmon as a French policeman who falls in love with Irma (Shirley MacLaine.) The film, for its time was daring, and came up with (heaven forbid) a “C” for Condemned rating from the Catholic church. This made it off limits for anyone under the age of 18. I was determined to go see the film, so I ignored the ban and went by myself. Naturally enough, no one tried to stop me. I wasn’t jaded by the movie anymore than I had been disturbed by the violence in all the Warner Bros. cartoons I’d seen. Looking back on Irma La Douce, it really is an innocent film, hardly risqué in any way shape or form.

Irma La Douce was a racy film written and directed by Billy Wilder that starred Shirley MacLaine as a Parisian prostitute and Jack Lemmon as a French policeman who falls in love with Irma (Shirley MacLaine.) The film, for its time was daring, and came up with (heaven forbid) a “C” for Condemned rating from the Catholic church. This made it off limits for anyone under the age of 18. I was determined to go see the film, so I ignored the ban and went by myself. Naturally enough, no one tried to stop me. I wasn’t jaded by the movie anymore than I had been disturbed by the violence in all the Warner Bros. cartoons I’d seen. Looking back on Irma La Douce, it really is an innocent film, hardly risqué in any way shape or form.

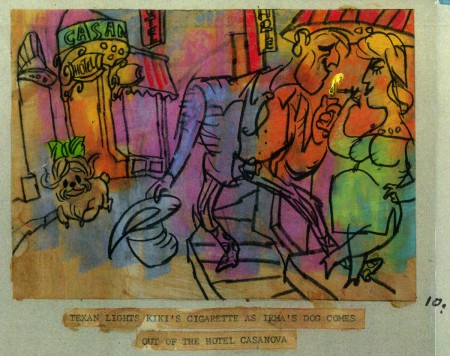

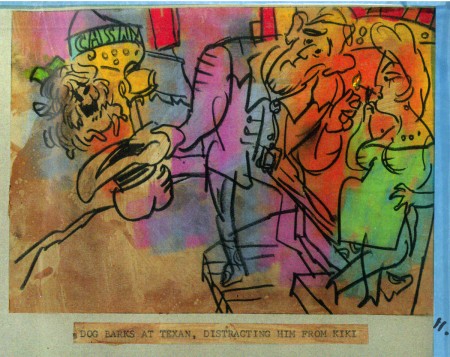

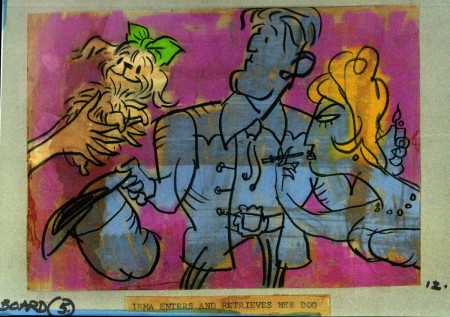

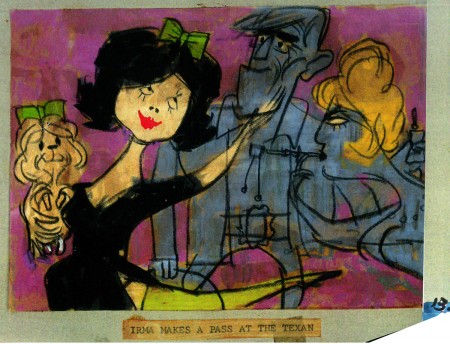

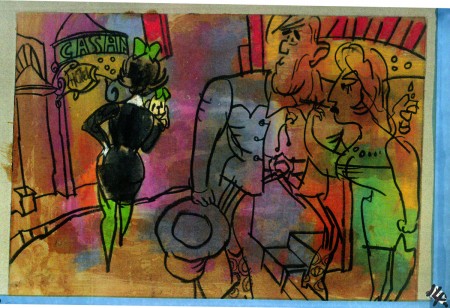

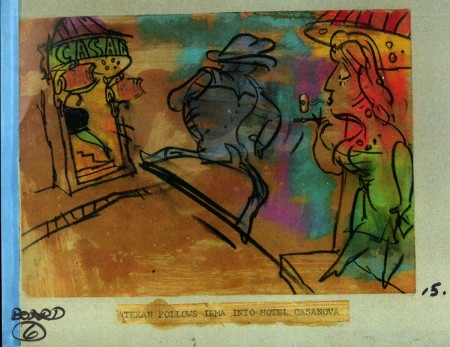

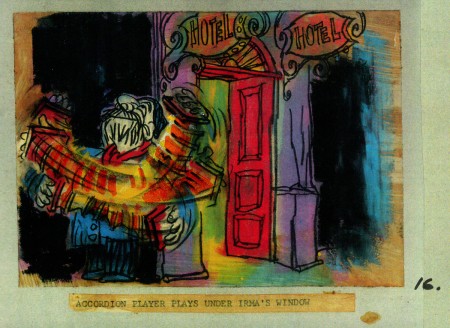

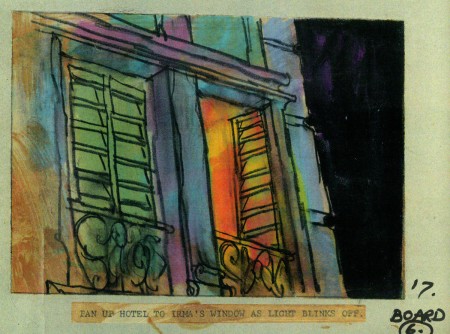

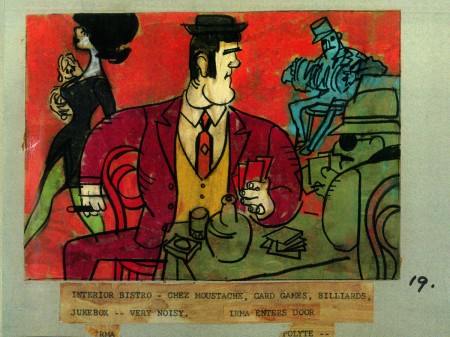

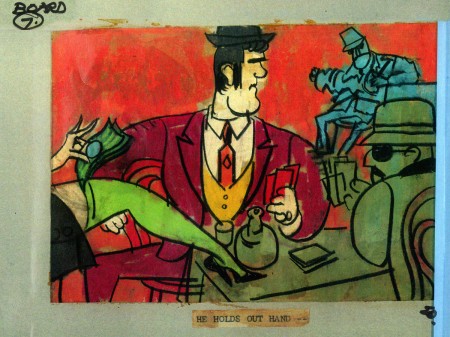

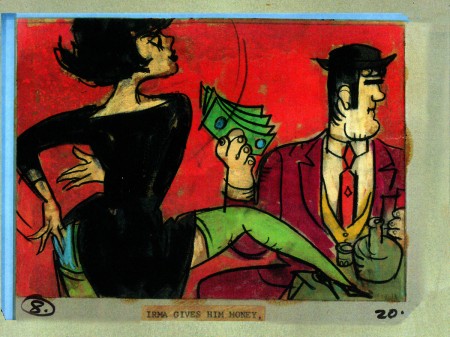

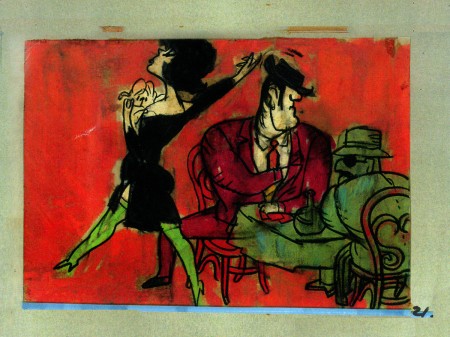

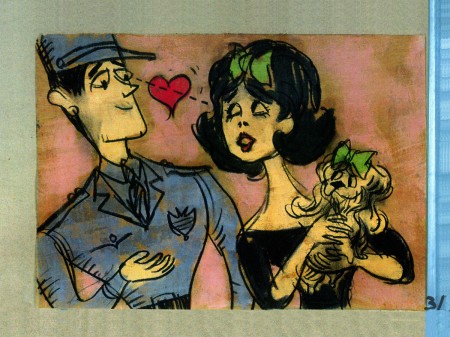

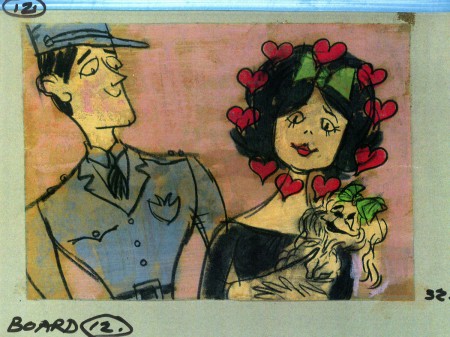

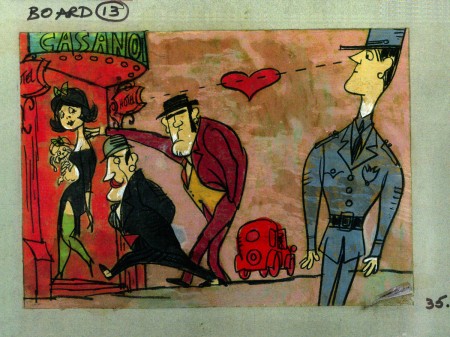

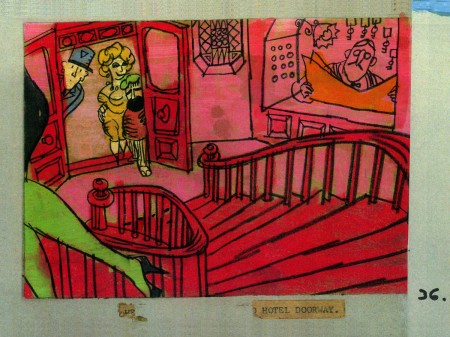

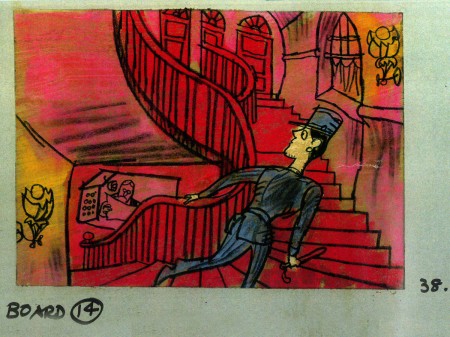

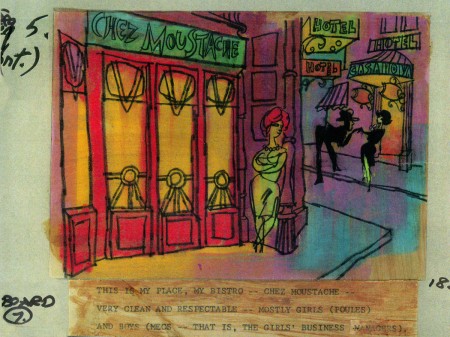

The film started with some nicely drawn animated credits which were done by John Wilson’s studio. Until recently I hadn’t known that Wilson also produced an animated short promoting the feature for the Mirisch Company. I have some preproduction art from that short as well as the color storyboard. The board is large enough that I’ve decided to break it into two parts. We’ll see part one today and the second part next week.

Each section of three images is long enough that unless I post one drawing at a time, it’ll be too tiny to see unless enlarged. I’d like to post each storyboard sketch a nice viewing size and still give you the option of enlarging it.

Let’s start with some production and post production stills so you can see what it looked like.

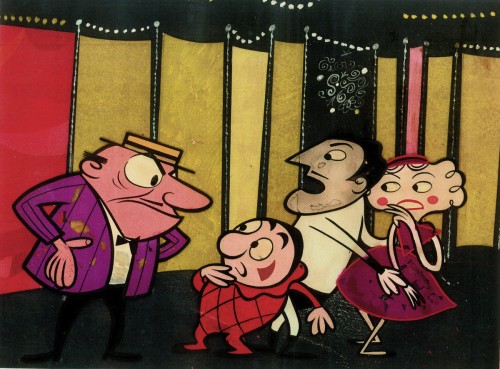

1

1

A couple of pre-production drawings:

1

1

Then, there’s the storyboard. I’ll give an example of the three panel pull out and follow that with each individual image.

You can see why I’ve decided to enlarge the images.

4.

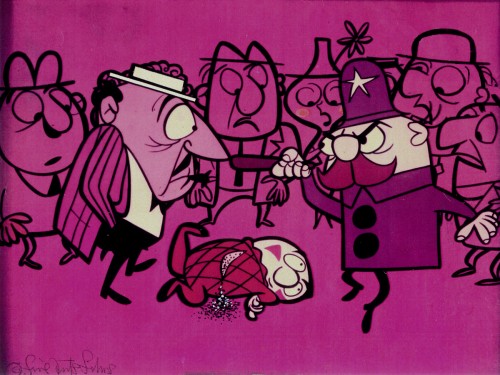

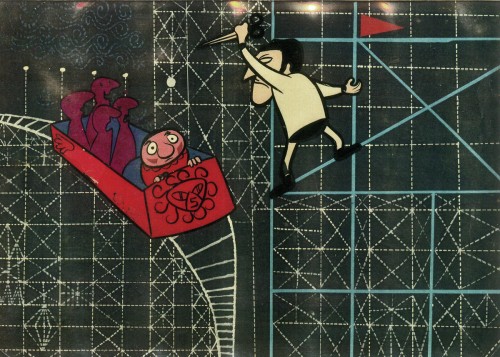

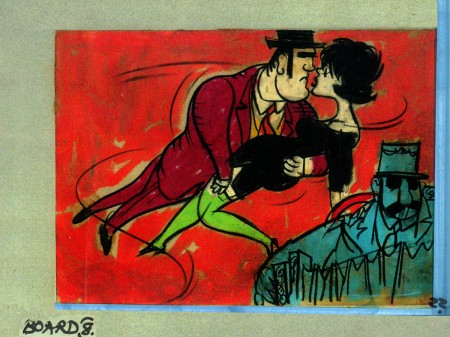

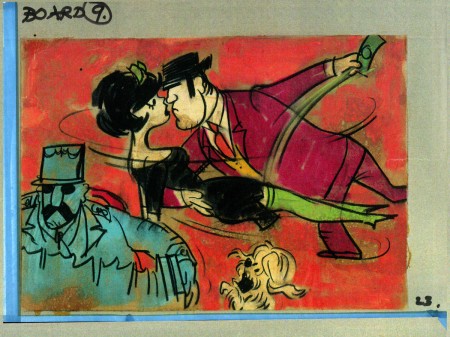

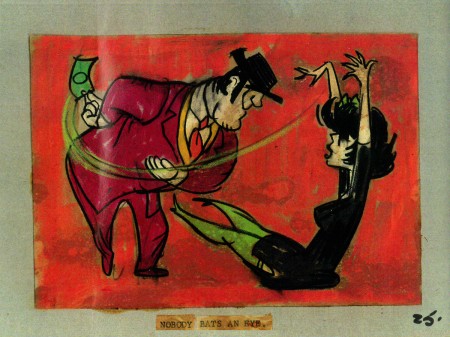

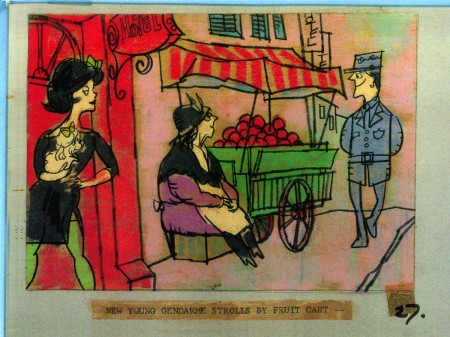

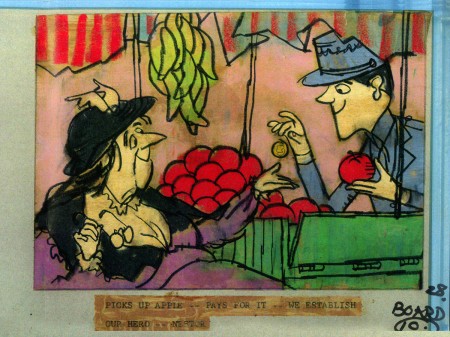

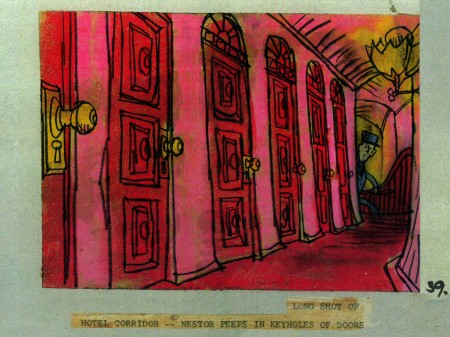

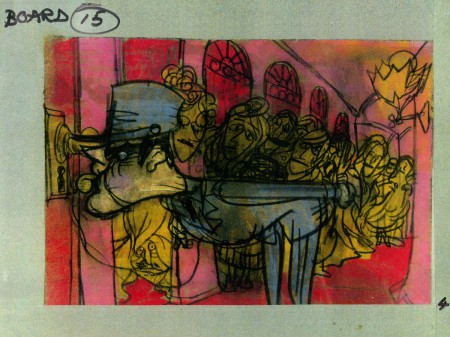

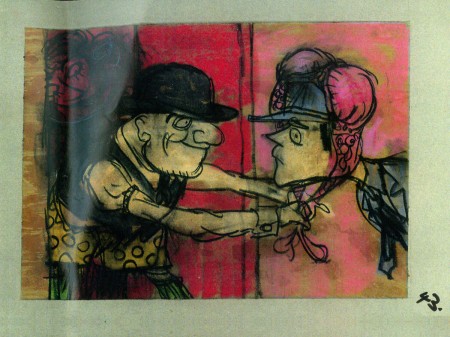

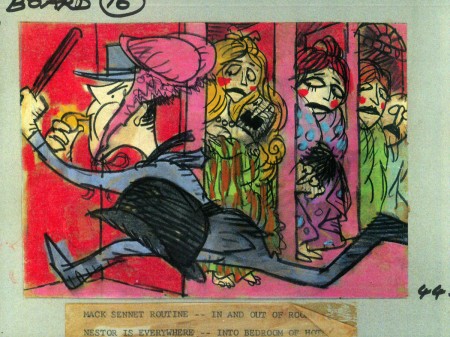

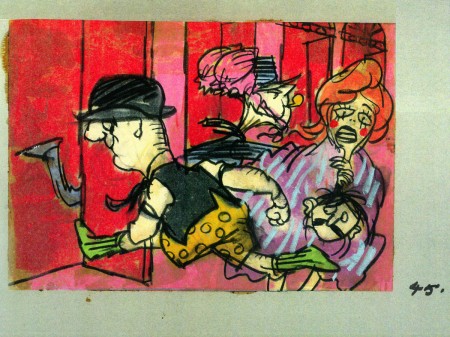

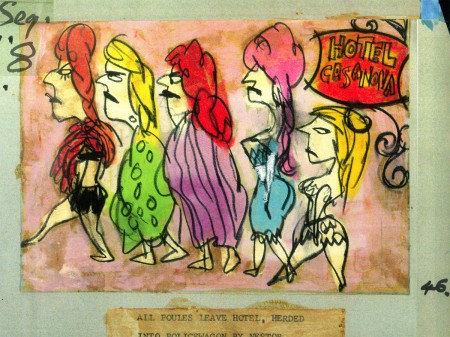

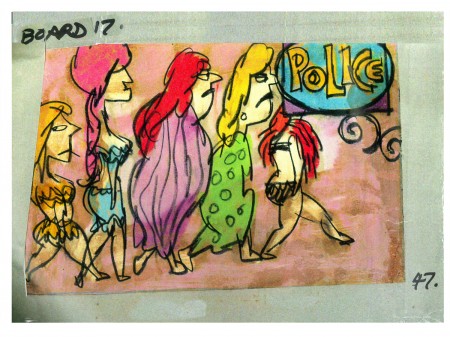

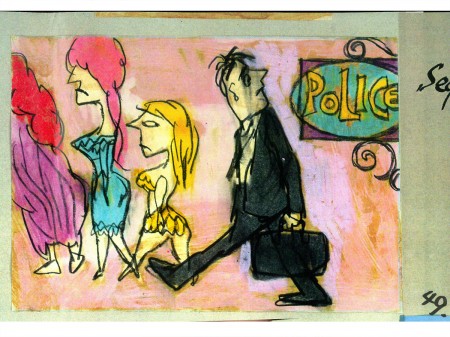

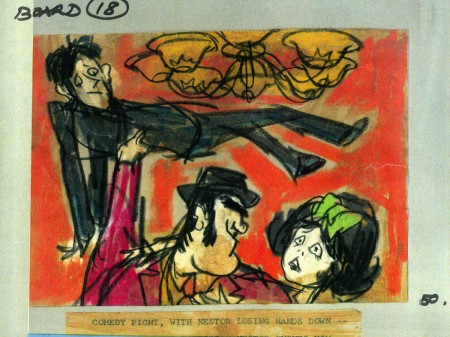

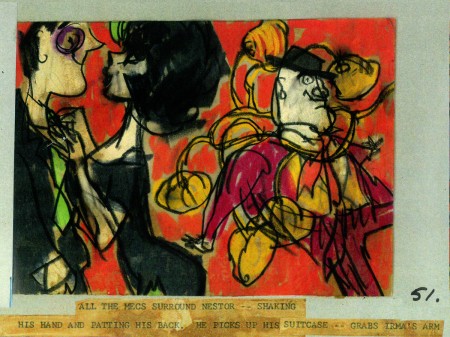

John Wilson created this storyboard for the Mirisch Corp. It was an animated trailer to promote Billy Wilder‘s coming film, Irma La Douce. The board comes in 18 pages of three storyboard drawings. Rather than post the sets of three images (and only being able to show them at a smallish size) I’ve taken each individual drawing and have blown them up to see them better on this blog.

Again, these were for a lengthy trailer for the film not the opening credits. The film’s credits do not use animation.

7a

___________________________

7a

___________________________

Here’s a YouTube version of the trailer. Not the brightest quality, but you can see it.

5.

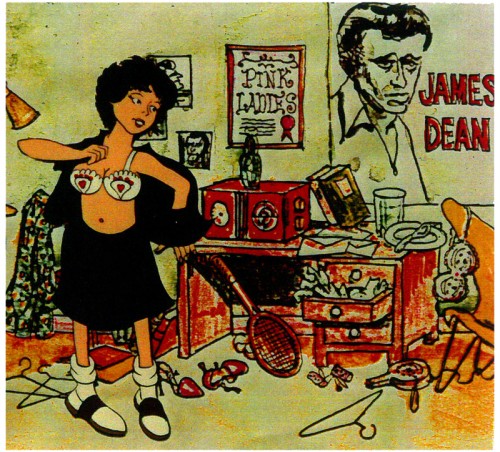

- Don Marquis‘ book, Archy and Mehitabel, garnered fame quickly and not least because of the extraordinary illustrations of George Herriman, the creator of Krazy Kat.

- Don Marquis‘ book, Archy and Mehitabel, garnered fame quickly and not least because of the extraordinary illustrations of George Herriman, the creator of Krazy Kat.

The first book was published in 1927 and others followed in 1933 and 1935. It wasn’t until the third book that Herriman took over the characters created by Marquis in his book of short stories, developed mostly, in poetry. An on-again off-again love affair, the story had two principal characters: a cat, Mehitabel, and Archy, cockroach. (You can read these poems on line here.)

In 1953, writer Joe Darion along with composer George Kleinsinger (the creator of Tubby the Tuba) wrote a musical theater piece. Tenor Jonathan Anderson played Archy and soprano Mignon Dunn was Mehitabel. At about the same time a recording of the showtunes was recorded with Carol Channing as Mehitabel and Eddie Bracken as Archy. The record was a success.

With the help of the young writer, Mel Brooks, they were able to get their show to Broadway in 1957, but it was now named Shinbone Alley. After 49 performances, the show closed, but the original cast album was recorded that same year. The songs stayed in the permanent repetoire of Carol Channing and Eartha Kitt.

In 1971, John Wilson directed an animated feature starring the voices of Channing and Brackett and using the songs from the musical. The love affair between Archy and Mehitabel was penned by Archy, the cockroach; his poems tell their story.

In 1971, John Wilson directed an animated feature starring the voices of Channing and Brackett and using the songs from the musical. The love affair between Archy and Mehitabel was penned by Archy, the cockroach; his poems tell their story.

The film suffers from its music. The songs are simple and sound as if they’re written for children, but the lyrics pull from the poems which are definitely designed for adults. It gets a bit confusing, as a result, and is a bit picaresque; the poems are short and illustrating them in animation would take more adaptation than seen here.

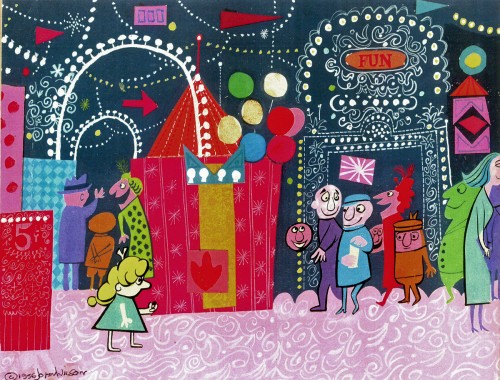

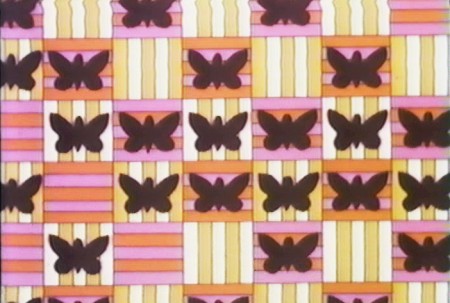

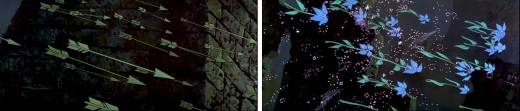

John Wilson had developed his studio, Fine Arts Films, on the back of the weekly, animated, music videos he did for The Sonny and Cher Show, an enormous hit in the early 70s.

John Wilson had developed his studio, Fine Arts Films, on the back of the weekly, animated, music videos he did for The Sonny and Cher Show, an enormous hit in the early 70s.

These music videos were loose designs animated quickly and lively around the songs Sonny & Cher would schedule each week. There would always be one or two of these pieces, and they were highlights in the weekly one-hour musical/variety program.

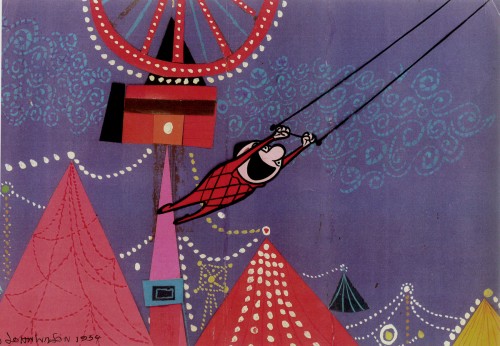

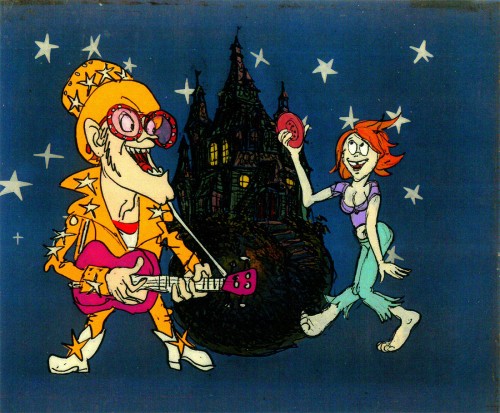

The graphics of Shinbone Alley aren’t too far from these Sonny & Cher videos. Loose design and animation with a design style not too far from the Fred Wolf’s made-for-ABC feature, The Point. This was the first feature made for television and featured the songs and story of Harry Nilsson, although Shinbone Alley featured a wilder color pallette.

The graphics of Shinbone Alley aren’t too far from these Sonny & Cher videos. Loose design and animation with a design style not too far from the Fred Wolf’s made-for-ABC feature, The Point. This was the first feature made for television and featured the songs and story of Harry Nilsson, although Shinbone Alley featured a wilder color pallette.

Jules Engel, Corny Cole and Sam Cornell all worked in design on the film. The long list of  animators included Barrie Nelson, John Sparey, Spencer Peel, Eddie Rehberg and Jim Hiltz. Mark Kausler was an assistant on the show.

animators included Barrie Nelson, John Sparey, Spencer Peel, Eddie Rehberg and Jim Hiltz. Mark Kausler was an assistant on the show.

The film wasn’t an enormous success, but that was probably explained much by the limited distribution and the poor marketing of the film. I saw the film when it came out; I was living in Washington DC at the time (in the Navy). I was very disappointed. The animation is very limited and the style was a real let-down having known the George Herriman illustrations from the Don Marquis book. We’d already seen those limited animation Krazy Kat cartoons from King Features, so I knew the style could be done adequately – even on a budget. The style in this film just seemed a little too Hollywood cute, at the time, and it felt dated when it came out. I don’t feel too differently about it watching the VHS copy I own.

the film’s poster

Here are some frame grabs from the first 1/4 of the film:

We’re introduced to Archy right off the bat as he

flies out of the river onto the dock. He realizes that he,

the poet, tried to kill himself and was sent back as a cockroach.

He soon finds a typewriter and goes straight back to work.

Mehitabel is a performer – with Carol Channing’s voice.

She has another boyfriend, voiced by Alan Reed,

who is also the voice of Fred Flintstone.

A song video takes us outside.

6.

- This final post featuring the work of John Wilson and his company, Fine Art Films, covers many varied film projects. Unfortunately, I found relatively few images available for posting especially considering the amount of film done.

The Sonny and Cher Show was a long running Variety program on television in the 70s. Most weeks featured an animated music video as done by John Wilson. Some examples of this include:

Helen Reddy’s song “Angie Baby”

Joni Mitchell’s “Big Yellow Taxi”

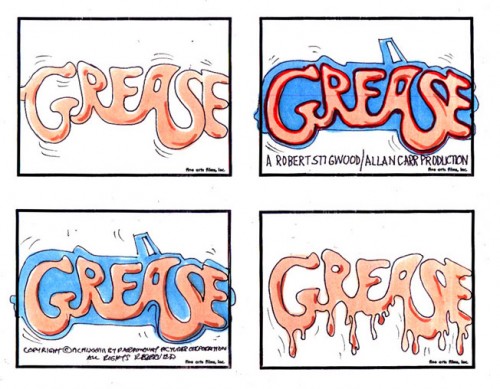

Fine Arts Films also did some movie titles and trailers. We saw, recently, the long theatrical trailer done for Irma La Douce. Here are a few stills done for the main title sequence for the 1978 musical, Grease.

storyboard sketch for Grease.

Produced and Directed by John Wilson

Story and Layout by Chris Jenkyns

Music by Barry Gibb

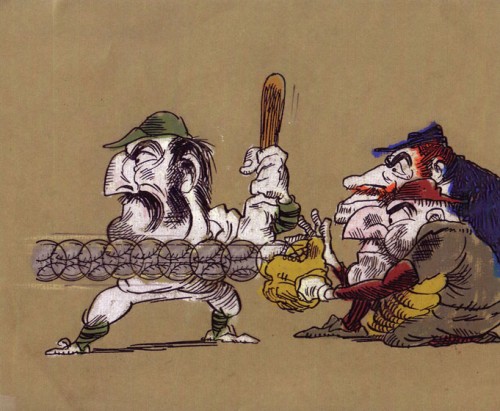

John Wilson also directed a number of short films which appeared on television on the NBC program, “Exploring” between 1964-1966.

“Casey At the Bat”

Narrated by Paul Frees

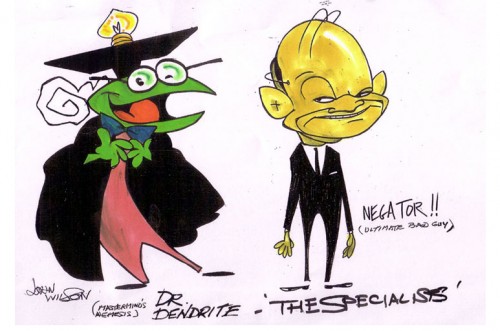

Finally, for MTV’s “Liquid Television” in 1992 John Wilson directed some of the 10 episodes of a series called “The Specialists.”

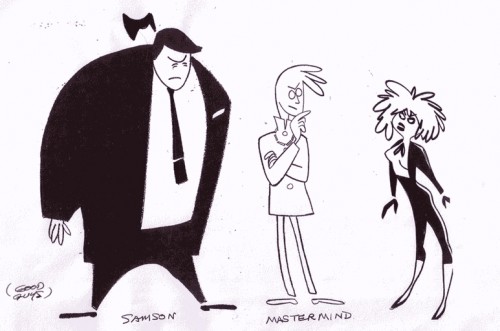

1

1

Go here to see other episodes.

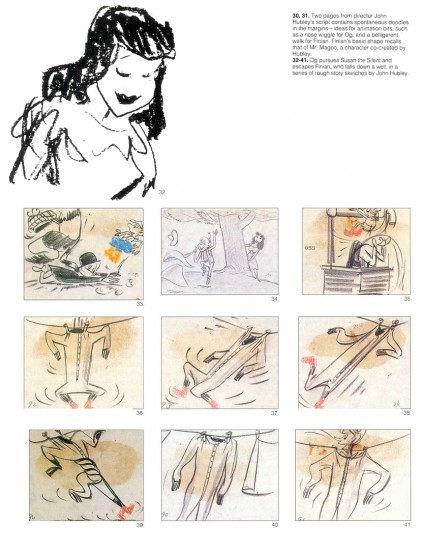

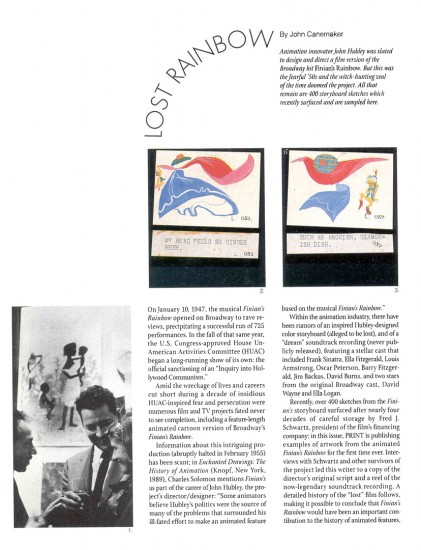

Animation Artifacts &Articles on Animation &Hubley &Independent Animation &John Canemaker 16 Jun 2013 04:53 am

Finian’s Rainbow

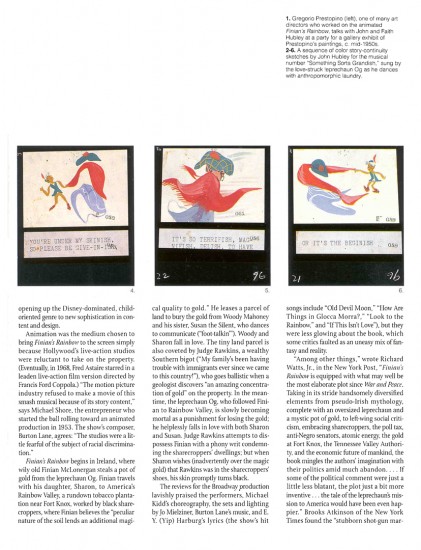

This article by John Canemaker is, to me, one of the most important pieces I’ve ever posted. I want to continue to give it some fresh air time, and I think today’s the day to post it anew. It’s one of the great articles ever printed in Print Magazine and a brilliant piece of historic recreation by John Canemaker. I’ve read it a couple dozen times, and am about to read it again, now. (Yesterday, I heard Duke Ellington perform “Tenderly” on the radio and that was enough to prompt me to repost it. I’d intimately known the Oscar Peterson/Ella Fitzgerald version of the song. Here was Ellington’s version which literally took the song apart and reconstructed it. Art was performed in front of me thanks to local radio.)

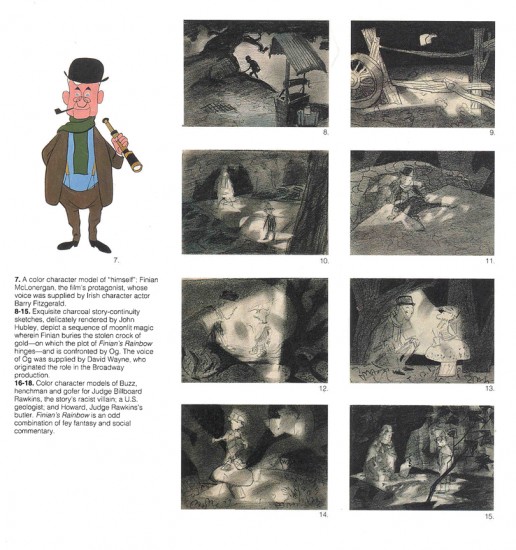

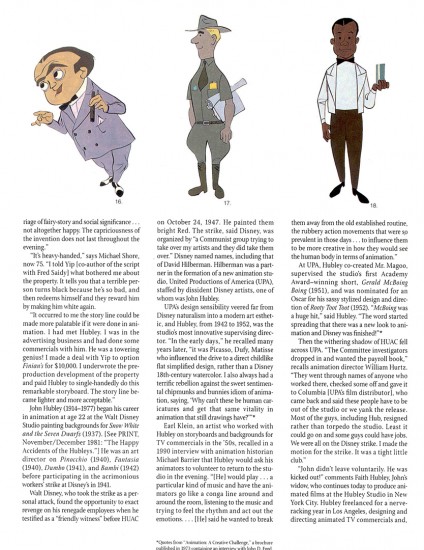

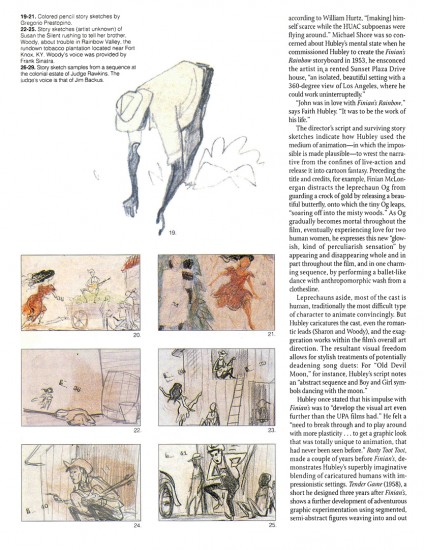

- A treasure of a piece, John Canemaker wrote an article for the March/April 1993 edition of Print magazine an article about Finian’s Rainbow. This was an animated feature well under way in 1953 to be directed by John Hubley. It was to be an adaptation of the successful Broadway musical by Burton Lane and E.Y. Harburg. The film about racism twisted into a fantasy story about love and leprechauns would have been the first official adult film done by a team of brilliant animation artists. The soundtrack would have featured songs sung by Frank Sinatra, Ella Fitzgerald, Louis Armstrong, Oscar Peterson and Jim Backus.

- A treasure of a piece, John Canemaker wrote an article for the March/April 1993 edition of Print magazine an article about Finian’s Rainbow. This was an animated feature well under way in 1953 to be directed by John Hubley. It was to be an adaptation of the successful Broadway musical by Burton Lane and E.Y. Harburg. The film about racism twisted into a fantasy story about love and leprechauns would have been the first official adult film done by a team of brilliant animation artists. The soundtrack would have featured songs sung by Frank Sinatra, Ella Fitzgerald, Louis Armstrong, Oscar Peterson and Jim Backus.

I remember hearing stories about animation in production at the Bill Tytla studio, with Tytla animating on it. In Hollywood, Art Babbitt and Bill Littlejohn were animating, with Paul Julian, Aurelius Battaglia and Gregorio Prestipino art directing. Maurice Binder had assembled a LEICA reel.

Senator Joseph R McCarthy and the HUAC investigation brought the entire project down to ground and set back the history of animation some 30 years.

John Canemaker has generously allowed me to post this article again; I wanted to celebrate the artist and director,John Hubley.

1

1

The story told to me by several people came most faithfully from Jim Logan, a long-time Asst. Animator working for Bill Tytla and sitting at a desk nearest Tytla’s office. Within his office there was a wall of mirrors. Tytla was in the middle of a hand out of a scene from Finian’s Rainbow. He was acting as an animation director for Hubley. He wanted the animator to practice the dance steps with him in front of the mirror. The animator was embarrassed to be asked to roll up his pants legs so he could better see how the move should animate.

Tytla was in his element. This was the first time since he’d left Disney’s that he was really being asked to do animation, get animation out of his staff for this eccentric and thoroughly adult animated feature. It was about Racism in 1956, and it was a serious attempt to do something serious and political and funny – all at the same time. Within days the animated scene had been collected by the producers who lost all their financing because of a ridiculous anti-communist comment thrown Tytla’s way. Tytla wasn’t the only one who lost; Hubley did as well. As a matter of fact, the entire industry lost. A second rate journalist made easy accusations, and the only thing to be done was to shut the production down.

Years later a young Francis Ford Coppola directed a young Petulia Clark with another Brit, song and dance man, Tommy Steele, playing the mischievous leprechaun. Needless to say, that film is a minor effort from Coppola’s resume.

Action Analysis &Animation &Articles on Animation &Books &Commentary &Disney &Illustration &Richard Williams &Rowland B. Wilson &SpornFilms &Story & Storyboards &Tissa David 10 Jun 2013 03:31 am

Illusions – 3

I’ve written two posts about Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston‘s book, The Illusion of Life the last couple of weeks. I came to the book only recently and realizing that I’d never really read the book, I thought it was time. So in doing so, I’ve found that I have a lot to write about. The book has come to be accepted almost as gospel, and I decided to give my thoughts.

There were two major complaints I’ve had with what I’ve read in their book so far, and I spent quite a bit of time reviewing those.

- First out of the box, I was stunned to read that these two of Disney’s “nine old men” said that they’d originally believed that each prime animator should control one, maybe two characters in the film. Then, later in life they decided that an animator should do an entire scene with all of the characters within it. This is not what I’d seen the two (or the nine) do in actual practice. post 1

Secondly, they argue for animating in a rough format, and they give solid reasons for this. As a matter of fact, it was Disney, himself, in the Thirties who demanded the animators work rough and solid assistants who could draw well back them up. Then much later in the book the two author/animators suggest that it’s better for an animator to work as clean as possible with assistants just doing touch-up. This helped out the Xerox process, but didn’t necessarily help for good animation. post 2

The book starts out sounding like it’s going to be a history of Disney animation, but then starts getting into the rules of animation (squash and stretch, overlapping action and anticipation and all those other goodies) exploiting Disney animation art in demonstration. Soon the book moved into storytelling and how to try to keep the material fresh and interesting. It all becomes a bit obvious, but you keep hoping that some great secret will be revealed by the two masterful oldsters.

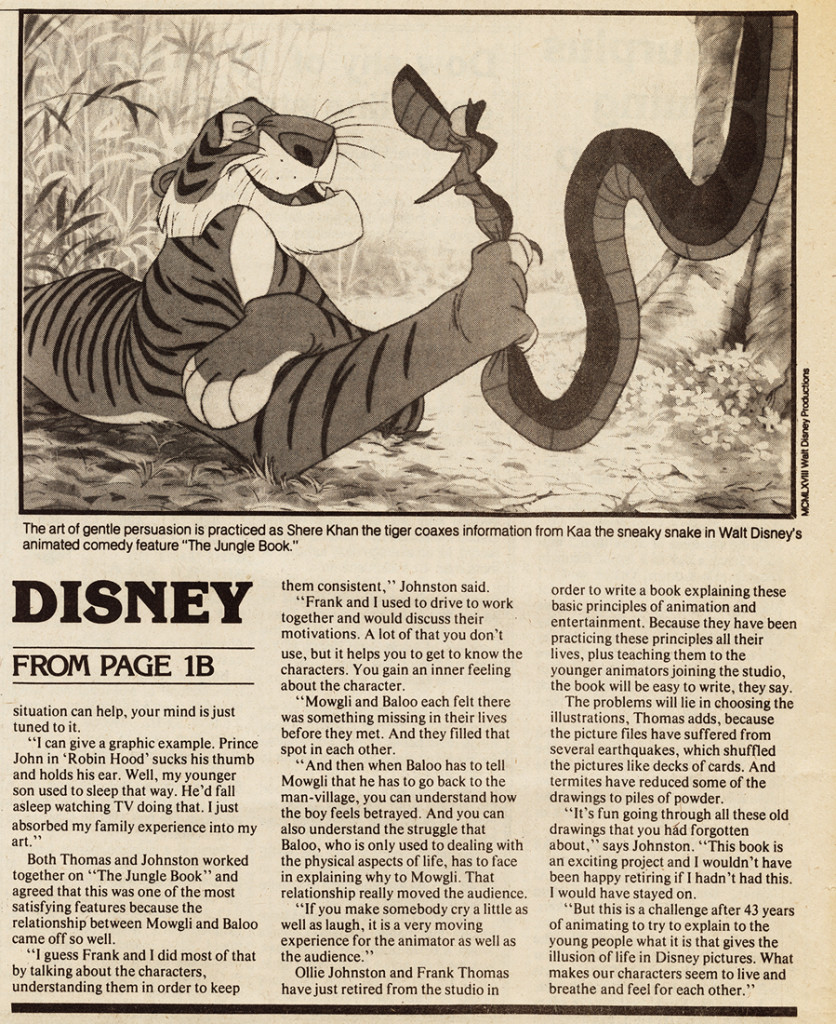

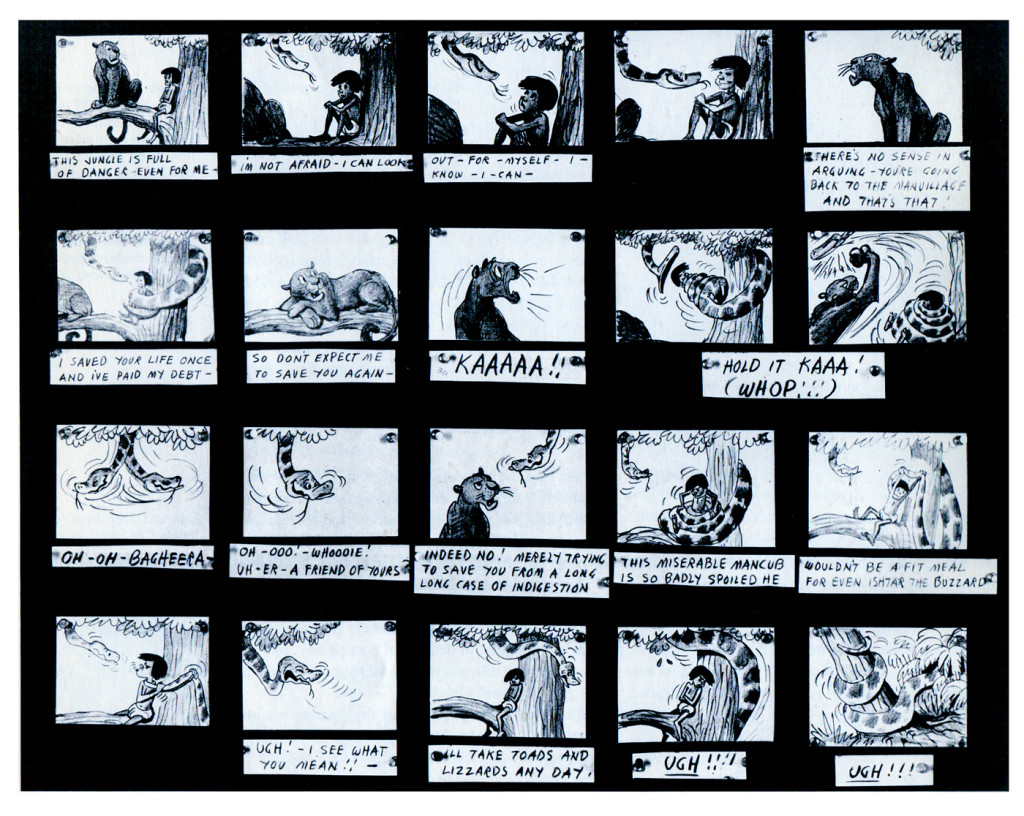

They do go into depth about how to develop characters when making animated films. They offer lots of examples from Orville, the albatross in The Rescuers to the three fairies in Sleeping Beauty, but their greatest attention goes to Baloo the Bear in The Jungle Book. They were having a hard time with this guy; they had been trying to do an Ed Wynn type character, until Walt Disney, himself, suggested Phil Harris. Once they auditioned Harris, they knew they were on the right track, and the character kept grabbing more screen time and grew ever larger. In the end, audiences just loved him.

They do go into depth about how to develop characters when making animated films. They offer lots of examples from Orville, the albatross in The Rescuers to the three fairies in Sleeping Beauty, but their greatest attention goes to Baloo the Bear in The Jungle Book. They were having a hard time with this guy; they had been trying to do an Ed Wynn type character, until Walt Disney, himself, suggested Phil Harris. Once they auditioned Harris, they knew they were on the right track, and the character kept grabbing more screen time and grew ever larger. In the end, audiences just loved him.

Personally, I’ve always hated Phil Harris’ performance in this film. What was it doing in Rudyard Kipling’s book? When I was a kid, Harris and Louis Prima were the perfect examples of my father’s entertainers. He loved these guys and spent a lot of time in front of the family TV watching the Dinah Shore Show______Tom Oreb designs for Sleeping Beauty.

and other such entertaining Variety Shows with

lots of little 50′s big-band jazz-type acts. I hated it; this was my parent’s kind of music and humor and had nothing to do with me. I was the kid who paid his quarter to see the Walt Disney movies (that was the children’s price of admission in 1959.)

In their book they say they knew he was perfect because generations of kids later (who have no idea who Phil Harris was) still take joy from Baloo. What they forgot is what I knew all along. This was The Jungle Book. If they had been truly creative, they would have developed a character in line with Kipling’s material that would have been an original, not an impersonation of Doobey Doobey Doo, Phil Harris. The same is true of Louis Prima as a monkey. (There was a time when Disney said that they should never animate monkeys because monkeys are funny on their own, in real life. Animation wouldn’t make them funnier.) Sebastian Cabot, as Bagheera, works as does George Sanders as Shere Khan.

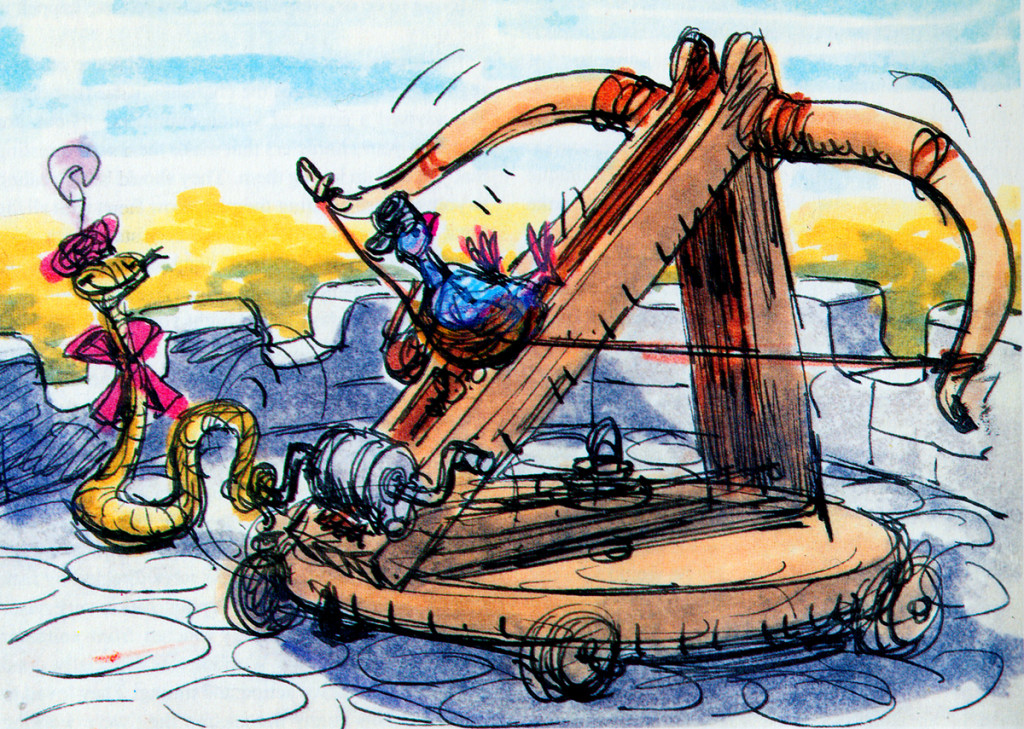

- Right: A discarded sequence from Robin Hood showed a messenger pigeon so fat and heavy he had to be shot into the air. This gave the animators the beginnings of The Albatross Air Lines in The Rescuers.

Phil Harris was so successful, they dragged him into Robin Hood as well. Robin Hood. The very same character from The Jungle Book is now Little John! All those cowboy voices in Robin Hood don’t work either, especially when you mix them up with Brits like Peter Ustinov and Brian Bedford. When these two thespians work against Pat Buttram, Andy Devine and George Lindsey, it’s one thing. Throw in a Phil Harris, and you have something else again. Where are we, the audience, supposed to be? Is it “Merry Ol’ England”? Or is it the lazy take on character development by a few senior animators who have taken license to jump away from the story writers for the sake of easy characters of the generation they’re familiar with. Robin Hood is a mess of a story – even though it’s a solid original they’re working from, and I find it hard to take written advice from these fine old animation pros who take an easy way out for the sake of their animation; shape shifting classic tales to fit their wrinkles.

At least, that’s how I see it – saw it. And perhaps that’s why it’s taken me so long to read this book. I felt (at the age of 14 when these films came out) that the Disney factory had turned into something other than the people who’d made Snow White and Bambi and Lady and the Tramp.

They had, in fact, become the nine old men.

The Jungle Book was the last film Bill Peet worked on. He left

before the film was done. He’d had a long, contentious relationship

with Disney. He never felt he’d gotten the respect he deserved.

They were incredibly talented animators, and they certainly knew how to do their jobs. The animation, itself, was first rate (sometimes even brilliant as Shere Khan demonstrates), but try comparing the stories to earlier features. Even Peter Pan and Cinderella are marvelously developed. Artists like Bill Peet and Vance Gerry knew how to do their jobs, and they did them well. When Peet quit the studio, because he felt disrespected, Disney’s solid story development walked out the door.

The animators were taking the easy route rather than properly developing their stories. The stories had lost all dynamic tension and had become back-room yarns. Good enough, but not good.

Today was Nik Ranieri‘s last day at Disney’s studio. He’s definitive proof, in the eyes of Disney, that 2D animation is dead as an art form. This is the end result of some of the changes Thomas and Johnston suggest in their book. The medium took a hit back then; it just took this long for the suits to catch up. Good luck to Nik and the other Disney artists who no longer work steadily in what is still a vitally strong medium.

Articles on Animation &Commentary &commercial animation &Disney 22 May 2013 04:35 am

Press

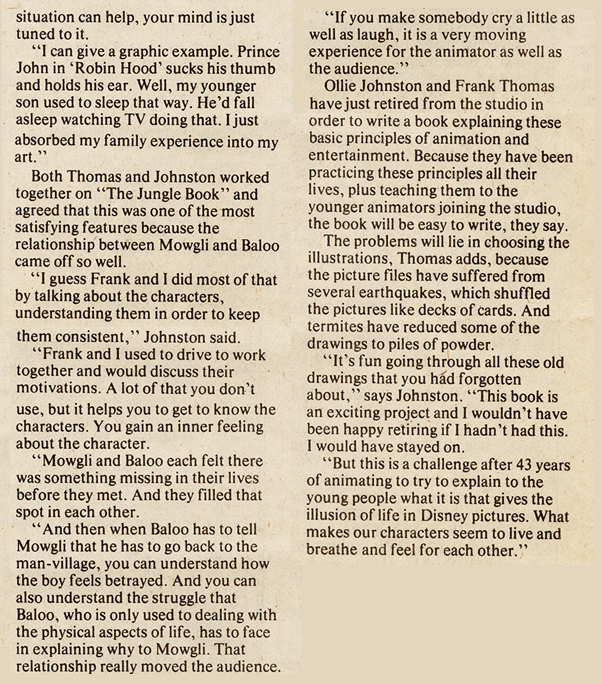

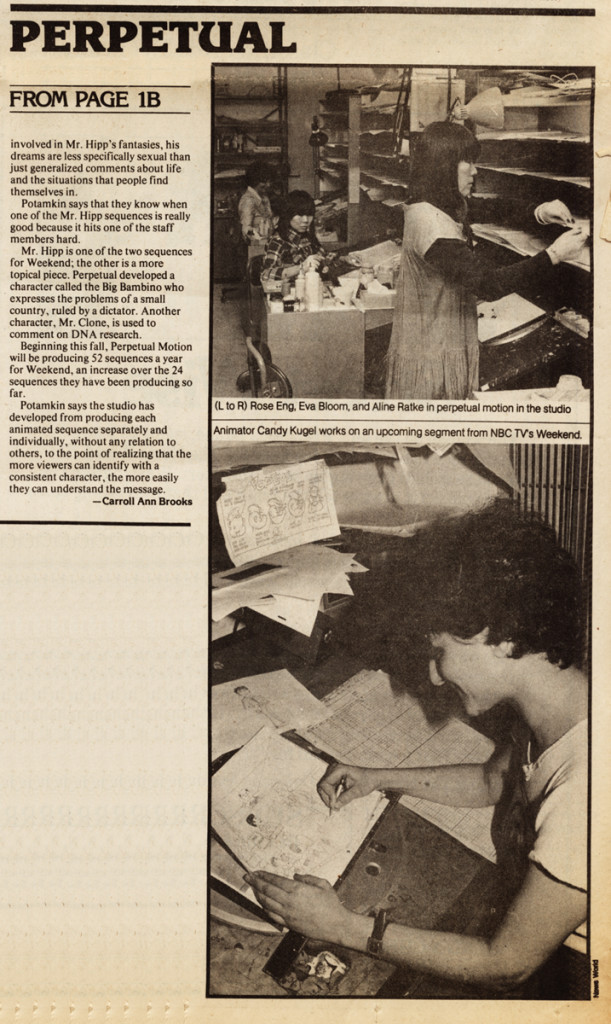

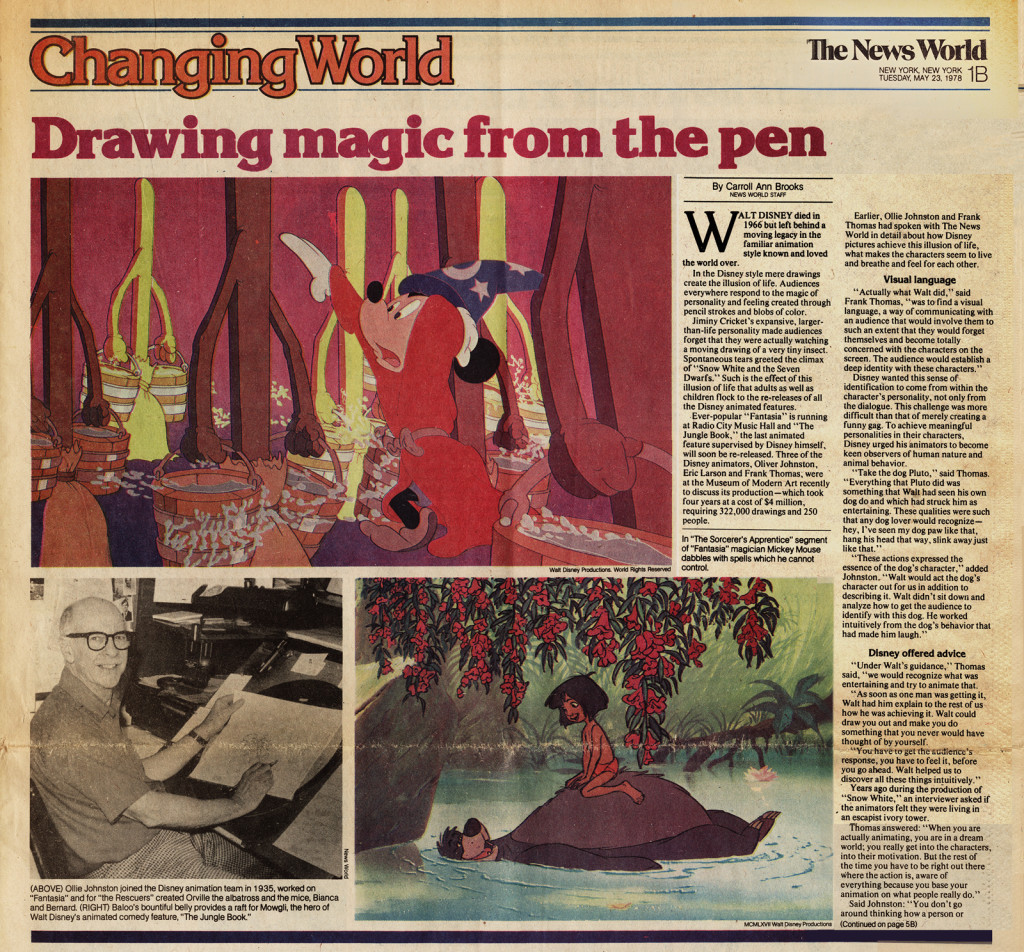

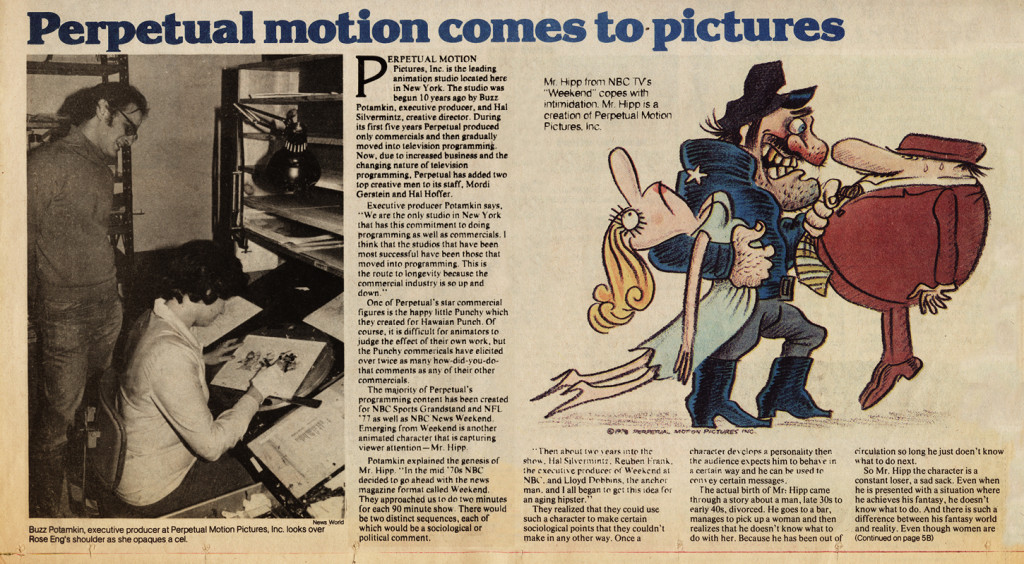

Among the remains of the material saved by Vince Cafarelli, there was this newspapaer, The News World, dated Tues. May 23, 1978. On the same page, there were two articles about animation.

Once was a piece about Disney’s Jungle Book, which was just about to be released. The second was an article about Perpetual Motion Pictures. This, of course, was the company where Vinnie and Candy worked with Buzz Potamkin producing and Hal Silvermintz designing.

Below, I post first the two parts of the Disney article (I’ve also singled out just the type in case you want to read at a larger scale.)Then I follow with the two parts of the Perpetual Motion article.

The Disney article (part 1)

The following is the article about Perpetual Motion Pictures:

Perpetual article (Part 1)

Animation Artifacts &Articles on Animation &Commentary &Puppet Animation &repeated posts 08 May 2013 12:49 am

Ray Harryhausen (6/29/1920 – 5/7/2013)

- Greg Kelly, a good friend of this blog, wrote to tell me that Ray Harryhausen has died. You can read about it here, in Time Out or here in the NY Times or here at Jerry Beck‘s Animation Scoop.

Thanks, Greg, for the alert.

In honor of Mr. Harryhausen’s brilliant career, I’m re-posting this article about Jason and the Argonauts which I once posted. The piece features Jason and the Argonauts. There was a chapter from Mr. Harryhausen’s 1972 book, Film Fantasy Scrapbook, about that film. I’d like to show it again. The book is written in the first person singular and collects B&W images like a scrapbook.

Here it is:

Of the 13 fantasy features I have been connected with I think Jason and the Argonauts pleases me the most. It had certain faults, but they are not worth detailing.

Its subject matter formed a natural storyline for the Dynamation medium and like The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad strayed far from the conventional path of the “dinosaur exploitation film” with which this medium seemed to be identified.

Taking about two years to make, it unfortunately came out on the American market near the end of a cycle of Italian-made dubbed epics based loosely on the Greek-Roman legends, which seldom visualized mythology from the purely fantasy point of view. But the exhibitors and the public seem to form a premature judgment based on the title and on the vogue. Again, like Sinbad, the subject brewed in the back of my rnind for years before it reached the light of day through producer Charles Schneer. It turned out to be one of our most expensive productions to date and probably the most lavish. In Great Britain it was among the top ten big money makers of the year.

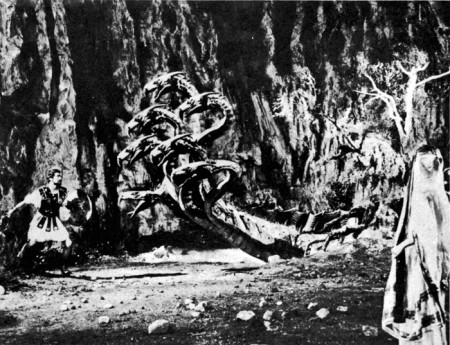

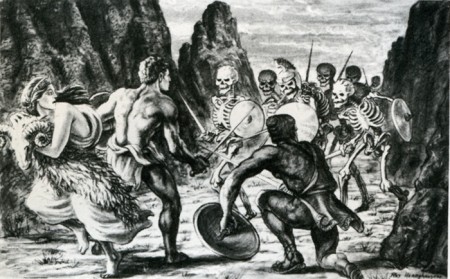

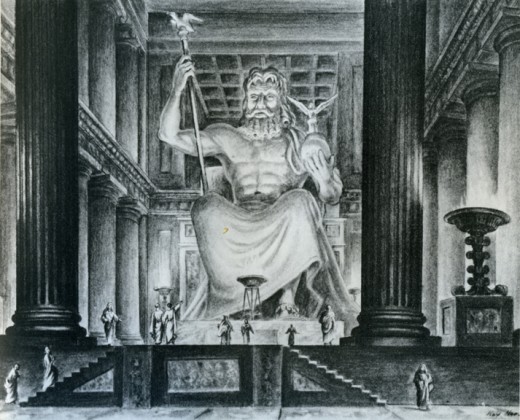

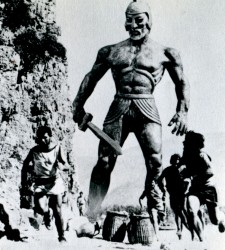

A preproduction drawing (above) compares favorably with a film still (below.)

The drawing is quite a bit more dynamic. (After all, it is Dynamation!)

(Click any image to enlarge a bit.)

Likewise, a drawing of the hydra (above) film still (below.)

Some of the difference in basic composition between the pre-production sketches I made for Jason and the counterparts frames of the production is the direct result of compromising with available locations.

For example, the ancient temples in Paestum, southern Italy, finally served as the background for the “Harpy” sequence. Originally we were going to build the set when the production was scheduled for Yugoslavia. Wherever possible we try to use an actual location to add to the visual realism. To my mind, most overly designed sets one sees in some fantasy subjects can detract from, rather than add to the final presentation.

Again, it depends on the period in which it is made as well as on the basic subject matter. Korda’s The Thief of Bagdad was the most tastefully produced and designed production of any film of this nature but unfortunately the budget that was required would be prohibitive with today’s costs.

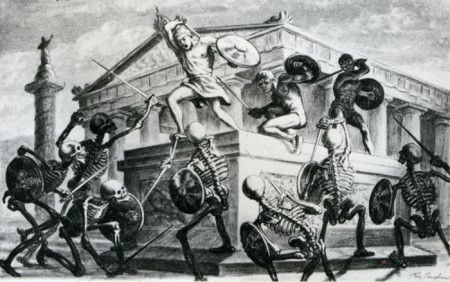

The Skeleton Sequence was the most talked-ahout part of Jason. Technically, it was unprecedented in the sphere of fantasy filming. When one pauses to think that there were seven skeletons fighting three men, with each skeleton having five appendages to move each frame of film, and keeping them all in synchronization with the three actors’ movements, one can readily see why it took four and a half months to record the sequence for the screen.

My one regret is that this section of the picture did not take place at night.

Its effect would have been doubled.

Certain other time-consuming technical “hocus-pocus” adjustments had to be done during shooting to create the illusion of the animated figures in actual contact with the live actors. Bernard Herrmann’s original and suitably fantastic music score wrapped the scenes in an aura of almost nightmarish imagination.

In the story, Jason’s only way of escaping the wild battling sword wielding “children of Hydra’s teeth” is to leap from a cliff into the sea. (Above left) A stuntman, portraying Jason for this shot, leaps from a 90-foot-high platform into the sea closely followed by seven plaster skeletons. It was a dangerous dive and required careful planning and great skill. It becomes an interesting speculation when dealing with skeletons in a film script. How many ways are there of killing off death?

(Above right) Another angle with the real Jason jumping off a wooden platform into a mattress a few feet below. The skeletons and the rocky cliff were put in afterwards while the mattress was blotted out by an overlay of sea.

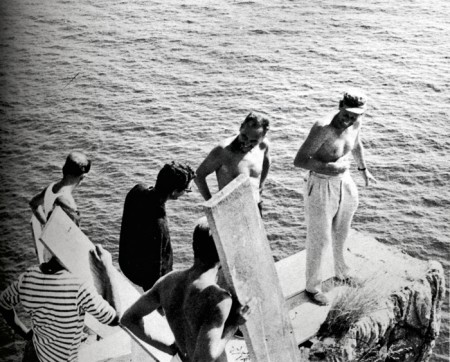

Director Don Chaffey and Ray Harryhausen discuss the leap

with Italian stunt director Fernando Poggi.

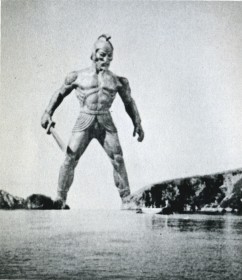

When transferring published material to the screen it is almost always necessary to take certain liberties in the work in order to present it in the most effective visual terms. Talos, the man of bronze, did exist in Jason legend, although not in the gigantic proportions that we portrayed him in the film. My pattern of thing in designing him on a very large scale stemmed from research on the Colossus of Rhodes.

The actor: his blocking the only entrance to the harbor stimulated many exciting possibilities. Then too, the idea of a gigantic metal statue coming to life has haunted me for years, but without story or situation to bring it to life. It was somewhat ironic when most of my career was spent in trying to perfect smooth and life-like action and in the Talos sequence, the longest animated sequence in the picture, it was necessary to make his movements deliberately stiff and mechanical.

Most of Jason and the Argonauts was shot in and around the little seaside village of Palinuro, just south Naples. The unusual rock formations, the wonderful white sandy beaches, and the natural harbor were within a few miles of each other, making the complete operation convenient and economical. Paestum, w its fine Greek temples, was just a short distance north. All interiors and special sets were photographed in a sm studio in Rome.

(Above left) Talos, the statue of bronze, pursues Jason’s men.

(Above left) Talos, the statue of bronze, pursues Jason’s men.

(Above right) Talos blocks the Argo

from the only exit of the bay.

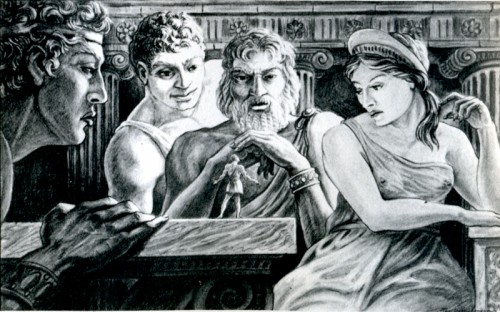

Pre-production drawing of Jason speaking to the Gods of Greece.

For the second unit operation a special platform had to be fitted to the Argo in order to achieve certain camera angles. Although it looks precarious it was far more convenient than using another boat for the shots.

The Argo had to be, above all, practical in the sense that it must be seaworthy as well as impressive. It was specially constructed for the film over the existing framework of a fishing barge. There were twin engines for speed in maneuvering, which also made the ship easily manipulated into proper sunlight for each new set-up.

Harryhausen off the book’s back cover

to give an idea of scale of drawing sizes.

Animation Artifacts &Articles on Animation &Disney &Illustration &John Canemaker &Story & Storyboards 29 Apr 2013 06:19 am

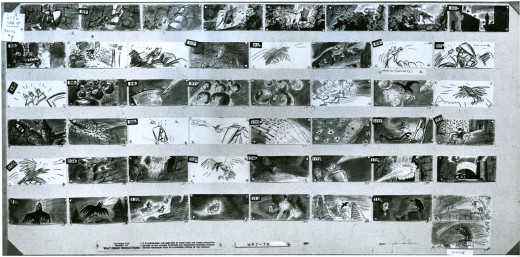

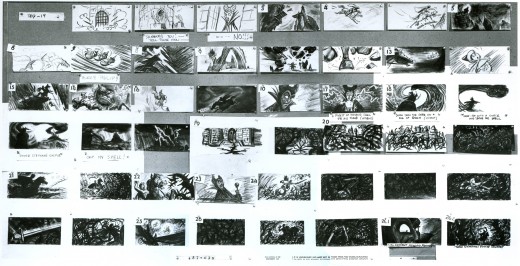

Sleeping Beauty Storyboard – seq 19

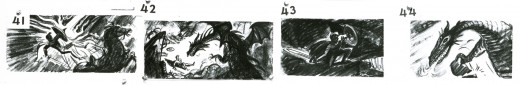

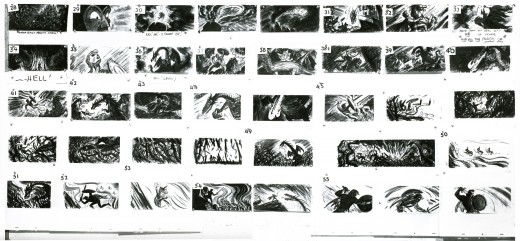

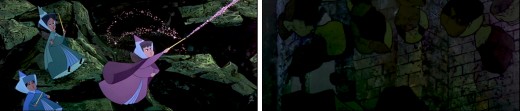

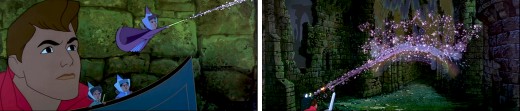

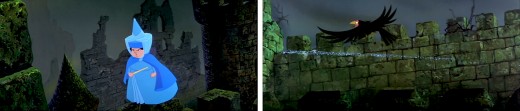

- John Canemaker had loaned me the final sequences of the storyboard to Sleeping Beauty, detailing the dragon fight and climax of the film. I originally posted this in three parts. I’ve combined them all here, making for one long post.

- John Canemaker had loaned me the final sequences of the storyboard to Sleeping Beauty, detailing the dragon fight and climax of the film. I originally posted this in three parts. I’ve combined them all here, making for one long post.

I’m not sure who did the artwork, but there’s a good chance it’s Ken Anderson‘s work.

As with past boards, I’ll post the whole photograph as is, then take it apart row by row so that you can enlarge them as much as possible. Here’s the storyboard sequence #19 from Sleeping Beauty.

The full board follows below:

(Click any image to enlarge.)

The breakdown of that full board follows:

1a

1a

Here’s the next full page of storyboard as is:

(Click any image on the page to enlarge.)

Again, I follow with the board broken up into segments, half a row at a time.

1a

1a

This is this photo of the next page of the board as it came to me:

(Click any image to enlarge.)____________

Here are the rows of the board broken into two so that I can post them a bit larger.

1a

1a

If only he knew what he was going to face next.

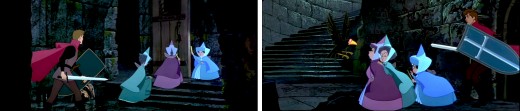

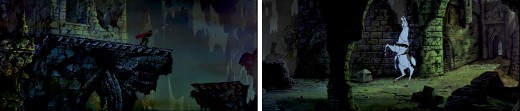

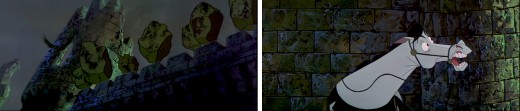

I’ve decided to get the frame grabs for the sequence and post them as well. I thought the comparison of board to actual film would be interesting.

__________

These images come from the “Special Edition” of the dvd, not the “Platinum Edition” now on the market. Using Hans Perk‘s posts of the drafts for these scenes, on his blog A Film LA, I was able to identify the animators’ names.

sc 82 (L) Milt Kahl – sc 82.1 (R) Frank Thomas

sc 82.2 (L) Kahl & Thomas – sc 82.3 (R) George Nicholas & Jerry Hathcock

sc 82.4 (L) Nicholas – sc 82.5 (R) Nicholas & Hathcock

Nicholas & Hathcock (L) sc 82.6

sc 84 (L) Ken Hultgren – sc 85 (R) Nicholas & Hathcock

sc 87 (L) Nicholas & Sibley – sc 88 (R) Nicholas & Hathcock

(L) Nicholas & Hathcock – sc 89.1 (R) Hultgren

sc 89 (L) Nicholas & Hathcock – sc 91 (R) Hathcock

sc 91 (L) Hathcock – sc 92 (R) SA sc 49 seq 8

sc 95 (L) Hathcock – sc 93 (R) Hathcock

sc 96 (L) Hathcock – sc 97 (R) Dan MacManus

(L) MacManus – sc 97.2 (R) Hathcock

sc 98 (L) Hathcock – sc 99 (R) Sibley

sc 100.1 (L) Hathcock – sc 101 (R) Les Clark & Fred Kopietz

sc 102 (L) Hultgren & Kopietz – sc 104 (R) Hathcock

sc 107 (L) Hathcock – sc 108 (R) Hultgren

(L) Hutlgren – sc 109 (R) Hathcock

sc 110 (L) Ollie Johnston & Blaine Gibson – sc 110.1 (R) Gibson

sc 110.2 (L) Johnston – sc 110.3 (R) Johnston & Gibson

sc 110.4 (L) Johnston – sc 111 (R) Johnston & Gibson

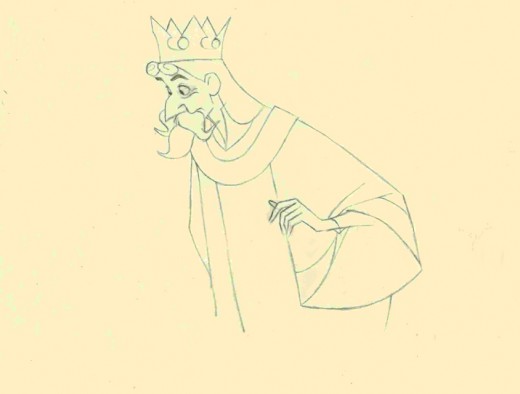

- Let’s end this post from Sleeping Beauty by posting a couple of drawings I have for the “Skumps” sequence. Again, Hans Perk on his blog A Film LA, posted the animator drafts for this sequence and I was able to I.D. the animators. (I have to say I guessed correctly in three out of four shots, so I’m pleased with myself.)

I’m posting closeups of the drawings. By clicking on any of them you’ll see the full sized animation paper. I’m also posting frame grabs beneath the drawings so you can see how they looked in the film.

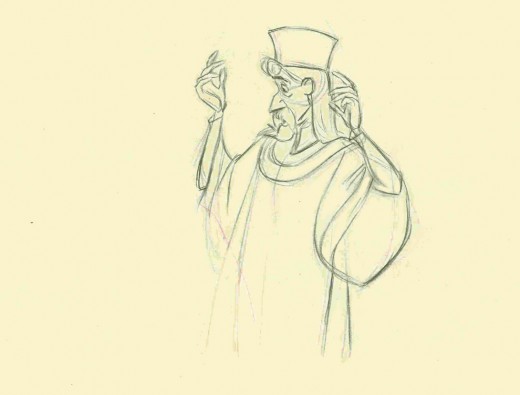

This is a Milt Kahl scene, seq 13 sc 8. This drawing is undoubtedly a clean up,

so it’s not one of Kahl’s drawings – just his pose. It’s an extreme.

It is interesting that Kahl animated both characters.

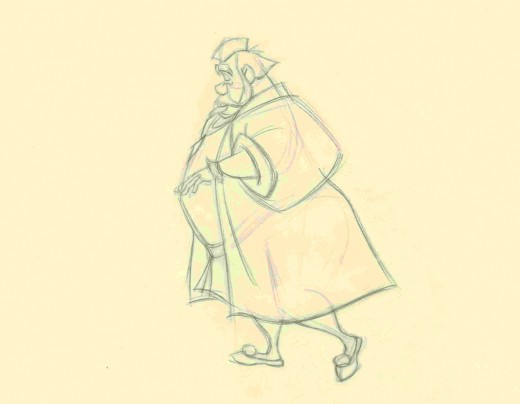

This is a John Sibley ruff. Seq 13 sc 17.

It’s a very odd, uncoordinated dance number by the drunk lackey.

This is my favorite of these four. It’s a John Lounsbery ruff of King Stefan.

Another extreme from seq 13 sc 26.

This is also another beautiful ruff by John Lounsbery. It’s King Hubert in the

very last scene of seq 13, sc 57.

it comes just prior to Hubert’s turning and sitting on the palace steps.

Animation &Animation Artifacts &Articles on Animation &Richard Williams 20 Mar 2013 05:29 am

Dick Williams’ Notes

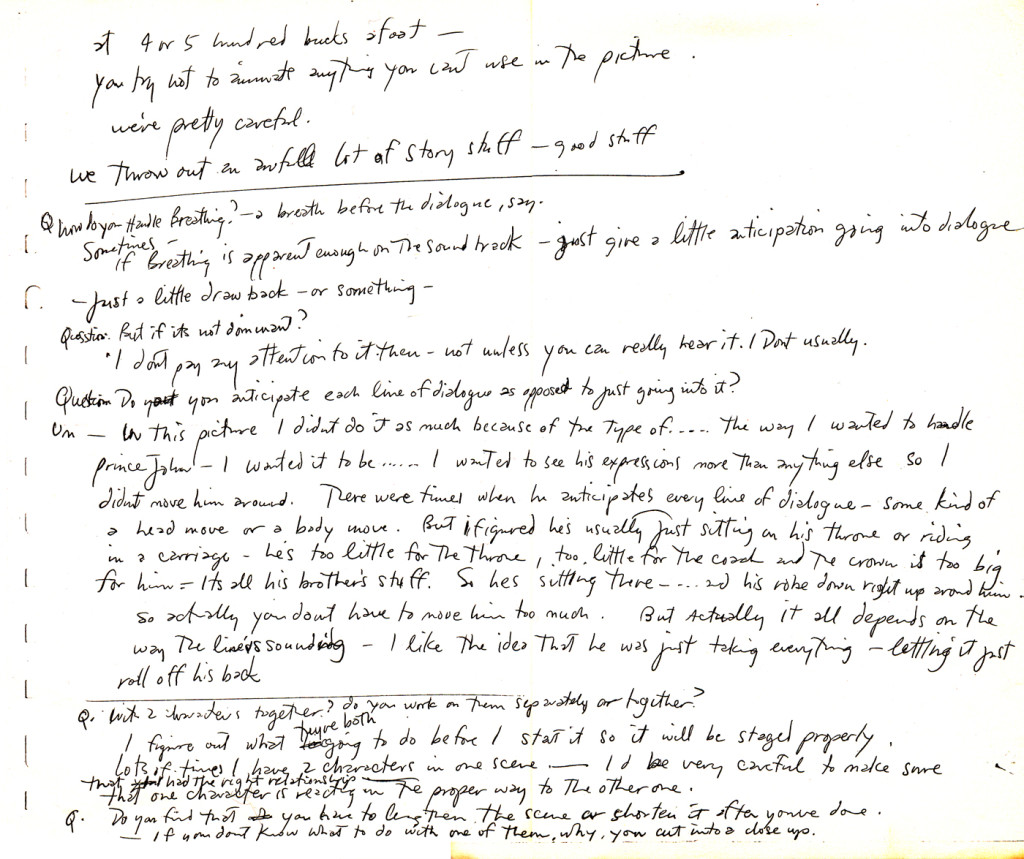

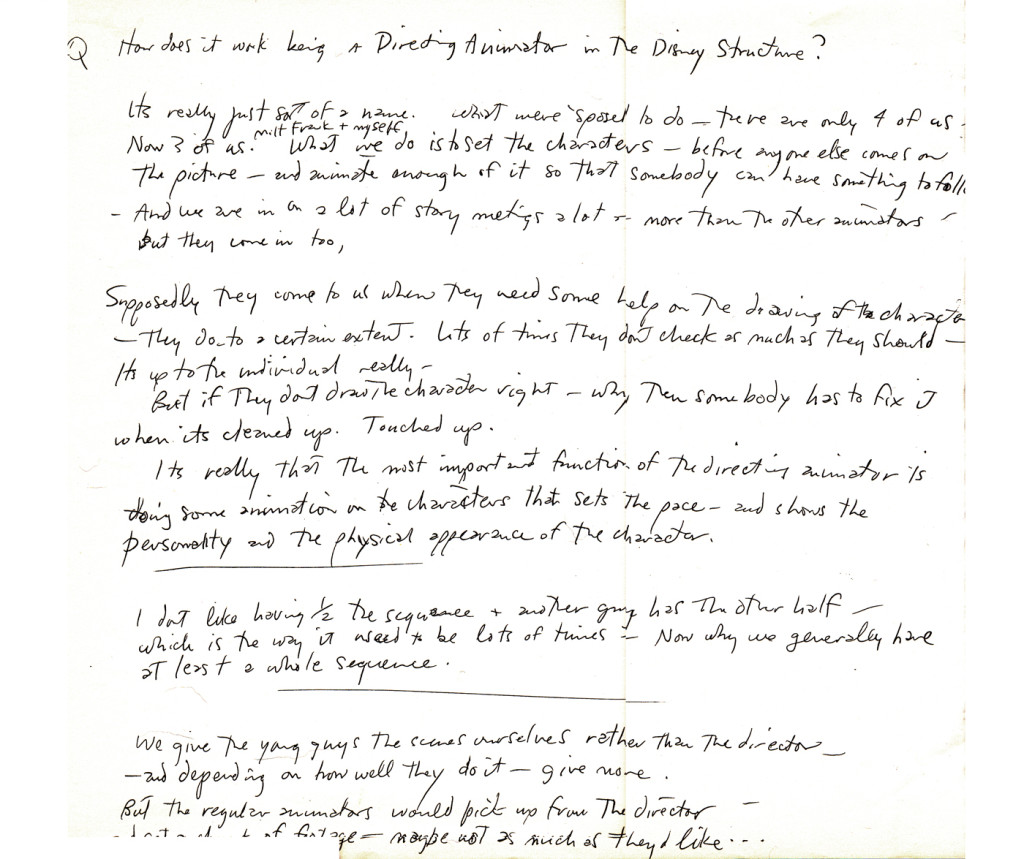

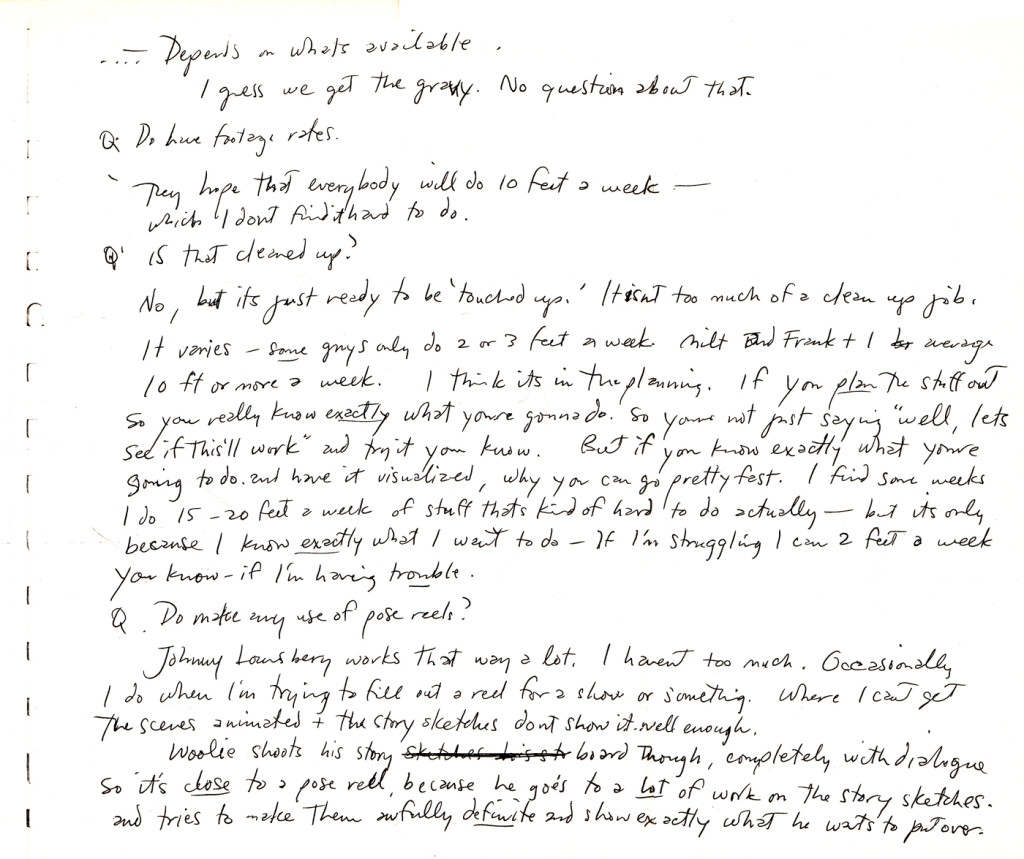

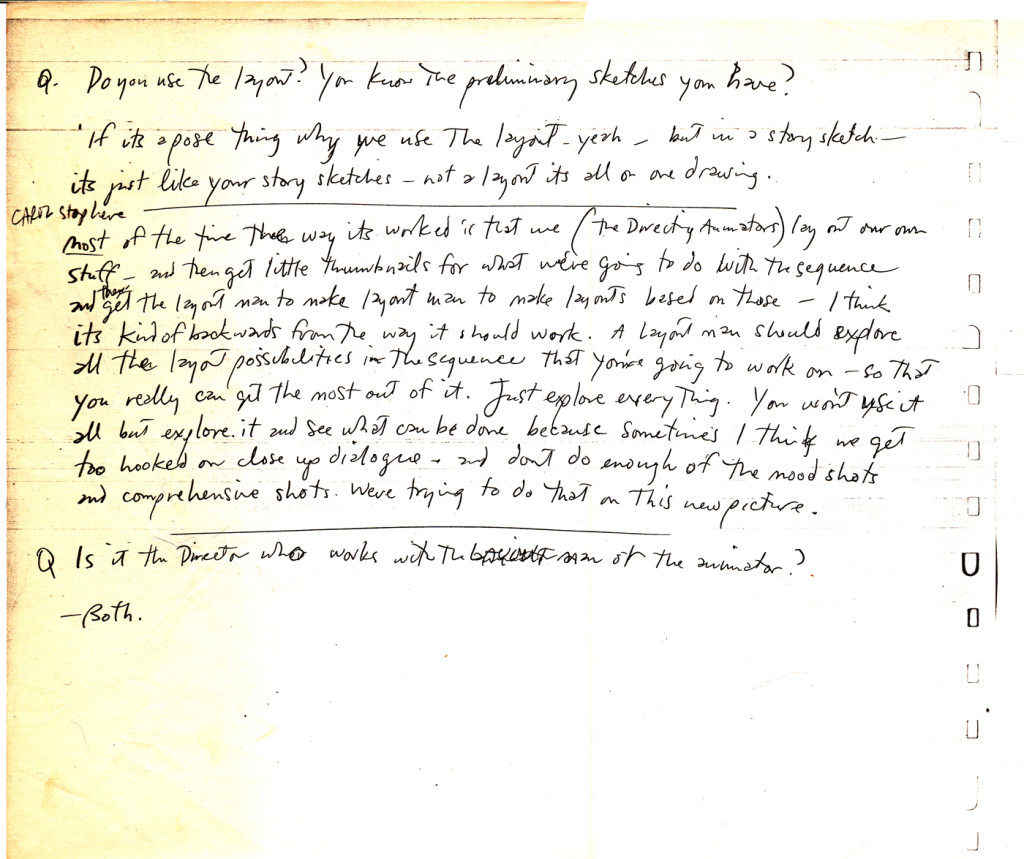

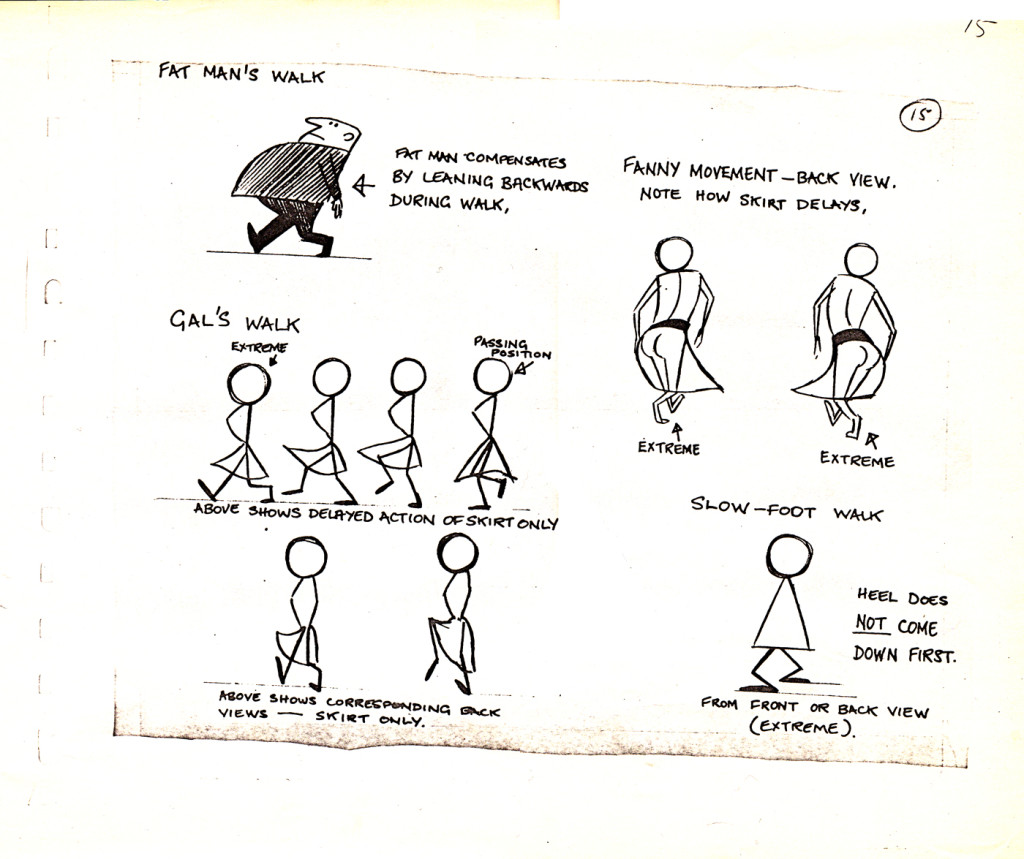

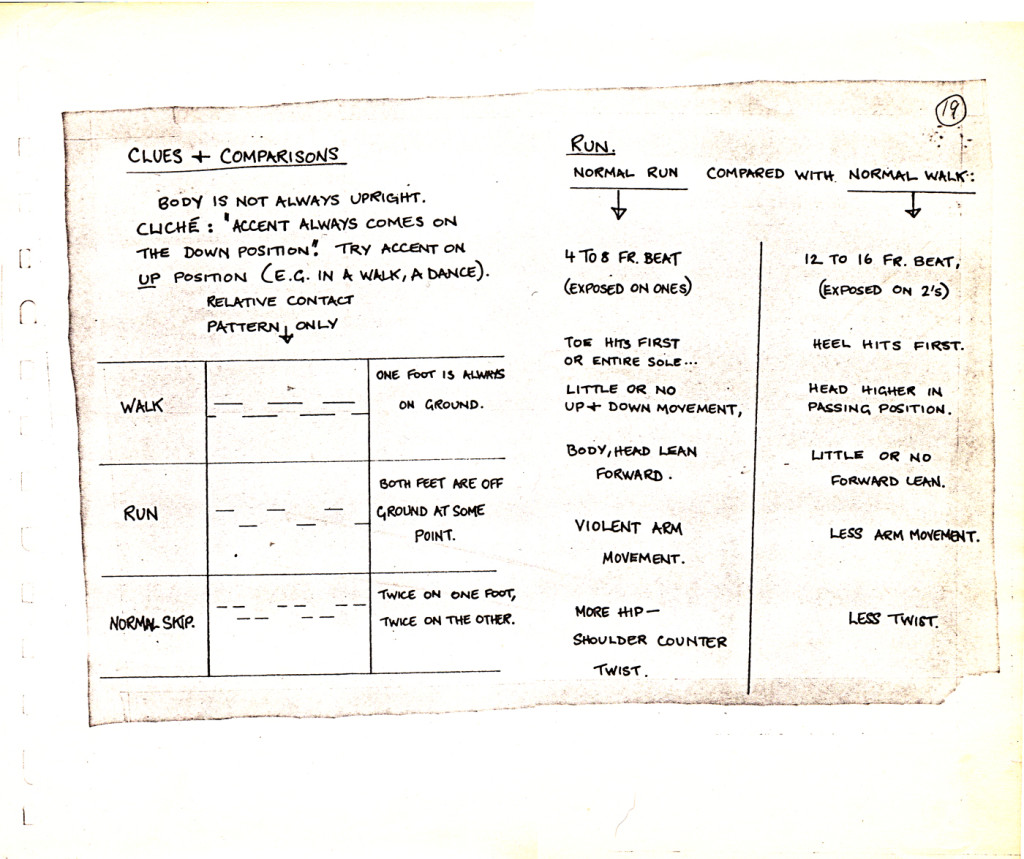

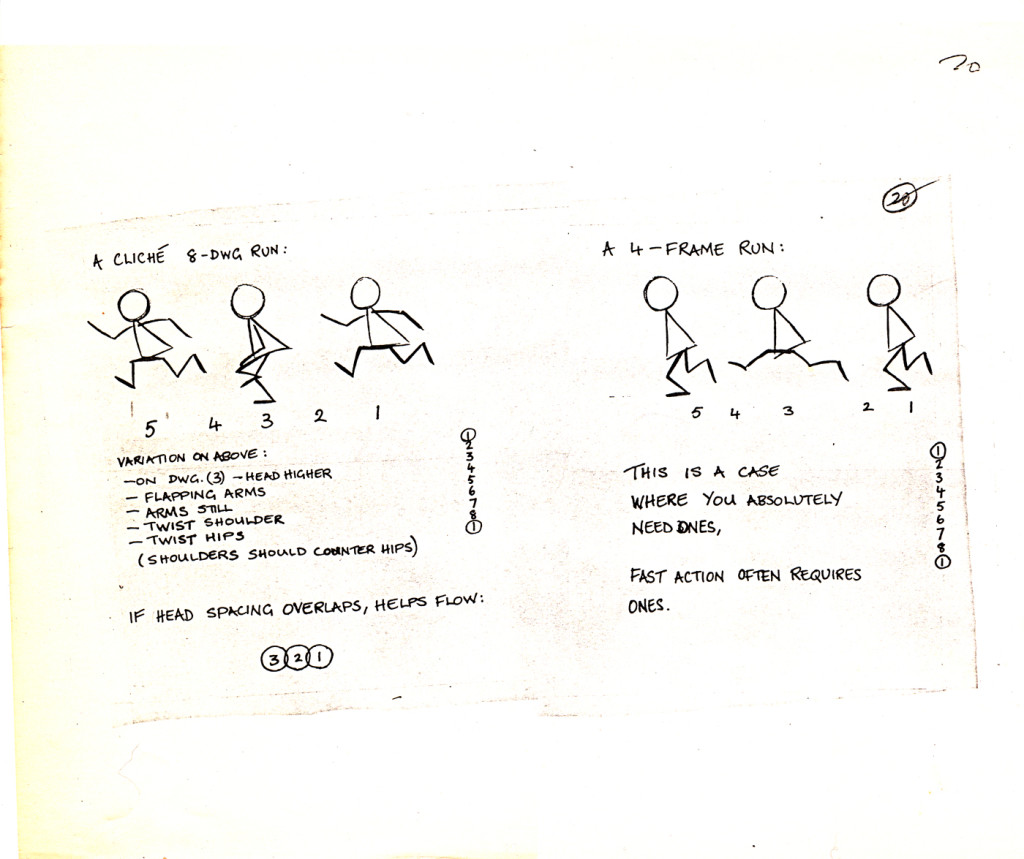

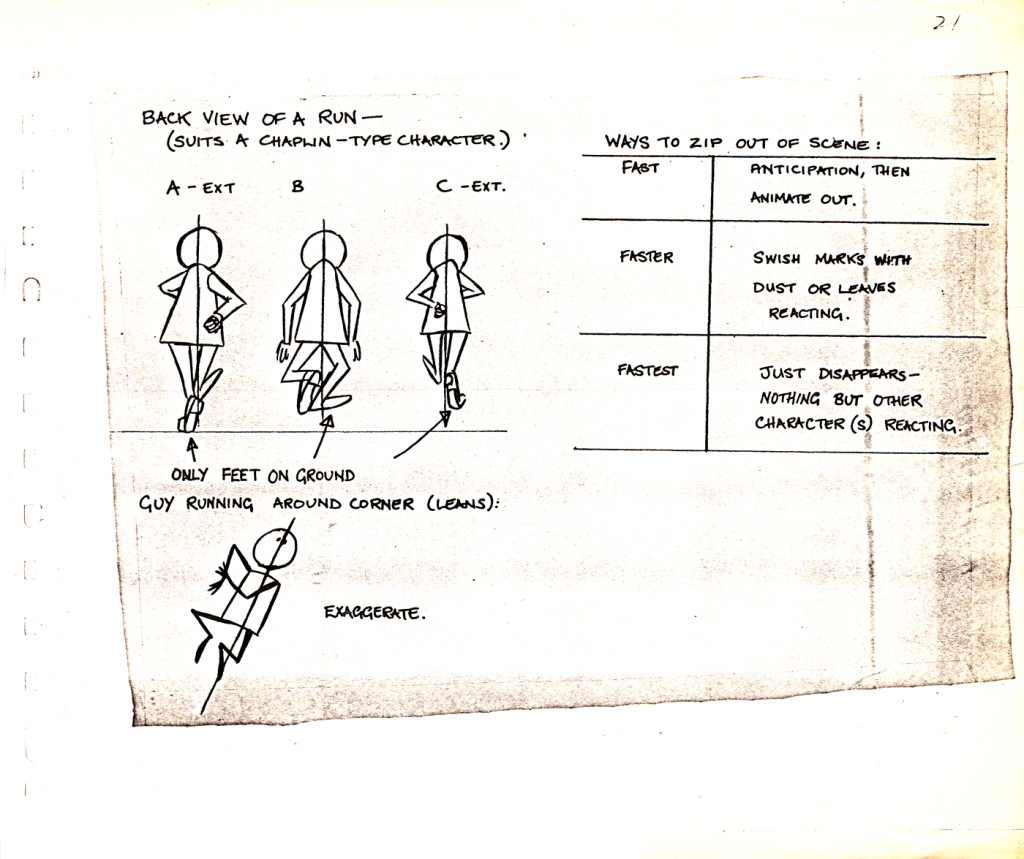

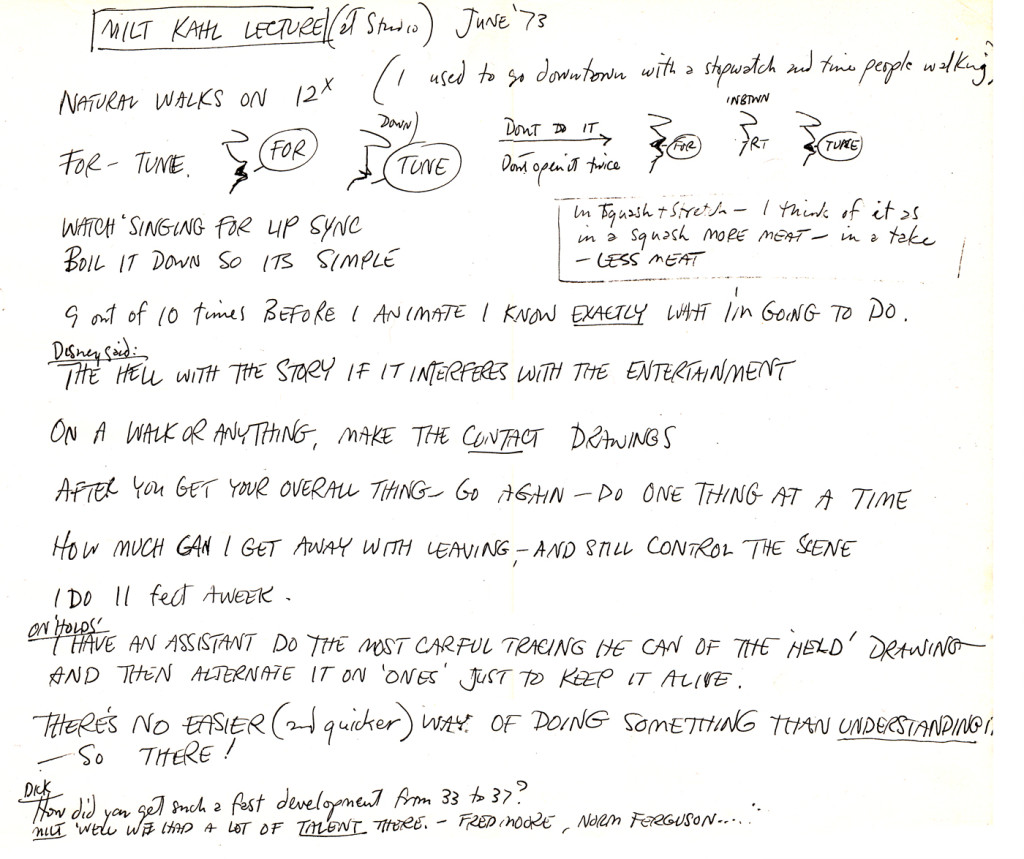

- One of the better pluses of working on Raggedy Ann, back in 1977, was the information available to us. There was circulated, there, a book of notes Richard Williams had kept during the lectures Art Babbitt had given at is studio in Soho Square. These still act as a unique bible I have on my shelf. (Unfortunately, these days it’s on a shelf in storage.)

There was also another set of notes. These weren’t 8½ x 11, they were 14 x 17 sheets of paper, and only a few had access. As one of the bosses there, I had access. (Basically, we couldn’t have everyone copying 14 x 17 sheets of paper; that got expensive.)

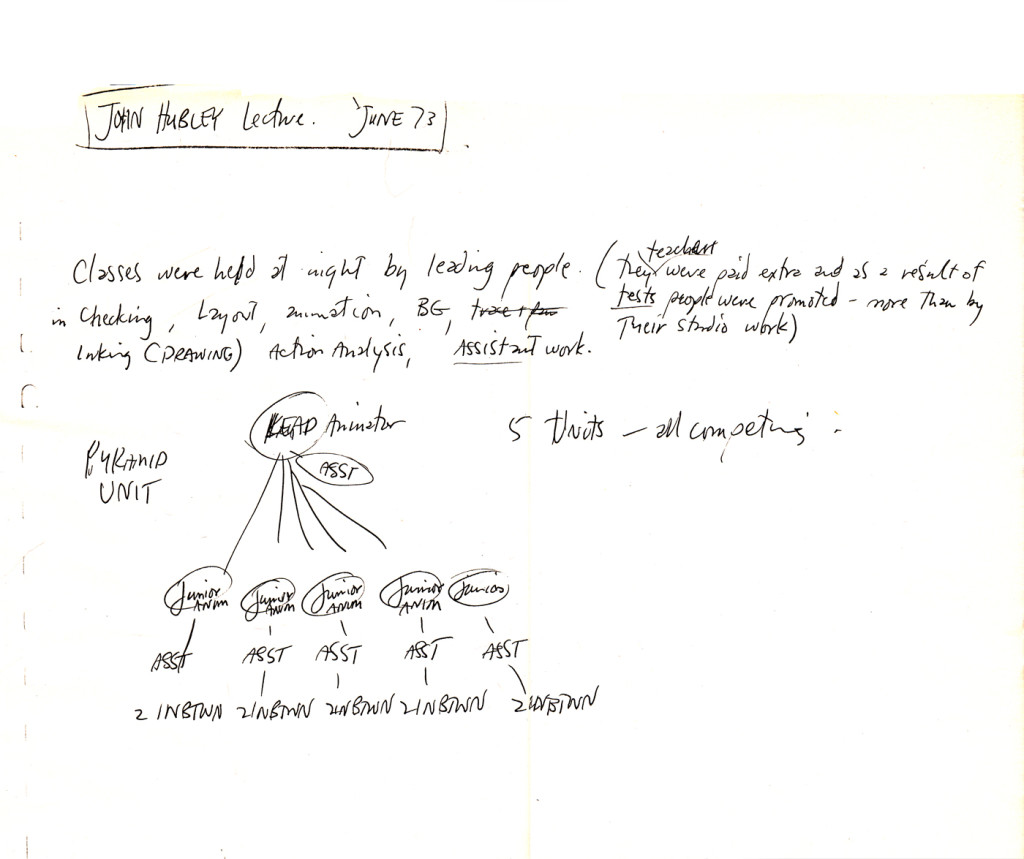

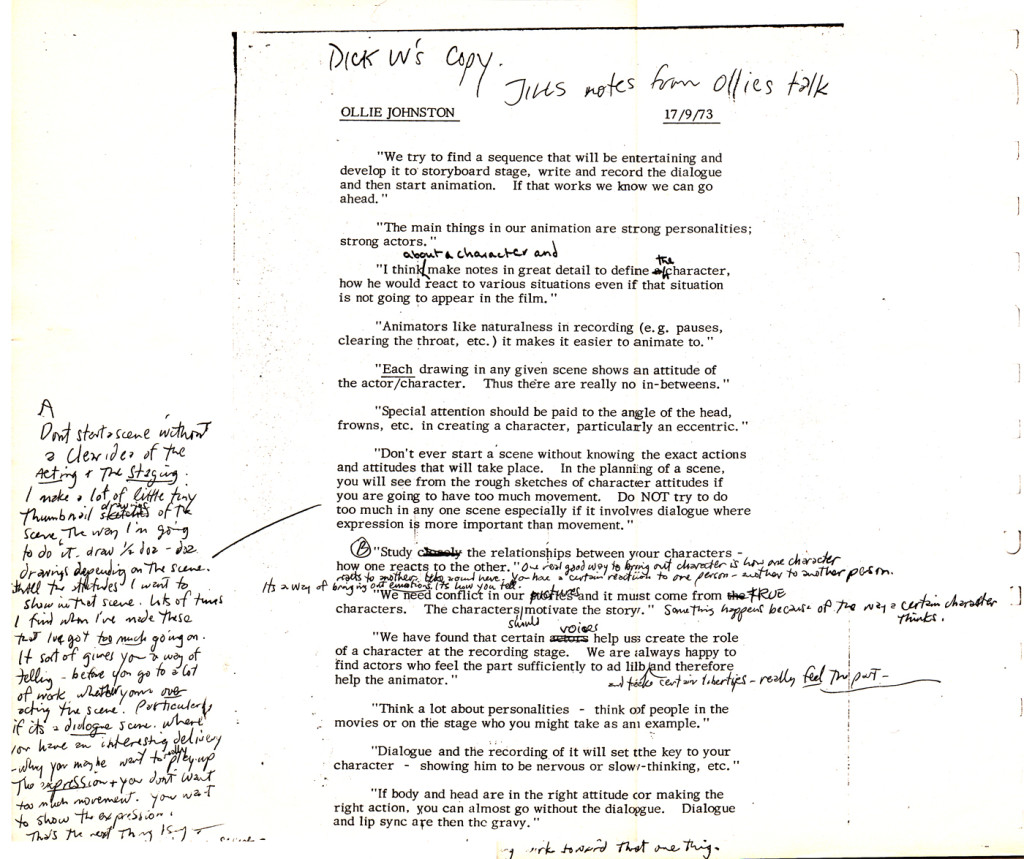

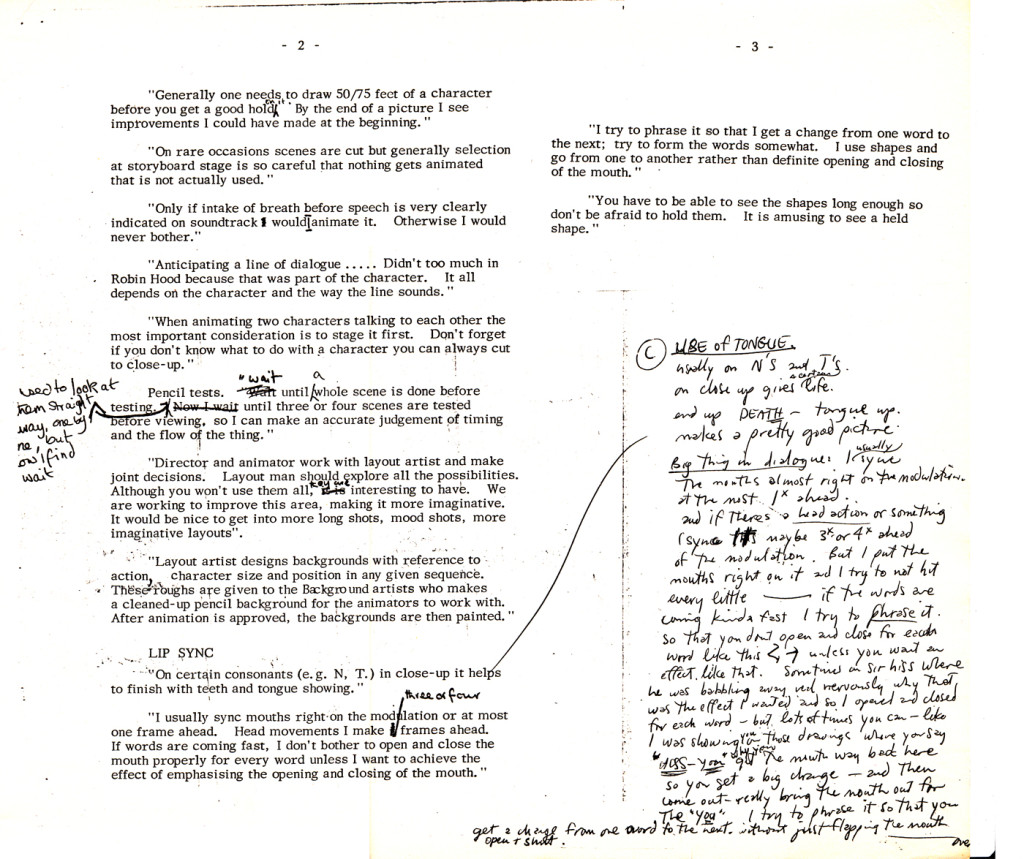

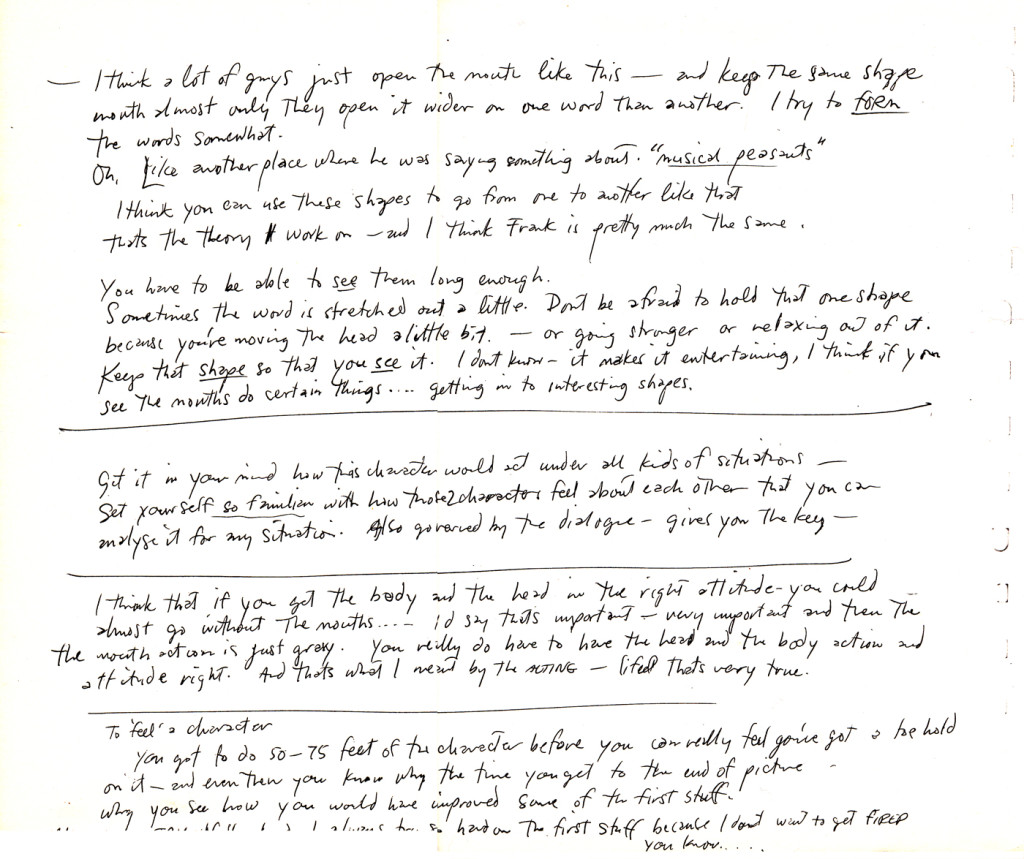

I think these were notes Dick was keeping for a potential book he’d write. They pulled from everywhere, whether it was Preston Blair‘s book or the Disney after-hours studio lecture notes. There were also notes Dick kept from other pros that had given lectures at his studio. Here’s a good sampler of some of these pages. There’s a Milt Kahl talk, a John Hubley talk, notes on an Ollie Johnston talk (typed by Jill, Dick’s assistant as well as notes of different walks from Dick, himself.

I won’t interpret them for you, but will just dump them on you. So here they are. Make sense of them, as you will:

1

1

Articles on Animation &Hubley &Independent Animation 07 Mar 2013 05:24 am

Animation Learns a New Language

This is an article that was published in the July, 1946 issue of The Hollywood Quarterly. I thought some might be interested

by John Hubley & Zachary Schwartz

John Hubley is a director of cartoons at United Productions. He has worked as art director and director of Disney Studios, at Columbia, and in the First Motion Picture Unit of the Army Air Forces.

.

.

.

Zachary Schwartz was one of three organizers of United Productions, where he is now a director. He has worked on Disney productions and on wartime training films. He is now preparing a training film for State Department personnel.

.

.

Select any two animals, grind together, and stir into a plot. Add pratfalls, head and body blows, and slide whistle effects to taste. Garnish with Brooklyn accents. Slice into 600-foot lengths and release.

This was the standard recipe for the animated cartoon. That is, it was standard until Hollywood’s fantasy makers were presented the task of teaching people how to fight.

Six months before America entered World War II, the animated motion picture industry of Hollywood was engaged in the production of the following films:

- 1 Feature-length cartoon about a deer

16 Short subjects about a duck

12 Short subjects about rabbits

7 Short subjects of a cat chasing a mouse

5 Short subjects with pigs

3 Short subjects with a demented woodpecker

10 Short subjects with assorted animals

1 Short technical subject on the process of flush riveting.

Since that time, the lone educational short, dubbed by the industry a “nuts and bolts” film, has been augmented by hundreds of thousands of feet of animated educational film. Because of wartime necessity, pigs and bunnies have collided with nuts and bolts.

Sudden change from peace to war presented to government agencies, the military services, and industrial organizations a fundamental problem. This was the necessity of teaching millions of people an understanding of objective information with which they were essentially unfamiliar. The thinking and mechanical skills of millions had either to be changed or developed. And fast. Thinking, that is, and understanding regarding international policies, the nature of the enemy, coöperative safety measures, the fight against disease, price control, taxes, motor skills involving the thousands of tactical details of warfare for fighting men, and the hundreds of new methods for unskilled workers.

Thus it also became necessary for the craftsman-animators of the motion picture industry to analyze and reëvaluate their medium; for visual education, or more specifically the motion picture, bore the burden of this tremendous orientation program. Previously, animation usage in the educational film had been singularly undeveloped. While the theatrical cartoon developed an ability to emphasize and exaggerate for comedy purposes, and perfected the techniques of dramatization, “nuts and bolts” animation remained static. It consisted of rigid charts, diagrams, mechanical operations, maps, and labels. Unlike its Hollywood counterpart, it contained no humor, no personalized or intensified image, no emotional impact, no imaginative association of ideas to enable one to retain its content.

It presented cold facts, and left its audiences in the same state. But because of the urgency of the war situation; because of the varied specialized groups to be taught; because of the attitudes to be formed or converted, new and more effective means were necessary. The collision of these two animation methods occurred because of the need to present objective information in human terms.

Film units in the Armed Forces, and many professional studios producing educational films of infinitely varied subjects, soon discovered that, within the medium of film, animation provided the only means of portraying many complex aspects of a complex society. Through animated drawings artists were able to visualize areas of life and thought which photography was incapable of showing.

Psychological tests and reaction studies conducted by the military indicate an exceptional popularity and response to animated technical and orientation films. The Signal Corps found that the reaction to the animated “Snafu series” was greater than the reaction to any of the live-action films. The Air Forces Psychological Test Film Unit undertook a study of how much was learned through use of an animated training film as compared with how much through oral and written instruction on the same subject matter. The superiority of the film, both for learning and retention, was particularly clear when full use was made of the unique possibilities inherent in the medium.[1]

What are these unique factors? To understand them we must examine the basic difference between animation and photographed action. Now a single drawing, especially the cartoon, has always been capable of expressing a great many ideas. A drawing of a man, for instance, can glorify him or ridicule him. Further, it can emphasize aspects of his physical form and subdue or eliminate others. It can combine ideas, such as a human face on a locomotive, an animal in a tuxedo, a skeleton with a cloak and scythe, etc. It can represent a specific object (a portrait, a landscape, a still life). Or it can represent a symbol of all men, all trees; the drawing of Uncle Sam representing America; the eye representing sight; the skull representing death: the single image can represent the general idea. The part can be interpreted as a symbol for the whole.

Thus a drawing’s range of expression, its area of vision, is wider than that of the photograph, since the camera records but a particular aspect of reality in a single perspective from a fixed position. In short, while the film records what we see, the drawing can record also what we know. The photograph records a specific object; the drawing represents an object, specific or general.

Animated drawings are a series of single images drawn in the progressive stages of a motion, which, when photographed on film and projected, create a visual symbol of that motion. In this lies the significant element that creates the possibility of a new visual language.

Our general idea, our broadest observations of reality, can be visualized in terms of the personal emotional appeal of the specific idea. What does this mean in terms of the communication of ideas? It means that the mental process which the individual scientist has undergone to achieve a greater understanding of nature can now be visualized for millions of people.

For example, a scientist deduces that by grafting two plants a seed is produced that will bring forth a new type of plant. He then proves his deduction by experimentation and comparison. We can see the result. We can see the original plants; we can see the seed. But we only understand the process by means of a language whereby the scientist explains the development to us. He may use words, and is thereby limited to audio images. Or he may photograph the specific parts of his experiment in motion pictures and, by assembling the parts in conjunction with words, produce a segmentary progression of the process. Or, by using stop action or other camera devices, he may photograph the growing plant itself.

But were he to translate the process into animation, he could represent, by means of the dynamic graphic symbol, the entire process, each stage or degree of development; the entire growth, from the grafting, through the semination of the seed, to the resultant plant. This quality of compression, of continuous change in terms of visual images, supplies the scientist with a simple language and a means of representing his own process of observation to millions.

Since the artist controls the image of a drawing, he also has the ability to change its shape or form. He is able to change a tree to a stone, an egg to a chicken, in one continuous movement. And he can compress a process that would by nature take centuries, or days, into minutes, or seconds. Or he may extend a rapid movement, such as the release of atomic energy, from split seconds to minutes, that it may be more carefully observed. These aspects of natural movement, and simultaneous confiicts of opposite movements, such as physical action and reaction, positive and negative electricity, processes we know, we can now see.

We must be clear that the effectiveness of live-action photography is by no means reduced by animation. It is only necessary to understand photography’s functions and capabilities in relation to animation. This may be stated as an ability to represent a specific aspect of reality in very real terms. We can photograph reality. Or we can create a synthesis of reality, and record it.

For instance, we may see the subtle shades of expression on the face of a resistance leader before a fascist firing squad. This may be actual (documentary) or enacted. We see his bodily aspect, his clothes, his hands, the barren wall behind him, the distance between the man and the guns, the sky, the trembling, the blood. Dramatically, we are made to feel the relationship between the victim and the firing squad, the emotional conflict, the tension, the fear, the hatred. We can understand these emotions because we have experienced similar emotions. The specific situation is the focal point that gives us the clue to the general situation. We see this victim of fascism shot, and we gain a better understanding of the general nature of fascism.

With animation, this process is reversed. Instead of an implied understanding resulting from the vicarious experience of a specific situation, animation represents the general idea directly. The audience experiences an understanding of the whole situation.

Dynamic symbols, images representing whole ideas, the flags, the skulls, the cartoon characters, can explain the nature of fascism in terms of its economic roots, the forces behind it, the necessity for its policies of aggression, its historical roots, its political structure. The dynamics of changing symbols—ballots turning into guns, books to poison, plowshares to swords, children changing to soldiers, soldiers to graves—can carry a visual potency as clear as the growth of a seed into a plant. Our understanding of the process as a whole is experienced directly and immediately.

The significance of the animated film as a means of communication is best realized in terms of its flexibility and scope of expression. It places no limitations upon ideas; the graphic representation grows out of the idea. The broadest abstract theory may be treated in a factual manner and made interesting, clear, and memorable through the use of movement and sound. All degrees of the general and particular are within its normal scope because anything that the brain can conceive can be expressed through the symbol. For instance, the subject might demand an extremely impressive statement of reality. It might then be advisable to use a combination of photography and animation, the photography to state the facts of outward appearance and the animation to illustrate the inner construction, or comments upon the subject, or to suggest emotional reactions of the subject. This kind of treatment creates a super-reality in which we are conscious of many aspects simultaneously.

In animation, the artist and writer have at their command all the traditional means of graphic expression and the new means which grew out of moving symbols and sound. One of these is the concept of explanation through change from an object as it is to the thing it signifies. For instance, in explaining the function of the liver the picture changes from a liver to a recognizable sugar bowl filled with cubes of sugar. The cubes hop out into the blood stream and bob away into the circulatory system. Or, we might wish to give graphic expression to an emotional reaction. One person is being protected by another, and for a moment the protector animates up into a proud knight and charger. We hear the clank of metal and stamp of horse’s hoofs for just an instant, and then the whole image animates down again into its original form. Another example of this is the picturization of certain words in dialogue to stress a particular idea. A person is being taught a difficult mechanical technique involving rapid manipulation of buttons and levers, etc. He protests, “What do you think I am—an octopus?” At the moment the word is spoken the character changes to an octopus and then back again so quickly that the observer has just gotten a fleeting impression of the picture of the word. These examples indicate the kind of picture solution that can be evolved from an idea no matter how abstract.

We have found that the medium of animation has become a new language. It is no longer the vaudeville world of pigs and bunnies. Nor is it the mechanical diagram, the photographed charts of the old “training film.” It has encompassed the whole field of visual images, including the photograph. We have found that line, shape, color, and symbols in movement can represent the essence of an idea, can express it humorously, with force, with clarity. The method is only dependent upon the idea to be expressed. And a suitable form can be found for any idea.

Articles on Animation &Books 04 Mar 2013 05:49 am

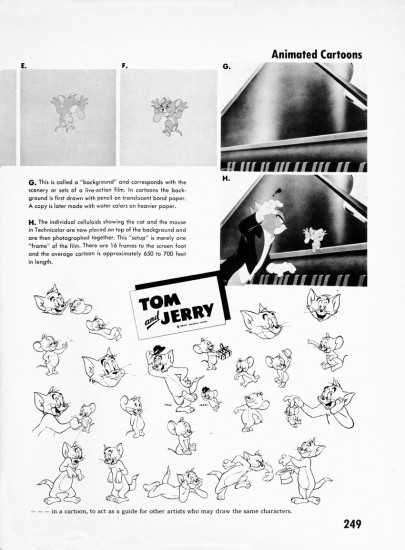

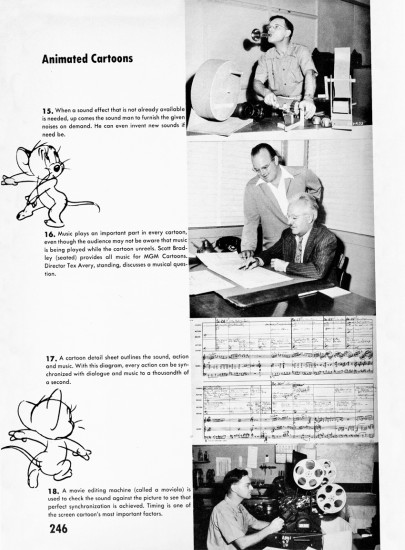

The MGM Cartoon Studio

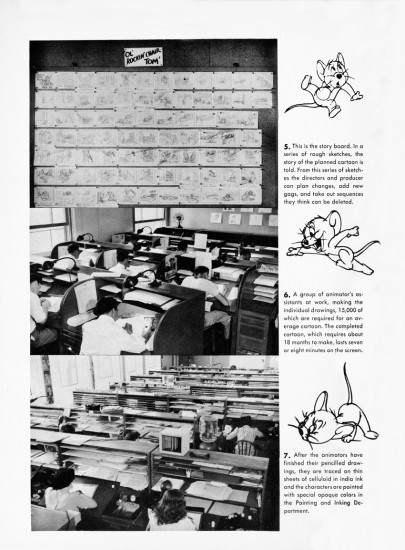

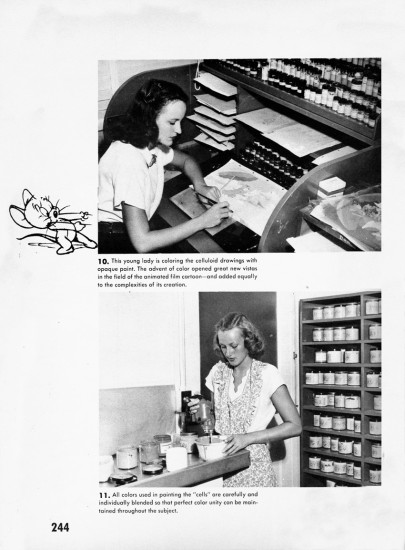

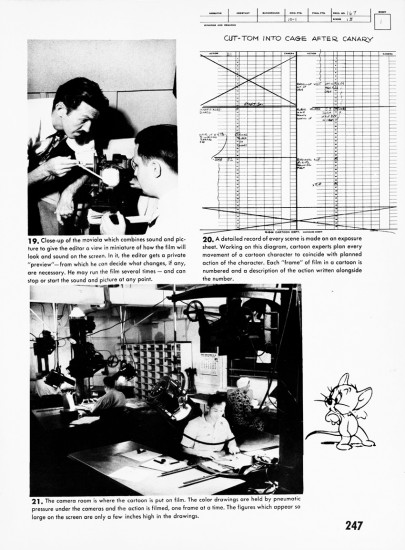

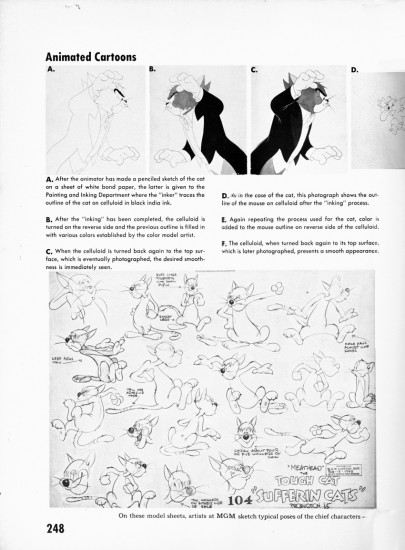

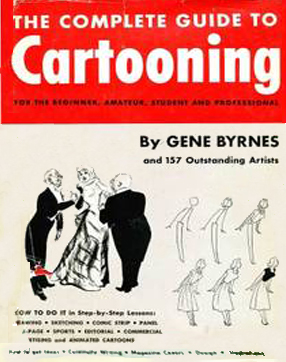

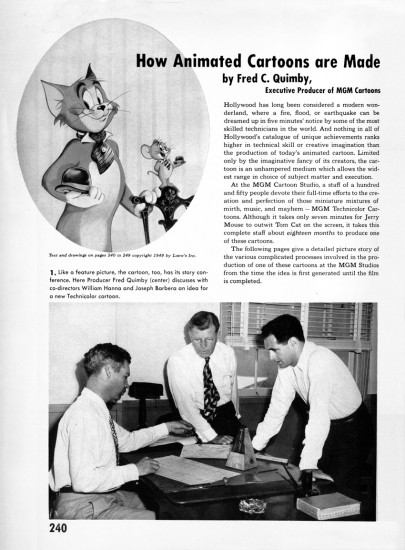

- When I was a kid the only animation books available were few and far between. Fortunately, I lived near a local library that stocked many of these books (6-10 of them, including the great book by R.D. Feild, Art of Walt Disney). One that I loved was this book by Gene Byrnes, The Complete Guide to Cartooning. It had a full chapter on the MGM cartoon studios and credits Fred Quimby as writer of the chapter. The book was a strong inspiration for me when back then, and it still sends a chill up my back and gets me wanting to animate when I look at a couple of those images.

- When I was a kid the only animation books available were few and far between. Fortunately, I lived near a local library that stocked many of these books (6-10 of them, including the great book by R.D. Feild, Art of Walt Disney). One that I loved was this book by Gene Byrnes, The Complete Guide to Cartooning. It had a full chapter on the MGM cartoon studios and credits Fred Quimby as writer of the chapter. The book was a strong inspiration for me when back then, and it still sends a chill up my back and gets me wanting to animate when I look at a couple of those images.

The cartoon Cat Concerto is featured. Obviously the studio was pushing it for the Oscar, and a bit of publicity, appearing in this book, didn’t hurt. It did win the Oscar. The other five nominees included:

- Musical Moments from Chopin (Lantz, Dick Lundy dir)

Walky Talky Hawky (WB, Rob’t McKimson dir)

Squatter’s Rights (Disney, Jack Hannah dir)

John Henry and Inky-Poo (Par, Georg Pal)

3 cartoons featuring classical piano performances by the star cartoons character. Very interesting. This is the subject of the debate on-going at several sites.

Thad Komorowski brought up the controversy and discusses it n full. The debate of whether one short ripped off another actually started back in 1946.

Michael Barrier discusses the discussion adding some information.

Jerry Beck offers some historic material. just now. Watch the cartoon on Thad’s site.

If you recognize anyone in the photos and can identify anyone , please leave a comment.

1

1(Click any image to enlarge.)

Bill Hanna and Joe Barbera are on opposite sides of the table.

Producer, Fred Quimby is in the middle.

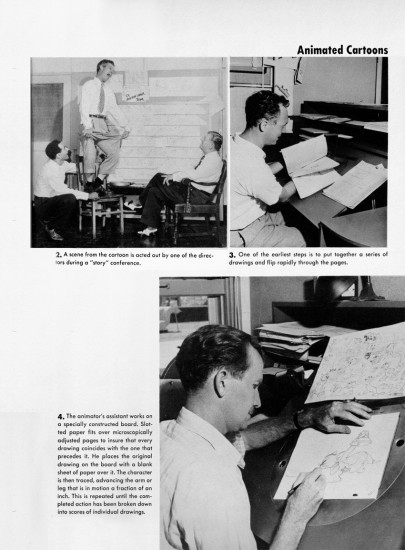

2

2

#3 Upper right: Preston Blair / #4 Bottom: Asst Animator Tom McDonald

4

4

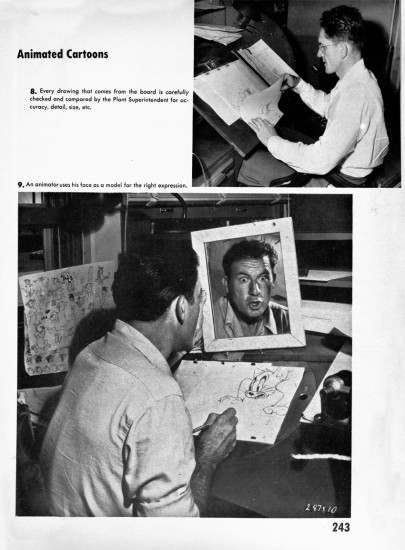

#8 Upper: Max Maxwell head of checking / #9 Bottom: Irv Spence, animator

6

6

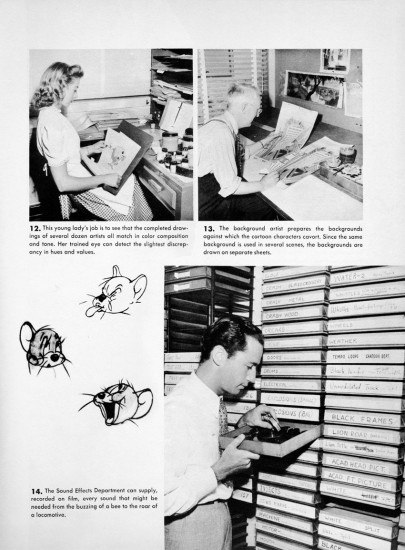

#13 is Johnny Johnson, BG painter

7

7

#16 Middle: (standing) Tex Avery with (seated> composer Scott Bradley

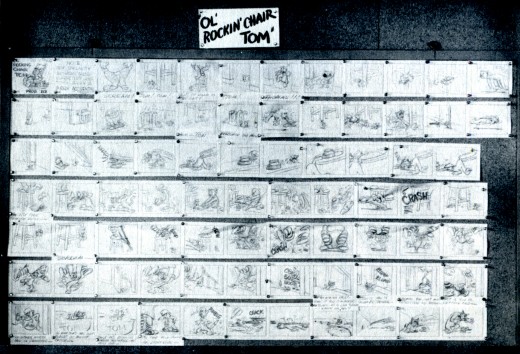

I’m enlarging the photo of the storyboard. Without the benday pattern and at a higher res, it’s a little easier to read blown up.

This book also includes some pretty great (non-animation) cartoonists. I still remember every page from my childhood when I borrowed this book countless times from my local public library.