Search ResultsFor "bambi"

Animation &Books &Disney &repeated posts 11 Jun 2013 03:42 am

Retta Scott and Cinderella – repost

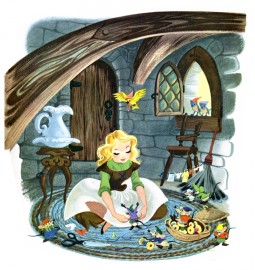

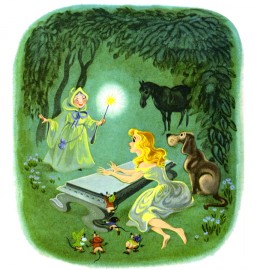

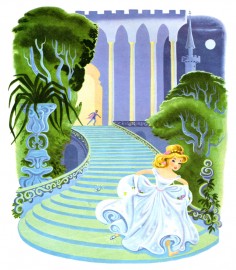

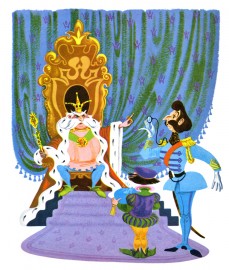

– Retta Scott‘s name was always an intriguing one for me.

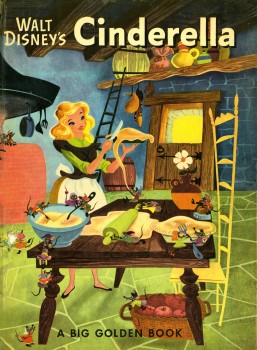

She was an animator on Bambi, Dumbo and Plague Dogs. She was layed off at Disney’s when they hit a slump in 1941 but came back to do a number of Little Golden Books for Disney. The most famous of her books was her version of Cinderella, one which was so successful that it remains in print today as a big Little Golden Book.

She was an animator on Bambi, Dumbo and Plague Dogs. She was layed off at Disney’s when they hit a slump in 1941 but came back to do a number of Little Golden Books for Disney. The most famous of her books was her version of Cinderella, one which was so successful that it remains in print today as a big Little Golden Book.

When asked why females weren’t animators at the studio, the Nine Old Men who traveled the circuit, back in the 1970′s, often mentioned her. They usually also said that she was one of the

.

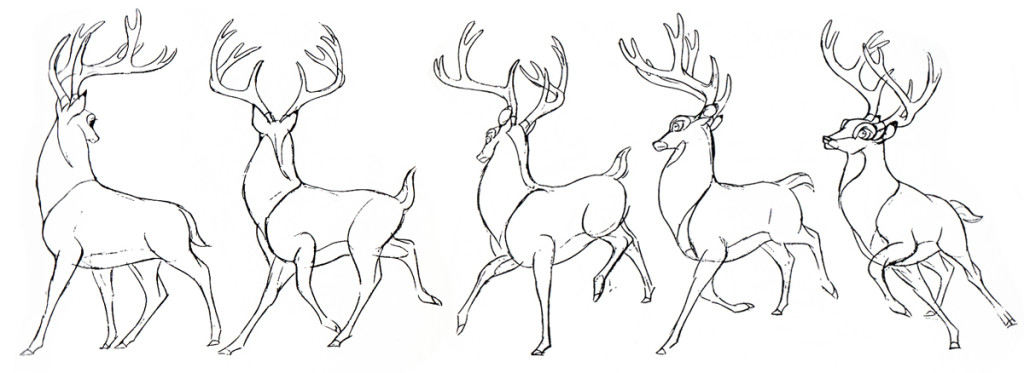

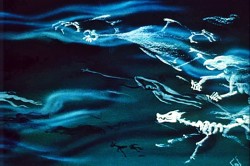

most forceful artists at the studio, but her timing always needed some help (meaning from a man.) Ms. Scott was known predominantly for her animation in Bambi. Specifically, she’s credited with the sequence where the hunter’s dogs chase Faline to the cliff wall and Bambi is forced to fight them off.

The scene is beautifully staged and, indeed, is forceful in its violent, yet smooth, movement. I was a young student of animation, so this sequence had a long and lasting impression on me.

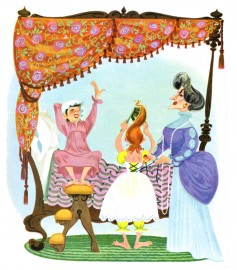

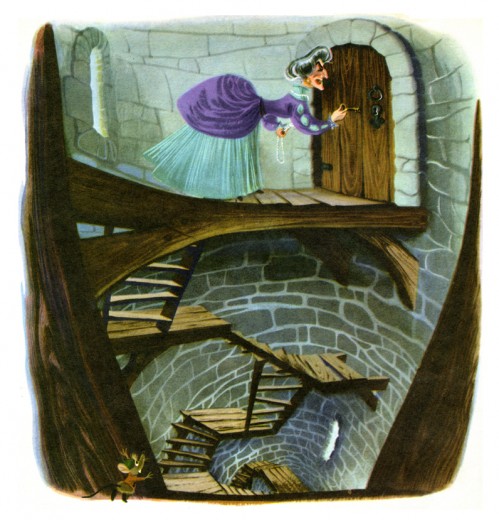

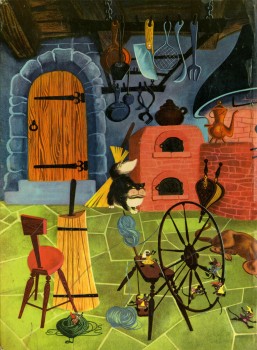

Here are some of her illustrations for Cinderella published in 1950 to tie in with the Disney film. Oddly, the illustrations don’t completely look like the film’s characters. The cat and mice are close, but Cinderella, herself, is very different, less realistic. She looks more like a Mary Blair creation. When I was young, I was convinced that these were preproduction illustrations done for the film. If only.

I won’t post all the illustrations of the book; I want to give an indication of her work, and I think this should be enough to do that.

(Click any image to enlarge.)

Action Analysis &Animation &Articles on Animation &Books &Commentary &Disney &Illustration &Richard Williams &Rowland B. Wilson &SpornFilms &Story & Storyboards &Tissa David 10 Jun 2013 03:31 am

Illusions – 3

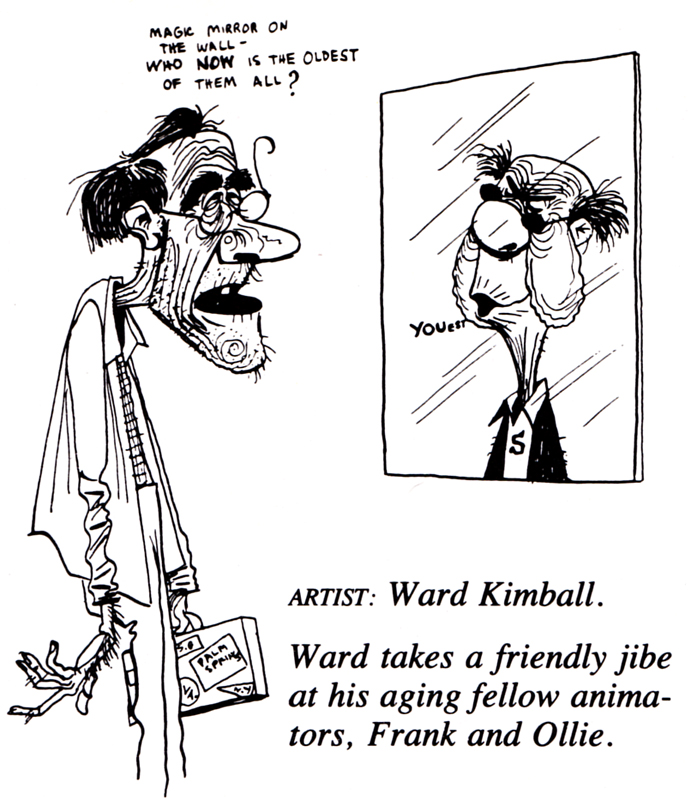

I’ve written two posts about Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston‘s book, The Illusion of Life the last couple of weeks. I came to the book only recently and realizing that I’d never really read the book, I thought it was time. So in doing so, I’ve found that I have a lot to write about. The book has come to be accepted almost as gospel, and I decided to give my thoughts.

There were two major complaints I’ve had with what I’ve read in their book so far, and I spent quite a bit of time reviewing those.

- First out of the box, I was stunned to read that these two of Disney’s “nine old men” said that they’d originally believed that each prime animator should control one, maybe two characters in the film. Then, later in life they decided that an animator should do an entire scene with all of the characters within it. This is not what I’d seen the two (or the nine) do in actual practice. post 1

Secondly, they argue for animating in a rough format, and they give solid reasons for this. As a matter of fact, it was Disney, himself, in the Thirties who demanded the animators work rough and solid assistants who could draw well back them up. Then much later in the book the two author/animators suggest that it’s better for an animator to work as clean as possible with assistants just doing touch-up. This helped out the Xerox process, but didn’t necessarily help for good animation. post 2

The book starts out sounding like it’s going to be a history of Disney animation, but then starts getting into the rules of animation (squash and stretch, overlapping action and anticipation and all those other goodies) exploiting Disney animation art in demonstration. Soon the book moved into storytelling and how to try to keep the material fresh and interesting. It all becomes a bit obvious, but you keep hoping that some great secret will be revealed by the two masterful oldsters.

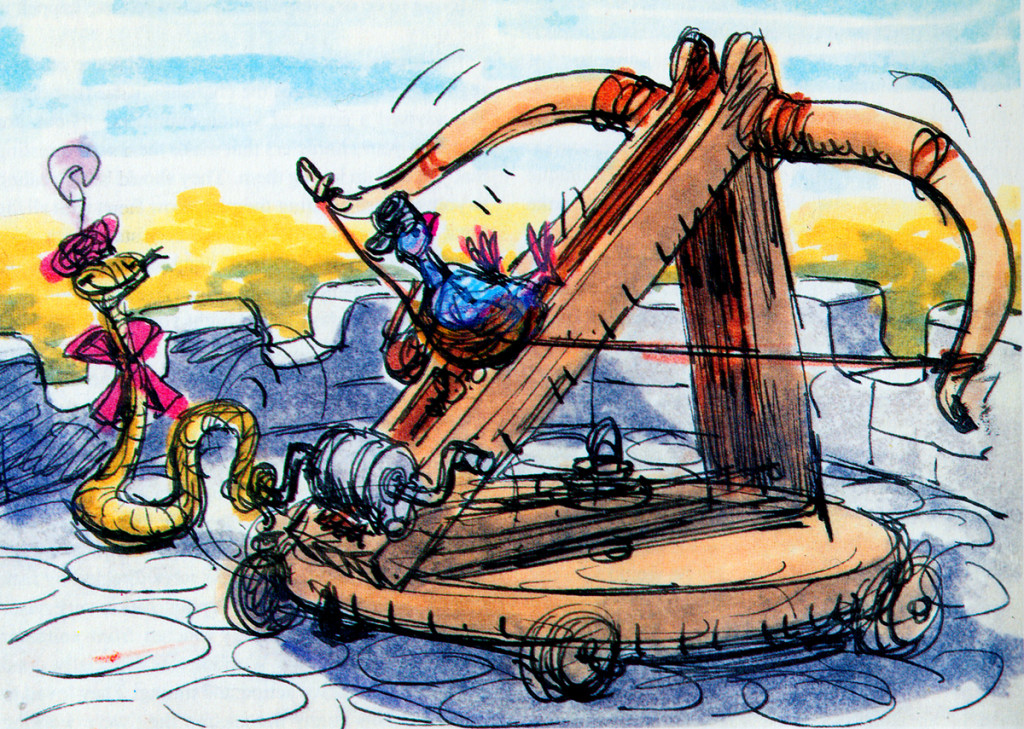

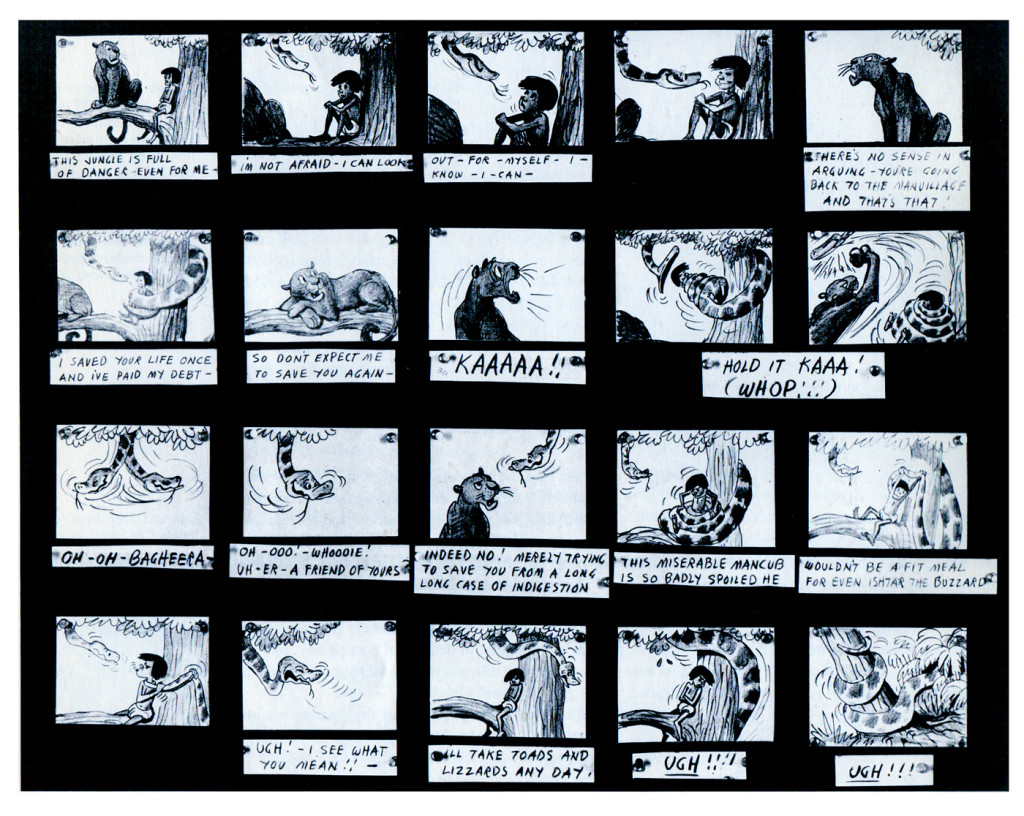

They do go into depth about how to develop characters when making animated films. They offer lots of examples from Orville, the albatross in The Rescuers to the three fairies in Sleeping Beauty, but their greatest attention goes to Baloo the Bear in The Jungle Book. They were having a hard time with this guy; they had been trying to do an Ed Wynn type character, until Walt Disney, himself, suggested Phil Harris. Once they auditioned Harris, they knew they were on the right track, and the character kept grabbing more screen time and grew ever larger. In the end, audiences just loved him.

They do go into depth about how to develop characters when making animated films. They offer lots of examples from Orville, the albatross in The Rescuers to the three fairies in Sleeping Beauty, but their greatest attention goes to Baloo the Bear in The Jungle Book. They were having a hard time with this guy; they had been trying to do an Ed Wynn type character, until Walt Disney, himself, suggested Phil Harris. Once they auditioned Harris, they knew they were on the right track, and the character kept grabbing more screen time and grew ever larger. In the end, audiences just loved him.

Personally, I’ve always hated Phil Harris’ performance in this film. What was it doing in Rudyard Kipling’s book? When I was a kid, Harris and Louis Prima were the perfect examples of my father’s entertainers. He loved these guys and spent a lot of time in front of the family TV watching the Dinah Shore Show______Tom Oreb designs for Sleeping Beauty.

and other such entertaining Variety Shows with

lots of little 50′s big-band jazz-type acts. I hated it; this was my parent’s kind of music and humor and had nothing to do with me. I was the kid who paid his quarter to see the Walt Disney movies (that was the children’s price of admission in 1959.)

In their book they say they knew he was perfect because generations of kids later (who have no idea who Phil Harris was) still take joy from Baloo. What they forgot is what I knew all along. This was The Jungle Book. If they had been truly creative, they would have developed a character in line with Kipling’s material that would have been an original, not an impersonation of Doobey Doobey Doo, Phil Harris. The same is true of Louis Prima as a monkey. (There was a time when Disney said that they should never animate monkeys because monkeys are funny on their own, in real life. Animation wouldn’t make them funnier.) Sebastian Cabot, as Bagheera, works as does George Sanders as Shere Khan.

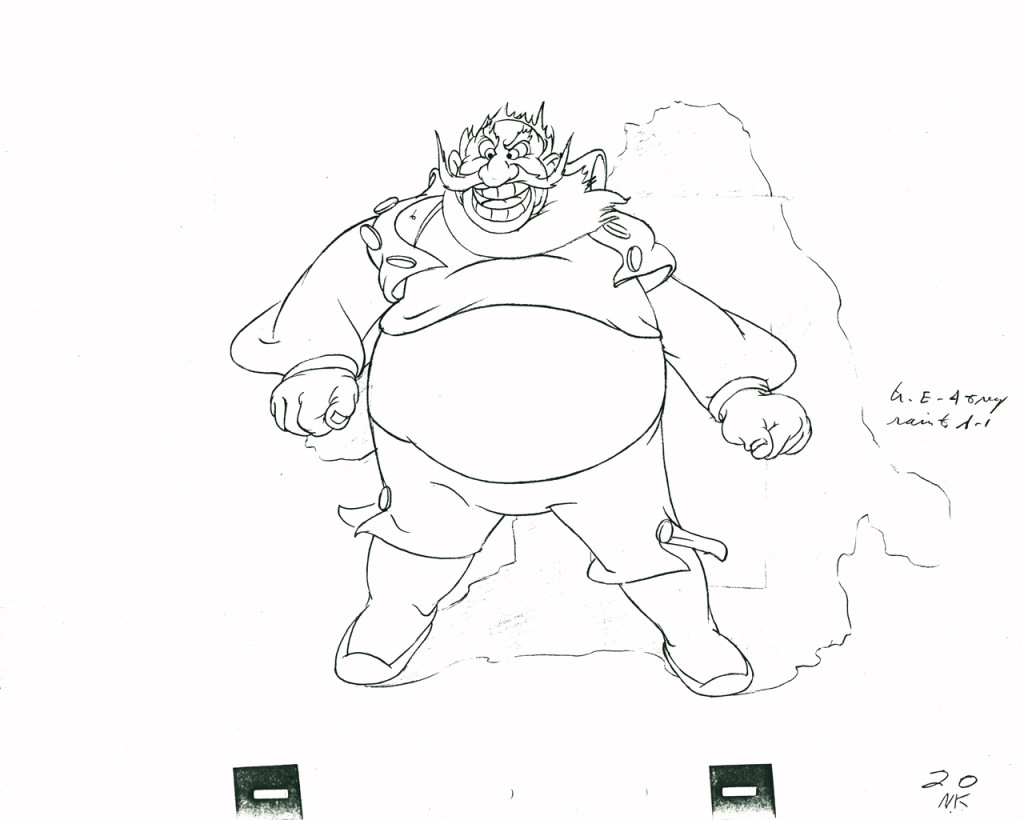

- Right: A discarded sequence from Robin Hood showed a messenger pigeon so fat and heavy he had to be shot into the air. This gave the animators the beginnings of The Albatross Air Lines in The Rescuers.

Phil Harris was so successful, they dragged him into Robin Hood as well. Robin Hood. The very same character from The Jungle Book is now Little John! All those cowboy voices in Robin Hood don’t work either, especially when you mix them up with Brits like Peter Ustinov and Brian Bedford. When these two thespians work against Pat Buttram, Andy Devine and George Lindsey, it’s one thing. Throw in a Phil Harris, and you have something else again. Where are we, the audience, supposed to be? Is it “Merry Ol’ England”? Or is it the lazy take on character development by a few senior animators who have taken license to jump away from the story writers for the sake of easy characters of the generation they’re familiar with. Robin Hood is a mess of a story – even though it’s a solid original they’re working from, and I find it hard to take written advice from these fine old animation pros who take an easy way out for the sake of their animation; shape shifting classic tales to fit their wrinkles.

At least, that’s how I see it – saw it. And perhaps that’s why it’s taken me so long to read this book. I felt (at the age of 14 when these films came out) that the Disney factory had turned into something other than the people who’d made Snow White and Bambi and Lady and the Tramp.

They had, in fact, become the nine old men.

The Jungle Book was the last film Bill Peet worked on. He left

before the film was done. He’d had a long, contentious relationship

with Disney. He never felt he’d gotten the respect he deserved.

They were incredibly talented animators, and they certainly knew how to do their jobs. The animation, itself, was first rate (sometimes even brilliant as Shere Khan demonstrates), but try comparing the stories to earlier features. Even Peter Pan and Cinderella are marvelously developed. Artists like Bill Peet and Vance Gerry knew how to do their jobs, and they did them well. When Peet quit the studio, because he felt disrespected, Disney’s solid story development walked out the door.

The animators were taking the easy route rather than properly developing their stories. The stories had lost all dynamic tension and had become back-room yarns. Good enough, but not good.

Today was Nik Ranieri‘s last day at Disney’s studio. He’s definitive proof, in the eyes of Disney, that 2D animation is dead as an art form. This is the end result of some of the changes Thomas and Johnston suggest in their book. The medium took a hit back then; it just took this long for the suits to catch up. Good luck to Nik and the other Disney artists who no longer work steadily in what is still a vitally strong medium.

Books &Commentary 13 May 2013 05:36 am

Illusions of Thomas, Johnston & Disney

- The Illusion of Life by Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston was first published in 1981. The book came out with a large splash and overwhelming acceptance by the animation community. It’s since remained the one bible that animation wannabees turn to as a source of inspiration and an attempt to learn about that business.

- The Illusion of Life by Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston was first published in 1981. The book came out with a large splash and overwhelming acceptance by the animation community. It’s since remained the one bible that animation wannabees turn to as a source of inspiration and an attempt to learn about that business.

I admitted a couple of weeks back that though I must have been one of the very first to have bought the book, I’d never actually read it. I spent hours poring over the many pictures and the extensive captions, but the actual book – I didn’t read it. I can’t say why, but this was my reality.

Then not too long ago, Mike Barrier wrote that he was not a supporter of the book and its theories, I wondered about that writing and decided to reconsider reading it. I knew I had to go back to find out what I’d stupidly ignored, so I started reading.

The book starts out with a lot of history of animation, something routine and expected from the two animators that lived through a good part of the story. As a matter of fact Thomas and Johnston were at the center of the history. It didn’t take long for the animation “how-to” to kick in. For the remainder of the book, using that history, the two master animators explained how and why Disney animation was done, in their opinions. They write about processes and systems set up at Disney during their tenure there. They write about theories and methods of fulfilling those theories. There’s a lot for them to tell and they’ve succinctly organized it into this book, as a sort of guide.

However, at two points they go wildly into a divergent path from the one that they started building. Their methods altered and, to me, seemed to be about the finances of doing the type of animation they did, rather than the reason. Impractical as those original theories were, I’d believed in the myth all those years to start changing now. So I want to review these two stances instead of outwardly reviewing the book. Besides it’s too long since the book has stood in its own royal space for me to pretend that I could properly review it.

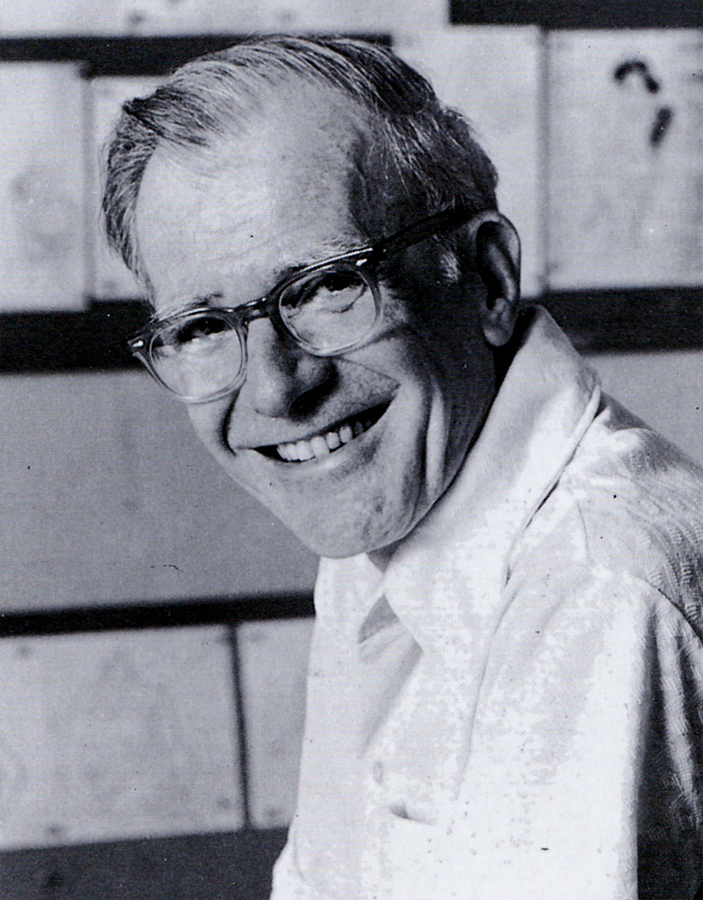

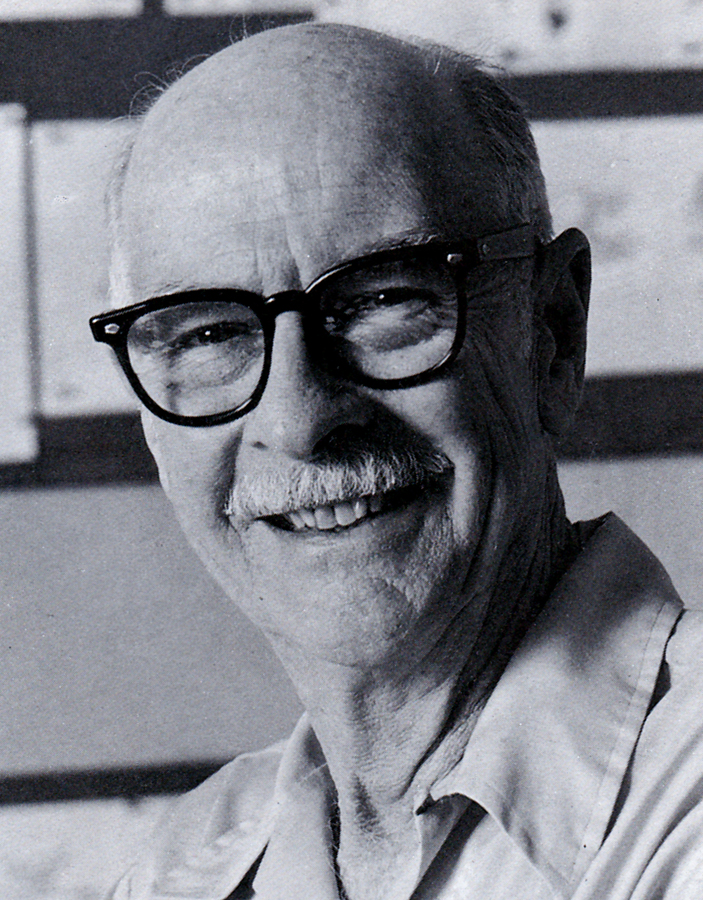

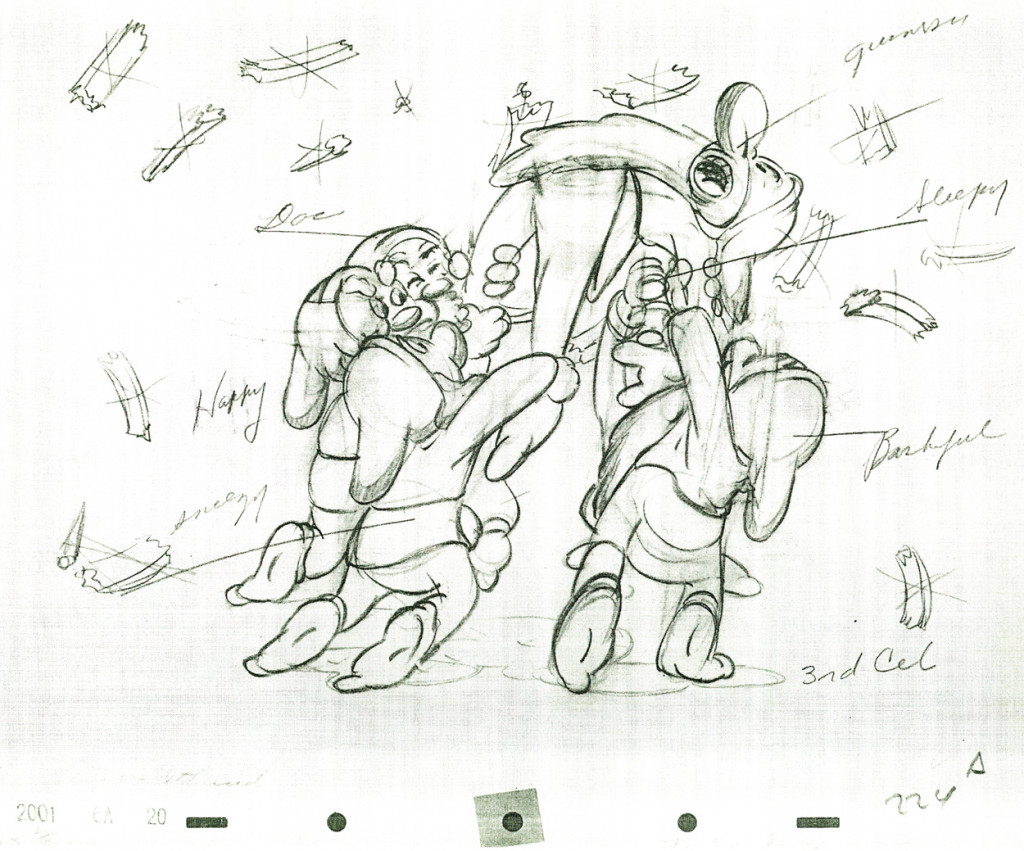

The growth of animators at the Disney studio relied on a system wherein each of the better animators was assigned one character. Unless there was a minimal action by some external character, the one animator ruled over the character.

- Bill Tytla did Stromboli in Pinocchio. He did principal scenes of Dumbo in that film. He handled the Devil in Fantasia (as well as all his twisted mignons within those scenes.) Tytla worked on the seven dwarfs but was the principal animator of Grumpy.

- Bill Tytla did Stromboli in Pinocchio. He did principal scenes of Dumbo in that film. He handled the Devil in Fantasia (as well as all his twisted mignons within those scenes.) Tytla worked on the seven dwarfs but was the principal animator of Grumpy.

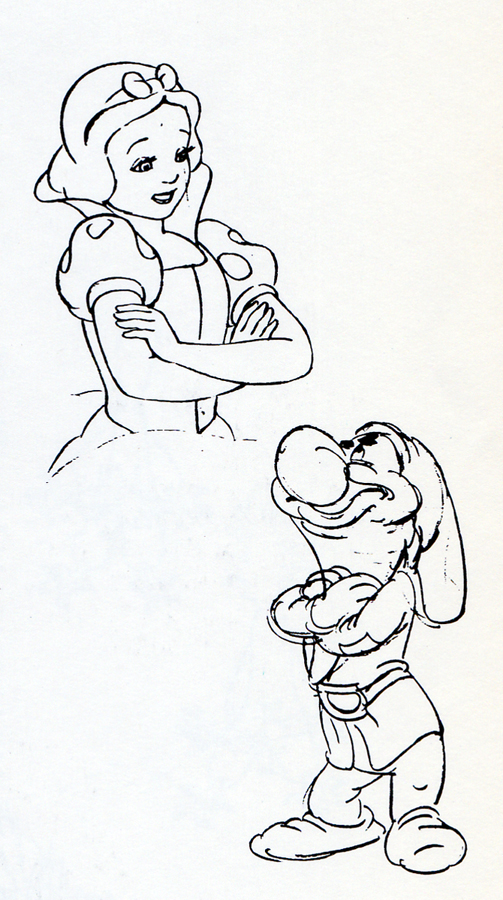

- Fred Moore also did the dwarfs in Snow White but seemed to focus on Dopey. He did Lampwick in Pinocchio and Mickey in The Sorcerer’s Apprentice.

- Marc Davis started as an assistant under Grim Natwick on Snow White. He became the Principal artist behind Bambi, the young deer. He did Alice in Alice in Wonderland, Tinkerbell in Peter Pan, Maleficent in Sleeping Beauty and Cruella de Ville in 101 Dalmatians.

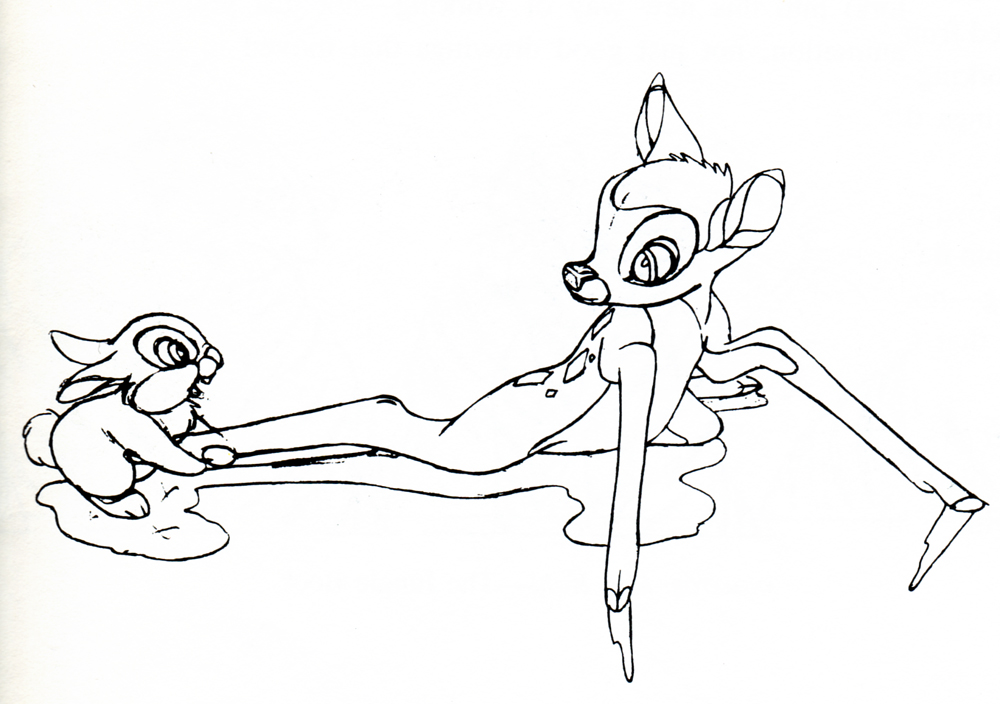

- Frank Thomas did Captain Hook in Peter Pan, the wicked Stepmother in Cinderella, Bambi and Thumper on the ice in Bambi.

- Ham Luske and Grim Natwick did Snow White. The two sides of her personality came about because of conflicts between the two animators. This was a way for Walt to complicate Snow White’s character; he employed two animators with different strong opinions about her movement. By putting Ham Luske in charge, he was sure to keep the virginal side of Snow White at the top, but by having Natwick create the darker sides of the character, Disney created something complex.

Many animators fell under these leaders’ supervision and tutelage, also working on one principal character in each film. This system was something they swore by and broadcast as their way of working at the studio. It would allow the individual characters to maintain their personalities as one animator led the way.

But as Walt grew more involved with his theme park and his television show and the live action movies that were doing well for the studio, things changed at the animation wing of the studio. It became clear, with the over budgeted spending on Sleeping Beauty and the new demands for a different look once xerography entered the picture in 1959. The rhythm and personality of the productions changed, and their methods of animation changed. Walt also sorted out nine loyalists to be his “Nine Old Men” thus dividing the animators into groups, a hurtful way of setting up competition among the animators. ________________________Kahl, Davis, Thomas, Walt, Jackson, Johnston seated

But as Walt grew more involved with his theme park and his television show and the live action movies that were doing well for the studio, things changed at the animation wing of the studio. It became clear, with the over budgeted spending on Sleeping Beauty and the new demands for a different look once xerography entered the picture in 1959. The rhythm and personality of the productions changed, and their methods of animation changed. Walt also sorted out nine loyalists to be his “Nine Old Men” thus dividing the animators into groups, a hurtful way of setting up competition among the animators. ________________________Kahl, Davis, Thomas, Walt, Jackson, Johnston seated

Thomas and Johnston get to justify this

in their book.

Let me read a section from the book to you:

- “Under this leadership, a new and very significant method of casting the animators evolved: an animator was to animate all the characters in his scene. In the first features, a different animator had handled each character. Under that system even with everyone cooperating, the possibilities of getting maximum entertainment out of a scene were remote at best. The first man to animate on the scene usually had the lead character, and the second animator often had to animate to something he could not feel or quite understand. Of necessity, the director was the arbitrator, but certain of the decisions and compromises were sure to make the job more difficult for at least one of the animators.

“The new casting overcame many problems and, more important, produced a major advancement in cartoon entertainment: the character relationship. With one man now animating ever character in his scene, he could feel all the vibrations and subtle nuances between his characters. No longer restricted by what someone else did, he was free to try out his own ideas of how his characters felt about each other. Animators became more observant of human behavior and built on relationships they saw around them every day.”

The question is, now, what are we to make of this statement? Do Thomas & Johnston mean for us to believe that they do more than the single character per film? Does it mean that, like all underprivileged animators everywhere, they now receive scenes rather than characters? Are they trying to tell us that the old, publicized method of animation they did during the “Golden Days” no longer exists?

The question is, now, what are we to make of this statement? Do Thomas & Johnston mean for us to believe that they do more than the single character per film? Does it mean that, like all underprivileged animators everywhere, they now receive scenes rather than characters? Are they trying to tell us that the old, publicized method of animation they did during the “Golden Days” no longer exists?

To be honest I don’t know. Also when are they talking about? At the start of the Xerox era? In the days since Woolie Reitherman has been directing? Do they mean ever since they’ve retired and started writing this book?

Let’s go back a bit.

- In 101 Dalmatians, Marc Davis did Cruella de Vil. That’s it. That’s all he was known for in that film. Oh wait, there were a couple of scenes where he did the “Bad’uns,” Cruella’s two sidekicks. He did these ging into or out of a sequence. In Sleeping Beauty (if we’re going back that far) Davis did Maleficent. Oh, he also did her raven sidekick.

- Milt Kahl did Prince Philip in Sleeping Beauty – and every once in a while his father. He did key Roger and Perdita scenes in 101 Dalmatians. He did Shere Khan in The Jungle Book.

- Milt Kahl did Prince Philip in Sleeping Beauty – and every once in a while his father. He did key Roger and Perdita scenes in 101 Dalmatians. He did Shere Khan in The Jungle Book.

Kahl also seems to be the go-to-guy when they’re looking to have the character defined. The closest thing to Joe Grant’s model department in the late Thirties. If you weren’t sure how Penny might look in a particular scene, you might go to Kahl who’d draw a couple of pictures for you. But that was Ollie Johnston‘s character. You’d probably go to him first, but Johnston would go to Kahl if he needed help.

Kahl also did Robin and some of Maid Marian in Robin Hood. I could keep going on, but let’s take a different direction.

Look at one of Thomas’ greatest sequences, the squirrels in the tree. Starting with Seq.006 Sc.23 and almost completely through and ending with Seq.06 Sc.136 Frank Thomas did the animation. That’s a lot of footage. Yes, that represents four characters: Merlin and Wart as squirrels, as well as the older and younger female squirrels. He did the whole thing (and it’s one of the most beautifully animated sequences ever.)

Look at one of Thomas’ greatest sequences, the squirrels in the tree. Starting with Seq.006 Sc.23 and almost completely through and ending with Seq.06 Sc.136 Frank Thomas did the animation. That’s a lot of footage. Yes, that represents four characters: Merlin and Wart as squirrels, as well as the older and younger female squirrels. He did the whole thing (and it’s one of the most beautifully animated sequences ever.)

But when he was done with that and needed work, he didn’t stop on this film; he also did a bunch of scenes in the “Wizard’s Duel” between Merlin and Mad Madame Mim. Another big chunk.

Hans Perk has done a brilliant service for all animation enthusiasts out there. On his blog, A Film LA, he’s posted many of the animator drafts of feature films. You can find out who animated what scenes from any of the features.

However as Hans posts the batches of sequences, he gives little notes about what we’ll find when we open the drafts. In my view, Hans’ notes are also a treasure.

You can read remarks such as, “Masterful character animation by Milt Kahl and Frank Thomas, action by John Sibley and a scene by Cliff Nordberg.” That seems to tell us everything.

In Sleeping Beauty we can read, “This sequence shows, like no other, the division between Acting and Action specialized animators. Or at least it shows how animators are cast that way. We find six of the “Nine Old Men”, and such long-time Disney staples as Youngquist, Lusk and Nordberg, each of them deserving an article like the great one on Sibley by Pete Docter.”

Or in The Rescuers we read, “Probably the most screened sequence of this movie, the sequence where Penny is down in the cave was sequence-directed by frank and Ollie. They would plan their part of this sequence in rough layout thumbnails, then continue by posing all scenes roughly as can be seen in this previous posting.

“They relished telling the story that Woolie told them the animatic/Leica-reel/work-reel was JUST the right length, and when they posed out the sequence and showed it to Woolie, he said: “See? Just as I said: just the right length!” They kept to themselves that the sequence had grown to twice the length!”

The work, right to the retiring of all of the “Nine Old Men,” would seem to me to prove that these guys, regardless of whether they added one or two other characters to the scenes, did, in fact, take charge of the one starring character.

The work, right to the retiring of all of the “Nine Old Men,” would seem to me to prove that these guys, regardless of whether they added one or two other characters to the scenes, did, in fact, take charge of the one starring character.

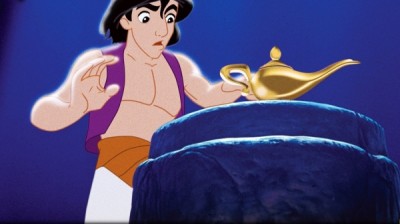

This continues past the retirement of all the oldsters: Glen Keane animated the “beast” in Beauty and the Beast. He animated Tarzan in Tarzan, Aladdin in Aladdin, Ariel in The Little Mermaid, and Pocahontas in Pocahontas. Andreas Deja animated Jafar, the Grand Vizier in Aladdin, Scar in The Lion King, Lilo in Lilo and Stitch, and Gaston in Beauty and the Beast. Mark Henn animated Belle in Beauty and the Beast (from the Florida studio), Jasmine in Aladdin, young Smiba in The Lion King, and Mulan and her father in Mulan.

Need I go on? What are Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston talking about in their book? I’m confused.

I have a lot left to say about this book, much of it good, but next time I want to write about something else that confuses me with another somewhat contradictory statement in the book.

This has gotten a bit long, and I have to cut it here.

Animation &Books &Comic Art &Disney &Guest writer &Illustration 11 Apr 2013 05:09 am

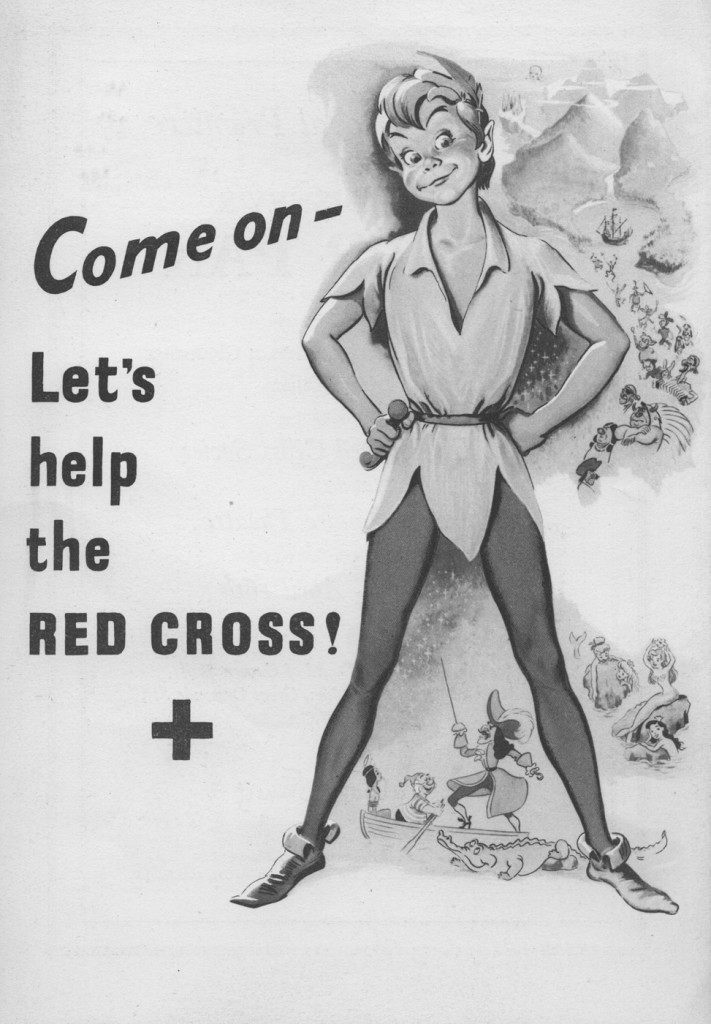

Peter Hale’s Peter Pan

About six weeks ago, I was contacted by Peter Hale in the UK about a “strip book” of Peter Pan that was published in England to tie into the original release of the movie. Peter sent me some beautiful scans of the artwork in the book, and I posted it (here.)

Mr. Hale promised a second book that was also published at the time.

It turns out he has done some extensive research into the subject of the books in conjunction with the Disney film. This week, I received a complete breakdown of all the “Pan” books that were published in the UK, and the scans for another book. I’ve decided that I really have to post what Peter has written; it’s that extensive. I’ll follow up with another post of the books scanned.

Many thanks to Peter Hale for sharing this fine work with the “Splog” and its readers.

The rest of this post is over to Peter Hale who writes:

My (superficial) research into the Disney-illustrated books of Peter Pan published

My (superficial) research into the Disney-illustrated books of Peter Pan published

in the UK in 1953 has wandered off on several tangents.

Firstly a rough chronology of the development of the original book, and the Disney

film:

1902 – Barrie’s fantasy novel (for adults) The Little White Bird includes a sequence that

features Peter Pan, a 7-day-old baby who flies away from home so that he will never

grow up, and, after learning that he is not a bird, and therefore can’t fly, is

adopted by the faries in Kensington Gardens.

1904 – Barrie expands the idea of Peter Pan into a play, to great success.

1905 – The chapters from The Little White Bird that feature Peter Pan are republished for

children as Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens by his publishers, Hodder & Stoughton,

to cash in on the play’s popularity.

1911 – Because of the demand for Peter Pan products, Barrie publishes a novel based on the

play. He adds a coda wherein Peter promises to return each spring to take Wendy back

to Neverland to do the Spring Cleaning. But he starts to miss years, until he has

forgotten her altogether. Wendy grows up and has a daughter of her own. One day

Peter returns for her and is distressed to find that she is too old to fly away. But

he soon meets her daughter Jane and so takes her to Neverland, and when she grows

old, her daughter Margaret will take over – because he does need a mother.

1915 – Hodder & Stoughton publish an abridged version of Peter Pan for younger children,

written by May Byron with Barrie’s approval. They title it Peter Pan & Wendy.

1921 – A version of May Byron’s adaptation “retold for Little People” is published, with

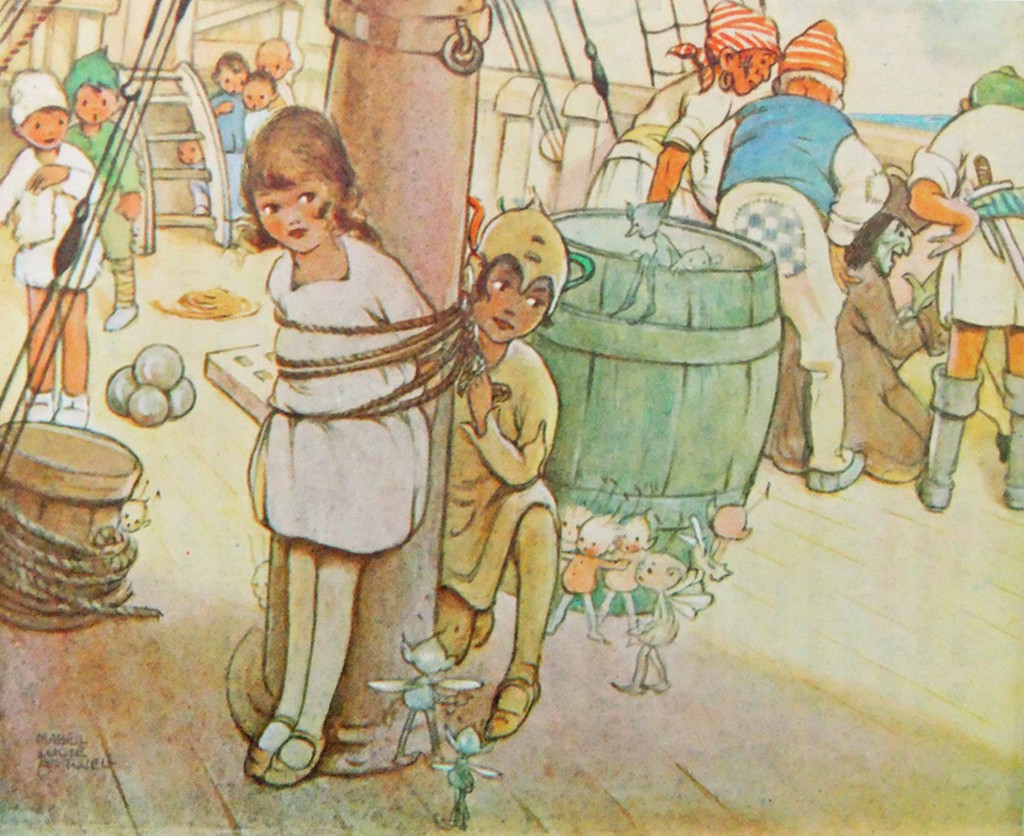

illustrations by Mabel Lucie Attwell at Barrie’s request. Her drawings of babylike

characters presumably matched Barrie’s vision.

1929 – Barrie donates all the rights to ‘Peter Pan’ to the Great Ormond Street Hospital for

Children.

1935 – Walt Disney plans to follow Snow White with Peter Pan, but has difficulty securing

screen rights from Great Ormond St Hospital.

1939 – Having finally secured rights to make an animated film version, the Disney studios

schedule Peter Pan to follow Bambi and Pinocchio.

1941 – The entry of the US into WWII forces Disney to postpone productions.

1947 – The Disney Studios put Peter Pan back into production.

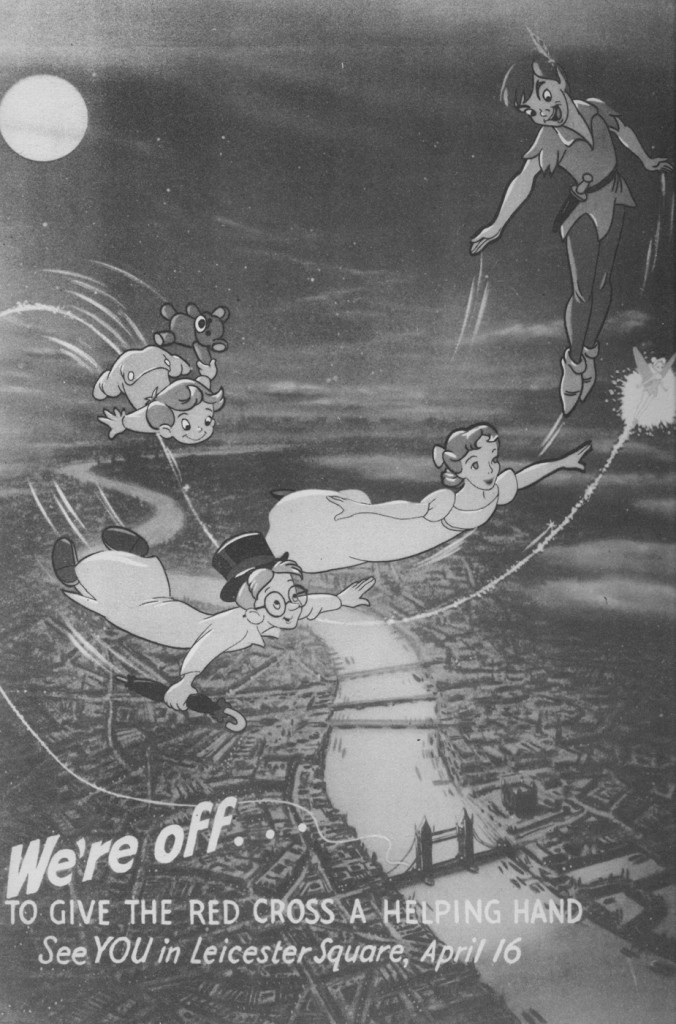

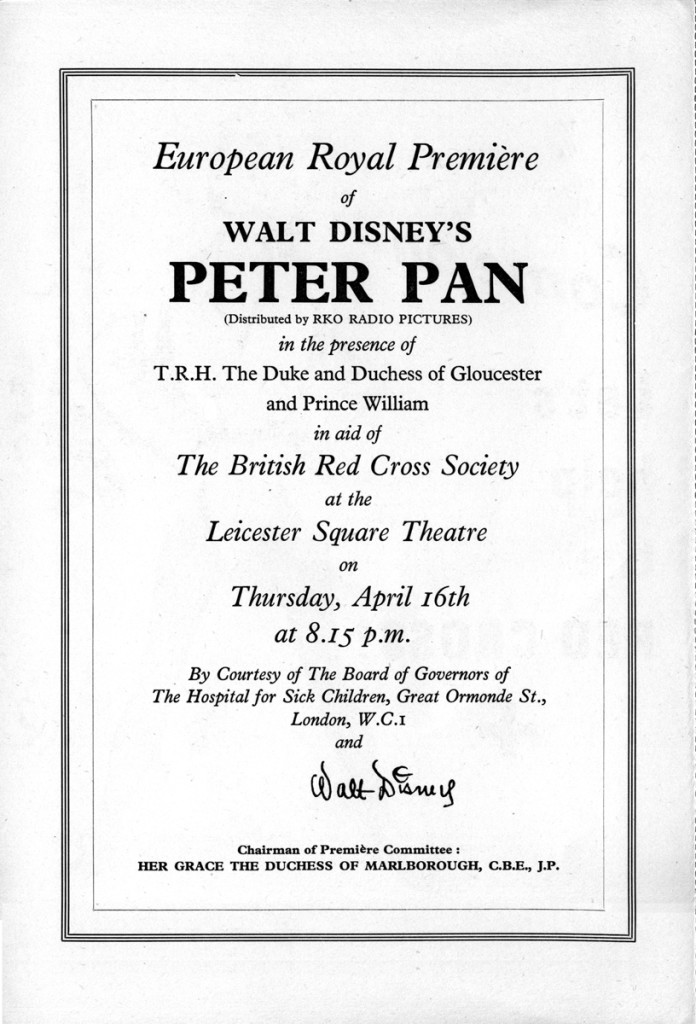

1953 – February 5th: Walt Disney’s Peter Pan premieres at the Roxy Theater, New York.

1953 – April 16th: Walt Disney’s Peter Pan has its UK premiere at the Leicester Square

Theatre, London.

1953 – May: Walt Disney’s Peter Pan is shown at the 6th Cannes Festival.

1953 – July 27th: Walt Disney’s Peter Pan goes on general release in the UK.]

Through the 40s her characters became ever more chubby, stunted and stylised, but in 1915 she was still starting out as an illustrator.

Here is her version of Peter freeing Wendy from the mast.

The illustrations she did then became almost as much part of the May Byron version of “Peter Pan and Wendy” as Tenniel’s were part of “Alice”, and it was still being published in 1980. A reprint of the 1921 edition was published in 2011.

Which brings us to the versions of Peter Pan published in the UK in 1953.

Jacqueline Rose, in her book “The Case of Peter Pan”, lists the following six books published in the UK that year:

- Barrie, J. M. Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, illustrated by Arthur Rackham, ‘Peter Pan Books’ (from 9 years) (London: Hodder and Stoughton, I953)

- Bedford, Annie N. Disney’s Peter Pan and Wendy, ‘Peter Pan Books’ (London: Hodder and Stoughton, I953)

- Byron, May. Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, illustrated by Arthur Rackham, ‘Peter Pan Books’ (for 6 to 8 year olds) (London: Hodder and Stoughton, I953)

- Byron, May. The Walt Disney Illustrated Peter Pan and Wendy, ‘Peter Pan Books’ (for 8 to 9 year olds) (Leicester: Brockhampton Press, I953)

- Pearl, Irene. Walt Disney’s Peter Pan, retold from the original story by J. M. Barrie, ‘Peter Pan Books’ (for 3 to 6 year olds) (Leicester: Brockhampton Press, I953)

- Winn, Alison. Walt Disney’s Peter Pan, retold from the original story by J. M. Barrie ‘Peter Pan Books’ (for 6 to 8 year olds) (Leicester: Brockhampton Press, I953)

as opposed to just one in 1952:

- Byron, May. Peter Pan, retold for the nursery, illustrated by Mabel Lucie Attwell, ‘Peter Pan Books’ for 3 to 6 year olds) (Leicester: Brockhampton Press, I952)

Two of these are versions of the Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens ‘origin’ story, which Disney had decided not to include in the film.

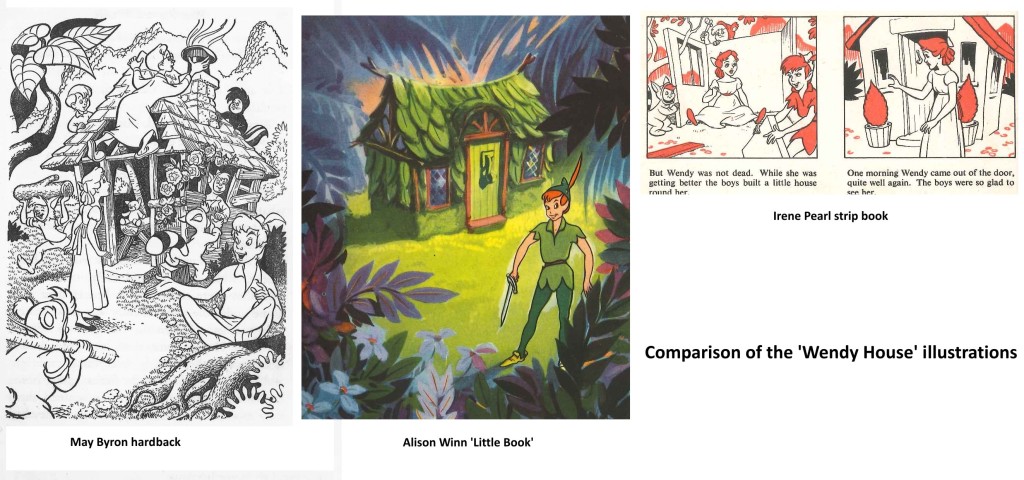

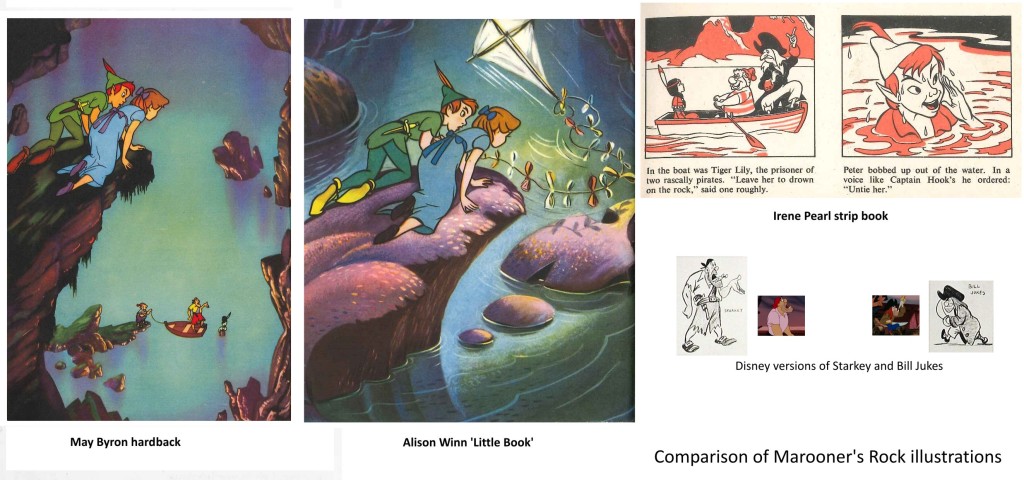

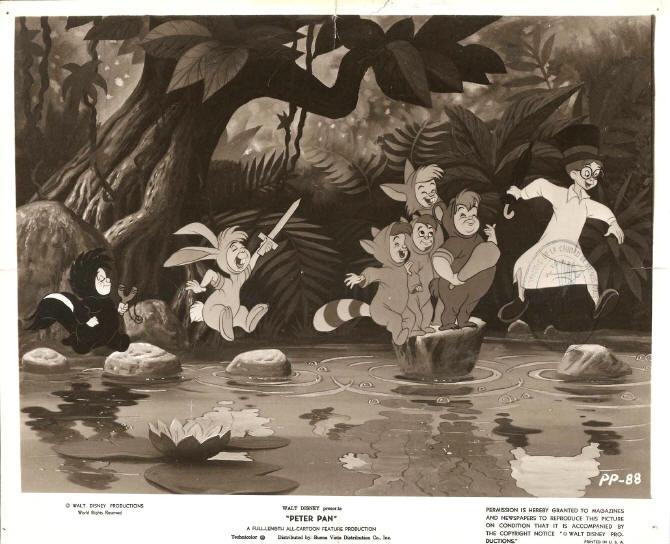

The remaining 4 are all “Illustrated by Walt Disney”. The Irene Pearl version is the strip book already posted, and scans of the May Byron book and the Alison Winn “Little Book” will follow. These all follow the Barrie novel rather than the Disney film, although with different simplifications and omissions.

The Annie N. Bedford book is one I have not been able to trace – she is the American author who wrote the Golden Books version of the Disney film, so this could be a UK publication of that book. It is given as published by Hodder & Stoughton, Barrie’s original publisher. The back cover of the Brockhampton ‘Little Book’ lists a different Hodder & Stoughton book.

“J. M. Barrie’s original Peter Pan and Wendy for older Boys and Girls, with illustrations by Walt Disney”. I have not been able to trace a copy of either book. These two books represent the two ends of the spectrum:

Barrie’s original text and the story of the film.

Finally there is the complication of Dean & Son’s Walt Disney’s Peter Pan, from the motion picture, a book of the film. This has no publication date. The illustrations are given as copyright Walt Disney 1953, but this is not a guide to the publication date, as Disney did not own the publishing rights and so the illustrations were always copyrighted to 1953, the year of the film’s release. It is probable that the Dean book was published later than 1953.

It is published ‘by arrangement with Hodder & Stoughton’, which either means it may be a reprint of the Bedford book, or just an acknowledgement that Hodder held the publication rights to Peter Pan.

In contrast I can only find one UK ‘Disney’s Alice in Wonderland‘ book that might have been published in 1951, and certainly no Carroll text with Disney illustrations.

So why so many Peter Pans? The UK’s wartime paper rationing ended in 1950 so that would not be an issue.

Was it because Disney did not have the publishing rights, so this collaboration was necessary to promote the film?

Was it just, as I’d thought previously, that the British might object to tampering with the story? Or was Disney just trying to overcome the sort of criticism that his Alice had suffered in the UK (that it was too Americanised and not sufficiently true to the book) by linking his film to the original text?

Comparing the 3 Brockhampton books the illustrations are all different, and by different hands it would appear, but all show fidelity to the Disney style. I am assuming that these illustrations were done by British illustrators specially for the books, as where the illustrations differ from the film the artists seem to have consulted the particular text they are working with for details.

Hence the May Byron text describes the adding of a shoe as a knocker, and John’s hat as a chimney, and the illustration shows the hat, although it also shows Wendy watching the building from outside, which is quite wrong!

The marooning of Tiger Lily is done in the book by two pirates, with Hook turning up

later.

In the May Byron book they are named as Smee and Starkey, and the

illustration has Hook replaced by a likeness of the Disney Starkey (but with a

yellow shirt instead of pink). The strip book doesn’t name the pirates and Hook is

here replaced by Bill Jukes. The Alison Winn version omits the marooning of Tiger Lily entirely and just has Hook turn up to attack Peter.

All three books have Wendy exhausted and Peter injured after the encounter – both

stranded on the rock unable to fly back. John’s kite collects Wendy, while Peter is

rescued by the Never bird, whose floating nest serves as a boat. The Winn ‘Little

Book’ uses a version of the shot of Peter and Wendy watching Hook and Smee from on

high, but without the pirates, truncated to appear a low rock, and with a kite added

in.

This brought me to wonder how much Disney reference they were given, and what it

consisted of. Many of the scenes are close to shots from the film. But a look at the

Dean book, which seems to be taken directly from colour stills, shows that these are

not actually shots from the movie.

Anyone who has ever tried to put together presentation scenes from the cels of an

animated film knows that there are always problems – the best pose is poorly traced,

or one character is in an ungainly inbetween position – whatever, that perfect key

image from the storyboard just isn’t there in the actual film, where, deliberately,

nothing hits a strong extreme at the same time.

Hence it appears that the lobby card stills or coloured transparencies that Disney

circulated in their press packs etc. had been specially recreated – a lead animator

had redrawn the characters from various key frames as they ought to have looked, and

these drawings had been traced and painted on cel with extra care, and combined with

a new version of the background to be photographed by a stills camera. (I presume

the composites then went up on someone’s wall!) The same thing, of course, as the

re-posing of key scenes that is typically done by a stills photographer on the set

of a live action film after it has been shot.

The illustrators appear to have had coloured stills and model sheets to work from.

Does anyone know how much reference was supplied? Walt Disney Studios had an office

in London specifically to deal with promotion, distribution, licensing artwork etc.

Did they do artwork for any of the books – or just supply references?

Lastly, the curator of the Great Ormond St. Children’s Hospital Archives has kindly

sent me these scans relating to the London Premiere of Peter Pan on 16th April 1953

It’s worth taking note that Hans Perk has recently posted the animators’ drafts from the Disney film, Peter Pan. Go here to read and/or collect them.

Articles on Animation &Books &Commentary 18 Feb 2013 04:59 am

Appreciation

The deeper you go, the deeper you go.

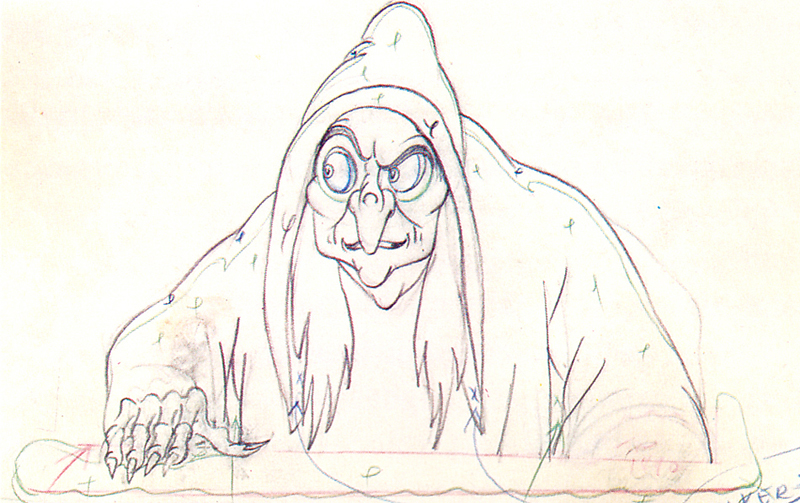

In reviewing the two J.B. Kaufman books on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, I found them impeccable in their attempt to reconstruct the making of this incredibly important movie. They followed a strict pattern of analyzing the film in a linear fashion going from scene one to the end.

In reviewing the two J.B. Kaufman books on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, I found them impeccable in their attempt to reconstruct the making of this incredibly important movie. They followed a strict pattern of analyzing the film in a linear fashion going from scene one to the end.

However, the analysis Kaufman offered brought me back to the bible, Mike Barrier‘s Hollywood Cartoons. Rereading his chapter on Snow White, you realize how much depth he offers in a far shorter amount of space. Of course, there are few illustrations in Barrier’s book, but what writing is there is golden. He meticulously analyzes the work of different animators using a very strict code of principles. If you can agree with him, the book he’s written opens up enormously.

However, the analysis Kaufman offered brought me back to the bible, Mike Barrier‘s Hollywood Cartoons. Rereading his chapter on Snow White, you realize how much depth he offers in a far shorter amount of space. Of course, there are few illustrations in Barrier’s book, but what writing is there is golden. He meticulously analyzes the work of different animators using a very strict code of principles. If you can agree with him, the book he’s written opens up enormously.

Once you get to the chapter, post-Snow White, which catalogues the making of Pinocchio, Fantasia, Bambi and Dumbo you are in the deep water. Mike pointedly criticizes some of the greatest animation ever done. His analysis of Bill Tytla’s Stromboli is ruthless. Though I am an enormous fan of this animation, I cannot say I disagree with what he has to say. Though I think differently of the animation.

Once you get to the chapter, post-Snow White, which catalogues the making of Pinocchio, Fantasia, Bambi and Dumbo you are in the deep water. Mike pointedly criticizes some of the greatest animation ever done. His analysis of Bill Tytla’s Stromboli is ruthless. Though I am an enormous fan of this animation, I cannot say I disagree with what he has to say. Though I think differently of the animation.

Here’s a long excerpt from this chapter:

- No animator suffered more in this changing environment than Tytla. His expertise is everywhere evident in his animation of Stromboli—in the sense of Stromboli’s weight and in his highly mobile face—but however plausible Stromboli is as a flesh-and-blood creature, there is in him no cartoon acting on the order of what Tytla contributed to the dwarfs. At Pinocchio’s Hollywood premiere, Frank Thomas said, W. C. Fields sat behind him, “and when Stromboli came on he muttered to whoever was with him, ‘he moves too much, moves too much.’” Fields was right-although not for the reason Thomas advanced, that Stromboli “was too big and too powerful.”

- In the bare writing of his scenes, Stromboli, more than any of the film’s other villains, deals with Pinocchio as if he were, indeed, a wooden puppet—suited to perform in a puppet show, and perhaps to feed a fire—rather than a little boy. But the chilling coldness implicit in the writing for Stromboli finds no echo in the Dutch actor Charles Judels’s voice for the character. Judels’: Stromboli speaks patronizingly to Pinocchio, as he would to a gullible child, and his threat to use Pinocchio as firewood sounds like a bully’s bluster. As Tytla strained to bring this poorly conceived character to life, he lost the balance between feeling and expression. The Stromboli who emerges in Tytla’s animation is too vehement, “moves too much”; his passion has no roots, and so he is not convincing as a menace to Pinocchio, except in the crudest physical sense. There is nothing in Stromboli of what could have made him truly terrifying: a calm dismissal of Pinocchio as, after all, no more than an object.

- To some extent, Tytla may have been overcompensating for live action that even Ham Luske acknowledged was “underacted.” But Luske defended the use of live action for Stromboli by arguing that it had kept Tytla on a leash: “If he had been sitting at his board animating, without any live action to study, he might have done too many things.”

I agree, as Barrier says, that Stromboli is a flawed character, and I agree that the movement is broad and overstated. However, I think that this was Tytlas’s only possible entrance into the material, into trying to further the characterization. No, it could not be as deep as the work he’d done on Grumpy in Snow White, but the character of Stromboli isn’t as small as that name, “Grumpy”. A lot more was offered and had to be circled to simplify as best as possible for the small amount of screen time he would have in Pinocchio. And, yes, he comes off like a blowhard with a lot of bluster. But that’s not the way Pinocchio sees him. Pinocchio is made of wood, as Stromboli reminds us, but he is also an innocent, a child learning about the world.

Barrier’s chapter, as I said, moves quickly through this material covering four of the greatest Disney films; no, four of the greatest animated features ever done. In relatively few pages you feel as though he’s gotten it all in there and has even said more in depth than almost any historian about this period of Disney animation. I’ve read this chapter at least a dozen times, and it continues to grow richer for me. I think it’s possible the greatest piece ever written about animation.

Barrier’s writing, vocabulary, choice of phrase is all charged to keep the material tight. He’s writing a large book, and he has to get a lot in.

Perhaps some day he will have one of those big picture books to write where he will have the freedom to expound on the material. I did once read such a book. Mike Barrier had been employed to write a history of the Warner Bros. studio, and I got to read the first draft of the manuscript. I had a couple of hours and sat in a chair, thumbing pages. The images that were to be in the book were on large chromes. It was all an extraordinary experience for me, and I remember it somewhat hazily, as if remembering a golden afternoon. Of course that book was cancelled when management changed hands, and the world lost a great book.

Perhaps some day he will have one of those big picture books to write where he will have the freedom to expound on the material. I did once read such a book. Mike Barrier had been employed to write a history of the Warner Bros. studio, and I got to read the first draft of the manuscript. I had a couple of hours and sat in a chair, thumbing pages. The images that were to be in the book were on large chromes. It was all an extraordinary experience for me, and I remember it somewhat hazily, as if remembering a golden afternoon. Of course that book was cancelled when management changed hands, and the world lost a great book.

Can there be any wonder that I go to the Barrier website daily, knowing full well that it’s often months between posts? I just keep looking for new material from him, and will continue my daily routine hoping for the small brightly colored package on his site. It’s almost important for there not to be frequent posts or the new ones wouldn’t always shine as well. However, two or three times a year, there is something rich there, and my search has brought the golden fish. (Yes, I’m exaggerating somewhat like Tytla did in his animation of Stromboli. But the point gets made.)

Even if there’s nothing new there, there’s plenty old. Many old Funnyworld articles or interviews done with Milt Gray. It’s a deep site full of deep writing.

Commentary &Disney 22 Jan 2013 08:28 am

Rambling on some Disney Features

- A stash of Disney animated features were on television this Sunday. Hercules, Lady and the Tramp, Alice in Wonderland, Aladdin, Cinderella, and The Lion King all followed each other immediately, one on top of the other. Actually some of them even overlapped each other. The credits for Hercules (miniscule and too tiny to read) played on the left half of the screen while the opening credits for Lady and the Tramp played on the right half of the screen. They were going to milk every ounce of Disney Family viewing they could for the money.

- A stash of Disney animated features were on television this Sunday. Hercules, Lady and the Tramp, Alice in Wonderland, Aladdin, Cinderella, and The Lion King all followed each other immediately, one on top of the other. Actually some of them even overlapped each other. The credits for Hercules (miniscule and too tiny to read) played on the left half of the screen while the opening credits for Lady and the Tramp played on the right half of the screen. They were going to milk every ounce of Disney Family viewing they could for the money.

I was pretty sick on Sunday, the flu has struck our little home hard, and I’m not yet down for the count but feel pretty close. So I could see how much of this 2D mania I could stomach – flu and all. I didn’t come in to it until the very end of Hercules, which is probably the one film I would have liked seeing again, but virtually missed.

Some quick notes: It was nice to see Lady and the Tramp letterboxed for Cinemascope. The opening is still as tender as ever, and the Siamese cats are beautifully layed out for scope. The layout, backgrounds and animation – particularly the effects animation of the chase for Tramp in the dog pound wagon is exceptional. I think it’s probably one of the best sequences in the film. “Bella Notte,” of course, works well, but except for the sentimental emotion the sequence was never one of my favorites. There isn’t much for the dogs to do while the singing continues. They do pull a lot out of the spaghetti, but for much of it, the dogs just sit there, or in closer shots chew their food.

Alice seemed loud and aggressive though some of the coloring seemed inspired, and it’s amazing to see how much of Mary Blair is still in there in some parts – particularly the end of the caterpillar sequence. I found the Cheshire Cat a blessing in the wilderness. A lot is done with little subject matter, and it’s all in the excellent animation, of course. It’s obvious that Alice is a tough character to animate, but she’s done brilliantly. Essentially, she’s the “straight man” for everyone else in the film. She just sits there while the other characters bounce their schtick off of her. As I noted in a past post I am intrigued by the use of shadows in the transitional parts of the film. It works stunningly well , and this device virtually holds a lot of the film together in some odd quiet little way. I’d be curious to see more of this done with other films. You need a director with a big vision watching out for the film as a whole. I’m not crazy about a lot of the wild animation of the many zany characters that seem more cartoon to me than do they feel like Lewis Carrol creatures. There’s an interesting little scene where Alice sits down to cry in the woods. At first, she’s alone, then like Snow White in a similar situation feels sorry for herself and lets go. Little woodland creatures, deer and squirrels and rabbits and birds surround Snow White. Alice greets the odd little cartoon characters which feel as though they’d escaped from Clampett’s Porky in Wackyland. The woodland characters in Snow White serve the purpose of moving the heroine forward in the story to the dwarfs’ cottage. The zanies in Alice just disappear before she stops crying. Essentially, they’re pointless little creatures that offer nothing to the film. Fortunately the Cheshire Cat returns at this point. He fades in just as all the others have faded off.

Alice seemed loud and aggressive though some of the coloring seemed inspired, and it’s amazing to see how much of Mary Blair is still in there in some parts – particularly the end of the caterpillar sequence. I found the Cheshire Cat a blessing in the wilderness. A lot is done with little subject matter, and it’s all in the excellent animation, of course. It’s obvious that Alice is a tough character to animate, but she’s done brilliantly. Essentially, she’s the “straight man” for everyone else in the film. She just sits there while the other characters bounce their schtick off of her. As I noted in a past post I am intrigued by the use of shadows in the transitional parts of the film. It works stunningly well , and this device virtually holds a lot of the film together in some odd quiet little way. I’d be curious to see more of this done with other films. You need a director with a big vision watching out for the film as a whole. I’m not crazy about a lot of the wild animation of the many zany characters that seem more cartoon to me than do they feel like Lewis Carrol creatures. There’s an interesting little scene where Alice sits down to cry in the woods. At first, she’s alone, then like Snow White in a similar situation feels sorry for herself and lets go. Little woodland creatures, deer and squirrels and rabbits and birds surround Snow White. Alice greets the odd little cartoon characters which feel as though they’d escaped from Clampett’s Porky in Wackyland. The woodland characters in Snow White serve the purpose of moving the heroine forward in the story to the dwarfs’ cottage. The zanies in Alice just disappear before she stops crying. Essentially, they’re pointless little creatures that offer nothing to the film. Fortunately the Cheshire Cat returns at this point. He fades in just as all the others have faded off.

Aladdin has always bothered me. It feels more like a Warner Bros film than a Disney feature. The wild animation and even the style of the animation gives me good reason to feel this way. However, I think I came to terms with that in watching it again (maybe my 12th time?) mixed in with these other movies. The film is what it is and does it well. Eric Goldberg’s genie is a classic combination with the Robin Williams voice over, and Eric gets full use of that voice and the business happening on screen. The material presented has dated some, though not as bad as I expected. How lone before kids don’t know who people like Ed Sullivan are? Though I suppose this is similar to the personalities left over from the celebrity cartoons of the 30′s & 40′s. Mother Goose Goes Hollywood needs a program of its own to tell us who half of those caricatures represent. And they are great pieces of art that Joe Grant did for them. The villain in Aladdin tries hard but he’s not menacing just threatening. There was never anything that I worried about with him, and this feeling goes back to my very first viewing of the film. I do like the tiger in the film, Jasminda’s pet. That cat makes up for the ineffectual father. His character is not anything I can really associate with.

Aladdin has always bothered me. It feels more like a Warner Bros film than a Disney feature. The wild animation and even the style of the animation gives me good reason to feel this way. However, I think I came to terms with that in watching it again (maybe my 12th time?) mixed in with these other movies. The film is what it is and does it well. Eric Goldberg’s genie is a classic combination with the Robin Williams voice over, and Eric gets full use of that voice and the business happening on screen. The material presented has dated some, though not as bad as I expected. How lone before kids don’t know who people like Ed Sullivan are? Though I suppose this is similar to the personalities left over from the celebrity cartoons of the 30′s & 40′s. Mother Goose Goes Hollywood needs a program of its own to tell us who half of those caricatures represent. And they are great pieces of art that Joe Grant did for them. The villain in Aladdin tries hard but he’s not menacing just threatening. There was never anything that I worried about with him, and this feeling goes back to my very first viewing of the film. I do like the tiger in the film, Jasminda’s pet. That cat makes up for the ineffectual father. His character is not anything I can really associate with.

Cinderella is a very interesting film. I go into it thinking I hate it and get completely tied up with the extraordinary pacing of the film. Every scene is so exact and tight. They really knew what they were doing. I’m not the biggest fan of the human animation, but at the same time I’m in awe of it. It isn’t really rotoscoping, but it’s so beautifully pulled off the live action they shot, that it feels completely fresh. The cartoon animals play off the humans as the dwarfs did in Snow White. They look as they they come from different films and the style of animation is so different. The set pieces are exquisite. That entire piece with Cinderella locked in her room, the animals fighting to release her all those stairs away and the final reveal of her own glass slipper. It’s so beautifully melodramatic and so perfectly executed. Yes, this is an odd film for me to watch.

Cinderella is a very interesting film. I go into it thinking I hate it and get completely tied up with the extraordinary pacing of the film. Every scene is so exact and tight. They really knew what they were doing. I’m not the biggest fan of the human animation, but at the same time I’m in awe of it. It isn’t really rotoscoping, but it’s so beautifully pulled off the live action they shot, that it feels completely fresh. The cartoon animals play off the humans as the dwarfs did in Snow White. They look as they they come from different films and the style of animation is so different. The set pieces are exquisite. That entire piece with Cinderella locked in her room, the animals fighting to release her all those stairs away and the final reveal of her own glass slipper. It’s so beautifully melodramatic and so perfectly executed. Yes, this is an odd film for me to watch.

I didn’t make it to The Lion King. I’ve seen that about half a dozen times in the last few months so preferred watching my soap opera – Downton Abbey.

Watching these films back to back to back like this sort of lessens them but at the same time one is overwhelmed by the amazing craftsmanship held so high for so long. For years I felt the modern films, Aladdin, Beauty and the Beast, Hercules were lesser efforts compared to what the “masters” did. But now I’m sure they’re every bit as good as some of the later classics. No, I don’t think Snow White, Pinocchio, Fantasia, Dumbo and Bambi can be beaten today, but the new films are definitely equal to Lady and the Tramp, Cinderella, Alice In Wonderland and anything later than that. (I actually think Sleeping Beauty is in a class of its own and haven’t seen the equal to that from the more recent people. Actually, I take that back. I think Prince of Egypt is right up there. That’s a magnificent film, and it’s one I’d like to discuss more in depth sometime soon.)

Watching these films back to back to back like this sort of lessens them but at the same time one is overwhelmed by the amazing craftsmanship held so high for so long. For years I felt the modern films, Aladdin, Beauty and the Beast, Hercules were lesser efforts compared to what the “masters” did. But now I’m sure they’re every bit as good as some of the later classics. No, I don’t think Snow White, Pinocchio, Fantasia, Dumbo and Bambi can be beaten today, but the new films are definitely equal to Lady and the Tramp, Cinderella, Alice In Wonderland and anything later than that. (I actually think Sleeping Beauty is in a class of its own and haven’t seen the equal to that from the more recent people. Actually, I take that back. I think Prince of Egypt is right up there. That’s a magnificent film, and it’s one I’d like to discuss more in depth sometime soon.)

Oh, of course, this is all my own opinionated nonsense. Someone else would have a completely different list. I’m, obviously, leaving cg films out of this discussion. To be honest, I can’t even find a story there that I think measures up to most of the Disney classics. I’m also not thinking much about non-Disney works, but there’s an obvious reason for that. However, some of those Dreamworks 2D films are exceptional and deserve a lot of attention. Attention they haven’t received. Spirit has stunning animation, as do a number of others. They really need a bit of time.

Oh, of course, this is all my own opinionated nonsense. Someone else would have a completely different list. I’m, obviously, leaving cg films out of this discussion. To be honest, I can’t even find a story there that I think measures up to most of the Disney classics. I’m also not thinking much about non-Disney works, but there’s an obvious reason for that. However, some of those Dreamworks 2D films are exceptional and deserve a lot of attention. Attention they haven’t received. Spirit has stunning animation, as do a number of others. They really need a bit of time.

I had some bigger thoughts brought on by watching them all, but I’ve gone on too long already. So I’ll let this rambling post fizzle out. Hope you don’t mind, but I’m getting to enjoy writing these diatribes.

Commentary &Daily post 05 Jan 2013 08:20 am

Animator names?

I’ve been an animation fan forever. Back in the fifties (when I wasn’t yet in my teens) I wrote fan letters to Joshua Meador, Bill Justice, and Art Riley. I don’t know if any of them ever received any of my letters, since I always got back a 4″x6″ postcard from Walt Disney thanking me. Mind you, these cards were always interesting and different, so I’m not sorry to have received them.

I’ve been an animation fan forever. Back in the fifties (when I wasn’t yet in my teens) I wrote fan letters to Joshua Meador, Bill Justice, and Art Riley. I don’t know if any of them ever received any of my letters, since I always got back a 4″x6″ postcard from Walt Disney thanking me. Mind you, these cards were always interesting and different, so I’m not sorry to have received them.

In the sixties, Mike Barrier‘s Funnyworld Magazine opened the world to interviews with some real animators. Then you’d start to see similar articles in the likes of Millimeter or Film Comment. Chuck Jones and Tex Avery got lots of attention. I saved and cherished those issues. Hell, I just about memorized them. ASIFA East brought Bob Clampett and a dozen other animators from Yoji Kuri to Frank Thomas & Ollie Johnston to our little New York corner of the world.

The point is that we got to know who a lot of animators were.

The point is that we got to know who a lot of animators were.

I could tell what scenes Ollie Johnston had done from those that Milt Kahl had done; I can easily identify Bobe Cannon‘s work from Ken Harris‘. (Can anyone but Cannon have drawn with such beautifully rounded lines as can be seen in the lion on the right?

No, that’s purely his work, and it’s there from the earliest right through to Moonbird. Just brilliant!)

{Check out this whole post on John Kricfalusi‘s site in 2006. Gorgeous.}

It became, really, the era of the animator. Many of them were deified by others like me, and deservedly so, even though others remained in obscurity. Watching stars like Dick Williams bring Harris and Hubley and Babbitt to London to train his staff brought fame to the little British studio. Dick soon brought as many famous animators to Raggedy Ann in New York. A star-studded staff assembled, for the first time, for their celebrity and ability and personality. (Star animators rather than star voices. Too bad there was no star writer.)

And Jim Tyer! There’s a whole cult of people who rally around Tyer’s work, and that pleases me. No one I knew, when I was a child, had any idea who Tyer was, but I searched every Mighty Mouse show on Saturday morning TV for a cartoon that had something of Tyer’s work on it. And of course, if you’re going to mention Tyer you have to talk about Rod Scribner. Bob Clampett wouldn’t be the same without Scribner’s scenes. One was East coast, one was West. One distorted the character off all semblance of drawing rules, the other distorted beyond belief (but probably – in his own way – kept the masses the same.)

We can all spot his work a mile off.

It’s Jim Tyer

This same rise to fame continued with some of the new guard. Glen Keane and Andreas Deja led a league of youngsters such as Eric Goldberg and Ruben Aquino and many others to small fame within the industry as the new golden era came to the Hollywood studios.

Meed I identify? Glen Keane & Andreas Deja.

Any good student can list off dozens of such names and can tell you what scenes they’ve done. The point that I’m ultimately getting to is that they’re all 2D animation. Where are the cgi lists of names? Where are the heroes from Toy Story and Monsters Inc. Not the directors. We all know who Brad Bird and Pete Doctor are; we know John Lasseter from Andrew Stanton, but who actually did the animation of some of those many scenes.

The names are on the credits just as Frank Thomas‘ name is on the credits of Bambi. But I can tell you immediately that Thomas did the scenes of Bambi ice skating, yet I don’t know who did the scene of Woody getting resentful, as Buzz Lightyear gets attention from the other toys. I know that Fred Moore did the scene of Lampwick turning into a donkey in Pinocchio, but I don’t know who did Merida’s mother, Elinor, in Brave. The scenes where the mother is transformed into and acts as a bear are beautifully animated, but the origin of those scenes seem anonymous. I don’t have the slightest clue as to who did them.

The names are on the credits just as Frank Thomas‘ name is on the credits of Bambi. But I can tell you immediately that Thomas did the scenes of Bambi ice skating, yet I don’t know who did the scene of Woody getting resentful, as Buzz Lightyear gets attention from the other toys. I know that Fred Moore did the scene of Lampwick turning into a donkey in Pinocchio, but I don’t know who did Merida’s mother, Elinor, in Brave. The scenes where the mother is transformed into and acts as a bear are beautifully animated, but the origin of those scenes seem anonymous. I don’t have the slightest clue as to who did them.

Grayson Ponti is one of the few who have sites that have praised some excellent cg work, and I can’t be thankful enough for his attention. Check out this post for a sample, but that was written a couple of years ago. We need more frequency and more currency.

I’ve made this complaint before. I talked about Glen Keane‘s work and got lots of hate mail. I said I was trying to learn who did which scenes so that I would know the better animators from the average ones. There were a couple of people who commented on my site and led me to a name or two. But not much changed, not really. I’d very much like it if some of you would comment here and tell me of animators I should be watching. Give me names of people who you think have done some brilliant work in cg films. Tell me the animator, tell me the scenes and I’ll try to offer some appropriate attention.

I don’t have access into the world of the cg artists and animators. I do know a few 2D artists who are working within that world, but it’s the animator who works exclusively in the medium I want to notice and give a little attention to. I need your help. I cannot do it if I don’t know who those animators are at Pixar, Dreamworks, Blue Sky, Disney, Sony and other places. If I don’t know their work I can’t give them credit.

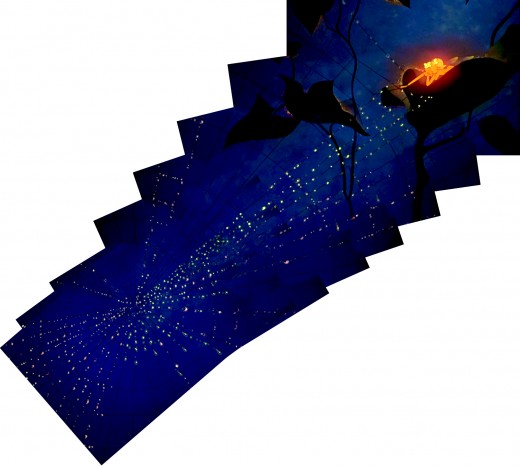

Honestly, for me this year the best animated scenes were many of those of Richard Parker in The Life of Pi. Rhythm and Hues did the work.

This scene knocks me out every time I see it. Pi is trying to

train the tiger, Richard Parker, and the tiger kneads the wood

of the boat (as any house cat would knead a blanket or its

owner, while accepting the comments of his teen overseer.

I’ve contacted the EFFX house offering to give them any attention on my Blog that they’d like from me. Publicity is publicity. (Of course, there’s been no response, surprise, surprise.) Regardless I’m going to continue promoting this film. I love it. But I’d like to add animator names and key art people responsible for the great work. I need them to contribute to get that part right.

I was also equally astounded by most of the work of the Gollum in The Hobbit. One is straight cgi; the other is what used to be called “motion capture” and is now something much much more. There’s real feeling in both those films, and in both those films those characters exist. There can be no question of it.

Now, I’d like to know who is actually doing the creative work. behind the Pixar, Blue Sky and Dreamworks films. I want to talk with people from SONY or other studios. I have a lot of questions and I want to give focus to some individuals who deserve it.

Curran W. Giddens worked on Horton, Cars 2 and Monsters University. What can he tell me about animation?

Raffaella Filipponi worked on The Croods, Shrek and Over the Hedge. She’s freelanced a lot and is that how theses studios work?

Dave Hardin worked on I am Legend, Alice in Wonderland and Turbo. Can he learn the “art” part moving from job to job?

These people were chosen at random. I don’t know their work even though I’ve seen it. Is there a point when THAT will turn around? Do you have to keep on the move to keep working? Is it time to start promoting responses? We’re not working at Disney on a 15 year job that allows you to move from feature to feature without it hurting you attitude, never mind your work?

Perhaps you think (as I sometimes suspect) that no single person can be given credit for “animating” since so many people have their hands on the steering wheel trying to move those characters forward. If so, say that. If you think there’s a team of people that work wonderfully together, I’d like to know. Essentially, I’d like your help continuing this post. If you don’t want it to be in the comment section of this article but would like to add to the follow-up post I’m going to do, email me. msanimation@aol.com is the best address; it’s the place I check most often. Write as short or as long as you like. If I have to edit it I will, and I’ll let you know when it’ll be posted so you can see it as soon as possible.

Commentary &Daily post 17 Nov 2012 07:44 am

Notes worthy

Hans Perk has begun posting the animator drafts to Disney’s Peter Pan on his blog, A Film LA.

Interesting, the timing. My wife, Heidi, is preparing to direct a version of Peter Pan for and starring school children, and, consequently, the music has been well played in our house these recent days. Quite a great score. (Some of the lyrics have been altered by Disney for PC reasons: “What made the RED man RED” has become “What made the BRAVE man BRAVE.” Hearing a few of the songs has led me to the CD score of the actual film music by Ollie Wallace. what a brilliant composer he was.

I couldn’t be more grateful to Hans for these documents, the drafts. It’s fun to scour the documents and gill in the blanks of who did what bit of animation. (Does anything like this exist in cgi world? Is there some kind of draft that will tell us who the animators are?) I also take some enjoyment from the light bickering that goes on in the coment section of the blog, as people begin to read these drafts and try to discern which characters were assigned to which animators. As Hans comments, it’s nice to take note that Norm Ferguson did his last bit of Disney animation on this feature. He was such an enormous force among the early animators, it was sad to see him burn out the way he did. Though I guess the same could be said for Freddy Moore.

Anyway, Thank you, Hans.

a new Yo La Tengo vid

- Here’s Yo La Tengo‘s latest song and a video. It’s all in the family – Art, I mean.

Emily Hubley did the video for the band with Georgia Hubley, Ira Kaplan and James McNew behind the music.

From the upcoming album “Fade”, out January 14(UK)/15(US)

and available for pre-order: here.

It’s a great number; I can’t stop playing it. I’m looking forward to the album.

GHIBLI on Screen

Currently, playing in New York – and not getting much attention – is a retrospective of the Ghibli films. This has already begun playing and will continue into the next week. You still have time to see the following films:

Castle in the Sky

Japan, Hayao Miyazaki, 1986, 124 min

Mon Nov 19__ IFC CENTER_____12:20PM

Thu Nov 22___ IFC CENTER_____12:20PM

My Neighbor Totoro

Japan, Hayao Miyazaki, 1988, 86 min

Japan, Hayao Miyazaki, 1988, 86 min

Sat Nov 17___IFC CENTER______3:15PM

Sun Nov 18___IFC CENTER_____12:50PM

Mon Nov 19__ IFC CENTER_____10:40AM 7:40PM

Tue Nov 20___IFC CENTER______3:15PM

Wed Nov 21__IFC CENTER_____12:50PM

Thu Nov 22___IFC CENTER_____10:40AM 7:40PM

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind

Japan, Hayao Miyazaki, 1984, 116 min

Sat Nov 17__IFC CENTER_____1:00PM 7:45PM

Sun Nov 18__IFC CENTER____10:40AM 5:05PM 9:50PM

Mon Nov 19__IFC CENTER____2:50PM 9:30PM

Tue Nov 20__IFC CENTER_ ___3:15PM 1:00PM 7:45PM

Wed Nov 21__IFC CENTER____3:15PM 10:40PM

Thu Nov 22_IFC CENTER___ __3:15PM

Princess Mononoke

Japan, Hayao Miyazaki, 1997, 134 min

Sat Nov 17__IFC CENTER____5:05PM

Tue Nov 20__IFC CENTER____5:05PM

Wed Nov 21_IFC CENTER_ ___9:50PM

Thu Nov 22__IFC CENTER____9:30PM

Spirited Away

Japan, Hayao Miyazaki, 2002, 124 min

Japan, Hayao Miyazaki, 2002, 124 min

Sat Nov 17__IFC CENTER_____10:40AM 10:00PM

Sun Nov 18__IFC CENTER_____2:35PM 7:25PM

Mon Nov 19___IFC CENTER____5:10PM

Tue Nov 20__IFC CENTER_____10:40AM 10:00PM

Wed Nov 21_IFC CENTER______2:35PM 7:25PM

Thu Nov 22__IFC CENTER___ __5:10PM

Imamura Docs

- I’m a big fan of Shohei Imamura‘s films. Yes, I love Kurosawa and Mizoguchi and Oshima, but I feel more of a kinship to Imamura.

- I’m a big fan of Shohei Imamura‘s films. Yes, I love Kurosawa and Mizoguchi and Oshima, but I feel more of a kinship to Imamura.

A NYTiimes piece by Mike Hale alerted me to the scheduled mini-fest of documentaries by the great director. The films will be screened at the Anthology Film Archives.

I’ve touched on his work before and have written about him in those posts. How could I not, he brings out the artist in me (if, in fact, there is one.) Back in 1979, I stumbled upon a major retrospective at the Japan Society in NYC in 1979. They were about to screen all of his films – two a night – in a complete program of all his work to that point. That meant he hadn’t done Black Rain (1989), The Ballad of Narayama (1983), or The Eel (1997) – three of his greatest. After seeing the first double-bill I was there every Monday – the opening night of each newly screened films – many of them US premieres. Most of the films, to that point, were done in B&W, but the themes were all brilliantly colorful. The weak and corrupt men, the violence, the strong women (the backbone of japan in Imamura’s eyes). They were all there from the beginning, but they grew in depth as the director grew in experience. The films added up to a strong portrait of Japanese society.

Whereas Kurosawa is a poetry of beautiful imagery, Imamura is a prose of themes, imagery, sounds and hand-held camera. He sarted as a “B” movie director, and like Don Siegel or Sam Fuller or Edgar Ulmer. He was part of the Japanese “New Wave” eracting against the slick studio flms of the time, in particular the style of Yasujirô Ozu. There’s a grit to his work, and very much like the theme of his films. The brutish male refined by that female backbone. He’s a master and I’m looking forward to seeing these documentaries.

A Newer Recobbled Cut

Garrett Gilchrist is assembling another cut of Dick Williams’ would-be-masterpiece, The Cobbler and the Thief. The first fifteen minutes are up and running and can be found embedded, below. It really does feel more finished.

The Thief Archive is Garrett’s YouTube site for all things Richard Williams.

Kickstarter

A number of people have recently asked me to promote their Kickstarter campaigns to raise funds for their movies or projects. I’ve turned down most of them and will continue that policy. There are too many going after funds, and I don’t have enough interest to support everyone with space on this Splog. It would end up making the contents of the posts dull, at least for me.

But there’s the occasional film in process that excites me.

- Uli Meyer‘s film version of Ronald Searle‘s the animated Bells of St. Trinian’s excited me. They hadn’t yet started their Kickstarter campaign, but I was ready to promote them full out. Unfortunately, they’ve had a setback and their project is on hold, as is their fund raising campaign.

- Mark Sonntag‘s film Bounty Hunter Bunny will be a challenge. I like Mark’s blog Tagtoonz, I like the film he’s proposing, and I like Mark. Given such, I will support his Indiegogo campaign as much as is possible.

- Then, this week I was approached by Fumi Kitahara about Pamela Tom’s proposed documentary, Tyrus Wong: Brushstrokes in Hollywood. Wong, of course, designed Bambi, one of my all-time favorite films, nevermind animated films. Wong is 102 years old, and I want to see him talk, paint, breathe. If there’s a chance this film will capture that, and I feel pretty confident that will happen, then I want to see the film made. Yes, I support this film. The documentary has been in the works for the past twelve years, and I would like to see it completed. Hopefully, this Kickstarter campaign will make it happen. Tale a ;ppk, and read their proposal.

Running in Place

For the past week I think I’ve been endlessly running. Running from screening room to screening room. A lot of movies to see before December is over. I should bypass them all for the blog, but I started doing this recently, so I want to continue. Even if I have to boil some of the films down to a word or three. Next week, there’ll be a couple of animated films, so it’ll get more pertinent then, but for now, let me tell you what I’ve seen. By that I mean movies.

Sunday, last week, started off with a wierd double bill including two parties. First there was a film starring Elle Fanning. Ginger and Rosa was, sort of, a love story between two young women. Girls, really, in England. Ginger (who had ginger colored hair, of course) and Rosa (who had darkish colored hair) were the closest of buddies. At least they were until Rosa fell in love with Ginger’s father, and she betrayed their love. The real surprise was at how tall Ginger . . . er, Elle Fanning was. She was just a smidgen taller than I. The tallest female I’d seen since seeing Keira Knightley in person last week. She’s almost five inches taller than I and she’s also incredibly thin. Whereas Keira is charming almost to a fault, Elle is as shy as you might suspect.

The second film that night was Silver Linings Playbook. This was a fabulous film directed by David O. Russell, who got enormous credit for his film two years ago, The Fighter. But this is the good one. An absolute delight with a great after party. But Harvey Weinstein always has the best parties. At a great and expensive place. No animators there but lots of celebrities and great food. That was a wonderful start for the week; the end of the weekend.

The second film that night was Silver Linings Playbook. This was a fabulous film directed by David O. Russell, who got enormous credit for his film two years ago, The Fighter. But this is the good one. An absolute delight with a great after party. But Harvey Weinstein always has the best parties. At a great and expensive place. No animators there but lots of celebrities and great food. That was a wonderful start for the week; the end of the weekend.

Monday brought another film, Anna Karenina. This was the film that had the luncheon the Thursday before. What a sumptuous delight, the movie. It’s supposed to take place in a theater, but the film broils over with Russian delight. Lots of waltzing camera moves and rich visuals. The camera danced all movie long in the tale of passionate infidelity as the cast pulsated with theatrical emotion led by the Tom Stoppard screenplay. A thousand page novel clocks in at just over two hours with more swooning temperament than can be found anywhere in real life. The director of Pride and Prejudice, Joe Wright, doesn’t quite pull off the emotional ending, but leaves you dumbfounded by the rich splendor on screen throughout his movie.

Tuesday was led by a lunch with Ang Lee celebrating The Life of Pi. Ths is the film I’m desperate to see, yet have only been available, so far, for the celebration. John Canemaker and I ate at the table with several of those who were marketing the film, so we learned a lot abot the making of the movie. The had also just shot an interview with Charlie Rose and were full of talk about that chat. The food at Michael’s was great. . . cod.

Tuesday evening two movies. The Persecution . . . I mean Prosecution of an American President was a political screed trying the former President, G.W.Bush, for War Crimes. Needless, to say the movie found him guilty. I didn’t sleep through ALL of it, though I tried. Ths led into Skyfall, the new James Bond film. Tis was good, but it was more action-adventure than Romantic-Action Adventure. In short the sex and the laughs were drained from the movie. Not quite your father’s James Bond, more like the teenager’s movie.

Tuesday evening two movies. The Persecution . . . I mean Prosecution of an American President was a political screed trying the former President, G.W.Bush, for War Crimes. Needless, to say the movie found him guilty. I didn’t sleep through ALL of it, though I tried. Ths led into Skyfall, the new James Bond film. Tis was good, but it was more action-adventure than Romantic-Action Adventure. In short the sex and the laughs were drained from the movie. Not quite your father’s James Bond, more like the teenager’s movie.

Wednesday evening brought a date with Mrs. James Bond, Rachel Weisz. She starred in the Terence Davies movie adaptation of the Terence Rattigan play, The Deep Blue Sea. Like all Davies movie, very claustrophobic, very British film wherein the cast usually finds themselves singing in the local pub. I love it, though it really is very slow-moving and insular for most people. The Q&A afterward had the stunningly attractive Ms. Weisz showed us how regular a person she is. The final question from the audience, of course, was, “. . . how does it feel to be married to James Bond?” “Wonderful,” was the answer she shot back. “How do ou deal with all the posters of your husband all over NY?” “I don’t notice them. I see more of them in my mind than are really there.” Ah, true love. Her movie was about guilt ridden infidelity in the fifties.

Wednesday evening brought a date with Mrs. James Bond, Rachel Weisz. She starred in the Terence Davies movie adaptation of the Terence Rattigan play, The Deep Blue Sea. Like all Davies movie, very claustrophobic, very British film wherein the cast usually finds themselves singing in the local pub. I love it, though it really is very slow-moving and insular for most people. The Q&A afterward had the stunningly attractive Ms. Weisz showed us how regular a person she is. The final question from the audience, of course, was, “. . . how does it feel to be married to James Bond?” “Wonderful,” was the answer she shot back. “How do ou deal with all the posters of your husband all over NY?” “I don’t notice them. I see more of them in my mind than are really there.” Ah, true love. Her movie was about guilt ridden infidelity in the fifties.

Animation &Animation Artifacts &Disney &Hubley &John Canemaker &repeated posts 20 Aug 2012 05:53 am

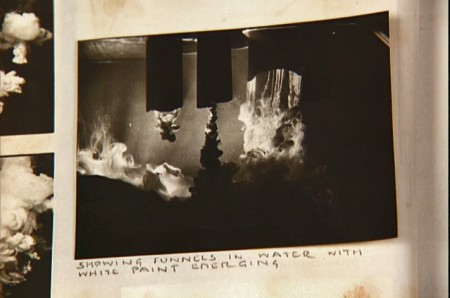

Fantasia FX – Schultheis – recap